Abstract

Background

To investigate the effects of increased weight-loading on body weight, body composition, fat mass distribution, physical activity and energy balance in individuals with obesity.

Methods

This single-centre non-blinded randomised controlled trial was conducted from August 1, 2021, through February 28, 2022. Adults with obesity class 1 (body mass index, BMI 30–35 kg/m2) were assigned to wear either a heavy (high load; 11% of body weight, n = 28) or light (low load; 1% of body weight, n = 30) weight vest for 8 h per day over 5 weeks.

Results

High-load treatment reduced fat mass (mean difference − 2.60%; 95% CI − 3.79, − 1.41) and increased lean mass (mean difference 1.40%; 95% CI 0.37, 2.42), with no significant effect on body weight. Fat mass reductions were primarily observed in weight-loaded regions but not in the non-weight-bearing regions such as the arms. Waist circumference decreased (mean difference − 2.26%; 95% CI − 3.81, − 0.71) in the high-load group compared to the low-load group. Despite these beneficial changes, sedentary time was higher in the high-load group (mean difference 4.69%; 95% CI 0.98, 8.39) compared to the low-load group, while energy expenditure and energy intake remained unchanged.

Conclusions

Increased weight-loading reduced fat mass and increased lean mass, resulting in a healthier body composition. These effects were achieved despite no increase in physical activity. The fat mass-reducing effect was primarily seen in weight-loaded regions, implying local adaptation to the increased loading.

Trial registration

Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04697238) in 2021.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04143-6.

Keywords: Obesity, Weight-bearing, Weight-loading, Standing position, Body composition, Fat mass distribution, Energy balance

Background

Obesity is a serious public health issue that increases the risk of various chronic diseases and lowers quality of life [1–4]. In recent years, there have been significant advances of incretin-based pharmacotherapies showing promising results as anti-obesity treatments. However, while they effectively reduce fat mass, they are often associated with an undesirable loss of muscle mass [5, 6]. Such a loss of muscle mass could be especially problematic in patients with sarcopenic obesity [7–9]. The regulation of fat mass still remains elusive [10]. Fat mass is determined by the long-term balance between energy intake and expenditure, which is regulated by genetic, environmental, behavioural and hormonal factors [11]. The distribution of fat, rather than fat mass alone, plays a critical role in metabolic health. Ectopic fat accumulation, such as intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT), visceral adipose tissue (VAT), and liver fat, is closely linked to metabolic disorders, while subcutaneous fat is considered less harmful [12–17]. However, it remains unclear how lifestyle interventions, such as increased standing or weight-loading, influence fat mass and its distribution in humans.

An emerging field of research explores how health outcomes are influenced by exercise and posture allocation. It has been demonstrated that increased time spent standing is associated with improved health including reduced waist circumference, improved insulin sensitivity as well as reduced risk of developing obesity [18–22]. Standing modestly increases energy expenditure and may also raise cardiac workload due to the upright posture, potentially triggering systemic cardiovascular adaptations [23, 24]. However, the metabolic benefits of standing may partly derive from the light physical activity often accompanying it, making it difficult to separate the effects of standing itself from those of increased movement. While some evidence suggests that standing contributes to metabolic health, it is generally agreed that increased physical activity plays a more critical role [25, 26]. Any causal relationships between standing time and fat mass or its distribution are yet to be elucidated, and the evidence regarding the effect of time spent standing on metabolic health is inconclusive [27].

Standing increases weight-bearing on the back and lower limbs, which could have physiological effects beyond posture. Furthermore, increased weight-loading has been reported to reduce fat mass without affecting lean mass in rodents [28, 29]. Mechanistic studies suggest that osteocytes in weight-bearing bones can sense weight-loading and influence fat mass regulation [28, 29]. In addition, data from a number of mouse models, targeting certain genes in osteoblast-lineage cells, have suggested that the skeleton may exert effects on fat mass and energy metabolism [30, 31].

In a previous short-term clinical study, we observed that increased weight-loading, by wearing weight vests for 3 weeks, reduced fat mass without any significant effect on non-fat mass [32]. However, the specific types of adipose tissue influenced by increased weight-loading, and the underlying mechanisms driving these changes remain unclear. The aims of the present 5-week study were to determine the effects of increased weight-loading on body weight, body composition, fat mass distribution, physical activity and energy balance in individuals with obesity. We hypothesised that increased weight-loading would lead to reductions in body weight, fat mass and waist circumference, along with an increase in lean mass.

Methods

Study design

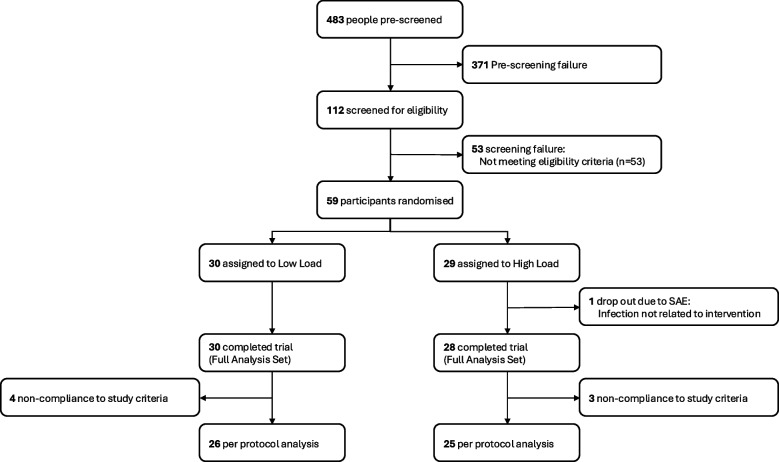

This was a single-centre clinical randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigating the effect of increased weight-loading, through application of weight vests, on body weight in individuals with obesity. The trial was conducted at Gothia Forum, Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden. This trial adheres to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines. A CONSORT flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1, and a CONSORT checklist is provided in Additional file 1.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram describing enrolment and study flow. The participants with screening failure did not meet all the inclusion criteria and/or did meet at least one of the exclusion criteria. SAE, severe adverse event

The trial was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (registration number 2021–00095) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines (ICH) for Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Anti-obesity Treatment by Loading in Adult Subjects (ATLAS), NCT04697238). An independent monitor oversaw the trial according to ICH-GCP guidelines. The monitor had access to all the data and performed monitoring visits on site before, during and after data collection.

Participants

Eligible participants were adults (aged 18–65 years) with obesity defined as body mass index (BMI) of 30–35 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included chronic disease that could interfere with study participation such as diabetes (type 1 or type 2) or cardiovascular disease, previous bariatric-metabolic surgery, reduced mobility and chronic pain. Full lists of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the study protocol (Additional file 2). Data regarding gender (male, female or other) were self-reported at screening. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants before enrolment in the trial.

Randomisation and masking

A total of 483 people were pre-screened in a phone interview, of which 112 were screened for eligibility. Fifty-nine participants were eligible according to the eligibility criteria and randomised in a 1:1 ratio to 5 weeks treatment with either a heavy weight vest (= high-load group, 11% of participant’s body weight) or a light weight vest (= low-load group, 1% of participant’s body weight). Randomisation was performed through permuted blocks (stratified by age 18–50 years, age 51–65 years and gender) using a built-in function in the electronic case report form (eCRF) software (MediCase eCRF version 5, MediCase AB, Gothenburg, Sweden). The study was not blinded to the participants or study personnel because of the difficulty to conceal differences in weight between treatments (heavy and light weight vest).

Procedures

The trial design is illustrated in Fig. 2. Each participant participated in the trial for approximately 10 weeks, and it involved 13 visits. Overall, the trial consisted of three phases: (1) Weeks 1–3—Baseline measurements, (2) Weeks 4–8—Randomisation and intervention, (3) Weeks 9–10—Follow-up post-treatment. Details about each study visit and its procedures are shown in the study protocol (Additional file 2). Adverse events were recorded at all study visits and when spontaneously reported by the participant, from the time of signing the informed consent form until completion of the study. The main endpoints were evaluated before (day 0) and after intervention (day 35), but some mechanistic endpoints (e.g. physical activity, energy expenditure and energy intake) were measured during the intervention (Fig. 2; for further detail see Additional file 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic timeline showing key moments of the trial. Screening performed on day -21. Baseline measurements obtained between day -21 and day 0 (Measurement 1). Measurement 1 included 14-day DLW measurement (day -14), 7-day accelerometer measurement (day -13), DXA and CT scans along with SDQ on day 0. Randomisation on day 0 and treatment with either low load or high load between day 0 and day 35. Second measurement period (Measurement 2) performed between day 14 and day 35. Measurement 2 included 14-day DLW measurement (day 14), 7-day accelerometer measurement (day 15), SDQ (day 28) along with DXA and CT scans on day 35. Follow-up visit on day 49, 2 weeks after the end of treatment. Figure created in BioRender; Bellman, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y79d008. CT, computed tomography; DLW, doubly labelled water; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; SDQ, Short Dietary Questionnaire

Intervention

Eligible participants were randomised at study visit 6 (day 0) into 5-week treatment with low or heavy weight-loading. The heavy loading (high load) consisted of a weight vest with a weight corresponding to 11% of the subject’s body weight (PRF Weight vest, Casall, Norrköping, Sweden) and the low loading (low load) consisted of a weight vest (PRF Weight vest, Casall, Norrköping, Sweden) of identical appearance, but with a weight corresponding to 1% of the subject’s body weight. Each vest was individually loaded with small weight bags (400–600 g each; Casall, Norrköping, Sweden) to reach approximately 1% or 11% of the participant’s body weight. The final weight of each vest was verified using a calibrated scale (seca 704; seca GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) before distribution, with a maximum error margin of ± 0.2 kg.

The 11% and 1% of body weight were chosen to create a 10% difference between the treatment groups, based on a protocol used in a previous 3-week clinical study [32]. Participants were instructed to carry the weight vests for 8 h per day for 5 weeks and to be in the standing position as much as possible during the carrying hours, but at a minimum 2 h per day. Outside of these instructions related to vest use and time spent standing, participants were instructed to maintain their usual lifestyle and daily routines. The participant recorded daily the time using the weight vest and the time using the vest standing. Compliance to wearing the weight vest was evaluated using the participant’s written recordings.

Measurements

Body composition parameters (Fig. 2)

Body weight (kilograms [kg]) was measured using a calibrated body weight scale (seca scales 704, seca, Hamburg, Germany). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Lunar iDXA, enCORE version 16, SP 1, GE Healthcare, Illinois, USA) was used to determine fat mass (kg), lean mass (kg) and bone mineral content (BMC; kg). Computed tomography (CT) scans (Somatom Force, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Munich, Germany) of the liver and abdomen were conducted to evaluate liver fat (Hounsfield Units [HU]), visceral adipose tissue (VAT; cm3) and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT; cm3) according to a specific study protocol (Additional file 3: Supplementary methods) [33, 34]. DXA and CT scans were performed on day 0 and day 35. Waist circumference (cm) was measured with a measuring tape.

Energy balance (Fig. 2)

Energy expenditure (EE; joules per day) was measured using the Doubly Labelled Water (DLW) method over two separate 14-day measurement periods on days -14 and 14. The measurements was conducted following the standard operating procedure from Maastricht University (Maastricht, Netherlands; Additional file 3: Supplementary methods) [35, 36]. Daily energy intake (joules per day) was estimated using the validated food questionnaire “Short Dietary Questionnaire” (SDQ) [37], which participants completed on days 0 and 28. The SDQ estimated the energy intake for the previous 2 weeks at each time point.

Physical activity (Fig. 2)

Physical activity (PA) was measured on two 7-day periods starting on days -13 and 15. Participants were instructed to wear the tri-axial accelerometers (Axivity AX3, Axivity Ltd., Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) over the hip for seven consecutive days during the whole day (24 h). Physical activity was categorised into different intensity levels based on metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs) thresholds: sedentary (< 1.5 METs), light PA (LPA; 1.5–2.9), moderate PA (MPA; 3.0–5.9), vigorous PA (VPA; 6.0–8.9) and very vigorous PA (VVPA; ≥ 9.0). Moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) was calculated as the sum of MPA, VPA and VVPA. The method is described in more detail in Additional file 3: Supplementary methods [38–40].

Metabolic blood parameters (Fig. 2)

Blood samples were taken to analyse metabolic markers using defined routines and certified assays or at the certified Clinical Chemistry lab at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Gothenburg, Sweden) using standardised procedures with the Alinity analysis platform (Abbott, Illinois, USA). The supplementary methods provide more information about all the measurements and methods (Additional file 3).

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the percentage change in body weight from randomisation (day 0) to the end of the intervention (day 35) 5 weeks later (Fig. 2). Key secondary endpoints included percentage change from baseline to the end of intervention in waist circumference, body fat percentage, body fat mass, body lean mass, regional fat mass, abdominal adipose tissue (VAT and SAT), liver fat, energy expenditure, energy intake and physical activity levels. All the secondary endpoints were also analysed as absolute changes. All endpoints in this study were compared between the high-load group and the low-load group. Details on all measurements can be found in the provided study protocol (Additional file 2).

Statistical analysis

Power calculations determined that 25 evaluable participants per group were required to detect a significant effect size of 1.6% difference in relative body weight change between groups from baseline to 5 weeks (primary endpoint), with a power of 80%. The effect size for the sample size calculation was based on results from a previous clinical study that estimated the effect of a 3-week treatment with weight vest on body weight (Additional file 3: Supplementary methods) [32]. The difference between the treatment groups for all parameters were tested by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with relative change from baseline to 5 weeks as the dependent variable, treatment group as fixed effect and age, sex, baseline BMI, vest exposure (h/day) and standing% when using the weight vest (= vest time standing/total vest time × 100) as covariates. From these ANCOVA models adjusted for covariates, estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented. The p-values given for the within-group comparison (5 weeks vs baseline) of the different parameters were calculated using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The statistical analyses were performed according to a statistical analysis plan developed before study start, and data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) or GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Study participants

A total of 59 participants were randomised to treatment with low-load (n = 30) or high-load (n = 29) vests, of which all 30 participants in the low-load group and 28/29 participants in the high-load group completed the trial (= full analysis set [FAS]; Fig. 1). The drop out participant in the high-load group was due to a severe adverse event (infection not related to treatment; Additional file 3: Table S6). Seven participants were excluded from the per-protocol (PP) analysis due to not following the study protocol with regard to vest exposure or not making any lifestyle changes, resulting in 26 participants in the low-load group and 25 participants in the high-load group (Fig. 1). In general, the findings from the full analysis set (presented in Additional file 3: Tables S1 and S2) and the per-protocol analysis (presented in main tables) were very similar. Characteristics of participants at baseline were similar in the two treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and treatment exposure

| Characteristics |

Low load (n = 30) |

High load (n = 28) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.7 ± 10.9 | 42.6 ± 10.0 | NS |

| Sex, females (%) | 15 (50%) | 15 (54%) | NS |

| Height (cm) | 176.0 ± 10.0 | 172.7 ± 8.4 | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 100.8 ± 11.5 | 98.4 ± 10.1 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.5 ± 1.7 | 32.9 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 110.0 ± 7.6 | 110.0 ± 6.9 | NS |

| DXA scan | |||

| Fat percent (%) | 39.2 ± 5.7 | 40.3 ± 5.8 | NS |

| Fat mass (kg) | 39.1 ± 5.3 | 39.4 ± 5.7 | NS |

| Lean mass (kg) | 58.5 ± 10.6 | 55.9 ± 9.2 | NS |

| BMC (kg) | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | NS |

| CT scan | |||

| Abdominal visceral fat (cm3) | 68.8 ± 37.7 | 63.6 ± 24.8 | NS |

| Abdominal Subcutaneous fat (cm3) | 187.9 ± 43.7 | 200.3 ± 39.9 | NS |

| Liver fat (HU) | 61.4 ± 10.1 | 58.2 ± 11.0 | NS |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Systolic (mmHg) | 123.8 ± 10.3 | 122.7 ± 10.3 | NS |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 73.9 ± 8.6 | 71.5 ± 9.6 | NS |

| Plasma/serum markers | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | NS |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | NS |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | NS |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Glycerol (μmol/L) | 64.4 ± 27.1 | 65.3 ± 49.5 | NS |

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | NS |

| Insulin (mIU/L) | 11.1 ± 8.2 | 10.5 ± 4.7 | NS |

| HOMA-IR | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | NS |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 33.2 ± 21.7 | 32.2 ± 16.9 | NS |

| Physical activity | |||

| Mean daily activity (mg) | 24.7 ± 8.3 | 23.9 ± 6.4 | NS |

| Sedentary time (minutes/day) | 728.7 ± 59.1 | 725.4 ± 61.1 | NS |

| LPA (minutes/day) | 101.1 ± 29.1 | 106.0 ± 25.3 | NS |

| MVPA (minutes/day) | 68.8 ± 25.3 | 67.3 ± 23.1 | NS |

| Energy balance | |||

| Energy expenditure (MJ/day) | 12.8 ± 1.9 | 12.2 ± 2.0 | NS |

| Energy intake (MJ/day) | 9.1 ± 4.0 | 7.4 ± 1.9 | NS |

| Treatment exposure | |||

| Vest exposure (hrs/day) | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 9.7 ± 1.1 | NS |

| Standing time (hrs/day) | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | NS |

| Standing (%) | 48.7 ± 1.8 | 46.7 ± 1.6 | NS |

Values are given as mean ± SD or n (%) for all randomised subjects. For comparisons between groups, Fisher’s exact test was used for dichotomous variables, t-test was used for normally distributed continuous parameters, and Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed parameters

BMC bone mineral content, BMI body mass index, CT computed tomography, DXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, HDL high-density lipoprotein, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, HU Hounsfield unit, LDL low-density lipoprotein, LPA light physical activity, Mg milli-g (acceleration), MJ megajoules, MVPA moderate-vigorous physical activity, NS non-significant, Standing (%), proportion of hours standing out of the hours with vest exposure

Effects of high-load treatment on body composition

High-load treatment for 5 weeks reduced fat mass (mean difference − 2.60%; 95% CI − 3.79, − 1.41) and increased lean mass (mean difference 1.40%; 95% CI 0.37, 2.42) compared to the low-load group, with no significant effect on body weight (mean difference − 0.21%; 95% CI − 0.92, 0.50; Fig. 3, Additional file 3: Table S3). Analysis of the absolute changes in body composition demonstrated that fat mass was 1.03 kg lower (95% CI − 1.48, − 0.58) and lean mass was 0.71 kg higher (95% CI 0.10, 1.31) in the high-load group compared to the low-load group (Table 2). No effect was observed on total body bone mineral content (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Change in body weight (BW), fat mass, lean mass and bone mineral content (BMC) at 5 weeks vs. baseline for all participants who completed the trial according to protocol. Participants treated with light weight vest (low load; n = 26) or heavy weight vest (high load, n = 25). Body composition and BMC measured with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Results are presented as estimated marginal means with error bars showing 95% confidence intervals. The between-group P-values (high load vs low load) are calculated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for age, sex, baseline body mass index (BMI), vest exposure (h) and standing % with vest. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001

Table 2.

Analyses of the absolute changes in the main secondary endpoints for all participants eligible for per-protocol analysis

|

Low load (n = 26) |

High load (n = 25) |

Difference between groups | P-value (ANCOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics | ||||

| Body weight (kg) | 0.25 (− 0.24, 0.73) | − 0.0005 (− 0.50, 0.50) | − 0.25 (− 0.95, 0.46) | 0.482 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.4 (− 0.8, 1.6) | − 2.0 (− 3.2, − 0.8) ** | − 2.4 (− 4.2, − 0.7) | 0.006 |

| DXA scan | ||||

| Fat percent (%) | 0.35 (0.12, 0.59) * | − 0.66 (− 0.81, − 0.33) *** | − 0.9 (− 1.3, − 0.6) | 2.3E-6 |

| Fat mass (g) | 526.8 (213.4, 840.2) ** | − 500.8 (− 820.5, − 181.1) ** | − 1027.6 (− 1479.9, − 575.3) | 3.8E-5 |

| Lean mass (g) | − 119.4 (− 538.3, 299.5) | 588.8 (161.4, 1016.1) ** | 708.2 (103.7, 1312.7) | 0.023 |

| BMC (g) | 3.3 (− 5.9, 12.5) | − 0.6 (− 10.0, 8.8) | − 3.9 (− 17.1, 9.4) | 0.562 |

| CT scan | ||||

| VAT (cm3) | − 2.84 (− 5.50, − 0.19) | 0.04 (− 2.67, 2.75) | 2.88 (− 0.95, 6.72) | 0.136 |

| SAT (cm3) | − 0.84 (− 4.19, 2.50) | − 3.67 (− 7.09, − 0.26) | − 2.83 (− 7.66, 1.99) | 0.243 |

| Liver fat (HU) | 0.16 (− 1.23, 1.54) | 1.51 (0.09, 2.92) * | 1.35 (− 0.65, 3.35) | 0.180 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Mean daily activity (mg) | 0.76 (− 1.91, 3.43) | − 1.81 (− 4.54, 0.91) | − 2.57 (− 6.43, 1.28) | 0.185 |

| Sedentary time (minutes/day) | − 25.77 (− 44.34, − 7.20) ** | 6.76 (− 12.18, 25.71) | 32.53 (5.74, 59.33) | 0.018 |

| LPA (minutes/day) | 10.37 (1.26, 19.48) ** | 5.05 (− 4.24, 14.34) | − 5.32 (− 18.46, 7.83) | 0.419 |

| MVPA (minutes/day) | 1.71 (− 7.64, 11.06) | − 7.31 (− 16.85, 2.23) | − 9.02 (− 22.52, 4.47) | 0.185 |

| Energy balance | ||||

| Energy expenditure (MJ/day) | − 0.09 (− 0.47, 0.29) | − 0.23 (− 0.61, 0.16) | − 0.14 (− 0.68, 0.41) | 0.615 |

| Energy intake (MJ/day) | 0.10 (− 0.81, 1.00) | − 0.18 (− 1.10, 0.74) | − 0.28 (− 1.58, 1.03) | 0.672 |

Results are presented as estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals for all participants. The between-group p-values (high load vs low load) given within the table are calculated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI, vest exposure (h) and standing % with vest. Within-group comparisons (5 weeks vs baseline) were made using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Statistically significant differences are highlighted in bold. BMC bone mineral content, BMI body mass index, CT computed tomography, DXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, HU Hounsfield unit, Liver fat estimated as liver attenuation, LPA light physical activity, Mg milli-g (acceleration), MJ megajoules, MVPA moderate to vigorous physical activity, SAT subcutaneous adipose tissue in the abdominal region, VAT visceral adipose tissue in the abdominal region

Analysis of fat mass distribution revealed significant reductions in fat mass in weight-bearing regions, including the legs, trunk, android and the gynoid regions, in the high-load group compared to the low-load group; but no change was observed in the non-weight-bearing regions of the arms (Fig. 4; Additional file 3: Table S4). In addition, waist circumference was reduced by 2.3% (95% CI − 3.81, − 0.71) or 2.44 cm (95% CI − 4.16, − 0.72) in the high-load group compared to the low-load group (Table 2; Additional file 3: Table S3).

Fig. 4.

Percentage change in different regions fat mass at 5 weeks vs. baseline for all participants who completed the trial according to protocol. Participants treated with light weight vest (low load; n = 26) or heavy weight vest (high load, n = 25). Body composition measured with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Results are presented as estimated marginal means with error bars showing 95% confidence intervals. The between-group P-values (high load vs low load) are calculated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusted for age, sex, baseline body mass index (BMI), vest exposure (h) and standing % with vest. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Statistical analyses demonstrated that there was no interaction effect from ANCOVA regarding gender for increased loading on body weight, fat mass, lean mass or waist circumference (P > 0.05 for the gender interaction terms).

Abdominal CT analysis did not identify any statistically significant between-treatment group differences for abdominal subcutaneous fat, visceral fat or liver fat. Within-group analyses revealed that the high-load treatment, but not low-load treatment, increased liver attenuation with 1.5 Hounsfield units (95% CI 0.09, 2.92; Table 2) indicating less liver steatosis.

Effects of high-load treatment on physical activity, energy balance and metabolic markers

Mechanistic analyses using tri-axial accelerometers revealed that the high-load group slightly increased their sedentary time during the treatment (non-significant), while the low-load group decreased theirs. This resulted in a significant difference of 4.7% (95% CI 0.98, 8.39; P = 0.014) or 32.5 min per day (95% CI 5.7, 59.3; P = 0.018) between groups (Table 2; Additional file 3: Table S3). No significant differences between the treatment groups were observed for energy expenditure, as measured using doubly labelled water, or energy intake (Table 2; Additional file 3: Table S3). Exploratory analyses of metabolic markers in serum and plasma did not reveal any treatment-related differences in total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glycerol, glucose, insulin, leptin or calculated HOMA-IR index (Additional file 3: Table S5).

Adverse events and safety

No treatment-related serious adverse event was reported during the study. The high-load group had in total 29 treatment-related adverse events compared to 6 in the low-load group (P < 0.001; Additional file 3: Table S6). Most treatment-related adverse events were musculoskeletal of which none led to discontinuation of any participant from the study. Additionally, the frequency of acute upper respiratory infections was higher in the high-load group compared to the low-load group (Additional file 3: Table S6). All adverse events, medical history and concomitant medications are presented in the supplementary materials (Additional file 3: Table S6, Table S7, Table S8).

Discussion

Herein, we demonstrate that 5 weeks of treatment with increased weight-loading, applied by weight vests, reduced fat mass and waist circumference while increasing lean mass, this without significant effect on body weight. The high-load treatment led to a healthier body composition with reduced fat mass and an increase in total body lean mass. These beneficial effects occurred despite an increase in sedentary time in the high-load group compared to the low-load group, and in the absence of significant effects on total body energy balance.

An important finding in the present study is that the high-load treatment reduced abdominal fat mass, as demonstrated by the decreased fat mass in the trunk region, determined by DXA, and supported by the associated 2.4 cm reduction in waist circumference. There is compelling evidence that reductions of the truncal fat mass and waist circumference are associated with lower morbidity and mortality rates [16, 41], strongly suggesting that the high-load treatment in the present trial improved metabolic health. The abdominal CT analyses revealed that the high-load group, but not the low-load group, showed increased liver attenuation, suggesting that weight-loading may reduce liver steatosis. However, this observation was not accompanied by a statistically significant between-group difference for liver fat, highlighting the need for confirmation in independent studies. Similarly, abdominal CT analyses did not identify any statistically significant between-group differences for VAT or SAT volumes. The discrepancy between the lack of effect on abdominal adipose tissue volumes as determined by CT and the reductions observed in truncal fat by DXA and waist circumference may be due to differences in the anatomical regions assessed by these methods. The relatively small volumes measured with CT at a single abdominal level (L3–L4) may increase the likelihood of missing significant changes in overall abdominal adipose tissue. In contrast, DXA provides a more comprehensive assessment of total trunk fat mass, offering a broader view of regional fat changes. Furthermore, CT scans measured only VAT and SAT, whereas DXA assessed total trunk fat mass without differentiating between fat types [42]. While the reduction in waist circumference likely reflects a loss of subcutaneous fat (albeit not significantly different between groups), it is possible that changes in smaller fat depots not captured by CT, such as IMAT, may also have contributed to the differences observed between DXA and CT. However, no definitive explanation can be provided based on the available data, and this warrants further investigation.

In the present study, the physical activity and sedentary time were determined using thorough and validated tri-axial accelerometers [38, 43, 44]. Sedentary time increased by 32.5 min per day in the high-load treatment group compared to the low-load group, primarily due to a within-group reduction in sedentary time and an increase in light physical activity in the low-load group. The increased sedentary time observed between groups may be related to discomfort from the heavier vest and a higher incidence of musculoskeletal side effects in the high-load group. All participants were instructed to increase their time spent standing, which is typically associated with increased physical activity. However, no between-group differences in standing time were observed based on participants’ daily records. It is possible that the high-load group adhered to the standing instructions to a lesser degree than the low-load group, which may have contributed to the observed differences in physical activity. These differences in physical activity levels could have attenuated some of the beneficial effects of increased weight-loading on fat mass and its distribution. Despite these challenges, it is noteworthy that the high-load treatment still demonstrated improvements in body composition, including reductions in fat mass and waist circumference, even in the absence of increased physical activity. It should be noted that accelerometer-based assessments of physical activity levels have limitations, including potential misclassification of activity intensity and an inability to fully capture certain types of movement such as cycling or resistance training. Additionally, the high-load group reported a higher incidence of upper respiratory tract infections compared to the low-load group which may have affected overall activity levels during the intervention. While the cause for this is unclear, it is possible that carrying a heavy vest induced physiological or psychological stress, which may have influenced immune function. Previous studies have linked stress and elevated cortisol to increased susceptibility to infections [45, 46]. This potential connection between weight-loading, stress and susceptibility to infections warrants further investigation. Despite these challenges, our findings underscore that increased weight-loading reduced fat mass and generated a healthier body composition, independent of physical activity changes and despite higher incidence of respiratory infections.

Despite the beneficial changes in body composition, there was no difference in the daily total energy expenditure (TEE) or reported energy intake in the present study. TEE is strongly related to fat-free mass, and the two largest components of TEE are basal metabolic rate (BMR) and activity-induced physical activity [47, 48]. It has previously been demonstrated that increased physical activity does not affect energy balance due to a compensatory increase in energy intake [49]. Furthermore, it has been shown that when individuals exercise more, TEE does not increase steadily and that individuals tend to adapt metabolically to increased physical activity by a compensatory reduction of other daily physical activities [47, 50]. These findings agree with what we observed in the present study with increased sedentary time in the high-load group compared to the low-load group that may in part explain why we did not observe an increased TEE in the high-load treatment group. We did not observe any significant effect of increased loading on reported food intake. As the variations are large and the reliability of self-reported data is low for food intake, we believe that the present negative findings on food intake should be further evaluated in larger studies using objectively determined food intake data.

In this study, the fat mass-reducing effect of increased loading was observed primarily in weight-bearing regions, such as the legs and trunk but not in the arms. This may reflect a higher muscular workload in these regions to support posture and movement during vest use. The increased workload in the high-load group may also explain the observed increases in lean mass in the abdominal region since exercise is known to induce muscle hypertrophy [51, 52]. Interestingly, no between-group differences were observed in leg lean mass, despite the expectation that high-load treatment would increase workload in the legs. This discrepancy could be attributed to the increased sedentary time in the high-load group, as trunk muscles remain active even while sitting, whereas leg muscles are primarily activated during movement. The mechanism behind the tissue-specific effect of exercise training on fat mass is unclear. While some studies suggest that exercise-induced fat loss may be either systemic or regional [53–55], evidence for regional effects on fat mass and lean mass from standing alone remains inconclusive [56, 57]. It is possible that the effects shown in the present study, particularly the increase in lean mass, are mainly caused by increased muscular workload. However, increased weight-loading may also elevate regional energy consumption in load-bearing tissues, independent of muscle activity, suggesting a potential loading-dependent mechanism affecting localised fat loss [58].

It has been proposed that the human body may sense changes in mass or gravitational forces in order to regulate fat mass and maintain a body weight that is optimal for functioning within Earth’s gravitational field. This regulation may occur independently of leptin signaling [28, 29, 59, 60]. The mechanisms underlying this proposed homeostatic regulation of body weight and fat mass remain to be determined but may involve gravitational sensing and neuronal signaling pathways [28, 61]. In the present human study with a duration of 5 weeks, fat mass was reduced by increased loading, while body weight was not significantly reduced as the effect on body weight was partly counteracted by an increased lean mass. This finding indicates that the balance between fat mass and lean mass is regulated by increased loading in humans. Obesity treatment has advanced significantly with the introduction of long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists [62, 63], which have led to substantial reductions in both body weight and fat mass. However, these pharmacological treatments are also associated with a loss of lean mass, which may be particularly problematic in individuals with sarcopenic obesity [7, 9, 64]. Based on our present findings, we propose that weight-loading may be useful as an addition to GLP-1-based therapies in patients with sarcopenic obesity—not only to enhance fat loss, but also to preserve or even increase lean mass. That said, although the current loading protocol improved body composition, it will require refinement to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal adverse events. A more gradual, progressive increase in loading and/or duration of wear time may help reduce physical strain and support long-term adherence.

The present study has several strengths, such as the randomised design with a predefined analysis plan and rigorous design following IHC guidelines. The main outcomes were measured using gold standard techniques such as DXA and abdominal CT of fat mass distribution, doubly labelled water of total energy expenditure and tri-axial accelerometers of physical activity and sedentary time. The control (low-load) group also wore an identical weight vest but with less weight added compared to the weight vest in the high-load group. However, a limitation is that blinding was not possible because both the investigators and the participants could feel the weight of the vests. Another limitation is that the daily time of using the weight vest and the time using the weight vest standing were self-reported and relatively short, especially the time with the vest in standing position. Additionally, a limitation is the timing of the DXA-scans which were performed in the evenings following a 3-h fasting protocol, instead of in the morning after an overnight fast [65]. The method used to collect and process the accelerometer data could underestimate physical activity outcomes and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Finally, the present study only evaluated the effect of increased weight-loading in participants with mild obesity (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2). Therefore, further studies should also evaluate individuals with severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) and normal weight (BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m2) separately.

Conclusions

In conclusion, increased weight-loading reduces fat mass and increases lean mass in individuals with obesity, providing a healthier body composition with reduced waist circumference. These beneficial effects were achieved despite increased sedentary time, a higher incidence of musculoskeletal side effects and a higher incidence of respiratory tract infections in the high-load group compared to the low-load group. The effect on fat mass was most pronounced in tissues exposed to increased loading, implying regional fat loss possibly due to locally increased energy consumption. Similarly, increases in lean mass were localised to regions exposed to weight-loading. Future clinical studies should investigate the mechanism underlying these localised effects, including possible local effects on energy expenditure in tissues exposed to loading. Additionally, exploring how increased weight-loading treatment interacts with other lifestyle changes, such as increased exercise or dietary modifications, could help identify new treatments strategies to reduce fat mass, improve body composition and promote cardiometabolic health.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 3: Supplementary information. Supplementary methods. Body weight and body composition. Abdominal adipose tissue. Energy expenditure. Physical activity. Blood sampling. Statistical analysis. Supplementary tables. Table S1 – Results: relative changes. Table S2 – Results: absolute changes. Table S3 – Results: relative changes. Table S4 – Results: absolute regional body composition changes. Table S5 – Results: serum/plasma markers. Table S6 – Reported adverse events and serious adverse events. Table S7 – Medical history at baseline for all randomised participants. Table S8 – Concomitant medications.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the contribution of the personnel at the Clinical Trial Center, Gothia Forum, Sahlgrenska University Hospital for their excellent assistance during the study and the participants who participated. Fig. 2 created with publication rights from BioRender.com.

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

Analysis of covariance

- ATLAS

Anti-obesity Treatment by Loading in Adult Subjects

- BMC

Bone mineral content

- BMI

Body mass index

- BMR

Basal metabolic rate

- CI

Confidence interval

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CT

Computed tomography

- DLW

Doubly labelled water

- DXA

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- ECG

Electrocardiography

- EE

Energy expenditure

- eCRF

Electronic case report form

- FAS

Full analysis set

- GCP

Good clinical practice

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- HU

Hounsfield Units

- ICH

International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines

- IMAT

Intermuscular adipose tissue

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- LPA

Light physical activity

- MET

Metabolic equivalents of task

- Mg

Millig-unit (acceleration)

- MJ

Megajoule

- MPA

Moderate physical activity

- MVPA

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- PA

Physical activity

- PP

Per protocol

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SAE

Severe adverse event

- SAT

Subcutaneous adipose tissue

- SD

Standard deviation

- SDQ

Short Dietary Questionnaire

- SED

Sedentary time

- TEE

Total energy expenditure

- VAT

Visceral adipose tissue

- VPA

Vigorous physical activity

- VVPA

Very vigorous physical activity

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, J.B., C.O., PA.J., and JO.J.; Methodology, J.B., C.L., JO.J., C.O., and PA.J.; Access to all data, J.B., C.O., and PA.J.; Formal Analysis, J.B., and C.O.; Investigation, J.B., D.C., M.J., N.L., D.A., J.F., L.W., M.G.; Resources, J.K., K.W., M.B, C.L, and S.P.; Writing – Original Draft, J.B., and C.O.; Writing – Review & Editing, J.B., K.W., L.W., M.L., N.L., J.K., C.L., M.G., S.P., J.F., D.A., M.B., D.C., JO.J, PA.J., and C.O.; Visualization, J.B., C.O., JO.J, and PA.J.; Supervision, C.O., PA.J., JO.J.; Funding Acquisition, PA.J., J.B., JO.J, and C.O.; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. The study was financed by grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-965051), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW 2020.0230), the Torsten Söderberg Foundation (MT3/20), Foundation Mary von Sydows, född Wijk, donationsfond (2024–139), and the Göteborgs Läkaresällskap (The Gothenburg Society of Medicine; 22/972547).

Data availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data generated or analysed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided. Study protocol and statistical analysis plan will be available with this publication.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (registration number 2021–00095) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines (ICH) for Good Clinical Practice (GCP). All participants provided written informed consent before undertaking any study procedures.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Obesity and overweight. 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- 2.Chu DT, Minh Nguyet NT, Nga VT, Thai Lien NV, Vo DD, Lien N, et al. An update on obesity: mental consequences and psychological interventions. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phelps NH, Singleton RK, Zhou B, Heap RA, Mishra A, Bennett JE, et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:989–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christoffersen BØ, Sanchez-Delgado G, John LM, Ryan DH, Raun K, Ravussin E. Beyond appetite regulation: targeting energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and lean mass preservation for sustainable weight loss. Obesity. 2022;30:841–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pouget M, Pinel A, Miolanne M, Gentes E, Picard M, Martinez R, et al. Improving the functional detection of sarcopenic obesity: prevalence and handgrip scoring in the OBESAR cohort. Obesity. 2024;32:2237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devries MC, Giangregorio L. Using the specificity and overload principles to prevent sarcopenia, falls and fractures with exercise. Bone. 2023;166:116573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefanakis K, Kokkorakis M, Mantzoros CS. The impact of weight loss on fat-free mass, muscle, bone and hematopoiesis health: implications for emerging pharmacotherapies aiming at fat reduction and lean mass preservation. Metabolism. 2024;161:156057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson K, Lewis, Sloan CE, Bessesen DH, Arterburn D. Effectiveness and safety of drugs for obesity. BMJ. 2024;384:e072686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masood B, Moorthy M. Causes of obesity: a review. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23:284–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodpaster BH, Bergman BC, Brennan AM, Sparks LM. Intermuscular adipose tissue in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023;19:285–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Munck TJI, Soeters PB, Koek GH. The role of ectopic adipose tissue: benefit or deleterious overflow? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suka Aryana IGP, Paulus IB, Kalra S, Daniella D, Kuswardhani RAT, Suastika K, et al. The important role of intermuscular adipose tissue on metabolic changes interconnecting obesity, ageing and exercise: a systematic review. touchREV Endocrinol. 2023;19:54–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Addison O, Marcus RL, LaStayo PC, Ryan AS. Intermuscular fat: a review of the consequences and causes. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:309570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Björntorp P, Rosmond R. Visceral obesity and diabetes. Drugs. 1999;58 Suppl 1:13–8 (discussion 75-82). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lind L, Ärnlöv J, Lampa E. The interplay between fat mass and fat distribution as determinants of the metabolic syndrome is sex-dependent. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2017;15:337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuval K, Barlow CE, Finley CE, Gabriel KP, Schmidt MD, DeFina LF. Standing, obesity, and metabolic syndrome: findings from the cooper center longitudinal study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1524–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husu P, Suni J, Tokola K, Vaha-Ypya H, Valkeinen H, Maki-Opas T, et al. Frequent sit-to-stand transitions and several short standing periods measured by hip-worn accelerometer are associated with smaller waist circumference among adults. J Sports Sci. 2019;37:1840–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garthwaite T, Sjoros T, Koivumaki M, Laine S, Vaha-Ypya H, Saarenhovi M, et al. Standing is associated with insulin sensitivity in adults with metabolic syndrome. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24:1255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garthwaite T, Sjöros T, Laine S, Vähä-Ypyä H, Löyttyniemi E, Sievänen H, et al. Effects of reduced sedentary time on cardiometabolic health in adults with metabolic syndrome: a three-month randomized controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport. 2022;25:579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garthwaite T, Sjöros T, Laine S, Koivumäki M, Vähä-Ypyä H, Eskola O, et al. Associations of sedentary time, physical activity, and fitness with muscle glucose uptake in adults with metabolic syndrome. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2023;33:353–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betts JA, Smith HA, Johnson-Bonson DA, Ellis TI, Dagnall J, Hengist A, et al. The energy cost of sitting versus standing naturally in man. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kangas P, Tahvanainen A, Tikkakoski A, Koskela J, Uitto M, Viik J, et al. Increased cardiac workload in the upright posture in men: noninvasive hemodynamics in men versus women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buffey AJ, Herring MP, Langley CK, Donnelly AE, Carson BP. The acute effects of interrupting prolonged sitting time in adults with standing and light-intensity walking on biomarkers of cardiometabolic health in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022;52:1765–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen BK. The physiology of optimizing health with a focus on exercise as medicine. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:607–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine JA, Lanningham-Foster LM, McCrady SK, Krizan AC, Olson LR, Kane PH, et al. Interindividual variation in posture allocation: possible role in human obesity. Science. 2005;307:584–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansson JO, Palsdottir V, Hagg DA, Schele E, Dickson SL, Anesten F, et al. Body weight homeostat that regulates fat mass independently of leptin in rats and mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohlsson C, Hagg DA, Hammarhjelm F, Dalmau Gasull A, Bellman J, Windahl SH, et al. The gravitostat regulates fat mass in obese male mice while leptin regulates fat mass in lean male mice. Endocrinology. 2018;159:2676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou R, Guo Q, Xiao Y, Guo Q, Huang Y, Li C, et al. Endocrine role of bone in the regulation of energy metabolism. Bone Res. 2021;9:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagnotti GM, Styner M, Uzer G, Patel VS, Wright LE, Ness KK, et al. Combating osteoporosis and obesity with exercise: leveraging cell mechanosensitivity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:339–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohlsson C, Gidestrand E, Bellman J, Larsson C, Palsdottir V, Hagg D, et al. Increased weight loading reduces body weight and body fat in obese subjects - a proof of concept randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;22:100338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergström G, Berglund G, Blomberg A, Brandberg J, Engström G, Engvall J, et al. The Swedish CArdioPulmonary BioImage Study: objectives and design. J Intern Med. 2015;278:645–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kullberg J, Hedström A, Brandberg J, Strand R, Johansson L, Bergström G, et al. Automated analysis of liver fat, muscle and adipose tissue distribution from CT suitable for large-scale studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Westerterp KR, Wouters L, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. The Maastricht protocol for the measurement of body composition and energy expenditure with labeled water. Obes Res. 1995;3:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerterp KR. Doubly labelled water assessment of energy expenditure: principle, practice, and promise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117:1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svensson A, Renstrom F, Bluck L, Lissner L, Franks PW, Larsson C. Dietary intake assessment in women with different weight and pregnancy status using a short questionnaire. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1939–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fridolfsson J, Börjesson M, Buck C, Ekblom Ö, Ekblom-Bak E, Hunsberger M, et al. Effects of frequency filtering on intensity and noise in accelerometer-based physical activity measurements. Sensors (Basel). 2019;19:2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fridolfsson J, Buck C, Hunsberger M, Baran J, Lauria F, Molnar D, et al. High-intensity activity is more strongly associated with metabolic health in children compared to sedentary time: a cross-sectional study of the I.Family cohort. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arvidsson D, Fridolfsson J, Buck C, Ekblom Ö, Ekblom-Bak E, Lissner L, et al. Reexamination of accelerometer calibration with energy expenditure as criterion: VO2net instead of MET for Age-Equivalent Physical Activity Intensity. Sensors (Basel). 2019;19:3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR working group on visceral obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee Y-H, Hsiao H-F, Yang H-T, Huang S-Y, Chan WP. Reproducibility and repeatability of computer tomography-based measurement of abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fridolfsson J, Börjesson M, Arvidsson D. A Biomechanical re-examination of physical activity measurement with accelerometers. Sensors. 2018;18:3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arvidsson D, Fridolfsson J, Ekblom-Bak E, Ekblom Ö, Bergström G, Börjesson M. Fundament for a methodological standard to process hip accelerometer data to a measure of physical activity intensity in middle-aged individuals. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2024;34:e14541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, Miller GE, Frank E, Rabin BS, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5995–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1685–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westerterp KR. Physical activity and physical activity induced energy expenditure in humans: measurement, determinants, and effects. Front Physiol. 2013;4:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metcalfe NB, Bellman J, Bize P, Blier PU, Crespel A, Dawson NJ, et al. Solving the conundrum of intra-specific variation in metabolic rate: a multidisciplinary conceptual and methodological toolkit: new technical developments are opening the door to an understanding of why metabolic rate varies among individual animals of a species: new technical developments are opening the door to an understanding of why metabolic rate varies among individual animals of a species. BioEssays. 2023;45:e2300026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin CK, Johnson WD, Myers CA, Apolzan JW, Earnest CP, Thomas DM, et al. Effect of different doses of supervised exercise on food intake, metabolism, and non-exercise physical activity: the E-MECHANIC randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:583–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westerterp KR. Exercise for weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:540–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konopka AR, Harber MP. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy after aerobic exercise training. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2014;42:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- vs. high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31:3508–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trapp EG, Chisholm DJ, Freund J, Boutcher SH. The effects of high-intensity intermittent exercise training on fat loss and fasting insulin levels of young women. Int J Obes. 2008;32:684–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scotto di Palumbo A, Guerra E, Orlandi C, Bazzucchi I, Sacchetti M. Effect of combined resistance and endurance exercise training on regional fat loss. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017;57:794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramírez-Campillo R, Andrade DC, Campos-Jara C, Henríquez-Olguín C, Alvarez-Lepín C, Izquierdo M. Regional fat changes induced by localized muscle endurance resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:2219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barbieri DF, Brusaca LA, Mathiassen SE, Oliveira AB, Srinivasan D. Do sit-stand tables affect physical behavior and body composition similarly in normal-weight and overweight office workers? A pilot study. IISE Transact Occup Ergonomics Hum Factors. 2023;11:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saeidifard F, Medina-Inojosa JR, Supervia M, Olson TP, Somers VK, Prokop LJ, et al. The effect of replacing sitting with standing on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2020;4:611–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bellman J, Sjöros T, Hägg D, Atencio Herre E, Hieta J, Eskola O, et al. Loading Enhances Glucose Uptake in Muscles, Bones, and Bone Marrow of Lower Extremities in Humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109:3126–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Cabanac M, Duclaux R, Spector NH. Sensory feedback in regulation of body weight: is there a ponderostat? Nature. 1971;229:125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adams CS, Korytko AI, Blank JL. A novel mechanism of body mass regulation. J Exp Biol. 2001;204(Pt 10):1729–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zlatkovic J, Dalmau Gasull A, Hägg D, Font-Gironès F, Bellman J, Meister B, et al. Reduction of body weight by increased loading is associated with activation of norepinephrine neurones in the medial nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023;35:e13352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryan DH, Lingvay I, Deanfield J, Kahn SE, Barros E, Burguera B, et al. Long-term weight loss effects of semaglutide in obesity without diabetes in the SELECT trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:2049–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Esbjerg S, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2221–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hope DCD, Tan TM-M. Skeletal muscle loss and sarcopenia in obesity pharmacotherapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2024;20:695–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Nana A, Slater GJ, Stewart AD, Burke LM. Methodology review: using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for the assessment of body composition in athletes and active people. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015;25:198–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 3: Supplementary information. Supplementary methods. Body weight and body composition. Abdominal adipose tissue. Energy expenditure. Physical activity. Blood sampling. Statistical analysis. Supplementary tables. Table S1 – Results: relative changes. Table S2 – Results: absolute changes. Table S3 – Results: relative changes. Table S4 – Results: absolute regional body composition changes. Table S5 – Results: serum/plasma markers. Table S6 – Reported adverse events and serious adverse events. Table S7 – Medical history at baseline for all randomised participants. Table S8 – Concomitant medications.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data generated or analysed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided. Study protocol and statistical analysis plan will be available with this publication.