Abstract

Objective

In this study, we piloted the use of continuous 24-hour blood pressure (BP) monitoring in postpartum patients with preeclampsia with severe features.

Study Design

We measured continuous BP for up to 24 hours using finger plethysmography. We also used an oscillometric device to measure brachial BP per usual clinical protocol (intermittent BP) during the same monitoring period. Using a paired t-test, we compared mean BP values assessed using intermittent and continuous methods, and using McNemar’s test, we compared the proportion of patients with sustained severe-range BP using each BP measurement method.

Results

A total of 25 patients were included in this study. There was no difference in mean systolic BP (SBP) and mean arterial pressure between intermittent and continuous BP measurements. Intermittently recorded mean diastolic BP (DBP) was significantly higher than continuously recorded DBP. Eleven participants (44%) had sustained SBP ≥160 mmHg using continuous monitoring compared with two using intermittent monitoring (p = 0.003). Of these 11 participants, 3 (37%) also recorded sustained DBP ≥110 mmHg using continuous monitoring compared with none using intermittent monitoring.

Conclusion

Continuous BP monitoring is a feasible and reliable method for detecting sustained severe-range BP in postpartum patients receiving treatment for preeclampsia with severe features.

Keywords: postpartum, blood pressure, hypertension, preeclampsia, monitoring

In patients presenting with preeclampsia with severe features, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends periodic blood pressure (BP) measurements using an oscillometric device, with frequency of monitoring ranging from every 10 minutes to an hour based on symptom acuity.1–3 Continuous noninvasive arterial BP monitoring using finger pulse wave analysis has emerged as a promising modality for hemodynamic monitoring of pregnant patients, including those with preeclampsia with severe features.4,5 However, the utility of continuous over intermittent BP monitoring for detecting transient hypertension among preeclampsia patients is not well established. In this study, we piloted the use of continuous noninvasive BP monitoring in postpartum patients with preeclampsia with severe features and compared BP measurements derived from continuous BP monitoring and standard intermittent BP monitoring within the same patient cohort. We hypothesized that continuous monitoring would detect more episodes of sustained severe-range hypertension compared with intermittent monitoring.

Study Design

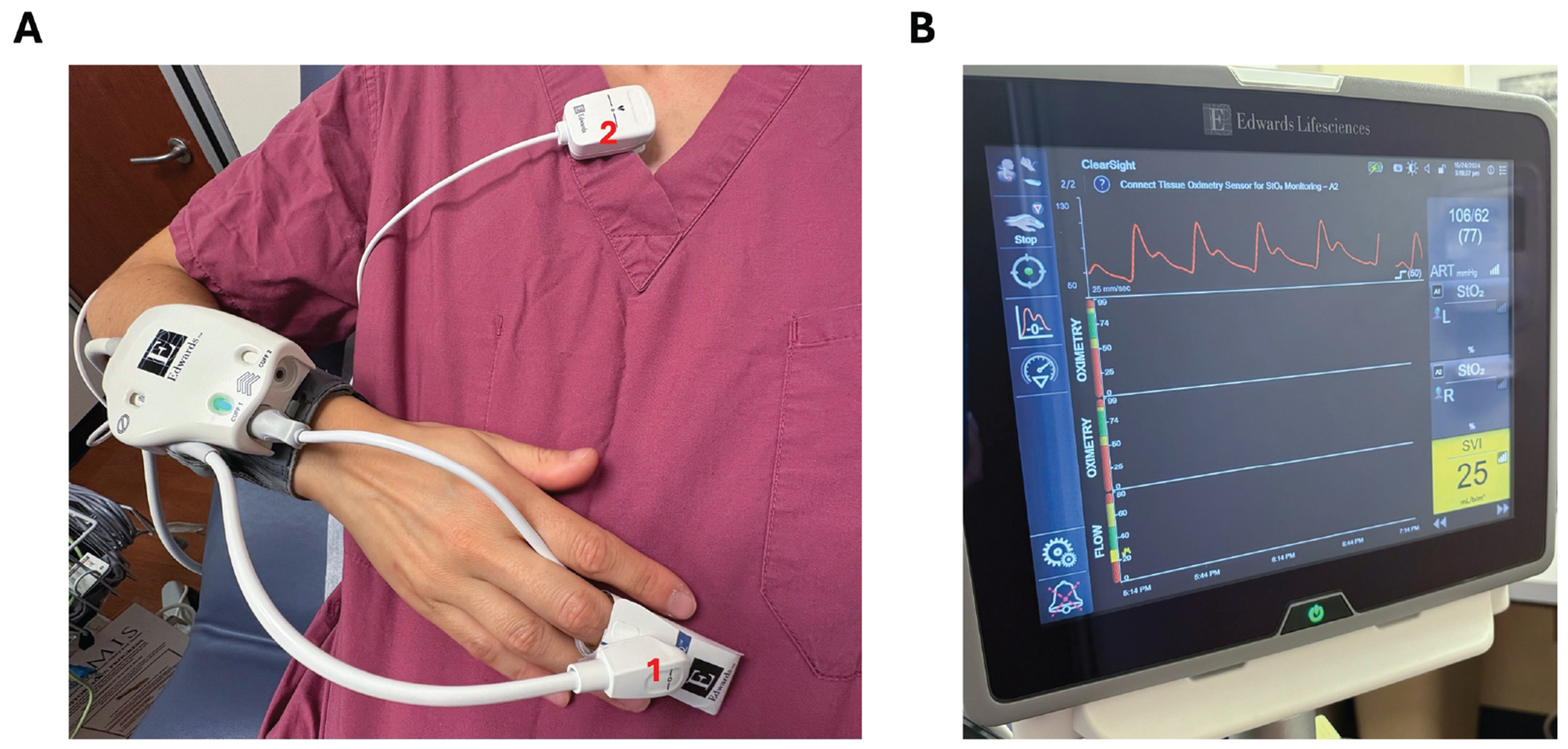

This is a retrospective analysis of preliminary data from a prospective pilot study of intensive systemic and cerebral hemodynamic monitoring in postpartum preeclampsia (clinicaltrials.gov NCT05726279). Eligible patients were admitted to Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC), a tertiary academic medical center, within 6 weeks after delivery and received treatment for preeclampsia with select severe features, defined as severe-range BP (systolic BP [SBP] ≥160mm Hg or diastolic BP [DBP] ≥110mm Hg), or unrelenting headache with SBP ≥140mm Hg or DBP ≥90mm Hg. All patients included in this analysis received standard guideline-based treatment from their primary clinical team, including BP-lowering medications based on intermittent arm cuff measurements. We measured continuous BP for up to 24 hours using finger plethysmography (ClearSight or Acumen IQ cuff with Hemosphere bedside monitor, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA; Fig. 1). We recorded brachial BP via an oscillometric device at 4- to 8-hour intervals during the monitoring period and collected all oscillometric BP values recorded by the clinical team during the monitoring period. We compared mean SBP, DBP, and mean arterial pressure (MAP) over the study period, measured in the same participants with continuous or intermittent BP monitoring, using a paired t-test. We compared median SBP, DBP, and MAP between both monitoring methods using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Using McNemar’s test, we compared the proportion of participants identified to have sustained severe-range BP using each method. We defined sustained severe-range BP as multiple measurements of SBP ≥160mm Hg or DBP ≥110mm Hg over at least 15 minutes for continuous monitoring and two measurements at least 15 minutes apart for intermittent monitoring. All arm cuff measurements recorded by the research and clinical teams were included in these analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA/SE (version 16.1, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). The study was approved by the CUIMC Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Photo of finger plethysmography device used in the study. (A) demonstrates proper finger plethysmography cuff placement. We utilized Edwards Lifesciences ClearSight or Acumen IQ cuff. The finger cuff is placed between the proximal interphalangeal joint and the distal interphalangeal joint, on any of the second to fourth phalanges. In this demonstration, the cuff is placed on the third phalange. The cuff is then connected to the white wristband device, which communicates the data to the Hemosphere bedside monitor (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA). The small white hook (labeled 1 in [A]) and the larger white clip (labeled 2 in [A]) are zeroed. The small white hook (1) is then hooked onto the finger plethysmography cuff while the large white clip (2) is clipped to the patient’s gown at heart level. (B) demonstrates the blood pressure waveform that appears on the HemoSphere bedside monitor.

Results

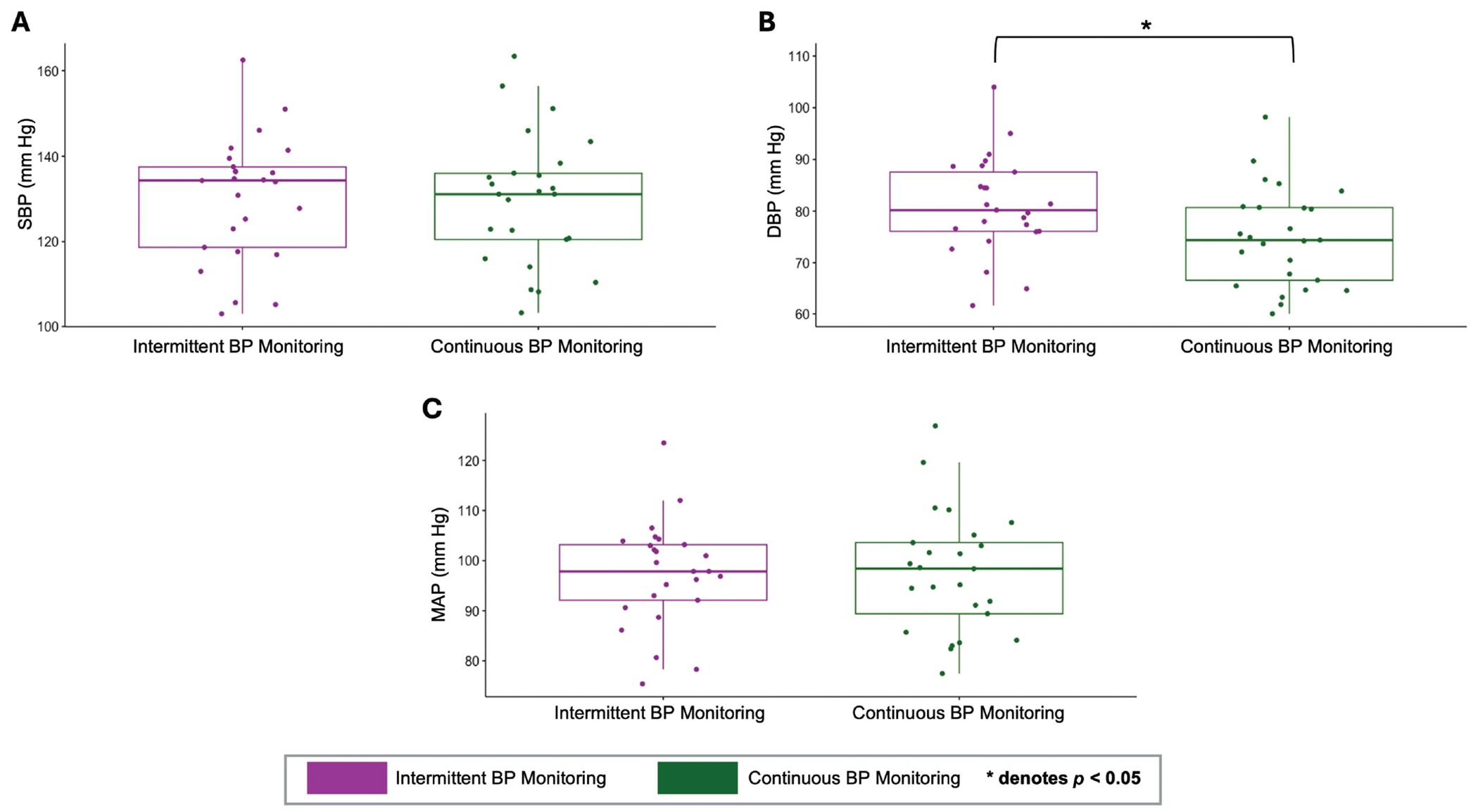

A total of 25 participants were included in the analysis. Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The participants were connected to the study monitor for a median of 9.7 hours (interquartile range [IQR] 4.6–20.1). Intermittent BP measurements were recorded by the clinical team a median of 7 (IQR 2–12) times throughout the study monitoring period. An example of continuous versus intermittent data collection in one participant can be found in Fig. 2. Between the intermittent BP and continuous BP measurements, there was no statistically significant difference in mean SBP (mean SBP 130.1 and 129.7, respectively; p = 0.853; Fig. 3A) and mean MAP (mean MAP 97.4 and 97.6, respectively; p = 0.928; Fig. 3C). Intermittently recorded mean DBP was higher than continuously recorded mean DBP values (81.01 vs. 74.9, p = 0.002; Fig. 3B). Eleven (44%) participants had sustained SBP ≥160mm Hg using continuous monitoring compared with 2 (8%) using intermittent BP monitoring (p = 0.003). Of the 11 participants with sustained severe-range SBP by continuous monitoring, 3 (27%) also had recorded sustained DBP ≥110mm Hg using continuous monitoring. none of these sustained severe-range DBP elevations were detected using intermittent monitoring.

Table 1.

Characteristics of postpartum individuals with preeclampsia with severe features (n = 25)

| Demographics | |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 34 (5) |

| Self-identified race/ethnicity (n, %) | |

| White | 6 (24) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5 (20) |

| Hispanic | 14 (56) |

| Medical comorbidities | |

| Pre-gravida obesity (n, %) | 11 (44) |

| Chronic hypertension (n, %) | 12 (48) |

| History of migraine headache (n, %) | 14 (56) |

| Pregnancy characteristics | |

| Primiparous (n, %) | 11 (44) |

| Gestational age at delivery in weeks (median, IQR) | 37.1 (35.4–39) |

| Days postpartum at the time of study enrollment (median, IQR) | 5.5 (2.5–8.6) |

| Preterm delivery (before 37 weeks; n, %) | 11 (44) |

| Fetal growth restriction (n, %) | 5 (20) |

| Gestational hypertension (n, %) | 5 (20) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage (n, %) | 5 (20) |

| Delivery type (n, %) | |

| Vaginal delivery | 11 (44) |

| Cesarean section | 14 (56) |

| Any adverse pregnancy outcome in a prior pregnancy (n, %) | |

| Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | 7 (28) |

| Preterm delivery | 5 (20) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; N, number; SD, standard deviation.

Fetal growth restriction is defined as an estimated fetal weight <10th percentile. Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy is defined as the presence of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia with or without severe features. Pre-gravida obesity is defined as obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2) during the first trimester of the initial prenatal appointment.

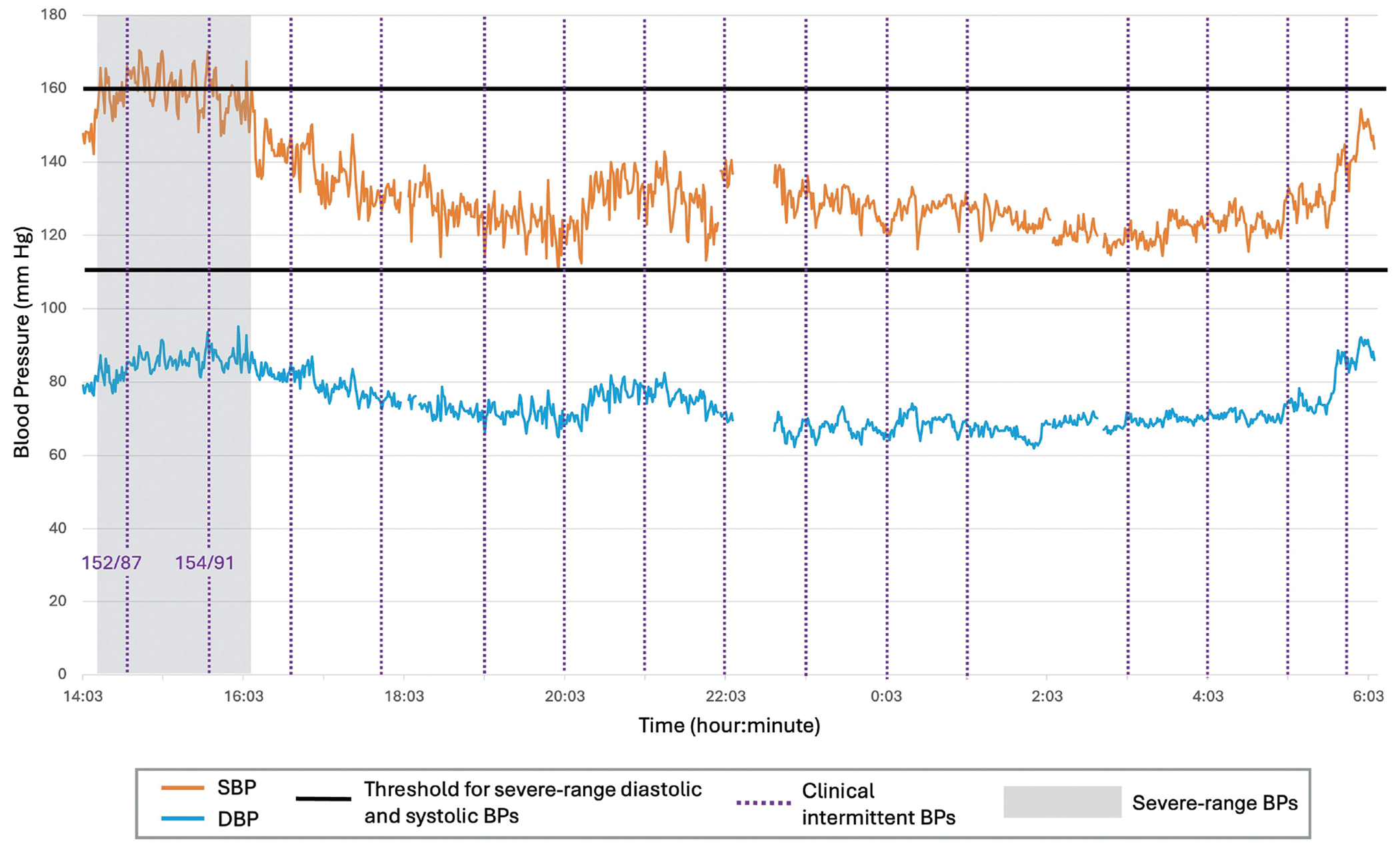

Fig. 2.

Example of participant blood pressure time trend. Time trend of continuous SBP and DBP, collected via finger plethysmography, over 16.1 hours in a postpartum patient actively receiving treatment for preeclampsia with severe features. Intermittently collected clinical BPs are denoted by the purple vertical dotted lines. Severe-range BP thresholds, defined as SBP ≥160mm Hg and DBP ≥110mm Hg, are denoted by bold horizontal lines. The patient’s sustained severe-range BPs, denoted by the gray box, occurred over 1.9 hours. Sustained severe-range BP was detected only by continuous SBP measurement. Intermittent BPs during the period of sustained severe-range BPs are indicated in the purple text with the format of SBP/DBP. BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; mm Hg, millimeters mercury; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Fig. 3.

Boxplot of blood pressures measured by intermittent versus continuous BP monitoring. Boxplot of BPs measured by continuous versus intermittent BP monitoring. BPs between groups were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. There was no significant difference in median SBP and MAP (A, C). In (B), there is a significant difference between intermittently and continuously measured DBP, defined as p-value < 0.05 (denoted by asterisk). BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; mm Hg, millimeters mercury; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Conclusion

We found that with continuous BP monitoring, nearly half of the patients being treated for postpartum preeclampsia with severe features had sustained severe-range BPs, of whom >80% were not detected with standard-of-care intermittent BP monitoring. This was not explained by differences in measured BPs, as both methods yielded similar results, with mean DBP slightly lower using continuous BP monitoring. Continuous BP monitoring is feasible and may be a reliable and superior method for detecting sustained severe-range BP in postpartum patients receiving treatment for preeclampsia with severe features. Future research should investigate whether the use of continuous BP monitoring for the management of preeclampsia with severe features improves maternal outcomes.

Key Points.

Postpartum continuous BP monitoring is feasible.

Continuous BP detects more sustained severe BP.

Continuous BP may be a reliable BP method.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Development (R21HD110992). N.P. is supported by the NIH/NINDS (K23NS110980).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Findings were presented as a poster for the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists’ 14th Annual Clinical Meeting in Denver, CO, September 7–11, 2024.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135(06):e237–e260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Safe Motherhood Initiative: Severe Hypertension. Accessed July 2, 2024 at: https://www.acog.org/community/districts-and-sections/district-ii/programs-and-resources/safe-motherhood-initiative/severe-hypertension

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 623: Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(02):521–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ackerman-Banks CM, Bhinder J, Eder M, et al. Continuous non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring in early onset severe pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 2023;34:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akkermans J, Diepeveen M, Ganzevoort W, van Montfrans GA, Westerhof BE, Wolf H. Continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, a validation study of Nexfin in a pregnant population. Hypertens Pregnancy 2009;28(02):230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]