Abstract

Background

Pituitary apoplexy is a clinical syndrome caused by hemorrhage or ischemia of a pituitary adenoma, typically presenting with sudden-onset headache, visual disturbances, and cranial nerve palsy. Pituitary apoplexy is relatively rare in clinical practice and is often triggered by an imbalance between the high metabolic demands of pituitary adenomas and their blood supply. Ischemic injury leads to pituitary cell necrosis, resulting in hypopituitarism, which can cause systemic multi-organ dysfunction and pose significant health risks.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 73-year-old male admitted with Escherichia coli sepsis and septic shock secondary to a urinary tract infection. The patient had a history of bladder cancer and undergone bladder tumor resection one month prior, followed by intravesical chemotherapy. After initial anti-infective and glucose-lowering therapy, his condition improved. However, on the fourth day of admission, he developed a sudden headache. Further investigations revealed a sellar mass and hypopituitarism. A retrospective review of his history indicated postoperative atrial flutter and vision loss three weeks prior to admission. Pituitary apoplexy was suspected, and following infection control, the patient underwent endoscopic transnasal surgery. Pathological examination confirmed a pituitary adenoma with extensive infarction. Postoperatively, the patient’s vision improved, and he was discharged on the 25th day of hospitalization.

Conclusion

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that is often overlooked due to its nonspecific clinical manifestations. Diagnosing the condition is particularly challenging in the presence of concurrent severe infections. This case highlights the importance of carefully evaluating patients with postoperative headaches and vision changes. Cranial MRI and serum hormone testing should be considered to facilitate early diagnosis. Once confirmed, timely hormone replacement therapy and surgical intervention, when appropriate, can significantly improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: Postoperative complications, Pituitary apoplexy, Septicemia

Background

Pituitary apoplexy is a clinical syndrome caused by hemorrhage or ischemia within a pituitary adenoma. Its typical clinical manifestations include sudden-onset headache, visual disturbances, and cranial nerve palsy. Based on histopathological characteristics, pituitary apoplexy can be classified into hemorrhagic, ischemic, and mixed types. Among these, ischemic pituitary apoplexy remains relatively rare in clinical practice. From a pathogenic perspective, pituitary adenomas have high metabolic demands; therefore, any event that abruptly disrupts the balance between tumor perfusion and metabolic needs can trigger pituitary apoplexy [1]. Following its onset, pituitary cell necrosis due to ischemia may occur, ultimately leading to hypopituitarism. Hypopituitarism can result in systemic multi-organ dysfunction and cause significant harm to patients [2].

We report a case of ischemic pituitary apoplexy occurring during the recovery period following bladder tumor surgery, in which the patient subsequently developed immune dysfunction and Escherichia coli sepsis. However, the direct causal relationship between pituitary apoplexy and sepsis remains unclear. One possibility is that the patient had pre-existing subclinical pituitary dysfunction due to an underlying adenoma, and the physiological stress of systemic infection exacerbated adrenal insufficiency, ultimately precipitating pituitary apoplexy. Alternatively, postoperative sepsis may have developed independently, with the systemic inflammatory response masking the clinical manifestations of pituitary apoplexy.

This case highlights the importance of maintaining clinical vigilance for pituitary dysfunction in complex postoperative scenarios and underscores the need for multidisciplinary collaboration in managing systemic complications.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old male was admitted to our hospital for treatment of sepsis and septic shock caused by a progressive urinary tract infection due to Escherichia coli over the past five days. The patient’s main complaints included frequent urination, urgency, dysuria, and fever. Five days prior, he developed a fever (peaking at 40 °C) and sought treatment at a local hospital. Laboratory tests, including blood cultures, confirmed a Gram-negative bacterial infection (Escherichia coli). Due to a lack of improvement, the patient was transferred to our hospital for further treatment. Upon admission, his temperature was 37.8 °C, heart rate 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate 17 breaths per minute, and blood pressure 97/69 mmHg.

Review of the patient’s medical history revealed a 16-year history of bladder cancer, for which he had undergone surgical treatment at our hospital three times—16 years ago, 12 years ago, and one month prior to this admission. He had also received intravesical chemotherapy one week before admission. Additionally, the patient had a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia for several years, which had not been treated with medication or surgery. He had also been diagnosed with diabetes for over 10 years and was taking metformin hydrochloride and sitagliptin (specific dosages unknown). Although the patient’s family reported good glycemic control, his blood glucose level upon admission was 22.1 mmol/L.

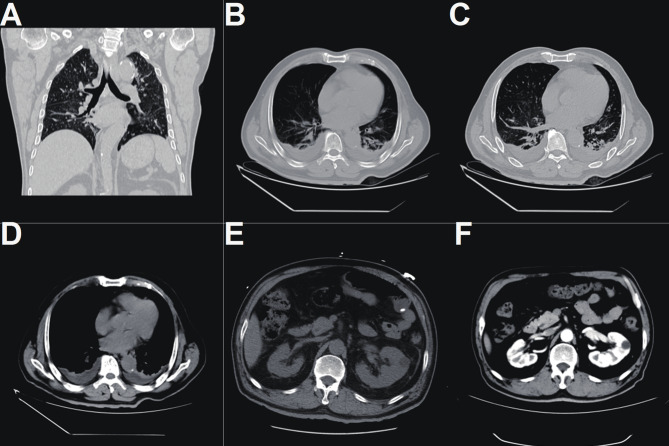

A thorough physical examination revealed abdominal distension and mild tenderness in the lower left abdomen, with no other abnormal findings. Imaging studies (chest and abdominal CT) showed: (1) Bilateral renal cysts, mild hydronephrosis and left ureteral dilation, and slight thickening of the bladder wall—indicative of postoperative changes from bladder tumor surgery; (2) Bilateral pneumonia, pleural effusion, and collapse of the lower lobes of both lungs; (3) A low-density lesion in the left hepatic lobe; and a left inguinal hernia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chest CT revealed bilateral pulmonary inflammation with pleural effusion on both sides and atelectasis in the lower lobes (A-D).Abdominal CT demonstrated a low-density lesion in the lateral segment of the left hepatic lobe, bilateral renal cysts, and mild hydronephrosis of both renal pelves and the left ureter. The bladder wall was mildly thickened, suggestive of postoperative changes following bladder tumor resection. Additionally, a left inguinal hernia was noted (E-F)

Given the patient’s history of atrial flutter during a previous hospitalization one month earlier, an electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed, but no atrial flutter or fibrillation was detected. Additional laboratory tests—including complete blood count, urinalysis, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and arterial blood gas analysis—confirmed a severe ongoing infection. Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining of the patient’s urine sample revealed fungal spores.

The chest and abdominal CT scan revealed bilateral renal cysts and mild hydronephrosis of both renal pelves and the left ureter, along with slight thickening of the bladder wall, suggestive of postoperative changes following bladder tumor surgery. Additionally, pulmonary inflammation was observed in both lungs, accompanied by bilateral pleural effusion and atelectasis of the lower lobes. A low-density lesion was identified in the lateral segment of the left hepatic lobe, and a left inguinal oblique hernia was also noted.

Considering the patient’s surgical history and diabetes, along with imaging and laboratory findings, the infectious disease specialists at our hospital initially diagnosed sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Treatment was initiated with meropenem (0.25 g/100 ml normal saline; intravenous infusion every 6 h) and linezolid (600 mg orally every 12 h) as anti-infective therapy. For the patient’s hyperglycemia, following consultation with the endocrinology department, oral hypoglycemic agents were discontinued, and insulin therapy was initiated. Regarding the patient’s history of atrial flutter, the cardiology team advised no immediate intervention.

After aggressive anti-infective treatment, the patient’s condition initially showed signs of improvement. However, on the fourth day of admission, the patient reported a headache, prompting further evaluation with cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a lumbar puncture. After discussion with the patient and his family, informed consent was obtained for the lumbar puncture. During the procedure, clear and colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected, with an opening pressure of 190 mmH₂O. Subsequent CSF analysis (Table 1) revealed elevated protein levels and increased cell counts, suggestive of possible meningitis. As a result, the initial anti-infective treatment was continued, and mannitol (100 mL, intravenous infusion every 8 h) was administered to reduce intracranial pressure. On the sixth day of admission, cranial MRI revealed a mass in the sellar region (Fig. 2). To further characterize the nature of the mass, serum hormone levels were evaluated (Table 2), revealing evidence of hypopituitarism. Given the patient’s long-standing, poorly controlled diabetes, subcutaneous insulin therapy was initiated upon admission. As a result, growth hormone (GH) levels were not assessed. The observed hormonal abnormalities also provided an explanation for the patient’s low serum levels of potassium, sodium, calcium, and magnesium (Table 3).

Table 1.

Laboratory examination results of cerebrospinal fluid

| Test indicators | Result | Normal reference value range |

|---|---|---|

| Red Blood Cell Count (/µL) | 1 | - |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 90 | 40–80 |

| Pandy’s Test | + | - |

| Neutrophils (%) | 10 | 0–6 |

| Nucleated Cell Count (/µL) | 95 | - |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 113 | 120–130 |

| Protein (g/L) | 0.927 | 0.15–0.45 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 3.5 | 2.5–4.5 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (U/L) | 38 | 10–25 |

| Adenosine Deaminase (U/L) | 2.3 | ≤ 8 |

Fig. 2.

In the T1 FLAIR sequence, the pituitary lesions show a ring-shaped high signal, and the center of the lesion is iso- or slightly low-signal (A). In the T1 enhancement, the pituitary lesions show a ring-shaped enhancement (B-C). In the T2-weighted sequence, the center of the lesion is a high signal, and the periphery of the lesion is iso-signal (D-E). This phenomenon is more obvious in the T2 FLAIR sequence (F)

Table 2.

Serum hormone level test results

| Test indicators | Result | Normal reference value range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Function Test | fT3 (pmol/L) | 3.33 | 2.43–6.01 |

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 9.09 | 9.01–19.05 | |

| TSH (mIU/mL) | 0.049 | 0.350–4.940 | |

| TPO-Ab (mIU/mL) | 28.98 | 0.00-5.61 | |

| Reproductive Hormones | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone/FSH (mIU/mL) | 1.81 | 0.95–11.95 |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) (mIU/mL) | 0.31 | 0.57–12.07 | |

| Prolactin/PRL (ng/mL) | 0.91 | 19.40-33.46 | |

| Testosterone (ng/mL) | 6.98 | 142.39-923.14 | |

| HPA Axis | Cortisol 8 a.m. (µg/dL) | 2.04 | 5.00–25.00 |

| ACTH 8 a.m. (pg/mL) | < 5.00 | 0.00–46.00 | |

| Cortisol 4 a.m. (µg/dL) | 1.11 | 5.00–25.00 | |

| ACTH 4 a.m. (pg/mL) | < 5.00 | 0.00–46.00 | |

| Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) (ng/mL) | 61.9 | 64–188 |

Table 3.

Serum electrolytes level test results

| Serum electrolytes | Result | Normal reference value range |

|---|---|---|

| K (mmol/L) | 3.4 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 131 | 137–147 |

| Cl (mmol/L) | 97 | 99–110 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 1.89 | 2.11–2.52 |

| Mg (mmol/L) | 0.69 | 0.75–1.02 |

Based on the patient’s symptoms, clinical signs, and examination results, we initially suspected that the adrenal insufficiency originated from a pituitary lesion. Although it is challenging to distinguish this from cystic lesions such as Rathke’s cleft cysts based on MRI images alone, further inquiry revealed that the patient had experienced a sudden onset of headache three weeks prior to admission, accompanied by a certain degree of visual field loss [3].

Ophthalmologic examination showed a best-corrected visual acuity of 0.05 in the right eye and finger counting at 40 cm in the left eye. The right lens exhibited cataractous changes, while an intraocular lens was present in the left eye. Fundus examination revealed a blurred view in the right eye and, in the left eye, a clear optic disc margin, flat retina, and no significant hemorrhage or exudation. Visual field testing demonstrated a quadrantic defect in the right eye, whereas the left eye could not be assessed due to poor visual acuity. Intraocular pressure measured 14 mmHg in the right eye and 11 mmHg in the left. These findings were consistent with bilateral optic neuropathy, right eye cataract, pseudophakia in the left eye, and probable compressive optic neuropathy.

Although pituitary cystic lesions can also be accompanied by symptoms such as headache and blurred vision, combined with tests such as hormone levels, we are more inclined to the possibility of pituitary stroke. After a thorough discussion with the patient and family, surgical intervention was recommended. Fully informed of the risks and benefits, the patient and family consented to the surgery. In addition to the surgical treatment, hormone replacement therapy was initiated to address the endocrine dysfunction associated with hypopituitarism, including hydrocortisone, levothyroxine. Notably, 100–200 mg of intravenous glucocorticoids were administered early to address adrenal insufficiency and prevent adrenal crisis, followed by a continuous intravenous infusion of 2–4 mg per hour, or alternatively, an initial 100 mg intramuscular bolus followed by 50–100 mg every six hours via intramuscular injection [3]. Serum hormone levels were regularly monitored to guide ongoing treatment adjustments.

Considering the patient’s recent history of Escherichia coli sepsis, the patient’s condition was reassessed. After confirming effective infection control and excluding other surgical contraindications, an endoscopic transnasal approach was undertaken on hospital day 14. Intraoperatively, a cystic-solid lesion was observed in the sellar region. Parts of the tumor appeared gray-yellow, were firm in consistency, and showed tight adhesions to the surrounding tissues. No obvious intratumoral hemorrhage or blood clots were observed during the procedure, thereby ruling out hemorrhagic pituitary apoplexy. Maximal tumor resection was achieved, and the specimen was submitted for pathological examination. Histopathological analysis, including hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry, confirmed the diagnosis of pituitary adenoma with extensive infarction (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical results were as follows: CK (pan) (-), CgA (+), Syn (+), Ki-67 (a few positive cells), reticulin staining (+), and CD56 (+).

Fig. 3.

A slightly low T1 and high T2 signal are seen in the pituitary fossa with significant enhancement at the margin. The pituitary stalk is leftward, and the sella floor shows disruption. The optic chiasm is compressed and elevated. The sphenoid sinus shows a long T1 signal without enhancement (A-E). HE staining shows pituitary adenoma with extensive infarction (F)

After surgery, the patient’s vision and visual field gradually improved. Following approximately 10 days of medication and postoperative care, the patient’s serum hormone levels began to normalize. Additionally, due to transient diabetes insipidus after surgery, oral desmopressin acetate tablets were administered as needed based on urine output to maintain fluid balance. After comprehensive treatment, the patient was discharged on the 25th day of hospitalization. Upon discharge, the patient was instructed to continue taking oral hydrocortisone and levothyroxine to maintain hormone levels and to undergo regular monitoring of serum hormone levels for timely adjustments to the treatment regimen.

Discussion

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare but potentially life-threatening clinical syndrome caused by acute hemorrhage or ischemic infarction within a pituitary adenoma [1, 4]. This process can lead to destruction of pituitary tissue, resulting in significant local compressive symptoms and endocrine dysfunction, particularly central adrenal insufficiency due to suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Among these complications, adrenal insufficiency is often the earliest to manifest and carries the highest risk [2]. Without timely diagnosis and intervention, it can progress to adrenal crisis. Thus, identifying potential causes and pathophysiological mechanisms of pituitary apoplexy is crucial for guiding appropriate clinical management.

The precise pathogenesis of pituitary apoplexy remains incompletely understood, but several internal and external precipitating factors have been identified. These include conditions such as arterial hypertension, diabetes, major surgeries (particularly coronary artery bypass grafting), and the use of antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic therapies, which increase bleeding risk. Coagulopathies, pregnancy (especially with complicated deliveries), severe hypotension, shock, head trauma, and pituitary stimulation tests using GnRH, TRH, CRH, or insulin-induced hypoglycemia also contribute to the condition. Additionally, previous radiotherapy, pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET), large non-functional pituitary tumors, aneurysm rupture, and certain medications, such as estrogens, somatostatin analogs, and dopamine agonists, may precipitate apoplexy [5–7]. However, it is notable that up to 30–40% of cases lack an identifiable trigger, suggesting a more complex interplay of pathophysiological mechanisms. Understanding these factors is crucial for guiding appropriate clinical management [8–10].

Surgical procedures and anesthesia are among the most frequently reported triggers [3]. General anesthesia, in particular, may cause hemodynamic instability such as intraoperative hypotension and postoperative hypovolemia, which can compromise perfusion of the pituitary gland, especially in the context of an existing adenoma. In the present case, the patient underwent bladder tumor resection under general anesthesia one month before admission, which may have played a contributory role in triggering ischemic infarction within the pituitary tumor.

Postoperative cardiac arrhythmias, such as atrial flutter, have also been recognized as risk factors, particularly for cerebrovascular accidents [11]. In this case, the patient developed atrial flutter the night after surgery, potentially impairing cerebral microcirculation and further exacerbating the risk of pituitary infarction.

In addition, severe infections and systemic inflammatory responses have been increasingly recognized as potential contributors to pituitary apoplexy. Systemic infections can compromise microcirculatory function and reduce cerebral perfusion, especially in metabolically active but poorly vascularized tumor tissues. Our patient developed Escherichia coli sepsis after surgery, suggesting a possible interaction between systemic infection and pituitary vulnerability. Moreover, adrenal insufficiency resulting from apoplexy may further suppress immune function, promoting a vicious cycle of immunosuppression and infection.

While the chemotherapeutic agents used in this patient were administered intravesically and did not enter systemic circulation, other medications such as anticoagulants, dopamine agonists (e.g., bromocriptine), and certain systemic chemotherapies have been implicated in the pathogenesis of pituitary apoplexy by destabilizing the tumor’s vasculature or disrupting local hemodynamics.

On a pathological level, the intrinsic characteristics of pituitary adenomas predispose them to apoplexy. Studies have demonstrated that compared with normal pituitary tissue, adenomas exhibit elevated metabolic demands, deficient angiogenesis, sparse vascular supply, and impaired autoregulation [12, 13]. This creates a precarious balance between high oxygen/nutrient demand and marginal perfusion, rendering the tumor tissue highly susceptible to ischemia or hemorrhage in the face of systemic stressors.

Clinically, the hallmark features of pituitary apoplexy include headache, visual disturbances, and cranial nerve palsy [14]. Headache is the most common presenting symptom, occurring in up to 80% of cases and often attributed to sudden sellar expansion or meningeal irritation [1]. Visual impairment and field defects, usually due to optic chiasm compression, are present in more than half of patients. Additionally, patients with pituitary apoplexy may exhibit symptoms mimicking meningitis, which can complicate clinical diagnosis [15]. However, in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, these symptoms may be subtle or misattributed [9]. In this case, the patient experienced progressive visual decline three weeks prior to admission, which was initially overlooked due to a history of cataract surgery, underscoring the importance of clinical vigilance in atypical presentations.

Therefore, in any suspected case of pituitary apoplexy, the immediate empirical administration of glucocorticoids, preferably intravenous hydrocortisone, is essential, particularly when hypotension or systemic signs of infection are present. The management of pituitary apoplexy requires a collaborative approach, integrating both endocrinological and neurosurgical expertise [16]. Therapeutic strategies for pituitary apoplexy involve two main components: (1) hormone replacement therapy, and (2) relief of local compressive symptoms.

Among the many complications, the endocrine consequences of pituitary apoplexy require special attention, with central adrenal insufficiency being the most dangerous and often the earliest manifestation. This can present as hypotension, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, fatigue, somnolence, or altered consciousness. If not promptly treated, it may rapidly lead to adrenal crisis and multiorgan failure [17].

Steroid therapy is the cornerstone of endocrine management, particularly in cases of adrenal insufficiency. The primary purpose of administering high-dose corticosteroids in pituitary apoplexy is to correct adrenal insufficiency caused by pituitary dysfunction and to prevent adrenal crisis. Pituitary apoplexy often leads to damage of the anterior pituitary, impairing the secretion of hormones, especially adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), resulting in decreased cortisol production by the adrenal glands. High-dose corticosteroids (such as intravenous hydrocortisone) are rapidly administered to replenish cortisol levels, improve blood pressure, blood glucose, and sodium levels, and prevent severe complications like hypoglycemia, hypotension, and hyponatremia. This treatment helps stabilize the patient’s condition and prevent multiorgan failure [18].

Hydrocortisone is typically administered as a 100–200 mg intravenous (IV) bolus, followed by a continuous IV infusion at a rate of 2–4 mg per hour. Alternatively, it can be given as a 100 mg intramuscular (IM) bolus, followed by IM doses of 50–100 mg every six hours. Once the acute phase has stabilized, it is recommended to taper the glucocorticoid dosage promptly to an oral regimen of 20–30 mg of hydrocortisone per day, divided into three doses [3]. In addition, regular hormone level checks are necessary.

In patients with persistent visual impairment or declining consciousness, surgical decompression via the transsphenoidal approach is the preferred method, offering effective relief with relatively low complication rates [19]. Nevertheless, the necessity of surgical intervention remains a topic of debate; some patients respond well to conservative medical therapy alone [20–23]. The optimal timing and necessity of neurosurgical intervention in pituitary apoplexy remain key areas of debate. To aid in clinical decision-making, the UK Pituitary Apoplexy Guidelines (2011) recommend using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and ophthalmologic findings to guide treatment strategies [18]. Additionally, the Pituitary Apoplexy Grading System (PAGS) classifies patients into five severity levels based on presenting symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic cases to those with visual deficits or reduced consciousness [24]. These tools help standardize management approaches and predict outcomes, as lower-grade patients tend to have better recovery of endocrine function than those with more severe presentations.

In this case, the patient was diagnosed with a pituitary tumor complicated by ischemic apoplexy, presenting with visual deficits and hormonal dysfunction. Initial treatment involved high-dose intravenous glucocorticoids and hormone replacement therapy. After stabilizing a concurrent infection, transnasal endoscopic surgery was performed, which confirmed a pituitary adenoma with extensive infarction. Postoperatively, the patient experienced improved vision and normalized hormone levels and was discharged with plans for ongoing endocrine follow-up.

In summary, pituitary apoplexy is a complex acute neuroendocrine emergency, often triggered by a combination of external stressors such as surgery, infection, cardiac arrhythmias, and medications, along with the tumor’s inherent vascular and metabolic vulnerability. Early identification of at-risk patients—particularly those undergoing surgery, those with known pituitary adenomas, or those presenting with unexplained headaches, visual changes, or hemodynamic instability—is essential. Prompt hormone replacement and appropriate neurosurgical intervention are key to improving prognosis and preventing irreversible complications.

Conclusion

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. However, it is often overlooked due to its nonspecific clinical manifestations. In clinical practice, any abnormal signs or symptoms should be carefully evaluated and not easily dismissed. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and serum hormone level testing are valuable tools in establishing a definitive diagnosis. Once diagnosed, timely hormone replacement therapy and/or surgical intervention can significantly improve patient outcomes and lead to a favorable prognosis.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the neurosurgery nursing team of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine for their efforts and hard work in the treatment of this patient!

Author contributions

Critical revision of the manuscript and supervision of the project were performed by Xinfa Pan and Renya Zhan. Clinical data were acquired by Fan Wu, Kaiyuan Huang, Jiqi Yang. The manuscript was drafted by Fan Wu, Luyuan Zhang and Chao Zhang and revised by Xinfa Pan and Renya Zhan. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Medicine and Health Technology Plan (2020ZH019) and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LGF22H160002).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The patient gave permission for his information to be used in this case report.

Consent for publication

The patient gave written informed consent permission for their clinical information and images to be published in this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fan Wu and Kaiyuan Huang are co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Renya Zhan, Email: 1196057@zju.edu.cn.

Xinfa Pan, Email: 1511052@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Briet C, Salenave S, Bonneville JF, Laws ER, Chanson P. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocr Rev. 2015;36 6:622–45. 10.1210/er.2015-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannoush ZC, Weiss RE. Hypopituitarism: emergencies. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, et al. editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, inc. Copyright © 2000–2025. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- 3.Iglesias P. Pituitary apoplexy: an updated review. J Clin Med. 2024;13:9. 10.3390/jcm13092508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witek P. Pituitary apoplexy: managing the life-threatening condition associated with pituitary adenomas. Minerva Endocrinol. 2014;39:4245–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costanza F, Cicia M, Giampietro A, Tartaglione T, Angelini F, Zoli A, et al. Pregnancy in autoimmune hypophysitis: management of a rare condition. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2024. 10.2174/0118715303314953240719044233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costanza F, Giampietro A, Mattogno PP, Chiloiro S. Colon cancer presenting as pituitary mass and hypopituitarism: recognition and multidisciplinary approach of a rare case. JCEM Case Rep. 2023;1(2):luad031. 10.1210/jcemcr/luad031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Introini L, Silva J, Risso M, Mendoza B, Pineyro MM. Microprolactinoma growth during pregnancy with pituitary tumor apoplexy: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2025;2025:2490132. 10.1155/crie/2490132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araujo-Castro M, Paredes I, Pérez-López C, García Feijoo P, Alvarez-Escola C, Calatayud M, et al. Differences in clinical, hormonal, and radiological presentation and in surgical outcomes in patients presenting with and without pituitary apoplexy. A multicenter study of 245 cases. Pituitary. 2023;26 2:250–8. 10.1007/s11102-023-01315-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordero Asanza E, Biroli A, Pérez-López C, Araujo-Castro M, Cámara R, Guerrero-Pérez F, et al. Age-Related differences in the clinical features and management of pituitary apoplexy: a cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2025. 10.1093/ejendo/lvaf056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biousse V, Newman NJ, Oyesiku NM. Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71 4:542–5. 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gula LJ, Redfearn DP, Jenkyn KB, Allen B, Skanes AC, Leong-Sit P, et al. Elevated incidence of atrial fibrillation and stroke in patients with atrial Flutter-A Population-Based study. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34 6:774–83. 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldfield EH, Merrill MJ. Apoplexy of pituitary adenomas: the perfect storm. J Neurosurg. 2015;122 6:1444–9. 10.3171/2014.10.Jns141720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner HE, Nagy Z, Gatter KC, Esiri MM, Harris AL, Wass JA. Angiogenesis in pituitary adenomas and the normal pituitary gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85 3:1159–62. 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capatina C, Inder W, Karavitaki N, Wass JA. Management of endocrine disease: pituitary tumour apoplexy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172 5:R179–90. 10.1530/eje-14-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smidt MH, van der Vliet A, Wesseling P, de Vries J, Twickler TB, Vos PE. Pituitary apoplexy after mild head injury misinterpreted as bacterial meningitis. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14 7:e7–8. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biagetti B, Cordero Asanza E, García-Feijoo P, Araujo-Castro M, Rodríguez Berrocal V, Serra G, et al. Trends and outcomes in pituitary apoplexy management: A Spanish observational multicenter study. Neurosurgery. 2024. 10.1227/neu.0000000000003281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almutairi MM, Thamer GM, Alharthi KF, Ali HJ, Ahmed AE. Pituitary apoplexy: A rare but critical emergency in neuroendocrinology. Cureus. 2025;17(1):e77970. 10.7759/cureus.77970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajasekaran S, Vanderpump M, Baldeweg S, Drake W, Reddy N, Lanyon M, et al. UK guidelines for the management of pituitary apoplexy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74 1:9–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown NJ, Patel S, Gendreau J, Abraham ME. The role of intervention timing and treatment modality in visual recovery following pituitary apoplexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurooncol. 2024;170 3:469–82. 10.1007/s11060-024-04717-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bujawansa S, Thondam SK, Steele C, Cuthbertson DJ, Gilkes CE, Noonan C, et al. Presentation, management and outcomes in acute pituitary apoplexy: a large single-centre experience from the united Kingdom. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80(3):419–24. 10.1111/cen.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almeida JP, Sanchez MM, Karekezi C, Warsi N, Fernández-Gajardo R, Panwar J, et al. Pituitary apoplexy: results of surgical and Conservative management clinical series and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:e988–99. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mamelak AN, Little AS, Gardner PA, Almeida JP, Recinos P, Soni P, et al. A prospective, multicenter, observational study of surgical vs nonsurgical management for pituitary apoplexy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(2):e711–25. 10.1210/clinem/dgad541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marx C, Rabilloud M, Borson Chazot F, Tilikete C, Jouanneau E, Raverot G. A key role for Conservative treatment in the management of pituitary apoplexy. Endocrine. 2021;71(1):168–77. 10.1007/s12020-020-02499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milazzo S, Toussaint P, Proust F, Touzet G, Malthieu D. Ophthalmologic aspects of pituitary apoplexy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1996;6 1:69–73. 10.1177/112067219600600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.