Abstract

Background

Calcineurin inhibitors, such as cyclosporine, are primary treatments for membranous nephropathy (MN). Optimizing this regimen is crucial to reduce nephrotoxicity and enhance immunological remission. Sirolimus, when combined with cyclosporine, may offer non-inferior clinical remission to cyclosporine monotherapy, while improving kidney function preservation and antibody clearance.

Methods

This single-center, randomized controlled, phase 2 clinical trial involved 74 patients with biopsy-proven primary MN and persistent proteinuria > 3.5 g/d, despite 6 months of supportive care. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either sirolimus plus cyclosporine or cyclosporine monotherapy for 12 months.

Results

At 12 months, composite remission was achieved in 26 of 36 patients (72%) receiving combination therapy and in 24 of 36 (67%) receiving cyclosporine alone (95% confidence interval for noninferiority: 0.48—3.56). Immunological remission, defined as anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody conversion from positive to negative, was significantly higher in the combination group (70% vs. 20%, P < 0.001) at 6 months. Moreover, eGFR decline was significantly attenuated in the combination group (ΔeGFR: -7.1 vs. -21.3 ml/min/1.73m2, P < 0.001) at 12 months. One serious adverse event occurred in the combination group, compared to none in the monotherapy group (P = 0.317).

Conclusions

Sirolimus combined with cyclosporine was noninferior to cyclosporine monotherapy in achieving clinical remission in MN and demonstrated superior benefits in immunological remission and kidney function preservation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04173-0.

Keywords: Cyclosporine, Sirolimus, Membranous Nephropathy, Clinical Trial, Anti-PLA2R Antibody

Clinical Perspectives

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is a leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults and can progress to end-stage kidney disease despite available therapies. One of the current standards of care, cyclosporin, benefits 60 to 70% of patients but is associated with substantial adverse effects such as kidney dysfunction. In this study, we introduce a novel therapeutic approach by combining sirolimus (rapamycin) with cyclosporine. This strategy aims to reduce nephrotoxicity while enhancing immunological remission and kidney function preservation. Our findings provide important evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of this combination regimen, offering a promising alternative for improving treatment outcomes in MN. These results may be particularly relevant in low-resource settings, where access to newer biologics remains limited, and cost-effective, well-tolerated therapies are urgently needed.

Background

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is the predominant cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. Approximately 70% of MN patients have circulating autoantibodies to the phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R), while other target antigens have been identified in the remaining patients over the past decade [1, 2]. Spontaneous remission occurs in about 30% of individuals; however, 40–50% of patients with persistent nephrotic syndrome progress to end-stage kidney disease within 10 years [3].

Initial management of MN typically involves supportive care, with immunosuppressive therapy reserved for patients at high risk factors of disease progression [4]. The traditional alternating regimen of glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide induces remission in 60–70% of patients but is associated with significant adverse effects, including hyperglycemia, myelosuppression, infections, infertility, and malignancy [5, 6]. Randomized controlled trials and cohort studies have demonstrated that rituximab and calcineurin inhibitors improve rates of complete and partial remission [7–12]. Owing to a more favorable safety profile, these agents are now preferred over cyclophosphamide in patients with preserved kidney function.

In developing countries, calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine remain the primary treatment for MN, largely due to drug availability and reimbursement constraints. However, their high relapse rate after discontinuation necessitates prolonged treatment, increasing the risk of adverse events such as nephrotoxicity, hypertension, hyperuricemia, and anemia. This underscores the urgent need for alternative or combination regimens that preserve efficacy while minimizing toxicity.

Sirolimus (rapamycin), widely used to prevent allograft rejection in organ transplantation [13], exerts immunosuppressive effects through inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)—a serine/threonine kinase critical for T-cell activation and proliferation [14]. In experimental rat models of MN, sirolimus has been shown to downregulate pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic gene expression, reduce tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis, and inhibit compensatory kidney hypertrophy [15]. Furthermore, sirolimus has been reported to reduce proteinuria and decrease glomerular IgG deposition, as evidenced by immunofluorescence studies [16]. Despite these promising findings, no clinical trials have evaluated sirolimus in patients with MN.

In this study, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine in patients with active MN.

Methods

Study Design

This investigator-initiated, prospective, open-label, randomized, non-inferiority clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of cyclosporine combined with sirolimus versus cyclosporine alone in patients with MN. The study was conducted at Peking University First Hospital. The trial protocol was designed by the principal investigators and approved by an independent ethics committee (approval number: 2017[1346]). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-INR-17012212). The complete protocol is provided in Supplement 1.

Patients

Eligible participants were adults aged 18–70 years with biopsy-confirmed primary MN and an observation period of at least 6 months prior to enrollment. Inclusion criteria were: estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 45 ml/min/1.73 m2, nephrotic-range proteinuria (> 3.5 g/day with < 50% reduction during the observation period), and hypoalbuminemia (≤ 35 g/L). Patients must have received at least 3 months of standard supportive therapy with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, with controlled blood pressure (< 140/90 mmHg), unless contraindicated due to intolerance or hypotension.

Exclusion criteria included: secondary MN (e.g., due to autoimmune diseases, infections, or malignancy), HIV infection, liver disease, corticosteroid use within 3 months prior to screening, immunosuppressive agents within 6 months, rituximab or other biological agents within 12 months, or a history of non-response to cyclosporine. Detailed criteria are listed in Supplement 2.

Interventions and Follow-up

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated sequence to receive either cyclosporine plus sirolimus (intervention group) or cyclosporine alone (control group).

In the control group, cyclosporine was initiated at 2 mg/kg/day, administered orally in two divided doses every 12 h. The target trough concentration was 100–150 ng/ml, with blood levels monitored biweekly until stabilization.

In the intervention group, patients received cyclosporine as described above, along with sirolimus initiated at 2 mg/day for the first 3 days, followed by a maintenance dose of 1 mg/day. The target trough concentration for sirolimus was 5–15 ng/ml, with blood levels monitored every two weeks until stable.

Treatment efficacy was evaluated based on reduction in proteinuria from baseline. If proteinuria was reduced by < 25% at 6 months, treatment was considered unsuccessful and discontinued. If a ≥ 25% reduction was achieved, treatment continued for an additional 6 months. A sustained, unexplained decline in eGFR > 50% from baseline or to < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 led to dose reduction. If eGFR failed to recover, cyclosporine was discontinued, and treatment was classified as a failure.

All participants were followed for 12 months, with scheduled visits at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and monthly thereafter through month 12.

Outcomes and Definitions

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving complete or partial remission at 12 months. Secondary endpoints included immunological remission at 6 months and sustained decline in eGFR > 50% from baseline despite cyclosporine dose adjustment. eGFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation.

Complete remission was defined as proteinuria ≤ 0.3 g/day, serum albumin > 35 g/L, and stable kidney function. Partial remission was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in proteinuria to < 3.5 g/day with stable kidney function. No response was defined as failure to achieve either complete or partial remission. Relapse was defined as an increase in proteinuria > 50% from the lowest achieved value and > 3.5 g/day in patients with prior remission.

Anti-PLA2R antibodies were measured using standardized commercial ELISA kits (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). Immunological remission was defined as a change from a positive to a negative anti-PLA2R antibody result.

Adverse Events and Safety

Safety outcomes included predefined serious adverse events, in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines for clinical safety data management. Monitored adverse events included: eGFR decline, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, gingival hyperplasia, respiratory infections, hypersensitivity reactions, gastrointestinal and dermatologic symptoms, neuromuscular complaints, cardiovascular events, leukopenia, and aplastic anemia.

Statistical Analyses

Based on prior studies, a sample size of 35 patients per group was calculated to provide 80% power to detect non-inferiority in the primary outcome, assuming a type I error of 0.05 and expected remission rates of 65% in the cyclosporine group and 85% in the combination group. Accounting for a 10% dropout rate, 74 patients were targeted for enrollment (37 per group).

All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and non-normally distributed variables as median with interquartile range. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages. Group comparisons were made using the independent-samples t-test for normally distributed data, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed data, and χ2 test for categorical variables. Missing primary outcome data were imputed using the last observation carried forward method. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 by statisticians blinded to treatment allocation.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 103 patients with biopsy-proven primary MN were screened, and 74 were enrolled and randomized equally into two groups: 37 patients received cyclosporine plus sirolimus, and 37 received cyclosporine monotherapy (Fig. 1). One patient in each group discontinued treatment; the remaining 72 patients completed the 12-month follow-up. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Table 1). The mean age of all participants was 49.1 ± 11.7 years, and 63.5% were male. The average urinary protein excretion was 7.2 ± 3.1 g/day, and the mean serum albumin level was 27.6 ± 5.6 g/L. The baseline eGFR was 94.2 ± 16.4 ml/min/1.73 m2. Anti-PLA2R antibodies were detected in 60.8% of patients, with an average level of 136.9 ± 96.4 RU/mL. Most patients (97.3%) had stage I–II MN. All enrolled participants were included in both efficacy and safety analyses.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the trial. Patients were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, to receive cyclosporin + sirolimus regimen or cyclosporin monotherapy regimen

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics of MN patients in comparisons of the cyclosporin + sirolimus group and the cyclosporin monotherapy group

| Baseline Characters | Total (n = 74) | Cyclosporin + Sirolimus (n = 37) | Cyclosporin monotherapy (n = 37) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49.1 ± 11.7 | 50.5 ± 9.7 | 47.7 ± 13.5 | 0.297 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 47 (63.5) | 22 (59.5) | 25(67.6) | 0.469 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 127.7 ± 14.5 | 125.0 ± 12.9 | 130.8 ± 15.6 | 0.095 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 75.8 ± 8.7 | 74.6 ± 6.7 | 77.6 ± 10.1 | 0.155 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 3.2 | 25.8 ± 3.1 | 25.5 ± 3.3 | 0.701 |

| History of immunosuppressants, n (%) | 8 (10.8) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (10.8) | > 0.999 |

| Anti-PLA2R positive rate, n (%) | 45 (60.8) | 20 (54.1) | 25 (67.6) | > 0.999 |

| Anti-PLA2R levels (U/ml) | 136.9 ± 96.4 | 125.7 ± 82.9 | 145.9 ± 88.6 | 0.569 |

| Urinary protein (g/d) | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 7.5 ± 4.7 | 7.2 ± 2.6 | 0.680 |

| Serum albumin (g/l) | 27.6 ± 5.6 | 28.0 ± 6.0 | 26.9 ± 5.4 | 0.433 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 76.2 ± 15.7 | 75.4 ± 16.0 | 76.9 ± 15.6 | 0.683 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 94.2 ± 16.4 | 91.8 ± 15.5 | 96.6 ± 17.2 | 0.208 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 3.8 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 2.1 | 0.416 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 140.0 ± 14.2 | 141.7 ± 12.4 | 138.0 ± 15.7 | 0.266 |

| MN stage (I/II/III/IV) | 34/38/2/0 | 15/22/0/0 | 19/16/2/0 | 0.333 |

Data are presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) for continuous measures, and n (%) for categoric measures. eGFR was calculated according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. Anti-PLA2R positivity defined by a value > 20 RU/ml

Clinical Remission

Rates of complete and partial remission were assessed at 3, 6, and 12 months (Table 2). The primary endpoint—the composite remission rate at 12 months—was 72.2% in the cyclosporine + sirolimus group and 66.7% in the cyclosporine monotherapy group, with no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Clinical remission of the MN patients by intention-to-treat analysis

| Cyclosporin + Sirolimus (n = 37) | Cyclosporin monotherapy (n = 37) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete remission (CR), n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 2/37 (5.4) | 1/37 (2.7) | 2.11 (0.18–23.72) |

| 6 months | 2/36 (5.6) | 2/36 (5.6) | 1.00 (0.13–7.51) |

| 12 months | 5/36 (13.9) | 5/36 (13.9) | 1.00 (0.26–3.80) |

| Partial remission (PR), n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 14/37 (37.8) | 17/37 (45.9) | 0.72 (0.28–1.81) |

| 6 months | 25/36 (69.4) | 24/36 (66.7) | 1.13 (0.42–3.06) |

| 12 months | 21/36 (58.3) | 19/36 (52.8) | 1.25 (0.49–3.18) |

| Composite remission (CR + PR), n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 16/37 (43.2) | 18/37 (48.6) | 0.80 (0.32–2.01) |

| 6 months | 27/36 (75.0) | 26/36 (72.2) | 1.15 (0.40–3.30) |

| 12 months | 26/36 (72.2) | 24/36 (66.7) | 1.30 (0.48–3.56) |

The intention-to-treat population included all the patients who underwent randomization and received treatments. The primary outcome was clinical remission (CR + PR) at 12 months

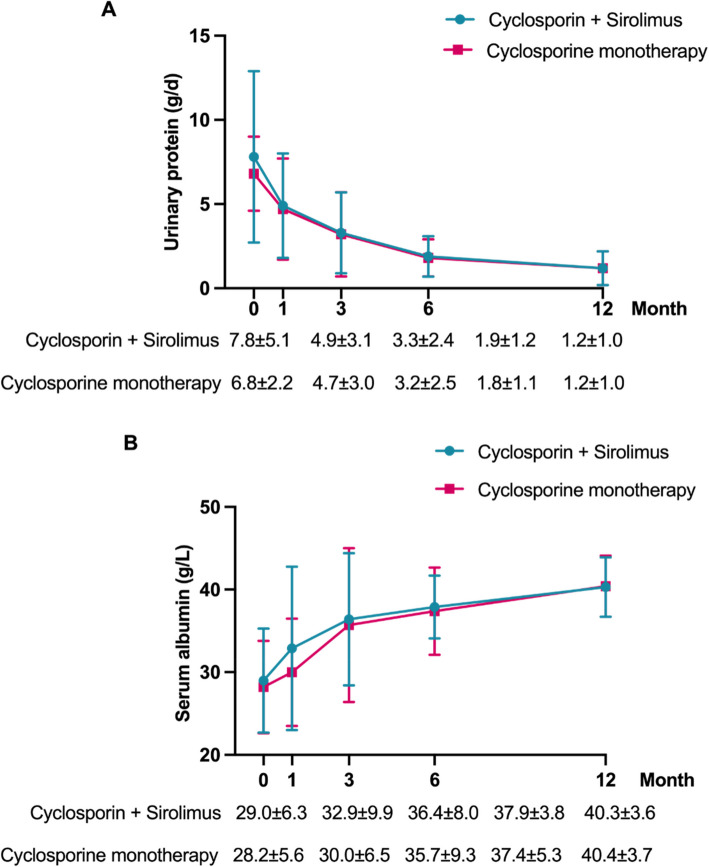

At 12 months (Table 2), complete remission was achieved in 13.9% and partial remission in 58.2% of patients in the combination group—comparable to the monotherapy group (P > 0.05). Among responders, proteinuria in the cyclosporine + sirolimus group decreased from 7.8 ± 5.1 g/day at baseline to 1.2 ± 1.0 g/day at 12 months, while serum albumin increased from 29.0 ± 6.3 to 40.3 ± 3.6 g/L. These improvements were similar in both groups (P > 0.05; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The urinary protein (A) and serum albumin (B) during the treatments of MN patients, with comparisons between the cyclosporin + sirolimus group and the cyclosporin monotherapy group

Immunology Remission

At baseline, 45 patients (60.8%) were positive for circulating anti-PLA2R antibodies: 20 in the combination group and 25 in the monotherapy group (P > 0.05; Table 1). Immunological remission occurred significantly more frequently in the cyclosporine + sirolimus group. At 3 months, 65.0% (13/20) of patients in the combination group achieved immunological remission compared to 12.0% (3/25) in the monotherapy group (P < 0.001). At 6 months, the remission rates were 70.0% (14/20) vs. 20.0% (5/25), respectively (P < 0.001). At 12 months, among patients who remained antibody-positive, 85.7% (12/14) of the combination group achieved remission vs. 40.0% (6/15) of the monotherapy group (P = 0.037; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunology remission rates of MN patients at 3, 6, and 12 months, with comparisons between the cyclosporin + sirolimus group and the cyclosporine monotherapy group. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001

Kidney Function

eGFR decline was more pronounced in the cyclosporine monotherapy group. At 6 months, the average decline (ΔeGFR) was −16.9 ± 13.9 ml/min/1.73 m2 (from 99.8 ± 15.4 to 83.0 ± 19.5), compared to −9.0 ± 13.1 ml/min/1.73 m2 (from 92.9 ± 16.9 to 83.9 ± 17.8) in the combination group (P = 0.039). At 12 months, the decline was −21.3 ± 16.0 ml/min/1.73 m2 (to 78.5 ± 22.6) in the monotherapy group vs. −7.1 ± 13.3 ml/min/1.73 m2 (to 85.8 ± 19.6) in the combination group (P < 0.001; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The eGFR (A) and the decline of eGFR (Δ eGFR, B) during the treatments of MN patients, with comparisons between the cyclosporin + sirolimus group and the cyclosporin monotherapy group. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001

Cyclosporin Trough Concentration

Cyclosporine trough concentrations were consistently lower in the cyclosporine + sirolimus group throughout the study (Fig. 5). Notably, the cyclosporin concentrations were consistently lower in the cyclosporin + sirolimus group compared to the cyclosporin monotherapy group, from the 1 st month through to the 12 th month. Significant differences were observed at 3 months (108.6 ± 49.3 vs. 145.8 ± 52.8 ng/ml, P = 0.011), at 6 months (114.8 ± 56.6 vs. 151.6 ± 45.1 ng/ml, P = 0.012), and at 12 months (96.7 ± 44.6 vs. 115.3 ± 36.0 ng/ml, P = 0.021).

Fig. 5.

The blood trough concentration of cyclosporin during the treatments of MN patients, with comparisons between the cyclosporin + sirolimus group and the cyclosporin monotherapy group. * P < 0.05

Adverse effects

One serious adverse event (severe diarrhea requiring hospitalization) occurred in the cyclosporine + sirolimus group (Table 3). This patient subsequently discontinued the study treatment. Common adverse events, including hyperlipidemia (Fig. 6) and anemia, were observed in both groups. eGFR reduction was more frequent in the monotherapy group (P = 0.012). Other events in the combination group included hypertension, hyperkalemia, elevated creatine kinase, abdominal pain, and new-onset diabetes.

Table 3.

Adverse Events and Complications

| Cyclosporin + Sirolimus (n = 37) | Cyclosporin monotherapy (n = 37) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse events | 1 (Diarrhea) | 0 | NS |

| Adverse events | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 27 | 24 | NS |

| Anemia | 13 | 13 | NS |

| eGFR reduction | 2 | 10 | 0.012 |

| Hyperkalemia | 2 | 5 | NS |

| Creatine kinase increase (asymptomatic) | 4 | 3 | NS |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 2 | NS |

| Diabetes | 2 | 1 | NS |

| Myalgia | 0 | 2 | NS |

| Headache | 0 | 2 | NS |

| Nausea or vomiting | 0 | 1 | NS |

| Gingival event | 0 | 1 | NS |

| Muscle cramps | 0 | 1 | NS |

| Complications of nephrotic syndrome | |||

| Edema | 21 | 25 | NS |

| Hypertension | 5 | 8 | NS |

| Thrombotic events | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Infections | 1 | 2 | NS |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 | 0 | NS |

Fig. 6.

The triglyceride (A), total cholesterol (B) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (C) during the treatments of MN patients, with comparisons between the cyclosporin + sirolimus group and the cyclosporine monotherapy group

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sirolimus in patients with primary MN. Over a 12-month treatment period, the combination of sirolimus and cyclosporin demonstrated noninferiority to cyclosporin monotherapy in achieving composite clinical remission of nephrotic syndrome. Notably, this combination regimen was associated with higher rates of immunological remission, defined by the clearance of anti-PLA2R antibodies, and afforded greater preservation of kidney function throughout the follow-up period.

Sirolimus is an immunosuppressive agent that inhibits antigen-induced T cell proliferation at the G1-S phase of the cell cycle and has been widely employed to prevent organ transplant rejection [13, 14, 17–20]. Moreover, sirolimus has shown beneficial effects in systemic lupus erythematosus by reversing proinflammatory T cell lineage differentiation after long-term treatment [21, 22]. In recent decades, primary MN has been firmly established as an autoimmune kidney disease involving both humoral and cellular immune responses [1–4, 23–25]. In our trial, a significantly higher rate of immunological remission was observed in the sirolimus + cyclosporin group compared to cyclosporin monotherapy, suggesting that sirolimus may exert its therapeutic effects in MN primarily through modulation of antigen-specific T and B cell activity.

Both treatment groups were effective in achieving high rates of proteinuria remission, comparable to those reported in previous cohort studies and randomized controlled trials involving cyclosporin [8–10]. However, a considerable decline in kidney function was observed in the cyclosporin monotherapy group, with a mean eGFR reduction of − 16.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 6 months and − 21.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 12 months. As KDIGO guidelines recommend extending calcineurin inhibitor therapy beyond one year due to the high relapse rate of nephrotic syndrome following discontinuation, strategies to mitigate calcineurin inhibitor-induced nephrotoxicity are urgently needed [4]. In this study, the addition of sirolimus significantly reduced the decline in eGFR to − 7.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 12 months, indicating a potential renoprotective effect, despite the decline still being statistically significant. These findings highlight the promise of combination therapy as a viable option for patients requiring prolonged calcineurin inhibitor treatment.

Several factors may account for the observed reduction in nephrotoxicity with sirolimus addition:

1. mTOR pathway inhibition: Chronic activation of the mTOR pathway has been linked to metabolic reprogramming in podocytes, promoting cellular stress and dedifferentiation [26]. Sirolimus inhibits this pathway, potentially reducing oxidative phosphorylation and anaerobic glycolysis, thereby alleviating podocyte injury. This mechanism enhances podocyte autophagy and contributes to proteinuria reduction. For instance, low-dose sirolimus has been shown to stabilize renal function and reduce glomerular proliferation in patients with poor prognosis IgA nephropathy when combined with enalapril and statins [27]. Combination therapy with sirolimus and tacrolimus has also demonstrated efficacy in refractory minimal change disease [28].

2. Comparative nephrotoxicity: Sirolimus is generally considered less nephrotoxic than cyclosporin or tacrolimus. In early animal studies, Ninova et al. [29] found that while toxic concentrations of sirolimus and tacrolimus both elevated serum creatinine in a transplant model, sirolimus caused less severe changes. Furthermore, sirolimus-treated rats exhibited reduced interstitial fibrosis with prolonged therapy. In clinical settings, Tumlin et al. [30] reported stabilization of renal function in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis patients treated with sirolimus, with only a 10% increase in serum creatinine among responders after 12 months, compared to a doubling in non-responders.

3. Efficacy of combination regimens: Combination therapy allows for dose reduction of individual agents, thereby reducing adverse events while maintaining efficacy. In our study protocol, if the target trough concentrations for both sirolimus and cyclosporine were not achieved, we prioritized adjusting the sirolimus dose first, followed by cyclosporine as needed. Additionally, once patients reached complete or partial remission, the treatment was maintained without further dose escalation. These factors likely contributed to the overall lower cyclosporine trough levels observed in the combination group, which may have helped mitigate cyclosporine-associated nephrotoxicity and contributed to the observed preservation of eGFR. Several small studies have demonstrated that low-dose cyclosporin remains effective and safer in MN patients [31, 32]. Importantly, clinical remission rates were similar between the two groups, suggesting that reduced eGFR was not attributable to treatment non-responders.

This trial has several limitations. It was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size and conducted exclusively in a homogenous population of Chinese patients, which may limit generalizability. Additionally, the treatment duration was relatively short, and there was no post-treatment follow-up period, making it difficult to assess the long-term renal protective effects and safety of sirolimus. These limitations underscore the need for future multicenter randomized controlled trials with larger and more diverse cohorts, longer follow-up durations, and head-to-head comparisons with other standard MN treatments, such as the increasingly widespread use of rituximab or other CD20-targeting therapies. Future studies should also evaluate sirolimus as a potential monotherapy, particularly its effects on antibody clearance. Although adverse events commonly associated with sirolimus in transplant recipients—such as impaired wound healing, increased proteinuria, and pneumonitis—were not observed in this study, these risks should be carefully considered in clinical practice.

Conclusions

The addition of sirolimus to cyclosporin therapy significantly and safely reduced proteinuria and anti-PLA2R antibody levels in patients with MN and was associated with improved preservation of kidney function. These findings support sirolimus as a promising treatment strategy for MN, warranting further investigation in larger, long-term studies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplement 1: Study protocol

Additional file 2. Supplement 2: Full inclusion and exclusion criteria

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- MN

Membranous nephropathy

- PLA2R

Phospholipase A2 receptor

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- RAASi

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors

Authors’ contributions

Research idea and study design: ZC and MHZ; data acquisition: FW, YY, and YL; data analysis/interpretation: FW, CY, YS, CXL, and ZC; statistical analysis: FW and CY; supervision or mentorship: YMZ, XW, LQM, XYC, GL, ZC, and MHZ. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Funding

This work was supported by National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (High Quality Clinical Research Project of Peking University First Hospital, 2023HQ07) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82325009).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial protocol was designed by the principal investigators and approved by an independent ethics committee (approval number: 2017[1346]). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-INR-17012212).

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form (including images, videos, or case details) that would require consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Beck LH Jr, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoxha E, Reinhard L, Stahl RAK. Membranous nephropathy: new pathogenic mechanisms and their clinical implications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18(7):466–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troyanov S, Wall CA, Miller JA, Scholey JW, Cattran DC. Idiopathic membranous nephropathy: definition and relevance of a partial remission. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerulonephritis Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2021; 100: S1–276.

- 5.Ponticelli C, Zucchelli P, Imbasciati E, et al. Controlled trial of methylprednisolone and chlorambucil in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:946–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Brand JA, van Dijk PR, Hofstra JM, et al. Cancer risk after cyclophosphamide treatment in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1066–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahan K, Debiec H, Plaisier E, et al. Rituximab for severe membranous nephropathy: a 6-month trial with extended follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:348–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fervenza FC, Appel GB, Barbour SJ, et al. Rituximab or cyclosporine in the treatment of membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattran DC, Greenwood C, Ritchie S, et al. A controlled trial of cyclosporine in patients with progressive membranous nephropathy. Canadian Glomerulonephritis Study Group Kidney Int. 1995;47:1130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cattran DC, Appel GB, Hebert LA, et al. Cyclosporine in patients with steroid resistant membranous nephropathy: a randomized trial. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1484–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Praga M, Barrio V, Juárez GF, Luño J. Tacrolimus monotherapy in membranous nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2007;71:924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramachandran R, Yadav AK, Kumar V, et al. Two-year follow-up study of membranous nephropathy treated with tacrolimus and corticosteroids versus cyclical corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:610–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasquez EM. Sirolimus: A new agent for prevention of renal allograft rejection. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:437–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bierer BE, Mattila PS, Standaert RF, et al. Two distinct signal transmission pathways in T lymphocytes are inhibited by complexes formed between an immunophilin and either FK506 or rapamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9231–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonegio RGB, Fuhro R, Wang ZY, et al. Rapamycin ameliorates proteinuria-associated tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis in experimental membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stratakis S, Stylianou K, Petrakis I, et al. Rapamycin ameliorates proteinuria and restores nephrin and podocin expression in experimental membranous nephropathy. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:941893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamdy AF, Elhadedy MA, Donia AF, et al. Outcome of sirolimus-based immunosuppression, fifteen years post-live-donor kidney transplantation: Single-center experience. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(2):e13463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber TB, Walz G, Kuehn EW. mTOR and rapamycin in the kidney: signaling and therapeutic implications beyond immunosuppression. Kidney Int. 2011;79:502–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fantus D, Rogers NM, Grahammer F, et al. Roles of mTOR complexes in the kidney: implications for renal disease and transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(10):587–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma MKM, Yung S, Chan TM. mTOR inhibition and kidney diseases. Transplantation. 2018;102:S32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai ZW, Kelly R, Winans T, et al. Sirolimus in patients with clinically active systemic lupus erythematosus resistant to, or intolerant of, conventional medications: a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1186–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yap DYH, Tang C, Chan GCW, et al. Longterm Data on Sirolimus Treatment in Patients with Lupus Nephritis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(12):1663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenzwajg M, Languille E, Debiec H, et al. B- and T-cell subpopulations in patients with severe idiopathic membranous nephropathy may predict an early response to rituximab. Kidney Int. 2017;92(1):227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramachandran R, Kaundal U, Girimaji N, et al. Regulatory B Cells Are Reduced and Correlate with Disease Activity in Primary Membranous Nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(6):872–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang XD, Lin CX, Cui Z, et al. Mapping the T cell epitopes of the M-type transmembrane phospholipase A2 receptor in primary membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):580–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zschiedrich S, Bork T, Liang W, et al. Targeting mTOR Signaling Can Prevent the Progression of FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(7):2144–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruzado JM, Poveda R, Iberno´n M, et al. Low-dose sirolimus combined with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and statin stabilizes renal function and reduces glomerular proliferation in poor prognosis IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011; 26: 3596–3602 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Patel P, Pal S, Ashley C, et al. Combination therapy with sirolimus (rapamycin) and tacrolimus (FK-506) in treatment of refractory minimal change nephropathy, a clinical case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(5):985–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ninova D, Covarrubias M, Rea DJ, Park WD, Grande JP, Stegall MD. Acute nephrotoxicity of tacrolimus and sirolimus in renal isografts: Differential intragraft expression of transforming growth factor beta-1 and alpha smooth muscle actin. Transplantation. 2004;78:338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumlin JA, Miller D, Near M, et al. A prospective, open-label trial of sirolimus in the treatment of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(1):109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu X, Ruan L, Qu Z, et al. Low-dose cyclosporine in treatment of membranous nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome: effectiveness and renal safety. Ren Fail. 2017;39(1):688–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Zhang YM, Qu Z, et al. Low-dose cyclosporine treatment in Chinese nephrotic patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy: An uncontrolled study with prospective follow-up. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(6):532–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplement 1: Study protocol

Additional file 2. Supplement 2: Full inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.