Abstract

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality in men, with a high propensity for bone metastasis that significantly impairs patient quality of life. The Wnt5a signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the progression and metastasis of PCa. Wnt5a can act as both an oncogene and a tumor suppressor, highlighting its complex and context-dependent functions. In PCa, Wnt5a promotes tumor progression through mechanisms such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and interaction with androgen receptor (AR) signaling. Conversely, Wnt5a can induce dormancy in bone-metastatic PCa cells via the ROR2/SIAH2 axis, inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Understanding the dual roles of Wnt5a in PCa and bone metastasis is crucial for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of disease progression and identifying potential therapeutic targets. This review focuses on the current understanding of Wnt5a's role in PCa and bone metastasis, emphasizing its significance in tumor biology and clinical management.

Keywords: Bone metastasis, Molecular mechanism, Prostate cancer, Signaling, Wnt5a

Introduction

The prostate, a male accessory reproductive organ located beneath the bladder, plays a key role in reproductive physiology by contributing to seminal fluid and maintaining sperm viability. This gland exhibits both endocrine and exocrine functions.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most prevalent malignancies in men, ranking as the second most commonly diagnosed male cancer globally [1]. Its high incidence and associated mortality rates make it a significant public health concern. Over 95% of PCa cases are adenocarcinomas, predominantly originating from acinar carcinoma, with a smaller proportion arising from ductal carcinoma. Approximately 80% of prostate adenocarcinomas develop from the peripheral zone of the gland, involving lumen or basal epithelial cells, which constitute 70% of the prostate tissue.

PCa is characterized by considerable heterogeneity, leading to variations in incidence, prognosis, and mortality. Individuals with PCa who have acinar carcinoma generally have a more favorable prognosis compared to those with ductal carcinoma. Notably, around 80% of PCa cases are diagnosed at a localized stage, and with early diagnosis, the 10-year survival rate for localized PCa is 99% [2].

In recent years, factors such as population aging, shifts in dietary patterns, and the increased implementation of prostate-specific antigen screening have contributed to a significant rise in the incidence and mortality of PCa. [3] In its untreated state, PCa relies on androgen receptor (AR) signaling for growth and survival, which forms the foundation for androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, despite the initial effectiveness of ADT, PCa may recur and progress to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

CRPC, particularly metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), represents one of the most significant causes of cancer-related mortality among men. [4] This advanced stage of the disease is challenging to manage due to its inherent or acquired resistance to therapeutic agents. Resistance to current therapies remains inevitable, posing significant challenges in the clinical management of mCRPC, while a range of treatment options are available [5].

PCa exhibits a unique propensity for bone metastasis, with over 80% of advanced cases developing skeletal lesions that significantly compromise patient survival and quality of life [1]. Wnt5a—a key non-canonical Wnt ligand—emerges as a critical mediator of tumor-bone crosstalk, exhibiting context-dependent roles in both promoting and suppressing metastatic progression. Preclinical studies highlight Wnt5a's dual functionality [6]. Clinically, elevated Wnt5a in circulating tumor cells (CTCs) correlates with resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors, while its loss in bone metastatic niches predicts shorter bone metastasis-free survival [6].

Based on the aforementioned findings, bone metastases are a key prognostic factor for individuals with PCa, particularly in advanced stages of the disease. PCa exhibits a strong propensity for bone metastasis, with imaging studies revealing bone involvement in approximately 70% to 90% of individuals with CRPC [7]. The skeleton is the most common site for secondary PCa, and the development of bone metastases is associated with debilitating symptoms such as impaired mobility, chronic pain, and a significant reduction in patient survival rates [8].

Along with severely impacting the prognosis and life expectancy of patients, bone metastases are the leading cause of mortality for them, while there are no effective treatments available yet [9].

The significance of WNT5a in WNT/β-catenin signaling

Wnt5a, a non-canonical Wnt ligand, plays a context-dependent role in modulating both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways. To clarify its mechanistic involvement, this section was divided into two parts based on the signaling mode.

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling

The β-catenin-dependent pathway, commonly referred to as the canonical Wnt pathway, is the most extensively studied branch of Wnt signaling. It regulates diverse physiological processes, including tissue homeostasis, cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration [10–13]. Dysregulation of this pathway contributes to tumor progression by enhancing the proliferation and self-renewal of cancer stem cells [14].

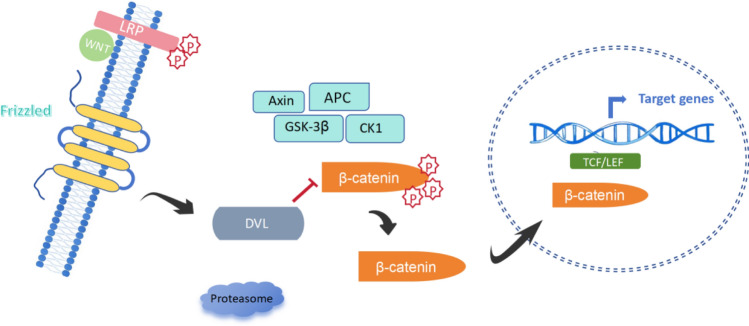

In the absence of Wnt ligands, β-catenin is phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and casein kinase 1 (CK1), targeting it for proteasomal degradation. Upon binding of canonical ligands (e.g., Wnt3a) to Frizzled (FZD) receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, this degradation is inhibited. Stabilized β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm, translocates to the nucleus, and interacts with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate gene expression programs associated with proliferation and survival [15–17] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the Wnt signaling pathways. The Wnt signaling network consists of canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) pathways, including the planar cell polarity (PCP) and Wnt/Ca2⁺ pathways. Canonical Wnt signaling is activated when Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled (FZD) receptors and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6), leading to β-catenin stabilization and nuclear translocation. In contrast, non-canonical Wnt pathways operate independently of β-catenin. The PCP pathway regulates cytoskeletal dynamics and cell polarity, while the Wnt/Ca2⁺ pathway modulates intracellular calcium signaling through phospholipase C (PLC) activation. Wnt5a, a key non-canonical Wnt ligand, plays a crucial role in mediating these pathways, particularly in cancer progression and metastasis

Although Wnt5a is primarily considered a non-canonical ligand, it can suppress the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway under specific conditions. Notably, in the bone microenvironment, Wnt5a secreted by osteoblasts activates the ROR2/SIAH2 axis, leading to β-catenin degradation. This signaling cascade induces and maintains prostate cancer (PCa) cell dormancy in bone by antagonizing the canonical pathway [6]. These findings indicate a tumor-suppressive role for Wnt5a via inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the context of bone metastasis.

Non-canonical Wnt signaling

Non-canonical Wnt pathways function independently of β-catenin and include the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway and the Wnt/Ca2⁺ pathway. These pathways are activated when non-canonical ligands such as Wnt5a bind to FZD receptors together with co-receptors including ROR2, RYK, or PTK7. The downstream effects include activation of JNK and calcium-mediated signaling cascades, leading to changes in cell polarity, migration, and cytoskeletal organization [13, 18–20].

Wnt5a is a prototypical non-canonical ligand and mediates multiple biological effects through this route. It regulates PCP, cytoskeletal remodeling, and convergent extension, and interacts with receptors such as FZD, ROR1/ROR2, and RYK to recruit and activate proteins including DVL and CK1, enabling downstream signaling [10, 21, 22]. In PCa, Wnt5a activates non-canonical signaling primarily through FZD2 and ROR2. Binding of Wnt5a to FZD2 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), enhancing the invasive and metastatic potential of tumor cells [23, 24]. EMT increases the migratory and invasive potential of epithelial-derived tumor cells, enabling their dissemination to target tissues and organs [25]. Additionally, Wnt5a promotes AR-driven tumor growth under specific pathological conditions in the prostate [26].

This process is mediated through MAPK/ERK and Ca2⁺-dependent pathways and is linked to castration resistance via upregulation of CCL2 and recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages [27]. These findings demonstrate that Wnt5a promotes tumor progression via non-canonical signaling mechanisms in primary and castration-resistant PCa. Simultaneously, in the bone microenvironment, Wnt5a serves a tumor-suppressive function by inhibiting canonical Wnt signaling. This dual role emphasizes the importance of context in determining the biological outcome of Wnt5a signaling.

Relationship between Wnt5a expression and PCa

Wnt5a is a key non-canonical Wnt ligand that regulates cell migration and invasion in prostate cancer (PCa). Its activity is primarily mediated through receptors such as FZD2 and ROR2. Immunohistochemistry studies have revealed that Wnt5a expression is low in benign prostatic hyperplasia but elevated in malignant tissues, indicating its involvement in PCa progression [26].

Although androgen signaling plays a well-established role in PCa, the precise interaction between androgen receptor (AR) function and Wnt signaling remains under investigation. A mouse model expressing the AR T877A mutation showed enhanced tumorigenesis and identified Wnt5a as an AR-driven tumor-promoting factor [26].

The role of Wnt5a in castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) has also been examined. Wnt5a has been shown to promote castration resistance by inducing CCL2 expression and recruiting tumor-associated macrophages via the MAPK/ERK pathway [27]. Although Wnt5a often promotes PCa progression, some studies report tumor-suppressive effects. Specifically, overexpression of Wnt5a in early-stage PCa can induce apoptosis, reduce cell proliferation, and suppress tumor growth in both primary and bone environments [28].

Wnt5a expression is notably elevated in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues, although its role as a protective factor appears to vary across different tumor types [29]. Wnt5a’s function appears to be context-dependent, acting either as an oncogene or tumor suppressor depending on expression levels and microenvironmental cues. For example, in bone, Wnt5a secreted by osteoblasts can induce PCa cell dormancy by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway through the ROR2/SIAH2 axis [6]. These findings suggest that Wnt5a may serve as a dual regulator of PCa progression, with its role determined by the local signaling context.

Effect of Wnt5a on bone metastases

Bone is one of the primary sites for PCa metastases and represents the leading cause of PCa-related mortality. Currently, there is no curative treatment for PCa with bone metastases, and the prognosis remains poor, with a five-year survival rate of less than 5% for patients presenting with bone metastases [30]. Clinically, PCa bone metastases are associated with debilitating symptoms, including spinal nerve compression, severe pain due to nerve involvement, pathological fractures, hypercalcemia, and advanced-stage manifestations such as osteolytic or osteogenic changes at metastatic sites [31].

The development of PCa bone metastases generally occurs in three key steps: (1) cancer cell invasion and circulation, (2) interactions between cancer cells and osteocytes, and (3) migration and colonization within the bone microenvironment. A recent study has outlined the underlying mechanisms of these processes, highlighting three major components: EMT and tumor invasion; PCa/Osteocyte interactions; Effects of Wnt and Ras signaling on PCa bone metastases [32].

When bone metastases occur, tumor cells originating from primary tumors form CTCs. These CTCs travel through the circulatory system and colonize bone tissue, transitioning into disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) [33]. Bone marrow metastases account for approximately 72.8% of all bone metastases, making the bone marrow the most common site of PCa metastases [34]. Within the bone marrow microenvironment, resident cells—particularly OBs and osteoclasts (OCs)—play a key role in inducing DTC dormancy through their interactions.

PCa bone metastases can be categorized as OB-dominated bone metastases or OC-dominated bone metastases based on the involvement of bone cells [35]. Current research primarily focuses on OB-driven metastases. Wnt5a secreted by OBs activates the ROR2/SIAH2 signaling axis, leading to the induction of dormancy in bone-metastatic PCa cells. This process suppresses the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, keeping metastatic cells in a dormant state. When Wnt5a expression is silenced, the dormant state is reversed, and the growth of PCa cells is restored [6]. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The role of Wnt5a in prostate cancer bone metastasis. Wnt5a secreted by osteoblasts (OBs) in the bone microenvironment induces dormancy in disseminated prostate cancer (PCa) cells through the ROR2/SIAH2 signaling axis, leading to the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This dormancy state is reversible, as the loss of Wnt5a expression results in the reactivation and proliferation of metastatic PCa cells. Additionally, Wnt5a modulates osteoclast (OC) differentiation via the ROR2 pathway, contributing to bone remodeling. These findings highlight the dual role of Wnt5a in regulating both tumor dormancy and bone homeostasis

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regulates multiple biological processes associated with bone metastases. Signals from the bone microenvironment guide PCa cells to metastatic sites, where they are maintained in a dormant state. Eventually, these cells become reactivated, leading to the formation of metastatic tumors [36].

The Wnt signaling pathways play a key role in OB differentiation, as well as in bone development, homeostasis, and remodeling. Wnt5a, has a dual role in modulating classical Wnt pathways within bone tissue, either enhancing or inhibiting their activity. It stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of OBs and OCs, thereby promoting bone growth and remodeling [37].

One study demonstrated that activation of the Wnt pathway reduces the degradation of β-catenin, allowing β-catenin to accumulate in the cytoplasm. The accumulated β-catenin subsequently translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to TCF/LEF, promoting the transcription of target genes and inducing bone formation [6].

Among Wnt inhibitors, Dickkopf (DKK) proteins are particularly associated with the progression and bone metastasis of PCa. The expression of DKK is dynamic and varies with the stage of PCa. In the early stages, elevated DKK expression promotes tumorigenesis and osteolytic changes. DKK competes with Wnt signaling proteins for binding to LRP5/6, thereby inhibiting the nuclear translocation of β-catenin and blocking the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to regulate the expression of downstream genes, including osteoprotegerin (OPG). OPG is a downstream target of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and a soluble decoy receptor secreted by osteoblasts that competes with the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK) for binding to its ligand, RANKL, thereby inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and activity. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin-mediated OPG expression indirectly promotes osteoclast differentiation and activity, ultimately leading to osteolytic lesions [38]. Conversely, in the late stages, decreased DKK expression enhances the expression of the downstream gene Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, promoting osteoblast differentiation and increasing bone formation, ultimately leading to osteoblastic lesions and promoting osteoblastic bone metastasis in PCa [39]. This is attributed to the decreased expression of DKK in the Wnt pathway [40].

As indicated in a study conducted by Maeda et al., Wnt5a is highly expressed in mouse skull cells but exhibits low expression in bone marrow macrophages. OB lineage cells enhance the differentiation of OC precursors via ROR2 signaling, indicating that Wnt5a secreted by OBs serves as a potent stimulus for OC generation. This underscores the dual role of Wnt5a in both tumor progression and the regulation of bone homeostasis. Notably, changes in Wnt5a expression are influenced by cancer cells, particularly at metastatic sites, where it impacts the rate of bone remodeling. [41]

Additionally, Wnt5a secreted by marrow stromal cells (MSCs) enhances the migratory capacity of PCa cells, directing their migration toward MSCs. At bone metastasis sites, Wnt5a is highly expressed in PCa cells, indicating a chemotactic effect that facilitates bone metastases. Furthermore, Wnt5a induces and activates bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) expression, particularly BMP-4 and BMP-6, promoting osteoblastic lesions associated with PCa [42].

As a factor derived from MSCs, Wnt5a induces BMP-6 expression in PCa cells via the non-classical Wnt5a pathway, even in the absence of androgens. Bone stromal cell-derived Wnt5a similarly induces BMP-6 expression through the same pathway [43]. The role of BMPs in bone metastases has been well-documented. BMP-6 enhances the invasive capacity of PCa cells in vitro, while BMP-mediated tumors facilitate bone invasion by modulating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), immune cell signaling, or inflammatory cytokines [44, 45].

Wnt5a exhibits different effects on the biological behavior of different tumor cell types, including proliferation, migration, and invasion. These differences are attributed to the distinct expression profiles of Wnt5a receptors and their downstream signaling pathways. Some studies demonstrated an anti-tumor effect of Wnt5a. Specifically, Wnt5a overexpression inhibits PCa cell proliferation and reduces tumor growth within the bone microenvironment. Through the Wnt5a/ROR2 signaling pathway, Wnt5a can prevent the establishment of bone lesions in in vivo models [46].

A study investigating the role of Wnt5a in reducing tumor growth within the bone microenvironment further supports these findings. Thiele conducted an experiment by injecting normal PC3-Luc cells and WNT5A-overexpressing PC3-Luc cells into the hearts of NSG mice. Bone metastases and associated bone injuries were observed in 80% of the mice injected with normal PC3-Luc cells, as confirmed by X-ray imaging. In contrast, mice injected with WNT5A-overexpressing cells indicated no evidence of bone injuries [46]. These results confirm that Wnt5a protects bone tissue in vivo in individuals with PCa.

In another study, Ren et al. examined the effect of Wnt5a on PCa bone metastases in vivo by inoculating PC-3 cells into the left ventricle of mice and monitoring the development of bone metastatic tumors [31]. The findings revealed that mice inoculated with Wnt5a-treated PC-3 cells exhibited fewer bone metastasis sites, smaller osteolytic areas, and longer BMFS compared to the control group.

Further experiments demonstrated that mice continuously treated with Wnt5a maintained these protective effects, while discontinuation of Wnt5a treatment resulted in increased bone metastases, larger osteolytic injury areas, and shorter BMFS. These results indicate that Wnt5a effectively inhibits bone metastases and osteolytic bone destruction caused by PCa cells in vivo. Importantly, the study indicates that the inhibition of bone metastases by Wnt5a is reversible.

Potential of Wnt5a as a therapeutic target

Treatment options for advanced PCa remain limited, posing a significant challenge in clinical management [47]. Androgens, particularly dihydrotestosterone (DHT), are crucial for the growth and maintenance of prostate tumor cells [48]. DHT binds to AR on prostate tumor cells, promoting tumor progression. Consequently, therapies targeting the androgen receptor signaling pathway represent a cornerstone of PCa treatment. Two primary types of androgen receptor signaling inhibitors include androgen synthesis inhibitors, such as abiraterone, and androgen receptor antagonists, such as enzalutamide [49].

Abiraterone selectively inhibits androgen synthesis by targeting 17α-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase. Beyond suppressing androgen production in the testes, abiraterone inhibits androgen synthesis in the adrenal glands, prostate tumor tissues, and other sites, making it an effective systemic therapy.

Enzalutamide, a second-generation AR antagonist, acts at multiple levels of the AR signaling pathway. It specifically blocks the binding of androgens to the AR, preventing AR translocation to the nucleus, inhibiting AR binding to DNA, and disrupting the recruitment of cofactors necessary for transcriptional activation. These mechanisms effectively suppress the expression of androgen-responsive genes [50].

ADT remains the standard treatment for recurrent and metastatic prostate cancer. However, many patients progress to CRPC due to the development of resistance, which limits the effectiveness of anti-androgen drugs such as enzalutamide and abiraterone. Wnt5a plays a key role in promoting resistance to these therapies, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear. Studies have indicated that Wnt5a levels increase in PCa that has progressed to CRPC and exhibits resistance to enzalutamide or abiraterone [51]. Furthermore, Wnt5a is highly enriched in CTCs of drug-resistant individuals with PCa, where it co-regulates the trans-activation function of mutant ARs in an autocrine manner, thereby promoting tumor cell proliferation.

The reprogramming of classical AR signaling and the emergence of AR splice variants have been implicated in resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone. Following resistance, patients often exhibit a complex genomic landscape that is independent of androgens or AR signaling, rendering AR-targeted therapies ineffective [52]. Wnt5a holds considerable potential as a therapeutic target. Wnt5a can influence the progression of prostate cancer through multiple mechanisms, including EMT and modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, targeting Wnt5a not only inhibits tumor cell proliferation but also improves therapeutic outcomes by regulating the invasive and metastatic capabilities of tumor cells. Studies have shown that Wnt5a functions via the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway in CRPC, promoting tumor cell drug resistance. Targeting Wnt5a can inhibit the activation of this signaling pathway, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to therapeutic agents and overcoming drug resistance. Moreover, Wnt5a-targeted therapy can be combined with androgen receptor antagonists to simultaneously block both the Wnt signaling pathway and the androgen signaling pathway, thus exerting more effective pharmacological actions [53]. Yamamoto et al. demonstrated that overexpression of Wnt5a in enzalutamide-resistant LNCaP cells diminished the antiproliferative effects of anti-androgen drugs, while inhibiting Wnt5a restored drug sensitivity [54]. Similarly, Ning et al. found that the non-classical Wnt pathway, mediated by Wnt5a and its receptor FZD2 was enriched in enzalutamide-resistant PCa C4-2B MDVR cells and in advanced PCa. This pathway acted as a key driver of resistance to anti-androgen therapy independently of AR activation.

Blocking Wnt5a/FZD2 signaling reduces the activation of non-classical Wnt pathways, inhibits constitutively active ARs and AR variants, and suppresses tumor growth. In vivo studies further demonstrated that inhibiting Wnt5a expression significantly enhanced the efficacy of enzalutamide, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting Wnt5a signaling to overcome resistance [55]. These findings position Wnt5a as a master regulator of therapeutic resistance in PCa. Its unique ability to simultaneously modulate AR plasticity, metastatic potential, and immunosuppressive niches provides a multifaceted therapeutic avenue-a critical advance beyond sequential AR pathway inhibition. Strategies used in current clinical and preclinical study for inhibiting WNT5a signaling was shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strategies used in current clinical and preclinical study for inhibiting WNT5a signaling

| Drug name (research phase) | References | Drug type | Indication | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOXY-5 (phase I) | [56] | WNT5A mimetic peptide | Metastatic prostate cancer | Mimics the function of WNT5A, targets the WNT5A signaling pathway, triggers cytosolic free calcium signaling, reduces metastasis and dissemination of WNT5A low-expressing prostate cancer cells, and inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion |

| OMP-18R5 (phase I) | [57] | Monoclonal antibody | Prostate cancer and other solid tumors | Targets Frizzled receptors, blocks the WNT signaling pathway, and inhibits the activity of WNT ligands |

| ETC-159 (phase I) | [58] | Small molecule porcupine inhibitor | Prostate cancer and other advanced solid tumors | Inhibits the activity of Porcupine enzyme, prevents the palmitoylation and secretion of Wnt proteins, thereby inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway |

| ICG-001/PRI-724 (preclinical) | [59] | Small molecule inhibitor | Prostate cancer and other solid tumors | Inhibits the binding of β-catenin to CREB-binding protein (CBP), blocks the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway |

Conclusion and prospects

In conclusion, the incidence of PCa has been increasing over the past decade, with persistent tumor proliferation and advanced bone metastases emerging as the leading causes of PCa-related mortality. In the context of PCa and bone metastases, Wnt5a exhibits complex and multifaceted roles in tumor initiation, progression, and metastatic processes. Although significant progress has been made in understanding the expression and functional implications of Wnt5a in PCa and its bone metastases, numerous controversies and unresolved questions remain.

As a therapeutic target for cancer, Wnt5a has demonstrated certain efficacy in the treatment of various malignancies, including lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and gastric cancer. However, its clinical application in PCa remains limited. Currently, ICG-001 and PRI-724 are in the preclinical trial stage. Although they have shown some therapeutic potential, their application in prostate cancer is still in its infancy. FOXY-5, OMP-18R5, and ETC-159 have been evaluated in Phase I clinical trials for their potential use in prostate cancer and have demonstrated certain safety profiles. However, the long-term efficacy and potential adverse effects of these agents in the treatment of prostate cancer still require further investigation.

Further research into the mechanisms underlying the role of Wnt5a in PCa and bone metastases is essential for a deeper understanding of tumor biology and progression. Advances in molecular biology and omics technologies—such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—offer promising opportunities to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of Wnt5a signaling pathways in PCa and bone metastases. These insights may pave the way for identifying Wnt5a signaling as a novel avenue for research into tumor cell metabolism and its regulation, and as a potential therapeutic target for managing PCa and its associated bone metastases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Wnt

Wingless

- Wnt5a

Wnt family member 5a

- Pca

Prostate cancer

- PSA

Prostate specific antigen

- AR

Androgen receptor

- ADT

Androgen deprivation therapy

- CRPC

Castration-resistant prostate cancer

- mCRPC

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

- CRD

Cysteine residue

- β-catenin

Beta-catenin

- PCP

Planar cell polarity

- FZD

Frizzled

- LRP

LDL receptor-related protein

- Ror

Receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor

- DVL

Dishevelled

- Axin

Axin

- APC

Adenomatous polyposis coii

- GSK-3β

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- CK-1

Casein kinase 1

- TCF

T cell factors

- LEF

Lymphoid enhancing factor

- DKK1

Dickkopf1

- PTK7

Protein tyrosine kinase 7

- Ryk

Receptor-like tyrosine kinase

- JNK

C-Jun N-terminal kinase

- CAMKII

Calcium/calmodulin-de protein kinase II

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PLC

Phospholipase C

- PIP2

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- IP3

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- Rho GTP

Rho GTPases

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- CE

Convergent extension

- MTOC

Microtubule organizing center

- Dvl

Dishevelled

- Thr

Threonine

- Ala

Alanine

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- CCL2

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2

- OB

Osteoblast

- SIAH2

Seven in absentia homolog 2

- CTC

Circulating tumor cells

- DTC

Disseminated tumor cells

- BMMs

Bone marrow-derived macrophages

- BMP

Bone morphogenetic proteins

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- DHT

Dihydrotestosterone

- ARSI

Androgen receptor signaling inhibitor

- CYP17A1

Cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1

- OPG

Osteoprotegerin

- RANK

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

- RANKL

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- RUNX2

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- CBP

CREB-binding protein

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Qian-Yu Xie, Qing-De Wa Acquisition of data: Qian-Yu Xie, Guang-Quan Zhao Analysis and interpretation of the data: Qian-Yu Xie, Hao Tang Statistical analysis: Qian-Yu Xie, Guang-Quan Zhao, Hao Tang Obtaining financing: Qing-De Wa Writing of the manuscript: Qian-Yu Xie Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Qian-Yu Xie, Guang-Quan Zhao, Hao Tang. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding

This study was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82160577); The Zunyi City Science & Technology Innovation Talent Project (No. [2024] 04).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Qing-De Wa, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical registration number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Banerjee P, Kapse P, Siddique S, et al. Therapeutic implications of cancer stem cells in prostate cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2023;20(6):401–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wasim S, Lee SY, Kim J. Complexities of prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Hu JH, Shi MF, et al. Research progress on biomarkers of prostate cancer. Lab Med. 2023;38(2):190–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang F, Xu D, Wang S, et al. Chromatin profiles classify castration-resistant prostate cancers suggesting therapeutic targets. Science. 2022;376(6596):eabe1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai M, Song XL, Li XA, et al. Current therapy and drug resistance in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2023;68: 100962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren D, Dai Y, Yang Q, et al. Wnt5a induces and maintains prostate cancer cells dormancy in bone. J Exp Med. 2019;216(2):428–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomsen MK, Busk M. Pre-clinical models to study human prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(17):4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Archer Goode E, Wang N, Munkley J. Prostate cancer bone metastases biology and clinical management (review). Oncol Lett. 2023;25(4):163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye X, Huang X, Fu X, et al. Myeloid-like tumor hybrid cells in bone marrow promote progression of prostate cancer bone metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarabia-Sánchez MA, Robles-Flores M. WNT signaling in stem cells: a look into the non-canonical pathway. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(1):52–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Yu X. Crosstalk between Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and DNA damage response in cancer: a new direction for overcoming therapy resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1230822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah R, Amador C, Chun ST, et al. Non-canonical Wnt signaling in the eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023;95: 101149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin K, Yu M, Fan J, et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling: multilayered mediators, signaling mechanisms and major signaling crosstalk. Genes Dis. 2023;11(1):103–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Wang X. Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf L, Boutros M. The role of Evi/Wntless in exporting Wnt proteins. Development. 2023;150(3):201352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao Q, Chen Z, Jin X, et al. The many postures of noncanonical Wnt signaling in development and diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;93:359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurice MM, Angers S. Mechanistic insights into Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2025. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Rim EY, Clevers H, Nusse R. The Wnt pathway: from signaling mechanisms to synthetic modulators. Annu Rev Biochem. 2022;91:571–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun J, Hansen S, Morris O, et al. Senescent cells perturb intestinal stem cell differentiation through Ptk7 induced noncanonical Wnt and YAP signaling. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanderVorst K, Dreyer CA, Hatakeyama J, et al. Vangl-dependent Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling mediates collective breast carcinoma motility and distant metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2023;25(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bueno MLP, Saad STO, Roversi FM. WNT5A in tumor development and progression: a comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155: 113599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tufail M, Wu C. WNT5A: a double-edged sword in colorectal cancer progression. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2023;792: 108465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi S, Takada I. Recent advances in prostate cancer: WNT signaling, chromatin regulation, and transcriptional coregulators. Asian J Androl. 2023;25(2):158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandsmark E, Hansen AF, Selnæs KM, et al. A novel non-canonical Wnt signature for prostate cancer aggressiveness. Oncotarget. 2017;8(6):9572–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang YC, Zhang YT, Wang Y, et al. What role does PDL1 play in EMT changes in tumors and fibrosis? Front Immunol. 2023;14:1226038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi S, Watanabe T, Okada M, et al. Noncanonical Wnt signaling mediates androgen-dependent tumor growth in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(12):4938–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee GT, Kwon SJ, Kim J, et al. WNT5A induces castration-resistant prostate cancer via CCL2 and tumour-infiltrating macrophages. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(5):670–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pashirzad M, Sathyapalan T, Sahebkar A. Clinical Importance of Wnt5a in the Pathogenesis of Colorectal Cancer. J Oncol. 2021;2021:3136508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen P. Study on the expression patterns of WNT signaling pathway in different tumors and exploration of tumor markers. Sichuan: University of Electronic Science and Technology of China; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kähkönen TE, Halleen JM, MacRitchie G, et al. Insights into immuno-oncology drug development landscape with focus on bone metastasis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1121878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prigol AN, Rode MP, da Luz EF, et al. The bone microenvironment soil in prostate cancer metastasis: an miRNA approach. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(16):4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berish RB, Ali AN, Telmer PG, et al. Translational models of prostate cancer bone metastasis. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(7):403–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai R, Liu M, Xiang X, et al. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts: an important switch of tumour cell dormancy during bone metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Oronzo S, Coleman R, Brown J, et al. Metastatic bone disease: pathogenesis and therapeutic options: Up-date on bone metastasis management. J Bone Oncol. 2018;15:004–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan Z, Zielske SP, Ibrahim KG, et al. Wnt and β-catenin signaling in the bone metastasis of prostate cancer. Life (Basel). 2021;11(10):1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlashi R, Zhang X, Wu M, et al. Wnt signaling: essential roles in osteoblast differentiation, bone metabolism and therapeutic implications for bone and skeletal disorders. Genes Dis. 2022;10(4):1291–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall CL, Daignault SD, Shah RB, et al. Dickkopf-1 expression increases early in prostate cancer development and decreases during progression from primary tumor to metastasis. Prostate. 2008;68(13):1396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thudi NK, Martin CK, Murahari S, et al. Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) stimulated prostate cancer growth and metastasis and inhibited bone formation in osteoblastic bone metastases. Prostate. 2011;71(6):615–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maroni P, Bendinelli P. Bone, a secondary growth site of breast and prostate carcinomas: role of osteocytes. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Udagawa N, et al. Wnt5a-Ror2 signaling between osteoblast-lineage cells and osteoclast precursors enhances osteoclastogenesis. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai J, Hall CL, Escara-Wilke J, et al. Prostate cancer induces bone metastasis through Wnt-induced bone morphogenetic protein-dependent and independent mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2008;68(14):5785–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee GT, Kang DI, Ha YS, et al. Prostate cancer bone metastases acquire resistance to androgen deprivation via WNT5A-mediated BMP-6 induction. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(6):1634–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai J, Keller J, Zhang J, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-6 promotes osteoblastic prostate cancer bone metastases through a dual mechanism. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8274–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zabkiewicz C, Resaul J, Hargest R, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins, breast cancer, and bone metastases: striking the right balance. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(10):R349–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiele S, Göbel A, Rachner TD, et al. WNT5A has anti-prostate cancer effects in vitro and reduces tumor growth in the skeleton in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(3):471–80. 10.1002/jbmr.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng K, Hai Y, Xi Y, et al. Integrative multi-omics analysis unveils stemness-associated molecular subtypes in prostate cancer and pan-cancer: prognostic and therapeutic significance. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michaud JE, Billups KL, Partin AW. Testosterone and prostate cancer: an evidence-based review of pathogenesis and oncologic risk. Ther Adv Urol. 2015;7(6):378–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacob A, Raj R, Allison DB, et al. Androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer and therapeutic strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(21):5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elshazly AM, Gewirtz DA. Making the case for autophagy inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in combination with androgen-targeted therapies in prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(20):5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Dehm SM, Hillman DW, et al. A prospective genome-wide study of prostate cancer metastases reveals association of wnt pathway activation and increased cell cycle proliferation with primary resistance to abiraterone acetate-prednisone. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):352–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson PA, Arora VK, Sawyers CL. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(12):701–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Y, Xu W, Xiao YT, et al. Targeting signaling pathways in prostate cancer: mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto H, Oue N, Sato A, et al. Wnt5a signaling is involved in the aggressiveness of prostate cancer and expression of metalloproteinase. Oncogene. 2010;29(14):2036–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ning S, Liu C, Lou W, et al. Bioengineered BERA-Wnt5a siRNA targeting wnt5a/fzd2 signaling suppresses advanced prostate cancer tumor growth and enhances enzalutamide treatment. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21(10):1594–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehdawi LM, Prasad CP, Ehrnström R, et al. Non-canonical WNT5A signaling up-regulates the expression of the tumor suppressor 15-PGDH and induces differentiation of colon cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 2016;10(9):1415–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith DC, Rosen LS, Rashmi C, et al. First-in-human evaluation of the human monoclonal antibody vantictumab (OMP-18R5; anti-Frizzled) targeting the WNT pathway in a phase I study for patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15):2540–2540.23733781 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu C, Takada K, Zhu D. Targeting Wnt/β-catenin pathway for drug therapy. Med Drug Discov. 2020;8:100066. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krishnamurthy N, Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treatm Rev. 2018;62:50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Qing-De Wa, upon reasonable request.