Abstract

The current study investigated how students at King Saud University’s College of Pharmacy perceive the effectiveness of the Academic Advising Unit and their experiences with academic advisors. Our study examined responses gathered from 164 participants, including 97 female and 67 male students, representing various academic years (2nd to 6th). The survey assessed several key aspects, including the availability of advisors, their knowledge and expertise, communication effectiveness, level of support and encouragement, ability to assist with goal setting, integration of feedback, accessibility of resources, and overall student satisfaction. The results of our study revealed that while the majority of students in the College of Pharmacy expressed satisfaction with and support for academic advising, a notable proportion of students exhibited ambivalence or dissatisfaction with the advising services. Regarding advisor availability, 57% of students expressed satisfaction, while 32% were indifferent, reflecting unmet needs. Similarly, in terms of communication, 62% were satisfied, but 28% were neutral, again suggesting an inconsistency in advisor responses. A similar trend was observed concerning advisor knowledge and expertise, with 58% satisfied and 31% neutral. Specifically, when questioned about guidance on research and extracurricular activities, only 48% expressed satisfaction. Overall, 61% felt that communication was beneficial in resolving their issues. Students were below-average in their satisfaction with the support provided during challenging times. Findings suggest that an average level of academic advising functioning and emphasized the need for more individualized and consistent academic advising to better meet student expectations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s44446-025-00015-5.

Keywords: Academic advising, Academic engagement, Advisor effectiveness, Feedback integration, Flexibility, Student satisfaction

Introduction

An academic advisor plays several roles, including nurturing the advisor-advisee relationship, ensuring their participation, and addressing students’ needs holistically (Liua and Ammiganb 2024; Bilquise et al. 2024). Maintaining a strong advisor-student rapport enhances students'confidence in their abilities. A sense of belonging is equally vital for academic success—students who feel disconnected from campus struggle to focus, often experiencing isolation and diminished motivation. Conversely, a strong sense of belonging boosts confidence, engagement, and academic enthusiasm. This is particularly true for international students, who frequently face discrimination and feelings of alienation (Yuan et al. 2023). The success of academic advising unit services depends on how well they are integrated into the academic environment and whether the staff are given the freedom and support to work directly. Better support from the university could help advisors, students, and teachers work together more effectively (Ashton-Hay and Chanock 2023). In a study of 396 students, reviews on the qualities of academic advisors—such as their availability, motivation, encouragement, care, and accessibility—have shown a positive impact on students. Interestingly, it has been observed that younger advisors often receive higher ratings and more positive feedback from students, indicating that age might play a role in how students perceive advisors (Iatrellis et al. 2024). However, no significant difference is noted based on advisor gender. Ultimately, what matters most is how supportive and approachable advisors are, regardless of their age or gender (Iatrellis et al. 2024).

Challenges faced by students

From stepping into higher education, students start facing challenges with the first being the fear of choosing the right course. After enrollment, other challenges such as advisor clarity, knowledge, availability, technical issues, resource accessibility, communication, and financial support. Figure 1 explains the dimensions of the academic advisor–student relationship, where the challenges faced by students develop expectations from both the academic advising unit and advisors to meet their needs and resolve issues. When students’ expectations are fulfilled, it highlights the influence of academic advising on students and describes the important roles that good advisors play in student academic success.

Fig. 1.

The figure illustrates the dimensions of the advisor-advisee relationship, where students face several challenges and develop expectations from their academic advisors. When students receive support, it shows several outcomes of academic advising

Choosing the right course

Students often get confused while choosing the right course for themselves. For instance, a student wanting to pursue a career in pharmacy might struggle to decide which specialization within pharmacy—such as clinical pharmacy, community pharmacy, or pharmaceutical sciences—will be the best fit for their future. Making a wrong decision in choosing a course might leave a student frustrated and lead them to quit. Therefore, students must receive the necessary guidance to keep their inquisitive minds engaged and interested (Khalil and Williamson 2014). The role of an academic advisor is vital in assisting students in making these crucial choices about their higher studies. This role is just as important as that of a parent or professor. These choices can have an impact on a student’s future career aspirations and, for some students, throughout their lives (Khalil and Williamson 2014).

Communication

Another challenge faced by students is establishing communication with their advisors. Academic advisors are expected to create an environment where students can easily communicate the issues that concern them because they serve as the “students’ first communication interface” with the education system (Maddineshat et al. 2019). Findings from research indicated that the academic advisors’ nonverbal communication abilities are mediocre, which negatively impacts students’ satisfaction with the academic advising experience (Maddineshat et al. 2019).

Clarity

Many academic advising programs often lack clear missions and goals as a result, these programs become ineffective and misaligned with educational needs (Akosah 2024). There should be a well-defined purpose statement to guide and evaluate an effective academic advising program. Without it, academic advisors may have varying ideas about what advising should entail, leading to inconsistencies in their practices and the quality of advising provided to students. When advisors’ philosophies and practices do not match, students may experience varying levels of support and guidance, affecting their overall advising experiences (Akosah 2024).

Advisor accessibility and availability

A study on students at the University of Cape Coast asserts that their advisors are overwhelmed with teaching and other responsibilities, and lack sufficient office space, making their availability difficult for advising (Bilquise et al. 2024). In addition, the high workload and large number of students per advisor contribute to the challenges students face with academic advising (Akosah 2024).They are often burdened with an increased student count (Selim et al. 2023). Another study recommends, hiring more advisors (Akosah 2024), investing in advisor training (Selim et al. 2023), improving infrastructure and resources, developing better communication, promoting diversity among staff, and ensuring stable advisor relationships.

Technology

Excessive use of technology can be overwhelming and stressful, especially when everything is conducted online. Students believe that academic advisors can make a difference by helping them navigate it without becoming overwhelmed. A thoughtful approach to using technology can help students find balance and support instead of feeling overwhelmed (Liua and Ammiganb 2024).

Equality and equity of university resources

Academic support resources are crucial for improving the college journey of students. When these resources are designed with equity in mind, they can help in addressing disparities faced by students from underserved communities. (Nguyen et al. 2024) surveyed 524 students and found that regardless of their generation, advisors, course staff, and peers are the most helpful resources. Providing a secure space to nurture students helps them develop socio-emotional skills, concluded by equity-oriented practices. However, first-generation students face barriers such as lack of awareness, access to these practices, and lack of time. Upon employing such practices, supervisors can reduce barriers to equity for students significantly enhancing their progress toward both personal and professional goals (Nguyen et al. 2024).

Financial and personal issues

Students often face challenges related to financial and technology-related issues decreasing their motivation and advisors should be aware of these. Colleges too need to recognize these support and needs. Focusing on the positive aspects of technology could increase the engagement of students. These purposeful needs fulfillment could drive a strong sense of belonging for students enhancing advisor-advisee relations and the overall advising experience (Liua and Ammiganb 2024; Lester and Perini 2010). A study reported that students took the initiative to use technology to create supportive online communities, fostering relationships and mentorship, especially during the pandemic when access to advising was limited (Sobaih et al. 2020).

Student feedback

Nothing can replace academic advisors and in reality, empathetic, responsive, and knowledgeable advisors matter most to students (Bilquise et al. 2024). Students also hold high expectations for their advisors, to guide them toward important academic milestones. Unmet expectations may lead to student frustration, lowering advisor ratings. Therefore, continuous advisor training is necessary as it helps them meet student needs. Advisors need to understand and manage student expectations before offering guidance. If advisors clarify what their roles truly demand, they can prevent misunderstandings, reduce disappointments, and address concerns effectively (Iatrellis et al. 2024).

Mental health issues

Many nursing students in Egypt and Saudi Arabia report experiencing stress leading to anxiety, insomnia, and even depression (Selim et al. 2023). Here, academic advisors can play an important role in helping students manage stress by not only providing guidance but also connecting them to mental health resources, such as psychiatrists when needed. To address these issues, the Student Academic Advising and Counseling Survey (SAACS) tool was developed to measure academic advising and counseling services for students. It was noted that the tool appears helpful in bringing improvements to services, especially when paired with student interviews and feedback (Selim et al. 2023).

Personal characteristics

Students’ grades are affected by personal characteristics (socio-economic status, gender, and age), course difficulties, teaching methods, and personal issues. It was emphasized that these factors affect academic performance. This makes it essential to consider these influences when predicting grades. Educators should recognize these influences and provide the necessary support to help students succeed academically (Atalla et al. 2023).

Advisor overplaying advisory

Advisors can offer help by providing practical resources such as funding, access to documents and literature, equipment, and connections to useful networks (Blanchard and Haccoun 2020). Most advisors advise to help students avoid mistakes, but some take it too far by micromanaging their students and trying to control every detail to prevent errors. This approach is generally unhelpful and leads to negative feelings. Students under such advisors are more likely to consider dropping out. While support is imperative, how it is given makes a difference (Blanchard and Haccoun 2020).

Cultural differences

Some international students do not seek help from support services due to a lack of awareness, highlighting the need for universities to ensure that international students know what is available on campus. They often face cultural, language, and background discrimination (Yuan et al. 2023). Academic advisors are encouraged to become acquainted with their cultural backgrounds to help reduce the struggles these students face in adapting to a new environment. Removing these barriers could improve their confidence and retention (Yuan et al. 2023).

Student expectations

Having An advisor who is genuinely committed to students'personal and academic development can cultivate a sense of support and recognition, enhancing their overall educational experience. When advisors take the time to truly listen and connect with students, it makes a big difference (Liua and Ammiganb 2024; Bilquise et al. 2024). In addition to care, when advisors take the time to greet students warmly, shake hands, and engage in casual conversation while in their office, it helps students feel more at ease. This suggests that both verbal and non-verbal behaviors from advisors can make a big difference. Students feel more comfortable and open when advisors smile, nod, maintain good eye contact, and avoid distractions like turning off their cell phones (Akosah 2024).

Students appreciate when advisors use technology thoughtfully, not just to communicate but also to make their interactions more meaningful and accessible. Knowing that their advisor is there to help navigate challenges with empathy and authenticity makes students feel more confident and valued in their academic journey. This indicates that higher education should be more human-centered (Liua and Ammiganb 2024; Bilquise et al. 2024). During the COVID- 19 pandemic, students in higher education faced challenges due to limited access to advising; however, it is evident that the pandemic highlighted the crucial role of academic advisors in maintaining students’ engagement and learning through technology (Bilquise et al. 2024). Many studies have debated whether remote advising can replace in-person meetings. Some students feel that personal relationships made face-to-face—such as reading body language and picking up on subtle cues in facial expressions and tone of voice—are lost in online settings (Liua and Ammiganb 2024). This is particularly challenging when they are dealing with complex issues such as course planning or career decisions, leading many students to demand in-person interactions. However, others believe that if advisors communicate clearly and set expectations, students can still build strong relationships and receive the necessary support even in a virtual setting (Liua and Ammiganb 2024).

Based on the aforementioned challenges, students also expect their academic advisor to be available, help them manage stress, provide clarity and transparency, demonstrate sensitivity towards diverse cultural backgrounds, and offer relevant information about advising procedures, careers, and resources. These expectations are represented in Fig. 1, which explains how expectations develop from challenges and how meeting them reflects effective advising impact. Conversely, we can say that students’ expectations have become challenges and goals for advisors to fulfill in order to ensure their effective role.

Academic advising unit, college of pharmacy, king saud university

The Academic Advising Unit (AAU) is an integral part of the College of Pharmacy’s Academic Affairs Agency. The mission of AAU is to address the diverse challenges faced by students by leveraging the expertise of academic advisors and social and psychological specialists. Our goal is to help students develop into well-rounded individuals who are academically, socially, and psychologically resilient. Furthermore, the unit focuses on fostering skill development, nurturing excellence and creativity, and ensuring the well-being of students. It is committed to continuously enhancing the quality of its services. Our aim is to provide confidential support and guidance, and our guiding principles are centered on problem-solving, overcoming obstacles, and delivering counseling services in line with international standards.

The present study will provide a better understanding of students’ perceptions regarding academic advising and, more importantly, clarify the different dimensions of challenges, expectations, and academic advising outcomes in the advisor-advisee relationship. This will highlight areas in need of improvement in the College of Pharmacy, King Saud University. Given that the effectiveness of academic advising remains a critical area of evaluation, this study explores students'perceptions of academic advising, assessing key aspects such as advisor availability, communication, expertise, and overall satisfaction. By identifying challenges and areas for improvement, the findings aim to enhance the academic advising experience and better meet student expectations.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study obtained ethical approval from the King Saud University Institutional Review Board (IRB) under reference number KSU-HE- 24–157. All procedures followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was received from every participant. Our aim was to understand student perceptions. Therefore, a total of 164 students who have been allotted academic advisors were, participated in the survey conducted at the College of Pharmacy, King Saud University. Participants belonged to different academic years, ranging from 2nd year to 6th year. It is important to note that first-year students were not included in this survey, as they are part of the"Common First Year Deanship,"an independent university entity. These students are not yet affiliated with the College of Pharmacy, as they are completing foundational courses and competing for entry into various healthcare colleges based on their performance.

To maintain privacy, the identity of every respondent was kept confidential while capturing their perceptions. Each respondent was referred to as “anonymous” to protect the involved participants’ identities. The majority of students (67) were in their 3rd year, followed by 35 students in the 5th year, 30 students in the 4th year, 20 students in the 2nd and the fewest students (12) in the 6th year. Among those participants, 97 were female and 67 were male students.

Survey

Study design

To evaluate the relationship between students and academic advisors including, their effectiveness and the support offered from the students’ perspectives. The study was conducted in the English language through the distribution of a survey to students. This survey took nearly a month, initiated on February 17, 2024, and completed by March 19, 2024. In total, 22 questions were asked to gather feedback from students regarding their experiences with academic advising. The feedback aimed to improve AAU activities. The survey was conducted in person in an offline mode. The questions belonged to eight different categories:

Availability

Knowledge and expertise

Communication

Support and encouragement

Effectiveness in goal setting

Feedback integration

Accessibility of resources

Overall satisfaction

Data collection

The data for this study were collected through a structured survey questionnaire. Participants were asked to indicate their level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The survey responses were recorded in the first six categories as “extremely satisfied,” “satisfied,” “neutral,” “dissatisfied,” and “extremely dissatisfied”. The final category of questions, “overall satisfaction,” was evaluated on a scale ranging from high satisfaction to high dissatisfaction, scored from 5 to 1.

Data analysis

The recorded data were quantified and expressed as percentages for each question asked. This analysis allowed us to understand the distribution of opinions among the various statements presented to the participants. The analysis was based on the percentage distribution of responses: “strongly satisfied = 5,” “satisfied = 4,” “neutral = 3,” “dissatisfied = 2” and “strongly dissatisfied = 1.” To assess the association between student gender, academic year, and satisfaction with academic advisors, a Chi-square test of independence was conducted using Microsoft® Excel. Data were collected via a survey measuring gender, academic year, and satisfaction levels on a Likert scale. Gender and academic year served as independent variables, while overall satisfaction was the dependent variable. The Chi-square test evaluated whether these demographic factors significantly influenced satisfaction. A p-values > 0.05 indicating insignificance association.

Results

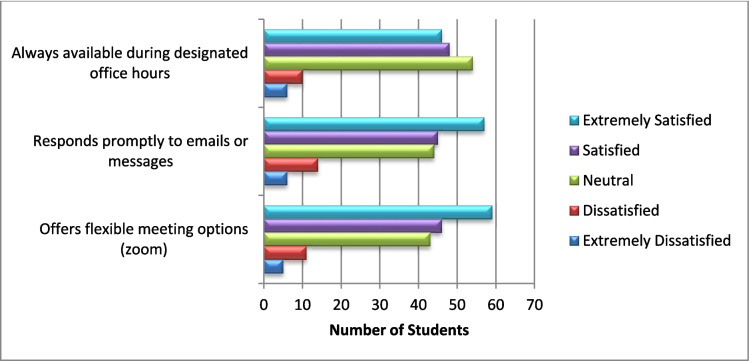

Availability

The data (Fig. 2) revealed that 28% (46) of students were extremely satisfied with the availability of academic advisors during designated office hours, while 29% (48) were satisfied, resulting in a total of 57% of students expressing satisfaction. A significant percentage (32%), or 54 students, were neutral, neither happy nor negative, suggesting room for improvement. However, 6% (10) were dissatisfied and 4% (6) were extremely dissatisfied, indicating that the designated hours may be insufficient or that other factors are affecting availability for students.

Fig. 2.

The graph shows the plotted response rate (in numbers) of student’s level of satisfaction with academic advisors’ availability and accessibility

When asked about advisors’ responsiveness, 35% (57) were extremely satisfied and 27% (45) were satisfied, resulting in 62% of students feeling that their communication needs were met promptly. Meanwhile, 28% (44) were neutral, 9% (14) were dissatisfied, and only 4% (6) were extremely dissatisfied, highlighting delays in responses to emails or messages from advisors. Regarding the flexibility offered by the AAU for meeting options such as Zoom meetings, 37% (59) were extremely satisfied, and 29% (46) reported satisfaction. Neutral responses accounted for 26% (43) of students; however, 6% (11) were dissatisfied and 3% (5) were extremely dissatisfied, pointing to the need for academic advisors to adapt and show flexibility regarding meeting options (Fig. 2).

-

2.

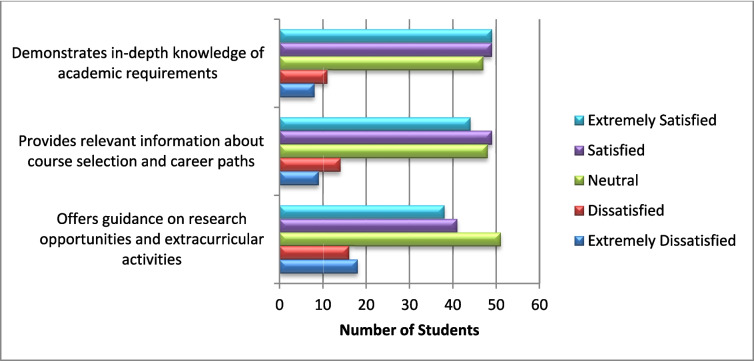

Knowledge and expertise

Figure 3 presents a bar graph based on the data collected regarding the knowledge and expertise of academic advisors, revealing varied levels of satisfaction. In demonstrating in-depth knowledge of academic requirements, 29% (49) of students were extremely satisfied, and another 29% (49) were satisfied. Additionally, 28% (47) were neutral, 6% (11) were dissatisfied, and 5% (8) were extremely dissatisfied, reflecting some gaps in fully meeting students’ expectations and failing to demonstrate comprehensive knowledge. Nevertheless, a total of 58% of students expressed confidence in the academic advisors’ expertise.

Fig. 3.

The graph shows the plotted response rate (in numbers) of students level of satisfaction with academic advisors’ knowledge and expertise

When asked whether academic advisors provided relevant information about course selection and career guidance, 26% of students (44) showed extreme satisfaction, and 29% (49) were satisfied. Another 29% (48) were neutral, while 8% (14) were dissatisfied, and 5% (9) were extremely dissatisfied, indicating a notable number of students felt the guidance could be improved. Students also provided feedback when asked about the guidance offered on research opportunities and extracurricular activities. Only 23% (38) were extremely satisfied, and 25% (41) responded satisfied, resulting in a comparatively low overall satisfaction rate (48%) in this area. Conversely, a significant 31% (51) were neutral, 9% (16) were dissatisfied, and 10% (18) expressed extreme dissatisfaction, indicating inadequate levels of guidance and low support for involvement in extracurricular activities (Fig. 3).

-

3.

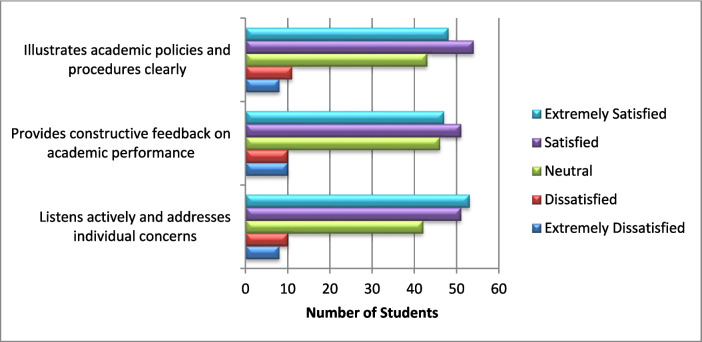

Communication

Figure 4 shows the results of the survey evaluating students’ views on their communication with academic advisors or the AAU. Regarding the clarity of academic policies and procedures, 29% (48) of students were extremely satisfied, and 33% (54) were satisfied. While 26% (43) were neutral, 6% (11) were dissatisfied, and 4% (8) expressed extreme dissatisfaction, indicating that advisors can explain academic policies and procedures in a much better way.

Fig. 4.

The graph shows the plotted response rate (in numbers) of student’s level of satisfaction with their experience communicating with advisors

Next, for providing constructive feedback on performance, 29% (47) were extremely satisfied, and 31% (51) responded satisfied, totaling 60% of students who appreciated feedback from their advisors. Meanwhile, 28% (46) were neutral, 6% (10) were dissatisfied, and the remaining 6% (10) expressed extreme dissatisfaction. The relatively low dissatisfaction compared to satisfaction suggests that advisors should provide more productive feedback, which could help students reach their academic goals. Regarding active listening and addressing individual concerns, 32% (53) were extremely satisfied, and 31% (51) were satisfied, indicating that 63% of students felt heard and supported during individual issues. However, 25% (42) still showed neutrality, 6% (10) were dissatisfied, and 4% (8) were extremely dissatisfied, indicating that more personalized help should be encouraged from academic advisors by improving communication (Fig. 4).

-

4.

Support and encouragement

Figure 5 presents the survey results regarding the level of support and encouragement students receive from their academic advisors. For encouraging goal-setting and academic achievement, 29% (47) of students were extremely satisfied, and 32% (51) were satisfied, resulting in a strong combined satisfaction of 61%. Meanwhile, 28% (46) were neutral, and the remaining 6% (10 dissatisfied and 10 extremely dissatisfied) indicated they were dissatisfied or extremely dissatisfied, revealing that some students felt they received average encouragement and that more improvement is needed.

Fig. 5.

The graph shows the plotted response rate (in numbers) of student’s level of satisfaction with the support and encouragement provided by academic advisors

Regarding the support offered during challenging periods, 26% (43) were extremely satisfied and 22% (37) were satisfied. 29% (49) remained neutral, 13% (22) were dissatisfied, and 7% (13) were extremely dissatisfied, suggesting that some students felt there was insufficient support during difficult periods. In terms of assistance provided in identifying resources for academic success, 28% (46) expressed extreme satisfaction, and 26% (44) were satisfied. However, 30% (50) gave neutral responses, while 8% (14) were dissatisfied and 6% (10) reported extreme dissatisfaction. This indicates a need for advisors to be more proactive in helping students to find academic resources (Fig. 5).

-

5.

Effectiveness in goal setting

The survey on students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of goal setting revealed that advisors are average in assisting with setting clear goals and tracking the progress of students (Fig. 6). For providing assistance in short-term and long-term academic goals, 21% (35) of students reported being extremely satisfied, and 29% (49) were satisfied, resulting in half of the students (50%) feeling positive about academic advisors’ assistance in goal setting. However, 32% (53) remained neutral, which was more than any individual percentage of satisfaction, revealing that many students neither agreed nor disagreed with the assistance provided. Additionally, 8% of students (14) showed dissatisfaction and 7% (13) reported extreme dissatisfaction.

Fig. 6.

The graph displays the plotted response data (in numbers) of students to analyze their level of satisfaction regarding academic advisors’ assistance with goal orientation

Furthermore, when it comes to helping students create plans for achieving academic and career objectives, 23% (38) of students were extremely satisfied, and 25% (42) were satisfied, making less than 50% favor academic advisors’ help in creating career and academic plans. Besides this, 29% (48) were neutral, 12% (21) were dissatisfied, and 8% (15) responded with extreme dissatisfaction, reflecting the need for academic advisors to improve their planning abilities to support students in their achievements. In monitoring progress toward set goals, 22% (37) of students expressed extreme satisfaction, and 29% (49) were just satisfied. Yet, 28% (47) of students remained neutral, 10% (16) reported dissatisfaction, and the remaining 9% (15) were extremely dissatisfied. Therefore, this reflects that the advisors’ efforts in tracking and monitoring progress were just average (Fig. 6).

-

6.

Feedback integration

The data from student responses regarding academic advisors’ feedback integration were recorded. For actively seeking and valuing students’ feedback, 25% (42) of students were extremely satisfied, and 28% (47) were satisfied. Thirty-two percent (54) of students responded neutrally, while 6% (11) were dissatisfied, and the remaining 6% (10) were extremely dissatisfied. The significant neutrality indicates that students might not have strong positive interactions with their advisors regarding feedback, while the dissatisfaction highlights a feeling of negligence in the feedback process from academic advisors, who do not sufficiently seek or value student feedback (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The graph shows the plotted response data (in numbers) of students to analyze their level of satisfaction regarding the consideration of students’ feedback by advisors

Regarding adapting advising strategies based on student input, 24% (40) said they were extremely satisfied, and 31% (51) were satisfied, pointing to a total of 55% of students who believed that advisors accept feedback regarding advising strategies and integrate it into their advising. Thirty-one percent (51) were neutral, 6% (11) were dissatisfied, and another 6% (10) were extremely dissatisfied. Finally, when asked about the encouragement given by advisors to students to reflect on and implement advice, 28% (47) were extremely satisfied, and 27% (45) were satisfied. Thirty-one percent (52) remained neutral, 6% (10) were dissatisfied, and another 6% (10) were extremely dissatisfied. These results suggest that most students were content, but there was still a significant percentage of disappointment toward academic advisors for not encouraging students to reflect on and take action on their feedback. This indicates a passive advising experience from students’ perspectives (Fig. 7).

-

7.

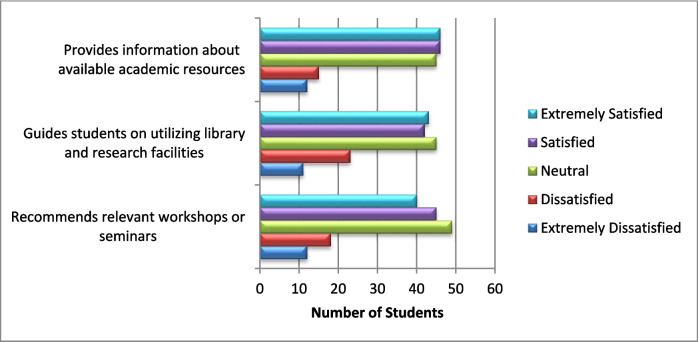

Accessibility of resources

The survey aimed to gather student opinions regarding the accessibility of resources provided by academic advisors and the AAU. In providing information about available academic resources, 28% (46) were extremely satisfied, and another 28% (46) were satisfied, showing an overall satisfaction rate of 58%. From the remaining students, 27% (45) were neutral, 9% (15) were dissatisfied, and 7% (12) were extremely dissatisfied, implying that there could be improvements in the way information about academic resources is communicated (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

The graph shows the plotted response data (in numbers) of students to evaluate the accessibility of university resources

Regarding guidance on utilizing library and research facilities, 27% (43) were extremely satisfied, 26% (42) were satisfied, and 27% (45) provided neutral responses. However, 14% (23) were dissatisfied, and the remaining 6% (11) expressed extreme dissatisfaction, revealing a lack of guidance on critical aspects of the academic journey, such as the effective use of libraries and research facilities. Furthermore, students were asked whether the advisors recommended relevant workshops and seminars to help in their academic journey. In response, 24% (40) showed extreme satisfaction, and 27% (45) were satisfied. Meanwhile, 28% (49) were neutral, 11% (18) were dissatisfied, and 7% (12) were extremely dissatisfied. These results suggest that more specific workshops and seminars should be recommended, because several students found the recommendations lacking or not beneficial (Fig. 8).

-

8.

Overall satisfaction

When students were asked to rate their overall satisfaction on a scale from 5 to 1, categorized as “extreme satisfaction = 5”, “satisfaction = 4”, “neutral = 3”, “dissatisfaction = 2”, and “extreme dissatisfaction = 1”, we observed a 50–50 trend. In total, 50% of students were satisfied (45 extremely satisfied and 36 satisfied), while the remaining 50% included neutrality (46) and dissatisfaction (22 dissatisfied and 14 extremely dissatisfied). In the latter group, 28% were neutral, and 22% of students expressed dissatisfaction with the AAU and academic advisors. This rating clearly indicates that, although students were happy and satisfied with the current approach of the AAU and advisors, they expected significant improvements and upgrades in all aspects of the AAU functioning (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

The bar graph shows the level of students’ overall satisfaction with the AAU

The analysis of potential associations between demographic and academic variables with overall student satisfaction specifically examined whether gender and academic year influenced satisfaction ratings with the academic advisors. Statistical analysis revealed no significant association between gender and overall satisfaction (p = 0.6508), indicating that male and female students reported similar satisfaction levels. Similarly, no significant relationship was found between academic year and overall satisfaction (p = 0.2024), suggesting consistent satisfaction levels across different student academic years.

Discussion

Enhancing advisor availability and communication

The findings indicate that designated advising hours are often insufficient, impacting accessibility for students. While 57% of students expressed satisfaction, a significant 32% remained indifferent, and 11% were dissatisfied. Academic advising is a demanding role, requiring advisors to balance availability while managing workloads (Khalil and Williamson 2014). Although technological solutions, such as email and virtual meetings, offer flexible communication (Vaikunthanathan 2019; Tippetts et al. 2024), our study found that 62% of students felt their communication needs were met, while 28% were neutral and 15% reported delays in response. This suggests a need for more structured and efficient communication strategies.

The pandemic demonstrated the effectiveness of online platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams in academic advising (Argüello 2020; Torka 2021). In our study, 66% of students acknowledged the flexibility offered by such tools, though 26% expected further improvements. These findings highlight the importance of refining digital advising strategies to accommodate student expectations and ensure timely, effective interactions.

Student success through knowledge sharing and career guidance

Despite the role of advisors in shaping academic journeys, some students perceive gaps in knowledge and guidance. While 58% of students were satisfied with advisors'academic expertise, 28% were neutral, and 11% dissatisfied, indicating a need for enhanced advisor training (Iatrellis et al. 2024). Similarly, only 55% of students found advisors helpful in career planning, with 29% neutral and 13% dissatisfied. Given that students often lack the maturity to make informed academic choices (Grewal and Kaur 2016), institutions should invest in structured career counseling services, possibly integrating AI-based systems to personalize course recommendations. Guidance on extracurricular and research opportunities was notably lacking, with only 48% expressing satisfaction and 19% dissatisfied. Studies suggest that participation in extracurricular activities enhances student success (Damminger and Rakes 2017; Suvedi et al. 2015). The findings highlight an urgent need for advisors to take a proactive role in encouraging students to engage in research and networking opportunities, which can significantly impact career prospects.

Refining academic feedback and personalized support

Effective feedback is central to student growth, yet results indicate room for improvement. While 60% of students valued the feedback provided by advisors, 28% remained neutral, and 12% were dissatisfied, suggesting that feedback could be more constructive and individualized. Feedback plays a critical role in shaping student persistence and self-awareness (Owens 2015). Studies emphasize the importance of advisors reflecting on their own practices to enhance the quality of guidance offered (Cuseo 2003).

Advisors also play a crucial role in students'personal well-being. In our study, 63% of students felt supported in personal matters, but 10% expressed dissatisfaction, signaling that more empathetic advising practices are needed. Students often hesitate to discuss personal issues (Khalil and Williamson 2014), highlighting the necessity for advisors to foster an open, welcoming environment. Encouraging training programs in active listening and mentorship could enhance student-advisor relationships.

Strengthening academic and career planning

Students reported only moderate support in academic planning, with 50% satisfied, 32% neutral, and 15% dissatisfied. The role of advisors extends beyond classroom guidance to shaping students'long-term academic and career trajectories (Burt et al. 2013). Our findings suggest that advisors need to refine their planning skills and adopt a more individualized approach.

Similarly, goal-setting support was underwhelming, with only 48% satisfaction. Advisors play a critical role in motivating students to engage in skill-building activities and develop self-regulation strategies (Henning 2007). Institutions should focus on professional development programs for advisors, emphasizing goal-setting methodologies and personalized career roadmaps.

Improving resource awareness and utilization

A significant portion of students expressed dissatisfaction with the availability and awareness of academic resources. While 58% reported that advisors provided adequate information, 27% were neutral and 15% disappointed. Effective resource utilization is vital for student success, yet many institutions prioritize moderately performing students due to resource constraints, potentially leaving others underserved.

Guidance on using academic facilities, such as libraries and research resources, was also lacking, with only 53% of students satisfied. Academic advisors play a critical role in familiarizing students with institutional resources (Grites 1979). Implementing targeted workshops and seminars could bridge this gap, as suggested in previous research (Pasquini and Steele 2013).

Integrating student feedback for continuous improvement

Student perceptions suggest a passive advising process, with only 53% believing advisors actively sought and valued their feedback. While 55% were satisfied with advisors'openness to feedback, a significant portion remained neutral or dissatisfied. This highlights a crucial need for an interactive, student-centered advising approach. Advisor self-assessment and feedback mechanisms are essential for continuous improvement and enhancing the overall advising experience (Carlstrom 2005).

Finally, when specifically asked in the survey to rate their overall satisfaction, only 50% of students were satisfied with the AAU and academic advisors. The survey made it clear that students from the Pharmacy College at King Saud University hold high hopes for the AAU services and demand enhancements and upgrades in various aspects of academic advising. Considering all categories together, an average of nearly 55% of students clearly favored the academic advisors’ approach to supporting students, while the rest of the students’ responses were distributed among those who were doubtful, lacked confidence in advisors, or felt indifferent or dissatisfied with their academic advising experience. The data highlighted areas in which students are struggling and hoping for their unmet needs to be fulfilled. These areas need more focus, such as guidance on research opportunities, extracurricular activities, support during challenging periods, and planning to achieve academic and career objectives. Furthermore, helping students optimize academic goals, track progress, value student feedback, adapt advising strategies based on student input, encourage students to reflect on and implement advice, and recommend relevant workshops or seminars are areas of advising that require further improvement.

Conclusions

The findings highlight significant gaps in academic advising, particularly in availability, responsiveness, career guidance, resource accessibility, and personalized support. While a majority of students appreciate their advisors'efforts, a substantial proportion remains neutral or dissatisfied, indicating a pressing need for improvements in advising strategies. These concerns suggest that traditional advising approaches may not fully align with the evolving expectations of students, who increasingly seek more flexible, responsive, and tailored support systems. To address these challenges, universities should implement structured feedback mechanisms that allow students to voice their concerns and actively participate in shaping advising services. A proactive advising model—one that anticipates student needs rather than merely responding to inquiries- can ensure more consistent and meaningful engagement. Additionally, integrating enhanced career guidance frameworks, including AI-driven course recommendations and industry mentorship programs, can help students make more informed academic and professional decisions. Improving advisor accessibility remains a critical priority. Extending office hours, adopting hybrid advising models that combine in-person and virtual interactions, and utilizing digital tools such as automated scheduling and real-time messaging can facilitate more efficient communication. Moreover, establishing tailored mentorship programs that connect students with experienced faculty members or alumni can enhance career planning, research engagement, and skill development. By adopting these strategies, academic advising can evolve into a more student-centered service that fosters academic success, personal growth, and career readiness. Institutional commitment to continuous training, technology integration, and resource optimization will be essential in bridging existing gaps and ensuring that all students receive the guidance and support they need to thrive.

Although the study included 164 participants, the sample was limited to students from the College of Pharmacy at King Saud University, which may not fully represent the diverse needs and experiences of students across other disciplines or universities. These limitations suggest that future research should consider a more diverse sample, utilize longitudinal approaches, and incorporate qualitative data to further explore the complexities of academic advising.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z.A., R.A., and J.F.A.; methodology, A.Z.A., J.F.A., R.A., and K.A.; formal analysis, M.A. and A.Z.A.; writing original, J.F.A., R.A., A.Z.A., M.A., and L.A.; writing review, A.R.A, L.A. and A.K.A.; software, A.K.A. and L.A.; data curation, N.M.A, A.A, A.K.A.; validation, A.Z.A and K.A.; investigation, K.A. resources, R.A. and J.F.A.; visualization of data W.M.B, N.M.A, A.A, M.B.J,S.A, and M.S; funding acquisition and project administration, A.Z.A.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R563) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this study.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study obtained ethical approval from the King Saud University Institutional Review Board (IRB) under reference number KSU-HE- 24–157. All procedures followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was received from every participant and the corresponding author holds the signed consent forms.

Publication consent

Authors secured explicit consent for publication from the participants cited in the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Jawza F. Alsabhan, Rana Aljadeed and Ahmed Z. Alanazi these authors contributed equally to this work and share frst authorship.

References

- Akosah JC (2024) Perceptions of effectiveness of academic advising: case of Ghanaian university students. Res Human Soc Sci 14(3):Article 3. 10.7176/RHSS/14-3-03

- Argüello G (2020) Virtual academic advising in challenging times. In The impact of COVID-19 on the international education system (pp 184–196). 10.51432/978-1-8381524-0-6_14

- Ashton-Hay SA, Chanock K (2023) How managers influence learning advisers’ communications with lecturers and students. J Acad Lang Learn 17(1):40–68 [Google Scholar]

- Atalla S, Daradkeh M, Gawanmeh A, Khalil H, Mansoor W, Miniaoui S, Himeur Y (2023) An intelligent recommendation system for automating academic advising based on curriculum analysis and performance modeling. Mathematics 11(5):1098 [Google Scholar]

- Bilquise G, Ibrahim S, Salhieh SEM (2024) Investigating student acceptance of an academic advising chatbot in higher education institutions. Educ Inf Technol 29(5):6357–6382 [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard C, Haccoun RR (2020) Investigating the impact of advisor support on the perceptions of graduate students. Teach High Educ 25(8):1010–1027 [Google Scholar]

- Burt TD, Young-Jones AD, Yadon CA, Carr MT (2013) The advisor and instructor as a dynamic duo: academic motivation and basic psychological needs. NACADA J 33(2):44–54 [Google Scholar]

- Carlstrom AH (2005) Preparing for multicultural advising relationships. Acad Advising Today 28(4):1 [Google Scholar]

- Cuseo J (2003) Academic advisement and student retention: empirical connections and systemic interventions. National Academic Advising Association. https://www.shawnee.edu/sites/default/files/2019-01/Academic-advisementv-and-student-retention.pdf

- Damminger J, Rakes M (2017) The role of the academic advisor in the first year. In: Fox JR and Martins HE (eds) Academic advising and the first college year (pp 21–64). University of South Carolina, National Resource Center for The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition and NACADA: The Global Community for Academic Advising

- Grewal D, Kaur K (2016) Developing an intelligent recommendation system for course selection by students for graduate courses. Bus Econ J 7(2)

- Grites TJ (1979) Academic advising: getting us through the eighties. AAHEERIC/Higher Education Research Reports, No. 7, 1979

- Henning MA (2007) Students' motivation to learn, academic achievement, and academic advising (Doctoral dissertation, AUT University, New Zealand). https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/c641eb84-afbc-40b7-aa47-d07d7dbc2a4e/content

- Iatrellis O, Samaras N, Kokkinos K, Xenakis A (2024) Elevating academic advising: natural language processing of student reviews. Appl Syst Innov 7(1):12 [Google Scholar]

- Khalil A, Williamson J (2014) Role of academic advisors in the success of engineering students. Univ J Educ Res 2(1):73–79 [Google Scholar]

- Lester J, Perini M (2010) Potential of social networking sites for distance education student engagement. New Dir Community Coll 2010(150):67–77 [Google Scholar]

- Liua C, Ammiganb R (2024) Student interaction, technological engagement, and the online community: exploring how to humanize academic advising with technology in higher education. Contemporary issues in knowledge-based economy, higher education and sustainable development, pp 139–157

- Maddineshat M, Yousefzadeh MR, Hashemi M (2019) Evaluating the academic advisors’ communication skills according to the students living in dormitory. J Educ Health Promot 8:62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J, Phuong AE, Salehi S (2024) Supporting first-generation student experiences in programs and advising: lessons from a pandemic. NACADA J 44(1):23–37 [Google Scholar]

- Owens MR (2015) Student perceptions of academic advisor effectiveness and student success: factors that matter (Master’s thesis, Eastern Illinois University). https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2361

- Pasquini LA, Steele GE (2013) Technology in academic advising: perceptions and practices in higher education. NACADA Technol Advising Comm Sponsored Surv 6(1):3–9 [Google Scholar]

- Selim A, Omar A, Awad S, Miligi E, Ayoub N (2023) Validation of student academic advising and counseling evaluation tool among undergraduate nursing students. BMC Med Educ 23(1):139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaih AEE, Hasanein AM, Abu Elnasr AE (2020) Responses to COVID-19 in higher education: social media usage for sustaining formal academic communication in developing countries. Sustainability 12(16):6520 [Google Scholar]

- Suvedi M, Ghimire RP, Millenbah KF, Shrestha K (2015) Undergraduate students’ perceptions of academic advising. NACTA J 59(3):227–233 [Google Scholar]

- Tippetts M, Davis B, Zick CD (2024) Texting as an advising communication tool: a case study of receptivity and resistance. J Coll Stud Retent: Res, Theory Pract 25(4):892–912 [Google Scholar]

- Torka M (2021) The transition from in-person to online supervision: does the interaction between doctoral advisors and candidates change? Innov Educ Teach Int 58(6):659–671 [Google Scholar]

- Vaikunthanathan S (2019) Technology and advising: a quantitative analysis of the differences between advisor and student use of technology (Master’s thesis, University of Washington Bothell). https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/44498

- Yuan X, Yang Y, McGill C (2023) The impact of academic advising activities on international students’ sense of belonging. J Int Stud 14(1):424–448 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.