Abstract

Background

The rapid spread of digital technologies has become important in work and social life. However, prolonged use of digital screens, such as digital eye strain, negatively affects individuals. This has increased the importance of using valid and reliable scales to assess digital eye strain.

Methods

To adapt the Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ) into Turkish for validity and reliability. This study followed a methodological research design in accordance with the EQUATOR checklist. This methodological study was conducted in Istanbul with 401 individuals continuously exposed to digital screens for at least 2 h. Data were collected via the sociodemographic characteristics form, DESQ, and the Problematic Internet Use Scale (PIUS). The study was conducted in five consecutive stages: direct translation, synthesis of translations, back translation, expert committee evaluation, and validity and reliability analysis.

Results

Individuals spent an average of 6.66 ± 3.20 h per day in front of a digital screen. The content validity index of the DESQ was found to be 0.962, and the confirmatory factor analysis results, the model's fit indices were high and statistically significant (χ2 = 161.689, sd = 62). The reliability analysis revealed that the Kuder‒Richardson 20 value was 0.787, and the item‒total correlation values ranged between 0.306 and 0.517. The parallel form correlation between the DESQ and PIUS scores revealed statistically significant relationships between the subdimensions and total scores.

Conclusions

The results prove that the Turkish version of the DESQ is valid and reliable for assessing digital eye strain.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12886-025-04149-x.

Keywords: Digital eye strain, Digital screen, Validity, Reliability, Scale adaptation

Background

The widespread use of digital screen devices has increased substantially across all age groups, becoming an integral part of daily life. While such technologies enhance convenience and accessibility, prolonged and improper usage can lead to several health concerns, most notably those related to eye health [1–3]. In recent years, scientific evidence has underscored the negative impact of extended screen exposure on vision, giving rise to the concepts of digital eye strain (DES) and computer vision syndrome (CVS) [1, 4]. DES is characterized by visual and musculoskeletal symptoms such as eye fatigue, blurred vision, and neck or shoulder pain, typically emerging after extended screen time [1, 5, 6].

The pathogenesis of DES is multifactorial. Individual factors such as pre-existing eye conditions and environmental conditions like improper lighting, poor screen ergonomics, and image quality contribute significantly to symptom development [4, 5, 7–9]. Additionally, the use of smartphones for more than two hours daily has been found to heighten DES risk [6, 7]. The syndrome’s symptoms are commonly grouped into ocular, accommodative, and extraocular categories [8, 9]. Although preventable, DES has emerged as a global occupational health issue, with a growing prevalence among students, office workers, and especially healthcare professionals [8–13].

Despite its high prevalence, standardized tools for the early detection of Digital Eye Strain (DES) remain limited. Recent studies indicate that a considerable number of individuals experience symptoms associated with DES [9, 11, 14–16]. Given the challenges of developing new instruments, adapting validated scales for the Turkish population is a practical and evidence-based approach [17]. Therefore, this study aimed to translate the 13-item Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ) into Turkish and evaluate its reliability and validity. The adaptation of this scale will facilitate early identification of DES in healthcare settings and guide prevention strategies to improve both worker well-being and patient safety.

Methods

Study design

This methodological study was conducted to determine the validity and reliability of the Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ) by adapting it into Turkish. The study population consisted of individuals continuously exposed to digital screens for 2 h or more. Screen exposure has increased significantly with the widespread use of digital technologies. In this context, the snowball sampling method was preferred to reach a large and diverse group of participants while determining the study sample. In scale validity and reliability studies, the sample size should be 5–10 times the number of scale items or 200–300 to perform factor analysis [17, 18]. In studies with more advanced techniques, such as factor analysis, the sample should be 20 times the number of scale items [19]. In this study, since the Turkish adapted scale has 13 items, it was decided that the sample should consist of at least 300 participants, and the sample consisted of 401 participants.

Eligibility criteria

The study included individuals who were over 18 years of age, had the mental capacity to follow the study instructions, had no intellectual or communicative disabilities, had not been previously diagnosed with dry eye by a physician, had no history of eye trauma, had not received any ophthalmologic treatment in the last month, and had at least 2 h of continuous screen exposure during the day. Individuals with long-term eye pathology that may affect visual acuity (e.g., macular degeneration, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, cataracts, glaucoma, and significant irregular astigmatism) and a history of eye trauma were excluded.

Instruments

The data were collected through the Sociodemographic Characteristics Form, Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ), and Problematic Internet Use Scale (PIUS).

Sociodemographic characteristics form

This form was created by reviewing the relevant literature [1, 9, 15, 20–22] and included personal information such as gender, age, marital status, education level, employment status, and occupation, as well as information on income level, presence of chronic diseases, regular medication use, time spent in the digital environment linked to playing games, devices used to play digital games and frequency of playing games.

Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ)

The DESQ was developed by Mylona et al. [9]. In 2022, to identify eye-related symptoms in individuals with eye problems or who spend excessive time playing games and using screen devices. The DESQ is a thirteen-item self-report scale in a yes–no format. The questionnaire includes a three-factor structure: adaptation problems due to overuse, dry eye problems, and postural disorders. High scores on the scale indicate the intensity of eye-related problems experienced by individuals [9]. A cutoff score was not recommended because of the heterogeneity of the three factors. The Cronbach's alpha value for the original scale was 0.94 [15].

Problematic Internet Use Scale (PIUS)

The PIUS was first developed by Ceyhan and Ceyhan (2007) for university students. Consisting of 27 items, the scale is scored from 1 to 5 and provides an assessment based on self-reports [22]. The scale's total score is obtained by summing the scores of the responses to these items, and the scale score ranges between 27 and 135. However, items 7 and 10 on the scale are reversed and included in the scoring. A high score on the scale indicates that individuals' internet use is unhealthy, that the internet negatively affects their lives, and that they are prone to pathologies such as addiction [23]. In the original scale, the overall Cronbach's alpha value was 0.93. In contrast, the internal consistency coefficients of the subscales were 0.93 for the negative consequences of the Internet, 0.76 for overuse, and 0.78 for social benefit/social comfort [23]. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha value was 0.931.

Procedure

This study comprises five unique, interconnected, and sequential stages, following the methodology suggested by the scientific literature [24]. The stages are carried out as follows (Fig. 1):

Direct translation: Two bilingual translators, whose native language is Turkish, independently translated the original questionnaire into the target language.

Synthesis of translations: The two translators from the previous stage (T1 and T2) convened online to synthesize and compare their translations, identify differences in terms or expressions, and reach a consensus to produce a unified Turkish version of the questionnaire.

Back-translation: The synthesized version from the previous stage was back-translated into English (the original language) by two bilingual native English translators. These translators, who had no involvement in the prior stages, worked independently and without access to the original DESQ, ensuring blinding during the process.

Expert committee review: A multidisciplinary committee of 12 experts, including nursing professionals, academicians, and ophthalmologists, was formed. Each expert reviewed the scale and provided their assessments. Items were evaluated using the following criteria: not appropriate (requires removal from the test), somewhat appropriate (requires revision of the item/expression), appropriate (appropriate but requires minor modifications), and very appropriate (suitable as is). Based on these evaluations, the scale was finalized.

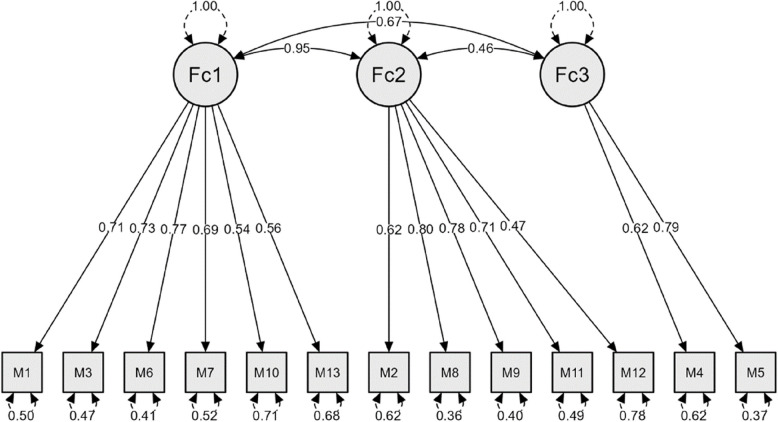

Pretest (applicability/feasibility): The pretest version of the questionnaire obtained in the previous stage was tested to evaluate the quality of the translation and cultural adaptation, assess its comprehensibility, verify its applicability and feasibility, and examine its face validity. The results were analyzed via item analysis (Kuder‒Richardson 20) and internal consistency tests. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to ensure construct validity, and the path diagram and factor loadings were presented (Fig. 2). Additionally, parallel-form reliability was tested via the PIUS to further ensure the study's reliability.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the translation and cross-cultural adaptation stages of DES-Q© into Turkish

Fig. 2.

Path diagram and factor loadings for the validated model (Standardized Estimates)

Implementation of the scale

After obtaining the necessary permissions for the scale's validity and reliability tests, the study was continued until it reached 401 individuals who met the inclusion criteria. Research data were collected through online Google Forms via self-reports. If individuals were willing to participate before starting the study, they were asked to press the "I approve" button, and data were obtained from those who agreed to participate.

Ethical considerations

Mylona gave written permission via e-mail to conduct the Turkish validity and reliability study of the Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ). Ethics committee approval (Date: 28.08.2024 Number: 2840420) was obtained from a university's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Ethics Committee to conduct the study. The Helsinki Declaration on Human Rights was followed throughout the study.

Data analysis

The data obtained in the study were subjected to statistical analysis via the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The conformity of the variables to a normal distribution was examined via the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test, Q‒Q graphs, and histograms. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage, median) were used, the Mann‒Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative data between two groups, and the Kruskal‒Wallis test was used for comparisons between more than one group. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to determine the validity of the questionnaire, and the Kuder‒Richardson 20 coefficient and Phi correlation analysis were used to measure reliability. Test reliability was evaluated with Spearman’s correlation coefficient, and significance levels were determined as p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Results

Descriptive results

According to Table 1, 33.4% of the study participants were female, 58.4% were 35 or younger, and 77.3% had a bachelor's degree or higher. 56.9% of the individuals who spent an average of 6.66 ± 3.20 h per day on the computer spent more than five hours. While 51.9% of individuals prefer to play games on a computer, 65.9% of these games are played via phone. Additionally, 27.9% of those who were surveyed reported playing games regularly every day.

Table 1.

Findings regarding individuals' sociodemographic characteristics and digital screen time (n = 401)

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | n (%) | |

| Gender | Female | 267 (66.6) |

| Male | 134 (33.4) | |

| Age group | Under 35 | 234 (58.4) |

| Over 35 | 167 (41.6) | |

| Marital status | Married | 205 (51.1) |

| Single | 196 (48.9) | |

| Educational status | High school and below | 45 (11.2) |

| Associate degree | 46 (11.5) | |

| Bachelor's degree and above | 310 (77.3) | |

| Working status | Employed | 320 (79.8) |

| Not employed | 81 (20.2) | |

| Working style | Daytime | 264 (65.8) |

| Day and night | 137 (34.2) | |

| Presence of chronic disease under continuous treatment | Yes | 76 (19) |

| No | 325 (81) | |

| Regular medication use | Yes | 86 (21.4) |

| No | 315 (78.6) | |

| Characteristics of Digital Screen Time | n (%) | |

| Average daily time spent in front of the screen (hours) | Min–Max | 2–18 |

| Avg ± SD | 6.66 ± 3.20 | |

| Average daily time spent in front of the screen (hours) | 5 h and below | 173 (43.1) |

| 5 h and above | 228 (56.9) | |

| General enjoyment of playing games in digital environments | Yes | 208 (51.9) |

| No | 193 (48.1) | |

| *If yes, preferred tools for playing games (n = 208) | Computer/tablet | 85 (40.9) |

| Game console | 31 (14.9) | |

| Phone | 137 (65.9) | |

| Other | 9 (4.3) | |

| Working status | Never | 21 (10.1) |

| Once in 2–3 months | 27 (13) | |

| Once a month | 18 (8.7) | |

| Once a week | 25 (12) | |

| 3–4 times a week | 59 (28.4) | |

| Every day | 58 (27.9) | |

Quantitative data are presented as Minimum–Maximum and Mean ± Standard Deviation. Qualitative data are presented as numbers (percentage). *More than one game tool is used

Reliability of the DESQ

The item analyses of the DESQ are given in Table 2. The questionnaire's overall internal consistency coefficient (Kuder‒Richardson 20) was 0.787, indicating a moderate consistency. The item–total correlation values of the items in the questionnaire ranged between.

Table 2.

Results of the item analysis of the DESQ (n = 401)

| Items | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | a Item-Total Correlation | When Item Deleted Kuder-Richardson 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 130 (32.4) | 271 (67.6) | 0.483 | 0.766 |

| Item 2 | 181 (45.1) | 220 (54.9) | 0.418 | 0.773 |

| Item 3 | 228 (56.9) | 173 (43.1) | 0.517 | 0.762 |

| Item 4 | 211 (52.6) | 190 (47.4) | 0.371 | 0.787 |

| Item 5 | 276 (68.8) | 125 (31.2) | 0.343 | 0.780 |

| Item 6 | 102 (25.4) | 299 (74.6) | 0.509 | 0.764 |

| Item 7 | 130 (32.4) | 271 (67.6) | 0.471 | 0.767 |

| Item 8 | 69 (17.2) | 332 (82.8) | 0.465 | 0.769 |

| Item 9 | 91 (22.7) | 310 (77.3) | 0.470 | 0.768 |

| Item 10 | 209 (52.1) | 192 (47.9) | 0.383 | 0.776 |

| Item 11 | 139 (34.7) | 262 (65.3) | 0.490 | 0.765 |

| Item 12 | 27 (6.7) | 374 (93.3) | 0.306 | 0.787 |

| Item 13 | 69 (17.2) | 332 (82.8) | 0.352 | 0.778 |

aPhi Correlation Coefficient was used

0.306 and 0.517. The internal consistency coefficient (KR-20) obtained when the items in the questionnaire were deleted separately ranged between 0.762 and 0.787, and these values did not exceed the general internal consistency coefficient of 0.787.

When the results of the correlation between the mean scores of the DESQ and PIUS were analyzed to evaluate the agreement between the parallel forms, a statistically significant correlation was found between the mean scores of the subscales and the total scores of this questionnaire and scale (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation evaluation of individuals' DESQ and PIUS scores (n = 401)

| PIUS/DESQ | Adaption issues | Dry eye issues | Posture issues | DESQ Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r; p | r; p | r; p | r; p | |

| Negative consequences of the internet | 0.186; < 0.001 | 0.169; 0.001 | 0.166; 0.001 | 0.217; < 0.001 |

| Excessive use | 0.247; < 0.001 | 0.152; 0.002 | 0.183; < 0.001 | 0.249; < 0.001 |

| Social benefit / social comfort | 0.151; 0.002 | 0.118; 0.008 | 0.115; 0.002 | 0.164; < 0.001 |

| PIUS Total | 0.217; < 0.001 | 0.174; < 0.001 | 0.179; < 0.001 | 0.240; < 0.001 |

Spearman Rho Correlation Analysis p < 0.01

Validity of the DESQ

To evaluate the appropriateness of the questionnaire items, 12 nurses, nurse academicians, and ophthalmologists who are experts in their fields were contacted, and content validity indices were obtained. The content validity index (CVI) for the items ranged between 0.750 (item 3) and 1.000, which is higher than the generally accepted standard level (0.800 and above). The content validity index for the questionnaire was 0.962, which is relatively high. Factor analysis of the questionnaire items was conducted. Table 4 shows the fit indices obtained from confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA revealed that the fit indices of the model provided a good level of validity. The fit indices of the individuals were found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 161.689, sd = 62, p < 0.001; p < 0.01). The normalized chi-square (NC) was 2.607, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) was 0.964, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.063, the comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.935, the normalized fit index (NFI) was 0.900, the relative fit index (RFI) was 0.875. The incremental fit index (IFI) was 0.936 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Goodness-of-fit indices obtained for the confirmatory factor analysis (n = 401)

| Indexes | Values |

|---|---|

| (χ2 = 161.689/sd = 62)** | |

| NC (Normalized Chi-Square) | 2.607 |

| GFI (Goodness-of-Fit Index) | 0.964 |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) | 0.063 |

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) | 0.935 |

| NFI (Normalized Fit Index) | 0.900 |

| RFI (Relative Fit Index) | 0.875 |

| IFI (Incremental Fit Index) | 0.936 |

χ2: Chi-Square Goodness-of-Fit Test sd: Degree of Freedom **p < 0.01

In Table 5, the mean total and subdimensional scores of the DESQ and PIUS were evaluated with respect to the time the participants spent in front of the screen. Those exposed to digital screens for 5 h or more a day and those who liked to play digital games had higher DESQ totals, adaptation issues, posture issues, subdimensional mean scores, and statistically significant differences. The mean scores of the total and excessive use subdimensions of the PIUS were greater in those who used it for 5 h or more, and the difference was statistically significant.

Table 5.

Evaluation of DESQ and PIUS scores according to the time individuals spend in front of the screen and their gaming status in digital environments (n = 401)

| Questionnaire and Scale | Average daily screen time | Test Value | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 h and below | 5 h and above | ||||||||

| DESQ | Adaption issues | 1.83 ± 1.64 (1) | 2.42 ± 1.72 (2) | -3.454 | 0.001** | ||||

| Dry eye issues | 1.08 ± 1.11 (1) | 1.29 ± 1.29 (1) | -1.249 | 0.212 | |||||

| Posture issues | 1.11 ± 0.83 (1) | 1.29 ± 0.73 (1) | -2.124 | 0.034* | |||||

| DESQ Score | 4.02 ± 2.98 (4) | 5.00 ± 2.97 (5) | -3.256 | 0.001** | |||||

| PIUS | Negative consequences of the internet | 25.97 ± 10.51 (23) | 26.98 ± 10.61 (24) | -1.457 | 0.147 | ||||

| Excessive use | 14.85 ± 4.22 (14) | 16.05 ± 4.32 (16) | -2.976 | 0.003** | |||||

| Social benefit/social comfort | 10.10 ± 4.66 (8) | 10.39 ± 5.07 (9) | -0.505 | 0.614 | |||||

| PIUS Total | 50.92 ± 16.82 (47) | 53.42 ± 17.74 (50) | -1.588 | 0.112 | |||||

| Generally, like playing games in the digital environment | |||||||||

| Yes | No | ||||||||

| DESQ | Adaption issues | 2.35 ± 1.76 (2) | 1.99 ± 1.65 (2) | -2.016 | 0.044* | ||||

| Dry eye issues | 1.27 ± 1.24 (1) | 1.13 ± 1.20 (1) | -1.286 | 0.198 | |||||

| Posture issues | 1.34 ± 0.74 (2) | 1.10 ± 0.80 (1) | -2.116 | 0.002** | |||||

| DESQ Total | 4.97 ± 3.04 (5) | 4.21 ± 2.95 (4) | -2.334 | 0.020* | |||||

| PIUS | Negative consequences of the internet | 28.29 ± 11.43 (26) | 24.67 ± 9.21 (22) | -3.389 | 0.001** | ||||

| Excessive use | 16.06 ± 4.53 (16) | 14.96 ± 4.01 (15) | -2.380 | 0.017* | |||||

| Social benefit/social comfort | 10.95 ± 5.20 (9) | 9.52 ± 4.44 (8) | -3.303 | 0.001** | |||||

| PIUS Total | 55.3 ± 18.89 (52) | 49.15 ± 14.98 (46) | -3.247 | 0.001** | |||||

Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (Median). Mann Whitney U Test. *p < 0.0. **p < 0.01

Discussion

This study aimed to translate and culturally adapt the DESQ into Turkish in a group exposed to digital screens for at least two hours a day and playing digital games on a computer. For this adaptation study, a total of 13 items were administered to 401 participants, and the 3-factor structure of the original scale was preserved. Total collinearity, parallel-form reliability and reliability analyses, and content and content validity tests revealed that the questionnaire is valid and reliable in China. This study demonstrates the scale’s successful cultural adaptation, supporting its applicability in different populations and emphasizing the importance of validating the DESQ for the Turkish context. Moreover, the statistically significant correlation and difference between the DESQ and PIUS according to the duration of exposure to digital screens constituted significant findings indicating the applicability of the scale. For a questionnaire designed in another language to be used in a specific country (with a different language or culture), it must undergo a rigorous translation, cultural adaptation, and validation process in the target language [25, 26]. The Turkish version of the DESQ, which involves a rigorous process with systematic steps to perform translation and cultural adaptation, has shown that it is a manageable, comprehensible, and fast-to-administer measurement tool for the detection of symptoms of visual eye strain that may develop due to screen exposure in Türkiye.

One of the most critical elements in adapting a scale/survey from one culture to another is to evaluate the comprehensibility and measurement power of the scale/survey items in the target culture. According to the item analysis results of the items in the questionnaire, the item–total correlation values ranged between 0.306 and 0.517. In addition, the internal consistency coefficient (KR-20) obtained when each item was removed from the analysis separately ranged between 0.762 and 0.787, indicating that the questionnaire items were consistent and compatible. This situation reveals that individuals can correctly understand the questionnaire items and can effectively measure the situation they want to measure. In the literature, item–total correlation values above 0.300 indicate that the items contribute to the scale/survey. An internal consistency coefficient above 0.700 indicates that the scale's reliability is acceptable [24, 27]. These findings support that the questionnaire was successfully adapted to the target culture. The fit indices obtained according to the results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) show that the model is valid at a good level and that the fit indices of the individuals are statistically significant (χ2/sd = 2.607; GFI = 0.964; RMSEA = 0.063; CFI = 0.935; NFI = 0.900). In the literature, a chi-square fit test (χ2/sd) ratio of less than 3 indicates a good fit. Moreover, GFI and CFI values of 0.90 and above are accepted as essential criteria supporting the fit of the model [28, 29] In addition, an RMSEA value less than 0.08 is considered a good model fit, and the result of 0.063 is within the recommended limits [30]. The NFI and RFI values of 0.900 and 0.875, respectively, indicate that the model is adequate in terms of overall fit. These findings confirm the construct validity of the questionnaire and show that the scale statistically supports the targeted factor structure. In parallel with the literature, the CFA results have critical importance in terms of validity and reliability in scale/survey development studies. The correlation results between the DESQ and PIUS mean scores indicate statistically significant relationships between the total and subscale mean scores of the questionnaire and the scale. This result reveals that digital device use is interrelated in terms of both physical effects (e.g., eye strain) and behavioral and psychological effects (e.g., problematic internet use). In the literature, similar results have been reported in studies where digital eye strain and problematic internet use were considered together. For example, Samaha and Hawi (2016) emphasized that increased problematic internet use can lead to physical and psychological problems in individuals by prolonging the duration of digital device use [21]. Similarly, King et al. [13] reported that prolonged screen exposure increases symptoms of digital eye strain, which may strengthen individuals' tendency toward internet addiction.

These results suggest that digital eye strain and problematic internet use are interrelated and that excessive use of digital devices has multidimensional effects on individuals' overall health and quality of life. Hence, the collinearity with the literature suggests that the questionnaire accurately measures culture-specific measurements.

One of the most essential methods showing the applicability of the scales/survey is the presence of a significant relationship between the factors that may be related to the scale/survey scores. In this context, there is expected to be a statistical correlation between scale scores and subscale mean scores according to the time spent and liking of playing digital games. In the literature, Mohan et al. [30] reported that using devices for 5 h or more was associated with a significantly increased risk of DES (p = 0.0007). Several studies have reported that the DES prevalence is greater in participants who use digital devices for 4 h or more per day [1, 4]. In other studies, using digital devices for more than 2 h per day has been associated with a higher DES prevalence among adolescents [3, 30, 31]. A study on university students revealed an association between DES symptoms and daily digital device usage time and reported that 93.9% of students who spent 6 h or more using digital devices suffered from DES [1]. One of the most important indicators for assessing the validity and reliability of the scales is that the scale scores show significant relationships with related factors. Consistent findings in the literature that digital device usage time and digital gaming habits increase the risk of DES support that these measurement domains can be reliably assessed through studies [1, 7, 30]. These findings confirm the power of the questionnaire to measure the targeted phenomenon and provide a strong basis for the validity and reliability of the questionnaire by emphasizing its correlation with concordant factors.

Limitations

The study population was limited to individuals who regularly use digital screens for at least two hours daily and reside primarily in urban areas. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with less or more diverse digital screen exposure. Data collection was based on self-reports, which may introduce biases related to memory accuracy or social desirability effects. The another limitation of the study is the absence of ophthalmologists or optometrists among the research team; nonetheless, expert consultation was incorporated during the content validation phase to enhance the instrument’s clinical credibility.

Conclusion

The research results suggest that the Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ) can be used to reliably measure the signs and symptoms of digital eye strain in clinical populations presenting with eye problems or excessive use of gaming and screen-enabled devices in general. Together with the influence of gender, age, and gaming addiction, time spent with a screen-enabled device, in general, has been confirmed to be a significant risk factor for the development of symptoms associated with digital eye strain. Therefore, the importance of asking questions about the use of these devices when encountering nonspecific eye problems will reveal the scale's functionality, which can be used in the evaluation of individuals with eye-related problems, as well as in the evaluation of healthy/sick individuals and screening programs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the expert team members who contributed to the linguistic and content validation of the Turkish version of the Digital Eye Strain Questionnaire (DESQ).

Authors’ contributions

Gülsün Özdemir Aydın: Methodology; Semiha Küçükaydınoğlu: Data collection, formal analysis, Tuba Çömez İkican: Conceptualization, supervision; Nuray Turan: Writing-review and editing. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific funding from governments and organizations.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of Social Sciences and Humanities Research at Istanbul University. This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gammoh Y. Digital eye strain and its risk factors among a university student population in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e13575. 10.7759/cureus.13575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altalhi A, Khayyat W, Khojah O, Alsalmi M, Almarzouki H. Computer vision syndrome among health sciences students in Saudi Arabia: prevalence and risk factors. Cureus. 2020;12:e7060. 10.7759/cureus.7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Artime-Ríos E, Suárez-Sánchez A, Sánchez-Lasheras F, Seguí-Crespo M. Computer vision syndrome in healthcare workers using video display terminals: an exploration of the risk factors. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:2095–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdănici CM, Săndulache DE, Nechita CA. Eyesight quality and computer vision syndrome. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2017;61:112–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alemayehu A, Alemayehu MM. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of computer vision syndrome and its prevention. World J Ophthalmol Vis Res. 2019;2:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anbesu EW, Lema AK. Prevalence of computer vision syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Liang M, Wang C, Rizzo A. Prevalence of visual symptoms and eye strain among university students in Southeast Asia. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41(4):219–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahar NK, Sheedy JE, Hayes J, Tai YC. Objective measures of lower-level visual stress. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(7):620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mylona I, Glynatsis MN, Dermenoudi M, Glynatsis NM, Floros GD. Validation of the digital eye strain questionnaire and pilot application to online gaming addicts. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32(5):2695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boadi-Kusi SB, Abu SL, Acheampong GO, Adueming POW, Abu EK. Association between poor ergophthalmologic practices and computer vision syndrome among university administrative staff in Ghana. J Environ Public Health. 2020;2020(1):7516357. 10.1155/2020/7516357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winwood PC, Winefield AH, Dawson D, et al. Development and validation of a scale to measure work-related fatigue and recovery: The Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion/Recovery Scale (OFER). J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(6):594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winwood PC, Winefield AH, Lushington K. Work-related fatigue and recovery: the contribution of age, domestic responsibilities and shiftwork. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(4):438–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King DL, Delfabbro PH, Billieux J, Potenza MN. Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behav Addict. 2020;9(2):184–6. 10.1556/2006.2020.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghannam AB, Ibrahim H, Mansour H, Kheir WJ, Al Hassan S, Saade JS. Impact of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic on digital device related ocular health. Heliyon. 2024;10(12):e33039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almahmoud OH, Mahmmod KM, Mohtaseb SA, Totah NJ, Nijem DFA, Hammoudeh AN. Assessment of digital eye strain and its associated factors among school children in Palestine. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025;25(1):81. 10.1186/s12886-025-03919-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaacob NSM, Abdullah AM, Azmi A. Prevalence of Computer Vision Syndrome (CVS) Among Undergraduate Students of a Health-related Faculty in a Public University. Malaysian Mal J Med Health Sci. 2022;18(SUPP8):348–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koç Z, Keskin Kızıltepe S, Çınarlı T, Şener A. The use of theory in nursing practice, research, management, and education. Koç Univ J Nurs Educ Res. 2017;14(1):62–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Çapık C. İstatistiksel güç analizi ve hemşirelik araştırmalarında kullanımı: temel bilgiler. J Anatolia Nurs Health Sci. 2014;17(4):268–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(1):84–99. 10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Göktaş S, Aygar H, Zencirci SA, Önsüz MF, Alaiye M, Metintaş S. Problematic Internet Uses Questionnaire-Short Form-6 (PIUQ-SF 6): a validity and reliability study in Turkey. Int J Res Med Sci. 2018;6(7):2354–60. 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20182816. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samaha M, Hawi NS. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Comput Human Behav. 2016;57:321–5. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.045. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceyhan E, Ceyhan AA. An investigation of problematic internet usage behaviors on Turkish university students. Paper presented at: International Educational Technology Conference (IETC); 2007; Nicosia, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Available from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED500186.pdf.

- 23.Ceyhan E. A risk factor for adolescent mental health: Internet addiction. Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2008;15(2):109–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramada-Rodilla JM, Serra-Pujadas C, Delclós-Clanchet GL. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of health questionnaires: revision and methodological recommendations. Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55(1):57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tavşancıl E. Measurement of attitudes and data analysis with SPSS. 3rd ed. Ankara: Nobel Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. London: SAGE Publications; 1993. p. 136–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohan A, Sen P, Shah C, Jain E, Jain S. Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital Eye Strain among Kids (DESK study-1). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(1):140–4. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2535_205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichhpujani P, Singh RB, Foulsham W, Thakur S, Lamba AS. Visual implications of digital device usage in school children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(76):2–8. 10.1186/s12886-019-1082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.