Abstract

Objectives

The increasing popularity and influence of the Internet in modern society have greatly impacted individuals’ lives. This population-based study elucidated the dynamic linkage between Internet use (IU) and health behaviors (HBs), particularly emphasizing the intermediary function of social participation (SP) in middle-aged and older adults (MOA) in China.

Methods

Data were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study in 2020. This study employed binary logistic regression to investigate the influence of IU on the HBs of MOA in China. Additionally, binary logistic and multiple linear regressions were used to test whether SP regulates the relationship between IU and HBs (i.e. nonsmoking, non-drinking, physical activity, and physical examination). Furthermore, the Karlson-Holm-Breen method was employed to assess the mediating role of SP.

Results

IU had a positive effect on nonsmoking (OR: 1.113, p < 0.05), physical activity (OR: 1.775, p < 0.001), and physical examination (OR: 1.226, p < 0.001). However, this study revealed that IU had a significant negative effect on non-drinking (OR: 0.775, p < 0.001). Moreover, the mediating effect analysis demonstrated that SP played a mediating role in the relationship between IU and the HBs.

Conclusion

Active engagement in social activities is an effective method for enhancing the positive impact of IU on the adoption of physical activity and physical examinations. In order to meet individuals’ needs, it is essential to design and promote Internet health services and social activities tailored to their age group and cultural background. Furthermore, greater efforts should be employed to implement public policy initiatives aimed at providing care for MOA.

Keywords: Internet use, health behaviors, social participation, middle-aged and older adults, mediation effect

Introduction

As the global demographic structure changes, the aging population has demonstrated an obvious growth trend. Globally, the proportion of individuals aged 60 and older will reach 1.4 billion by 2030. 1 By the end of 2030, the number of older adults in China is estimated to exceed 345 million. 2 Consequently, aging has emerged as a global health priority, necessitating comprehensive strategies to mitigate its associated complications. For a long time, the Chinese government has prioritized aging-related health concerns as a major strategic goal. 3 The measure to achieve this goal is to provide better services to the older adult population to improve their sense of contentment, security, and happiness. However, due to the increasing aging population, China continues to face rising healthcare costs, pension strains, and public service demands.4,5

Common issues associated with aging include hypofunction and cognitive decline. 6 Previous studies have identified health behaviors (HBs) as a crucial determinant of health status among middle-aged and older adults (MOA). HBs, such as smoking abstinence, avoiding excessive drinking, engaging in moderate physical exercise, and participating in regular physical examinations, can significantly reduce the number of multiple chronic diseases and improve the health of MOA.7–9 In addition, existing literature suggests that HBs play a key role in enabling people to gain, maintain, or improve control over their health. 10 Therefore, HBs should be considered to improve the overall health of MOA.

By June 2021, the proportion of China's netizens had reached 1.011 billion, and the percentage of individuals aged 50 years and above rose from 26.3% in December 2020 to 28.1% by June 2021. 11 As the Internet penetration rate soars, the breadth of Internet utilization among MOA progressively widens. However, acknowledging the prevalent notion that information and communication technologies (ICTs) pose greater learning hurdles for older individuals, 12 it is necessary to focus on the effects of Internet use (IU) on the health of MOA.

According to healthy lifestyle theory, living a healthy lifestyle is influenced by a person's social environment. 13 Social participation (SP) represents a pivotal avenue for older adults to access the community, fostering interpersonal exchanges and sustaining vital social ties. 14 Studies have demonstrated that SP is a key factor affecting the physical and mental health of MOA.15–17 Additionally, it is an essential part of a healthy aging strategy because it enhances social connections and reduces social isolation and loneliness. 18 Therefore, examining the health effects of SP among MOA is warranted. Hence, a meticulous examination of the health ramifications associated with social engagement among MOA is justified. This study explored the influence of IU on the HBs of MOA and analyzed the mediating effect mechanism of SP.

Literature review

Effect of Internet usage on health behavior

Many scholars have studied the influence of IU on HBs and have consistently found that Internet access facilitates health knowledge acquisition, thereby enhancing an individual's capacity for effective self-management. Specifically, Neter et al. reported that IU was prospectively associated with knowledge and preventive behaviors related to Alzheimer's disease. 19 Nam et al. focused on older couples’ HBs and found that IU was related to a higher likelihood of receiving a flu shot among wives and prostate examinations for husbands. 20 Kalichman demonstrated that IU of people living with HIV/AIDS significantly improved knowledge of HIV disease and confidence in their ability to adhere to medication. 21 Li et al. pointed out that IU has a positive impact on the self-treatment of common diseases. 22 Lee et al. found that Hispanics who actively sought health-related information online demonstrated a higher propensity for increased consumption of fruits and vegetables and greater engagement in physical activities. 23 Luo et al. showed that watching short videos enhanced the frequency of exercise among older adults. 24 De Santis et al. proved that the utilization of health apps for physical activity promotion has increased significantly. 25 Turan et al. found that the emergence of online appointment registration services, telemedicine, and online consultations enables people to enjoy medical services. 26 However, IU has also exhibited a pronounced detrimental influence on individuals’ lives, underscoring the dual-edged nature of this technological advancement, such as poor sleep quality, 27 social isolation, 28 and health deterioration due to addiction. 29 For example, Zhou et al. summarized that the use of Internet may cause irregular rest. 30 Oksanen et al. used a nationwide sample of Finnish workers and found that social media use increased the risk of drinking. 31 Duplaga similarly found that Polish older adults who use the Internet a few times a week were associated with more frequent alcohol consumption and less fruit and vegetables than nonusers. 32 Wang et al. found that IU frequency increased the probability of smoking in young Chinese adults. 33 Finally, Li et al. found that using the Internet reduced the duration and frequency of physical exercise among Chinese rural residents aged 40 and above. 34 Guo et al. revealed that “playing games” via the Internet had no impact on physical exercise. 3

The mediating role of social participation

Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory emphasizes that people have social needs. 35 SP plays an important role in reducing loneliness, meeting social needs, and improving the health of MOA, 36 and emerges as an efficacious strategy for middle-aged and older individuals to bridge the gap into society, fostering interpersonal interactions, maintaining social connections, and promoting active and healthy aging. 15 Previous research has demonstrated that older adults are more likely to participate in social activities if they use the Internet.37,38 This indicates that in the digital era, the Internet can overcome the limitations of time and space and affect individuals’ SP.14,37

Moreover, researchers regard SP as a research topic and analyze the relationship between SP and HBs. For instance, using a survey of the adult population in Finland, Nieminen et al. reported that SP was associated with HBs. 39 Wang et al. demonstrated that SP could promote Chinese MOA to do physical exercise and participate in physical examinations. 40 These studies demonstrate that SP is an important part of healthy aging, prompting MOA to become healthy.

Meanwhile, some scholars have explored whether SP plays an intermediary role between IU and HBs. A study on older adults in China found that SP may facilitate the utilization of medical services when using the Internet. 41 Chinese researchers also found that social support through the Internet contributed to smoking cessation. 42 Nevertheless, another study revealed that IU occupied the leisure time of rural residents, thereby reducing their physical exercise. 34

Although some studies have investigated the effects of IU on HBs, few have explored how SP mediates the relationship between IU and HBs among MOA. Based on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), this study not only analyzed the relationship between IU and HBs of MOA in China but also analyzed the mediating effects of SP on the association between IU and HBs (Figure 1). Using data from the 2020 CHARLS could be beneficial for reflecting on the impact of the Internet because, after the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals’ IU has become more frequent. 43 Additionally, such an analysis may allow a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between IU and HBs and provide a realistic basis for better guidance on IU to improve the quality of life of MOA.

Figure 1.

Logic framework diagram.

Methods

Data source and sample

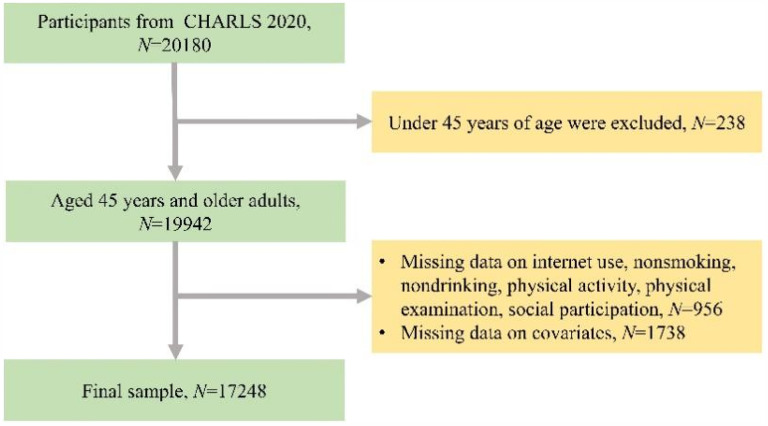

The data used in this study were obtained from the CHARLS, which is a nationally representative survey. As a national stratified probability survey, CHARLS covers 450 villages across 28 provinces, including municipalities and autonomous regions. The CHARLS aims to collect a set of microdata representing households and individuals aged 45 years and above in China. Information on demographic characteristics, health status and functioning, and healthcare and insurance was collected. All interviewees signed an informed consent form. This study utilized the 2020 CHARLS data, the latest dataset available, which time duration from July to August 2020. The nature of this study is a nationwide, cross-sectional study. Based on the research objectives, this study retained survey responses from adults aged 45 and older and eliminated those with missing values, resulting in a final sample of 17,248 individuals. The detailed study population screening process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of participants inclusion.

Variables

Dependent variable

According to the previous studies,40,44,45 HBs were assessed using questions from the questionnaire, including the following four specific dimensions:

In terms of smoking status, the question selected was, “Do you still smoke, or have you quit smoking?” The options were “still smokes,” “quit,” and “never smoked,” with “still smokes” recorded as “smoking.” Meanwhile, “quit” and “never smoked” were combined and recorded as “nonsmoking.” 40

For alcohol consumption, we chose the question, “Did you drink any alcoholic beverages, such as beer, wine, or liquor in the past year?” The response options were “drink more than once a month” and “drink but less than once a month,” which were combined into the “drinking” group. “None of these” was redefined as “non-drinking.” 46

For physical activity behavior, we selected three questions: “Do you usually do vigorous exercise for at least 10 min continuously per week,” “Do you usually do moderate exercise for at least 10 min per week,” “Do you usually do light exercise for at least 10 min per week?” These options were combined and respondents who participated in any activity were recorded as 1. Respondents who did not engage in any activities were recorded as having a 0. 40

Regarding physical examination, we chose the question, “When was the last time you had a routine medical examination since your last visit?” According to the self-reported participation frequency, participants who participated a physical examination in the past two years were classified as positive cases (code 1), while non-participants constituted the reference group (coded 0). 40

Independent variable

IU was elicited by asking respondents to answer the following question: “Have you used the Internet in the last month, including to chat, watch the news, watch videos, play games, for financial management, and others.” We redefined “no” as “non-Internet use” and assigned a value of 0, and “yes” was redefined as “Internet use” and assigned a value of 1. 22

Mediator variable

SP was the mediating variable in this study. Participants were asked whether they had engaged in eight different activities during the previous period, such as interacting with friends, playing Mahjong, and participating in a community-related organization. If an individual participated in an activity, it was recorded as 1; nonparticipation was recorded as 0. The total score ranges from 0 to 8 points. The higher the level of social activity, the higher the level of SP.

Covariates

Based on the contextual and individual characteristics of the Andersen model,44,47 we included eight covariates. The individual predisposing variables encompassed age, gender, marital status, 48 education level, 49 and residence.47 The enabling variable was health insurance. 2 The need variables were represented by self-reported health status, which was measured by the question, “Would you say your health is very good, good, fair, poor, or very poor?” The results were combined “very good” and “good” into the group of “good,” and “very poor” and “poor” into the group of “poor.” Diagnosis of a chronic disease 50 also consisted of the need variable and was represented by the answer to “Have you been diagnosed with conditions listed below by a doctor?” The 2020 CHARLS asked about 15 types of chronic diseases, including hypertension and dyslipidemia, as diagnosed by doctors. Table 1 gives a detailed explanation of the assignment of each covariant.

Table 1.

Coding of variables.

| Variables | Coding |

|---|---|

| Internet use | 1 for use, 0 for no use |

| Nonsmoking | 1 for yes, 0 for no |

| Non-drinking | 1 for yes, 0 for no |

| Physical activity | 1 for participation, 0 for non-participation |

| Physical examination | 1 for yes, 0 for no |

| Social participation | Levels of social participation (score ranges from 0 to 8), with higher scores representing greater social participation |

| Gender | 1 for male, 0 for female |

| Age | Respondent's age |

| Marital status | The value of with a spouse is 1, and the value of without a spouse is 0 |

| Education level | 1 for no formal education, 2 for elementary school, 3 for Junior high school, 4 for Senior high school and above |

| Health insurance | 1 for yes, 0 for no insurance |

| Residence | 1 for rural, 0 for urban |

| Self-reported health status | 1 for poor, 2 for fair, 3 for good |

| Chronic diseases | 1 for the presence of chronic diseases, 0 for the absence of chronic diseases |

Statistical analysis

Data analysis included five main steps. First, descriptive analyses were conducted to describe the characteristics of the participants through the mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Second, as the dependent variable was dichotomous, we used binary logistic regression to analyze the correlation between IU and HBs, including nonsmoking, non-drinking, physical activity, and physical examination. Third, to examine whether SP mediated the association between IU and HBs, we applied binary logistic regression and multiple linear regression. The primary regression models were as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Y is the dependent variable representing nonsmoking, non-drinking, physical examination, and SP. X represents IU, M represents SP, and C represents the control variables. The constant terms and coefficients of the independent variables and control variables before the addition of mediating variables are denoted as , , and , respectively (see equation (1)). , , , and represent the coefficients of the constant term, independent variable, mediator variable, and control variable, respectively, after mediating (see equation (2)). is the error term. The multicollinearity test was checked by using the correlation coefficients and the variance inflation factor (VIF) between variables. Upon analyzing correlation and VIF, we found that the variables correlate weakly with each other (see Table S1). In addition, since all VIFs are less than 10, they share no clear multicollinearity (see Table S2). Extreme outliers were checked using box plots.

Fourth, the Karlson-Holm-Breen (KHB) method was used to evaluate mediating effects. 51 Finally, there may be an endogeneity problem with the influence of IU on HBs among middle-aged and older individuals. As the choice to use the Internet is their own, this selection is non-random and is influenced by other factors, which may lead to self-selection bias. Therefore, this study used propensity score matching (PSM) to examine the effects of IU. 52 All analyses were performed using Stata version 17 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA), and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants characteristics

Table 2 illustrates the descriptive statistics, including a total of 17,248 respondents. The average age was 61.32 years old, and the majority were females (53.08%) and spouses (84.78%). Notably, 42.49% of respondents lacked formal education, lived in rural areas (60.67%), had health insurance (95.51%), or had chronic diseases (80.97%). Nearly 25% of the individuals identified their health condition as poor, whereas 24.61% reported good health status.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

| Variables | Total sample (N = 17248) |

Internet use (N = 7133) |

Non-Internet use (N = 10115) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsmoking, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 12798 (74.20) | 5198 (72.87) | 7600 (75.14) |

| No | 4450 (25.80) | 1935 (27.13) | 2515 (24.86) |

| Non-drinking, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 10926 (63.56) | 3933 (55.14) | 7029 (69.49) |

| No | 6286 (36.44) | 3200 (44.86) | 3086 (30.51) |

| Physical activity, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 15543 (90.11) | 6770 (94.91) | 8773 (86.73) |

| No | 1705 (9.89) | 363 (5.09) | 1342 (13.27) |

| Physical examination, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 7785 (45.14) | 3140 (44.02) | 4645 (45.92) |

| No | 9463 (54.86) | 3993 (55.98) | 5470 (54.08) |

| Social participation, mean (SD) | 0.80 (1.03) | 1.12 (1.20) | 0.58 (0.82) |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 8092 (46.92) | 3614 (50.67) | 4478 (44.27) |

| Female | 9156 (53.08) | 3519 (49.33) | 5637 (55.73) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 61.32 (9.33) | 56.29 (7.25) | 64.86 (9.00) |

| Marital status, N (%) | |||

| With a spouse | 14623 (84.78) | 6530 (91.55) | 8093 (80.01) |

| Without a spouse | 2625 (15.22) | 603 (8.45) | 2022 (19.99) |

| Education level, N (%) | |||

| No formal education | 7328 (42.49) | 1473 (20.25) | 5855 (57.88) |

| Elementary school | 3835 (22.23) | 1569 (22.00) | 2266 (22.40) |

| Junior high school | 3878 (22.48) | 2401 (33.66) | 1477 (14.60) |

| Senior high school and above | 2207 (12.80) | 1690 (23.69) | 517 (5.11) |

| Residence, N (%) | |||

| Rural | 10464 (60.67) | 3615 (50.68) | 6849 (67.71) |

| Urban | 6784 (39.33) | 3518 (49.32) | 3266 (32.29) |

| Health insurance, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 16474 (95.51) | 6936 (97.24) | 9538 (94.30) |

| No | 447 (4.49) | 197 (2.76) | 577 (5.70) |

| Self-reported health status, N (%) | |||

| Poor | 4311 (24.99) | 1360 (19.07) | 2951 (29.17) |

| Fair | 8692 (50.39) | 3777 (52.95) | 4915 (48.59) |

| Good | 4245 (24.61) | 1996 (27.98) | 2249 (22.23) |

| Chronic diseases, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 13966 (80.97) | 5578 (78.20) | 8388 (82.93) |

| No | 3282 (19.03) | 1555 (21.80) | 1777 (17.07) |

Additionally, the number of people using the Internet was 7133 (41.36%), with an average age of 56.29 years. Of these, 3519 (49.33%) were female, 6530 (91.55%) were married, 1473 (20.25%) had no formal education, and approximately 50% lived in rural areas. Only 2.76% of participants who used the Internet were uninsured, 19.07% rated their health status as poor, and most (78.20%) did not have a chronic disease.

Results of binary logistics regression analysis

The regression results are illustrated in Table 3 and indicate that IU is related to the HBs of MOA in China. After controlling the variables, Models 1, 3, and 4 demonstrated that IU was associated with nonsmoking (OR: 1.113, p < 0.05), physical activity (OR: 1.775, p < 0.001), and physical examination (OR: 1.226, p < 0.001). However, as seen in Model 2, after controlling for other variables, there was a significant negative correlation between IU and not drinking (OR: 0.712, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Binary logistics regression results for the Internet use and health behaviors.

| Variables | Model 1 nonsmoking OR (95%CI) |

Model 2 non-drinking OR (95%CI) |

Model 3 physical activity OR (95%CI) |

Model 4 physical examination OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet use | 1.113* (1.008, 1.229) |

0.712*** (0.654, 0.775) |

1.775*** (1.542, 2.043) |

1.226*** (1.135, 1.324) |

| Gender | 0.035*** (0.031, 0.039) |

0.143*** (0.132, 0.154) |

0.921 (0.826, 1.028) |

0.890*** (0.833, 0.950) |

| Age | 1.023*** (1.017, 1.028) |

1.020*** (1.016, 1.025) |

0.979*** (0.973, 0.985) |

1.049*** (1.045, 1.053) |

| Marital status | 1.431*** (1.254, 1.632) |

1.104 (0.990, 1.230) |

1.360*** (1.193, 1.551) |

1.201*** (1.096, 1.316) |

| Education level (ref.= no formal education) | ||||

| Elementary school | 1.186** (1.061, 1.327) |

1.047 (0.952, 1.152) |

1.279*** (1.116, 1.465) |

1.086 (0.998, 1.181) |

| Junior high school | 1.178** (1.049, 1.321) |

0.890* (0.806, 0.982) |

1.365*** (1.168, 1.597) |

1.088 (0.994, 1.190) |

| Senior high school and above | 1.593*** (1.384, 1.832) |

0.806** (0.714, 0.910) |

1.834*** (1.458, 2.307) |

1.464*** (1.310, 1.637) |

| Residence | 0.924 (0.847, 1.008) |

1.097* (1.017, 1.183) |

0.782*** (0.697, 0.877) |

0.796*** (0.745, 0.850) |

| Health insurance | 1.220 (0.991, 1.503) |

1.044 (0.876, 1.245) |

1.653*** (1.360, 2.010) |

1.474*** (1.263, 1.721) |

| Self-reported health status (ref.= poor) | ||||

| Fair | 0.796*** (0.716, 0.885) |

0.619*** (0.565, 0.677) |

1.574*** (1.397, 1.774) |

0.950 (0.880, 1.025) |

| Good | 0.904 (0.798, 1.023) |

0.577*** (0.518, 0.642) |

1.400*** (1.209, 1.622) |

1.025 (0.934, 1.124) |

| Chronic diseases | 1.360*** (1.223, 1.513) |

1.049 (0.957, 1.150) |

1.222** (1.062, 1.405) |

1.556*** (1.428, 1.695) |

| Constant | 3.231*** (2.067, 5.051) |

2.100*** (1.434, 3.076) |

9.328*** (5.551, 15.675) |

0.019*** (0.013, 0.027) |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Analysis of the mediating effect

We used multiple linear regression analyses to examine whether SP mediates the association between IU and HBs. The relationships between the dependent and mediating variables were analyzed using binary logistic regression. Before controlling for mediating variables, IU was significantly associated with HBs, as illustrated in Table 3. Model 9 (Table 4) also illustrates that IU was significantly correlated with SP.

Table 4.

Mediating effect regression results.

| Variables | Model 5 Nonsmoking OR (95%CI) |

Model 6 Non-drinking OR (95%CI) |

Model 7 Physical activity OR (95%CI) |

Model 8 Physical examination OR (95%CI) |

Model 9 Social participation Coefficients (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet use | 1.158** | 0.768*** | 1.547*** | 1.147** | 0.371*** |

| (1.047, 1.280) | (0.704, 0.837) | (1.343, 1.783) | (1.061, 1.240) | (0.018) | |

| Social participation | 0.902*** | 0.815*** | 1.671*** | 1.197*** | |

| (0.867, 0.940) | (0.786, 0.844) | (1.550, 1.802) | (1.159, 1.235) | ||

| Gender | 0.035*** | 0.139*** | 0.934 | 0.892** | −0.020 |

| (0.031, 0.039) | (0.129, 0.151) | (0.836, 1.042) | (0.835, 0.953) | (0.016) | |

| Age | 1.022*** | 1.019*** | 0.980*** | 1.050*** | −0.005*** |

| (1.017, 1.027) | (1.015, 1.024) | (0.974, 0.986) | (1.046, 1.054) | (0.001) | |

| Marital status | 1.425*** | 1.096 | 1.388*** | 1.210*** | −0.031 |

| (1.249, 1.626) | (0.983, 1.222) | (1.216, 1.584) | (1.104, 1.326) | (0.022) | |

| Education level (ref.= no formal education) | |||||

| Elementary school | 1.195** | 1.062 | 1.251** | 1.076 | 0.054** |

| (1.069, 1.337) | (0.965, 1.169) | (1.091, 1.434) | (0.988, 1.171) | (0.020) | |

| Junior high school | 1.199** | 0.919 | 1.298** | 1.06 | 0.147*** |

| (1.068, 1.346) | (0.832, 1.015) | (1.110, 1.519) | (0.969, 1.160) | (0.022) | |

| Senior high school and above | 1.654*** | 0.870* | 1.655*** | 1.373*** | 0.378*** |

| (1.436, 1.905) | (0.769, 0.984) | (1.316, 2.083) | (1.227, 1.537) | (0.027) | |

| Residence | 0.910* | 1.068 | 0.812*** | 0.813*** | −0.126*** |

| (0.834, 0.993) | (0.990, 1.152) | (0.724, 0.911) | (0.760, 0.869) | (0.016) | |

| Health insurance | 1.234* | 1.069 | 1.592*** | 1.447*** | 0.112** |

| (1.002, 1.520) | (0.896, 1.276) | (1.308, 1.938) | (1.239, 1.690) | (0.036) | |

| Self-reported health status (ref.= poor) | |||||

| Fair | 0.800*** | 0.626*** | 1.537*** | 0.937 | 0.078*** |

| (0.720, 0.890) | (0.572, 0.686) | (1.363, 1.733) | (0.867, 1.011) | (0.019) | |

| Good | 0.918 | 0.594*** | 1.348*** | 0.996 | 0.162*** |

| (0.810, 1.040) | (0.533, 0.661) | (1.163, 1.563) | (0.907, 1.093) | (0.023) | |

| Chronic diseases | 1.376*** | 1.069 | 1.193* | 1.535*** | 0.096*** |

| (1.237, 1.531) | (0.974, 1.173) | (1.036, 1.373) | (1.408, 1.672) | (0.020) | |

| Constant | 3.521*** | 2.448*** | 7.052*** | 0.016*** | 0.695*** |

| (2.248, 5.514) | (1.667, 3.595) | (4.182, 11.894) | (0.011, 0.023) | (0.081) | |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We verified the mediating effect of SP again using the KHB method. In terms of nonsmoking, the total, direct, and indirect effects are 0.108, 0.147, and −0.038, respectively, and the estimation results are significant in Table 5. The mediating effects of SP were significant for the dependent variable.

Table 5.

KHB test for social participation.

| Effect | β | SE | P | 95% CI | Mediation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Internet use–social participation–nonsmoking | ||||||

| Total effect | 0.108 | 0.051 | 0.033 | 0.009 | 0.208 | |

| Direct effect | 0.147 | 0.051 | 0.004 | 0.046 | 0.247 | |

| Indirect effect | −0.038 | 0.008 | <0.001 | −0.054 | −0.023 | −35.21 |

| Internet use–social participation–non-drinking | ||||||

| Total effect | −0.340 | 0.044 | <0.001 | −0.426 | −0.255 | |

| Direct effect | −0.264 | 0.044 | <0.001 | −0.351 | −0.178 | |

| Indirect effect | −0.076 | 0.008 | <0.001 | −0.091 | −0.061 | 22.34 |

| Internet use–social participation–physical activity | ||||||

| Total effect | 0.627 | 0.072 | <0.001 | 0.486 | 0.769 | |

| Direct effect | 0.436 | 0.072 | <0.001 | 0.295 | 0.578 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.191 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.157 | 0.224 | 30.40 |

| Internet use–social participation–physical examination | ||||||

| Total effect | 0.204 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 0.127 | 0.281 | |

| Direct effect | 0.137 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.059 | 0.215 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.067 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.053 | 0.080 | 32.71 |

PSM analysis of internet usage and health behavior

Table 6 reports that after controlling for the heterogeneity of samples between the two groups, the effects of IU on nonsmoking, non-drinking, physical activity, and physical examination were still significant.

Table 6.

Effect of Internet use on health behavior based on PSM.

| Dependent variable | Matching method | ATT | SE | T value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsmoking | K-nearest neighbor (n = 3) | 0.027 | 0.014 | 2.00 |

| Caliper matching | 0.029 | 0.012 | 2.34 | |

| Kernel matching | 0.034 | 0.011 | 3.06 | |

| Non-drinking | K-nearest neighbor (n = 3) | −0.070 | 0.015 | −4.79 |

| Caliper matching | −0.063 | 0.013 | −4.72 | |

| Kernel matching | −0.068 | 0.012 | −5.74 | |

| Physical activity | K-nearest neighbor (n = 3) | 0.034 | 0.009 | 3.61 |

| Caliper matching | 0.035 | 0.009 | 3.91 | |

| Kernel matching | 0.039 | 0.008 | 4.94 | |

| Physical examination | K-nearest neighbor (n = 3) | 0.059 | 0.015 | 3.85 |

| Caliper matching | 0.055 | 0.014 | 3.85 | |

| Kernel matching | 0.065 | 0.013 | 5.15 |

To ensure the reliability of the estimated results, a balance test was illustrated in Table 7. After matching, the SD of all covariates was < 5%. The differences between the control and treatment groups were not significant after matching. This indicates that PSM significantly reduced the difference by passing the balance test.

Table 7.

Covariates balance testing for PSM.

| Variable | Sample | Mean | Bias (%) | Reduct |bias| (%) | T-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | t | P > t | ||||

| Social participation | U | 1.119 | 0.581 | 52.4 | 35.01 | <0.001 | |

| M | 1.091 | 1.123 | −3.1 | 94.1 | −1.54 | 0.124 | |

| Gender | U | 0.507 | 0.443 | 12.8 | 8.30 | <0.001 | |

| M | 0.507 | 0.523 | −3.2 | 75.1 | −1.90 | 0.058 | |

| Age | U | 56.287 | 64.864 | −105.0 | −66.68 | <0.001 | |

| M | 56.347 | 56.300 | 0.6 | 99.4 | 0.40 | 0.690 | |

| Marital status | U | 0.915 | 0.800 | 33.5 | 21.04 | <0.001 | |

| M | 0.915 | 0.914 | 0.4 | 98.8 | 0.30 | 0.764 | |

| Education level | U | 2.604 | 1.669 | 94.7 | 62.12 | <0.001 | |

| M | 2.592 | 2.571 | 2.1 | 97.7 | 1.19 | 0.232 | |

| Residence | U | 0.507 | 0.677 | −35.2 | −22.89 | <0.001 | |

| M | 0.511 | 0.516 | −1.0 | 97.1 | −0.59 | 0.555 | |

| Health insurance | U | 0.972 | 0.943 | 14.7 | 9.21 | <0.001 | |

| M | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.00 | 0.996 | |

| Self-reported health status | U | 2.089 | 1.931 | 22.7 | 14.65 | <0.001 | |

| M | 2.086 | 2.079 | 1.0 | 95.7 | 0.59 | 0.552 | |

| Chronic diseases | U | 0.782 | 0.829 | −12.0 | −7.80 | <0.001 | |

| M | 0.781 | 0.783 | −0.3 | 97.6 | −0.16 | 0.872 | |

Discussion

Propagating health knowledge via the Internet helps cultivate health consciousness and HBs among MOA. HBs have significant implications for quality of life. This reflects the importance of active aging strategies in China. Based on a national sample of Chinese MOA from the 2020 CHARLS dataset, this study examined the mechanism by which IU significantly affects HBs, including non-drinking, nonsmoking, physical activities, and physical examination. This study further explored the mediating role of SP.

Internet usage and health behavior

Our findings confirmed that IU positively influenced nonsmoking, consistent with previous studies. For example, Peng and Chan demonstrated that IU influences smoking abstinence. 53 Liu et al. identified the Broadband China Policy as having a negative correlation with smoking behavior and smoking amount. 54 Nevertheless, Cui et al. observed overuse of the Internet in MOA impaired physiological functions, reducing energy reserves and hindering HB adoption. 55 However, there are several reasons for these contrasting findings. First, IU facilitates health knowledge dissemination through digital platforms, aligning with the Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) framework's behavioral modification principles. Second, researchers have found that greater advertising exposure is associated with a higher likelihood of cigarette use. However, according to the “Administrative Measures for Internet Advertising,” 56 China has banned online cigarette advertisements. Therefore, people in China are unlikely to be influenced by tobacco advertisements when using the Internet. Third, China has stipulated that it is not permitted to buy tobacco through the Internet, based on the “Regulation on the Implementation of the Law of the People's Republic of China on Tobacco Monopoly” 57 and the “Tobacco Monopoly Licensing Management Regulations.” 56

This study revealed that IU significantly and negatively affected non-drinking, consistent with previous findings. Finnish research found a positive correlation between participating in social media and the risk of alcohol consumption. 31 Parallel findings emerged from Belgium's alcohol-tolerant context, where alcohol exposure frequency on social media predicts self-identification as alcohol consumers. 58 There are several possible explanations for this. First, there is conflicting evidence regarding low-moderate alcohol consumption's health impacts despite established risks.59–61 Amid varying levels of health literacy, this may result in some people choosing to consume alcohol. Furthermore, as people's health literacy varies, they may not know whether the health information they are exposed to is of good quality. 62 In addition, contrasting with tobacco restrictions, older adults encounter unimpeded online alcohol marketing and purchasing channels. Additionally, this study found that MOA who use the Internet are more inclined to engage in physical activity, which is consistent with other studies. Guo et al. reported that “watching news,” “chatting,” and “watching videos” via the Internet were positively related to physical activity. 3 Wang et al. revealed that the effect of IU intensity influenced physical activity among older adults. 33 As presented on WeChat, Tik Tok or YouTube, home workouts and instructional videos by social media fitness influencers are free, easy to access online, and often do not require any equipment. This can motivate IUs to engage with this type of physical activity. 63 However, by contrast, Li et al. found that IU significantly reduced the duration and frequency of physical exercise among rural residents aged 40 and above. 34

In addition, IU was significantly and positively associated with physical examinations, aligning with existing studies. For example, Nakagomi et al. highlighted the role of the Internet in promoting health screening. 64 Xavier et al. also reported that IU contributed to participation in a cancer screening program. 65 In other words, IU has a positive impact on physical activity and physical examinations. A possible reason for this may be that information on the Internet is more abundant, which helps older adults enrich their lives. Thus, MOA can obtain exercise guidance and medical checkup information through IU, strengthening their motivation to engage in health-related activities.

Social participation as a mediating role

In this study, we found that SP negatively mediated the link between IU and nonsmoking, indicating a masking mechanism. Smoking often accompanies the gathering of people with friends and colleagues, which is seen as a way of relaxing and socializing. For example, many middle-aged Japanese men may smoke in social contexts to gain peer acceptance and social connections. 66 Offering and sharing cigarettes, is considered as a good way to make friends. 67 Based on these considerations, refusing a cigarette that another person offers can be seen as impolite and not conforming to social norms. 68 Another study found that, among previous and current smokers who had attempted to quit smoking, 90% reported that their friends had tried to prevent them from quitting by tempting them with cigarettes. 69 These social activities make nonsmoking and smoking cessation difficult. For these reasons, many countries have implemented strict smoking bans in indoor public places, such as Australia. 70 The Chinese government has also instituted smoking bans in public places; however, smoking is commonly observed in some public places that are supposed to be smoke-free, such as spaces dedicated to mahjong, chess, and poker. 68 For instance, playing mahjong is a favorite pastime of many rural people in China, while smoking is commonly undertaken among male players. It can be speculated that playing mahjong is an obstacle to smoking cessation, with the probability of smoking increases in places where many people smoke. 71 These results indicate that engaging in certain social activities is likely to increase the likelihood of smoking.

SP was found to mediate the relationship between IU and non-drinking. Specifically, IU promotes the beneficial effect of SP, thereby increasing the overall effect of IU on the probability of alcohol consumption among MOA. One study demonstrated that IU could stimulate older adults in China to participate in more social activities. 72 The main finding from a nationally representative sample of Swedish older adults was that higher levels of social activity were related to increased alcohol consumption frequency. 73 The reason for this may be that although there are significant risks associated with alcohol consumption, 74 alcohol consumption frequently occurs within a social context, especially in cultures that normalize such habits. 40 The Munich Oktoberfest, recognized as the world's largest Volksfest (popular festival), 75 serves as a significant cultural event wherein participants dress up in traditional attire and engage in alcohol consumption practices. These activities not only strengthen interpersonal bonds but also reinforce social solidarity and communal identity. Similarly, as a cultural symbol, wine is integral within familial reunion, conveys auspicious blessings, and represents aspirations for the future, thereby constituting a significant element in terms of expressing traditional family values and sociocultural etiquette practices. 76 As MOA engage in social events, such as dining with friends or family members, their chances of consuming alcohol also rise.

Furthermore, the mediating effect test results demonstrated that IU affected the physical activities of MOA by promoting social interaction, leisure, and entertainment. This is consistent with the results of previous studies.77,78 For example, square dancing is a typical social activity organized by ordinary people and carried out in public spaces. 79 It is popular among MOA in China due to its simple and interesting movements and distinctive rhythms. Dance music and movements are key points in square dancing. Currently, people can easily find their favorite dance videos via the Internet, which has fostered interest in dancing. 80 Square dancing is a nightly activity in China, conducted in housing units, squares, parks, or courtyards. 81 Finding a good dancer, especially a good friend, can offer further encouragement and help to share knowledge of the relevant movement skills involved in square dancing. This type of engagement enables MOA to find a comfortable and suitable way to engage in this activity, thereby developing regular exercise habits.

In this study, we also found that SP mediated the relationship between IU and physical examination. With the proliferation of the Internet, individuals can access health knowledge more easily. Chinese MOA tend to watch videos related to longevity and health preservation, which can lead to the development of health consciousness. 82 Studies have found that the Internet has prompted older adults to monitor their health status, engage in health maintenance, and adopt preventive HBs.20,83 Engagement in social events can furnish MOA with more social support and information resources. 40 Social platforms, such as senior colleges or community clubs, also provide opportunities to share information about community public health services. For example, Chinese adults aged 65 and older can attend free medical checkups at a community center. In addition, using the Internet can help MOA communicate better with friends or children. Therefore, the affection of family and friends could support and motivate MOA to carry out healthcare activities and cultivate a HBs, including regular medical checkups.

Based on our results, this study proposes the following recommendations: First, governments should take active measures to reduce the negative effects of IU. 84 Internet regulations should be strengthened to avoid negative and inaccurate information being presented. 85 In addition, governments should create a culture of aging-friendliness by strengthening influential infrastructure such as the Internet, parks, and activity centers. 86 Public policymakers should improve the digital literacy of MOA in various ways, and then help them to cross the “digital divide” in order to better integrate into the digital society. 87 Second, healthcare professionals should develop the physical exercise methods suitable for MOA, utilize the Internet to transmit more scientifically based fitness knowledge, and encourage active engagement in physical activity. 3 Third, communities and family members should provide sufficient help, guidance, and encouragement for MOA to use the Internet. Communities should provide Internet safety and usage training, as well as Internet operation guidance, so that MOA can master basic Internet skills. Communities could collaborate with public welfare organizations, schools, or businesses to carry out digital literacy projects through utilizing the equipment and teaching resources of such institutions to organize targeted digital literacy classes for older adults.88,89 For individuals with more limited learning abilities or special needs, one-on-one tutoring could be used, such as young people helping older adults. In addition, the content of digital literacy projects could include the use of common digital tools and applications, such as WeChat or TikTok. MOA could use these applications to communicate with family and friends and watch health science videos. Family members should be patient and guide their parents or grandparents on how to use relevant application via the Internet and on how to resolve difficulties when engaged in IU, which is likely to improve the confidence of MOA. 38 Fourth, local communities should utilize the Internet to publicize health information, which is likely to help stimulate the interest of MOA. Community workers should organize various fitness exercises, provide health education lectures on the hazards of tobacco and excessive alcohol consumption, and encourage voluntary participation and leisure activities to enrich the lives of MOA. 90

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the data used were cross-sectional. Although associations among IU, SP, and HBs were identified, causal relationships could not be conclusively established. In future studies, we will consider collecting longitudinal data. Second, IU was measured as a binary variable that failed to capture the complex dimensions of IU. It overlooked other factors, such as the frequency, type, duration, and content of IU. Therefore, future studies should select multiple indicators to define IU. Third, the effect of IU on HBs may also be influenced by other mediating variables. However, this study examined only the mediating role of SP. We plan to explore the possibility of other mediating variables, such as social status, social equity, and intergenerational relationships. Finally, according to the Andersen model, the covariates were preselected for this study. Although the factors affecting HBs are complex, some unobserved or unexplained deviations still exist. Further studies should consider adding other factors such as diverse geographic and demographic contexts.

Conclusion

This study found that IU directly affects the HBs of MOA and that SP plays an intermediary role between IU and HBs. Therefore, age- and culturally appropriate Internet health services and social activities should be designed and promoted. Public policies for caring for the middle-aged and elderly populations, including digital inclusion, community education training, and community cultural engagement, should also be robustly implemented. In conclusion, this study provides evidence for the relationship between IU and HBs of MOA in China and investigates the mediating role of SP, thus contributing to the current scientific literature. Moreover, these findings may have positive implications and valuable insights for policymakers, health promotion workers, and Internet product developers, suggesting that encouraging MOA to actively use the Internet and participate in social activities may facilitate their health.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076251346239 for The mediation effect of social participation in the relationship between Internet use and health behaviors among middle-aged and older individuals by Xinmei Yang, Yang Chen, Tuo Qiu and Xingyue Zhu in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the CHARLS team for providing the data.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Xinmei Yang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4643-2111

Ethical considerations: Ethical approval for data collection in CHARLS was obtained from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052–11015).

Author contributions: XY: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft. YC: supervision, writing—review & editing. QT: methodology. XZ: supervision, writing—review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by Fujian Health College (Grant Number MWY2025-5-01).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement: Data and documentation of CHARLS are available at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/. We have obtained permission to use the data in the study from the source (CHARLS).

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Ageing and health, https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (2022, accessed 17 August 2024).

- 2.Chen WC, Ding MJ, Wang XY. The contribution of the internet to promoting mental health for older adults: cross-sectional survey in China. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e40172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo B, Zhang XD, Zhang R, et al. The association between internet use and physical exercise among middle-aged and older adults—evidence from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 16401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He SH, Bian Y. Older adults’s hospitalizational costs and burden study in China——analysis from CHARLS data 2018. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1418179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin YH. The evolution and optimization of the policy of integrating medical care and elderly care in China. Chin Public Adm 2024; 40: 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su WQ, Lin Y, Yang LL, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of chronic diseases among the elderly in Southwest China: a cross-sectional study based on community in urban and rural areas. Prev Med Rep 2024; 44: 102799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren KX, Tao Y, Wang MH. The association between intensity-specific physical activity and the number of multiple chronic diseases among Chinese elderly: a study based on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal study (CHARLS). Prev Med Rep 2024; 41: 102714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Wang J, Yan XF. Analysis of the factors influencing chronic diseases in middle-aged and elderly men: a cross-sectional survey in China. J Men's Health 2023; 19: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang YH, Zang WB, Tian MX, et al. The impact of preventive behaviors on self-rated health, depression symptoms, and daily functioning among middle-aged and elderly Chinese: an empirical study. Plos One 2024; 19: e0305672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang LQ, Wang YL, Luo YL, et al. The mediating and moderating effect of health-promoting lifestyle on frailty and depressive symptoms for Chinese community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disorders 2024; 361: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. China Internet Network Information Center . 48th statistical report on internet development in China, https://n2.sinaimg.cn/finance/a2d36afe/20210827/FuJian1.pdf (2021, accessed 17 August 2024).

- 12.Huxhold O, Hees E, Webster NJ. Towards bridging the grey digital divide: changes in internet access and its predictors from 2002 to 2014 in Germany. Eur J Ageing 2020; 17: 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cockerham WC. Bourdieu and an update of health lifestyle theory. In: Cockerham WC. (eds) Medical sociology on the move: new directions in theory. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2013, pp.127–154. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou B, Li YM, Wang HX. Internet use and health status among older adults: the mediating role of social participation. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 1072398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He T, Huang CQ, Li M, et al. Social participation of the elderly in China: the roles of conventional media, digital access and social media engagement. Telemat Inform 2020; 48: 101347. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen WC, Yang L, Wang XY. Internet use, cultural engagement, and multi-dimensional health of older adults: a cross-sectional study in China. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 887840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding YF, Chen LS, Zhang Z. The relationship between social participation and depressive symptoms among Chinese middle-aged and older adults: a cross-lagged panel analysis. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 996606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun J, Jiang W, Li H. Social isolation and loneliness among Chinese older adults: examining aging attitudes as mediators and moderators. Front Psychol 2022; 13: 1043921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neter E, Chachashvili-Bolotin S, Erlich B, et al. Benefiting from digital use: prospective association of internet use with knowledge and preventive behaviors related to Alzheimer disease in the Israeli survey of aging. Jmir Aging 2021; 4: e25706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nam S, Han SH, Gilligan M. Internet use and preventive health behaviors among couples in later life: evidence from the health and retirement study. Gerontologist 2019; 59: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalichman SC, Benotsch EG, Weinhardt L, et al. Health-related Internet use, coping, social support, and health indicators in people living with HIV/AIDS: preliminary results from a community survey. Health Psychol 2003; 22: 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li G, Han C, Liu P. Does Internet use affect medical decisions among older adults in China? Evidence from CHARLS. Healthcare-Basel 2022; 10: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YJ, Boden-Albala B, Jia HM, et al. The association between online health information-seeking behaviors and health behaviors among hispanics in New York City: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo YF, Yu H, Kuang YL. Effects and mechanisms of TikTok use on self-rated health of older adults in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mediation analysis. Healthcare-Basel 2024; 12: 2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Santis KK, Muellmann S, Pan C, et al. Digitisation and health: second nationwide survey of internet users in Germany. Digit Health 2024; 10: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turan N, Kaya N, Aydın GÖ. Health problems and help seeking behavior at the Internet. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci 2015; 195: 1679–1682. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitazawa M, Yoshimura M, Murata M, et al. Associations between problematic Internet use and psychiatric symptoms among university students in Japan. Psychiat Clin Neuros 2018; 72: 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pénard T, Poussing N, Suire R. Does the Internet make people happier? J Socio-Econ 2013; 46: 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noh D, Kim S. Dysfunctional attitude mediates the relationship between psychopathology and Internet addiction among Korean college students: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Ment Health Nu 2016; 25: 588–597. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou YY, Bai Y, Wang J. The impact of internet use on health among older adults in China: a nationally representative study. Bmc Public Health 2024; 24: 1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oksanen A, Oksa R, Savela N, et al. Drinking and social media use among workers during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions: five-wave longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e33125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duplaga M. The association between Internet use and health-related outcomes in older adults and the elderly: a cross-sectional study. Bmc Med Inform Decis 2021; 21: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang YY, Xu J, Xie T. The association of Internet use intensity and lifestyle behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Chinese adults. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 934306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li LQ, Ding HF. Internet use, leisure time and physical exercise of rural residents-empirical analysis based on 2018 CFPS data. Lanzhou Acad J 2022; 4: 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Block M. Maslow's hierarchy of needs. In: Goldstein S, Naglieri JA. (eds) Encyclopedia of child behavior and development. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2011, pp.913–915. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu M, Yang D, Tian YH. Enjoying the golden years: social participation and life satisfaction among Chinese older adults. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1377869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du XW, Liao JZ, Ye Q, et al. Multidimensional Internet use, social participation, and depression among middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals: nationwide cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e44514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang QL, Li ZB. The impact of Internet use on the social networks of the elderly in China—the mediating effect of social participation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieminen T, Prättälä R, Martelin T, et al. Social capital, health behaviours and health: a population-based associational study. Bmc Public Health 2013; 13: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang ZY, Fang Y, Zhang XW. Impact of social capital on health behaviors of middle-aged and older adults in China-an analysis based on CHARLS2020 data. Healthcare-Basel 2024; 12: 1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang K, Dong Y, Li ZQ, et al. Current situation and related factors of internet medical service utilization among older adults in China. Med Soc 2024; 37: –9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qian YX, Gui WX, Ma FC, et al. Exploring features of social support in a Chinese online smoking cessation community: a multidimensional content analysis of user interaction data. Health Inform J 2021; 27: 1187506848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papí-Gálvez N, La Parra-Casado D. Age-based digital divide: uses of the internet in people over 54 years old. Media Commun-Lisbon 2023; 11: 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med Care 2008; 46: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu YH, Xu JQ, Gao Y, et al. The relationship between health behaviors and quality of life: the mediating roles of activities of daily living and psychological distress. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1398361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang YQ, Liu MY, Zhao SY, et al. Impact of modifiable healthy lifestyles on mortality in Chinese older adults. Sci Rep-Uk 2024; 14: 28869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang P, Jiang HL, Chen W. Health shocks and changes in preventive behaviors: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 954700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han SR, Guo JH, Xiang JJ. Is intergenerational care associated with depression in older adults? Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1325049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, Liang X. Association between WeChat use and mental health among middle-aged and older adults: a secondary data analysis of the 2020 China Family Panel Studies database. Bmj Open 2023; 13: e073553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu M, Li CY, Zhao XY, et al. The effect of internet use on depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults with functional disability: the mediating role of social isolation. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1202541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohler U, Karlson KB, Holm A. Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. Stata J 2011; 11: 420–438. [Google Scholar]

- 52.D'Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998; 17: 2265–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng YI, Chan YS. Do internet users lead a healthier lifestyle? J Appl Gerontol 2020; 39: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu YW, Liu KS, Zhang XL, et al. Does digital infrastructure improve public health? A quasi-natural experiment based on China's broadband policy. Soc Sci Med 2024; 344: 116624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cui YY, Bao HR, Xia F, et al. Peer effects of health behaviors and the moderating role of Internet use among middle-aged and older adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey in China. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1405675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People's Republic of China . Tobacco monopoly licensing management regulations, https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2016/content_5106194.htm (2016, accessed 17 August 2024).

- 57. The State Council of the People's Republic of China . Regulation on the implementation of the law of the People's Republic of China on tobacco monopoly, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-11/26/content_5653631.htm (2021, accessed 17 August 2024).

- 58.Geusens F, Beullens K. I see, therefore I am: exposure to alcohol references on Social Media, but not on traditional media, is related to alcohol consumption via drinking and non-drinking identity. Health Commun 2023; 38: 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Statescu C, Clement A, Serban IL, et al. Consensus and controversy in the debate over the biphasic impact of alcohol consumption on the cardiovascular system. Nutrients 2021; 13: 1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biddinger KJ, Emdin CA, Haas ME. Association of habitual alcohol intake with risk of cardiovascular disease. Jama Netw Open 2022; 5: E2212024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oppenheimer GM, Bayer R. Is moderate drinking protective against heart disease? The science, politics and history of a public health conundrum. Milbank Q 2020; 98: 39–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tonsaker T, Bartlett G, Trpkov C. Health information on the Internet: gold mine or minefield? Can Fam Physician 2014; 60: 407–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Durau J, Diehl S, Terlutter R. Motivate me to exercise with you: the effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of user gender. Digit Health 2022; 8: 2012837165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakagomi A, Shiba K, Kawachi I, et al. Internet use and subsequent health and well-being in older adults: an outcome-wide analysis. Comput Hum Behav 2022; 130: 107156. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xavier AJ, D'Orsi E, Wardle J, et al. Internet use and cancer-preventive behaviors in older adults: findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark 2013; 22: 2066–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee C, Gao M, Ryff CD. Conscientiousness and smoking: do cultural context and gender matter? Front Psychol 2020; 11: 1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luo MY, Ding D, Bauman A, et al. Social engagement pattern, health behaviors and subjective well-being of older adults: an international perspective using WHO-SAGE survey data. Bmc Public Health 2020; 20: 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mao AM, Yang TZ, Bottorff JL, et al. Personal and social determinants sustaining smoking practices in rural China: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health 2014; 13: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rich ZC, Hu M, Xiao SY. Gifting and sharing cigarettes in a rural Chinese village: a cross-sectional study. Tob Control 2014; 23: 496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sendall MC, Le Lievre C, McCosker LK, et al. Going smoke-free: university staff and students’ qualitative views about smoking on campus during the implementation of a smoke-free policy. Plos One 2020; 15: e0236989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harbour C. Descriptive norms and male youth smoking in rural Minya, Egypt: a multilevel analysis of household and neighborhood normative influences. Nicotine Tob Res 2012; 14: 840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang KY, Burr JA, Mutchler JE, et al. Internet use and loneliness among urban and non-urban Chinese older adults: the roles of family support, friend support, and social participation. J Gerontol B-Psychol 2024; 79: gbae081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agahi N, Dahlberg L, Lennartsson C. Social integration and alcohol consumption among older people: a four-year follow-up of a Swedish national sample. Drug Alcohol Depen 2019; 196: 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rehm J. The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health 2011; 34: 135–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flatz W, Bogner-Flatz V, Hinzmann D, et al. Economic evaluation of on-site computed tomography at Major events using data from the Munich Oktoberfest—A German and U.S. Healthcare perspective. J Clin Med 2025; 14: 2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang TH. “Village drinking ceremony” and the ritual forms of early new year festivals. Folklore Studies 2024; 4: 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ji M, Deng DT, Yang XJ. Influence of internet usage on physical activity participation among Chinese residents: evidence from 2017 China general social survey. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1293698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhong HM, Xu HB, Guo EK, et al. Can internet use change sport participation behavior among residents? Evidence from the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 837911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qu YJ, Liu ZY, Wang Y, et al. Relationships among square dance, group cohesion, perceived social support, and psychological capital in 2721 middle-aged and older adults in China. Healthcare-Basel 2023; 11: 2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hansen RK, Jochum E, Egholm D, et al. Moving together - benefits of an online dance program on physical and mental health for older women: an exploratory mixed-method study. Bmc Geriatr 2024; 24: 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peng F, Yan HJ, Sharma M, et al. Exploring factors influencing whether residents participate in square dancing using social cognitive theory: a cross-sectional survey in Chongqing, China. Medicine 2020; 99: e18685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J, Gu RX, Zhang LX, et al. How is caring for grandchildren associated with grandparents’ health: the mediating effect of internet use. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1196234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li PY, Zhang CY, Gao SL, et al. Association between daily internet use and incidence of chronic diseases among older adults: prospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e46298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang C, Zhang Y, Wang Y. A study on internet use and subjective well-being among Chinese older adults: based on CGSS (2012-2018): five-wave mixed interface survey data. Front Public Health 2024; 11: 1277789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang JY, Gao LF, Wang GJ, et al. The impact of internet use on old-age support patterns of middle-aged and older adults. Front Public Health 2023; 10: 1059346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hu YM, Gong RG, Zeng L. Neighborhood health effects on the physical health of the elderly: evidence from the CHRLS 2018. Ssm - Population Health 2022; 20: 101265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ma JQ. The causal effect of Internet use on rural middle-aged and older adults’ depression: a propensity score matching analysis. Digit Health 2025; 11: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwartz R, Borland T, Shahid M, et al. Long-term engagement in smoking cessation campaign: a mixed methods randomized trial. Plos One 2025; 20: e0318160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O Grady M, Barrett E, Connolly D. Understanding how intermediaries connect adults to community-based physical activity: a qualitative study. Plos One 2025; 20: e0318687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ji R, Chen WC, Ding MJ. The contribution of the smartphone use to reducing depressive symptoms of Chinese older adults: the mediating effect of social participation. Front Aging Neurosci 2023; 15: 1132871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076251346239 for The mediation effect of social participation in the relationship between Internet use and health behaviors among middle-aged and older individuals by Xinmei Yang, Yang Chen, Tuo Qiu and Xingyue Zhu in DIGITAL HEALTH