Abstract

The Black Church has long been an institution of refuge, mobilization, and healing in Black or African American communities. While health promotion interventions have been implemented in the Black Church, little is known about ways to incorporate faith into colorectal cancer (CRC) screening messages. Using modified boot camp translation, a community-based approach, we met with 27 members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Atlanta, Georgia, for in-person and virtual sessions to co-create faith-based CRC screening messages and identify channels for sharing information within the church community. Examples of messages developed included “Faith over fear” and “Honor God by taking care of your body.” Identified dissemination channels included Sunday service, community events, and social media. Churches serve as key partners in delivering health information, as they are among the most trusted institutions within the Black or African American community.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening, Community engagement, Faith-based, Black or African American

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death in Black or African American people in the US (Giaquinto et al., 2022; US Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2023). Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Black or African American adults are about 20% more likely to get CRC and about 40% more likely to die from it (American Cancer Society, 2020; Siegel et al., 2020). Routine screening can substantially reduce CRC incidence and mortality; however, only an estimated 65% of Black or African American adults aged 50 and older are up to date with potentially life-saving CRC screening (Siegel et al., 2020). The disparities in CRC outcomes within the Black or African American community underscore the importance of CRC screening interventions. This project engaged African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Churches in the Atlanta, Georgia area to modify existing messaging and develop new messages to promote CRC screening, address barriers to care, increase screening intent among the AME Church communities, and develop local health-care system partnerships.

Recent market research findings from the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (NCCRT) and American Cancer Society (ACS) found that the majority of Black or African Americans identify as being somewhat religious (National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, n.d.). Those who are very religious place a “high level of trust in leaders of their faith-based institution” and report their faith influence health decisions (National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, n.d.). Furthermore, Black churches have historically served as not only spiritual spaces, but also have been important for civic activity, solidarity, and assist in educational and social needs for church and community members (Baskin et al., 2001; Eng et al., 1985; Jackson & Reddick, 1999; Mohamed et al., 2021).

As one of the most important and trusted institutions for Black or African Americans persons, churches and other religious organizations could expand the reach of health messaging as congregations include members across the socioeconomic spectrum (Baskin et al., 2001). The previous research demonstrates the success of church-based health interventions for Black or African American people. These interventions include spiritual and cultural perspectives to promote positive health behaviors and can cultivate genuine relationships central for community development (Brewer & Williams, 2019; Campbell et al., 2006; Friedman et al., 2019; Holt & Klem, 2005; Jackson & Reddick, 1999; Newlin et al., 2012).

For example, Friedman and colleagues assessed a culturally appropriate arts-based CRC education approach within a predominantly African American church in South Carolina. The theatrical production was found to be successful in improving CRC knowledge and motivating attendees to engage in CRC screening behavior changes (Friedman et al., 2019). Additionally, in partnership with an African American church, Holt and Klem used scripture and religious themes to develop an educational booklet to encourage breast cancer screening. While both spiritual and secular-based approaches were effective in breast cancer education, the authors report that using spiritual themes may be more effective (Holt & Klem, 2005). A study by Lumpkins and colleagues assessed pastor personal beliefs about CRC and their perspectives of religiously targeted CRC screening interventions using church-endorsed messages. Pastors agreed that the church could be used for community-based health promotional activities and as a marketer of CRC materials, in particular (Lumpkins et al., 2013).

Invited by an Atlanta-based AME Church, we established a collaborative initiative among the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research (CHR), American Cancer Society (ACS), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to develop culturally relevant CRC materials. We used boot camp translation (BCT), a validated participatory approach, to co-design messages and materials to motivate Black or African American parishioners to be screened for CRC (Norman et al., 2013). BCT has previously been used to develop patient-centered messaging around health topics such as depression and asthma, all of which have higher prevalence in Black or African American people (Ali et al., 2021; JHFE Health Literacy Boot Camp Translation Project, n.d.; Muvuka et al., 2020). This work represents first efforts to use this approach to engage Black or African American people in a church community to collaboratively create messages to increase CRC screening rates.

Methods

This quality improvement project received a non-research determination by the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Institutional Review Board. Due to the minimal risk of the BCT process, informed consent was waived.

Setting

The AME Church, founded in 1816, is the first African American denomination organized in the US. Its origins are in the Free African Society, a benevolent organization that held religious services and provided support for free Africans and their descendants in Philadelphia. The church’s mission is to minister to the social, spiritual, and physical development of all people (African Methodist Episcopal Church, n.d.; Lewis, 2018). The AME Church is a connectional church with an estimated 3 million members and more than 7000 churches in 20 Episcopal Districts covering the US and 38 other countries, on five continents (African Methodist Episcopal Church, n.d.). For this study, we recruited members from churches in the AME Church Atlanta East District. The churches in this District are located in eight counties in and around Atlanta and have membership ranging from 15 to over 8000 people. The in-person session was conducted at an AME Church in Stone Mountain, Georgia, in October 2022.

Boot Camp Translation (BCT)

BCT is a validated community-based participatory approach that identifies health-care priorities for community members, convenes partners to address priority issues, and translates dense scientific evidence and guidelines in a way that acknowledges and respects local culture and individual patient preference (Norman et al., 2013). Uniting community members, researchers, and medical experts, BCT is an iterative approach used to develop ideas, messages, and materials on a specific health topic. This process includes presentations by health experts and engaging discussions with community members. Generally, the goal of BCT is to answer two main questions: (1) “What do we need to say in our message to the community?” and (2) “How do we disseminate that message to the community?” BCT typically occurs through in-person meetings, short-focused teleconferences, and emails/postal mail totalling to approximately 20–25 h of participant time over 4–18 months (Norman et al., 2013).

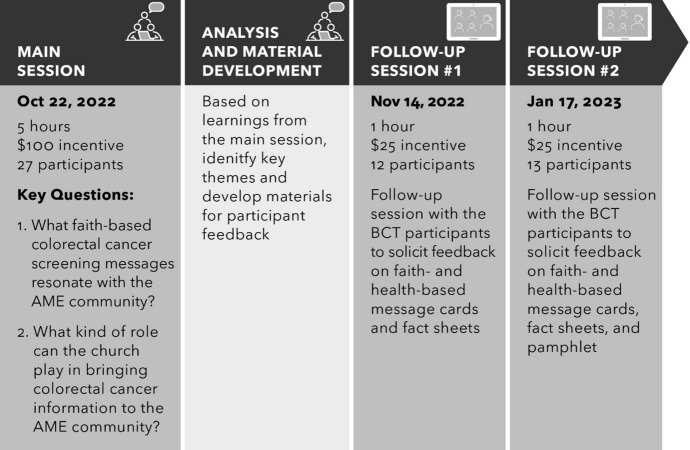

Our approach described here took place over a shorter time than the typical BCT process due to participant preferences and availability. In the spirit of BCT, we considered the environment in which this work is done to ensure that participants can be their authentic selves and can speak freely. In our adapted BCT process, we asked people to participate in a 1-day in-person session and two follow-up group virtual conference calls over 3 months. BCT activities occurred between October 22, 2022, and January 17, 2023. The BCT facilitators were experienced in facilitating patient engagement activities with diverse populations and had previously led other BCT sessions. For this project, BCT focused on eliciting input from AME Church congregants to (1) develop faith-based CRC screening messages that resonate with the AME Church community and (2) identify the church’s role in bringing CRC screening information to the AME Church community.

Study Procedures

Gathering Materials

To prepare for the in-person session, the team gathered existing materials and messages (i.e., videos, posters, flyers, and market-tested CRC screening messaging) from the NCCRT and ACS (Anyane-Yeboa et al., 2023; National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, n.d.). The market research found that preferred screening messages were relatable, direct, and concise, and included actionable next steps. The five core messaging themes included: prevention and early detention, silent disease, family history, screening options, and cancer facts related to Black or African American communities (Anyane-Yeboa et al., 2023; National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, n.d.).

Recruiting Participants

The study team initially met with AME Church leaders to listen and learn about the CRC health needs of the church community. Surveys were distributed to AME Church leaders and congregants (details below). These efforts helped foster a strong partnership and successful recruitment of participants. Recruitment involved a two-phase approach. First, the church clergy was asked to recruit parishioners for the in-person session, using a flyer developed for the project. Second, a study team member attended an in-person, District-wide meeting, organized by the AME Church Atlanta East District Leadership to meet and recruit interested parishioners in-person. Eligible participants were members (congregants and pastors) from six churches within the AME Atlanta East District, aged 45–75 years, and willing to participate in one 5 h in-person meeting and two follow-up video-conferencing calls.

In-person Session

The in-person session was held in the church sanctuary and fellowship hall. The morning session featured expert presentations by a national leader on CRC and screening, a local leader well-versed in barriers to screening and community resources, and a prominent church clergy person to discuss the church’s potential role in CRC education. In the afternoon, we held two interactive small-group sessions to create messages and identify dissemination methods. Messages were developed using the ACS NCCRT market-tested CRC screening messaging described above as a starting point. Participants received a $100 gift card as a token of appreciation for their time.

Follow-up Sessions

Two 1-h follow-up virtual sessions were held 3 weeks and 3 months later (Fig. 1). Follow-up sessions were held on November 14, 2022 (12 participants), and January 17, 2023 (13 participants). Participants received a $25 gift card for each follow-up session.

Fig. 1.

BCT process

Pre- and Post-BCT Survey Responses

Members of the study team developed short pre- and post-BCT surveys tailored to the specific aims of the project. The surveys included questions on participant demographics (i.e., age, sex, employment, education, insurance status, and income), CRC knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, barriers to CRC screening, and screening history. The self-administered confidential surveys were distributed to participants in paper format at the beginning and end of the in-person session. While similar to the pre-survey, the post-survey also included an evaluation of the session content and delivery and omitted the demographics questions. We report frequencies of participant screening history, beliefs and attitudes about CRC, barriers to screening, and session evaluation. Significance between changes in pre- and post-survey responses was tested using the McNemar test for paired proportions and paired sample t-tests, but none of the results were statistically significant.

Results

A total of 27 adults participated in the in-person session (17 women and 10 men). Nearly two-thirds were ages 45–64, and 85% were a high school graduate or higher (Table 1). Eighty-one percent lived in households with incomes $50,000 or greater; over one-half were employed, and nearly all (96%) had health-care insurance, primarily Medicare. See Table 1 for participant demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics

| Demographics | Percentage (%) (N= 27) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 63 |

| Age | |

| 45–54 | 26 |

| 55–64 | 37 |

| 65 + | 37 |

| Education | |

| High school graduate | 85 |

| College graduate | 52 |

| Annual household Income | |

| $50,000 or greater | 81 |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 52 |

| Health insurance | |

| Insured | 96 |

Key Messages

Based on participant feedback during the in-person session, we learned about favored key messages and dissemination channels (Table 2). Key messages were categorized under three main themes: (1) incorporating faith-based concepts into health messaging, (2) increasing CRC awareness and knowledge through personal connections, and (3) empowering self-care through community.

Table 2.

Faith-based colorectal cancer screening materials, messages, and dissemination channels

| Materials | Description | Key messages | Design and content | Dissemination channel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pamphlet | ||||

| Colorectal cancer is preventable | Tri-fold pamphlet |

- Incorporate faith-based messaging “Honor God by taking care of your body. Stop cancer by getting screened today.” - Explicitly call out “stopping” cancer - “Choosing faith over fear of screening.” |

- Incorporate the color purple to represent faith - Educate and inform with information about CRC screening - Add website with additional CRC information - Add specific CRC statistics related to Black or African Americans |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms |

| Fact sheets | ||||

| Colorectal Cancer Can Be Prevented + Your Faith, Your Health | Two-sided CRC information sheet |

- Incorporate faith-based messaging “Honor God by taking care of your body. Get screened for colorectal cancer.” - Educate with information about CRC screening - Incorporate key messages from Reverend Garland Higgins’s sermon |

- Create double-sided fact sheet with CRC information and faith messaging - Incorporate the color purple to represent faith - Add website with additional CRC information |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms |

| CRC Screening Options | CRC screening shared decision-making fact sheet | - Taking control of one’s own health |

- Incorporate the color purple to represent faith - Present information about CRC screening options in a clear and simple format - Add specific CRC statistics related to Black or African American person - Increasing awareness and knowledge of CRC screening |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailed w/annual FIT |

| Messages cards | ||||

| Faith Over Fear | Double-sided message card |

- Explicitly call out “stopping” cancer - Incorporate faith-based messaging created by participants: “Faith over fear.” |

- Use photographs representing prayer and community - Add website with additional CRC information - Share statistics that will speak to the African American population - Add specific actions people can do to help lower their risk |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| Honor God | Double-sided message card |

- Use faith-based messaging “Worship God with your whole health” - Incorporate key messages from the Reverend Garland Higgins’s sermon |

- Incorporate scripture into messaging - Educate and inform about CRC screening age - Add website with additional CRC information - Use a photograph that illustrates faith, hope, and life |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| Dear God | Double-sided message card | - Incorporate faith-based messaging “Dear God…” |

- Incorporate scripture into messaging - Use “family messaging” as a motivator to promote screening - Teach children about the power of prayer and importance of a healthy body at a young age - Add website with additional CRC information |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| I Need You to Survive | Double-sided message card | - Colorectal cancer can be prevented |

- Incorporate faith-based messaging by including lyrics from faith-based song - Educate and inform about CRC screening age - Use “family messaging” as a motivator to promote screening - Add website with additional CRC information - Use photographs representing younger families to align with new screening age |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| Ruth’s Story | Double-sided message card |

- Share your stories and knowledge to save lives - Early testing is important - Incorporate faith message “comfort and strength in [your] faith knowing that God is with you” |

- Focus on message that CRC screening is needed even when you do not have symptoms - Share personal stories with one’s community to reduce stigma and inspire action |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| Cynthia’s Story | Double-sided message card |

- Share your stories and knowledge to save lives - “Don’t let your family lose you too.” - Early testing is important - Colorectal cancer can be prevented |

- Use “family messaging” as a motivator to promote screening - Share personal stories with one’s community to reduce stigma and inspire action |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| Henry’s Story | Double-sided message card |

- Share your stories and knowledge to save lives - Make time to get screened – do not delay - Colorectal cancer can be prevented |

- Trust your body messaging - Sharing personal stories with one’s community to reduce stigma and inspire action - Use photograph representing people in manual labor or skilled trade occupations |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

| Tamika’s Story | Double-sided message card |

- Share your stories/knowledge to save lives - Choose faith over fear of screening - Early testing is important - Colorectal cancer can be prevented |

- Address perceived medical mistrust and fear using faith messaging - Share personal stories with one’s community to reduce stigma and inspire action |

- Sunday service - Church health fair - Community events - Clinic examination rooms - Mailer - Social media |

First, participants expressed the importance of incorporating faith-based words into health messaging. The prominent church clergy person who presented during the in-person session reinforced the connection between health and faith and spoke about honoring God by caring for your whole body. Samples of participant-created messages included:

Honor God by taking care of your body. Get screened for colorectal cancer today.

Faith over fear! Get screened for colorectal cancer today.

Your faith, your health. Get screened for colorectal cancer today.

Listen to the gospel’s call to live whole and healing lives. Get screened today.

Second, participants also shared the importance of increasing CRC awareness and knowledge through personal connections. Sharing personal stories about screening and cancer with church community members helps increase awareness, reduce stigma and fear around cancer, and inspire healthy actions. “We all have a platform to share our experiences, knowledge, [and] support each other.” “Any test that you take, there are several people who are afraid of taking it. We can help others get through the test as well.” Participant-inspired messages included:

Share your cancer story. It can save lives. Get screened today.

I need you to survive. Get screened for colorectal cancer today.

Finally, we learned that it is integral that messaging empowers people to take control of their colorectal health by relying on the strength of the community. During the in-person session, one of the pastors expressed, “There’s nothing we shouldn’t be able to talk about on a Sunday morning.” Church members agreed that their faith leaders can help the congregation overcome personal screening barriers by encouraging conversation about CRC. Many participants stated the importance of being able to say the word “cancer.” “Don’t be afraid of using the word cancer. Just say STOP CANCER” and “You’re not in it alone. We’re in it together.”

Key Dissemination Channels and Messengers

Favored dissemination channels within the church included Sunday service, print materials (e.g., flyers, pamphlets, and message cards) distributed at church, and digital materials (e.g., videos) shown during service. Furthermore, participants shared ideal community channels included cancer awareness events and social media platforms, including Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube. Participants agreed that trusted messengers for CRC screening included Black or African American men and women in positions of power, church leaders, fellow congregants, and cancer survivors. “The church plays an essential role in not only advocating and supporting health management but in embodying the gospel’s call to live whole and healing lives.”

Materials

Using the messages and themes inspired by BCT participants, our team co-created several materials to promote and increase CRC screening intent among AME Church communities (Table 2). We sought input on and continued refinement of all materials during the two follow-up virtual sessions, each with a subset of the participants from the in-person meeting.

Pre- and Post-BCT Survey Responses

Both the pre- and post-surveys had 100% response rates (n = 27). The participants provided information on demographic questions, as reported above.

Pre-survey responses showed that nearly all participants (93%) knew that CRC is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the US and that more than half of CRC deaths can be prevented by screening and early detection. Almost all participants (about 90%) noted that they were “very” familiar with a colonoscopy and stool test in the pre-survey. Familiarity with other screening options such as computed tomography (CT) colonography and stool DNA tests increased from 7% in the pre-survey to 33% in the post-survey; these percentages of participants reported that they were “very” familiar with each test.

Participants demonstrated improved understanding of who should be screened for CRC. In the post-survey, larger proportions of participants strongly disagreed with: “CRC is rare” (41% vs. 67%, p = 0.73); “CRC screening is just for men” (70% vs. 81%, p = 0.054); “You don’t need to get screened for CRC if you eat right and exercise” (52% vs. 81%, p = 0.128); “Only those with symptoms should be screened” (52% vs. 81%, p = 0.068); and “I don’t have a family history, so it is not important to get screened” (31% vs. 65%, p = 0.886). No pre–post survey differences were observed in responses to survey questions addressing attitudes about CRC screening. In both pre- and post-surveys, a similar number of participants agreed or strongly agreed that talking about “CRC is embarrassing” (59% vs. 52%, p = 0.55) and strongly agreed that the colonoscopy procedure “scares me” (54% vs. 50%, p = 0.84). See Fig. 2 for a summary of the pre- and post-survey results.

Fig. 2.

Pre- and Post-Survey Results Note: Changes in pre- to post-survey responses were not statistically significant. P-values are reported in the text

Participants who were not up to date on their CRC screening (n = 2) were asked to report potential barriers they might have to CRC screening. Barriers included procrastination, focusing on other medical problems, fear of a cancer diagnosis, unpleasant bowel preparation, and no family history of CRC.

For the session evaluation questions, on average, participants rated the session a 9.89 out of 10 for satisfaction (1–10 scale, where 1 = very unsatisfied and 10 = very satisfied). Eighty-nine percent of participants rated the session a ten, indicating that they were very satisfied. Most participants (74%) reported feeling comfortable sharing their opinions on CRC screening during the session. All participants “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the session helped them understand (1) the role the church can play in sharing CRC information and (2) the importance of developing the right messages and methods for sharing CRC information.

Discussion

We used a modified BCT approach to incorporate participant feedback and create culturally appropriate and locally relevant faith-based CRC screening messages and materials. In addition, we also identified appropriate channels for sharing information within the AME Church community. We found that participants desired CRC screening messages that (1) incorporated faith-based concepts, (2) increased CRC knowledge and awareness through personal connections, and/or (3) empowered people to take control of their colorectal health through the strength of their community. Participants preferred dissemination channels within the church that included print materials (e.g., flyers, pamphlets, and message cards) distributed at church and digital materials (e.g., videos) shown during the Sunday church service. Favored community channels included cancer awareness events and social media platforms. Based on this input, the study team created a set of print and digital materials designed to raise awareness about CRC screening to empower parishioners to get screened.

The BCT process allowed us to engage participants in translating health information into ideas, messages, and materials that are understandable and meaningful to community members. BCT is a flexible and adaptable process intended to build community-based solutions to address local health problems and concerns. When possible and desired, the process builds upon existing resources and community assets.

Empowering participants in a given health topic is a key goal of BCT. To that end, our findings from pre- and post-surveys showed marked improvements in CRC knowledge and awareness; however, statistical significance was not reached given the small sample size. Additionally, the responses indicated strong satisfaction of the BCT process and content. Furthermore, knowledge of CRC screening importance and screening options increased and incorrectly answered questions in the pre-surveys were later marked correctly in the post-surveys. One participant stated, “The session was informative, and speakers were educated on various subject matters. The literature was presented in a laymen’s term which I fully understood.” Moreover, post-survey results indicated that every participant agreed or strongly agreed that the church plays an important role in sharing CRC information with congregants and their communities.

This study contributes to the growing research on partnering with Black or African American churches to expand reach of cancer education. Previous cancer-based health interventions found that partnering with Black or African American churches adds trust and credibility to research, resulting in church-sponsored engagement and recruitment of participants, educational benefits, and the integration of health promotion activities into church operations (Knott et al., 2022; McNeill et al., 2018; Mitchell-Beren et al., 1989; Slade et al., 2018). Our findings showed that the AME Church members favored this process, preferring that CRC materials include faith-based messaging and are distributed through the church. Given that churches are among the most trusted institutions within the Black or African American community, messages and materials delivered through churches have the potential to reach a large population of adults needing CRC screening.

A key strength of our study was the partnership between the AME Church and the study team. One of the study team partners is an active member of the church where the BCT in-person session was conducted and, thus, acted as the church champion to bridge the AME Church community and external research partners. The church champion’s expertise helped us to understand local values which was imperative in ensuring the BCT process reflected the community’s culture and priorities and in building trust in the partnership. Moreover, the church champion’s knowledge of local partners helped us identify expert presenters for the in-person session. The champion’s familiarity with the church’s physical space allowed us to use meeting spaces that eased the integration of the BCT methods while also creating a comfortable and engaging atmosphere for the participants. Additionally, a separate study team partner visited the church during an AME Church District-wide meeting to help recruit participants and later acted as the main contact for the recruitment process and the BCT sessions. This helped build strong rapport with the participants which may have helped with participant engagement, retention, and overall satisfaction of the BCT process.

Next Steps

Based on the BCT findings, the study team developed a set of print materials (i.e., fact sheets, pamphlets, and message cards) that churches can distribute in person after services or through digital channels including social media. Digital materials feature a series of short videos showcasing narratives from CRC cancer survivors; a series of short videos emphasizing updated CRC screening guidelines and the relatively high risk of the disease faced by Black or African American persons; and a 30–60 s video on the integration of faith and health delivered by the reverend of the church. The AME Church also plans to support a District-wide CRC Awareness Sunday during CRC Awareness Month. All churches in this District will participate with the goal of expanding this work to all 600 churches in the 6th Episcopal District that covers all of Georgia, and over time potentially across the full connection (7000 + churches). Additionally, the ACS NCCRT created a guide on how to develop and tailor CRC materials using community engagement approaches, such as BCT (American Cancer Society National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, n.d.).

An extension of this project is underway to continue engagement with the AME Church in the Atlanta, Georgia area to promote CRC screening by strengthening hospital system linkages and other key community partnerships through a Community Action Plan (CAP). A CAP summit occurred on July 29, 2023, in Stone Mountain, Georgia, at the Antioch AME Church. The summit convened church representatives from the Atlanta region, hospital and health systems, and broader community partners including the Georgia Center for Oncology Research and Education, the Georgia Cancer Control Consortium, and the Georgia State House of Representatives. ACS will continue assisting in the CAP implementation. An evaluation was recently completed to assess the number of people reached, new partnerships between the church and the community, and increases in CRC knowledge and intent to screen.

Limitations

Our study had a few limitations. First, the small sample size, though typical of community participatory research approaches, resulted in limited power to detect a knowledge difference in pre- and post-surveys. Second, the participants were limited to AME Church parishioners within the Atlanta region and represented a mostly middle class, mostly insured, population with a high screening prevalence. This may raise concerns about generalizability; however, it is important to emphasize that BCT is not focused on generalizable findings, but rather those specific to the participants’ community. Future BCT work could focus on geographic areas that may serve other faith communities and those of lower socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

Churches can serve as key partners in delivering health information, as they are among the most trusted institutions within the Black or African American community. Using a modified BCT community-focused approach, we incorporated participant feedback to create culturally appropriate and locally relevant faith-based CRC screening messages and materials, and we identified appropriate channels for sharing information within the AME Church community.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the African Methodist Episcopal Church for their participation in and support of this work. In addition, the authors extend their appreciation to Dr. Lisa Richardson, Ms. Denise Ballard, and Reverend Garland Higgins, for delivering expert presentations on colorectal cancer and screening, local barriers to screening and community resources, and the connection between health and faith, respectively.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Jamie Thompson, Priyanka Gautom, and Jennifer Rivelli. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jamie Thompson, and all authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Information reported in this paper was supported by the American Cancer Society, through a cooperative agreement funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the American Cancer Society or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Gloria Coronado served as a Scientific Advisor on a contract through the Center for Health Research for Exact Sciences from 2020 to 2022 served as Principal Investigator on a contract through the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research funded by Guardant Health that is assessing adherence to a commercially available blood test for colorectal cancer from 2021 to 2023. Nikki Hayes is a Trustee (an officer of the church) at Antioch African Methodist Episcopal Church. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This quality improvement project received a non-research determination by the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Institutional Review Board. Due to the minimal risk of the BCT process, informed consent was waived. (This is noted in the manuscript.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ali, N. M., Combs, R. M., Kakar, R. M., Muvuka, B., & Porter, J. (2021). Promoting interdisciplinary, participatory approaches to address childhood asthma disparities in an urban black community. Family & Community Health,44(1), 32–42. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- African Methodist Episcopal Church. (n.d.). AME Church. Retrieved October 23, 2023, from https://www.ame-church.com/

- American Cancer Society. (2020). Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2020–2022. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf

- American Cancer Society National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. (n.d.). Tailoring Colorectal Cancer Screening Messaging: A Practical Coalition Guide. https://nccrt.org/resource/tailoring-colorectal-cancer-screening-messaging-a-practical-coalition-guide/

- Anyane-Yeboa, A., Aubertine, M., Parker, A., Sylvester, K., Levell, C., Bell, E., Emmons, K. M., & May, F. P. (2023). Use of a mixed-methods approach to develop a guidebook with messaging to encourage colorectal cancer screening among Black individuals 45 and older. Cancer Medicine,12(18), 19047–19056. 10.1002/cam4.6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, M. L., Resnicow, K., & Campbell, M. K. (2001). Conducting health interventions in black churches: A model for building effective partnerships. Ethnicity & Disease,11(4), 823–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, L. C., & Williams, D. R. (2019). We’ve come this far by faith: The role of the black church in public health. American Journal of Public Health,109(3), 385–386. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M. K., Hudson, M. A., Resnicow, K., Blakeney, N., Paxton, A., & Baskin, M. (2006). Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health,28(1), 213–234. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng, E., Hatch, J., & Callan, A. (1985). Institutionalizing social support through the church and into the community. Health Education Quarterly,12(1), 81–92. 10.1177/109019818501200107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, D. B., Adams, S. A., Brandt, H. M., Heiney, S. P., Hébert, J. R., Ureda, J. R., Seel, J. S., Schrock, C. S., Mathias, W., Clark-Armstead, V., Dees, R. V., & Oliver, R. P. (2019). Rise up, get tested, and live: An arts-based colorectal cancer educational program in a faith-based setting. Journal of Cancer Education,34(3), 550–555. 10.1007/s13187-018-1340-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaquinto, A. N., Miller, K. D., Tossas, K. Y., Winn, R. A., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2022). Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,72(3), 202–229. 10.3322/caac.21718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, C. L., & Klem, P. R. (2005). As you go, spread the word: Spiritually based breast cancer education for African American women. Gynecologic Oncology,99(3), S141–S142. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R. S., & Reddick, B. (1999). The African American church and university partnerships: Establishing lasting collaborations. Health Education & Behavior: THe Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education,26(5), 663–674. 10.1177/109019819902600507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JHFE Health Literacy Boot Camp Translation Project. (n.d.). University of Louisville School of Public Health & Information Sciences. Retrieved June 19, 2023, from https://louisville.edu/sphis/departments/cik/projects/health-literacy-projects/projects/jewish-heritage-fund-for-excellence-jhfe-health-literacy-boot-camp-translation-project/jhfe-health-literacy-boot-camp-translation-project

- Knott, C. L., Chen, C., Bowie, J. V., Mullins, C. D., Slade, J. L., Woodard, N., Robinson-Shaneman, B.-J.R., Okwara, L., Huq, M. R., Williams, R., & He, X. (2022). Cluster-randomized trial comparing organizationally tailored versus standard approach for integrating an evidence-based cancer control intervention into African American churches. Translational Behavioral Medicine,12(5), 673–682. 10.1093/tbm/ibab088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, F. (2018). The African Methodist Episcopal Church. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/first-black-denomination-in-the-us-45157

- Lumpkins, C. Y., Coffey, C. R., Daley, C. M., & Greiner, K. A. (2013). Employing the church as a marketer of cancer prevention. Family & Community Health. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31829159ed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, L. H., Reitzel, L. R., Escoto, K. H., Roberson, C. L., Nguyen, N., Vidrine, J. I., Strong, L. L., & Wetter, D. W. (2018). Engaging black churches to address cancer health disparities: Project church. Frontiers in Public Health,6, 191. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Beren, M. E., Dodds, M. E., Choi, K. L., & Waskerwitz, T. R. (1989). A colorectal cancer prevention, screening, and evaluation program in community black churches. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,39(2), 115–118. 10.3322/canjclin.39.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, B., Cox, K., Diamant, J., & Gecewicz, C. (2021, February 16). Faith and Religion Among Black Americans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/02/16/faith-among-black-americans/

- Muvuka, B., Combs, R. M., Ali, N. M., Scott, H., & Williams, M. T. (2020). Depression is real: Developing a health communication campaign in an urban African American community. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action,14(2), 161–172. 10.1353/cpr.2020.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin, K., Dyess, S. M., Allard, E., Chase, S., & Melkus, G. D. (2012). A methodological review of faith-based health promotion literature: Advancing the science to expand delivery of diabetes education to Black Americans. Journal of Religion and Health,51(4), 1075–1097. 10.1007/s10943-011-9481-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, N., Bennett, C., Cowart, S., Felzien, M., Flores, M., Flores, R., Haynes, C., Hernandez, M., Rodriquez, M. P., Sanchez, N., Sanchez, S., Winkelman, K., Winkelman, S., Zittleman, L., & Westfall, J. M. (2013). Boot camp translation: A method for building a community of solution. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM,26(3), 254–263. 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.120253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. (n.d.). 2022 Messaging Guidebook for Black and African American People: Messages to Motivate for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Retrieved October 25, 2024, from https://nccrt.org/resource/2022-messaging-guidebook-black-african-american-people/

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Sauer, A. G., Fedewa, S. A., Butterly, L. F., Anderson, J. C., Cercek, A., Smith, R. A., & Jemal, A. (2020). Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,70(3), 145–164. 10.3322/caac.21601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, J. L., Holt, C. L., Bowie, J., Scheirer, M. A., Toussaint, E., Saunders, D. R., Savoy, A., Carter, R. L., & Santos, S. L. (2018). Recruitment of African American Churches to participate in cancer early detection interventions: a community perspective. Journal of Religion and Health,57(2), 751–761. 10.1007/s10943-018-0586-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. (2023, November). United States Cancer Statistics: Data Visualizations. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz