Abstract

Co-precipitation is a widely used technique for producing thorium-based fuels. In this method, the characteristics of the final product are significantly affected by the operating parameters. This study investigates the effects of operational parameters on the properties of thorium ThO2–30 wt%UO2 powder using oxalate precipitation. The parameters examined include the reaction temperature, stirrer type, and precipitant concentration. The results indicate that temperature, as the most important factor, has a profound effect on the size, morphology, and crystallinity of particles. Reducing the temperature produced smaller particles with a more spherical shape and increased agglomeration. Furthermore, the use of an ultrasonic stirrer doubled the particle size, whereas higher oxalic acid concentrations improved particle homogeneity and thickness. The products obtained exhibit particle sizes ranging from 0.4 to 2 μm and specific surface areas between 16 and 36 m2/g. These results demonstrate the importance of precise control over the synthesis conditions of oxalate precipitates. The optimal selection of the operating parameters can significantly improve the physical and structural properties of mixed oxide powders.

Keywords: Co-precipitation, Operational parameters, Temperature, Thorium, Uranium, Oxalate

Subject terms: Materials chemistry, Nuclear chemistry

Introduction

Thorium-based fuels have recently received several advantages over uranium, including 3 to 4 times greater abundance, higher chemical resistance, less production of minor actinides, non-applicability in nuclear weapons, and no requirement for complex and costly enrichment processes1–11. Thorium fuel is used in nuclear reactors in various forms, including metal, oxide, and carbide. Thorium dioxide fuel is used alone or in a mixture with uranium oxide12. One notable application of thorium fuel is its potential use in Generation IV nuclear reactors13,14, which promise enhanced safety and efficiency. Thorium oxide is effectively utilized as a fertile coating in Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactors (LMFBRs) and for homogenizing the initial neutron flux during the start-up of Pressurized Heavy Water Reactors (PHWRs). As a fertile material, thorium requires a fissile element such as uranium or plutonium to start nuclear fission. Consequently, the use of mixed fuels has emerged as a promising approach to effectively utilize the thorium’s benefits. Recent research has been conducted on the use of uranium–thorium mixed fuels in a Molten salt reactor (MSR)15,16, light water reactors (LWR)17, and High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor (HTGR)18.

A variety of techniques, such as sol–gel19, co-precipitation20, and hydrothermal21, are used to synthesize thorium–uranium mixed oxide powders. Among them, co-precipitation stands out due to its excellent capacity for achieving homogeneous distribution of components22. Homogeneity influences thermal properties, fission gas release during irradiation, and resistance to hotspot formation23. The other benefits of this method include processing at ambient temperatures, producing small and uniform particle size, reducing particle agglomeration, industrialization capability20.

However, there is a notable lack in the existing literature lies in the investigation of how precipitation conditions affect the properties of thorium–uranium mixed oxides. Atlas et al.24 reported that temperature of precipitation and the stirrer type had the greatest effect on fuel properties. However, they did not provide any details. White et al.25 examined the effects of calcination atmosphere, finding that powders calcined in air had a higher crystallite size, surface area, density, and lower carbon content. Kutty et al.20 concluded that the amount of U3O8 in the produced powders decreases upon calcination and sintering in air.

In this study, the oxalate co-precipitation method is examined, highlighting the critical impact of precipitation conditions on powder properties. The objective is to optimize parameters such as precipitation temperature, type of stirrer, and concentration of oxalic acid to enhance the characteristics of the resulting powders. Through careful adjustments of these operational conditions, homogeneous fine particles with a spherical morphology have been produced. Small particles allow for the elimination of the milling step and increase the specific surface area. This enhancement improves both the flowability and sinterability of the powder, which are essential for effective application in mixed oxide (MOX) fuels26–31. This study presents innovative insights into the precise control of synthesis conditions, contributing to the optimization of nuclear fuel properties. Moreover, this study comprehensively delineates the experimental procedures and thoroughly investigates the influence of various parameters on the characteristics of thorium–uranium oxide powder. The results of various analyses and performed evaluations play an essential role in elucidating how variations in synthesis conditions impact the final properties of the powder.

Experimental part

In the co-precipitation method, the precipitating agent, such as oxalic acid, ammonia, or ammonium hydroxide, is added to mixed mineral salts (such as nitrate or sulfate of metals) to precipitate simultaneously. The resulting precipitate is then calcined to produce a mixed oxide10,20,32. Recently, oxalic acid has been widely used for the production of mixed and single actinide fuels25,33–39. The method for making mixed uranium–thorium powders by co-precipitation of mixed oxalates is as follows40:

Producing precursor solutions by dissolving uranium and thorium salts in 1.5 M nitric acid

Preparing uranium for precipitation with oxalic acid (tetravalentization)

Adding oxalic acid to precipitate

Filtering and drying the resulting precipitate

Thermal or hydrothermal decomposition to convert oxalate to oxide

The co-precipitation of uranium and thorium oxalates typically begins with solutions of uranium(VI) nitrate and thorium(IV) nitrate. To achieve effective co-precipitation, uranium (VI) must be reduced to U(IV). This reduction is critical because uranium(IV) oxalate (Ksp ≈ 1 × 10⁻20)41 and thorium(IV) oxalate (Ksp ≈ 1 × 10⁻24 to 1 × 10⁻27)42 have similar and low solubility, in contrast to U(VI) oxalate. Both Th4⁺ and U4⁺ have approximately the close lattice constants (about 5.59 Å and 5.47 Å, respectively)24. Thorium oxalate is isostructural with uranium(IV) oxalate. Th(IV) and U(IV) can replace each other in the crystal structure, which has a significant impact on the formation of chemical bonds and a system’s capacity to crystallize 40.The formation of the powder morphology of the oxalates is influenced by the crystal structure and hydrogen bonds7. This structural and ionic similarity promotes the formation of homogeneous solid solutions during co-precipitation. The reduction of U(VI) to U(IV) ensures compatibility in terms of solubility and crystal lattice parameters, ultimately resulting in high-quality, uniform co-precipitates.

U(IV) is unstable in nitric acid (HNO₃) due to the acid’s strong oxidizing properties, which cause it to oxidize to U(VI) (uranyl, UO₂2⁺). To stabilize U(IV), hydrazine (N₂H₄) is used as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Hydrazine first reduces the concentration of free NO₃⁻ by neutralizing excess nitric acid and converting it into byproducts such as N₂, H₂O, and NH₃, which help prevent the oxidation of U(IV). Additionally, hydrazine enhances the thermodynamic stability of U(IV) by forming stable complexes, thereby preventing decomposition or further oxidation. Thus, hydrazine creates a reducing environment and provides chemical stabilization, enabling the practical use of U(IV) in acidic systems20,43.

The following equations are used to present the reactions of the precipitation (1) and calcination (2–4) stages20:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

Preparation procedures

Thorium nitrate, uranium nitrate, and oxalic acid were obtained from Merck, Germany. At first, a solution of uranium nitrate with a concentration of 200 g/L and an acidity of 1.5 M was prepared using nitric acid. The reduction of U(VI) to U(IV) was performed by adding hydrazine and using platinum oxide as the catalyst. The pH was kept at 2. After 24 h, the platinum oxide was separated from the solution via filtration. Next, 10 mL of uranium nitrate solution and 10 mL of thorium nitrate solution were combined. The concentration of the thorium nitrate solution was 300 g/L (in 1.5 M HNO3). The hydrazine concentration was maintained at 1 M. The final pH was approximately 1.

Oxalic acid solution with concentrations of 0.1, 0.4, and 0.8 M was prepared using distilled water. Precipitation was performed by slowly dropping oxalic acid solution into uranium–thorium nitrate solution at a rate of 1 mL/min, while the mixture was stirred using either a magnetic stirrer or an ultrasonic stirrer. For the magnetic stirrer, the stirring speed was set to 300 rpm, while the ultrasonic stirrer operated at a frequency of 40 kHz and a power output of 100 W. The oxalic acid of 0.1 M excess amount was used. The resulting slurry was stirred for 2 h by the same mixer. The precipitate was then filtered, and the resulting cake was washed more frequently with distilled water. Then, it was dried in the oven in the oven for 20 h at 328 K. The resulting powder (uranium–thorium oxalate) was calcined at 5 K/min to 973 K, with a 4 h dwell in the calcination furnace. Thermal decomposition was performed, and ThO2–(30% wt)UO2 powder was obtained. The proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowsheet for the co-precipitation method used to create ThO2–UO2 powder.

Several precipitation conditions were chosen based on the desired parameters for further investigation. The precipitation conditions are summarized in Table 1. Three different temperature levels (283, 298, and 333 K) were used for precipitation and digestion. Temperatures below 278 K caused changes in the color and state of the solution, while temperatures above 338 K led to evaporation. The 283 K temperature was maintained using an ice-water bath, and the 333 K temperature was controlled with a heater, with continuous monitoring by a thermometer. Additionally, both magnetic and ultrasonic stirrers were utilized during the precipitation and digestion stages, operating at a speed of 300 rpm and a frequency of 40 kHz, respectively. Three concentrations of oxalic acid precipitant (0.1, 0.4, and 0.8 M) were also tested.

Table 1.

Precipitation conditions for different test.

| Experiment number | Thorium concentration [g/L] | Uranium concentration [g/L] | Oxalic acid concentration [M] | Precipitation temperature [K] | Stirrer type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150 | 100 | 0.8 | 298 | Magnetic |

| 2 | 150 | 100 | 0.8 | 283 | Magnetic |

| 3 | 150 | 100 | 0.8 | 333 | Magnetic |

| 4 | 150 | 100 | 0.8 | 298 | Ultrasonic |

| 5 | 150 | 100 | 0.1 | 298 | Magnetic |

| 6 | 150 | 100 | 0.4 | 298 | Magnetic |

Experimental apparatus

To identify and investigate the powder structure, XRD patterns were obtained using a STOE STADI MP diffractometer in the 2θ range from 5 to 100°. The specific surface area, particle size, and porosity of the powder were determined through powder porosimetry analysis (BET or BJH) using a Nova 2200 device manufactured by Quantachrome Instruments. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were conducted using a ZEISS EVO 18 device to determine particle dimensions, examine the powder morphology, and analyze the material composition. A gold coating was applied to the prepared samples using an Ion-Coater (KIC-IA, COXEM) device, and the samples were subsequently examined using a scanning electron microscope (ZEISS EVO 18 Special Edition)."

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of the base sample

ThO2–30%UO2 (wt%) powder was synthesized via the co-precipitation of mixed oxalates from nitrate solutions. The optimum conditions were determined through a comprehensive review of available sources20,43 as well as a series of experiments in which the resulting data were carefully analyzed. Under these optimum conditions, a quality powder was obtained in terms of morphology, uniformity, aggregation, and particle size. These results provided a basis for comparison of other parameters. The optimal conditions were found for sample #1 (see Table 1). Precipitation was performed at ambient temperature with magnetic stirring and 0.8 M oxalic acid. The other synthesis conditions were the same as those described in the section "Preparation procedures". The results of the XRD analysis (Fig. 2) showed that all the indexed peaks are consistent with the (Th, U)O2 standard referenced in the ICDD PDF-2 database (record 01-078-0675).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the X-ray diffraction pattern of base sample (#1) with the (Th, U)O2 standard referenced in the ICDD PDF-2 database (record 01-078-0675).

The two short peaks at 21° and 23° may represent the U3O8 phase, but the other peaks do not match the U3O8 reference peaks. According to the XRD data (Fig. 3), the cell parameter is 5.5796 Å and the structure is cubic. Maud software44 was used to calculate the average crystal size and lattice strain (15 nm and 0.67%, respectively). The low lattice strain indicates that the synthesized powder exhibits suitable mechanical and electrical properties45,46. Lattice strain is likely caused by the fineness of the particles, which increases the surface effect and generates internal stresses.

Fig. 3.

XRD pattern of ThO2–30%UO2 (wt%) powder (#1).

The EDX results showed that the weight ratio of uranium to thorium was 32%. SEM/EDX analysis results are shown in Fig. 4. The SEM images supported the XRD findings: uniform particles with a cubic shape and no agglomeration. All these factors contributed to the powder’s high specific surface area (22 m2/gr). It can improve the fuel behavior and efficiency of nuclear processes by enhancing their physical properties and reactivity. The following sections examine the precipitation parameters and how they affect the quality of the powder.

Fig. 4.

SEM/EDX analysis results of ThO2–30%UO2 (wt%) powder (#1).

Effect of precipitation temperature

Precipitation temperature is one of the most significant factors influencing the end product of oxalate precipitation method7,47. To study the effect of this parameter on the characteristics of the resulting uranium–thorium oxide powder, three temperature levels (283, 298, and 333 K) were used (#1, #2, and #3—see Table 1). The digestion stage was continued for 2 h at the precipitation temperature. The remaining conditions are similar to those described in the section "Preparation procedures".

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of precipitation temperature on the powder XRD patterns. It was confirmed that all three products are uranium–thorium oxide. The highest peaks were observed at 298 K. This indicates appropriate crystallization and high homogeneity. The achievement of room temperature (298 K) as the ideal temperature is encouraging for the application of the current technique on an industrial scale. At 283 K, particle formation rates are higher than growth rates, leading to poor crystallization. This decreases the peak height due to lack of time and energy. Increasing the temperature raises the thermal energy and the reaction rate. This leads to the production of larger but heterogeneous particles. Some particles grow larger while others stay smaller because of variations in the growth rate. The heights of the diffraction peaks are averaged at this temperature. Because non-uniformity affects the quality of crystallization. Maud software44 was used to calculate the average crystals size and lattice strains (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

The effect of precipitation temperature on the powder X-ray diffraction pattern.

Table 2.

The effect of precipitation temperature on the average crystals size and lattice strains.

| Temperature [K] | Cell parameter [Å] | Crystal size [nm] | Lattice strain [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 283 | 5.5849 | 12.3 | 0.59 |

| 298 | 5.5832 | 14.1 | 0.62 |

| 333 | 5.5763 | 18.3 | 0.85 |

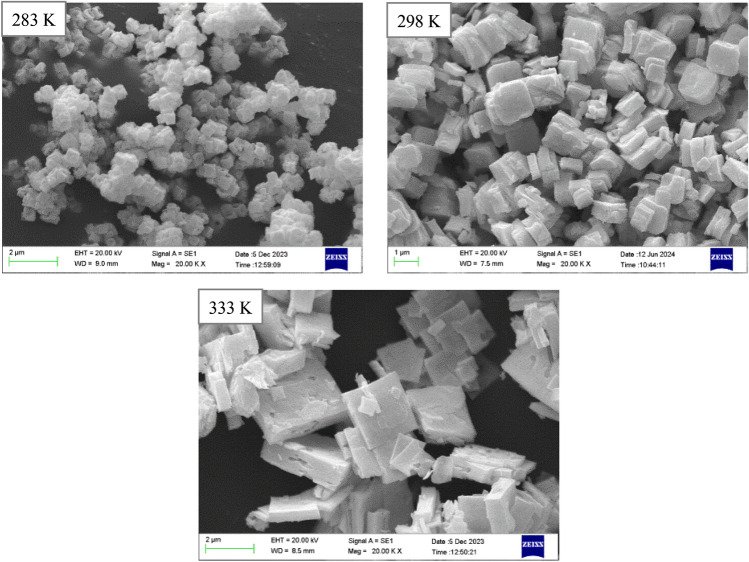

The SEM images of the synthesized powders provided complete confirmation of the XRD analysis results (Fig. 6 and Table 3). To obtain statistical information on the average size of particles, the sizes of approximately 300 particles in each sample were determined using ImageJ software48. The particle size distributions of the three samples are presented in Fig. 7. The particle size reduces with decreasing temperature. At lower temperatures, the reaction kinetics decrease. Longer precipitation times and insufficient energy for particle fusion lead to the production of finer and more stable particles. By reducing the size of the particles, surface energy rises, which causes tiny particles to stick together and agglomerate. In addition, at low temperatures, the particles tend to be slightly spherical. That is because the electrical repulsive forces are evenly distributed among the particles. The presence of spherical particles increases the flowability of the powder and fills the press machine’s mold more effectively throughout the pellet-making process.

Fig. 6.

SEM images of uranium–thorium oxide powder at different precipitation temperatures.

Table 3.

Effect of precipitation temperature on the properties of uranium–thorium oxide.

| Temperature [K] | Average particle size [µm] | Average particle thickness [µm] | Specific surface area [m2 g-1] | Pores volume [cc/g] | Pores diameter [nm] | Loss of Th–U [wt%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 283 | 0.4 | 0.15 | 35.8 | 0.052 | 3.6 | 9 |

| 298 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 33.5 | 0.050 | 3.6 | 10 |

| 333 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 15.7 | 0.024 | 3.7 | 12 |

Fig. 7.

Statistical distribution of the particle size of uranium–thorium oxide powder at different precipitation temperatures.

As the temperature rises, the particles become less homogeneous; thus, they become relatively broken cubes. At high temperatures, nanoparticles are more mobile because of their increased thermal energy. This movement may cause smaller particles to stick to larger ones more tightly. It can also lead to the formation of unstable and heterogeneous structures that negatively affect the properties of the nanoparticles.

The BET analysis of the synthesized samples (Table 3) indicated that the specific surface area increased from 15.7 to 33.5 m2/g as the temperature decreased. The reduction in particle size at low temperatures is likely responsible for increasing the number of particles and thus the available surface area. However, at 60 °C, in addition to larger particles, non-uniformity also leads to a further reduction in the specific surface area. It is noteworthy that all three powders had pores in the mesoporous area with a diameter of approximately 3.6 nm.

The amount of thorium–uranium lost during precipitation and filtration is presented in Table 3. Notably, the quantity of elements lost tends to increase with rising temperature. This trend suggests that elevated temperatures may enhance the solubility of uranium and thorium, leading to greater losses during the precipitation and filtration processes.

Effect of stirrer type

Stirring is essential for nanocrystal precipitation because it evenly distributes the starting materials, resulting in uniform particle size. It increases the contact surface between reactants, accelerates precipitation, improves reaction efficiency, and prevents particle aggregation. The type of stirrer used depends on the desired properties of the final product and the reaction conditions.

Two magnetic and ultrasonic stirrers were used during precipitation and digestion (experiments #1 and #4 —see Table 1) to examine the impact of the type of stirrer. The other conditions in the two experiments were similar, as explained in the section "Preparation procedures". The powder analysis results are summarized below.

The XRD analysis revealed that both products are uranium–thorium oxide (Fig. 8). Magnetic stirring resulted in elongated X-ray diffraction (XRD) peaks, indicating a significant increase in the crystallinity and particle uniformity. This can be attributed to the continuous, rapid, and uniform stirring of the magnetic stirrer, which resulted in better mixing and distribution of the particles in the solution. As a result, crystal growth becomes more uniform, leading to larger and more distinct XRD patterns. Maud software44 was used to calculate the average crystals size and lattice strains (Table 4).

Fig. 8.

Effect of stirrer type on the diffraction patterns of Uranium–Thorium oxide powder.

Table 4.

Effect of stirrer type on the average crystals size and lattice strains.

| Stirrer type | Cell parameter [Å] | Crystal size [nm] |

Lattice strain [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic | 5.5726 | 19.3 | 0.98 |

| Magnetic | 5.5832 | 14.1 | 0.62 |

According to the electron microscope images (Fig. 9), the ultrasonic stirrer increased the average particle size (Table 5) and decreased agglomeration and particle uniformity. There are several reasons why ultrasonic mixing alters particle size. Ultrasonic mixing uses high-frequency sound waves that transfer thermal and mechanical energy to the solution. These waves cause the formation of small bubbles and microscopic pores. The bubbles created in this process grow rapidly and then collapse in the solution because of the high pressure and temperature. This can have two effects: First, the shock waves may break the particles into smaller pieces. After that, some particles may stick together again and form larger particles. This phenomenon may occur because of the thermal and kinetic energy generated by cavitation. Another reason is the effect of temperature. In ultrasonic mixing, the temperature is continuously increased. This can increase the mobility of ions and particles, allowing them to adhere to one another and enlarge.

Fig. 9.

Effect of stirrer type on scanning electron microscopy images of uranium–thorium oxide powder.

Table 5.

Effect of stirrer type on the properties of uranium–thorium oxide powder.

| Stirrer type | Average particle size [µm] | Average particle thickness [µm] | Specific surface area [m2/g] | Pores diameter [nm] | Pores volume [cc/g] | Loss of Th–U [wt%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic | 2.0 | 0.7 | 23.0 | 3.6 | 0.032 | 10 |

| Magnetic | 1.0 | 0.4 | 33.5 | 3.6 | 0.051 | 10 |

Magnetic stirring usually creates a more homogeneous flow, resulting in a more uniform distribution of the reactants. Because the particle size remained smaller in this case, the specific surface area increased significantly because of the increased number of particles. To obtain statistical information about the average particle size, the size of approximately 300 particles in each sample was determined using ImageJ software48. The particle size distributions of both samples are shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Effect of stirrer type on the statistical distribution of particle size of uranium–thorium oxide powder.

The porosity measurement results for both products (Table 5) showed that using an ultrasonic stirrer reduced the specific surface area from 33.5 to 23.0 m2/g. The likely reason is an increase in particle size and a decrease in particle number. The pores are similar in size and are in the mesoporous range.

The quantity of thorium–uranium lost during precipitation and filtration is reported in Table 5. This data indicates that the type of agitation, whether magnetic or ultrasonic, does not significantly impact the amount of precipitation formed.

Effect of the oxalic acid concentration

The particle arrangement and dynamic aspects of precipitate formation are strongly influenced by the oxalic acid concentration. Increasing the oxalic acid concentration ( ) increases the potential for thorium–uranium oxalate formation:

) increases the potential for thorium–uranium oxalate formation:

|

5 |

The effect of precipitant concentration was studied using three different amounts of 0.1, 0.4, and 0.8 M oxalic acid (experiments #1, #5, and #6—see Table 1). The oxalic acid of 0.1 M excess amount was used. The other conditions were similar to those described in section "Preparation procedures". The analytical results of the synthesized powders are presented below.

The XRD analysis revealed that all three products are uranium–thorium oxide. Figure 11 illustrates the effect of the oxalic acid concentration on the XRD pattern of the uranium oxide powder. The lowest crystallinity was achieved at an oxalic acid concentration of 0.1 M. As the oxalate concentration rises, the diffraction patterns showed an increase in crystal organization up to a concentration of 0.8 M. This is due to the presence of more oxalate molecules in the solution, which leads to the formation of more nuclei. As a result, there are fewer structural defects in the crystals. In addition, at higher oxalic acid concentrations, stronger complexes are formed with metal ions. This treatment can prevent unwanted oxidation and phases. Maud software44 was used to calculate the average crystals size and lattice strains (Table 6).

Fig. 11.

Effect of oxalic acid concentration on the diffraction pattern of uranium–thorium oxide powder.

Table 6.

Effect of oxalic acid concentration on the average crystals size and lattice strains.

| C(Ox) [M] |

Cell parameter [Å] |

Crystal size [nm] |

Lattice strain [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 5.5782 | 16.1 | 0.68 |

| 0.4 | 5.5811 | 15.0 | 0.66 |

| 0.8 | 5.5832 | 14.1 | 0.62 |

The SEM images of the synthesized powders are shown in Fig. 12. The particle size decreased with increasing precipitant concentration. The findings are presented in Table 7. To obtain statistical information about the average particle size, the size of approximately 300 particles in each sample were determined using ImageJ software48 (Fig. 13).

Fig. 12.

Effect of oxalic acid concentration on scanning electron microscopy images of uranium–thorium oxide.

Table 7.

Effect of oxalic acid concentration on the properties of uranium–thorium oxide.

| C(Ox) [M] |

Average particle size [µm] | Average particle thickness [µm] | Specific surface area [m2/g] | Pores volume [cc/g] | Pores diameter [nm] | Loss of Th–U [wt%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 27.3 | 0.043 | 3.6 | 13 |

| 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 31.4 | 0.051 | 3.6 | 12 |

| 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 33.5 | 0.054 | 3.7 | 10 |

Fig. 13.

Statistical distribution of particle size at different oxalic acid concentrations.

At low concentrations, the nucleation process is limited to only a few primary nuclei due to the lack of oxalic acid, which causes the particle size to be larger and nonuniform. The particle thickness was also affected. As the concentration of oxalic acid increased, the thickness of the particles increased, which benefits the powder’s improved characteristics. These findings support those of Pearson et al.'s33 regarding thorium oxide production via oxalate precipitation.

BET analysis of the synthesized samples (Table 7) showed that the maximum specific surface area was related to the precipitation of 0.8 M oxalic acid and was 33.5 m2/g. This is probably due to the reduction in particle size. Changing the precipitant concentration has not much effect on the pores diameter, and the pores were all in the mesoporous area. This property indicates the stability of the porous structure of the resulting powders.

The loss of thorium–uranium during the processes of precipitation and filtration is presented in Table 7. As the concentration of oxalic acid rises from 0.1 to 0.8 M, the quantity of precipitate formed increases significantly, while the loss of thorium and uranium declines from 13 to 10%. This trend suggests that a higher concentration of oxalic acid enhances the precipitation process and boosts the efficiency of recovering these elements. The increased concentration promotes more effective formation of oxalates and stronger ionic interactions with the target metals, ultimately leading to improved separation efficiency and reduced losses.

Conclusions

In this study, uranium–thorium oxide powder was synthesized and characterized by co-precipitation of mixed oxalates. The effects of several parameters of the precipitation stage, including acid concentration, stirrer type, and precipitation temperature, were examined. The results show that the reaction temperature is the most effective parameter for precipitation. Temperature control during precipitation has a major effect on product morphology and crystallinity, in addition to particle size and homogeneity. Reduced temperature resulted in smaller particles, a more spherical form, and enhanced agglomeration.

Increasing the oxalic acid concentration resulted in improved homogeneity, smaller particles, and greater crystallinity. In addition, the particle thickness increases, and their morphology becomes perfect cubes. This increases the powder flowability.

The use of ultrasonic mixing compared to magnetic mixing leads to significant changes in the structural properties of uranium–thorium oxide. While magnetic mixing provides a small particle size and a higher specific surface area, the use of ultrasonic mixing reduces agglomeration and increases particle size because of the effects of ultrasound waves on the precipitating particles.

These results clearly demonstrate the effects of mixing methods, raw materials, and synthesis conditions on the final product properties of the oxalate precipitation method. Hence, careful control of these conditions can significantly improve the quality of the final product.

Author contributions

N.B. and F.Z.: Experiments. F.Z. and F.N: Supervision. N.B., F.N., F.Z., and T.Y.: Investigation, Writing-Original draft preparation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ferial Nosratinia, Email: F_nosrati@azad.ac.ir.

Fazel Zahakifar, Email: Fzahakifar@aeoi.org.ir.

References

- 1.Manchanda, V. K. Thorium as an abundant source of nuclear energy and challenges in separation science. Radiochim. Acta111, 243–263. 10.1515/ract-2022-0006/html (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milani, S., Zahakifar, F. & Faryadi, M. Membrane assisted transport of thorium (IV) across bulk liquid membrane containing DEHPA as ion carrier: kinetic, mechanism and thermodynamic studies. Radiochim. Acta10.1515/ract-2021-1143 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaffer, M. B. Abundant thorium as an alternative nuclear fuel: Important waste disposal and weapon proliferation advantages. Energy Policy60, 4–12. 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.04.062 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jyothi, R. K., De Melo, L. G. T. C., Santos, R. M. & Yoon, H.-S. An overview of thorium as a prospective natural resource for future energy. Front. Energy Res.11, 1132611. 10.3389/fenrg.2023.1132611 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zahakifar, F., Keshtkar, A., Souderjani, E. Z. & Moosavian, M. Use of response surface methodology for optimization of thorium (IV) removal from aqueous solutions by electrodeionization (EDI). Prog. Nucl. Energy124, 103335. 10.1016/j.pnucene.2020.103335 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wangle, T., Vleugels, J. & Cardinaels, T. Improving the Sintering Behavior of Thorium Oxide, available: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/562101 (2020).

- 7.Tyrpekl, V., Beliš, M., Wangle, T., Vleugels, J. & Verwerft, M. Alterations of thorium oxalate morphology by changing elementary precipitation conditions. J. Nucl. Mater.493, 255–263. 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2017.06.027 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lainetti, P. E. Prospective thorium fuels for future nuclear energy generation. Available: https://inis.iaea.org/records/ybvt5-wq591 (2017).

- 9.Zahakifar, F., Keshtkar, A. R. & Talebi, M. Performance evaluation of sodium alginate/polyvinyl alcohol/polyethylene oxide/ZSM5 zeolite hybrid adsorbent for ion uptake from aqueous solutions: a case study of thorium (IV). J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem.327, 65–72. 10.1007/s10967-020-07479-w (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokolov, F., Fukuda, K. & Nawada, H. Thorium fuel cycle-Potential benefits and challenges. IAEA TECDOC 1450, Available: https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TE_1450_web.pdf (2005).

- 11.Zahakifar, F. & Khanramaki, F. Continuous removal of thorium from aqueous solution using functionalized graphene oxide: study of adsorption kinetics in batch system and fixed bed column. Sci. Rep.14, 14888. 10.1038/s41598-024-65709-7 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaheri, P. & Allahyari, S. A. Investigation on the effect of operational parameters in a microreactor system on the morphology and size distribution of thorium oxalate. Nucl. Eng. Des.432, 113724. 10.1016/j.nucengdes.2024.113724 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cota-Sanchez, G., Spencer, M. S., Leeder, K., Dimayuga, I. & Bromley, B. P. Review of canadian experience with the fabrication of thoria-based fuels for advanced reactors and fuel cycles for long-term nuclear energy sustainability and security. J. Nuclear Eng. Radiat. Sci.10.1115/1.4067304 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 14.García Eslava, F. W. The Thorium fuel cycle in nuclear reactors. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/1992/75840 (2024).

- 15.Dwijayanto, R. A. P., Miftasani, F. & Harto, A. W. Assessing the benefit of thorium fuel in a once through molten salt reactor. Prog. Nucl. Energy176, 105369. 10.1016/j.pnucene.2024.105369 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu, J. et al. Transition to thorium fuel cycle on a heavy water moderated molten salt reactor by using low enrichment uranium. Ann. Nucl. Energy165, 108638. 10.1016/j.anucene.2021.108638 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du Toit, M. H., Van Niekerk, F. & Amirkhosravi, S. Review of thorium-containing fuels in LWRs. Prog. Nucl. Energy170, 105136. 10.1016/j.pnucene.2024.105136 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alang, I. & Rashid, M. Comparative analysis of uranium and thorium fuel for nuclear reactor. Future74, 83. 10.13140/RG.2.2.26987.04640 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohseni, N., Ahmadi, S., Roshanzamir, M., Najafi, M. & Mirvakili, S. Characterization of ThO2 and (Th, U) O2 pellets consolidated from NSD-sol gel derived nanoparticles. Ceram. Int.43, 3025–3034. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.096 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutty, T. et al. Characterization of ThO2–UO2 pellets made by co-precipitation process. J. Nucl. Mater.389, 351–358. 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2008.12.334 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asplanato, P. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of homogenous and size-controlled uranium-thorium oxide micro-particles for nuclear safeguards. J. Nucl. Mater.573, 154142. 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2022.154142 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bairiot, H. et al. Status and advances in mox fuel technology. Technical Report Series-International Atomic Energy Agency415, 1–179, Available: https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TRS415_web.pdf (2003).

- 23.Hours, C. et al. Dissolution of (U, Th) O2 heterogeneous mixed oxides. J. Nucl. Mater.586, 154658. 10.1016/j.jnucmat.2023.154658 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atlas, Y., Eral, M. & Tel, H. Preparation of homogeneous (Th 0.8 U 0.2) O 2 pellets via coprecipitation of (Th, U)(C2O4)2· nH2O powders. J Nucl Mater249, 46–51. 10.1016/S0022-3115(97)00185-2 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 25.White, G., Bray, L. A. & Hart, P. Optimization of thorium oxalate precipitation conditions relative to derived oxide sinterability. J. Nucl. Mater.96, 305–313. 10.1016/0022-3115(81)90574-2 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, B., Koo, Y. & Sohn, D. Nuclear fuel behaviour modelling at high burnup and its experimental support. (IAEA-TECHDOC-1233, IAEA, Vienna, Available: https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/te_1233_prn.pdf (2001).

- 27.Desfougeres, L. et al. Oxidation as an early stage in the multistep thermal decomposition of uranium (IV) oxalate into U3O8. Inorg. Chem.59, 8589–8602. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01047 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manaud, J. et al. Hydrothermal conversion of thorium oxalate into ThO2· n H2O oxide. Inorg. Chem.59, 14954–14966. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01633 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali, M. A. B. D. M. & Pauzi, A. B. M. uranium-thorium fuel mixture on reactor Triga Puspati (RTP) core kinetics by a simulation approach. Buletin Nuklear Malaysia21, available: https://www.nuklearmalaysia.org/images/BNM/2021_2025/BNM-2023_21_Oct_final-all_04.pdf (2023).

- 30.Kanrar, B., Sanyal, K., Sarkar, A. & Pai, R. V. An X-ray fluorescence and machine learning based methodology for the direct non-destructive compositional analysis of (Th1–xUx) O2 fuel pellets. J. Anal. At. Spectrom.38, 1841–1850. 10.1039/D3JA00158J (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra, S., Banerjee, J. & Panakkal, J. P. in Nuclear Fuel Cycle 81–116 (Springer, Singapore, 2023). 10.1007/978-981-99-0949-0_3. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopp, J., Novák, P., Lisníková, S., Vrba, V. & Procházka, V. Co-precipitation of Fe−Cu bimetal oxalates in an aqueous solution and their thermally induced decomposition. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2021, 3886–3895. 10.1002/ejic.202100581 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson, R., McCorkle, K., Ellison, C. & Haas, P. Preparation of ThO2 for homogeneous reactor blanket use. Oak Ridge National Lab., Tenn., Available: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/4316558, (1958).

- 34.Oktay, E. & Yayli, A. Physical properties of thorium oxalate powders and their influence on the thermal decomposition. J. Nucl. Mater.288, 76–82. 10.1016/S0022-3115(00)00571-7 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raje, N. & Reddy, A. Mechanistic aspects of thermal decomposition of thorium oxalate hexahydrate: a review. Thermochim. Acta505, 53–58. 10.1016/j.tca.2010.03.025 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abraham, F., Arab-Chapelet, B., Rivenet, M., Tamain, C. & Grandjean, S. Actinide oxalates, solid state structures and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev.266, 28–68. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.036 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walter, O. et al. AnO2 Nanocrystals via hydrothermal decomposition of actinide oxalates. 10.11159/icnnfc17.142 (2017).

- 38.Garrett, K. E. et al. First principles investigation of the structural and bonding properties of hydrated actinide (IV) oxalates, An (C2O4)2· 6H2O (An = U, Pu). Comput. Mater. Sci.153, 146–152. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.06.033 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutierrez-Chavida, A. et al. in Cristal9.

- 40.Bagheri, N., Nosratinia, F., Zahakifar, F. & Yousefi, T. The co-precipitation method in the production of thorium oxide and uranium–thorium mixed oxide fuels: a review. Nucl. Eng. Des.426, 113366. 10.1016/j.nucengdes.2024.113366 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leturcq, G., Costenoble, S. & Grandjean, S. Uranyl oxalate solubility. Available: https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/21124795 (2008).

- 42.Kobayashi, T., Sasaki, T., Takagi, I. & Moriyama, H. Solubility of thorium (IV) in the presence of oxalic and malonic acids. J. Nuclear Sci Technol.46, 1085–1090. 10.1080/18811248.2009.9711619 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balakrishna, P. ThO2 and (U, Th) O2 processing: a review. Nat. Sci.4, 943–949. 10.4236/ns.2012.431123 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 44.F., M. E. Maud: A software for the analysis of X-ray diffraction data, [Online]. Available: http://maud.ufrj.br/ (2018).

- 45.Sonia, M. M. L. et al. Effect of lattice strain on structure, morphology and magneto-dielectric properties of spinel NiGdxFe2−xO4 ferrite nano-crystallites synthesized by sol-gel route. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.466, 238–251. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.07.017 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raja, G. et al. Effect of lattice strain on structure, morphology, electrical conductivity and magneto-optical and catalytic properties of Ni-doped Mn3O4 nano-crystallites synthesized by microwave route. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.26, 101440. 10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101440 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khani M. H., A. A. G. K. Investigating parameters affecting the size and size distribution of thorium oxalate precipitate particles in a stirred reactor. Iranian Chem. Eng. J.17, 10, available: https://www.ijche.ir/article_112638.html (2018).

- 48.Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.