Abstract

Background

DNA 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation are prevalent modifications in eukaryotes, both playing crucial roles in gene regulation. Recent studies have explored their crosstalk and impact on transcription. However, the intricate relationships among 5mC, m6A, and gene expression remain incompletely elucidated.

Results

We collect data on 5mC, m6A, and gene expression from samples from three tissues from each of four pregnant cattle and sheep. We construct a comprehensive genome-wide self-interaction (same gene) and across-interaction (across genes) network of 5mC and m6A within gene-bodies or promoters and gene expression in both species. Qualitative analysis identifies uniquely expressed genes with specific m6A methylation in each tissue from both species. A quantitative comparison of gene expression ratio between methylated and unmethylated genes for m6A within gene body and promoter, and 5mC within gene body and promoter confirms the positive effect of RNA methylation on gene expression. Importantly, the influence of RNA methylation on gene expression is stronger than that of DNA methylation. The predominant self- and across-interactions are between RNA methylation within gene bodies and gene expression, as well as between RNA methylation within promoters and gene expression in both species.

Conclusions

RNA methylation has a stronger effect on gene expression than does DNA methylation within gene bodies and promoters. DNA and RNA methylation in gene-bodies has a greater impact on gene expression than those in promoters. These findings deepen comprehension of the dynamics and complex relationships among the epigenome, epitranscriptome, and transcriptome, offering fresh insights for advancing epigenetics research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13059-025-03617-3.

Keywords: 5-methylcytosine, N6-methyladenosine, Methylation, RNA expression, Caruncle, Cow, Sheep

Background

Transcriptional regulation, a dynamic and pivotal process, is intricately governed by a network of epigenetic modifications [1]. Among these, 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in DNA [2], N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in RNA [3] and histone modifications [4] stand out as three of the most extensively studied types. 5mC, achieved through the addition of methyl groups to DNA molecules and often referred to as the “fifth base” of DNA [5], plays a fundamental role in unraveling of gene expression, development and the underlying mechanisms of disease progression [6, 7]. Conversely, m6A modification, extensively studied among RNA modifications, exerts profound effects on gene expression [3, 8], RNA stability [9], cell fate determination [10], developmental processes [11], and disease pathogenesis [12]. Unlike DNA methylation, RNA methylation is a dynamic modification sensitive to cellular environment and signaling cues, thereby regulating gene expression levels and functions. Recently, crosstalk between DNA and RNA modifications has been reported, demonstrating the interaction of 5mC and m6A methylation that orchestrates sophisticated regulatory networks governing histone modification and dynamic gene expression patterns [1, 13, 14].

5mC primarily localizes to CpG sites, and in gene promoter regions, this can inhibit the binding of transcription factors and suppress gene expression [6, 15]. However, emerging evidence suggests that methylation within the gene body promotes transcription and exhibits a positive correlation with gene expression [16, 17]. On the other hand, m6A methylation regulates gene expression by influencing various facets of mRNA metabolism, including pre-mRNA processing, nuclear export, decay, and translation [18]. While m6A methylation exhibits a negative correlation with RNA expression in wheat [19], a positive correlation has been observed in Arabidopsis [20]. To date, the specific effect pattern of RNA modification within gene bodies or promoters on gene expression remains elusive. Recent attention has focused on the crosstalk of epigenetic modifications in DNA and RNA and their impact on histone modification and gene transcription [1, 13, 14]. A novel regulatory mechanism of gene transcription mediated by RNA m6A formation coupled with DNA demethylation has been reported [1, 14]. Specifically, the RNA m6A reader gene recruits DNA 5-methylcytosine dioxygenase TET1 to demethylate DNA, leading to reprogrammed chromatin accessibility and gene transcription. Despite the crosstalk between specific genes of RNA and DNA modification on gene expression being shown, the intricate genome-wide interactions among DNA methylation, RNA methylation and gene expression remain an intriguing and unanswered question. In this study, we systematically elucidate the interaction network of 5mC methylation in gene bodies and promoter regions, m6A methylation in gene bodies and promoter regions, and gene expression in 24 samples from pregnant cattle and sheep. Employing linear and elastic net regression models, we conduct a comprehensive self-interaction (within the same gene) and across-interaction (across genes) network of 5mC methylation, m6A methylation and gene expression. This study advances our understanding of genome wide dynamics and the complex interaction among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression, offering new perspectives and opportunities to further epigenetics research.

Results

Landscapes of DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression

To characterize genome-wide DNA 5mC methylation and RNA m6A methylation, we conducted whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) on 24 samples consisting of three tissues (caruncle, mammary, and spleen) from pregnant cattle (N = 4 per tissue) and sheep (N = 4 per tissue) (Fig. 1a, Additional file 1: Fig. S1, and Additional file 2: Table S1). The clean bases ranged from 59.70 to 76.25 Gb of each sample from WGBS, which were aligned to cattle reference ARS-UCD1.2 and sheep reference ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0, respectively. To ensure confidence in the 5mC DNA methylation sites of each tissue, sites identified in at least two replicate animals with a sequencing coverage of 7 × were retained for downstream analysis. In caruncle (car), mammary (mam), and spleen (spl) tissues of cattle, 24,266,745; 21,443,055; and 23,524,525 methylated CpGs were identified, respectively, while in sheep, 23,087,917; 24,642,311; and 23,581,447 were identified from four replicates (Fig. 1b, c, Additional file 1: Fig. S2, and Additional file 2: Table S1).

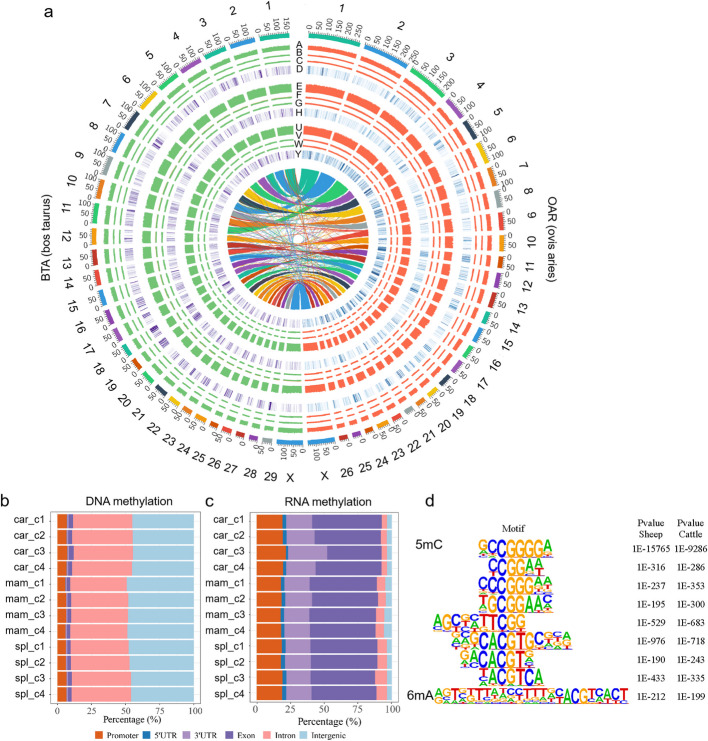

Fig. 1.

Datasets profiling of three tissues in cattle and sheep. a Tissues and datasets used in this study. b, c DNA 5mC methylation sites in caruncle, mammary, and spleen tissues in cattle and sheep. d, e Peak width of m6A methylation in of cattle and sheep. f, g Gene expression in three tissues of cattle and sheep. h, i PCA cluster of replicates from three tissues in cattle and sheep

RNA methylation was captured using m6A-specific antibodies to immunoprecipitate RNA. For each sample, two paired datasets (Immunoprecipitation and input) were generated. Samples with clean read sizes greater than 4 Gb and identified peak numbers exceeding 5000 and with at least two replicates were retained for downstream analysis in cattle and sheep. In cattle, an average of 14,377; 14,339; and 18,698 peaks were identified in caruncle, mammary, and spleen, respectively, from four replicates. In sheep, 10,295; 5629 (for two animals only) and 19,874 peaks were identified in the corresponding tissues (Additional file 1: Fig. S3 and Additional file 2: Table S1). Peak widths ranged from 50 to 1000 bp, with an enriched length around 100 bp in both cattle and sheep (Fig. 1d, e).

The RNA sequencing datasets of input samples from MeRIP-seq were utilized to measure the gene expression in cattle and sheep. The gene expression (transcripts per million, TPM) of caruncle tissue was higher than that in mammary and spleen of both species (Fig. 1f, g). Replicates from the same tissues clustered together in principal components analysis (PCA) (Fig. 1h, i).

Comparison of DNA and RNA methylation across tissues in cattle and sheep

To explore the distribution patterns of DNA and RNA methylation across tissues, we compared 5mC and m6A methylation from each chromosome of caruncle, mammary, and spleen in both species. Regarding DNA methylation, the methylation level (ML) of 5mC in CpG were higher than that of CHG and CHH contexts in all three tissues, but the ML of CpG on the X chromosome was lower than that of autosomal chromosomes in all three tissues of both species (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Fig. S4 and Additional file 2: Table S1). Notably, the ML of CpG sites in caruncle was significantly lower than that in mammary and spleen tissues. Additionally, RNA methylation exhibited uneven distribution along chromosomes but was enriched in orthologous regions across all three tissues in both cattle and sheep (Fig. 2a and Additional file 1: Fig. S4). Moreover, we identified 25 regions with similar m6A methylation enrichment, consisting of 617 genes from nine orthologous chromosomes (OAR1-BTA3, OAR5-BTA7, OAR11-BTA19, OAR12-BTA16, OAR14-BTA18, OAR19-BTA22, OAR20-BTA23, OAR21-BTA29, and OAR24-BTA25), in both cattle and sheep (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Fig. S4 and Additional file 3: Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of DNA and RNA methylation distribution across three tissues. a DNA and RNA methylation along chromosomes in cattle and sheep (A: 5mC methylation level (ML) of CpG in caruncle; B: mC ML of CHG in caruncle; C: 5mC ML of CHH in caruncle; D: m6A peak # of 1 Mbp bin in caruncle; E–H: mammary; U–Y: spleen; Inner: relationships between cattle and sheep genomes). b, c DNA and RNA methylation distribution in genomic features of cattle. d Motifs across all samples in both cattle and sheep

To further compare the distribution of DNA and RNA methylation across functional elements in tissues, we analyzed the distribution of 5mC and m6A methylation in genomic features, including promoters, 5′UTRs, 3′UTRs, exons, introns, and intergenic regions, using the annotation files of reference genomes. Distinct distribution patterns were observed for DNA and RNA methylation across genomic features. Approximately 90% of 5mC methylated sites were found in non-coding regions of the genome (introns and intergenic regions) in all three tissues of both cattle and sheep, and the caruncle tissue exhibited the highest distribution of DNA methylation within gene bodies (Fig. 2b and Additional file 1: Fig. S5a). In contrast, RNA methylation distributions in the three tissues showed clear differences from DNA methylation. The majority of m6A methylation peaks (89% in cattle and 80% in sheep) were located with coding or regulatory regions of genomes (Fig. 2c and Additional file 1: Fig. S5b). Additionally, the motif patterns of DNA and RNA methylation were analyzed across 12 samples of cattle and sheep. The motifs that exhibited a 100% match with target sequences from 5mC-methylated sites (± 25 bp) and over 95% match with target sequences from 6 mA methylation peaks were extracted (Additional file 4:Table S3). A single RNA m6A motif (RGTVKTTADCYTTTDYACGTCACT) and eight DNA 5mC motifs were consistently identified across all samples in both species (Fig. 2d and Additional file 4: Table S3). Motif analysis revealed that CGG and CGT are predominantly enriched in DNA methylation (5mC), while ACG is preferentially associated with RNA methylation (m6A).

Tissue-related DNA, RNA methylation, and expression genes

DNA and RNA methylation and gene expression of genes are known to exhibit tissue specificity, reflecting the intricate regulatory mechanisms underlying biological functions. Genes displaying DNA methylation, RNA methylation, or gene expression uniquely identified in a single tissue were designated as tissue-related DM, RM, or GE, while those lacking such methylation or expression in a single tissue but present in the other two tissues were labeled as DNA unmethylation (DUM), RNA unmethylation (RUM), or gene non-expression (GNE), respectively. The total number of DM in any replicate was 31, 16, and 20 in caruncle, mammary and spleen, respectively, with 73, 74, and 74 genes classified as DUM in each tissue (Additional file 1: Fig. S6a). Among these, 3, 2, and 2 DM genes were consistently identified in all replicates that was less than the DUM gene numbers in the respective tissues (15, 19, and 20) (Additional file 5: Table S4). But the number of uniquely identified gene from RM and GE were more than those from RUM and GNE, respectively, in all three tissues of cattle (Additional file 5: Table S4). In sheep, tissue-related DNA, RNA methylation, and gene expression also exhibited unique identification patterns across three tissues (Additional file 5: Table S4).

To explore the relationship among DNA methylation, RNA methylation and gene expression, we analyzed the genes that uniquely identified from DM, DUM, RM, RUM, GE, and GNE in each tissue. Interestingly, the consistent genes of these six categories were notably enriched in RM & GE and RUM & GNE in all three tissues (Fig. 3a, and Additional file 1: Fig. S7). The Jaccard index of overlap genes between RM & GE in the caruncle, mammary, and spleen were substantially higher than those in DM/DUM&GE/GNE (Additional file 6: Table S5). And the hypergeometric test comparing any two gene sets revealed that the combinations GE&RM (p = 4.8E − 64 in cattle and 5.2E − 99 in sheep) and GNE&RUM (p = 3.2E − 07 in cattle and 3.0E − 17 in sheep) were statistically significant in both species (Fig. 3b). These findings suggest that RNA methylation is more strongly associated with gene expression than DNA methylation, and positively relates to gene expression. We further compared the tissue-related genes between cattle and sheep. There were 8 consistent genes (ARSI, CDX2, GCM1, HAND1, HIC2, PAG6, SATB2 and SCNN1 A) in the RM & GE category of caruncle from both species (Additional file 5: Table S4). Six of these genes are known to be involved in placenta expression or embryonic development [21–26], with PAG6 specifically expressed in the placenta of ruminants and utilized for pregnancy diagnosis [25]. Additionally, we observed 4 and 16 consistent tissue-related genes in mammary and spleen, respectively (Additional file 5: Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Relationship among DNA methylation, RNA methylation and gene expression. a Tissue-related genes from DNA, RNA methylation, and gene expression in caruncle of cattle and sheep. b Hypergeometric test for tissue-related gene sets in caruncle of cattle and sheep. c Pairwise association of any two datasets of GE, DB, DP, RB, and RP (Gene #: Number of genes categorized by methylation status (M: methylated, UM: unmethylated) or expression status (E: expressed, NE: non-expressed); GE ratio: Proportion of expressed genes within each subgroup (DB_M, DB_UM, DP_M, DP_UM, RB_M, RB_UM, RP_M, RP_UM). Slope direction indicates the correlation pattern for the same methylation type (e.g., RB_M vs. RB_UM). A higher GEratio in RB_M compared to RB_UM suggests a positive correlation between RNA methylation with gene bodies and gene expression, and the steeper slope represents a stronger correlation. DBratio, DPratio, RBratio, RPratio: Similar metrics used to assess associations in other categories). d Relationships of DB, DP, RB, RP and GE in three tissues of cattle

Relationship among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression

To further evaluate the relationship of DNA, RNA methylation, and gene expression for all genes in cattle and sheep, we analyzed DNA methylation within gene bodies (DB) and promoters (DP), RNA methylation within gene bodies (RB) and promoters (RP), as well as gene expression (GE) for each gene. Each gene was categorized as methylated (M) or unmethylated (UM) in methylation datasets (DB, DP, RB, and RP) and the gene expression ratio (GEratio) was calculated by the number of expressed genes over the total number of genes for each state in DB, DP, RB, and RP datasets. The calculations of DBratio, DPratio, RBratio, and RPratio were similar with GEratio.

The preliminary relationship among DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE, was assessed through pairwise associations for any two datasets. The results indicated that when examining methylation in gene bodies or promoters, genes with 5mC methylation but without m6A RNA methylation were predominant, with fewer promoter regions exhibiting RNA methylation. The proportions of expressed and non-expressed genes were roughly equivalent across all samples of both species (Fig. 3c and Additional file 1: Fig. S8, Additional file 7: Table S6). GEratio was positively associated with DB, RB, and RP across all samples of cattle. Notably, RNA methylation had a stronger influence than DNA methylation on gene expression (Fig. 3c and Additional file 7: Table S6). DBratio was positively associated with DP and GE, while negatively associated with RP in cattle (Fig. 3c and Additional file 7: Table S6). DPratio was positively associated with DB (Fig. 3c and Additional file 7: Table S6). RBratio was positively associated with RP and GE. RPratio was positively associated with RB as well, while negatively associated with DB in cattle (Fig. 3c and Additional file 7: Table S6). Similar results were observed in sheep (Additional file 1: Fig. S8 and Additional file 7: Table S6). These findings suggest that RNA methylation has a more significant impact on gene expression than DNA methylation. Additionally, the effect of gene expression on DNA methylation or RNA methylation was crucial, confirming that the methylation levels of certain genes are influenced by the transcription of DNA methyltransferase or RNA methyltransferase genes [27].

To further quantify the effects of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE, we calculated the coefficients and significant factors from DB, DP, RB, and RP associated with GEratio using a linear regression model. The quantification model was also similarly applied to DBratio, DPratio, RBratio, and RPratio. Subsequently, a network of these five datasets was constructed in each of the three tissues. The results revealed that (1) GE was positively impacted by DB, RB, and RP in all three tissues of cattle (Fig. 3d and Additional file 8: Table S7), (2) the effect between the same type of methylation in gene-body and promotor (DB and DP, RB and RP) was positive, but the interaction between gene-body and promoter across different types of methylation (DB and RP, RB and DP) was negative (Fig. 3d and Additional file 8: Table S7), and (3) two significant correlations (DB and DP, RB and GE) were observed in all three tissues, and RB and GE displayed extreme association, indicating the effect of RNA methylation on gene expression was higher than that of DNA methylation (Fig. 3d and Additional file 8: Table S7). Similar results were also observed in sheep (Additional file 1: Fig. S9 and Additional file 8: Table S7). These quantitative findings are highly consistent with our qualitative results from tissue-related genes analysis.

Interaction network of DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and GE across genes

The analysis of self-interaction (within the same gene) among DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE provided further insights into the impact of DNA methylation and RNA methylation on gene expression within gene body and promoter regions for each gene. In cattle, a total of 7566 genes were found to have significant associations with DB (4493), DP (2616), RB (3666), and RP (369). Similarly, in sheep, 6209 genes exhibited significant associations with these factors (Fig. 4a, Additional file 1: Fig. S10, and Additional file 9: Table S8). Among these genes, 4652; 2291; 582; and 41 were impacted by any one, two, three, or four factors of DB, RB, DP, and RP, respectively (Fig. 4b and Additional file 9: Table S8). Notably, approximately 62% of expressed genes were associated with DNA and RNA methylation in gene-body (DB: 1966; RB: 1729; both DB and RB: 974) (Fig. 4b). The p-values of RB and DB were lower than those of RP and DP, and Cohen’s d metric showed that RB exhibited the greatest difference (0.43 in cattle and 0.21 in sheep) (Fig. 4c and Additional file 1: Fig. S10b). This suggested that RB has the most significant p-value associated with GE. Furthermore, the direction of effect of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE was categorized. While DB and DP showed slightly different proportions of positive (44% and 46.33%) and negative (56.09% and 53.67%) effects on GE, RNA methylation (RB and RP) predominantly exhibited positive effects on GE, accounting for 97.19% and 91.33% of RB (3563) and RP (337), respectively (Additional file 9: Table S8). Additionally, we identified high correlations for self-interaction among DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE examining the r2 value larger than 0.9. A total of 226 gene self-interactions of DB (25), DP (7), RB (176), and RP (18) on GE were observed, with most effects of gene in DB (18), RB (175), and RP (18) being positively with GE. Particularly, 99% of RNA methylation (RB and RP) exhibited a positive effect on GE (Fig. 4a and Additional file 9: Table S8). Similar results were observed in sheep as well (Additional file 1: Fig. S10a and Additional file 9: Table S8). Interestingly, 15 overlapping genes were identified with RNA methylation in gene-bodies affecting GE in both cattle and sheep (Additional file 10: Table S9). Nine of these genes were tissue-related genes (caruncle: ARSI and GCM1; spleen: CERKL, MARCO, P2RY8, PRDM16, RAB37, SPIC, TNFRSF13 C) identified in qualitative results. These findings indicated that DNA methylation and RNA methylation in the gene-body were more likely to affect gene expression than those in the promoter, with RNA methylation showing a significant positive association with GE, consistent with previous quantitative and qualitative results.

Fig. 4.

Self- and across- interaction of genes from DNA, RNA methylation and gene expression. a Positive and negative association of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE in cattle. b Distribution of self-interaction gene in DB, DP, RB, and RP associated with GE. c Distribution of p-values in the association of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE, and Cohen’s d metric across four associations in cattle. d Across-interaction compounds of the effects of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE. e Interaction network of GCM1 and ARSI genes

To further demonstrate the entire interaction network of DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE across genes, we constructed the across-interaction (across genes) of DNA methylation, RNA methylation and gene expression. In cattle, there were 16,637; 14,605; 10,364; 40,392; and 3234 across-interactions, which involved 1851; 5567; 681; 1560; and 363 target genes, in GE, DB, DP, RB, and RP from cattle, respectively (Additional file 11: Table S10). The frequency of across-interaction along target genes in GE, DB, DP, RB, and RP indicated that most target genes had unique across-interaction (Fig. 4d and Additional file 1: Fig. S10 g-j). Genes with RB were the major contributors to across-interactions of GE (Fig. 4d), while genes with DP and DB exhibited high contributions to each other (Additional file 1: Fig. S10 g and h). For RP genes, RB and GE were the primary contributors to across-interaction. Similarly, RP and GE were the dominant factors influencing across-interaction for RB genes (Additional file 1: Fig. S10 i and j). These results were consistent with the previous conclusion that the same type of methylation tends to have a greater impact than external interaction between different types of methylation data, and RNA methylation was strongly associated with gene expression. Furthermore, we compared the across-interactions between cattle and sheep, identifying a total of 1062 consistent across-interaction (GE: 209, DB: 72, DP: 7, RB: 753, and RP: 21) in both species (Additional file 12: Table S11). The caruncle tissue-related genes ARSI and GCM1, identified in previous self-interactions, also demonstrate the across-interaction of DNA, RNA methylation and gene expression. A total of 65 across-interactions involving these two genes were extracted from the 1062 interactions (Additional file 13: Table S12). Interestingly, the across-interactions of these two genes also included their self-interactions (GE:ARSI-RB:ARSI and GE:GCM1-RB:GCM1), and they involved 22 genes, which included all 6 caruncle-related consistent genes identified in the tissue-related relationship between RNA methylation and gene expression (Fig. 4e and Additional file 13: Table S12). Among them, gene expression of SCNN1 A, SATB2, HIC2, HAND1, DBNDD1, and CDX2 positively regulated the RNA methylation level of ARSI and GCM1. Additionally, six other genes (ACOT11, DLX6, GCGR, MAPK4, PRP2, and TRIM71) were impacted by RB of ARSI and GCM1. The gene expression of ARSI and GCM1 were both associated with RNA methylation of SLC39 A2, CLDN4, NAV2, SFXN1, and themselves. Furthermore, five other genes (PAG6, TMEM139, SLC4 A5, PAGE4, and SLC39 A2) were connected and impacted the RNA methylation of ARSI and GCM1 (Fig. 4e). Notably, PAGE4 and PAG6 are important pregnancy-related genes, exhibiting the highest coefficients of across-interaction in both cattle and sheep (Additional file 13: Table S12).

Pregnancy-related interaction of DNA methylation and gene expression in cattle

Our results prompted further questions concerning the potential impact of pregnancy and the interaction of DNA methylation and GE. Ideally, this analysis would take place with tissues derived from pregnant and non-pregnant animals with controlled environmental conditions, but such conditions were unattainable for the same animal. Here, we collected three replicates of WGBS and RNA-seq data from non-pregnant female mammary tissue of Holstein cattle [28] (Additional file 14: Table S13) and compared them with pregnant mammary tissue, knowing that environmental conditions, may be influencing the results. However, it is important to emphasize that if genuine pregnancy-related interactions between DNA methylation and GE exist, they would undoubtedly be captured in the results.

A total of 19,881,219 DNA methylation sites, involved 29,212 methylated genes, were identified from WGBS datasets of three replicates in non-pregnant cattle (Fig. 5a and Additional file 1: Fig. S11a). The overlap of methylated sites and PCA of gene expressions between pregnancy and non-pregnant samples both qualified the downstream analysis (Additional file 1: Fig. S11b and c and Fig. 5b). Six hundred sixty seven methylated genes and 3111 expressed genes were uniquely identified in pregnant animals (Fig. 5c, d), with 414 of 667 and 641 of 3111 being uniquely identified in all four replicates (Additional file 15: Table S14). The relationship among DB, DP, and GE from all genes in non-pregnant cattle were similar to that in pregnant animals, with DB positively associated with DP and GE, while DP was negatively associated with GE in non-pregnant animals (Fig. 5e, Additional file 1: Fig. S11 d and e). For the self-interaction of DB and DP on GE in each gene, 204 self-interactions of DB and DP on GE with r2 ≥ 0.9 were identified (Additional file 1: Fig. S11f and Additional file 16: Table S15). To further identify pregnancy-related self-interactions, we retained the self-interaction with the deviation (TPMpreg-TPMreg) ≥ 10. A total of 47 highly differential self-interactions, involving 44 genes, were identified (Additional file 16: Table S15). Nine of these genes (GREM1, IL17D, GSTA4, ABI3BP, ACAP2, HEG1, MAPK9, PODXL, RAB13, SEC63, UBE4 A, and ZEB2) have been previously associated with pregnancy or embryonic development in human or animals [29–31]. Interestingly, among the 44 genes, three expressed genes (GREM1, PODXL, and SEC63) were impacted by both DB and DP in self-interaction. All three genes were related to pregnancy. For GREM1 and PODXL, both DB and DP were negatively associated with GE, while in SEC63, DB was positively associated with GE (Fig. 5f). Notably, the gene IL17D, shares a gene family with IL-17 A in humans, has been documented to play a pivotal role in establishing pregnancy [32, 33]. The expression of IL17D was positively impacted by DP (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of nonpregnant and pregnant DNA methylation and gene expression data. a Methylated sites in mammary tissue of non-pregnant (reg.) and pregnant (pre.) samples. b Methylated genes in non-pregnant and pregnant samples. c Assessment of RNA-seq data. d Expressed genes in non-pregnant and pregnant samples. e Pairwise relationship between DNA methylation and RNA expression in non-pregnant samples. f Self-interaction of GREM1, PODXL, SEC63, and IL17D genes

Discussion

In eukaryotes, the DNA 5mC modification is widely distributed throughout the genome [34], and RNA m6A modification stands out as the most abundant epitranscriptome modification [8, 35]. Decades of research have solidified DNA and RNA methylation as critical regulatory mechanisms in gene expression [1, 14, 36]. However, the global landscapes of interaction network involving DNA 5mC methylation, RNA m6A methylation, and gene expression have rarely been documented comprehensively. In this study, we conducted a systematic and comprehensive analysis to assess the interaction of 5mC, m6A, and gene expression using a stepwise analytical framework through both qualitative and quantitative assessments. The qualitative evaluations included tissue-related methylated and expressed genes (Fig. 3a,b), and pairwise correlations (Fig. 3c). The quantitative assessments involved constructing genome-wide interaction network of DNA methylation (DB, DP), RNA methylation (RB, RP), and gene expression (GE) for each tissue (Fig. 3d), as well as self- and across-interaction network for genes (Fig. 4) in cattle and sheep. The findings from all assessments of both species consistently demonstrated that RNA methylation exerts a stronger influence on gene expression compared to DNA methylation, with a significant positive association. Notably, methylation in gene bodies had a more pronounced effect on gene expression than that in promoters. Furthermore, we proposed the establishment of self- and across-interaction networks among DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE by employing linear and elastic net regression models. This approach not only expands the knowledge of the regulatory crosstalk between the epitranscriptome and the epigenome, but also provides valuable methodological references for comprehensive genome-wide analysis of interactions among multiple omics datasets.

The intricate interaction among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression regulation is essential for orchestrating biological processes [7, 12, 37]. Methylation in different genomic regions may exert diverse influences on gene activities [38]. Conventionally, it is believed that DNA 5mC methylation in gene-bodies increases gene expression, while in promoters, it reduces gene expression [16, 39]. However, some investigations have proposed contrasting discoveries, suggesting that DNA methylation is negatively associated with transcription in gene bodies but positively in promoters [17, 40]. This study further elucidated the effect of 5mC in gene bodies and promoters on gene expression for specific genes (Fig. 4a, b). Consistent with previous findings, we identified both positive and negative relationships between gene expression and DNA methylation in gene bodies and promoters. Moreover, we identified several genes with opposite effects, indicating a complex and dynamic relationship between DNA methylation and the transcription of functional genes in mammals. Furthermore, we examined the impact of RNA methylation in gene bodies and promoters on gene expression (Fig. 4a, b). Our study obtained notable additional findings: (1) In both cattle and sheep, we identified genes that were consistently methylated with m6A and expressed, as well as genes that were unmethylated and not expressed (Fig. 3a, b). This qualitative analysis underscores that RNA methylation has a stronger association with gene expression than DNA methylation. (2) The slopes of the GEratio are steeper in RB and RP compared to DB and DP (Fig. 3c), providing quantitative confirmation of the positive effect of RNA methylation on gene expression. This effect is notably stronger than DNA methylation; and (3) the positive self-interactions between RB and GE constitute 97.19% (3563), and those between RP and GE make up 91.33% (337) of their respective total interactions (Fig. 4a). The across-interaction involving DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE reveal that RB-GE and RP-GE are the predominant across-interactions (Fig. 4d). The above results clearly demonstrate that RNA methylation has a more substantial impact on gene expression than DNA methylation and show a positive association with gene expression. Furthermore, regarding the interaction between DNA methylation and RNA methylation, recent studies have investigated a regulatory mechanism in which RNA m6A reader recruits DNA 5-methylcytosine dioxygenases to demethylate DNA [13, 14], leading to reprogrammed chromatin accessibility and gene transcription. Our findings indicate that the interaction effects between gene-body and promoter methylation across different methylation types (DB and RP, RB and DP) were negative (Fig. 3d and Additional file 18: Table S7). This further suggests that DNA methylation and RNA methylation may have distinct functional mechanisms in different gene regions. The refined conclusion from this study not only complements but also extends previous research [14, 19, 20, 41]. These insights are poised to have a substantial impact on the dynamic regulation of the epigenome and epitranscriptome on gene expression.

In this study, we collected a physiologically specific tissue, the caruncle, during pregnancy in both cattle and sheep. To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies investigating the interactions among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression specifically in caruncle tissue. Interestingly, our analysis revealed interactions between DNA or RNA methylation and gene expression in genes related to caruncle tissue and pregnancy. We identified a total of 8 caruncle-related genes (Additional file 5: Table S4), including ARSI, which exhibits preferential expression in placenta, embryonic cell, and the eye [21]. Another gene, CDX2, serves as a master homeodomain protein defining trophectoderm during development [22]. Additionally, Glial cells missing-1 (GCM1), a transcription factor crucial for proper placentation in mice and expressed in binucleate cells in the cattle placenta, that is highly expressed in human syncytiotrophoblasts (ST) and extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs) [23]. HAND1, expressed in uninucleate trophoblasts in the bovine placenta [42], plays a role in the differentiation of human trophoblast stem cells into syncytiotrophoblast cells [26]. Furthermore, HIC2, involved in developmental hemoglobin switching, is highly expressed in fetal cells and contributes to embryonic cardiovascular development [24]. Finally, PAG6, a pregnancy-associated glycoprotein, plays a vital role in the maintenance and progression of pregnancy in ruminants [25]. These genes were also identified in self-interactions of DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE (Additional file 9: Table S8). Despite variations in genetic backgrounds among non-pregnant and pregnant samples and the susceptibility of methylation and gene expression to environmental influences, we still identified nine pregnancy-related genes (Additional file 16: Table S15), including GREM1 [29], IL17D [43], GSTA4 [44], ACAP2 [45], HEG1 [46], MAPK9 [47], PODXL [31], SEC63 [30], and ZEB2 [48], which have been reported to be associated with pregnancy or embryonic development in human or animals. Furthermore, all three expressed genes (GREM1, PODXL, and SEC63), impacted by both DB and DP in self-interaction, were highly confirmed to be associated with pregnancy [29–31]. The gene IL17D, which belongs to the same gene family as IL-17 A in humans, has been documented to exert a pivotal role in establishing pregnancy [32, 33]. Understanding the landscape interaction among DNA 5mC, RNA m6A methylation, and gene expression sheds light on the complex regulatory mechanisms underlying cellular physiology. The identified caruncle and pregnancy-related genes warrant further experimental validation and exploration of their biological functions, including their roles in developmental biology and regenerative medicine.

In mammals such as cattle and sheep, pregnancy and lactation represent natural and essential physiological states, closely tied to their reproductive and metabolic processes. Studying these states provides valuable insights into how epigenomic mechanisms regulate gene expression during critical life stages. To enhance the broader applicability of our findings, we also analyzed DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression dataset from non-pregnant sheep with coarse and fine wool traits. These datasets were obtained from two published studies on the same animals from the same laboratory [49, 50], under project numbers PRJNA760832 and PRJNA760789. In the fine-wool sample, we identified 14,871,314 DNA 5mC methylation CpG sites, 26,579 RNA m6A methylation peaks, and 14,997 expressed genes. In the coarse-wool sample, the corresponding numbers were 12,965,907, 24,493, and 14,400, respectively (Additional file 1: Fig. S12a, Additional file 17: Table S16). The m6A peak widths ranged from 0 to 500 bp, with most being less than 250 bp (Additional file 1: Fig. S12b). Gene expression patterns were highly similar between the fine- and coarse-wool samples (Additional file 1: Fig. S12c), resembling those observed in pregnant sheep. Furthermore, we calculate the GEratio based on the gene with methylation (M) or without methylation (UM) in gene bodies (DB), promoters (DP), RNA methylation in bodies (RB), and promoters (RP). The regression model was applied to assess the coefficients and R2 values for the effects of DB, DP, RB, and RP on gene expression. The results indicated that gene body and promoter methylation were predominantly composed of 5mC DNA methylation, with fewer RNA methylation events observed in promoter regions (Additional file 1: Fig. S12 d, Additional file 17: Table S16). The GE ratio was positively associated with DB, RB, and RP, but negatively correlated with DP in both fine- and coarse-wool samples. Notably, RNA methylation exerted a significant stronger influence on gene expression than DNA methylation (Additional file 1: Fig. S12e, Additional file 17: Table S16). Importantly, the findings observed in pregnant animals were consistently recapitulated in non-pregnant sheep, providing a more comprehensive analysis across distinct physiological conditions. By integrating data from both pregnant and non-pregnant sheep, our study enhances the generalizability of the results and captures a broader spectrum of epigenetic and transcriptional dynamics.

Studies have characterized that methylation levels of DNA or RNA are regulated by specific methyltransferase and demethylase genes. RNA m6A methylation is catalyzed by methyltransferase complexes such as METTL3 [1], METTL14 [51], ZC3H13 [52], and others, while m6A removal is mediated by demethylases such as ALKBH5 [53]. Similarly, DNA 5mC methylation involves methyltransferase like DNMT3 A [54] and demethylases like TET1 [55]. The expression of methyltransferase or demethylase genes theoretically leads to high or low methylation levels. In this study, we extracted 62 annotated DNA and RNA methyltransferase and demethylase genes from cattle genome annotation file (Additional file 18: Table S17) and investigated their across-interaction between methylation level of DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE. The expression of six genes (HNMT, NSUN4, TET1, TET3, METTL7 A, METTL7B, and METTL27) impacted the methylation level of DNA methylation and RNA methylation. Notably, TET1 and TET3 were negatively associated with DNA methylation in gene bodies, and TET1 was positively associated with RNA methylation (Additional file 1: Fig. S13). All these findings were consistent with previous research [1, 56]. Interestingly, METTL7 A and METT7B exhibited opposite effects on DNA methylation (Additional file 1: Fig. S13). In previous studies, METTL7 A had been found to be under-expressed, whereas METTL7B was over-expressed in cancer aggressiveness and progression [57]. Additionally, METTL7B expression showed a significant negative correlation with METTL7B DNA methylation [27], while METTL7 A overexpression altered the methylation status of related genes to favor osteogenic differentiation and cell survival [58]. The findings in our study strongly align with existing research, bolstering the reliability of our results. Furthermore, the genome-wide identification of interaction networks among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression fill a critical gap in experimental research and offers valuable computational insights for uncovering novel interactions to further investigate.

We selected the linear regression framework for its ability to capture direct associations between methylation and gene expression while maintaining interpretability. Although alternative models, such as generalized linear models (GLM) or nonlinear approaches, were considered, they were not employed due to the relatively small sample size (n = 12), which limits the robustness of high-dimensional modeling. Biological processes, especially those involving complex regulatory mechanisms like DNA and RNA methylation and gene expression, may indeed exhibit nonlinear interactions. In future studies, with larger sample sizes, more advanced nonlinear models, such as deep learning techniques or other artificial intelligence-based approaches, could be employed to better capture these intricate and dynamic relationships. Additionally, while our study provides important insights into the correlations and interactions between DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression, functional validation of the identified genes and pathways remains an essential next step. Future research should incorporate experimental validation to directly assess the biological impact of these regulatory elements. These future directions will strengthen the biological relevance of our findings and provide deeper mechanistic insights into the functional roles of DNA and RNA methylation in gene regulation.

Conclusions

The qualitative evaluations of tissue-related methylated and expressed genes, along with the quantitative assessments of genome-wide interaction networks of DNA methylation (DB, DP), RNA methylation (RB, RP), and gene expression (GE) for tissues, as well as self- and across-interaction networks for genes, were conducted in cattle and sheep to assess the relationships of 5mC, m6A, and gene expression. The findings from both species consistently demonstrated that RNA methylation has a stronger influence on gene expression compared to DNA methylation, with a significant positive association. Notably, methylation within gene bodies had a more pronounced effect on gene expression than methylation within promoters. Furthermore, we proposed linear and elastic net regression models to establish self- and across-interaction networks among DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE. These models are applicable for decoding the relationships among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression in other species. This data and the developed models enhance our understanding of genome-wide dynamics and the complex associations among DNA methylation, RNA methylation, and gene expression, offering new perspectives and opportunities to advance epigenetics research.

Methods

Animals and tissues collection

Tissues were collected from two species of healthy adult pregnant cattle and sheep as approved by the University of Idaho Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) with number IACUC-2020–58 for sheep and IACUC-2021–21 for cattle. Caruncles (manually separated from cotyledons but may have cotyledonary tissue carryover and be more representative of placentome), mammary glands, and spleens were collected from four healthy adult Hereford and four Suffolk (14 months old). Small pieces of all 24 tissues were collected within 30 min postmortem, briefly rinsed with ice cold 1 × PBS, and promptly snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were transferred from liquid nitrogen directly into a − 80 °C freezer for storage until use.

DNA 5mC Library construction and sequencing

DNA extracted from these tissues was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis to test for DNA degradation and potential RNA contamination. The DNA was then quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Rockland, DE, USA) and a Qubit2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Lambda phage DNA was spiked in as a negative control for DNA methylation. Since lambda phage DNA lacks DNA methylation, all the cytosines in its DNA should be converted to uracil during bisulfite conversion. Any unchanged cytosine in the lambda phage DNA can thus be used to determine the efficiency of bisulfite conversion. For library construction, DNA samples were fragmented into 200–400 bp using sonication (Covaris S220, Woburn, MA, USA). Next, end repair, A-ligation, and methylation sequencing adapter ligation was performed. Following this, the DNA library was subjected to bisulfite treatment (EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Library concentration was first quantified by Qubit2.0, diluted to 1 ng/μl before checking insert size on Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and quantified with more accuracy by quantitative PCR (effective concentration of library > 2 nM). Libraries were then pooled per sample and sequenced paired-end reads from Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform.

RNA m6A immunoprecipitation and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated and purified using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s procedure. The RNA amount and purity of each sample was quantified using NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). The RNA integrity was assessed by Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA) with RIN number > 7.0, and confirmed by electrophoresis with denaturing agarose gel. Approximately more than 1 μg of total RNA was fragmented into small pieces using Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (NEB, cat.e6150, USA) at 94℃ for 5 min. Then the cleaved RNA fragments (including rRNA fragments) were incubated with m6A antibody-dynabead compounds. Then the IP RNA was reverse-transcribed to create the first-strand cDNA by SMARTScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase (CloneTech, cat.634414, Japan) which were next used to add adapter and synthesize second-stranded DNAs with PCR by the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94℃ for 1 min; denaturation at 98℃ for 15 s, annealing at 55℃ for 15 s, and extension at 68℃ for 30 s; and then final extension at 68℃ for 2 min (5 cycles). Then the amplified DNA-seq library was purified by immobilization onto pure beads. The cDNA sequences originating from rRNA reverse transcription were cut by ZapR v2 and R-Probes v2 (for mammal) under the condition: incubation at 72℃ for 2 min, 4℃ for 2 min, 37℃ for 1 h, 72℃ for 10 min. The final library was amplified by second round PCR which consistent with the first round PCR program, and the number of PCR cycles increased to 12–16. Finally, 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads (PE150) were sequenced from Illumina Novaseq™ 6000.

DNA 5mC and RNA m6A methylations analysis

The quality of raw sequences from whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) was assessed using FastQC v0.11.5 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Adapters and low-quality bases (phred score < 20) were trimmed using Trim Galore v0.4.5 with default parameters (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore). Cleaned data for each sample were aligned to the reference genomes of cattle (ARS-UCD1.2) [59] and sheep (ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0) [60] using Bowtie2 aligner within BSseeker2 v2.1.8 [61, 62]. Duplicate reads in the alignment bam files were then marked and removed by MarkDuplicates of Picard v2.25.4 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard), and methylation sites and methylation level (ML) for each cytosine were determined using BSseeker2 with bs_seeker2-call_methylation.py. To ensure confidence in the 5mC DNA methylation sites in each tissue, sites identified in at least two replicate animals with a sequencing coverage of 7 were retained for downstream analysis (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Regarding m6A methylation, raw reads containing adaptor contamination, low-quality bases, and undetermined bases were filtered using fastp v0.22.0 (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp). The quality of sequences from IP and input samples was verified and controlled using FastQC and RseQC (http://rseqc.sourceforge.net). HISAT2 v2.2.1 was then used to align reads to the reference genomes of cattle and sheep [63]. Peaks from each sample were called using exomePeak2 v1.14.3 (https://github.com/ZW-xjtlu/exomePeak2) with “whole genome” mode. Samples with clean read sizes greater than 4 Gb and identified peak number exceeding 5000, with at least two replicates, were retained for downstream analysis in both cattle and sheep. Transcripts per million (TPM) values, used to measure expression levels for all genes from input samples, were calculated using StringTie v2.2.0 [64]. A TPM value of 0.5 was used as the baseline expression threshold for genes of samples, following the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI)’s guidelines (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/FAQ.html). Principal component analysis (PCA) of gene expressions across samples was conducted using R package scatterplot3 d [65].

Comparison of DNA and RNA methylation across tissues

The comparisons of CpG, CHG, and CHH methylation levels from WGBS and 6 mA peaks from MeRIP-seq were plotted by each 1 Mb bin using Circus v0.69–8 [66]. The average ML of CpG, CHG, and CHH in each bin was calculated for 5mC methylation, and the number of peaks in each bin was calculated for m6A methylation across tissues. Consistent orthologous regions were identified from the aligned sequences between cattle and sheep using nucmer of MUMmer v4.0.0rc1 [67]. Enriched regions of RNA methylation were isolated based on the presence of more than 14 m6A peaks in a bin across all three tissues. Additionally, the distribution of 5mC and 6 mA within genomic features along chromosomes was meticulously analyzed using R packages GenomicFeatures [68] and ChIPseeker [69]. The motif patterns of DNA 5mC methylation and RNA m6A methylation were detected using findMotifsGenome.pl from Homer v4.10.4 [70].

Qualitative assessment of tissue-related genes: DNA, RNA methylation, and gene expression

Genes displaying DNA methylation, RNA methylation, or gene expression uniquely identified in a single tissue were designated as tissue-related DM, RM, or GE, while those lacking such methylation or expression in a single tissue but present in the other two tissues were labeled as DNA unmethylation (DUM), RNA unmethylation (RUM), or gene non-expression (GNE), respectively. To explore high-confidence genes that are unique to each tissue, we selected genes that uniquely identified in all four replicates within each tissue. We then assessed the overlap genes from all pairwise combinations of DM, DUM, RM, RUM, GE, and GNE using the jaccard index [71] and hypergeometric test [72]:

where Gi and Gj are the gene cluster of the ith and jth conditions (DM, DUM, RM, RUM, GE, and GNE), respectively. N is the total number of genes, n and K and the sizes of the gene sets Gi and Gj, and k is the number of intersecting genes between the sets Gi and Gj.

Relationship among DNA methylation, RNA methylation and gene expression

DNA methylation in gene-body (methylation within gene) and promoter (methylation within the upstream 0–2000 bp region of gene) were categorized as two groups: DB and DP, respectively. Similarly, RNA methylation was categorized as RB and RP for gene-body and promoter, while gene expression was marked as GE. For each category (DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE) could be further divided into two subgroups: methylation and unmethylation (DB_M and DB_UM, DP_M and DP_UM, RB_M and RB_UM, RP_M and RP_UM) or expression and non-expression (GE and GNE). Pairwise association between GE and methylation categories were assessed using the gene expression ratio (GEratio), calculated as the number of expressed genes divided by the total number of genes in each methylation subgroup. For instance, when examining the association between GE and DB, GEratio was calculated separately for the DB_M and DB_UM subgroups. Similar calculations were performed for the associations between GE and the other three methylation categories (DP, RB, and RP). To globally quantify the relationship between GE and methylation (DB, DP, RB, and RP), multiple linear regression analysis was employed using the equation: YGE = β0 + βDBXDB + βDPXDP + βRBXRB + βRPXRP + ϵ; where YGE = (Y1, …, Y16)T is the 16-dimensional response variables of GEratio for all combinations of DB, DP, RB, and RP. X.. denotes the methylation indicator of DB, DP, RB, and RP (1 for methylation, 0 for unmethylation), and β.. represents the corresponding coefficients. The same approach was used to assess the relationship between one of DB, DP, RB, and RP and the rest four categories, and the DBratio, DPratio, RBratio, and RPratio were used to calculate the linear regression YDB, YDP, YRB, and YRP, respectively. The coefficients and p-values obtained from five linear regressions were then utilized to construct the relationship network for each tissue, with Cytoscape v3.10.0 [73] used for visualization. The direction of the relationship was determined by the sign of the coefficient (+ for positive, − for negative), and the width of the edge represented the significance level indicated by the p-value.

Interaction of DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE across genes

To explore the specific genes with the interaction of 5mC, m6A, and GE, we conducted self- and across-interactions for DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE. Self-interaction refers to the interaction within the same gene for DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE, while across-interaction denotes interactions of DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE across genes (gene–gene interaction). Considering that GE is usually influenced by its own DNA methylation or RNA methylation, and the methylation level of DNA or RNA methylation tend to be impacted by special methyltransferase and demethylase genes, we focus on the effects of 5mC and m6A in gene-body and promoter on GE for self-interaction. To quantitatively assess the interaction between gene expression and methylation levels within the same gene across 12 samples, we applied a linear regression model:

where YGE = (Y1, …, Y12)T represented the TPM values of GE for 12 samples. X.. denoted the methylation level values of DB, DP, RB, and RP, and β.. represented the corresponding coefficients in each gene. The significant of the association between DB, DP, RB, and RP and GE (p ≤ 0.05) was further evaluated using four subgroup gene sets categorized by significant DB, DP, RB, and RP associations. To quantify the differences in p-values between any two subgroups, Cohen’s d metric was applied: d = (M1 − M2)/Sp, where M1 and M2 are the mean p-values of the two subgroups, and Sp is the pooled standard deviation, calculated as:

where s1 and s2 are the standard deviations of the two groups, n1 and n2 are the sizes of the gene sets in the respective subgroups. Subsequently, we classified the self-interaction of genes into two groups, positive (+) and negative (−), based on the sign of coefficients. And the value of r2 larger than 0.9 was used to obtain the confidence high correlation self-interaction of the effects of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE.

For the across-interaction, the entire relationships among DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE were considered. Therefore, GE, DB, DP, RB, and RP were respectively used as response variables, with the rest four factors serving as explanatory variables. In the across-interaction of DB, DP, RB, and RP on GE in gene i, the model formula for Elastic Net regression can be expressed as follows:

where YGEi represents the TPM values of the ith (i = 1, …, N) gene from 12 samples, Xjk denotes the explanatory variables of methylation level from DB, DP, RB, and RP in gene j (with k = 1, 2, 3, and 4, and j = 1, …, N), and Bjk represents the corresponding effect coefficients of Xjk. βi and εi stand for the intercept term and random error, respectively. The coefficients Bjk are estimated by minimizing the following objective function:

where λ is the regularization parameter calculated by cross-validation from cv.glmnet of the R package glmnet [74]. The regularization penalty consists of two parts: the L1-norm penalty () and the L2-norm penalty (). The mixing parameter α controls the balance between the L1 and L2 penalties. When α = 1, the model behaves like Lasso regression, and α = 0 resembles Ridge regression. Considering the balance of variable selection and variable correlation, we used α = 0.1. Given the large number of annotated genes in cattle and sheep, we initially reduced the variables in the Elastic Net regression model by retaining genes with a correlation between YGEi and Xjk higher than 0.5. The models for across-interactions of response variables YDBi, YDPi, YRbi, and YRPi for DB, DP, RB, and RP were similar.

Pregnancy-related interaction of DNA methylation and gene expression

Three replicates of WGBS and RNA-seq data from non-pregnant female mammary tissue of Holstein cattle were collected and compared with pregnant mammary tissue [28]. All analysis processes, including raw reads quality control, adaptor trimming, alignment, non-pregnant tissue-related gene identification, relationship among DB, DP, and GE from all genes and self-interaction of the effects of DB and DP on GE, were similar to those in both cattle and sheep. Due to the different background between non-pregnant animals and pregnant animal, the self-interaction was filtered by using regression correlation r2 ≥ 0.9 and the gene expression deviation (TPMpreg − TPMreg) ≥ 10.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figures S1-S13.

Additional file 2: TableS1. Datasets stats of cattle and sheep.

Additional file 3: TableS2. Consistent enriched 6mA regions across cattle and sheep.

Additional file 4: TableS3. Motif of 5mC and m6A across samples from cattle and sheep.

Additional file 5: TableS4. Tissue related methylation and gene expression.

Additional file 6: TableS5. Methylation, gene expression, and gene JaccardIndex and Pvalue.

Additional file 7: TableS6. Pairwise association in DB, DP, RB, RP, and GE.

Additional file 8: TableS7. Quantify of gene expression ratio by regression model.

Additional file 9: TableS8. Gene self-interaction in cattle and sheep.

Additional file 10: TableS9. Overlap of self-interaction in cattle and sheep.

Additional file 11: TableS10. Across-interactions in cattle and sheep.

Additional file 12: TableS11. Overlap of across-interactions in cattle and sheep.

Additional file 13: TableS12. Caruncle related across-interactions of ARSI and GCM1.

Additional file 14: TableS13. Non-pregnant regular samples information.

Additional file 15: TableS14. DNAm RNAe genes from pregnant and non-pregnant cattle.

Additional file 16: TableS15. Self-interaction genes in pregnant and non-pregnant cattle.

Additional file 17: TableS16. Non-pregnant animal with phenotype fine and coarse wood.

Additional file 18: TableS17. Annotated methylation genes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the UI Sheep Center, UI Vandal Brand Meats for assisting in the animal tissues collection for this project.

Peer review information

Andrew Cosgrove was the primary editor of this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team. The peer-review history is available in the online version of this article.

Authors’ contributions

B.M.M and S.D.M. conceived and designed the study. S.X. constructed statistical model and performed analyses. G.M.B, K.M.D, K.A.S and S.K detailed the related genes for tissues and pregnancy. M.R.S, J.M.T, K.M.D, G.M.B, K.A.S, D.K, P.V and B.M.M. collected the samples. S.X, B.M.M, S.D.M and D.H wrote the manuscript with the participation of all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative competitive award no. 2022–67016-36216 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture,2022-67016-36216,2022-67016-36216

Data availability

The sequencing data used in this study had been deposited in the SRA database under project number PRJNA1250396 [75]. The accessions for the public datasets are PRJNA512958 [76], PRJNA530286 [77], PRJNA760789 [78], and PRJNA760832 [79]. The source code for the analysis presented in this manuscript has been released under the MIT License and is publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/shang-qian/MethylationGE [80]. And a snapshot of the version used in this study has been archived on Zenodo with DOI: https://zenodo.org/records/15362009 [81]. The data that support this study are also available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Tissues were collected from healthy adult pregnant cattle and sheep, with all procedures approved by the University of Idaho Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under protocol numbers IACUC-2020–58 for sheep and IACUC-2021–21 for cattle.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: Jaccard index incorrectly had subset 1 in the numerator, and the absolute value bars were missing in the denominator. This has been corrected.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/3/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s13059-025-03632-4

Contributor Information

Brenda M. Murdoch, Email: bmurdoch@uidaho.edu

Stephanie D. McKay, Email: stephanie.mckay@missouri.edu

References

- 1.Deng S, Zhang J, Su J, Zuo Z, Zeng L, Liu K, Zheng Y, Huang X, Bai R, Zhuang L, et al. RNA m(6)A regulates transcription via DNA demethylation and chromatin accessibility. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poetsch AR, Plass C. Transcriptional regulation by DNA methylation. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(Suppl 1):S8-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Dou X, Chen C, Chen C, Liu C, Xu MM, Zhao S, Shen B, Gao Y, Han D, He C. N (6)-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science. 2020;367:580–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breiling A, Lyko F. Epigenetic regulatory functions of DNA modifications: 5-methylcytosine and beyond. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2015;8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo C, Hajkova P, Ecker JR. Dynamic DNA methylation: in the right place at the right time. Science. 2018;361:1336–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg MVC, Bourc’his D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:590–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m(6)A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boo SH, Kim YK. The emerging role of RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:400–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batista PJ, Molinie B, Wang J, Qu K, Zhang J, Li L, Bouley DM, Lujan E, Haddad B, Daneshvar K, et al. m(6)A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:707–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song P, Tayier S, Cai Z, Jia G. RNA methylation in mammalian development and cancer. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2021;37:811–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng X, Su R, Weng H, Huang H, Li Z, Chen J. RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 2018;28:507–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun T, Xu Y, Xiang Y, Ou J, Soderblom EJ, Diao Y. Crosstalk between RNA m(6)A and DNA methylation regulates transposable element chromatin activation and cell fate in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2023;55:1324–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu W, Shen H. When RNA methylation meets DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1261–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loriot A, Reister S, Parvizi GK, Lysy PA, De Smet C. DNA methylation-associated repression of cancer-germline genes in human embryonic and adult stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:822–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muyle AM, Seymour DK, Lv Y, Huettel B, Gaut BS. Gene body methylation in plants: mechanisms, functions, and important implications for understanding evolutionary processes. Genome Biol Evol. 2022;14:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Xiong F, Wu G, Liu W, Chen J, Wang B, Chen Y. Gene body methylation in cancer: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Clin Epigenetics. 2022;14:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He PC, He C. m(6) A RNA methylation: from mechanisms to therapeutic potential. EMBO J. 2021;40: e105977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang T, He WJ, Li C, Zhang JB, Liao YC, Song B, Yang P. Transcriptome-wide analyses of RNA m6A methylation in hexaploid wheat reveal its roles in mRNA translation regulation. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13: 917335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z, Shi X, Bao M, Song X, Zhang Y, Wang H, Xie H, Mao F, Wang S, Jin H, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis of RNA m(6)A methylation and gene expression changes among two arabidopsis ecotypes and their reciprocal hybrids. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12: 685189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshikawa M, Usami R, Kato S. Characterization of the arylsulfatase I (ARSI) gene preferentially expressed in the human retinal pigment epithelium cell line ARPE-19. Mol Vis. 2009;15:482–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vadakke-Madathil S, LaRocca G, Raedschelders K, Yoon J, Parker SJ, Tripodi J, Najfeld V, Van Eyk JE, Chaudhry HW. Multipotent fetal-derived Cdx2 cells from placenta regenerate the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:11786–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeyarajah MJ, Jaju Bhattad G, Kelly RD, Baines KJ, Jaremek A, Yang FP, Okae H, Arima T, Dumeaux V, Renaud SJ. The multifaceted role of GCM1 during trophoblast differentiation in the human placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119: e2203071119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang P, Peslak SA, Shehu V, Keller CA, Giardine BM, Shi J, Hardison RC, Blobel GA, Khandros E: Let-7 miRNAs repress HIC2 to regulate BCL11A transcription and hemoglobin switching. Blood. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Shahin M, Friedrich M, Gauly M, Holtz W. Pregnancy-associated glycoprotein (PAG) profile of Holstein-Friesian cows as compared to dual-purpose and beef cows. Reprod Domest Anim. 2014;49:618–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courtney JA, Wilson RL, Cnota J, Jones HN. Conditional mutation of Hand1 in the mouse placenta disrupts placental vascular development resulting in fetal loss in both early and late pregnancy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, Li C, Li Y, Wu S, Liu W, Lin T, Li M, Weng Y, Lin W, Qiu S. Characterization of METTL7B to evaluate TME and predict prognosis by integrative analysis of multi-omics data in glioma. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8: 727481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xin JW, Chai ZX, Jiang H, Cao HW, Chen XY, Zhang CF, Zhu Y, Zhang Q, Ji QM. Genome-wide comparison of DNA methylation patterns between yak and three cattle strains and their potential association with mRNA transcription. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2023;340:316–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu D, Zhao D, Wang N, Cai F, Jiang M, Zheng Z. Current status and prospects of GREM1 research in cancer (Review). Mol Clin Oncol. 2023;19:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su RW, Sun ZG, Zhao YC, Chen QJ, Yang ZM, Li RS, Wang J. The uterine expression of SEC63 gene is up-regulated at implantation sites in association with the decidualization during the early pregnancy in mice. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thach B, Samarajeewa N, Li Y, Heng S, Tsai T, Pangestu M, Catt S, Nie G. Podocalyxin molecular characteristics and endometrial expression: high conservation between humans and macaques but divergence in micedagger. Biol Reprod. 2022;106:1143–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He L, Zhu X, Yang Q, Li X, Huang X, Shen C, Liu J, Zha B. Low serum IL-17A in pregnancy during second trimester is associated with an increased risk of subclinical hypothyroidism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali S, Majid S, Ali MN, Banday MZ, Taing S, Wani S, Almuqbil M, Alshehri S, Shamim K, Rehman MU. Immunogenetic role of IL17A polymorphism in the pathogenesis of recurrent miscarriage. J Clin Med. 2022;11:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziller MJ, Gu H, Muller F, Donaghey J, Tsai LT, Kohlbacher O, De Jager PL, Rosen ED, Bennett DA, Bernstein BE, et al. Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2013;500:477–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi H, Wei J, He C. Where, when, and how: context-dependent functions of RNA methylation writers, readers, and erasers. Mol Cell. 2019;74:640–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Razin A, Cedar H. DNA methylation and gene expression. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:451–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Zhuang H, Fan W, Zhang X, Dong H, Yang H, Cho J. m(6)A RNA methylation impairs gene expression variability and reproductive thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2022;23:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Han H, De Carvalho DD, Lay FD, Jones PA, Liang G. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:577–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith J, Sen S, Weeks RJ, Eccles MR, Chatterjee A. Promoter DNA hypermethylation and paradoxical gene activation. Trends Cancer. 2020;6:392–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.An Y, Duan H. The role of m6A RNA methylation in cancer metabolism. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davenport KM, Ortega MS, Liu H, O’Neil EV, Kelleher AM, Warren WC, Spencer TE. Single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) uncovers trophoblast cell types and lineages in the mature bovine placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:e2221526120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darmochwal-Kolarz D, Michalak M, Kolarz B, Przegalinska-Kalamucka M, Bojarska-Junak A, Sliwa D, Oleszczuk J. The role of interleukin-17, interleukin-23, and transforming growth factor-beta in pregnancy complicated by placental insufficiency. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6904325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Lieshout EM, Knapen MF, Lange WP, Steegers EA, Peters WH. Localization of glutathione S-transferases alpha and pi in human embryonic tissues at 8 weeks gestational age. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierzchala M, Pierzchala D, Ogluszka M, Polawska E, Blicharski T, Roszczyk A, Nawrocka A, Urbanski P, Stepanow K, Cieploch A, et al. Identification of differentially expressed gene transcripts in porcine endometrium during early stages of pregnancy. Life (Basel). 2020;10:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang YH, Li Z, Zeng T, Chen L, Li H, Gamarra M, Mansour RF, Escorcia-Gutierrez J, Huang T, Cai YD. Investigating gene methylation signatures for fetal intolerance prediction. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0250032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whittington CM, Griffith OW, Qi W, Thompson MB, Wilson AB. Seahorse brood pouch transcriptome reveals common genes associated with vertebrate pregnancy. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:3114–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Renthal NE, Chen CC, Williams KC, Gerard RD, Prange-Kiel J, Mendelson CR. miR-200 family and targets, ZEB1 and ZEB2, modulate uterine quiescence and contractility during pregnancy and labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20828–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Hua G, Cai G, Ma Y, Yang X, Zhang L, Li R, Liu J, Ma Q, Wu K, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptome analyses reveal the key gene for wool type variation in sheep. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2023;14:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hua G, Yang X, Ma Y, Li T, Wang J, Deng X. m6A methylation analysis reveals networks and key genes underlying the coarse and fine wool traits in a full-sib Merino Family. Biology (Basel). 2022;11:1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, Jia G, Yu M, Lu Z, Deng X, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wen J, Lv R, Ma H, Shen H, He C, Wang J, Jiao F, Liu H, Yang P, Tan L, et al. Zc3h13 regulates nuclear RNA m(6)A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol Cell. 2018;69(1028–38): e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, Vagbo CB, Shi Y, Wang WL, Song SH, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okano M, Xie S, Li E. Cloning and characterization of a family of novel mammalian DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. Nat Genet. 1998;19:219–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin C, Lu Y, Jelinek J, Liang S, Estecio MR, Barton MC, Issa JP. TET1 is a maintenance DNA demethylase that prevents methylation spreading in differentiated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:6956–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi J, Xu J, Chen YE, Li JS, Cui Y, Shen L, Li JJ, Li W. The concurrence of DNA methylation and demethylation is associated with transcription regulation. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campeanu IJ, Jiang Y, Liu L, Pilecki M, Najor A, Cobani E, Manning M, Zhang XM, Yang ZQ. Multi-omics integration of methyltransferase-like protein family reveals clinical outcomes and functional signatures in human cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee E, Kim JY, Kim TK, Park SY, Im GI. Methyltransferase-like protein 7A (METTL7A) promotes cell survival and osteogenic differentiation under metabolic stress. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosen BD, Bickhart DM, Schnabel RD, Koren S, Elsik CG, Tseng E, Rowan TN, Low WY, Zimin A, Couldrey C, et al. De novo assembly of the cattle reference genome with single-molecule sequencing. Gigascience. 2020;9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davenport KM, Bickhart DM, Worley K, Murali SC, Salavati M, Clark EL, Cockett NE, Heaton MP, Smith TPL, Murdoch BM, Rosen BD. An improved ovine reference genome assembly to facilitate in-depth functional annotation of the sheep genome. Gigascience. 2022;11:giab096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo W, Fiziev P, Yan W, Cokus S, Sun X, Zhang MQ, Chen PY, Pellegrini M. BS-Seeker2: a versatile aligning pipeline for bisulfite sequencing data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14: 774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ligges UMM. Scatterplot3d - an R package for visualizing multivariate data. J Stat Softw. 2003;8:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marcais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, Zimin A. MUMmer4: a fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14: e1005944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lawrence M, Huber W, Pages H, Aboyoun P, Carlson M, Gentleman R, Morgan MT, Carey VJ. Software for computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9: e1003118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu G, Wang LG, He QY. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2382–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]