Abstract

Background

Laboratory examinations play a crucial role in medical diagnostics and treatment, necessitating the identification of interference factors to ensure accurate results. Biotin, a common dietary supplement, can interfere with immunoassays utilizing biotin-streptavidin interactions. Studies have documented biotin's significant impact on thyroid function tests and various immunoassays, prompting the need for effective mitigation strategies.

Methods

Samples were collected from various clinical departments and analyzed for biotin levels. Biotin interference was evaluated using both old and new Elecsys reagents in assays for thyroglobulin (TG), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), anti-thyroglobulin (ATG), and free thyroxine (FT4). Biotin spike-in and depletion tests were conducted to assess interference mitigation methods. Additionally, the biotin tolerance of Roche and Abbott immunoassay systems was compared.

Results

Biotin levels were measured in 78 participants from different clinical departments: health management center (n = 13), emergency department (n = 21), intensive care unit (n = 12), gynecology department(n = 3), and hemodialysis department (n = 29). Patients undergoing hemodialysis and those in the intensive care unit (ICU) demonstrated significantly elevated biotin levels (mean = 3.282 ng/mL and 3.212 ng/mL, respectively) in comparison to other patient groups (p < 0.05), likely attributable to the intake of biotin-containing supplements. Biotin levels >500 ng/mL caused a 20 % change in assay values, resulting in false-low results for TG and AFP and false-high results for ATG and FT4 with older Elecsys reagents. Setting a 10 % change as the threshold, the newer Elecsys reagents demonstrated improved resistance against biotin interference, tolerating concentrations of 1000 ng/mL to 3000 ng/mL depending on the specific tests, consistent with the Roche package inserts. We employed a biotin depletion method that effectively restored assay accuracy for older reagents, generally resulting in less than a 10 % change when biotin levels were below 400 ng/mL. However, this depletion method was unnecessary with the newer reagents due to their increased biotin tolerance. Comparing the Roche and Abbott systems revealed significant differences in biotin tolerance. The Abbott system demonstrated greater resilience to biotin interference, while the Roche system showed biotin interference in assays for carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 125, cancer antigen 153, cancer antigen 19-9, with changes exceeding 30 % at 500 ng/mL of biotin.

Conclusions

Our study highlights the high prevalence of elevated biotin levels in hemodialysis and ICU patients, serving as a critical reference for clinical result interpretation. We confirm that Roche's newer reagents exhibit enhanced biotin tolerance, consistent with the manufacturer's claims, and demonstrate that biotin depletion effectively restores assay accuracy. These findings provide valuable methodological guidance for mitigating biotin interference in clinical immunoassays.

Keywords: Biotin tolerance, Immunoassay interference, Elecsys, Biotin depletion, Hemodialysis, ICU

Abbreviations

- alpha-fetoprotein

(AFP)

- anti-thyroglobulin

(ATG)

- cancer antigen 153

(CA-153)

- cancer antigen 19-9

(CA-199)

- cancer antigen 125

(CA-125)

- carcinoembryonic antigen

(CEA)

- free prostate-specific antigen

(FPSA)

- free thyroxine

(FT4)

- gynecology

(GYN)

- hepatitis B e-antigen

(HBeAg)

- hepatitis B surface antigen

(HBsAg)

- intensive care unit

(ICU)

- phosphate buffered saline

(PBS)

- thyroglobulin

(TG)

- thyroid stimulating hormone

(TSH)

- total prostate-specific antigen

(TPSA)

- old reagent

(OR)

- new reagent

(NR)

1. Introduction

Laboratory examinations are pivotal in guiding medical treatment decisions; therefore, it is critical to identify and mitigate interference from components in clinical laboratory testing to ensure accurate results. The most common interferences include lipids, hemolysis, and jaundice in blood, which are widely considered interference factors in most laboratories [1]. In immunoassays, biotin can also be an interference factor, particularly in laboratories that utilize the biotin-streptavidin system to catch analytes in the solid phase [2]. The Roche Cobas instrument utilizes a magnetic bar to attract magnetic beads coated with streptavidin. Streptavidin interacts with biotinylated antibodies to capture analytes during the assay process. This solid phase allows the instrument to easily wash away non-specific antigens and apply the beacon antibody for detection [3].

Biotin is widely used as a health supplement and for medical treatment in biotin-deficiency individuals. It is a water-soluble vitamin, also known as vitamin B7, vitamin H, or coenzyme R, which is an important coenzyme for carboxylation related to gluconeogenesis, fatty acid metabolism, and amino acid catabolism [4]. The daily recommended intake of biotin is at least 30 μg. Healthy volunteers who ingested 5, 10, and 20 mg of biotin had median (minimum-maximum) peak serum biotin concentrations of 41 (10–73), 91 (53–141), and 184 (80–355) ng/mL, respectively, 1 h after ingestion [5].

Previous studies suggest that the prevalence of high serum biotin levels (>10 ng/mL) is 0.8 % in Australia, 7.4 % in the USA, and 0–0.2 % in the UK [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. These findings imply that in most cases, circulating concentrations are considerably lower than assay interference thresholds. However, the prevalence of biotin in Taiwan remains understudied, lacking sufficient empirical evidence.

Studies have also indicated that tests related to thyroid function can be affected by biotin, leading to misdiagnosis [10]. According to previous studies, the impact of biotin varies across different test participants. For instance, assays for Troponin T, thyroid function, tumor markers, and others are more susceptible to biotin interference [11,12].

To mitigate biotin interference in laboratory examinations, Roche developed the newer Elecsys reagents and claimed that these reagents exhibit higher biotin tolerance in immunoassays. However, there is limited clinical evidence to substantiate the assertion that the newer reagents demonstrate superior biotin tolerance compared to the older ones.

Our study aims to assess biotin levels across five clinical departments: health management center, emergency department, intensive care unit, gynecology, and hemodialysis to determine the prevalence of biotin.

Additionally, we investigated the biotin tolerance differences between old and new Elecsys reagents by spiking biotin into samples and analyzing them using the Roche Cobas e602 instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). We also employed a biotin depletion experiment to mitigate value discrepancies between the old and new reagents.

Finally, we compared the biotin tolerance limitations between the Roche Cobas Elecsys and Abbott Architect to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of our results.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection

This cross-section study included 78 participants at the National Taiwan University Hospital from April 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020. The inclusion criteria comprised patients from the health management center, emergency department, intensive care unit, gynecology department, and hemodialysis department. Patients whose samples exhibiting lipemia, hemolysis, or jaundice were excluded. The participant distribution was as follows: health management center (n = 13), emergency department (n = 21), intensive care unit (n = 12), gynecology department (n = 3), and hemodialysis department (n = 29). All participants were adults with no risk associated with blood withdrawal. This study was approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee, NTUH-REC No: 201903080RINA. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before blood withdrawal. Patients undergoing hemodialysis underwent a second blood withdrawal after completing their hemodialysis therapy.

The researchers collected 5 mL of blood from the participants’ veins using SST™ tubes. Following collection, the samples were left to stand for 30 min before being centrifuged at 2300 g for 3 min. Subsequently, the samples were sent to the National Taiwan University Hospital Cancer Center (NTUCC) for further experimentation.

2.2. Biotin ELISA test in human serum

For the biotin test in serum, we used the IDK® Biotin ELISA kit (#K8141, Immundiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany) following the instruction manual. The plate was read on a Quanta-Lyser160 (Sias, Switzerland). Briefly, serum samples from different departments were centrifuged at 2300 g for 5 min. After collecting the supernatant from the samples, 50 μL of each sample was mixed with 150 μL of sample diluent and pipetted into pre-coated wells. The samples were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, the wells were washed, and 50 μL of conjugate (enzyme-labeled biotin) was added to compete with the sample biotin, followed by another incubation for 30 min at room temperature. Following five rounds of washing, substrate TMB was added and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, 100 μL of stop solution was added, and the optical density was read at 450 nm using the Quanta-Lyser160.

2.3. Sandwich assay on Roche Cobas e602

The following assays were conducted using the Roche Cobas e602 instrument: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), cancer antigen 153 (CA-153), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), cancer antigen 19-9 (CA-199), free prostate-specific antigen (FPSA), total prostate-specific antigen (TPSA), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroglobulin (TG), and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

2.4. Competitive assay on Roche Cobas e602

The following assays were conducted using the Roche Cobas e602 instrument: anti-thyroglobulin (ATG), free thyroxine (FT4), and hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg).

2.5. Biotin spike-in test

Initially, clinical specimens were categorized based on the values of the tests (ATG, TG, FT4, and AFP) into three groups: low, medium, and high. Each test group consisted of three independently pooled sera. Biotin solutions were prepared using biotin powder (B4501, Sigma-Aldrich, US) dissolved in distilled water. The biotin stock solution was prepared at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, and working solutions in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were prepared at concentrations of 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL. To spike biotin into the serum, 2 μL of biotin working solution or PBS were added to 198 μL of serum, resulting in final biotin concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, 1000 and 1500 ng/mL. All prepared samples were then loaded onto the Roche Cobas e602 instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and subjected to the corresponding assay.

2.6. Biotin depletion test

Serum samples were classified based on low, medium, and high values for the following tests: ATG, TG, FT4, and AFP. The samples were pooled accordingly. Biotin solutions were prepared at working concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 62.5, and 75 μg/mL. To spike biotin into the serum, 14 μL of the biotin working solution or PBS were added to 686 μL of pooled serum, resulting in final biotin concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1,000, 1,250, and 1500 ng/mL. All samples at different levels were aliquoted to 350 μL for depletion. Specifically, 220 μL of Streptavidin Mag Sepharose (Cytiva, USA) was washed three times with 1.1 mL of 1x tris buffered saline. After the final wash, the 1100 μL solution was divided into 11 tubes, each containing 100 μL aliquots. The tubes were then placed on a magnetic rack to remove the supernatant, followed by the addition of 350 μL of the serum samples mixed with different biotin levels. Removing from the magnetic rack, the specimen was incubating at room temperature for 30 min with rotation. The tubes were then returned to the magnetic rack to collect the biotin-depleted serum supernatant. Both biotin-spiked and biotin-depleted serum samples at various levels were loaded onto the Roche Cobas e602 instrument for the corresponding assays.

2.7. Biotin tolerance test in onboard elecsys reagents

Clinical serum was pooled together and divided into 4.06 mL aliquots in seven tubes. To each 4.06 mL pooled serum sample, 140 μL of PBS or biotin working solutions (15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 μg/mL) were added, resulting in final concentrations of 0, 500, 1,000, 1,500, 2,000, and 3000 ng/mL. Prepared samples were loaded onto the Roche Cobas e602 and Abbott Architect i2000SR (Abbott Park, IL) instruments, and the corresponding assays were performed. We used the onboard reagents listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The list summarizes that Roche and Abbott reagents were used. The onboard reagent indicated the current reagents on the instrument.

| Old generation Elecsys Reagent (Lot No.) | New generation Elecsys Reagent (Lot No.) | Abbott Reagent (Lot No.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| FT4 | #675279 | #724896 (onboard) | #51653UD00 |

| ATG | #693893 | #706428 (onboard) | #27888UN23 |

| TG | #569399 | #749387 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. |

| AFP | #611806 | #755525 (onboard) | #53569FN00 |

| TSH | This reagent was not performed. | #745857 (onboard) | #57375UD00 |

| CEA | #690208 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. | #53575FN00 |

| CA125 | #716163 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. | #56749FP00 |

| CA153 | #722854 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. | #58875FP00 |

| CA199 | #705691 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. | #54628FP00 |

| FPSA | This reagent was not performed. | #726169 (onboard) | #54317FN00 |

| TPSA | This reagent was not performed. | #708237 (onboard) | #54072FN00 |

| HBeAg | #765049 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. | This reagent was not performed. |

| HBsAg | This reagent was not performed. | #798146 (onboard) | This reagent was not performed. |

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between each department was assessed using Student's t-tests (Fig. 1), with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. Graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software, showing mean ± standard deviation (SD), and further details are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The p-value shown in Fig. 2 was calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 22 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). The calculation of the p-value is detailed in Supplementary Table S3. In Fig. 3, statistical significance between old and new reagents was assessed using Student's t-tests, with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. The percent change is summarized in Table 2, and additional details are provided in Supplementary Table S4. Fig. 4 employed a different analytical approach focusing on comparing trends and the summarized percent changes are detailed in Table 4, Table 5.

Fig. 1.

Biotin analysis of human peripheral blood. Collected samples (n = 78) were determined biotin level by ELISA. (A) The different colors represent samples from different sources. Blue from health management center (n = 13), red from hemodialysis department (n = 29), green from emergency department (n = 21), violet from ICU (n = 12), orange from gynecology department (n = 3). (B) Ten hemodialysis patients were randomly selected, and blood samples were collected both before and after hemodialysis to compare changes in biotin levels. These data are plotted as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. The Student's t-test was used in calculating p-value as detailed in the Supplementary Tables S1–2.

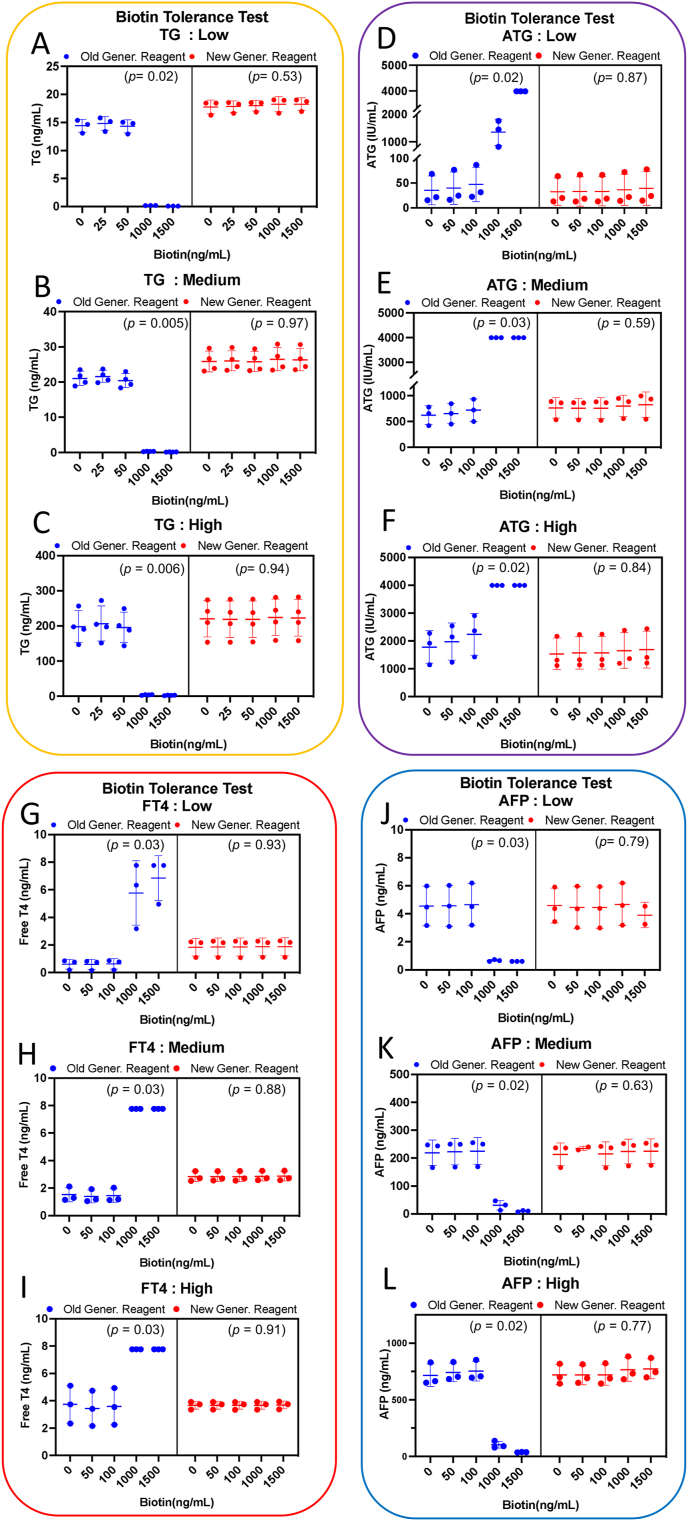

Fig. 2.

Select clinical samples with low, medium, and high range of TG, ATG, AFP, and FT4 for pooling. Add 0 to 1500 ng/mL of biotin to the pooled serum with low, medium, and high concentrations, respectively. After aliquoting, test the samples using both the new Elecsys reagent and the old Elecsys reagent on the Cobas e602 instrument. Blue-spot indicates the old generation reagent, red-spot indicates the new generation reagent. (A–C) stand for low, medium, high range of pooled TG serum. (D–F) stand for low, medium, high range of pooled ATG serum. (G–I) stand for low, medium, high range of pooled FT4 serum. (J–L) stand for low, medium, high range of pooled AFP serum. The data are plotted as mean ± SD in triplicate or quadruplicate. The p-value was evaluated by Kruskal-Wallis test as detailed in the Supplementary Table S3.

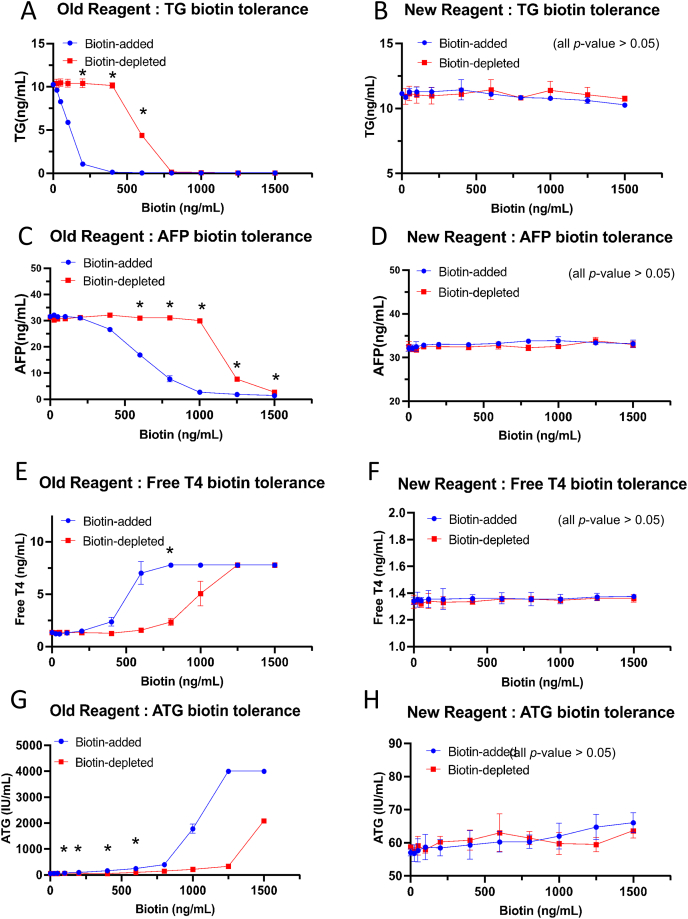

Fig. 3.

Select clinical samples with medium levels of TG, AFP, FT4, and ATG, and add 0 to 1500 ng/mL of biotin. Aliquot 350 μL of the biotin-added samples and use 20 μL of streptavidin-magnetic beads to remove the biotin and test the conditional samples (with and without biotin removal) with both the new and old reagents on the Cobas e602 instrument. The blue-line indicates the biotin-added group and red-line indicates the biotin-depleted group. (A) and (B) represent the biotin tolerance of the old and new TG reagents respectively. (C) and (D) represent tolerance of the old and new AFP reagents respectively. (E) and (F) represent tolerance of the old and new Free T4 reagents respectively. (G) and (H) represent tolerance of the old and new ATG reagents respectively. ∗p < 0.05, the Student's t-test was used in calculating p-value as detailed in the Supplementary Table S4.

Table 2.

The summary table presents the percent change in biotin tolerance between the old reagent (OR) and the new reagent (NR) after biotin spike-in or depletion. Biotin was added to each sample, and half of the biotin-spiked samples underwent biotin depletion. Both biotin-spiked and biotin-depleted samples were then tested with either the old or new reagents to evaluate their biotin tolerance.

| TG |

AFP |

FT4 |

ATG |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change (%) |

Change (%) |

Change (%) |

Change (%) |

|||||||||||||

| Biotin (ng/mL) | Biotin-added (OR/NR) | Biotin-depleted (OR/NR) | Biotin-added (OR/NR) | Biotin-depleted (OR/NR) | Biotin-added (OR/NR) | Biotin-depleted (OR/NR) | Biotin-added (OR/NR) | Biotin-depleted (OR/NR) | ||||||||

| PBS | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % |

| 25 | −6 % | −3 % | 1 % | −2 % | 2 % | 0 % | −3 % | −2 % | −9 % | 1 % | −1 % | 0 % | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | −2 % |

| 50 | −19 % | 1 % | 2 % | 0 % | 0 % | 1 % | −2 % | −3 % | −10 % | 0 % | 0 % | −1 % | 13 % | 1 % | 1 % | 1 % |

| 100 | −43 % | 1 % | 1 % | −1 % | 0 % | 2 % | −2 % | 0 % | −4 % | 1 % | 0 % | 0 % | 27 % | 3 % | 3 % | −1 % |

| 200 | −90 % | 1 % | 1 % | −2 % | −2 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 10 % | 1 % | −1 % | 0 % | 73 % | 2 % | 3 % | 3 % |

| 400 | −99 % | 3 % | −1 % | 0 % | −16 % | 3 % | 3 % | −1 % | 76 % | 1 % | −7 % | 0 % | 198 % | 4 % | 0 % | 3 % |

| 600 | −100 % | 0 % | −57 % | 3 % | −46 % | 3 % | −1 % | 1 % | 420 % | 1 % | 16 % | 1 % | 343 % | 6 % | 64 % | 7 % |

| 800 | −100 % | −3 % | −99 % | −3 % | −75 % | 5 % | −1 % | −1 % | 476 % | 1 % | 73 % | 1 % | 614 % | 6 % | 155 % | 4 % |

| 1000 | −100 % | −3 % | −99 % | 2 % | −91 % | 5 % | −4 % | 0 % | 476 % | 1 % | 274 % | 1 % | 3073 % | 9 % | 269 % | 2 % |

| 1250 | −100 % | −5 % | −100 % | −1 % | −94 % | 4 % | −75 % | 4 % | 476 % | 2 % | 476 % | 2 % | 7033 % | 13 % | 469 % | 1 % |

| 1500 | −100 % | −8 % | −100 % | −4 % | −96 % | 3 % | −91 % | 1 % | 476 % | 3 % | 476 % | 2 % | 7033 % | 16 % | 3483 % | 8 % |

Percent change = [(biotin-added or biotin-depleted) – PBS]/PBS.

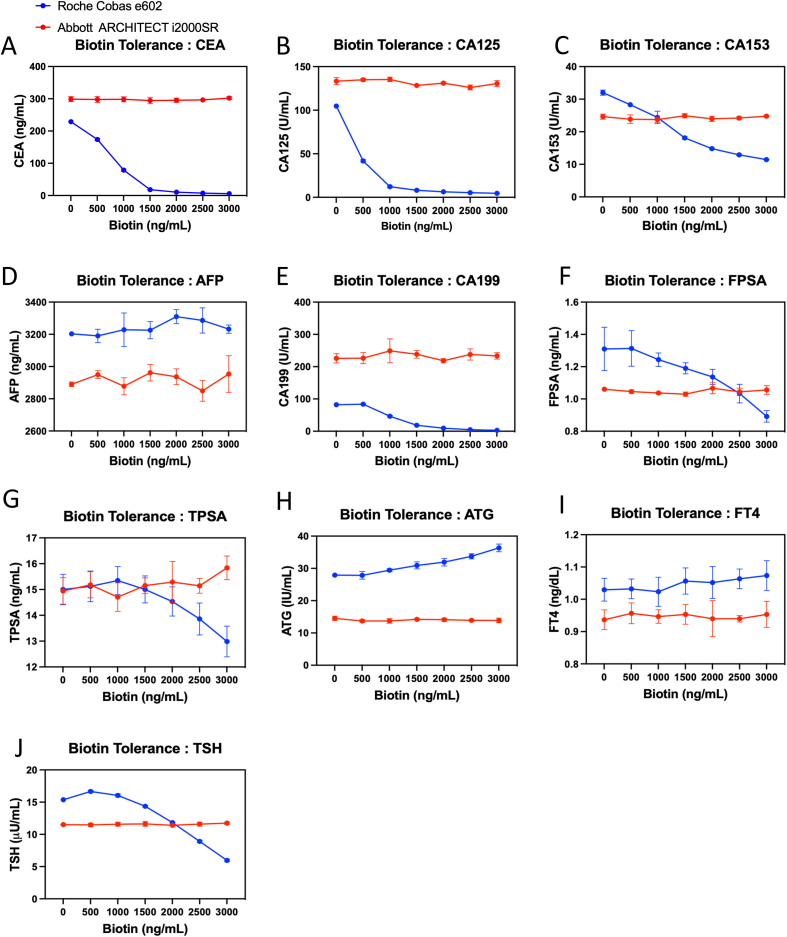

Fig. 4.

Comparison of biotin tolerance test between Roche and Abbott assays. Pooled serum spiked with 0–3000 ng/mL biotin were analyzed using Roche Cobas and Abbott Architect immunoassays. The red line indicates the results from the Abbott Architect, while the blue line represents the results from the Roche Cobas. (A) CEA (B) CA125 (C) CA153 (D) AFP (E) CA199 (F) FPSA (G) TPSA (H) ATG (I) FT4 (J) TSH. The onboard reagents for CEA, CA125, CA153, and CA199 belonged to the older reagents, while AFP, FPSA, TPSA, ATG, and FT4 belonged to the newer reagents. Data are plotted as mean ± SD in triplicates. The percent change of Roche and Abbott immunoassays are calculated and detailed in Table 3, Table 4 respectively.

Table 4.

The table summarizes the percent change in the mean test values after adding biotin solution to pooled serum with gradient levels, analyzed using Roche reagents and Cobas e602 instrument.

| Onboard Elecsys Reagent |

Change (%) after biotin (ng/mL) spike-in |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests | PBS | 500 | 1000 | 1500 | 2000 | 2500 | 3000 | |

|

CEA (Older reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | −23 % | −65 % | −92 % | −95 % | −97 % | −97 % |

| SD | ±1.2 % | ±1.9 % | ±1.7 % | ±0.3 % | ±0.2 % | ±0.1 % | ±0.0 % | |

| CA125 (Older reagent) | Mean | 0 % | −23 % | −65 % | −92 % | −95 % | −97 % | −97 % |

| SD | ±1.7 % | ±1.5 % | ±1.0 % | ±0.6 % | ±0.4 % | ±0.4 % | ±0.3 % | |

| CA153 (Older reagent) | Mean | 0 % | −49 % | −56 % | −67 % | −73 % | −77 % | −79 % |

| SD | ±1.9 % | ±1.2 % | ±6.1 % | ±1.3 % | ±0.6 % | ±0.6 % | ±0.3 % | |

| AFP (Newer reagent) | Mean | 0 % | −2.3 % | −1.1 % | −0.2 % | 1.4 % | 0.7 % | −1.0 % |

| SD | ±1.0 % | ±1.3 % | ±2.0 % | ±0.7 % | ±1.2 % | ±0.6 % | ±0.8 % | |

| CA199 (Older reagent) | Mean | 0 % | −2.3 % | −44 % | −77 % | −88 % | −94 % | −97 % |

| SD | ±0.7 % | ±1.3 % | ±3.2 % | ±0.1 % | ±0.6 % | ±0.3 % | ±0.2 % | |

| FPSA (Newer reagent) | Mean | 0 % | 0.3 % | −5.1 % | −9.2 % | −13 % | −21 % | −32 % |

| SD | ±4.3 % | ±4.5 % | ±3.2 % | ±2.6 % | ±3.6 % | ±4.4 % | ±2.7 % | |

|

TPSA (Newer reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | 0.8 % | 2.3 % | 0 % | −3.1 % | −7.6 % | −13 % |

| SD | ±1.3 % | ±2.4 % | ±1.6 % | ±1.1 % | ±3.8 % | ±4.1 % | ±4.0 % | |

|

ATG (Newer reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | −0.3 % | 5.5 % | 11 % | 14 % | 21 % | 30 % |

| SD | ±0.7 % | ±2.4 % | ±1.5 % | ±3.9 % | ±4.2 % | ±2.8 % | ±4.3 % | |

|

FT4 (Newer reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | 0.3 % | −0.6 % | 2.6 % | 2.2 % | 3.3 % | 4.2 % |

| SD | ±1.1 % | ±0.7 % | ±2.0 % | ±1.7 % | ±1.3 % | ±3.0 % | ±3.4 % | |

|

TSH (Newer reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | 8.4 % | 4.3 % | −6.6 % | −23 % | −42 % | −61 % |

| SD | ±0.1 % | ±1.2 % | ±1.6 % | ±0.9 % | ±0.5 % | ±1.2 % | ±1.4 % | |

|

TG (Newer reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | 2.9 % | −0.4 % | −6.6 % | −12 % | −20 % | −28 % |

| SD | ±1.0 % | ±3.1 % | ±0.5 % | ±1.5 % | ±1.6 % | ±3.0 % | ±2.1 % | |

| HBeAg (Older reagent) | Mean | 0 % | 52 % | 54 % | 48 % | 52 % | 54 % | 48 % |

| SD | ±0.9 % | ±7.8 % | ±9.2 % | ±6.1 % | ±3.3 % | ±2.9 % | ±6.0 % | |

|

HBsAg (Newer reagent) |

Mean | 0 % | −2 % | −12 % | −21 % | −29 % | −41 % | −52 % |

| SD | ±3.0 % | ±5.4 % | ±7.9 % | ±8.4 % | ±6.4 % | ±6.4 % | ±4.9 % | |

Each assay provides the mean value derived from triplicates at each concentration of biotin for calculating the percent change = [(biotin-added) – PBS]/PBS.

Table 5.

The table summarizes the percent change in the mean test values after adding biotin solution to pooled serum with gradient levels, analyzed using Abbott reagent and Architect i2000SR instrument.

| Abbott Reagent |

Change (%) after biotin (ng/mL) spike-in |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests | PBS | 500 | 1000 | 1500 | 2000 | 2500 | 3000 | |

| CEA | Mean | 0 % | −0.4 % | 1.1 % | −1.0 % | 0.3 % | 0.3 % | 0.8 % |

| SD | ±3 % | ±1.6 % | ±0.8 % | ±0.7 % | ±0.7 % | ±0.4 % | ±1.3 % | |

| CA125 | Mean | 0 % | 1.3 % | 1.1 % | −4.1 % | −0.3 % | −4.9 % | 1.0 % |

| SD | ±3 % | ±1.8 % | ±1.4 % | ±3.3 % | ±1.9 % | ±3.3 % | ±2.1 % | |

| CA153 | Mean | 0 % | −2.9 % | −4.7 % | 3.2 % | −4.4 % | −1.5 % | 0.1 % |

| SD | ±3 % | ±5.8 % | ±1.6 % | ±6.2 % | ±2.7 % | ±3.0 % | ±1.0 % | |

| AFP | Mean | 0 % | 2.1 % | −0.4 % | 2.5 % | 1.6 % | −1.4 % | 2.2 % |

| SD | ±1 % | ±0.7 % | ±0.8 % | ±2.3 % | ±1.4 % | ±1.8 % | ±2.8 % | |

| CA199 | Mean | 0 % | 0.8 % | 9.9 % | 6.0 % | −3.1 % | 5.3 % | 3.7 % |

| SD | ±6 % | ±5.3 % | ±9.0 % | ±4.4 % | ±3.1 % | ±2.6 % | ±3.5 % | |

| FPSA | Mean | 0 % | −1.4 % | −2.3 % | −2.9 % | 0.6 % | −1.5 % | −0.4 % |

| SD | ±1 % | ±0.4 % | ±1.0 % | ±0.9 % | ±1.1 % | ±2.1 % | ±1.7 % | |

| TPSA | Mean | 0 % | 1.7 % | −1.4 % | 1.5 % | 2.5 % | 1.4 % | 6.1 % |

| SD | ±3 % | ±3.9 % | ±4.3 % | ±2.7 % | ±4.1 % | ±3.3 % | ±5.8 % | |

| ATG | Mean | 0 % | −5.2 % | −5.3 % | −2.0 % | −2.7 % | −4.1 % | −4.1 % |

| SD | ±5 % | ±3.6 % | ±6.4 % | ±1.0 % | ±3.3 % | ±3.7 % | ±5.6 % | |

| FT4 | Mean | 0 % | 2.3 % | 1.2 % | 1.8 % | 0.6 % | 0.4 % | 1.9 % |

| SD | ±3 % | ±0.8 % | ±2.8 % | ±1.2 % | ±4.0 % | ±0.5 % | ±4.2 % | |

| TSH | Mean | 0 % | −0.3 % | 0.6 % | 1.1 % | −0.8 % | 0.7 % | 2.0 % |

| SD | ±0 % | ±1.2 % | ±0.1 % | ±2.2 % | ±0.5 % | ±1.6 % | ±1.7 % | |

Each assay provides the mean value derived from triplicates at each concentration of biotin for calculating the percent change = [(biotin-added) – PBS]/PBS.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical analysis of biotin levels

Our findings revealed significant variability in biotin levels among the hospital groups: health management center (0.312 ng/mL ± 0.068 ng/mL), emergency department (1.104 ng/mL ± 1.636 ng/mL), gynecology department (0.251 ng/mL ± 0.069 ng/mL), with notably higher levels observed in both hemodialysis (3.282 ng/mL ± 0.346 ng/mL) and the intensive care unit (3.212 ng/mL ± 2.707 ng/mL) compared to the other groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). This indicated the hemodialysis and ICU patients showed significantly higher biotin levels. Further, we considered hemodialysis patients may take Vitamin B as daily supplement, especially following the hemodialysis therapy. Thus, we monitored the biotin level in 10 patients before and after hemodialysis therapy. As expected, we found that biotin levels significantly decreased post-hemodialysis (Fig. 1B).

3.2. Comparison between Roche new and old elecsys reagents

Roche Diagnosis has developed a new generation of reagents to increase biotin tolerance in immunoassays. Since the biotin levels in our clinical samples (<5 ng/mL) were too low to interfere with the clinical test, we spiked biotin into surplus samples to compare the biotin tolerance between different generations of reagents in hormone and biomarker detections, including TG, ATG, FT4, and AFP. Biotin solution was applied to three ranges of pooled serum (low, medium, and high) in each test, with final biotin concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, 1,000, and 1500 ng/mL.

The results indicate that in the older generation group, high concentrations of biotin (1000 ng/mL) in serum led to false decreases in TG (Fig. 2A–C) and AFP (Fig. 2J–L), while causing false increases in ATG (Fig. 2D–F) and FT4 (Fig. 2G–I) significantly (p < 0.05).

3.3. Eradication of biotin interference

To eliminate or neutralize biotin interference in analyses, we developed a method for biotin depletion. We utilized streptavidin magnetic beads to deplete biotin from biotin-spiked serum samples. Both old and new Elecsys reagents were employed to analyze the following tests: TG, FT4, ATG, and AFP on Roche Cobas e602 instrument.

After biotin depletion, the analyte values showed significant recovery compared to the biotin-added groups, which exhibited false-low values. Specifically, in the older TG reagent, TG values showed significant recovery at biotin levels ranging from 200 to 600 ng/mL after biotin depletion (Fig. 3A). Similarly, in the older AFP reagent, AFP values showed significant recovery at biotin levels from 600 to 1500 ng/mL after biotin depletion (Fig. 3C) (p < 0.05). Additionally, significant recovery from false-high values was observed in the older FT4 reagent at a biotin level of 600 ng/mL (Fig. 3E) and in the older ATG reagent at biotin levels ranging from 100 to 600 ng/mL (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed with or without biotin depletion in the newer Elecsys reagents (Fig. 3B–D, F, H) (p > 0.05). Using a 10 % change to observe the depletion efficacy, our method could reduce the interference up to 400 ng/mL of biotin in TG, 1000 ng/mL in AFP, 400 ng/mL in FT4, 400 ng/mL in ATG (Table 2).

Calculating the percent change in biotin-added and biotin-depleted samples, Table 2 indicates that the newer reagents show higher biotin tolerance. Using a 10 % change as the threshold in biotin-added samples, we compared the biotin tolerance. For TG, the older reagents had a tolerance of less than less than 50 ng/mL compared to >1500 ng/mL for the newer reagents. For AFP, the older reagents had a tolerance of less than 400 ng/mL compared to >1500 ng/mL for the newer reagents. For FT4, the older reagents had a tolerance of less than 200 ng/mL compared to >1500 ng/mL for the newer reagents. For ATG, the older reagents had a tolerance less than of 50 ng/mL compared to less than 1250 ng/mL for the newer reagents.

We established a ±10 % change threshold to compare the biotin tolerance levels in our data with those specified in the reagent package inserts (Table 3). The differences in biotin tolerance observed in the older reagents compared to the package insert are as follows: FT4 (<50 ng/mL vs. ≤100 ng/mL), ATG (<50 ng/mL vs. <60 ng/mL), TG (<50 ng/mL vs. <30 ng/mL), and AFP (<200 ng/mL vs. ≤180 ng/mL). In contrast, the differences observed in the newer reagents compared to the package insert are: FT4 (>3000 ng/mL vs. ≤1200 ng/mL), ATG (<1000 ng/mL vs. ≤1200 ng/mL), TG (<1500 ng/mL vs. ≤1200 ng/mL), and AFP (>3000 ng/mL vs. ≤1200 ng/mL). For the older reagents, the estimated tolerance levels for FT4, ATG, TG, and AFP were consistent with the package inserts, varying within ±1 measured point. For the newer reagents, the biotin tolerance levels of FT4, TG, AFP were higher than those indicated in the package inserts, while ATG showed lower tolerance levels than indications of package inserts.

Table 3.

The table compares the biotin tolerance levels of the old and new reagents measured in our lab with the biotin tolerance levels indicated in the package inserts. The biotin tolerance levels were determined as the final biotin concentrations that resulted in a ±10 % change.

| Biotin tolerance of old reagents |

Biotin tolerance of new reagents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reagents | Determined by our laboratory (ng/mL) | Package inserts (ng/mL) | Determined by our laboratory (ng/mL) | Package inserts (ng/mL) |

| FT4 | <200 | ≤100 | >1500 | ≤1200 |

| ATG | <50 | <60 | <1250 | ≤1200 |

| TG | <50 | <30 | >1500 | ≤1200 |

| AFP | <400 | <180 | >1500 | ≤1200 |

3.4. Comparison of biotin tolerance limits between Roche Elecsys and Abbott Architect

Most studies have focused on biotin interference in FT4, ATG, and TG. However, we aimed to assess the biotin tolerance of all onboard Elecsys reagents in the NTUCC laboratory, including CEA, CA125, CA153, CA199, AFP, FPSA, TPSA, ATG, FT4, TSH, TG, HBsAg, and HBeAg. Therefore, we evaluated biotin tolerance in these tests and compared the percent change in biotin tolerance between Roche and Abbott immunoassays. Among these onboard reagents, CEA, CA125, CA153, CA199, and HBeAg belong to the older reagents, while AFP, FPSA, TPSA, ATG, FT4, TSH, TG, and HBsAg belong to the newer reagents (Table 1). Pooled remaining specimens were spiked with biotin as interference and analyzed using Roche Cobas e602 and Abbott Architect i2000SR instruments.

The results reveal that the Roche system is susceptible to interference from biotin when analyzing CEA, CA125, CA153, CA199, FPSA, TPSA, TSH and TG leading to decreased test values (Fig. 4A, B, C, E, F, and G) (Table 4). TG, HBsAg and HBeAg were not analyzed by the Abbott system (Table 1); HBsAg value also showed decreased results influenced by biotin elevation. Conversely, when analyzing ATG and HBeAg, these analyses were interfered with by biotin, resulting in increased values (Fig. 4H) (Table 4). However, when analyzing AFP and FT4, their tolerance to biotin was greater than 3000 ng/mL (Fig. 4D and I) (Table 4).

Comparatively, Abbott's system appears unaffected by biotin interference when analyzing these items, as test values show no significant change (Fig. 4A–J) (Table 5). Due to its different underlying rationale, the Abbott system avoided biotin interference in the immunoassays. The summary of the biotin tolerance of onboard reagents indicates that TSH, FPSA, and TPSA exhibited higher tolerance than specified in the package inserts, whereas HBsAg demonstrated lower biotin tolerance than manufacture's claims (Table 6).

Table 6.

The table lists the biotin tolerance levels of onboard reagents compared with the specifications in the package inserts. The biotin tolerance levels were determined as the final biotin levels that fell within a ±10 % change. For the reagents CEA, CA125, CA153, CA199, and HBeAg, no final data point fell within the ±10 % change threshold, and thus they are classified as "Indeterminate."

| Biotin tolerance of onboard reagents | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reagents | Determined by our laboratory (ng/mL) | Package inserts (ng/mL) |

| TSH (newer) | <1500 | ≤1200 |

| CEA (older) | Indeterminate | <120 |

| CA125 (older) | Indeterminate | <70 |

| CA153 (older) | Indeterminate | <100 |

| CA199 (older) | Indeterminate | <100 |

| FPSA (newer) | <1500 | <1200 |

| TPSA (newer) | <2500 | <1200 |

| HBeAg (older) | Indeterminate | <40 |

| HBsAg (newer) | <500 | ≤1200 |

4. Discussion

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration received a death report due to abnormal troponin testing caused by biotin interference [13]. This incident has raised significant concerns among laboratories, prompting extensive research into the potential interference posed by biotin in clinical assays. Previous studies have highlighted biotin's propensity to notably affect thyroid hormone outcomes, particularly when patients are administered high doses of biotin as therapeutic interventions [14]. Within an 8-h window post-administration, thyroid values may exhibit false results, potentially leading to misdiagnoses, notably of Grave's disease [14]. After this 8-h window, the typical range of circulating serum concentrations of biotin in the general population is from 0.1 ng/mL to 0.8 ng/mL [15], corresponding with our result (Fig. 1A). Notably, our study revealed the prevalence of serum biotin levels in a Taiwanese hospital. We observed higher biotin levels (>3.0 ng/mL) in both hemodialysis and ICU patients, likely due to the biotin-containing supplements they often take. These levels decreased significantly after hemodialysis (Fig. 1B). It is essential to warn hemodialysis patients against undergoing blood examinations shortly after biotin ingestion to avoid inaccurate results.

Roche's Elecsys immunoassay system employs two analytical methods: sandwich method and competitive method. In the sandwich method, excess biotin can decrease the binding of biotinylated antibodies to the streptavidin-microparticles, resulting in reduced electrochemiluminescence values and presenting false low results. With this rationale, Roche's immunoassays for CEA, CA125, CA153, AFP, CA199, FPSA, TPSA, TG, TSH, and HBsAg were affected by high biotin levels, as described in the package inserts. In the competitive assay, Roche's immunoassays for FT4, ATG, and HBeAg were also interfered with by high biotin levels, as stated in the package inserts. The excessive biotin can inhibit the binding of biotinylated antibodies to streptavidin-microparticles, lowering electrochemiluminescence signals and yielding higher values in calculating, leading to false high results [16].

In the United States, the FDA has commenced the use of 300 mg of biotin for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, resulting in serum biotin concentrations ranging from approximately 150 to 700 ng/mL [17]. Katzman BM et al. utilized VeraPrep Biotin™ to remove biotin from serum/plasma samples obtained from healthy donors, restoring analyte values in nine Elecsys immunoassays [9]. In our study, we employed a biotin depletion method involving streptavidin magnetic beads incubated with biotin-spiked serum samples for 30 min at room temperature. Our method effectively reduced biotin interference within the serum biotin concentration range below 500 ng/mL, offering a valuable reference for laboratories encountering biotin interference (Fig. 3) (Table 2). A previous study suggested that streptavidin-coated magnetic microparticles in Roche Elecsys reagent packs can also efficiently deplete spiked biotin [18].

Additionally, a study elucidated the impact of biotin supplementation (5–20 ng/mL) in infants with biotinidase deficiency on parathyroid hormone, TSH, and 25-OH D levels. Variations in test outcomes pre- and post-biotin removal were more pronounced using the Roche system compared to the Beckman Coulter assay platform [19]. Ylli et al. compared thyroid hormone values between Roche and Abbott systems after biotin ingestion (10 mg/day) and revealed that the Roche system was affected by biotin interference, impacting TSH, FT4, tri-iodothyronine, and TG levels [20]. In our study, the Abbott system maintained consistent test values, while the Roche system showed false results due to biotin interference (Fig. 4) (Table 4, Table 5).

To minimize biotin interference in clinical assays, we recommend that patients discontinue biotin supplementation at least 72 h prior to blood sample collection. This precaution is particularly important for patients undergoing hemodialysis or those in the ICU. If clinicians observe discrepancies between laboratory results and clinical findings, they should inquire about the patient's supplement usage and inform laboratory personnel to address potential biotin-related interference [21]. We suggest that applying 20 μL of streptavidin-coated beads is an effective and practical approach to eliminating biotin interference from oral doses of up to 100 mg, offering a reliable solution for addressing this challenge in most clinical scenarios.

Due to limited sample volumes, some experiments were performed only once, which may introduce slight statistical biases (Supplementary Table 4). To enhance the applicability and reliability of our findings, future efforts should focus on expanding the sample size through multi-center collaborations or broader recruitment strategies. Investigating the impact of biotin on clinical data in both hemodialysis and ICU patients is crucial. Monitoring kinetic changes in clinical immunoassays within this cohort will provide deeper insights.

Our study provides valuable insights into the impact of biotin interference in immune assays and effective mitigation methods. It highlights the importance of understanding patient demographics and medical history when interpreting test results affected by biotin levels, particularly in hemodialysis and ICU patients. Additionally, the development of new-generation reagents by Roche demonstrates promising advancements in increasing biotin tolerance, enhancing the reliability of hormone and biomarker detection assays. Overall, the study contributes to the ongoing efforts to improve the accuracy and reliability of clinical laboratory testing in the presence of biotin interference.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kuo-Chun Chiu: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jia-Rong Jhan: Data curation. Hsiao-Ni Yan: Investigation. Yu-Chen Liao: Validation, Data curation. Wen-Hui Lu: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kuan-Yi Lee: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Li-Yuan Cheng: Methodology. Chung-Kang Yeh: Resources. Ya-Fen Lee: Validation. Chiung-Hui Kuo: Investigation. Kuei-Pin Chung: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Tzu-I Chien: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Funding

In-hospital research project was funded by National Taiwan University Cancer Center [NTUCCS-110-05]. The sponsor had provided funding for experimental materials.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Medical Research Department of National Taiwan University Cancer Center of funding the experimental reagents and materials.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plabm.2025.e00472.

Contributor Information

Kuei-Pin Chung, Email: gbchung@ntu.edu.tw.

Tzu-I Chien, Email: A00585@ntucc.gov.tw.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kroll M.H., Elin R.J. Interference with clinical laboratory analyses. Clin. Chem. 1994;40:1996–2005. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/41.5.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trambas C., Lu Z., Yen T., Sikaris K. Characterization of the scope and magnitude of biotin interference in susceptible Roche Elecsys competitive and sandwich immunoassays. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2018;55:205–215. doi: 10.1177/0004563217701777. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28875734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colon P.J., Greene D.N. Biotin interference in clinical immunoassays. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2018;2:941–951. doi: 10.1373/jalm.2017.024257. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33636825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacheco-Alvarez D., Solórzano-Vargas R.S., Del Río A.L. Biotin in metabolism and its relationship to human disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2002;33:439–447. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(02)00399-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12459313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimsey P., Frey N., Bendig G., Zitzler J., Lorenz O., Kasapic D., Zaugg C.E. Population pharmacokinetics of exogenous biotin and the relationship between biotin serum levels and in vitro immunoassay interference. Int. J. Pharmacokinet. 2017;2:247–256. doi: 10.4155/ipk-2017-0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders A., Gama R., Ashby H., Mohammed P. Biotin immunoassay interference: a UK-based prevalence study. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2021;58:66–69. doi: 10.1177/0004563220961759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ijpelaar A., Beijers A., van Daal H., van den Ouweland J.M.W. Prevalence of detectable biotin in The Netherlands in relation to risk on immunoassay interference. Clin. Biochem. 2020;83:78–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trambas C.M., Liu K.C., Luu H., Louey W., Lynch C., Yen T., Sikaris K.A. Further assessment of the prevalence of biotin supplementation and its impact on risk. Clin. Biochem. 2019;65:64–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzman B.M., Lueke A.J., Donato L.J., Jaffe A.S., Baumann N.A. Prevalence of biotin supplement usage in outpatients and plasma biotin concentrations in patients presenting to the emergency department. Clin. Biochem. 2018;60:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D., Radulescu A., Shrestha R.T., Root M., Karger A.B., Killeen A.A., Hodges J.S., Fan S.-L., Ferguson A., Garg U., Sokoll L.J., Burmeister L.A. Association of biotin ingestion with performance of hormone and nonhormone assays in healthy adults. JAMA. 2017;318:1150–1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samarasinghe S., Meah F., Singh V., Basit A., Emanuele N., Emanuele M.A., Mazhari A., Holmes E.W. Biotin interference with routine clinical immunoassays: understand the causes and mitigate the risks, Endocr. In Pract. 2017;23:989–998. doi: 10.4158/EP171761.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muthukumar A., Gantt K. Systematic analysis of biotin interference in Roche chemistry assays. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2018;149:S7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqx032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . 2017. FDA Warns that Biotin May Interfere with Lab Tests. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kummer S., Hermsen D., Distelmaier F. Biotin treatment mimicking Graves' disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:704–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602096. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27532849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livaniou E., Evangelatos G.P., Ithakissios D.S., Yatzidis H., Koutsicos D.C. Serum biotin levels in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis. Nephron. 1987;46:331–332. doi: 10.1159/000184381. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3627330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J., Wagar E.A., Meng Q.H. Comprehensive assessment of biotin interference in immunoassays. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2018;487:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piketty M.L., Prie D., Sedel F., Bernard D., Hercend C., Chanson P., Souberbielle J.C. High-dose biotin therapy leading to false biochemical endocrine profiles: Validation of a simple method to overcome biotin interference. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017;55:817–825. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mrosewski I., Urbank M., Stauch T., Switkowski R. Interference from high-dose biotin intake in immunoassays for potentially time-critical analytes by Roche. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2020;144:1108–1117. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0425-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Öncül Ü., Eminoğlu F.T., Köse E., Doğan Ö., Özsu E., Aycan Z. Serum biotin interference: a troublemaker in hormone immunoassays. Clin. Biochem. 2022;99:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ylli D., Soldin S.J., Stolze B., Wei B., Nigussie G., Nguyen H., Mendu D.R., Mete M., Wu D., Gomes-Lima C.J., Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J., Burman K.D., Wartofsky L. Biotin interference in assays for thyroid hormones, thyrotropin and thyroglobulin. Thyroid. 2021;31:1160–1170. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D., Ferguson A., Cervinski M.A., Lynch K.L., Kyle P.B. AACC guidance document on biotin interference in laboratory tests. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2020;5:575–587. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfz010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.