Abstract

Sunitinib, a multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with specificity for VEGFR, KIT, FLT3, and PDGFR, has demonstrated clinical efficacy as a first- to third-line treatment for refractory renal carcinoma. Our previous research indicated that sunitinib malate suppresses intestinal polyp proliferation by downregulating IL-6 mRNA expression, suggesting a potential analogous mechanism in colorectal carcinoma inhibition. This study aimed to elucidate the pharmacological effects and molecular mechanisms of sunitinib malate on colorectal carcinoma using HCT116, RKO, HT29, and SW480 cell lines in vitro and HCT116-derived xenografts in nude mice in vivo. We employed a comprehensive array of experimental techniques, including CCK-8/MTT assays for cell viability, Transwell and/or wound healing assays for migration, and Western blot and immunohistochemistry for protein expression analysis. Our findings demonstrate that sunitinib malate significantly inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration in vitro. Moreover, in the xenograft model, sunitinib malate markedly suppressed colorectal tumor growth in vivo. Notably, we observed significant downregulation of c-MYC, TWIST, and MMP2 expression both in vitro and in vivo following sunitinib malate treatment. These results collectively suggest that sunitinib malate exerts its anti-colorectal carcinoma effects, at least in part, by disrupting the autocrine IL-6/STAT3/c-MYC/TWIST/MMP2 signaling axis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-02498-z.

Keywords: Sunitinib malate, Colorectal cancer cells, Autocrine IL-6/STAT3 pathway, c-MYC, TWIST, MMP2

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the top three most prevalent and lethal malignancies worldwide [1, 2]. Inflammation is a critical factor in all stages of CRC development [3], with inflammatory mediators, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6), playing a significant role [4, 5]. Extensive evidence suggests that IL-6 primarily functions in a paracrine manner to promote CRC cell proliferation and progression. At certain stage(s), cells in the microenvironment, such as cancer-associated fibroblasts [6], macrophages [4], and mesenchymal stem cells [7], secrete IL-6 to enhance their chemoresistance [4], proliferation [5], and/or migration abilities [8]. Furthermore, hypoxia-induced HIF-1 regulates IL-6 expression in colorectal cancer cells, thereby augmenting chemoresistance [9]. Mechanistically, IL-6 binding to IL-6R on the cancer cell membrane activates STAT3 and/or NF-κB pathways, either independently [4] or synergistically with TNF-α and Th17-type cytokines [5]. Activated STAT3 functions as a transcriptional regulator, promoting cell growth, migration, chemoresistance, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and cancer progression by modulating the expression of downstream targets. These include c-MYC [10, 11], TWIST [12, 13], MMP2 [14, 15], LRG1 [16], miR-204-5p [4], and miR-34a [8]. Genetic studies have revealed that IL-6 and JAK2 variants are associated with increased CRC risk in allele additive and genotype recessive models, respectively, while STAT3 variants show no significant association [17]. Moreover, activation of the JAK/STAT3pathway has been demonstrated to promote CRC cell growth [18]. Collectively, these findings highlight the crucial role of the IL-6-STAT3 pathway in CRC maintenance and progression, primarily through paracrine signaling. However, the potential autocrine function of IL-6 in CRC remains underexplored, warranting further investigation.

Sunitinib, a multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), primarily targeting VEGFR, KIT, FLT3, and PDGFR, has emerged as a first- to third-line therapeutic option for drug-resistant renal cell carcinoma and other malignancies [19]. Recent investigations have postulated that sunitinib may modulate inflammatory processes, given its inhibitory action on these receptor tyrosine kinases. This hypothesis was corroborated using the ApcMin/+ mouse model, which demonstrated sunitinib's capacity to suppress the expression of inflammatory mediators at the mRNA level and inhibit intestinal polyp proliferation, an early stage of intestinal tumorigenesis. The inflammatory factors regulated by sunitinib include IL-6, TNFα, IL-1α/β, and IFNγ, suggesting their promotive role in the initial stages of colorectal carcinogenesis [20]. Studies have shown that colorectal cancer cells express VEGFR, which promotes cell growth [21], KIT, which maintains stem cell characteristics [22, 23], and PDGFR [24, 25]. Additionally, elevated FLT3 levels have been observed in metastatic colorectal cancer [26]. However, the effects of sunitinib on inflammatory factors in advanced colorectal carcinoma and its ultimate clinical outcomes remain elusive. In this study, we demonstrate that sunitinib significantly inhibits cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration of colorectal cancer cells in vitro and suppresses tumor growth in vivo. These effects are mediated, at least in part, by down-regulation of the autocrine IL-6/STAT3/c-MYC/TWIST/MMP2 pathway both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, our findings provide evidence to suggest the existence of a positive regulatory loop between IL-6 and sunitinib's molecular targets in colorectal cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cell Culture

TThe HCT116 and HT29 cell lines (Shanghai Zhongqiao Xinzhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd., product Nos. ZQ0125 and BNCC337732) were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (BI, 010751ACS), while the RKO (Beyotime Biotechnology, product No. 6763) and SW480 (Servicebio Co. Ltd., product No. STCC10806P) cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (Servicebio Co. Ltd., product No. G4511), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (EXcell, FSP500), 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 10,000 U/mL penicillin (Servicebio Co. Ltd., product No.G4003). Cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO₂ and 95% humidity. (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Fig. 1.

Sunitinib malate inhibits colorectal carcinoma cell proliferation and migration. A CCK-8 assay shows the survival rate of HCT116 cells, and MTT assay shows the survival rates of RKO, HT29, and SW480 cells after 24-h treatment with sunitinib malate compared to vehicle. B Crystal violet staining results of HCT116 and RKO cell clones formed within 2 weeks after 20 μM sunitinib malate or vehicle treatment for 24 h. C Statistical analysis of HCT116 and RKO cell clone numbers. D Transwell assay results of HCT116 cells treated with 20 μM sunitinib malate for 24 h (scale bar: 50 μm). E Statistical analysis of transwell migration numbers of HCT116 cells. F Wound healing assay shows migration of RKO cells after 24-h and 48-h treatment with sunitinib malate or vehicle (scale bar: 100 µm). G Statistical results of wound healing rates. For CCK-8, MTT, and wound healing assays, one-way ANOVA analysis and multiple comparisons were performed on values normalized to vehicles, while for the transwell assay, an unpaired t-test analysis was performed between the sunitinib group and vehicle group. “*” indicate comparisons to vehicle: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sunitinib: sunitinib malate

Fig. 2.

Sunitinib malate significantly downregulates proliferation-related and migration-related proteins in colorectal carcinoma cells. Western blot (WB) assay shows protein levels of proliferation-related protein c-MYC (A, G), migration-related proteins TWIST (C, I), MMP2 (E, K), and loading control GAPDH or β-ACTIN in HCT116 and RKO cells treated with sunitinib malate or vehicle for 24 h. Normalized WB band intensities of c-MYC (B, H), TWIST (D, J), and MMP2 (F, L) in HCT116 and RKO cells treated with sunitinib malate or vehicle were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons. “*” indicate comparisons to vehicle: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sunitinib: sunitinib malate

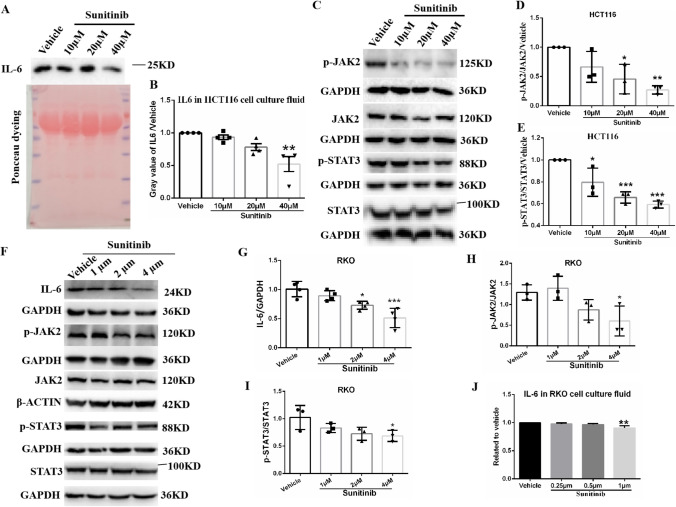

Fig. 3.

Sunitinib malate significantly inhibits the autocrine IL-6/STAT3 pathway in colorectal cancer cells. WB assay shows IL-6 levels in cell culture fluids of HCT116 cells treated with sunitinib malate for 24 h. Compared to HCT116 cells treated with vehicle, Ponceau staining assay confirmed equal loading of protein amounts in cell culture fluids. B Statistical results of normalized gray values of IL-6 in HCT116 cell culture fluid. WB shows levels of p-JAK2 and JAK2, p-STAT3 and STAT3, and their loading controls GAPDH or β-ACTIN in HCT116 cells (C) and RKO cells (F, including IL-6 in RKO cells) treated with sunitinib malate or its vehicle for 24 h. Statistical results of normalized gray values of p-JAK2/JAK2 ratio (D) and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratio E in HCT116 cells. G Statistical results of normalized gray values of IL-6 in RKO cells. Statistical results of normalized gray values of p-JAK2/JAK2 ratio (H) and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratio I in RKO cells. J Statistical results of normalized ELISA values of IL-6 in cell culture fluid of RKO cells treated with sunitinib and its vehicle. All WB values were normalized to vehicle after normalization to loading control GAPDH or β-ACTIN, and IL-6 ELISA values were normalized to vehicle. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons were performed between normalized values of sunitinib groups and the vehicle group. *Indicate comparisons to vehicle: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sunitinib: sunitinib malate

Animal studies

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) female BALB/c nude mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Hunan Slake Jingda Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. Two million HCT116 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the right groin of each mouse. Mice received daily oral administration of sunitinib malate (Shandong Xuan Hong Biological Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., CAS No. 341031-54-7, batch No. 202220201) at 30 mg/kg or 0.9% saline (vehicle control) for 21 days. Animals were housed in SPF facilities with ad libitum access to food and water under a 12–12 h light–dark cycle. All procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine. Ethical guidelines stipulated maximum tumor dimensions: length ≤ 2 cm, volume ≤ 2000 mm3, and weight ≤ 2 g (≤ 10% of body weight). As shown in Fig. 4C, all tumors met these criteria (maximum length: 17.19 mm; maximum volume: 1089.02 mm3 [calculated as 1/2 × length × width2]; maximum weight: 0.9682 g).

Fig. 4.

Sunitinib malate suppresses colorectal carcinoma growth in nude mice via IL-6/STAT3 pathway inhibition and downregulation of downstream targets. Nude mice bearing tumors derived from 2 million HCT116 cells subcutaneously transplanted into the groin region were treated with sunitinib malate or vehicle (0.9% sodium chloride) via oral gavage at 30 mg/kg once daily from Day 7 to Day 21. A Tumor morphology and anatomical distribution in mice. B Tumor volume progression from Day 1 to Day 21. C Excised tumor specimens from experimental cohorts. D Quantitative analysis of final tumor weights. E IHC staining of IL-6 and MMP2 in tumor sections (scale bar: 25 µm). F–G Optical density quantification of IL-6 (F) and MMP2 (G) mmunoreactivity. H Western blot analysis of IL-6, STAT3, p-STAT3, c-MYC, TWIST, MMP2, and loading control GAPDH in tumor lysates (Lanes 1–6: saline group; Lanes 1'–6': sunitinib group). I–M Densitometric analysis of IL-6 (I), p-STAT3/STAT3 ratio (J), and downstream targets c-MYC (K), TWIST (L), MMP2 (M). Frame inset: Schematic representation of tumor localization. Statistical comparisons between sunitinib and vehicle groups were performed using unpaired t-test: “*” indicate comparisons to vehicle: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sunitinib: sunitinib malate. Saline: 0.9% sodium chloride

Drug preparation

For in vitro studies, a 100 mM sunitinib malate stock solution was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). For in vivo studies, sunitinib malate was dissolved in 0.9% saline to 3 mg/mL.

Cell proliferation assay

HCT116 and RKO cells (3 × 103 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h. Cells were treated with sunitinib malate at specified concentrations for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed using CCK-8 (Meilun Biology, MA0218) or MTT (Solarbio, M8180; 5 mg/mL in PBS). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm (CCK-8) or 490 nm (MTT) using a microplate reader (Tecan, INFINITE 200 PRO). Survival rate was calculated as:

Colony formation assay

Cells (1.5 × 103/well) were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with 20 μM sunitinib malate or vehicle for 24 h. After 14 days in fresh medium, colonies were fixed with methanol (Xilong Science Co., Ltd., SJ0004) and stained with 2.5% crystal violet (Meilun Biological, S0905A). Colonies were counted using ImageJ (v1.52a).

Wound healing assay

Cells (4 × 105/well) were grown to confluence in 6-well plates. A sterile pipette tip was used to create a scratch, followed by treatment with sunitinib malate in serum-free medium. Images were captured at 0 and 24 h. Wound healing rate was calculated as: Healing rate (%) = 0 h area/(0 h area − 24/48 h area) × 100.

Transwell migration assay

Cells (6 × 104) in serum-free medium were seeded into Transwell inserts (Corning). Complete medium (800 μL) was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h, migrated cells were fixed with methanol, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and quantified using ImageJ (v1.52a).

Western blotting

Proteins (20 μg from cells, 40 μg from tissues) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were cut into strips near the appropriate marker corresponding to the protein bands shown in the antibody user manual. Subsequently, the membrane strips were incubated with primary antibodies as follows: GAPDH (Solarbio, K110496P, 1:10,000), β-actin (Hua’an Biotechnology, EM21002, 1:10,000), JAK2 (Solarbio, K002264P, 1:500), p-JAK2 (Abcam, ab32101, 1:500), STAT3 (Solarbio, K000124M, 1:1000), p-STAT3 (Cell Signaling, 9145, 1:1000), TWIST (Solarbio, K009993P, 1:500), MYC (Solarbio, K106458P, 1:1000), MMP2 (Solarbio, K002140P, 1:500), and IL-6 (Hua’an Biotechnology, EM-1701–58, 1:500). After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, signals were detected using ECL (Solarbio, PE001) and imaged (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc-XRS+).

IL-6 ELISA

Supernatants from sunitinib-treated cells were collected and centrifuged (3500 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C). IL-6 levels were quantified using a human IL-6 ELISA kit (He Peng Biotechnology, HP-E10140) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunohistochemistry assay

Tumor tissues were embedded in paraffin and prepared as 5 µm paraffin-embedded sections. Following dewaxing, rehydration, and microwave-induced antigen retrieval, the sections were washed three times with 1 × PBS. Non-specific binding sites were blocked by incubating the sections with 5% BSA at room temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with appropriate primary antibodies against IL-6 (Hua’an Biotechnology, EM-1701-58, 1:100) and MMP2 (Solarbio, K002140P, 1:100) at 4 °C overnight. After three 1 × PBS washes, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Solarbio, SE134, 1:100) at optimal concentration for 2 h at room temperature. Three additional 10-min washes were performed with 1 × PBS. Following hematoxylin counterstaining, the sections were rinsed with distilled water. The sections were mounted on glass slides using 80% glycerol as a mounting medium, covered with coverslips, and subjected to microscopic observation and image acquisition using an optical microscope (DMil8 manual, Leica Instruments, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Data from ≥ 3 independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA or Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism 6.02), with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results and discussion

Sunitinib malate significantly inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration

To evaluate the potential inhibitory effects of sunitinib on colorectal cancer progression, we employed two well-characterized colorectal cancer cell lines, HCT116, RKO, HT29 and SW480 as in vitro models. Data indicate that sunitinib malate significantly decreases colorectal cancer cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), and significantly inhibits clone formation (Fig. 1B, C) and cell migration (Fig. 1D–G, Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggest that sunitinib malate effectively suppresses colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration.

Sunitinib malate significantly downregulates c-MYC, TWIST, and MMP2 in colorectal cancer cells

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying sunitinib-mediated inhibition of colorectal cancer progression, we analyzed proliferation- and migration-promoting factors in HCT116, RKO, HT29 and SW480 cells using Western blotting. Compared to vehicle-treated controls, sunitinib significantly reduced the expression of the proliferation-promoting factor c-MYC (Fig. 2A, B, G, H), and significantly down-regulate migration-promoting factors, including TWIST (Fig. 2C, D, I, J) and MMP2 (Fig. 2E, F, K, L) in both HCT116 and RKO cells. Similar results were observed in SW480 and HT29 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings demonstrate that sunitinib malate suppresses c-MYC protein expression, leading to reduced proliferation and colony formation. Furthermore, sunitinib malate decreased TWIST and MMP2 levels, resulting in attenuated cell migration.

Sunitinib malate significantly inhibits autocrine IL-6/STAT3 pathway in colorectal cancer cells

To investigate the upstream mechanisms driving sunitinib-mediated reduction of c-MYC, TWIST, and MMP2, we assessed the IL-6/STAT3 pathway using Western blotting assay. Sunitinib malate significantly reduced secreted IL-6 level in HCT116 (Fig. 3A, B) and RKO (Fig. 3J) cell culture supernatants and downregulated intracellular IL-6 in RKO cells (Fig. 3F, G). Additionally, sunitinib decreased p-JAK2 /JAK2 ratio (Fig. 3C, D for HCT116, and 3F, H for RKO) and p-STAT3/STAT3 ratio (Fig. 3C, E for HCT116, and 3I for RKO) in both cell lines. Consistent results were observed in SW480 and HT29 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). These suggest that sunitinib malate inhibits autocrine IL-6/STAT3-c-MYC /TWIST/MMP2 pathway in colorectal cancer cells.

Sunitinib malate suppresses colorectal tumor growth in vivo

To assess the in vivo efficacy of sunitinib malate, nude mice bearing HCT116 cell-derived xenograft tumors were administered daily oral doses sunitinib (30 mg/kg) or Saline (vehicle). Sunitinib treatment significantly reduced tumor volumes from days 9 to 21 (Fig. 4A, B), with progressive inhibition over time. After 21 days of treatment, mice were euthanized under full anesthesia, and tumors were excised from the xenograft sites (inguinal region) and weighed. Sunitinib-treated mice exhibited significantly lower tumor weights compared to controls (Fig. 4C, D), indicating potent suppression of colorectal cancer growth in vivo.

Sunitinib malate significantly inhibits IL-6/STAT3/c-MYC/TWIST/MMP2 pathway in vivo

To explore the molecular mechanismof sunitinib-mediated tumor suppression in vivo, we analyzed proteins in HCT116-derived xenografts using Western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Compared to saline-treated controls, sunitinib malate significantly downregulated IL-6 (Fig. 4E, F, H, I), p-STAT3/STAT3 ratio (Fig. 4H, J), c-MYC (Fig. 4H, K), TWIST (Fig. 4H, L) and MMP2 (Fig. 4E, G, H, M). These results demonstrate that sunitinib malate inhibits the IL-6/STAT3/c-MYC/TWIST/MMP2 signaling axis in colorectal cancer in vivo.

Discussion

During tumorigenesis, the ability of early-stage neoplastic cells to evade inhibitory signals and exploit supportive cues from their microenvironment and through autocrine mechanisms is critical for their progression to malignancy. This process is exemplified by the paracrine and autocrine secretion of mitogenic and pro-survival factors. Inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, can also promote cancer development through paracrine signaling. Our study demonstrates that sunitinib malate significantly reduces IL-6 levels in both the cell culture supernatant and cellular extracts, as well as in tumors derived from the HCT116 colorectal cancer cell line. This reduction in IL-6 leads to the down-regulation of phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) and subsequently decreases the expression of downstream targets including c-MYC, TWIST, and MMP2, thereby inhibiting cell proliferation and migration. These experimental data appear to indicate that the IL-6-STAT3 pathway could be downregulated in CRC cells through sunitinib malate-mediated interference with autocrine IL-6 signaling mechanisms.

Our study found significant differences in the sensitivity to sunitinib malate between two molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer cell lines, HCT116 and RKO. The IC50 for HCT116 was 31.18 µM, more than five-fold higher than that of RKO (5.61 µM) (Fig. 1A, B). Moreover, the effective modulation of the IL-6/STAT3/c-MYC/TWIST/MMP2 pathway differed by more than an order of magnitude between the two cell lines (Figs. 2, 3). The known molecular differences between these cell lines are that HCT116 is KRASG13D; BRAF+;p53+ and RKO is KRAS+; BRAFV600E;p53+ [27]. These findings suggest that for TKIs targeting KIT, VEGFR, and FLT3, such as sunitinib, upstream KRAS mutations may confer greater drug resistance compared to downstream BRAF mutations, at least in the context of these two colorectal cancer cell lines. Preliminary research appears to lend credence to this hypothesis, as recent data show oncogenic KRAS mutations could play a role in modulating IL-6 levels within neoplastic cell populations [28]. The genotype of HT29 is KRAS+; BRAFV600E [27], and its IC50 is also lower than HCT116 but higher than RKO, while SW480, whose genotype is KRASG12V;BRAF+;p53R273H;P309S [27], has an IC50 comparable to HT29; Literature reported that p53+ deficiency in myeloid cells can increase their own and intestinal polyp Il-6 mRNA levels [29], These results suggest that p53 mutation status may also affect the sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to sunitinib. While these findings provide initial insights, future research should systematically assess whether similar mechanisms are observable across diverse colorectal cancer models.

Our findings suggesting that sunitinib may have the potential to decrease IL-6 levels are substantiated by several independent studies.The molecular targets of sunitinib, such as KIT and FLT3, have been associated with elevated IL-6 levels in various contexts, including certain leukemia cells, immune cells, inflammatory tissues, and cancer patients. For instance, mast cell lines expressing the D816-KIT variant, but not wild-type KIT or other variants, produce high levels of IL-6 [30]. This suggests that aberrant activation of KIT signaling may play a crucial role in IL-6 expression. Moreover, inhibition of KIT phosphorylation has been shown to decrease IL-6 levels [31]. Similarly, FLT3 overexpression can increase IL-6 production through the FLT3/ERK, MAPK/NFκB pathway in BaF3 cells. Analysis of 24 acute myeloid leukemia (AML) specimens revealed a modest positive correlation between FLT3 and IL-6 mRNA expression levels [32]. Additionally, elevated levels of both FLT3 and IL-6 were detected in monocytes cultured in bronchial epithelial cell-conditioned media [33]. In metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma, a complex relationship between IL-6 signaling and sunitinib sensitivity has been observed. Cells expressing low levels of IL-6Rα demonstrate increased sensitivity to sunitinib, while those with medium to high IL-6Rα expression also produce elevated levels of VEGF-A [34]. Clinical data further support this relationship, as patients with low serum IL-6 levels exhibit longer progression-free survival. Conversely, patients with high IL-6 levels often display elevated expression of PDGFR-β, VEGFR2, and VEGF-A [34]. These findings suggest the existence of a positive feedback loop between IL-6 and the molecular targets of sunitinib in colorectal cancer cells. Our study implies that sunitinib might potentially disrupt this feedback mechanism, which could in turn lead to the inhibition of cell proliferation and migration.

In summation, our study demonstrates that sunitinib inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration, at least partially through suppression of the IL-6/STAT3/c-MYC/TWIST/MMP2 signaling axis. Our findings suggest the existence of a hypothetical autocrine feedback loop within colorectal cancer cells, potentially mediated by IL-6, which regulates cellular proliferation and migration. The molecular targets of sunitinib, including KIT and FLT3, may potentiate this IL-6-driven pathway by augmenting both intracellular and secreted levels of IL-6. Consequently, this may reinforce the activity of sunitinib's targets and/or their ligands, potentially establishing an auto-amplifying regulatory circuit. The potential capacity of sunitinib to disrupt this feedback loop may contribute to its anti-tumor efficacy in colorectal cancer cells. These results provide novel insights into the mechanistic action of sunitinib in colorectal cancer and underscore the complex interplay between receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and inflammatory pathways. Further investigation efforts are warranted to comprehensively elucidate the molecular intricacies of this regulatory network and its implications for targeted therapeutic interventions in colorectal cancer.

Current evidence suggests that sunitinib, sorafenib, and regorafenib, three tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) investigated for colorectal cancer management, primarily exert their anti-angiogenic effects through VEGFR and PDGFR inhibition. These agents appear to disrupt tumor angiogenesis by suppressing vascular signaling pathways while concurrently targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK axis to modulate tumor proliferation. It should be noted that clinical application of these TKIs may encounter challenges related to primary or acquired resistance, accompanied by class-related adverse effects such as hand-foot syndrome, hypertension, fatigue, and gastrointestinal disturbances (particularly diarrhea and nausea) [35–37].

Sorafenib's mechanism has been characterized as multi-target inhibition encompassing Raf kinases (including BRAF), VEGFR-2/3, PDGFR-β, with additional activity against c-KIT and FLT3 [38, 39]. Emerging research indicates its ferroptosis-inducing potential in CRC models, though clinical experience suggests monotherapy efficacy remains suboptimal; Promising preclinical data demonstrate enhanced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic responses when combined with GW5074 (a C-RAF inhibitor) or immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1 agents) [39, 40]. Its resistance mechanisms have been partially attributed to PI3K/Akt pathway activation and GPX4 upregulation, prompting investigation into combinatorial approaches with PI3K inhibitors GDC-0941 (a PI3K inhibitors) [38] or 6-Shogaol (a natural product) [41]. Notably, nanoparticle formulations like SOR-CS-FU-NPs may offer improved tumor targeting and cytotoxic profiles [42].

Regorafenib exhibits broader target spectrum including VEGFR-1/2/3, TIE2 (vascular stabilization regulator), FGFR, and RET, potentially addressing multiple escape pathways (FGF, PDGF) [43, 44]. Experimental models suggest STAT3 inhibition via SHP-1 activation could suppress EMT and metastatic progression [45], while preliminary evidence points to immunomodulatory effects through macrophage regulation [44]. Therapeutically, its FDA approval for advanced CRC reflects a modest survival benefit (median 6.4 vs. 5.0 months with placebo); Current clinical exploration focuses on nivolumab combinations showing early promise in MSS-type and non-metastatic CRC populations [44, 46, 47]. Importantly, dose-escalation strategies have been proposed to improve tolerability without compromising efficacy [48].

In comparison, sunitinib's target profile (VEGFR-1/2/3, PDGFR-α/β, c-KIT, FLT3) has shown limited therapeutic activity in CRC monotherapy trials [49, 50]. Notably, combination with FOLFIRI was associated with increased toxicity without significant efficacy enhancement [50]. Its resistance is associated with FLT3 amplification or NRP1-dependent migration activation, and dosage optimization or combination with other targeted drugs (such as anti-c-Met antibodies) is needed [49, 51]. High-dose intermittent administration (700 mg every two weeks) may increase blood drug concentration, but clinical benefits still need to be validated [52].

Of particular scientific interest, a preclinical in vitro model has reported sunitinib-mediated promotion of colon cancer EMT and metastasis through neurofilament protein-1 (NRP1) inhibition [53], which contrasts with the observations from our experimental investigations. Methodological differences merit attention: The cited study employed prolonged low-dose exposure (0.1 µM × 5 weeks) in HCT116 cells [53], whereas our protocol utilized shorter-term, higher-concentration treatment (0.25-20 µM sunitinib malate × 24 h) across four CRC cell lines (HCT116, RKO, HT29, SW480). These findings collectively suggest that duration and dosing parameters may critically influence metastatic behavior outcomes, highlighting potential risks associated with chronic low-dose sunitinib exposure in CRC management.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Lai Chen and Zhiming Li provided funds to support this research and Lai Chen wrote this main manuscript text; Lai Chen, Ling Qian,Yi Yang, Bin Zhao and Pan Xu designed experiments of this research; Ling Qian, Yi Yang did most experiments and provided data; Bin Zhao, Pan Xu, Ziyan Hu, Liangwang Zhong, Qi Dai, Youbao Zhong, Chao Yang, Qinglong Shu, Ray P.S. Han and Yang Guan help finishing all these experiments and writing smoothly. Zhiming Li revised this manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Key R&D Program Project of Jiangxi Province, grant number 20243BBI91027. Key Science and Technology Projects of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education, grant number GJJ240821. Jiangxi Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of China, grant number 2022B1051.

Data availability

All research data in this paper are available on requestion.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All mice were cared for and treated in accordance with the operational guidelines approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine (reference number: JZLLSC20210006).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ling Qian and Yi Yang have contributed equally to the paper.

Contributor Information

Zhiming Li, Email: myluckylife@126.com.

Lai Chen, Email: chlai3383@foxmail.com.

References

- 1.Ahmed M. Colon cancer: a clinician’s perspective in 2019. Gastroenterol Res. 2020;13(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135(5):584–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Schmitt M, Greten FR. The inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(10):653–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin Y, Yao S, Hu Y, Feng Y, Li M, Bian Z, Zhang J, Qin Y, Qi X, Zhou L, Fei B, Zou J, Hua D, Huang Z. The immune-microenvironment confers chemoresistance of colorectal cancer through macrophage-derived IL6. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(23):7375–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Simone V, Franzè E, Ronchetti G, Colantoni A, Fantini MC, Di Fusco D, Sica GS, Sileri P, MacDonald TT, Pallone F, Monteleone G, Stolfi C. Th17-type cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-α synergistically activate STAT3 and NF-kB to promote colorectal cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2015;34(27):3493–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heichler C, Scheibe K, Schmied A, Geppert CI, Schmid B, Wirtz S, Thoma OM, Kramer V, Waldner MJ, Büttner C, Farin HF, Pešić M, Knieling F, Merkel S, Grüneboom A, Gunzer M, Grützmann R, Rose-John S, Koralov SB, Kollias G, Vieth M, Hartmann A, Greten FR, Neurath MF, Neufert C. STAT3 activation through IL-6/IL-11 in cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes colorectal tumour development and correlates with poor prognosis. Gut. 2020;69(7):1269–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Hu F, Li G, Li G, Yang X, Liu L, Zhang R, Zhang B, Feng Y. Human colorectal cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote colorectal cancer progression through IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rokavec M, Öner MG, Li H, Jackstadt R, Jiang L, Lodygin D, Kaller M, Horst D, Ziegler PK, Schwitalla S, Slotta-Huspenina J, Bader FG, Greten FR, Hermeking H. IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(4):1853–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu K, Zhan Y, Yuan Z, Qiu Y, Wang H, Fan G, Wang J, Li W, Cao Y, Shen X, Zhang J, Liang X, Yin P. Hypoxia induces drug resistance in colorectal cancer through the HIF-1α/miR-338-5p/IL-6 feedback loop. Mol Ther. 2019;27(10):1810–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S, Li J, Xie P, Zang T, Shen H, Cao G, Zhu Y, Yue Z, Li Z. STAT3/c-Myc axis-mediated metabolism alternations of inflammation-related glycolysis involve with colorectal carcinogenesis. Rejuv Res. 2019;22(2):138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Triner D, Castillo C, Hakim JB, Xue X, Greenson JK, Nuñez G, Chen GY, Colacino JA, Shah YM. Myc-associated zinc finger protein regulates the proinflammatory response in colitis and colon cancer via STAT3 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38(22):e00386-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MS, Lee HS, Kim YJ, Lee DY, Kang SG, Jin W. MEST induces Twist-1-mediated EMT through STAT3 activation in breast cancers. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26(12):2594–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng J, Wang H, Liang Y, Zhao L, Li Y, Yan Y, Zhao H, Zhang X, Zou F. miR-15a-5p enhances the malignant phenotypes of colorectal cancer cells through the STAT3/TWIST1 and PTEN/AKT signaling pathways by targeting SIRT4. Cell Signal. 2023;101: 110517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byun HJ, Darvin P, Kang DY, Sp N, Joung YH, Park JH, Kim SJ, Yang YM. Silibinin downregulates MMP2 expression via Jak2/STAT3 pathway and inhibits the migration and invasive potential in MDA-MB-231 cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37(6):3270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xuan X, Li S, Lou X, Zheng X, Li Y, Wang F, Gao Y, Zhang H, He H, Zeng Q. Stat3 promotes invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through up-regulation of MMP2. Mol Biol Rep. 2015;42(5):907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong B, Cheng B, Huang X, Xiao Q, Niu Z, Chen YF, Yu Q, Wang W, Wu XJ. Colorectal cancer-associated fibroblasts promote metastasis by up-regulating LRG1 through stromal IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2021;13(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Zhang W. Genetic variants in IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway and the risk of CRC. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(5):6561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei X, Wang G, Li W, Hu X, Huang Q, Xu K, Lou W, Wu J, Liang C, Lou Q, Qian C, Liu L. Activation of the JAK-STAT3 pathway is associated with the growth of colorectal carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(1):335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demlová R, Turjap M, Peš O, Kostolanská K, Juřica J. Therapeutic drug monitoring of sunitinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumors and metastatic renal cell carcinoma in adults—a review. Ther Drug Monit. 2020;42(1):20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, Xu P, Xiao Q, Chen L, Li S, Jian JM, Zhong YB. Sunitinib malate inhibits intestinal tumor development in male Apc(Min/+) mice by down-regulating inflammation-related factors with suppressing β-cateinin/c-Myc pathway and re-balancing Bcl-6 and Caspase-3. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90: 107128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia ZX, Zhang Z, Li Z, Li A, Xie YN, Wu HJ, Yang ZB, Zhang HM, Zhang XM. Anlotinib inhibits the progress of colorectal cancer cells by antagonizing VEGFR/JAK2/STAT3 axis. Eur Rev Med Pharmaco. 2021;25(5):2331–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomizawa F, Jang MK, Mashima T, Seimiya H. c-KIT regulates stability of cancer stemness in CD44-positive colorectal cancer cells. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2020;527(4):1014–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang MK, Mashima T, Seimiya H. Tankyrase inhibitors target colorectal cancer stem cells via AXIN-dependent downregulation of c-KIT tyrosine kinase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19(3):765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen RS, Dimberg J, Geffers R, Wågsäter D. Possible role and therapeutic target of PDGF-D signalling in colorectal cancer. Cancer Invest. 2019;37(2):99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moench R, Gasser M, Nawalaniec K, Grimmig T, Ajay AK, de Souza L, Cao M, Luo Y, Hoegger P, Ribas CM, Ribas-Filho JM, Malafaia O, Lissner R, Hsiao LL, Waaga-Gasser AM. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) cross-signaling via non-corresponding receptors indicates bypassed signaling in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2022;13:1140–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasegawa H, Taniguchi H, Nakamura Y, Kato T, Fujii S, Ebi H, Shiozawa M, Yuki S, Masuishi T, Kato K, Izawa N, Moriwaki T, Oki E, Kagawa Y, Denda T, Nishina T, Tsuji A, Hara H, Esaki T, Nishida T, Kawakami H, Sakamoto Y, Miki I, Okamoto W, Yamazaki K, Yoshino T. FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) amplification in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(1):314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed D, Eide PW, Eilertsen IA, Danielsen SA, Eknæs M, Hektoen M, Lind GE, Lothe RA. Epigenetic and genetic features of 24 colon cancer cell lines. Oncogenesis. 2013;2(9): e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colyn L, Alvarez-Sola G, Latasa MU, Uriarte I, Herranz JM, Arechederra M, Vlachogiannis G, Rae C, Pineda-Lucena A, Casadei-Gardini A, Pedica F, Aldrighetti L, López-López A, López-Gonzálvez A, Barbas C, Ciordia S, Van Liempd SM, Falcón-Pérez JM, Urman J, Sangro B, Vicent S, Iraburu MJ, Prosper F, Nelson LJ, Banales JM, Martinez-Chantar ML, Marin J, Braconi C, Trautwein C, Corrales FJ, Cubero FJ, Berasain C, Fernandez-Barrena MG, Avila MA. New molecular mechanisms in cholangiocarcinoma: signals triggering interleukin-6 production in tumor cells and KRAS co-opted epigenetic mediators driving metabolic reprogramming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He XY, Xiang C, Zhang CX, Xie YY, Chen L, Zhang GX, Lu Y, Liu G. p53 in the myeloid lineage modulates an inflammatory microenvironment limiting initiation and invasion of intestinal tumors. Cell Rep. 2015;13(5):888–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobío A, Bandara G, Morris DA, Kim DK, O’Connell MP, Komarow HD, Carter MC, Smrz D, Metcalfe DD, Olivera A. Oncogenic D816V-KIT signaling in mast cells causes persistent IL-6 production. Haematologica. 2020;105(1):124–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drube S, Schmitz F, Göpfert C, Weber F, Kamradt T. C-Kit controls IL-1β-induced effector functions in HMC-cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;675(1–3):57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi S, Harigae H, Ishii KK, Inomata M, Fujiwara T, Yokoyama H, Ishizawa K, Kameoka J, Licht JD, Sasaki T, Kaku M. Over-expression of Flt3 induces NF-kappaB pathway and increases the expression of IL-6. Leukemia Res. 2005;29(8):893–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gazdhar A, Blank F, Cesson V, Lovis A, Aubert JD, Lazor R, Spertini F, Wilson A, Hostettler K, Nicod LP, Obregon C. Human Bronchial epithelial cells induce CD141/CD123/DC-SIGN/FLT3 monocytes that promote allogeneic Th17 differentiation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilskog M, Bostad L, Edelmann RJ, Akslen LA, Beisland C, Straume O. Tumour cell expression of interleukin 6 receptor α is associated with response rates in patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2018;4(2):114–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martchenko K, Schmidtmann I, Thomaidis T, Thole V, Galle PR, Becker M, Möhler M, Wehler TC, Schimanski CC. Last line therapy with sorafenib in colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. World J Gastroentero. 2016;22(23):5400–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie H, Lafky JM, Morlan BW, Stella PJ, Dakhil SR, Gross GG, Loui WS, Hubbard JM, Alberts SR, Grothey A. Dual VEGF inhibition with sorafenib and bevacizumab as salvage therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the phase II North Central Cancer Treatment Group study N054C (Alliance). Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:431441343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karasic TB, Rosen MA, O’Dwyer PJ. Antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors in colorectal cancer: is there a path to making them more effective? Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 2017;80(4):661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Wang J, Chen L. TIMP1 represses sorafenib-triggered ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Immunopharm Immunot. 2023;45(4):419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu J, Chang Y, Hsieh C, Huang S. The synergistic cytotoxic effects of GW5074 and sorafenib by impacting mitochondrial functions in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 925653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim EH, Lee WS, Oh H. Tumor-treating fields in combination with sorafenib curtails the growth of colorectal carcinoma by inactivating AKT/STAT3 signaling. Transl Cancer Res. 2022;11(8):2553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehanna MG, El-Halawany AM, Al-Abd AM, Alqurashi MM, Bukhari HA, Kazmi I, Al-Qahtani SD, Bawadood AS, Anwar F, Al-Abbasi FA. 6-Shogaol improves sorafenib efficacy in colorectal cancer cells by modulating its cellular accumulation and metabolism. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;262: 155520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Y, Liu J, Ma S, Yang X, Zou Z, Lu W, Wang T, Sun C, Xing C. Fabrication of polymeric sorafenib coated chitosan and fucoidan nanoparticles: Investigation of anticancer activity and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Heliyon. 2024;10(14): e34316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ek F, Blom K, Selvin T, Rudfeldt J, Andersson C, Senkowski W, Brechot C, Nygren P, Larsson R, Jarvius M, Fryknäs M. Sorafenib and nitazoxanide disrupt mitochondrial function and inhibit regrowth capacity in three-dimensional models of hepatocellular and colorectal carcinoma. Sci Rep-UK. 2022;12(1):8943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arai H, Battaglin F, Wang J, Lo JH, Soni S, Zhang W, Lenz H. Molecular insight of regorafenib treatment for colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;81: 101912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan L, Teng H, Shiau C, Tai W, Hung M, Yang S, Jiang J, Chen K. Regorafenib (Stivarga) pharmacologically targets epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(39):64136–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukuoka S, Hara H, Takahashi N, Kojima T, Kawazoe A, Asayama M, Yoshii T, Kotani D, Tamura H, Mikamoto Y, Hirano N, Wakabayashi M, Nomura S, Sato A, Kuwata T, Togashi Y, Nishikawa H, Shitara K. Regorafenib plus nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or colorectal cancer: an open-label, dose-escalation, and dose-expansion phase Ib trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(18):2053–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fakih M, Raghav KPS, Chang DZ, Larson T, Cohn AL, Huyck TK, Cosgrove D, Fiorillo JA, Tam R, D’Adamo D, Sharma N, Brennan BJ, Wang YA, Coppieters S, Zebger-Gong H, Weispfenning A, Seidel H, Ploeger BA, Mueller U, Oliveira CSVD, Paulson AS. Regorafenib plus nivolumab in patients with mismatch repair-proficient/microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal cancer: a single-arm, open-label, multicentre phase 2 study. Eclinicalmedicine. 2023;58: 101917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong J, Liu Y, Fu Q, Huang D, Gong W, Zou J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of regorafenib versus other third-line treatments for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2024;16:593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al Baghdadi T, Garrett-Mayer E, Halabi S, Mangat PK, Rich P, Ahn ER, Chai S, Rygiel AL, Osayameh O, Antonelli KR, Islam S, Bruinooge SS, Schilsky RL. Sunitinib in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with FLT-3 amplification: results from the targeted agent and profiling utilization registry (TAPUR) study. Target Oncol. 2020;15(6):743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carrato A, Swieboda-Sadlej A, Staszewska-Skurczynska M, Lim R, Roman L, Shparyk Y, Bondarenko I, Jonker DJ, Sun Y, De la Cruz JA, Williams JA, Korytowsky B, Christensen JG, Lin X, Tursi JM, Lechuga MJ, Van Cutsem E. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus either sunitinib or placebo in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiegelberg D, Mortensen ACL, Palupi KD, Micke P, Wong J, Vojtesek B, Lane DP, Nestor M. The novel anti-cMet antibody seeMet 12 potentiates sorafenib therapy and radiotherapy in a colorectal cancer model. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rovithi M, Gerritse SL, Honeywell RJ, Ten Tije AJ, Ruijter R, Peters GJ, Voortman J, Labots M, Verheul HMW. Phase I dose-escalation study of once weekly or once every two weeks administration of high-dose sunitinib in patients with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(5):411–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tomida C, Yamagishi N, Nagano H, Uchida T, Ohno A, Hirasaka K, Nikawa T, Teshima-Kondo S. Antiangiogenic agent sunitinib induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and accelerates motility of colorectal cancer cells. J Med Investig. 2017;64(3.4):250–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All research data in this paper are available on requestion.