Abstract

To propose a strategy for the commercial cultivation of a Korean strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica, the growth, fatty acid content and bacterial community of N. oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources were investigated. Significant growth of N. oceanica cultured under blue (450 nm), red (620 nm) and white (cool-white fluorescent; control) light was observed, whereas growth with relatively low densities was observed in N. oceanica cultured under purple (415 nm) and yellow (592 nm) light. Cells cultured under white and blue light began growing again at day 26, after experiencing stationary phases for 7 days, indicating that day 26 may be a switching point for the growth trajectory in batch culture of N. oceanica. White light also produced the highest biomass of N. oceanica, followed by blue, red, and yellow light. These results indicate that blue and red light, excluding the white light characterized by a wide spectral band, can ensure a high growth rate and biomass of a Korean strain of N. oceanica. With respect to fatty acid content, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) was the most dominant under the yellow and red light with N. oceanica exhibiting relatively low biomass dry weight and growth rates. In bacterial communities in N. oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources, the genus Roseovarius appeared to promote the growth of N. oceanica. Based on the results of this study, the most advantageous EPA production system for a Korean strain of N. oceanica initially uses white or blue light to produce the desired cell concentration and rapid growth, then switches to red or yellow light to enhance EPA content. This two-phase cultivation approach offers a viable pathway for large-scale EPA production from native strains, with potential application in nutraceutical or aquaculture industries.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13068-025-02660-3.

Keywords: Batch culture, LED, Lipid, Growth, Bacteria

Introduction

Microalgae have been exploited to produce bulk foods, nutraceuticals, cosmetics, pharmaceutical derivatives, and biodiesel, and to treat wastewater, due to their ability to produce useful biological materials (e.g., lipids, functional pigments, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds) and nutrient requirements [1–6]. Various cultivation strategies to enhance microalgal biomass and bioproduct production have been suggested (e.g., [7–9]) and numerous equipment and technologies have been improved across the years. However, as microalgae species vary greatly in environmental requirements for growth and different strains of microalgae species can also exhibit differences in physiological activities and metabolite production in response to habitat and physico-chemical conditions, an exploration of cultivation conditions for local populations should be conducted before attempts are made to cultivate local species at commercial scale.

The genus Nannochloropsis was described by Hibberd [10] with Nannochloropsis oculata (Droop) D.J. Hibber and N. salina D.J. Hibberd as type species. Currently, seven species of Nannochloropsis, including one freshwater species (N. limnetica) and a species in the sister genus of Microchloropsis [11] have been formally described [12]. These species are frequently used as feed for marine invertebrates, as they contain highly nutritious compounds such as sterols [13] and polyunsaturated fatty acids [14]. Recently, their potential for biodiesel production has been evaluated because of their high biomass accumulation rate and lipid content [15, 16].

Among Nannochloropsis species, N. oceanica has been reported from oceans around the world, including those near Korea [17, 18]. However most of the studied strains of N. oceanica have originated in coastal areas of China, Japan, and Taiwan (e.g. [19]). In previous studies, strains of N. oceanica with high potential for producing eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) were reported from Taiwan [20, 21] and Portugal [22]. EPA plays an important role in human health and is frequently used in nutraceutical products, as EPA in the diet of humans may lower the risk of cardiovascular diseases and inhibit tumor growth [23]. Chen et al. [20, 21] investigated the factors critical to enhancing EPA production and growth of the strain of N. oceanica, finding that light sources affect both the growth and EPA accumulation in N. oceanica. Most microalgae, including N. oceanica, are unicellular eukaryotic microorganisms that use light as an energy source through photosynthesis. The effects of quality of irradiation supplied by light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the growth and bioproduct production of microalgae have been examined, intensively [16, 17, 24–28]. For example, Chen et al. [21] found that a binary combination of blue and red LEDs can produce the highest levels of EPA productivity in a Taiwan strain of N. oceanica, and Das et al. [24] reported that white light can induce the highest EPA content in Nannochloropsis species. However, gaps remain in knowledge of how microalgae respond to different light sources, as various species and strains exhibits distinct light requirements for biomass production and bioproduct synthesis (e.g. [18, 20, 21, 24, 25, 29–31]). It is, therefore, necessary to consider the growth rate and EPA content associated with productivity and response to light sources when selecting species and strains for commercial production.

Besides the light sources, several approaches to cultivation under controlled abiotic factors, such as nutrient limitation, salinity, temperature, and light cycle and intensity, are known to enhance the lipid content of microalgae cells [32–38]. In addition, microalgal-bacterial interaction studies have been conducted to enhance the growth and production of valuable algal bioproducts [39–41]. According to Lian et al. [40], the microalgal-associated bacteria can provide beneficial services to microalgae: consuming oxygen to produce carbon dioxide, decomposing and mineralizing algal waste components that can be used by microalgae, synthesizing the siderophores that can stimulate algal growth, and producing antimicrobial compounds that protect microalgae from invasion by pathogens. As a result, the culture media after algal growth can be reused for the growth of specific species [42]. Bacteria can also inhibit the microalgal growth by competing for nutrients and synthesizing algicidal compounds that can kill the algal host [43–45]. However, mutualistic relationships between bacteria and microalgae appear to be more common than antagonistic interactions [40, 46, 47]. Previous studies revealed that the interaction between bacteria and microalgae can be species-specific (e.g., [48, 49]). Bacterial diversity in many microalgal species and algal strains should be investigated to explore the function of beneficial bacteria.

Recently, Ling et al. [50], who documented the core N. oceanica-dominant bacterial microbiomes at different cultivation scales, concluded that supplementation with probiotic algae-associated bacteria can significantly enhance both biomass and EPA production in N. oceanica, Wang et al. [51] studied bacterial communities associated with N. oceanica IMET1 grown at different temperatures and Powell and Hill [52] defined the mechanism of algal aggregation by a bacterium (Bacillus sp. strain RP1137) using N. oceanica IMET1 in fixed culture conditions (temperature, salinity, light source, and cycle). However, there is a lack of studies on the bacterial diversity in N. oceanica cultured under different light sources.

This study identifies the light sources that can most efficiently enhance biomass productivity and fatty acid contents of a Korean strain of N. oceanica, especially EPA, and investigates the bacterial diversity and beneficial bacteria in N. oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources. Based on the results, we propose a potentially viable strategy for cultivating N. oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) to optimize biomass productivity and EPA content.

Materials and methods

Korean strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica

A strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica (Strain LIMS-PS-0093), which was collected from surface waters around the southern area of Korea (34°45′27.15"N, 127°13′52.32"E), was obtained from the culture collection of microalgae, at the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST). The morphology and phylogenetic position of N. oceanica based on small subunit rRNA sequences are shown in Figs. S1 and S2. The strain in KIOST has been maintained in 35 mL culture tube containing f/2 culture medium (Marine Water Enrichment Solution, Sigma Aldrich, USA) without silicate, prepared with sterile seawater (salinity of 35) (filtered through a 47 mm GF/F filter (Hyundai micro, Korea) with a pore size of 0.7 and autoclaved) at 20 °C and ca. 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1 cool-white illumination under a 10L:14D photo-cycle.

Growth experiment under different light sources

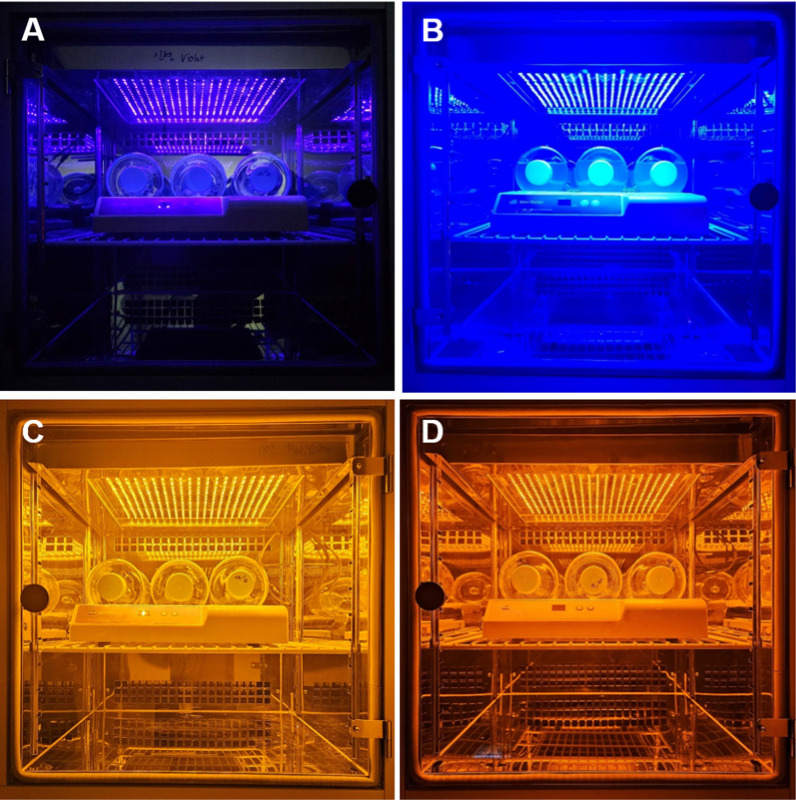

This study used four light treatments (purple, blue, yellow and red LEDs) with three replicates for cultivating Nannochloropsis oceanica (Fig. 1). LED lights were set in an individual LED incubator chamber (SJ-404 M; Sejong Scientific Co. Korea). Each LED strip in the incubator consisted of 400 diodes spaced at 1.5 cm intervals. The wavelengths of the purple, blue, yellow and red LEDs light were 415 nm, 450 nm, 592 nm and 620 nm, respectively. The light spectra of these LEDs were characterized with a fiber-based spectrometer (Hanyang Semiconductor Co. Korea). Cool-white fluorescent light was used as the control treatment in this study.

Fig. 1.

Image of cultivation of Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) in an incubator with LEDs lights. A Purple light (415 nm); B blue light (450 nm); C yellow light (592 nm); D red light (620 nm)

Filtered and autoclaved seawater collected from Jangmok Bay, Korea (34°57′52.93"N, 127°42′33.83"E) was used as basal seawater, and an f/2-Si culture medium was made using basal seawater (salinity of 35). For culture experiments, the N. oceanica strain was pre-cultured in a 1L culture bottle containing f/2-Si culture medium at 20 °C and ca. 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1 cool-white illumination under a 12L:12D photo-cycle. Growing cells of N. oceanica (at concentrations ranging from 883 to 1003 cell mL−1) were inoculated into 1L culture bottles (SPL, Korea) containing the f/2-Si culture medium, and the bottles for the treatments were placed in the incubator with LEDs lights and incubated for 36 days at 20 °C and ca. 100 µmol photons m−2 s−1 with 12L:12D photo-cycle. The light intensity was measured using a light sensor (MQ-200; Apogee, USA). Cell counts were performed every two days to monitor growth, using 1 mL subsamples fixed in Lugol’s solution (final concentration 1%). The cells were counted with a Sedgewick-Rafter counting slide on an upright microscope (ECLIPSE Ni; Nikon, Japan).

The cell density was used to calculate the specific growth rates (μ, day −1) of N. oceanica, using the following equation [53]:

Specific growth rate (μ) = ln (/) /

where N0 and Nt are the cell concentrations (cells mL−1) at the initial and final time during the incubation experiments, respectively, and is the length of exponential phase (day).

Biomass determination and fatty acids analysis

Triplicate samples of Nannochloropsis oceanica (900 mL for each culture sample) were harvested at the end of the incubation period for fatty acid analysis. The samples were centrifuged by a Combi R515 apparatus (Hanil, Korea) at 3515 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was gently removed, and the cell pellets were re-suspended with distilled water and centrifuged to remove the remaining salts. This step was repeated three times. The remaining cell pellets were frozen at −20 °C until the total fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) analysis. The frozen cell pellets were lyophilized using a freezer dryer (FDU-7012, Operon, Gimpo, Korea) at −80 °C under vacuum for 1 day, and weighed. The biomass production in this study was determined by measuring the dry cell weight (mg L−1).

FAMEs were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC2400; PerkinElmer, MA, USA). For FAME extraction, freeze-dried samples of approximately 10 mg and glass micro-beads were combined in a 2 mL screw cap tube to which 0.9 mL of a 5:100 v/v acetyl chloride: methanol (MeOH) solution and 0.1 mL of methyl heptadecanoate (3 mg mL−1) dissolved in hexane were added. The use of methanol (MeOH) and acetyl chloride as esterification agents is common, because it efficiently converts free fatty acids into their methyl esters, which are easier to analyze by gas chromatography (GC). Methyl heptadecanoate (C17:0) was used as an internal standard to normalize variability during sample preparation and GC analysis, ensuring accurate fatty acid quantification. Cell disruption was performed using a Mini-beadbeater 24 (Biospec Products, AZ, USA) for 2 min. The samples were incubated at 80 ℃, shaken at 200 rpm for 1 h using a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Germany), and then cooled for 1 min on ice, after which 1 mL of n-hexane was added and mixed for 1 min with a vortex mixer. The supernatant was separated, and 1 µL of the extract was injected into a DB-23 column (60 m × 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.15 µm film thickness). The split ratio was 1/10 and N2 was used as the carrier gas. Column temperature programs used the following procedure: 50 ℃ for 1 min, increased to 175 ℃ min−1 at 25 ℃ min−1, and then increased to 230 ℃ for 5 min at 2 ℃ min−1. The injector and detector were set at 250 ℃ and 280 ℃, respectively. FAME peaks were determined by comparing the retention times between the reference standard (Supelco 37-component FAME mix; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and the samples and quantified as the percentage area of each component of FAME. The signal data at each retention time were compared with those of the IS (Internal Standard) for a quantitative analysis.

Bacterial community profiling

Triple samples were collected at the end of the incubation period for bacterial community profiling. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration was quantified with a Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit and a Qubit™ 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA). We utilized the BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader (Agilent Technologies) to assess DNA purity. Absorbance measurements at 260 nm, 280 nm, and 230 nm were recorded, and the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios were calculated. Samples exhibiting A260/A280 ratios between 1.8 and 2.0 and A260/A230 ratios between 2.0 and 2.2 were considered to have acceptable purity levels, indicating minimal protein and organic compound contamination, respectively. Bacterial community composition was analyzed by amplifying the V5–V7 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene using the primer pair 799F (5′-AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG-3′) and 1391R (5′-ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC-3′). This primer pair was selected to minimize the amplification of non-target DNA from plant compartments [54]. The amplified DNA fragments were purified, pooled in equimolar concentrations, and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Paired-end reads were processed following methodologies described by Magoč and Salzberg [55] and Bokulich et al. [56]. Briefly, sequences were merged using FLASH (v1.2.11) and quality-filtered with fastp (v0.23.1). The QIIME2 pipeline (v2020.8) was used to process sequences [57]. Reads were demultiplexed, trimmed, and denoised with the DADA2 plugin [58] to infer amplicon sequence variants. Taxonomic classification was performed using the SILVA 138.1 reference database. Feature tables were generated for taxonomic classification at multiple levels (kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species), forming the basis of amplicon analysis. Selected taxa were used for species composition analysis and differential abundance comparisons across sample groups, facilitating clustering and in-depth investigation. To ensure standardized comparisons, the feature table for each sample was rarefied to a depth of 10,000 sequences. All raw sequencing data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA) under accession number PRJNA1223121.

Statistical analysis and data visualization

Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate samples. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were tested by Shapiro–Wilk’s W and Levene’s test, respectively. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons of differences between treatments, using MS Excel Professional Plus 2016 Analysis ToolPAK. Differences between the two treatments were assessed by an independent t-test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

To visualize and analyze differences in bacterial communities among samples, R (v4.1.0) was used. For graphical representation, the ggplot2 package was used to generate heatmaps illustrating bacterial community composition across different light treatments.

Results and discussion

Growth responses of Nannochloropsis oceanica exposed to different light sources

Significant growth of Nannochloropsis oceanica cultured under blue, red and white light (control) was observed, whereas growth with relatively low density was observed in N. oceanica cultured under purple and yellow light (Fig. 2A and Table 1). Similar growth patterns were observed in N. oceanica cultured under white and blue light (t-test, p > 0.05): cells slowly grew until day 6 of incubation and then rapid growth was observed until day 14 of incubation (the first growth phase), and cells exhibited a stationary phase for 10 days (until day 24 of incubation), and on day 26 resumed proliferating until day 32 at the highest cell density (3983 × 103 cells mL−1 for white light and 3516 × 103 cells mL−1 for blue light) (the second growth phase) (Fig. 2A). In the first phase, the growth rates of N. oceanica under white and blue lights were 0.6 ± 0.02 and 0.4 ± 0.10 day−1, respectively, and 0.10 ± 0.0 and 0.10 ± 0.0 day−1 in the second growth phase, respectively (Table 2). In N. oceanica culture exposed to red light, the growth pattern for 36 days of incubation was different from those in N. oceanica cultured under blue and white light (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). No significant change in N. oceanica cell density (< 80 X 103 cells mL−1) was observed until day 12 of incubation (lag phase); however, the cells grew slowly, and rapid growth was observed from day 26 (Fig. 2A, B and Table 1). In the N. oceanica exposed to yellow light, rapid growth was observed from day 24 to the end of incubation (0.2 ± 0.1 day −1) (Fig. 2A, Tables 1 and 2), and the maximum cell density was 1050 × 103 cells mL−1 at the end of incubation (day 36) (Fig. 2B and Table 1). Compared with N. oceanica cultures exposed to white, blue, red and yellow light, cells cultured under purple light did not grow significantly (Fig. 2B and Table 1). The dry cell weights under different light colors are presented in Table 3. White light produced the highest biomass (73.9 mg L−1) of N. oceanica, followed by blue light (72.3 mg L−1), red light (66.0 mg L−1) and yellow light (33.0 mg L−1).

Fig. 2.

Growth curve (A) and maximum cell density (B) of Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) exposed to different light sources

Table 1.

Changes in cell density (× 103 cells mL−1) of Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) cultivated under different light sources during an incubation period of 36 days

| Day | White (control) | Purple | Blue | Yellow | Red |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.0 |

| 4 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 3.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.9 |

| 6 | 14.4 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 33.2 ± 14.6 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 16.7 ± 6.6 |

| 8 | 43.8 ± 2.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 280.7 ± 50.0 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 2.3 |

| 10 | 740.0 ± 431.4 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1003.3 ± 521.6 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 19.0 ± 4.1 |

| 12 | 1060.0 ± 337.2 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1593.3 ± 443.0 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 72.9 ± 32.8 |

| 14 | 1483.3 ± 230.3 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 1640.0 ± 465.2 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 266.7 ± 118.5 |

| 16 | 1366.7 ± 439.4 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1593.3 ± 238.6 | 5.3 ± 1.0 | 430.0 ± 165.2 |

| 18 | 1700.0 ± 285.8 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1416.7 ± 350.0 | 12.0 ± 2.2 | 523.3 ± 296.7 |

| 20 | 1846.7 ± 150.4 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 1763.3 ± 431.5 | 21.1 ± 7.7 | 1046.7 ± 274.7 |

| 22 | 1733.3 ± 251.7 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 1680.0 ± 370.0 | 34.1 ± 8.7 | 1270.0 ± 206.6 |

| 24 | 1770.0 ± 121.7 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 1570.0 ± 292.1 | 100.0 ± 10.0 | 1596.7 ± 168.6 |

| 26 | 3896.7 ± 505.4 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 2670.0 ± 402.6 | 133.3 ± 66.6 | 2583.3 ± 595.4 |

| 28 | 3126.7 ± 180.4 | 3.4 ± 2.6 | 2993.6 ± 359.1 | 146.7 ± 25.2 | 2986.7 ± 185.8 |

| 30 | 3603.3 ± 352.2 | 4.4 ± 3.4 | 3150.0 ± 230.0 | 320.0 ± 85.4 | 2953.3 ± 140.1 |

| 32 | 3983.3 ± 578.3 | 6.9 ± 4.3 | 3516.7 ± 361.2 | 456.7 ± 153.1 | 3333.3 ± 165.6 |

| 34 | 3013.3 ± 181.5 | 6.9 ± 4.2 | 2900.0 ± 101.5 | 700.0 ± 300.5 | 2876.7 ± 344.4 |

| 36 | 3233.3 ± 310.1 | 7.8 ± 4.5 | 2976.7 ± 145.7 | 1050.0 ± 461.6 | 2560.0 ± 225.4 |

Table 2.

Growth rates (day −1) and maximum cell densities (× 103 cells mL−1) of Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) cultivated at different light sources

| Light source | Growth rate | Maximum cell density |

|---|---|---|

| White (control) | 0.6 ± 0.0 (0.1 ± 0.0) | 3983.3 ± 578.3 |

| Purple | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 4.5 |

| Blue | 0.4 ± 0.1 (0.1 ± 0.0) | 3516.7 ± 361.2 |

| Yellow | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1050.0 ± 461.6 |

| Red | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 3333.3 ± 165.6 |

Values in parentheses are the growth rate in the second growth phase

Table 3.

Fatty acid profile and content, and biomass density in cultures of Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) exposed to different light sources

| Fatty acid | White (control) | Blue | Yellow | Red |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12:0 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| 14:0 | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| 16:0 | 25.5 ± 1.4 | 30.6 ± 1.4 | 24.9 ± 0.3 | 21.9 ± 1.9 |

| 16:1 | 21.8 ± 0.1 | 20.6 ± 1.4 | 24.7 ± 0.7 | 24.4 ± 0.2 |

| 18:0 | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.1 |

| 18:1 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 0.3 |

| 18:2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.0 |

| 20:4 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 |

| 20:5 | 26.3 ± 0.1 | 24.7 ± 1.4 | 30.8 ± 1.9 | 30.6 ± 3.3 |

| Total fatty acid (mg g−1) | 47.2 ± 11.4 | 43.4 ± 1.6 | 71.8 ± 8.9 | 72.4 ± 8.1 |

| Biomass production (mg L−1) | 73.9 ± 7.8 | 72.3 ± 12.6 | 33.0 ± 23.9 | 66.0 ± 8.4 |

Values of each fatty acid are given as the percentage of total fatty acid methyl esters

According to the evolutionary history of microalgal pigments illustrated by Keeling [59], blue and red lights are seen to be the most preferred spectral choice for the growth of microalgae, and actually, previous studies reported that the blue or red light can enhance the growth of microalgae [18, 24, 25, 30, 60–62]. Similar results were obtained in this study; compared with yellow and purple light, blue and red light were associated with high growth rates and maximum cell densities of N. oceanica, and relatively high biomass was also produced from the cultures of N. oceanica exposed to blue light. This is not surprising, because the photosynthetic apparatus of Nannochloropsis species depends solely on chlorophyll a, which is responsible for absorbing blue and red light [63, 64]. However, compared with blue and red light, N. oceanica grown under white fluorescent light had the highest growth rate and maximum cell density, although similar growth patterns of N. oceanica were observed under both white and blue light. Comparable results have been reported for the cultures of some Nannochloropsis species. According to Chen et al. [21], illumination with a fluorescent light source can be used to ensure optimal cell growth of N. oceanica, and Chen and Lee [65] and Schulze et al. [26] reported that cell density of N. oculata is higher under a fluorescent lamp. Vadiveloo et al. [66] noted that, compared with Nannochloropsis sp. exposed to blue and red lights [65], the species grown under white light exhibits greater cell density and a higher growth rate. In contrast, Ra et al. [18] found no significant differences in the growth rates and biomasses of N. salina and N. oceanica cultured under blue, red, and white light, but concluded that a binary combination of blue and red light can produce the high biomass in N. salina and N. oceanica. In addition, Chen et al. [21] documented that three binary combinations of different colors (red–yellow, blue–red and blue–yellow) can lead to higher biomass productivity of N. oceanica, compared with that under a single wavelength (blue light). These results suggest that the growth response and biomass of Nannochloropsis species under different light qualities can vary among strains of the same species, and that blue and red light ensure high growth and biomass production in Nannochloropsis species, because white light has a wide spectral band that includes a single wavelength such as blue and red light. According to Sforza et al. [67], Nannochloropsis species has been found to have a flexible photosynthetic apparatus, which can acclimate to a wide range of constant and varying light intensities. In addition, photosynthesis is one of the most thermally sensitive processes in microalgae [68]. However, a comprehensive comparison of N. oceanica growth under variable temperatures has not yet been conducted. Further studies are required to clarify the relationships between N. oceanica growth and environmental factors such as different light sources, variable light intensity, and temperature.

Interestingly, the cells cultured under white and blue light grew again from day 26 (the second growth phase), after experiencing a stationary phase for 7 days (days 12–24) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The stationary phase in a microalgae batch culture is often observed when the nutrients in the culture medium are exhausted by the microalgae [7]. Ra et al. [18] observed that the stationary phase in the batch culturing of N. oceanica coincides with the stage of depleted nitrate concentrations at 10 or 11 days. This indicates that the arrival time (day 12) to the stationary phase was determined by the nutrient-depleted conditions in the N. oceanica culture under white and blue light. After the stationary phase, the microalgae generally enter a death phase, with a rapid decline in cell concentration [7]. However, the concentrations of N. oceanica cultured under white and blue light doubled without a death phase (to day 26). This may be attributed to the recycling of nutrients in the batch culture, because viable cells can grow by consuming recycled nutrients from dead and decaying cells in the stationary phase (e.g., [42, 69]). It is, therefore, possible that the cultivation water of N. oceanica can be reused to stimulate microalgal growth, although the effects of reused water on algae growth differ across algae taxa [42].

Despite the fact that N. oceanica cultured under red light did not experience a stationary phase, cell density increased from day 26 rapidly, and the growth pattern from day 26 was similar to that in blue light conditions (t-test, p > 0.05) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). In addition, rapid growth from day 24 was observed, even in N. oceanica exposed to yellow light that experiences inhibited growth. This indicates that in a 1L batch culture of N. oceanica under our culture conditions, day 24 or 26 can be a switching point for the growth trajectory. This cultivation time should, therefore, be considered to produce the desire cell concentration when the working volume for culturing N. oceanica increases.

Fatty acid profiles and contents in Nannochloropsis oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources

The fatty acid composition of Nannochloropsis oceanica cultured under white (control), blue, yellow and red lights included the saturated fatty acids C12:0 (lauric acid), C14:0 (myristic acid), C16:0 (palmitic acid) and C18:0 (stearic acid), the monounsaturated fatty acids C16:1 (palmitoleic acid) and C18:1n9c (oleic acid), and the polyunsaturated fatty acids C18:2n6c (linoleic acid), C20:4n6 (arachidonic acid; ARA) and C20:5n3 (EPA) (Fig. 3 and Table 3). No compositional changes were seen in the fatty acids of N. oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources, indicating that the fatty acids for N. oceanica are not controlled by the light quality. Ma et al. [16] examined the fatty acid profile of 9 Nannochloropsis strains including N. gaditana, N. salina, N. granulata, N. limnetica, N. oculate and N. oceanica cultivated in seawater, and documented that C16:0, C16:1, C18:1n9c, C20:4n6 and C20:5n3 are major fatty acids in nine Nannochloropsis strains. This finding is in accordance with our observations, although C18:1n9c in the Korean strain of N. oceanica was present at lower percentages, compared with the other Nannochloropsis strains. This fatty acid profile was also observed in an N. oceanica strain from the coast of southern Taiwan [20]. According to a review by Maltsev and Maltseva [5], the main fatty acid profiles of microalgae can be used as taxonomic biomarkers for the division and class level; however, the profiles have been ambiguous at the species level of the same genus and in different strains of the same species. Nevertheless, the Nannochloropsis species cultivated in seawater may be characterized by the specific fatty acid profile, because Ma et al. [16] observed that when N. limnetica from freshwater was cultivated in seawater, the fatty acid profile in freshwater changed to that of the Nannochloropsis strains cultivated in seawater. In particular, EPA (C20:5n3) appears to be more common in the fatty acids of Nannochloropsis species, as described by many previous studies (e.g., [16, 20–22, 70, 71]).

Fig. 3.

Fatty acid content in Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) cultures exposed to different light sources

The total fatty acid contents of N. oceanica cultured under white, blue, yellow, and red light were 47.2, 43.4, 71.8 and 72.4 mg g−1, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3). In the N. oceanica cultures exposed to the yellow and red light, relatively more EPA content was detected (22.2 mg g−1 (30.8%) for yellow light and 22.3 mg g−1 (30.6%) for red light), whereas the EPA content in N. oceanica cultured under white and blue light were 12.4 mg g−1 (26.3%) and 10.7 mg g−1 (24.6%), respectively (Table 3). In addition, the monounsaturated fatty acid, C16:1 (palmitoleic acid), was higher in N. oceanica cultured under red (24.4%) and yellow (24.7%) light, than white (21.8%) and blue (20.6%) light (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The EPA contents were the most dominant in N. oceanica cultures exposed to yellow and red light; however, in the N. oceanica culture exposed to blue light the dominant fatty acid was palmitic acid, and the EPA and palmitic acid contents were similar in N. oceanica cultures exposed to white light (Fig. 3 and Table 3). ARA was also detected in N. oceanica cultures exposed to all light, and the ARA content was relatively low in N. oceanica cultured under a blue light (Table 3).

According to Ma et al. [16], N. oceanica lMET1 is the best strain for biodiesel production, based on the high lipid productivity, triacylglyceride production, and favorable fatty acid contents of C16-C18 (56.62 ± 1.96%). Similar fatty acid contents of C16-C18 (61.50–66.88%) were also observed in this study, and no significant differences in the values between light sources (one-way ANOVA, p > 0.05) were visible. In addition, the Korean strain of N. oceanica contained 25.02–32.73% monounsaturated fatty acids (palmitoleic and oleic acids), producing an optimal compromise between oxidative stability and cold flow in biodiesel fuel (e.g., [72]). This indicates that the Korean strain of N. oceanica may be useful as a biodiesel feedstock. However, as the EPA content that can result in low oxidative stability was quite different from other strains of Nannochloropsis species (2.90–12.74%) examined by Ma et al. [16] and some strains of N. oceanica [18, 20, 21], the Korean strain of N. oceanica is likely to be more useful for the EPA production, rather than biodiesel production.

According to Chen et al. [20], blue light stimulates N. oceanica to produce EPA, but significantly inhibits cell growth. By contrast, in this study the EPA content was the lowest and the growth was not inhibited in N. oceanica cultured under a blue light. This trend was also evident in the N. oceanica culture exposed to white light. Numerous studies investigated the responses of fatty acid in Nannochloropsis species to the stressful conditions controlled by light, temperature, salinity and nutrients, and as a consequence, stress-induced conditions could enhance the fatty acid content and hinder cell growth (e.g., [5, 38, 73–80]). According to Ma et al. [37], the biosynthesis and accumulation of storage neutral lipids appear to be a protective reaction in response to stress conditions, however, the studies on lipid biosynthesis and regulation in Nannochloropsis species are limited. In this study, when compared with N. oceanica cultured under white and blue light, the red and yellow light exhibited relatively low biomasses dry weight and growth rates of N. oceanica and induced a relatively high EPA content, as well as ARA content. This result indicates that red and yellow light treatments can impose stress on the Korean strain of N. oceanica but serve as suitable artificial light sources for the EPA production. The preferred light source for EPA production therefore varies among strains of N. oceanica. Previous studies investigated the relationship between ultraviolet light (UV) and microalgae growth and found that, under the stress of UV light, microalgae may alter the proportions of their unsaturated fatty acids [81, 82]. However, insufficient numbers of cells were harvested from an N. oceanica culture exposed to near-UV light (415 nm), and the EPA content could not be evaluated.

Bacterial communities in Nannochloropsis oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources

Bacterial diversity and clusters in Nannochloropsis oceanica cultures exposed to white (control), blue, red, yellow and purple light are shown in Fig. 4 and Supplementary data. At the class level, the bacterial communities in N. oceanica cultures exposed to different light sources were dominated by Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria; the Alphaproteobacteria accounted for 91.3% under blue light, 74.1% under red light, 54.3% under white light, 39.3% under yellow light, and 8.3% under purple light, whereas the Gammaproteobacteria accounted for 91.7% under purple light, 60.7% under yellow light, 45.7% under white light, 25.9% under red light, and 8.7% under blue light. Interestingly, the contrast proportions of the two bacterial classes, Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria, were found for each light source. The class Bacilli, with a low proportion (0.003%), was also found for only red light. Previous studies documented that Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria are the dominant groups associated with strains of N. oceanica IMET1 [51, 83] and N. oceanica KB1 [41]. In addition, Nakase and Eguchi [84] reported that, in cultures of unspecified Nannochloropsis species Alphaproteobacteria was most abundant in the bacterial community of actively growing cells. Similar results in the current study were obtained for relative proportions of the Alphaproteobacteria cultivated under blue, red, and white light that N. oceanica relatively exhibited high growth rates and cell densities, and a preliminary examination also revealed a positive correlation for concentrations of bacteria and N. oceanica cultivated under white light (Fig. S3, r = 0.91). This indicates that Alphaproteobacteria can be an important contributor to the growth of Nannochloropsis species. In contrast, Gammaproteobacteria exhibited low proportions under the blue and red light, as well as white light characterized by a wide spectral band. A high proportion was observed under the purple and yellow light that relatively low cell densities of N. oceanica were observed during incubation. In general, excitation with near-UV light tends to inhibit bacterial growth (e.g., [85]). However, the high proportion of Gammaproteobacteria in the N. oceanica culture exposed to purple light (415 nm) may be due to a reduction in the proportion of Alphaproteobacteria. which may be more sensitive to exposure to purple light compared with Gammaproteobacteria.

Fig. 4.

Clustering heatmap based on Pearson correlation coefficients, illustrating the similarity between bacterial communities associated with Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093) cultured under different light sources. The color intensity represents the relative abundance of bacterial taxa, with darker shades indicating higher abundance. The hierarchical clustering dendrogram at the top groups samples based on bacterial community composition, highlighting differences and similarities across light treatments (purple light: 415 nm, blue light: 450 nm, yellow light: 592 nm, red light: 620 nm, and control)

The bacterial community at the genus level was similar in N. oceanica cultures exposed to blue and white (control) light, whereas under purple and yellow light the bacterial communities were grouped together, and those under red light had a close relationship with this group (Fig. 4). At the genus level, Marinobacter (class Gammaproteobacteria) and Roseovarious (class Alphaproteobacteria) were found to occur most frequently under different light sources; Marinobacter accounted for 91.1% under purple light, 59.4% under yellow light, 42.7% under white light, 24.7% under red light, and 8.1% under blue light, whereas Roseovarius was the most abundant genus under blue light (90.3%), followed by red light (67.9%), white light (51.0%), yellow light (26.6%), and purple light (6.1%). Under white light, the relative abundance of Roseovarius was twice that of Marinobacter. In addition, Maricaulis (class Alphaproteobacteria) was abundant in an N. oceanica culture exposed to yellow light (12.7%). Genus Maricaulis has been frequently detected and associated with toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates in culture [86–88], but the ecophysiological function in microalgae is not known. According to Liu et al. [41], in the co-cultivation of bacteria with N. oceanica KB1 some bacterial strains are quite effective for growth promotion and EPA production of the strain (KB1), and a higher relative abundance of the genus Marinobacter was found in growing culture of the strain. In contrast, in our study the genus Marinobacter does not appear to be related to enhance growth of the Korean strain of N. oceanica, because the lowest abundance of the Marinobacter was observed under blue light that N. oceanica exhibited high cell density and lower relative abundance of genus Marinobacter was also found in the white light. Members of the genus Marinobacter is one of the bacterial organisms that may have relationships with Nannochloropsis species [41]. However, as the interactions between bacteria and microalgae are species-specific and can vary among strains of the same microalgal species (e.g., [89, 90]), further studies are required to clarify the role of genus Marinobacter for the Korean strain of N. oceanica.

In the current study, the growth promotion of the Korean strain of N. oceanica appears to be related to Roseovarius rather than Marinobacter. Previous studies revealed that the abundance of the genus Roseovarius was correlated with chlorophyll a concentrations at a global scale, which suggests an association with phytoplankton communities [91–93]. Johansson et al. [94] and Hosseini et al. [95] reported that Roseovarius has algae growth-promoting properties, and Yao et al. [96] also documented that this genus of bacteria produces morphogenic compounds with cytokinin functions which promote cell division and growth. It is therefore possible that the growth of the Korean strain of N. oceanica cultivated under blue, red, and white light is associated with Roseovarius, although a co-culture of Roseovarius and the Korean strain of N. oceanica was not examined in this study. Recently, Vacant et al. [97] concluded that Roseovarius has a beneficial effect on the long-term survival of microalgal cultures, because of their ability to produce vitamin B12. Indeed, cultivating Nannochloropsis species in a vitamin-free f/2 medium led to a decrease in the growth rate [98, 99]. This indicates that the growth stimulation (the second growth phase) and long-term survival of N. oceanica under blue, white, and red light (from day 24 of incubation), and probably including yellow light, may be attributable to the activity of the Roseovarius.

Cultivation strategy for enhancing growth and EPA production of the Korean strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica

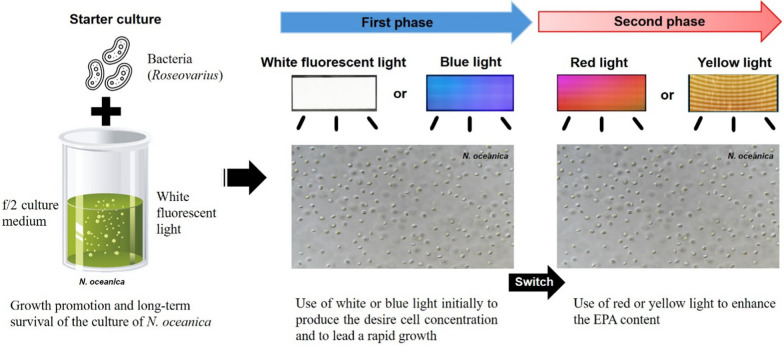

Species and strain selection is the first and most important step in bio-prospecting microalgae for any commercial application [100]. In the current study, the experiments clearly showed that the Korean strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica is likely more useful for EPA production. As specific light sources may enhance the growth and EPA production of the strain, we propose an effective cultivation strategy for the strain. Based on the growth responses and fatty acid contents of the Korean strain of N. oceanica cultured under different light sources, a two-phase culture appears an effective strategy for high biomass and EPA productions (e.g., [36, 101]); the first phase is for high biomass production, and the second phase is aimed at high EPA production (Fig. 5). More precisely, the most advantageous EPA production system for the Korean strain of N. oceanica is to use white or blue light in the initial stages to produce the desire cell concentration and generate rapid growth, then switch to red or yellow light to enhance EPA content.

Fig. 5.

Illustration of a cultivation strategy to improve the growth and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) production of a Korean strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica (LIMS-PS-0093)

Co-cultivation of microalgae and bacteria may promote growth and enhance the production of valuable algal bioproducts. The genus Roseovarius appears to be beneficial to the Korean strain of N. oceanica, and if the bacteria has a beneficial effect on the long-term survival of the culture of N. oceanica (e.g., [97]), co-cultivation of Roseovarius species and N. oceanica may be able to be used to maintain stock or stater culture. However, further studies are required to clarify the role of the genus Roseovarius in the Korean strain of N. oceanica.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of different light qualities on the growth, fatty acid content, and bacterial communities of the Korean strain of Nannochloropsis oceanica. The results showed that white and blue light promoted significantly higher cell densities and biomass production, while red and yellow light induced relatively lower growth but resulted in increased EPA production. Bacterial community analysis revealed a strong association between high proportions of the genus Roseovarius and enhanced algal growth under white and blue light qualities. This finding suggests that co-cultivation with the genus Roseovarius may be beneficial for sustaining long-term cultures of N. oceanica. Based on the observed growth patterns and fatty acid content, a two-phase cultivation strategy is proposed to optimize both biomass and EPA production: the initial phase under white or blue light to achieve high cell densities, followed by a second phase under red or yellow light to enhance EPA accumulation. This cultivation approach, potentially combined with co-cultivation with Roseovarius, may offer an effective method for the commercial application of the Korean strain of N. oceanica for EPA production.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Korean Microalgae Culture Collection (KMCC) for providing a microalgal culture.

Author contributions

Kyong Ha Han: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Visualization. Zhun Li: Data curation, Methodology, Writing- review & editing, Visualization. Bum Soo Park: Methodology, Writing- review & editing, Visualization. Min Seok Jung: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization. Min Jae Kim: Data curation, Writing- review & editing. Kae Kyong Kwon: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. Joo Yeon Youn: Data curation, Formal analysis. Ji Hoon Lee: Writing- review & editing. Da Bin Choi: Formal analysis. Joo-Hwan Kim: Methology. Daekyung Kim: Formal analysis. Hyeon Ho Shin: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Writing-original draft, review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Marine Biotics (20210469) and Marine Biotoxin (RS-2025-02292973) projects funded by the Ministry of Ocean and Fisheries, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-RS-2025-00523322), and the management of Marine Fishery Bio-Resources Center (2025) funded by the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK).

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Milledge JJ. Commercial application of microalgae other than as biofuels: a brief review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2011;10:31–41. 10.1007/s11157-010-9214-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klinthong W, Yang YH, Huang CH, Tan CS. A review: microalgae and their applications in CO2 capture and renewable energy. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2015;15(2):712–42. 10.4209/aaqr.2014.11.0299. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhalamurugan GL, Valerie O, Mark L. Valuable bioproducts obtained from microalgae biomass and their commercial applications: a review. Environ Eng Res. 2018;23(3):229–41. 10.4491/eer.2017.220. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun XM, Ren LJ, Zhao QY, Ji XJ, Huang H. Microalgae for the production of lipid and carotenoids: a review with focus on stress regulation and adaptation. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. 2018;11:272. 10.1186/s13068-018-1275-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maltsev Y, Maltseva K. Fatty acids of microalgae: diversity and application. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2021;20:515–47. 10.1007/s11157-021-09571-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatnagar P, Gururani P, Gautam P, Vlaskin MS, Kumar V. Review on microalgae protein and its current and future utilization in the food industry. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2024;59(1):473–80. 10.1111/ijfs.16586. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee E, Jalalizadeh M, Zhang Q. Growth kinetic models for microalgae cultivation: a review. Algal Res. 2015;12:497–512. 10.1016/j.algal.2015.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan JS, Lee SY, Chew KW, Lam MK, Lim JW, Ho SH, et al. A review on microalgae cultivation and harvesting, and their biomass extraction processing using ionic liquids. Bioengineered. 2020;11(1):116–29. 10.1080/21655979.2020.1711626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin S, Wang K, Gao F, Ge B, Cui H, Li W. Biotechnologies for bulk production of microalgal biomass: from mass cultivation to dried biomass acquisition. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. 2023;16:131. 10.1186/s13068-023-02382-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibbered DJ. Notes on the taxonomy and nomenclature of the algal classes Eustigmatophyceae and Tribophyceae (synonym Xanthophyceae). Bot J Linn Soc. 1981;82(2):93–119. 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1981.tb00954.x. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fawley MW, Jameson I, Fawley KP. The phylogeny of the genus Nannochloropsis (Monodopsidaceae, Eustigmatophyceae), with descriptions of N. australis sp. Nov. and Microchloropsis gen. nov. Phycologia. 2015;54(5):545–52. 10.2216/15-60.1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guiry MD, Guiry GM. AlgaeBase. “Worldwide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway.” http://www.algaebase.org. Accessed 07 Oct 2019.

- 13.Véron B, Dauguet JC, Billard C. Sterolic biomakers in marine plankton. II. Free and conjugated sterols of seven species used mariculture. J Phycol. 1998;34(2):273–9. 10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340273.x. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha JM, Gracia JE, Henriques MH. Growth aspects of the marine microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana. Biomol Eng. 2003;20(4–6):237–42. 10.1016/S1389-0344(03)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Liu T, Zhang W, Chen XL, Wang JF. Biodiesel production from algae oil high in fatty acids by two-step catalytic conversion. Bioresour Technol. 2012;111:208–14. 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y, Wang Z, Yu C, Yin Y, Zhou G. Evaluation of the potential of 9 Nannochloropsis strains for biodiesel production. Bioresour Technol. 2014;167:503–9. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ra CH, Kang CH, Jung JH, Jeong GT, Kim SK. Effects of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the accumulation of lipid content using a two-phase culture process with three microalgae. Bioresour Technol. 2016;212:254–61. 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ra CH, Sirisuk P, Jung JH, Jeong GT, Kim SK. Effects of light-emitting diode (LED) with a mixture of wavelengths on the growth and lipid content of microalgae. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2018;41:457–65. 10.1007/s00449-017-1880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zanella L, Vianello F. Microalgae of the genus Nannochloropsis: chemical composition and functional implications for human nutrition. J Funct Foods. 2020;68:103919. 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103919. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CY, Chen YC, Huang HC, Huang CC, Lee WL, Chang JS. Engineering strategies for enhancing the production of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) from an isolated microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica CY2. Bioresour Technol. 2013;147:160–7. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CY, Chen YC, Huang HC, Ho SH, Chng JS. Enhancing the production of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) from Nannochloropsis oceanica CY2 Using innovative photobioreactors with optimal light source arrangements. Bioresour Technol. 2015;191:407–13. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sá M, Ferrer-Ledo N, Wijffels R, Crespo JG, Barosa M, Galinha CF. Monitoring of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) production in the microalgae Nannochloropsis oceanica. Algal Res. 2020;45:101766. 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101766. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruxton CHS, Calder PC, Reed SC, Simpson MJA. The impact of long chain n 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on human health. Nutr Res Rev. 2005;18(1):113–29. 10.1079/NRR200497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das P, Lei W, Aziz SS, Obbard JP. Enhanced algal growth in both phototrophic and mixotrophic culture under blue light. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(4):3883–7. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teo CL, Atta M, Bukhari A, Tasir M, Yusuf AM, Idris A. Enhancing growth and lipid production of marine microalgae for biodiesel production via the use of different LED wavelengths. Bioresour Technol. 2014;162:38–44. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulze PSC, Pereira HGC, Santos TFC, Schueler L, Guerra R, Barreira LA, et al. Effect of light quality supplied by light emitting diodes (LEDs) on growth and biochemical profiles of Nanochloropsis oculata and Tetraselmis chuii. Algal Res. 2016;16:387–98. 10.1016/j.algal.2016.03.034. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SH, Sunwoo IY, Hong HJ, Awah CC, Jeong GT, Kim SS. Lipid and unsaturated fatty acid productions from three microalgae using nitrate and light-emitting diodes with complementary LED wavelength in a two phase culture system. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2019;42:1517–26. 10.1007/s00449-019-02149-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baidya A, Akter T, Islam MR, Azad Shah AKM, Hossain MA, Salam MA, et al. Effect of different wavelengths of LED light on the growth, chlorophyll, β-carotene content and proximate composition of Chlorella ellipsoidea. Heliyon. 2021;7(12):e08525. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthijs HCP, Baike H, Vans Hes UM. Application of light-emitting diodes in bioreactor: flashing light effect and energy economy in algal culture (Chlorella pyrenoidosa). Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;50(1):98–107. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960405)50:1%3c98::AID-BIT11%3e3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang CY, Fu CC, Liu YC. Effects of using light-emitting diodes on the cultivation of Spirulina platensis. Biochemi Eng J. 2007;37(1):21–5. 10.1016/j.bej.2007.03.004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutaf T, Oz Y, Kose A, Elibol K, Onceal SS. The effect of medium and light wavelength towards Stichococcus bacillaris fatty acid production and composition. Bioresour Technol. 2019;289:121732. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahidin S, Idris A, Muhamad Shaleh SR. The influence of light intensity and photoperiod on the growth and lipid content of microalgae Nannochloropsis sp. Bioresour Technol. 2013;129:7–11. 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khatoon H, Rahman NA, Banerjee S, Harun N, Suleiman SS, Zakaria NH, et al. Effects of different salinities and pH on the growth and proximate composition of Nannochloropsis sp. and Tetraselmis sp. isolated from South China Sea cultured under control and natural condition. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2014;95:11–8. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.06.022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benvenuti G, Bosma R, Cuaresma M. Selecting microalgae with high lipid productivity and photosynthetic activity under nitrogen starvation. J Appl Phycol. 2015;27:1425–31. 10.1007/s10811-014-0470-8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fakhry EM, Maghraby DME. Lipid accumulation in response to nitrogen limitation and variation of temperature in Nannochloropsis salina. Bot Stud. 2015;56:6. 10.1186/s40529-015-0085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitra M, Patidar SK, Mishra S. Intergrated process of two stage cultivation of Nannochloropsis sp. for nutraceutically valuable eicosapentaenoic acid along with biodiesel. Bioresour Technol. 2015;193:363–9. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma XN, Chen TP, Yang B, Liu J, Chen F. Lipid production from Nannochloropsis. Mar Drugs. 2016;14(4):61. 10.3390/md14040061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hulatt CJ, Wijffels RH, Bolla S, Kiron V. Production of fatty acids and protein by Nannochloropsis in flat-plate photobioreactors. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0170440. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim BH, Ramanan R, Cho DH, Oh HM, Kim HS. Role of Rhizobium, a plant growth promoting bacterium, in enhancing algal biomass through mutualistic interaction. Biomass Bioenergy. 2014;69:95–105. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.07.015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lian J, Wijffels RH, Smidt H, Sipkema D. The effect of the algal microbiome on industrial production of microalgae. Microb Biotechnol. 2018;11(5):806–18. 10.1111/1751-7915.13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu B, Eltanahy EE, Liu H, Chua ET, Thomas-Hall SR, Wass TJ, et al. Growth-promoting bacteria double eicosapentaenoic acid yield in microalgae. Bioresour Technol. 2020;316:123916. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Z, Loftus S, Sha J, Wang W, Park MS, Zhang X, et al. Water reuse for sustainable microalgae cultivation: current knowledge and future directions. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020;161:104975. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104975. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fukami K, Nishijima T, Ishida Y. Stimulative and inhibitory effects of bacteria on the growth of microalgae. Hydrobiologia. 1997;358:185–91. 10.1023/A:1003139402315. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayali X, Azam F. Algicidal bacteria in the sea and their impact on algal bloom. J Eukayotic Microbiol. 2004;51(2):139–44. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guldhe A, Kumari S, Ramanna L, Ramsundar P, Singh P, Rawat I, et al. Prospects, recent advancements and challenges of different wastewater streams for microalgal cultivation. J Environ Manage. 2017;203(1):299–315. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amin SA, Parker MS, Armbrust EV. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76(3):667–84. 10.1128/mmbr.00007-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seymour JR, Amin SA, Raina JB, Stocker R. Zooming in on the phycosphere: the ecological interface for phytoplankton-bacteria relationships. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17065. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruckner C, Rehm C, Grossart HP, Kroth PG. Growth and release of extracellular organic compounds by benethic diatoms depends on interactions with bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13(4):1052–63. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Le Chevanton M, Garnier M, Bougaran G, Schreiber N, Lukomska E, Bérard JB, et al. Screening and selection of growth-promoting bacteria for Dunaliella cultures. Algal Res. 2013;2(3):212–22. 10.1016/j.algal.2013.05.003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ling T, Zhang YF, Cao JY, Xu JL, Kong ZY, Zhang L, et al. Analysis of bacterial community diversity within seven bait-microalgae. Algal Res. 2020;51:102033. 10.1016/j.algal.2020.102033. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Laughinghouse HD IV, Anderson MA, Chen F, Willlams E, Place AC, et al. Novel bacterial isolate from Permian groundwater, capable of aggregating potential biofuel-producing microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica IMET1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(5):1445–53. 10.1128/AEM.06474-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powell RJ, Hill RT. Mechanism of algal aggregation by Bacillus sp. strain RP1137. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(13):4042–50. 10.1128/AEM.00887-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guillard RRL. Division rates. In: Stein JR, editor. Handbook of phycological methods: culture methods and growth measurement. London: Cambridge University Press; 1973. p. 2289–311. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beckers B, Beeck MOD, Thijs S, Truyens S, Weyens N, Boerjan W, et al. Performance of 16s rDNA primer pairs in the study of rhizosphere and endosphere bacterial microbiomes in metabarcoding studies. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:650. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(21):2957–63. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:57–9. 10.1038/nmeth.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Ghalith GAA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–7. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li M, Shao D, Zhou J, Gu J, Qin J, Chen W, et al. Signatures within esophageal microbiota with progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32(6):755–67. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.06.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keeling PJ. The number, speed, and impact of plastid endosymbioses in eukaryotic evolution. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:583–607. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palsson BØ, Lee CG. Photoacclimation of Chlorella vulgaris to red light from light emitting diodes leads to autospore release following each cellular division. Biotechnol Prog. 1996;12(2):249–56. 10.1021/bp950084t. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abiusi F, Sampietro G, Marturano G, Biondi N, Rodolfi L, D’Ottavio M, et al. Growth, photosynthetic, efficiency, and biochemical composition of Tetraselmis suecica F&M-M33 grown with LEDs of different colors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;111(5):956–64. 10.1002/bit.25014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koc C, Anderson GA, Kommareddy A. Use of red and blue light-emitting diodes (LED) and fluorescent lamps to grow microalgae in a photobioreactor. Isr J Aquacult. 2013;65:797. 10.46989/001c.20661. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kandilian R, Lee E, Pilon L. Radiation and optical properties of Nannochloropsis oculata grown under different irradiances and spectra. Bioresour Technol. 2013;137:63–73. 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tamburic B, Szabó M, Tran NT, Larkum AWD, Suggett DJ, Ralph PJ. Action spectra of oxygen production and chlorophyll a fluorescence in the green microalga Nannochloropsis oculata. Bioresour Technol. 2014;169:320–7. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen YC, Lee MC. Double power double-heterostructure light-emitting diodes in microalgae, Spirulina platensis and Nannochloropsis oculata, cultures. J Mar Sci Technol. 2012;20(2):233–6. 10.51400/2709-6998.1843. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vadiveloo A, Moheimani NR, Cosgrove JJ, Bahri PA, Parlevilet D. Effects of different light spectra on the growth and productivity of acclimated Nannochloropsis sp. (Eutigmatophyceae). Algal Res. 2015;8:121–7. 10.1016/j.algal.2015.02.001. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sforza E, Simionato D, Giacometti GM, Bertucco A, Morosinotto T. Adjusted light and dark cycles can optimize photosynthetic efficiency in algae growing in photobioreactors. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38975. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davison I. Environmental effects on algal photosynthesis: temperature. J Phycol. 1991;27:2–8. 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1991.00002.x. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steinrücken P, Jackson S, Müller O, Puntervoll P, Kleinegris DMM. A closer look into the microbiome of microalgal cultures. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1108018. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1108018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patil V, Källqvist T, Olsen E, Vogt G, Gislerød HR. Fatty acid composition of 12 microalgae for possible use in aquaculture feed. Aquacult Int. 2007;15:1–9. 10.1007/s10499-006-9060-3. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Udayan A, Sabapathy H, Arumugam M. Stress hormones mediated lipid accumulation and modulation of specific fatty acids in Nannochloropsis oceanica CASA CC201. Bioresour Technol. 2020;310:123437. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knothe G. Improving biodiesel fuel properties by modifying fatty ester composition. Energy Environ Sci. 2009;2(7):759–66. 10.1039/b903941d. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Solovchenko A, Khozin-Goldberg I, Recht L, Boussiba S. Stress-induced changes in optical properties, pigment and fatty acid content of Nannochloropsis sp.: implications for non-destructive assay of total fatty acids. Mar Biotechnol. 2011;13:527–35. 10.1007/s10126-010-9323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Solovchenko A, Lukyanov A, Solovchenko O, Didi-Cohen S, Boussiba S, Kozin-Goldberg I. Interactive effects of salinity, high light, and nitrogen starvation on fatty acid and carotenoid profiles in Nannochloropsis oceanica CCALA 804. Eur J Lipd Sci Technol. 2014;116(5):635–44. 10.1002/ejlt.201300456. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao Y, Zhang J, Cui J, Yao X, Sun Z, Feng Y, et al. Simultaneous accumulation of neutral lipids and biomass in Nannochloropsis oceanica IMET1 under high light intensity and nitrogen replete conditions. Algal Res. 2015;11:55–62. 10.1016/j.algal.2015.05.019. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Willette S, Gill SS, Dungan B, Schaub TM, Jarvis JM, Hilarie RS, et al. Alterations in lipidome and metabolome profiles of Nannochloropsis salina in response to reduced culture temperature during sinusoidal temperature and light. Algal Res. 2018;32:79–92. 10.1016/j.algal.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaignard C, Zissis G, Buso D. Influence of different abiotic factors on lipid production by microalgae-a review. OCL. 2021;28:57. 10.1051/ocl/2021045. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sousa S, Feritas AC, Gomes AM, Cavalho AP. Modulated stress to balance Nannochloropsis oculata growth and eicospentaenoic acid production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106:4017–27. 10.1007/s00253-022-11968-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sousa SC, Machado M, Freitas AC, Gomes AM, Carvalho AP. Can growth of Nannochloropsis oculata under modulated stress enhance its lipid-associated biological properties? Mar Drugs. 2022;20(12):737. 10.3390/md20120737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Udayan A, Pandey AK, Sirohi R, Sreekumar N, Sang BI, Sim SJ, et al. Production of microalgae with high lipid content and their potential as sources of neutraceuticals. Phytochem Rev. 2023;22:833–60. 10.1007/s11101-021-09784-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guihéneuf F, Fouqueray M, Mimouni V, Ulmann L, Jacquette B, Tremblin G. Effect of UV stress on the fatty acid and lipid class composition in two marine microalgae Pavlova lutheri (Pavlovophyceae) and Odontella aurita (Bacillariophyceae). J Appl Phycol. 2010;22:629–38. 10.1007/s10811-010-9503-0. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang JJH, Cheung PCK. +UVA treatment increases the degree of unsaturation in microalgae fatty and total carotenoid content in Nitzshica closerium (Bacillariophyceae) and Isochrysis zhangjiangensis (Crysophyceae). Food Chem. 2011;129(3):783–91. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang H, Hill RT, Zheng T, Hu X, Wang B. Effects of bacterial communities on biofuel-producing microalgae: stimulation, inhibition and harvesting. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2016;36(2):341–52. 10.3109/07388551.2014.961402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakase G, Eguchi M. Analysis of bacterial communities in Nannochloropsis sp. cultures used for larval fish production. Fish Sci. 2007;73:543–9. 10.1111/j.1444-2906.2007.01366.x. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Messina G, Manetti C, Amodeo D, Palma ID, Petri C, Nante N, et al. Efficacy of nearuv-a to inactive microbial growth. Eur J Public Health. 2021. 10.1093/eurpub/ckab165.475. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hold GL, Smith EA, Rappé MS, Maas EW, Moore ERB, Stroempl C, et al. Characterization of bacterial communities associated with toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates: Alexandrium spp. and Scrippsiellatrochoidea. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;37(2):161–73. 10.1016/S0168-6496(01)00157-X. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strömpl C, Hold GL, Lünsdorf H, Graham J, Gallacher S, Abraham WR, et al. Oceanicaulisalexandrii gen. nov., sp. Nov., a novel stalked bacterium isolated from a culture of the dinoflagellate Alexandriumtamarense (Lebour) Balech. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53(6):1901–6. 10.1099/ijs.0.02635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang X, Qi M, Li QH, Cui ZD, Yang Q. Maricaulisalexandrii sp. Nov., a novel active bioflocculants-bearing and dimorphic prosthecate bacterium isolated from marine phycosphere. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2021;114:1195–203. 10.1007/s10482-021-01588-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deng Y, Mauri M, Vallet M, Staudinger M, Allen R, Pohnert G. Dynamic diatom-bacteria consortia in synthetic plankton communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88(22):e0161922. 10.1128/aem.01619-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martinez-Mercado MA, Cembella AD, Sánchez-Castrejón E, Saavedra-Flores A, Galindo-Sánchez CE, Durán-Riveroll LM. Functional diversity of bacterial microbiota associated with the toxigenic benthic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(7):e0306108. 10.1371/journal.pone.0306108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alonso-Sáez L, Balagué V, Sà LEL, Sánchez O, González JM, Pinhassi J, et al. Seasonality in bacterial diversity in north-west Mediterranean coastal waters: assessment through clone libraries, fingerprinting and FISH. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;60(1):98–112. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wietz M, Gram L, Jørgensen B, Schramm A. Latitudinal patterns in the abundance of major marine bacterioplankton groups. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2010;61:179–89. 10.3354/ame01443. [Google Scholar]

- 93.D’Ambrosio L, Ziervogel K, MacGregor B, Teske A, Arnosti C. Composition and enzymatic function of particle-associated and free-living bacteria: a coastal/offshore comparison. ISME J. 2014;8(11):2167–79. 10.1038/ismej.2014.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Johansson ON, Pinder MIM, Ohlsson F, Egardt J, Töpel M, Clarke AK. Friends with benefits: exploring the phycosphere of the marine diatom Skeletonema marinoi. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1828. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hosseini H, Saadaoui I, Cherif M, Siddiqui SA, Sayadi S. Exploring the dynamics of algae-associated microbiome during the scale-up process of Tetraselmis sp. microalgae: a metagenomics approach. Bioresour Technol. 2024;393:129991. 10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yao S, Lyu S, An Y, Lu J, Gjermansen C, Schramm A. Microalgae-bacteria symbiosis in microalgal growth and biofuel production: a review. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;126(2):359–68. 10.1111/jam.14095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vacant S, Benites LF, Salmeron C, Intertaglia L, Norest M, Cadoudal A, et al. Long-term stability of bacterial associations in a microcosm of Ostreococcus tauri (Chlorophyta, Mamiellophyceae). Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:814386. 10.3389/fpls.2022.814386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen Y, Tang X, Kapoore RV, Xu C, Vaidyanathan S. Influence of nutrient status on the accumulation of biomass and lipid on Nannochloropsis salina and Dunaliella salina. Energy Convers Manag. 2015;106:61–72. 10.1016/j.enconman.2015.09.025. [Google Scholar]

- 99.ElBarmelgy A, Isamail MM, Sewilam H. Biomass productivity of Nannochloropsis sp. grown in desalination brine culture medium. Desalination Water Treat. 2021;216:306–14. 10.5004/dwt.2021.26848. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Borowitzka MA. Species and strain selection, algae for biofuels and energy. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. p. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aléman-Nava GS, Muylaert K, Bermudez SPC, Depraetere O, Rittmann B, Parra-Saldívar R, et al. Two-stage cultivation of Nannochloropsis oculata for lipid production using reversible alkaline flocculation. Bioresour Technol. 2017;226:18–23. 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.