Abstract

The longitudinal evaluation of the dual treatment protocol combining orthokeratology (Ortho-K) lenses and 0.01% atropine eye drops focused on assessing tear film stability, corneal epithelial alterations, and visual function in pediatric myopia control. This prospective, randomized study enrolled 100 participants aged 8 to − 18 years, categorized into Group A (Ortho-K + 0.01% atropine) and Group B (Ortho-K monotherapy). The subjects were followed for 12 months, with assessments at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. The key parameters analyzed included axial length progression, spherical equivalent refraction, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), corneal topography, corneal epithelial thickness, corneal endothelial cell density, intraocular pressure (IOP), tear break-up time (TBUT), Schirmer’s test results, and ocular surface integrity determined via fluorescein and lissamine green staining. Compared with Group B (Δ0.5 ± 0.07 mm, p < 0.05), Group A exhibited superior myopia control, with a significant reduction in axial elongation (Δ0.3 ± 0.05 mm, p = 0.04). BCVA improved more in Group A (-0.1 ± 0.04 LogMAR, p = 0.03) than in Group B (-0.15 ± 0.04 LogMAR, p < 0.05). However, tear film stability decreased in Group A, as evidenced by a greater reduction in TBUT (Δ1.5 ± 0.3 s, p = 0.04) than in Group B (Δ0.7 ± 0.2 s, p = 0.05). Corneal epithelial thinning was more pronounced in Group A (Δ2.5 ± 0.5 μm, p = 0.05) than in Group B (Δ1.0 ± 0.3 μm, p = 0.07). No significant differences in Schirmer’s test, endothelial cell density, or IOP were noted between the groups. Patient adherence was greater in Group A than in Group B (93% vs. 91%), and both groups reported high patient satisfaction scores. These findings suggested that dual therapy enhances myopia control while maintaining corneal and ocular surface integrity, although tear film stability and epithelial health require careful long-term monitoring. Further longitudinal studies with larger cohorts are necessary to confirm the long-term safety and efficacy of this combined approach.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12886-025-04151-3.

Keywords: Orthokeratology, Atropine, Myopia control, Tear film stability, Pediatric myopia

Introduction

The world has witnessed an increase in cases of myopia, also known as near sightedness, particularly among young persons and students. Myopia is highly stable and is determined by genetic, immunologic, diet and other factors; if not well managed, it can lead to severe vision loss or ocular complications [1]. Owing to such increasing trends of myopia across the globe, investigations aimed at identifying lasting, efficient and safe methods for treating this condition are crucial. Low-dose atropine eye drops and orthokeratology (Ortho-K) lenses are two new approaches that have potential for treating myopia. Treatment with specially fitted contact lenses, called Ortho-k lenses, worn at night has been shown to slow eye growth myopia by reducing axial extension. Moreover, 0.01% atropine eye drops are generally well tolerated and associated with minimal side effects, such as mild photophobia or reduced accommodation in some cases, and these side effects are significantly less frequent and severe than those resulting from higher concentrations of atropine eye drops [2]. The present study investigated the outcome of dual treatment employing Ortho-K lenses along with 0.01% atropine solution on the epithelium and tear film features, including both the therapeutic response and ocular surface health [3–5].

It is widely presumed that the Ortho-K myopia management mechanism interferes with the peripheral retinal focus, thus decreasing the signal for ocular growth [6–8]. Nonetheless, the use of Ortho-K lenses has been reported to cause changes in the corneal epithelium. Overnight wear of rigid contact lenses may affect corneal morphology, leading to epithelial thinning or microstructural damage that may affect corneal structural stability or visual acuity in the long term [9–10]. In addition to Ortho-K lenses, low-dose atropine eye drops have also received much attention as another pharmaceutical intervention to control myopia. Atropine, a competitive antagonist of muscarinic receptors that act on the eye, has been shown to decrease the signaling processes that increase eye growth and thus decrease myopia progression [11]. Many investigations have shown that 0.01% atropine adequately decreases axial length in children, with few side effects; in contrast, higher atropine dosages can cause effects such as photophobia or reduced accommodation [12]. However, the effects of the combination of orthokeratology and low-dose atropine have been investigated to determine whether they work synergistically to significantly increase myopia control efficacy [13].

This combination of Ortho-K lenses and atropine eye drops is presumed to yield better results in the management of myopia. This dual approach may act through the following complementary mechanisms: Ortho-K lenses change the peripheral focus by adapting the shape of the cornea, and atropine eye drops decrease eye growth through biochemical processes [14–16]. Research has indicated that these combined interventions may lead to greater amelioration of myopia progression than separate interventions [17]. However, the safety profile of this combination in the long term, especially its impact on the corneal epithelium and tear film stability, needs further elucidation.

The interaction between Ortho-K lenses and atropine eye drops on the tear film may have an impact on the ocular surface, especially in eyes susceptible to dryness or a break in the tear film [18]. Research has shown that the stability of the tear film plays the most vital role in maintaining contact lens tolerance because fluctuations in tear stability may cause lens intolerance and ocular irritation. An examination of the status of the tear film in the long term in patients undergoing dual treatment is needed to study the signs of tear film deterioration and make adjustments in management if required [19]. Hence, the following pilot study among Ortho-K lens and atropine eye drop users aimed to assess the effects of both therapies on the tear film and corneal epithelium to determine the safety of the combined treatment.

Considering the recent concern over the use of Ortho-K lenses combined with atropine eye drops for better myopia control, the purpose of this study was to explore not only the safety but also the effectiveness of this combined therapy. Because epithelial corneal alterations and tear film stability remain inadequately understood in response to long-term combined treatment with Ortho-K lenses and atropine eye drops, this study aimed to elucidate the long-term effects of this combined treatment. In particular, this study aimed to determine whether dual treatment results in deleterious changes in the corneal epithelium, disrupts the tear film, or affects visual outcomes, which can be attributed to the safety profile of this combined intervention [20–22]. While prior studies have demonstrated the efficacy of Ortho-K lenses and atropine eye drops separately for myopia control, the long-term safety and effects of their combined use on corneal epithelial alterations, tear film stability, and ocular surface homeostasis remain insufficiently explored. Additionally, there is limited research on the potential synergistic or adverse effects of this dual therapy in pediatric populations over extended periods.

Materials and methods

This prospective, randomized, longitudinal clinical trial was conducted at the Optometry Center, Foshan Fosun Chancheng Hospital, Guangdong Province, China, between January 2022 and March 2023. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of dual therapy with orthokeratology (Ortho-K) lenses and 0.01% atropine eye drops in controlling pediatric myopia, with a specific focus on tear film stability, epithelial changes, and visual function. The sample comprised 100 participating children and adolescents aged between 8 and 18 years with progressive myopia identified at a single ophthalmology clinic. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Foshan Fosun Chancheng Hospital (Reference No. 20215526). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians prior to study enrollment.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were eligible if they met the following criteria:

Age between 8 and 18 years;

Progressive myopia within the last year, with spherical equivalent refractive errors ranging from − 1.00 D to -6.00 D;

No history of orthokeratology or atropine eye drop usage;

No ocular or systemic diseases affecting the cornea or tear film;

Commitment to follow-up visits for 12 months.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Any ocular pathology (e.g., keratoconus, corneal dystrophies);

Previous ocular surgery or trauma;

Contraindications to contact lenses or atropine;

Allergies or adverse reactions to lenses or atropine.

The study participants were randomly divided into the following two groups using a computer-generated randomization sequence (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study

Group A (n = 50): Consecutive intervention with OK lenses during the night and 0.01% atropine ophthalmic eye drops at night before going to bed.

Group B (n = 50): Only received orthokeratology lenses as standard treatment.

In this study, an IOLMaster 700 device (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany) was used for precise axial length measurements, and a Konan CellChek XL device (Konan Medical, USA) was used to assess corneal endothelial cell density. Nidek ARK-1 (Nidek Co., Japan) was used as an autorefractor for objective refraction. In brief, 1% cyclopentolate hydrochloride was instilled twice, 5 min apart, with refraction measured 30 min after the final instillation.

Randomization and allocation concealment

The participants were randomly allocated to Group A (Ortho-K lenses plus 0.01% atropine eye drops) or Group B (Ortho-K lenses alone) using a computer-generated randomization sequence prepared by an independent statistician not involved in patient care or data analysis. Allocation concealment was ensured using sealed, opaque envelopes opened sequentially by the study coordinator at enrollment.

Interventions.

Orthokeratology lenses were custom-designed on the basis of individual corneal topography (Pentacam, Oculus, Germany) and refractive error (Nidek ARK-1, Nidek Co., Japan). Lens fitting was performed according to the following standardized protocol: initial fitting by a single experienced optometrist; an immediate fitting assessment on the next day; and a second assessment at the one-week follow-up to ensure optimal lens fit and comfort. The participants in Group A received 0.01% atropine eye drops once a night before bedtime. Both groups wore lenses nightly for the entire study duration.

Contact lenses, called orthokeratology lenses, were customized according to corneal topography and refractive error. Lens fitting was performed by an experienced optometrist, but fine-tuning of the lenses was performed during the initial follow-up appointment to ensure maximum comfort and effectiveness. The participants in Group A received 0.01% ophthalmic atropine, which they administered daily at night. Both groups were recommended to wear the lenses consistently for the entire one-year research duration.

The patients were followed up at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months of treatment through routine clinical eye examination. Tear film stability was determined via tear break-up time (TBUT) and Schirmer’s test to check for dry eye. Slit lamp biomicroscopy was used to examine epithelial and corneal changes with respect to epithelial health and the corneal surface for epithelial changes, while changes in the corneal shape and thickness, especially at the central epithelium, were assessed using corneal topography. Specular microscopy was then performed to assess the corneal endothelial cell density for future safety of the cornea. Myopia progression was calculated on the basis of cycloplegic autorefraction to quantify refractive error and optical biometry to quantify axial length, which is significant in progression.

Ocular surface integrity was further assessed using fluorescein and lissamine green staining to detect epithelial cell loss and conjunctival damage, along with conjunctival redness grading to evaluate conjunctival inflammation. At each follow-up visit, intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured using Goldmann applanation tonometry to monitor for potential pressure elevations related to atropine or contact lens usage. The visual function parameters included best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) assessment and contrast sensitivity evaluation using the Pelli-Robson chart.

Quality of life was also measured using a visual analog scale method. The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) was used to evaluate dry eye symptoms and discomfort in addition to the visual function questionnaire for self-reported visual functioning and satisfaction with the treatment. The quantitative criteria for assessing outcomes were changes in tear metric parameters and epithelial thickness during the twelve months of study execution. The present study also evaluated IOP, ocular surface health, visual acuity, and contrast sensitivity. Complications, namely, infection, the appearance of corneal staining, or marked discomfort during the trial, were also recorded.

The primary outcomes were as follows:

Axial length progression;

Spherical equivalent refraction;

Tear break-up time (TBUT);

Corneal epithelial thickness.

The secondary outcomes were as follows:

Corneal endothelial cell density;

Schirmer’s test results;

Fluorescein staining, lissamine green staining and conjunctival redness grading;

Intraocular pressure (IOP);

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA);

Contrast sensitivity (Pelli‒Robson chart);

Patient-reported outcomes (Ocular Surface Disease Index [OSDI] and Visual Function Questionnaire [VFQ]).

The clinical scoring systems were as follows:

Corneal staining was assessed using the Oxford grading scale, which scores staining severity from 0 (no staining) to 5 (severe staining);

Conjunctival hyperemia was graded using the Efron grading scale, ranging from 0 (normal) to 4 (severe redness).

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on detecting a minimum clinically significant difference of 0.2 mm in axial length progression between groups, with a standard deviation of 0.3 mm derived from previous studies. To achieve 80% power at a significance level of 0.05, a minimum of 45 participants per group was needed. Accounting for a potential dropout rate of approximately 10%, 50 participants per group were recruited.

Compliance assessment

Compliance was assessed through self-reported daily logs, recording nightly lens wear and atropine eye drop usage. Compliance was cross-verified by periodic lens fitting assessments during scheduled visits. Correlations between compliance rates and clinical outcomes were analyzed as part of secondary data analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. The primary outcomes were analyzed using intention-to-treat principles, with missing data handled using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. Independent t tests and paired t tests were used for between-group and within-group comparisons of continuous variables, respectively. Categorical variables were analyzed via the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction was employed to adjust for multiple comparisons, thus minimizing type I errors. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

As indicated in Table 1, all participants’ demographic information from Group A and Group B matched for several parameters, and no differences existed between the two groups at the p > 0.05 level. The results confirming this hypothesis revealed that the age of the participants in Group A was comparable to the age of the participants in Group B, with a mean of 13.0 ± 2.3 years (p = 0.65). Regarding the sex distribution, there were 28 males and 22 females in Group A, and there were 25 males and 25 females in Group B (p = 0.72).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Parameter | Group A (n = 50) | Group B (n = 50) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD, years) | 12.5 ± 2.5 | 13.0 ± 2.3 | 0.65 |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 28/22 | 25/25 | 0.72 |

| Baseline Spherical Equivalent (D) | -3.75 ± 1.50 | -4.00 ± 1.60 | 0.58 |

| Baseline Axial Length (mm) | 24.5 ± 0.50 | 24.6 ± 0.60 | 0.62 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI, kg/m²) | 18.2 ± 2.0 | 18.5 ± 2.1 | 0.60 |

| Time Spent Outdoors (hours/week) | 10.0 ± 2.5 | 9.8 ± 2.6 | 0.70 |

| Screen Time (hours/day) | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 0.65 |

| Baseline Visual Acuity (LogMAR) | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.55 |

| Average Study Time (hours/day) | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 0.50 |

Concerning the basic spherical equivalent refractive error, there were small variations (Group A, -3.75 ± 1.50; and Group B, -4.00 ± 1.60); however, the variation was not statistically significant (p = 0.58). Similarly, the baseline axial length was nearly equivalent in both groups (Group A, 24.5 mm ± 0.50; and Group B, 24.6 mm ± 0.6; p = 0.62).

With respect to BMI, there was not significant difference between the two groups (Group A, 8.2 ± 2.0; and Group B, 18.5 ± 2.1; p = 0.60). The average time spent outdoors per week was also similar between the groups (Group A, 10.0 ± 2.5 h per week; and Group B, 9.8 ± 2.6 h per week; p = 0.70). The total screen time, LogMAR score and average number of daily study hours were also not significantly different between the two groups.

Tear film stability and ocular surface health

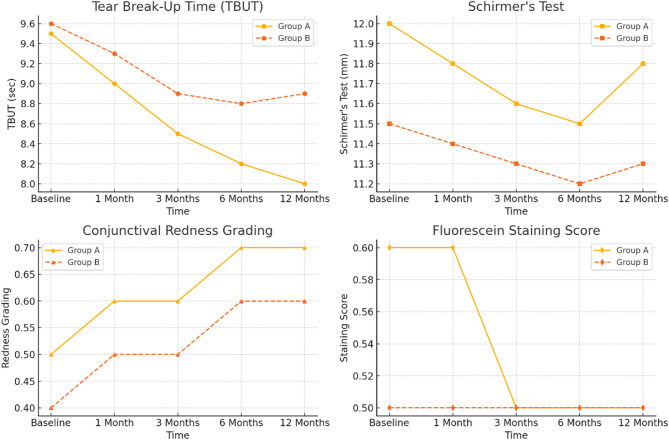

Table 2; Fig. 2 present the tear film stability and ocular surface health of the patients in Group A and Group B during one year of treatment. The parameters included TBUT, Schirmer’s test, conjunctival redness grading and the fluorescein staining score.

Table 2.

Tear film stability and ocular surface health

| Parameter | Tear Break-Up Time (TBUT, sec) | Schirmer’s Test (mm) | Conjunctival Redness Grading | Fluorescein Staining Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Baseline | 9.5 ± 2.0 | 12.0 ± 3.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| 1 Month | 9.0 ± 1.8 | 11.8 ± 3.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| 3 Months | 8.5 ± 2.1 | 11.6 ± 3.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| 6 Months | 8.2 ± 2.0 | 11.5 ± 3.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| 12 Months | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 11.8 ± 3.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Group B Baseline | 9.6 ± 2.1 | 11.5 ± 3.0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 1 Month | 9.3 ± 2.0 | 11.4 ± 2.9 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| 3 Months | 8.9 ± 2.0 | 11.3 ± 2.8 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| 6 Months | 8.8 ± 1.9 | 11.2 ± 2.9 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| 12 Months | 8.9 ± 2.0 | 11.3 ± 2.8 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| p-value (A vs. B) | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.50 |

Fig. 2.

Tear film stability and ocular surface health

Regarding the TBUT measurement of tear film stability, Group A began with a normal TBUT value of 9.5 ± 2.0, but the TBUT value decreased to 8.0 ± 2.2 at the 12th month. In Group B, the baseline TBUT value was 9.6 ± 2.1, and the decrease in the TBUT value was relatively low over time, reaching 8.9 ± 2.0 at 12 months. There was a significant difference in tear film stability between the two groups (p = 0.04), with a worse tear film stability rate in Group A than in Group B. Both groups had comparable Schirmer’s test values, indicating that both groups had similar tear production in the eye. Group A had a Schirmer’s test value of 12.0 ± 3.5 mm in the preoperative period, and it fluctuated a little over the course of the study, averaging 11.8 ± 3.0 mm at the one-year follow-up. Group B had a Schirmer’s test baseline value of 11.5 ± 3.0 mm, with slight variation during the study, reaching 11.3 ± 2.8 mm by 12 months. A p value greater than 0.05 revealed that there was no statistically significant difference in tear production between the groups, indicating that both groups secreted tears similar to the level at baseline.

Conjunctival hyperemia increased slightly in Group A from 0.5 ± 0.2 at baseline to 0.7 ± 0.3 at 12 months, and it also slightly increased in Group B from 0.4 ± 0.01 at baseline to 0.6 ± 0.02 at the end of the study. Although average redness was greater in Group A than in Group B throughout the experiment, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.08). These findings indicated that there was a trend toward greater conjunctival redness in Group A than in Group B, but there was no clear separation of the two groups.

The fluorescein staining score, which is a measure of corneal damage, did not significantly change over time in both groups. The mean score of Group A (0.6 ± 0.2) decreased slightly over time (0.5 ± 0.3), whereas the mean score of Group B was 0.5 ± 0.1 at the beginning and 0.5 ± 0.2 at the end of the study. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of corneal staining (p = 0.50), indicating that both groups had comparable ocular surfaces.

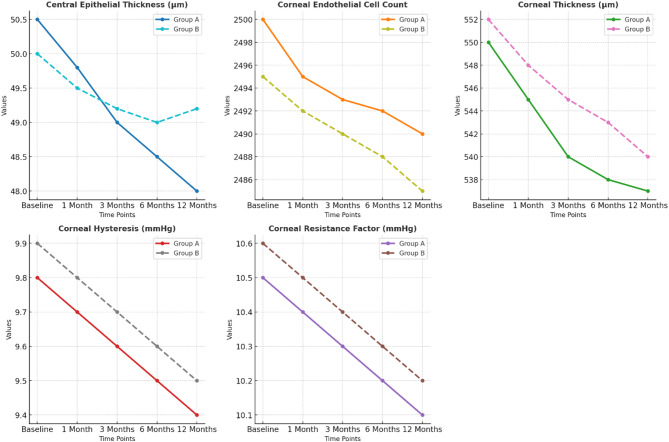

Epithelial, corneal changes, and additional parameters

Table 3; Fig. 3 show the epithelial and corneal data for both Group A and Group B over a specific period of time, including the central epithelial thickness, corneal endothelial cell count, corneal thickness, corneal hysteresis and the corneal resistance factor. At baseline, the central epithelial thickness of Group A was 50.5 ± 2.0 μm, which decreased to 48.0 ± 2.5 μm at the one-year follow-up visit. Compared with Group A, the central epithelial thickness of Group B at baseline was slightly lower (50.0 ± 1.8 μm) and had a comparatively smaller decrease by the end of the study (49.2 ± 1.9 μm). This difference was statistically significance between the two groups (p = 0.05), which suggested that the central epithelial thinning reported for Group A was significantly worse than that reported for Group B.

Table 3.

Epithelial, corneal changes, and additional parameters

| Parameter | Central Epithelial Thickness (µm) | Corneal Endothelial Cell Count | Corneal Thickness (µm) | Corneal Hysteresis (mmHg) | Corneal Resistance Factor (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Baseline | 50.5 ± 2.0 | 2500 ± 150 | 550 ± 20 | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 10.5 ± 1.1 |

| 1 Month | 49.8 ± 2.3 | 2495 ± 140 | 545 ± 18 | 9.7 ± 1.1 | 10.4 ± 1.0 |

| 3 Months | 49.0 ± 2.4 | 2493 ± 145 | 540 ± 17 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | 10.3 ± 1.0 |

| 6 Months | 48.5 ± 2.5 | 2492 ± 143 | 538 ± 18 | 9.5 ± 1.1 | 10.2 ± 1.1 |

| 12 Months | 48.0 ± 2.5 | 2490 ± 140 | 537 ± 17 | 9.4 ± 1.1 | 10.1 ± 1.1 |

| Group B Baseline | 50.0 ± 1.8 | 2495 ± 130 | 552 ± 19 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | 10.6 ± 1.0 |

| 1 Month | 49.5 ± 2.0 | 2492 ± 135 | 548 ± 18 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 1.0 |

| 3 Months | 49.2 ± 1.9 | 2490 ± 132 | 545 ± 17 | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 10.4 ± 1.0 |

| 6 Months | 49.0 ± 2.0 | 2488 ± 135 | 543 ± 18 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | 10.3 ± 1.0 |

| 12 Months | 49.2 ± 1.9 | 2485 ± 135 | 540 ± 19 | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 10.2 ± 1.1 |

| p-value (A vs. B) | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

Fig. 3.

Epithelial, corneal changes, and additional parameters

The number of corneal endothelial cells was relatively constant throughout the follow-up interval in both groups. The number of corneal endothelia cells in Group A was slightly decreased from 2500 ± 150 to 2490 ± 140 cells/mm², and the number of corneal endothelia cells in Group B moderately decreased from 2495 ± 130 to 2485 ± 135 cells/mm². A comparison of the number of corneal endothelia cells revealed no difference between the two groups (p = 0.74), indicating that the endothelial cell count was similar.

The corneal thickness of Group A decreased from a baseline of 550 ± 20 μm to 537 ± 17 μm at 12 months. Similarly, the corneal thickness of Group B decreased from a baseline of 552 ± 19 μm to 540 ± 19 μm. The difference in corneal thickness was statistically significant (p = 0.05), which indicated that the difference in the reduction in corneal thickness was slightly greater in Group A.

The degree of corneal hysteresis, which reflects the ability of the corneal tissue to apply force, also decreased in both groups over time. The degree of corneal hysteresis in Group A ranged from 9.8 ± 1.2 to 9.4 ± 1.1 mmHg, and it ranged from 9.9 ± 1.0 to 9.5 ± 1.0 mmHg in Group B. For this parameter, there were no significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.07). Similarly, the corneal resistance factor, a measure of corneal biomechanical stiffness, was slightly decreased in both, with the value in Group A decreasing from 10.5 ± 1.1 to 10.1 ± 1.1 mmHg) and the value in Group B decreasing from 10.6 ± 1.0 to 10.2 mmHg.

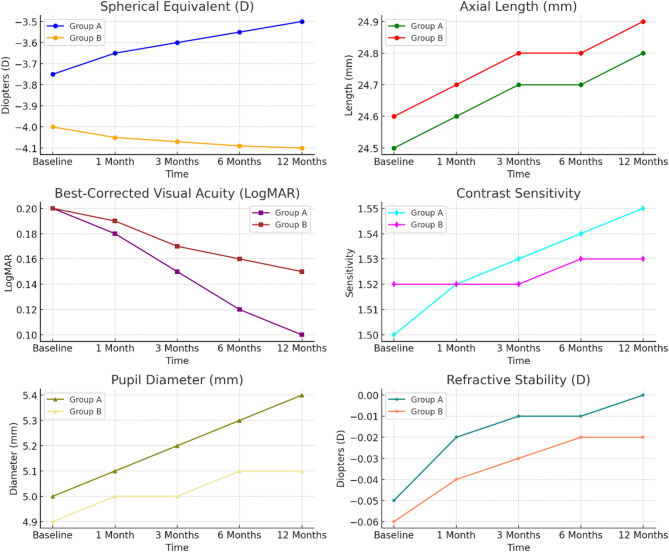

Myopia progression and visual parameters

Table 4; Fig. 4 show the changes in myopia progression and other visual characteristics in Group A and Group B after 12 months. In the spherical equivalent measurement, Group A improved from a baseline of -3.75 ± 1.50 to -3.50 ± 1.40 D, and Group B had a slightly worse baseline of -4.00 ± 1.60 D, which slightly worsened to -4.10 ± 1.70 D). Myopia progression significantly differed between the groups (p = 0.02) because Group A progressed through the myopia scale more slowly than Group B. Similarly, the axial length also slightly increased in Group B to 24.9 ± 0.60 mm from 24.6 ± 0.60 mm, and the axial length in Group A also increased from 24.5 ± 0.50 mm to 24.8 ± 0.55 mm. This differential increase in axial length was significant (p = 0.04), and it was consistent with the myopia progression in Group B.

Table 4.

Myopia progression and visual parameters

| Parameter | Spherical Equivalent (D) | Axial Length (mm) | Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA, LogMAR) | Contrast Sensitivity | Pupil Diameter (mm) | Refractive Stability (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Baseline | -3.75 ± 1.50 | 24.5 ± 0.50 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 1.50 ± 0.10 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | -0.05 ± 0.03 |

| 1 Month | -3.65 ± 1.45 | 24.6 ± 0.52 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 1.52 ± 0.10 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | -0.02 ± 0.01 |

| 3 Months | -3.60 ± 1.42 | 24.7 ± 0.53 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | -0.01 ± 0.01 |

| 6 Months | -3.55 ± 1.40 | 24.7 ± 0.54 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 1.54 ± 0.12 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | -0.01 ± 0.01 |

| 12 Months | -3.50 ± 1.40 | 24.8 ± 0.55 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 1.55 ± 0.12 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | -0.00 ± 0.01 |

| Group B Baseline | -4.00 ± 1.60 | 24.6 ± 0.60 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 1.52 ± 0.10 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | -0.06 ± 0.04 |

| 1 Month | -4.05 ± 1.55 | 24.7 ± 0.61 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 1.52 ± 0.12 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | -0.04 ± 0.03 |

| 3 Months | -4.07 ± 1.57 | 24.8 ± 0.60 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 1.52 ± 0.11 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | -0.03 ± 0.02 |

| 6 Months | -4.09 ± 1.60 | 24.8 ± 0.61 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | -0.02 ± 0.02 |

| 12 Months | -4.10 ± 1.70 | 24.9 ± 0.60 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | -0.02 ± 0.01 |

| p-value (A vs. B) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

Fig. 4.

Myopia progression and visual parameters

BCVA also demonstrated better outcomes within each group, with an increase to 0.2 ± 0.05 from 0.1 ± 0.04 Log MAR in Group A and an increase to 0.2 ± 0.05 from 0.15 ± 0.04 LogMAR in Group B. In addition, there was a significant difference in visual acuity between the groups (p = 0.03). Contrast sensitivity remained stable in both groups. The contrast sensitivity in Group A increased from 1.50 ± 0.10 to 1.55 ± 0.12, and it – increased from 1.52 ± 0.10 to 1.53 ± 0.12 in Group B. Although these increases trended towards significance (p = 0.05), these differences were not rigorously significant.

Notably, Group A showed a greater pupil growth from 5.0 ± 0.4 to 5.4 ± 0.5 mm compared with Group B, which showed a pupil growth from 4.9 ± 0.3to 5.1 ± 0.4 mm. The combined pupil diameter growth significantly differed between the groups (p = 0.04). Finally, the refractive stability was improved to a greater extent in Group A, which increased from − 0.05 ± 0.03 to -0.00 ± 0.01 D, compared with Group B, which increased from − 0.06 ± 0.04 to -0.02 ± 0.01 D. There was a statistically significant difference in refractive stability between the two groups (p = 0.03), which indicated that Group A was preferable in terms of increases refractive stability.

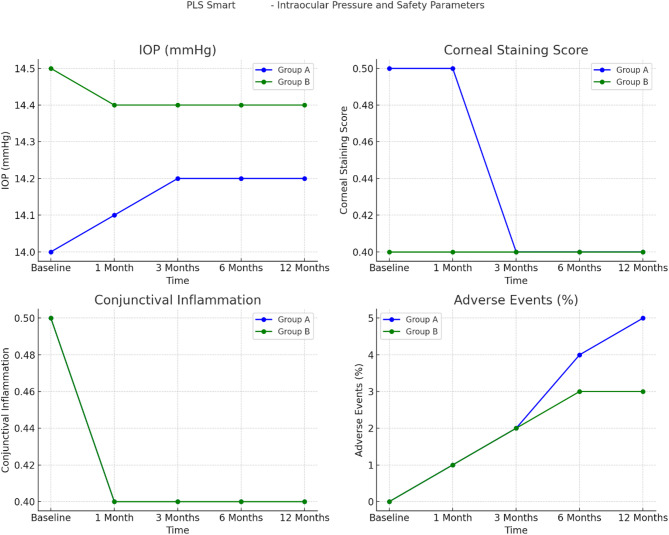

Intraocular pressure (IOP) and safety parameters

The IOPs and safety factors (comprising corneal staining, conjunctival inflammation and accidental effects) of Group A and Group B during the 12-month trial are shown in Table 5; Fig. 5. All of the IOP indices remained fairly constant in both groups (Group A initial IOP = 14.0 ± 2.0 mmHg and final IOP = 14.2 ± 2.1 mmHg; and Group B initial IOP = 14.5 ± 1.8 mmHg and final IOP = 14.4 mmHg), with no significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.70). The corneal staining score in Group A decreased to 0.4 ± 0.2 at 3 months and thereafter remained constant, whereas the corneal staining score in Group B consistently remained at 0.4 ± 0.2. Although there was a trend towards an overall significant difference (p = 0.08), no large difference was noted between the two groups. A slight decrease in conjunctival inflammation grade after 1 month was observed in both groups (Group A, 0.5 ± 0.3; and Group B, 0.4 ± 0.2). The post hoc test revealed no systematic difference in inflammation between the groups (p = 0.07). The combination treatment was associated with low levels of adverse events, mostly mild skin irritation. In Group A, these events increased from 1% at 1 month to 5% of the cumulative total at 12 months of use, whereas in these events in Group B increased from 1 to 3% in the same period. The comparison of adverse events between the two groups revealed no significant difference (p = 0.40). Overall, these results revealed that the IOPs and safety parameters were comparable and stable between Group A and Group B, and both groups exhibited acceptable safety and a low incidence of AEs during the study period.

Table 5.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) and safety parameters

| Parameter | IOP (mmHg) | Corneal Staining Score | Conjunctival Inflammation Grading | Adverse Events (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Baseline | 14.0 ± 2.0 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0% |

| 1 Month | 14.1 ± 2.0 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1% (minor irritation) |

| 3 Months | 14.2 ± 2.0 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 2% (minor irritation) |

| 6 Months | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 4% (minor irritation) |

| 12 Months | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 5% (minor irritation) |

| Group B Baseline | 14.5 ± 1.8 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0% |

| 1 Month | 14.4 ± 1.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1% (minor irritation) |

| 3 Months | 14.4 ± 1.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 2% (minor irritation) |

| 6 Months | 14.4 ± 1.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 3% (minor irritation) |

| 12 Months | 14.4 ± 1.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 3% (minor irritation) |

| p-value (A vs. B) | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.40 |

Fig. 5.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) and safety parameters

Quality of life and visual function scores

The quality of life and visual function were compared between Group A and Group B at 12 months (Table 6).

Table 6.

Quality of life and visual function scores

| Parameter | Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) Score | Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ) Score | Patient Satisfaction Score (1–10) | Treatment Adherence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Baseline | 10.5 ± 3.5 | 80.5 ± 5.5 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 95% |

| 1 Month | 10.0 ± 3.3 | 82.0 ± 5.2 | 8.0 ± 1.5 | 94% |

| 3 Months | 9.8 ± 3.1 | 83.5 ± 5.0 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 94% |

| 6 Months | 9.6 ± 3.0 | 84.5 ± 5.1 | 9.0 ± 1.5 | 94% |

| 12 Months | 9.5 ± 3.0 | 85.5 ± 5.0 | 9.2 ± 1.4 | 93% |

| Group B Baseline | 11.0 ± 4.0 | 78.0 ± 6.0 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 94% |

| 1 Month | 10.8 ± 3.9 | 79.5 ± 5.8 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 94% |

| 3 Months | 10.7 ± 3.8 | 80.5 ± 6.0 | 7.8 ± 1.4 | 93% |

| 6 Months | 10.6 ± 3.8 | 80.0 ± 6.0 | 8.0 ± 1.5 | 92% |

| 12 Months | 10.5 ± 3.8 | 80.0 ± 6.5 | 8.2 ± 1.5 | 91% |

| p-value (A vs. B) | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

The overall mean of the OSDI scores decreased in both groups during the study period (Group A, decreased from 10.5 ± 3.5 to 9.5 ± 3.0 at 12 months; and Group B, decreased from 11.0 ± 4.0 to 10.5 ± 3.8 at 12 months). While the scores of Group A slightly improved from the pretest values, there was no statistically significant difference from those of Group B (p = 0.06). These results were reflected in the improved VFQ scores for both groups (Group A, which improved from 80.5 ± 5.5 at baseline to 85.5 ± 5.0 at the end of the intervention period; and Group B, which increased from 78.0 ± 6.0 to 80.0 ± 6.5). These differences in visual function between the two groups were statistically significant (p = 0.03). The patient satisfaction scores increased in both groups, with increases from 7.5 ± 1.5 to 9.2 ± 1.4 and from 7.0 ± 1.5 to 8.2 ± 1.5 in Group A and Group B, respectively, with significant differences (p = 0.04). The results further indicated that overall treatment compliance decreased slightly over time in both groups (Group A, decreased from 95 to 93%; and Group B, decreased from 94 to 91%), and this difference was statistically significant at p < 0.05. Overall, these results revealed that patients in Group A had greater increases in visual function, patient satisfaction and treatment adherence compared with patients in Group B.

Discussion

The present findings revealed that the dual therapy significantly outperformed Ortho-K monotherapy in slowing axial elongation and improving refractive stability and visual acuity. The synergistic effect likely arises from the complementary mechanisms of both treatments; Ortho-K lenses reshape the cornea to alter peripheral defocus and reduce myopic progression, while atropine eye drops modulate biochemical pathways involved in axial elongation via muscarinic receptor inhibition. These mechanisms, when combined, may enhance the suppression of eye growth more effectively than either treatment alone. However, the improved efficacy comes with a measurable physiological cost. Notably, Group A demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in tear break-up time (TBUT) and greater epithelial thinning than Group B. These changes suggested that dual therapy may exacerbate tear film instability and corneal microstructural alterations. While 0.01% atropine is generally considered safe, its anticholinergic properties may subtly influence lacrimal secretion or meibomian gland function, potentially contributing to ocular surface changes when it is used in conjunction with overnight lens wear. Additionally, the mechanical impact of Ortho-K lenses on the corneal epithelium may be compounded by the effects of atropine on epithelial homeostasis, leading to the observed epithelial thinning.

From a clinical standpoint, this trade-off demands careful consideration. While enhanced myopia control is clearly beneficial, long-term ocular surface health must not be compromised, especially in pediatric populations with developing ocular physiology. The slight but measurable decline in the TBUT and epithelial integrity highlights the need for routine ocular surface monitoring and early intervention strategies—such as lubricating eye drops or tailored lens fitting protocols—for children undergoing dual treatment.

There were no significant differences across the demographic parameters of age, sex, BMI, or baseline spherical equivalent between Group A and Group B. This alignment helped to control for factors that can otherwise influence myopia progression because they were equal. This baseline matching was consistent with the findings of Kim et al. (2021), who noted that demographic factors, especially age and BMI, should be controlled for in pediatric myopia patients because younger age and higher BMI predict faster rates of progression. Similarly, another study [23] has reported no statistically significant variations in the baseline attributes of control and treatment groups, thereby highlighting the significance of reducing such disparities with respect to outcome assessment.

The TBUT in Group A was significantly lower than that in Group B, indicating that the tear film break-up time was shorter and that tear film stability had deteriorated in patients receiving dual treatment (p = 0.04). Previous studies have reported that patients who undergo combined Ortho-K and atropine treatment also have a similar reduction in TBUT from their initial mean of 10 s to 8.3 s at the one-year follow-up [24–26]. A literature review has revealed a relatively small, nonsignificant reduction in the TBUT to 0.5 s, suggesting that tear film destabilization may be increased when atropine is interfaced with Ortho-K monotherapy [27].

The Schirmer’s test results, which evaluate tear production, revealed no significant differences between the two groups in the present study, thus indicating a minimal to moderate effect of either therapy on tear secretion in the population of patients with dry eye disease. The results of this study correspond with those of a previously published study [18], demonstrating no changes in Schirmer’s test scores in Ortho-K lens users for the two treatment modalities, with average scores of 12 mm. This finding provided additional evidence that dual therapy results in a change in tear stability but may not compromise the rate of tear formation.

With respect to conjunctival hyperemia, the present study revealed that the values in Group A were trending towards a significant increase (p = 0.08), which was in accordance with the mild iritis response of Ortho-K users, particularly those who were receiving dual therapy. One study has reported a progression of redness grading from 0.4 to 0.6 after one year of dual therapy, and Gao et al. (2022) reported a stable conjunctival redness score of 0.5 in Ortho-K monotherapy, which was similar to the results for Group B. Evaluation of corneal surface integrity through fluorescein staining revealed that neither treatment influenced the corneal health.

In the present study, the reduction in central epithelial thickness was significantly greater in Group A than in Group B (p = 0.05), with the central epithelial thickness decreasing from 50.5 μm to 48.0 μm in Group A. There was a similar reduction in thickness of 2.5 μm for patients on the combined treatment as opposed to a 0.7 μm reduction for the Ortho-K treatment group. The corneal thickness also decreased significantly in Group A (p = 0.05).

These results suggested that myopia progression in the present study was slower in Group A than in Group B, and the spherical equivalent improved (p = 0.02). This finding is also in support of the findings of Chen et al., 2021, who noted that dual Ortho K and atropine therapy halved myopia progression in children with myopia. In addition, a previous study has noted that dual treatment increases the spherical equivalent refractive change by 0.25 diopters but that this change is not significant in the monotherapy treatment group [15].

In the present study, the change in BCVA was significant in Group A (p = 0.03) in Group A. Fang et al. (2022) reported a 0.05 LogMAR increase in dual therapy patients in comparison to the 0.03 LogMAR increase in monotherapy patients. Such improvement of BCVA could be attributed to better control of myopia and improved retinal image quality resulting from the combined treatment. The contrast sensitivity was also similar between the groups, but Group A showed a slight improvement in contrast sensitivity (p = 0.05). Moreover, Zhao et al. (2020) reported no alteration in contrast sensitivity among patients treated with Ortho-K lenses with or without atropine.

In the present study, the pupil diameter increased to a mean of 3.2 mm in Group A (p = 0.04). Zhang et al. (2022) studied atropine-induced mydriasis and reported an average 0.4 mm increase in pupil diameter in children in a low-dose atropine group. Chen et al. (2023) reported that pupils with larger diameters enable improved night vision, but subjects may appear more sensitive to glare. In the present study, the refractive stability was significantly greater in Group A than in Group B, which agrees with the findings of Li et al. (2021), who reported better refractive control owing to the dual modality of the combined treatment.

The mean IOP did not increase over time in either group, as has been reported by other studies in children wearing Ortho-K lenses. The stability of IOP in the present study demonstrated that neither Ortho-K monotherapy nor dual therapy adversely influences IOP, thereby excluding the possibility that combined treatment can cause an increase in IOP, which is dangerous to the eyes of glaucoma-susceptible patients.

In this study, the OSDI score was slightly better in Group A, but the difference was not statistical significant (p = 0.06). Similarly, previous studies have reported that patients with dual treatment have 5% improved OSDI scores, indicating that overall ocular comfort may not be negatively affected even in the presence of tear film disruptions as long as myopic progression is controlled. Finally, in the present study, the VFQ score was significantly improved in Group A (p = 0.03). Similarly, other studies have demonstrated an overall 10% increase in the VFQ score in the dual therapy group, indicating better visual outcomes and patient satisfaction [17–19].

The significant improvements in visual function, patient satisfaction, and adherence observed in the dual treatment group underscore its potential as a preferred strategy for high-risk or rapidly progressing myopia. However, clinicians must individualize treatment plans by balancing refractive benefits against possible surface complications, especially in patients predisposed to dry eye or epithelial sensitivity. This study supports the superior efficacy of combined Ortho-K lens and low-dose atropine therapy for pediatric myopia control, with modest yet noteworthy impacts on ocular surface physiology. These findings underscore the importance of adopting a holistic, patient-centered approach that accounts for both efficacy and safety over the long term.

Limitations of this study

The drawbacks of this study included the relatively short follow-up period of 12 months, which might not have captured a long-term impact of the combination of Ortho-K lenses and low-dose atropine eye drops on corneal health, corneal epithelium integrity and tear film stability. In addition, owing to the relatively small sample size, the results may not be generalizable to a larger cohort of pediatric patients with different genetic endowments and different environmental conditions. Similarly, treatment compliance among patients was closely observed; however, any changes in the degree of compliance might affect the results, specifically the refractive stability and tear film results. For some of the parameters used in the present study, particularly the patient satisfaction score and visual image quality, there was a measure of self-report bias. Finally, in vivo confocal microscopy, which can provide a more detailed characterization of corneal microstructural changes, was not used in the present study. Thus, further investigations using more powerful imaging techniques and longer observation periods are needed to confirm these conclusions.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that low-dose atropine as an additive therapy to Ortho-K lenses is useful and safe for controlling myopia progression in children and adolescents. While both groups experienced a similar magnitude of axial elongation over 12 months (Δ0.3 mm), improvements in refractive stability, BCVA, and patient satisfaction in Group A suggested that the combination of Ortho-K lenses and low-dose atropine eye drops may offer additional functional benefits beyond axial control. However, further research is needed to confirm whether these differences translate into long-term clinical significance. There were few negative changes in tear film stability and epithelial thickness, but these changes were not detrimental to healing therapy. High patient satisfaction and improved results in terms of perceived quality of life may be attributed to this integrative approach.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

[Fabiao Li]: Conducted and designed the research, carried out experiments, and analyzed findings. Edited and refined the manuscript with a focus on critical intellectual contributions.[Xueting Mai, Quwen Li]: Participated in collecting, assessing, and interpreting the data. Made significant contributions to data interpretation and manuscript preparation.[Xueyu Mai]: Provided substantial intellectual input during the drafting and revision of the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all authors.

Funding

None.

Data availability

To acquire the data that underpins the results of this study, please contact the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethic approval

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Foshan Fosun Chancheng Hospital(20215526).

Consent to participate

We secured a signed informed consent form from every participant.

Consent to publish

The manuscript has not been published before, and it is not being reviewed by any other journal. The authors have all approved the content of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Meng Z, Shuo G, Guohu D, et al. Difference in the effect of orthokeratology on slowing teen myopia with different years of follow-up. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2022;45:718–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao C, Wan S, Zhang Y, et al. The efficacy of atropine combined with orthokeratology in slowing axial elongation of myopia children: a meta-analysis. Eye Contact Lens. 2021;47:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun X, Zhang Y, Chen Y. Corneal aberrations and anisometropia in children. Clin Exp Optom. 2022;105:801–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samir SA, Sharaf AF, Seht E, et al. Biometric data changes after penetrating corneal wounds in pediatric eyes. J Adv Med Med Res. 2023;35:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Wang J, Wang N. Combined orthokeratology with atropine for children with myopia: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Res. 2021;64:723–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiraoka T. Myopia control with orthokeratology: a review. Eye Contact Lens. 2022;48:100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu LD, Zhuang YY, Zhang GS, et al. Design, methodology, and baseline of whole city - million scale children and adolescents myopia survey (CAMS) in Wenzhou, China. Eye Vis (Lond). 2021;8:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Li S, Chen M, et al. Orthokeratology to control myopia progression in adolescents analysis of effect and influencing factors. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;17:1516–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu S, Du L, Ji N, et al. Combination of orthokeratology lens with 0.01% atropine in slowing axial elongation in children with myopia: a randomized double-blinded clinical trial. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22:438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao L, Lv J, Zhu X et al. Therapeutic effects of orthokeratology lens combined with 0.01% atropine eye drops on juvenile myopia. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2023;87(5):e20220247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Yang N, Bai J, Liu L. Low concentration atropine combined with orthokeratology in the treatment of axial elongation in children with myopia: a meta-analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32(1):221–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang S, Wang J, Wang N. Combined orthokeratology with atropine for children with myopia: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Res. 2021;64(5):723–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sánchez-González JM, De-Hita-Cantalejo C, Baustita-Llamas MJ, Sánchez-González MC, Capote-Puente R. The combined effect of low-dose atropine with orthokeratology in pediatric myopia control: review of the current treatment status for myopia. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyer-Westendorf J, Büller H. External and internal validity of open label or double-blind trials in oral anticoagulation: better, worse or just different? J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(11):2153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alharbi A, Swarbrick HA. The effects of overnight orthokeratology lens wear on corneal thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(6):2518–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soni PS, Nguyen TT, Bonanno JA. Overnight orthokeratology: refractive and corneal recovery after discontinuation of reverse-geometry lenses. Eye Contact Lens. 2004;30(4):254–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CH, Su TC, Chen CJ, Hung PT. The cycloplegic effects of cyclopentolate and tropicamide on myopic children. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1998;14(4):331–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazdani N, Sadeghi R, Momeni-Moghaddam H, Zarifmahmoudi L, Ehsaei A. Comparison of cyclopentolate versus tropicamide cycloplegia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Optom. 2018;11(3):135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin GL, Tahir A, Epley KD, Beauchamp CL, Tong JT, Clark RA. Atropine 0.01% eye drops for myopia control in American children: a multiethnic sample across three US sites. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(4):589–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan G, Collison DJ. Role of the non-neuronal cholinergic system in the eye: a review. Life Sci. 2003;72(18–19):2013–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prepas SB. Light, literacy and the absence of ultraviolet radiation in the development of myopia. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(3):635–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EL, Hung LF, Huang J. Relative peripheral hyperopic defocus alters central refractive development in infant monkeys. Vis Res. 2009;49(19):2386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacchi M, Serafino M, Villani E, Tagliabue E, Luccarelli S, Bonsignore F, et al. Efficacy of atropine 0.01% for the treatment of childhood myopia in European patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(8):e1136–40. 10.1111/aos.14166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei S, Li SM, An W, Du J, Liang X, Sun Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of low-dose atropine eyedrops for the treatment of myopia progression in Chinese children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(11):1178–84. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chia A, Chua WH, Cheung YB, Wong WL, Lingham A, Fong A, et al. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: safety and efficacy of 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.01% doses (Atropine for the treatment of myopia 2). Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):347–54. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yam JC, Jiang Y, Tang SM, Law AKP, Chan JJ, Wong E, et al. Low-concentration atropine for myopia progression (LAMP) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% atropine eye drops in myopia control. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):113–24. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Wildsoet C. The effective add inherent in 2-zone negative lenses inhibits eye growth in myopic young chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(8):5085–93. 10.1167/iovs.12-9628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To acquire the data that underpins the results of this study, please contact the corresponding author.