Abstract

Background

Transcription factor EB (TFEB) is an endogenous protective protein. Serum TFEB levels were measured after acute intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), in addition to determining their connection to the severity and neurological outcomes of patients.

Methods

Serum TFEB levels were measured in a prospective cohort study of 186 ICH patients and 100 controls. Severity was estimated using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and hematoma volume. Poor neurological status mirrored by the post-ICH six-month modified Rankin Scale (mRS), along with stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP), was considered as the two outcome variables.

Results

Patients showed a marked decline in serum TFEB levels compared with controls. Serum TFEB levels were significantly inversely correlated with both NIHSS scores and hematoma volume; had a linear relationship with likelihoods of both SAP and poor prognosis (mRS scores 3–6), were independent of ordinal mRS scores, SAP, and poor prognosis; and were efficiently predictive of SAP and poor prognosis with analogous areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve as NIHSS scores and hematoma volume. The association between serum TFEB levels and poor prognosis is partly mediated by SAP.

Conclusion

Reduced serum TFEB levels post-ICH of evident relevance to bleeding intensity are powerfully linked to poor neurological prognosis, wherein there is a partial mediative effect by SAP, thereby reinforcing TFEB as a serological prognostic indicator of good prospect in ICH.

Keywords: transcription factor EB, intracerebral hemorrhage, outcome, severity, stroke-associated pneumonia, biomarkers

Introduction

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) stands out as a cerebrovascular accident of high incidence throughout the world, seriously threaten human life and health, and therefore has been a topic of research priorities nowadays.1 In this scenario, prompt intraparenchymal entry of bleedings following vascular rupture directly damages brain tissues, wherein a succession of cascading deleterious molecular events, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, cellular apoptosis, etc, are elicited, thereby leading to further cellular injuries.2 As for severity assessment of ICH, the one extensively accepted scaling system, that is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), along with hematoma volume, are very usually applied in clinical practice.3 The modified Rankin Scale (mRS), an outcome scoring avenue, is very frequently adopted for evaluating neurological conditions of patients subsequent to ICH.4 Patients with ICH are susceptible to stroke-associated pneumonia (SAP), thereby obviously heightening probability of poor prognosis.5 Apparently, blood biomarkers have, during recent decades, drawn extensive attention because of their aid in deepening comprehension of pathophysiological mechanisms and facilitating development of prognostic anticipation in ICH.6–8

Transcription factor EB (TFEB), a transcription factor that activates autophagy, directly modulates the expression of autophagy-associated proteins.9 TFEB is abundant in brain tissues under normal conditions.10 Expressions of TFEB were markedly diminished in brain tissues of rats subjected to subarachnoid hemorrhage.11 In addition, TFEB is significantly reduced in the brains of humans with Alzheimer’s disease, and its levels are negatively proportional to the Braak stage.12 Moreover, mounting data have shown that TFEB may protect against acute brain or spinal cord injury by inhibiting inflammation, diminishing tissue edema, and attenuating cellular apoptosis.11,13,14 Notably, serum TFEB levels were significantly reduced in patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and were inversely related to cognitive decline.15 Overall, the above evidence suggests that serum TFEB level may be a biomarker of brain injury. Additionally, TFEB expression by macrophages was increased by crystalline silica both in vivo and in vitro.16 Moreover, TFEB may potentially lessen acute lung injury by mitigating inflammation and alleviating mitochondrial damage in lung tissue and alveolar epithelial cells.17 Therefore, the serum TFEB levels may reflect the degree of lung injury. This study was designed to explore the association between serum TFEB levels and poor prognosis and SAP in humans with acute ICH, and to determine the mediation effect of SAP.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Study Setting and Ethical Statement

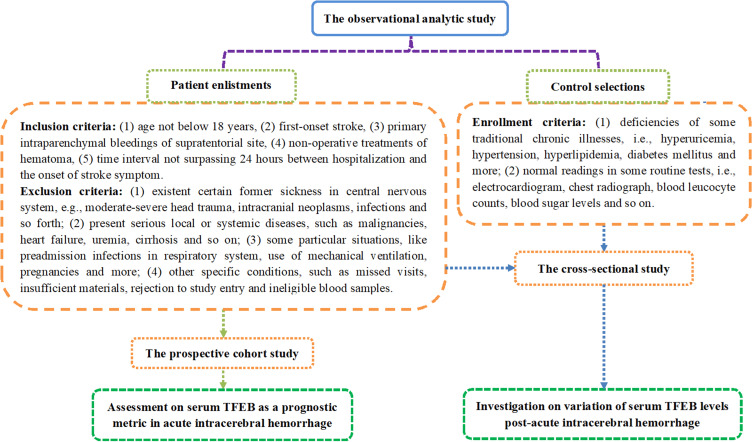

This observational analytical study was performed at the QuZhou KeCheng People’s Hospital (Quzhou, China) and Zhejiang Hospital (Hangzhou, China) between February 2020 and May 2023. In accordance with the pre-established study plan outlined in Figure 1, this study contained two parts, namely, a cross-sectional study and a prospective cohort study, as well as encompassing two groups of participants, that is, patients with ICH and controls. Patients underwent consecutive enrollment and later were strictly screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in Figure 1. Controls were derived from physical examinees, and strict selection was completed according to the eligibility requirements depicted in Figure 1. The essential objective of this study was to unveil alterations in serum TFEB levels following ICH and to unravel the predictive significance of serum TFEB on poor prognosis and SAP in patients with ICH. The current study was conducted in compliance with local and institutional tenets, along with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent updates. The study protocol was checked and later was approved by the Ethics Committee of the QuZhou KeCheng People’s Hospital (Quzhou, China) (approval number: 202501). The patients’ legal representatives or controls independently signed informed consent forms after being fully informed of the details of the study.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the study design and enrollment details in the acute intracerebral hemorrhage-related investigation. This analytic survey encompassed a cross-sectional sub-study and a prospective cohort sub-study to determine the alteration of serum-based transcription factor EB levels after acute ICH and its prognostic value separately.

Abbreviation: TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Clinical Evaluation and Data Gatherings

Some conventional parameters, such as demographics, adverse lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and specific medications, were recorded upon arrival at the hospital. Several vital signs, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature, were measured noninvasively upon entry into the emergency center. NIHSS scores were used to reflect the initial neurological deficits in patients.18 Vomiting and dysphagia were identified by swallowing tests. Radiological variables, such as hematoma sites, expansion of bleeding into the subarachnoid space, and entry of hematoma into the intraventricular cavity, were discriminated. The bleeding amount was computed using the following equation: 0.5×a×b×c.19 If patients suffered from acute lower airway infections within the initial seven days after ICH and pneumonia met the SAP diagnostic criteria as reported previously,20 SAP was considered. The mRS scores at six months after ICH were applied to assess neurological outcome conditions, with scores of 3–6 indicating a poor prognosis.21

Blood Collection, Processing and Immunological Assays

By venipuncture, blood specimens were drawn at admission of patients and study entry of controls, with rapid deposition into gel-containing polypropylene tubes of 5 mL for allowing clot formation, and a subsequent centrifugation at 2000 × g for 10 min was completed. Serum supernatants were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at − 80°C until further use. Because biomarkers may be decomposed, thereby influencing measurement results, serum samples were thawed for immune analysis within 3 months, since they were preserved under low-temperature conditions.

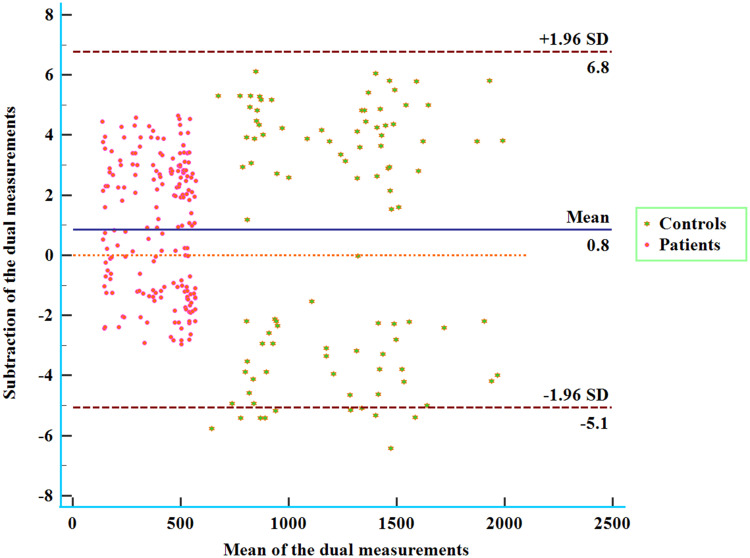

Serum TFEB levels were quantified using a commercially available Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (MyBioSource, MBS9337615). The sensitivity and detection range of this kit are 0.1 ng/mL and its detection range is from 0.25 ng/mL to 8 ng/mL. As per the manufacturer’s protocol, serum samples were analyzed in duplicate by the same proficient technician, who was blinded to the study details. Double measures in good agreement (Figure 2) were averaged for the final statistical assessment.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman graph with an exhibition of consistency in the double measurements of serum-based transcription factor EB levels among sufferers from acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Good consistency was revealed between the two quantifications of transcription factor EB levels in the serum of patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage.

Abbreviation: SD, denotes standard deviation.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS (version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables, whether nominal or ordinal, are summarized as counts (percentages). Numerical variables, whether continuous or discrete, following normality test by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, were reported as means (standard deviations, SDs) or medians (percentiles 25th-75th) as deemed applicable. Four statistical methods, that is, the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, independent-sample Student’s t-test, and Mann–Whitney U-test, were applied for data comparisons between two groups, as appropriate. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for data comparisons among multiple groups. SAP and poor six-month prognosis were selected as binary outcome variables, and mRS score was chosen as the outcome variable of the ordinal category. Independent predictors were investigated using univariate analyses to screen for significant variables of entry into the binary logistic regression model or ordinal regression model. Bivariate correlations were assessed using the Spearman’s test. By employing R 3.5.1, a statistical language environment (https://www.r-project.org), restricted cubic splines were created and mediation analysis was performed. In the context of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, discrimination efficiency was evaluated using MedCalc 20 (MedCalc Software, Ltd., Ostend, Belgium), and areas under the ROC curve (AUCs) were compared using the Z test. The ROC curves were drawn in the help of the GraphPad Prism 7.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, California, USA). A two-tailed P value < 0.05, signifies significant disparities.

Results

Study Populations

Initially, a collective number of 249 patients, who were diagnosed with acute ICH, fitted the standards proffered in Figure 1, and there was an elimination of 63 patients from this study after a subsequent screening in accordance with exclusion criteria provided in Figure 1; a final enrollment of 186 patients was finished for clinical analysis. The baseline features of all patients, such as demographic data, radiological parameters, and the prevalence of conventional comorbidities and so forth, are presented in Table 1. One hundred controls (57 being males, 37 tobacco smokers, and 34 alcohol drinkers) had a median age of 60 years (range, 43–78 years; lower-upper quartiles, 50–67 years). From a statistical perspective, patients versus controls showed no significant differences in terms of age, sex ratio, and percentage of smokers and drinkers (all P>0.05).

Table 1.

Basic Features of Patients and Factors in Association with Stroke-Associated Pneumonia and Six-month Poor Prognosis After Intracerebral Hemorrhage

| Parameters | All Patients | Poor Prognosis | P Values | Stroke-Associated Pneumonia | P Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence | Absence | Presence | Absence | ||||

| Number | 186 | 80 | 106 | 53 | 133 | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 61 (51–70) | 66 (55–72) | 59 (50–68) | 0.030 | 67 (57–73) | 59 (50–69) | 0.011 |

| Male | 104 (55.9%) | 44 (55.0%) | 60 (56.6%) | 0.827 | 30 (56.6%) | 74 (55.6%) | 0.905 |

| Vascular risk factors | |||||||

| Cigarette smoking | 65 (34.9%) | 30 (37.5%) | 35 (33.0%) | 0.526 | 22 (41.5%) | 43 (32.3%) | 0.236 |

| Alcohol drinking | 66 (35.5%) | 29 (36.3%) | 37 (34.9%) | 0.850 | 24 (45.3%) | 42 (31.6%) | 0.078 |

| Chronic diseases | |||||||

| Hypertension | 119 (64.0%) | 52 (65.0%) | 67 (63.2%) | 0.801 | 36 (67.9%) | 83 (62.4%) | 0.479 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 49 (26.3%) | 30 (37.5%) | 19 (17.9%) | 0.003 | 19 (35.8%) | 30 (22.6%) | 0.063 |

| COPD | 8 (4.3%) | 4 (5.0%) | 4 (3.8%) | 0.683 | 2 (3.8%) | 6 (4.5%) | 0.823 |

| Medications | |||||||

| Statin use | 53 (28.5%) | 19 (23.8%) | 34 (32.1%) | 0.213 | 15 (28.3%) | 38 (28.6%) | 0.971 |

| Anticoagulant use | 12 (6.5%) | 5 (6.3%) | 7 (6.6%) | 0.923 | 4 (7.5%) | 8 (6.0%) | 0.701 |

| Antiplatelet use | 22 (11.8%) | 10 (12.5%) | 12 (11.3%) | 0.805 | 8 (15.1%) | 14 (10.5%) | 0.384 |

| Time parameters | |||||||

| Admission time (h) | 7.5 (4.5–11.5) | 8.5 (4.5–11.5) | 7.5 (4.5–11.0) | 0.245 | 8.5 (4.5–11.5) | 7.5 (4.5–11.5) | 0.502 |

| Sampling time (h) | 8.7 (5.2–12.2) | 9.2 (5.7–12.7) | 8.2 (5.2–12.2) | 0.256 | 9.2 (5.7–12.2) | 8.2 (5.2–12.2) | 0.428 |

| Complications | |||||||

| Dysphasia | 46 (24.7%) | 29 (36.3%) | 17 (16.0%) | 0.002 | 19 (35.8%) | 27 (20.3%) | 0.027 |

| Vomiting | 50 (26.9%) | 30 (37.5%) | 20 (18.9%) | 0.005 | 21 (39.6%) | 29 (21.8%) | 0.013 |

| Stroke-associated pneumonia | 53 (28.5%) | 34 (42.5%) | 19 (17.9%) | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Vital signs | |||||||

| SAP (mmHg) | 136 (128–151) | 133 (126–152) | 137 (128–149) | 0.609 | 138 (128–151) | 135 (128–149) | 0.706 |

| DAP (mmHg) | 86 (82–96) | 86 (82–97) | 86 (82–95) | 0.939 | 84 (82–93) | 86 (82–96) | 0.391 |

| Radiological data | |||||||

| Superficial hematoma | 49 (26.3%) | 26 (32.5%) | 23 (21.7%) | 0.098 | 11 (20.8%) | 38 (28.6%) | 0.275 |

| IVH | 28 (15.1%) | 20 (25.0%) | 8 (7.5%) | 0.001 | 15 (28.3%) | 13 (9.8%) | 0.001 |

| SAH | 12 (6.5%) | 6 (7.5%) | 6 (5.7%) | 0.613 | 2 (3.8%) | 10 (7.5%) | 0.348 |

| Severity assessment | |||||||

| NIHSS scores | 11 (7–13) | 13 (11–5) | 8 (7–11) | <0.001 | 13 (11–15) | 9 (7–12) | <0.001 |

| Hematoma volume (mL) | 9 (7–17) | 15 (10–18) | 8 (5–11) | <0.001 | 17 (10–21) | 8 (6–14) | <0.001 |

| Biochemical indexes | |||||||

| Blood WBC counts (×109/l) | 6.3 (4.2–8.8) | 6.8 (4.1–9.2) | 5.9 (4.2–8.7) | 0.618 | 6.7 (3.9–9.0) | 6.1 (4.3–8.8) | 0.968 |

| Blood glucose levels (mmol/l) | 9.1 (7.1–12.4) | 10.0 (7.3–14.2) | 8.9 (7.1–10.8) | 0.037 | 10.8 (7.7–15.0) | 8.9 (7.0–10.8) | 0.014 |

| Serum TFEB levels (pg/mL) | 456.0 (290.2–522.5) | 313.3 (180.9–483.0) | 500.8 (395.9–538.2) | <0.001 | 291.9 (181.9–453.3) | 490.7 (372.3–529.7) | <0.001 |

Notes: Data were summarized as counts (proportions) or median (percentiles 25th −75th) as suitable As applicable, the Chi-square test or Mann–Whitney U-test was applied for comparison between two groups.

Abbreviations: NIHSS stands for National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TFEB, transcription factor EB; WBC, white blood cell; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure.

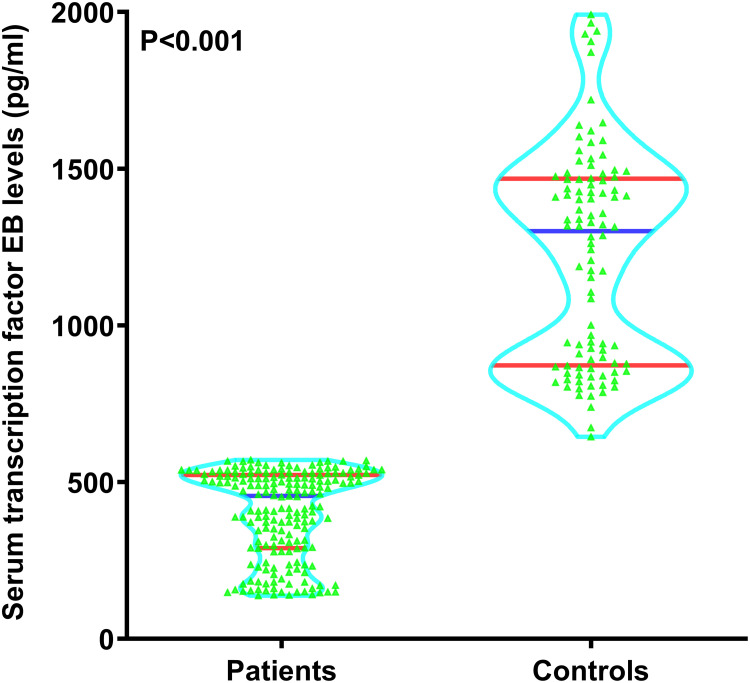

Serum TFEB Levels, Disease Severity and Six-month Neurological Outcome Subsequent to Acute ICH

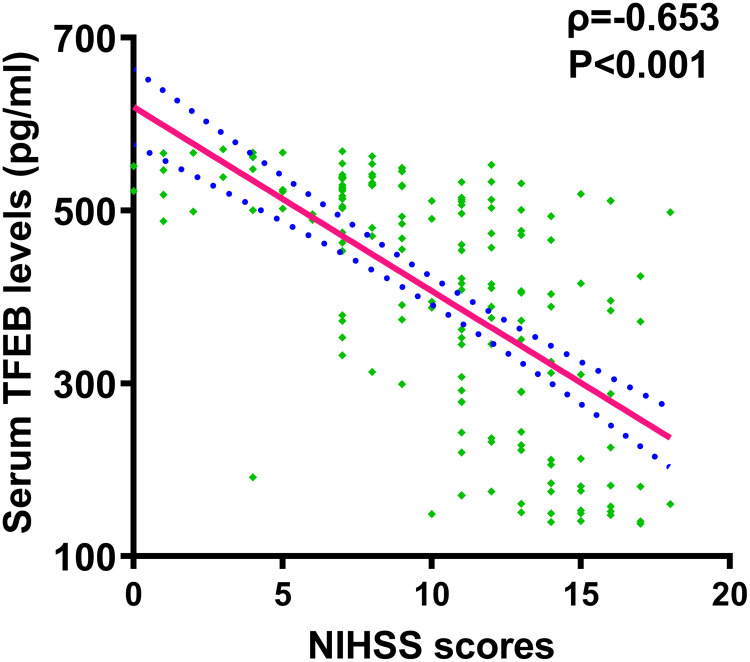

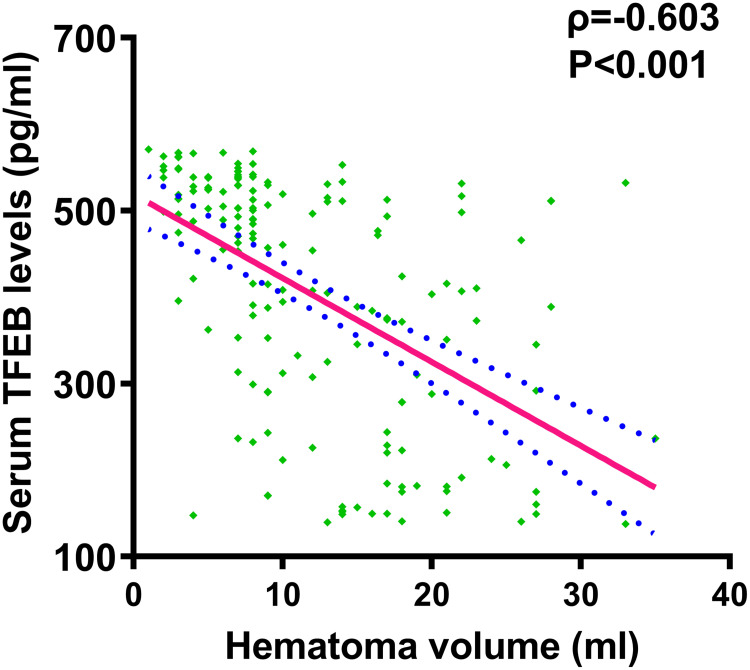

Patients had significantly lower serum TFEB levels than controls (P<0.001; Figure 3). Serum TFEB levels were inversely proportional to the NIHSS scores (P<0.001; Figure 4) and substantially decreased with increasing hematoma volume (P<0.001; Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Distinction of serum transcription factor EB levels between controls and patients following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Substantial differences were observed in serum-based transcription factor EB levels, with lower levels in individuals with acute intracerebral than in the controls (P<0.001).

Figure 4.

Serum-based transcription factor EB levels and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores among subjects diagnosed of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Using the Spearman test, serum-based transcription factor EB levels were demonstrated to be negatively proportional to the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores after acute intracerebral hemorrhage (P<0.001).

Abbreviations: NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Figure 5.

Serum-based transcription factor EB levels and hematoma size following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. By applying the Spearman test, serum-based transcription factor EB levels were confirmed to be significantly inversely associated with hematoma volume after acute ICH (P<0.001).

Abbreviation: TFEB, transcription factor EB.

The mRS was regarded as an ordinal categorical variable. The patients were divided into seven subgroups. As shown in Table 2, the factors that significantly differed among the seven subgroups were age, prevalence of diabetes mellitus, presence of vomiting, presence of dysphasia, emergence of SAP, occurrence of hemorrhagic intraventricular accumulation, NIHSS score, hematoma size, blood glucose level, and serum TFEB level (all P<0.05). These ten variables of significant distinction were all incorporated into the ordinal regression model, and accordingly, it was affirmed that serum TFEB levels [odds ratio (OR), 0.995; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.990–0.998; P=0.029], occurrence of SAP (OR, 2.951; 95% CI, 1.644–5.291; P=0.035), NIHSS score (OR, 1.242; 95% CI, 1.125–1.372; P=0.009), and hematoma volume (OR, 1.074; 95% CI, 1.028–1.120; P=0.012) were independently associated with ordinal mRS scores.

Table 2.

Factors in Relation to Ordinal Modified Rankin Scale Scores at Six months After Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage

| Parameters | Ordinal Modified Rankin Scale Scores | P Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Number | 18 | 36 | 52 | 22 | 21 | 23 | 14 | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 50 (46–61) | 64 (52–71) | 60 (52–68) | 63 (51–72) | 65 (55–74) | 59 (51–69) | 69 (72–77) | 0.025 |

| Male | 8 (44.4%) | 19 (52.8%) | 33 (63.5%) | 11 (50.0%) | 10 (47.6%) | 16 (69.6%) | 7 (50.0%) | 0.526 |

| Vascular risk factors | ||||||||

| Cigarette smoking | 4 (22.2%) | 9 (25.0%) | 22 (42.3%) | 7 (31.8%) | 7 (33.3%) | 10 (43.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.502 |

| Alcohol drinking | 4 (22.2%) | 12 (33.3%) | 21 (40.4%) | 7 (31.8%) | 8 (38.1%) | 11 (47.8%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.553 |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 13 (72.2%) | 21 (58.3%) | 33 (63.5%) | 16 (72.7%) | 13 (61.9%) | 14 (60.9%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.929 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (16.7%) | 6 (16.7%) | 10 (19.2%) | 7 (31.8%) | 6 (28.6%) | 8 (34.8%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.016 |

| COPD | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.8%) | 3 (5.8%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.713 |

| Medications | ||||||||

| Statin use | 3 (16.7%) | 12 (33.3%) | 19 (36.5%) | 9 (40.9%) | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (13.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.136 |

| Anticoagulant use | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (2.8%) | 5 (9.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (13.0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.547 |

| Antiplatelet use | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (8.3%) | 7 (13.4%) | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (9.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.665 |

| Time parameters | ||||||||

| Admission time (h) | 5.0 (4.5–7.5) | 6.5 (3.5–10.0) | 8.5 (5.5–12.3) | 9.5 (4.5–12.5) | 7.5 (6.0–9.5) | 7.5 (4.5–10.5) | 8.5 (7.5–12.5) | 0.194 |

| Sampling time (h) | 5.5 (5.2–8.2) | 7.2 (4.0–11.2) | 9.2 (6.5–13.2) | 10.2 (5.2–13.7) | 8.2 (6.2–10.2) | 8.7 (5.7–11.5) | 9.0 (8.2–13.2) | 0.110 |

| Complications | ||||||||

| Dysphasia | 3 (16.7%) | 5 (13.9%) | 9 (17.3%) | 5 (22.7%) | 7 (33.3%) | 10 (43.5%) | 7 (50.0%) | 0.025 |

| Vomiting | 2 (11.1%) | 7 (19.4%) | 11 (21.2%) | 5 (22.7%) | 8 (38.1%) | 10 (43.5%) | 7 (50.0%) | 0.048 |

| Stroke-associated pneumonia | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (5.6%) | 14 (26.9%) | 9 (40.9%) | 8 (38.1%) | 9 (39.1%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.001 |

| Vital signs | ||||||||

| SAP (mmHg) | 149 (135–170) | 139 (129–148) | 134 (125–145) | 140 (129–158) | 136 (120–147) | 131 (120–147) | 130 (128–149) | 0.421 |

| DAP (mmHg) | 94 (82–100) | 85 (84–91) | 86 (79–95) | 86 (83–97) | 83 (79–93) | 86 (78–97) | 88 (84–90) | 0.451 |

| Radiological data | ||||||||

| Superficial hematoma | 5 (27.8%) | 9 (25.0%) | 9 (17.3%) | 6 (27.3%) | 4 (19.0%) | 10 (43.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.219 |

| IVH | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (8.3%) | 4 (7.7%) | 8 (36.4%) | 3 (14.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.017 |

| SAH | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.613 |

| Severity assessment | ||||||||

| NIHSS scores | 7 (4–9) | 7 (6–9) | 11 (8–12) | 10 (8–14) | 12 (11–13) | 13 (12–16) | 15 (13–16) | <0.001 |

| Hematoma volume (mL) | 7 (3–8) | 7 (4–8) | 9 (7–17) | 10 (8–14) | 13 (9–17) | 17 (15–23) | 18 (16–21) | <0.001 |

| Biochemical indexes | ||||||||

| Blood WBC counts (×109/l) | 6.2 (4.4–7.2) | 5.3 (4.0–6.1) | 6.7 (4.6–9.3) | 5.5 (4.3–7.3) | 7.3 (4.0–9.7) | 8.5 (6.6–9.0) | 6.7 (3.3–9.4) | 0.144 |

| Blood glucose levels (mmol/l) | 9.0 (7.1–9.7) | 8.3 (6.1–10.6) | 9.0 (7.1–11.3) | 8.6 (6.9–10.8) | 10.5 (7.1–12.8) | 9.8 (7.2–12.8) | 13.4 (10.8–19.8) | 0.013 |

| Serum TFEB levels (pg/mL) | 512.7 (499.0–549.1) | 523.6 (450.8–543.5) | 458.9 (328.9–525.8) | 389.7 (307.7–519.3) | 414.9 (290.2–496.6) | 236.5 (175.0–382.4) | 178.3 (153.7–278.8) | <0.001 |

Notes: Data were presented as counts (percentages) or median (upper-lower quartiles) as deem applicable. As appropriate, the Chi-square test or Kruskal–Wallis test was used for intergroup comparison.

Abbreviations: NIHSS indicates National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TFEB, transcription factor EB; WBC, white blood cell; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure.

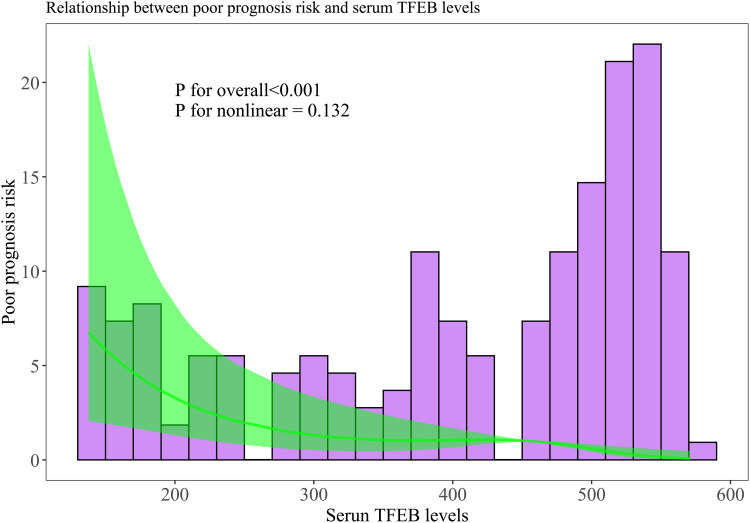

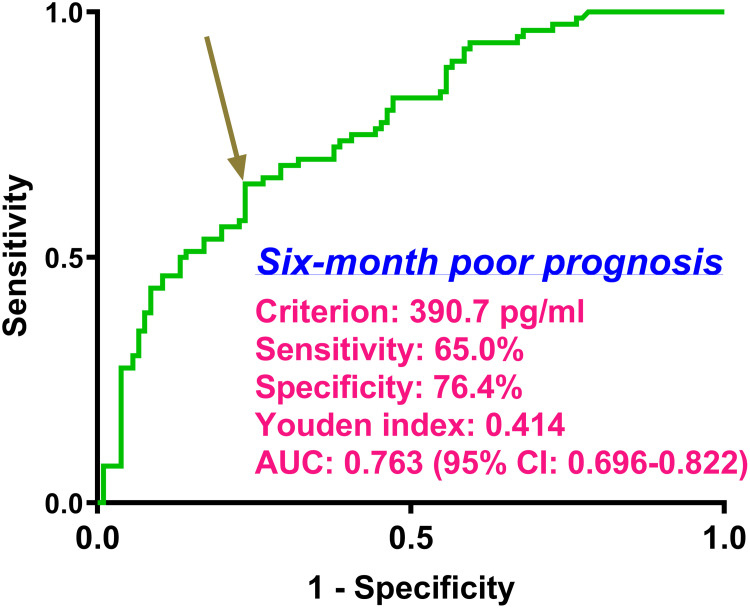

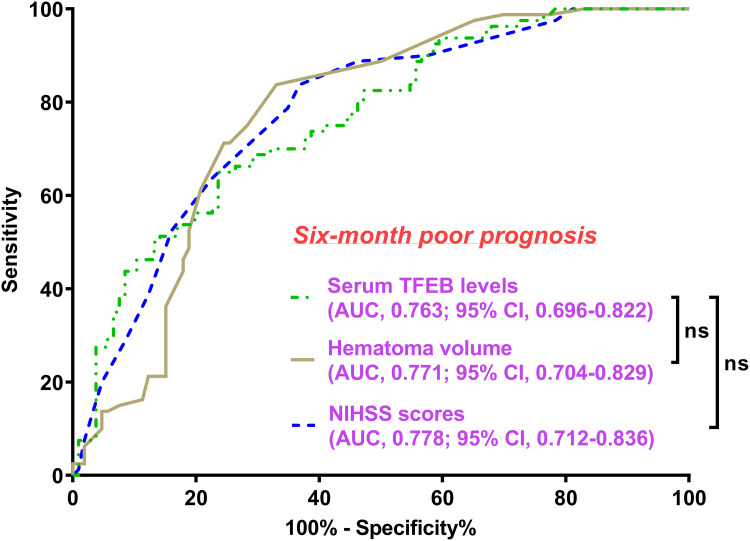

Serum TFEB levels were linearly correlated with poor prognosis probability (P for nonlinear > 0.05; Figure 6) and were in the position of effective discrimination ability on the risk of poor prognosis in the environment of ROC curve analysis, wherein an appropriate value of serum TFEB levels was identified using the Youden method (Figure 7). As described in Table 1, patients with poor prognosis, relative to those with good prognosis, tended to be significantly older, were apt to occupy a substantially higher percentage of diabetes mellitus, were prone to possess markedly higher proportions of SAP, dysphasia, and vomiting, were likely to have a profoundly higher chance of intraventricular hemorrhage, and had a markedly higher NIHSS score, hematoma volume, blood glucose levels, and lower serum TFEB levels (all P<0.05). Following the incorporation of these ten significantly distinct factors into the binary logistic regression model, serum TFEB level (OR, 0.994; 95% CI, 0.989–0.997; P=0.024), appearance of SAP (OR, 2.885; 95% CI, 1.453–5.729; P=0.015), NIHSS score (OR, 1.206; 95% CI, 1.060–1.371; P=0.004), and hematoma volume (OR, 1.070; 95% CI, 1.016–1.127; P=0.011) were found to be independent predictive factors of poor prognosis. Here, serum TFEB levels displayed an analogous predictive ability for poor prognosis to NIHSS scores and hematoma volume (both P>0.05; Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Restricted cubic spline for assessment of relationship between serum transcription factor EB levels and risk of poor prognosis at six-month mark following intracerebral hemorrhage. A statistical demonstration of linear correlation was observed between serum-based transcription factor EB levels and the likelihood of a poor six-month prognosis post-acute intracerebral hemorrhage (P for nonlinear >0.05).

Abbreviation: TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Figure 7.

Discrimination efficiency as to serum transcription factor EB levels on possibility of poor prognosis at six months post-acute intracerebral hemorrhage. With the help of the receiver operating characteristic curve, a poor prognosis was anticipated based on serum transcription factor EB levels. In addition, using the Youden approach, a selected value of serum-based transcription factor EB levels was suitable for prognosis prediction. AUC was indicative of the area under the curve (95% CI, 95% confidence interval).

Figure 8.

Comparison of discrimination capabilities of different factors on probability of poor prognosis at six months following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. By manipulating the receiver operating characteristic curve, serum transcription factor EB levels had an area under the curve of nonsignificant distinction between the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores and hematoma volume (both P>0.05).

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ns, non-significant; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Serum TFEB Levels and Post-ICH SAP, as Well as Mediation Effect of SAP

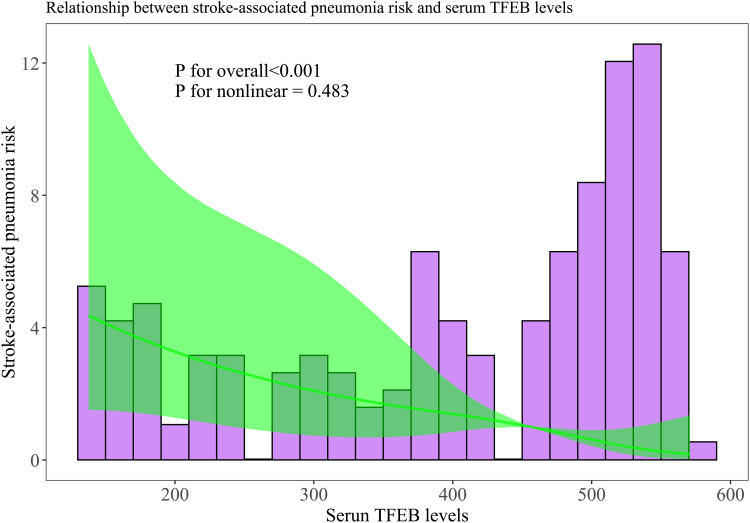

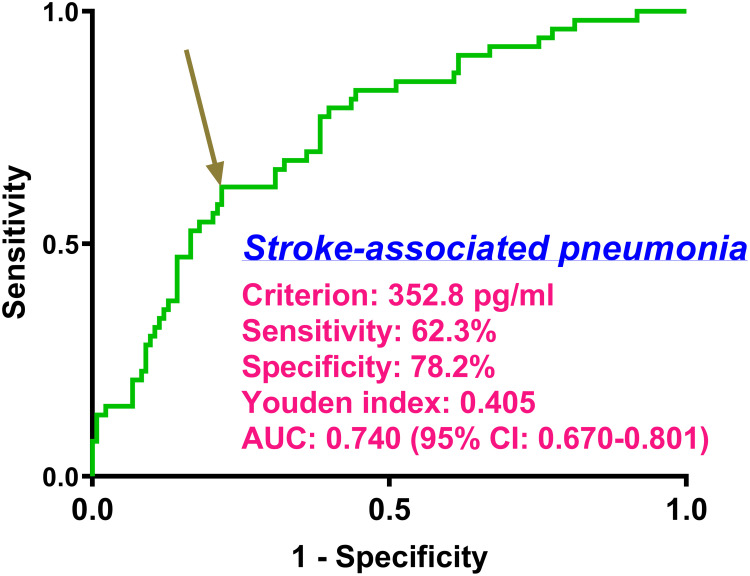

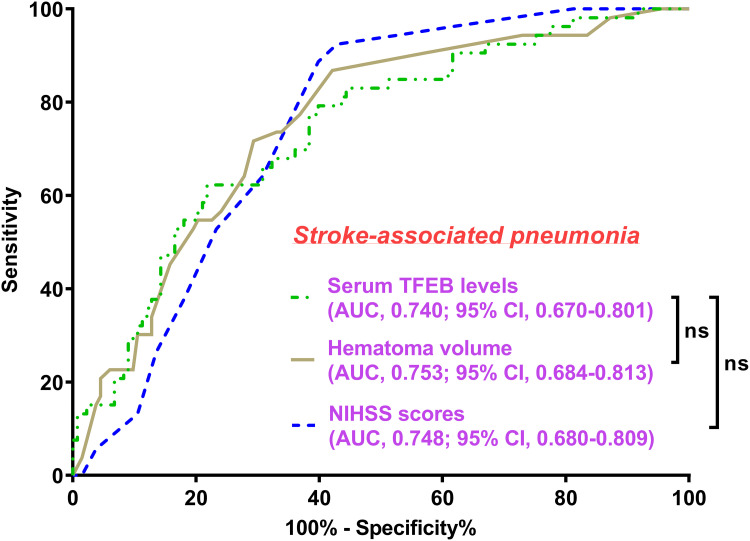

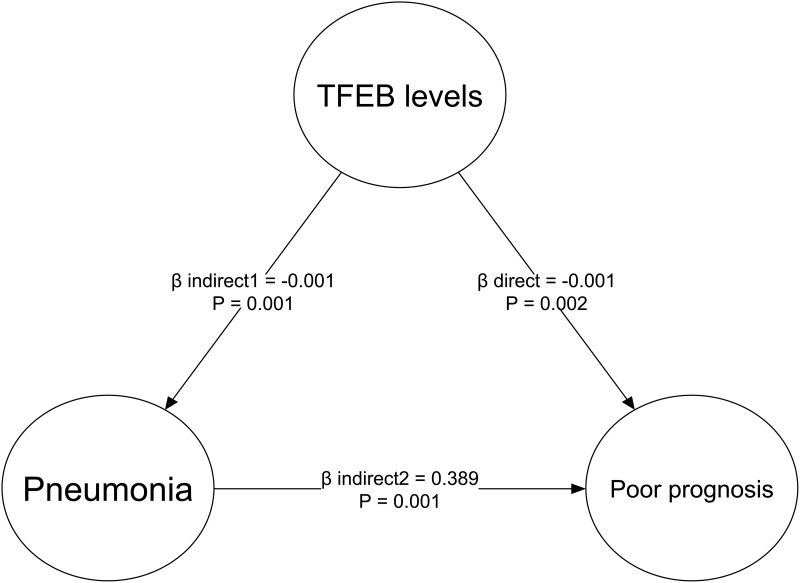

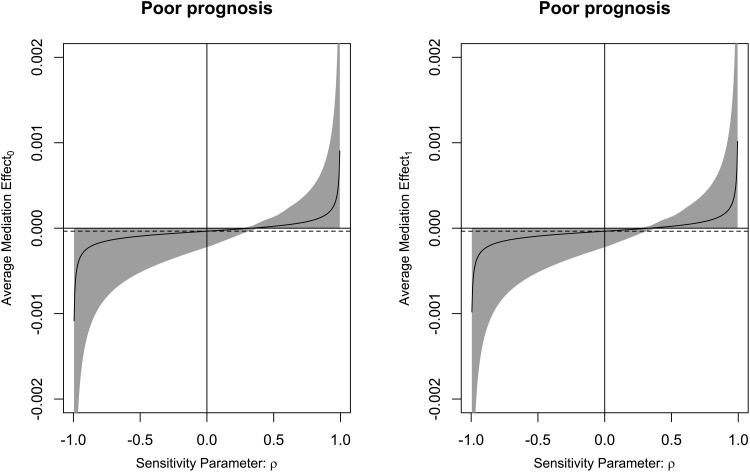

There was a linear correlation between the serum TFEB levels and the likelihood of SAP (P for nonlinearity > 0.05; Figure 9). Serum TFEB levels effectively distinguished the possibility of SAP in the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, and an optimal cutoff value of serum TFEB levels was selected for SAP prognostication by applying the Youden method (Figure 10). Table 1 shows that sufferers for SAP, over those without SAP, had significantly older age, held substantially higher proportions of dysphasia, vomiting and intraventricular hemorrhage, as well as possessed markedly higher NIHSS score, hematoma volume, blood glucose levels and lower serum TFEB levels (all P<0.05). After integrating these eight substantially different variables into the binary logistic regression model, serum TFEB levels (OR, 0.996; 95% CI, 0.994–0.999; P=0.020), NIHSS score (OR, 1.196; 95% CI, 1.069–1.350; P=0.006), and hematoma volume (OR, 1.065; 95% CI, 1.009–1.124; P=0.023) were found to be the three predictors of independent association with poor prognosis. In addition, serum TFEB levels exhibited a similar anticipation capability for SAP as NIHSS scores and hematoma volume (both P>0.05; Figure 11). As shown in Figure 12, SAP mediated the association between serum TFEB level and poor prognosis by 28.0%. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the mediation effect was statistically significant (ρ=0.355; P<0.001; Figure 13).

Figure 9.

Restricted cubic spline with respect to the relationship between serum-based transcription factor EB levels and the probability of stroke-associated pneumonia following intracerebral hemorrhage. Statistical confirmation revealed a linear relationship between serum-based transcription factor EB levels and the possibility of stroke-associated pneumonia following acute intracerebral hemorrhage (P for nonlinear >0.05).

Abbreviation: TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Figure 10.

Anticipation effect of serum transcription factor EB levels on stroke-associated pneumonia following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Within the framework of the receiver operating characteristic curve, stroke-associated pneumonia was well predicted by the serum transcription factor EB levels. Alternatively, using the Youden method, a chosen value of serum-based transcription factor EB levels is appropriate for pneumonia prediction.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 11.

Differences of discrimination performances of multiple variables on probability of stroke-associated pneumonia following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Serum transcription factor EB levels took possession of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of statistical similarity as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores and hematoma volume (both P>0.05).

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ns, non-significant; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Figure 12.

Mediation effect analysis of stroke-associated pneumonia on relationship between serum transcription factor EB levels and poor six-month prognosis following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke-associated pneumonia partially mediated the relationship between serum transcription factor EB levels and poor six-month prognosis following acute intracerebral hemorrhage.

Abbreviation: TFEB, transcription factor EB.

Figure 13.

Verification of mediation effect of stroke-associated pneumonia on association of serum transcription factor EB levels with poor six-month prognosis following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Sensitivity analysis showed that the mediation effect was statistically significant (ρ=0.355; P<0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, circulating TFEB levels have not been quantified in humans with acute brain injury. In this study, we consecutively recruited patients with acute ICH, wherein serum-based TFEB levels were measured in patients, together with controls, along with alterations in serum TFEB levels, and assessed its implication as a potential prognostic biomarker of ICH. Our first finding was that serum TFEB levels were significantly reduced in patients compared with controls. Second, serum TFEB levels substantially diminished with increasing NIHSS scores and hematoma volumes. Of note, serum TFEB levels were independently related to poor six-month prognosis and SAP, and their predictive ability resembled that of NIHSS scores and hematoma volume. Intriguingly, the association between serum-based TFEB levels and poor prognosis is partly mediated by SAP. In summary, serum-based TFEB may be a prognostic biochemical indicator of the clinical value of ICH.

Upregulation or overexpression of TFEB improves neurological function after cerebral ischemia, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and spinal cord injury.11,13,14,22–24 Several pathophysiological mechanisms with respect to TFEB’s protective effects in acute brain injury diseases have been evidenced enough, including regulation of cellular metabolism, restoration of autophagy-lysosome pathway dysregulation, amelioration of aberrant mitochondrial function, repression of oxidative stress, inhibition of neuroinflammation, depression of neuronal apoptosis, facilitation to angiogenesis and more.11,13,14,22–24 Currently, TFEB is considered a therapeutic target for acute brain injury.

TFEB was reduced in brain tissues of animals with cerebral ischemia and subarachnoid hemorrhage.11,22–24 In addition, there is a lower expression level of TFEB in brain biopsies from patients with Alzheimer’s disease.12 Considering the protective characteristics of TFEB’s protective particularities,11,13,14,22–24 TFEB reduction may be depleted in response to brain injury. In addition, serum-based TFEB levels are substantially lower in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease than in cognitively-unimpaired subjects.15 Similarly, our study showed that serum TFEB levels were markedly diminished after ICH in humans, in contrast to healthy controls. Owing to the factual existence of a series of brain injury diseases, such as traumatic brain injury, ICH, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and so forth, which are frequently accompanied by systemic injuries, including systemic inflammatory response syndrome, cerebrocardiac syndrome, and acute lung injury,25–28 a decline in TFEB in the blood may be a consequence of systemic injuries.

Severity assessment, preferably by NIHSS score and hematoma size, is of utmost importance in clinical practice for ICH.29 In this study, serum TFEB levels were inversely correlated with NIHSS scores and hematoma size among individuals with ICH, suggesting that serum TFEB may be strongly linked to bleeding intensity. The mRS is an ordinal categorical variable. In ordinal regression analysis, serum TFEB levels were independently associated with ordinal mRS scores in this cohort of post-ICH patients. The mRS was converted into a binary categorical variable. Following the verification of the linear relationship between serum TFEB levels and poor prognosis at six-month mark following ICH, serum TFEB levels, NIHSS scores, SAP, and hematoma volume were confirmed by multivariate analysis to be the four independent predictors of poor prognosis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were created to assess discrimination efficiency. Therefore, the anticipation ability of serum TFEB levels was equivalent to that of NIHSS score and hematoma volume. Taken together, serum TFEB levels may be a promising biomarker for predicting ICH prognosis.

SAP is a common complication of ICH.30 Our study and other studies30,31 have provided sufficient evidence to support the notion that SAP appearance is highly associated with a higher risk of worse neurological outcomes following ICH. The linear relationship between TFEB levels and the likelihood of SAP and its independent association with SAP are demonstrated in this study. Moreover, the predictive capability of serum TFEB levels on SAP was compared with those of NIHSS scores and hematoma volume; therefore, analogous efficiencies were confirmed under the ROC curve. Notably, the partial mediation effect of SAP was associated of serum TFEB levels with a poor prognosis six months after acute ICH. Overall, serum TFEB levels may be relevant to SAP emergence and SAP may, in part, bridge the gap between serum TFEB levels and poor prognosis following ICH.

This study had several limitations. First, serum TFEB levels were measured only at the time of admission, thereby limiting the investigation of the prognostic value of this biomarker at other time points following ICH. In the future, blood samples could be obtained at multiple time intervals to master temporal trends in serum TFEB levels after acute ICH, wherein some useful information could be provided to assess the prognostic significance of serum TFEB. Second, a total of 186 patients were included in this study. Although the sample size was deemed adequate for clinical analysis, all conclusions should be repeatedly validated in large-scale cohort studies for further generalization. Third, the current study was designed to well unravel prognostic role of serum TFEB and its predictive ability for SAP in this scenario of ICH and thus the TFEB should be considered in future studies for other different pathologies so as to further explore its other applicable value in medical field. Finally, only TFEB was investigated here to discern its prognostic value and predictive ability for SAP in this context of ICH. As a fact, if more biomarkers, including serum transthyretin, can be analyzed, it will be valuable because a better one could be picked out as a useful prognostic factor from multitudinous candidates.

Conclusions

Serum TFEB levels of decline after ICH are evidently correlated with hemorrhagic magnitude and are independently associated with SAP and poor prognosis at six months following ICH, with a similar prognostic predictive ability as NIHSS scores and hematoma volume. SAP may partially mediate the association between serum TFEB level and poor prognosis after ICH. In conclusion, TFEB may be considered as a meaningful serological indicator for aiding in the severity assessment and outcome prognostication of ICH.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all study participants, their relatives, and the staff at the recruitment centers for their invaluable contributions.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY21H090008), the Key Project Jointly Built by Zhejiang Province, Ministry (WKJ-ZJ-2340), and General Project Funds from the Health Department of Zhejiang Province (2025KY001).

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are personal data, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Puy L, Boe NJ, Maillard M, Kuchcinski G, Cordonnier C. Recent and future advances in intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 2024;467:123329. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2024.123329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magid-Bernstein J, Girard R, Polster S, et al. Cerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology, treatment, and future Directions. Circ Res. 2022;130(8):1204–1229. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee TH. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2024;15:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000542566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mai LM, Joundi RA, Katsanos AH, Selim M, Shoamanesh A. Pathophysiology of intracerebral hemorrhage: recovery trajectories. Stroke. 2024;56:783–793. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.124.046130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Chen Y, Chen R, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram model for prediction of stroke-associated pneumonia associated with intracerebral hemorrhage. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):633. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04310-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan T, Wang ZF, Wu XY, et al. Plasma SIRT3 as a biomarker of severity and prognosis after acute intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective cohort study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:2199–2210. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S376717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang W, Lu T, Shan H, et al. RVD2 emerges as a serological marker in relation to severity and six-month clinical outcome following acute intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective cohort study from a single academic institution. Clin Chim Acta. 2025;565:119988. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2024.119988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Liu M, Yan T, et al. Plasma PRPC levels correlate with severity and prognosis of intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2022;13:913926. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.913926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan X, Yang L, Fu X, et al. Transcription factor EB, a promising therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. PeerJ. 2024;12:e18209. doi: 10.7717/peerj.18209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shao J, Lang Y, Ding M, Yin X, Cui L. Transcription factor EB: a promising therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024;22(2):170–190. doi: 10.2174/1570159X21666230724095558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu W, Chu H, Yang C, Li X. Transcription factor EB (TFEB) promotes autophagy in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Neurosurg Rev. 2024;47(1):741. doi: 10.1007/s10143-024-02879-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Wang R, Xu S, Lakshmana MK. Transcription factor EB is selectively reduced in the nuclear fractions of Alzheimer’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis brains. Neurosci J. 2016;2016:4732837. doi: 10.1155/2016/4732837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Wang W, Hu X, et al. Heterophyllin B enhances transcription factor EB-mediated autophagy and alleviates pyroptosis and oxidative stress after spinal cord injury. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(14):5415–5435. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.97669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Z, Zhang Y, Liu Y, et al. Melibiose confers a neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by ameliorating autophagy flux via facilitation of TFEB nuclear translocation in neurons. Life. 2021;11(9):948. doi: 10.3390/life11090948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veverová K, Laczó J, Katonová A, et al. Alterations of human CSF and serum-based mitophagy biomarkers in the continuum of Alzheimer disease. Autophagy. 2024;20(8):1868–1878. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2024.2340408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X, Chen S, Li C, et al. Trehalose alleviates crystalline silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis via activation of the TFEB-mediated autophagy-lysosomal system in alveolar macrophages. Cells. 2020;9(1):122. doi: 10.3390/cells9010122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu W, Li CC, Lu X, Bo LY, Jin FG. Overexpression of transcription factor EB regulates mitochondrial autophagy to protect lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Chin Med J. 2019;132(11):1298–1304. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwah LK, Diong J. National institutes of health stroke scale (NIHSS). J Physiother. 2014;60(1):61. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kothari RU, Brott T, Broderick JP, et al. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke. 1996;27(8):1304–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith CJ, Kishore AK, Vail A, et al. Diagnosis of stroke-associated pneumonia: recommendations from the pneumonia in stroke consensus group. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2335–2340. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanley DF, Thompson RE, Rosenblum M, et al. Efficacy and safety of minimally invasive surgery with thrombolysis in intracerebral haemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE III): a randomised, controlled, open-label, blinded endpoint Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10175):1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30195-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Xue X, Zhang H, et al. Neuronal-targeted TFEB rescues dysfunction of the autophagy-lysosomal pathway and alleviates ischemic injury in permanent cerebral ischemia. Autophagy. 2019;15(3):493–509. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1531196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Cui X, Lv H, et al. Remote ischemic postconditioning attenuates damage in rats with chronic cerebral ischemia by upregulating the autophagolysosome pathway via the activation of TFEB. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;115:104475. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu X, Liu Y, Zhang H, et al. Pseudoginsenoside F11 ameliorates the dysfunction of the autophagy-lysosomal pathway by activating calcineurin-mediated TFEB nuclear translocation in neuron during permanent cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2021;338:113598. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehme AK, Hays AN, Kicielinski KP, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome and outcomes in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2016;25(1):133–140. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0255-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tapia-Pérez JH, Karagianis D, Zilke R, Koufuglou V, Bondar I, Schneider T. Assessment of systemic cellular inflammatory response after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;150:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan TH, Huang M, Gedansky A, et al. Prevalence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung. 2021;199(6):603–610. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00491-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang XC, Gao SJ, Zhuo SL, et al. Predictive factors for cerebrocardiac syndrome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a retrospective cohort study. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1192756. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1192756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee TH. Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2025;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000542566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji R, Shen H, Pan Y, et al. Risk score to predict hospital-acquired pneumonia after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2620–2628. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vial F, Brunser A, Lavados P, Illanes S. Intraventricular bleeding and hematoma size as predictors of infection development in intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(11):2708–2711. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are personal data, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.