Abstract

Improving mental health outcomes for agricultural populations is dependent on understanding the unique farming related stressors in context of the local culture and community. This study was designed to assess the prevalence of stressors and mental health risks among farmers and farmworkers in a rural, medically underserved US-Mexico border region. Of 135 study respondents, 55.6% (n = 18) farmers had clinical depression symptomatology based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression screening scale (CES-D), and 40.2% (n = 117) farmworkers had stress levels that pose significant mental health risks based on the Migrant Farmworker Stress Inventory. Farmworker females were 2.3 times more likely to have a score of clinical concern. Results provide an understanding of the distinct sources of stress for both farmers and farm- workers and the mental health challenges across the industry. With an understanding that suicide is the third leading cause of injury death in Imperial County and depression associated with an increased risk of suicidality, the agricultural workforce in Imperial County is particularly vulnerable. Local farm organizations, employers, and community organizations can help increase mental health access, acceptability, and availability to achieve greater safety and health in the region’s largest workforce.

Keywords: Occupational stress, mental health, farmers, Hispanic/ Latino farmworkers, US- Mexico border

Introduction

The United States relies on the essential work provided by California’s farmers and farmworkers for national food security.1 In 2020, California produced a third of the country’s vegetables and two-thirds of the country’s fruits and vegetables.2 Imperial County, California, annually contributes more than $2 billion in agricultural sales to the overall $50 billion agriculture industry of the state.3 Imperial County is a hub of agricultural production due to its location near the US-Mexico border and mild winter temperatures. To put in perspective Imperial’s massive agricultural economic impact, in 2019 the sector contributed $12 million a day to the county’s economy- equating to $498,177 per hour and $8,303 per minute.3 Agriculture is the county’s most significant economic sector and second largest employer.3 However, despite Imperial County farmers’ and farmworkers’ critical role in securing the nation’s food supply and pillar to the local economy, they may have an increased vulnerability to mental health issues than other California agricultural workers.

Research has demonstrated that farmers and farmworkers suffer worse physical, mental, and behavioral health outcomes than other occupations in the US.4-12 To date, little research has aimed to understand the vulnerability of mental health issues between arguably the two most essential parts of the agricultural sector in Imperial County: farmers and farmworkers. We define farmers as owners or operators of farms, and farmworkers as those employed by the farm to work in the field. The main objective of this study is to utilize a mixed-methods research approach to describe agriculture-related stressors and mental health vulnerabilities among both farmers and farmworkers living and working in Imperial County. Our study centers around two research questions: (1) What percentage of farmers and farmworkers could be experiencing depression symptomatology and other mental health challenges, and (2) What are the major stressors, and how do they differ between farmers and farmworkers? This study provides a baseline of the vulnerability to mental health issues the agricultural sector experiences in a rural, US- Mexico border region.

Background and study site

Since the beginning of modern agriculture in the early 1900s, Imperial County has relied on the affordable labor provided by migrant and foreign-born workers.13 Approximately 85% of Imperial County residents are Hispanic/Latino and 30.1% of the general population were born outside of the US.14 That is more than double the foreign-born national average of 13.1%.14 Compared to other counties, Imperial County has an unusually high number of residents working in agriculture, forestry, and fishing (AFF) occupations (9.91 times higher than other counties); yet, AFF workers in the county have some of the lowest median earnings.14 In 2020, AFF occupations had a median income of $18,249, and Hispanic/Latino are the most common racial/ethnic group to live below poverty in the county.14 California farmworkers are mostly Hispanic/ Latino, and in Imperial County, approximately half of the farmworker population travels from Mexico.

In 2019, the agricultural sector employed 13,472 workers.3 Alternatively, most farmers in Imperial County are white (95%), male (81%), and over the age of 35 (90%).15 Additionally, the number of farmers is relatively small. According to the USDA, 80% of the agriculture in the Imperial Valley is on family farms, by an estimated 50–100 families.16 In California, the term “family farm” is different than in other parts of the country, and while many farms in Imperial County are owned and operated by families, they are not small at all. For example, 35% of farms in Imperial County are over 1000 acres, and generate significant profits, with 73% reporting over $100,000 value of sales in 2017.15 By acreage, the top crops produced in Imperial are forages, vegetables, field/ grass seed crops, and lettuce.15

Agriculture was one of the hardest hit sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nationally, farmers are facing significant economic burdens due to fluctuating commodity prices, lost sales, and unemployment from off-farm jobs which are often associated with healthcare to offset farm operation costs.17 While at the same time, farm- workers are experiencing significant disparities in access to vital safety net programs, disproportion- ate rates of COVID-19-related mortality, and a dramatic loss of income.18-21 Between April 2019 and April 2020, Imperial County saw an 81% increase in agricultural-related job loss.21,22 The COVID-19 mortality rate in Imperial County was more than double that of the second-highest county in the state, and more than triple the national rate.21,23 Early research has found that farmworkers’ lack of access to healthcare, low wages, poor nutrition, and underlying health issues contributed to the infection and spread of COVID-19 in the area.21-24 Furthermore, Imperial County is one of the poorest and unhealthiest places in California, making both farmers and farmworkers alike particularly vulnerable for adverse health and mental health outcomes.

Imperial County ranks the highest among California’s 58 counties for social and economic factors such as injury deaths, income inequality, unemployment, and children living in poverty.25,26 There is one mental health provider for every 713 Imperial County residents, which is more than double the statewide ratio (283:1).26 Suicide is the third leading cause of injury death in Imperial County,27 with depression and anxiety associated with an increased risk of suicidality.28 Inaccessible mental health care can significantly impact health outcomes when farmers and farmworkers are already vulnerable to high-stress levels. Working conditions and financial pressures are both known to exacerbate mental health issues by each group (farmers and farmworkers), but how those are experienced may differ. For example, weather can be a significant stressor for both Imperial County farmers and farmworkers. For farmworkers this may look like working in the field in extreme temperatures but for farmers (i.e., owners or operators), this could look like stress and anxiety about how weather will impact crop production.

Farmers and farmworkers are often distinguished by income, access to resources, educational attainment, citizenship, and racial composition. As such, it is essential to study the vulnerability to mental health issues among farmers and farmworkers in the same region to understand these challenges and make recommendations for how to better meet the mental health needs of these essential workers and provide holistic solutions. Our study aims to provide insight into how local farming associations, employers, and community organizations can help increase access, acceptability, and availability of mental health resources in a rural, medically underserved region.

Methods

Study design and procedures

A mixed-methods approach was used because it allows addressing more complicated research questions and collecting “a richer and stronger array of evidence than can be accomplished by any single method alone.”.29 Data were collected between March 2020 and August 2021, spanning the onset and continuance of the COVID-19 pandemic. Surveys included demographic data such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and the highest level of education. Mental health vulnerability measures came from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression screening scale for farmers (CES-D)30 and the Migrant Farmworker Stress Inventory (MFWSI) for farmworkers.31 Surveys were administered via Qualtrics, an online survey platform. We offered both instruments in English and Spanish. Given the established vulnerabilities inherent to each group (i.e., farmer or farmworker), the sociocultural impacts associated with mental health outcomes, and the unique makeup of Imperial County, utilizing two different measures for the different populations was warranted. Each measure is explained below.

Survey respondents for the farmworker survey were contacted by a trusted community gatekeeper, the Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition (IVEJC). Respondents were selected from the IVEJC’s database of over 3,000 Imperial County farmworkers and invited to participate in the survey via phone call or in-person effort. The survey was administered by bilingual IVEJC staff and volunteers, and respondents were provided a $10 gift card for their time. Survey respondents for the farmer survey were contracted first through presentations at local farming associations. Fliers were distributed that asked those interested to complete the online survey. Email invitations and electronic newsletter announcements with local industry stakeholders were used as additional methods to recruit farmers. Initial recruitment for farmers happened at the on-set of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020) which significantly impacted study enrollment, as we had to rely on more passive means (e.g., email, social media) to recruit participants. The San Diego State University IRB approved all study procedures and protocols (Protocol Number: HS-2021-0093; HS-2019-0310). The current study is limited to farmworkers and farmers that identified as living and working in Imperial County. Recruitment and procedures for the qualitative interviews is outlined below.

Measures

The migrant farmworker stress inventory

The MFWSI is a 39-item instrument used to measure the potential mental health effects of stressors inherent with migrant farmworkers.31 Respondents rate each item on a 5-point scale (“Have Not Experienced” to “Extremely Stressful”). The total MFWSI score is obtained by summing the scores for all the items; possible MFWSI scores range from 0–156. Higher scores mean a greater degree of stress related to the migrant farmworker lifestyle. Individual scores of 80 or more indicate the individual may have stress levels that pose significant mental health risks. Cronbach’s analysis for the MFSWI found excellent reliability (α = 94), consistent with previous studies.32,33 All farmworkers completed the MFWSI. Using the same 5-point scale, we also sought responses to two additional questions related to air quality and sleep.

The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale

The CES-D is a 20-item instrument used to measure self-reported depression symptomology experienced within the last week. The CES-D scale has a cutoff score of 16 points, meaning that a score of 16 or higher indicates the presence of symptomatology associated with clinical depression. Possible CES-D scores can range from 0–60, with higher scores indicating the presence of more symptomatology. Cronbach’s analysis for the CES- D scale found excellent reliability (α = 0.86), consistent with previous research.34,35 All farmers (i.e., owners/operators) completed the CES-D. Additionally, farmers were asked to rate their stress level on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = no stress, 4 = severe stress) on five well known and established stressors to farmers and ranchers (e.g., debt load, weather, government regulations, ability to obtain credit, and young children on the farm). These farmer stressors were selected items from the Farm Stress Survey (FSS), initially developed by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).36

Qualitative data collection

We also collected qualitative data from a subset of both farmers and farmworkers. Qualitative data collection allows research participants to express their perspectives and experiences without con- fining their answer choices, allowing for greater nuance and a more in-depth understanding. Data saturation of ≤ 5% new information has been found to be typically reached after 6–7 interviews.37 Therefore, a small sample size within each group was appropriate and effective to understand Imperial County farmers and farmworkers’ community perceptions, utilized resources, and support to cope with occupational or COVID-19 related stress. Farmworkers were selected from the IVEJC farmworker database and interviews were conducted by a bilingual and bicultural research assistant via phone. Interviewees were compensated with $40 gift cards. Farmer qualitative data was collected in the form of open-ended questions. Farmers that completed the online survey were asked to self- select to participate in the short answer questions and were compensated with $20 gift cards for completing the open-ended questionnaire. Interviews with farmers were originally planned, however due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the unknowns associated with the pandemic early on, data collection efforts shifted to a short-answer form.

Analysis

We conducted analyses using SPSS 27 statistical software program. First, we performed univariate analyses to summarize sample characteristics. Second, bivariate analyses (e.g., chi squares) were used to examine associations between demographic variables (e.g., gender, farm role) and mental health risk scores. The CES-D and MFWSI both have cutoff scores, 16 and 80, respectively, that indicate the individual is experiencing high levels of depression symptomology or stress levels that pose mental health risks. Thus, in our analysis, we utilized these cutoff scores instead of the continuous variable to understand farmers and farmworkers ' vulnerabilities to mental health issues more effectively. We dichotomized the sum totals for the CES-D and MFWSI as we anticipated the summed scores from the CES-D and MFWSI to be highly skewed and not easily transformable to normality. Simple logistic regression was conducted to see how attribute variables predicted scores of clinical concern.

Qualitative data was collected through a short- answer form (farmers) or a key informant interview (farmworkers). Qualitative farmer answers were compiled and uploaded into a word processing program in which a meta-matrix was constructed to record the extracted information from each respondent. Farmworker interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated from Spanish to English by a bilingual and bicultural research assistant. Farmworker interviews were compiled and uploaded into NVivo 12 for analysis. A procedure of cross-case analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data to identify themes that cut across all cases in both the farmer and farmworker groups,38,39; however, the in-depth analysis for farmer and farmworker qualitative data was also conducted separately.

Results

This mixed-methods study included quantitative surveys of farmers (n = 18) and farmworkers (n = 117), and qualitative data collection from farmers (n = 6) and farmworkers (n = 6) in Imperial County, California

Characteristics of study participants

Survey participants’ sociodemographic information is presented in Table 1. The majority of research participants (87%, n = 117) were farm-workers, and 13% (n = 18) were owners or operators of farms. Most of the participants identified as male (57.8%, n = 78) and were an average age of 46.7 years old. Most of all, farmers and farmworkers (77.8%, n = 105) had a high school degree or less. Among farmers, 66% (n = 11) reported graduating from college or technical school, while only 9% (n = 16) of farmworkers were college graduates. All farmworkers were Spanish-speaking and identified as Hispanic/Latino. Of the farmers, two identified as white, one identified as Hispanic/ Latino, and data are missing for 15 farmers.

Table 1.

Survey respondents’ sociodemographic variables for farmers (N = 18) and farmworkers (N = 117).

| Variables | All respondents N(%)/M(SD) |

Farmers | Farmworkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 78 (57.8%) | 16 (89%) | 62 (53%) |

| Female | 57 (42.2%) | 2 (11%) | 55 (47%) |

| Age (SD) | 46.7 (13.5) | 47 (15.4) | 46.6 (13.3) |

| Language for Survey | |||

| Spanish | 119 (88.1%) | 2 (11%) | 117 (100%) |

| English | 16 (11.9%) | 16 (88.9%) | - |

| Farm Role | |||

| Farmer | 18 (13.3%) | - | - |

| Farmworker | 117 (86.7%) | - | - |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 118 (87.4%) | 1 (6%) | 117 (100%) |

| White | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (11%) | - |

| Missing | 15 (11.1%) | 15 (83%) | - |

| Education | |||

| No formal schooling | 4 (3%) | - | 4 (3%) |

| Elementary school | 8 (5.9%) | - | 8 (7%) |

| Middle school | 48 (35.6%) | - | 48 (41%) |

| High school | 45 (33.3%) | 4 (22%) | 41 (35%) |

| Some college | 10 (7.4%) | 3 (17%) | 7 (6%) |

| College graduate | 18 (13.3%) | 9 (50%) | 9 (8%) |

| Technical schools | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (11%) | - |

Farm-related stressors

In this section, we provide results of major stressors for both farmworkers and farmers. Additionally, we discuss crosscutting stressors that affect farmers and farmworkers alike and were highlighted in both the quantitative and qualitative data.

Farmworkers survey results

Farmworkers were asked to rate items associated with the migrant farmworker lifestyle on a 5-point scale (“Have Not Experienced” to “Extremely Stressful”). Table 2 lists the mean, standard deviation (SD), and skewness of the top seven stressors experienced among the farmworker sample. The highest perceived stressor was difficulty being away from family members (M = 3.18, SD = 1.16), with not getting enough sleep (M = 3.10; SD = 1.13) and weather (M = 3.09, SD = 1.20) as the second and third highest perceived stressors.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviation, and skewness for farmworker stressors.

| Stressor | Mean | SD | Skewness | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Away from family members | 3.18 | 1.16 | −.700 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Not enough sleep | 3.10 | 1.13 | −.538 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Weather | 3.09 | 1.20 | −.576 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Work long hours | 3.02 | 1.21 | −.508 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Air at work is not clean | 2.91 | 1.28 | −.150 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Communicating in English language | 2.88 | 1.30 | −.180 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Drug use by others | 2.83 | 1.34 | −.252 | 1.0–4.0 |

Farmers survey results

Farmers were asked to indicate the level of stress weather, government regulations, youth on the farm, debt load, and ability to obtain credit has in managing their farm operation. The highest perceived stressor was government regulations and policies (M = 3.39, SD = .778), with weather (M = 2.50, SD = .924) and debt load (M = 2.50, SD = .924) the second highest perceived stressors. Table 3 lists the mean, standard deviation (SD), and skewness of the five key stressors.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviation, and skewness for farmer stressors.

| Stressor | Mean | SD | Skewness | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government regulations and policies | 3.39 | .778 | −1.67 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Debt load | 2.50 | .924 | −.252 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Weather | 2.50 | .924 | −.252 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Ability to obtain credit | 2.22 | .808 | −.451 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Young children on the farm | 2.12 | .928 | .276 | 1.0–4.0 |

Farmworker safety and health

In addition to the survey results, qualitative data highlighted that both farmers and farmworkers experienced concerns associated with farmworker injury and illness. For example, a farmer participant expressed concern for the health and safety of their workforce, sharing, “workers getting hurt stresses me out.” Another farmer shared that “there is not much support for the people who work in the field” when asked what is particularly frustrating about being a farmer in the region. Concern for farm-related injuries and illnesses was also found within farmworkers, with several farmworker participants sharing the physical nature of the work triggers preexisting physical injuries (e.g., “wear and tear on my knees”) and the nature of farm labor (e.g., unable to socially distance from other workers) increases concern of contracting and transmitting COVID-19. Moreover, these concerns were amplified by farmworkers expressing the lack of comprehensive health insurance.

Working in extreme weather

Another cross-cutting stressor was the weather, as it scored high on the survey for both farmers and farmworkers. This was also indicated by the quantitative results of the top stressors experienced as described above. Farmworkers cited working in extreme temperatures and rain. Given the extreme heat, much farm work starts in the early morning hours, which can sometimes be quite cold. A farmworker shared that “you start getting stressed out because you work under all extreme weather, sometimes hot, sometimes cold, sometimes it’s raining, sometimes chilly.” However, despite these challenges, other farmworkers did indicate that they enjoy working outside versus “being cooped up inside.” Farmers voiced similar concerns and asked what was particularly difficult about being a farmer in the area; one farmer stated, “The heat is very intense in the summer.”

Farm-home life balance

Long working hours, fatigue, and the physical nature of the work were viewed as factors that impacted farmers’ and farmworkers’ personal lives. One farmer shared, “the long hours and physically demanding work leave me very tired when coming home to my young children and my wife who also works outside of the home.” Similarly, a farmworker shared about fieldwork impacting their family, “I’m not here. I am always at work; I go out in the early morning and return in the evening.” Moreover, participants indicated feeling fatigued because an irregular sleep schedule accompanies the work. Farmworkers further explained this concern as being necessary due to the significant hot weather experienced in the region.

Mental health risks

Approximately 42.2% of participants had scores of clinical concern. For farmers, 55.6% had a CES-D score of 16 or more, and for farmworkers 40.2% had a MFWSI score of 80 or more.

Farmworkers

Chi-square analysis.

A chi-square test (i.e., Spearman’s rho) for association was conducted between gender and having a clinically significant score. All expected frequencies were greater than five. There was a statistically significant association between gender and having a clinically significant score, x2 = 4.98, df = 1, N = 117, p = .026. Table 4 shows the Pearson chi-square results and indicates that male and female farmworkers are significantly different whether they have scores above or at the cutoff score. Females are more likely to have scores at or above the clinically significant cutoff score than males. There were no statistically significant associations in having a clinically significant cutoff score and education, x2 = 0.09, df = 1, N = 117, p = .334 or age, x2 = .080, df = 1, N = 117, p = .391 among farmworker participants.

Table 4.

Chi-square analysis of prevalence of clinically significant scores among male and female farmworkers.

| Variable | N (%) | Males (%) | Female (%) | x2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores of Clinical Concern Above the cutoff score | 47 (40.2%) | 19 (30.6%) | 27 (49.1%) | 4.98 | .026 |

| Below the cutoff score | 70 (59.8%) | 43 (69.4%) | 28 (50.9%) | ||

| Totals | 117 | 62 | 55 |

Logistic regression analysis.

A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of gender on the likelihood that farmworkers had clinically significant cutoff scores. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, x2(1) = 5.00, p = .025. The model explained 5.7% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in clinically significant scores and correctly classified 60.7% of cases. Sensitivity was 59.6%, specificity was 61.4%, positive predictive values was 59.5% and negative predictive values was 81.1%. Gender was statistically significant (see Table 5.). The odds female farmworkers having a clinically significant score increases by a fac- tor of 2.3.

Table 5.

Logistic regression predicting farmworkers who will have scores of clinical concern.

|

CI

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Odds ratio | p | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper |

| Gender | −.853 | .386 | 2.34 | .027 | .426 | .200 | .907 |

| Constant | .036 | .270 | 1.03 | .893 | 1.04 | ||

Farmers

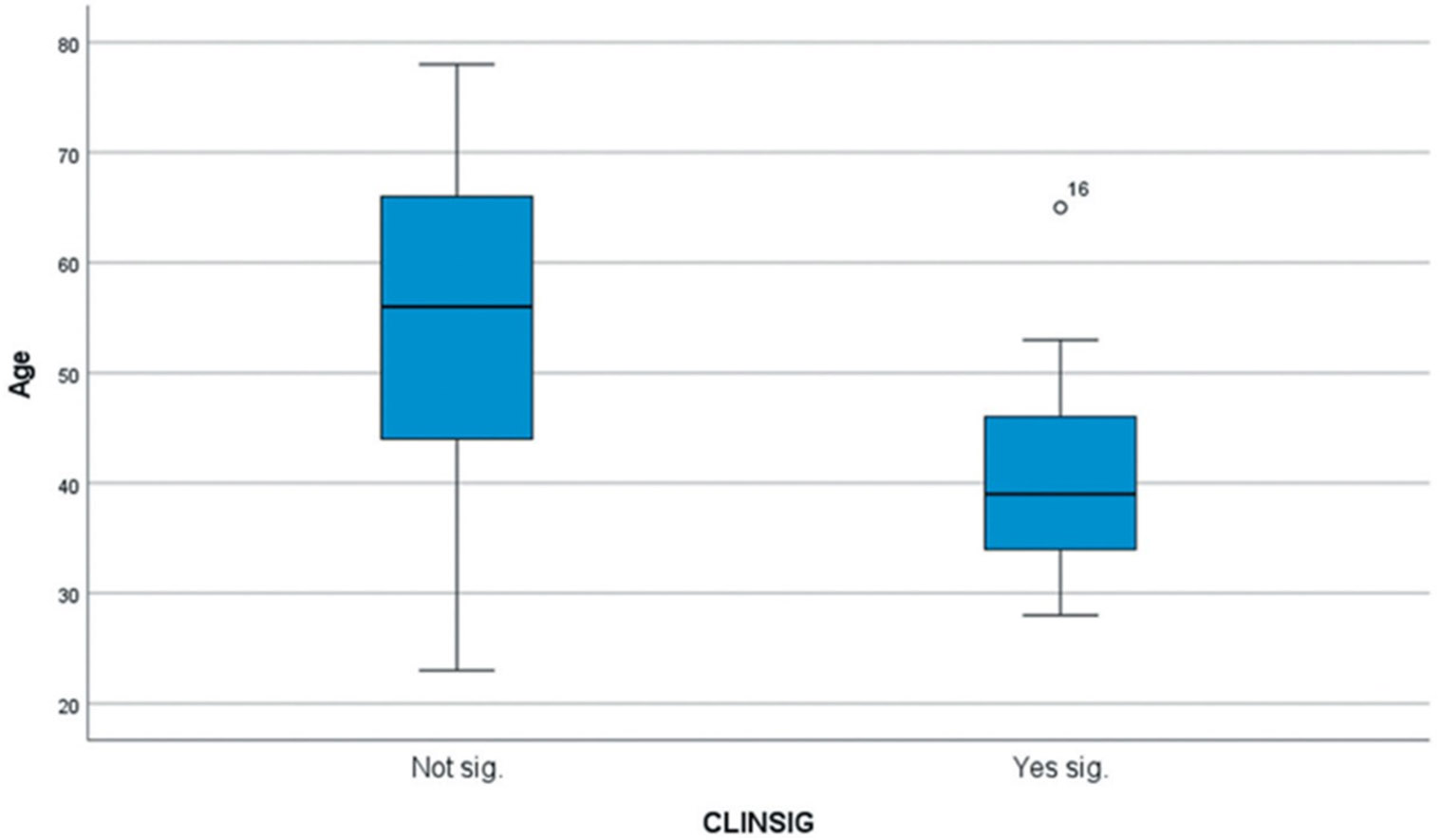

A point-biserial correlation was run between farmer age and having a score of clinical concern. Assumptions were checked and met. There was a statistically significant correlation between age and having a clinically significant score, x2 = .524, df = 1, N = 17, p = .031, with younger farmers more likely to have a clinically significant score than older farmers, M = 41.30 (SD = 3.45) vs. M = 54.13 (SD = 6.3). Age accounted for 27.4% of the variability in clinically significant scores. See Figure 1. There were no statistically significant associations (i.e., Spearman’s rho) in having a score of clinical concern and education, x2 = .249, df = 1, N = 17, p = .335 or gender, x2 = .344, df = 1, N = 17, p = .178.

Figure 1.

Box and Whisker Plot of Farmer Age and Clinically Significant Score.

Logistic regression analysis.

A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of farmer age on the likelihood of having a score of clinical concern. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, x2(1) = 5.24, p = .022. The model explained 3.5% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in clinically significant scores and correctly classified 82.4% of cases. Sensitivity was 88.9%, specificity was 75%, positive predictive values was 13.6% and negative predictive values was 14.5%. Age was approaching statistical significance (see Table 6.). The odds having a clinically significant score increases by a factor of 1.09 as farmer age decreases.

Table 6.

Logistic regression predicting farmers who will have scores of clinical concern.

|

CI

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Odds ratio | p | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper |

| Age | −.092 | .048 | 1.09 | .057 | .912 | .830 | 1.00 |

| Constant | 4.31 | 2.24 | 74.09 | .055 | 74.1 | ||

Protective coping strategies

The qualitative data highlight some of the coping strategies used by farmers and farmworkers when under stress. Reliance on natural support systems, faith, and personal pride were all found to be protective factors utilized by participants to help cope with farm-related stressors. Farmers indicated a reliance on immediate family members and pastors as a way to access mental health information. One farmer stated, “Most farmers have a very tough guy mentality and don’t want to be seen as soft or showing emotions on their sleeves.” For farmworkers, there was a reliance on family members and other farmworkers to help cope with stressors associated with farm labor. One farmworker described their colleagues in the field “as almost a family,” where another stated, “many times people come to work loaded with problems and at work they will find support, help, understanding, consideration.” Farmworkers also identified immediate family members as key players in supporting overall well-being. As one farmworker shared, “I talk with my children and my wife when I feel stressed.”

Faith for participants was also identified as a protective strategy to cope with COVID-19 related stressors beyond either groups’ control. For example, one farmer about COVID-19 impacting farm operations stated, “I have not been affected at all, thank God.” A farmworker shared similar sentiments when asked about COVID-19 impacts on their job, “I am satisfied to be a farm worker, and God gives me more life and health to continue this. I believe that we will continue for a few more years with the favor of God.”

Lastly, personal pride was found as a protective strategy to accept the physical and emotional toll of farming. One farmer expressed, “[farming] is the primary industry and creator of jobs in the area.” Two farmworkers mirrored this sense of pride, “what we do is a benefit for those who do not work in the field,” and “we all have a job to do in this world; it’s up to us to do the fieldwork.” Recognizing that the nature of farm work is physically and mentally challenging and often in unfavorable conditions, and the community’s reliance on the job, participants shared a sense of service and responsibility for completing the work that needs to happen.

Discussion

This article focuses on the mental health of farmers and farmworkers in a specific, highly productive California agricultural county. Our analysis produced the following main findings:

Many respondents had high levels of stress or depression symptomatology, with female farmworkers and young farmers most at risk for having scores of clinical concern.

Farm and family stressors related to the agricultural lifestyle were present in farmers and farmworkers to varying degrees, with both groups reporting similar protective strategies to cope with farm stress.

Our findings complement and extend the mental health research on US agricultural workers. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, farmers and farmworkers were disproportionally burdened by poor health and mental health outcomes. Our study found that approximately 42% of participants had scores of clinical concern. We found statistically significant differences between young and older farmers and male and female farmworkers. Young farmers and female farmworkers are experiencing increased vulnerabilities to mental health issues. For young farmers, our findings complement the findings of a 2020 pilot study that found a high burden of depression and anxiety among young adult farmers and ranchers.40 Personal finances, time pressures, economic conditions, and employee relations were found to contribute to the stressors experienced by young farmers and ranchers. For farmers, the main stressors within our study were navigating farm-life balance (e.g., working long hours), debt load, government regulations and policies, and farmers’ health and safety.

Female farmworkers had 2.3 higher odds of having a score of clinical concern. Our findings extend the pre-COVID-19 research demonstrating Latina low-income workers often face significant domestic responsibilities that contribute to stress levels.41 Compared to other occupations, higher levels of depression and stress were found in Latina farmworkers.42,43 Further, a recent study conducted in 2021 found that Hispanic/Latino female farmworkers in North Carolina expressed desperation, anxiety, and stress as reactions to fear and worry associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.44 Within our study, one of the highest perceived stressors in our farmworker group was being away from children and concern about health and safety, including contracting and trans- mitting the COVID-19 virus. These health and safety concerns were amplified by farmworkers expressing the lack of comprehensive health insurance, a finding reflected in studies pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic.20,44,45

The ongoing and long-term impacts of COVID-19 will likely exacerbate the mental health vulnerabilities already present in both farmers’ and farm workers’ lives. Of concern is that California adults have more unmet mental health needs than the US population46 and in 2020, 67.1% of Hispanic/ Latinos had no access to mental health and substance use treatment services.47 For Imperial County residents, this is especially concerning. Mental health remains a low priority in the region, as indicated by a shortage of mental health providers.26 Mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety have been linked to suicidality.28 Given the high death by suicide rates in both farmers and farmworker populations,48-50 we are concerned about the Imperial agriculture community experiencing severe mental health challenges. Furthermore, increased mental health concerns, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse have been reported in response to the COVID-19 pandemic,51 and COVID-19 has decreased the utilization of available mental health resources.52 For a region already considered medically underserved, rapid deployment of services to support the agriculture community is needed.

Mental health implications

This study warrants the much-needed recognition and attention farmers and farmworkers in Imperial County need regarding their mental health. When developing solutions to address the unique mental health needs of Imperial County farmers and farmworkers, it is vital to consider the following:

The distinct overall culture of the Imperial County region

The lack of healthcare access in rural communities

How agricultural populations view mental health

The historical exclusion of foreign-born workers in vital safety net programs

The stigma associated with mental health help-seeking

As such, culturally responsive mental health care48 that also understands the uniqueness of agriculture production is required for the US- Mexico border agricultural community.

A first step in addressing these mental health disparities among the vulnerable Imperial County farming community could be screening for mental and behavioral health risks using validated instruments. Trusted community members or peers could conduct digital mental health screenings for the rural farming community during interventions that promote COVID-19 or other health and safety protective behaviors (e.g., heat risk) specific to farming populations. Local organizations such as Imperial County Farm Bureau, Imperial Valley Farm Credits, Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition, and Imperial Valley Vegetable Grower Associations can provide screening resources and connect farmers and farmworkers with health care safety training, and education programs.

Our study results could be viewed as a first needs assessment to increase local farmers and farmworkers serving organizations’ awareness of mental health issues and provide directions to develop and implement mental health prevention/intervention programs. The results show that family members are considered both a stressor and protective factor. Engaging farm-family members in mental health awareness and prevention programs is critical for farmers and farmworkers in the local community. Imperial County Office of Education, school districts, and low-income community centers are the immediate organizations serving migrant families. Future research should also investigate community support and be intentionally designed to engage family members to address farm-related mental health needs.

Policy implications

COVID-19 has only aggravated the behavioral and mental health vulnerabilities experienced among farming populations, specifically Hispanic/Latino farmworkers.19 High levels of stress associated with communicating in English suggest that Spanish-language outreach and resources will be crucial to addressing farmworker mental health. Moreover, reported stress from the lack of sleep and farm-life balance suggests that mental health services will be most accessible if delivered directly to farmworkers, at their places of work or at transit and commuter points. One way of achieving this is through the expansion of certified “promotor/a” (or community health worker) programs, who can both communicate in languages familiar to farmworkers and deliver services directly through sustained in-person outreach.

While some stressors were shared between farmers and farmworkers, unique to farmers was the stress of government regulations. Farmers must comply with a wide variety of regulations, with some specific examples impacting Imperial County farmers being the Food Safety Modernization Act, the California Leafy Green Products Handler Marketing Agreement, and California Bill 1066.53,54 The California Assembly Bill 1066 was passed in 2016 and entitled agricultural workers to protections in working hours and overtime pay requirements. These labor regulations are reducing the number of hours worked per day or per week before overtime pay is required for employees, and opponents of the bill have argued that this will significantly increase labor costs for producers.55 Thus, it is important for policymakers to consider the stress of new regulations on farmers and provide assistance (e.g., training, financial incentives) to help farmers adapt their management practices to new regulations.

Limitations

Several limitations of the study must be considered. First, while we aimed to reach a diverse group of farmers and farmworkers, their responses may not be representative of the entire population of these groups. Secondly, our questions did not focus specifically on COVID-19, which likely raised stress and mental health concerns among both farmers and farmworkers. Moreover, the surveys were given at different times, with the farmer survey administered in Spring 2020 and the farmworker survey administered in Summer 2021, which may lead to different stressors being present at those different times. Third, the instruments used between the two groups were different, limiting a robust, nuanced, comparison. Also, while both instruments are designed to measure if an individual is experiencing mental health vulnerabilities (e.g., depression symptoms), they are not meant to diagnose clinical depression or provide a clinical diagnosis. Lastly, the surveys are self-reported measures and rely on respondent openness and honesty. Survey and interview results may be skewed due to social desirability, wanting to please the researcher or finish the survey quickly, or many other factors. Further, translating qualitative data from Spanish to English prior to analysis may have allowed for important language-specific communication features to be lost.

Conclusions

This study provides a baseline for understanding the stressors and mental health risks among farmers and farmworkers living and working in rural Imperial County, California. Drawing from both surveys and interviews, study results highlight that both farmers and farmworkers face high levels of stress. This is a concern for severe mental health risk and adverse outcomes and shows how important it is to improve access to mental health services in the region in a culturally responsive way. Farmers and farmworkers in Imperial County are critical to food production in the region, and their mental health must be a top priority of local organizations as well as policymakers.

Funding

This work was supported by the Western Center for Agriculture Health and Safety (WCAHS) under CDC/ NIOSH Cooperative Agreement [U54OH007550] and the High Plains Intermountain Center for Agriculture Health and Safety (HICAHS) under CDC/NIOSH Cooperative Agreement [U54OH008085]. The authors are solely responsible for this content, which does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC/NIOSH, WCAHS, or HICAHS.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Contributor Information

Annie J. Keeney, School of Social Work, San Diego State University

Amy Quandt, Department of Geography, San Diego State University.

Yu Meng, Youth Family and Community Advisor, University of California Cooperative Extension Imperial and Riverside Counties.

Luis Flores, Jr, Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition.

Daniela Flores, Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition.

Robyn Garratt, Colorado State University.

Paola Hernandez, School of Social Work, San Diego State University.

Mercy Villaseñor, School of Social Work, San Diego State University.

References

- 1.Neef A. Legal and social protection for migrant farm workers: lessons from COVID-19. Agric Human Values. 2020;37(3):641–642. doi: 10.1007/s10460-020-10086-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.California Department of Food and Agriculture. California Agricultural Production Statistics. Califonria Department of Food and Agriculutre; 2020. https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/statistics/. Accessed December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imperial County Agricultural Commission (2021, August). Economic contributions of imperial county agriculture. Crop Report Plus Series. https://agcom.imperialcounty.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-Economic-Contribution-of-Imperial-County-Ag.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grzywacz J. Mental health among farmworkers in the eastern United States. In: Arcury TA, Quandt SA, eds. Latino Farmworkers in the Eastern United States. New York: Springer; 2009:153–172. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovey JD, Seligman LD. The Mental Health of Agricultural Workers. Agricultural Medicine. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovey JD, Magana C. Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farmworkers in the Midwest United States. J Immigr Health. 2000;2 (3):119–131. doi: 10.1023/A:1009556802759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poss JE, Pierce R. Characteristics of selected migrant farmworkers in West Texas and Southern New Mexico. Calif J Health Promot. 2003;1:138–147. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothenberg D. With These Hands: The Hidden World of Migrant Farmworkers Today. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarth RD, Stallones L, Zwerling C, Burmeister LF. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and risk factors among Iowa and Colorado farmers. Am J Ind Med. 2000;37(4):382–389. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stallones L, Leff M, Garrett C, Criswell L, Gillan T. Depressive symptoms among Colorado farmers. J Agric Saf Health. 1995;1(1):37–43. doi: 10.13031/2013.19454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterworth P, Rodgers B, Windsor TD. Financial hardship, socio-economic position and depression: results from the PATH Through Life Survey. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stallones L, Vela Acosta MS, Sample P, Bigelow P, Rosales M. Perspectives on safety and health among migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the United States and Mexico: a qualitative field study. J Rural Health. 2009;25(2):219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez L. Race and the Western Frontier: Colonizing the Imperial Valley, 1900–1948. doi https://alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f36t0jmm. Santa Barbara: University of California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Census Bureau. Imperial County. The American Community Survey (ACS)-5 Year Estimate. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.USDA. Census of Agriculture Imperial County Profile. SW Washington DC: USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Personal Communication. (2019, October). Communication between Quandt and Dr. Jairo Diaz, Director of the University of California agricultural and natural resources – Desert research and extension center.

- 17.Johansson R. America’s Farmers: Resilient Throughout the COVID Pandemic. SW Washington DC: United States Department of Agriculture (USDA); 2021July. https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2020/09/24/americas-farmers-resilient-throughout-covid-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 18.UC Merced Community and Labor Center (2021, May). Fact sheet: latino and immigrant workers at highest risk of death. https://clc.ucmerced.edu

- 19.Covid-19 Farmworker Study (2020). https://covid19 farmworkerstudy.org

- 20.Kerwin D, Warren R. US foreign-born workers in the global pandemic: essential and marginalized. J Migr Hum Secur. 2020;8(3):282–300. doi: 10.1177/2331502420952752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jervis R, Plevin R, Hughes T, Ornelas O (2021). Worked to death: latino farmworkers have long been denied basic rights. COVID-19 showed how deadly racism could be. USA: Today News. https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/nation/2020/10/21/covid-how-virus-racism-devastated-latino-farmworkers-california/5978494002/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.ERA Economics LLC (2020). Economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on California agriculture. https://www.tomatonews.com/force_doc.php?file=1ac2f64c802523fa0c58c00d260fdb0292644e7e.pdf

- 23.D’Agostino JO, Benichou L Tracking coronavirus hospi- talizations in California by county. Cal Matters. https://calmatters.org/health/coronavirus/2020/04/california-coronavirus-covid-patient-hospitalization-data-icu/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaitens J, Condon M, Fernandes E, McDiarmid M. COVID-19 and essential workers: a narrative review of health outcomes and moral injury. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1446. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Census Bureau (2021). Quick facts: Imperial County, California. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/imperialcountycalifornia

- 26.County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. Madison, WI: UW Population Health Institute; 2020. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imperial County Public Health. (2016). Imperial county health status report 2015-2016. http://www.icphd.org/media/managed/medicalproviderresources/HEALTH_STATUS_2015_2016_final.pdf

- 28.CHCF. Mental health in California: for too many, care not there. In: California Health Care Almanac. Oakland: California Health Care Foundation; 2018:19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin RY. Validly and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation. 2013;19(3):321–332. doi: 10.1177/1356389013497081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hovey JD. (2000). The migrant farmworker stress sur- vey. https://www.jhoveyphd.com/uploads/1/2/7/2/127269752/mfwsi_english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramos A, Carlo G, Grant K, Trinidad K, Correa A. Stress, depression, and occupational injury among migrant farmworkers in Nebraska. Safety. 2016;2(4):23. doi: 10.3390/safety2040023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiott AE, Grzywacz JG, Davis SW, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Migrant farmworker stress: mental health implica- tions. J Rural Health. 2008;21:32-doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: evaluation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(5):437–443. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keeney AJ, Hernandez P, Meng Y. Assessing farm stress and community supports in a US-Mexico border county. J Agric Saf Health. 2021;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.13031/jash.14213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CDC. Organization of Work: Measurement of Tools and for Research and Practice. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/workorg/detail092.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guest G, Namey E, Chen M, Soundy A. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4th. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudolphi JM, Berg RL, Parsaik A. Depression, anxiety, and stress among young farmers and ranchers: a pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(1):126–134. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodríguez G, Trejo G, Schiemann E, et al. Latina workers in North Carolina: work organization, domestic respon- sibilities, health, and family life. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;18(3):687–696. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pulgar CA, Trejo G, Suerken C, Ip EH, Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Economic hardship and depression among women in Latino farmworker families. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;18(3):497–504. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arcury TA, Sandberg JC, Talton JW, Laurienti PJ, Daniel SS, Quandt SA. Mental health among Latina farmworkers and other employed Latinas in North Carolina. J Rural Mental Health. 2018;42(2):89–101. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quandt SA, LaMonto NJ, Mora DC, Talton JW, Laurienti PJ, Arcury TA. COVID-19 pandemic among immigrant Latinx farmworker and non-farm- worker families: a rural–urban comparison of eco- nomic, educational, healthcare, and immigration concerns. New Solutions. 2021;31(1):30–47. doi: 10.1177/1048291121992468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bail KM, Foster J, Dalmida SG, et al. The impact of invisibility on the health of migrant farmworkers in the southeastern United States: a case study from Georgia. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/760418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF]. (2022). Mental health in California. https://www.kff.org/statedata/mental-health-and-substance-use-state-fact-sheets/california

- 47.SAMSHA. (2020). Behavioral health barometer: united States. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt32815/National-BH-Barometer_Volume6.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenaway C, Hargreaves S, Barkati S, et al. COVID- 19: exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. J Travel Med. 2020;27 (7). doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor (2020). Fatal occupational injuries to for- eign-born workers. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2018/fatal-occupational-injuries-to-foreign-born-workers.htm

- 50.NIOSH (2021). NIOSH strategic plan: fYs 2019-2024. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/about/strategicplan/workaff.html [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aragona M, Barbato A, Cavani A, Costanzo G, Mirisola C. Negative impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health service access and follow-up adher- ence for immigrants and individuals in socio-economic difficulties. Public Health. 2020;186:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoar BR, Atwill ER, Carlton L, Celis J, Carabez J, Nguyen T. Buffers between grazing sheep and leafy crops augment food safety. Calif Agric. 2013;67 (2):104–109. doi: 10.3733/ca.v067n02p104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calvin L, Jensen H, Klonsky K, Cook R. Food safety practices and costs under the California leafy greens marketing agreement. Econ Inform Bull. No. (EIB-173). 2017. 64. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/83771/eib-173.pdf?v=0 [Google Scholar]

- 55.California Ag Today. The impact of regulations for farmers. https://californiaagtoday.com/impact-regulations-farmers/