Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the biological activities and mechanisms of chlorogenic acid (CGA) in the treatment of septic acute liver injury (SALI) based on the network pharmacology, molecular docking, in vivo studies, and other techniques. Chlorogenic acid and potential related targets of septic acute liver injury were searched from the public databases. Then, the protein–protein interaction (PPI), Gene Ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted. Subsequently, molecular docking was performed to predict the binding of the active compound to the core target. Finally, in vivo experiments were carried out for further validation. A total of 60 common targets were identified between acute septic liver injury and chlorogenic acid, among which 9 common core targets (EGFR, ESR1, GSK3B, PTGS2, TLR4, PPARA, HSP90AA1, ACE, and MMP9) were screened with Cytoscape. Molecular docking indicated that these core targets had good binding activity to chlorogenic acid (− 7.2, − 6.8, − 7.7, − 8.7, − 6.1, − 6.8, − 7.3, − 8.4, and − 8.6 kcal/mol respectively). In the SALI mouse model, chlorogenic acid can improve pathological damage to the liver and apoptosis of liver cells, and anti-inflammatory properties significantly by the TLR4/NF-κB pathway (all P < 0.05). The biological activity and regulatory network of CGA on SALI were revealed, and the anti-inflammatory effect of CGA was verified, which could be associated with the TLR4/NF-κB pathway.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00210-024-03712-5.

Keywords: Chlorogenic acid, Septic acute liver injury, Network pharmacology, Molecular docking, TLR4

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition characterized by a dysregulated host response to infection or injury, leading to systemic inflammation and multiple organ dysfunction, which can progress to septic shock and organ failure (Rello et al. 2017; Napolitano et al. 2018). According to the Global Sepsis Alliance, sepsis affects 47 to 50 million people worldwide annually, with at least 11 million deaths, resulting in one death every 2.8 s, and mortality rates ranging from 15% to over 50% annually (Srzić et al. 2022; Purcarea and Sovaila 2020). Sepsis acute liver injury (SALI) is a common complication that directly contributes to disease progression and mortality, posing a significant challenge in ICUs due to its poor prognosis and high mortality rates (Song et al. 2022; Kobashi et al. 2013). Currently, there is no definitive therapeutic drug available in clinical practice, highlighting the importance of exploring novel treatment options.

Chlorogenic acid (CGA), extracted from traditional Chinese medicines such as honeysuckle and eucommia bark, possesses a wide range of biological activities. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that CGA exhibits antibacterial, antiviral, hepatoprotective, cholagogic, and central nervous system stimulating effects, making it a promising therapeutic agent for septic acute liver injury (Miao and Xiang 2020; Naveed et al. 2018). Researches have indicated that CGA could protect the septic liver injury by LPS (Zhou et al. 2016), but the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Therefore, this study surveyed how CGA improve mice under the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)–induced septic acute liver injury through network pharmacology and animal trails, and the possible mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Main reagents and reagents

BCA Protein Assay Kit (No. P0010), NF-κB p65 antibody (No. AF0246), TLR4 antibody (No. AF8187), and α-tubulin (No. AF2827) were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (China). PrimeScript RT Kit was purchased from TaKaRa (No. RR820A).

Collection of CGA and SALI targets

The molecular formula of CGA was obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (Fig. 1A). The compound was then imported into the Swiss Target Prediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/), with screening conditions set to target genes of the species Homo sapiens with Probability to > 0.5, to identify potential targets of CGA. Based on the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/), the target names of the genes were standardized along with their corresponding protein IDs. By searching the Similarity Ensemble Approach database (https://sea.bkslab.org/), the target genes of CGA were identified, with duplicates removed and merged based on the criterion of MaxTC > 0.4. Ultimately, the potential targets of CGA were identified.

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram of CGA and septic acute liver injury targets

Septic acute liver injury–related genes were obtained from GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) database by using “septic acute liver injury” as keyword and “Homo sapiens” as genus.

Construction of CGA-SALI common targets and protein–protein interaction network

The predicted targets of CGA were intersected with septic acute liver injury genes by the jvenn online tool (https://jvenn.toulouse.inrae.fr/app/example.html) to create a Venn diagram, to obtain drug-disease common targets. The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of drug-disease common targets was constructed by the String 12.0 database (https://cn.string-db.org/), with the species set to “Homo sapiens” and a minimum interaction threshold was set to medium confidence of 0.4, and the network display option was set to “hide disconnected nodes in the network.” Then, the relationship between the target proteins was obtained. Afterwards, figures were imported into the Cytoscape 3.9.1 software, using the CytoNCA plug-in, which is a simple network topology study. The primary core objectives were identified as those targets exceeding the mean value calculated using the local average connectivity (LAC)–based method, and the primary elements were obtained through analysis.

Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analysis

The biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC) of the core potential targets were enriched through Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, while Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was also conducted using the bioinformatics platform (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn). This process aimed to identify the potential biological processes and pathways between CGA and the treatment of the septic acute liver injury.

Molecular docking

The 3D structure of the core target of CGA that acted on SALI was searched from the PDB database (https:// www. rcsb. org/). Convert the document to MOL2 format through Open Bable3.1.1. We downloaded the crystal structures of 9 central targets from the PDB library: EGFR(2xkn), ESR1(1xpc), GSK3B(1q5k), PTGS2(3nt1), TLR4(2z62), PPARA(2p54), HSP90AA1(2qfo), ACE(3nxq), MMP9(4xct). Molecular ligand 2D structure was converted to 3D structure by utilizing the Chem3D software. Auto Dock Tools 1.5.7 were used to dewater, hydrogenate, and charge calculation and determine the atomic rigid structure. Molecular docking was performed to determine the minimum binding efficiency necessary for the combination of drugs and target proteins. Subsequently, Pymol 2.3.4 was employed to visualize the interaction structure resulting from the docking process. Molecular docking was feasible in the natural state when the lowest chemical binding energy was below 0 kJ/mol, and the docking outcomes were considered satisfactory when this energy was less than − 5 kJ/mol.

Animal experiment

Grouping and treatment of animals

All mice used in this experiment were purchased from SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Animal Use License No. SCXK (Jing) 2019–0010), and the animal studies complied with the ethical standards set by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Wannan Medical College (LLSC-2024–073). Throughout the entire experiment, the mice were maintained in an environment with a temperature range of 23–25 °C, a 12-h light/dark cycle, and unlimited access to food and water. After 1 week of acclimatization, mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 10) using a random number table: namely sham group, SALI group, SALI + CGA low-dose (SALI + 20CGA) group, and SALI + CGA high-dose (SALI + 100CGA) group. Twelve hours before CLP modeling, mice in the Sham and SALI groups received saline (20 mg/kg) by intraperitoneally, while mice in the SALI + 20CGA group received CGA (20 mg/kg) and mice in the SALI + 100CGA group received CGA (100 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection. Eight hours after CLP, liver tissues were saved for examination, while the left lobe liver was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and the remaining liver was preserved at − 80℃.

Animal model

Six to 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice, which were specific pathogen-free, were utilized in this study. The septic acute liver injury mouse model was induced through cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), as detailed in previous publications (Rittirsch et al. 2009; Shenhai et al. 2018). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium at a dosage of 50 mg/kg. Under aseptic conditions, a 2-cm midline laparotomy was then performed to expose the cecum. A single puncture was made through the cecum using an 18G needle, positioned between the ligation site and the cecum’s end, allowing a small amount of fecal material to extrude. The cecum was repositioned back into the peritoneal cavity, and the laparotomy was subsequently closed. The sham group underwent laparotomy and bowel manipulation but without the ligation and puncture procedures. All mice were resuscitated with 1 mL of saline. Signs of successful modeling included lethargy, hypersomnia, decreased activity, cold intolerance, piloerection, and tachypnea among the mice.

Histopathological examination

The liver tissue was fixed in paraformaldehyde and then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5-μm-thick slices. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a microscope. Three fields were selected from each slide, and a liver injury pathology score was assigned based on the following criteria: (1) spotty necrosis (scored 0–4, with 0 indicating no injury and 4 indicating severe injury); (2) fatty degeneration (scored 0–3); (3) portal inflammation (scored 0–3); (4) ballooning degeneration (scored 0–3); (5) leukocyte infiltration and fibrin exudation (scored 0–3). The scores were summed to determine the severity of liver injury, ranging from 0 (no injury) to 16 (severe injury).

Western Blotting analysis

The frozen liver tissue was washed and cut into the required amount of tissue in pre-cooled PBS, crushed and homogenized, and the supernatant was extracted. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min and collected. The protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay kit. The extracted proteins were then quantified using an enhanced BCA, heated for denaturation, separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The transfer conditions are 4 ℃ for 90 min. After blocking the membrane with a 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution for 1.5 h, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies (TLR4 at 1:1000 dilution; NF-κB p65 at 1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. Afterwards, the membrane was washed three times with TBST buffer. Then, the membrane was incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with HRP (1:10000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescence detection was applied to visualize protein bands. The membrane was exposed using a Fluor Chem M imaging system, and the relative densities were analyzed with Image J 6.0 analysis software.

RNA extraction and qPCR

Approximately 1 g of mouse liver tissue was weighed and used for total RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent. After extraction, the RNA concentration was measured. The isolated RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Kit. Real-time qPCR amplification of the cDNA was performed using specific primers (pre-denaturation, 95 °C, 5 min; amplification, 95 °C, 5 s; 60°C, 30 s; 40 cycles; melting curve: starting temperature of 60 ℃, ending temperature of 95 ℃, temperature change rate of 0.1 ℃), as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primer sequences of primer pairs

| Forward (5′-) | Reverse(3′-) | |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATG | TTGATGGCAACAATCTCCAC |

| TNF-α | TACTGAACTTCGGGGTGA | ACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACG |

| IL-1β | GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG | TGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACAG |

The qPCR was conducted using the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa). The relative expression of the genes was analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (San Diego, USA) program software. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation ( ‾x ± sd). For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test. When dealing with repeated measurements data, repeated measures ANOVA was employed. The normality test of the data was conducted using the Shapiro Wilk test. The data was calibrated multiple times using Bonferroni correction. For abnormal data, we analyzed them one by one and adopted appropriate processing methods such as deletion, replacement, or adjustment according to the actual situation. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Septic acute liver injury target prediction

A total of 97 targets of CGA were obtained from the database. Additionally, 2920 relevant targets related to septic acute liver injury were retrieved from the Gene Cards database. By using Venn diagram software to intersect the CGA targets with the relevant targets of septic acute liver injury, 60 common targets were identified (Fig. 1B).

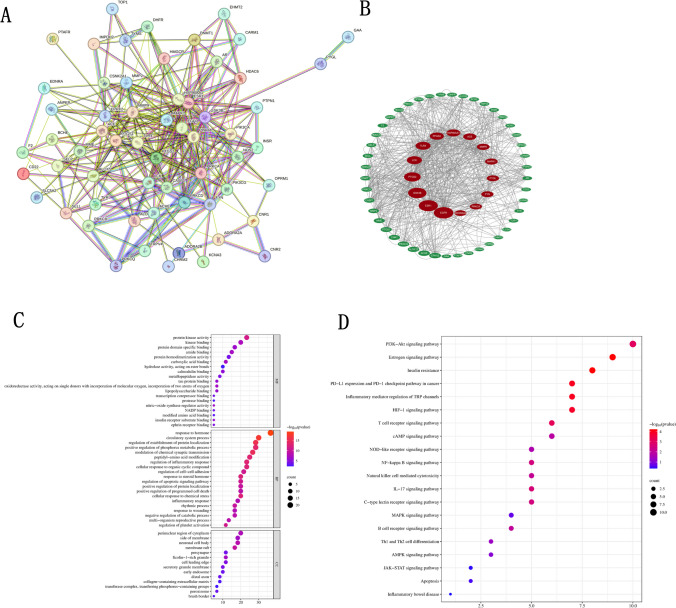

Construction and analysis of PPI network

The STRING database was imported with the 60 intersection targets CGA for the treatment of septic acute liver injury to obtain the PPI network figure (Fig. 2A). The protein interaction information was visualized in a graphical format. Then, the PPI network map conducted was imported into the Cytoscape 3.9.1 software with the CytoNCA plugin. The important target genes were in the central area of the network. As shown in Fig. 2C, and Table 1, the top nine genes were ranked: EGFR, ESR1, GSK3B, PTGS2, TLR4, PPARA, HSP90AA1, ACE, and MMP9 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Network pharmacology diagram of CGA treatment for septic acute liver injury. A Targets intersection PPI network diagram between CGA and septic acute liver injury. B Topological analysis diagram of the targets intersection. C GO enrichment analysis diagram for targets intersection. D Analyzed targets intersection KEGG pathway map

GO and KEGG analysis enrichment analysis

The enrichment analysis of 60 potential targets by GO and KEGG pathway was conducted to reveal the potential mechanism of CGA for the treatment of septic acute liver injury. GO enrichment analysis showed that CGA-SALI treatment affected 1617 entries, including 1375 biological processes (BP), 92 cellular components (CC), and 150 molecular functions (MF). The top 20 GO enrichment pathways are shown in Fig. 2C. In terms of MF, the primary enrichments were in protein kinase activity, kinase binding, and protein domain-specific binding. For BP, significant enrichments were observed in platelet activation, regulation of inflammatory response, blood coagulation, hemostasis, coagulation, reactive oxygen species metabolic process, and peptide-serine phosphorylation. Regarding CC, high enrichment percentages were found in membrane rafts, membrane microdomains, and membrane regions.

The key targets were further subjected to KEGG enrichment analysis, which showed that the target genes were significantly enriched in 116 signaling pathways (count > 2, P < 0.05). The top 20 KEGG pathways were selected for visual analysis in a bubble plot (Fig. 2D) (where the y-axis represents the enriched terms, the x-axis indicates the proportion of genes, larger bubbles represent a higher number of enriched genes, and redder colors indicate more significant enrichment). These pathways were mainly concentrated in cancer, insulin resistance, inflammatory diseases, and signaling pathways such as IL-17 and NF-κB.

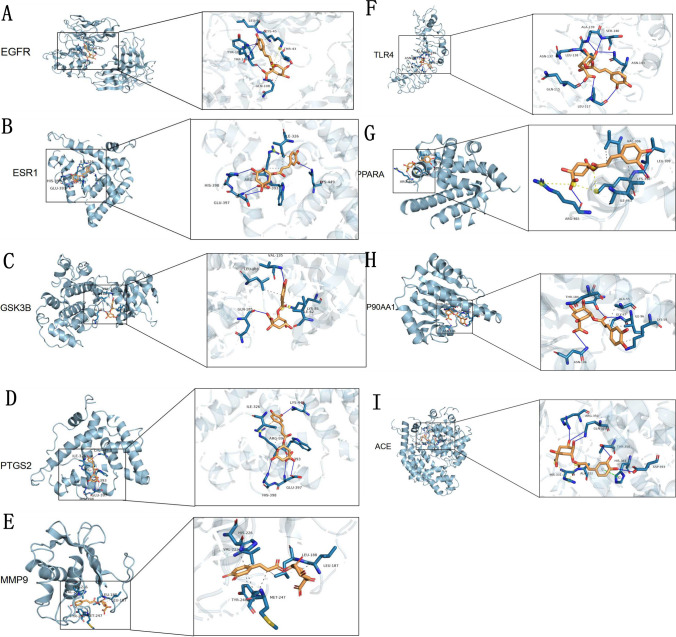

Molecular docking analysis of potential target genes

To further validate the predictive capabilities of bioinformatics, molecular docking techniques were employed to explore the potential of CGA in the treatment of septic acute liver injury, and the key targets with the top nine degrees in the PPI network were selected as receptors for CGA. The most crucial SALI targets (EGFR, ESR1, GSK3B, PTGS2, TLR4, PPARA, HSP90AA1, ACE, and MMP9) were subjected to molecular docking with CGA (Fig. 3A–I). The binding free energies of CGA with EGFR, ESR1, GSK3B, PTGS2, TLR4, PPARA, HSP90AA1, ACE, and MMP9 were − 7.2, − 6.8, − 7.7, − 8.7, − 6.1, − 6.8, − 7.3, − 8.4, and − 8.6 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 2). The free energies of docking binding of the above molecules were all not greater than − 5 kcal/mol, indicating that CGA had good binding ability to the core targets of septic acute liver injury. The cartoon structure diagrams provide an enlarged view of the ligand–protein binding residues.

Fig. 3.

CGA docking with receptor protein molecules. CGA binds to A EGFR, B ESR1, C GSK3B, D PTGS2, E MMP9, F TLR4, G PPAR, H HSP90A1, I ACE, respectively

Table 2.

The binding energy and optimal binding site of the top 9 targets with CGA

| Name | Binding energy(kcal/mol) | Optimal binding site |

|---|---|---|

| EGFR(2xkna) | − 7.2 | A:THR-43:O |

| ESR1(1xpca) | − 6.8 | A:TRP-393:O |

| GSK3B(1q5k) | − 7.7 | A:VAL-135: Nam |

| PTGS2(3nt1) | − 8.7 | A:ASN-39:O |

| TLR4(2z62) | − 6.1 | A:GLN-115:O |

| PPARA(2p54) | − 6.8 | A:LEU-309:O |

| HSP90AA1(2qfo) | − 7.3 | A:GLY-97: Nam |

| ACE(3nxq) | − 8.4 | A:ALA-332: Nam |

| MMP9(4xct) | − 8.6 | A:LEU-187:O |

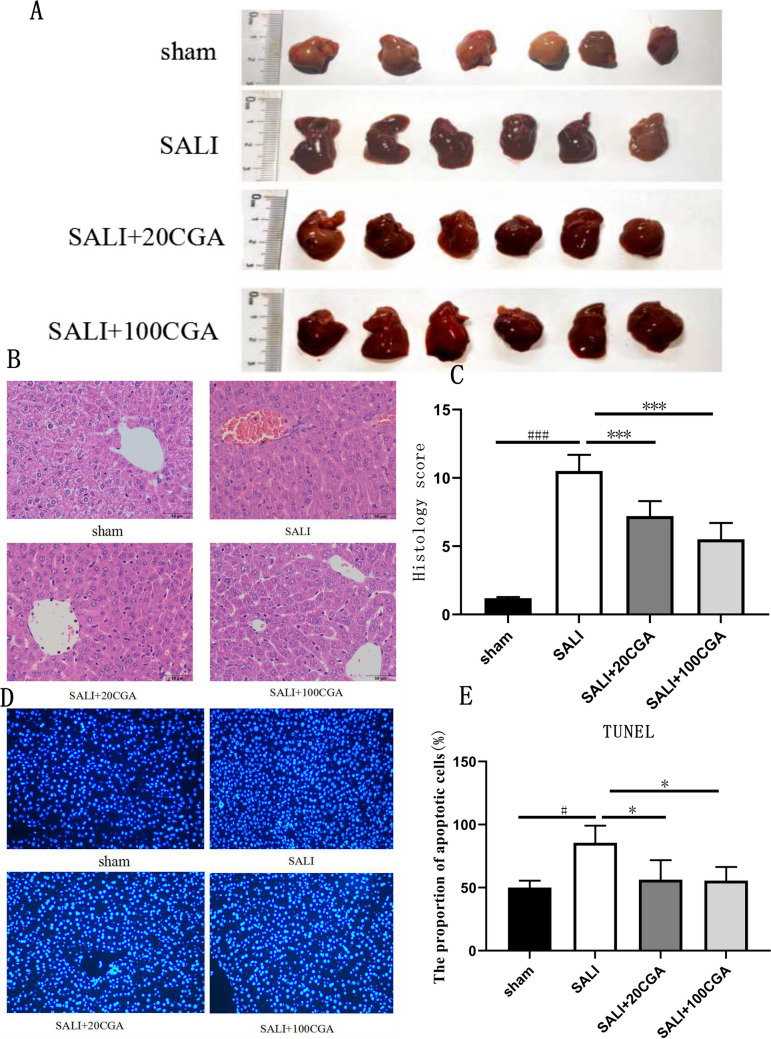

The effect of CGA on liver injury in septic acute liver injury mice

The sham group exhibited no apparent abnormalities, while the SALI group showed visibly darker, swollen, and congested livers. In contrast, the SALI + 20CGA group and the SALI + 100CGA group displayed significant improvement compared to the SALI group; the higher the concentration of CGA, the better the liver protective effect (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Experimental validation of CGA treatment in a mouse model of SALI. A General liver of mice in each group. B HE staining of liver tissues in each group (Original magnification, 400 × . Scale bar = 40 μm); C pathological score of liver tissue in each group. D TUNNEL of liver cells in SALI mice. E The proportion of apoptotic cells n = 10, ± s. ###P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001, ###P < 0.001 vs the sham group; ***P < 0.001 vs the CLP group

HE staining results (Fig. 4B) demonstrated that the liver tissue of the sham group had normal cellular morphology and structure, with intact central veins, clear lobular architecture, and neatly arranged cells, without significant cellular edema or necrosis. In contrast, the SALI group showed disrupted hepatocyte structure, hydropic degeneration, massive inflammatory cell infiltration, punctate necrosis, and prominent bridging necrosis between central veins, indicating liver damage and successful induction of sepsis through cecal ligation and puncture. Treatment with both low and high doses of CGA significantly reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, cellular edema, and necrosis in the liver tissue, with the high-dose group exhibiting lower pathological damage scores compared to the low-dose group. The liver pathological scores (Fig. 4C) indicated a marked increase in SALI pathological damage scores, which were significantly improved by the treatment of CGA, as evidenced by reduced scores for cellular inflammation and edema (P < 0.0001). TUNEL staining results (Fig. 4D, E) showed a significant increase in the apoptotic rate of hepatocytes in the SALI group. However, the treatment of CGA reduced the apoptotic rate in the liver tissue of mice (P < 0.05), indicating a protective effect against cell apoptosis.

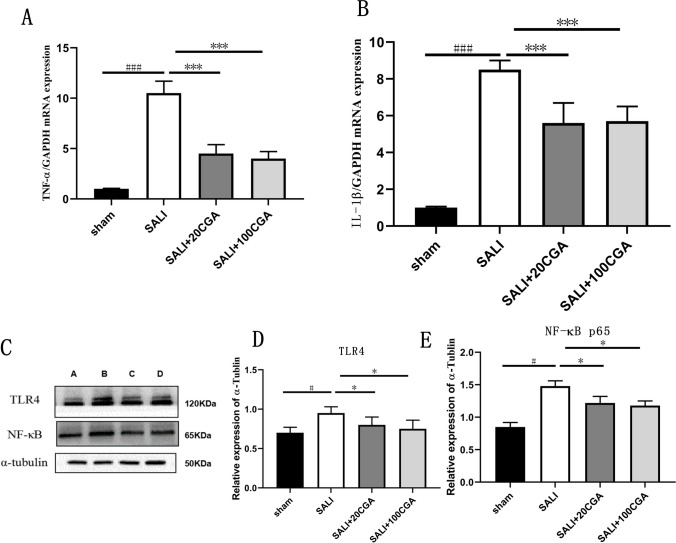

The effect of CGA on inflammatory factors and TLR4/NF-κB pathway in septic acute liver injury

qPCR analysis of liver samples from mice in each group (Fig. 5A–B) showed that compared to the sham group, the SALI group had significantly elevated levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β (P < 0.001). However, both low and high doses of CGA treatment significantly reduced the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β compared to the CLP group (P < 0.05). Further validation of TLR4 and NF-κB protein expression was performed using Western blot analysis (Fig. 5C–E). Compared to the sham group, the SALI group exhibited significantly increased expression of TLR4 and NF-κB proteins (P < 0.05). However, SALI + 20CGA and SALI + 100CGA groups showed significantly reduced expression of TLR4 and NF-κB proteins compared to the SALI group (P < 0.05). In a word, TLR4/NF-κB pathway as a pathway for CGA to improve septic acute liver injury.

Fig. 5.

Effect of CGA on inflammatory factors and TLR4/NF-κB pathway in SALI. A The expression of TNF-α in liver tissue of each group. B The expression of IL-1β in tissue of each group. C The Western blot strip of TLR4 and NF-κB (A represents sham group, B represents SALI group, C represents SALI + 20CGA group, D represents SALI + 100CGA group); D gray level analysis of TLR4 relative to αtubulin; E gray level analysis of NF-κB relative to αtubulin. n = 10. ###P < 0.001 vs the sham group; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs the CGA group. #P < 0.05 vs the sham group; *P < 0.05 vs the CLP group. sham: sham group; CLP: cecum ligation and puncture

Discussion

Septic acute liver injury, a condition characterized by high morbidity in ICUs and accompanied by a substantial mortality rate, remains a challenge in clinical practice due to the lack of definitive and effective therapeutic agents with minimal side effects (Liu et al. 2022; Cong et al. 2023). As a result, considerable research efforts have been directed towards exploring potential treatments for SALI from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) (Liu et al. 2023; Fan et al. 2020). Chlorogenic acid (CGA), a compound abundant in plants such as Lonicera, Artemisia, Eucommia, honeysuckle, coffee, and chrysanthemum, has garnered extensive attention for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antiviral properties (Lee et al. 2013). However, the specific molecular mechanism of CGA treatment for SALI is unclear. So we predicted potential CGA targets and SALI based on PPI network and interaction data. PPI network analysis showed these targets may serve as targets for CGA treatment of septic acute liver injury (such as EGFR, ESR1, GSK3, PTGS2, LCK, TLR4, PPARA, HSP90AA1, et al.). Meanwhile, pathway enrichment analysis was conducted through PPI network to identify key pathways that interact with CGA and SALI. This helps us understand the pathogenesis of SALI and the mechanism of action of CGA. GO enrichment revealed that protein kinase activation, inflammatory response regulation, and membrane rafts processes play important roles in this process. KEGG analysis mainly enriched in cancer pathways, insulin resistance signaling pathways, inflammatory diseases, IL-17, and other signaling pathways. Bagdas’ study revealed that CGA accelerates wound healing in diabetic rats by increasing hydroxyproline content and reducing malondialdehyde, nitric oxide, and glutathione levels, without affecting the expression of superoxide dismutase and catalase (Bagdas et al. 2015). Wang et al. discovered that CGA enhances the permeability of both the plasma membrane and outer membrane of bacterial cells, leading to damage in barrier function, release of cytoplasmic macromolecules, and depletion of intracellular potential, thereby exerting an antibacterial effect (Wang et al. 2022). Karar et al. found that CGA inhibits the activity of ceramidase and Clostridium perfringens, demonstrating its antiviral potential (Karar et al. 2016). Furthermore, CGA downregulates lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase, NF-κB activity, and cytokine expression, contributing to ROS clearance and anti-inflammatory effects (Zheng et al. 2022).

We analyzed the top 9 key targets in terms of Degree value as the core targets for CGA treatment of SALI, and perform molecular docking with CGA separately. The results showed that all of them have good binding performance, indicating that these receptor proteins may be potential sites for CGA to exert therapeutic effects on SALI. Animal experiments also found that the TLR4 with the smallest binding affinity was indeed involved in the mechanism of CGA treatment of SALI. The interaction between proteins and ligands is a complex and intricate process, mainly through (1) geometric space matching: the interaction between proteins and ligands is first based on geometric space matching. The ligand needs to be able to bind to the active site of the protein receptor in an appropriate orientation and conformation, forming a stable complex. (2) Energy matching: During the binding process, the interaction energy between the ligand and the protein receptor (such as van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions) needs to reach a certain balance to ensure the stability of the complex. The specific process of protein ligand interaction is as follows: ligand receptor proximity, orientation, and conformation adjustment. The formation of interactions, conformational optimization, and stability ultimately leads to the formation of a mutually stable complex structure. However, there were some limitations for molecular docking: (1) strong data dependence—machine learning based docking methods require a large amount of data to train the model. If the data is insufficient or of low quality, it may lead to inaccurate model predictions. (2) Limited generalization ability—although machine learning–based methods perform well on certain known complexes, their generalization ability may be limited when faced with new, untrained complexes. (3) Physical rationality issue—when generating a conformation, physical and chemical constraints may be ignored, resulting in the generated conformation being physically unreasonable.

In this study, the CLP model effectively induced septic acute liver injury, as evidenced by gross structural changes such as liver swelling, increased volume, and pronounced congestion, accompanied by significantly elevated levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in liver tissue, similar to previous studies by Arunachalam et al. (2023) using LPS/GalN (lipopolysaccharide/galactosamine) which induced septic acute liver injury respectively. The treatment of CGA significantly alleviated liver damage and improved hepatic pathological injury score, reduced the infiltration and congestion of inflammatory cells in liver tissue, improved the arrangement of hepatic cord structure, and reduced in hepatocyte apoptosis, indicating its protective role in acute liver injury. The protective effect may be attributed to the systemic distribution of CGA following intraperitoneal absorption, with accumulation in the liver to mitigate injury upon occurrence, although CGA was administered via intraperitoneal injection, which may be limited by gastrointestinal absorption efficiency. It was found that a dose of 100 mg/kg CGA had a more significant liver protective effect compared to a dose of 20 mg/kg CGA. However, without higher doses of CGA to verify, it cannot be concluded that 100 mg/kg CGA has the best liver protective effect on SALI mice. In the future, we will conduct more doses of CGA to verify the optimal dose and further study the dose-dependent effects of CGA.

To investigate the underlying mechanism, we measured inflammatory factor levels in liver tissue. Our results showed that CGA could reduce TNF-α and IL-1β levels significantly compared to the SALI group. TNF α and IL-1 β, as common indicators of inflammatory factors, play a crucial role in the inflammatory response. When the levels of TNF α or IL-1 β increase, it indicates that there may be an inflammatory response in the body. IL-1β, an inflammatory mediator, plays a crucial role in mediating liver injury (Busch et al. 2021), while TNF-α, apart from regulating tumor cell growth, also promotes inflammation by activating TNFR1 and TNFR2, leading to apoptosis or necrosis and augmenting the inflammatory response (Puri 1998). Other pro-inflammatory cytokine indicators, such as IL-6, will decrease after CGA treatment, while anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 will increase after CGA treatment, which will be verified by further experiments. Our findings demonstrate that CGA intervention reduced the number of TUNEL-stained apoptotic hepatocytes, indicating its ability to inhibit cell death. Consistent with this, Ranjbary et al. reported that CGA can treat colon cancer by inducing cytotoxicity, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines (Ghorbani et al. 2023).

TLR4, a transmembrane receptor belonging to the Toll-like receptor family, is primarily expressed on immune cells and endothelial cells. TLR4 recognizes various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), triggering immune and inflammatory responses (Zhang et al. 2022). NF-κB, a protein complex present in almost all animal cell types, regulates cellular responses to stimuli such as stress, cytokines, and free radicals. It plays a pivotal role in immune responses to infection and is closely associated with the development of inflammation, autoimmune diseases, and cancer (Quagliariello et al. 2024). In this study, TLR4 emerged as the most frequent inflammatory gene target among the top 9 core targets, with the smallest binding free energy and CGA, which validate the accuracy of the molecular docking results. Existing research demonstrates that CGA inhibits the activation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, subsequently reducing the production and release of inflammatory mediators (Jain et al. 2023). This mechanism holds promise for therapeutic interventions in various diseases, including atherosclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Studies have shown that CGA inhibits the activation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby reducing the production and release of inflammatory mediators (Chen et al. 2022). This mechanism has potential therapeutic applications in various diseases, including atherosclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. In atherosclerosis, CGA inhibits the TLR4/MAPK/NF-κB pathway, activates autophagy, and suppresses inflammation and oxidative stress, protecting vascular endothelial cells from damage. In inflammatory bowel disease, excessive TLR4 activation is considered a key factor in intestinal inflammation.

Network pharmacology research and molecular docking technology explore the key proteins and potential signaling pathways through which CGA exerts its therapeutic effects in SALI by leveraging large databases. The comprehensive analysis of CGA targets, pathways, and molecular docking results offers invaluable insights. Initially, the molecular docking results indicate that CGA exhibits good binding affinity with key proteins such as EGFR, ESR1, GSK3B, PTGS2, TLR4, PPARA, HSP90AA1, ACE, MMP9, and CGA. Relevant studies have also confirmed that CGA can reduce EGFR expression and phosphorylation levels, thereby inhibiting EGFR-mediated cell migration and invasion [28]. Furthermore, by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, CGA can alleviate inflammatory responses and improve the liver function. However, this study has some shortcomings. Firstly, more researches should be needed to determine the role of the core targets in SALI. The second limitation is that we did not investigate the cellular effects of CGA on SALI. In our subsequent research, we will delve deeper into the molecular mechanisms of other core targets regulated by CGA in SALI.

This study has the following limitations. Firstly, the targeted genes predicted by network pharmacology may exhibit false positives. In the future, we will develop more advanced algorithms and models, strengthen in vitro and in vivo experimental verification, and construct a more comprehensive bioinformatics database. Secondly, we will conduct fluorescence immunoassay experiments to further verify the correlation between histology and molecular markers in the later stage. Thirdly, further improvements will be made to the experimental controls, such as adding a positive control group and different doses of CGA groups to verify the dose dependence and pharmacokinetics of CGA drugs. At last, we found that TLR4 molecule participate in CGA therapy for SALI. But we did not explore how TLR4 works; we will construct SALI models using TLR4 knockout mice or TLR4 inhibitors to determine whether CGA exerts a protective effect.

In conclusion, CGA can inhibit the release of inflammatory factors in mouse livers, reduce inflammatory reactions, improve liver function, alleviate hepatocyte edema, and mitigate SALI. Its mechanism of action likely involves inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB pathway. This study provides novel insights and robust evidence for the clinical application of CGA in the treatment of SALI.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PNG 66.8 KB)

(PNG 18.8 KB)

(PNG 8.92 KB)

Author contribution

Shangping Fang and Kecheng Zhai provided research materials and statistics. Huixian Cheng and Jiameng Liu provided the article design and data analysis. Hui Su and Huan Li provided administrative support and article design. Yu Xiang provide the basic experiments such as Western Blot and qPCR. Yangmengna Gao and Renke Sun provide the Network pharmacology and molecular docking. All the authors contributed to the manuscript writing and final review. The writers are accountable for the whole of the work, including making sure that any questions regarding the precision or integrity of any individual section are carefully investigated and resolved. The authors confirm that all data were generated in house and that no paper mill was used.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Project Research Fund of Wannan Medical College (grant number WK2022Z10) and the National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project (grant number 202310368016).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Our studies did not include human participates, human data, or human tissues. All animal experiments conducted were compliant were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Wannan Medical College (LLSC-2024–073).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Hui Su is a co-first author.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arunachalam AR, Samuel SS, Mani A et al (2023) P2Y2 purinergic receptor gene deletion protects mice from bacterial endotoxin and sepsis-associated liver injury and mortality. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 25:471–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdas D, Etoz BC, Gul Z et al (2015) In vivo systemic chlorogenic acid therapy under diabetic conditions: Wound healing effects and cytotoxicity/genotoxicity profile. Food Chem Toxicol 81:54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch K, Kny M, Huang N et al (2021) Inhibition of the NLRP3/IL-1β axis protects against sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12:1653–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YK, Ngoc NTM, Chang HW et al (2022) Chlorogenic acid inhibition of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma metastasis via EGFR/p-Akt/snail signaling pathways. Anticancer Res 42:3389–3402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong S, Yan F, Huaping T (2023) Network pharmacology and molecular docking to explore the potential mechanism of urolithin A in combined allergic rhinitis and asthma syndrome. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 396:2165–2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan TT, Cheng BL, Fang XM et al (2020) Application of Chinese medicine in the management of critical conditions: a review on sepsis. Am J Chin Med 48(6):1315–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Ranjbary A, Bagherzadeh SS et al (2023) Chlorogenic acid induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Biol Rep 50:9845–9857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Saha P, Panda NP et al (2023) Targeting TLR4/3 using chlorogenic acid ameliorates LPS plus POLY I:C-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome via alleviating oxidative stress-mediated NLRP3/NF-kappa B axis. Clin Sci 137:785–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karar MG, Matei MF, Jaiswal R et al (2016) Neuraminidase inhibition of dietary chlorogenic acids and derivatives - potential antivirals from dietary sources. Food Funct 7(4):2052–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobashi H, Toshimori J, Yamamoto K (2013) Sepsis-associated liver injury: incidence, classification and the clinical significance. Hepatol Res 43(3):255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Yoon S, Lee SM (2013) Chlorogenic acid attenuates high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and enhances host defense mechanisms in murine sepsis. Mol Med 18(1):1437–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Sun R, Jiang H et al (2022) Development and validation of a predictive model for in-hospital mortality in patients with sepsis-associated liver injury. Ann Transl Med 10(18):997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yao C, Xie J et al (2023) Effect of an herbal-based injection on 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis: the EXIT-SEP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 183(7):647–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao M, Xiang L (2020) Pharmacological action and potential targets of chlorogenic acid. Adv Pharmacol 87:71–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano LM, Esposito S, De Simone G et al (2018) Sepsis 2018: definitions and guideline changes. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 19(2):117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M, Hejazi V, Abbas M et al (2018) Chlorogenic acid (CGA): a pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomed Pharmacother 97:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcarea A, Sovaila S (2020) Sepsis, a 2020 review for the internist. Rom J Intern Med 58(3):129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri VK (1998) Of mice and MODS, TNF-alpha, and sepsis. Crit Care Med 26:1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quagliariello V et al (2024) Effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on ejection fraction reduction, myocardial and renal NF-κB expression and systemic pro-inflammatory biomarkers in models of short-term doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Journal of Clinical Oncology Suppl 42(16):e24013–e24013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rello J, Valenzuela-Sánchez F, Ruiz-Rodríguez M et al (2017) Sepsis: a review of advances in management. Adv Ther 34(11):2393–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang M, Flierl MA et al (2009) Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc 4:31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhai, Zhengzheng Y, Zhanguo L et al (2018) Intestinal microbiota mediates the susceptibility to polymicrobial sepsis-induced liver injury by granisetron generation in mice. Hepatology 69:1751–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Zhang X, Zhai R et al (2022) Metformin attenuated sepsis-associated liver injury and inflammatory response in aged mice. Bioengineered 13(2):4598–4609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srzić I, Nesek Adam V, Tunjić Pejak D et al (2022) Sepsis definition: what’s new in the treatment guidelines. Acta Clin Croat 61(Suppl 1):67–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Pan X, Jiang L et al (2022) The biological activity mechanism of chlorogenic acid and its applications in food industry: a review. Front Nutr 9:943911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y et al (2022) Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) inhibitors: current research and prospective. Eur J Med Chem 235:114291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Li L, Chen B et al (2022) Chlorogenic acid exerts neuroprotective effect against hypoxia-ischemia brain injury in neonatal rats by activating Sirt1 to regulate the Nrf2-NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Commun Signal 20(1):84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Ruan Z, Zhou L et al (2016) Chlorogenic acid ameliorates endotoxin-induced liver injury by promoting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 469(4):1083–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PNG 66.8 KB)

(PNG 18.8 KB)

(PNG 8.92 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.