Abstract

The effects of hot air drying (HAD), microwave-assisted hot air drying (MHAD) and vacuum freeze drying (VFD) on the antioxidant and volatile profiles of blueberry pomace (BP) were investigated. The dried BP produced by VFD showed the highest content of antioxidant components and strongest antioxidant activity. MHAD shortened the drying time by 62.5 % with weakened antioxidant profiles. A total of 14 anthocyanin monomers were monitored by UPLC-ESI-MS while 49 typical volatile compounds (VOCs) were identified by HS-GC-IMS. According to orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and variable influence in projection (VIP) models, 21 VOCs were selected as key marker compounds. High temperature (≥ 50 °C) was beneficial to produce characteristic VOCs. The dried BP exhibited enhanced antioxidant profiles and pleasant aroma compared with the whole blueberry fruit. Overall, concerning the cost, antioxidant and aroma profiles, HAD at 60 °C is a suitable technique for the drying of BP.

Keywords: Blueberry pomace, Hot air drying, Microwave-assisted hot air drying, Vacuum freeze drying, Antioxidant profiles, Volatile organic compounds

Highlights

-

•

BP produced by VFD showed the highest content of antioxidant components and activity.

-

•

MHAD improved the drying efficiency but weakened the antioxidant profile.

-

•

HAD at 60 °C was a suitable method to dry BP with low cost and high product quality.

-

•

A total of 14 anthocyanin monomers were monitored by UPLC-ESI-MS in BP.

-

•

In total, 49 VOCs in dried BP were identified with fruit, floral, and roasted aroma.

1. Introduction

Blueberry is a kind of healthy and delicious fruit with a rich source of bioactive compounds and nutrients. However, due to seasonal availability and limited shelf life as fresh fruit, blueberries are processed into juice, jam, wine and vinegar products (Hu, Gong, Li, Chen, & Ye, 2019). The deep processing of blueberry produces large quantities of pomace accounting for approximately 20–30 % of the initial fruit weight (Struck, Plaza, Turner, & Rohm, 2016; Tagliani, Perez, Curutchet, Arcia, & Cozzano, 2019), including a bulk of blueberry skins, some residual pulp and a small amount of seeds (Jaouhari et al., 2024; Santos, Paraíso, Rodrigues, & Madrona, 2021). Blueberry pomace are rich in polyphenols, dietary fibers, proteins, lipids and minerals that can have potential use for effective substance extraction, food ingredients, nutraceutical and cosmetic industries. However, the most of the blueberry pomace currently is still discarded or used as feed and fertilizer (Hu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

With the awareness of sustainable food production and demand for natural and healthy foods, blueberry pomace is a promising source to prepare functional ingredients with increased economic values. Drying of blueberry pomace is an effective method to reduce the waste volume, prolong the shelf life with easier storage and transportation. However, different drying methods influence the contents of the bioactive compounds and functional properties. Previously, Zhang et al. (2023) studied the effects of microwave vacuum drying (MVD) on the individual anthocyanin species and antioxidant activity of blueberry pomace in comparison with hot air drying (HAD), vacuum freeze drying (VFD) and microwave vacuum freeze drying (MFD). The results showed that MVD was superior to other drying methods in terms of phenols and anthocyanins contents as well as antioxidant capacity. Another study investigated the effect of different HAD temperatures (60 °C and 70 °C) and milling conditions (coarse and superfine grinding) on the functional properties of blueberry pomace powders (Calabuig-Jiménez, Hinestroza-Córdoba, Barrera, Seguí, & Betoret, 2022). The results showed that the increasing drying temperature (from 60 °C to 70 °C) did not cause significant degradation of bioactive components and antioxidant capacity. However, superfine grinding significantly reduced the anthocyanins content and 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity. Previous studies focused on the different drying methods of blueberry pomace as well as the contents of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity. In addition, several research studied the microwave assisted hot air drying (MHAD) of blueberry fruit to shorten the drying time (Zielinska & Michalska, 2016; Zielinska, Sadowski, & Błaszczak, 2015). Nonetheless, there are limited research focused on the MHAD for blueberry pomace. Moreover, flavor is a key parameter influencing food quality and consumer preference. Despite the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) of blueberry fruit are systematically studied (Dias et al., 2023; Xu, Liu, Liu, & Wang, 2021), the existing literature does not show any results regarding the VOC profiles of blueberry pomace with different drying methods.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of different drying methods, including HAD, MHAD and VFD on the changes in antioxidant compounds and activity, as well as the aroma profile of blueberry pomace. This work would contribute to the original findings on the dried blueberry pomace products with different functionality and flavor in order to provide a guideline for the oriented processing of blueberry pomace.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Raw materials

Fresh blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum, cv. Bluecrop) were bought from a local market in Tianjin, China in November 2024. The blueberries were washed and the visually damaged samples were discarded. After crushing, pressing and juicing with a juice extractor (Hengbin Machinery Co., Ltd., China), the juice passed through the sieves (2 mm in diameter) from the side and bottom of the extractor while the blueberry pomace were collected from the bottom of the container. The pomace were composed of a bulk of the blueberry skins, some residual pulp and a small amount of seeds. The proportion of the pomace accounted for approximately 20 % (w.b.) of the total blueberry fruit. All the reagents were of analysis grade.

2.2. Preparation of samples

2.2.1. Hot air drying (HAD) of blueberry pomace and blueberry fruit

The hot air drying (HAD) process was conducted in a drying oven at 50 °C,60 °C and 80 °C, respectively. For each treatment, after HAD for 6 h, the samples were weighed per hour and when the weight stayed constant, the drying procedure stopped. It took 24 h at 50 °C,16 h at 60 °C and 8 h at 80 °C, respectively. The final dried sample of 1 g was taken out to determine the moisture contents by gravimetric analysis at 105 °C for 3 h in the oven. The moisture of the dried samples were approximately 6–8 % (w.b.), respectively. Furthermore, for comparison, 200 g of fresh blueberry fruit was dried at 60 °C for 16 h.

2.2.2. Microwave-assisted hot air drying (MHAD) of blueberry pomace

The fresh blueberry pomace of 200 g was spread on a glass plate and put into a microwave oven (213B, Midea Co., Ltd., China). The microwave-assisted procedure was conducted under the treatment of 70 W for 30 min. Then the pomace was transferred to an oven to dry at 60 °C for 6 h with the moisture content reduced to 8 % (w.b.).

2.2.3. Vacuum freeze drying (VFD) of blueberry pomace

The fresh blueberry pomace of 200 g was pre-frozen in a − 80 °C freezer for 24 h and then it was transferred into a vacuum freeze dryer (TF-FD-1, Shanghai Tianfeng Co., Ltd., China) with a condenser temperature at −49 °C and operating pressure of 14 bar for 48 h. The moisture content of VFD sample was approximately 8 % (w.b.).

All the dried samples were crushed through an RT-34 grinder (Hongquan, Hong Kong, China) to pass through a 1.00 mm screen. The final samples were individually sealed in light-proof plastic bags and stored at −4 °C until further analysis. The dried blueberry fruit sample was referred to as HABF. The dried blueberry pomace samples prepared by HAD at different temperatures were denoted as HABP-L (at 50 °C), HABP-M (at 60 °C) and HABP-H (at 80 °C), respectively. In addition, the pomace samples produced from MHAD and VFD were labeled as MHBP and VFBP, respectively.

2.3. Determinations of phenolic compounds

2.3.1. Total phenols

The analysis of total phenols was performed by Folin-Ciocalteu method according to Jaouhari et al. (2024). In brief, a sample of 0.2 g was mixed with 4 mL ethanol-water solution (1: 1, v/v). The extraction was performed at room temperature for 30 min. After filtration, the supernatant was diluted 50-fold for the determination of total phenols by using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and sodium carbonate solution (Na2CO3) with an Evolution 201 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The absorbance set at 765 nm. The results were expressed in grams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 100 g of the dried samples (Li et al., 2024) through calibration curves with GAE.

2.3.2. Total anthocyanins

The total anthocyanins content of the samples was determined by differential pH method (Santos et al., 2021) using pH 1.0 buffer (0.2 mol/L KCl: 0.2 mol/L HCl = 25:67 (v/v)) and pH 4.5 buffer (1 mol/L NaAc: 1 mol/L HCl: H2O = 100: 60: 90 (v/v/v)). Sample extract of 1 mL was diluted in 9-mL buffers with different pH in flasks, respectively. The mixtures were kept away from light for 20 min. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm and 700 nm by a UV–vis spectrophotometer. Results were expressed in milligrams of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) equivalents per 100 g of the dried pomace sample according to the following equation (Tagliani et al., 2019):

| (1) |

where A = (A520-A700) pH 1.0- (A520-A700) pH 4.5; MW = 449.2 g/mol, ε = 26,900 L/mol*cm (molecular weight and molar absorptivity of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside); DF is the dilution factor; V is the solution volume, mL; L = 1 cm (optical path length); m is the mass of dried sample.

2.3.3. UPLC-ESI-MS analysis of monomeric anthocyanin

The monomeric anthocyanin of the samples were determined according to a previous study (Dong et al., 2019). In brief, a weighed sample of 50 mg was extracted with 0.5 mL methanol/water/hydrochloric acid (500: 500:1, v/v/v) solution. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min, ultrasound for 5 min and centrifuged at 12, 000g under 4 °C for 3 min. Then the residue was re-extracted following the above steps. The combined supernatants were filtrated through a 0.22 μm membrane. The analysis was carried out by a UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system (UPLC, ExionLC™ AD; MS, Applied Biosystems 6500 Triple Quadrupole; Framingham, MA, USA) equipped with an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters, MA, USA). The solvent system was water (0.5 % formic acid) and methanol (0.5 % formic acid). The gradient program was set as 95: 5 v/v at 0 min, 50: 50 v/v at 6 min, 5: 95 v/v at 12 min and holding for 2 min, 95: 5 v/v at 14 min. The flow rate was 0.35 mL/min and the column temperature of 40 °C. The autosampler injection volume and total run time were 2 μL and 16 min, respectively. The ESI source temperature was set as 550 °C with the ion spray voltage (IS) of 5500 V and the curtain gas (CUR) of 35 psi. The anthocyanins were detected by scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The data acquisition was performed using Analyst 1.6.3 (Sciex). The identification of the monomeric anthocyanin were determined by the retention time and the quantification was calculated by Multiquant 3.0.3 (Sciex) according to the curves of standard samples.

2.4. Antioxidant activity

2.4.1. DPPH assay

According to Zhang et al. (2017), 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assays was carried out for determination of the antioxidant activity for the samples with some modifications regarding the sample concentration. In brief, DPPH ethanol solution of 0.12 mM was prepared to ensure the absorbance under 0.8. For the extraction, 0.5 g of dried samples and 75 mL of water (25 °C) were mixed thoroughly in a glass flask for 45 min at 25 °C. The mixture was filtered (0.45 μm). A serial diluted samples of 1 mL were mixed with the DPPH ethanol solution of 4 mL. Ethanol was used as a control. After being stored in dark for 30 min, the absorbance at 517 nm was determined with a UV–vis spectrophotometer. The scavenging activity was calculated by the following Eq. (1):

| (2) |

where A0 was the absorbance of DPPH solution with the diluted sample, A1 was the absorbance of the sample mixed with ethanol, A2 was the absorbance of ethanol with DPPH solution, respectively.

2.4.2. Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay was conducted by the method described by Tian et al. (2023). Briefly, solutions of acetate buffer (300 mmol/L), TPTZ (2, 4, 6-tripyridyl-s-triazine; 10 mmol/L in 40 mmol/L HCl) and FeCl3 (20 mmol/L) were mixed in a volume ratio of 10:1:1 to prepare the FRAP regent. After being heated to 37 °C, a volume of 3 mL of the FRAP regent was added to 0.1 mL of the serial diluted samples, respectively. The mixture was incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 10 min. The absorbance was measured at 593 nm. A higher absorbance value indicated a stronger ferric reducing antioxidant power (Zhang et al., 2017).

2.5. HS-GC-IMS analysis

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) of dried blueberry pomace and fruit were analyzed by a HS-GC-IMS FlavourSpec® system (G.A.S, Dortmund, Germany) according to the method of the Yang et al. (2022). The GC system was equipped with a DM-WAX capillary column (30 m × 0.53 mm × 1 μm, Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA) and an auto sampler unit (CTC Analysis AG, Zwingen, Switzerland). Samples of 3 g and internal standard of guaiacol were transferred into a 20-mL headspace vial, and incubated at 60 °C for 20 min with the stirring speed at 500 rpm. Next, a total of 500 μL of headspace gas was injected into the GC injector at 85 °C in splitless mode. Pure nitrogen (99.99 % purity) was employed as the carrier gas. The flow was programmed based on the following sequence: 2 mL/min for 2 min, then linearly ramped up to 100 mL/min within 18 min, and then held for 10 min. The drift tube with the length of 9.8 cm was operated at 45 °C and 5 kV. The flow rate of the drift gas was set as 150 mL/min. The retention index (RI) of each VOC was calculated by n-ketones C4-C9 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd., China) as external references. The VOCs were identified according to the comparison of the RI and the drift time of the compounds in the HS-GC-IMS database (G.A.S, Dortmund, Germany). The relative contents of the VOCs were calculated by peak area normalization.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate. All the data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (mean ± S.D.). Statistical analyses of the experimental data were calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan's multiple-range tests (p < 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed by SIMCA 14.0 software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Total phenols and anthocyanins

As shown in Table 1, in comparison with dried blueberry fruit, dried blueberry pomace had higher contents of total phenols and anthocyanins, which were the main antioxidant components in blueberry. According to literature, those abundant bioactive compounds were mainly distributed in blueberry skin, making up the majority of the pomace (Bamba et al., 2018).The results proved that dried blueberry pomace was a better choice for subsequent use in foods rather than dried whole blueberry fruit. Based on previous studies, the total phenols of dried blueberry pomace varied from 1.3 g/100 g to 28.5 g/100 g (Tagliani et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023) while the total anthocyanins ranged from 357 mg/100 g to 1249 mg/100 g (Hu et al., 2019), depending on the different blueberry cultivars, extraction methodology and drying methods. The total phenols and anthocyanins contents in this study were in accordance with the published research. Overall, VFD had the advantage of high product quality with the highest content of phenols and anthocyanins as a consequence of the vacuum environment and low temperature treatment. On the other hand, the loose internal microstructure and more porous structure for VFD samples made the antioxidant compounds more accessible to the solvent with an easier extraction, resulting in considerably higher total phenols and anthocyanins contents compared to the other samples (Zhang et al., 2023). HABP-H showed the lowest contents of phenols, and anthocyanins due to the degradation of those bioactive compounder under high temperature. MHAD could effectively shorten the drying time by 62.5 % with an enhanced drying efficiency compared with HABP-M. However, a significant loss of anthocyanins and a slight decreased phenols contents were observed for MHBP. Anthocyanins, belonging to the flavonoids family, were reported to be extremely unstable and sensitive to temperature and oxygen. Different authors have proved that anthocyanins were easily degraded when the processing temperature reached to 70 °C (Patras, Brunton, O'Donnell, & Tiwari, 2010) while they were remained when the heating temperature was 50 °C with the inactivated polyphenol oxidase (Skrede, Wrolstad, & Durst, 2000). The result of this research also indicated that HAD at 50 °C was an effective method for the retention of phenols and anthocyanins in blueberry pomace. The changing profile of bioactive compounds in this study were consistent with previous studies.

Table 1.

Contents of total phenols and anthocyanins for dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

| Samples |

Bioactive compounds |

|

|---|---|---|

| Phenols (g/100 g dwb) | Anthocyanins (mg/100 g dwb) | |

| HABF | 5.13 ± 0.32 a | 445 ± 14 b |

| HABP-L | 17.26 ± 0.27 d | 1694 ± 35 e |

| HABP-M | 16.58 ± 0.28 c | 1169 ± 13 d |

| HABP-H | 14.74 ± 0.42 b | 255 ± 16 a |

| MHBP | 14.97 ± 0.23 b | 894 ± 35 c |

| VFBP | 21.72 ± 0.32 e | 1964 ± 21 e |

HABF Hot air dried blueberry fruit, HABP Hot air dried blueberry pomace (L-50 °C, M-60 °C, H-80 °C), MHBP Microwave-assisted hot air dried blueberry pomace, VFBP Vacuum freeze dried blueberry pomace.

Values in the same column followed by different superscripts are significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.2. Analysis of monomeric anthocyanin by UPLC-ESI-MS

As shown in Table 2, a total of 14 anthocyanin monomers were identified in the dried blueberry pomace and fruit, which were derived from the aglycones delphinidin, petunidin, malvidin, cyanidin and peonidin with different sugar moieties, including glucose, galactose, arabinose and xyloside. The results were consistent with published reports (Jaouhari et al., 2024; Santos et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2023). Different drying methods severely affected the composition and content of monomeric anthocyanin in blueberry pomace (Table 3). The three anthocyanin monomers with relatively high content in dried blueberry pomace and fruit were malvidin-3-O-arabinoside, delphinidin-3-O-glucoside and delphinidin-3-O-galactoside. The amount of anthocyanins ranging from 3.05 mg/g to 21.7 mg/g in dried blueberry pomace while it was 7.62 mg/g in dried blueberry fruit. The values were close to the range obtained by other researchers (Hu et al., 2019). Moreover, the total amount of detected anthocyanin monomers decreased significantly with the increasing drying temperature by HAD, especially for the samples dried at 80 °C. The high temperature during the drying process led to the thermal degradation of anthocyanins. In contrast, VFD resulted in the highest content of anthocyanins while MHAD showed lower anthocyanin content in comparison with HAD at 60 °C. Overall, in this study, VFD was the best method to retain the anthocyanin content in blueberry pomace, followed by HAD at 50 °C and 60 °C. The results agreed with a previous study indicating that VFD were superior to reduce the loss of anthocyanins in comparison with HAD (Zhang et al., 2023).

Table 2.

Identification of the monomeric anthocyanin of dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

| Peak | Rt (min) | Molecular ion (M+) | Fragment (m/z) | Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.18 | 465.1 | 303.1 | Delphinidin-3-O-galactoside |

| 2 | 5.66 | 449.1 | 317.1 | Petunidin-3-O-arabinoside |

| 3 | 5.70 | 463.3 | 331.1 | Malvidin-3-O-arabinoside |

| 4 | 6.17 | 449.1 | 287.1 | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside |

| 5 | 6.63 | 435.5 | 303.1 | Delphinidin-3-O-arabinoside |

| 6 | 6.68 | 493.2 | 331.1 | Malvidin-3-O-galactoside |

| 7 | 7.69 | 463.12 | 331.1 | Malvidin-3-O-xyloside |

| 8 | 7.78 | 449.1 | 287.1 | Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside |

| 9 | 8.33 | 463.3 | 301.1 | Peonidin-3-O-galactoside |

| 10 | 8.93 | 465.1 | 303.1 | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside |

| 11 | 8.94 | 433.2 | 301.1 | Peonidin-3-O-arabinoside |

| 12 | 9.05 | 493.1 | 331.1 | Malvidin-3-O-glucoside |

| 13 | 9.30 | 463.3 | 301.1 | Peonidin-3-O-glucoside |

| 14 | 11.20 | 419.1 | 287.1 | Cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside |

Rt, retention time.

Table 3.

Individual anthocyanin content of dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

| Individual anthocyanins (μg/g) |

Different treated samples |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAPF | HABP-L | HABP-M | HABP-H | MHBP | VFBP | |

| Dp-3- gal | 1355 ± 22 b | 2962 ± 57 e | 2496 ± 169 d | 358 ± 18 a | 2297 ± 162 c | 4320 ± 16 f |

| Pt-3- ara | 254 ± 7 b | 378 ± 7 c | 372 ± 2 de | 126 ± 1 a | 355 ± 12 d | 389 ± 5 e |

| Mv-3- ara | 1637 ± 41 b | 3617 ± 140 d | 3521 ± 241 d | 771 ± 9 a | 2976 ± 258 c | 4642 ± 85 e |

| Cy-3- glc | 56.0 ± 5.4 b | 147 ± 3 d | 144 ± 9 d | 25.6 ± 1.2 a | 124 ± 11 c | 210 ± 14 e |

| Dp-3- ara | 628 ± 19 b | 989 ± 10 e | 932 ± 33 d | 188 ± 1 a | 879 ± 43 c | 1127 ± 17 f |

| Mv-3 -gal | 723 ± 20 b | 1563 ± 69 d | 1601 ± 106 d | 393 ± 1 a | 1358 ± 124 c | 2095 ± 4 e |

| Mv-3- xyl | 27.4 ± 2.0 a | 139 ± 5 b | 131 ± 20 b | 12.2 ± 0.4 a | 144 ± 15 b | 190 ± 3 c |

| Cy-3- gal | 303 ± 3 b | 465 ± 4 d | 429 ± 7 c | 107 ± 1 a | 421 ± 24 c | 503 ± 15 e |

| Pe-3- gal | 166 ± 5 b | 349 ± 15 d | 324 ± 10 c | 75.8 ± 4.0 a | 310 ± 16 c | 412 ± 2 e |

| Dp-3- glc | 1336 ± 43 b | 3204 ± 153 d | 2537 ± 220 c | 392 ± 3 a | 2440 ± 214 c | 4627 ± 96 e |

| Pe-3- ara | 35.9 ± 4.9 b | 75.2 ± 4.1 d | 73.7 ± 4.1 d | 14.5 ± 0.9 a | 60.3 ± 4.3 c | 96.3 ± 3.4 e |

| Mv-3- glc | 965 ± 12 b | 2135 ± 153 d | 2134 ± 128 d | 534 ± 22 a | 1762 ± 125 c | 2724 ± 7 e |

| Pe-3- glc | 27.0 ± 2.6 b | 64.0 ± 2.7 c | 68.8 ± 6.0 c | 16.7 ± 0.8 a | 65.3 ± 2.8 c | 83.3 ± 0.7 d |

| Cy-3- ara | 110 ± 3 b | 206 ± 10 e | 175 ± 6 d | 33.2 ± 1.7 a | 156 ± 10 c | 238 ± 1 f |

| Sum of anthocyanins (mg/g) | 7.62 ± 0.05 b | 16.3 ± 0.04 e | 14.9 ± 0.09 d | 3.05 ± 0.06 a | 13.3 ± 0.10 c | 21.7 ± 0.11 f |

HABF Hot air dried blueberry fruit, HABP Hot air dried blueberry pomace (L-50 °C, M-60 °C, H-80 °C), MHBP Microwave-assisted hot air dried blueberry pomace, VFBP Vacuum freeze dried blueberry pomace.

Dp-3-gal, Delphinidin-3-O-galactoside; Pt-3-ara, Petunidin-3-O-arabinoside; Mv-3-ara, Malvidin-3-O-arabinoside; Cy-3-glc, Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside; Dp-3-ara, Delphinidin-3-O-arabinoside; Mv-3-gal, Malvidin-3-O-galactoside; Mv-3-xyl, Malvidin-3-O-xyloside; Cy-3-gal, Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside; Pe-3-gal, Peonidin-3-O-galactoside; Dp-3-glc, Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside; Pe-3-ara, Peonidin-3-O-arabinoside; Mv-3-glc, Malvidin-3-O-glucoside; Pe-3-glc, Peonidin-3-O-glucoside; Cy-3-ara, Cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside.

Values in the same row followed by different superscripts are significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.3. Antioxidant activity

As displayed in Fig. 1 (a), in contrast to dried blueberry fruit, dried blueberry pomace by different drying methods all exhibited enhanced capacity to scavenge the DPPH radical cations indicating an enhanced antioxidant activity. Previously, it was reported that the content of total phenols had a high positive correlation with the antioxidant activity for dried blueberry pomace (Zielinska & Michalska, 2018). In this study, the DPPH scavenging activities of the samples were in accordance with the changing contents of phenols and anthocyanins. Blueberry pomace produced by VFD had the highest DPPH scavenging activity, followed by HAD at 50 °C, 60 °C and MHAD. HAD at 80 °C resulted in the lowest DPPH scavenging activity of blueberry pomace due to the loss of antioxidant compounds.

Fig. 1.

DPPH scavenging activity (a) and FRAP assay (b) of dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

The result of FRAP is shown in Fig. 1 (b). The increasing concentration of sample solution led to the increasing FRAP as a consequence of more antioxidant constituents in the solution. Furthermore, similar trend was found in the FRAP assay in comparison with the DPPH scavenging activity. The highest bioactivity of dried blueberry pomace was achieved by the VFD treatment, followed by the HAD at 50 °C and 60 °C. Subsequently, the samples treated by HAD at 80 °Cand MHAD showed a significant decreasing FRAP. A higher drying temperature and a longer exposure to air during the drying process caused a stronger degradation of the antioxidant substances. Besides, the FRAP of dried blueberry fruit was lower than the pomace. Our results is consistent with previous studies indicating that the dried blueberry pomace can be used as an antioxidant ingredient with enhanced health-beneficial properties in comparison to the whole blueberry fruit (Siddiq, Dolan, Perkins-Veazie, & Collins, 2018; Zielinska & Michalska, 2018).

3.4. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) analysis via HS-GC-IMS

3.4.1. Qualification of VOCs in died blueberry pomace and fruit

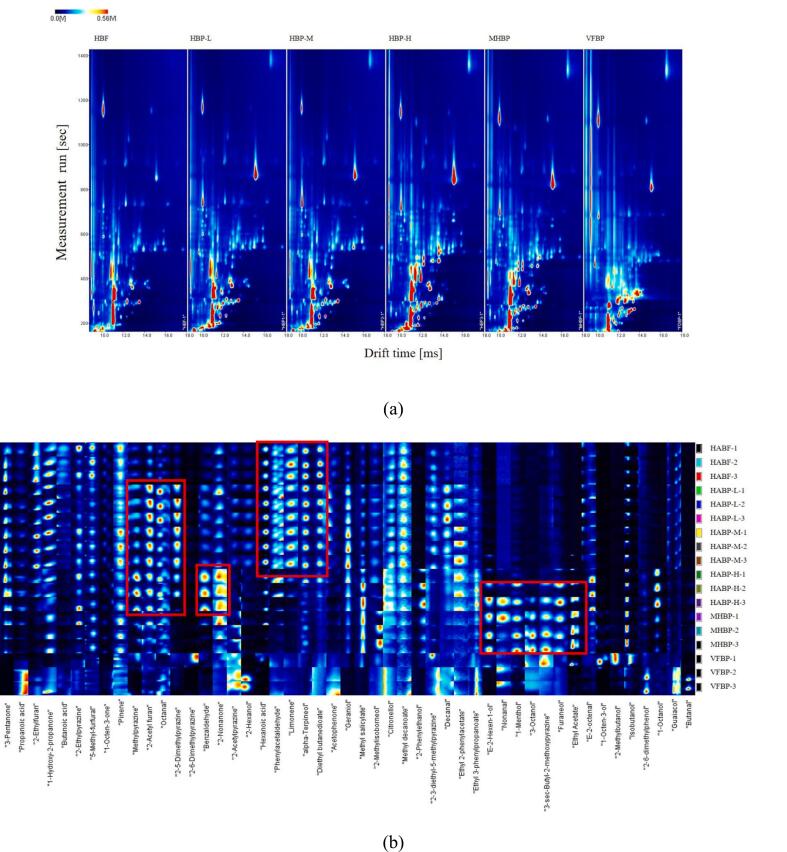

Fig. 2 (a) and (b) showed that the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) of blueberry pomace and fruit were well separated by HS-GC-IMS technique, and most of the signals were distributed in the retention time of 200–600 s with a drift time of 0.08–0.14 s. Based on the spectra, the peak intensities were different among the samples, suggesting that there were differences in the species and the relative content of VOCs. A higher amount of VOCs was detected in blueberry pomace dried by HAD and MHAD, in contrast to blueberry pomace dried by VFD and whole blueberry fruit dried by HAD. The results indicated that the VOCs of blueberry were mostly distributed in the skins rather than the flesh. Furthermore, an appropriate high temperature was conducive for the formation of flavor compounds with increasing types and contents of VOCs. This result was consistent with previous studies indicating that high temperature (50 °C) promoted the Maillard reaction and lipid oxidation, resulting the synthesis of more categories of VOCs (Shen et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2024).

Fig. 2.

Airscape maps (a) and fingerprint of VOCs (b) by HS-GC-IMS in dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

According to the qualitative analysis of VOCs in the samples, 49 typical VOCs were successfully identified, including 13 alcohols, 8 aldehydes, 7 pyrazines, 6 esters, 6 ketones, 3 acids, 2 furans, 2 terpenes and 2 phenolics (Table 4). The results showed that the contents of methylpyrazine, 2-acetyl furan, octanal and 2–5-dimethylpyrazine, increased significantly for blueberry pomace by HAD at different temperatures, while the contents of benzaldehyde and 2-nonanone were extremely high in the samples dried under 80 °C. Moreover, contents of e-2-hexen-1-ol, nonanal, 1-menthol, 3-octanol, 3-s-butyl-2-methoxypyrazine, furaneol, ethyl acetate were observed for blueberry pomace dried at 80 °C and MHAD. Alcohols, such as 2-phenylethanol and 1-octen-3-ol were the secondary metabolites of unsaturated fatty acids oxidation with a further degradation of aldehyde with fruity and floral aroma (Xiong et al., 2024). Aldehydes, were produced by the degradation of fatty acids, Strecker degradation reaction, oxidation and decomposition of lipids (Ren et al., 2025; Xiong et al., 2024). The significant increasing yield of benzaldehyde presented fruity and almond flavor for blueberry pomace dried by HAD at 80 °C. Esters were formed by the chemical reaction of acids and alcohols (Jin et al., 2024), exhibiting the sweet, fruity and floral odor in blueberry. Ketones were primarily produced by the oxidation or degradation of fatty acids (Yin et al., 2022). The increase in heterocyclic compounds such as furans (e.g., 2-acetylfuran) and pyrazines (e.g., methylpyrazine) resulted in the roasted, nutty and caramel aroma of blueberry pomace due to Maillard reaction at high temperatures by HAD (≥60 °C)and MHAD (Ren et al., 2025). The terpenes,i.e., pinene and limonene, contributed to a pleasant herbal and fruity note, especially for whole blueberry fruit and pomace dried under 60 °C. The emerged esters, phenols, and acids after high temperature processing procedure contributed to the sweet and smoke aroma.

Table 4.

VOCs identified in dried blueberry pomace and fruit using HS-GC-IMS.

| No. | Compounds | CAS | Formula | MW | RI | Rt | Dt | Odor characteristics# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols (13) | |||||||||

| 1 | 2-Hexanol | C626937 | C6H14O | 102.2 | 971.4 | 283.75 | 1.5744 | Winey | |

| 2 | α- Terpineol | C98555 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1186.9 | 594.722 | 1.2265 | Floral, herbal | |

| 3 | Geraniol | C106241 | C10H18O | 154.3 | 1249.9 | 741.659 | 1.2283 | Floral | |

| 4 | 2-Methylisoborneol | C2371428 | C11H20O | 168.3 | 1201.1 | 624.923 | 1.2613 | Earthy | |

| 5 | Citronellol | C106229 | C10H20O | 156.3 | 1202.7 | 628.45 | 1.3643 | Rose, citrus | |

| 6 | 2-Phenylethanol | C60128 | C8H10O | 122.2 | 1116.1 | 463.965 | 1.6427 | Floral | |

| 7 | E-2-Hexen-1-ol | C928950 | C6H12O | 100.2 | 879 | 212.97 | 1.4945 | Fruity, banana | |

| 8 | 1-Menthol | C2216515 | C10H20O | 156.3 | 1167 | 554.633 | 1.231 | Minty | |

| 9 | 3-Octanol | C589980 | C8H18O | 130.2 | 1020.8 | 333.876 | 1.7526 | Earthy | |

| 10 | 1-Octen-3-ol | C3391864 | C8H16O | 128.2 | 939.4 | 256.174 | 1.5831 | Wood, citrus, camphor | |

| 11 | 2-Methylbutanol | C137326 | C5H12O | 88.1 | 770.4 | 157.377 | 1.4568 | Winey, onion | |

| 12 | Isobutanol | C78831 | C4H10O | 74.1 | 665.3 | 122.458 | 1.1573 | Ethereal | |

| 13 | 1-Octanol | C111875 | C8H18O | 130.2 | 1065.9 | 389.283 | 1.4602 | Waxy | |

| Aldehydes (8) | |||||||||

| 14 | 5-Methyl-furfural | C620020 | C6H6O2 | 110.1 | 940.1 | 256.771 | 1.1133 | Caramel | |

| 15 | Octanal | C124130 | C8H16O | 128.2 | 960 | 273.543 | 1.4112 | Fatty, soap, lemon, green | |

| 16 | Benzaldehyde | C100527 | C7H6O | 106.1 | 972.9 | 285.139 | 1.4628 | Fruity, almond | |

| 17 | Phenylacetaldehyde | C122781 | C8H8O | 120.2 | 1066.4 | 390.084 | 1.5364 | Green, hyacinth | |

| 18 | Decanal | C112312 | C10H20O | 156.3 | 1154.1 | 529.974 | 1.5379 | Pleasant | |

| 19 | Nonanal | C124196 | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1136.3 | 498.024 | 1.9526 | Fatty, citrus, green | |

| 20 | E-2-octenal | C2548870 | C8H14O | 126.2 | 1067.2 | 391.083 | 1.3345 | Fatty, banana | |

| 21 | Butanal | C123728 | C4H8O | 72.1 | 614.7 | 110.272 | 1.2788 | Pungent, green | |

| Pyrazines (7) | |||||||||

| 22 | 2-Ethylpyrazine | C13925003 | C6H8N2 | 108.1 | 925.9 | 245.583 | 1.1716 | Nutty, woody, roasted | |

| 23 | Methylpyrazine | C109080 | C5H6N2 | 94.1 | 846.9 | 193.941 | 1.4112 | Nutty, cocoa, roasted | |

| 24 | 2–5-Dimethylpyrazine | C123320 | C6H8N2 | 108.1 | 904.1 | 229.668 | 1.4939 | Nutty, roasted | |

| 25 | 2–6-Dimethylpyrazine | C108509 | C6H8N2 | 108.1 | 929.6 | 248.472 | 1.5568 | Cocoa, nutty, roasted | |

| 26 | 2-Acetylpyrazine | C22047252 | C6H6N2O | 122.1 | 1018 | 330.776 | 1.5249 | Popcorn | |

| 27 | 2–3-Diethyl-5-methylpyrazine | C18138040 | C9H14N2 | 150.2 | 1151.5 | 525.267 | 1.2638 | Musty, roasted | |

| 28 | 3-s-Butyl-2-methoxypyrazine | C24168705 | C9H14N2O | 166.2 | 1165.7 | 552.049 | 1.3007 | Musty, green | |

| Ketones (6) | |||||||||

| 29 | 3-Pentanone | C96220 | C5H10O | 86.1 | 699.6 | 132.28 | 1.3423 | Ethereal | |

| 30 | 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone | C116096 | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 664.7 | 122.303 | 1.0532 | Pungent, caramel | |

| 31 | 1-Octen-3-one | C4312996 | C8H14O | 126.2 | 979.9 | 291.72 | 1.2564 | Herbal, mushroom, earthy | |

| 32 | 2-Nonanone | C821556 | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1088.3 | 420.81 | 1.386 | Fruity, floral, slightly fatty | |

| 33 | Acetophenone | C98862 | C8H8O | 120.2 | 1058.5 | 379.536 | 1.5844 | Pungent, floral | |

| 34 | Furaneol | C3658773 | C6H8O3 | 128.1 | 1114 | 460.509 | 1.5956 | Caramel | |

| Esters (6) | |||||||||

| 35 | Diethyl butanedioate | C123251 | C8H14O4 | 174.2 | 1185.6 | 592.043 | 1.2994 | Fruity, apple | |

| 36 | Methyl salicylate | C119368 | C8H8O3 | 152.1 | 1233.5 | 700.343 | 1.2244 | Minty | |

| 37 | Methyl decanoate | C110429 | C11H22O2 | 186.3 | 1322.7 | 957.545 | 1.5511 | Oily, wine, fruity, floral | |

| 38 | Ethyl 2-phenylacetate | C101973 | C10H12O2 | 164.2 | 1241.7 | 720.655 | 1.7752 | Sweet, floral,honey, rose | |

| 39 | Ethyl 3-phenylpropanoate | C2021285 | C11H14O2 | 178.2 | 1321.2 | 952.422 | 1.3431 | Rose, honey, fruity, rum | |

| 40 | Ethyl acetate | C141786 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 600.9 | 107.344 | 1.3456 | Fruity, pineapple | |

| Acids (3) | |||||||||

| 41 | Propanoic acid | C79094 | C3H6O2 | 74.1 | 714.9 | 137.108 | 1.0921 | Pungent, cheese, vinegar | |

| 42 | Butanoic acid | C107926 | C4H8O2 | 88.1 | 832.2 | 186.029 | 1.1567 | Acetic, cheese, butter, fruit | |

| 43 | Hexanoic acid | C142621 | C6H12O2 | 116.2 | 985.1 | 296.641 | 1.6225 | Fatty | |

| Furans (2) | |||||||||

| 44 | 2-Ethylfuran | C3208160 | C6H8O | 96.1 | 736.6 | 144.51 | 1.0518 | Ethereal, coffee, nutty | |

| 45 | 2-Acetylfuran | C1192627 | C6H6O2 | 110.1 | 902.8 | 228.728 | 1.4244 | Almond, caramel, coffee | |

| Terpenes (2) | |||||||||

| 46 | Pinene | C80568 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 953.9 | 268.216 | 1.2194 | Herbal | |

| 47 | Limonene | C138863 | C10H16 | 136.2 | 1059.6 | 380.991 | 1.7029 | Pleasant, pine, lemon | |

| Phenolics (2) | |||||||||

| 48 | 2–6-Dimethylphenol | C576261 | C8H10O | 122.2 | 1139.7 | 503.889 | 1.1343 | Medicinal, rooty, coffee | |

| 49 | Guaiacol | C90051 | C7H8O2 | 124.1 | 1081 | 410.314 | 1.26 | Smoke, vanilla, woody | |

MW, molecular mass; RI, retention index; Rt, retention time; Dt, relative migration time.

Odor characteristics were obtained from the websites: https://www.chemicalbook.com/.

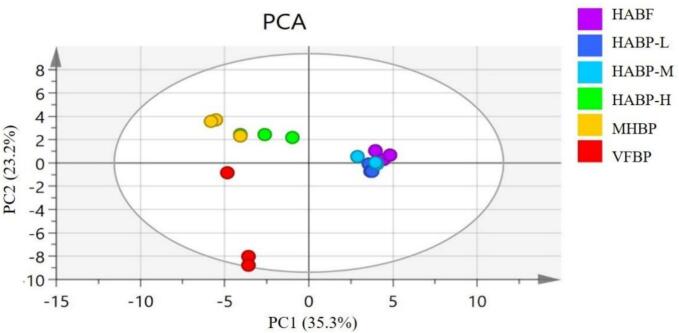

3.4.2. Multivariate statistical analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted according to the peak areas of the VOCs by HS-GC-IMS. As shown in Fig. 3, the cumulative contribution rate of PC1and PC2 was 58.5 % (with PC1 35.3 % and PC2 23.2 %), effectively explaining the similarities and differences between different treatments. PC1 separated HAD at low and medium temperature (50 °C and 60 °C) from MHAD, HAD at high temperature (80 °C) and VFD, whereas PC2 effectively distinguished VFD from other treatments.

Fig. 3.

PCA scores plot of VOCs in dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

A supervised orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed. Fig. 4 (a) shows the OPLS-DA scores of the VOCs in dried blueberry pomace and fruit. The examination indexes of OPLS-DA model (R2X = 0.935, R2Y = 0.956 and Q2 = 0.849) indicated a good fitting accuracy. As shown in Fig. 4 (b), the regression line for Q2 (−0.897) was below zero, suggesting the established model was reliable and stable (He et al., 2024). The OPLS−DA score plot indicated a significant difference of the VOCs of the blueberry pomace dried by MHAD, HAD at high temperature (80 °C) and VFD with a complete separation of VFBP, MHBP and HABP-H. However, the blueberry fruit and pomace dried at low temperature and medium temperature showed similarities. The results were in agreement with the conclusion obtained from the PCA plot. The VOCs with values of variable importance in projection (VIP) >1 were regarded as potential discriminant marker between the samples. According to Fig. 4 (c), the VIP values of the following 21 categories VOCs were >1, including 6 alcohols (2-hexanol, geraniol, 2-phenylethanol, 1-octen-3-ol, isobutanol, and 1-octanol), 5 aldehydes (5-methyl-furfural, octanal, benzaldehyde, e-2-octenal, and butanal), 2 pyrazines (2–5-dimethylpyrazine and 2–6-dimethylpyrazine), 2 ketones (3-pentanone and 1-hydroxy-2-propanone), 1 ester (ethyl acetate), 3 acids (propanoic acid, butanoic acid, and hexanoic acid), 1furan (2-ethylfuran),1 phenolic (2–6-Dimethylphenol). These compounds played an important role to distinguish the blueberry fruit and pomace dried by different methods.

Fig. 4.

OPLS−DA scores (a), displacement test (b) and VIP scores (c) of VOCs in dried blueberry pomace and fruit.

4. Conclusion

Results of this study illustrated that blueberry pomace showed higher contents of antioxidant components and capacity than blueberry fruit. In addition, the VOCs in blueberry pomace was richer than the whole fruit, as a consequence of wide distribution in the skins rather than the flesh. Further, the antioxidant profiles and VOCs of blueberry pomace were drastically altered by different drying techniques. VFD enhanced the antioxidant component contents and capacity of blueberry pomace, followed by HAD under 50 °C, 60 °C, MHAD and HAD at 80 °C, respectively. MHAD could shorten the drying time by 62.5 % and significantly increased the drying efficiency. The increasing temperature of HAD reduced the antioxidant activity and the content of bioactive compounds. A total of 14 anthocyanin monomers were monitored by UPLC-ESI-MS while 49 VOCs were identified from the dried blueberry pomace and fruit through HS-GC-IMS fingerprinting. Conversely, MHAD and HAD increased the contents and categories of VOCs with a high temperature during drying process, resulting in an enhanced sweet, fruity, floral, roasted, nutty and caramel aroma in dried blueberry pomace. Therefore, in consideration of the cost, antioxidant capacity and the product aroma, HAD at 60 °C was a suitable method for the drying of blueberry pomace. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the drying process of blueberry pomace with better antioxidant properties and flavor quality.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yang Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zhihui Zhang: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Qiwen Chen: Software, Methodology. Wenqiang Guan: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Plan Project of Tianjin Education Commission (No. 2021KJ174).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Yang Zhang, Email: zy2019@tjcu.edu.cn.

Zhihui Zhang, Email: zhangzhihui@stumail.tjcu.edu.cn.

Qiwen Chen, Email: 20213651@stu.tjcu.edu.cn.

Wenqiang Guan, Email: gwq18@163.com.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bamba B.S.B., Shi J., Tranchant C.C., Xue S.J., Forney C.F., Lim L. Influence of extraction conditions on ultrasound-assisted recovery of bioactive phenolics from blueberry pomace and their antioxidant activity. Molecules. 2018;23(7):1685. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabuig-Jiménez L., Hinestroza-Córdoba L.I., Barrera C., Seguí L., Betoret N. Effects of processing and storage conditions on functional properties of powdered blueberry pomace. Sustainability. 2022;14(3) doi: 10.3390/su14031839. article 1839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R.P., Johnson T.A., Ferrão L.F.V., Munoz P.R., de la Mata A.P., Harynuk J.J. Improved sample storage, preparation and extraction of blueberry aroma volatile organic compounds for gas chromatography. Journal of Chromatography Open. 2023;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jcoa.2022.100075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong T., Han R., Yu J., Zhu M., Zhang Y., Gong Y., Li Z. Anthocyanins accumulation and molecular analysis of correlated genes by metabolome and transcriptome in green and purple asparaguses (Asparagus officinalis, L.) Food Chemistry. 2019;271:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Yang H., Lan F., Chen R., Jiang P., Jin W. Use of GC-IMS and stoichiometry to characterize flavor volatiles in different parts of Lueyang black chicken during slaughtering and cutting. Foods. 2024;13(12) doi: 10.3390/foods13121885. article 1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Gong H., Li L., Chen S., Ye X. Ultrasound treatment on stability of total and individual anthocyanin extraction from blueberry pomace: Optimization and comparison. Molecules. 2019;24(14) doi: 10.3390/molecules24142621. Article 2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Tang S., Zhao W., Wang S., Sun C., Chen B., Zhu Y. Effects of dried blueberry pomace and pineapple pomace on growth performance and meat quality of broiler chickens. Animals. 2023;13(13) doi: 10.3390/ani13132198. Article 2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaouhari Y., Ferreira-Santos P., Disca V., Oliveira H., Martoccia M., Travaglia F., Bordiga M. Carbohydrases treatment on blueberry pomace: Influence on chemical composition and bioactive potential. Food Science and Technology. 2024;206 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W., Zhao S., Chen X., Sun H., Pei J., Wang K., Gao R. Characterization of flavor volatiles in raw and cooked pigmented onion (Allium cepa L) bulbs: A comparative HS-GC-IMS fingerprinting study. Current Research in Food Science. 2024;8 doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2024.100781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Liang Z., Li X., Liang Z., Fan S., He X.…Guan W. Effect of intermittent treatment with different concentrations of ozone on preservation and antioxidant system of kiwifruit. Food Science. 2024;45(20):239–246. doi: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20240506-017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patras A., Brunton N.P., O’Donnell C., Tiwari B.K. Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods; mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2010;21(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2009.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H., Peng D., Liu M., Wang Y., Li Z., Zhao H., Feng X. Dynamic changes in chemical components, volatile profile and antioxidant properties of Xanthoceras sorbifolium leaf tea during manufacturing process. Food Chemistry. 2025;468 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S.S.D., Paraíso C.M., Rodrigues L.M., Madrona G.S. Agro-industrial waste as a source of bioactive compounds: Ultrasound-assisted extraction from blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) and raspberry (Rubus idaeus) pomace. Acta scientiarum. Technology. 2021;43 doi: 10.4025/actascitechnol.v43i1.55567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C., Cai Y., Wu X., Gai S., Wang B., Liu D. Characterization of selected commercially available grilled lamb shashliks based on flavor profiles using GC-MS, GC × GC-TOF-MS, GC-IMS, E-nose and E-tongue combined with chemometrics. Food Chemistry. 2023;423 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Xiao N., Zhang Q., Tian Z., Li M., Shi W. Evaluation of aroma characteristics of Penaeus vannamei with different drying methods using HS-SPME-GC-MS, MMSE-GC-MS, and sensory evaluation. Food Chemistry. 2024;449 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiq M., Dolan K.D., Perkins-Veazie P., Collins J.K. Effect of pectinolytic and cellulytic enzymes on the physical, chemical, and antioxidant properties of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) juice. Lwt-food. Science and Technology. 2018;92:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.02.008. https://doi [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skrede G., Wrolstad R.E., Durst R.W. Changes in anthocyanins and polyphenolics during juice processing of highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) Journal of Food Science. 2000;65(2):357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb16007.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Struck S., Plaza M., Turner C., Rohm H. Berry pomace - a review of processing and chemical analysis of its polyphenols. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2016;51(6):1305–1318. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliani C., Perez C., Curutchet A., Arcia P., Cozzano S. Blueberry pomace, valorization of an industry by-product source of fibre with antioxidant capacity. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos. 2019;39(3):644–651. doi: 10.1590/fst.00318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Zheng X., Tian X., Wang C., Chen J., Zhou L.…You A. Comparative study of volatile organic compound profiles in aromatic and non-aromatic rice cultivars using HS-GC–IMS and their correlation with sensory evaluation. Lwt-food. Science and Technology. 2024;203 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Liu S., Liu Y., Wang S. Effect of mechanical vibration on postharvest quality and volatile compounds of blueberry fruit. Food Chemistry. 2021;349 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhu H., Chen J., Xie J., Shen S., Deng Y., Zhu J., Yuan H., Jiang Y. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in black teas with different aroma types by using gas chromatography electronic nose, gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry, and odor activity value analysis. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2022;163(15) doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P., Kong Y., Liu P., Wang J., Zhu Y., Wang G., Liu Z. A critical review of key odorants in green tea: Identification and biochemical formation pathway. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2022;129:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhang C., Wei Z., Huang W., Yan Z., Luo Z., Xu X. Effects of four drying methods on the quality, antioxidant activity and anthocyanin components of blueberry pomace. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition. 2023;5(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s43014-023-00150-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xiao W., Ji G., Gao C., Chen X., Cao Y., Han L. Effects of multiscale-mechanical grinding process on physicochemical properties of black tea particles and their water extracts. Food and Bioproducts Processing. 2017;105:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2017.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska M., Michalska A. Microwave-assisted drying of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) fruits: Drying kinetics, polyphenols, anthocyanins, antioxidant capacity, colour and texture. Food Chemistry. 2016;212:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska M., Michalska A. The influence of convective, microwave vacuum and microwave-assisted drying on blueberry pomace physicochemical properties. International Journal of Food Engineering. 2018;14(3) doi: 10.1515/ijfe-2017-0332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska M., Sadowski P., Błaszczak W. Freezing/thawing and microwave-assisted drying of blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) Food Science and Technology. 2015;62(1):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.