Abstract

This study examines the influence of temperature and noise on autistic individuals. Conventional indoor comfort questionnaires as well as pre-validated attentional tests were administered to autistic and typically developed individuals across six different environmental scenarios. Results showed that autistic individuals struggled with completing conventional questionnaires independently providing inconsistent responses. Attentional tests were always successfully autonomously completed, revealing significant performance declines for autistic individuals because of temperature variation (4 °C) or sudden noises. Background noise (55 dB(A)) also caused performance decreases, whether typically developed individuals were unaffected by all conditions. These findings suggest that (i) conventional indoor comfort questionnaires are unsuitable for autistic individuals, (ii) indoor environmental conditions (temperature and noise) do stress autistic people (iv) stressors thresholds are provided and (iv) attentional tests could be successfully used to investigate autistic individuals’ indoor conditions and assess their perceived stress in relation to variations of temperature and acoustic circumstances.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-02358-4.

Subject terms: Energy science and technology, Civil engineering

Introduction

The primary objective of this research is to investigate how indoor environmental factors, such as temperature and noise levels, may act as stressors for autistic individuals. In the existing literature, these parameters are conventionally analysed within the framework of indoor comfort, primarily considering them as contributors to well-being rather than potential sources of stress.

Indoor comfort pertains to the various parameters that contribute to an occupant’s overall sense of well-being within a built environment1. When thinking globally about indoor comfort, one should assess four environmental domains: thermo-hygrometric, acoustic, visual, and indoor air quality. However, only the first domain has been thoroughly studied in literature, producing a standard methodology of investigation. Thermal comfort, as delineated by the ASHRAE2, is achieved when occupants express subjective satisfaction with the thermal domain. According to the standard definition (Fanger’s model3), an individual perceives a state of thermal neutrality when feeling neither warm nor cold. The assumption is that the response provided by a sample of individuals can be generalized for any group of subjects.

The aforementioned fields of investigation were mainly defined and studied over the years for standard occupants4, usually by means of measurements and questionnaires. Surveys are generally constructed in accordance with ISO standards5–8 and have been envisioned and extensively adopted for standard occupants, specifically typically developed (TD) individuals. The approach relies on acquiring a direct and conscious evaluation by respondents.

When surveys are not possible, thermal indoor comfort is calculated by the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) index, which provides the average subjective response of the thermal sensation of a large cohort3. However, the possibility of assessing comfort conditions for non-TD individuals (e.g. autistics) is of increasing importance in designing or evaluating the performance of more inclusive environments9–11, as underscored by policymakers12,13. Awareness of this priority is supported by the increasing rate of annually diagnosed cases of mental disorders14. Consequently, both existing and newly constructed buildings are called to prioritize inclusivity in their indoor environments15,16, ensuring robust accessibility and adherence to established standards17,18.

In particular, autistic individuals may have a broad range of special needs when it comes to indoor comfort that need further investigation to ensure inclusivity and well-being19. Due to their unique conditions, autistic individuals may perceive their surroundings differently from TD occupants, particularly since the can perceived specific sensory stimuli less (hyposensitivity)20 or more (hypersensitivity)21 in comparison with TD occupants. This condition that cooccur with autism diagnosis is known as sensory processing disorder.

Given that autistics individuals often encompasses various complex comorbidities22, understanding how temperature and noise affect autistic users represents a multifaceted challenge. Moreover, the use of conventional approaches, such as questionnaires, require direct, aware and reliable feedback from users. Additionally, the structure of standard questionnaires is typically designed for TD individuals, which may pose challenges for autistic users. Autistic individuals might struggle with open-ended questions due to difficulties in articulating their thoughts, while multiple-choice questions might be overwhelming due to an excessive focus on specific details or a lack of clarity in interpreting options23–25.

In literature some studies have considered the comfort part, namely the thermal comfort, showing that the PMV index reflects an average perception of comfort among neurotypical individuals19. Anyway, limited research exists on the thermal (or acoustic) comfort perception of autistic individuals26,27. Some studies have investigated indoor comfort in autistic users by focusing on specific domains, such as acoustics28–30 or thermal conditions31,32. Even if these studies have made important contributions, they lack consistency in the templates of adopted questionnaires, rendering comparisons between studies and across domains difficult. Other research efforts have focused on identifying specific stimuli that most significantly affect autistic occupants33–36. For example, research into acoustic conditions has highlighted heightened sensitivity to specific noise sources, including sudden noises, background noises, or animal voices37. Similarly, studies on thermal comfort have shed light on their thermal preferences38. However, the sets of questions and evaluation scales differ significantly across these studies, resulting in fragmented investigations or narrowly focused research topics dictated by specific research conditions39. This makes it challenging to assess the combined effect of multi-domain stressors and hinders a comprehensive understanding of the issue. Consequently, the applicability of findings is frequently limited to the specific context under study40.

Given the frequent difficulty of obtaining responses directly from autistic individuals, other studies have relied on proxies. Some authors41–43 have attempted to understand the indoor comfort of autistic users through proxy respondents. However, this approach introduces potential biases due to the indirect personal interpretation of the reasons for and degree of discomfort44. For instance, caregivers or parents’ subjective observations may lead to inaccurate representations of autistic individuals’ comfort perceptions. While proxies can offer useful insights, they cannot fully replicate the lived experiences of the individuals they represent45. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop research approaches that enable direct engagement with autistic individuals, ensuring their voices are heard and their needs authentically represented when designing inclusive indoor environments46. This issue underscores the inherent challenge of obtaining direct and unfiltered feedback from autistic populations.

The authors have recently conducted a comprehensive review of studies focusing on autism as well as the broader spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders47, with the findings serving as a foundation for the analysis proposed in this paper. A novel approach is needed to enable the interpretation of environmental feedback directly from autistic individuals based on validated and uniform procedures that are replicable and accessible to researchers across disciplines. Furthermore, given that the existing literature heavily emphasizes only two of the four comfort parameters (acoustic and thermal, specifically noise and temperature), the present research will focus exclusively on these two stressors. This approach allows for a more informed and robust analysis, drawing on the existing body of knowledge while ensuring adherence to ethical and privacy guidelines.

In this context, this paper underscores the significance of employing standardized tools for multidisciplinary approaches when studying the indoor comfort of autistic individuals, emphasizing their pivotal role in indoor comfort evaluations.

Within this framework, this work will focus on responding to the following questions:

Can environmental conditions (temperature and noise levels) influence the attentional performance of autistic individuals?

Can direct questions included in comfort questionnaires be answered by autistic individuals?

Do the results of administered questionnaires align with the expected results?

The terminology adopted in this paper aligns with current best practices in the relevant literature on autism research, drawing on recommendations from Botha and Cage48, Monk, Whitehouse, and Waddington49 and Bottema-Beutel et al.50, which emphasize respectful, non-ableist language and the importance of acknowledging autistic voices in academic discourse.

Materials and methods

To answer to these questions, the authors designed a set of experiments to explore the influence of temperature and noise on autistic individuals. Besides, the applicability of commonly used indoor comfort questionnaires for autistic individuals is investigated. These assessments were conducted across six distinct environmental scenarios, each characterized by varying temperature and noise levels.

For these purposes, a passive monitoring of environments was utilized within a controlled environment. The study involved two distinct groups of participants: 25 autistic individuals (AUT group) and 25 standard occupants (TD group). As this study aimed to explore the general applicability of the proposed methodology rather than to assess the specific impact of individual variables, detailed measures such as intelligence scores, symptom severity (e.g., ADOS), or comorbidities in the analysis were not taken into account. The aim of the proposed approach is to determine whether the method could be feasible and meaningfully applied to a heterogeneous group of autistic individuals. The experimental design sought to capture real-world data by monitoring these participants in their daily settings.

Six different environmental scenarios were designed to be reproduced in a controlled environment of a specialized care organization (ProgettoAutismo Foundation Udine, Italy, Section “Investigated scenarios”). Environmental conditions were passively monitored throughout these six scenarios. (Section “Environmental monitoring”) when administering both indoor comfort questionnaires (Section “Administration of comfort questionnaire”) and attentional tests. The potential of attentional tests, including their various applications within the ASD population, is explored and reported in Appendix A—Supplementary Material. To ensure rigor in the psychological and psycho-pedagogical fields, the research was conducted under the strict supervision of psychologists, psychiatrists, pedagogues and caregivers, provided by the care facility. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, details are available in Section “Sample description and ethical procedures”.

Investigated scenarios

To identify relevant environmental conditions applicable to the care facility, a literature review47 was performed and summarized in Table 1 with a focus on the autism results.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on the indoor comfort of autistic people (alphabetic order).

| Study | Method | Comfort domain | Diagnosis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouzidi et al.38 | PMV + questionnaire | Thermal environment | ID + ASD + others | Neutral temperature at 24 °C |

| Caniato et al.35,36 | Questionnaire | 4 comfort domains | ASD |

Influence of comorbidity and age on the perception of the comfort domains Identification of specific sounds, visual and thermal phenomena that are identified as critical by proxy respondents |

| Doherty et al.33 | Review | 4 comfort domains | ID + ASD | Presence of noises, odors and bright lights could be challenging |

| Kanakri et al.30 | Questionnaire | Acoustic environment | ASD | Qualitative guidelines for optimizing soundscapes |

| Noble et al.34 | Questionnaire | 4 comfort domains | ASD | Identification of specific stimuli that trigger ASD users |

| Vilcekova et al.32 | PMV-PMD model; SPL analysis, PPM concentration analysis; Illuminance level analysis + Questionnaire | 4 comfort domains | ADHD | A greater Metabolic Rate should be considered for ADHD users |

The following acronyms are explained here: ADHD, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autistic spectrum; ID, intellectual disability.

Regarding studies on acoustics, some works have addressed the topic and their findings are summarized in Table 1. However, none specify the sound pressure levels or thresholds beyond which these noises may become stressful. Consequently, the studies by Doherty et al.33 and Kanakri et al. were used to select the background noises, while those by Caniato et al.35,36 and Noble et al.34 informed the choice of sudden noises.

In the absence of specific quantitative data on sound levels tailored to autistic users, a study on neurotypical students was referenced to identify baseline sound levels as a starting point for setting up the environments to be investigated. Particularly, Huang et al.51 conducted on college students, it was found that satisfaction with the environment increased when noise levels are below 50 dB(A); higher levels of anthropic background noises led to discomfort52. Therefore, 50 dB(A) serves as a suitable reference point for understanding the impact of Sound Pressure Levels on attention. While according to the studies in literature30,33,51 an indistinguishable chattering noise was used for background noises, details about the sudden noises played for the study are listed in Appendix D—Supplementary Material.

Moreover, based on preliminary analyses of the controlled environment, the internal thermostat for the therapy room was adjusted to the neural temperature specified in the study by Bouzidi et al.38. Consequently, in this work, the thermal variation (i.e. the scenario where the temperature is considered as a stressor) aligned with typical summer temperatures31, specifically 28.5 °C.

The indoor air quality was assured by a ventilating system, guaranteeing that CO2 would always be less than around 1000 ppm threshold. The illuminance levels were monitored to ensure the room remained around 300 lx, in accordance with various relevant recommendations53,54.

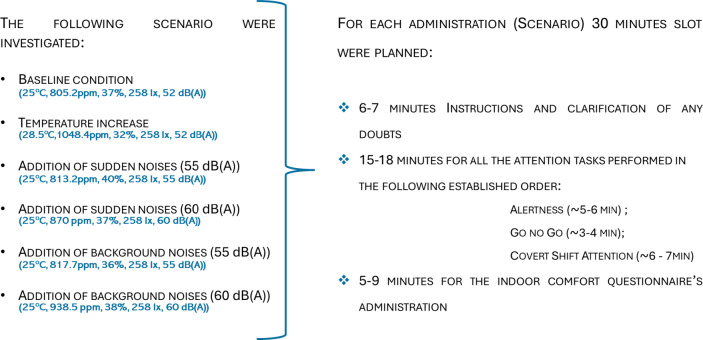

Therefore, after merging all the results, the implemented scenarios are described below:

Baseline Scenario: settled environmental condition by the hosting care facility (25 °C, 805.2 ppm, 37%, 258 lx, 52 dB(A))

Temperature increase: baseline scenario plus temperature change (summer temperature) (28.5 °C, 998.4 ppm, 32%, 258 lx, 52 dB(A))

Sudden noises 55 dB(A): baseline scenario plus the addition of sudden noises (such as human sneezes or laugh, slamming doors, animal voces etc.) at a level of 55 dB(A) (25 °C, 813.2 ppm, 40%, 258 lx, 55 dB(A))

Sudden noises 60 dB(A): baseline scenario plus the addition of sudden noises (such as human sneezes or laugh, slamming doors, animal voces etc.) at a level of 58 dB(A) (25 °C, 870 ppm, 37%, 258 lx, 60 dB(A))

Background noises 55 dB(A): environmental conditions of the baseline scenario with the only change being the addition of anthropic background noises at 55 dB(A) (25 °C, 817.7 ppm, 36%, 258 lx, 55 dB(A))

Background noises 60 dB(A): environmental conditions of the baseline scenario with the only change being the addition of anthropic background noises at 60 dB(A) (25 °C, 938.5 ppm, 38%, 258 lx, 60 dB(A))

Environmental monitoring

A comprehensive passive environmental monitoring system was implemented using sensors placed within the environment provided by the care facility. This system continuously tracked a range of environmental parameters, including illuminance (lx), temperature (°C), humidity (%), CO2 concentrations and sound pressure levels (dB(A)). The accuracy of the sensors used for the environmental monitoring is detailed in Table 9—Appendix D—Supplementary Material. These measurements were conducted to ensure that the environmental conditions were accurately captured and maintained constant throughout the study. Additionally, to assess thermal comfort, the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) is calculated following the guidelines set forth in ASHRAE Standard 552. The position of the sensors is displayed in Fig. 3 – right, while the sensors’ characteristics are detailed in Appendix D—Supplementary Material.

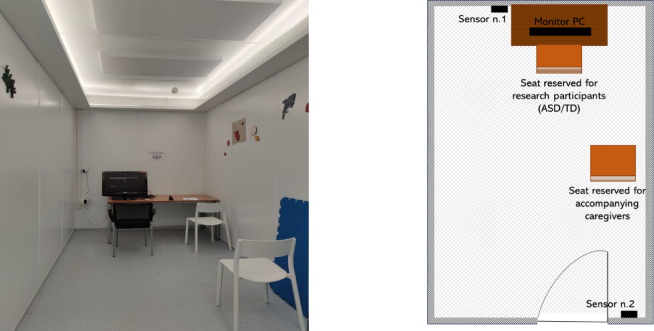

Fig. 3.

Therapy room dedicated to the research (left); set-up of the sensors and of the room (right).

Administration of comfort questionnaire.

Literature sometimes used different comfort questionnaire55,56. In this paper the authors adopted the one proposed by the ASHRAE 552 used many times in literature57,58, extended to all comfort domains59.

The questionnaire comprised two sections:

Section 1 : an information sheet designed to gather participants’ anonymous details, including gender, clothing, comorbidities and health status.

Section 2: a set of questions focusing on the thermal and acoustic domains, featuring questions such as "How do you feel right now?" with response options ranging from highly uncomfortable (very cold or very hot) to comfortable on a 7-grade scale.

Instructions for completing the questionnaire and training workshops were previously provided to both groups of participants (TD and ND). Whenever feasible, autistic participants were encouraged to independently complete Section 2. When autistic individuals were unable to answer independently, accompanying caregivers (CGs) were requested to assist them in completing the questionnaire. Dedicated training on how to support the AUT group in the compilation was then given to the CGs to ensure complete administration of the questionnaire (Appendix B – Supplementary Material and Section "Sample description and ethical procedures").

The role of attention

Attention tests are more suitable for receiving direct feedback from an individual. They are not based on questions (which would require understanding what the question is asking and thus involve communication skills), but rather on attentional tasks, such as pressing a button when something appears on the screen, etc.

Attention is a preferred cognitive measure for environmental studies due to its inclusivity and multidimensional relevance. Unlike language-based or abstract reasoning tests, which may disadvantage autistic individuals with communication challenges, attention tests can be adapted to non-verbal and universally understandable formats, ensuring broad applicability60. Moreover, attention tasks, such as reaction time or Stroop tests, indirectly assess related domains like processing speed and working memory, offering a comprehensive view of cognitive performance61,62. These tasks reflect also real-world demands like maintaining focus in distracting environments, making them ideal for assessing environmental impacts on cognition63.

Attentional test selection and administration

From the literature review (Sections "Introduction" and "Investigated scenarios"), we can conclude that four primary methods were predominantly employed by various authors: questionnaires, attentional tests, interviews64,65 and (only for temperature investigation) pain thermal thresholds66,67. This last approach however would constrain the analysis to a single domain. The first three methods do need a robust and reliable response given by individuals. Then, given the challenges of administering questionnaires to autistic individuals43, an effort was made to adopt an alternative, pre-validated and widely-used approach68–70.

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify among attentional tests, the ones that ensure the possibility of obtaining direct feedback from the users. Initially, it was necessary to identify studies that had integrated the use of attentional tests for both TD and AUT users in indoor comfort research, since the present paper involve both groups. Subsequently, an analysis of attentional assessment tools was conducted. The following provides an overview of the analysis undertaken.

The role of attention in indoor environmental studies

Attentional testing initially emerged as a diagnostic tool to detect early indicators of developmental disorders in childhood or cognitive impairments in adulthood71,72. Consequently, attentional tests have become extensively utilized across medical, psychological and neuropsychological domains for monitoring, preventive measures and diagnostic assistance73,74.

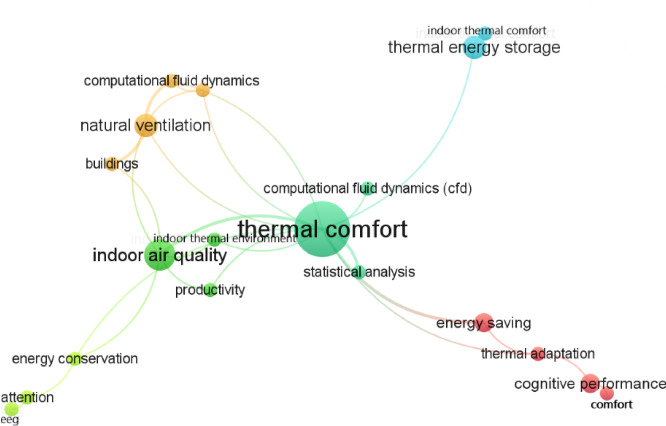

To better understand the relative diffusion of attention tests in studying indoor comfort, a literature search was conducted, accompanied by a visual map of the most frequently cited results. Figure 1 shows the results of the most common keywords used when searching for “indoor comfort AND attention test” on Scopus. The keyword analysis highlights that most researchers focus on a single comfort domain, primarily for assessing productivity rather than well-being, with a predominant emphasis on thermal comfort.

Fig. 1.

Keywords occurrence when searching for “indoor comfort AND attention test”.

Attentional testing has been increasingly used to assess indoor environmental conditions and their impact on cognitive performance75–77. Studies highlight that factor like temperature, air quality, and lighting influence attention78–80, with extreme temperatures reducing performance by up to 24%81. These tests has been mostly restricted to thermal comfort studies82–90 and only a few on noise effects91,9293,94. Moreover, they often focus on specific cognitive aspects95,96 rather than providing a comprehensive assessment.

While attentional tests have been adopted to evaluate performance changes in TD users under varying environmental conditions, their primary function remains as a diagnostic tool. Indeed, these tests have been primarily utilized by experts for diagnosing neuro-disorders97–99.

Nevertheless, a few studies measured performance in relation to indoor parameters through tests specifically designed to assess attention. Among the studies68,75,100–107, only few of them, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, focused on using this approach to assess autistic users’ stress caused by noise and temperature.

Keith et al. investigated the impact of noise on cognitive performance in autistic adolescents compared to TD peers matched for age, gender and IQ108. Using a number span task109, they examined how background noise influenced memory recall under different difficulty levels. Their findings indicate that acoustic stimulation may affect cognitive performance during manageable tasks. However, the study’s requirement for an IQ above 80 limits its applicability, potentially excluding a significant portion of the autistic population110. Thus, the results may not accurately reflect the majority of the autistic population.

Analysis of the attentive tests and tasks

Multiple attention tests are available, prompting a review of the leading ones adopted in psycho-pedagogy. A full analysis on the selection process of attention tests is available in Appendix A – Supplementary Material.

Based on the comparison of the Table 5—Appendix A (Supplementary Material), information and needs such as (i) standardization, (ii) use of the test on ASD subjects, (iii) need to repeat the test several times and (iv) inclusion of users of all ages during the research, together with psychologists from the hosting care facility, TAP (Test of Attentional Performance) was identified as the most suitable attentional test for research. The choice was supported by the numerous attentional tasks available that could include users regardless of IQ.

In addition, of the numerous attentional tasks included in TAP, only three were selected by the psychologists and pedagogues of the care facility staff to be suitable for all users. Furthermore, the three selected attentional tasks offer a concise yet comprehensive overview of fundamental attentional performance.

The selected attention tasks were: (i) alertness, (ii) go no go and (iii) covert shift of attention. The attention component measured by the selected tasks, their cognitive function and purpose are described in the Table 2. Since each attentional tasks has different parameters that need to be evaluated and discussed according to the Norms Tables111, the last row of Table 2 shows the parameters come into play for each task. Each relevant parameter is then compared, when showing the results, to the acceptable value recommended in the TAP Norms Tables111.

Table 2.

TAP tasks selected for the research purpose.

| Attentional component | Tasks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alertness or arousal | Go/no-Go | Covert shift attention | ||

| Tonic alertness (alertness round 1° and 4°) | Phasic alertness (alertness round 2° and 3°) | Focused selective attention | Visuo-spatial selective attention | |

| Assignment | The assignment requests the user to click after seeing a visual stimulus (X) on the screen | The assignment requires the user to click after seeing a visual stimulus (X) on the screen. To prepare for a quicker response to the task’s target visual stimulus, a sound stimulus is presented here before the visual stimulus | The assignment requires to discern the correct signal (X) from the incorrect one (+) in the center of the screen. Visual stimuli come one at a time, randomly. The aim is to avoid clicking when you receive the “wrong” signal (+) | The assignment entails determining the visual stimulus (X). An arrow pointing left or right indicates the side on which the target stimulus (X) is most likely to emerge. This cue stimulus comes before the target stimulus (X). Twenty percent of the time, the arrow will point in a direction but the (X) will never emerge. In eighty percent of the cases, the arrow will point in the direction in which the X will appear. Regardless of the arrow’s orientation, the objective is to identify and click at the visual stimulus sight (X) without feeling lost |

| Relevant parameter according to the TAP’s Norms Tables111 | Median rection time [ms] | Median rection time [ms] + N° of errors | Median rection time [ms] of valid stimuli + median rection time [ms] of invalid stimuli | |

Each attentional task was, then, repeated for each scenario for all the 50 users (25 AUT and 25 TD). All participants managed to complete all tasks for the entire six weeks, with a total of 18 attentional tasks completed for each participant.

According to key contemporary psychology textbooks112–115, the three attentional components examined in this study are defined as follows:

-Alertness (Arousal): This task measures the general state of activation and readiness within the nervous system. It is a core concept in neuroscience, critical to a person’s ability to swiftly and effectively respond to the surrounding environmental stimuli.

The Go/No-Go Task: This neuropsychological task is employed to measure selective focused attention, specifically targeting inhibitory control and decision-making speed. It is widely used in both research and clinical settings to assess executive functioning, particularly the brain’s capacity to suppress inappropriate or automatic responses (response inhibition).

Covert Shift of Attention: This task pertains to visuo-spatial selective attention, referring to the mental redirection of focus from one location to another without accompanying eye or body movements. Essentially, it reflects the brain’s ability to selectively process relevant information without requiring a physical shift in gaze, enabling efficient cognitive processing of stimuli not directly observed.

Furthermore, since the attentional test must be administered exclusively by accredited psychologists, measures were taken to protect participant privacy and avoid disclosing their identities. To ensure that no non-specialized psychological personnel (research staff) were present, which could potentially distract participants—particularly those in the autistic group—only psychologists and psycho-pedagogists from the facility were permitted to enter the therapy room. They were accompanied by the participants’ usual caregivers when necessary, ensuring a familiar and supportive environment during the testing process.

Controlled environment—care facility

The care facility serves autistic individuals, offering a range of activities throughout the day. Autistic users could participate in daytime activities (8 am–5 pm), afternoon activities (2–5 pm), or tailored schedule for specific needs or preferences, such as bi-weekly daytime or afternoon sessions. The activities are designed to promote the autonomy of autistic individuals and include psychotherapy, education support, speech therapy, artistic endeavours in studios, cooking workshops and more.

In the current research, to maximize user participation and preserve the integrity of established activities and goals with users and their families, a weekly time slot of 30 min for each user was designated as the optimal duration of each test. The facility allocated a therapy room (Fig. 3) to which users are already familiar with, to accommodate the installation of sensors for passive environmental monitoring. The passive monitoring continued for the entire duration of the administration. CO2 levels, temperature, humidity and illumination were recorded every 5 min, while sound pressure levels were measured every second.

A full week of monitoring (7 days) per scenario was required, with efforts made to schedule the age-matched AUT and TD pairs in consecutive time slots. The interval between the investigation of each scenario was 10 days, allowing for the monitoring of approximately two scenarios per month. Every individual participated to every scenario, which was maintained constant for the whole 7 days slot.

The administration was repeated in the predetermined order: Baseline, Temperature, Sudden Noises 55 dB(A), Sudden Noises 60 dB(A), Background Noises 55 dB(A) and Background Noises 60 dB(A). Participants entered the room and were given a 15-min adaptation period. Under the same environmental conditions, they then listened to the instructions and completed the attentional test and questionnaire within the following 30 min. These timeframes were determined by psychologists, psychiatrists and educators as the maximum duration, appropriate to avoid stress to the autistic group. It should be considered that all participants lived and/or worked and/or pass their days in the entire facility, under conditions nearly identical to the baseline scenario. Therefore, the 15-min adaptation time was intended solely for familiarization with the room, rather than for acclimatization to environmental conditions such as temperature and noise. A summary of the administration procedure is provided in Fig. 2 and the complete questionnaire can be found in Appendix B (Supplementary Material).

Fig. 2.

Summary outline of the procedure and the six scenarios investigated.

With the aim to find an approach that includes (i) repeatability59, (ii) avoidance of the interpretation bias116 and (iii) inclusivity of a wide range of autistic users117, both the process of gathering user needs and the collaboration with the facility’s staff were pivotal to foster a full partnership with the users. Moreover, the decision to conduct the investigation within the host facility, rather than in a laboratory environment, was made in consultation with the psycho-educational staff to mitigate the perturbation of unexpected displacement118. Additionally, placement in environments like laboratories might have influenced the users’ perception of the environment and the influence of being in a completely unfamiliar setting could have impacted their comfort119 (Fig. 3).

Sample description and ethical procedures

Through internal recruitment at the care facility and through an anonymous workshop detailing the study’s objectives, a group of participants was engaged. A total of 25 autistic individuals, referred to as the AUT group, participated either through autonomous consent or with parental or guardian support for minors or those non-autonomous.

Additionally, a volunteer TD group consisting of 25 typically developed individuals was involved as a control sample.

The TD group, representing the standard occupants, was recruited from volunteers affiliated with ProgettoAutismo. The AUT group, on the other hand, was selected by psychologists, psychiatrists and educators among the autistic users of the facility. A homogeneous group of people on the spectrum was involved with similar level of autonomy (level 2 according to the DSM-V), number of comorbidities and average age of the sample. Nevertheless, it must be considered that persons with more or less similar autonomy could still be substantially different according to comorbidities and the broad autism spectrum characteristics and unique needs120,121.

Participants were selected to closely match the age and the gender profile of the autistic group. Detailed information regarding the samples can be found in Table 3. Analysis of the data reveals that efforts were made to construct the sample groups with similarity in terms of age and gender. Furthermore, examination of the averaged clothing index data (CLO) across different scenarios indicates that the ASD group consistently wore lighter clothing compared to the TD group. This observation may be attributed to the TD group comprising individuals who work at or perform community service at the facility and thus wore formal dressing. The results also demonstrate the heterogeneity of the autistic sample. Despite all participants sharing an autism diagnosis, they presented a total of 17 different comorbidities, illustrating the broad spectrum of diagnosis. The minimum number of comorbidities identified in a single ASD participant was 3, while the maximum was 6. The declared comorbidities were 56% Intellectual Disability (ID), 32% Global Developmental Delay (GDD), 24% of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), 20% with the former Asperger diagnosis (EX—ASP), 44% Other comorbidity (12% Obsessive–Compulsive-Disorder, 8% Anxiety Disorders, 8% Language Disorders, 4% Depressive Disorders,4% Dyscalculia, 4% Childhood Psychosis, 4% Oppositional Defiant and Explosive Intermittent Behavioural Disorder).

Table 3.

Demographic metrics.

| TD | AUT | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M = 75%; F = 25% | M = 63%; F = 38% | |

| Average age | 21 ( =21) =21) |

19 ( =27) =27) |

|

| N. of different comorbidities declared | – | 17 | |

| Averaged CLO | Baseline | 0,43 | 0,32; |

| Temperature | 0,40 | 0,31 | |

| Sudden noises 55 dB(A) | 0,43 | 0,40 | |

| Sudden noises 60 dB(A) | 0,43 | 0,35 | |

| Background noises 55 dB(A) | 0,47 | 0,39 | |

| Background noises 60 dB(A) | 0,46 | 0,47 | |

The test and questionnaire monitoring and administration campaign lasted a total of 6 months during the summer season. The test was easy and feasible compilation by all participants.

This study was approved by the Privacy Office of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano. All participants were fully informed about the study and provided written informed consent before participation. In the case of minors or individuals unable to provide consent autonomously, informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians. The study was conducted in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time and could request the deletion of their research-related data without any justification.

In pursuit of privacy and inclusivity:

A workshop was organized for all staff, caregivers, psychologists and educators at the facility. The objective was to elucidate the methodology of administering attentional tests and the accompanying monitoring procedures.

Activities were exclusively carried out with the regular accompanying staff, eliminating the presence of unfamiliar university personnel to safeguard participant privacy.

Participant data, encompassing both general information and attentional test results, were gathered anonymously to ensure confidentiality.

Informational materials and consent forms for anonymous data processing were disseminated among all autonomous participants and the parents of non-autonomous participants.

All participants could interrupt at any time the test and withdrawn from the procedure, asking to delete data belonging to their personal activities.

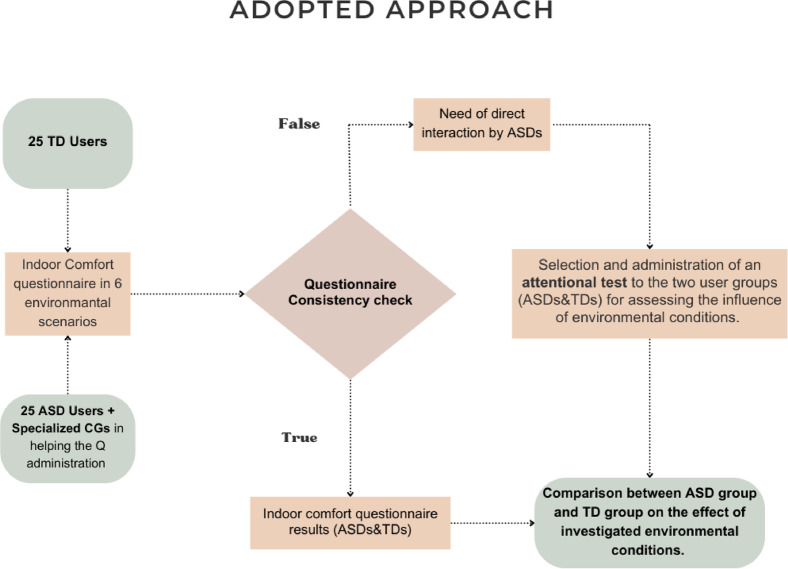

To address the research questions and elucidate the adopted approach, an explanatory flowchart is presented in Fig. 4. Below is a summary of the methodology utilized in the study.

Fig. 4.

Adopted approach.

Results

In this section, the results of the questionnaire and the attention test will be presented, along with the monitoring process. All 50 participants completed both the attentional test and the questionnaire for each of the six scenarios, resulting in a total of 6 attentional tests and 6 questionnaires per participant. This process yielded approximately 42 h of continuous monitoring data for each scenario.

This section will outline the principal findings by the questionnaire administration and the selection of attentional tests for the purposes of the research under consideration. Subsequently, the outcomes of the attentional tests will be delineated.

Indoor comfort questionnaire results

The results in Table 4 show how ASD and TD users responded to the general comfort questions of the Section “Materials and methods”. The result is a percentage proportionate to the size of the two samples.

Table 4.

Summary of rates of inconsistency and non-autonomy of questionnaires.

| Scenario | User group | non-autonomous compilation [%] | % inconsistency in the questionnaire responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | AUT | 16% | 16 |

| TD | – | 0 | |

| Temperature | AUT | 32% | 8 |

| TD | – | 0 | |

| Sudden noises 55 dB(A) | AUT | 27% | 16 |

| TD | – | 0 | |

| Sudden noises 60 dB(A) | AUT | 20% | 12 |

| TD | – | 0 | |

| Background noises 55 dB(A) | AUT | 32% | 25 |

| TD | – | 8 | |

| Background noises 60 dB(A) | AUT | 40% | 8 |

| TD | – | 0 |

Table 4 illustrates the decline in self-completion of questionnaires by the autistic group as the environmental scenarios varied. Initially, under baseline conditions, only 16% of the autistic group, as professionally assessed by the caregivers, required assistance in completing the questionnaires. However, this percentage increased significantly to 40% in the background noise scenario at 60 dB(A).

It is noteworthy that the questionnaires were completed inconsistently by users in the autistic group, particularly in certain environmental scenarios. Inconsistencies were calculated by analysing responses for each individual domain, comparing sensitivity responses with preference responses. If preference or sensitivity responses deviated significantly (≥ ± 2) from each other, the response was classified as inconsistent. Notable examples include a preference for an even noisier environment (-2 on preference scale) despite feeling the same environment as noisy (-2 on sensitivity scale) or perceiving an environment as too hot (+ 2 on sensitivity scale) and expressing a preference an even warmer one (+ 2 on sensation scale). Such responses are characteristic of autistic populations, who often face challenges in providing consistent answers to both open-ended and multiple-choice questions. These challenges arise due to the nature of their diagnoses23–25.

These inconsistencies were observed to increase significantly in specific scenarios, such as the background noise scenario at 55 dB(A), where the percentage of inconsistent responses reached 25% of the total autistic sample users.

In contrast, the questionnaire was completed successfully and without substantial inconsistencies by the TD group, who managed to complete it autonomously in all investigated conditions.

Comparison of the predicted and observed thermal sensation

Questionnaires were completed by all users. They were asked to respond by using a 7-point evaluation scales (interval scales from − 3 to + 3 for Thermal Sensation Vote—TSV). Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) was evaluated as suggested by EN ISO 77305 and ASHRAE Standard 552. Clothing insulation index (CLO) and type of metabolism (MET), where metabolic rates assumed 1.2 for resting activities, 1.7 for active metabolism, for each individual was estimated according to the questionnaires.

Firstly, an analysis was conducted to compare PMV with TSV for each group of individuals across all scenarios122.

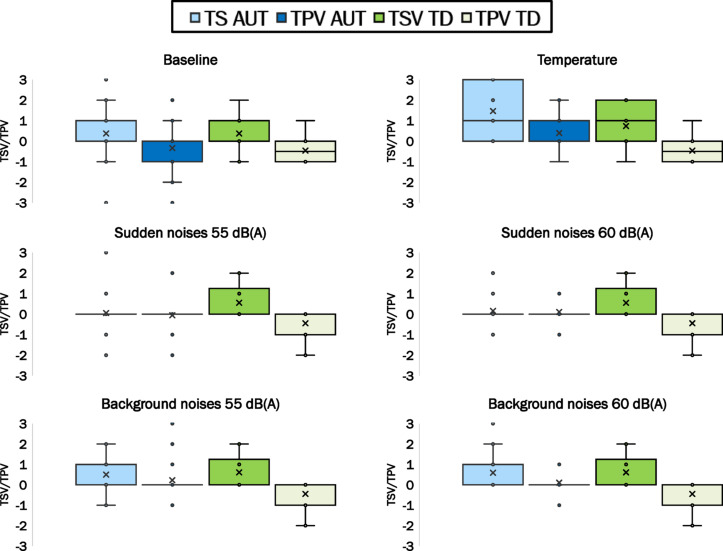

As illustrated in Fig. 5, it is evident that, in most cases, PMV seems to be unsuitable to predict accurately thermal sensation, typically underestimating it for autistic individuals. In contrast, for TD individuals, PMV results generally aligned with the reported thermal sensations. Additionally, the dispersion of TSV values within the AUT group is significantly broader compared to the TD group, which displays a more uniform distribution.

Fig. 5.

TSV\PMV from collected votes and measured values.

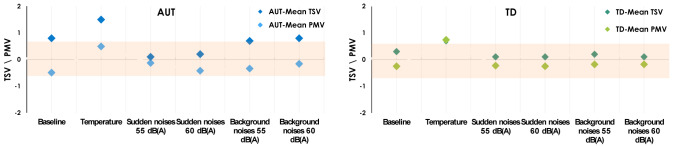

This discrepancy becomes even more pronounced when the mean values of TSV and PMV (denoted by an "x" on the boxplot in Fig. 5) for both TSV and PMV are extracted and analysed for each group and scenario. The visualization focusing solely on the mean values is presented in Fig. 6. The orange highlighted section shows the thresholds according to the ASHRAE-55 for PMV.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the mean values of TSV and PMV for AUTs and TDs.

The analysis underscores the different thermal sensation between the two groups. This suggests that TSV and PMV may not be used to evaluate thermal sensation of autistic individuals. In fact, although the NDs PMV in the baseline condition is similar to that of the TDs, the TSV of the NDs in the same environmental conditions is no longer comparable to the TDs’ one.

This corroborates the findings discussed previously regarding the autonomous compilation range described in Table 4 and also highlights that the thermal sensations of the autistic group (AUT) cannot be compared to those of TDs. Additionally, it shows that as environmental conditions vary, the autonomous responsiveness of autistic individuals is significantly reduced, affecting the reliability of questionnaire responses.

Comparison between the sensation and the preference of the acoustic environment

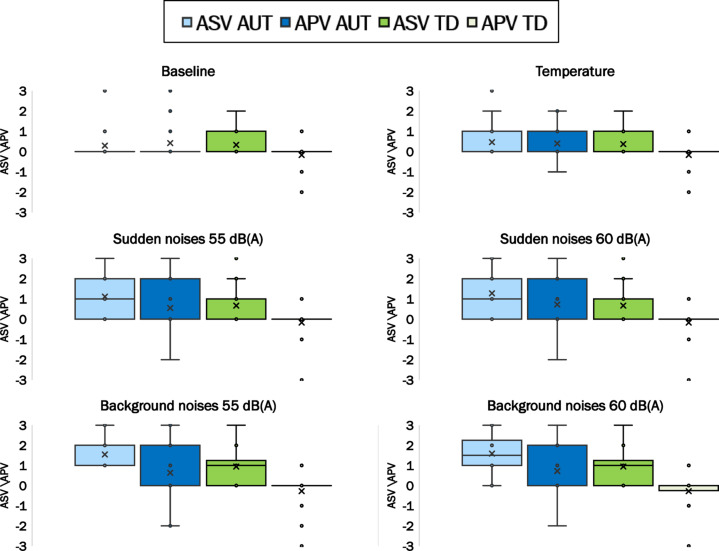

In this section, the results on acoustic sensation (Acoustic Sensation Vote—ASV) will be compared with those on acoustic preference (Acoustic Preference Vote—APV). Acoustic Sensation Votes range from 0 (quiet environment) to + 3 (very noisy environment), while Acoustic Preference Votes range from -3 (I would prefer the environment to be much quieter) to + 3 (I would prefer the environment to be much noisier)123.

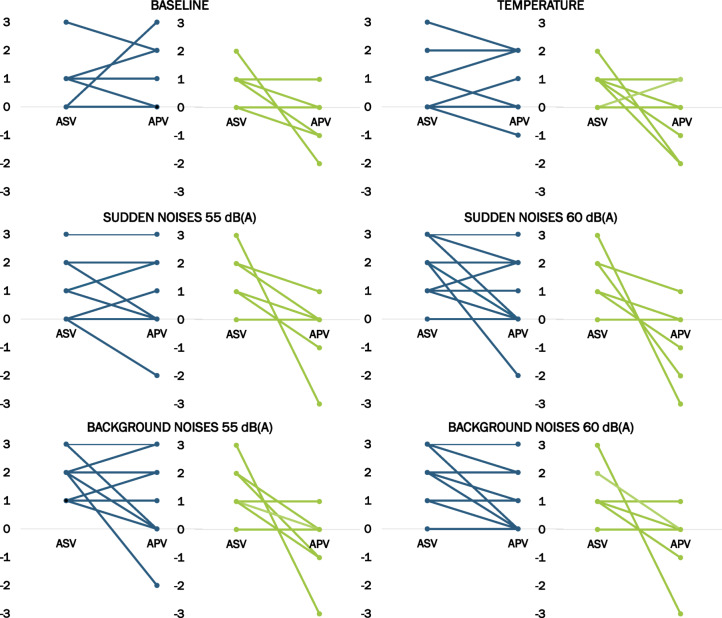

The results shown in Figs. 7 and 8 highlight clear discrepancies between the two user groups—Autistic individuals (AUTs) and Typically Developed individuals (TDs)—in both Acoustic Sensation Votes (ASVs) and Acoustic Preference Votes (APVs) across varying acoustic scenarios. ASVs from AUTs consistently exhibit greater variability than those from TDs, especially in conditions involving acoustic changes (i.e., Sudden Noises and Background Noises), where the variance is noticeably higher for the AUT group.

Fig. 7.

Comparison between the Acoustic Sensation Vote – ASV (0–3) and Acoustic Preference Vote – APV (− 3, + 3) of AUTs and TDs across the six scenarios.

Fig. 8.

Acoustic Sensation Votes (0, quiet ➜ 3, very noisy) and Acoustic Preference Votes (− 3, preference of quieter env. + ➜ 3, preference of noisier/louder env.) for each scenario. Lines connect individual ASV (left) to corresponding APV (right). A top-left to bottom-right trend (high ASV to low APV) indicates coherent responses, commonly seen in TDs. Diverging or inconsistent trends are frequent among AUTs, especially under acoustic changes (Sudden and Background Noises at 55/60 dB(A)).

It is important to consider that ASVs range from 0 to 3, indicating increasing levels of perceived noisiness, while APVs range from -3 (much quieter preferred) to + 3 (much louder preferred). Logically, when an environment is perceived as noisy (ASV between 1 and 3), one would expect a neutral or negative preference (APV between 0 and − 3), reflecting a desire for an unchanged or quieter setting.

This expected alignment between acoustic sensation and preference is relatively consistent among TDs. In their case, when ASVs increase, APVs tend to decrease accordingly, as shown by the negative slope in user trend lines—higher ASVs on the left correlate with lower APVs on the right.

However, this coherence is often absent in the AUT group. Many AUT individuals (Fig. 8) display irregular patterns, such as simultaneously reporting high ASVs and high APVs, or low ASVs with high APVs, suggesting a complex and less predictable relationship between their perception and preference. This inconsistency is particularly evident in scenarios involving acoustic modifications, including both levels of sudden and background noises (55 dB(A) and 60 dB(A)). Moreover, such divergence reinforces the broader observation that AUT participants did not always provide consistent responses throughout the administration of the scenarios, especially when acoustic conditions were altered.

Results of the attention tasks

The attentional test was administered to both the control group (TD) and the autistic group. Below are delineated the outcomes derived from three attentional tasks, each corresponding to the six distinct environmental conditions (Scenarios).

Statistical analyses (Appendix C—Supplementary Material) were conducted to evaluate task-specific performance differences between the baseline scenario and other environmental conditions for both AUT (Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material—Appendix C, Supplementary Material) and TD (Table 7—Appendix C, Supplementary Material) groups. The results indicate that the autistic group exhibits significant differences in alertness performance across acoustic scenarios compared to the baseline, a pattern not observed in the TD group, where performance remains stable regardless of scenario changes. Furthermore, while the AUT group shows no significant differences in reaction times for the go/no-go task, there is a marked increase in errors when comparing the baseline to scenarios involving noise levels at 55 dB(A) (including both background and sudden noises). In contrast, the TD group’s reaction times and error rates remain consistent across all scenarios.

These findings are further illustrated by the boxplot visualizations discussed in the subsequent sections.

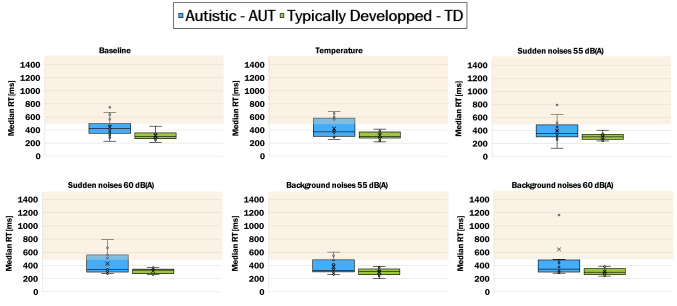

Boxplots (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) represent the distribution of results, distinguishing the autistic cohort and the control (TD) group.

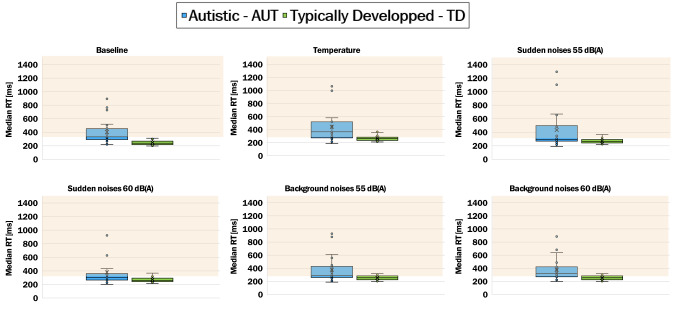

Fig. 9.

Alertness median of the reaction time distribution.

Fig. 10.

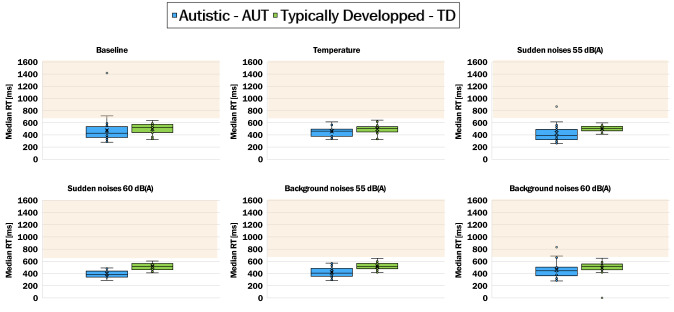

Go/no-go median of the reaction times distribution.

Fig. 11.

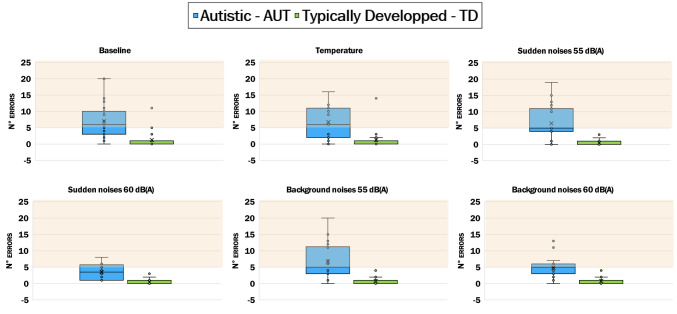

Go/no-go errors distribution.

Fig. 12.

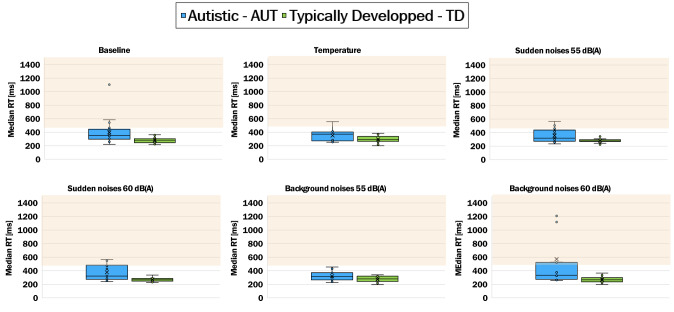

Covert shift attention median of the reaction time—valid stimulus detection.

Fig. 13.

Covert shift attention median of the reaction time—invalid stimulus detection.

The TAP’s Norms Tables111 reports the critical threshold above which attentional performance is deemed critical (yellow area in the graphs), represented with a darker background in the figures Each task has been examined to discern its impact on parameters identified by the Test of Attentional Performance Manual124 as indicative of attentional state.

In the analysis of the alert attentional component only the findings of the median of the response time (RT) are presented, as RT is the main parameter that is representative according to the Norms Tables111 (Table 2). Although the alerting task comprises both tonic and phasic components, the TAP yields a single, well-defined index representing overall alerting performance. The median response time from the first task is analysed below.

A preliminary descriptive analysis of the alertness as defined in Table 2 (Fig. 9) shows that the test effectively distinguishes between the two user groups, aligning with expectations for a diagnostic test. The TD group consistently has an average of the median of the response time (denoted by an "x" on the boxplot graph) below the maximum recommended threshold, and the group’s response variability is narrow. Conversely, the AUT group exhibits greater heterogeneity and response dispersion, with the average of the median response times frequently exceeding the maximum threshold recommended. This variability and heterogeneity in response times may be influenced by the diverse range of comorbidities diagnosed within the autistic user sample.

Secondly, the TD group’s performance remains relatively constant under varying conditions, indicating minimal impact on alertness. In contrast, the autistic group alertness appears to be significantly affected by changes in environmental conditions.

As for the go/no-go attentional task, results are showed in Figure 10, for the median reaction time and Figure 11 for the number of errors. In this case, the median response times from the go/no-go task indicate that the TD group is slightly slower and less performing than the AUT group. However, examining the error data from the go/no-go task reveals that the TD group’s responses are more accurate, with a lower degree of error. In contrast, the AUT group demonstrates greater impulsiveness in their responses to the visual stimuli, resulting in a higher mean number of errors and a greater dispersion of errors. Again, the dispersion of errors in the go/no-go task could be attributed to the wide array of comorbidities diagnosed within the autistic sample.

.

Figures 11 and 12 show the results of covert shift attention and response times corresponding to the valid and invalid stimuli. The results of the covert shift attention task indicate that the attentional performance of the AUT group does not vary substantially from that of the TD group in identifying both valid and invalid stimuli. Both groups generally perform within the acceptable range, with the AUT group exceeding the maximum recommended threshold in only one instance.

Discussions

In this section the results scenario by scenario by cross-referencing what is inferred from the questionnaires and PMV analysis and then with attentional tests results are discussed. The analysis will focus on the comparison with the baseline scenario and the other ones and on the comparison within the same scenario between the two groups of users.

Baseline scenario (scenario 1)

Analysis of questionnaire responses (Figs. 5, 6, 7) regarding the baseline conditions indicates different perceptions among the two groups of the thermal and acoustic environment. The perceived differences in the thermal environment may be attributed to variations in clothing types, as evidenced by the lighter average clothing worn by the AUT group (Table 3). However, this finding seems inconsistent with the expected prevision (Fig. 6—PMV AUT and PMV TD), which suggests both groups are within the comfort zone at the initially set temperature. This inconsistency is underscored by notable percentages of both non-autonomous responses (16%) and answers provided across AUT response forms (Table 4). This percentage encompasses all responses from the autistic group who, at the initial temperature, reported feeling warm and expressed a desire for an even warmer environment through the questionnaire. From the outset, a notable initial incompatibility emerged in administering the questionnaires to the AUT group. Although this was observed in a small percentage of cases compared to others, the issues included both inconsistencies in responses and a lack of autonomy in completing the questionnaires, despite the professional caregivers being specifically trained for this task. Furthermore, under initial conditions, both the sensations and preferences for AUTs appear to align with those of TDs, with the environment being evaluated as quiet (Fig. 7).

When administering the attentional tests, the following considerations for the initial conditions were noted. In the controlled environment’s baseline condition, neither group surpasses the tolerance threshold outlined in the TAP Manual111 during attentional assessments. However, even under these initial controlled conditions, discernible differences between the two user groups are evident. Figure 9 illustrates distinct groupings based on response times during the alertness evaluation. Similarly, the go/no-go task reveals differences not only in reaction times (Fig. 10), but also in the number of errors (Fig. 11), highlighting disparate performance levels among the AUT and TD occupants. Furthermore, in the covert shift attention task, significant differences in reaction times between the two groups are observed (Figs. 11, 12).

This finding corroborates some previous literature125 which highlights how the TAP tests is capable to discern between TD and AUT users, in standard environmental conditions. In addition, these results also confirm that the authors’ choice of the TAP test was a good one, also in different environmental scenarios. Moreover, these results suggest that at 52 dB(A), autistic individuals perform well, and it can be hypothesized that their performance would be even better at lower levels. This aligns with existing literature, although it should be noted that these studies did not concern typically developing individuals.

Temperature variation—(scenario 2)

When subjected to a summer temperature of approximately 28.5 °C, the two user groups exhibit significant differences:

From the perspective of the questionnaires, the data reveal that while the TD group’s thermal sensation results are consistent with their generally neutral preferences, the AUT group’s PMV scores tend to underestimate the actual thermal sensation (Fig. 5). This discrepancy is further illustrated by the mean values presented in Fig. 6. From an acoustic standpoint (Fig. 7), although the sound conditions remain consistent with the baseline, the AUT group not only assigns higher sensation ratings to the acoustic environment but also exhibits a preference for a slightly noisier environment. Moreover, the percentage of non-autonomous respondents has doubled compared to the initial condition (Table 4), accounting for 32% of completions, indicating an increase in proxy-driven valuations.

The typically developing (TD) group’s performance (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12) appears comparable to that in the initial conditions (baseline scenario). In contrast, the AUT group’s performance appears to be markedly affected by the temperature increase, evidenced by changes in reaction times of alertness (Figs. 9 and 12) and an increase in the number of errors (Fig. 11).

This scenario highlights a clear discrepancy between the two user groups when exposed to typical summer temperatures. There is also evidence of a sharp decrease in the AUT group’s ability to respond independently to questionnaires and the underestimation of the PMV for the thermal sensation of NDs. This further confirms the necessity of direct methods, such as attentional testing, to obtain direct feedback from NDs. Additionally, it shows that the attentional performance of the AUT group is significantly impacted by summer temperature exposures, unlike the TD group.

Sudden noises 55 dB(A)—(scenario 3)

When adding sudden noises at 55 dB(A) over the baseline conditions, several observations can be drawn:

The questionnaire responses reveal that, from the thermal point of view, the AUT group provides more varied feedback compared to the TD group, which consistently perceives the environment as uniformly neutral and comfortable, despite the thermal conditions being nearly identical to the baseline scenario (Figs. 5, 6). Additionally, the PMV continues to underestimate the thermal sensation of the AUT group, whereas the PMV assessments for the TD group align with their reported sensations (Fig. 6). In terms of responses to acoustic-related questions (Fig. 7), the AUT group, despite evaluating the environment as noisy, paradoxically expresses a preference for an even noisier setting. Conversely, the TD group, while recognizing the environment as slightly noisy, does not indicate any particular preference for changes in the acoustic conditions. Indeed, the AUT group demonstrates an increase of non-autonomous responses (27%) and inconsistencies (16%) when completing the questionnaire also if supported by trained caregivers (Table 4).

From the attentional performance point, the TD group does not exhibit decreased attentiveness (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12) when exposed to sudden noises at 55 dB(A), with results comparable to the baseline scenario. On the other hand, AUT group demonstrates an increase in reaction time, particularly in alertness (Fig. 9 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material—Appendix C, Supplementary Material) and a higher number of errors in the go-no-go task (Fig. 11 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material—Appendix C, Supplementary Material), indicating a notable decline in performance compared to baseline conditions.

Exposure to sudden noises highlights an escalation in differences between the two groups compared to baseline conditions, with parameters exceeding the recommended minimum threshold for attention. However, it is also underscored a considerable variability in non-autonomous completions and inconsistencies, indicating that direct feedback from comfort questionnaires from the autistic user group under these conditions may not be reliable.

Sudden noises 60 dB(A)—(scenario 4)

With the introduction of sudden noises at 60 dB(A), the following consideration can be made:

Looking to the questionnaire results, regarding the thermal environment, the AUT group’s responses (sensation) do not align with the expected PMV values, whereas the TD group’s responses are consistent with PMV predictions (Figs. 5, 6). Additionally, the AUT group’s sensation ratings exhibit greater dispersion compared to those of the TD group, a contrast to the baseline condition where the thermos-hygrometric conditions were similar. From an acoustic environment perspective (Fig. 7), the AUT group, despite perceiving the environment as noisy, expresses a preference for an even noisier setting. This preference is not observed in the TD group. Moreover, as shown in Table 4, for the AUT group, 20% failed to fill out the questionnaire independently and 12% despite being supported by trained caregivers provided inconsistent answers about the sound environment, as just mentioned.

When administering the attentional test, it can be seen that the TD group maintained relatively consistent performance levels compared to the initial conditions (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12). In contrast, the AUT group’s attentional performance in this scenario showed slight differences compared to the 55 dB scenario. Surprisingly, higher sound levels appeared to have a slightly lesser impact on AUT users’ alertness (Fig. 9 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material—Appendix C, Supplementary Material), but no significant differences in go/no go errors (Fig. 12 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material—Appendix C, Supplementary Material). This could be attributed to autistic users potentially anticipating the subsequent acoustic condition, given that the two sudden noise conditions were conducted in consecutive weeks. Consequently, users may have arrived more prepared for the environmental scenario investigated the following week. This may highlight the capacity of autistic individuals to adapt to situations and to the acoustic stressor, if it is reiterated in the same controlled conditions as the first time, just varying its acoustic level.

Background noises 55 dB(A)—(scenario 5)

When the two groups are exposed to background noise at 55 dB(A) the following considerations can be made:

The PMV assessment once again appears to underestimate the thermal sensation reported by the AUT group, while it generally provides reliable results for the TD group (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the AUT group’s sensation ratings exhibit a much wider dispersion compared to the TD group, which tends to favor a more neutral assessment. This discrepancy becomes even more pronounced when considering the average values alone (Fig. 6). From an acoustic environment assessment perspective (Fig. 7), the AUT group consistently shows differences in the perception of the sound environment compared to the TD group, with preferences that are often inconsistent with their reported sensations (e.g., rating the environment as noisy but preferring an even noisier setting). This inconsistency, along with an increase in non-autonomous responses, is further corroborated by the findings in Table 4

From the attentional performance perspective, The TD group shows no discernible change compared to the baseline or the other scenarios (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12). On the other hand, while less affected than in the sudden noise scenario at the same levels, the AUT group surpasses recommended thresholds in both the median of the response time for the alert task (Fig. 9 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material) and the number of errors in the go-no-go task (Fig. 11 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material—Appendix C, Supplementary Material). Furthermore, the dispersion of responses in the background noise scenario appears slightly more compact compared to the sudden noise scenario reproduced at the same levels in the alert task and in the detection of invalid stimuli for the cover shift attention task. However, the dispersion appears to remain consistent across both scenarios in terms of median of the reaction times and errors committed in the go-no-go task.

Background noises 60 dB(A)—(scenario 6)

Even in the case of the background noise scenario at 60 dB(A), it is evident that the differences between the two user groups sharply increased compared to the initial conditions:

As in previous scenarios, but to a slightly greater extent, the PMV assessment regarding the questionnaire appears to underestimate the thermal sensation responses for the AUT group, while the PMV predictions continue to align closely with the sensations reported by the TD group (Figs. 5, 6). Additionally, there is a noticeable wide dispersion in the AUT group’s thermal sensation responses, whereas the TD group’s responses remain more compact with few outliers (Fig. 5. In terms of acoustic environment evaluation (Fig. 7), the AUT group exhibits considerable variability and inconsistencies between sensation and preference (e.g., perceiving the environment as noisy while many still express a preference for an even noisier setting). These inconsistencies, as reflected in Table 4, are also associated with a significant percentage (40%) of individuals who are not autonomous in completing the assessments.

Proceeding to analyze the attentional results to assess the impact of the sound scenario on the AUT group, it becomes evident that the performance of the AUT group continued to be impacted in attentional components measured by the median reaction time of alertness (Fig. 9 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material) , but not in the number of errors in the go-no-go task (Fig. 7 and Table 6—Appendix C, Supplementary Material). On the other hand, the typically developing (TD) group maintained consistent performance across all three tasks (Fig. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and Table 7—Appendix C, Supplementary Material). These results highlight how this scenario intensifies performance differences between the two user groups and underscores how the investigated environment disproportionately impacts sustained attention among AUT users, surpassing thresholds in all three attentional tasks. It should also be noted that while the dispersion of median of the response time and errors appears to decrease in the alert and go-no-go tasks, there is an increase in response dispersion in the case of valid stimulus identification during the covert shift attention task, which is the only scenario investigated where this occurs. This suggests that the addition of background noise at 60 dB(A) may have a greater impact on long-term attention and autistic user fatigue, particularly affecting the third and the final assigned task (covert shift of attention), as well as the immediate attentional alertness (arousal).

An interesting pattern emerged in the 52 dB(A) condition, where a slight improvement in attentional performance was observed in the AUT group. This result may be interpreted through the lens of stochastic resonance (SR)—a phenomenon whereby a certain level of background noise can enhance signal detection in nonlinear systems such as the human brain126. While noise is typically considered a performance disruptor, SR suggests that low levels of random noise may facilitate cognitive processing, particularly when internal neural noise is already high, as is hypothesized in autism. These findings resonate with recent literature127, which posits that modest external noise may aid performance by optimizing signal processing, whereas higher levels (e.g., 55–60 dB(A)) exceed the threshold and instead lead to overload, thus degrading performance.

Answers to the scientific questions raised

Having discussed the results of the administration of the attention tests, it is important to understand how these findings contribute to the research questions initially inquired.

Can environmental conditions (temperature, noise levels, etc.) influence the attentional performance of autistic individuals?

The study highlights that variations in environmental conditions significantly impact the attentional performance of autistic individuals. Specifically, increases in temperature and the introduction of both sudden and background noises negatively affected their ability to focus. These findings emphasize the necessity of using standardized tests specifically designed for autistic individuals, which do not impose IQ thresholds and are adaptable to different cognitive profiles. Implementing such inclusive methods ensures accurate assessments of attentional performance without relying on proxies.

Can direct questions included in conventional and standard comfort questionnaires be answered by autistic individuals?

As shown in both the results and discussion, comfort questionnaires do not provide a reliable means of assessing indoor comfort for autistic individuals. A significant portion of autistic participants was unable to complete the questionnaire independently, particularly when environmental conditions changed. Even under stable conditions, inconsistencies emerged in their responses, unlike the typically developing (TD) group, which provided more consistent answers. These findings align with existing literature128–130, which suggests that standardized questionnaires designed for TD individuals may pose challenges for autistic users.

Do the results of administered questionnaires align with the expected results?

The responses from autistic individuals did not align with conventional comfort models. For instance, in thermal assessments, Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) models consistently underestimated the actual thermal sensations reported by the AUT group, while they remained accurate for TD participants. In terms of acoustics, AUT participants exhibited conflicting preferences—often reporting an environment as noisy yet expressing a preference for even noisier conditions. Additionally, an increasing number of AUT participants required caregiver assistance to complete the questionnaire as environmental conditions changed, further indicating that standard methods fail to capture their true comfort perceptions.

Limitations of the study

This study has limitations that must be acknowledged to contextualize its findings.

First, the sample size was limited, though it aligns with the scope of previous studies on the topic. Another limitation is the complexity introduced by the large number of different comorbidities. The limited availability of studies addressing these conditions and their comorbidities results in a possible lack of comparable scenarios, which may result sometimes in complicating the interpretation of results. This issue highlights the need for more comprehensive studies that investigate a wider range of conditions and their unique responses to indoor environments.

The study also required an extensive number of trials with time intervals between administrations to ensure the repeatability of attention tests, extending the research period to six months. This approach ensured that participants’ stress levels remained manageable but limited the number of environmental scenarios that could be explored. Additionally, the selection of scenarios was also influenced, beside the few information identified in the literature review, by constraints at the care facility, restricting the investigation to thermal and acoustic environments while excluding air quality and visual conditions.

Conclusions

The study investigates the tools for studying the indoor thermal and acoustic comfort of autistic individuals. By engaging users and practitioners in participatory workshops, a rigorous analysis procedure was established, involving 25 autistic users featuring 17 different comorbidities and 25 typically developing users over a six-month period. This approach enabled all individuals to independently complete attentional tests across various environmental conditions, while environmental parameters were passively monitored. Two groups of 25 people (a total of 50 participants) were tested across 6 different scenarios, resulting in 300 tests and 300 questionnaires. Participants from both user groups were matched based on age, thanks to voluntary participation. A comprehensive literature review along with the support of a team of psychologists and educationalists, identified an adaptable attentional test (already validated by science) suitable for users across age groups, autonomy levels and cognitive abilities. Thus, Attentional Performance test served as a valuable tool.

Key highlights of the research are summarized as follows:

Completing the questionnaires posed significant challenges for autistic individuals, particularly in scenarios characterized by environmental variation from the baseline condition. The percentage of autonomous responses ranged from a minimum of 16% in the baseline scenario to a maximum of 40% under background noise conditions at 60 dB(A). Notably, response inconsistencies reached up to 25% in scenarios with background noise at 55 dB(A), highlighting the demanding nature of these environments in supporting autonomous response behaviour among individuals on the autism spectrum. These results confirmed such as a standard tool to evaluate indoor comfort for typically developed individuals could be challenging for autistics.

Autistic users demonstrated improved performance and a higher degree of autonomy at 52 dB(A) (Baseline Scenario) if compared to all the sound scenario explored in this study, with a reduced rate of response inconsistencies and lower omissions and late responses rates. It is expected that at noise levels below 52 dB(A), their performance and autonomy would further improve.

The attentional performance of the autistic group showed significant impact under all the varied environmental conditions, particularly in tasks related to alertness (ability to swiftly and effectively respond to the surrounding environmental stimuli) and go/no go (ability to suppress the automatic responses – response inhibition).

Analysis revealed substantial differences between typically developed and autistics. While typically developed individuals experienced slight discomfort with environmental changes, their attentional performance remained stable. In contrast, autistic individuals’ questionnaire responses did not consistently align with attentional test results. Moreover, inconsistencies in questionnaire responses highlighted the need for a standardized tool to directly collect reliable data, particularly for autistic individuals.

When the autistic group was exposed to typical summer temperatures of 28 °C and sudden noises at both 55 dB(A) and 60 dB(A), a notable decrease in attention performance was observed referring to the recommended attention thresholds of the TAP test. Specifically, there was an increase in reaction times and a higher frequency of errors across various tasks.

The unevenness of the performances of the two groups increased, since the autistic group’s performance also declined under continuous background noise at 55 dB(A), with a more pronounced decrease in performance at 60 dB(A), especially in tasks demanding sustained attention and endurance. In contrast, the typically developed group maintained homogeneous performance metrics across all six environmental scenarios, probably indicating a greater adaptability to these environmental stressors. However, this result may have been influenced by the training in questionnaires and environmental variations provided to typically developed users.

Literature indicates that the Test of Attentional Performance (TAP) is effective in differentiating between autistic (AUT) and typically developing (TD) individuals125. However, the results here presented demonstrate that the two groups not only differ in their baseline responses but also exhibit distinct reactions to environmental stress. Indeed, it is the environmental stressor that exerts a significant, yet distinct, impact on their attentional performance. The results here discussed further demonstrate that, when AUT group is exposed to variation of the environment, there is an increase in the dispersion of their responses and sometimes of their accuracy (errors in the go/no go task), suggesting a differential sensitivity to stress. This highlights the nuanced effect of environmental conditions on AUTs compared to TDs, underscoring the importance of considering these differences in both research and practical applications.

The findings also indicate that even minor environmental variations can impact the performance of autistic individuals, potentially affecting their ability to complete specific tasks. This should be considered when conducting psychological assessments, as environments designed for such assessments are often not suited for accommodating these variations.

The observations indicate that both sudden and background noise levels at 55 dB(A) and 60 dB(A) negatively impact autistic individuals compared to the 52 dB(A) baseline scenario, suggesting that real-world environments such as schools, open-plan offices, and hospitals should avoid exceeding this threshold. Similarly, response times at 28 °C exceed the recommended limits established by the TAP, with increased motor stereotypies and echolalia observed compared to the 25 °C condition, highlighting the need to maintain thermal conditions within optimal ranges to support autistic users’ well-being and cognitive functioning.

In conclusion, the use of attention tests enriches the understanding of autistic users’ needs. These insights contribute significantly to the development of more inclusive and adaptable spaces, thereby enhancing overall user needs and well-being.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was co-funded by the European Union and Interreg Italy-Austria BeSENSHome project, ITAT-11-016 CUP: I53C23001720007. This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano. The Authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Michele Borghetto of AUSL Veneto for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this study. We are deeply appreciative of Elena Bulfone, President of Fondazione ProgettoAutismo, as well as Dr. Martina Dordolo and Dr. Alessia Domenighini, for their extensive help and unwavering support. Their contributions were instrumental in facilitating this research, and we are especially thankful to Fondazione ProgettoAutismo for hosting the study in their facility. This research would not have been possible without their collaboration and dedication to advancing our understanding of autistic populations.

Author contributions

A.M. conceived the research, designed the methodology and study, wrote the draft manuscript, finalized the writing, and handled data visualization. M.C. supervised the study, reviewed the writing, and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. A.G. provided supervision and reviewed the writing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mujan, I., Anđelković, A. S., Munćan, V., Kljajić, M. & Ružić, D. Influence of indoor environmental quality on human health and productivity: A review. J. Clean. Prod.217, 646–657 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.ASHRAE, American society of heating, refrigerating and air-conditioning engineers. ASHRAE Handbook-Fundamentals (2017).

- 3.Fanger, P. O. Assessment of man’s thermal comfort in practice. Occup. Environ. Med.30(4), 313–324 (1973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]