Abstract

PURPOSE

Integrating palliative care into oncology is essential, yet disparities in access and quality persist, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The ASCO guidelines advocate for early, routine, interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. Barriers to implementing these recommendations include resource limitations, inadequate training, and cultural perceptions. Recognizing these challenges is essential for improving equitable access to palliative care worldwide.

METHODS

This prospective survey assessed adherence to ASCO recommendations for palliative care integration among LMIC health care providers (HCPs). Participants were recruited via e-mail, social media, and a list of members involved in the ASCO Palliative Care Communities of Practice from February to May 2024. The survey included sections on sociodemographic information, self-perceived adherence to ASCO guidelines on a 5-point Likert scale, and open-ended questions on implementation barriers. Data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture system. Participants were grouped by WHO regions. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics and adherence scores, and chi-square tests were used to evaluate regional differences. Thematic analysis identified key themes from open-ended responses.

RESULTS

One hundred eighty HCPs participated; 62% was female, and 51.1% was age 35-44 years. Most were physicians (66%), and 50% lacked palliative care specialization. Adherence to ASCO guidelines varied, with early palliative care referrals ranging from 50% in the Americas region to 0% in the Western Pacific region. Key barriers included lack of policy support (25%), unmet educational needs (22%), and accessibility constraints (19%).

CONCLUSION

Addressing identified barriers through evidence-based advocacy, comprehensive policy changes, training, and continuing education programs is essential for integrating palliative care into oncology services across LMICs, promoting health equity for patients with cancer.

BACKGROUND

As of 2021, more than 16.6 people worldwide had serious health-related suffering due to cancer that was amenable to palliative care and about 60% lived in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) where access to palliative care services and essential medicines are limited.1 Although integrating palliative care into health systems is a fundamental component of comprehensive health coverage,2 access and quality vary significantly across regions and progress toward achieving universal palliative care access has been insufficient.3-11 A 2017 survey on the global status of palliative care revealed that only 30 of 198 countries achieved advanced integration of palliative care into their health care systems.12 Most of those countries were located in Europe and represented only 14% of the world's population, with very few LMICs reaching the highest level of integration.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To evaluate the adherence of health care providers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to the ASCO guidelines for palliative care integration and identify barriers hindering implementation.

Knowledge Generated

The study highlights substantial regional variability in adherence to ASCO guidelines, with early referrals to palliative care ranging from 50% in the Americas region to 0% in the Western Pacific region. Key barriers include insufficient policy support, unmet educational needs, and accessibility constraints. These findings provide actionable insights into the systemic and resource-based challenges limiting palliative care integration in LMICs.

Relevance

The study underscores the need for targeted interventions, including policy reform, enhanced training programs, and capacity building, to bridge gaps in palliative care access and promote equity for patients with advanced cancer in resource-constrained settings.

Recognizing the need for clinical guidance to achieve the full integration of palliative care, the ASCO guidelines advocate for early palliative care as part of standard oncology treatment for patients with advanced cancer.13,14 ASCO's recommendations emphasize an interdisciplinary approach, including attention to physical, emotional, and social care.13 Furthermore, ASCO's resource-stratified guidelines for palliative care strongly emphasize health equity and highlight the need to consider linguistic, geographic, ethical, and contextual factors affecting equitable palliative care delivery, particularly in LMICs.15,16

Multipronged strategies involving education, feedback on guideline adherence, and clinical reminders may facilitate guideline implementation and improve outcomes for patients with cancer.17 However, the resources needed to translate guidelines into practice vary by world region. In high-income regions like North America and Western Europe, well-established palliative care networks facilitate the early integration of palliative care.18-20 By contrast, in less developed regions, palliative care remains under-resourced because of limited funding, insufficient training programs, and regulatory barriers that impede accessibility to opioids and other palliative medicines, which are essential for effective pain and symptom management.1,17-19

Recognizing and addressing region-specific challenges can improve guideline adherence and early palliative care provision by informing targeted strategies to address gaps in care delivery. To address this need, the ASCO Palliative Care Community of Practice developed a study to survey health care providers (HCPs) in LMICs about their adherence to ASCO guideline recommendations and the barriers they face while implementing palliative care in their settings.12,21

METHODS

This is a prospective, cross-sectional study conducted using an online survey to gather data on HCPs' adherence to palliative care guidelines and perceptions of barriers within LMICs. For this report, we used the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS; Appendix Table A1).

Survey Instrument

The survey consisted of 28 questions within three main sections (Appendix 1):

Sociodemographic and Professional Information (8): The first section included questions covering participants' age, sex, level of education, specialization in palliative care, ASCO membership, country of work, type of health care facility, and years of experience in oncology care.

Adherence to ASCO Recommendations (18): Participants were asked to rate their adherence to each of ASCO's palliative care guidelines for patients with advanced cancer on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “not adhered to at all” and 5 indicated “fully adhered to.”

Barriers and Additional Insights (2): Open-ended questions invited participants to describe perceived barriers and challenges to implementing ASCO's palliative care recommendations. In addition, participants could provide comments, insights, or suggestions regarding the integration of palliative care into oncology within their facility.

To ensure clarity and relevance, the survey instrument was reviewed and pretested with a small sample of five HCPs with similar demographics to the target population. No major modifications were needed after pretesting. The full survey is available as Appendix 1 for reference.

Sample Characteristics

The study population included HCPs working in oncology within LMICs. Eligible participants were required to be involved in patient care, specifically in treating patients with cancer, and demonstrate sufficient proficiency in English as the survey was only available in that language. Exclusion criteria included HCPs with limited English proficiency, those not directly involved in patient care (eg, administrative or nonclinical research roles), those who did not treat patients with cancer, and those with substantial incomplete survey responses, defined as individuals who left more than 50% of the questions unanswered. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling, with invitation distributed via multiple channels: personalized e-mail, social media platforms (X/Twitter), and in the ASCO Palliative Care Community of Practice.21 Participation was voluntary, and no restrictions were imposed based on specific LMIC locations.

Survey Administration

The survey was administered online through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system, a secure, web-based application for data collection. It was available from February 2024 to May 2024. We ensured that reminders were sent alongside the link to encourage participation and engagement. To prevent duplicate participation, IP-based restrictions and unique log-in identifiers were used.

Study Preparation

Before launching the survey, informational content was disseminated through social media platforms, specifically via the X/Twitter account, to increase awareness among eligible HCPs in LMICs. This content was shared weekly to keep the study visible and foster engagement within the targeted community. Each post included a brief reminder of the study's main goal and eligibility criteria for HCPs in LMICs.

Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at Santa Marta Hospital in Brazil, with participants providing electronic assent before participation. To maintain anonymity, all responses were kept confidential and access to data was restricted to authorized personnel only. REDCap's encryption features and user authentication procedures ensured secure data handling.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by grouping participants according to their WHO region (African [AFRO], Eastern Mediterranean [EMRO], European [EURO], Region of the Americas [AMRO], South-East Asia [SEARO], and Western Pacific [WPRO]).22 Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations) were calculated for sociodemographic characteristics and adherence scores to provide an overview of the sample by WHO region. To assess differences in adherence to ASCO recommendations13 across WHO regions, we used chi-square tests for categorical variables. Responses to open-ended questions about barriers and challenges were qualitatively analyzed using thematic analysis.23,24 Two independent reviewers read and coded the responses to ensure reliability, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Key themes were identified to capture common barriers and region-specific insights into palliative care integration. Representative quotes have also been included to support the thematic findings. All quantitative analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 29.0, with the significance level set at P < .05.

Handling Missing Data

Missing data were managed through listwise deletion for quantitative responses, ensuring completeness in descriptive analyses. The rate of missing items was minimal (<5%), assumed to be missing completely at random, and no imputation methods were applied because of the low rate.

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

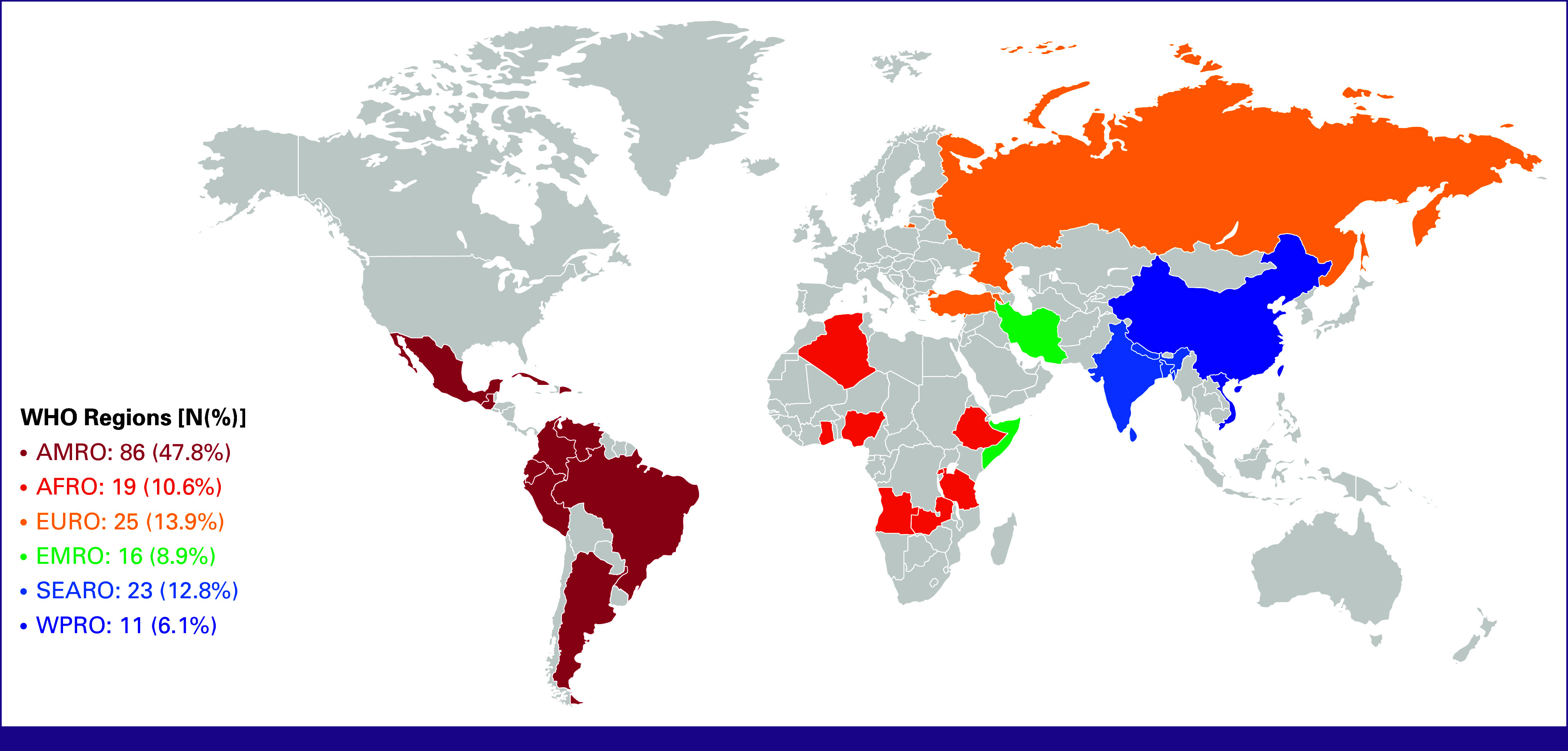

A total of 180 HCPs from LMICs participated in this survey, yielding a 72% response rate from the 250 contacted. Attrition was due to incomplete surveys (15%) and nonconsent (13%). Most respondents were female (62.2%) and between 35 and 44 years of age (51.1%). Physicians comprised the majority (66.6%), with 50.0% reporting no specialization in palliative care and 41.7% having such training. In addition, 56.1% was ASCO members. Geographically, participants were from the AMRO region (47.8%), followed by EURO (13.9%), SEARO (12.8%), AFRO (10.6%), EMRO (8.9%), and WPRO (6.1%; Fig 1). Most HCPs worked in a hospital/cancer center (66.6%) and had 1-5 years (46.7%) or 6-10 years (21.7%) of experience (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Geographic distribution of participants by WHO regions. AFRO, African; AMRO, Region of the Americas; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; EURO, European; SEARO, South-East Asia; WPRO, Western Pacific.

TABLE 1.

Participants' Characteristics by WHO Regions (N = 180)

| Characteristic | AFRO (n = 19) | AMRO (n = 86) | EMRO (n = 16) | EURO (n = 25) | SEARO (n = 23) | WPRO (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 7 (36.8) | 21 (24.4) | 13 (81.2) | 11 (44.0) | 14 (60.9) | 2 (18.2) |

| Female | 12 (63.2) | 65 (75.6) | 3 (18.8) | 14 (56.0) | 9 (39.1) | 9 (81.8) |

| Age, years, No. (%) | ||||||

| Under 25 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 25-34 | 2 (10.5) | 18 (20.9) | 7 (43.7) | 8 (32.0) | 6 (26.1) | 5 (45.4) |

| 35-44 | 10 (52.6) | 41 (47.7) | 6 (37.5) | 15 (60.0) | 14 (60.9) | 6 (54.6) |

| 45-54 | 5 (26.4) | 16 (18.6) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 55-64 | 2 (10.5) | 6 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 65 or older | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||||

| Physician | 13 (68.4) | 51 (59.3) | 13 (81.2) | 18 (72.0) | 17 (73.9) | 8 (72.7) |

| Nurse | 3 (15.8) | 18 (20.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (16.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Psychologist | 2 (10.5) | 12 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Othera | 1 (5.3) | 5 (5.8) | 3 (18.8) | 1 (4.0) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (18.2) |

| Specialization in palliative care, No. (%) | ||||||

| No | 12 (63.2) | 35 (40.7) | 7 (43.7) | 18 (72.0) | 10 (43.5) | 8 (72.7) |

| Yes | 4 (21.0) | 46 (53.5) | 9 (56.3) | 5 (20.0) | 10 (43.5) | 1 (9.1) |

| In progress | 3 (15.8) | 5 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Health care facility, No. (%) | ||||||

| Hospital and cancer centers | 12 (63.2) | 55 (63.9) | 9 (56.3) | 20 (80.0) | 14 (60.9) | 10 (90.9) |

| Outpatient clinics | 2 (10.5) | 22 (25.6) | 7 (43.7) | 5 (20.0) | 4 (17.4) | 1 (9.1) |

| Palliative care centers | 2 (10.5) | 4 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 3 (15.8) | 5 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Years in oncology, No. (%) | ||||||

| <1 | 2 (10.5) | 12 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (24.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1-5 | 10 (52.6) | 34 (39.6) | 10 (62.5) | 10 (40.0) | 10 (43.5) | 10 (90.9) |

| 6-10 | 5 (26.4) | 18 (20.9) | 6 (37.5) | 2 (8.0) | 7 (30.4) | 1 (9.1) |

| 11-20 | 2 (10.5) | 16 (18.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (16.0) | 6 (26.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| >20 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ASCO membership, No. (%) | ||||||

| No | 5 (26.4) | 56 (65.1) | 3 (18.8) | 7 (28.0) | 3 (13.0) | 5 (45.4) |

| Yes | 14 (73.6) | 30 (34.9) | 13 (81.2) | 18 (72.0) | 20 (87.0) | 6 (54.6) |

Abbreviations: AFRO, African; AMRO, Region of the Americas; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; EURO, European; SEARO, South-East Asia; WPRO, Western Pacific.

Other: physiotherapist, dietitians, dentist, genetic counselor, speech therapist.

Adherence to ASCO Palliative Care Recommendations

Adherence to ASCO palliative care guidelines13 varied significantly by region (Table 2). Early referral to interdisciplinary specialty palliative care teams within 8 weeks of diagnosis was reported by 50.8% in AMRO and 66.7% in EMRO, compared with none in WPRO. Outpatient interdisciplinary specialty palliative care adherence ranged from 33.3% in AFRO and SEARO to 100.0% in EMRO (P = .039).

TABLE 2.

Adherence to ASCO Palliative Care Guidelines1 by WHO Regions

| Recommendation | AFRO, % | AMRO, % | EMRO, % | EURO, % | SEARO, % | WPRO, % | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Referral to interdisciplinary palliative care teams within 8 weeks of diagnosis | 16.7 | 50.8 | 66.7 | 12.5 | 41.7 | 0.0 | .072 |

| 2.1. Delivery of palliative care through interdisciplinary teams with consultation in the outpatient setting | 33.3 | 62.1 | 100.0 | 22.2 | 33.3 | 50.0 | .039 |

| 2.2. Delivery of palliative care through interdisciplinary teams with consultation in the inpatient setting | 50.0 | 59.3 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 41.7 | 100.0 | .425 |

| 3.1. Essential components of palliative care include rapport and relationship building with patients and family caregivers | 50.0 | 82.0 | 100.0 | 62.5 | 54.5 | 100.0 | .090 |

| 3.2. Essential components of palliative care include symptom, distress, and functional status management | 50.0 | 84.0 | 100.0 | 75.0 | 70.0 | 100.0 | .162 |

| 3.3. Essential components of palliative care include exploration of understanding and education about illness and prognosis | 41.7 | 80.9 | 100.0 | 50.0 | 80.0 | 100.0 | .039 |

| 3.4. Essential components of palliative care include clarification of treatment goals | 58.3 | 80.9 | 66.7 | 62.5 | 66.7 | 100.0 | .511 |

| 3.5. Essential components of palliative care include assessment and support of coping needs | 33.3 | 66.7 | 50.0 | 37.5 | 60.0 | 100.0 | .200 |

| 3.6. Essential components of palliative care include assistance with medical decision making | 41.7 | 78.7 | 66.7 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | .025 |

| 3.7. Essential components of palliative care include coordination with other care providers | 41.7 | 83.0 | 100.0 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 100.0 | . 083 |

| 4.1. In addition to outpatient palliative care, patients have access to nurse navigation | 18.2 | 60.5 | 66.7 | 25.0 | 44.4 | 50.0 | .120 |

| 4.2. In addition to outpatient palliative care, patients have access to social work | 18.2 | 60.5 | 33.3 | 25.0 | 33.3 | 50.0 | .099 |

| 4.3. In addition to outpatient palliative care, patients have access to mental health professionals | 18.2 | 60.5 | 66.7 | 37.5 | 55.6 | 50.0 | .204 |

| 4.4. In addition to outpatient palliative care, patients have access to pastoral care (clergy, chaplains, spiritual care) | 36.4 | 53.5 | 66.7 | 25.0 | 33.3 | 50.0 | .562 |

| 4.5. In addition to outpatient palliative care, patients have access to integrative oncology | 18.2 | 44.20 | 66.7 | 37.5 | 33.3 | 50.0 | .599 |

| 5.1. Initiating caregiver-tailored palliative care support for family caregivers in outpatient setting | 55.6 | 58.1 | 66.7 | 28.6 | 50.0 | 50.0 | .796 |

| 5.2. Initiating caregiver-tailored palliative care support for family caregivers in home setting | 44.4 | 51.2 | 33.3 | 28.6 | 50.0 | 50.0 | .910 |

| 5.3. Initiating caregiver-tailored palliative care support for family caregivers in community setting | 10.0 | 34.9 | 33.3 | 28.6 | 50.0 | 50.0 | .610 |

Abbreviations: AFRO, African; AMRO, Region of the Americas; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; EURO, European; SEARO, South-East Asia; WPRO, Western Pacific.

Core palliative care elements, including symptom and distress management, showed regional differences. For example, adherence to managing symptoms, distress, and functional status was 84.0% in AMRO and 100.0% in WPRO and EMRO (P = .039). Similarly, medical decision-making support was high in WPRO (100.0%) and AMRO (78.7%), but lower elsewhere (P = .025). Access to support services was highest in AMRO and EMRO (up to 66.7%), but limited in other regions. Caregiver support for family members also varied, with 58.1% in AMRO offering caregiver support compared with 10.0% in AFRO.

Barriers and Additional Insights

Thematic analysis revealed five main themes on barriers and insights that affect palliative care delivery in LMICs (Table 3):

Policy and institutional support (25.0%): Respondents cited insufficient policies, limited funding, and lack of institutional support as major barriers.

Education and training (22.2%): A need for continuous education emerged as critical to improving care delivery.

Accessibility and resource constraints (19.4%): Barriers included a shortage of specialized palliative care staff, limited home care services, and barriers for rural patients.

Community awareness and cultural sensitivity (16.7%): Stigma and cultural barriers persist, with respondents noting misconceptions associating palliative care with end-of-life care.

Multidisciplinary collaboration (15.5%): The lack of coordinated team approaches and delays in referrals were noted as challenges.

TABLE 3.

Barriers and Additional Insight Responses

| Category | Description | Prevalence, % | Key Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy and institutional support | Need for comprehensive national policies, increased funding, institutional support for integrated services | 25.0 | “Brazilian public policies prevent all patients from having access to care, compared to private care” “Limited funding opportunities allocated to palliative care health workers” |

| Education and training | Ongoing palliative care training for health care teams to address misconceptions and improve oncology care | 22.2 | “We need more education at oncology specialization about the importance of palliative care” “Our greatest difficulty delivering palliative care to our patients and families is the lack of understanding of the goals of palliative care from physicians” |

| Accessibility and resource constraints | Limited access because of insufficient staff, financial barriers, rural patient challenges | 19.4 | “We don't have all the multidisciplinary team available to help our patients and their families” “Patients come from rural areas where there is a lack of transportation, which makes home setting care difficult” “There are not enough nurses or palliative care specialists” |

| Community awareness and cultural sensitivity | Initiatives to demystify palliative care, addressing cultural taboos related to death | 16.7 | “The perception from patients and families that palliative care is hospice and the continued subconscious translation of palliative care with giving up” “Cultural challenges, especially death as a taboo” “Spiritual needs of Muslim patients in Ghana as well as other religious groups have a huge gap” |

| Multidisciplinary collaboration | Integration of palliative care specialists and interdisciplinary teams in oncology settings | 15.5 | “We have organizational barriers, lack of specific staff for integrative care (nurses, psychologists, nutritionists, etc)” “The system from my country is slow to refer patients in palliative condition” |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed HCPs' self-reported adherence to ASCO palliative care guidelines in LMIC oncology settings. Our findings highlight both progress and ongoing challenges in integrating palliative care within oncology across various regions, emphasizing regional discrepancies in the implementation of ASCO's palliative care recommendations from 2017.13 The survey results reflect a partial adherence to ASCO's guidelines across different WHO regions, highlighting critical gaps, particularly in the AFRO, SEARO, and WPRO. Adherence to the recommendation for early referral to interdisciplinary specialty palliative care teams, for instance, varied widely, with notable compliance in the AMRO and EMRO, but was considerably lower in other regions, especially the WPRO, where no respondents reported adherence. These findings underscore the remaining barriers to expanding timely and equitable palliative care access, including the shortage of specialized palliative care professionals and the limited integration of palliative care in primary oncology services, as previously observed in LMICs.

In alignment with the ASCO 2024 recommendations to address health inequities, this study reveals that access to essential palliative care services, such as symptom management, psychosocial support, and caregiver support, remains inconsistent across WHO regions.15,16 While providers in the AMRO and EMRO regions reported relatively high adherence to offering these services, other regions, particularly AFRO, face significant challenges in delivering comprehensive palliative care. For instance, about 20% of the worldwide need for palliative care for adults and 52% of palliative care needs for children are in the AFRO region.9 Only 10% of African providers indicated having access to community-based caregiver support, reflecting a gap in support services crucial for the holistic care model promoted by ASCO.13,15 This finding aligns with previous studies reporting similar shortages in palliative care services in resource-constrained settings, where palliative care delivery is often limited by structural and financial constraints.20,25,26

Geographic inequities and systemic barriers pose significant challenges to delivering comprehensive palliative care in LMICs. Services are often concentrated in urban centers, leaving rural and remote populations underserved because of limited infrastructure and transportation.27 Systemic issues, including inadequate HCP training, restrictive opioid regulations, and the lack of national policies integrating palliative care, further hinder progress.28-30 Initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa, such as expanding opioid availability and improving provider training, represent steps forward.28,31 However, addressing these barriers requires coordinated strategies that focus on policy reform, workforce development, and equitable resource allocation,55,56 aligning with ASCO's vision for accessible, high-quality care.

Furthermore, the 2024 guidelines' emphasis on linguistic, geographic, and contextual considerations is especially relevant for LMICs, where diverse cultural and health care infrastructures affect the implementation of palliative care.15 Our results indicate that adherence to ASCO recommendations is often hindered by contextual factors, such as the perception of palliative care as culturally taboo, which can exacerbate disparities in palliative care delivery. For example, recommendations on integrating palliative care in outpatient settings were met with higher adherence in the AMRO and EMRO compared with the AFRO and SEARO, where health care infrastructure and training may be less supportive of comprehensive palliative care.20,25,26,32-35 Cultural perceptions around palliative care as synonymous with end-of-life or hospice care, as well as limited education and workforce training, further hinder adoption in many LMIC regions.32,33 For example, in SEARO and WPRO, large populations and a high burden of noncommunicable diseases increase the demand for palliative care, yet services remain insufficiently integrated into existing health care systems.20 Previous studies highlight the high unmet need for palliative care in Southeast Asia, where national health systems are overwhelmed by the increasing demand but are constrained by limited funding and infrastructure.28,36-38

Literature has shown that in LMICs, quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes in palliative care settings are influenced by factors such as community-based social support, indigenous complementary medicine use, and unmet mental health needs, underscoring the importance of palliative care models that are culturally and regionally adapted.34,35 Indeed, LMICs have unique strengths and needs, with some demonstrating successful palliative care initiatives that could serve as models.40,41,53,54 For instance, community-based programs in Bangladesh, within the SEARO region, have shown improved patient QOL and reduced symptom burdens, highlighting the potential impact of locally adapted palliative care programs.42 The literature from regions such as Latin America and Southeast Asia offers examples of initiatives that have effectively integrated palliative care into community-based models, fostering a more sustainable approach to care that could be replicated in other regions.37-39,53,54

Our findings highlight the need for adaptable, resource-sensitive implementation and evaluation strategies for palliative care recommendations in LMICs.43-45 Addressing workforce shortages, enhancing provider training, and promoting culturally sensitive palliative care models could help bridge regional gaps. Ensuring that all team members are working to the full extent of their licensure and scope of practice will help to optimize palliative care assessment and service delivery across settings.46-52 In addition, investment in supportive services, such as social work and mental health, is essential to support patients and caregivers. Strengthening these areas in palliative oncology care could enable broader alignment with ASCO's recommendations, ultimately fostering more equitable, high-quality palliative care worldwide.

Our study has some limitations. First, the survey relied on self-reported data, which may introduce response bias, as providers may overestimate their adherence to ASCO guidelines. Furthermore, the survey did not directly assess awareness or familiarity with ASCO guidelines, which could influence adherence reporting. The use of convenience sampling introduces selection bias for those willing to take part in a voluntary survey study. Participants more engaged with professional networks or with greater access to digital platforms might have been over-represented, potentially excluding providers less connected to these resources. The sample size within individual WHO regions was relatively small, limiting region-specific conclusion. In addition, some LMICs may rely on national or regional guidelines tailored to local contexts, which could affect adherence to ASCO recommendations and were not accounted for in this survey. The study's sample, though inclusive of diverse WHO regions, may not fully represent all HCPs in LMICs as those with limited internet access, unable to speak English, or who are not ASCO members may be under-represented. Country-specific analyses developed by local investigators could help to shed additional light on unique needs across cultural and sociopolitical contexts, and we hope that our survey can be adapted and used in those settings. The cross-sectional nature of the survey also limits our ability to assess changes over time in adherence to palliative care recommendations. Moreover, cultural and regional variability in the interpretation and implementation of palliative care practices might have influenced responses, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Finally, data were not collected on specific barriers to guideline adherence within each region, limiting a detailed understanding of the structural challenges faced in LMICs.

Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights for improving palliative care delivery in LMICs. Findings suggest that focusing on building capacity through education, advocating for increased funding, and aligning international and local guidelines could enhance the feasibility and uptake of palliative care practices. Furthermore, collaboration between LMICs with existing national frameworks and those without could foster shared learning and adaptation of best practices. The results also highlight the critical role of structural and policy interventions in addressing barriers to guideline adherence. For example, the identification of gaps in provider training could inform the development of regional capacity-building programs and virtual learning platforms tailored to LMICs. In addition, targeted advocacy efforts, emphasizing the integration of palliative care as a core component of cancer care, could help mobilize resources and influence policy decisions in low-resource settings. Finally, while our discussion remains exploratory in some aspects, we hope that the findings spark a broader conversation on how international guidelines like ASCO's can be adapted and implemented in diverse health care systems. This study serves as a stepping stone for further research into context-specific interventions that bridge the gap between guideline recommendations and clinical practice in LMICs.

In conclusion, while progress has been made in some regions, the disparities identified in this study underscore the importance of regional adaptations of the ASCO guidelines and of the development of local and regional implementation strategies to meet the diverse needs of oncology patients in LMICs. The insights provided by our study may help the design of regional strategies to improve palliative care access and quality globally, ensuring that the principles outlined in the ASCO recommendations are translated into practice effectively and equitably.

APPENDIX 1. SURVEY ON ADHERENCE TO ASCO PALLIATIVE CARE RECOMMENDATIONS

Introduction

This survey is aimed at health care providers in low- and middle-income countries to understand the extent to which they adhere to the ASCO recommendations for integrating palliative care into standard oncology care. Your participation in this survey is invaluable in helping improve the quality of cancer care in your region. To make sure we are aligned, palliative care is a specialty focused on enhancing the quality of life of patient and their family.14

-

Section 1: Demographics

-

Gender

Male

Female

Other

Prefer not to say

-

Age

Under 25

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-64

65 or older

-

Education

Physician

Family physician

Nurse practitioner

Social worker

Palliative care consultant

Psychologist

Emergency medical service practitioner

Chaplain and spiritual counsellor

Dietitians

Occupational therapist

Pharmacist

Physiotherapist

Other (please, specify)

-

Specialization in Palliative Care

Yes

No

In Progress

-

ASCO membership

Yes

No

Location/Country (please specify)

-

-

Type of Healthcare Facility

Hospital

Clinic

Health center

Other (Specify)

-

Years in oncology care

Less than 1 year

1-5 years

6-10 years

11-20 years

More than 20 years

Section 2: ASCO Recommendations 1-2

Please indicate the extent to which your healthcare facility adheres to each of the ASCO recommendations regarding palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. Rate each recommendation on a scale of 1-5, where 1 indicates “Not Adhered to at All” and 5 indicates “Fully Adhered to.”

-

2.1. Recommendation 1

- Referral to interdisciplinary palliative care teams within eight weeks of diagnosis.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

2.2. Recommendation 2

- Delivery of palliative care through interdisciplinary teams with consultation in the outpatient setting.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

2.3. Recommendation 2

Delivery of palliative care through interdisciplinary teams with consultation in the inpatient setting.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

Section 3: ASCO Recommendation 3

Providing essential components of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. Essential components of palliative care include

-

3.1 rapport and relationship building with patients and family caregivers.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

3.2. symptom, distress, and functional status management (eg, pain, dyspnea, fatigue, sleep disturbance, mood, nausea, or constipation).

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

3.3. exploration of understanding and education about illness and prognosis.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

3.4. clarification of treatment goals

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

3.5. assessment and support of coping needs (eg, provision of dignity therapy)

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

3.6. assistance with medical decision making

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

3.7. coordination with other care providers

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

Section 4: ASCO Recommendation 4

In addition to outpatient palliative care, patients with high symptom burden and unmet needs have access to

-

4.1 nurse navigation.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

4.2. social work.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

4.3. mental health professionals.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

4.4. pastoral care (clergy, chaplains, spiritual care).

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

4.5. integrative oncology.

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

Section 5: ASCO Recommendation 5

Initiating caregiver-tailored palliative care support for family caregivers in

-

5.1 outpatient setting

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

5.2. home setting

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

-

5.3. community setting

Your Rating: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [Unsure]

Section 6: Barriers and Challenges

6.1. Are there any specific challenges or barriers at your healthcare facility that hinder the implementation of palliative care according to ASCO recommendations? (Please describe)

[Open-Text Response]

Section 7: Additional Comments

7.1. Please provide any additional comments, insights, or recommendations regarding the integration of palliative care into oncology care at your healthcare facility.

[Open-Text Response]

Thank you for participating in this survey. Your feedback is crucial in understanding the state of palliative care in oncology in low- and middle-income countries. Your input will help guide improvements in cancer care in your region.

TABLE A1.

Checklist for Reporting Of Survey Studies (CROSS)

| Section/Topic | Item | Item Description | Reported on Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | |||

| Title and abstract | 1a | State the word “survey” along with a commonly used term in title or abstract to introduce the study’s design | 1 |

| 1b | Provide an informative summary in the abstract, covering background, objectives, methods, findings/results, interpretation/discussion, and conclusions | 2 | |

| Introduction | |||

| Background | 2 | Provide a background about the rationale of study, what has been previously done, and why this survey is needed | 3-4 |

| Purpose/aim | 3 | Identify specific purposes, aims, goals, or objectives of the study | 4 |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Specify the study design in the methods section with a commonly used term (eg, cross-sectional or longitudinal) | 4 |

| 5a | Describe the questionnaire (eg, number of sections, number of questions, number and names of instruments used) | 4 | |

| 5b | Describe all questionnaire instruments that were used in the survey to measure particular concepts. Report target population, reported validity and reliability information, scoring/classification procedure, and reference links (if any) | 4 | |

| Data collection methods | 5c | Provide information on pretesting of the questionnaire, if performed (in the article or in an online supplement). Report the method of pretesting, number of times questionnaire was pre-tested, number and demographics of participants used for pretesting, and the level of similarity of demographics between pre-testing participants and sample population | 5 |

| 5d | Questionnaire, if possible, should be fully provided (in the article, or as appendices or as an online supplement) | Suppl | |

| 6a | Describe the study population (ie, background, locations, eligibility criteria for participant inclusion in survey, exclusion criteria) | 4 | |

| Sample characteristics | 6b | Describe the sampling techniques used (eg, single stage or multistage sampling, simple random sampling, stratified sampling, cluster sampling, convenience sampling). Specify the locations of sample participants whenever clustered sampling was applied | 5 |

| 6c | Provide information on sample size, along with details of sample size calculation | 5 | |

| 6d | Describe how representative the sample is of the study population (or target population if possible), particularly for population-based surveys | 5 | |

| 7a | Provide information on modes of questionnaire administration, including the type and number of contacts, the location where the survey was conducted (eg, outpatient room or by use of online tools, such as SurveyMonkey) | 5 | |

| Survey administration | 7b | Provide information of survey’s time frame, such as periods of recruitment, exposure, and follow-up days | 5 |

| 7c | Provide information on the entry process: For non-web-based surveys, provide approaches to minimize human error in data entry For web-based surveys, provide approaches to prevent “multiple participation” of participants |

5 | |

| Study preparation | 8 | Describe any preparation process before conducting the survey (eg, interviewers’ training process, advertising the survey) | 5 |

| Ethical considerations | 9a | Provide information on ethical approval for the survey if obtained, including informed consent, institutional review board [IRB] approval, Helsinki declaration, and good clinical practice [GCP] declaration (as appropriate) | 6 |

| 9b | Provide information about survey anonymity and confidentiality and describe what mechanisms were used to protect unauthorized access | 6 | |

| Statistical analysis | 10a | Describe statistical methods and analytical approach. Report the statistical software that was used for data analysis | 6 |

| 10b | Report any modification of variables used in the analysis, along with reference (if available) | 6 | |

| 10c | Report details about how missing data were handled. Include rate of missing items, missing data mechanism (ie, missing completely at random [MCAR], missing at random [MAR] or missing not at random [MNAR]), and methods used to deal with missing data (eg, multiple imputation) | 6 | |

| 10d | State how non-response error was addressed | 6 | |

| 10e | For longitudinal surveys, state how loss to follow-up was addressed | 6 | |

| 10f | Indicate whether any methods such as weighting of items or propensity scores have been used to adjust for non-representativeness of the sample | 6 | |

| 10g | Describe any sensitivity analysis conducted | 6 | |

| Results | |||

| Respondent characteristics | 11a | Report numbers of individuals at each stage of the study. Consider using a flow diagram, if possible | 7 |

| 11b | Provide reasons for non-participation at each stage, if possible | 7 | |

| 11c | Report response rate, present the definition of response rate or the formula used to calculate response rate | 7 | |

| 11d | Provide information to define how unique visitors are determined. Report number of unique visitors along with relevant proportions (eg, view proportion, participation proportion, completion proportion) | 7 | |

| Descriptive results | 12 | Provide characteristics of study participants, as well as information on potential confounders and assessed outcomes | 7 |

| Main findings | 13a | Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates along with 95% CIs and P values | |

| 13b | For multivariable analysis, provide information on the model building process, model fit statistics, and model assumptions (as appropriate) | ||

| 13c | Provide details about any sensitivity analysis performed. If there is a considerable amount of missing data, report sensitivity analyses comparing the results of complete cases with those of the imputed dataset (if possible) | ||

| Discussion | |||

| Limitations | 14 | Discuss the limitations of the study, considering sources of potential biases and imprecisions, such as non-representativeness of sample, study design, important uncontrolled confounders | 11 |

| Interpretations | 15 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results, based on potential biases and imprecisions, and suggest areas for future research | 10-12 |

| Generalizability | 16 | Discuss the external validity of the results | 10-12 |

| Other sections | |||

| Role of funding source | 17 | State whether any funding organization has had any roles in the survey’s design, implementation, and analysis | 1 |

| Conflict of interest | 18 | Declare any potential conflict of interest | 1 |

| Acknowledgements | 19 | Provide names of organizations/persons that are acknowledged along with their contribution to the research | 1 |

Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis

Honoraria: Amgen

Tingting Zhang

Employment: ONEiHEALTH

Leadership: ONEiHEALTH

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: ONEIHEALTH, HBM Holding

Darcy Burbage

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ipsen

Joseph McCollom

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/21629

Mazie Tsang

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AVEO, Poseida Therapeutics, Atara Biotherapeutics (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, AstraZeneca, Genentech

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: BioAscent

Other Relationship: National Institute on Aging (Inst)

William E. Rosa

Research Funding: Cambia Health Foundation (Inst), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Inst), Rita & Alex Hillman Foundation (Inst), Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (Inst), NCI/NIH comprehensive cancer center award P30CA008748

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties from books from Springer Publishing and Jones & Bartlett Learning

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis, Rushil Patel, Jafar Al-Mondhiry, Tingting Zhang, Nathasha Dhawan, Joseph McCollom, Mazie Tsang, Ramy Sedhom, William E. Rosa

Collection and assembly of data: Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Jafar Al-Mondhiry, Nathasha Dhawan, Mazie Tsang, William E. Rosa

Data analysis and interpretation: Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Chadane Thompson, Jafar Al-Mondhiry, Nathasha Dhawan, Darcy Burbage, Ramy Sedhom, William E. Rosa

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis

Honoraria: Amgen

Tingting Zhang

Employment: ONEiHEALTH

Leadership: ONEiHEALTH

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: ONEIHEALTH, HBM Holding

Darcy Burbage

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ipsen

Joseph McCollom

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/21629

Mazie Tsang

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AVEO, Poseida Therapeutics, Atara Biotherapeutics (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, AstraZeneca, Genentech

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: BioAscent

Other Relationship: National Institute on Aging (Inst)

William E. Rosa

Research Funding: Cambia Health Foundation (Inst), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Inst), Rita & Alex Hillman Foundation (Inst), Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (Inst), NCI/NIH comprehensive cancer center award P30CA008748

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties from books from Springer Publishing and Jones & Bartlett Learning

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knaul FM, Arreola-Ornelas H, Kwete XJ, et al. : The evolution of serious health-related suffering from 1990 to 2021: An update to The Lancet Commission on global access to palliative care and pain relief. Lancet Glob Health 13:e422-e436, 2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Assembly : Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment throughout the life course: Report by Secretariat, 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/158962 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.WHO : Declaration of Alma-Ata, 1978. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/39228/9241800011.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO , United Nations Children’s Fund. Declaration of Astana. 2018. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organization of American States : The Inter-American Convention on the Rights of Older Persons. https://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/inter_american_treaties_a-70_human_rights_older_persons.asp [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations : Political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage. Resolution 74/2, 2019. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n19/311/84/pdf/n1931184.pdf

- 7.Inter-Parliamentary Union. 2019. file:///Users/rosaw/Downloads/Resolution-UHC.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. : Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 19:e588-e653, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor S: Global Atlas of Palliative Care (ed 2). Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, 2020. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/csy/palliative-care/whpca_global_atlas_p5_digital_final.pdf?sfvrsn=1b54423a_3 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohman D, Cleary J, Connor S, et al. : Advancing global palliative care over two decades: Health system integration, access to essential medicines, and pediatrics. J Pain Symptom Manage 64:58-69, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding R, Hammerich A, Peeler A, et al. : Palliative care. How can we respond to 10 years of limited progress? WHO. https://wish.org.qa/research-report/palliative-care/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark D, Baur N, Clelland D, et al. : Mapping levels of palliative care development in 198 countries: The situation in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage 59:794-807.e4, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 30:880-887, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35:96-112, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders JJ, Temin S, Ghoshal A, et al. : Palliative care for patients with cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol 42:2336-2357, 2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosa WE, Garcia CA, Mardones MA, et al. : Integrating health equity in the ASCO guideline agenda: Recommendations from members of the palliative care expert panel. JCO Oncol Pract 20:1300-1303, 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomasone JR, Kauffeldt KD, Chaudhary R, et al. : Effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies on health care professionals’ behaviour and patient outcomes in the cancer care context: A systematic review. Implement Sci 15:41, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centeno C, Lynch T, Garralda E, et al. : Coverage and development of specialist palliative care services across the World Health Organization European Region (2005-2012): Results from a European Association for Palliative Care Task Force survey of 53 countries. Palliat Med 30:351-362, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centeno C, Clark D, Lynch T, et al. : Facts and indicators on palliative care development in 52 countries of the WHO European region: Results of an EAPC Task Force. Palliat Med 21:463-471, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor SR, Centeno C, Garralda E, et al. : Estimating the number of patients receiving specialized palliative care globally in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage 61:812-816, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsang M, Bergerot C, Dhawan N, et al. : Transformative peer connections: Early experiences from the ASCO palliative care community of practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 44:e100047, 2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Who-regions @ ourworldindata.org. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/who-regions

- 23.Glaser B, Strauss A.: Grounded theory: The discovery of grounded theory. Sociology 12:27-49, 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbin J, Strauss A: Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (ed 3). Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE Publications, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadhil I, Lyons G, Payne S: Barriers to, and opportunities for, palliative care development in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Lancet Oncol 18:e176-e184, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhee JY, Garralda E, Namisango E, et al. : An analysis of palliative care development in Africa: A ranking based on region-specific macroindicators. J Pain Symptom Manage 56:230-238, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aregay A, O'Connor M, Stow J, et al. : Strategies used to establish palliative care in rural low- and middle-income countries: An integrative review. Health Policy Plan 35:1110-1129, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannon B, Zimmermann C, Knaul FM, et al. : Provision of palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: Overcoming obstacles for effective treatment delivery. J Clin Oncol 34:62-68, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu A, Mittag-Leffler BN, Miller K: Palliative care in low- and medium-resource countries. Cancer J 19:410-413, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ddungu H: Palliative care: What approaches are suitable in developing countries? Br J Haematol 154:728-735, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Brien M, Mwangi-Powell F, Adewole IF, et al. : Improving access to analgesic drugs for patients with cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol 14:e176-e182, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke C, Doody O, Lloyd B: Healthcare practitioners' perspectives of providing palliative care to patients from culturally diverse backgrounds: A qualitative systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 22:182, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krakauer EL, Kwete XJ, Rassouli M, et al. : Palliative care need in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and human resource requirements for effective response. PLOS Glob Public Health 3:e0001980, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sallnow L, Smith R, Ahmedzai SH, et al. : Report of the Lancet Commission on the value of death: Bringing death back into life. Lancet 399:837-884, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gayatri D, Efremov L, Kantelhardt EJ, et al. : Quality of life of cancer patients at palliative care units in developing countries: Systematic review of the published literature. Qual Life Res 30:315-343, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozdemir S, Lee JJ, Yang GM, et al. : Awareness and utilization of palliative care among advanced cancer patients in Asia. J Pain Symptom Manage 64:e195-e201, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osman H, Shrestha S, Temin S, et al. : Palliative care in the global setting: ASCO resource-stratified practice guideline. J Glob Oncol 10.1200/JGO.18.00026 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Nguyen V, Khanh QT, Hocaoglu M, et al. : Integrated hospital- and home-based palliative care for cancer patients in Vietnam: People-centered outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage 66:175-182.e3, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Çeliker MY, Pagnarith Y, Akao K, et al. : Pediatric palliative care initiative in Cambodia. Front Public Health 5:185, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, et al. : The beginnings of children's palliative care in Africa: Evaluation of a children's palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med 12:1015-1021, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salins N, Bhatnagar S, Simha S, et al. : Palliative care in India: Past, present, and future. Indian J Surg Oncol 13:83-90, 2022. (suppl 1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chowdhury MK, Saikot S, Farheen N, et al. : Impact of community palliative care on quality of life among cancer patients in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20:6443, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO : Planning and implementing palliative care services: A guide for programme managers. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/planning-and-implementing-palliative-care-services-a-guide-for-programme-managers

- 44.WHO .: Assessing the development of palliative care worldwide: A set of actionable indicators. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033351

- 45.Tripodoro VA, Ray A, Garralda E, et al. : Implementing the WHO indicators for assessing palliative care development in three countries: A do-it-yourself approach. J Pain Symptom Manage 69:e61-e69, 2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosa WE, Parekh de Campos A, Abedini NC, et al. : Optimizing the global nursing workforce to ensure universal palliative care access and alleviate serious health-related suffering worldwide. J Pain Symptom Manage 63:e224-e236, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosa WE, Buck HG, Squires AP, et al. : International consensus-based policy recommendations to advance universal palliative care access from the American Academy of Nursing Expert Panels. Nurs Outlook 70:36-46, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell C, Ramakuela J, Dennis D, et al. : Palliative care practices in a rural community: Cultural context and the role of community health worker. J Health Care Poor Underserved 32:550-564, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woods AP, Monton O, Fuller SM, et al. : Implementation barriers and recommendations for a multisite community health worker intervention in palliative care for African American Oncology patients: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 27:1125-1134, 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jonas D, Patneaude A, Purol N, et al. : Defining core competencies and a call to action: Dissecting and embracing the crucial and multifaceted social work role in pediatric palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 63:e739-e748, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kearney G, Fischer L, Groninger H.: Integrating spiritual care into palliative consultation: A case study in expanded practice. J Relig Health 56:2308-2316, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Downing NJ, Skaczkowski G, Hughes-Barton D, et al. : A qualitative exploration of the role of a palliative care pharmacist providing home-based care in the rural setting, from the perspective of health care professionals. Aust J Rural Health 32:510-520, 2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peeler A, Afolabi O, Adcock M, et al. : Primary palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of the evidence for models and outcomes. Palliat Med 38:776-789, 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leng M, Downing J, Purewal G, et al. : Evaluation of the integration of palliative care in a fragile setting amongst host and refugee communities: Using consecutive rapid participatory appraisals. Palliat Med 38:818-829, 2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosa WE, Connor S, Aggarwal G, et al. : Relieve the suffering: Palliative care for the next decade. Lancet 10.1016/S0140-6736(25)00678-6 [epub ahead of print on April 18, 2025] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. : Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 391:2212, 2018. [Erratum: Lancet 391:1391-1454, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]