Abstract

Background

In addressing health disparities, it is crucial to train doctors who can understand the social contexts of their patients. While experiential learning has been shown to enhance medical students’ understanding of Social Determinants of Health (SDH), few studies have examined its impact on students’ cognitive, emotional, and personal growth. This study aims to explore how experiential learning influences medical students’ understanding of SDH and fosters growth in cognition, emotion, and social responsibility.

Methods

Since 2015, an 8-week elective course at Juntendo University School of Medicine has aimed to help third-year students understand SDH through direct engagement with marginalized groups. Using a constructivist thematic analysis approach, we analyzed reports from 33 students and collaborative videos from 2015 to 2021.

Results

The analysis revealed five key themes: (1) Awareness of social issues, (2) Changes in personal perspectives, (3) A deeper understanding of SDH, (4) Exploration of future roles and actions, and (5) Personal growth through experiential learning and reflection.

Conclusion

Experiential learning led to significant emotional and cognitive shifts, enhancing students’ understanding of how social factors affect health and strengthening their sense of social responsibility. However, students also expressed complex emotional reactions to social inequalities. Future research should explore how to convert these insights into long-term behavioral changes and enhance the integration of reflection and collaborative learning in medical education.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, Constructivist theory, Thematic analysis, Kolb’s experiential learning theory

Background

Health is not determined solely by biological factors such as genes but is also influenced by socio-economic factors such as the individual’s income, family situation, and connections with friends and acquaintances; and social factors such as the environment, including social relationships in the workplace and community. Social Determinants of Health(SDH) are most responsible for health inequities [1]. In today’s era of inequality, healthcare providers must identify social determinants that may adversely affect patients; help them access available social resources, and address structural factors that contribute to health disparities [2, 3]. However, most healthcare professionals do not routinely identify or address the social needs of their patients in clinical practice [4]. Reasons for this failure to identify social needs include a lack of opportunity to understand their importance and to identify the various community resources available for problem-solving [5]. Medical educators should therefore provide opportunities for medical students to learn about SDH based on the integration of clinical and social science knowledge and perspectives from other professions so that they can include it as one aspect of their future practice.

In Japan, the importance of SDH education in medical education has also been recognized. The 2016 version of the Model Core Curriculum for Medical Education set a modest goal of ‘being able to outline SDH’ [6]. However, the goal in the 2022 version was revised to ‘appropriately identifying the social issues underlying health problems and actively initiating measures to address them’ [7]. Many studies have shown that experiential learning methods can effectively enhance medical students’ understanding of social determinants of health (SDH). By placing students in real community settings and having them interact directly with marginalized and socially disadvantaged groups, students can gain a deeper understanding of the social roots of health [8, 9]. For instance, a study on medical students learning about SDH in community-based courses demonstrated that students significantly improved their sensitivity to and understanding of social determinants of health through personal experiences interacting with community members [9]. However, despite existing research exploring how medical students learn about SDH in the community, the current literature still lacks an in-depth exploration of medical students’ personal growth during the learning process, as well as their cognitive and emotional changes through experiential learning [10].

This study aims to explore the transformation medical students undergo in understanding the social determinants of health after participating in social practice and experiential learning of health’s social determinants, as well as how they achieve personal growth in cognition, emotion, and social responsibility, to verify the effectiveness of the Health Social Determinants (SDH) education program.

Methods

Research design

This study used thematic analysis under the constructivist paradigm to explore the reports of 33 students who participated in the seminar course between 2015 and 2021, as well as the videos students collaboratively produced each year.The aim was to explore how medical students construct their understanding of the social determinants of health (SDH) through participation in an experiential learning course, and how they achieve self-growth in the process.

According to constructivist theory, knowledge is actively constructed by individuals through interactions with their environment. Individuals process and understand new information based on their existing experiences and cognitive structures, thereby forming new knowledge. As a learning approach, constructivist theory emphasizes that knowledge construction relies not only on personal experience but also on the learner’s active engagement in the learning process. This involves autonomous inquiry, collaborative learning, and the construction of knowledge within real-world contexts [11]. In this study, we will analyze how medical students gradually construct their understanding of SDH through their interactions with the social environment and direct experiences with marginalized groups. At the same time, we will explore how, through reflecting on these social experiences, students form new knowledge frameworks and medical perspectives. This study will explore the following questions:

-

i)

How do medical students construct their understanding of social determinants of health through direct exposure to marginalized groups?

-

ii)

How do students reflect on and redefine their medical knowledge, particularly the role of social health factors, through experiential learning?

-

iii)

How do students form new medical knowledge during the reflection process and apply it to actual medical practice?

Development of SDH education programs

Since 2015, we have developed an 8-week elective course for third-year students at Juntendo University School of Medicine in Japan. The course is centered on the theme of “health disparities,” to allow students to learn about social determinants of health (SDH) through direct interactions with marginalized groups. The curriculum development for this study is based on Kolb’s experiential learning theory, which emphasizes learning as a cyclical process comprising four main stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation [12]. Kolb’s model provides a structured framework for course design, helping us achieve a comprehensive understanding of SDH in medical students through practical engagement.

Concrete Experience: Students gain real-world social experience by interacting with marginalized groups. These experiences include participating in the support group for the youth displaced and experiencing homelessness due to neglect or abuse at home; providing food, clothing, and communication to people living in poverty or homelessness in temporary shelters while interacting with social support staff from the organizers; tutoring children of foreign nationals living in poverty in Japan, playing games with them; listening to personal stories of individuals with particular sexual orientation and gender identity such as LGBTQ; visiting juvenile correctional facilities and participatin staff lectures. These social experiences provide the foundation for subsequent reflection and learning.

Reflective Observation: The reflection sessions are held after each practical session and every Mondays to review the experience from previous week through group discussions and individual reflections. Students reflect on how these experiences influence their understanding of SDH. During this stage, instructors guide students to analyze their experiences, recognize the role of social factors, and think about how to integrate these factors into medical practice.

Abstract Conceptualization: After completing all practical activities, students are required to reconstruct their knowledge through reflection. In the reports submitted, students are asked to describe the following three items: (1) how their thinking and values have changed as a result of participating in social practice activities, and in what situations they became aware of these changes; (2) the importance of Social Determinants of Health (SDH) education in medical schools; (3) the possibility of implementing SDH education at their university. This process helps students deepen their understanding of SDH and reflect more deeply on their future roles as doctors.

Active Experimentation: After the course ends, students are asked to create promotional videos about SDH and present them within the school. This encourages students to share their newfound knowledge and understanding with others. This phase helps students deepen their understanding of SDH and apply this knowledge in practice.

Through these four stages, the course is designed to help medical students deepen their understanding of SDH by moving from direct experience to reflection, then to theoretical conceptualization, and finally to practical application. This process equips them to better serve marginalized groups in future medical practice. The specific course content can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Content of experiential learning activities

| Week Number | Experience activity content | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st week |

• The first day: • Course Description • Animation |

Support for Children and Low-Income Families with Foreign Connections 1. After-school learning support 2. Tutoring children who cannot attend cram schools 3. Talking to the children’s mothers Assistance for Foreign Nationals in Japan 1. Participating in health consultations/health seminars for foreigners 2. Visiting health classrooms 3. Attending simple Japanese language learning sessions 4. Communicating with medical interpreters Learning about displaced youth experiencing homelessness due to neglect and abuse at home 1. Participating in a night-time city tour organized by the Support Center for the youth on street Support for the Homeless and Those Living in Temporary Shelters 2. Providing clothing and masks 3. Medical and welfare consultations 4. Visiting family medical and community clinics 5. Listening to the stories of homeless individuals Learning about LGBTQ Issues 1. Watching films about LGBTQ topics 2. Attending “LGBTQ Seminars for Medical Professionals” 3. Interviewing LGBTQ individuals Support for Home Healthcare and Elderly Living Alone 1. Visiting home healthcare services 2. Communicating with family doctors 3. Reciting poetry and singing with patients 4. Talking to patients’ spouses Learning about Correctional Medicine 1. Visiting juvenile detention centers and adult correctional medical centers 2. Attending lectures by medical staff at juvenile detention centers From Week 5 to Week 7, experiential activities were conducted while writing reflective reports and creating videos. |

| 2nd Week | Production Lecture Every Monday, medical students gather to discuss and reflect on the activities from the previous week. | |

| 3rd Week | ||

| 4th Week | ||

| 5th Week | ||

| 6th week | ||

| 7th week | ||

| 8th week |

• Final Reflection • Report Submission • Animation Presentation |

A 10-minute video report to share learning experiences with fellow medical students. |

Data collection

We collected reports from 33 students who participated in the seminar course between 2015 and 2021, along with videos they produced collaboratively.Text data converted from submitted reports to word files and transcribed video narrations were used for analysis. Students who participated in the seminar were informed about the intent of the study, and that their consent was obtained by explaining that their consent would not affect their evaluation grade.

Data analysis

In this study, we used the thematic analysis method under the constructivist paradigm. Thematic analysis is a data-driven approach for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within qualitative data [13, 14]. This approach is particularly effective for identifying recurring themes and changes in participants’ attitudes, experiences, and reflections. The analysis followed the six-phase process outlined by Braun and Clarke [13], which includes: becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. This process allowed for a systematic and rigorous exploration of how students’ consciousness evolved as they gained experience during the educational program. A conceptual diagram was created to visually represent the transformation in students’ consciousness, which was mapped out by capturing their changes in understanding before and after their involvement in the program.

For the data management and coding process, we used Nvivo 12.0, a qualitative research software that facilitated the organization and analysis of the textual data. First, the reports from 33 students were imported into NVivo12 and stored in a single file. NVivo is a tool that allows researchers to select specific text segments and assign codes to them. Text selection, code creation, and code assignment are performed manually by the researchers. One feature of NVivo is that when multiple codes are assigned to a sentence, all of the assigned code names are displayed simultaneously as “code strips.” Additionally, NVivo has a feature that enables the display of all text segments with the same code, allowing for a comprehensive review of descriptions selected from different students’ reports on the same screen. It is also possible to quickly return to the original student report from individual text segments and examine the surrounding context by reading the sentences before and after the selected text.

The text was initially reviewed and discussed by three researchers (GY, TK, MK), who reached a consensus on the validity of the codes, themes, and classifications assigned to the data. One of the researchers has extensive experience in qualitative research, which ensured that categories were rigorously identified, reviewed, and discussed throughout the analysis process. The analysis primarily employed an inductive approach, using inductive analysis to construct meaning from the data, develop codes, categories, themes, and findings; identify representative data supporting the findings; and interpret the findings using theories and literature [15]. Codes and themes were derived directly from the data, rather than being imposed based on pre-existing theories or frameworks. However, the researchers also integrated relevant theoretical concepts, such as Kolb’s experiential learning theory, through deductive reasoning to assist in interpreting the data within the context [16]. The combination of inductive and deductive reasoning ensured a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the data.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity in qualitative research is an ongoing process where researchers critically examine their own background, experiences, values, and how these factors influence various stages of the research process. Olmos-Vega et al. [17] stress that reflexivity involves not only recognizing potential biases but also critically reflecting on the researcher’s role and decisions throughout the study. In this study, reflexivity is explored through several key dimensions, particularly considering my dual roles as both educator and researcher, and how these roles shaped the data collection, coding choices, and interpretation of the student narratives.

Researchers’ Background and Roles

As a scholar with a background in medical education research, we have a professional investment in exploring how experiential learning influences medical students’ growth and reflections. Our positions as an educator within the same educational context potentially influences our approach to the study, especially regarding students’ interactions with marginalized groups and the social determinants of health (SDH). This awareness prompts us to remain cautious of over-relying on assumptions about students’ experiences or growth. We consciously sought to interpret the data through the lens of the students’ authentic perspectives, but we acknowledge that my own educational philosophy could have shaped our interpretation, particularly in the framing of students’ reflections and emotional responses.

Participant Interaction and Familiarity

In this study, our active participation in outreach activities and post-activity discussions with students allowed for a deeper connection and understanding of their evolving ideas. While this direct involvement enhanced our insight into the students’ emotional and cognitive shifts, it also introduces potential bias. As both an educator and researcher, our dual roles may have influenced the way students expressed themselves, knowing that their reflections would be analyzed in the context of a formal research project. Furthermore, our familiarity with the students from these discussions could have affected how we interpreted their reflections, potentially leading to a more empathetic or subjective reading of their narratives. This dynamic highlights the challenge of maintaining objectivity when researchers are also closely engaged with the participants in an educational setting.

Data Analysis Process

Drawing from our extensive experience in thematic analysis of qualitative data, we led the data analysis for this study. However, our roles as an educator involved in experiential learning may have unconsciously influenced my coding and thematic choices. For instance, we may have been more inclined to highlight themes related to emotional and cognitive growth, given our educational focus on the development of empathy and social responsibility in medical students. To mitigate potential biases, the data analysis was conducted collaboratively with the research team, ensuring that multiple perspectives were incorporated into the coding process. Regular discussions and reflections during the coding process helped refine the analytical framework. Additionally, by cross-referencing the students’ written reports with their video narratives, we employed triangulation [18] to ensure the consistency and reliability of our conclusions. Despite these efforts, it is important to recognize that our dual role as both researcher and educator may have subtly influenced both the analysis and interpretation of the students’ narratives, especially when reflecting on themes of personal growth and social responsibility.

Critical Self-Reflection

Through this reflexive process, we recognize that my dual roles as an educator and researcher likely shaped the way we engaged with the data and interacted with students. While our educational position may have fostered an empathetic approach to analyzing their experiences, it is also crucial to acknowledge that these roles can influence the way findings are framed and interpreted. For example, we focus on fostering empathy and social responsibility within the curriculum may have led us to emphasize these aspects in the data analysis. To reinforce the trustworthiness of the study, we continuously revisited the data with the research team, questioning our own interpretations and ensuring that the students’ voices remained central to the analysis. This critical self-reflection is vital in understanding the epistemological stance underpinning the research and its influence on the conclusions drawn from the study.

Results

Description of participants

The subjects of this study are 33 students (13 males and 20 females) who participated in the SDH education program from 2015 to 2021. The participants’ attributes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Student participation in the SDH education program from 2015 to 2021 (AMAB: assigned male at birth, AFAB: assigned female at birth)

| Annual | Total number of participating students | AMAB | AFAB |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2016 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| 2017 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 2018 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 2019 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| 2020 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| 2021 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 33 | 13 | 20 |

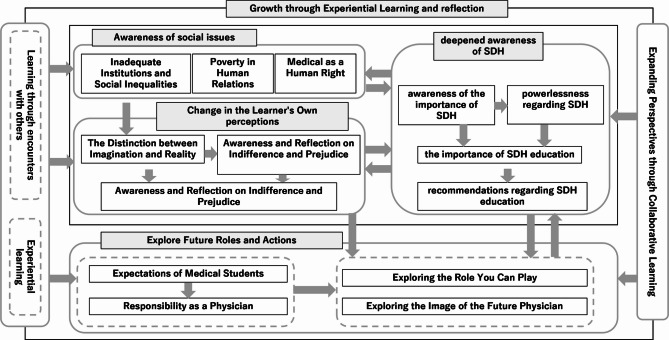

The results of the thematic analysis showed that the process of change due to the participation of medical students in the educational program generated five themes: (1) awareness of social issues, (2) changes in the learners’ perceptions, (3) deepened of awareness of SDH, (4) exploration future roles and actions, and (5) growth through experiential learning and reflection. Table 3 shows the themes and 17 sub-themes. Figure 1 helped to illustrate the shifts in perspective that emerged as a result of their engagement with marginalized groups and the subsequent reflections.

Table 3.

Thematic analysis results of medical students’ cognitive changes after participating in the SDH education program: themes and subthemes

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Awareness of social issues | Inadequate Institutions and Social Disparities |

| Poverty in Human Relations | |

| Health Care as a Human Right | |

| Change in the Learner’s Own Attitudes | The Difference between Imagination and Reality |

| Awareness and Reflection on Indifference and Prejudice | |

| Understanding and Concern for Marginalized People | |

| Increased awareness of SDH | awareness of the importance of SDH |

| powerlessness regarding SDH | |

| the importance of SDH education | |

| recommendations regarding SDH education | |

| Exploration of Future Roles and Actions | Expectations of Medical Students |

| Responsibility as a Physician | |

| Exploring the Role You Can Play | |

| Exploring the Image of the Future Physician | |

| Growth through Experiential Learning and Reflection | Learning through Experiential Learning |

| Learning through Encounters with Others | |

| Expanding Perspectives through Collaborative Learning |

Fig. 1.

Cognitive changes of medical students after participating in the SDH education project

Medical students experienced emotional and cognitive changes through their participation in experiential learning. Firstly, through the experiential activities, they gained insights into reality and recognized the differences between their previous perceptions of society and actual experiences. At the same time, the students became aware of their own internal biases and reflected on their past indifference, beginning to show empathy and compassion toward marginalized groups. Through these reflections, they recognized the importance of learning about Social Determinants of Health (SDH) as medical students, although some also felt a sense of helplessness, unsure of what they could do. In the experiential learning process, students realized that marginalized groups and their support networks had high expectations of them, which fostered a sense of responsibility as future doctors. They began to contemplate new roles for themselves as doctors in the future. This series of experiences and reflections contributed to the self-growth of the medical students.

Theme 1: Awareness of social issues

This theme includes three subthemes: inadequate systems and the society of inequality, poverty of interpersonal relationships, and healthcare as a human right. Through contact and dialogue with marginalized groups, students became aware of various structural issues such as social systems and culture, which they had not previously focused on, and which are the underlying causes of the marginalization of these groups.

“the current situation in Japan, where the refugee status recognition rate is very low. People have difficulty accessing medical care, due to the lack of refugee status. Furthermore, LGBTQ people still face lingering discrimination and prejudice.” (Student 28).

“I believe that a system or mechanism that initially causes distress to some people is itself abnormal.” (Student 31).

Through interacting with marginalized groups and listening to their stories, medical students realized that the social issues faced by marginalized populations are not only economic poverty but also the lack of meaningful interpersonal connections.

“In the end, what I felt was that people can easily fall into loneliness and social exclusion due to even the slightest changes. Moreover, I believe that the loss of connection with others and the impoverishment of relationships happen right around us. (Student 11)

In addition, medical students began to understand social issues from the perspective of social justice. They believe that refusing treatment based on a patient’s social status is a violation of human rights.

“Many people who are frequently homeless have difficult backgrounds and require medical care. However, the reality is that they are not accepted by medical institutions. Healthcare is considered a “basic human right.” I believe it is important that they should be treated as people just like us, not be turned away because they don’t have an insurance card or because they appear unable to pay.” (Video 2020).

Theme 2: Change in the learner’s own perceptions

This theme encompasses three sub-themes: ‘The Distinction between Imagination and Reality’, ‘Awareness and Reflection on Indifference and Prejudice’, and ‘Understanding and Concern for Marginalized Individuals’. Through participating in social activities supporting marginalized groups, the medical students gained insights into reality and recognized the differences between their previous views of society and their actual experiences.

“Although I thought I had a certain understanding of impoverished families, the level of poverty I witnessed in real-life encounters exceeded my previous understanding. The severity of the situation far surpassed my initial expectations.” (Student 4).

The disparities between the students’ perceptions and the actual experiences of marginalized individuals prompted the students to confront their own internal biases and contemplate the apathy they had previously exhibited.

“I used to think that people who became homeless had problems of their own. I was reminded of the fact that even if they are doing their best, they have no choice but to become homeless.” (Student 2).

The students also observed that understanding the causes behind an individual’s difficulties has made them more empathetic and compassionate when interacting with such individuals.

“The reasons for homelessness varied from person to person, and it was not something that could be simply dismissed as a matter of self-responsibility. I also learned that a high percentage of people have a mental illness or some kind of intellectual disability. I realized that I should not dismiss it as “something not of my business”, but rather that there are many people who need help in various ways.” (Student 26).

Theme 3: Deepened awareness of SDH

This theme explores four sub-themes related to the topic of Social Determinants of Health (SDH): ‘awareness of the importance of SDH’, ‘powerlessness regarding SDH’, ‘the importance of SDH education’, and ‘recommendations regarding SDH education’. These sub-themes reflect the students’ perspectives on the educational program. Through practical experiences, medical students realized the importance of learning about SDH. They observed and recognized that various social determinants have both direct and indirect impacts on the health of marginalized individuals.

“I thought it was especially important to have a perspective on SDH that considers the background of the patients (and not simply their symptoms and test results). I needed to know what was going on with the patients who came to the hospital.” (Video 2019).

At the same time, some of the students felt helpless in the face of SDH and wondered if there was anything they could do, including changing the structural factors.

“Although I was able to learn many things about the social system and problems in the medical field, I also felt frustrated, because there is not much I can currently do as a student.” (Student 26).

However, students also stated that SDH education is essential for medical students to become physicians with a broad perspective that allows them to understand the backgrounds of their patients.

“Through SDH education, we believe that people from different life circumstances should know that there are unimaginable determinants of health. Hospitals are visited by people from various backgrounds and economic conditions. SDH education is necessary, to remove unconscious discriminatory attitudes and prejudices, and for us to become impartial physicians.” (Students 16).

The student also suggests implementing SDH educational programs within the current medical school curriculum. He shares that, based on his own experience, learning about SDH has been beneficial in his work as a physician. Furthermore, this learning experience has enhanced his understanding of the patient’s current situation.

“If we seek to work more holistically, I would recommend having students to see and experience people who suffer in the field, and at the social structures that contribute to SDH.” (Students 32).

Theme 4: Explore future roles and actions

This theme includes four sub-themes: Expectations of Medical Students’, ‘Responsibility as a Physician’, ‘Exploring the Role You Can Play’, and ‘Exploring the Image of the Future Physician’. As the course progressed, marginalized groups and support organizations expressed their joy and gratitude for the medical students’ active participation in the activities. This experience made the medical students realize that marginalized groups and support organizations have high expectations of them.

As medical students participating in the activities, we heard many voices saying “Thank you”. “Thank you for your understanding, ” and “Thank you for your concern.” Every time we heard such words, we truly felt their expectations of us as future doctors, and that this is a profession with great influence. (Video, 2022)

It was an opportunity for the students to become aware that they are medical students and to keenly feel the weight of their responsibility.

“I realized they appreciated the interest we, as future doctors, took in learning about their experiences. They were grateful that we’d dedicate our time to them. Even though I still saw myself as a student, it was during this time that I truly understood the weight of my responsibilities as a medical student. I started to feel the pressure of the future responsibilities I’d carry as a healthcare professional.” (Video, 2020).

In light of these statements, the students began to think about what they should be doing now. One of the concerns mentioned by this student was his role as an advocate in sharing what he had learned.

“We made a video presentation about what we experienced and learned in the course and what we can do to help. We wanted to show this to as many medical students as possible, to let them know how much SDH affects our health and how important it is to deepen our understanding of SDH.” (Students 24).

The students began to think about what kind of doctor I should aspire to be in the future: a doctor who builds human connections for the marginalized, a doctor who becomes a place to stay, and a doctor who supports his patients.

“If, in the future, I were to become a doctor, and I were in charge of an outpatient clinic if a patient came to me suffering from financial or relational poverty, I would listen carefully to the patient’s story, look into the patient’s background, and understand the patient’s situation. By doing so, even the doctor’s office could become a welcoming place for the patient.” (Student 7).

Theme 5: Growth through experiential learning and reflection

This theme includes three sub-themes: “Learning through Experiential Learning”, “Learning through Encounters with Others”, and “Expanding Perspectives through Collaborative Learning”. Through students’ actual participation in experiential learning, they recognized the importance of thinking from the other person’s perspective and learned how to relate to other people.

“Specifically, while handing out heat stroke prevention goods at the soup kitchen, we had a pleasant chat about the Hakone Ekiden, a trivial topic, and I learned that they are no different from people I am familiar with. I believe that when we can see things from multiple perspectives, we will be able to step a little closer and be kinder to others whose behavior we do not understand”. (Student 16)

In this theme, students engaged in activities like distributing food at a relief kitchen and assisting marginalized groups. They also interacted directly with those in need and their support networks. These experiences allowed students to witness poverty firsthand and deepen their understanding of social determinants of health (SDH).

“I understood that there are types of difficulties that I could not have imagined before I started my study. By learning while interacting with the people involved, I was able to perceive the issues as more real and in need of solutions, than the knowledge I have read about in books.” (Students 16).

After each week’s activity, students gathered to reflect on their experiences, sharing their thoughts and feelings. Through this reflection, they realized that even shared experiences could lead to different perspectives. They recognized their personal growth in learning to approach issues from multiple viewpoints.

“The weekly review meetings and discussions with the group were really meaningful to me. It was interesting to see how different people noticed the same things in different ways. Sometimes, I felt relieved to hear the same opinions as mine. By talking through our thoughts, we were able to organize our feelings and apply them to our plans for the next week. It was also eye-opening to realize how small differences in the language we use can leave a completely different impression on others.” (Student 23).

Discussion

This study aims to explore how medical students’ understanding of social determinants of health (SDH) changes after engaging in experiential learning through social practice, and how they achieve personal growth in terms of cognition, emotion, and social responsibility. By analyzing the reflective reports of 33 students who participated in the program from 2015 to 2022, the findings show that students, through exposure to marginalized groups, gradually became aware of the complexities of health inequalities and social structural issues, and reexamined their medical knowledge in the process.

Transformations in emotion, cognition, and social responsibility

Through experiential learning, students underwent significant changes in both emotion and cognition, gaining a deeper understanding of how social factors influence health. Their sense of social responsibility was notably enhanced, as they recognized the importance of social determinants of health (SDH) not just in individual health but also in their future roles as doctors. Students acknowledged that they should focus on addressing these social factors as part of their medical practice. The findings from this study highlight how experiential learning fosters transformations in knowledge construction, emotional reflection, and social responsibility among medical students.

Expanding the role of experiential learning in medical education

This study offers new perspectives on the role of experiential learning in medical education, particularly in how it helps students address SDH and prepares them to confront healthcare challenges in marginalized communities. The results support previous research indicating that experiential learning enhances students’ empathy and deepens their understanding of SDH [19, 20]. However, the study also challenges existing viewpoints by revealing that, although students increased their awareness of SDH, many felt powerless when attempting to confront these issues, particularly within the constraints of medical practice. This finding aligns with the work of Ohta et al. [21] and Lewis et al. [22], who highlighted the challenges medical learners face, particularly in translating SDH theory into practical action.

While many studies suggest that experiential learning has a transformative effect, this study uncovers the complex emotional responses students experience when confronting social inequalities and health disparities. Feelings of powerlessness and confusion emerged as common themes, suggesting that educational programs may need to place greater emphasis on providing students with practical tools to better address these challenges.

Kolb’s experiential learning theory in practice

Kolb’s experiential learning theory [23] posits that learning occurs through a cyclical process of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. This study’s findings illustrate how these stages are reflected in students’ engagement with marginalized groups and the resulting shifts in their understanding of Social Determinants of Health (SDH).

In the first stage of Kolb’s cycle—concrete experience—students directly participated in service-learning activities, which involved interacting with marginalized groups and observing social inequities. These real-world experiences, often surprising and emotionally impactful, provided the raw material for their learning process. The second stage, reflective observation, was a crucial point of transformation in this study. Through post-activity reflections, both individual and group-based, students confronted their misconceptions and biases. Many students reported feelings of surprise, distress, and sometimes remorse upon realizing the gap between their initial assumptions and the realities they encountered. For example, one student stated, “I was horrified by the dangers I thought I knew,” reflecting a significant emotional dissonance between their previous and newly acquired understanding of social inequalities. These emotional responses suggest that the reflection phase, as outlined by Kolb, helped students critically examine their beliefs and expand their worldview. In the third stage—abstract conceptualization—students were able to organize their experiences within the SDH framework. They connected their newfound insights to existing theoretical knowledge, deepening their understanding of how social factors influence health. In the final stage, active experimentation, students not only reflected on their new role as future healthcare providers but also began to envision actions they could take to advocate for marginalized groups. The shift from “I understand” to “I know what to do” exemplifies Kolb’s theory of experiential learning, where new knowledge is integrated into practical application.

Mezirow’s transformative learning theory and cognitive shifts

Mezirow’s transformative learning theory [24] provides further depth to the understanding of students’ cognitive and emotional shifts during the program. Transformative learning occurs when students critically reflect on their assumptions, leading to a fundamental change in their worldview. In this study, many students underwent significant transformations as they reflected on their preconceived notions about marginalized groups. For instance, students expressed regret for their prior assumptions, illustrating the cognitive shifts Mezirow describes. As one student reflected, “I reflected on my assumption,” signaling a recognition of personal biases and a deeper understanding of their own social responsibility.

The emotional dissonance students experienced—such as feelings of remorse and surprise—aligns with Mezirow’s notion of “disorienting dilemmas,” where learners are confronted with experiences that challenge their existing beliefs. These disorienting dilemmas prompted students to reframe their understanding of social inequality and their future roles as healthcare providers. The recognition of their own biases and assumptions, followed by a critical reassessment of those beliefs, highlights the transformative process where students not only acquired knowledge but also reshaped their professional identity.

Moreover, the transformative learning process extended beyond the academic realm, influencing students’ personal values and broader worldview. As Mezirow suggests, this process is not merely about acquiring new knowledge but about fundamentally changing how learners perceive themselves and their role in society. For example, several students expressed a newfound commitment to advocating for health equity and addressing SDH in their future medical practices, reflecting a shift from passive learning to active, socially responsible engagement.

Integration of Kolb’s and Mezirow’s theories

The integration of Kolb’s and Mezirow’s frameworks provides a comprehensive understanding of how experiential learning in this study not only facilitated the development of cognitive skills and knowledge but also promoted deep emotional and identity transformations. While Kolb’s theory emphasizes the cyclical process of learning through experience, reflection, and action, Mezirow’s transformative learning theory deepens the analysis by highlighting the profound shifts in students’ personal values and professional identities. The findings of this study extend these theories by demonstrating that experiential learning in the context of SDH education leads not only to cognitive and emotional growth but also to significant changes in students’ professional identities, social responsibility, and commitment to addressing social inequalities in healthcare.

The role of social context and interpersonal interactions in learning

Another possible explanation is that students’ reflections were influenced not only by the learning content but also by the social and emotional context of the educational program, highlighting the crucial role of interpersonal interactions and a supportive learning environment. This suggests that learning is not solely an individual cognitive process but also a socially interactive and culturally shaped process [25].

This interactive environment helped students develop new understandings through social practice and, by collaborating with others and reflecting, deepened their awareness of social determinants. Overall, Kolb’s theory provides a strong framework for understanding this transformative learning process and reveals how experiential learning, through social interaction and reflection, fosters students’ comprehensive growth in cognition, emotion, and social responsibility.

Implications for medical education and future research directions

The significance of these findings lies in their implications for medical education. This study highlights the necessity of integrating SDH more deeply into medical curricula—not only through theoretical learning but also through opportunities for practical experiences that challenge students to reflect on and confront health inequities. The research demonstrates that such an educational model can significantly enhance students’ awareness of social issues and foster their empathy and sense of responsibility toward marginalized communities.

However, given that students expressed feelings of powerlessness, future research should explore how to better support students in translating their newly acquired knowledge into concrete action. Longitudinal studies could examine whether these shifts in awareness continue to influence students’ attitudes and behaviors once they enter the workforce. Furthermore, sustained support and mentoring could help students translate experiential learning outcomes into actual clinical practice and public health actions.

Future research should also investigate how to strengthen the integration of reflective and collaborative learning in medical education to better prepare students for professional challenges [26, 27]. Ultimately, enhancing the role of experiential learning in SDH education could play a key role in developing healthcare professionals who are more socially responsible and empathetic.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that the reports were submitted as assignments, which may have led to social desirability bias. Students may have been inclined to emphasize the positive aspects of the educational program to gain favorable evaluations, potentially neglecting or concealing negative feelings toward marginalized groups [28]. This could affect the authenticity and comprehensiveness of the findings.

Additionally, the SDH education program was conducted as an elective, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The students who chose to participate were likely more motivated and had a predisposed interest in social issues, meaning that the changes observed may not be representative of all medical students. This self-selection bias could have influenced the nature of the reflections collected, as students with an intrinsic interest in social determinants of health (SDH) might engage with the course material in a more thoughtful and profound manner than students who may not have chosen to participate in the program. Those students less inclined to reflect on social issues may not have experienced similar emotional or cognitive growth, which could have shaped the depth of their reflections differently. Consequently, the findings of this study, while valuable, may not reflect the experiences of a broader cohort of medical students who have not self-selected into an elective program focused on SDH.

Furthermore, the elective nature of the course may restrict the generalizability of these results to other medical education programs. While the findings demonstrate the potential impact of experiential learning on students with pre-existing interest in social responsibility, the elective model may not be reflective of how SDH education could function in a mandatory curriculum. If SDH education were integrated into the core curriculum, it would be essential to assess whether similar transformative effects could be observed among students who did not actively choose to participate, and whether such education would be as effectively engaged by a broader, more diverse group of students. Therefore, future research should explore the impact of SDH education in both elective and mandatory settings, to better understand how the structure of such programs might influence the experiences and reflections of students across different medical student populations.

Finally, this study primarily assessed short-term effects and did not explore whether changes in awareness and attitudes would be sustained over time or translated into practical action once students enter the workforce. Future research should focus on examining the long-term effects of these changes and explore how experiential learning can be applied in practice.

Conclusion

This study provides compelling evidence for the integration of social determinants of health (SDH) education into medical training, demonstrating that experiential learning plays a crucial role in helping medical students develop a deeper understanding of the complex social factors that influence health. By engaging directly with marginalized communities, students not only enhanced their cognitive and emotional awareness of SDH but also experienced significant growth in their sense of social responsibility. These findings underscore the transformative potential of experiential learning in fostering empathy, critical thinking, and a commitment to addressing health inequities.

Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical action, suggesting that educational programs should place greater emphasis on equipping students with concrete tools to navigate these challenges within the limitations of medical practice. Future research should explore how to translate these insights into sustained behavioral changes and better integrate reflective and collaborative learning methods to equip students for the challenges of modern healthcare. Strengthening these educational strategies will be essential in developing healthcare professionals who are not only clinically competent but also socially responsible and empathetic.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Yoko Muranaka for her advice in promoting the project and writing the paper; We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Kyoko Ueno for her valuable advice on writing my dissertation; We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Lijuan Wang and Xin Zhang Support and help to my dissertation.

Author contributions

Yurong Ge: Conceptualisation (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (equal); writing—original draft (lead). Makie Ariga: Conceptualisation (supporting); Formal analysis (equal).Yoko Takeda: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Writing-review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Foundation of the Ministry of Culture, Science and Technology, Japan. This study was funded by a KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Number: 18H03030) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with the approval of the Juntendo University Ethics Review Committee (Juntendo University Medical Ethics approval No. 2020278). Participating students could not be identified because text data were strictly controlled and analyzed after anonymity. Our research process verified the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ): a 32-item checklist.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/understanding/sdh-definition/en/. Accessed 12 March 2024.

- 2.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):129–35. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter K, Thomson B. A scoping review of social determinants of health curricula in post-graduate medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2019;10(3):61–71. PMID: 31388378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraze TK, Brewster AL, Lewis VA, Beidler LB, Murray GF, Colla CH. Prevalence of screening for food insecurity, housing instability, utility needs, transportation needs, and interpersonal violence by US physician practices and hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Serwint JR. Screening for basic social needs at a medical home for low-income children. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48(1):32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry, Japanese. of education, culture, sports, science and technology. Medical education model core curriculum, revised). https://www.mext.go.jp/component/b_menu/shingi/toushin/__icsFiles/afeldfle/2017/06/28/1383961_01.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec 2023.

- 7.Ministry. Dec of education, culture, sports, science and technology. Medical education model core curriculum revised 2022. Available from: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20221202-mtx_igaku-000026049_00001.pdf. Accessed 3 2023.

- 8.Mizumoto J, Son D, Izumiya M, Horita S, Eto M. Experience of residents learning about social determinants of health and an assessment tool: Mixed-methods research. J Gen Fam Med. 2022;23:319–26. 10.1002/jgf2.559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakata K, Kanno K, Fujita H. Experiential learning in medical education: the role of social determinants of health in Japan. Med Teach. 2023;45(7):763–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi Y, Saito T, Uchida Y. Three-year evaluation of a program teaching social determinants of health in community-based medical education: A general inductive approach for qualitative data analysis. J Med Educ. 2021;46(8):1152–61. 10.1186/s12909-023-04320-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Packer M, Goicoechea J. The new Constructivism: A reflection on theory and practice. Routledge; 2021.

- 12.Kolb AY, Kolb DA. The experiential educator: principles and practices of experiential learning. Kendall Hunt Publishing; 2017.

- 13.Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide 131. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):846–54. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychol. 2022;9(1):3–14. 10.1037/qup0000196 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bingham AJ, Witkowsky P. Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: after the interview. Sage; 2022.

- 16.Bingham AJ. From data management to actionable findings: A five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. Int J Qual Methods. 2023;22. 10.1177/16094069231183620

- 17.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage; 2022.

- 18.Olmos-Vega FM, Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L, Kahlke R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide 149. Med Teach. 2023;45(3):241–51. 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizumoto J, Son D, Izumiya M, Horita S, Eto M. Experience of residents learning about social determinants of health and an assessment tool: Mixed-methods research. J Gen Fam Med. 2022;23(5):319–26. 10.1002/jgf2.559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohta R, Kaneko M, Nakamura K. Challenges in community-based education: medical students’ perspectives on health disparities and social determinants of health. J Med Educ. 2021;45(2):98–106. 10.1002/jme.22115 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeda S, Fujimoto K, Yamada T. Experiential learning in medical education: addressing social determinants of health in the curriculum. J Med Educ. 2019;43(4):269–78. 10.1111/jme.13188 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis M, Roberts R, Thompson P. The integration of experiential learning in medical education: A strategy for addressing healthcare inequities. Med Educ Rev. 2020;41(5):512–20. 10.1111/medu.14111 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolb DA, Kolb AY. The experiential educator: principles and practices of experiential learning. Experience Based Learning Systems; 2017.

- 24.Mezirow J. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packer M, Goicoechea J. The role of constructivist theory in education: A reflection on the contributions of Piaget and Vygotsky. Educational Psychol. 2021;41(4):457–75. 10.1080/01443410.2021.1939123 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb G. Collaborative learning: A guide for teaching. Springer; 2009.

- 27.Kiger M, Varpio L. Structured reflection in medical education: enhancing critical thinking and addressing biases. Med Educ Res. 2020;34(5):55–63. 10.1111/medu.13987 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergen N, Labonté R. Everything is perfect, and we have no problems: detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(5):783–92. 10.1177/1049732319889354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.