Abstract

Background:

Long wait times for scheduled surgery are a major problem in Canadian health systems. We sought to determine the extent to which single-entry referral models (next available consultation), team-based care models (next available surgery regardless of consulting surgeon), or both could affect wait times for consultations and surgery.

Methods:

We performed a discrete-event simulation study of wait times for consultations and surgeries for knee and hip joint replacement in Ontario’s 5 postal regions using prospectively collected data on surgical wait times. We simulated the effects of coordinated referral models on the wait time for consultation (wait 1) and surgery (wait 2).

Results:

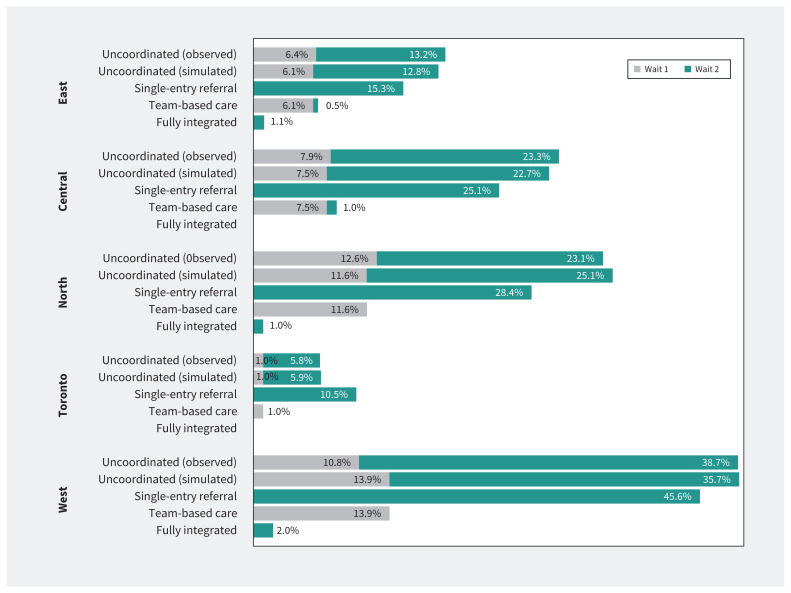

Coordinated models led to larger reductions in high-outlier wait times (as reflected by the 90th percentile and the percentage of patients exceeding wait-time targets) than on median wait times when compared with the status quo. Single-entry referral models largely influenced wait 1, and team-based models of care affected only wait 2. Fully integrated models incorporating both single-entry referral and team-based care largely prevented patients from exceeding both wait-1 and wait-2 targets; the percentage of patients exceeding wait-1 targets in these models was 0% in all regions, and the percentage exceeding wait-2 targets was 0% except for Ontario West (2.0%, from 35.7% at baseline), East (1.1%, from 22.7% at baseline), and North (1.0%, from 25.1% at baseline).

Interpretation:

Coordinated referral and practice models improve access to scheduled surgery in Canadian health systems. Implementation of these models could largely eliminate prolonged wait times for joint replacement surgery in Ontario.

Canada performs poorly in international comparisons of health systems, particularly owing to challenges with timely access to health services.1 Long wait times for scheduled surgery are a major policy challenge that threatens public confidence in Canadian health systems.2,3 Whereas some Canadian provinces have been increasingly experimenting with private for-profit delivery of services, such as joint replacement and cataract surgery, in hopes of reducing wait times,4,5 other policy approaches, such as single-entry referral models6 and team-based (shared) care,7 could reduce surgical wait times substantially and improve geographic and socioeconomic inequities in wait times, which might worsen with other types of interventions. If the potential benefit of these models of care were better quantified, policy-makers and health authorities could more persuasively champion their implementation, which faces stiff resistance from some participants in the health system.

We sought to determine the extent to which single-entry referral models and team-based care could affect wait times for consultations and surgery, without the need for major health-system changes such as increased funding to hospitals or increased investment in private for-profit surgical facilities.

Methods

We performed a simulation modelling study of wait times for hip and knee joint replacement surgery in Ontario using routinely collected electronic wait time information. We investigated 3 models of care using discrete-event simulation to represent the process of referrals arriving at a destination (either a surgeon in a referral network or a central intake), subsequent distribution of referrals to surgeons, surgical consultations, distribution of patients to surgeons according to the model of care, operating room assignment, and surgical procedures. We chose discreteevent simulation for its ability to capture the dynamic flow of events over time, reflecting real-world variability in patient arrivals, wait times, and resource availability, ensuring a realistic evaluation of each care model.8,9

Data sources and linkage

We analyzed data from the Wait Time Information System (a prospective registry of wait times for most non-urgent surgical procedures maintained by Ontario Health)10 to identify procedures and surgeons, Ontario Health Insurance Plan physician claims data to identify referring physician,11 and the Registered Persons Database for patient demographic characteristics, such as area of residence.12 These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES, a not-for-profit research institute that brings together research, data, and clinical experts, whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law permits it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data without consent for the purposes of health system evaluation and improvement.

Study population

We analyzed hip and knee joint replacement (arthroplasty) procedures; 88.5% of orthopedic surgeons in our data set performed both hip and knee joint replacement.13 Joint replacement is common and substantially improves patients’ quality of life;14,15 prolonged wait times for these procedures can lead to worsening pain, reduced mobility, and deteriorating overall health.

We included all procedures performed in patients who were referred by a general practitioner or family physician to an orthopedic surgeon for joint replacement surgery between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2017, and subsequently underwent a non-emergency operation, who had complete wait time information in the Wait Time Information System and whose procedures were categorized as priority 3 or 4 (the lowest level of urgency as categorized by Ontario Health). We assumed that all such patients had non-urgent conditions and that any variation in wait times for these patients resulted from system factors and random variation rather than clinical urgency. We selected this referral period to include patients who underwent consultation and non-urgent surgery before the COVID-19 pandemic. We included procedures in Ontario’s 5 postal regions (Appendix 1, Supplemental Figure, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.241755/tab-related-content) according to the first letter of the postal code of the patient’s residence, grouped as follows: East (K), Central (L), North (P), Toronto (M), and West (N). We selected these regions because they closely approximate Ontario’s current health regions, which did not yet exist as administrative health areas during the study period.

Models of care

Most referrals from primary care providers to specialists in Ontario occur by direct physician-to-physician referral, and most surgeons work as independent practitioners who manage their own queues for new patient consultations and surgeries.13 They typically do not share the care of patients with other surgeons once they have assumed responsibility for performing a surgery.

We explored the use of models of care that introduce a measure of coordination by managing the flow of patients to 1 or both of the following: appointments for new surgical consultations; and surgical procedure dates, after a decision to proceed with surgery has been made. We analyzed 2 types of alternative models, described in this study as single-entry referral (also called “central intake,” whereby all referrals within each of Ontario’s 5 postal regions are pooled, and patients are directed in order of entry into the queue to the next available provider for consultation), and team-based care (also called “shared care,” whereby patients for whom surgery is recommended after consultation are pooled into a single regional queue, and each patient is scheduled into the next available surgical date with any surgeon in the region, in order of entry into the queue). We also examined a fully integrated model, whereby both single-entry and team-based care are used: patients are pooled into a single queue and are seen by the next available surgeon within a region for a consultation, and after consultation patients enter another queue and undergo surgery by the next available surgeon within the region.

Outcome measures

Ontario Health defines wait 1 as the time between the date a primary care physician refers a patient to a specialist and the date of the patient’s first appointment with that specialist, and wait 2 as the interval from the date the surgeon and patient decide to proceed with surgery to the date of the surgical procedure, subtracting any delays related to a patient’s readiness for treatment.

In Ontario, wait-time benchmarks (the target time within which 90% of patients are seen or treated)16 for priority-4 patients undergoing hip and knee joint replacement surgery are 182 days for wait 1 and 182 days for wait 2; for priority-3 patients, these benchmarks are 90 days for wait 1 and 84 days for wait 2.

Statistical analysis

We used discrete-event simulation to represent the process of referrals arriving at a destination (either a surgeon in a referral network or a central intake), subsequent distribution of referrals to surgeons, surgical consultations, and the distribution of patients to surgeons according to the model of care, operating room assignment, and the surgical procedures.

We created a simulation model of existing referral networks within each region, based on each patient’s area of residence and the observed network of referring physician-to-surgeon and surgeon-to-hospital connections and their corresponding service rates, excluding the 10% of surgeons connected to the largest number of referring physicians and the 10% of surgeons connected to the fewest referring physicians; this exclusion was necessary to achieve a stable simulation and is not expected to have an impact on the effects of different models of care. We simulated 3 alternative models: single-entry referral only, team-based care only, and fully integrated (single-entry referral combined with team-based care). The observed (unmodelled) data reported include the top and bottom 10% of connections.

We made the following assumptions in the simulation: priority-3 and -4 patients were managed similarly without differential prioritization; all patients in coordinated models of care followed their assigned destination (i.e., individual choice of provider was not available to patients or to referring providers); referral markets were organized on a regional basis (based on postal regions); the capacity of hospital operating rooms was estimated based on the average number of procedures per day that were performed during an 8-hour workday, excluding weekends; the network capacity, including the number of surgeons and referring physicians, consultations, hospitals, surgical procedures, and the connection networks, remained constant throughout the simulation period; and patient demand and demographic characteristics remained constant.

To create a steady-state model, we started each simulation with a 10-year warm-up period based on the existing (uncoordinated) referral network in 2017. Each simulation began with an empty system, and patients were selected randomly from the pool of eligible patients based on a Poisson distribution of the arrival rates of new patients. A 10-year period was required for the simulated wait times to reach a steady state, whereby additional cycles of the model did not change the simulated wait times. Following this warm-up, each new model of care was introduced and cycled over a 15-year period to allow for a stable simulation. These models can be interpreted as reflecting what wait times would be observed, assuming that the model of care under study had been in place for a prolonged period and had achieved a steady state. We estimated median and 90th percentile wait times, and analyzed the proportion of patients who received services beyond the wait-1 and wait-2 benchmarks of 182 days. Additional technical information about the simulation model is included in Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.241755/tab-related-content).

To explore the effect of baseline assumptions about the structure of existing referral networks on our results, we performed sensitivity analyses to measure the variation in key parameters (Appendix 1). We processed data using Pandas and Spark17,18 in Python — a data-processing engine designed for large-scale data analytics — to estimate the inter-arrival times and time intervals between consultations and surgeries, which served as input parameters for the simulation.19 We executed the simulation on the AnyLogic Professional platform 8.9.0 running on a Linux environment.

Ethics approval

The use of the data in this project is authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act and does not require review by a research ethics board.

Results

The simulations were based on data from 17 465 procedures (Figure 1) involving 17 132 patients, 7783 referring physicians, 274 surgeons, and 71 hospitals in Ontario’s 5 postal regions (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Reasons for exclusion of procedures not included in the simulation model. Note: FP = family physician, GP = general practitioner. See Related Content tab for accessible version.

Table 1:

Referral networks of patients who underwent hip and knee replacement surgery and were referred by a primary care provider with a known referral date between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2017, stratified by Ontario postal region*

| Region | No. of patients | No. of referring physicians | No. of surgeons | No. of hospitals | No. of knee procedures | No. of hip procedures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | 3502 | 1401 | 48 | 17 | 2171 | 1360 |

| Central | 4633 | 2344 | 91 | 18 | 2919 | 1799 |

| North | 1747 | 620 | 24 | 10 | 1176 | 641 |

| Toronto | 3155 | 1955 | 59 | 11 | 1952 | 1242 |

| West | 4095 | 1463 | 52 | 15 | 2483 | 1722 |

| Total | 17 132 | 7783 | 274 | 71 | 10 701 | 6764 |

Patients who had surgery by the 10% of surgeons connected to the highest number of referring physicians and patients who had surgery by the 10% of surgeons connected to the lowest number of referring physicians were excluded.

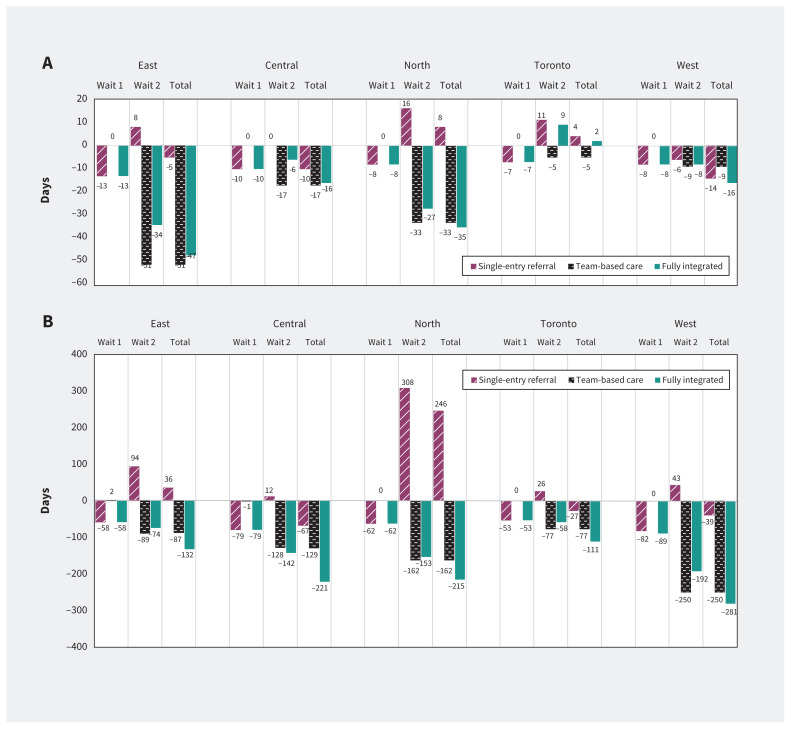

Simulated wait times for the referral networks and practice models that existed in Ontario during the study period (described as “uncoordinated” networks) were similar to the observed wait times (Table 2). Figure 2 presents changes in median (Figure 2A) and 90th percentile (Figure 2B) wait times. Single-entry referral models led to modest reductions in median wait 1 times in all regions, with a much larger effect on attenuating the variation in wait-1 times, reflected in the substantial reduction in the 90th percentiles of wait 1 in each region, ranging from a reduction of 53 days in Toronto (from 103 to 50 d) to a reduction of 82 days in Ontario West (from 186 to 104 d; Table 2 and Figure 2B). Single-entry referral models in isolation did not consistently reduce wait-2 times, and in 3 of the 5 regions the median and 90th percentile wait-2 times increased under a single-entry referral model. Team-based models of care (without single-entry referral models) reduced the median and 90th percentile of wait-2 times in all the regions and had no effect on wait-1 times. Fully integrated models resulted in substantial decreases in the 90th percentile for total wait time (wait 1 and wait 2) in all regions, ranging from a reduction of 111 days in Toronto (from 257 to 146 d) to a reduction of 281 days in Ontario West (from 536 to 255 d), with a modest decrease in median total wait time in all regions except in the Toronto region (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2:

Surgical wait times for different referral and practice models, by Ontario postal region

| Region; model of care | Days, median (90th percentile) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wait 1* | Wait 2† | Total wait (wait 1 + wait 2) | |

| East | |||

| Uncoordinated (market-based) | |||

| Actual (observed) | 64 (143) | 87 (195) | 151 (338) |

| Simulated | 64 (138) | 81 (178) | 145 (316) |

| Coordinated | |||

| Single-entry referral only | 51 (80) | 89 (272) | 140 (352) |

| Team-based care only | 64 (140) | 30 (89) | 94 (229) |

| Fully integrated (single-entry referral and team-based care) | 51 (80) | 47 (104) | 98 (184) |

| Central | |||

| Uncoordinated (market-based) | |||

| Actual (observed) | 50 (151) | 89 (280) | 139 (431) |

| Simulated | 50 (143) | 81 (240) | 131 (380) |

| Coordinated | |||

| Single-entry referral only | 40 (64) | 81 (252) | 121 (316) |

| Team-based care only | 50 (142) | 64 (112) | 114 (254) |

| Fully integrated (single-entry referral and team-based care) | 40 (64) | 75 (98) | 115 (162) |

| North | |||

| Uncoordinated (market-based) | |||

| Actual (observed) | 51 (179) | 81 (224) | 132 (403) |

| Simulated | 48 (138) | 77 (263) | 125 (401) |

| Coordinated | |||

| Single-entry referral only | 40 (76) | 93 (571) | 133 (647) |

| Team-based care only | 48 (138) | 44 (101) | 92 (239) |

| Fully integrated (single-entry referral and team-based care) | 40 (76) | 50 (110) | 90 (186) |

| Toronto | |||

| Uncoordinated (market-based) | |||

| Actual (observed) | 42 (107) | 68 (158) | 110 (265) |

| Simulated | 43 (103) | 68 (154) | 111 (257) |

| Coordinated | |||

| Single-entry referral only | 36 (50) | 79 (180) | 115 (230) |

| Team-based care only | 43 (103) | 63 (77) | 106 (180) |

| Fully integrated (single-entry referral and team-based care) | 36 (50) | 77 (96) | 113 (146) |

| West | |||

| Uncoordinated (market-based) | |||

| Actual (observed) | 71 (189) | 112 (385) | 183 (574) |

| Simulated | 70 (186) | 109 (350) | 179 (536) |

| Coordinated | |||

| Single-entry referral only | 62 (104) | 103 (393) | 165 (497) |

| Team-based care only | 70 (186) | 100 (100) | 170 (286) |

| Fully integrated (single-entry referral and team-based care) | 62 (97) | 101 (158) | 163 (255) |

Wait 1: the time between the date a primary care physician refers a patient to a specialist and the date of the patient’s first appointment with that specialist.

Wait 2: the interval from the date the surgeon and patient decide to proceed with surgery to the date of the surgical procedure.

Figure 2:

(A) Change in median wait time (in days) for different referral and practice models, by Ontario postal region, compared with existing practice. (B) Change in 90th percentile wait time (in days) for different referral and practice models, by Ontario postal region, compared with existing practice.

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of referral and practice models on the proportion of patients who exceeded wait-1 and wait-2 targets. Single-entry referral models alone did not reliably lead to reductions in the percentage of patients who exceeded wait times, primarily owing to a limited impact on reducing wait-2 times. Team-based care models largely prevented patients from exceeding wait-2 targets. Fully integrated models resulted in few or no patients exceeding wait-time targets, even in regions with a high proportion of patients who exceeded wait-time targets at baseline. The percentage of patients exceeding wait-1 targets in these models was 0% in all regions, and the percentage exceeding wait-2 targets was 0% except for Ontario West (2.0%, from 35.7% at baseline), East (1.1%, from 12.8% at baseline), and North (1.0%, from 25.1% at baseline).

Figure 3:

Percentage of patients exceeding the 182-day wait-1 and wait-2 targets for different referral and practice models, by Ontario postal region.

Interpretation

Our findings provide important information about the effects of different referral and practice models on wait times for joint replacement surgery in Ontario. Although single-entry referral models had a relatively small impact on overall wait times for surgery, team-based care and fully integrated models (combining single-entry referral and team-based care) had a much larger effect. The effects on high-outlier wait times was much greater than the effect on median wait times: a striking finding of our analyses was that implementation of fully integrated models could effectively prevent patients from exceeding wait-time targets for joint replacement in Ontario, without any increase in surgical capacity.

Although our findings are largely consistent with the results of other research in Canadian settings,20 the observation that single-entry referral models — one of the most popular proposed policy solutions to long wait times — had such a small effect on overall wait times was unexpected. Our analysis provides insight into why this is the case. Much of the wait time for surgical services such as joint replacement in Ontario occurs during the wait-2 period (after a surgical consultation), and single-entry referral models have a very limited impact on these wait times. In fact, single-entry models unexpectedly led to increased wait-2 times in some regional simulations, perhaps by interfering with self-regulation mechanisms that surgeons may apply in their own practices to redirect new referrals during periods when their wait-2 times are very high (e.g., surgeons with very long wait-2 times might temporarily stop accepting new referrals until their wait times shorten again — a scenario that would be exacerbated by a single-entry model referral strategy that is agnostic to fluctuations in wait-2 times).

Our results provide strong support for the implementation of both single-entry referral models and team-based care as a regional solution to the problem of long wait times for scheduled surgery in Canadian health systems, as well as an effective strategy to improve equity in access to health services. Adoption of these models will require strong leadership among health-system leaders and the active participation of surgeons. It will also require some investment in system infrastructure, instead of one-time investments to increase surgical volumes during times of crisis. Unless surgeons believe that team-based models of care are beneficial to them, as well as to other participants in the health system, and do not threaten their autonomy or opportunities for income and professional advancement, these models of care are unlikely to be viable in Canadian health systems in which physicians are highly independent and autonomous participants.21

Limitations

We studied only those patients whose priority level for joint replacement surgery was known, we assumed that orthopedic surgeons performed both hip and knee arthroplasty procedures, and we did not distinguish between priority-3 and priority-4 patients (few patients having joint replacement were categorized as priority 3). We assumed that all patients would participate in a single-entry referral model, would be able and willing to travel for surgery to any hospital within their region, and would be agreeable to having surgery by a surgeon who was not necessarily the same surgeon who performed the initial consultation. Although people may have concerns about limitations on personal choice in coordinated care models, evidence shows that these models of care are highly acceptable to patients22 and referring physicians.23 Central-intake strategies that accommodate a choice of a specific surgeon are very difficult to implement in real-world settings and result in substantially longer wait times.24 The simulations do not account for variation in outcome between different surgeons. To the extent that such variation exists, it is not clear how different referral models might affect clinical outcomes either positively or negatively. The accountability for providing a high quality of care resides with clinicians and the clinical leaders who oversee their practice. Although relying on existing referral markets to ensure high-quality care is not necessarily a helpful approach either, effects on surgical outcomes or quality of care were beyond the scope of our study. Our analyses did not account for changes in patient status while awaiting care, demographic changes, population growth, or changes in surgeons’ workloads or compensation. The simulations reflect only the outcomes that would occur in a steady state, and the short-term consequences of changing models of care can have unintended consequences, including an increase in the wait times of patients already in the system as newly arriving patients are prioritized for next-available appointments. Nevertheless, our findings provide clear insight into the potential benefits of these models of care in a mature state of implementation.

Conclusion

Our simulation of knee and hip joint replacement procedures suggests that coordinated referral and practice models have substantial potential to improve access to scheduled surgery. Single-entry referral combined with team-based models of care has the potential to effectively eliminate the problem of prolonged waits for knee and hip joint replacement in Ontario.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dionne Aleman declares a research stipend for students from the Women’s College Hospital. Nancy Baxter reports institutional grants from Global Research Partners Fund and Northwest Healthcare Properties. Jonathan Irish is vice president, clinical of Ontario Health–Cancer Care Ontario; and board member, Canadian Cancer Society. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. Pardis Seyedi, Dionne Aleman, Andrew Calzavara, Michael Carter, Scott Emerson, Samantha Lee, Julie Takata, Suting Yang, and David Urbach contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. All of the authors contributed to interpretation of data. Pardis Seyedi and David Urbach drafted the manuscript, which Dionne Aleman, Nancy Baxter, Chaim Bell, Merve Bodur, Andrew Calzavara, Robert Campbell, Michael Carter, Pieter de Jager, Scott Emerson, Jonathan Irish, Danielle Martin, Samantha Lee, Jonathan Persitz, Marcy Saxe-Braithwaite, Julie Takata, Olivia Varkul, Suting Yang, and Claudia Zanchetta reviewed critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through a Project Grant (no. PJT-166108).

Data sharing: The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Although legal data-sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., health care organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at https://www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email: das@ices.on.ca). The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors on request, understanding that the computer programs may rely on coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). This document used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal CodeOM Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from Canada Post Corporation, and/or data adapted from the Ontario Ministry of Health Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under license from ©Canada Post Corporation and Statistics Canada. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the MOH, Canadian Institute for Health Information, and Ontario Health. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES, Ontario Health, the MOH, or the MLTC is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, et al. Mirror, mirror 2017: international comparison reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health care. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2017:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin D, Miller AP, Quesnel-Vallée A, et al. Canada’s universal health-care system: achieving its potential. Lancet 2018;391:1718–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertl S. Public health care challenged in BC court. CMAJ 2016;188:E333–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell RJ, El-Defrawy SR, Bell CM, et al. Public funding for private for-profit centres and access to cataract surgery by patient socioeconomic status: an Ontario population-based study. CMAJ 2024;196:E965–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longhurst A. Failing to deliver: the Alberta Surgical Initiative and declining surgical capacity. Edmonton: Parkland Institute, University of Alberta; 2023:1–66. Available: https://www.parklandinstitute.ca/failing_to_deliver (accessed 2024 Nov. 16). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milakovic M, Corrado AM, Tadrous M, et al. Effects of a single-entry intake system on access to outpatient visits to specialist physicians and allied health professionals: a systematic review. CMAJ Open 2021;9:E413–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid M, Lee A, Urbach DR, et al. Shared care in surgery: practical considerations for surgical leaders. Healthc Manage Forum 2021;34:77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishman GS. Discrete-event simulation: modeling, programming, and analysis. New York: Springer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tagimacruz T, Cepoiu-Martin M, Marshall DA. Exploratory analysis using discrete event simulation modelling of the wait times and service costs associated with the maximum wait time guarantee policy applied in a rheumatology central intake clinic. Health Syst (Basingstoke) 2023;14:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wait Time Information System (WTIS). In: Ontario Health: Cancer Care Ontario’s Data Book — 2022–2023. Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario; updated May 2022. Available: https://ext.cancercare.on.ca/ext/databook/db2223/WTIS/WTIS-Introduction.htm (accessed 2024 Nov. 16). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn RR, Laupacis A, Austin PC, et al. Using administrative datasets to study outcomes in dialysis patients: a validation study. Med Care 2010;48:745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seyedi P, Aleman D, Baxter N, et al. Referral patterns for common surgical procedures in Ontario: a cross-sectional population-level study. Can J Surg 2024; 67:E397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price AJ, Alvand A, Troelsen A, et al. Knee replacement. Lancet 2018;392: 1672–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet 2007;370:1508–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Measuring wait times for other surgeries and procedures. Toronto: Health Quality Ontario. Available: https://www.hqontario.ca/System-Performance/Measuring-System-Performance/Measuring-Wait-Times-for-Other-Surgeries-and-Procedures (accessed 2024 Sept. 8). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armbrust M, Xin RS, Lian C, et al. Spark sql: relational data processing in spark. SIGMOD ‘15 — Proceedings of the 2015 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data; 2015 May 31–2025 June 4; Melbourne (AU). New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinney W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SCIPY 2010). 2010 June 28–July 3; Austin (TX). Proceedings of the Python in Science Conference; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross SM. Simulation. Cambridge (MA): Academic Press; 2022:1–336. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damani Z, Bohm E, Quan H, et al. Improving the quality of care with a single-entry model of referral for total joint replacement: a preimplementation/post-implementation evaluation. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro J, Axelrod C, Levy BB, et al. Perceptions of Ontario health system leaders on single-entry models for managing the COVID-19 elective surgery backlog: an interpretive descriptive study. CMAJ Open 2022;10:E789–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Heuvel B, Vair B, Porter G, et al. Patient compliance with a group model of care: the hernia clinic. Can J Surg 2012;55:259–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramchandani M, Mirza S, Sharma A, et al. Pooled cataract waiting lists: views of hospital consultants, general practitioners and patients. J R Soc Med 2002; 95:598–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall DA, Tagimacruz T, Cepoiu-Martin M, et al. A simulation modelling study of referral distribution policies in a centralized intake system for surgical consultation. J Med Syst 2022;47:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.