Abstract

Postoperative infection prevention is crucial for cardiac surgery patients. This study enrolled 579 cardiac surgery patients from November 2021 to July 2022, reporting a 12.3% incidence of postoperative pneumonia. Blood sugar, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores, respiratory failure, and complications were linked to respiratory infections. Significant differences in biomarkers, including creatine kinase, urine volume, alanine transaminase (ALT), hemoglobin, and PaO2/FiO2, were observed between pneumonia types. Bacterial pneumonia cases showed positive correlations between ALT, urine volume, and infection, while hemoglobin and PaO2/FiO2 correlated negatively. The most common pathogens were Klebsiella pneumoniae (20.3%), Acinetobacter baumannii (11.6%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10.9%). Identifying susceptibility factors and pathogenic characteristics can guide effective prevention strategies. Monitoring and oxygen therapy remain essential for reducing postoperative pneumonia risk in cardiac surgery patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13019-025-03472-0.

Keywords: Postoperative infection, Cardiac surgery, Pneumonia, Susceptible factors, Prevention strategies

Introduction

Postoperative respiratory complications stand out as a critical concern for cardiac surgeons, with pneumonia emerging as the second most prevalent nosocomial infection after urinary tract infections. The incidence of postoperative pneumonia (POP) in patients undergoing cardiac surgery ranges between 10% and 20%, correlating closely with heightened morbidity, mortality, ICU admissions, and prolonged hospital stays [1, 2]. Moreover, POP substantially elevates the financial burden on patients [3]. Postoperative infections following cardiac surgery unfold rapidly, posing a severe risk of multi-organ failure and potentially life-threatening consequences [4].

Numerous factors have been identified in association with POP in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, with consistent predictors across various studies, including age, smoking history, surgical background, cardiac function, surgical procedure type, blood transfusions, and mechanical ventilation [5]. Research indicates that a twofold increase in the risk of POP exists for patients with type 2 diabetes compared to that of their non-diabetic counterparts [6]. Additionally, renal diseases have been recognized as an independent risk factor for POP following cardiac surgery [7]. Factors contributing to POP can be categorized as either non-modifiable, such as age and sex, or modifiable, encompassing variables like smoking, obesity, length of hospital stay, blood glucose levels, and atrial fibrillation [8].

Furthermore, infections arising following cardiac surgery predominantly involve gram-negative bacteria, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with gram-positive bacteria like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Streptococcus pneumoniae [9–11]. This study aims to comprehensively identify common susceptibility factors in patients undergoing cardiac surgery by scrutinizing the differences in clinical data between the POP and non-POP groups. Using one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA, and Pearson correlation analysis, and considering the characteristic microbial distribution in patients with pneumonia, the research provides valuable insights into the prevention, control, and development of monitoring protocols for POP.

Objectives

A total of 579 patients with a history of heart disease who were admitted to our Hospital Cardiothoracic Surgery Department from November 26, 2021, to July 28, 2022, were selected as the study population (Supplementary Fig. 1). Clinical data integrity was first verified, and 16 patients with missing results from LAMP respiratory tract testing (Boao classic microfluidic chip reagent kit), 21 with critical data missing, and 5 that were deceased were excluded. In total, 537 patients were included in the study, comprising 395 males and 142 females. The age of the participants ranged from 35 to 87 years, with an average of 66.1 (± 7.6) years. Among these patients, 66 met the criteria for “Pneumonia Diagnosis” (WS 382–2012) and were determined to have pneumonia by attending physicians, radiologists, and laboratory physicians. Additionally, samples of sputum, wound secretions, whole blood, urine, or locked punctures were collected for bacterial culture and LAMP joint testing.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years who underwent elective or emergency cardiac surgery (e.g., coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement/repair);

Patients who received open-chest or minimally invasive cardiac surgery;

No signs of active infection (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infection) prior to surgery;

Informed consent obtained prior to surgery, agreeing to participate in the study and for data usage;

Postoperative monitoring in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for at least 24 h.

Exclusion Criteria:

Presence of pneumonia or other active infections before surgery (e.g., sepsis, infective endocarditis);

Patients with severe immunosuppressive conditions (e.g., HIV/AIDS, long-term immunosuppressant use);

Patients with active malignancies or those undergoing anti-tumor therapy;

Patients who died intraoperatively or shortly after surgery, before completion of the observation period for postoperative pneumonia;

Incomplete clinical records or missing key data required for analysis;

Non-cardiac surgery patients or those who only underwent interventional procedures.

Research methods

Clinical data were obtained for the 537 enrolled patients. For non-categorical data with a missing proportion of less than 10%, multiple imputations were performed to complete the data. Clinical parameters were analyzed and compared between the pneumonia and non-pneumonia groups. Combining the results of bacterial culture and LAMP joint testing, the pneumonia group was further classified into non-bacterial, single-pathogen, double-pathogen, triple-pathogen, and multiple-pathogen infections. Risk factors were compared between bacterial and non-bacterial pneumonia subgroups within the pneumonia group, and comparisons were made within the bacterial pneumonia group. Correlation analysis was conducted to explore risk factors for pneumonia in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Statistical methods

SPSS 27.0 was used for data analysis. First, the Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to assess the normal distribution of the samples. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, independent sample t-tests were performed, while categorical data were analyzed using chi-square tests. For data that did not meet the normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. Additionally, single factor, binary logistic regression, and Pearson correlation analyses were used to identify risk factors for pneumonia in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Results

Univariate and multivariate analyses of cardiothoracic surgery POP and non-POP groups

For non-normally distributed variables, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was conducted, independent sample t-tests were performed for continuous variables, and chi-square tests were applied for categorical samples, with a two-tailed p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis of the pneumonia and non-pneumonia groups revealed no significant differences in age or sex. However, the mean height of the non-pneumonia group was significantly higher than that of the pneumonia group. Additionally, indicators such as blood glucose, ICU duration, hospital stay, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and lactate were significantly higher in the pneumonia group, while postoperative Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores were significantly lower compared to that of the non-pneumonia group (Supplementary Table 1). Chi-square analysis also indicated significantly higher incidences of kidney disease, heart disease (non-lethal cardiac arrest, heart failure, new-onset ventricular arrhythmia, and new-onset atrial fibrillation), respiratory failure, and complication rates in the pneumonia group compared to that of the non-pneumonia group (Supplementary Table 2). Binary logistic regression analysis of the obtained differential data suggested that the highest blood glucose level (> 12), respiratory failure, complications, and postoperative MoCA scores were significant risk factors for patients with pneumonia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Binary logistic regression analysis of susceptibility factors in cardiovascular surgery

| Factors | b | SE | Wald | OR Value | 95%CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

peak blood sugar level(uuit) > 12 |

1.831 | 0.833 | 4.835 | 6.239 | 1.220-31.907 | 0.028 |

|

MoCA on the 5th day post-operation ≥ 26 |

2.258 | 0.976 | 5.356 | 9.566 | 1.413–64.753 | 0.021 |

|

Respiratory failure Yes/No |

-3.062 | 0.935 | 10.722 | 0.047 | 0.007–0.293 | 0.001 |

|

Complication grading ≥ ClavienDindo IIb Yes/NO |

-7.965 | 1.197 | 44.285 | 1.913 | 0.295–12.422 | 2.84E-11 |

Bacterial morphological analysis in cardiothoracic surgery POP group

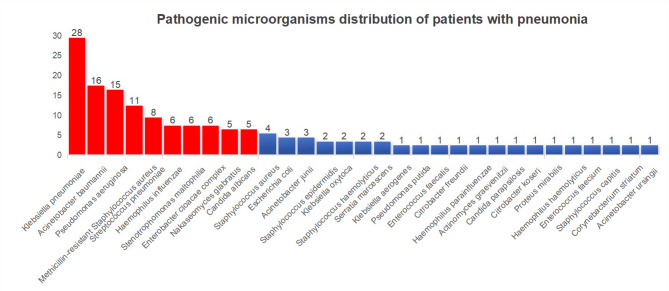

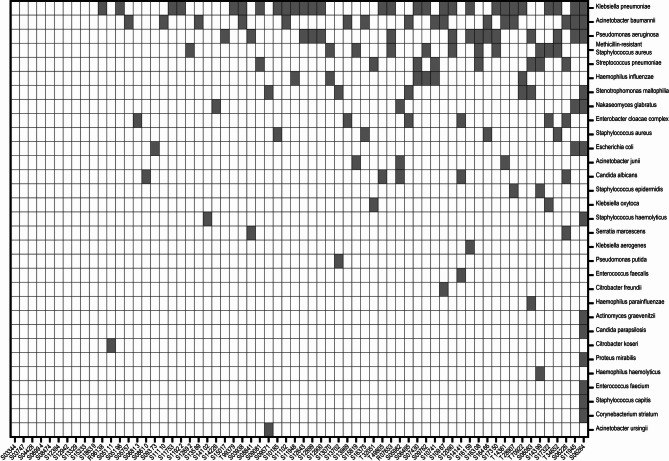

Using culture results combined with LAMP joint testing, pathogenic microorganisms in the pneumonia group were identified. After confirmation by attending and laboratory physicians, 138 bacterial strains were detected in patients with pneumonia. The top 10 ranked pathogens were gram-negative bacteria Klebsiella (20.3%, 28/138), Acinetobacter baumannii (11.6%, 16/138), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10.9%, 15/138), Haemophilus influenzae (4.3%, 6/138), Burkholderia cepacia (4.3%, 6/138), and Enterobacter cloacae complex (4.3%, 6/138); gram-positive bacteria included MRSA (8.0%, 11/138) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (5.8%, 8/138); fungi included smooth yeast (3.6%, 5/138) and white filamentous yeast (3.6%, 5/138) (Figs. 1 and 2). Among the 66 confirmed patients with pneumonia, 10 were classified as non-bacterial pneumonia, while the number of infections classified as single-, double-, triple-, or multiple-pathogen were 16, 17, 16, and 7, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of pathogenic microorganisms in postoperative infections among cardiac surgery patients

Fig. 2.

Heatmap of pathogenic microorganism distribution in 56 patients with postoperative pneumonia

Risk factor analysis between bacterial and non-bacterial pneumonia in the cardiothoracic surgery POP group

The 66 patients with pneumonia were further divided into 10 with non-bacterial pneumonia and 56 with bacterial pneumonia. Independent sample t-tests between the two groups revealed that patients with bacterial pneumonia had significantly higher levels of cardiac troponin, right SctO2, brain natriuretic peptide, postoperative MoCA scores, and MMSE scores compared to that of patients with non-bacterial pneumonia (Table 2). Patients with bacterial pneumonia were further categorized into single infection (infection with a single pathogen), double infection (infection with two pathogens), triple infection (infection with three pathogens), and multiple infection (pathogen count > 3). Single-factor ANOVA analysis and Pearson correlation analysis indicated weak positive correlations between cardiac troponin TnT and urine output in patients with bacterial pneumonia; however, these correlations were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Analysis of bacterial pneumonia and Non-Bacterial pneumonia in patients with pneumonia

| Group | Troponin (ug/L) |

Measurement of right SctO2 in the right frontal area (%) |

Brain Natriuretic Peptide (pg/Ml) |

MoCA at 30 Days Post-Operation | total score of the Mini-Mental State Examination (POD30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

bacterial pneumonia ( n = 56) |

0.67 (0.35 − 0.10) |

75.50 (74.05–76.95) |

127.23 (90.75–163.70) |

17.7 (16.3–19.1) |

21.7 (20.0-23.3) |

|

non-bacterial pneumonia ( n = 10) |

0.23 (0.11–0.34) |

70.30 (65.21–75.39) |

66.38 (39.44–93.32) |

14.1 (10.1–18.1) |

21.3 (17.5–25.1) |

| t | 2.645 | 2.658 | 2.798 | 2.016 | 2.093 |

| p | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.048 | 0.04 |

Risk factor analysis among patients with single, double, triple, and multiple infections in the cardiothoracic surgery POP group

To further clarify risk factors associated with bacterial infections in patients with pneumonia, single-factor ANOVA analysis and Pearson correlation analysis were performed among patients with single, double, triple, and multiple infections. Results showed weak positive correlations between liver function ALT and urine output and negative correlations between hemoglobin concentration and PaO2/FiO2 ratio. In addition, a significant negative correlation between the PaO2/FiO2 ratio and the number of infectious pathogens was observed (Table 3).

Table 3.

One-way ANOVA and pearson correlation analysis among groups of bacterial pneumonia

| Group | Alanine Aminotransferase | Urine volume | Minimum hemoglobin concentration | PaO2/FiO2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95%CI | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95%CI | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95%CI | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95%CI | |

|

single-pathogen infection ( n = 16) |

17.094 | 9.710 | 2.428 | 11.920-22.268 | 828.130 | 326.583 | 81.646 | 654.10-1002.15 | 10.850 | 1.846 | 0.462 | 9.866–11.834 | 284.229 | 117.389 | 29.347 | 221.676-346.781 |

|

double-pathogen infection ( n = 17) |

31.747 | 25.785 | 6.254 | 18.490-45.004 | 685.290 | 354.332 | 85.938 | 503.11-867.48 | 25.780 | 35.759 | 8.673 | 7.394–44.165 | 299.550 | 161.673 | 39.212 | 216.425-382.675 |

|

triple-pathogen infection ( n = 16) |

20.438 | 9.203 | 2.301 | 15.534–25.341 | 700.000 | 275.076 | 68.769 | 553.42-846.58 | 11.713 | 2.271 | 0.568 | 10.502–12.923 | 237.712 | 111.421 | 27.855 | 178.340-297.085 |

|

multiple-pathogen infection ( n = 7) |

23.400 | 16.045 | 6.065 | 8.561–38.239 | 1050.000 | 784.750 | 296.608 | 324.23-1775.77 | 12.257 | 2.686 | 1.015 | 9.773–14.741 | 332.286 | 91.400 | 34.546 | 247.755-416.816 |

| F Value | 2.286 | 3.696 | 2.894 | 2.991 | ||||||||||||

| p | 0.090 | 0.017 | 0.044 | 0.039 | ||||||||||||

| Pearson correlation | 0.057 | 0.100 | -0.154 | -0.331 | ||||||||||||

| p | 0.679 | 0.461 | 0.288 | 0.013 | ||||||||||||

Discussion

POP is the most common hospital-acquired infection following cardiothoracic surgery. In a study investigating risk factors for POP among 16,084 patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting, 17 preoperative factors were identified using multivariate analysis. Interestingly, body weight and sex indices did not significantly increase in patients with pneumonia, aligning with our findings. Demographic data suggested a potential correlation between age and pneumonia risk, but our data showed no significant age-related differences. The study also indicated associations between arrhythmia, blood glucose, liver function, lung function, and smoking status with POP occurrence [12]. Our study similarly identified arrhythmia and elevated blood glucose as significant risk factors for POP, highlighting their consistent relevance across patient populations. Arrhythmia may compromise cardiac output and pulmonary circulation, leading to impaired oxygen delivery and pulmonary congestion, which in turn increases susceptibility to infection [13]. Hyperglycemia, on the other hand, is known to impair neutrophil function and overall immune response, thereby facilitating bacterial growth and increasing the risk of postoperative infections, including pneumonia [14]. In a prospective study examining 1,963 patients for postoperative adverse reactions following cardiac surgery, the detection of blood glucose variability every four hours predicted postoperative complications such as pneumonia, infection, and even death. Elevated blood glucose levels may increase the risk of postoperative infections, highlighting the significance of glycemic control in reducing POP [15–18]. Consistent with our results from t-tests and multifactorial logistic analysis, blood glucose emerged as a potential risk factor for triggering POP infections.

Patients with respiratory failure often require mechanical ventilation assistance, and ventilator-associated pneumonia is closely linked to higher mortality, prolonged ICU stays, and extended hospitalization [19–22]. Thus, for patients with cardiothoracic surgery-related POP, differences may be evident in postoperative complication grading and cognitive function compared with those who were non-infected. Additionally, in the bacterial pneumonia group, a significant negative correlation was observed between PaO2/FiO2 parameters and the number of infecting pathogens. This may be linked to impaired oxygen delivery in the diseased state, coupled with heightened metabolism in the infectious state, leading to a cellular oxygen supply-demand imbalance that exacerbates inflammation or myocardial injury [23, 24]. In cardiothoracic surgery research, gram-negative bacterial infections are primarily dominated by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Escherichia coli. Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species, are also prevalent [25–27], consistent with the commonly identified pathogens in our study. In the comparison between bacterial and non-bacterial pneumonia in the pneumonia group and the subgroup analysis based on the number of infecting pathogens in the bacterial pneumonia group, we observed a weak positive correlation between urine output and the number of infecting pathogens. However, this correlation lacked statistical significance and may be related to increased fluid intake and the promotion of bacterial and inflammatory secretion excretion [28, 29]. Wang [30] et al. found that high-flow oxygen humidification could shift the PaO2/FiO2 index and reduce the ICU stay time after cardiac surgery. Atelectasis and pleural effusions commonly develop following cardiothoracic surgery, leading to pulmonary complications or respiratory failure. A high-flow nasal cannula or conventional oxygen therapy is an effective treatment for preventing pulmonary complications or respiratory failure [31]. While oxygen therapy is a necessary treatment element for post-cardiac operative care [32]. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy could effectively prevent sternal infection and osteomyelitis after cardiothoracic surgery [33]. Hemoglobin is essential for maintaining tissue oxygen supply, so low levels can impair oxygen delivery, potentially causing organ dysfunction or even failure. As an important supplement therapy against infection, oxygen therapy could induce the reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill bacterium or pathogens directly, regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines, or activate the neutrophils for antibacterial [34].

Therefore, we believe that postoperative monitoring of newly developed cardiac conditions and prevention of related complications should be closely managed. Postoperative MoCA assessments should be conducted, as higher MoCA scores can often predict the occurrence of infections early. Additionally, encouraging and supervising patients to actively engage in oxygen therapy can help prevent the onset of postoperative pneumonia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery face a higher risk of hospital-acquired postoperative pneumonia. Postoperative monitoring and oxygen therapy are effective measures for preventing the occurrence of postoperative pneumonia in cardiac surgery patients. Meantime, rational and scientific treatment plans, based on the microbial characteristics of these patients, should be implemented to maximize the prevention of POP occurrence.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Zhigang Guo conceived and designed the study. Jie Li diagnosed the patients and collected the data. Chang Xie analyzed the data and plotted figures. Zhenhua Wu wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Tianjin Science and Technology Project (Grant No.20JCZDJC00810).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Chest Hospital on December 2, 2023, and all participants gave written informed consent. All procedures were performed following the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jie Li, Zhenhua Wu, Chang Xie these authors contributed equally to this work listed as co-first author.

References

- 1.Tanner TG, Colvin MO. Pulmonary complications of cardiac surgery. Lung2020;198(6):889– 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Wang D-S, Huang X-F, Wang H-F, Le S, Du X-L. Clinical risk score for postoperative pneumonia following heart valve surgery. Chin Med J. 2021;134(20):2447–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D, Huang X, Wang H, Le S, Yang H, Wang F, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia after cardiac surgery: a prediction model. J Thorac Disease. 2021;13(4):2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alghamdi BA, Alharthi RA, AlShaikh BA, Alosaimi MA, Alghamdi AY, Yusnoraini N et al. Risk Factors for Post-cardiac Surgery Infections. Cureus2022;14(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wang D, Lu Y, Sun M, Huang X, Du X, Jiao Z, et al. Pneumonia after cardiovascular surgery: incidence, risk factors and interventions. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:911878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma C-m, Liu Q, Li M-l, Ji M-j, Zhang J-d, Zhang B-. h The effects of type 2 diabetes and postoperative pneumonia on the mortality in inpatients with surgery. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy2019:2507-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Wang D, Chen X, Wu J, Le S, Xie F, Li X, et al. Development and validation of nomogram models for postoperative pneumonia in adult patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:750828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen B, Lu Y, Huang X, Du X, Sun F, Xie F et al. Influence and risk factors of postoperative infection after surgery for ischemic cardiomyopathy. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine2023;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vesteinsdottir E, Helgason KO, Sverrisson KO, Gudlaugsson O, Karason S. Infections and outcomes after cardiac surgery—The impact of outbreaks traced to transesophageal echocardiography probes. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2019;63(7):871–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riahi G, Koohsari E, Hosseini SS. Fungal and bacterial co-infection in the superficial and deep sternal wound after open cardiac surgery. Iran J Microbiol. 2023;15(3):392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma J-G, An J-X. Deep sternal wound infection after cardiac surgery: a comparison of three different wound infection types and an analysis of antibiotic resistance. J Thorac Disease. 2018;10(1):377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.<14.A. pre-operative risk model for post-operative pneumonia following coronary atery bypass grafting.pdf>.

- 13.Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Böttiger. BW Post–Cardiac Arrest Syndrome. Circulation2008;118(23):2452-83.

- 14.Berbudi A, Rahmadika N, Tjahjadi AI, Ruslami R. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16(5):442–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rangasamy V, Xu X, Susheela AT, Subramaniam B. Comparison of glycemic variability indices: blood glucose, risk index, and coefficient of variation in predicting adverse outcomes for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(7):1794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong X, Chen D, Cai S, Qiu L, Shi J. Association of intraoperative hyperglycemia with postoperative composite infection after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: A retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine2022;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Wang Y-y, Hu S-f, Ying H-m, Chen L, Li H-l, Tian F, et al. Postoperative tight glycemic control significantly reduces postoperative infection rates in patients undergoing surgery: a meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disorders. 2018;18(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moorthy V, Sim MA, Liu W, Chew STH, Ti LK. Risk factors and impact of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients after cardiac surgery: A prospective study. Medicine2019;98(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hassoun-Kheir N, Hussein K, Abboud Z, Raderman Y, Abu-Hanna L, Darawshe A, et al. Risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia following cardiac surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(3):546–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M, Xu X, Wu S, Sun H, Chang Y, Li M, et al. Risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia due to multi-drug resistant organisms after cardiac surgery in adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nam K, Park J-B, Park WB, Kim NJ, Cho Y, Jang HS, et al. Effect of perioperative subglottic secretion drainage on ventilator-associated pneumonia after cardiac surgery: a retrospective, before-and-after study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35(8):2377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metersky ML, Wang Y, Klompas M, Eckenrode S, Mathew J, Krumholz HM. Temporal trends in postoperative and ventilator-associated pneumonia in the united States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023;44(8):1247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinellu A, De Vito A, Scano V, Paliogiannis P, Fiore V, Madeddu G, et al. The PaO2/FiO2ratio on admission is independently associated with prolonged hospitalization in COVID-19 patients. J Infect Developing Ctries. 2021;15(3):353–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thongbuaban S. Association between corticosteroids and improvement of PaO2/FiO2 in adults with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Acad. 2022;46(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massart N, Mansour A, Ross JT, Piau C, Verhoye J-P, Tattevin P, et al. Mortality due to hospital-acquired infection after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;163(6):2131–40. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandström N, Söderquist B, Wistrand C, Friberg Ö. The presence of skin bacteria in the sternal wound and contamination of implantation materials during cardiac surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2023;135:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zardi EM, Chello M, Zardi DM, Barbato R, Giacinto O, Mastroianni C, et al. Nosocomial extracardiac infections after cardiac surgery. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2022;24(11):159–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guppy MP, Mickan SM, Del Mar CB, Thorning S, Rack A. Advising patients to increase fluid intake for treating acute respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews2011(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Xu Q-L, Li H, Zhu Y-J, Xu G. The treatments and postoperative complications of esophageal cancer: a review. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery2020;15:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Wang F, Xiao M, Huang Y, Wen Z, Fan D, Liu J. Effect of nasal high-flow oxygen humidification on patients after cardiac surgery. Heliyon2023;9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang Y, Huang D, Ni Y, Liang Z. High-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy for postcardiothoracic surgery. Respir Care. 2020;65(11):1730–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu C, Lin Q, Li D. High-flow nasal cannula therapy versus conventional oxygen therapy for adult patients after cardiac surgery: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 2024;66:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu W-K, Chen Y-W, Shie H-G, Lien T-C, Kao H-K, Wang J-H. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an adjunctive treatment for sternal infection and osteomyelitis after sternotomy and cardiothoracic surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou D, Fu D, Yan L, Xie L. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of surgical site infections: a narrative review. Medicina. 2023;59(4):762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.