Abstract

Background

Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 (S1PR3) has been implicated in promoting tumor progression in various cancers. However, the role and molecular mechanisms of S1PR3 in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) remain poorly understood. The aims of this study were to investigate the function of S1PR3 in OSCC progression and its potential as a therapeutic target.

Method

The expression of S1PR3 was determined through qPCR, Western blotting analysis, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and the TCGA database. The correlation between S1PR3 expression and clinical prognosis was analyzed using the TCGA database and IHC. The effects of S1PR3 on OSCC cell proliferation and cell cycle were investigated through CCK-8 assay, colony formation assay, EdU incorporation assay, cell cycle analysis, and a xenograft mouse model. The potential mechanisms through which S1PR3 affects the OSCC cell cycle were explored using RNA-seq and a cell cycle array. The effects of combining S1PR3 antagonist with cisplatin on OSCC cell growth were examined through CCK-8 and EdU incorporation assays.

Results

S1PR3 was overexpressed in OSCC and the upregulation of S1PR3 in OSCC was correlated with unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics and adverse prognosis. Targeting S1PR3 reduced AKT phosphorylation, which led to a downregulation of WEE1, a kinase involved in cell cycle regulation. This downregulation resulted in reducing CDC2 phosphorylation, disrupting the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint and inhibiting OSCC cell proliferation. Furthermore, the combination of S1PR3 antagonist exhibited synergistic inhibitory effects on OSCC cell growth when combined with cisplatin.

Conclusions

These findings reveal a critical role for S1PR3 in regulating OSCC cell cycle via the AKT/WEE1/CDC2 pathway, thus offering a basis for developing treatment strategies for OSCC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06582-4.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3, AKT signaling pathway, WEE1, Cell cycle

Introduction

Head and neck cancers rank as the sixth most prevalent cancer globally, with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) constituting approximately 90% of all cases [1, 2]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 statistics, an estimated 377 713 new cases and 177 757 deaths due to oral cancer are reported annually [3]. Current OSCC treatments include primarily surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, which possess limited efficacy, with 25–50% of OSCC patients experiencing recurrence [4]. In addition, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are frequently associated with adverse effects, including dermatitis, osteoradionecrosis and nephrotoxicity, thus significantly impairing patients’ quality of life [5, 6]. Moreover, the tendency of OSCC to metastasize and recur combined with low cure rates and high mortality rates constitute substantial challenges for patients and their families [7]. Therefore, it is imperative to advance research into the molecular basis of OSCC development to identify novel treatment targets.

As members of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs) are categorized into five distinct subtypes, i.e., S1PR1–S1PR5. Therapies targeting these receptors are widely recognized as promising strategies, given their prior use in treating immune diseases such as ulcerative colitis and multiple sclerosis [8]. Emerging evidence suggests that dysregulated S1PR expression is pivotal in the progression of multiple cancers [9]. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the S1PR family may constitute potential targets for preventing OSCC progression. More evidence suggests that S1PR3 contributes to the progression of multiple cancers, including osteosarcoma, gastric cancer and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, thus influencing key biological processes within tumor cells such as proliferation, migration, apoptosis and invasion [10]. However, the specific biological mechanisms by which S1PR3 contributes to OSCC remain to be clarified.

In the present study, we demonstrated that S1PR3 was overexpressed in OSCC and correlated with advanced clinical stages and adverse prognosis in OSCC patients, suggesting that S1PR3 may act as a pro-tumorigenic factor in OSCC development. Notably, targeting S1PR3 significantly reduced OSCC cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. Further mechanistic investigations demonstrated that targeting S1PR3 inhibited WEE1 expression via the AKT signaling pathway, which subsequently reduced CDC2 phosphorylation and disrupted the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. Moreover, our results showed that the S1PR3 antagonist CAY10444 exhibited synergistic inhibition of OSCC cell growth when combined with cisplatin. Therefore, the S1PR3/AKT/WEE1 signaling pathway constitutes a promising potential target for the treatment of OSCC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Human immortalized keratinocyte cell line (HaCat) and HNSCC cell lines WSU-HN4, WSU-HN6, CAL27 and WSU-HN30 were obtained from Department of Oral Oncology, Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2, using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin.

Reagents and antibodies

The S1PR3 antagonist CAY10444 (Selleckchem, TX, USA) and the AKT agonist SC79 (Selleckchem) were prepared and stored following the manufacturer's guidelines. S1PR3 and S1PR4 antibodies were obtained from Abcam PLC (Cambridge, UK). S1PR1, S1PR2 and S1PR5 antibodies were obtained from ProteinTech Group, Inc. (IL, USA). AKT, p-AKT, WEE1, CDC2, p-CDC2 and GAPDH antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (MA, USA).

Bioinformatics analysis

Transcriptomic data of HNSCC patients were retrieved from TCGA. Based on the median expression level, patients were classified into S1PR3 high- and low-expression groups. The correlation between S1PR3 expression and overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), as well as progression-free interval (PFI) was evaluated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Tissue specimens and tissue microarray

Tumor tissues and adjacent tissues from OSCC patients were collected from the Department of Oral Pathology, Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. A tissue microarray (TMA) was constructed by Taize Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) using samples from OSCC patients.

Xenograft mouse model

Four-week-old male BALB/c nude mice were sourced from the Animal Experiment Center of the Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China and reared in the same facility. 2 × 10⁷ S1PR3 knockdown CAL27 cells, along with control cells, were subcutaneously injected in mice’s inguinal region. Once xenograft tumors became palpable, mice body weight and tumor volume (tumor volume = tumor width2 × tumor length/2) were recorded every five days. After 20 days, the mice were euthanized and the excised xenograft tumors were weighed and captured in images.

For chronic drug administration, 2 × 10⁷ S1PR3 knockdown CAL27 cells, along with control cells, were subcutaneously injected in mice’s inguinal region. Once xenograft tumors reached an appropriate size, the mice were divided into control and treatment groups using random assignment (5/group), which were intraperitoneal injected with SC79 (20 mg/kg) or dimethyl sulfoxide. Drugs were administered every three days and mice body weight and tumor volume were recorded. After 12 days, the mice were euthanized and the excised xenograft tumors were weighed and captured in images. Excised tumor sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in preparation for immunohistochemical (IHC) assays. See the section on IHC assays in Materials and Methods for details.

IHC assays

IHC assays were performed to evaluate S1PR3 expression in clinical samples and protein levels of S1PR3, p-AKT, WEE1 and Ki67 in xenograft tumors from nude mice. Paraffin-embedded OSCC sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 min. Sections were treated with 3% H₂O₂ for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Following overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C, sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Visualization was achieved using DAB, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. Stained sections were analyzed under a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

RNA extraction, qPCR validation and PCR array

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, CA, USA) and then converted into cDNA with a reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). cDNA amplification was carried out via qPCR with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (TaKaRa) in triplicate in a 96-well plate. qPCR processes were conducted on an Applied Biosystems™ 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies, NY, USA) employing primers specified in Supplementary Table 1 and in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to measured mRNA levels, with β-actin serving as the reference gene. Cell cycle-related genes showing significant differential expression after CAY10444 treatment were identified using a human cell cycle PCR array kit (Wcgene Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

Correlation between S1PR3 expression and clinicopathological features in patients with OSCC (n = 52)

| Number(52) | S1PR3 expression | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| Age | ||||

| < 60 | 32 | 14 | 18 | 0.393 |

| ≥ 60 | 20 | 12 | 8 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 43 | 23 | 20 | 0.465 |

| Female | 9 | 3 | 6 | |

| Location | ||||

| Tongue | 30 | 14 | 16 | 0.532 |

| Gingiva | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Pharynx oralis | 13 | 8 | 5 | |

| Palatal | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Others | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| AJCC stage | ||||

| I | 3 | 3 | 0 | P < 0.01 |

| II | 7 | 7 | 0 | |

| III | 32 | 14 | 18 | |

| IV | 10 | 2 | 8 | |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 + T2 | 32 | 20 | 12 | P < 0.05 |

| T3 + T4 | 20 | 6 | 14 | |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | 23 | 16 | 7 | P < 0.05 |

| N1 + N2 | 29 | 10 | 19 | |

Gene knockdown experiments

Short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) (Genomeditech, Shanghai, China) were employed to silence S1PR3 in OSCC cells. Supplementary Table 2 contains the shRNA sequences designed to target S1PR3. Stable S1PR3 knockdown cell lines were established via lentivirus-mediated gene transfer. After stable growth was achieved, the extent of S1PR3 silencing was verified by qPCR and western blotting analyses.

Western blotting analysis

After collection, the cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (Epizyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and total protein was evaluated with a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Equal quantities of total protein samples were submitted to electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide gels and subsequently moved to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., CA, USA). The aforementioned membranes were treated at ambient temperature for 1 h with rapid blocking buffer (Epizyme) to inhibit non-specific binding and then exposed overnight to primary antibodies. Next, membranes were treated with secondary antibodies at ambient temperature for 1 h. Employing an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Epizyme), signals were detected following the manufacturer's guidelines.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and colony formation assays

OSCC cells (5000/well) were plated into 96-well plates. After treatment, cultures were terminated at designated time points, and plates were placed in a cell incubator for 2 h after adding CCK8 solution (10 μL/well, Dojindo Laboratories Co., Ltd., Kumamoto, Japan). Cell viability was determined from absorbance at 450 nm, measured by a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA).

OSCC cells (800/well) were plated into 6-well plates. After treatment, cultures were terminated at specified time points, followed by the addition of 4% paraformaldehyde (1 mL/well) for cell fixation for 30 min. After washing once with PBS, 1% crystal violet staining solution was deposited into wells, and then subjected to a 30-min incubation at room temperature. Cells were rinsed with running water and left to air dry. Afterward, photographs of the cells were taken, and the cell colony count was performed.

Cell proliferation assay

OSCC cells (1 × 105/well) were plated into 12-well plates. After treatment, cultures were terminated at designated time points. DNA replication was assessed with the 5-ethynyl-2ʹdeoxyuridine (EdU) detection kit (Beyotime). EdU-positive cells were subsequently observed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell cycle analysis

S1PR3 knockdown CAL27 cells, along with control cells, were plated in 6-well plates and kept in a cell incubator for three days. Cells from each experimental group were collected in flow cytometry tubes for cell cycle analysis. OSCC cells were plated into 6-well plates and treated with 0 μM, 300 μM, or 400 μM CAY10444 for 24 h. Pre-cooled 70% ethanol solution was added to flow cytometry tubes to fix cells overnight. Following the addition of PI/RNase staining buffer, cells were stained in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines, and the cell cycle profile was analyzed in a flow cytometer (BD FACSCanto II, CA, USA).

RNA-seq analysis

Following RNA isolation from OSCC cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), RNA-seq libraries were generated with the Ovation Universal RNA-Seq System 1–16 (NuGEN Technologies, Inc., CA, USA). The indexed libraries were multiplexed in a single flow cell and sequenced using 75-base pair single-end reads on a NextSeq 500 High Output Kit v2 (75 cycles; Illumina, Inc., CA, USA), performed by BGI Group (Beijing, China).

Prediction analysis of immunotherapy responsiveness

To evaluate immunotherapy responsiveness in the TCGA HNSCC cohort, TIDE scores and Immune Prognostic Scores (IPS) were calculated for each patient.

Analysis of targeted agents sensitivity

The"oncopredict"R package was used to estimate the IC50 values of targeted agents in HNSCC patients with high or low S1PR3 expression. This analysis aimed to evaluate their differential sensitivity to pharmacological treatments.

Cell apoptosis analysis

Cell apoptosis was assessed using Annexin V-FITC/PI dual staining. Following treatment, cells were harvested, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in binding buffer. Subsequently, 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL of PI were added, and the cells were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Apoptosis was then analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCanto II, CA, USA).

γ-H2 AX immunofluorescence

CAL27 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with the indicated drugs. At the designated time points, the culture was terminated. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed for 15 min, followed by three washes. After blocking at room temperature for 20 min, cells were incubated with anti-γ-H2 AX primary antibody at 4 °C overnight and then washed three times. Subsequently, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, followed by two washes. Fluorescence signals were observed and imaged under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with γ-H2 AX appearing as green fluorescence.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to assess correlations between S1PR3 expression and clinicopathological features. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Multiple group comparisons were carried out using one-way or two-way ANOVA. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and the level of statistical significance was considered according to the p values obtained (i.e., < 0.05, < 0.01, or < 0.001).

Results

The overexpression of S1PR3 is correlated with poor prognosis in OSCC patients

S1PRs have been found to show altered expression in various cancers and influence cancer progression [11]. Thus, we examined S1PR expression levels in HaCat, HNSCC cell lines using qPCR and western blotting analyses. The findings revealed that S1PR1, S1PR3 and S1PR4 were upregulated in HNSCC cell lines, with S1PR3 exhibiting higher expression in most HNSCC cell lines compared to the other S1PRs (Supplementary Fig. 1 A, B). Subsequently, HNSCC transcriptome sequencing data retrieved from the TCGA database were employed to assess the clinical relevance of S1PR3 mRNA levels in HNSCC. The data revealed that S1PR3 was abnormally upregulated in HNSCC tissues when contrasted with normal tissues (Fig. 1A, B). Additionally, we performed IHC staining to confirm S1PR3 expression in human tissues. The findings indicated that S1PR3 exhibited elevated expression in clinical OSCC tissues relative to adjacent tissues (Fig. 1C). Importantly, elevated levels of S1PR3 expression correlated with advanced pathological stages in HNSCC patients (Fig. 1D, E).

Fig. 1.

The overexpression of S1PR3 was correlated with poor prognosis in OSCC patients. A, B Analysis of S1PR3 mRNA levels in HNSCC patients according to the TCGA database. S1PR3 mRNA levels were markedly increased in HNSCC tissues (A). S1PR3 expression in HNSCC was higher compared to the matched normal samples (B). C S1PR3 expression patterns in OSCC tissues and adjacent tissues were identified through IHC staining. D, E Analysis of S1PR3 mRNA levels in HNSCC patients according to the TCGA database. Upregulated S1PR3 expression demonstrated a significant association with T (D) and N stage (E). F, G The relationship between S1PR3 protein levels and clinicopathological characteristics was observed in 52 OSCC patients. H–J Survival analysis of the correlations between S1PR3 mRNA levels and OS, DSS and PFI of HNSCC patients using TCGA database. Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 μm

Furthermore, the association between S1PR3 levels and clinicopathological characteristics among 52 OSCC patients was thoroughly examined. After the quantification of IHC images, it was demonstrated that S1PR3 expression was markedly elevated in stage III/IV tumors when contrasted with stage I/II tumors (Fig. 1F, G). Moreover, S1PR3 upregulation was significantly associated with AJCC (P < 0.001), T (P < 0.05) and N stages (P < 0.05) in OSCC patients (Table 1). Subsequently, the predictive value of S1PR3 in HNSCC patients was investigated. As shown in Fig. 1H–J, among the S1PR family, only high S1PR3 expression exhibited a negative correlation with patient prognosis. In particular, HNSCC patients with higher S1PR3 expression had shorter OS (HR = 2.67, P < 0.001), DSS (HR = 3.13, P < 0.001) and PFI (HR = 2.33, P < 0.001). In addition, afatinib is a second-generation EGFR TKI inhibitor that is used as a second-line treatment for recurrent or metastatic HNSCC [12]. The analysis of TCGA data showed that high S1PR3 expression was associated with higher afatinib IC50 values, increased TIDE scores and reduced IPS (Supplementary Fig. 2 A–C). Therefore, S1PR3 was found to promote OSCC progression, thus playing a crucial role in predicting clinical outcomes in OSCC patients.

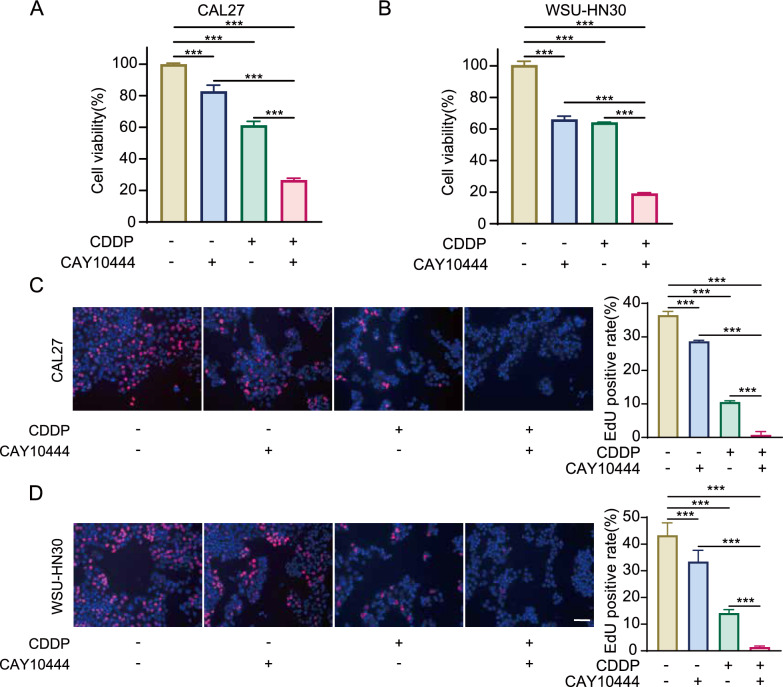

Fig. 7.

S1PR3 antagonist combined with cisplatin suppressed OSCC cells growth. A, B CCK8 assays were performed on CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells subjected to CAY10444, CDDP, or the combination of CAY10444 and CDDP. C, D EdU incorporation assays were conducted on CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells subjected to CAY10444, CDDP, or the combination of CAY10444 and CDDP. Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 μm

S1PR3 inhibition suppresses OSCC cell growth

Based on the above-discussed observations, S1PR3 was frequently overexpressed in OSCC, which might contribute to tumor initiation and progression. Therefore, we constructed two lentiviral plasmids, S1PR3-SH1 and S1PR3-SH2, to achieve S1PR3 knockdown and thereby explore the impact of S1PR3 on the biological functions of OSCC cells. Furthermore, CAL27 cells were selected to establish stable knockdown cell lines due to their elevated S1PR3 expression. The efficiency of knockdown was verified by qPCR (Fig. 2A) and western blotting analyses (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

S1PR3 inhibition suppressed OSCC cell growth. A, B Establishment of S1PR3 knockdown CAL27 cell lines. The efficiency of knockdown was verified using qPCR (A) and western blotting analysis (B). C Cell viability of S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27 cells was evaluated by the CCK8 assay. D Colony-forming ability of S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27 cells was evaluated by the colony formation assay. E The results of the CCK8 assay indicated that the S1PR3 antagonist inhibited the viability of CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells in a dose-dependent manner (25 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, 200 μM, 300 μM and 400 μM vs 0 μM). F The results of the colony formation assay indicated that the S1PR3 antagonist inhibited the colony-forming ability of CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells in a dose-dependent manner (25 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, 200 μM, 300 μM and 400 μM vs 0 μM). Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

CCK8 and colony formation assays were subsequently performed to examine the impact of S1PR3 inhibition on OSCC cell proliferation. The analysis showed that viability and colony count of OSCC cells were notably decreased by S1PR3 knockdown (Fig. 2C, D). To further validate these observations, OSCC cells were treated with the specific an S1PR3 antagonist, CAY10444, which suppressed OSCC cell growth in a dose-dependent way (Fig. 2E, F). In addition, the results of CCK8 assay demonstrated that inhibiting S1PR3 significantly suppressed the growth of human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma cell line WSU-HN4 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3 A). Therefore, targeting S1PR3 via shRNA or by using a specific antagonist effectively suppressed malignancy of OSCC cells.

Fig. 5.

S1PR3 blockade downregulated WEE1 expression via regulating the AKT signaling pathway. A The signaling pathways that exhibited statistically significant differences after S1PR3 antagonist treatment and S1PR3 knockdown compared to control CAL27 cells were identified by RNA-seq. B The translational levels of S1PR3, p-AKT and AKT in S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27 cells were measured using western blotting analyses. C The translational levels of S1PR3, p-AKT and AKT in S1PR3 antagonist-treated CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells were measured using western blotting analyses. D OSCC cell viability in different groups (control, CAY10444, SC79, CAY10444 + SC79) was measured by the CCK8 assay. E Following SC79 treatment or non-treatment, the viability of S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27 cells was measured by the CCK8 assay. F The translational levels of S1PR3, AKT, p-AKT, WEE1, CDC2 and p-CDC2 in OSCC cells from different groups (control, CAY10444, SC79, CAY10444 + SC79) were measured by western blotting analyses. Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

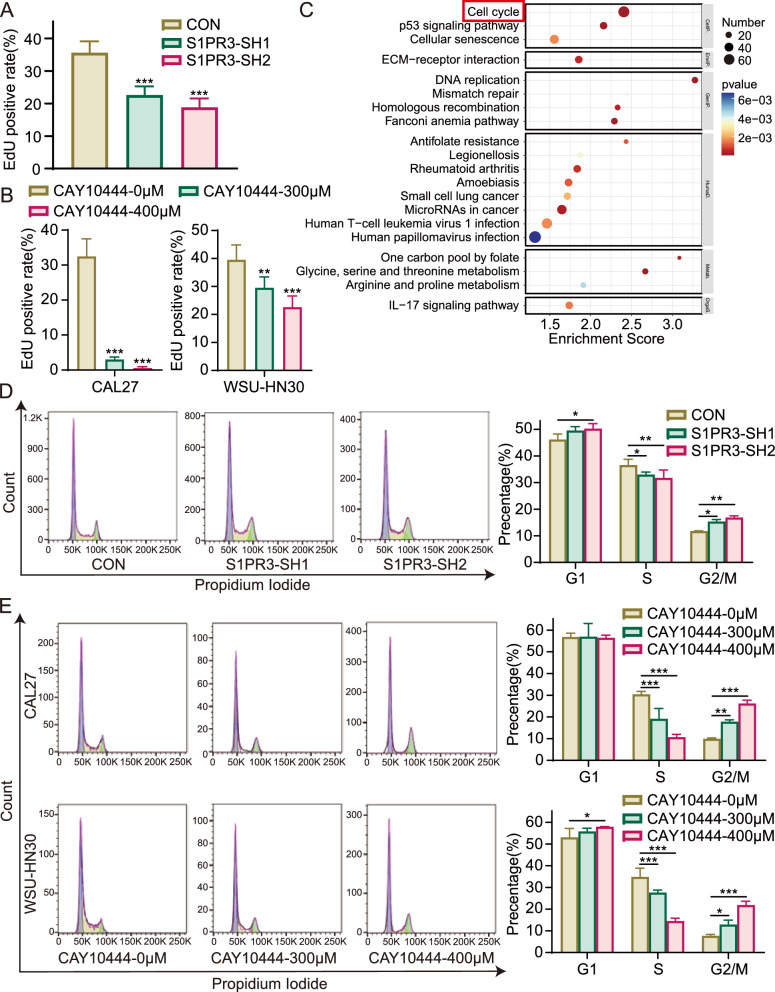

S1PR3 inhibition suppresses OSCC cell proliferation by regulating the cell cycle

The EdU incorporation assay was conducted to evaluate whether reduced S1PR3 expression inhibited OSCC cell proliferation. The analysis demonstrated that the knockdown of S1PR3 in CAL27 cells decreased EdU-positive rates, dropping from 35.64% ± 3.46% to 22.62% ± 2.69% or 18.87% ± 2.72% (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 4 A), indicating a suppressive effect of S1PR3 knockdown on cell proliferation. Comparable findings were noted in OSCC cells subjected to the S1PR3 antagonist (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 4B). CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells were subjected to the antagonist CAY10444 at a range of concentrations. In CAL27 cells, treatment with 300 μM CAY10444 reduced the EdU-positive rate to 3.00% ± 0.70%, with a further decrease to 0.53% ± 0.40% when treated with 400 μM CAY10444, in comparison with the control group rate of 32.47% ± 5.04%. A similar trend was noted in WSU-HN30 cells.

Fig. 3.

S1PR3 inhibition suppressed OSCC cell proliferation by regulating the cell cycle. A The proliferative ability of the knockdown and control CAL27 cells was detected using the EdU incorporation assay at designated time points. B Following treatment with 0 μM, 300 μM, or 400 μM CAY10444, the proliferation of CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells was evaluated using the EdU incorporation assay. C RNA sequencing was conducted on CAY10444-treated and control CAL27 cells, followed by KEGG enrichment analysis to reveal the mechanism by which CAY10444 restrains OSCC cell growth. D The PI staining and flow cytometry were used to assess the cell cycle phases in S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27cells. E Following treatment with 0 μM, 300 μM, or 400 μM CAY10444, the PI staining and flow cytometry were used to assess the cell cycle phases in CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

To better elucidate the role of S1PR3 in OSCC, KEGG enrichment analysis of RNA-seq results was conducted, and the top 20 statistically significantly enriched functional entries were identified. Among these, cell cycle-related genes were particularly enriched in the CAY10444 treatment group (Fig. 3C), suggesting that S1PR3 inhibition might hinder the proliferation of OSCC cells via regulation of cell cycle. Subsequently, we evaluated the effect of S1PR3 inhibition on the distribution of the OSCC cell cycle. As shown in Fig. 3D and E, the percentage of cells in the S phase significantly decreased, while the percentage of cells in the G2/M phase increased after S1PR3 knockdown or antagonist treatment. This indicates that S1PR3 intervention led to a modification in cell cycle regulation. Hence, it can be hypothesized that S1PR3 intervention inhibits cell proliferation by regulating OSCC cell cycle.

S1PR3 inhibition modulates OSCC cell cycle by reducing WEE1 expression

To analyse the molecular basis driving the impact of S1PR3 inhibition on the OSCC cell cycle, a qPCR array targeting 90 cell cycle-related genes was performed. The findings indicated that four genes, i.e., WEE1, GADD45 A, CDKN1 A and CCNA1, were differentially expressed after treatment with CAY10444 compared to control CAL27 cells. WEE1 was downregulated, while GADD45 A, CDKN1 A and CCNA1 were upregulated (Fig. 4A, B). The transcription levels of these four genes were further validated using qPCR, confirming that WEE1 transcription was downregulated in the S1PR3 knockdown group and the presence of the antagonist (Fig. 4C). WEE1, a gene encoding a protein within the serine/threonine kinase family, regulates CDC2 activity via phosphorylation. WEE1 downregulation disrupts the G2/M checkpoint by reducing CDC2 phosphorylation, thereby modulating the cell cycle [13]. Therefore, we further examined WEE1 expression and CDC2 phosphorylation via western blotting analysis. The findings revealed that both WEE1 expression and CDC2 phosphorylation were decreased in S1PR3 knockdown and antagonist-treated OSCC cells (Fig. 4D, E). Thus, it was hypothesized that S1PR3 inhibition might modulate the OSCC cell cycle by downregulating WEE1 expression.

Fig. 4.

S1PR3 inhibition modulated OSCC cell cycle by reducing WEE1 expression. A, B The mRNA levels of genes associated with the cell cycle in S1PR3 antagonist-treated CAL27 cells were analyzed using a qPCR-based cell cycle array. C The mRNA levels of differentially expressed genes in S1PR3 knockdown and antagonist-treated CAL27 cells were validated using qPCR. D Western blotting analysis revealed the translational levels of S1PR3, WEE1, CDC2 and p-CDC2 in CAY10444-treated CAL27 and WSU-HN30 cells. E Western blotting analysis revealed the translational levels of S1PR3, WEE1, CDC2 and p-CDC2 in S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27 cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

S1PR3 inhibition downregulates WEE1 expression by regulating the AKT signaling pathway

Subsequently, gene clustering analysis was used to identify signaling pathways affected by both CAY10444 treatment or S1PR3 knockdown. Compared to control CAL27 cells, the findings indicated that treatment with CAY10444 modulated several signaling pathways, including PI3 K/AKT, PI3 K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK. However, the most significant impact was observed on the PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. 5 A). Importantly, the PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway was the only pathway commonly regulated by both CAY10444 treatment and S1PR3 knockdown (Fig. 5A). The PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway is essential for regulating cell survival, metastasis and apoptosis, thereby contributing to tumor progression [14–19]. Previous research has indicated that S1PR3 activates various pathways, including the PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway, by binding specifically to Gi [20].

Fig. 6.

S1PR3 inhibition suppressed OSCC cell growth via AKT signaling pathway in vivo. A–C The xenograft tumor model using S1PR3 knockdown or control CAL27 cells was established in the groin of nude mice. Volumes of xenograft tumors (A) were evaluated every 5 days. The tumors of each group were excised and photographed after 20 days. Tumor images (B) and weights (C) were then evaluated. D The translational levels of S1PR3, p-AKT, WEE1 and Ki67 in the xenograft tumors were analyzed through IHC staining. E–G The xenograft tumor models using S1PR3 knockdown and control CAL27 cells were established and randomly divided into treatment and non-treatment groups. SC79 was administered to the treatment group every 3 days at a concentration of 20 mg/kg, while the non-treatment group received an equivalent volume of DMSO. Volumes of xenograft tumors (E) were evaluated every 3 days. The tumors of each group were excised and photographed after 12 days. Tumor images (F) and weights (G) were then evaluated. H The translational levels of S1PR3, p-AKT, WEE1 and Ki67 in the xenograft tumors were analyzed through IHC staining. Data were presented as mean ± SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 μm

To further determine whether inhibiting S1PR3 expression in OSCC cells affects the PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway, we analyzed the phosphorylation levels of AKT in tumor cells after S1PR3 knockdown and antagonist treatment and protein levels of the involved molecules were measured via western blotting analysis. The data revealed that both S1PR3 knockdown and antagonist treatment inhibited AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, C). Therefore, it could be hypothesized that inhibiting S1PR3 might downregulate the abundance of WEE1 by the AKT signaling pathway. Thus, we further evaluated whether an AKT agonist could reverse the growth inhibition effect of targeting S1PR3 in OSCC cells. Based on western blotting results, SC79 was found to increase AKT phosphorylation levels (Supplementary Fig. 6 A). Moreover, the CCK8 assay showed that the AKT agonist SC79 partly mitigated the repressive effect of S1PR3 knockdown and antagonist treatment on OSCC cell growth (Fig. 5D, E). As shown in Fig. 5F, SC79 significantly upregulated WEE1 expression and CDC2 phosphorylation in S1PR3 antagonist-treated OSCC cells. Thus, these findings suggest that the AKT/WEE1/CDC2 axis mediates the growth inhibition effect of S1PR3 inhibition in OSCC cells.

S1PR3 inhibition suppresses OSCC cell growth via AKT signaling pathway in vivo

We established a cell line-derived xenograft model to validate the growth-inhibitory effect of targeting S1PR3 on OSCC cells. No notable adverse effects were detected in mice following injection with S1PR3 knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig. 7 A). Moreover, the injection of stable S1PR3 knockdown cells into mice led to a marked delay in tumor growth, with both tumor volume and weight substantially reduced (Fig. 6A–C).

Additionally, the effect of S1PR3 knockdown on expression of S1PR3, p-AKT, WEE1 and Ki67 was appraised in vivo using IHC staining. In alignment with in vitro results, expression of S1PR3, p-AKT and WEE1 were substantially decreased among mice injected with S1PR3 knockdown groups, and OSCC cell proliferation was inhibited (Fig. 6D). In summary, these findings indicate that S1PR3 knockdown inhibited OSCC cell expansion in vivo.

Furthermore, to determine whether targeting S1PR3 curbs OSCC cell growth in vivo via the AKT signaling pathway, mice with xenograft tumors after injection of S1PR3 knockdown cells and control CAL27 cells were further divided into drug treatment and non-treatment groups. SC79 was administered intraperitoneally to the treatment group, while the non-treatment group received an equivalent amount of DMSO. Consistent with previous experimental results, No notable adverse effects were detected in mice following injection with S1PR3 knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig. 7B). As shown in Fig. 6E–G, mice injected with stable S1PR3 knockdown cells showed significantly reduced tumor volume and weight. Notably, SC79 markedly attenuated tumor suppression induced by injection with S1PR3 knockdown cells.

In addition, we examined the expression of S1PR3, p-AKT, WEE1 and Ki67 in xenograft tumors from each group using IHC staining. The expression of p-AKT, WEE1 and Ki67 were markedly decreased among mice injected with S1PR3 knockdown cells, an effect which was reversed by treatment with SC79 (Fig. 6H). Thus, the results of in vivo experiments further demonstrate that S1PR3 promotes OSCC progression by regulating the AKT signaling pathway.

S1PR3 antagonist combined with cisplatin suppresses OSCC cells growth

Cisplatin (CDDP) is a widely used chemotherapeutic drug for OSCC treatment and exerts its antitumor effect by disrupting the structure and function of tumor cell DNA [21, 22]. Therefore, the impact of treatment with S1PR3 antagonist CAY10444 on the antitumor effects of CDDP in OSCC cells was evaluated. It was found that treatment with either CDDP or CAY10444 inhibited OSCC cell viability, and when used in combination, the inhibitory effect was further exacerbated (Fig. 7A, B). Moreover, using the EdU incorporation assay, it was further revealed that the combination of CDDP and CAY10444 significantly inhibited OSCC cell proliferation compared to their effect when employed alone (Fig. 7C, D). Additionally, the apoptosis assay and γ-H2 AX detection indicated that the combination of the S1PR3 antagonist and CDDP promotes apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 8 A) and enhances DNA damage (Supplementary Fig. 8B). Collectively, these data imply that combining CDDP with CAY10444 may result in enhanced therapeutic benefits.

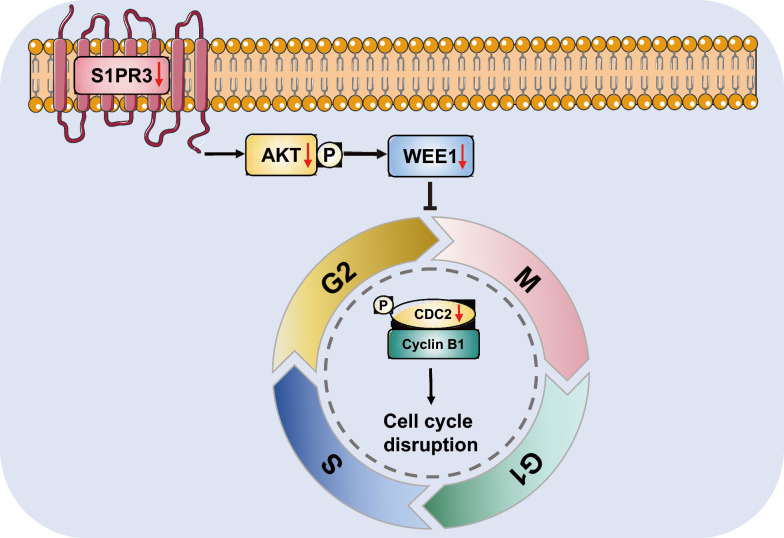

Fig. 8.

Diagram illustrating the S1PR3-mediated G2/M checkpoint failure

Discussion

It is known that S1PRs display differential expression patterns in different types of tumors, significantly influencing tumor progression. For instance, S1PR1 is upregulated in breast and ovarian cancers [23]. However, S1PR2 expression varies by tumor type, showing high levels in pancreatic cancer but low levels in gastric and colorectal cancers [24–26]. S1PR3 is upregulated in various tumors, including osteosarcoma, lung adenocarcinoma and breast cancer, being linked to poor prognosis in cancer patients [27–29]. A clinical study reported that S1PR4 expression levels are elevated in ER-negative breast cancer and show a negative correlation with disease-free survival [30]. Research indicates that the protein levels of S1PR5 are reduced in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [9]. However, the transcriptional and translational levels of S1PRs in OSCC have not been fully elucidated. In this study, S1PR1, S1PR3 and S1PR4 were found upregulated in most OSCC cells. Inhibition of S1PR3 may lead to compensatory activation of other receptors. The results of qPCR validation showed that S1PR1 was upregulated after inhibition of S1PR3 (Supplementary Fig. 9A). The combination of S1PR1 and S1PR3 antagonist enhanced the inhibitory effects on OSCC cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 9B). In addition, S1PR3 was the only S1PR correlated with unfavorable prognosis in HNSCC patients. In recent years, there has been rapid development in computational algorithms and bioinformatics [39–42]. The analysis of TCGA database showed that HNSCC patients exhibiting higher S1PR3 expression tended to be found in more advanced clinical stages of the disease and to exhibit worse OS, DSS and PFI. Additionally, this study found that high S1PR3 expression was associated with reduced sensitivity to afatinib, which is a second-line treatment for recurrent or metastatic HNSCC [12]. IPS and TIDE scores, key indicators of immunotherapy response, showed that the high S1PR3 expression group had significantly lower IPS, decreased tumor suppressor cell infiltration and higher TIDE scores. Moreover, T cell exclusion and CAF infiltration were significantly increased, while MSI scores were lower in this group. These findings suggested that patients with high S1PR3 expression have lower immunotherapy responsiveness. S1PR3 has been implicated in tumor progression, significantly affecting key biological processes in tumoral cells including proliferation, apoptosis, invasion and migration. The S1P/S1PR3 signaling pathway enhances aerobic glycolysis in osteosarcoma cells, suppressing apoptosis and promoting cell proliferation [27]. Additionally, it has been shown that high S1PR3 expression enhances invasion and migration in gastric carcinoma cells [10]. The findings of this study showed that the inhibition of S1PR3 significantly attenuated the proliferative capacity of OSCC and LSCC cells, which provided a more comprehensive understanding of the role of S1PR3 in head and neck cancers. Moreover, S1PR3 knockdown or antagonist-mediated inhibition suppressed OSCC cell proliferation by regulating the cell cycle, thereby exerting antitumor effects.

In order to investigate how S1PR3 regulates the OSCC cell cycle, a qPCR-based cell cycle array was employed to identify differentially expressed genes after treatment with the S1PR3 antagonist. WEE1 was identified as the most significantly downregulated gene. WEE1 encodes a tyrosine/threonine protein kinase that is crucial for regulating the cell cycle and repairing DNA damage. WEE1 primarily inhibits the activity of the G2/M phase regulatory protein CDC2 by phosphorylating it. Thus, downregulation of WEE1 can lead to G2/M checkpoint dysregulation, thereby affecting the cell cycle and further inhibiting tumor cell growth. A previous study described that inhibiting WEE1 expression via small interfering RNA (siRNA) increased the percentage of melanoma cells in the G2/M transition phase, thereby inhibiting cell proliferation [31]. Another study reported that adding a WEE1 inhibitor to drug-resistant breast cancer cells resulted in prolongation of the G2/M phase, which significantly inhibited tumor proliferation and induced apoptosis [32]. Similarly, the findings discussed herein showed that downregulation of WEE1 inhibited CDC2 phosphorylation in OSCC, leading to G2/M checkpoint failure and thereby affecting the cell cycle.

Gene clustering functional analysis was employed to identify signaling pathways impacted by CAY10444 treatment and S1PR3 knockdown, aiming to explore the molecular pathway by which targeting S1PR3 affects WEE1 expression. The results indicated that although CAY10444 treatment affected the PI3 K/AKT, PI3 K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways, the PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway was the only common pathway influenced by both treatments. Studies have reported that S1PR3 can bind to multiple Gα proteins, including Gi, Gq and G12/13, thus modulating signaling pathways such as AC/cAMP, Ras/ERK/AC, PI3 K/AKT, PLC/Ca2+ and Rho/ROCK [20]. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that targeting S1PR3 in OSCC can inhibit the activation of the PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway. The PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway has very important biological functions in tumors [33–35]. The results confirmed that inhibiting S1PR3 resulted in decreased AKT phosphorylation levels. In contrast, the AKT agonist SC79 restored the inhibitory effect on OSCC cell growth caused by S1PR3 inhibition both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, SC79 partially reversed the downregulation of WEE1 and p-CDC2 induced by targeting S1PR3. Collectively, these findings indicated that S1PR3 knockdown inhibited OSCC cell growth through modulating the AKT/WEE1 signaling pathway.

CDDP is a widely used chemotherapeutic agent, known for its strong antitumor activity against various cancers, and remains the first-line treatment for OSCC. In fact, adjuvant cisplatin therapy administered pre- or postoperatively enhanced the prognosis of OSCC patients [36, 37]. However, the extensive use of cisplatin in more recent years has contributed to the development of chemotherapy resistance, substantially reducing its effectiveness in OSCC treatment. Therefore, improving or reestablishing tumor cell sensitivity to cisplatin has become a critical research direction for enhancing chemotherapy efficacy. Furthermore, AKT activation has been closely tied to cisplatin resistance in lung cancer, with AKT1 driving the chemoresistance in tumor cells via the mTOR signaling pathway [38]. Our findings in this study showed that the combination of cisplatin and the S1PR3 antagonist enhanced the inhibition of the malignant biological behaviors of OSCC cells. Herein, S1PR3 antagonists were found to significantly enhance the suppressive influence of cisplatin on OSCC cell growth by increasing apoptosis induction and DNA damage, as well as regulating cell cycle. Additionally, the AKT signaling pathway was confirmed to function as a key downstream effector of S1PR3. Although our findings indicated that S1PR3 antagonist enhanced the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin on OSCC cells, the underlying mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. Moreover, the immunomodulatory roles of S1PR3 antagonist and its clinical therapeutic potential require further investigation and validation through additional experimental and clinical data.

Recent insights into S1PRs as therapeutic targets for enhancing antitumor drug sensitivity have garnered considerable attention. Fingolimod (FTY720), a modulator of S1PRs (including S1PR3), has shown efficacy in reversing trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer patients [43]. In colon cancer, FTY720 has been shown to enhance tumor cell chemosensitivity to doxorubicin and etoposide by modulating P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein 1 [44]. Therefore, S1PR3 could represent a potential therapeutic target to increase OSCC cell sensitivity to cisplatin.

Hence, the findings discussed herein revealed that targeting S1PR3 could regulate OSCC cell cycle by modulating the AKT/WEE1 signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting OSCC cell proliferation (Fig. 8). Furthermore, it was found that the specific S1PR3 antagonist CAY10444 exhibited a synergetic effect with cisplatin to inhibit OSCC cell growth, providing new insights into the clinical treatment of OSCC. Therefore, targeting the S1PR3/AKT/WEE1 signaling pathway might represent a novel therapeutic strategy for OSCC. However, the therapeutic effects of targeting S1PR3 require further clinical studies.

Conclusions

These findings reveal a critical role for S1PR3 in regulating OSCC cell cycle via the AKT/WEE1/CDC2 pathway, thus offering a basis for developing treatment strategies for OSCC patients.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology for their generous provision of HaCat and HNSCC cell lines. We acknowledge the excellent technical support supplied by the Department of Oral Pathology, Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. We appreciate the linguistic assistance supplied by TopEdit (www.topeditsci.com) during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Xinxia Zhou: Project administration; methodology; validation; formal analysis; data curation; writing – original draft; Jinghao Liu: Data curation; visualization; Xu Chen: Data curation; methodology; Xinyu Zhou: Resources; methodology; Beihui Xu: Methodology; formal analysis. Guifang Gan: Writing – review and editing; conceptualization; project administration; methodology; resources. Fuxiang Chen: Writing – review and editing; funding acquisition; supervision; conceptualization; resources.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81870762, 82203551), the National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2023YFB3210305), the Fundamental Research Program Funding of the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. JYJC202227), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. YG2022QN065), the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (20244Y0193) and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Yunxi project.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Human subjects: This study involving human subjects was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital (SH9H-2021-T428-2). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Animal studies: The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital (SH9H-2024-A2-1) and performed in compliance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals, minimizing animal suffering throughout the experimental procedures.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to submit the research article for publication.

Competing interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guifang Gan, Email: agan1992@126.com.

Fuxiang Chen, Email: chenfx@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VWY, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamoli A, Gosavi AS, Shirwadkar UP, Wangdale KV, Behera SK, Kurrey NK, et al. Overview of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Risk factors, mechanisms, and diagnostics. Oral Oncol. 2021;121: 105451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi AC, Day TA, Neville BW. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma–an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:401–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rezazadeh F, Andisheh-Tadbir A, Malek Mansouri Z, Khademi B, Bayat P, Sedarat H, et al. Evaluation of recurrence, mortality and treatment complications of oral squamous cell carcinoma in public health centers in Shiraz during 2010 to 2020. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdolahinia ED, Ahmadian S, Bohlouli S, Gharehbagh FJ, Jahandizi NG, Vahed SZ, et al. Effect of curcumin on the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line HN5. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2023;16:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Medeiros MC, The S, Bellile E, Russo N, Schmitd L, Danella E, et al. Salivary microbiome changes distinguish response to chemoradiotherapy in patients with oral cancer. Microbiome. 2023;11:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun J, Kihara Y, Jonnalagadda D, Blaho VA. Fingolimod: lessons learned and new opportunities for treating multiple sclerosis and other disorders. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;59:149–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Yuan Y, Lin W, Zhong H, Xu K, Qi X. Roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Li Y, Lei C, Tan Y, Yi G. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 signaling. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;519:32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogretmen B. Sphingolipid metabolism in cancer signalling and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:33–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Y, Ahn M-J, Chan A, Wang C-H, Kang J-H, Kim S-B, et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in Asian patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 3): an open-label, randomised phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1831–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luserna G, di Rorà A, Cerchione C, Martinelli G, Simonetti G. A WEE1 family business: regulation of mitosis, cancer progression, and therapeutic target. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Richmond A, Yan C. Immunomodulatory properties of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK/MEK/ERK inhibition augment response to immune checkpoint blockade in melanoma and triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortazavi M, Moosavi F, Martini M, Giovannetti E, Firuzi O. Prospects of targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in pancreatic cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176: 103749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ediriweera MK, Tennekoon KH, Samarakoon SR. Role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in ovarian cancer: Biological and therapeutic significance. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;59:147–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua H, Zhang H, Chen J, Wang J, Liu J, Jiang Y. Targeting Akt in cancer for precision therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunnery SE, Mayer IA. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hormone-positive breast cancer. Drugs. 2020;80:1685–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riquelme I, Pérez-Moreno P, Mora-Lagos B, Ili C, Brebi P, Roa JC. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as regulators of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in gastric carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao S, Peng K, Li C, Long Y, Yu Q. The role of sphingosine-1-phosphate in autophagy and related disorders. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang W, Chen L, Li R, Li J, Dou S, Ye L, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy with docetaxel versus cisplatin for high-risk oral squamous cell carcinoma: a randomized phase II trial with exploratory analysis of ITGB1 as a potential predictive biomarker. BMC Med. 2024;22:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anu B, Namitha NN, Harikumar KB. S1PR1 signaling in cancer: a current perspective. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2021;125:259–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar J, Aoki H, Wu R, Aoki M, Hylemon P, Zhou H, et al. Conjugated bile acids accelerate progression of pancreatic cancer metastasis via S1PR2 signaling in cholestasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:1630–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petti L, Rizzo G, Rubbino F, Elangovan S, Colombo P, Restelli S, et al. Unveiling role of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 as a brake of epithelial stem cell proliferation and a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita H, Kitayama J, Shida D, Yamaguchi H, Mori K, Osada M, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor expression profile in human gastric cancer cells: differential regulation on the migration and proliferation. J Surg Res. 2006;130:80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Y, Zhao S, Wang S, Pan X, Zhang Y, Xu J, et al. S1P/S1PR3 axis promotes aerobic glycolysis by YAP/c-MYC/PGAM1 axis in osteosarcoma. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:210–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao J, Liu J, Lee J-F, Zhang W, Kandouz M, VanHecke GC, et al. TGF-β/SMAD3 pathway stimulates sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor 3 expression: implication of sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor 3 in lung adenocarcinoma progression. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:27343–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Hind T, Lam BWS, Herr DR. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling induces SNAI2 expression to promote cell invasion in breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 2019;33:7180–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohotski J, Long JS, Orange C, Elsberger B, Mallon E, Doughty J, et al. Expression of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 4 and sphingosine kinase 1 is associated with outcome in oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1453–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Cai A, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Duan X, Men K. Treatment of melanoma by nano-conjugate-delivered Wee1 siRNA. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2021;18:3387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fallah Y, Demas DM, Jin L, He W, Shajahan-Haq AN. Targeting WEE1 inhibits growth of breast cancer cells that are resistant to endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors. Front Oncol. 2021;11: 681530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widyananda MH, Pratama SK, Samoedra RS, Sari FN, Kharisma VD, Ansori ANM, et al. Molecular docking study of sea urchin (Arbacia lixula) peptides as multi-target inhibitor for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) associated proteins. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res. 2021;9:484–96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scappaticcio L, Ansori ANM, Trimboli P. Editorial: Cancer-related hypercalcemia and potential treatments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1281731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Widyananda MH, Pratama SK, Ansori ANM, Antonius Y, Kharisma VD, Murtadlo AAA, et al. Quercetin as an anticancer candidate for glioblastoma multiforme by targeting AKT1, MMP9, ABCB1, and VEGFA: an in silico study. Karbala Int J Modern Sci. 2023;9(3):10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH, Saxman SB, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovács AF. Response to intraarterial induction chemotherapy: a prognostic parameter in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2006;28:678–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu L-Z, Zhou X-D, Qian G, Shi X, Fang J, Jiang B-H. AKT1 amplification regulates cisplatin resistance in human lung cancer cells through the mammalian target of rapamycin/p70S6K1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z, Qiu H, Letchmunan S, Deveci M, Abualigah L. Multi-view evidential c-means clustering with view-weight and feature-weight learning. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2025;498: 109135. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maiti B, Biswas S, Ezugwu AE-S, Bera UK, Alzahrani AI, Alblehai F, et al. Enhanced crayfish optimization algorithm with differential evolution’s mutation and crossover strategies for global optimization and engineering applications. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58:69. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biswas S, Singh G, Maiti B, Ezugwu AE-S, Saleem K, Smerat A, et al. Integrating differential evolution into gazelle optimization for advanced global optimization and engineering applications. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2025;434: 117588. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rateb R, Hadi AA, Tamanampudi VM, Abualigah L, Ezugwu AE, Alzahrani AI, et al. An optimal workflow scheduling in IoT-fog-cloud system for minimizing time and energy. Sci Rep. 2025;15:3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung W-P, Huang W-L, Liao W-A, Hung C-H, Chiang C-W, Cheung CHA, et al. FTY720 in resistant human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xing Y, Wang ZH, Ma DH, Han Y. FTY720 enhances chemosensitivity of colon cancer cells to doxorubicin and etoposide via the modulation of P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein 1. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:246–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.