Abstract

Differentiating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) remains challenging, particularly when clinical and serological markers are inconclusive. Imaging provides critical insights, with MRI and dual-energy CT iodine maps highlighting key distinctions. Both conditions share inflammatory features such as capsular synovitis, tenosynovitis, and bone marrow edema. However, periarticular inflammation is often a strong indicator of PsA. This reflects their differing inflammatory targets: RA primarily involves the synovium, whereas PsA targets the enthesis. This distinction contributes to the broader bone marrow edema seen in PsA and explains inflammatory changes at the distal interphalangeal joint and dactylitis, which are characteristic of PsA but not RA. Recognizing these inflammatory patterns and distributions is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment guidance.

Keywords: Inflammatory arthritis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Psoriatic arthritis, Synovitis, Enthesitis

INTRODUCTION

Recent developments in treatment options that elicit different responses in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) underscore the importance of accurate diagnosis of these common types of inflammatory arthritis involving the peripheral joints [1]. However, distinguishing between these conditions can be challenging. To date, there are no diagnostic criteria that enable clinicians to differentiate between these types of arthritis with consistent accuracy. Therefore, diagnosis should be made by experts who consider the patient's history, clinical Enthesitissymptoms, blood tests, and imaging findings. RA and PsA share symptoms, including joint swelling, stiffness, and pain [2]. Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) are biomarkers for RA, but 15% to 20% of patients with RA are negative for both [3], while RF can be positive in 20% and ACPA in 7.9% of patients with PsA [4,5]. Skin manifestations are a strong predictor of PsA, although 20% to 25% of patients with PsA experience joint symptoms preceding or coinciding with skin involvement [6,7]. With such a challenging diagnosis, clinicians need as many clues as possible. Imaging provides reliable and objective clues and is more sensitive than physical examination alone in detecting inflammatory lesions [8,9]. Therefore, radiologists familiar with the detailed imaging findings of RA and PsA can provide valuable information to the referring physician.

Characteristic structural changes that appear in the late phase of inflammatory arthritis can occur in both RA and PsA, often facilitating a definitive diagnosis. However, in clinical practice, making an accurate early diagnosis before the onset of structural changes is crucial but challenging. Therefore, in this article, we review the imaging spectrum of both types of arthritis on MRI and dual-energy CT (DECT) iodine mapping with a focus on the differing appearances of inflammatory lesions in RA and PsA.

Dual-Energy CT Iodine Mapping for Inflammatory Arthritis

DECT is an imaging technique that acquires data using two different X-ray energy levels, allowing for material decomposition and selective visualization of iodine distribution. The iodine map enhances the detection of contrast media accumulation, making it particularly useful for assessing inflammatory lesions in inflammatory arthritis [10,11].

Previous studies have reported that, when using contrast-enhanced MRI as the reference, DECT iodine mapping has a sensitivity of 0.78 and a specificity of 0.87 for detecting inflammatory lesions in peripheral arthritis [10]. In addition to lesion detection, DECT iodine mapping enables quantitative assessment of the therapeutic response by measuring iodine uptake in affected joints, which correlates with clinical improvement [12].

Although radiation exposure and a limited ability to detect bone marrow edema (BME) remain its primary drawbacks, the rapid imaging capability of DECT makes it less susceptible to motion artifacts and allows for true orthogonal-plane reconstruction, which can facilitate detailed assessment. Alongside MRI, DECT iodine mapping is a valuable modality for differentiating inflammatory lesions between RA and PsA [13], and this review includes representative DECT images to illustrate these differences.

In this article, we use PsA as a representative type of peripheral spondyloarthritis (SpA) to illustrate various imaging findings in contrast to RA. The imaging characteristics of PsA described in this review are not specific to PsA and can also be observed in other forms of peripheral SpA, given their shared pathophysiological features.

Differences in Inflammatory Targets in RA and PsA

When typical manifestations of RA and PsA occur in large joints, such as the knee, their imaging features differ significantly (Fig. 1). However, differentiating between RA and PsA becomes more difficult when it involves smaller, more commonly affected joints such as the finger joints. This is because the synovium (the main target in RA) and the enthesis (the primary target in PsA) are anatomically very close in small joints. This close relationship is not merely anatomical but also functional, referred to as the synovio-entheseal complex (SEC) (Fig. 2A). The SEC plays a crucial role in alleviating tensile and frictional stress at the enthesis, facilitating smooth joint movement.

Fig. 1. Typical manifestations of RA and PsA in the knee joint. A: Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI of the right knee in a 76-year-old female with RA shows intense enhancement within the joint, suggesting synovitis. B: Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI of the left knee in a 65-year-old male with PsA shows abnormal enhancement at the enthesis of the quadriceps tendon (arrow), suggesting enthesitis. RA = rheumatoid arthritis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

Fig. 2. Synovio-entheseal complex of the interphalangeal joint. A: Sagittal illustration of the interphalangeal joint shows two types of entheses: classical enthesis, where the tendon attaches to bone (black arrow), and functional enthesis, where the tendon experiences friction against the articular cartilage (white arrow). The synovium, which lines the deepest layer of the joint capsule, in close proximity (arrowhead). B: Synovitis, a typical manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis, shows inflammation within the joint (arrow). C: Enthesis are located more peripherally than the synovium, and enthesitis tends to extend both within the joint and periarticularly. Compared to synovitis in (B), the red areas indicating inflammation extend more prominently to the joint margins.

The SEC includes two types of entheses: classical entheses, where tendons or ligaments attach directly to bone, and functional entheses, where tendons generate friction against bone or cartilage. Functional entheses contain sesamoid fibrocartilage on the tendon side and periosteal fibrocartilage on the bone side, helping to distribute mechanical stress [14]. These structures are particularly important in joints where repetitive stress can cause microdamage [15]. Through the SEC, enthesitis can easily spread to the synovium and cause synovitis, which makes it difficult to differentiate between RA and PsA [13].

However, the differing inflammatory targets can result in distinct imaging features. A prominent difference is periarticular inflammation in PsA, which is not typically seen in RA (Fig. 2). In the MRI scoring system developed by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT), periarticular inflammation is included for PsA, but not for RA [16,17].

Differences in the Distribution of Inflammation

Understanding the differences in typical inflammatory distribution between RA and PsA is helpful in making a differential diagnosis. In RA, involvement of the wrist, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints is typical and is described as a “row pattern,” referring to the involvement of multiple joints at the same level (Fig. 3) [13,18].

Fig. 3. Typical distribution in RA and PsA. A: “Row pattern” distribution typical of RA. B: Continuous coronal contrast-enhanced MRI images of the hand in a 37-year-old female with RA show involvement of MCP (arrows) and PIP (arrowheads) joints. C: Multiple joints can be involved in PsA, but distribution including the DIP joints is a key distinguishing feature from RA. D: “Ray pattern” distribution typical of PsA. E: Continuous coronal contrast-enhanced MRI images of the hand in a 52-year-old male with PsA show involvement of DIP (arrows) and PIP (arrowheads) joints. A distribution suggestive of the ray pattern is observed in the little finger. RA = rheumatoid arthritis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis, MCP = metacarpophalangeal, PIP = proximal interphalangeal, DIP = distal interphalangeal.

In PsA, involvement of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints and the “ray pattern,” which involves all joints within a particular digit, are known to be distinct from the distribution typically seen in RA (Fig. 3) [18]. However, the most common distribution in PsA is symmetrical polyarthritis, which resembles the pattern observed in RA [19]. Additionally, 12% of patients with RA are reported to have DIP involvement, more commonly observed in those with advanced age and long disease duration [20].

Capsular Synovitis

Histological differences between synovitis in RA and PsA have been documented. In RA, there is greater cellular infiltration and more marked hyperplasia of the synovial lining layer compared with PsA [21]. In contrast, PsA exhibits increased angiogenesis, along with endothelial swelling and vessel wall thickening [22].

A dynamic MRI study showed that contrast enhancement persists longer in RA compared with PsA at 15 minutes post-contrast [23]. This persistence in enhancement may reflect histopathologic changes, such as the tendency for contrast media to remain within the proliferated synovium in RA. Although conventional contrast-enhanced MRI alone is insufficient to distinguish synovitis between these two types of arthritis, the typical joint capsular synovitis in PsA is accompanied by periarticular inflammation and appears more dramatic than in RA (Figs. 4, 5).

Fig. 4. Comparison of typical capsular synovitis between RA and PsA on contrast-enhanced MRI. A, B: Coronal (A) and axial (B) images of the hand in a 75-year-old female with RA show enhancement within multiple metacarpophalangeal joints (arrows). Flexor tenosynovitis is also visible as abnormal enhancement around the flexor tendon (arrowheads). C, D: Coronal (C) and axial (D) images of the hand in a 31-year-old male with PsA show prominent enhancement at the proximal interphalangeal joint of the 3rd finger with periarticular inflammation on the ulnar side (arrows). Bone marrow edema in the proximal phalanx extends to the diaphysis (arrowhead). RA = rheumatoid arthritis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

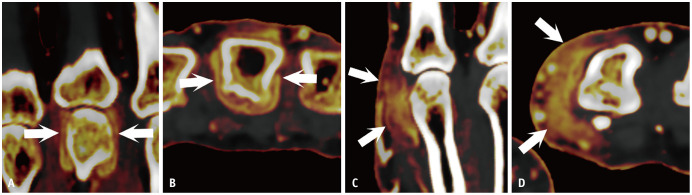

Fig. 5. Comparison of typical capsular synovitis between RA and PsA on dual-energy CT iodine maps. A, B: Coronal (A) and axial (B) images of the hand in a 75-year-old female with RA show enhancement in the 3rd MCP joint (arrows). C, D: Coronal (C) and axial (D) images of the hand in a 64-year-old female with PsA shows capsular synovitis with periarticular inflammation in the 2nd MCP joint (arrows). RA = rheumatoid arthritis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis, MCP = metacarpophalangeal.

Several studies have emphasized that periarticular inflammation is a key imaging feature for differentiating PsA from RA [24,25,26]. If the enthesis is the primary inflammatory target in PsA, capsular enthesitis may develop prior to the onset of capsular synovitis, and such cases may occasionally be encountered (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Contrast enhanced MRI of the hand in a 65-year-old male with PsA. A: Axial image shows enhancement localized to the proximal capsular enthesis of the 2nd MCP joint (arrows). Tenosynovitis is also observed in multiple flexor tendons. B: Axial image at a slightly more distal joint level than (A) shows no obvious capsular synovitis (arrows). C: Coronal image shows contrast enhancement at the proximal capsular enthesis of the 2nd MCP joint (arows), as seen in the axial image. However, no obvious capsular synovitis is identified in the same joint. PsA = psoriatic arthritis, MCP = metacarpophalangeal.

Tenosynovitis and Peritendinitis

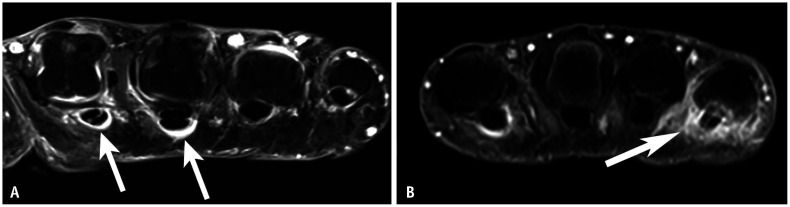

Tenosynovitis occurs in tendons with a tendon sheath, while inflammation around tendons without a sheath is typically described as peritendinitis. In the hand, the flexor tendon has a sheath up to its attachment at the distal phalanx [27]. In RA, flexor tenosynovitis is a strong predictor of early RA [28] and can be observed as abnormal fluid signal or enhancement within the tendon sheath (Figs. 4B, 7A, 8). In PsA, the development of flexor tenosynovitis can be explained by functional enthesitis between the tendon sheath and pulleys [29]. In addition to typical tenosynovitis findings, inflammation can spread to the subcutaneous area in PsA due to pulley involvement (Figs. 7B, 9). In PsA, the thickness of the pulleys—particularly the A1 and A2 pulleys—is greater than in RA or control groups [29,30].

Fig. 7. Comparison of typical flexor tenosynovitis between RA and PsA on contrast-enhanced MRI. A: Axial image of the hand in a 72-year-old male with RA shows enhancement around the flexor tendon, most prominently in 2nd and 3rd digit (arrows). B: Axial image of the hand in a 55-year-old male with PsA shows enhancement around the flexor tendon in 2nd and 5th digit. Enhancement of the 5th flexor tendon extends into the subcutaneous region (arrow). RA = rheumatoid arthritis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

Fig. 8. Axial dual-energy CT iodine map of the hand in a 27-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis shows typical flexor tenosynovitis as circumferential enhancement around the 2nd and 3rd flexor tendons (arrows).

Fig. 9. Pulley inflammation in PsA. A: Axial dual-energy CT iodine map of the hand in an 82-year-old female with PsA shows enhancement consistent with pulley structures (arrows). B: Illustration of an axial image at the metacarpophalangeal joint. On the palmar side of the FT, a fibrous band known as the pulley anchors the tendons to the bone. This structure corresponds to the enhancement area observed in (A). PsA = psoriatic arthritis, FT = flexor tendons, JS = joint space, DTML = deep transverse metacarpal ligament.

The extensor tendon was previously thought to lack a tendon sheath at the mid-metacarpal level [27]. However, synovial tissue around the extensor tendon at the MCP joint level has been reported [31], and inflammation at this location has been observed in RA and in undifferentiated arthritis prior to the development of RA [32]. Inflammation around the extensor tendon at the MCP joint is a well-known site of functional enthesitis and has been described as a specific finding for PsA compared with RA [33].

Typical functional enthesitis of the extensor tendon at the MCP joint in PsA appears as swelling and abnormal enhancement slightly proximal to the joint. This occurs because the friction site—between the extensor tendon and the metacarpal bone when the joint is flexed—shifts proximally when the joint is extended (Figs. 10, 11). Although inflammation around the extensor tendon at the MCP joint may not be considered specific for PsA, it may become more specific when extensor peritendinitis occurs at the PIP or DIP joints, where synovial tissue may be absent (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10. Extensor peritendinitis at the MCP joint level due to functional enthesitis in PsA. A: Illustration of the extensor tendon, which generates friction and causes peritendinitis during flexion, located slightly proximal to the joint. B: Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI of the hand in an 89-year-old male with PsA shows enhancement around the extensor tendon at the MCP joint (arrow). MCP = metacarpophalangeal, PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

Fig. 11. Extensor peritendinitis at various joint levels in psoriatic arthritis on dual-energy CT iodine maps. A: Sagittal image of the finger in a 42-year-old male shows swelling and enhancement around the extensor tendon slightly proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joint (arrow). B: Sagittal image of the finger in a 34-year-old female shows swelling and enhancement around the extensor tendon at the proximal interphalangeal joint (arrow). C: Sagittal image of the finger in a 45-year-old male shows prominent swelling and enhancement around the extensor tendon at the DIP joint. Abnormal enhancement within the DIP joint reflects capsular synovitis (arrow). DIP = distal interphalangeal.

Even though inflammation in RA generally occurs in synovial tissue, some studies have shown inflammation in tendons lacking a sheath, such as the interosseous muscle tendons [34,35]. The reason for this discrepancy with earlier reports remains unclear.

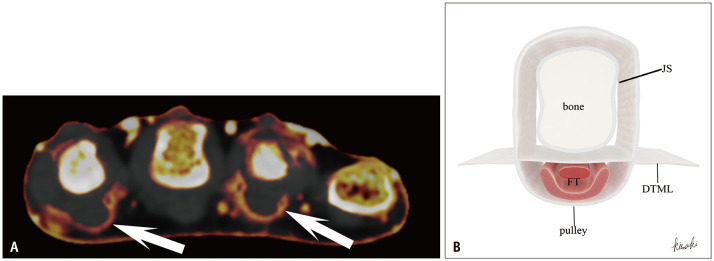

Bone Marrow Edema and Periostitis

BME is a crucial imaging finding in RA and serves as an independent predictor of future erosive progression [36]. The extent of BME may be useful in differentiating RA from PsA: RA typically shows localized BME in the subarticular area (Fig. 12A), while PsA may present with relatively extensive BME extending to the diaphysis (Figs. 4C, 12B) [24,25,37].

Fig. 12. Comparison of typical BME between RA and PsA on MRI. A: Coronal STIR image of the hand in a 44-year-old male with RA shows subarticular BME in the 2nd metacarpophalangeal joint, without extension to the diaphysis. B: Coronal STIR image of the hand in a 46-year-old female with PsA shows BME in the 5th proximal interphalangeal joint, extending into the diaphysis of the proximal phalanx (arrow). BME = bone marrow edema, RA = rheumatoid arthritis, PsA = psoriatic arthritis, STIR = short-tau inversion recovery.

BME in RA is believed to result from synovial inflammation through the bare area, where synovium directly attaches to the bone between the articular cartilage and the joint capsule. In contrast, in PsA, inflammation may originate from the enthesis of the joint capsule or collateral ligament, which are located farther from the articular surface, allowing the inflammation to reach the diaphysis.

Periostitis is frequently observed in PsA but not in RA (Fig. 13) [38]. This may relate to anatomical continuity of ligament or joint capsule fibers spreading along the bone to the periosteum, with enthesitis-related inflammation extending to the periosteum [39,40].

Fig. 13. Periostitis in PsA. Coronal contrast-enhanced MRI of the hand in a 49-year-old female with PsA demonstrates periosteal enhancement on both sides of the 3rd proximal phalanx. PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

Characteristic Complex Inflammatory Patterns in PsA

Enthesitis in PsA can sometimes result in characteristic complex inflammatory patterns. One such pattern can be observed in the DIP joint and may explain why patients with PsA with DIP symptoms often exhibit nail changes [41]. Part of the extensor tendon fibers continues beyond its attachment at the base of the distal phalanx as the superficial lamina and connects to the nail root [42]. Thus, enthesitis of the extensor tendon can extend to the nail.

Furthermore, DIP synovitis can be triggered by enthesitis through the SEC (Fig. 14). This close anatomical and functional relationship explains the strong association between nail changes and DIP symptoms in PsA—an association that is unlikely in RA. Before synovial inflammation becomes evident, PsA may also be identified by isolated inflammation of the nail bed [43]. An MRI study showed that the nail bed is thicker in patients with PsA than in those with osteoarthritis or healthy controls [39].

Fig. 14. Characteristic inflammatory complex of the DIP joint in PsA. A: Sagittal illustration of the DIP joint shows that some fibers of the extensor tendon extend from the enthesis (*) to the nail root as the superficial lamina (arrow). B: Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI of the DIP joint in a 45-year-old female with PsA shows abnormally thickened enhancement in the nail bed (white arrow) and capsular synovitis of the DIP joint (arrowhead). This inflammatory complex can be interpreted as being centered around extensor tendon enthesitis (black arrow). DIP = distal interphalangeal, PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

Another hallmark inflammatory pattern in PsA is dactylitis, or “sausage digits” (Fig. 15). Dactylitis is linked with aggressive manifestations such as joint destruction and occurs in 16%–49% of patients with PsA [44]. High-resolution MRI has shown that dactylitis is not caused solely by synovial inflammation, as seen in RA, but also involves multiple types of enthesitis and periarticular inflammation [29,45]. Therefore, dactylitis is a characteristic hallmark of PsA. While dactylitis is not observed in RA, infection can also cause diffuse digit inflammation, making it important to consider in the differential diagnosis.

Fig. 15. Dactylitis in PsA. A: Sagittal contrast-enhanced MRI of the right 5th finger in a 52-year-old male with PsA shows inflammatory lesions, such as extensor peritendinitis (arrows), capsular synovitis, and bone marrow edema, distributed throughout the digit. B: Axial images corresponding to the cross-sectional levels indicated by the lines in (A). Periarticular inflammation (arrows) and flexor tenosynovitis are also evident. PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

CONCLUSION

While RA and PsA share overlapping clinical and imaging findings, understanding the distinct inflammatory patterns and distributions is critical for accurate differentiation. Imaging plays a pivotal role in highlighting key features—such as periarticular inflammation, functional enthesitis, and characteristic patterns like dactylitis in PsA—which are less typical in RA. Radiologists with expertise in these imaging characteristics can provide valuable insights to support precise diagnosis and guide treatment strategies.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Takeshi Fukuda.

- Resources: Takeshi Fukuda, Shunsuke Kisaki, Mami Momose, Yoshinori Umezawa, Akihiko Asahina.

- Supervision: Hiroya Ojiri, Akihiko Asahina.

- Visualization: Akira Ogihara, Shunsuke Kisaki.

- Writing—original draft: Takeshi Fukuda.

- Writing—review & editing: Akira Ogihara, Shunsuke Kisaki, Hiroya Ojiri.

Funding Statement: None

References

- 1.Veale DJ, Fearon U. What makes psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis so different? RMD Open. 2015;1:e000025. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2014-000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merola JF, Espinoza LR, Fleischmann R. Distinguishing rheumatoid arthritis from psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4:e000656. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320:1360–1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahran E, Youssof A, Shehata W, Bahgat A, Elshebiny E. Predictive role of serum rheumatoid factor in different disease pattern of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Egypt J Intern Med. 2021;33:49 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirth T, Balandraud N, Boyer L, Lafforgue P, Pham T. Biomarkers in psoriatic arthritis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1054539. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1054539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogdie A, Langan S, Love T, Haynes K, Shin D, Seminara N, et al. Prevalence and treatment patterns of psoriatic arthritis in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:568–575. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T, Ohtsuki M, Sano S, Morita A, Igarashi A, Okuyama R, et al. Late-onset psoriatic arthritis in Japanese patients. J Dermatol. 2019;46:169–170. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakefield RJ, Freeston JE, O’Connor P, Reay N, Budgen A, Hensor EM, et al. The optimal assessment of the rheumatoid arthritis hindfoot: a comparative study of clinical examination, ultrasound and high field MRI. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1678–1682. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohrndorf S, Boer AC, Boeters DM, Ten Brinck RM, Burmester GR, Kortekaas MC, et al. Do musculoskeletal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging identify synovitis and tenosynovitis at the same joints and tendons? A comparative study in early inflammatory arthritis and clinically suspect arthralgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:59. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1824-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda T, Umezawa Y, Tojo S, Yonenaga T, Asahina A, Nakagawa H, et al. Initial experience of using dual-energy CT with an iodine overlay image for hand psoriatic arthritis: comparison study with contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2017;284:134–142. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda T, Umezawa Y, Asahina A, Nakagawa H, Furuya K, Fukuda K. Dual energy CT iodine map for delineating inflammation of inflammatory arthritis. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:5034–5040. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayama R, Fukuda T, Ogiwara S, Momose M, Tokashiki T, Umezawa Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of therapeutic response in psoriatic arthritis of digital joints with dual-energy CT iodine maps. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1225. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiraishi M, Fukuda T, Igarashi T, Tokashiki T, Kayama R, Ojiri H. Differentiating rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis of the hand: multimodality imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2020;40:1339–1354. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamin M, Moriggl B, Brenner E, Emery P, McGonagle D, Redman S. The “enthesis organ” concept: why enthesopathies may not present as focal insertional disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3306–3313. doi: 10.1002/art.20566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGonagle D, Aydin SZ, Tan AL. The synovio-entheseal complex and its role in tendon and capsular associated inflammation. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2012;89:11–14. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostergaard M, McQueen F, Wiell C, Bird P, Bøyesen P, Ejbjerg B, et al. The OMERACT psoriatic arthritis magnetic resonance imaging scoring system (PsAMRIS): definitions of key pathologies, suggested MRI sequences, and preliminary scoring system for PsA hands. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1816–1824. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Østergaard M, Peterfy CG, Bird P, Gandjbakhch F, Glinatsi D, Eshed I, et al. The OMERACT rheumatoid arthritis magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scoring system: updated recommendations by the OMERACT MRI in arthritis working group. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:1706–1712. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandran V, Stecher L, Farewell V, Gladman DD. Patterns of peripheral joint involvement in psoriatic arthritis-symmetric, ray and/or row? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Peters M, Barker M, Wright V. A re-evaluation of the osteoarticular manifestations of psoriasis. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30:339–345. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/30.5.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pekdiker M, Ketenci S, Sargin G. Distal interphalangeal joint involvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: where are we? Turk J Med Sci. 2024;54:766–770. doi: 10.55730/1300-0144.5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veale D, Yanni G, Rogers S, Barnes L, Bresnihan B, Fitzgerald O. Reduced synovial membrane macrophage numbers, ELAM-1 expression, and lining layer hyperplasia in psoriatic arthritis as compared with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:893–900. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espinoza LR, Vasey FB, Espinoza CG, Bocanegra TS, Germain BF. Vascular changes in psoriatic synovium. A light and electron microscopic study. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:677–684. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwenzer NF, Kötter I, Henes JC, Schraml C, Fritz J, Claussen CD, et al. The role of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in the differential diagnosis of psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:715–720. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrar DB, Schleich C, Brinks R, Goertz C, Schneider M, Nebelung S, et al. Differentiating rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic analysis of high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging features-preliminary findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2021;50:531–541. doi: 10.1007/s00256-020-03588-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marzo-Ortega H, Tanner SF, Rhodes LA, Tan AL, Conaghan PG, Hensor EM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of metacarpophalangeal joint disease in early psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38:79–83. doi: 10.1080/03009740802448833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zubler V, Agten CA, Pfirrmann CW, Weiss BG, Dietrich TJ. Frequency of arthritis-like MRI findings in the forefeet of healthy volunteers versus patients with symptomatic rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:W45–W53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieuwenhuis WP, Krabben A, Stomp W, Huizinga TW, van der Heijde D, Bloem JL, et al. Evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging-detected tenosynovitis in the hand and wrist in early arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:869–876. doi: 10.1002/art.39000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eshed I, Feist E, Althoff CE, Hamm B, Konen E, Burmester GR, et al. Tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons of the hand detected by MRI: an early indicator of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:887–891. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinazzi I, McGonagle D, Aydin SZ, Chessa D, Marchetta A, Macchioni P. ‘Deep Koebner’ phenomenon of the flexor tendon-associated accessory pulleys as a novel factor in tenosynovitis and dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:922–925. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrar DB, Schleich C, Nebelung S, Frenken M, Radke KL, Vordenbäumen S, et al. High-resolution MRI of flexor tendon pulleys using a 16-channel hand coil: disease detection and differentiation of psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:40. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-2135-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dakkak YJ, van Dijk BT, Jansen FP, Wisse LJ, Reijnierse M, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, et al. Evidence for the presence of synovial sheaths surrounding the extensor tendons at the metacarpophalangeal joints: a microscopy study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24:154. doi: 10.1186/s13075-022-02841-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthijssen XME, Wouters F, Boeters DM, Boer AC, Dakkak YJ, Niemantsverdriet E, et al. A search to the target tissue in which RA-specific inflammation starts: a detailed MRI study to improve identification of RA-specific features in the phase of clinically suspect arthralgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:249. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-2002-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutierrez M, Filippucci E, Salaffi F, Di Geso L, Grassi W. Differential diagnosis between rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: the value of ultrasound findings at metacarpophalangeal joints level. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1111–1114. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.147272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mankia K, D’Agostino MA, Rowbotham E, Hensor EM, Hunt L, Möller I, et al. MRI inflammation of the hand interosseous tendons occurs in anti-CCP-positive at-risk individuals and may precede the development of clinical synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:781–786. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowbotham EL, Freeston JE, Emery P, Grainger AJ. The prevalence of tenosynovitis of the interosseous tendons of the hand in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McQueen FM. Bone marrow edema and osteitis in rheumatoid arthritis: the imaging perspective. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:224. doi: 10.1186/ar4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poulsen AEF, Axelsen MB, Poggenborg RP, Eshed I, Krabbe S, Glinatsi D, et al. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging in psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and healthy controls: interscan, intrareader, and interreader agreement and distribution of lesions. J Rheumatol. 2021;48:198–206. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoellnast H, Deutschmann HA, Hermann J, Schaffler GJ, Reittner P, Kammerhuber F, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: findings in contrast-enhanced MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:351–357. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan AL, Benjamin M, Toumi H, Grainger AJ, Tanner SF, Emery P, et al. The relationship between the extensor tendon enthesis and the nail in distal interphalangeal joint disease in psoriatic arthritis--a high-resolution MRI and histological study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:253–256. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen H, Barnthouse NC, Chan BY. Periosteal pathologic conditions: imaging findings and pathophysiology. Radiographics. 2023;43:e220120. doi: 10.1148/rg.220120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sankowski AJ, Lebkowska UM, Cwikła J, Walecka I, Walecki J. Psoriatic arthritis. Pol J Radiol. 2013;78:7–17. doi: 10.12659/PJR.883763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGonagle D. Enthesitis: an autoinflammatory lesion linking nail and joint involvement in psoriatic disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 1):9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asahina A, Fukuda T, Ishiuji Y, Yaginuma A, Yanaba K, Umezawa Y, et al. Usefulness of dual-energy computed tomography for the evaluation of early-stage psoriatic arthritis only accompanied by nail psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2017;44:e326–e327. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaeley GS, Eder L, Aydin SZ, Gutierrez M, Bakewell C. Dactylitis: a hallmark of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;48:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan AL, Fukuba E, Halliday NA, Tanner SF, Emery P, McGonagle D. High-resolution MRI assessment of dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis shows flexor tendon pulley and sheath-related enthesitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:185–189. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]