Abstract

Background

Gold standards used in validation of new tests may be imperfect, with sensitivity or specificity less than 100%. The impact of imperfection in a gold standard on measured test attributes has been demonstrated formally, but its relevance in real-world oncology research may not be well understood.

Methods

This simulation study examined the impact of imperfect gold standard sensitivity on measured test specificity at different levels of condition prevalence for a hypothetical real-world measure of death. The study also evaluated real-world oncology datasets with a linked National Death Index (NDI) dataset, to examine the measured specificity of a death indicator at levels of death prevalence that matched the simulation. The simulation and real-world data analysis both examined measured specificity of the death indicator at death prevalence ranging from 50 to 98%. To isolate the effects of death prevalence and imperfect gold standard sensitivity, the simulation assumed a test with perfect sensitivity and specificity, and with perfect gold standard specificity. However, gold standard sensitivity was modeled at values from 90 to 99%.

Results

Results of the simulation showed that decreasing gold standard sensitivity was associated with increasing underestimation of test specificity, and that the extent of underestimation increased with higher death prevalence. Analysis of the real-world data yielded findings that closely matched the simulation pattern. At 98% death prevalence, near-perfect gold standard sensitivity (99%) still resulted in suppression of specificity from the true value of 100% to the measured value of < 67%.

Conclusions

New validation research, and review of existing validation studies, should consider the prevalence of the conditions assessed by a measure, and the possible impact on sensitivity and specificity of an imperfect gold standard.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12874-025-02603-4.

Keywords: Validation, Sensitivity, Specificity, Gold standard, Test, Endpoint, Death, Mortality, Prevalence, Suppression

Background

Developing a new test to detect a condition of interest typically requires measuring the diagnostic accuracy of the test, including both sensitivity and specificity, where diagnostic accuracy is measured against an existing gold standard. Sensitivity is defined as the ability of the test to correctly identify patients with the condition, and specificity is defined as the ability of the test to correctly identify patients without the condition. Sensitivity and specificity are understood to be attributes of the test itself [1], and this implies that variation in the prevalence of the condition in populations under study should not affect the theoretical validity of the test.

The gold standard against which a test is measured may be perfect, but new tests may be cheaper, easier, faster, or more accessible than the gold standard itself. If the gold standard is perfect, then testing against it yields an accurate account of the new test’s validity. However, the term “gold standard” should be understood to mean that the standard is “the best available” rather than perfect, and if it is imperfect, it constitutes what has been termed an “alloyed gold standard.”[2] Previous research shows that use of an alloyed gold standard to correct measures of association may either undercorrect or overcorrect, depending on the error structure of the test and the alloyed gold standard [2, 3]. More generally, use of an imperfect gold standard may affect conclusions about the validity of tests measured against it. In practice, the imperfections of a gold standard may be viewed as ignorable, but here we illustrate a practical case where the prevalence of a condition of interest affects the apparent (i.e., measured) validity of a test under conditions of an imperfect gold standard.

The condition of interest in this example is death of a patient. The gold standard for ascertaining the fact and date of death in the U.S. is a Death Certificate. However, it takes time for death certificates to be created and filed, and not every death leads to timely filing of a death certificate [4]. The timeliness of death reporting to the National Center for Health Statistics is known to vary by cause of death [4], and delay may be associated with state death investigation systems and state use of the electronic death registration systems [5]. This means that although a death certificate is the gold standard for establishing the fact and date of death, the absence of a death certificate is not proof of life.

Access to death certificates for research is governed at the state level, with varying costs and requirements that represent a barrier for routine research use. The National Death Index (NDI) aggregates death certificates from all U.S. states, and is the most complete source of certified death information in the U.S [6]. However, use of NDI data for commercial purposes is prohibited, so NDI data is not available for use in profit-oriented research [6]. Commercial research instead relies on other sources of death information, such as health record data, Limited Access Social Security Death Master File records, obituary and burial records, or other sources [7–9]. These sources of death information are not individually complete, but a combination of sources provides a more comprehensive record of deaths that have occurred. To assess the completeness of their combined source, researchers may validate their composite death indicator using the NDI database as the gold standard [8]. But just as time is required for the creation and filing of death certificates, time is also required for NDI to receive state death certificates and to prepare the information for linkage and use in approved noncommercial research. This means that at any given point, deaths have occurred that are not yet represented in the NDI database [8]. This, in turn, means that the NDI database has imperfect sensitivity. Typical uses of NDI data assume a one-year lag to account for this delay [6], but if death information sometimes takes longer than a year to be included in the NDI database, then research that assumes a one-year lag might still be subject to minor insensitivity.

But does that matter? It may. Foundational work by Gart and Buck (1966) demonstrated that assuming a gold standard is perfect when it is not can dramatically perturb estimates of diagnostic accuracy [10]. They showed formally that when a reference test being used as a gold standard is imperfect, observed rates of co-positivity and co-negativity—where both the screening test (i.e., the new test) and the reference test agree—can vary markedly with disease prevalence. Although they did not frame their analysis in terms of sensitivity or specificity, and were considering disease prevalence rather than death prevalence, the underlying mechanism is equivalent, and the effect of extreme prevalence on sensitivity and specificity with an imperfect gold standard can also be shown formally. Here, we revisit the issue by simulating diagnostic accuracy in the high-prevalence setting of real-world oncology research, where overall survival is the gold-standard endpoint, and where real-world oncology data are judged by the validity of their outcomes. The simulation approach illustrates the effects of sampling variability in practical sample sizes, and allows direct comparison of the theoretical impact of an imperfect reference with real-world data validated against the industry-recognized gold standard.

Methods

Simulation

We conducted a simulation study that provided three representations of vital status. The first represented the true vital status of simulated patients. The other two represented vital status as indicated by a Test, and by a Gold Standard, respectively. The true vital status served as the standard against which the performance of the Test and Gold Standard could be evaluated, to ensure the simulations matched expectations given the inputs. Death prevalence was a key model input. Sensitivity and specificity parameters for both the Test and Gold Standard, relative to the true death status, were the other model inputs. Additionally, the Gold Standard was used as a comparator to assess vital status as indicated by the Test, to derive an indicator of measured Test performance when the Gold Standard was defined to be imperfect. The simulation assumed independence of errors in the Test and the Gold Standard, a condition that may not necessarily hold, and where positive correlation of errors would tend to improve the apparent validity of the Test.

Each simulation model consisted of 1,000 replicates, with each replicate simulating 1,000 patients, representing a realistic real-world sample size. Across models, we examined all combinations of the parameters listed in Table 1, shown in the table with the simulated measure for which they supported data generation. The assumption of perfect Test Sensitivity and Specificity was used to isolate the effects of the imperfect Gold Standard. The assumption of perfect Gold Standard Specificity was used to further isolate the effects of imperfect Gold Standard Sensitivity, which is of greater importance in the high death prevalence setting of real-world oncology research. Additional modeling that assumed good but imperfect Test Sensitivity and Specificity was also conducted, to illustrate the effects of interest under real-world test conditions. The primary endpoint for the simulation was the specificity of the Test, as measured against the Gold Standard. The median value of Measured Test Specificity, together with 95% confidence intervals, were computed across the 1,000 replicates in each simulation model.

Table 1.

Simulation parameters

| Simulated Measure | Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| True Vital Status | Death Prevalence: | The true death status for each simulated patient was generated as X∼B(1000,p), where p ranged from 50 to 98% in 2% increments |

| Vital Status per Test | Test Sensitivity: | For patients with a true death status of 1, the Test indicator was generated as X∼B(1000,p), with p set to 100% across conditions, representing a Test with perfect Sensitivity |

| Test Specificity: | For patients with a true death status of 0, the Test indicator was generated as X∼B(1000,p), with p set to 100% across conditions, representing a Test with perfect Specificity | |

| Vital Status per Gold Standard | Gold Standard Sensitivity: | For patients with a true death status of 1, the Gold Standard indicator was generated as X∼B(1000,p), with p ranging from 90 to 99% in 1% increments |

| Gold Standard Specificity: | For patients with a true death status of 0, the Gold Standard indicator was generated as X∼B(1000,p), but was modeled as p = 100% for all conditions, reflecting our assumption that if NDI identifies a patient as deceased, they are deceased |

Application

ConcertAI produces the Patient360™ suite of real-world datasets. The prevalence of death varies greatly in these datasets, because they include patients with different solid tumor malignancies with disease that ranges from early to late stage. ConcertAI has generated an All-Source Composite Mortality Endpoint (ASCME) that draws on multiple real-world data sources, including health record data, Limited Social Security Death Master File records, obituary and burial records, and claims data [11]. ConcertAI has also obtained data from the NDI database, linked to the ConcertAI data, for use in evaluating the performance of its ASCME mortality indicator.

We wished to evaluate specificity of the ASCME mortality indicator across the range of death prevalence parameter values used in the simulation. However, death prevalence in the naturally occurring tumor populations did not cover that full range (50% to 98%). We therefore bootstrapped estimates of the specificity of ASCME compared with an NDI finalized file [6], allowing a standard one-year lag for annual finalization of the NDI data file. We drew from patients identified by ASCME as deceased vs. not, to create cohorts with death prevalence that matched the design of the simulation study (Table 1), with prevalence-based cohorts ranging from 50 to 98% death prevalence. For each level of death prevalence, we sampled randomly with replacement to generate bootstrapped samples of 1,000 patients each, repeated this sampling 1,000 times, and calculated the median value of specificity from each set of 1,000 replicates.

The study was determined to be exempt from IRB review by Advarra Institutional Review Board, Columbia, MD.

Results

Simulation

Results for the Simulation are illustrated in Fig. 1. Measured Test Specificity is plotted against Death Prevalence values from 50 to 98%. Different values of Gold Standard Sensitivity are represented by the plotted lines. As shown, Measured Test Specificity falls as death prevalence increases, and it falls more sharply with lower Gold Standard Sensitivity. However, even with Gold Standard Sensitivity of 99%, Measured Test Specificity is greatly underestimated as prevalence approaches 98% (see the full range of Gold Standard Sensitivity results in Additional file 1 and Additional file 2.) We repeated this simulation with True Test Sensitivity and Specificity set at 95%. Results mirrored those shown in Fig. 1, but with results shifted lower by about 5%, reflecting the effect of the imperfect Test (See Additional file 3 and Additional file 4). Percentile-based confidence intervals are included in Additional files 2 and 4, and illustrate the impact of Gold Standard insensitivity and death prevalence on the uncertainty of point estimates. As shown, although the confidence intervals become larger as Gold Standard Sensitivity falls, the effect of increased prevalence is more pronounced. Even with near-perfect Gold Standard Sensitivity of 99%, as prevalence reaches 90%, the width of the 95% confidence interval exceeds 10%, and at prevalence of 98% it exceeds 34%. We also derived Measured Test Specificity formally as shown in Additional file 5 for comparison with the simulation results. That comparison showed the formally derived and median simulated values to be nearly identical, differing at only the third or fourth decimal.

Fig. 1.

Simulation Estimate of Measured Test Specificity by Death Prevalence, by Gold Standard Sensitivity

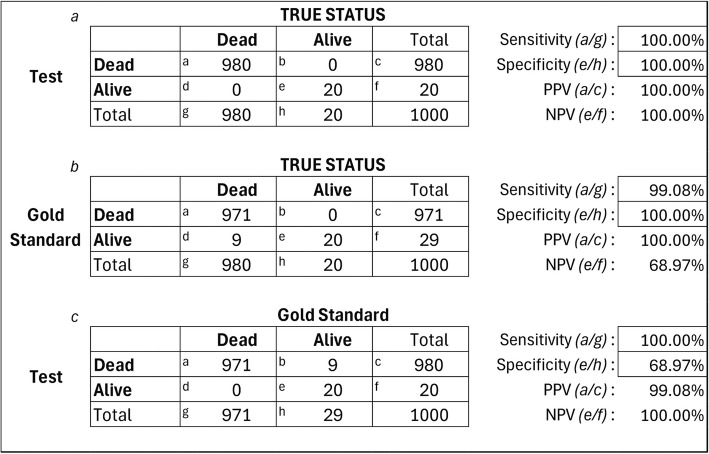

The mechanism by which imperfect Gold Standard Sensitivity leads to suppression of Measured Test Specificity can be seen in the formula in Additional file 5, where a decrease in Gold Standard Sensitivity inflates the denominator more than the numerator, suppressing the estimate of Test Specificity. But the mechanism is also illustrated in Fig. 2. The Figure includes sample results from a single simulation replicate with Prevalence fixed at 98% and Gold Standard Sensitivity fixed at 99%. The Figure includes three embedded contingency tables (Figs. 2a –2c), comparing the Test and Gold Standard vital status to True vital status, and comparing the Test to the Gold Standard. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value appear at the right, along with cell formulas for each statistic.

Fig. 2.

Sample Simulation Result, 98% Prevalence, with 99% Gold Standard Sensitivity and Perfect True Test Performance. NPV: negative predictive value, PPV: positive predictive value

Figure 2a shows the True Test Sensitivity and Specificity to be 100%, and 2b shows the Gold Standard sensitivity to be 99%, both matching the simulation setup. Figure 2c shows the estimated validity of the Test when it is compared against the imperfect Gold Standard. The validity statistics in Fig. 2c show suppression of Test sensitivity from the true value of 100% to the estimated value of 68.97%. This occurs because there are just 20 living vs. 980 dead patients in the sample (Fig. 2a), but the Gold Standard misses about 1% of the deaths, and shows the number of living patients as 29 (Fig. 2c). The difference is shown in cell b of Fig. 2c, where 9 patients correctly classified by the Test as among the dead are incorrectly deemed false positives by the Gold Standard. The Gold Standard in this case underestimates Test Specificity at 20/29 = 68.97%. The same artifact occurs at lower death prevalence but is less evident because of the larger number of truly living patients. See Additional file 6 for an example at 50% prevalence.

We assumed a perfect Test in these examples for illustration. In practice, test measures will be imperfect, and ascertaining how many cases deemed false-positive might be true positives missed by an imperfect gold standard is likely to be difficult. But evidence from the pattern of findings across cohorts with varying prevalence may be instructive.

Application

Results of the bootstrap are presented in Fig. 3. Unlike the simulation, where the Gold Standard had assigned sensitivity of 99%, Fig. 3 represents the effects of the true but unknown sensitivity of the NDI dataset, as well as the effects of the imperfect ASCME death indicator. Echoing findings from the simulation, Fig. 3 clearly shows attenuation of the measured specificity of ASCME in the sample data as death prevalence increases from 50 to 98%, suggesting an artifact of imperfect sensitivity in the NDI gold standard. The rate of degradation of measured specificity aligns with the general simulation pattern presented in Fig. 1. Although the match is not perfect, the real-world data roughly matches the degradation that occurs when Gold Standard Sensitivity is 95.4%, with True Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 95% and 99%, respectively (see Additional file 7 for a simulation model with those parameters compared with the bootstrap shown in Fig. 3). The simulation findings and overall pattern of Fig. 3 suggests that the NDI dataset does not have perfect sensitivity, and that ASCME specificity is underestimated in the analysis not only under conditions of high prevalence where the curve begins to plunge, but also at lower prevalence. The results imply that the true specificity of ASCME at 50% death prevalence is higher than the 95.8% shown in the figure by an extent that approaches the insensitivity of the NDI gold standard.

Fig. 3.

Measured ASCME Specificity Against NDI Gold Standard, by Death Prevalence. ASCME: All-Source Composite Mortality Endpoint, NDI: National Death Index

Discussion

This study examined the impact of an imperfect gold standard on measurement of the accuracy of a new test. The study employed a simulation to illustrate effects that have been previously described formally [10], showing how imperfect sensitivity in a gold standard affects the measured specificity of the new test, and how this effect varies with prevalence, particularly extreme prevalence. The study also included analysis of real-world ConcertAI Patient360™ datasets. The test of interest for the simulation was an indicator of patient death, and in real-world analysis was ConcertAI’s ASCME, measured against an annual NDI dataset. Consistent with the underlying formal models [10, 12], including that shown in Additional file 5, results of the simulation showed increasing underestimation of Test Specificity as sensitivity of the Gold Standard fell, and a multiplicative effect of increasing death prevalence. Findings from the study suggest that if researchers observe a pattern of decreasing specificity with increasing prevalence, this artifact is likely the cause. Even with Gold Standard sensitivity of 99%, Test specificity can be greatly underestimated when condition prevalence exceeds 90%.

Consistent with the simulation findings, results of the real-world data analysis also showed a pattern of decreasing ASCME specificity in samples with increasing death prevalence. Although these results closely mirrored the predictions of the simulation and formal analytic model, the pattern varied slightly, suggesting that the idealized assumptions of independent errors in the test and the gold standard reference may not perfectly hold in practice.

Previous research has assessed how imperfect ascertainment of death can bias survival estimates [13], and how different censoring strategies influence survival estimates when mortality data are incomplete [14]. The current study extends the literature beyond issues of survival bias to examine how imperfect gold standards can distort the apparent validity of real-world oncology outcome measures, and by extension, how this could occur in other settings also. While bias from imperfect reference standards is well-recognized in sequential laboratory testing, such testing often occurs under low prevalence conditions. In contrast, the current study highlights how these biases may be amplified in high prevalence settings. Real-world oncology research often involves high-prevalence endpoints for which perfect gold standards may be unavailable, including disease progression, and as addressed in this paper, death. Our simulation also extends the formal work by illustrating how extreme prevalence in combination with an imperfect gold standard can magnify the uncertainty of point estimates of specificity. Finally, the study shows that the effects theorized in the simulation and the foundational formal work play out largely as predicted in real-world data. In the context of death ascertainment, at least, the assumption of conditional independence appears to hold sufficiently well to preserve the quantitative pattern predicted by the model.

It should be noted that the inverse of the artifact described in this paper can also occur, where test sensitivity is underestimated under conditions of very low prevalence due to imperfect gold standard specificity. For example, Lynch Syndrome is associated with increased risk of colorectal and endometrial cancer, and occurs in less than 1% of the population. However, false positive diagnoses sometimes occur [15]. Assessment of a hypothetical new test of Lynch Syndrome could underestimate the test’s sensitivity if the gold standard assessment included such false positives.

These findings may seem to contradict the widely accepted notion that true sensitivity and specificity are not affected by condition prevalence, but they do not. However, the study clearly shows that sensitivity and specificity as measured by an imperfect gold standard will be affected by condition prevalence, and that the extent of the effect depends on how imperfect the gold standard happens to be. The observations of this study are relevant because real-world measures that serve as gold standards are rarely if ever perfect. Moreover, under conditions of extreme prevalence, there may be no degree of insensitivity of the gold standard that is ignorable. Awareness of the artifact described here can assist researchers and test developers in considering the range of prevalence conditions under which they are assessing the performance of a candidate test, and consider whether to adjust for known levels of imperfection in the reference standard against which the test is evaluated [12, 16]. Findings from this study may also help inform understanding of patterns of specificity and sensitivity in existing research that examines the performance of death indicators in other real-world datasets, and of other test research conducted under either very high or very low prevalence conditions.

A strength of this study is the simulation environment, in which Measured Test Specificity was modeled under conditions in which death prevalence, Gold Standard sensitivity and specificity, and the true test attributes were known. An additional strength was the availability of real-world datasets that included a death indicator and a real-world gold standard, to assess the extent to which the real-world data show a pattern that reflected the simulation model results. The study was limited in not exploring the effects in lower prevalence cohorts, and by not assessing the presence of the artifact in real-world datasets outside of ConcertAI. However, published findings from analysis of other real-world datasets suggest the presence of the artifact in those studies as well [8].

Conclusions

This study shows that use of a gold standard with imperfect sensitivity leads to underestimate of the specificity of new test, an artifact that is more pronounced with higher condition prevalence. Researchers assessing measure validation results should consider the condition prevalence at which a measure was assessed, and should consider the possible impact of an imperfect gold standard in their assessment.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Measured Test Specificity by Prevalence, by Gold Standard Sensitivity (99%–90%), True Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 100%. Additional file 2. Measured Test Specificity (with 95% Confidence Interval) by Gold Standard Sensitivity and Condition Prevalence, for Test with Perfect Sensitivity and Specificity (100%). Additional file 3. Measured Test Specificity by Prevalence, by Gold Standard Sensitivity (99%–90%), True Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 95%. Additional file 4. Measured Test Specificity (with 95% Confidence Interval) by Gold Standard Sensitivity and Condition Prevalence, for Test with Real-World Sensitivity and Specificity (95%). Additional file 5. Formal Derivation of Measured Test Specificity Given Prevalence and Gold Standard Sensitivity and Specificity. Additional file 6. Sample Simulation Result, 50% Prevalence, with 99% Gold Standard Sensitivity and Perfect True Test Performance. NPV: negative predictive value, PPV: positive predictive value. Additional file 7. Measured ASCME Specificity Against NDI Gold Standard, with Simulation Estimate of Measured Test Specificity, Assuming Gold Standard Sensitivity of 95.4%, and Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 95% and 99%, Respectively, by Death Prevalence. ASCME: All-Source Composite Mortality Endpoint, NDI: National Death Index

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Amanda Johns (ConcertAI, LLC) for assisting with manuscript preparation.

Previous publication

Part of this research was presented as a poster at ISPOR Europe 2024.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ASCME

All-Source Composite Mortality Endpoint

- NDI

National Death Index

- U.S.

United States

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection/preparation, and analysis were performed by MSW and LS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MSW and YN, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

ConcertAI, LLC sponsored this study and provided financial support for the conduct of the research and preparation of the article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from ConcertAI, LLC but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data may however be available from ConcertAI, LLC upon reasonable request (https://www.concertai.com/contact-us/). The simulation was conducted in Excel MS365, and can be made available from ConcertAI, LLC upon reasonable request (https://www.concertai.com/contact-us/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt from institutional review board (IRB) oversight by Advarra’s IRB (Columbia, MD). Informed consent was not applicable for the research described in this article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

LS and YN are employed by ConcertAI, LLC. MSW is a paid consultant of ConcertAI, LLC.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gordis L. Epidemiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wacholder S, Armstrong B, Hartge P. Validation studies using an alloyed gold standard. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(11):1251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H. Correcting for exposure misclassification using an alloyed gold standard. Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):406–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer MR, Ahmad F. Timeliness of Death Certificate Data for Mortality Surveillance and Provisional Estimates. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Report No. 001. Washington DC: National Vital Statistics System; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/report001.pdf.

- 5.Rosenbaum JE, Stillo M, Graves N, Rivera R. Timeliness of provisional United States mortality data releases during the COVID-19 pandemic: delays associated with electronic death registration system and weekly mortality. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42(4):536–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Death Index: User's guide (2021) [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ndi/ndi_users_guide.pdf]

- 7.Dong S, Kansagra A, Kaur G, Barcellos A, Belli AJ, Fernandes LL, Hansen E, Ambrose J, Bai C, Zettler CM, He M, Wang CK. Validation of a composite real-world mortality variable among patients with hematologic malignancies treated in the United States. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2025;9:e240023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhang Q, Gossai A, Monroe S, Nussbaum NC, Parrinello CM. Validation analysis of a composite real-world mortality endpoint for patients with cancer in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(6):1281–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis MD, Griffith SD, Tucker M, Taylor MD, Capra WB, Carrigan G, Holzman B, Torres AZ, You P, Arnieri B, et al. Development and Validation of a High-Quality Composite Real-World Mortality Endpoint. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4460–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gart JJ, Buck AA: Comparison of a screening test and a reference test in epidemiologic studies: II. A probabilistic model for the comparison of diagnostic tests. Am J Epidemiol. 1966;83(3):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Slipski L, Dub B, Yu Y, Walker M, Natanzon Y. RWD23 Addition of open administrative claims significantly improves capture of mortality in electronic health record (EHR) – focused real-world data (RWD). Value Health. 2024;27(12):S576.

- 12.Habibzadeh F. On determining the sensitivity and specificity of a new diagnostic test through comparing its results against a non-gold-standard test. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2023;33(1):010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Wang Y, Campbell PT, Flanders WD, Gapstur SM. Ghost-time bias from imperfect mortality ascertainment in aging cohorts. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(10):691–6.e3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hsu WC, Crowley A, Parzynski CS. The impact of different censoring methods for analyzing survival using real-world data with linked mortality information: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2024;24(1):203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strafford JC. Genetic testing for Lynch syndrome, an inherited cancer of the bowel, endometrium, and ovary. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(1):42–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umemneku Chikere CM, Wilson KJ, Allen AJ, Vale L. Comparative diagnostic accuracy studies with an imperfect reference standard - a comparison of correction methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Measured Test Specificity by Prevalence, by Gold Standard Sensitivity (99%–90%), True Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 100%. Additional file 2. Measured Test Specificity (with 95% Confidence Interval) by Gold Standard Sensitivity and Condition Prevalence, for Test with Perfect Sensitivity and Specificity (100%). Additional file 3. Measured Test Specificity by Prevalence, by Gold Standard Sensitivity (99%–90%), True Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 95%. Additional file 4. Measured Test Specificity (with 95% Confidence Interval) by Gold Standard Sensitivity and Condition Prevalence, for Test with Real-World Sensitivity and Specificity (95%). Additional file 5. Formal Derivation of Measured Test Specificity Given Prevalence and Gold Standard Sensitivity and Specificity. Additional file 6. Sample Simulation Result, 50% Prevalence, with 99% Gold Standard Sensitivity and Perfect True Test Performance. NPV: negative predictive value, PPV: positive predictive value. Additional file 7. Measured ASCME Specificity Against NDI Gold Standard, with Simulation Estimate of Measured Test Specificity, Assuming Gold Standard Sensitivity of 95.4%, and Test Sensitivity and Specificity of 95% and 99%, Respectively, by Death Prevalence. ASCME: All-Source Composite Mortality Endpoint, NDI: National Death Index

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from ConcertAI, LLC but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data may however be available from ConcertAI, LLC upon reasonable request (https://www.concertai.com/contact-us/). The simulation was conducted in Excel MS365, and can be made available from ConcertAI, LLC upon reasonable request (https://www.concertai.com/contact-us/).