Abstract

The global clean energy transition requires the development of alternative energy technologies that rely on critical raw materials including lithium. Closed-basin brines, which generate ~40% of global lithium production, often have a circumneutral pH; however, during the evaporative concentration required for lithium production, the evaporated brines become acidic. Using primary geochemical and boron isotope data from the Salar de Uyuni (SDU), Bolivia combined with a modeling approach, we show that boron enrichment, which commonly co-occurs with lithium in closed-basin brines, is the primary factor in controlling the pH of brines from the SDU. We demonstrate that boron in global lithium- and boron-rich brines from closed basins exerts a similar influence on brine pH. The unique boron enrichments and its speciation can explain large proportions of alkalinity in these brines (~98% at the SDU), where evaporation alters the dissociation of boric acid, which triggers the formation of acidic evaporated brines.

The enrichment, speciation, and mineral precipitation of boron play a key role in determining the pH of lithium-rich brines.

INTRODUCTION

Brines are important sources of several mineral commodities including lithium, which is a key element required for the global green energy transition (1, 2). Now, ~40% of annual global lithium production is sourced from lithium-rich brines, primarily from a few salt pan (“salar”) deposits in the Lithium Triangle (Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia) in the high plateau of the central Andes, as well as from brine deposits in the Tibetan Plateau, notably the Qaidam Basin (Fig. 1) (3–5). These deposits were formed in continental closed basins in which a variety of geologic and climatic factors, including evaporative concentration, resulted in hypersaline brines containing high concentrations of lithium (5, 6).

Fig. 1. Map of the lithium-rich brines.

Map of closed-basin salar-type brine deposits. Those with brine data used in this study are shown as circles, whereas other notable salar-type lithium-rich brines not included in this study are also shown. Locations and map features were compiled from several sources (5, 83–85).

The geochemical evolution of brines in these closed basins is directly controlled by the chemical composition of inflow waters and their modifications through evaporation and precipitation of minerals (e.g., calcite, gypsum, and halite) (7). In contrast, conservative elements such as lithium and boron remain in solution and become enriched in the residual brines (6, 8). The incompatibility of lithium and boron in many major minerals means they often co-occur in silica-rich (more felsic) volcanic rocks and the associated low-saline tributaries and geothermal waters flowing into closed basins (9, 10). Consequently, the evaporated brines in salars are often highly enriched with both lithium and boron (10, 11). Traditionally, natural lithium-rich brines in closed basins are pumped from underlying aquifers into sequential evaporation ponds. This allows both lithium and boron to further concentrate while precipitating undesired salts (e.g., NaCl) prior to lithium extraction in a processing facility (8, 12).

The speciation of boron in natural waters is controlled by pH and typically limited to either boric acid [B(OH)3], which is the dominant species when the pH is <~9.2 in fresh water and <~8.6 in seawater and the borate ion [B(OH)4−], which is dominant at pH > ~9.2 in fresh water and pH > ~8.6 in seawater (13, 14). Salinity, temperature, and pressure all influence the apparent dissociation constant of boric acid, affecting equilibrium between these species (13–15). In most natural waters, the borate ion typically makes negligible contributions to alkalinity, and therefore does not affect pH (16). In some boron-rich brines, however, this contribution can be meaningful, accounting for ~4% of total alkalinity (TA) in seawater [TDS (total dissolved salts) ~35 g/kg, pH ~8.1] and up to ~58% at the Dead Sea (TDS ~280 g/kg, pH ~6.3), whereas the remainder of TA is from carbonate species (CO32− and HCO3−) (17, 18). These brines have relatively low concentrations of boron ~0.4 mmol/kg in seawater up to ~4.6 mmol/kg at the Dead Sea (17, 18). By contrast, natural lithium-rich brines (TDS ~150 to 300 g/kg) often have boron concentrations in excess of 20 to 50 mmol/kg, whereas in brines from evaporation ponds, this can reach ~300 to 600 mmol/kg (TDS > 300 g/kg) (8, 12, 19).

Although the pH of lithium-rich brines can vary substantially from pH ~2 [e.g., Salar de Gorbea, Chile (20)] to pH ~10.5 [e.g., Salar de Pintados, Chile (8)] (8, 21, 22), those of natural brines in the Lithium Triangle are often circumneutral with pH ~6 to 8 [e.g., Salar de Atacama, Chile; Salar de Uyuni (SDU), Bolivia] (10, 23). However, during evaporation, the pH can drop substantially (12, 19). This is particularly evident at the Salar de Atacama where the pH drops from ~7.4 to 2.5 in brines from evaporation ponds with corresponding increases in TDS rising from ~280 to 370 g/kg and in boron concentration rising from 57 to 310 mmol/kg (12). Given the highly elevated concentrations of boron in natural and evaporated lithium-rich brines, we hypothesize that boron species are a major alkalinity species and can exert a strong control on pH, an unstudied aspect of lithium-rich brines.

In this study, we investigate the role of boron in controlling the alkalinity and pH of lithium- and boron-rich brines. We use original and published geochemical and boron isotope data from natural and evaporated brines at the SDU in Bolivia (19), the largest known lithium brine resource (3, 24, 25), model boron speciation, and distribution, and integrate these to calculate variations in the dissociation of boric acid during evaporation. After corroborating our approach, we expand the study to include 323 additional lithium-rich brine analyses from different global salar-type deposits, including brines from the Lithium Triangle and the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1). Our analyses demonstrates the importance of boron in controlling the pH and alkalinity of global lithium-rich brines. Last, we develop an empirical equation for predicting the apparent dissociation constant of boric acid in global lithium-rich brines and hypersaline solutions.

The findings reported in this study have important implications for studying hypersaline brines, including lithium-rich brines, from terrestrial basins because boron is a common major element and directly associated with lithium in such systems. Previous studies have highlighted the dependence of boron speciation on pH and the utility of boron isotope geochemistry as a sensitive tracer to reconstruct paleoenvironmental and pH conditions as well as for detecting hydrological and water contamination issues (26–28). This study, however, presents the key role of boron and its speciation in controlling the alkalinity and thus the pH of boron-rich hypersaline brines. In the absence of carbonate alkalinity (CA), we show that the dissociation of boric acid in boron-rich hypersaline brines has a major role in buffering the brine pH. In natural brines, this often results in circumneutral pH and, in evaporation ponds, this leads to acidic conditions. Understanding the dynamics of boron in saline systems has important implications for studying the origins of hypersaline brines as well as for the management and environmental assessment of wastewaters and spent brines generated from lithium mining (19, 29). Furthermore, the transition to direct lithium extraction (DLE) technologies may require adjustments of the brine pH to increase extraction efficiency (30), in which boron will likely have an impact. Last, this research sheds light on potential biases in titration-based analytical procedures for determining TA and the concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in boron-rich brines.

RESULTS

Alkalinity and boron speciation in brines

The pH of natural waters are controlled through buffering reactions, a process typically dominated by DIC as the carbonic acid system (CO32−, HCO3−, and H2CO3*) and to a lesser degree the deprotonated species of other weak acids like boric acid, phosphoric acid, and water (15, 16). The enrichment or depletion of alkalinity species largely controls the pH of natural brines.

The borate ion is present in natural waters, aids in buffering, and is controlled by the conversion between boric acid [B(OH)3] and the borate ion [B(OH)4−] (15)

| (1) |

Combined, the ability of the deprotonated species of weak acids to accept protons controls TA, which is defined as the sum of the equivalents of the deprotonated species of weak acids minus the H+ concentration (15). Considering only the carbonic and boric weak acid systems, TA can be approximated as shown in Eq. 2

| (2) |

Salinity, discussed throughout the text as ionic strength (IS; as molal units, m), affects the dissociation constants of these weak acids, typically increasing dissociation with increasing IS. This results in a larger apparent dissociation constant (; calculated as shown in Eq. 3 for the boric acid system, , where is the activity of H+, and the square brackets indicates analytical concentration) and thus a lower apparent () (15). For example, the of the boric acid system, in fresh water (IS < ~0.05 m, TDS < ~1 g/kg) is ~9.2 (13), whereas in seawater, (IS ~0.7 m, TDS ~35 g/kg), it drops to ~8.6 (14) and, in the hypersaline Dead Sea (IS ~10 m, TDS ~280 g/kg), it reduces to ~6.3 (17)

| (3) |

Given that evaporation in the highly arid closed basins of the Lithium Triangle and Tibetan Plateau generates hypersaline brines (TDS often in the range of 150 to 300 g/kg) (5), the increase in dissociation constants should also be apparent in lithium-rich brines. Dissociation of the boric acid system has been modeled to show that increases ( decreases) with increasing salinity and has been well defined in salinities relevant to seawater and up to TDS ~45 g/kg (14). Despite recent advances using the geochemical software PHREEQC with a Pitzer ion interaction model where the of the Dead Sea brine was both modeled and calculated from available data (17), variations in the of hypersaline brines with much higher boron concentrations remain poorly constrained. In addition, at high salinities, the increased concentration of cations allows for complexes to form more readily with deprotonated weak acid species, which, in turn, may change pH and TA (15, 17, 31).

The Pitzer model in PHREEQC accounts for two complexes of the borate ion, with magnesium [MgB(OH)4+] and with calcium [CaB(OH)4+], each of which contribute one equivalent to alkalinity because they decomplex during an alkalinity titration, allowing B(OH)4− to become a proton acceptor.

As described in Eq. 1, boron typically exists in common natural waters as boric acid and the borate ion. However, in solutions with high total boron (TB) concentrations, the structural units of boric acid (trigonal planar, defined here as “B3”) and the borate ion (tetrahedral, defined here as “B4”) can polymerize to form polyborate ions (32, 33). In most natural waters, the concentrations of polyborates are negligible; however, when TB concentrations exceed ~50 mmol/kg, non-negligible concentrations of polyborates may form (34). Because TB concentrations in many lithium brines and evaporation ponds exceed this threshold (8, 12, 19), the formation of polyborates are expected. The Pitzer model in PHREEQC accounts for two polyborate species by the following equations (35)

| (4) |

| (5) |

The structure of B3O3(OH)4− is composed of two B3 units and one B4 unit, whereas that of B4O5(OH)42− is composed of two B3 and two B4 units (33). From these two polyborate species and the structural configurations of other polyborates (33) not included in the Pitzer model, it is clear that polyborate anions contribute a stoichiometrically equal amount of alkalinity to B4 structures in the polyborate ion [e.g., B3O3(OH)4− has one B4 unit with one equivalent of alkalinity].

For the purpose of discussion of the system, we can rewrite all equations to account for all species of boron (boric acid, borate, borate complexes, and polyborates) and the relative structural units of B3 and B4. Thus, we can simplify Eqs. 1, 4, and 5 into one basic equation, Eq. 6, which takes the common components from each dissociation equation where the formation of a B4 structure is accompanied by the release of an H+ and the dissociation of a B3 structure (water is also shown as a reactant to balance the equation) and where each B4 unit contributes one equivalent of alkalinity

| (6) |

Considering all B4 units as alkalinity species, the approximated TA equation (Eq. 2), with the same reference species, can be rewritten as

| (7) |

Geochemistry and composition of brines from SDU, Bolivia

Geochemical divides of inflow waters determine closed-basin brine chemical compositions, where precipitation of minerals during transport and evaporation of the inflow waters removes ion pairs in the stoichiometric proportions of the precipitated mineral (7, 36). The ion that has a greater proportion in the solution becomes enriched, whereas the relatively depleted ion becomes further depleted in the residual solution. For example, [SO42−] would increase and [Ca2+] would decrease when [SO42−] > [Ca2+] during CaSO4 precipitation (36). Alkaline salt lakes are typically generated from inflow waters with relatively high DIC and therefore high CA (sum of equivalents of CO32− and HCO3−) and relatively low calcium concentrations. This is because carbonate mineral precipitation allows for further enrichment of DIC when [CA] > 2[Ca] because CaCO3 consumes two equivalents of CA and the resulting brine then becomes rich in both DIC and CA, generating an alkaline lake. In contrast, inflow waters where [CA] < 2[Ca] results in the depletion of DIC and CA, leading to circumneutral pH brines (7, 36, 37). At the SDU, inflow waters precipitate calcite, largely removing DIC followed by gypsum and ulexite precipitation that has largely removed calcium, resulting in a Na-(Mg)-Cl brine [following the brine classification scheme of ref. (7)] with elevated concentrations of sulfate, lithium, and boron (38–40).

Natural brines from the SDU were collected from production wells operated by Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) in the southern section near the Rio Grande Delta (Fig. 1) through pumping from a subsurface halite and sand aquifer [see refs. (19, 25) for details]. Evaporated brines were collected from a series of eight sequential evaporation ponds, where the dominant minerals precipitating are halite in the first three ponds, sylvite in the fourth, mixed potassium salts in the fifth and sixth, lithium sulfate in the seventh, and bischofite in the eighth (19, 25).

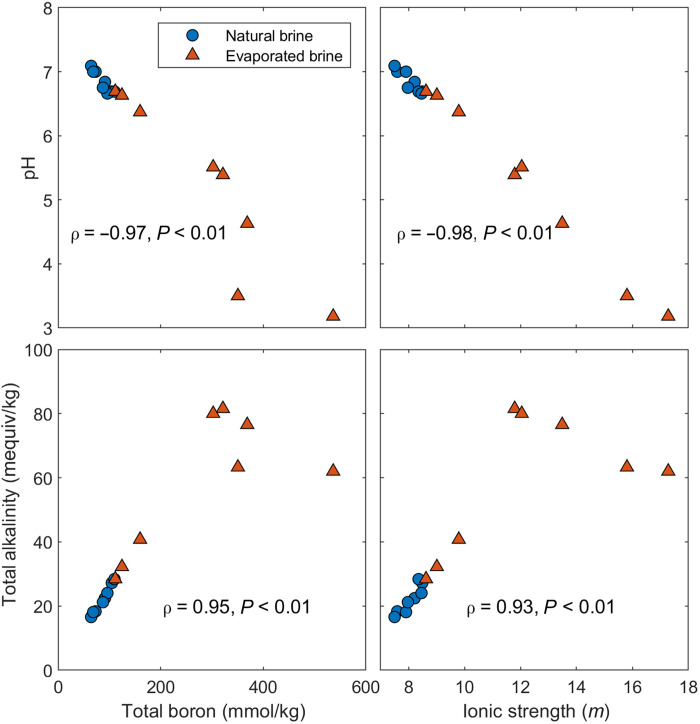

The natural brines of the SDU are characterized by a high TDS of 275 to 285 g/kg (IS of 7.5 to 8.5 m) and are relatively well buffered with a natural pH ranging from 6.7 to 7.1, whereas the TA ranges from 16.6 to 28.4 mequiv/kg and DIC is far lower (<0.35 mmol/kg). In the evaporation ponds, TDS increases to 358 g/kg (IS of 17.3 m), whereas the pH progressively decreases to 3.2 in the residual brine (Fig. 2). The progressive evaporation results in concentration increases of chloride, magnesium, lithium, and boron and decreases in sodium, sulfate, and potassium in the residual evaporated brines (fig. S1 and table S1), reflecting the sequential salt precipitation. Despite the apparent conservative rise in boron concentration, a fraction of boron is clearly entrained in the precipitated salts during the late stages of brine evaporation (ponds 6 to 8) (fig. S1 and table S2).

Fig. 2. Geochemical variation in brines from Salar de Uyuni (SDU), Bolivia.

Correlations of TB and IS with TA and pH in natural brines and in evaporated brines from the SDU. Both TA and pH show strong correlations with TB, suggesting that the alkalinity is tied to boron species.

The total possible alkalinity from DIC (assuming all DIC is in the CO32− form) in the natural brines ranges from 0.42 to 0.71 mequiv/kg, which could account for up to only ~3.3% of the TA, insufficient to be the dominant source of alkalinity, suggesting that other ions control the alkalinity of these brines. TB, however, is highly enriched, ranging from 73 to 111 mmol/kg, and correlates well with pH and TA (Fig. 2), indicating that borate could be the source of the alkalinity. These trends are extended with the evaporation ponds, where TB in the evaporated brines increases up to 536 mmol/kg and TA rises to >80 mequiv/kg, whereas the pH drops as low as 3.2 and the residual brines are virtually devoid of DIC (0.057 mmol/kg in the final pond). The only other potential contributor to TA at the SDU is arsenic, which can occur as either arsenic acid (H3AsO4) or arsenous acid (H3AsO3) depending on redox conditions (41). Total arsenic in the natural brines ranges from 0.01 to 0.12 mmol/kg but increases up to 0.66 mmol/kg in the evaporation ponds. At most, arsenic can contribute 3 equiv/mol in the most dissociated form (42), which would bring the maximum possible contribution to TA to 0.03 to 0.36 mequiv/kg in the natural brines and up to 1.98 mequiv/kg in the evaporated brines (0.3 to 3.2% of TA), exceeding the potential contributions from DIC, and yet far below that of TB. Consequently, we conclude that B4 is likely the major alkalinity species in brines of the SDU, whereas DIC and arsenic might contribute only relatively minor fractions to TA.

Boron speciation in SDU brines

Boron speciation was determined using a Pitzer ion interaction model as implemented in PHREEQC (35), which accounts for free boric acid and borate as well as the metal borate complexes MgB(OH)4+ and CaB(OH)4+. In addition, two polyborate ions, B3O3(OH)4− and B4O5(OH)4−2, the structures of which are composed of both B4 and B3, in 1:2 and 2:2 ratios are included (33).

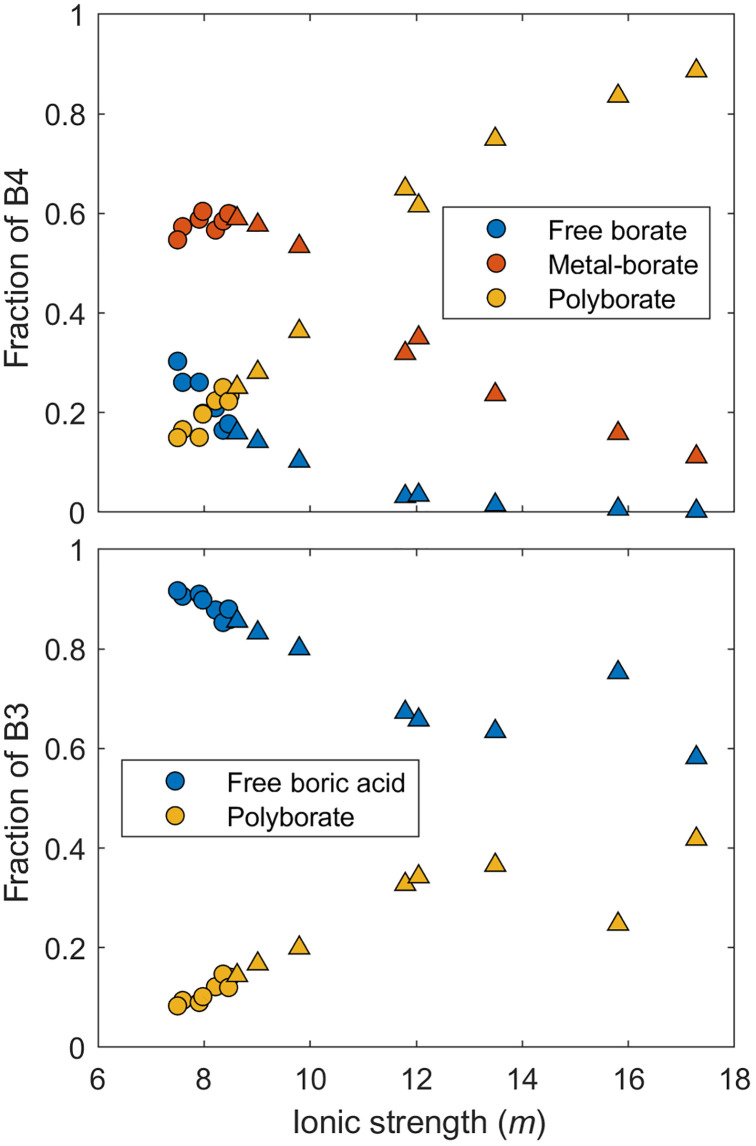

As predicted in the model for the natural brines, free boric acid is the dominant species (~66% of TB) whereas metal-borate complexes account for ~15%, polyborates ~13%, and the free borate ion ~6%. From a structural perspective, ~23% of TB in the natural brines is in the B4 form with the remaining ~77% is in the B3 form. The model predicts that a non-negligible fraction, up to 25%, of the B4 (as calculated from Eqs. 10 and 11 in the Materials and Methods) in the natural brines is derived from polyborate species, whereas the rest is from metal-complexed and free borate ions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Control of speciation on the structural variability of boron at Salar de Uyuni (SDU), Bolivia.

Variations of the fractions of boron species contributing to the total B4 and B3 structures (B4 and B3) in the natural and evaporated brines from the SDU predicted from the model. The natural brines are shown as circles, whereas the evaporated brines are shown as triangles. In the natural brines (TDS 275 to 285 g/kg), metal-borate complexes and free borate ions account for most B4, whereas this shifts to dominantly polyborates in the boron-rich evaporated brines (TDS 285 to 360 g/kg). On the other hand, B3 is dominantly in the boric acid form rather than the in polyborate form in both natural and evaporated brines.

As evaporation progresses in the evaporation ponds, the fraction of TB in polyborates increases to ~53% whereas all other species decrease with free boric acid accounting for ~44%, metal borates ~3%, and free borate ions <1%. This means that polyborates begin to dominate and account for up to ~88% of B4 (Fig. 3). Therefore, as evaporation progresses and TB increases, the fractions of B4 as metal-borate complexes and free borate ions decrease to a minority (Fig. 3). Of the total B3 structures, free boric acid remains the dominant B3 species in the natural brines with <20% of B3 within the polyborate species; however, this proportion rises to 42% in the most evaporated brine (Fig. 3). The proportions of B4 to B3 in the brines remain nearly constant in the evaporation ponds despite variations in speciation except in pond 7 where the B4 fraction drops with an estimated 16 and 84% in the B4 and B3 forms, respectively. The sudden decrease in the proportion of B4 relative to B3 in pond 7 would suggest that some B4 is preferentially lost to the solid phase, which is consistent with the detected boron in the salts of pond 7 (fig. S1 and table S2).

Boron isotope variations in brines and salts from the evaporation ponds

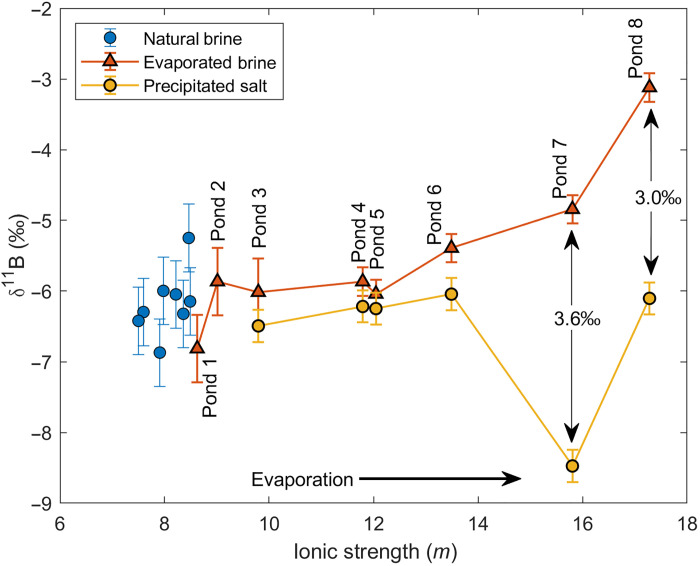

The δ11B values of the SDU natural brines fall within a narrow range from −5.2 to −6.9 per mil (‰). The δ11B values of brines in the evaporation ponds are within the same range, and yet the δ11B values in the final two ponds shift toward higher values, up to −3.1‰ in pond 8 (Fig. 4). The δ11B values of salts precipitating in the early evaporation ponds closely match their brine counterparts, −6.0 to −6.5‰ in the first six ponds, whereas salts from ponds 1 and 2 did not have enough boron for isotopic measurements. However, in the final two ponds, the brines become more enriched whereas the precipitated salts are relatively depleted in 11B as compared to the parent brine, with a δ11B difference of 3.0 to 3.6‰ (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Boron isotopes of natural and evaporated brines at Salar de Uyuni (SDU), Bolivia.

Variations of δ11B in SDU natural brines, brines from the evaporation ponds (linked in sequential order), and salt precipitates from the corresponding evaporation ponds. Note that the IS for the precipitated salts corresponds to that of the parent brines in the evaporation ponds. Although no variations in δ11B were observed in the natural brines and early stage evaporated brines, the δ11B value increases in the most evaporated brines (ponds 7 and 8) with corresponding lower δ11B of the precipitated salt, suggesting preferential removal of 10B into the salt phase.

Boron and alkalinity in global lithium-rich brines

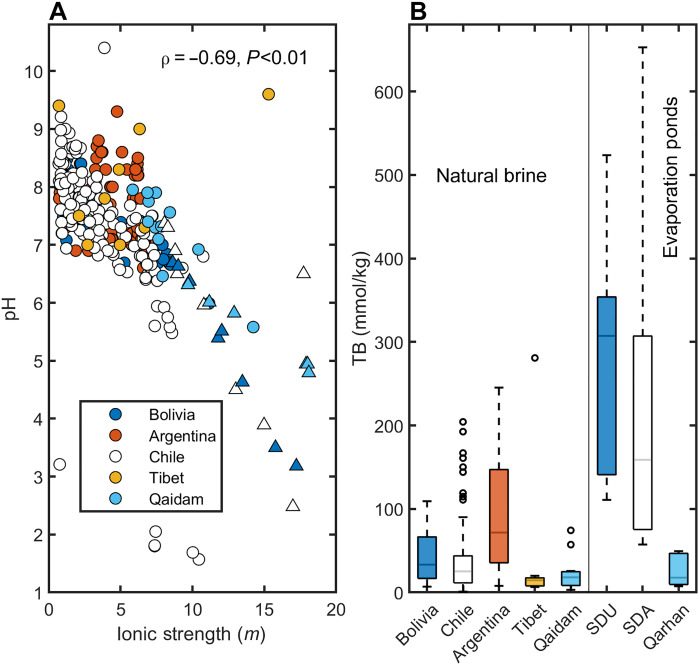

A dataset of brines from global salar-type deposits (n = 339, inclusive of the original data presented here from the SDU; table S3) was compiled and includes salt-lake and subsurface brines from the Lithium Triangle, the Tibetan Plateau, and the Qaidam Basin including brines from each region that have operations currently producing lithium. These regions are each characterized with many salar-type lithium-rich brines of differing chemistries. This dataset also includes brines that are evaporated inflow waters (with IS > 0.7 m, approximately that of seawater) to the salars, as well as brines from evaporation ponds from the Salar de Atacama in Chile (12) and the Qarhan playa in the Qaidam Basin of China (29). Consequentially, the dataset spans a large range of salinities and chemical compositions.

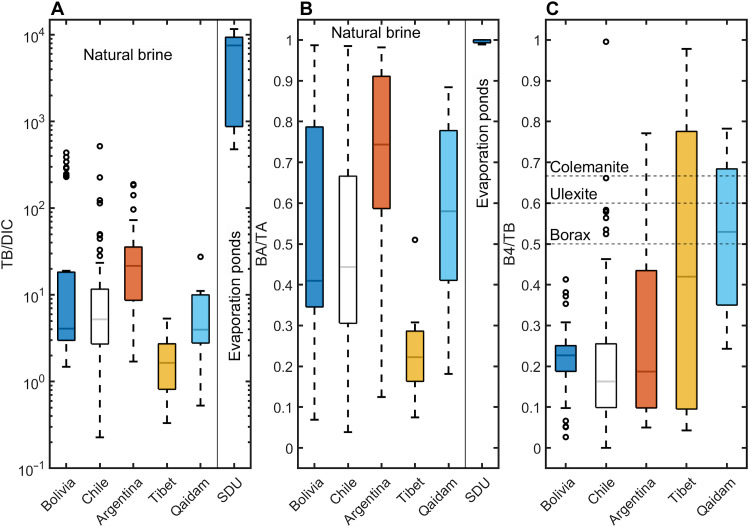

From this dataset, we show that the pH generally decreases as a function of IS (ρ = −0.69, P < 0.01) (Fig. 5A). This is consistent with previous findings showing pH generally decreasing with increasing salinity (22, 43–46). The chemistry of these brines varies considerably with alkaline lakes (pH > 8) and circumneutral lakes (6 < pH < 8), indicating that each brine follows different geochemical divides, resulting in the enrichment and depletion of different elements (36, 47). Many of the alkaline lakes are highly enriched in DIC, which explains their elevated pH (10, 22, 37) and a handful are slightly to highly acidic (e.g., Salar de Gorbea, Chile), resulting from the oxidation of sulfides (20). Regardless, boron is enriched in many of these brines as shown in Fig. 5B, up to several hundred mmol/kg. The evaporation pond data follow the same trends as at the SDU with decreasing pH and increasing IS and TB. The final evaporation pond at the Salar de Atacama has a pH of 2.5 and a TB concentration of 310 mmol/kg (12) [reported up to 650 mmol/kg TB (8)], whereas at the Qarhan Playa, the pH drops to 4.8 with a TB concentration of 50 mmol/kg (29).

Fig. 5. Variability in pH and boron enrichment of global brines.

(A) Measured pH versus IS in natural (circles) and evaporated (triangles) lithium-rich brines from major global basins color coded by country. (B) TB concentrations in natural and evaporated brines. Evaporated brines are from evaporation ponds from the SDU in Bolivia, the Salar de Atacama (SDA), in Chile, and the Qarhan Playa in the Qaidam Basin.

DISCUSSION

Role of boron speciation on apparent at the SDU

To discuss the influence of B4 on alkalinity and its control on pH, we calculate a simplified apparent dissociation constant (marked with an *) based on the total B3 and total B4 concentrations in solution (calculated as described in Materials and Methods from the Pitzer database in PHREEQC, which uses eqs. S1 to S5)

| (8) |

This is distinct from which, as calculated in Eq. 3, only considers the boric acid species and the borate ion, whereas accounts for all boron species in solution and their structural distributions as determined by conservative parameters in the brine (i.e., TA, elemental concentrations, and IS). For further discussion of , we will use for ease of interpretation and comparison.

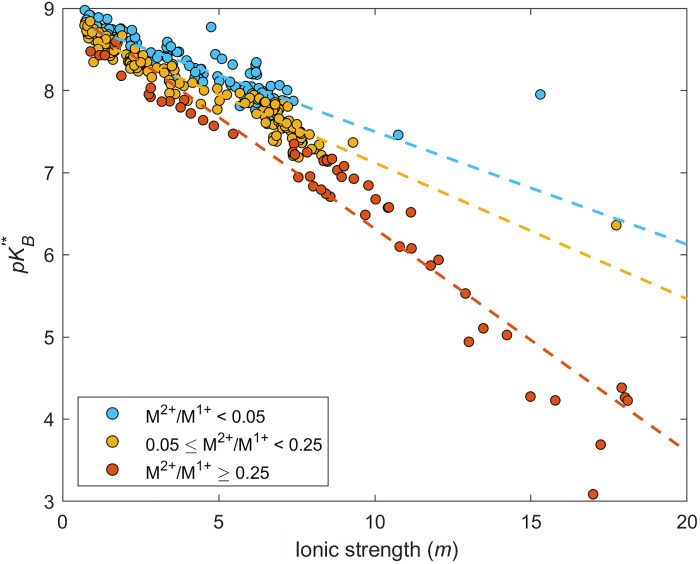

The apparent was calculated from the boron speciation distribution on a B4 and B3 structural basis (Eqs. 10 and 11) as described in Materials and Methods. The apparent of the natural brines at the SDU is calculated to a range of 7.1 to 7.6 and decreases with IS (Fig. 6). We can compare our to those published for both seawater and the Dead Sea because polyborate species are negligible in both, due to their relatively low TB concentrations, and therefore the published are effectively on a structural basis. Given the elevated IS of the SDU brines (7.5 to 8.5 m) relative to seawater (~0.7 m), we would expect the to be lower than that of seawater (~8.6) (14). By comparison, the of the Dead Sea, another high IS (~10.3 m) brine is ~6.3 and considerably lower (17). Although the TDS values of both brines (~280 g/kg at the Dead Sea and 275 to 285 g/kg at the SDU) are comparable, the difference in IS stems from the higher abundance of divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the Dead Sea brine relative to SDU brines, which causes the difference in the values. Golan et al. (17) demonstrated the relative effect of monovalent versus divalent cations, where divalent cations, presumably, complex more readily with the borate ion [e.g., MgB(OH)4+], pushing the equilibrium of Eq. 1 to the right. At both the Dead Sea and the SDU, Mg2+ and Na+ are the dominant divalent and monovalent cations, and yet the relative proportions of each are considerably different. At the SDU, the Mg/Na ratio is much lower (0.14 to 0.36) than at the Dead Sea (1.54). Furthermore, the natural SDU brines follow a clear trend with an inverse relationship between Mg/Na and (Fig. 6). This effect is propagated in the evaporation ponds where halite (NaCl) is continuously precipitated to remove Na+, whereas Mg2+ remains in solution, resulting in progressively increasing Mg/Na ratios (up to 63.2). A concomitant decrease in of the evaporation pond brines is also calculated, dropping to 3.7 and lending further evidence to the influence of complexing divalent cations with borate on the apparent . This can be explained in part not only by the increasing complexation of metal-borate species composed of divalent cations but also by the increasing dominance of polyborate ions.

Fig. 6. Variations in calculated dissociation constant at the SDU.

Variations of apparent with IS and Mg/Na mole ratios in the natural and evaporated lithium-rich brines from the SDU. The reduction of in the brines is controlled by both the IS and the increasing proportion of the divalent cation, Mg2+, over the monovalent cation, Na+, in the brines.

From the speciation modeling results, it is clear that polyborates are important species to consider and that they become a major species of boron in brines from the evaporation ponds (Fig. 3). This means that the dissociation of boric acid begins to be controlled by polyborate formation rather than borate formation as evaporation progresses and TB increases. Because our calculation of accounts for all B4 structures formed (as described in Materials and Methods), this further reduces the calculated . This means that polyborates are expected to become a major form of aqueous boron in such brines with high TB and that IS and metal-borate complexes are not the only factors affecting the reduction of .

The constant proportionality of total B4 to total B3, across all species, in all brine samples means that the decrease in nearly parallels that of pH, suggesting that pH drops as a result of changes in and the conservative increase in B concentration (and B4 and B3, respectively). If pH were dropping for another reason (e.g., addition of an acid such as oxidation of sulfide) and remained constant, the fraction of B3 would increase. However, because does decrease with evaporation, more B3 must dissociate during evaporation.

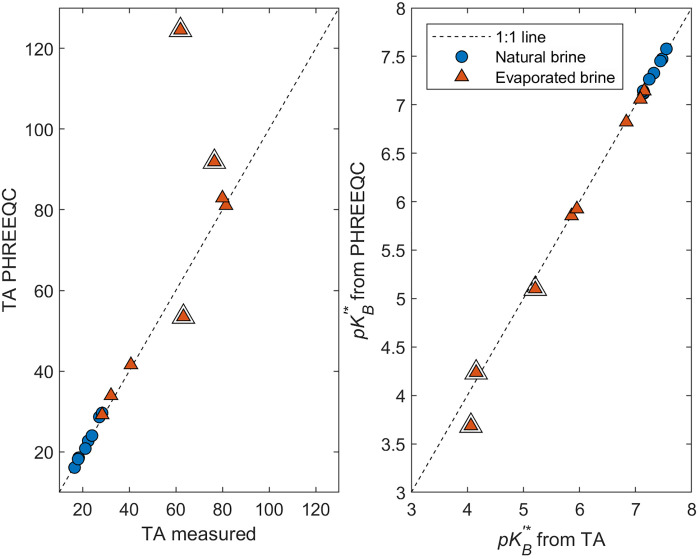

The TA determined by the Pitzer ion interaction model in PHREEQC agrees well with the measured TA in the SDU brines, within ±5%, indicating that we were not overlooking any major alkalinity species (Fig. 7). The exceptions are the final three evaporation ponds, which have measured TA values that are considerably different from the predicated values (both greater and lower values). Furthermore, the fraction of TA that can be attributed to BA (as predicted in PHREEQC) is 97.8 to 98.8% in natural brines and >99.0% in evaporated brines. This means that TA ≈ BA = [B4] because there is no meaningful contribution to TA from other ionic species and that the measured TA with measured TB can be used to determine the concentrations of B4 and B3 (i.e., [B4] = TA and [B3] = [TB]-[B4]). Using these values in Eq. 8, we empirically calculate the apparent from the measured data. The empirically derived and PHREEQC modeled values agree very well in all but the final three evaporation ponds (Fig. 7), further indicating that the modeled approach we used to determining is valid. The consistency between the theoretical approach with the Pitzer model in PHREEQC and our empirical results clearly reinforces the accuracy of our measurements and the modeled method. The deviation between measured and calculated TA in the final evaporation ponds does, however, suggest that the modeling approach may only be applicable to solutions of IS less than ~12 to 13 m.

Fig. 7. Validation of the modeling method.

Variations of modeled TA and calculated from PHREEQC versus measured TA and calculated from the measured TA in the natural and evaporated brines from the SDU. The high correlation between the modeled and measured alkalinity values verifies that boron occurrence and its species distribution in the lithium-rich brines are controlling the alkalinity of the brines. The double outlined triangles are the last three evaporation ponds with measured TA that deviate from the modeled TA.

The effect of boron on pH at the SDU

Our data indicate that increasing the IS, TB, and Mg/Na and decreasing the due to evaporation drives Eq. 6 (as a function of borate and polyborate formation) to the right. Therefore, with increasing evaporation, these equations are pushed toward the production of B4 in borate and polyborate ions, which liberates H+ into solution and therefore decreases pH. A similar decreasing pH during brine evaporation with increasing IS has been observed in several natural settings and experimental tests (29, 43, 45). However, in these cases, TB concentrations were much lower and DIC controlled the major alkalinity species. In contrast, at the SDU, boron is the dominant player contributing to TA and therefore in controlling pH. On the basis of the model predicted TA, the fraction of borate alkalinity (BA) contributing to TA (i.e., BA/TA) is >0.978 in all brines with the remaining contributions derived from CA and total OH− alkalinity. Therefore, it is clear that BA as B4 structures is the dominant control on alkalinity in the SDU brines.

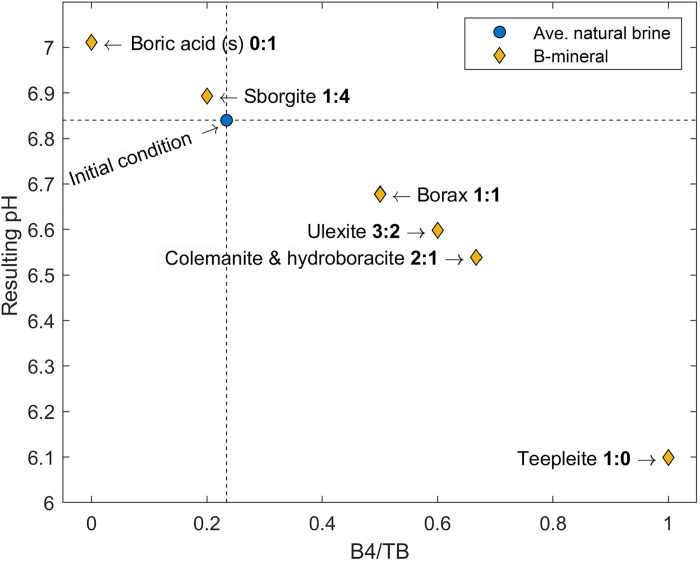

The sudden deviation between δ11B of the brines and precipitated salts detected in ponds 7 and 8, where the brines have greater δ11B values than the salts by ~3‰ (Fig. 4), indicates that boron is precipitating to a solid phase introducing isotope fractionation in which 10B is selectively incorporated into the salts. The deviation of TA from the nearly linear trend with B and with IS (Fig. 2) in the final evaporation ponds might also indicate preferential B4 precipitation due to the lower than the expected TA. Using the modeled and a fractionation factor of 26‰ where 10B is enriched in B4 as determined for seawater (48), we can estimate the δ11B values of B4 and B3. We assume that this boron isotope fractionation factor is applicable given that it has been experimentally established in seawater to be ~26‰ (26). Incorporation into precipitated salts of polyborates and various B-minerals containing mixed proportions of B3 and B4 would likely reduce the apparent overall isotope fractionation effect because the precipitate would not exclusively contain either B4 or B3 (49). From mass balance calculations using the 26‰ fractionation factor, the δ11B values of B4 in the natural brines and the first six evaporation ponds average −26.1‰, whereas B3 averages −0.1‰ (table S1). Using the predicted δ11B of B4 and B3 in the brine, the precipitated salt should have the same δ11B for B4 and B3, meaning that we can determine the fraction of B4 and B3 in the salt from the δ11B value of the bulk salt using mass balance calculations. This corresponds to ~32% B4 and ~68% B3 in salts precipitated in ponds 7 and 8. Many common borate minerals have a structural formula where B4/B3 ≥ 1 (49), and yet the relatively high proportion of B3 in the salt could be indicative of either (i) residual brine entrapped in the salts, (ii) precipitation of solid boric acid, among other B-minerals, which would result in a relatively high B3 proportion in the salt, or (iii) that B3 enriched polyborates [e.g., B3O3(OH)4−] might be directly incorporating in to precipitated salts as suggested in ref. (50), each would affect the δ11B values of the bulk precipitated salts. From the modeling results, we can see that solid boric acid is supersaturated in these final brines, thus suggesting that it could reasonably be incorporated into the precipitated salts (among other B-minerals) yet the relative influence of brine inclusions and polyborate incorporation cannot be ruled out. Regardless, the higher δ11B of the residual brine and the relatively lower δ11B of the bulk precipitated salt (inclusive of all precipitated salts) clearly indicate preferential removal of the 10B-enriched B4 structures from solution (i.e., B4/B3 salt > B4/B3 brine) into either precipitated B-minerals or as incorporated into other salts.

The precipitation of boron to the solid phase during brine evaporation can preferentially remove either B4 or B3 from solution. This means that B-mineral precipitation can act as an accelerating force for the reduction of pH during evaporation when B4 is preferentially removed into the bulk salt phase (i.e., where B4/B3 of the bulk precipitate is greater than B4/B3 of the brine; however, individual precipitated minerals may have different B4/B3 ratios), thus increasing the dissociation of B3 in solution to B4 to maintain equilibrium. The inverse is also true; if the B4/B3 of the precipitate is less than the brine, then the pH would conversely rise from the preferential removal of B3 and consequential shift in Eq. 6 to the left, consuming an H+. This would be the case if only solid boric acid were precipitating. The possible outcomes of B-mineral precipitation with different B4/B3 ratios are best demonstrated in Fig. 8, where we have modeled the average natural SDU brine and simulated the precipitation of 20% of TB into B-minerals of varied B4/B3 ratios (mineral precipitation follows eqs. S6 to S12) (49, 51). The resulting modeled pH does decrease when precipitating minerals with a B4/B3 greater than that of the source brine and increase when B4/B3 in the mineral is lower. This is also observed in the published experimental data from Oi et al. (52) where boron minerals were precipitated from synthetic solutions of varied IS and pH; after calculating the B4/B3 ratios in the solution, it can clearly be seen that pH typically rises when precipitating minerals with a lower B4:B3 ratio than the brine and vice versa (fig. S4).

Fig. 8. Role of boron mineral precipitation on pH.

Predicting the possible changes in pH to the average natural SDU brine as a result of the precipitation of different boron-bearing minerals with varied incorporation of B4 and B3 structures. This is shown on the x axis as the ratio of B4 to TB and shown in the graph as the ratio of B4:B3 for each mineral (bolded values). The average natural brine (~75 mmol/kg B), its pH (6.84), and the fraction of B4/TB (0.234) are shown as dashed lines. Using the model, we force the precipitation of various minerals to remove 20% of boron from the average natural brine (15 mmol/kg). This results in a change in pH of the residual brine where minerals with a greater B4:B3 ratio than the initial brine decrease pH and those with a lower ratio increase pH.

Given that the boron isotope fractionation follows the distribution and differential uptake/precipitation of B3 and B4, during evaporation, any combination of B-minerals (and boron incorporation into other evaporite minerals) can precipitate and thus the bulk B4/B3 ratio of all precipitating minerals will dictate not only the δ11B values of the solids but also the shift in pH of the residual brine during evaporation. Using the δ11B value of the salts and the brines in the final evaporation ponds, we can quantify the relative fraction of TB lost to the salts from solution by conducting a mass balance calculation. We do this for ponds 7 and 8 by taking the δ11B value of the prior pond, which we assumed to be the sole brine source (i.e., pond 6 to pond 7 and pond 7 to pond 8) and the δ11B value of the precipitated salt. Using this method, we estimate that ~15 and ~58% of boron is removed to the solid phase in ponds 7 and 8, respectively. Using the model, returning the respective amount of boron lost to the brines from ponds 7 and 8 in the appropriate B4/B3 ratios of the salts (as dissolution of solid boric acid, which is entirely B3, and borax, which has two B4 and two B3 units) would be expected to raise the pH of each brine, for pond 7 from 3.50 to 3.52 and pond 8 from 3.18 to 3.75. This is because the B4/B3 of the salts (~0.48) is greater than that of the brine (~0.35), and to return to equilibrium, some B4 must convert to B3, consuming an H+ via Eq. 6 and thus raising the pH. Because the inverse would have been true during precipitation, this simulation ultimately indicates that the preferential removal of B4 to the solid phase would have accelerated the drop in pH in the residual brine. Consequently, the combination of increasing δ11B in the final brines from the evaporation ponds (ponds 7 and 8) combined with the gradual reduction of pH and a decrease in δ11B of the bulk salts relative to the parent brine (Fig. 4) indicates selective removal of B4 over B3 into the solid phase. This intensifies the dissociation of B3 to B4 in the residual brine to maintain equilibrium.

It is important to note that the Pitzer model in PHREEQC, however, appears to inaccurately predict the minerals that would precipitate during evaporation because it primarily anticipates the precipitation of solid boric acid. This has a B4/B3 ratio of 0 (i.e., it is only B3), which is lower than that of the brines (~0.35) and would lead to a rise in pH during precipitation. This is contrary to the measured decrease in the pH during evaporation and the rise in δ11B of brines and the corresponding decrease in precipitated salts from the final evaporation ponds (Figs. 2 and 4), whereas the inverse would have occurred if primarily boric acid were precipitating. This clearly indicates preferential removal of B4 from solution, suggesting that the Pitzer model in PHREEQC is limited at such a high IS or is not equipped with the appropriate minerals or saturation information (a limited number of B-minerals are included in the Pitzer database) applicable to these hypersaline brines.

Boron and pH in global lithium brines

Following the method developed and validated for the SDU brines, we estimate the for global lithium-rich brines, which are commonly enriched with boron. All data points clearly show a reduction of with increasing IS (Fig. 9), following the same trend as shown at the SDU. From this, we can expect that some fraction of TB is in the B4 form and is thus affecting the TA and pH of these lithium-rich brines to varying degrees.

Fig. 9. Effect of cation complexation on the calculated dissociation constant.

Variations in calculated versus IS of natural and evaporated lithium-rich brines from major global basins. Data points are sorted based on the ratios of divalent cations to monovalent cations in solution (M2+/M1+). The data show that lower values are associated with greater M2+/M1+. Dashed lines are best fit linear regressions for each group to demonstrate the variability of as a function of M2+/M1+ and IS.

Divalent cations should complex more readily with B4 then monovalent cation, in which increasing their concentrations causes a decrease in . This is clearly demonstrated in the dataset of global lithium-rich brines. Figure 9 shows that greater divalent cation to monovalent cation ratios (M2+/M1+) tend to have lower values at the same IS. This further confirms the role of divalent cations in reducing proposed by Golan et al. (17) and thus highlights the importance of divalent cations in decreasing pH during brine evaporation.

The fraction of TB associated with polyborates is clearly better correlated with TB (ρ = 0.89, P < 0.01) than with IS (ρ = 0.40, P < 0.01; fig. S2). When TB is greater than ~50 mmol/kg, more than ~10% of TB is within polyborate species. When TB is greater than ~200 mmol/kg, polyborates become the dominant boron species. The high fractions of TB suggested to be in polyborate species of the global brines is consistent with the findings of the SDU brines.

Narrowing this dataset to natural brines with reported DIC (n = 295), it is clear that, in many cases, TB concentrations are far higher than DIC (Fig. 10A), suggesting that, in global brines, boron species may also be important contributors to alkalinity. Using the predicted TA from PHREEQC for each of these brines, we can estimate the fraction of BA contributing to the TA (assuming that TB and DIC are the only contributors to TA). Figure 10B shows that, in many of the natural lithium-rich brines, TA is composed predominantly of BA (mean ~55%), whereas in several instances, BA approaches 100% of the TA.

Fig. 10. Control of boron on alkalinity of global brines.

(A) The ratio of TB/DIC (molar) clearly demonstrates that boron is often more concentrated than DIC in natural brines. Loss of DIC and the conservative enrichment of boron lead to elevated TB/DIC ratios in the evaporation ponds. (B) Fraction of calculated BA to TA from modeling results. The data show that the TA is primarily composed of BA in many of the global lithium-rich brines. (C) Fraction of TB that is in the B4 form of natural brines. The dashed horizontal lines show the same ratio for several B-minerals, which are generally higher than that of the solution, indicating that their precipitation would lead to a decrease in pH via the preferential removal of B4 from solution (see text for explanation). Note that TB/DIC and BA/TA only include samples with reported DIC concentrations or reported TA. Evaporated brines are the data presented in this study for evaporation ponds from the SDU.

From the compiled water chemistry data of global lithium-rich brines (table S3), DIC is often reported as HCO3− or CO32−, having been measured via an alkalinity titration to either a set endpoint or a true endpoint, and assumes that this alkalinity is solely derived from CA (11, 53–56). Although boron corrections can be made to subtract the fraction of BA from TA to then calculate CA, a relevant to either seawater (~8.60) (14) or fresh water (~9.24) (13) is presumably used; this was done in at least one paper of the compiled dataset, but the used was not reported (57). Because these apparent values are higher than the values that are expected for such hypersaline brines and because many brines have lower pH than these values, this approach would drastically underestimate the fraction of B4 in solution and therefore underestimate BA. For example, from the average natural SDU brine with a pH of 6.8 and of 7.3, ~23.4% of TB would be in the B4 form; however, using the for seawater would underestimate this at only 1.7%. As a result, many reported DIC concentrations, measured from titration, may be overestimating DIC, neglecting the true contribution from BA to TA. This means that the BA/TA as shown in Fig. 10B may underestimate the contributions of BA to TA in global lithium-rich brines.

A subset of the compiled data for brines from Bolivia and Chile has reported TA as measured to a potentiometric endpoint (a true endpoint rather than a set endpoint) (21, 58) from which we can estimate the true contribution of BA to TA. Figure S3 shows data from individual salars and evaporated inflows and clearly shows that several brines have BA/TA > 0.95. This is notably the case in samples from Laguna Chiar Kota, Laguna Verde, and Laguna Mahama Koma from Bolivia and Salar de Carcote, Salar de Ascotan, Salar de Wheelwright, and Laguna del Francisco Negro in Chile. This indicates that our findings from the SDU are not unique and that B4 is by far the dominant alkalinity species in several other lithium-rich brines.

It has been well documented that many of the salars of the Lithium Triangle should evolve to alkaline conditions from modeling the evaporation of their inflows; however, nearly all salars have a circumneutral pH (23, 58). This deviation from the modeled evaporation trend has been attributed to the oxidation of aeolian sulfides/native sulfur deposited in inflow waters (23, 58). These studies, however, did not consider the effect of precipitation of B-minerals on pH. Given that many salars throughout the Andes have ulexite deposits precipitated from the evaporation of inflow waters and from brines (59, 60), the formation of ulexite would preferentially precipitate B4 from solution. This is because the B4:B3 ratio of ulexite is 3:2 (49) and inflow waters are relatively dilute, typically have a circumneutral to slightly alkaline pH (21, 58), and would have a relatively high (presumably similar to that of seawater ~8.6), meaning that most boron in inflow waters is in the B3 form and would therefore have a B4:B3 ratio less than that of ulexite. Ulexite also precipitates from some salar brines and is found within the salt crusts of several salars (60) meaning that this effect might not be restricted to evaporating inflows. From the compiled dataset, the vast majority of brines have a lower proportion of B4 than ulexite and other B-minerals common to salar deposits of the Lithium Triangle (Fig. 10C). As discussed with the SDU brines, precipitation of B-minerals with a B4:B3 ratio greater than the solution preferentially removes B4 and causes more B3 to convert to B4 to maintain equilibrium, liberating an H+ into solution. We suggest that this process could be a factor for preventing the formation of alkaline brines in the salar systems of the Lithium Triangle and may be an unconsidered geochemical divide during the formation of boron- and lithium-rich brines. The effect of sulfide oxidation, however, cannot be ruled out and ultimately this warrants further investigation.

Empirical equation for approximating in brines

Given the potential to overestimate DIC concentrations from the common titration methods, we propose tools that can provide more accurate geochemical data. As a best practice, when reporting DIC concentrations in brines with high TB, it is advisable to measure to a potentiometric endpoint and to calculate the fraction of BA using an accurate . To this end, we have developed an empirical equation, from the compiled dataset and the calculated , that can be used to quickly and accurately determine the of a brine based on a variety of factors that affect the apparent including pH, IS (molal units), TDS (g/kg solution), and major ion concentrations ([ion], mmol/kg solution) in a solution, following

| (9) |

Given the potential unreliability of the Pitzer model in PHREEQC at IS greater than ~13, we have limited this equation to only be applicable to brines of IS between 0.7 and 13.0. This equation appears to match the calculated from the PHREEQC-based method reasonably well with an SD of 0.08 for all data points and an R2 of 0.98. For a discussion of the validation of this equation, please see Supplementary Text. This equation is also applicable to non-lithium- and non-boron-rich brines and produces values clearly in line with that of the PHREEQC-method on the tested brines from various saline systems (fig. S5). As a result, the equation should be sufficient to approximate ; however, it should be limited to brines occurring at common surficial temperatures because the brines included in this study were all assumed to be 15°C. Although this equation can approximate , the best results will be derived from the PHREEQC method as described in Materials and Methods. The PHREEQC-based approach should also be applicable to a wide variety of temperatures including high temperatures (e.g., geothermal and oil and gas brines) because the Pitzer ion interaction model is capable at temperatures up to 200°C (61).

In terms of application, the can be treated as a regular for determining the ratio of B4 to B3 structures in solution using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (i.e., ). Because the concentration of B4 corresponds to BA, this can be applied to the TA to determine the relative contributions of boron and DIC to TA, assuming that contributions to TA from other species are negligible.

One of the major limitations of the data collected from the SDU and the compiled data of global lithium-rich brines is the accuracy of pH measurements. IS is well known to affect pH measurements with conventional pH probes, which are typically calibrated with low IS standards that do not matrix match that of the highly saline brines (62, 63). Experiments conducted by Golan et al. (63) suggest that this deviation would be less than ~0.15 pH units for IS less than 10 m (63). This would suggest that the measurements conducted in the present study and those reported by other authors are reasonably accurate and that the findings presented here would not be notably altered with more accurate pH measurements.

Implications for lithium- and boron-rich brine research

Closed basins with lithium-rich brines are found throughout the world with currently ~10 brine operations producing lithium and many others in developing stages to become operational in the near future. Most of these lithium-rich brines are also enriched in boron (3, 8, 10, 11) as shown in Fig. 5 and fig. S6. Brines from these continental basins are also sources of other elements such as potassium and potentially other critical raw materials (2, 8), meaning that they are under exploration and exploitation for other resources in addition to lithium. The findings presented in this study can help to explain changes in pH during evaporative concentration, a practice also used to further concentrate other elements such as potassium, especially if boron is present in elevated concentrations. Furthermore, this could be particularly important for understanding the potential environmental impacts of spent brines (residual brines after lithium extraction), which can leak from storage ponds or be discharged to the environment and thus alter the pH and chemistry of the natural brine (19). An example of this would be reinjection of spent brines to subsurface brine aquifers, a practice being considered at some operations to maintain hydraulic pressure and prevent basin sinking induced from the overpumping of lithium-rich brines (64). In addition, DLE encompasses many different technologies aiming to conserve water resources, circumvent evaporation ponds, and expedite the production process by preferentially removing lithium from the brine solution (30). This is currently a major topic of interest to researchers and lithium brine operations, and a key component of many DLE technologies is pH adjustment of the brine to ensure maximum lithium recovery (30). Because boron exerts such a strong control on pH in these brines, this may be an obstacle that requires large amounts of acid/base to make the relevant adjustments.

Beyond brine mining operations, understanding the role of boron geochemistry on the alkalinity budget of brines and salt lakes and having an accurate will be of broad interest to geoscientists. These findings will be particularly helpful for those using boron isotopes in brines and evaporites to address questions ranging from the origins of solutes in closed basins [e.g., (65, 66)] to reconstructing paleoclimate and paleo-brine pH variations as recorded in sediments, evaporites, and fossil brines [e.g., (27, 46, 67)] because such studies would address the relative distribution of B4 and B3 in solution. Furthermore, boron concentrations in geothermal and oil and gas brines, both of which are also being explored as a resource for their elevated lithium concentrations, can be similar to those of the brines presented here, suggesting that, in these cases, boron may prove to have a pivotal role in controlling pH (68–70). Overall, this study presents a unique and important perspective for understanding the geochemical evolution of brines within closed basins especially during further evaporation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and data compilation

All samples were collected in May of 2023 from the YLB operation at the SDU. Natural brines (n = 8) were pumped from wells of the same depth (well screen ~16 to 50 m deep) and that were discharged into a series of eight evaporation ponds. The natural brines were collected from discharge pipes that each represent an aggregate of several wells. The individual locations of these wells are not available, but the general locations can be seen in Fig. 1 in the southeastern section of the SDU. Evaporated brine samples were collected as pumped samples from the central region of each pond (n = 8). The first three ponds precipitate halite, whereas sylvite is formed in pond 4 and mixed potassium salts precipitate in ponds 5 and 6. Pond 7 forms lithium sulfate, which is harvested for lithium processing, whereas the residual brine in pond 8 forms bischofite (25). Brine samples were filtered (0.45 μm) in the field with a mixed cellulose ester (MCE) filter. For cation and trace metal analysis, this sample was collected in an acid-washed high-density polyethylene (HDPE) container and acidified with HNO3 (Fisher Optima grade) to pH < 2. For TA and anion analyses, the samples were stored in cleaned HDPE containers without headspace. An unfiltered aliquot was collected in a soda glass exetainer without headspace for DIC analysis. Salt samples were collected directly from each evaporation pond, dried in field, and stored in double-sealed polypropylene bags. The pH for all samples was measured in the field with a YSI EcoSense pH100A probe and regularly calibrated with NIST traceable standards.

Data for other lithium brines were compiled from published sources (8, 11, 12, 21, 22, 29, 38, 53–55, 57, 58, 71–75) and include brines from the Puna region of Argentina, the Altiplano of Bolivia, the Atacama of Chile, and the Tibetan Plateau including the Qaidam Basin of China (n = 324; table S3). Only data with complete chemical and physical parameters reported (at a minimum including pH, Cl, SO42−, Na, K, Mg, Ca, Li, and B), brines with an IS of >0.7 m (approximately greater than seawater), and an absolute charge balance error of <5% were included. This includes brines found throughout the major lithium-rich brine basins of the world regardless of lithium concentration. Because no temperature was reported for most samples, we assume a temperature of 15°C for all analyses. Conversions between reported units (mg/liter, mg/kg, molal, etc.) were done using the density and volume calculated in PHREEQC. All reported ISs are on a molal basis (mol/kg water) as calculated within PHREEQC, whereas all elemental concentrations are reported as mmol/kg solution unless specified otherwise.

Analytical procedures

Major cations (Li+, Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) and anions (Cl−, Br−, and SO42−) were measured with ion chromatography (IC) on Thermo Scientific Aquion IC and Dionex IC DX-2100 systems, respectively, whereas B and As were measured with a with a Thermo Fisher Scientific X-Series II inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer at Duke University (76, 77). Accuracy of measurements was monitored with regular measurements of an Atlantic Seawater standard (OSIL; table S4). All brines were diluted 800 to 1000x prior to analysis using deionized water (DI; >18.0 megohms/cm), whereas salts were dissolved in an excess of DI water in metal-free polypropylene centrifuge tubes.

DIC was measured at the UC Davis Stable Isotope Facility by the evolution to headspace of CO2 using phosphoric acid (78). Analyses were conducted on a Thermo Scientific GasBench II coupled to a Thermo Finnigan Delta Plus XL isotope ratio mass spectrometer. TA was determined using a Metrohm EcoTitrator with 1.5 M HCl, and the endpoint was evaluated using the Gran method (79). A relatively high concentration acid was used to prevent a dilution effect on the and minimize reduction of BA (see note in Supplementary Text and figs. S7 and S8).

Boron isotopes were measured on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Triton thermal ionization mass spectrometer in negative ion mode. 11B/10B ratios were measured as BO2− and normalized to NIST SRM-951 and presented in δ11B notation where δ11Bsample = ([11B/10Bsample]/[11B/10BNBS951]) − 1] × 1000. Replicate analyses of Atlantic seawater (n = 16) yield a mean value of 39.8 ± 0.86‰ (2SD), in good agreement with the accepted value of 39.61‰ (80). Sample preparation and analytical protocols and accuracy are thoroughly described by Leslie et al. (81) and briefly described here. Each sample was oxidized with H2O2 (Fisher Optima grade) for at least 24 hours, and ~4 ng of B was loaded directly onto rhenium filaments with a boron-free synthetic seawater load solution. Samples and standards ran between 860° and 930°C. Replicate analyses (>4) of every five to eight samples have a reproducibility of ±0.2 to 0.4‰ (2SD).

PHREEQC and calculations

Calculating the for all brines followed the method outlined by Golan et al. (17) with modifications. Here, we use PHREEQC (v 3.7.3) with a Pitzer ion interaction model (17, 35). The pitzer.dat database was chosen for its applicability to high salinity solutions (61). Golan et al. (17) only considered the polyborate species B3O3(OH)4− in their calculations but noted that PHREEQC estimated this species was negligible in their Dead Sea brine and did not consider the proportions of B3 and B4 in the polyborate species. It has, however, been predicted that polyborate species such as B3O3(OH)4− and B4O5(OH)42− may represent a higher proportion of TB in saline solutions with elevated TB concentrations (13, 33). Thus, this modified method also accounts for the relative fractions of B4 and B3 structures in each polyborate species. Equation 8 calculates the dissociation constant () of B3 to B4. The total B4 and B3 used as inputs to Eq. 8 are calculated from the PHREEQC output, where the species concentrations with a PHREEQC subscript are from the model predictions

| (10) |

| (11) |

The data input to PHREEQC for calculations included pH, temperature, density, and the total concentrations of Li, Na, K, Mg, Ca, Cl, Br, SO4, B, and DIC, whereas other parameters such as TA were only included as specified.

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric analyses were used including Spearman’s rank correlation where ρ represents the correlation coefficient, and statistical significance is represented by the P values (P). P values are reported based on significance as either P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, unless otherwise specified. The equation for estimating was made by fitting a linear regression model with the calculated from the PHREEQC-based method. All analyses were performed in MATLAB version 9.13.0 (82).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bolivian Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energy and Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos for authorizing, facilitating, and accompanying the sampling mission at the SDU. We thank K. Ledebur (Andean Information Network) who provided invaluable logistical and field support and G. A. Hall (Duke University) for support with lab work and method development. We thank the reviewers for their thorough and detailed reviews, which have improved the quality of this paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the Duke University Climate Research Innovation Seed Program, CRISP (A.V.); Duke University Josiah Charles Trent Memorial Foundation Endowment Fund (A.V.); and Duke University Graduate School International Dissertation Research Travel Award (G.D.Z.W.).

Author contributions: Writing—original draft: G.D.Z.W. and A.V. Conceptualization: G.D.Z.W. and A.V. Investigation: G.D.Z.W. Writing—review and editing: G.D.Z.W., A.V., and P.N. Methodology: G.D.Z.W. and A.V. Resources: A.V. Funding acquisition: G.D.Z.W. and A.V. Data curation: G.D.Z.W. Validation: G.D.Z.W., A.V., and P.N. Supervision: A.V. Formal analysis: G.D.Z.W. and A.V. Software: G.D.Z.W. and P.N. Project administration: A.V. Visualization: G.D.Z.W. and A.V.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S8

Legends for tables S1 to S3

Table S4

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.IEA, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions (International Energy Agency, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.DuChanois R. M., Cooper N. J., Lee B., Patel S. K., Mazurowski L., Graedel T. E., Elimelech M., Prospects of metal recovery from wastewater and brine. Nat. Water 1, 37–46 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3.B. W. Jaskula, Lithium (U.S. Geological Survey, 2024); https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2024/mcs2024-lithium.pdf.

- 4.J. W. Moon, “The Mineral Industry of China” in 2020-2021 Minerals Yearbook (2024), pp. 9.1–9.46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munk L. A., Hynek S. A., Bradley D. C., Boutt D., Labay K., Jochens H., Lithium brines: A Global perspective. Rev. Econ. Geol. 18, 339–365 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 6.D. Bradley, L. Munk, H. Jochens, S. Hynek, K. Labay, A Preliminary Deposit Model for Lithium Brines (2013-1006, U.S. Geological Survey, 2013).

- 7.H. P. Eugster, L. A. Hardie, “Saline lakes” in Lakes: Chemistry, Geology, Physics, A. Lerman, Ed. (Springer, 1978), pp. 237–293. [Google Scholar]

- 8.D. E. Garrett, “Part 1—Lithium” in Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium Chloride, D. E. Garrett, Ed. (Academic Press, 2004), pp. 1–235. [Google Scholar]

- 9.W. M. White, Geochemistry (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Risacher F., Fritz B., Origin of salts and brine evolution of Bolivian and Chilean salars. Aquat. Geochem. 15, 123–157 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Z., Tan H., Xue F., Li Y., Zhang X., Cong P., Santosh M., Zhang Y., Hydrochemical evolution and source mechanisms governing the unusual lithium and boron enrichment in salt lakes of northern Tibet. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 136, 5174–5190 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pueyo J. J., Chong G., Ayora C., Lithium saltworks of the Salar de Atacama: A model for MgSO4-free ancient potash deposits. Chem. Geol. 466, 173–186 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.V. Kochkodan, N. B. Darwish, N. Hilal, “The chemistry of boron in water” in Boron Separation Processes (Elsevier, 2015), pp. 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson A. G., Thermodynamics of the dissociation of boric acid in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Deep-Sea Res. 37, 755–766 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 15.W. Stumm, J. J. Morgan, Aquatic Chemistry: Chemical Equilibria and Rates in Natural Waters (John Wiley & Sons Inc., ed. 3, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 16.J. I. Drever, The Geochemistry of Natural Waters: Surface and Groundwater Environments (Prentice Hall, ed. 3, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golan R., Gavrieli I., Ganor J., Lazar B., Controls on the pH of hyper-saline lakes—A lesson from the Dead Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 434, 289–297 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.J. D. Burton, “Chapter 11: The ocean: A global geochemical system” in Oceanography: An Illustrated Guide (Manson Publishing Limited, 1996), pp. 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams G. D. Z., Vengosh A., Quality of wastewater from lithium-brine mining. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 12, 151–157 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Risacher F., Alonso H., Salazar C., Hydrochemistry of two adjacent acid saline lakes in the Andes of northern Chile. Chem. Geol. 187, 39–57 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 21.F. Risacher, H. Alonso, C. Salazar, Geoquímica en Cuencas Cerradas: I, II y III (51, Santiago, 1999); https://app.ingemmet.gob.pe/biblioteca/pdf/Geoq-5.pdf.

- 22.Zheng M., Liu X., Hydrochemistry of salt lakes of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Aquat. Geochem. 15, 293–320 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Risacher F., Alonso H., Salazar C., The origin of brines and salts in Chilean salars: A hydrochemical review. Earth Sci. Rev. 63, 249–293 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruber P. W., Medina P. A., Keoleian G. A., Kesler S. E., Everson M. P., Wallington T. J., Global lithium availability. J. Ind. Ecol. 15, 760–775 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.YLB, Memoria Institucional 2019 (Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos, 2019); https://www.ylb.gob.bo/memorias.

- 26.Foster G. L., Rae J. W. B., Reconstructing ocean pH with Boron isotopes in foraminifera. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 207–237 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer M. R., Helvaci C., The boron isotope geochemistry of the Kirka borate deposit, western Turkey. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 3599–3605 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vengosh A., Heumann K. G., Juraske S., Kasher R., Boron isotope application for tracing sources of contamination in groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 28, 1968–1974 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vengosh A., Chivas A. R., Starinsky A., Kolodny Y., Baozhen Z., Pengxi Z., Chemical and boron isotope compositions of non-marine brines from the Qaidam Basin, Qinghai, China. Chem. Geol. 120, 135–154 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vera M. L., Torres W. R., Galli C. I., Chagnes A., Flexer V., Environmental impact of direct lithium extraction from brines. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 149–165 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sass E., Ben-Yaakov S., The carbonate system in hypersaline solutions: Dead sea brines. Mar. Chem. 5, 183–199 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mesmer R. E., Baes C. F. Jr., Sweeton F. H., Acidity measurements at elevated temperatures. VI. Boric acid equilibriums. Inorg. Chem. 11, 537–543 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Y., Fang C., Fang Y., Zhu F., Polyborates in aqueous borate solution: A Raman and DFT theory investigation. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 83, 82–87 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bassett R. L., A critical evaluation of the thermodynamic data for boron ions, ion pairs, complexes, and polyanions in aqueous solution at 298.15 K and 1 bar. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 44, 1151–1160 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 35.D. L. Parkhurst, C. A. J. Appelo, Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3: A computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations (6-A43, U.S. Geological Survey, 2013).

- 36.Hardie L. A., Eugster H. P., The evolution of closed-basin brines. MSA Spec. Pap. 3, 273–290 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tosca N. J., Tutolo B. M., How to make an alkaline lake: Fifty years of chemical divides. Elements 19, 15–21 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rettig S. L., Jones B. F., Risacher F., Geochemical evolution of brines in the Salar of Uyuni, Bolivia. Chem. Geol. 30, 57–79 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Risacher F., Le cadre géochimique des bassins á évaporites de Andes Boliviennes. Cah. O.R.S.T.O.M. 10, 37–48 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Risacher F., Fritz B., Quaternary geochemical evolution of the salars of Uyuni and Coipasa, Central Altiplano, Bolivia. Chem. Geol. 90, 211–231 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukherjee A., Coomar P., Sarkar S., Johannesson K. H., Fryar A. E., Schreiber M. E., Ahmed K. M., Alam M. A., Bhattacharya P., Bundschuh J., Burgess W., Chakraborty M., Coyte R., Farooqi A., Guo H., Ijumulana J., Jeelani G., Mondal D., Nordstrom D. K., Podgorski J., Polya D. A., Scanlon B. R., Shamsudduha M., Tapia J., Vengosh A., Arsenic and other geogenic contaminants in global groundwater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 312–328 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cullen W. R., Reimer K. J., Arsenic speciation in the environment. Chem. Rev. 89, 713–764 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazar B., Erez J., Carbon geochemistry of marine-derived brines: I. 13C depletions due to intense photosynthesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 335–345 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rieke H. H. III, Chilingar G. V., Note on pH of brines. Sedimentology 1, 75–79 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stiller M., Rounick J. S., Shasha S., Extreme carbon-isotope enrichments in evaporating brines. Nature 316, 434–435 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X., Li Q., Qin Z., Fan Q., Du Y., Wei H., Gao D., Shan F., Boron isotope geochemistry of a brine-carbonate system in the Qaidam Basin, western China. Sediment. Geol. 383, 293–302 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowenstein T. K., Risacher F., Closed basin brine evolution and the influence of Ca–Cl inflow waters: Death valley and bristol dry lake California, Qaidam Basin, China, and Salar de Atacama, Chile. Aquat. Geochem. 15, 71–94 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nir O., Vengosh A., Harkness J. S., Dwyer G. S., Lahav O., Direct measurement of the boron isotope fractionation factor: Reducing the uncertainty in reconstructing ocean paleo-pH. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 414, 1–5 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oi T., Nomura M., Musashi M., Ossaka T., Okamoto M., Kakihana H., Boron isotopic compositions of some boron minerals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 3189–3195 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu H., Ma Y., Peng Z., Zhu F., Ma X., Influence of polyborate ions on the fractionation of B isotopes during calcite deposition. Chem. Geol. 622, 121387 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grice J. D., Burns P. C., Hawthorne F. C., Borate minerals. II. A hierarchy of structures based upon the borate fundamental building block. Can. Mineral. 37, 731–762 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oi T., Kato J., Ossaka T., Kakihana H., Boron isotope fractionation accompanying boron mineral formation from aqueous boric acid-sodium hydroxide solutions at 25°C. Geochem. J. 25, 377–385 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 53.López Steinmetz R. L., Salvi S., Gabriela García M., Peralta Arnold Y., Béziat D., Franco G., Constantini O., Córdoba F. E., Caffe P. J., Northern Puna Plateau-scale survey of Li brine-type deposits in the Andes of NW Argentina. J. Geochem. Explor. 190, 26–38 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.López Steinmetz R. L., Salvi S., Sarchi C., Santamans C., López Steinmetz L. C., Lithium and brine geochemistry in the Salars of the Southern Puna, Andean Plateau of Argentina. Econ. Geol. 115, 1079–1096 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia M. G., Borda L. G., Godfrey L. V., López Steinmetz R. L., Losada-Calderon A., Characterization of lithium cycling in the Salar De Olaroz, Central Andes, using a geochemical and isotopic approach. Chem. Geol. 531, 119340 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vignoni P. A., Jurikova H., Schröder B., Tjallingii R., Córdoba F. E., Lecomte K. L., Pinkerneil S., Grudzinska I., Schleicher A. M., Viotto S. A., Santamans C. D., Rae J. W. B., Brauer A., On the origin and processes controlling the elemental and isotopic composition of carbonates in hypersaline Andean lakes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 366, 65–83 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muller E., Gaucher E. C., Durlet C., Moquet J. S., Moreira M., Rouchon V., Louvat P., Bardoux G., Noirez S., Bougeault C., Vennin E., Gérard E., Chavez M., Virgone A., Ader M., The origin of continental carbonates in Andean salars: A multi-tracer geochemical approach in Laguna Pastos Grandes (Bolivia). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 279, 220–237 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Risacher F., Fritz B., Geochemistry of Bolivian salars, Lipez, southern Altiplano: Origin of solutes and brine evolution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 687–705 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chong G., Pueyo J. J., Demergasso C., Los yacimientos de boratos de Chile. Rev. Geol. Chile 27, 99–119 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 60.G. E. Ericksen, R. S. O., Geology and Resources of the Salars in the Central Andes (Open-File Report 88-210, U.S. Geological Survey, 1987).

- 61.Lu P., Zhang G., Apps J., Zhu C., Comparison of thermodynamic data files for PHREEQC. Earth Sci. Rev. 225, 103888 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ben-Yaakov S., Sass E., Independent estimate of the pH of Dead Sea brine. Limnol. Oceanogr. 22, 374–376 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Golan R., Gavrieli I., Lazar B., Ganor J., The determination of pH in hypersaline lakes with a conventional combination glass electrode. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 12, 810–815 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zelandez, Summit Nanotech, Recycling Brine for a Greener Future: Best Practices for Recycling and Reinjecting Lithium Brine (White Paper, 2024).

- 65.Wei H.-Z., Jiang S.-Y., Tan H.-B., Zhang W.-J., Li B.-K., Yang T.-L., Boron isotope geochemistry of salt sediments from the Dongtai salt lake in Qaidam Basin: Boron budget and sources. Chem. Geol. 380, 74–83 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y., Tan H., Cong P., Rao W., Ta W., Lu S., Shi D., Boron and lithium isotopic constraints on their origin, evolution, and enrichment processes in a river–groundwater–salt lake system in the Qaidam Basin, northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Ore Geol. Rev. 149, 105110 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Du Y., Fan Q., Gao D., Wei H., Shan F., Li B., Zhang X., Yuan Q., Qin Z., Ren Q., Teng X., Evaluation of boron isotopes in halite as an indicator of the salinity of Qarhan paleolake water in the eastern Qaidam Basin, western China. Geosci. Front. 10, 253–262 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sanjuan B., Gourcerol B., Millot R., Rettenmaier D., Jeandel E., Rombaut A., Lithium-rich geothermal brines in Europe: An up-date about geochemical characteristics and implications for potential Li resources. Geothermics 101, 102385 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 69.M. S. Blondes, K. J. Knierim, M. R. Croke, P. A. Freeman, C. Doolan, A. S. Herzberg, J. L. Shelton, U.S. Geological Survey National Produced Waters Geochemical Database, version 3.0 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2023).

- 70.McDevitt B., Tasker T. L., Coyte R., Blondes M. S., Stewart B. W., Capo R. C., Hakala J. A., Vengosh A., Burgos W. D., Warner N. R., Utica/Point Pleasant brine isotopic compositions (δ7Li, δ11B, δ138Ba) elucidate mechanisms of lithium enrichment in the Appalachian Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174588 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Álvarez-Amado F., Tardani D., Poblete-González C., Godfrey L., Matte-Estrada D., Hydrogeochemical processes controlling the water composition in a hyperarid environment: New insights from Li, B, and Sr isotopes in the Salar de Atacama. Sci. Total Environ. 835, 155470 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Borda L. G., Godfrey L. V., Del Bono D. A., Blanco C., García M. G., Low-temperature geochemistry of B in a hypersaline basin of Central Andes: Insights from mineralogy and isotopic analysis (δ11B and 87Sr/86Sr). Chem. Geol. 635, 121620 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haferburg G., Gröning J. A. D., Schmidt N., Kummer N.-A., Erquicia J. C., Schlömann M., Microbial diversity of the hypersaline and lithium-rich Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. Microbiol. Res. 199, 19–28 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.R. Sieland, N. Schmidt, A. Schön, J. Schreckenbach, B. Merkel, Geochemische, hydrogeologische und feinstratigraphische Untersuchungen am Salar de Uyuni (Bolivien) (TU Bergakademie Freiberg, 2011).

- 75.COCHILCO, SERNAGEOMIN, Compilación de informes sobre Mercado internacional del litio y potencial del litio en salares del norte de Chile (Secretaría de Minería, 2013); https://www.sernageomin.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Mercado-Internacional_Potencial-del-Litio-en-salares-del-norte-de-chile.pdf.

- 76.Kondash A. J., Redmon J. H., Lambertini E., Feinstein L., Weinthal E., Cabrales L., Vengosh A., The impact of using low-saline oilfield produced water for irrigation on water and soil quality in California. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 139392 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coyte R. M., Singh A., Furst K. E., Mitch W. A., Vengosh A., Co-occurrence of geogenic and anthropogenic contaminants in groundwater from Rajasthan, India. Sci. Total Environ. 688, 1216–1227 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Atekwana E. A., Krishnamurthy R. V., Seasonal variations of dissolved inorganic carbon and δ13C of surface waters: application of a modified gas evolution technique. J. Hydrol. 205, 265–278 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gran G., Determination of the equivalence point in potentiometric titrations. Part II. Analyst 77, 661–671 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Foster G. L., Pogge von Strandmann P. A. E., Rae J. W. B., Boron and magnesium isotopic composition of seawater. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, Q08015 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leslie D., Lyons W. B., Warner N., Vengosh A., Olesik J., Welch K., Deuerling K., Boron isotopic geochemistry of the McMurdo Dry Valley lakes, Antarctica. Chem. Geol. 386, 152–164 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 82.The MathWorks Inc., MATLAB, version 9.13.0 (R2022b) (2022); https://mathworks.com.

- 83.Benson T. R., Coble M. A., Dilles J. H., Hydrothermal enrichment of lithium in intracaldera illite-bearing claystones. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh8183 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]