Abstract

Formaldehyde has been used to control microbial contamination in commercial hatch cabinets. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effects of spray application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens solid state fermentation products on the microbial load in the hatch cabinet, pioneer colonization of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), and early performance compared to formaldehyde fumigation. An environmental challenge model was used to simulate the microbial bloom to compare the application of two B. amyloliquefaciens strains (MCR002, MCR009) to formaldehyde fumigation. Groups included 1) non-challenged control (NC), 2) challenged with pathogen mix (PM) containing Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus at DOE19, 3) PM + formaldehyde treated (PM+F), 4) PM + MCR002 (PM+MCR002), 5) PM + MCR009 (PM+MCR009), and 6) PM+MCR002+MCR009 (PM+Combo). All groups were evaluated in trial 1-3 except PM+Combo. Air samples were collected from the hatch cabinet environment on d20 of embryogenesis (DOE20) at ∼20, 50, 80 % hatch, and immediately prior to hatch pull at DOE21. GIT samples were collected for enumeration of relevant enteric bacteria at hatch (d0). Pen and feed weights were recorded at d0 and d7 for trial 1 and 2 and at d14 for trial 2 to assess BWG and FCR. In summary, there was a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in gram-negative bacterial recovery from the GIT for PM+F, PM+MCR002, and PM+MCR009 compared to PM while the two B. amyloliquefaciens treatments were similar to PM+F. Gram-negative bacteria and Enterococcus recovery from hatch cabinet air samples were significantly reduced in PM+F and PM+MCR002 compared to PM. No significant differences in performance were observed. Spray application of MCR002 or MCR009 alone shifted the microbial load in the hatch cabinet and in the GIT of chicks similar to PM + F without negatively affecting performance at d7 or 14. However, MCR002 was more effective. This suggests that MCR002 could be used to mitigate the microbial bloom during the hatching phase without impacting chick performance.

Keywords: Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Hatchery, Microbial bloom, Formaldehyde, Broiler

Introduction

Neonatal chicks have minimal to no exposure to the maternal microbiota when hatched in commercial poultry operations. Instead, the initial or pioneer colonizers of the gastrointestinal tract of commercially hatched chicks tend to be of environmental origin (Li et al., 2022). Large scale incubators and hatch cabinets utilized in commercial hatcheries provide optimal conditions (temperature, humidity) for microbial proliferation (Magwood, 1964; Sheldon and Brake, 1991). Bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp. (Olsen et al., 2012), and Staphylococcus spp. (Kense and Landman, 2011) are common opportunistic pathogens that have been recovered from commercial incubators and hatch cabinet environments. These potentially pathogenic bacteria can penetrate the eggshell through pores or microfractures in the eggshell and quickly proliferate in the nutrient rich environment within the egg (Karunarathna et al., 2020). In some cases, pressure associated with microbial replication within the egg may cause the egg to burst and disseminate the contaminated egg-derived material onto neighboring eggs (Karunarathna et al., 2020) often referred to as “exploders.” This process may also result in aerosolization of the contaminated material which is circulated throughout the incubator and hatch cabinet environments. This proliferation of microorganisms within the hatch cabinet is referred to as the microbial bloom. This bloom primarily occurs at the onset of hatch due to the rise in relative humidity associated with the hatching phase (Graham et al., 2022). As a result, commercial hatchery operations implement disinfection and sanitation practices in an attempt to control the microbial load in large scale incubators and hatch cabinets.

Formaldehyde fumigation has been regularly utilized to mitigate microbial bloom in the hatch cabinet (Depner et al., 2021). Formaldehyde is very effective at killing microorganisms however, it is a carcinogenic chemical (NIEHS, 2021) posing a health risk not only to hatchery workers but also possibly damaging the respiratory tract of newly hatched chicks (Sander et al., 1995; Maharjan et al., 2017), potentially increasing the risk of subsequent infection by an opportunistic pathogen. Formaldehyde kills bacteria indiscriminately resulting in the reduction of potentially beneficial bacteria. To mitigate human exposure to formaldehyde, common practice is for commercial hatcheries to stop formaldehyde fumigation 12 h prior to hatch pull to reduce human exposure levels (personal communication). As formaldehyde is a volatile chemical, it quickly evaporates, and levels subside once consistent application ceases. Any remaining microorganisms in the environment could rapidly proliferate once formaldehyde volatilization occurs. Moreover, formaldehyde does not appear to penetrate the eggshell effectively and likely has no effect on microbial load within the egg (Graham et al., 2021). There is a need for alternative methods besides formaldehyde fumigation to manage the microbial load during the hatching phase and to promote enteric colonization by beneficial pioneer colonizers in chicks hatched in commercial settings.

Alternatives to formaldehyde fumigation have typically included hydrogen peroxide (Scott et al., 1993; Sander and Wilson, 1999), ozone fumigation (Whistler and Sheldon, 1989), and hydrogen peroxide in combination with UV light (Wells et al., 2010; Gottselig et al., 2016). While some of these alternatives show similar microbial bloom control compared to formaldehyde, the administration of probiotics during late embryogenesis could also be used as a method to reduce the pathogen load in the hatch cabinet environment and alter enteric colonization pre- and post-hatch. This concept provides a unique opportunity to expose neonates to a beneficial microorganism as the pipping process begins. Additionally, a probiotic would ideally colonize the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of the chick and have lasting beneficial effects post-hatch at the farm whereas the chemical or physical methods would have little to no effect after hatch pull aside from reducing the environmental microbial load in the hatch cabinet.

There is only one report where investigators evaluated the effect of a probiotic applied into the hatch cabinet environment as an alternative to formaldehyde fumigation to reduce microbial contamination in commercial scale hatch cabinets. In this study, Graham et al. (2018) demonstrated that spray application of Bacillus subtilis spores and lyophilized Pediococcus acidilactici could be applied during the hatching phase in lieu of formaldehyde fumigation to reduce gram-negative bacteria in the hatch cabinet environment and in the GIT of chicks at hatch. This indicates that probiotics specifically applied to target the microbial bloom during the hatching phase may also alter GIT colonization at hatch. To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted using a similar approach to Graham et al. (2018) in a laboratory setting using Bacillus spp. specifically selected for their antimicrobial activity against hatchery-relevant bacteria.

Since application and testing in a commercial setting is not always practical, preliminary work in a laboratory setting is often preferred or even required before implementation into a commercial hatchery. Artificial contamination with relevant microorganisms is required in the lab setting to simulate the microbial load present in commercial hatch cabinets to effectively assess efficacy of products applied to the hatch cabinet environment during the hatching phase in a laboratory. A multi-pathogen environmental challenge model has been previously used to replicate microbial contamination during the hatching phase by applying known concentrations of E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, S. aureus, S. chromogens, and Aspergillus fumigatus to the eggshell surface at DOE19 (Graham et al., 2022). These microorganisms were the predominant ones recovered from a homogenate generated from the internal contents of non-viable embryos and were selected because of their relevance to contamination in commercial hatcheries (Graham et al., 2022). For this model, the multi-species challenge material is applied to the surface of the eggshell to replicate the “exploder” egg phenomenon as described above (Karunarathna et al., 2020). Formaldehyde fumigation has been implemented in commercial hatch cabinets for over a century to mitigate the microbial load in the hatch cabinet (Pernot, 1908), but efficacious alternatives are needed. In previous work, our group isolated and selected top Bacillus spp. candidates that possessed antimicrobial activity against E. coli, E. faecalis, and/or S. aureus to evaluate in the present study (unpublished data). Thus, the overall purpose of the current study was to use the multi-pathogen environmental challenge model (Graham et al., 2022) to investigate spray application of B. amyloliquefaciens (MCR002 and/or MCR009) solid state fermentation (SSF) product into the hatch cabinet environment during the hatching phase on the microbial bloom, enteric colonization, and early performance in broiler chickens.

Materials and methods

Trial design

For trial 1, a total of 1,575 embryos (n = 225 embryos/hatcher x 1 hatcher/treatment) were placed in seven separately assigned hatch cabinets. A total of 2,700 embryos (n = 225 embryos/hatcher x 2 hatchers/treatment) and 1,950 embryos (n = 195 embryos/hatcher x 2 hatchers/treatment) were used for trials 2 and 3, respectively. Treatment groups included: 1) non-challenged control (NC), 2) challenged with pathogen mix (PM), 3) PM + formaldehyde treated (PM + F), 4) PM + Bacillus amyloliquefaciens MCR002 (PM + MCR002), 5) PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR009 (PM + MCR009), and 6) PM + MCR002 + MCR009 (PM + Combo). PM + Combo was only evaluated in trials 1 and 2 due to limited effectiveness observed.

For this study, GQF 1550 hatch cabinets (GQF Manufacturing, Savannah, GA, Cat. No. 1550) were used. Hatcher setup and operation, challenge inoculum preparation and application, sampling methods, timelines, and all other functional parameters were consistent across all trials. Hatch cabinets were set up to prevent any cross-contamination between cabinets during the hatching phase similar to Graham et al. (2022). More specifically, the NC and PM + F hatchers were located in a separate adjacent room in the facility. To evaluate early performance, chicks were weighed and allocated into floor pens based on treatment (n = 6 pens/treatment and 22 chicks/pen) for trial 1 and n = 10 pens/treatment (22 chicks/pen) for trial 2. Weight allocation within treatment groups at day of hatch (DOH) was performed to normalize pen weight and reduce pen effects on body weight (BW) by providing similar (±10 g) starting pen weights. Pen weights were recorded at DOH and d7 for trial 1 and at DOH, d7, and d14 for trial 2. Chicks had ad libitum access to water and a balanced, unmedicated corn and soybean meal diet meeting nutritional requirements for broilers recommended by Aviagen (Aviagen, 2018). Performance was not evaluated in trial 3.

Challenge preparation

The PM challenge was prepared using the methods described in Graham et al. (2022). Aspergillus fumigatus was omitted from the PM in the present study since the anti-fungal effect of the candidate Bacillus isolates was not evaluated. The PM challenge included two wild-type Escherichia coli isolates (field isolate LG 2016; hatchery isolate 021), Staphylococcus aureus (hatchery isolate 004B), and Enterococcus faecalis (hatchery isolate 031B). Each bacterium was individually cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB, VWR VWR, Suwanee, GA, Cat. No. 90000-378) at 37C for ∼18 h. E. coli and S. aureus isolates were grown aerobically with static or orbital shaking conditions, respectively, while E. faecalis was grown under static microaerophilic conditions (5 % CO2). After incubation, cultures were washed 1x, held overnight at 4C, and enumerated on respective media described below. To prepare the PM challenge at DOE19, the appropriate volume (based off CFU/mL) of each washed culture was concentrated by centrifugation and the pellets were resuspended in 2x TSB containing 0.01 % xanthan gum and combined as previously described (Graham et al., 2022). After mixing, the PM challenge was enumerated to confirm CFU/mL (or final CFU/100uL/embryo) by drop plating onto MacConkey agar for gram-negative bacteria (VWR, Suwanee, GA, Cat. No. 89405-630), CHROMagar™ Orientation agar for Enterococcus spp. (CO agar, DRG International, Springfield Township, NJ, Cat. No. RT412), and CHROMagar™ Staph aureus agar for S. aureus (CS agar, DRG International, Springfield Township, NJ, Cat. No. TA672).

On DOE19, embryos were briefly removed from the hatch cabinet and 100uL of PM was applied to the blunt end of the eggs surface for all groups excluding NC. The PM was then distributed over a 28 mm area using a sterile disposable loop (∼half the size of the air cell).

Candidate Bacillus isolates and application

Two B. amyloliquefaciens isolates (MCR002 and MCR009) were selected for the current study based off their antimicrobial activity against hatchery-associated opportunistic pathogens (unpublished data). A SSF process was used to generate a MCR002 and MCR009 spore-based product for the study. Briefly, SSF media was prepared by combining wheat bran, rice hulls, and trace minerals and autoclaved at 121C for 30 min. Each B. amyloliquefaciens isolate was grown aerobically in 100 mL TSB at 37C for 24 h. This starter culture was used to inoculate the SSF media followed by incubation for 3d at 37C. Following incubation, the SSF was desiccated for 5d in a drying oven at 60C. The dry SSF product was ground into a powder using a standard coffee grinder. SSF products were enumerated by spread plating 10-fold serial dilutions made with sterile 0.9 % saline onto tryptic soy agar (TSA, VWR, Suwanee, GA, Cat. No. 90000–378). Plates were incubated aerobically at 37C for 18 h. The concentration of MCR002 and MCR009 SSF products was confirmed to be 1 × 1010 CFU/g. SSF products were stored in a sealed sterile container at room temperature and used for all trials within a 12-month period. Before each trial, CFU/g was confirmed for MCR002 and MCR009 SSF products using the methods described above.

One gram of each SSF product for PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 or 0.5 g of each for the PM + Combo treatment was applied via compressed air (40 PSI) through modified ports located 10 inches in front of the ventilation fan inside the hatch cabinet. SSF products (1 × 1010 CFU/g) were applied four times (four total applications) to respective PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo hatchers at 30 min post-challenge with PM on DOE19, at ∼50 % and 80 % pip on DOE20, and at ∼100 % pip on DOE21 (∼8 h prior to hatch pull). Application time points were selected based off previous work (Graham et al., 2018).

Formaldehyde application

Formaldehyde was applied via peristaltic pump at 4 h intervals beginning 1 h post challenge on DOE19 and ending 12 h prior to hatch pull on DOE21. The volume, timing, and method of application designed to simulate commercial conditions were previously reported in Graham et al. (2022) and Selby et al. (2023).

Environmental sampling

Environmental air samples were obtained from the hatch cabinet environment 4x during the hatching phase (DOE20-DOE21). Sampling was conducted using the open-agar plate method (Berrang et al., 1995; Kim and Kim, 2010; Graham et al., 2018) 3x on DOE20 (20 %, 50 %, 80 % pip) and 1x at DOE21 immediately prior to hatch pull (n = 3 plates/timepoint/hatcher/media). At the time of sampling, the lid of the agar plate was removed, and the exposed agar was placed into the hatch cabinet environment using the sampling port described above. Gram-negative bacteria, Enterococcus spp., S. aureus, and Bacillus spp. recovery was evaluated using MacConkey agar, CO agar, CS agar, and TSA, respectively. A 5 m sampling duration was selected for MacConkey agar and a 1 m sampling duration for used for CO agar, CS agar, and TSA based off our previous work (Graham et al., 2022; Selby et al., 2023). TSA, CS agar, and MacConkey agar plates were incubated aerobically at 37C for 18 h while CO agar plates were incubated at 37C for 48 h.

Fluff sampling

Promptly after hatch pull, ∼1 g of fluff was collected from each hatch cabinet (n = 1 composite sample/hatcher that was enumerated in triplicate). Gloves were changed between each cabinet to avoid cross contamination, and eggshell fragments were avoided to reduce error in bacterial recovery. Fluff samples were weighed, diluted with sterile 0.9 % saline at a 1:50 w/v dilution, and homogenized prior to drop plating onto CO agar, CS agar, TSA, and MacConkey agar and incubated as described above. Bacteria colonies were counted and expressed as Log10 CFU/g of sample.

GIT Sampling

On DOE21 (DOH), GIT samples (duodenum to the cecum, n = 12 chicks/treatment) were aseptically collected into sterile bags. The yolk sac was removed prior to placing the GIT into the sample bag. GIT samples were weighed and homogenized, and 1:4 wt/vol dilutions were made using sterile 0.9 % saline. Ten-fold dilutions of each sample, from each group, were made in a sterile 96-well microtiter plates and the diluted samples were drop plated to evaluate presumptive gram-negative bacteria, Staphylococcus spp., and Enterococcus spp. on the media described above. A subset of the homogenized GIT sample was pasteurized for 10 m at 70C to eliminate any remaining vegetative cells and plated on TSA to assess Bacillus spp. recovery. All plates were incubated at 37C for 18-24 h and data was expressed as Log10 CFU/g of sample.

Animal Source

For all trials, candled and unvaccinated Ross 308 embryonated eggs were obtained from a local commercial hatchery at DOE18. Embryos were randomly allocated and placed into separate hatchers based on treatment group. All trials and animal handling procedures complied with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arkansas, protocol #23028.

Statistical analysis

Environmental (air samples) data has been expressed as CFU/plate while DOH GIT and fluff sample data has been expressed as Log10 CFU/g sample. CFU was reported for the environmental air samples only since the microbial load in the hatch cabinets was order of magnitudes lower than GIT or fluff (reported as Log10 CFU/g). A meta-analysis was conducted for trials 1-3 microbial recovery. PM + Combo was not evaluated in trial 3 and therefore removed from the meta-analysis. Additionally, performance data was not included in the meta-analysis since data was obtained from two trials, both of which terminated on different days. For performance data in trials 1 and 2, the pen was the experimental unit. For all microbial recovery data and performance data, ANOVA (JMP Pro 17) was used to determine significant differences with means further separated using Student’s t-test. This approach was used for all CFU and Log10 CFU/g data by trial and the meta-analysis where appropriate. Chi-square test was used to evaluate significant differences in mortality and hatchability. Significance reported as P < 0.05 unless otherwise noted. Additionally, a brief overview of the experimental design from DOE18-DOE21/DOH has been provided (Fig. 5).

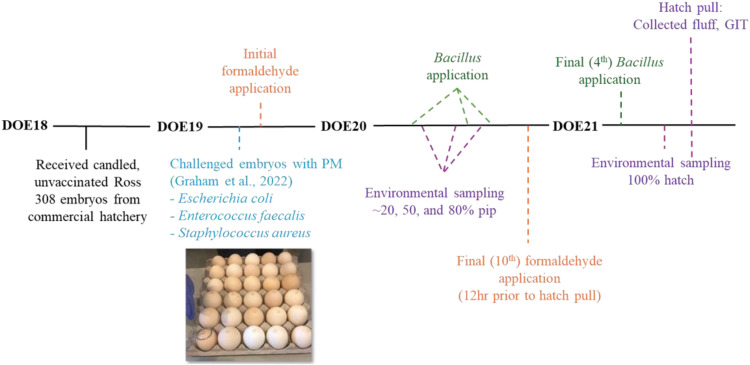

Fig. 5.

Graphical overview of the experimental design from DOE18-DOE21/DOH.

Results

Environmental sampling

Bacterial recovery from the environmental samples collected from the hatch cabinets during the hatching phase for all three trials have been presented in Table 1. NC had significantly (P < 0.05) reduced gram-negative bacteria, Enterococcus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus recovery compared to PM across all trials. Bacillus spp. recovery was significantly higher for the PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 across all trials compared to the NC, PM, and PM + F groups.

Table 1.

Average bacterial recovery (CFU) from the hatch cabinet environment during the hatching phase.

| Trial | Treatment1 | Gram-negative bacteria | Bacillus spp. | Enterococcus spp. | Staphylococcus aureus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | NC | 1.00 | ± | 0.66b | 10.17 | ± | 1.79c | 0.83 | ± | 0.59b | 0.08 | ± | 0.08c |

| PM | 37.58 | ± | 8.30a | 169.42 | ± | 49.60b | 69.67 | ± | 24.80a | 34.75 | ± | 8.27a | |

| PM + F | 3.83 | ± | 1.84b | 55.00 | ± | 15.70c | 14.58 | ± | 3.14b | 0.50 | ± | 0.50c | |

| PM + MCR002 | 8.09 | ± | 2.34b | 258.67 | ± | 24.10a | 1.50 | ± | 0.40b | 4.58 | ± | 1.28c | |

| PM + MCR009 | 0.17 | ± | 0.11b | 341.33 | ± | 30.70a | 1.08 | ± | 0.61b | 19.50 | ± | 6.25b | |

| PM + Combo | 7.00 | ± | 4.29b | 282.17 | ± | 28.80a | 8.67 | ± | 2.12b | 33.00 | ± | 6.97ab | |

| Trial 2 | NC | 0.04 | ± | 0.04c | 14.63 | ± | 2.12b | 0.72 | ± | 0.15d | 0.38 | ± | 0.13c |

| PM | 38.00 | ± | 9.20ab | 14.08 | ± | 1.97b | 61.30 | ± | 12.80b | 102.58 | ± | 18.90b | |

| PM + F | 20.54 | ± | 11.70bc | 8.96 | ± | 1.02b | 1.68 | ± | 0.34d | 4.08 | ± | 1.49c | |

| PM + MCR002 | 9.75 | ± | 1.40c | 292.17 | ± | 24.90a | 27.61 | ± | 4.31c | 115.63 | ± | 23.30b | |

| PM + MCR009 | 52.71 | ± | 7.70ab | 290.17 | ± | 30.40a | 117.43 | ± | 18.20a | 199.25 | ± | 24.70a | |

| PM + Combo | 37.21 | ± | 6.57ab | 253.17 | ± | 22.20a | 48.13 | ± | 9.13bc | 100.50 | ± | 8.54b | |

| Trial 3 | NC | 0.21 | ± | 0.12c | 21.13 | ± | 3.45b | 20.79 | ± | 8.64bc | 0.04 | ± | 0.04b |

| PM | 46.58 | ± | 10.10a | 22.00 | ± | 9.45b | 51.25 | ± | 10.80a | 3.83 | ± | 0.97b | |

| PM + F | 17.42 | ± | 6.10b | 13.33 | ± | 2.10b | 15.04 | ± | 4.33c | 0.38 | ± | 0.12b | |

| PM + MCR002 | 2.46 | ± | 1.29bc | 209.63 | ± | 13.40a | 21.42 | ± | 5.39bc | 40.79 | ± | 17.70a | |

| PM + MCR009 | 52.38 | ± | 6.24a | 235.25 | ± | 19.40a | 38.75 | ± | 5.14ab | 3.50 | ± | 0.76b | |

Data expressed as mean CFU ± SE across all timepoints (20, 50, 80 % pip, and 100 % hatch).

a, b, c, d Differing superscripts indicate significant differences between treatments by trial and type of bacteria. Trial 1 n = 12 plates/treatment/bacteria; trials 2 and 3 n = 24 plates/treatment/bacteria.

Treatment abbreviations: Negative Control (NC); Pathogen Mix (PM); PM + Formaldehyde (PM + F); PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR002 (PM + MCR002); PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR009 (PM + MCR009); PM + MCR002 + MCR009 (PM + Combo).

For gram-negative bacterial recovery in trial 1, the PM hatchers had significantly more gram-negative bacteria circulating in the hatch cabinet environment during the hatching phase compared to NC, PM + F, PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo. These results were not replicated in trial 2 or 3 for PM + MCR009 since gram-negative bacterial recovery was statistically increased compared to PM. Additionally, in trial 2 PM + Combo had similar gram-negative bacterial recovery to PM. Gram-negative bacterial recovery was significantly lower in PM + MCR002 hatch cabinets in trial 2 and trial 3 compared to PM.

Enterococcus spp. recovery from PM was significantly higher than NC, PM + F, PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo. In trial 2, only NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 had a significant reduction in Enterococcus spp. recovery compared to PM while a significant increase was observed in PM + MCR009. In trial 2, NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 had significantly less Enterococcus spp. compared to PM. Although PM + MCR009 was numerically lower than PM in trial 3, no statistical differences were observed between the groups.

In trial 1, a significant reduction in S. aureus recovery from the hatch cabinet environment was observed for NC, PM + F, PM + MCR002, and PM + MCR009 compared to PM. In trial 2, NC and PM + F were the only groups with significantly lower S. aureus recovery compared to PM. In trial 3, NC, PM, PM + F, and PM + MCR009 had similar S. aureus recovery from the hatch cabinet environment while PM + MCR002 had significantly higher recovery than all other groups.

Day of hatch fluff sampling

Bacterial recovery from DOH fluff samples for all three trials has been presented as average Log10 CFU/g sample in Table 3. In trials 1 and 2, gram-negative bacterial recovery was significantly reduced in fluff samples collected from PM + F hatchers compared to PM. In trial 3, gram-negative recovery from PM + F fluff samples was numerically lower than PM. PM + MCR002 fluff samples had significantly less gram-negative bacterial recovered compared to PM in trials 2 and 3 with only a numerical reduction observed between PM + MCR002 and PM in trial 1. There were markedly less gram-negative bacteria recovered PM + MCR009 fluff samples compared to PM in only trial 1. Bacillus spp. recovered from fluff samples was significantly increased in all trials for PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 and for PM + Combo (trials 1 and 2 only) compared to the NC, PM, and PM + F.

Table 3.

Average bacterial recovery (Log10 CFU/g) from fluff samples collected at DOH.

| Trial | Treatment1 | Gram-negative bacteria | Bacillus spp. | Enterococcus spp. | Staphylococcus aureus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | NC | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 3.96 | ± | 0.14c | 2.47 | ± | 1.23b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c |

| PM | 5.75 | ± | 0.12a | 6.52 | ± | 0.11b | 4.93 | ± | 0.14a | 5.04 | ± | 0.07b | |

| PM + F | 2.47 | ± | 1.23b | 3.80 | ± | 0.10c | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | |

| PM + MCR002 | 5.63 | ± | 0.19a | 8.33 | ± | 0.20a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 1.23 | ± | 1.23c | |

| PM + MCR009 | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 8.37 | ± | 0.33a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 4.11 | ± | 0.06b | |

| PM + Combo | 6.10 | ± | 0.10a | 8.90 | ± | 0.10a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 6.85 | ± | 0.15a | |

| Trial 2 | NC | 0.00 | ± | 0.00d | 4.34 | ± | 0.08b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 0.00 | ± | 0.00d |

| PM | 6.34 | ± | 0.11b | 4.46 | ± | 0.16b | 6.34 | ± | 0.12b | 6.45 | ± | 0.20c | |

| PM + F | 0.00 | ± | 0.00d | 1.85 | ± | 0.83c | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 0.78 | ± | 0.78d | |

| PM + MCR002 | 5.51 | ± | 0.07c | 9.31 | ± | 0.19a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 6.95 | ± | 0.11bc | |

| PM + MCR009 | 6.48 | ± | 0.38b | 8.65 | ± | 0.17a | 6.36 | ± | 0.21b | 7.60 | ± | 0.18ab | |

| PM + Combo | 8.00 | ± | 0.31a | 9.68 | ± | 0.24a | 7.65 | ± | 0.09a | 8.20 | ± | 0.25a | |

| Trial 3 | NC | 1.95 | ± | 0.88c | 5.83 | ± | 0.15c | 3.02 | ± | 1.35b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c |

| PM | 6.47 | ± | 0.08a | 6.91 | ± | 0.13b | 6.21 | ± | 0.07a | 4.39 | ± | 0.14a | |

| PM + F | 5.33 | ± | 0.40ab | 5.90 | ± | 0.15c | 2.68 | ± | 1.20b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | |

| PM + MCR002 | 4.40 | ± | 0.26b | 8.28 | ± | 0.08a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 4.02 | ± | 1.07ab | |

| PM + MCR009 | 6.12 | ± | 0.08a | 8.29 | ± | 0.12a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 2.68 | ± | 0.85b | |

Data expressed as mean Log10 CFU/g ± SE.

a, b, c, d Differing superscripts indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between treatments by trial and type of bacteria. Trials 1-3 n = 12 treatment/bacteria. Trial 1 n = 3 plates/treatment/bacteria. Trials 2 and 3 n = 6 plates/treatment/bacteria.

Treatment abbreviations: Negative Control (NC); Pathogen Mix (PM); PM + Formaldehyde (PM + F); PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR002 (PM + MCR002); PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR009 (PM + MCR009); PM + MCR002 + MCR009 (PM + Combo).

Enterococcus spp. recovery from fluff samples was significantly lower in PM + F, PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo (trial 1 only) compared to PM in trials 1 and 3. In trial 2, PM + F and PM + MCR002 fluff samples had significantly less Enterococcus spp. compared to PM. However, Enterococcus spp. recovery from PM + MCR009 and PM fluff samples were not different whereas recovery from PM + Combo was significantly increased compared to PM. In all trials, PM + F and NC fluff samples had a significantly lower S. aureus recovery compared to PM. In trial 1 only, PM + MCR002 fluff samples also had markedly less S. aureus compared to PM. In trial 3, a significant decrease in S. aureus recovery from fluff samples was observed between PM + MCR009 and PM.

Day of hatch gastrointestinal sampling

DOH GIT results have been shown in Table 2 where data are presented as average Log10 CFU/g sample. In trials 1 and 2, gram-negative bacterial recovery from the GIT was significantly higher for PM compared to NC, PM + F, PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo. However, in trial 3, gram-negative bacterial recovery was statistically similar between PM and PM + MCR009 but was significantly higher in NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 compared to PM. In all trials, Bacillus spp. recovery was significantly increased in PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo (trials 1 and 2 only). In trial 1, PM + MCR002 had significantly lower Bacillus spp. recovery than PM + MCR009 and PM + Combo but significantly higher recovery than NC, PM, and PM + F.

Table 2.

Average bacterial recovery (Log10 CFU/g) from GIT samples collected at DOH.

| Trial | Treatment1 | Gram-negative bacteria | Bacillus spp. | Enterococcus spp. | Staphylococcus aureus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | NC | 0.00 | ± | 0.00d | 0.22 | ± | 0.22c | 0.29 | ± | 0.29b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a |

| PM | 5.86 | ± | 0.47a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 2.63 | ± | 1.03a | 0.46 | ± | 0.46a | |

| PM + F | 1.75 | ± | 0.69bc | 0.67 | ± | 0.35c | 3.26 | ± | 0.87a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a | |

| PM + MCR002 | 2.13 | ± | 0.75b | 2.72 | ± | 0.39b | 1.48 | ± | 0.80ab | 0.47 | ± | 0.47a | |

| PM + MCR009 | 0.44 | ± | 0.44cd | 3.81 | ± | 0.25a | 3.25 | ± | 0.80a | 0.28 | ± | 0.28a | |

| PM + Combo | 3.02 | ± | 0.77b | 3.94 | ± | 0.15a | 2.47 | ± | 0.78ab | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a | |

| Trial 2 | NC | 0.00 | ± | 0.00d | 0.00 | ± | 0.00b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a |

| PM | 7.74 | ± | 0.51a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00b | 2.32 | ± | 0.98ab | 0.37 | ± | 0.37a | |

| PM + F | 1.49 | ± | 0.76cd | 0.31 | ± | 0.31b | 0.22 | ± | 0.22b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a | |

| PM + MCR002 | 3.80 | ± | 1.21bc | 3.53 | ± | 0.50a | 1.78 | ± | 0.93ab | 0.33 | ± | 0.33a | |

| PM + MCR009 | 0.64 | ± | 0.64d | 4.01 | ± | 0.15a | 4.06 | ± | 1.23a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a | |

| PM + Combo | 4.29 | ± | 1.19b | 3.76 | ± | 0.18a | 4.11 | ± | 1.19a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00a | |

| Trial 3 | NC | 0.74 | ± | 0.51c | 0.00 | ± | 0.00c | 0.96 | ± | 0.66b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00b |

| PM | 6.04 | ± | 0.73a | 0.98 | ± | 0.42b | 5.39 | ± | 0.65a | 0.35 | ± | 0.35b | |

| PM + F | 3.34 | ± | 0.97b | 0.22 | ± | 0.22c | 2.27 | ± | 0.99b | 0.00 | ± | 0.00b | |

| PM + MCR002 | 2.96 | ± | 0.84b | 4.23 | ± | 0.17a | 4.74 | ± | 0.93a | 1.44 | ± | 0.52a | |

| PM + MCR009 | 7.56 | ± | 0.28a | 4.18 | ± | 0.10a | 6.48 | ± | 0.66a | 0.00 | ± | 0.00b | |

Data expressed as mean Log10 CFU/g ± SE.

abcd Differing superscripts indicate significant differences between treatments by trial and type of bacteria. Trials 1-3 n = 12 treatment/bacteria.

Treatment abbreviations: Negative Control (NC); Pathogen Mix (PM); PM + Formaldehyde (PM + F); PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR002 (PM + MCR002); PM + B. amyloliquefaciens MCR009 (PM + MCR009); PM + MCR002 + MCR009 (PM + Combo).

In trial 1, Enterococcus spp. recovery from the GIT was significantly lower in NC at DOH compared to PM. However, there were no differences between challenged groups for Enterococcus spp. recovery in trial 1. In trial 2, the only differences observed for Enterococcus spp. recovery from the GIT were between NC, PM + MCR002, and PM + MCR009. However, in trial 3, NC and PM + F were the only groups with significantly lower Enterococcus spp. recovery from the GIT at DOH compared to PM. There were no differences between PM, PM + MCR002, and PM + MCR009 for Enterococcus spp. recovery in trial 3. The only significant differences observed for the recovery of S. aureus were in trial 3 where PM + MCR002 was significantly higher compared to NC, PM, PM + F, and PM + MCR009.

Meta-analysis of bacterial recovery

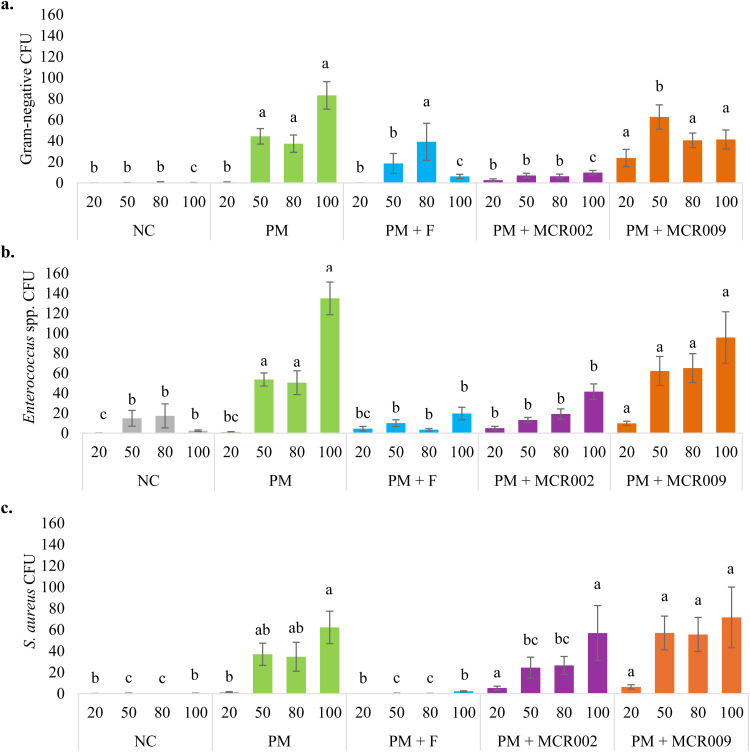

A meta-analysis across for gram-negative bacteria, Enterococcus spp., and S. aureus recovery from the hatch cabinet environment has been presented in Fig. 1. PM + Combo was only evaluated in trials 1 and 2 and was excluded from the meta-analysis. PM + MCR009 had significantly (P < 0.05) elevated gram-negative bacterial recovery from the hatch cabinet environment at the 20 % pip timepoint compared to all other groups (Fig. 1A). At the 50 % pip timepoint, PM + MCR009 and PM were similar and significantly higher for gram-negative bacterial recovery compared to all other groups. PM, PM + F, and PM + MCR009 were similar at the 80 % pip timepoint and had significantly higher gram-negative bacterial recovery compared to NC and PM + MCR002. At the 100 % hatch timepoint, PM had significantly higher gram-negative bacterial recovery from the hatch cabinet environment compared to all other groups while PM + MCR009 was significantly higher than NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002.

Fig. 1.

Meta-analysis across trials by treatment and timepoint for a) gram-negative bacteria, b) Enterococcus spp., and c) S. aureus recovery from the hatch cabinet environment. Samples were collected on DOE20 (∼20 %, ∼50 %, or ∼80 % pip) or immediately prior to hatch pull on DOH (100 %) (n = 15 plates/timepoint/treatment). Data expressed as average CFU/plate ± SE. a, b, c Differing superscripts indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between treatments by timepoint.

Recovery of Enterococcus spp. from the hatch cabinet environment was significantly increased at the 20 % pip timepoint for PM + MCR009 compared to all other groups (Fig. 1B). There were no significant differences observed for Enterococcus spp. recovery at the 50 % pip timepoint between PM + MCR002, PM + F, or PM. However, recovery for NC was significantly lower than PM + MCR002. NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 had similar Enterococcus spp. recovery from the hatch cabinet environment at the 80 % pip and 100 % hatch timepoints but were significantly lower recovery compared to PM and PM + MCR009. PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 had significantly higher S. aureus recovery compared to NC, PM, and PM + F at the 20 % pip timepoint (Fig. 1C). NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 were not significantly different at the 50 % and 80 % pip timepoints for S. aureus recovery however, PM + MCR002 was not significantly different from PM while NC and PM + F were. PM + MCR009 was also not significantly different compared to PM at the 50 % and 80 % pip timepoints for S. aureus recovery from the hatch cabinet environment. At the 100 % hatch timepoint, PM, PM + MCR002, and PM + MCR009 were similar for S. aureus recovery which was significantly increased compared to NC and PM + F.

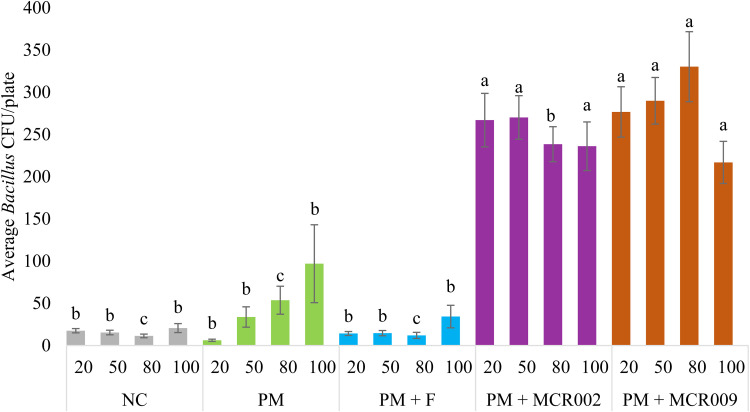

Recovery of Bacillus spp. from the hatch cabinet environment across all trials by group and timepoint has been presented in Fig. 2. PM + Combo was not included in this meta-analysis. NC, PM, and PM + F were similar at all timepoints for Bacillus spp. while PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 had significantly elevated recovery at all timepoints. PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 had similar Bacillus spp. recovery at 20 % pip, 50 % pip, and 100 % hatch timepoints whereas PM + MCR009 had significantly higher recovery at the 80 % pip timepoint compared to PM + MCR002.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis across trials by treatment and timepoint for Bacillus spp. recovery from the hatch cabinet environment. Samples were collected on DOE20 (∼20 %, ∼50 %, or ∼80 % pip) or immediately prior to hatch pull on DOH (100 %) (n = 15 plates/timepoint/treatment). Data expressed as average CFU/plate ± SE. a, b, c Differing superscripts indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between treatments by timepoint.

To evaluate combined opportunistic pathogen recovery (gram-negative bacteria, Enterococcus spp., and S. aureus) across trials by group and timepoint, an additional meta-analysis was performed and has been presented in Fig. 3 similar to Graham et al. (2022). Combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment for PM + MCR009 was significantly higher than all other groups at the 20 % pip timepoint. PM, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 had similar combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment at the 20 % pip timepoint while PM and PM + F were also similar to NC. Combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment was similar between NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002 at the 50 % and 80 % pip timepoints and was significantly reduced compared to PM and PM + MCR009. While PM + MCR009 had significantly higher combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment compared to all other groups at the 50 % pip timepoint, it was similar to PM at the 80 % pip timepoint. PM had significantly higher combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment at the 100 % hatch timepoint compared to all other groups. Additionally, NC and PM + F were similar and had significantly reduced combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment at the 100 % hatch timepoint compared to all other groups. Although PM + MCR009 had a significant reduction in combined opportunistic pathogen recovery from the hatch cabinet environment at the 100 % timepoint compared to PM, combined opportunistic pathogen recovery was significantly elevated compared to NC, PM + F, and PM + MCR002.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis for the combined gram-negative bacteria, Enterococcus spp., and S. aureus recovery by treatment and timepoint. Samples were collected on DOE20 (∼20 %, ∼50 %, or ∼80 % pip) or immediately prior to hatch pull on DOH (100 %) (n = 45 plates/timepoint/ treatment). Data expressed as average CFU/plate ± SE. a, b, c, d Differing superscripts indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between treatments by timepoint.

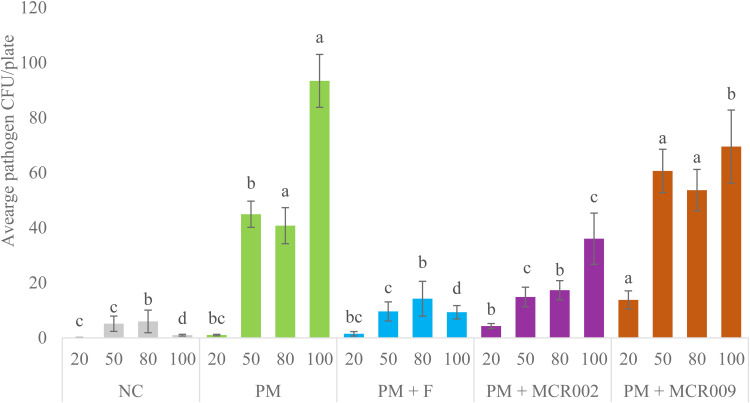

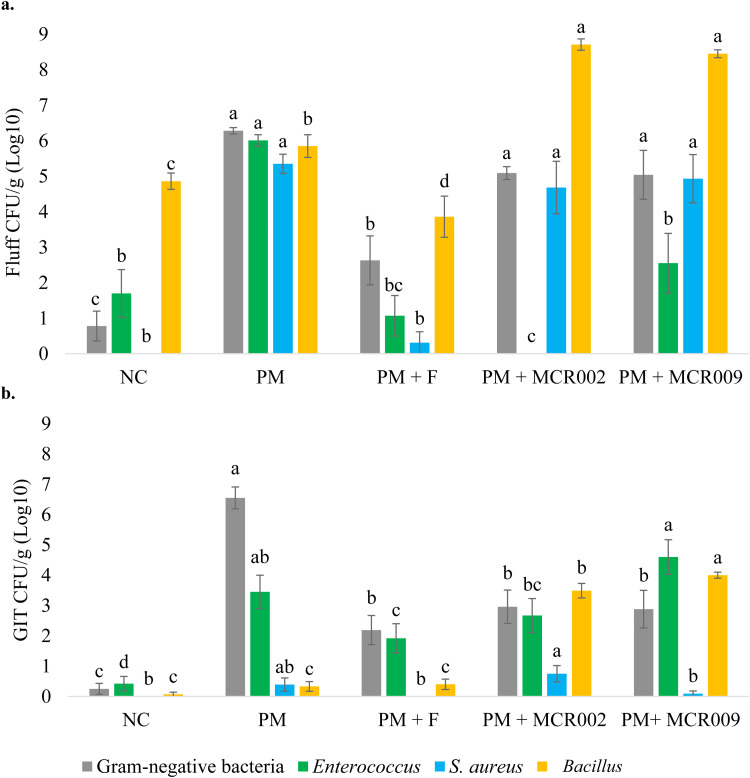

A meta-analysis of bacterial recovery from DOH fluff samples across trials by group, excluding PM + Combo has been presented in Fig. 4A. NC and PM + F were the only groups with a significant reduction in gram-negative bacteria recovery compared to PM. For Enterococcus spp. recovery, NC, PM + F, PM + MCR002, and PM + MCR009 had a significant reduction compared to PM in the DOH fluff samples. There was a significant reduction in NC and PM + F for S. aureus recovery but no differences were observed between PM, PM + MCR002, and PM + MCR009. Recovery of Bacillus spp. was significantly higher in both PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009 compared to all other groups.

Fig. 4.

Meta analysis of a) bacterial recovery (Log10 CFU/g) from fluff samples collected at DOH (n = 15 samples/treatment) and b) bacterial recovery (Log10 CFU/g) from DOH GIT samples (n = 36 samples/treatment). Data expressed mean ± SE. a, b, c, d Differing superscripts indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between treatments by type of bacteria.

A meta-analysis of bacterial recovery across trials by treatment for GIT samples collected at DOH has been presented in Fig. 4B. Gram-negative bacterial recovery was significantly reduced in all groups compared to PM. Enterococcus spp. recovery was significantly increased in PM compared to NC. Although Enterococcus spp. recovery from DOH GIT samples was not significantly different between PM + F and PM + MCR002, PM + MCR002 was also not significantly different from PM. Enterococcus spp. recovery from DOH GIT samples was the highest in PM + MCR009 while this group was not significantly different from PM. S. aureus recovery from PM was not significantly different compared to all other groups. Bacillus spp. recovery was significantly different between PM + MCR002 and PM + MCR009. However, both Bacillus-treated groups had a marked increase in Bacillus spp. recovery from the GIT at hatch compared to all other treatment groups.

Performance

There were no significant differences in hatchability or mortality observed in trial 1 or 2 (Table 4). No differences in BW or BWG were observed at d7 or d14 in either trial (Table 5). While significant differences were observed in average DOH BW, the range for both trials were 1 g or less between groups.

Table 4.

Hatchability and mortality (%).

| Trial | Treatment | Hatchability (%) | d0-7 Mortality (%) | d0-14 Mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | NC | 221/225 (98.22) | 1/132 (0.75) | - |

| PM | 223/225 (99.11) | 0/132 (0) | - | |

| PM + F | 224/225 (99.56) | 0/132 (0) | - | |

| PM + MCR002 | 222/225 (98.67) | 0/132 (0) | - | |

| PM + MCR009 | 221/225 (98.22) | 0/132 (0) | - | |

| PM + Combo | 224/225 (99.56) | 1/132 (0.75) | - | |

| Trial 2 | NC | 443/450 (98.44) | 2/198 (1.01) | 4/198 (2.02) |

| PM | 432/450 (96.00) | 0/198 (0) | 0/198 (0) | |

| PM + F | 436/450 (96.89) | 0/220 (0) | 0/220 (0) | |

| PM + MCR002 | 432/450 (96.00) | 1/198 (0.50) | 1/198 (0.5) | |

| PM + MCR009 | 439/450 (97.56) | 1/198 (0.50) | 2/198 (1.01) | |

| PM + Combo | 445/450 (98.89) | 1/220 (0.45) | 1/220 (0.45) | |

| Trial 3 | NC | 390/390 (100) | - | - |

| PM | 386/390 (98.97) | - | - | |

| PM + F | 389/390 (99.74) | - | - | |

| PM + MCR002 | 387/390 (99.23) | - | - | |

| PM + MCR009 | 390/390 (100) | - | - |

Hatchability expressed as hatched/total embryos placed (%). Trial 1 n = 1 hatcher/treatment. Trial 2 and 3 n = 2 hatchers/treatment.

Mortality expressed as total mortalities/total chick placed (%). Trials 1 n = 6 pens/treatment. Trial 2 n = 10 pens/treatment.

No significant differences were observed using chi-square test.

Table 5.

Average BW and BWG (Trial 1 and 2).

| Average BW (g) |

Average BWG (g) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Treatment | DOH | d7 | d14 | d0-7 | d0-14 |

| Trial 1 | NC | 39.9 ± 0.22ab | 140.2 ± 3.66 | - | 97.9 ± 3.62 | - |

| PM | 39.5 ± 0.24b | 137.0 ± 1.67 | - | 95.3 ± 1.52 | - | |

| PM + F | 40.3 ± 0.20ab | 144.9 ± 3.13 | - | 101.9 ± 3.00 | - | |

| PM + MCR002 | 39.9 ± 0.32ab | 137.8 ± 4.49 | - | 95.9 ± 4.57 | - | |

| PM + MCR009 | 39.5 ± 0.28b | 141.2 ± 2.53 | - | 100.1 ± 2.79 | - | |

| PM + Combo | 40.5 ± 0.34ab | 145.0 ± 2.12 | - | 102.1 ± 1.77 | - | |

| Trial 2 | NC | 41.6 ± 0.05c | 139.0 ± 6.22 | 348.6 ± 4.52 | 89.8 ± 6.98 | 304.7 ± 4.19 |

| PM | 41.9 ± 0.09ab | 130.6 ± 2.03 | 349.0 ± 8.91 | 86.9 ± 2.67 | 305.0 ± 8.52 | |

| PM + F | 42.1 ± 0.09ab | 129.4 ± 2.75 | 350.5 ± 9.56 | 87.0 ± 2.83 | 307.0 ± 9.71 | |

| PM + MCR002 | 41.8 ± 0.11bc | 130.9 ± 4.44 | 351.9 ± 15.00 | 88.7 ± 4.22 | 309.0 ± 14.95 | |

| PM + MCR009 | 41.7 ± 0.09bc | 131.0 ± 1.77 | 348.7 ± 11.82 | 90.3 ± 1.89 | 304.9 ± 11.90 | |

| PM + Combo | 41.6 ± 0.06c | 135.1 ± 2.32 | 342.3 ± 12.06 | 93.3 ± 2.30 | 299.2 ± 12.28 | |

Data expressed as mean ± SE. abc Differing superscripts indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between treatments by column. Trials 1 n = 6 pens/treatment. Trial 2 n = 10 pens/treatment.

Discussion

During the hatching phase, the microbial load in the hatch cabinet environment increases substantially (Magwood, 1967 Sheldon and Brake, 1991). This microbial bloom in the hatch cabinet consists of a consortium of beneficial, opportunistically pathogenic, and pathogenic microorganisms which has been traditionally controlled with formaldehyde fumigation (Pernot, 1908; Depner et al., 2021). However, formaldehyde is a toxic chemical and has been shown to cause damage to respiratory tissues in neonate chickens (Sander et al., 1995; NIEHS, 2011; Maharjan et al., 2017) and non-selectively targets beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms. Thus, alternatives are needed for application in the commercial hatchery space. Application of probiotics during late embryogenesis could be used as a unique and chemical-free method to control the microbial bloom in the hatch cabinet. Graham et al. (2018) revealed that chicks hatched in commercial hatch cabinets treated with a Bacillus and lactic acid bacteria-based probiotic had significantly lower gram-negative bacterial recovery from the GIT 24 h post-hatch than chicks hatched in formaldehyde fumigated hatch cabinets. This shift in enteric colonization in the probiotic group was likely due to the altered microbial bloom in the hatch cabinet environment (Graham et al., 2018). While this study serves as proof of concept, more research is needed to understand the benefits and limitations of probiotics applied into the environment during the hatching phase.

To better assess the feasibility of probiotic application into the hatch cabinet environment on environmental and chick parameters, evaluation in a controlled setting is required. The study performed by Graham et al. (2018) was conducted in a commercial setting whereas the present study was performed in research scale hatch cabinets utilizing a multi-species environmental challenge model previously described by Graham et al. (2022) and Selby et al. (2023). This model was developed to mimic environmental contamination in a commercial hatch cabinet using hatchery derived opportunistic pathogens in a laboratory setting. In the current study, two B. amyloliquefaciens isolates, MCR002 and MCR009, that possess antimicrobial activity against hatchery-associated opportunistic bacterial pathogens (unpublished work) were used. Application of MCR002 resulted in a marked reduction in gram-negative bacteria in the hatch cabinet environment compared to the untreated PM control in all trials. More importantly, MCR002 application reduced gram-negative bacteria and Enterococcus spp. in the hatch cabinet environment similar to formaldehyde. This was somewhat unexpected for gram-negative bacteria at least since Graham et al. (2018) demonstrated that efficacy of the spray applied probiotic declined towards the end of the hatching phase. The improved efficacy of MCR002 throughout the hatching phase could be related to its specificity against the bacterial isolates included in the PM challenge. This suggests that spray application of B. amyloliquefaciens MCR002 may effectively mitigate gram-negative bacteria and Enterococcus in commercial hatch cabinets. MCR002 application reduced Enterococcus and gram-negative bacteria and in the hatch cabinet environment and gram-negative bacteria GIT of chicks at hatch. MCR009 and the Combo were overall less effective than MCR002 alone at inhibiting microbial proliferation in the hatch cabinet environment. This highlights the importance of evaluating the efficacy of probiotic strains individually and in combination. For instance, cross-streaking MCR002 and MCR009 on TSA failed to reveal any inhibitory properties between the isolates but could have occurred when appeared in combination in the hatch cabinet environment. Moreover, S. aureus recovery from open agar plates and fluff samples appeared to be elevated in PM + MCR002, PM + MCR009, and PM + Combo compared to NC and PM + F. However, MCR002 and MCR009 morphology was characteristic of S. aureus on CS agar. In future work, the CS agar will be supplemented with antibiotics to more clearly elucidate the differences observed in these studies.

As previously mentioned, the primary goal of the study was to determine if MCR002 and/or MCR009 could preferentially colonize the hatch cabinet environment and the GIT at hatch using a challenge model designed to simulate environmental contamination in small-scale hatch cabinets. However, performance was assessed in 2 of 3 trials to determine if spray application of B. amyloliquefaciens spores into the hatch cabinet environment during late embryogenesis improved chick performance. B. amyloliquefaciens strains and methods used to apply the probiotics during the hatching phase did not affect hatchability or 7- or 14-d performance, including mortality, in broiler chickens. This could be due to the low virulence of the strains included in the PM challenge. The isolates in the PM challenge were not selected for their ability to negatively impact performance but were selected due to their relevance in hatch cabinet environments (Graham et al., 2022; Selby et al., 2023).

Probiotics, such as those described by Graham et al. (2018) or MCR002 in the present study, could be administered into the hatch cabinet environment to reduce microbial contamination and shift enteric colonization at hatch. Without sustained exposure post-hatch, Bacillus spp. will temporarily colonize the GIT of chicks (Kubasova et al., 2019). Initial exposure to beneficial Bacillus spp. during the hatching phase may accelerate the depletion of oxygen and promote colonization by beneficial microaerophilic and anaerobic microorganisms (Zhu et al., 2023). A multifaceted approach will be needed to fully eliminate the use of formaldehyde in commercial hatch cabinets. As a result, application of both a spore-forming, transient colonizer, such as MCR002, and a beneficial, persistent GIT colonizer(s) may be advantageous to evaluate in future studies.

Conclusion

Shifting the composition of the microbial bloom in the hatch cabinet environment during late embryogenesis altered enteric colonization at hatch, as indicated by significant differences in GIT recovery of chicks that hatched in the formaldehyde-treated and B. amyloliquefaciens MCR002-treated cabinets when compared to the PM control group. MCR002 outperformed MCR009 in terms of reducing the microbial load in the hatch cabinet and in the GIT of chicks at hatch. These results suggest that spray application of MCR002 into the hatch cabinet environment during the hatching phase could be explored as a method to reduce bacterial contamination in a commercial hatch cabinet. However, additional research is needed to determine the practical implications associated with the alternative approach used to alter the microbial load in the hatch cabinet in the present study. Lastly, 16S sequencing is currently underway for a subset of the GIT and fluff samples obtained at DOH and from the ileal and cecal content post-hatch. Implementing a sequencing methodology to support traditional microbiological findings is recommended for future work.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the US Poultry Egg Association for their project support (Project #F096).

References

- 15th Report on Carcinogens. 2021. National Institute of Environmental Health and Safety. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/cancer/roc.

- Aviagen. 2018. Broiler Management Handbook. Available at https://en.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Broiler/Ross-BroilerHandbook2018-EN.pdf.

- Berrang M.E., Cox N..A., Bailey J.S. Measuring air-borne microbial contamination of broiler hatching cabinets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1995;4:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Depner R.F.R., Pontin K.P., Otutumi L.K., Westenhofen M., Borges K.A., Furian T.Q., Do Nascimento V.P., Lovato M. Antimicrobial activity of poultry hatch baskets containing copper inserts. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2021;30 [Google Scholar]

- Gottselig S.M., Dunn-Horrocks S..L., Woodring K.S., Coufal C.D., Duong T. Advanced oxidation process sanitization of eggshell surfaces. Poult. Sci. 2016;95:1356–1362. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham B.D. Development and Evaluation of Models for Hatchery-Mediated Infection of Neonatal Chicks and Alternatives to Formaldehyde Fumigation. PhD Dissertation. University of Arkansas; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Graham B.D., Selby C..M., Forga A.J., Coles M.E., Beer L.C., Graham L.E., Teague K.D., Tellez-Isaias G., Hargis B.M., Vuong C.N. Development of an environmental contamination model to simulate the microbial bloom that occurs in commercial hatch cabinets. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham L.E., Teague K..D., Latorre J.D., Yang Y., Baxter M.F.A., Mahaffey B.D., Hernandez-Velasco X., Bielke L.R., Hargis B.M., Tellez G. Use of probiotics as an alternative to formaldehyde fumigation in commercial broiler chicken hatch cabinets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2018;27:371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Karunarathna R., Ahmed K.A., Liu M., Yu C., Popowich S., Goonewardene K., Gunawardana T., Kurukulasuriya S., Gupta A., Ayalew L.E., Willson P., Ngeleka M., Gomis S. Non-viable chicken embryos: an overlooked niche harbouring a significant source of multidrug resistant bacteria in poultry production. Int. J. Veterinary Sci. Med. 2020;8:9–17. doi: 10.1080/23144599.2019.1698145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kense M.J., Landman W.J.M. Enterococcus cecorum infections in broiler breeders and their offspring: molecular epidemiology. Avian Pathol. 2011;40:603–612. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2011.619165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Kim K.S. Hatchery hygiene evaluation by microbiological examination of hatchery samples. Poult. Sci. 2010;89:1389–1398. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubasova T., Kollarcikova M., Crhanova M., Karasova D., Cejkova D., Sebkova A., Matiasovicova J., Faldynova M., Sisak F., Babak V., Pokorna A., Cizek A., Rychlik I. Gut anaerobes capable of chicken caecum colonisation. Microorganisms. 2019;7 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Bi R., Xiao K., Roy A., Zhang Z., Chen X., Peng J., Wang R., Yang R., Shen X., Irwin D.M., Shen Y. Hen raising helps chicks establish gut microbiota in their early life and improve microbiota stability after H9N2 challenge. Microbiome. 2022;10:14. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01200-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwood S. Studies in hatchery sanitation: 3. The effect of air-borne bacterial populations on contamination of egg and embryo surfaces. Poult. Sci. 1964;43:1567–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Magwood S.E. Studies in hatchery sanitation. Poult. Sci. 1967;46:114–118. doi: 10.3382/ps.0460114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan P., Cox S., Gadde U., Clark F.D., Bramwell K., Watkins S.E. Evaluation of chlorine dioxide-based product as a hatchery sanitizer. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:560–565. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R.H., Christensen H.., Bisgaard M. Transmission and genetic diversity of Enterococcus faecalis during hatch of broiler chicks. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;160:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernot E.F. An Investigation of the Mortality of Incubator Chicks. 1908 [Google Scholar]

- Sander J.E., Wilson J..L., Rowland G.N., Middendorf P.J. Formaldehyde vaporization in the hatcher and the effect on tracheal epithelium of the chick. Avian Dis. 1995;39:152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander J.E., Wilson J.L. Effect of hydrogen peroxide disinfection during incubation of chicken eggs on microbial levels and productivity. Avian Dis. 1999;43:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander J.E., Wilson J..L., Rowland G.N., Middendorf P.J. Formaldehyde vaporization in the hatcher and the effect on tracheal epithelium of the chick. Avian Dis. 1995;39:152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott T.A., Swetnam C.., Kinsman R. Screening sanitizing agents and methods of application for hatching eggs III. Effect of concentration and exposure time on embryo viability. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1993;2:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Selby C.M., Beer L..C., Forga A.J., Coles M.E., Graham L.E., Teague K.D., Tellez-Isaias G., Hargis B.M., Vuong C.N., Graham B.D. Evaluation of the impact of formaldehyde fumigation during the hatching phase on contamination in the hatch cabinet and early performance in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon B.W., Brake J. Hydrogen peroxide as an alternative hatching egg disinfectant. Poult. Sci. 1991;70:1092–1098. doi: 10.3382/ps.0701092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J.B., Coufal C..D., Parker H.M., McDaniel C.D. Disinfection of eggshells using ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide independently and in combination. Poult. Sci. 2010;89:2499–2505. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whistler P.E., Sheldon B.W. Biocidal activity of ozone versus formaldehyde against poultry pathogens inoculated in a prototype setter. Poult. Sci. 1989;68:1068–1073. doi: 10.3382/ps.0681068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Chen Y., Imre K., Arslan-Acaroz D., Istanbullugil F.R., Fang Y., Ros G., Zhu K., Acaroz U. Mechanisms of probiotic Bacillus against enteric bacterial infections. One Health Adv. 2023;1:21. [Google Scholar]