Abstract

Enhancers, as distal cis-regulatory elements in the genome, have a pivotal influence on orchestrating precise gene expression. Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), transcribed from active enhancer regions, are increasingly recognized as key regulators of transcription. N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most plentiful internal modification in eukaryotic mRNAs, has garnered significant research interest in recent years. With advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies, it has been established that m6A modifications are also present on eRNAs. An accumulative body of evidence demonstrates that aberrant enhancers, eRNAs, and m6A modifications are intimately connected with carcinoma onset, progression, invasion, metastasis, treatment response, drug resistance, and prognosis. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms governing m6A modification of eRNAs in cancer remain elusive. Here, we review and synthesize current understanding of the regulatory roles of enhancers, eRNAs, and m6A modifications in cancer. Furthermore, we investigate the possible roles of eRNAs m6A modification in tumorigenesis based on existing literature, offering novel perspectives and directions for future research on epigenetic regulatory mechanisms in cancer cells.

Keywords: Epigenetics, Enhancer, eRNAs, m6A modifications, Cancer

Introduction

The mechanisms regulating gene expression in higher eukaryotes are extremely complex, with different genes being activated in a cell-type-specific manner, resulting in cell types with specialised morphology and function [1]. Enhancers are DNA sequences consisting of 200–1500 base pairs that function in regulating gene expression, influencing cell identity, and regulating cell-type-specific gene expression [2]. The human genome contains a significantly higher number of enhancers compared to genes [3], with one enhancer capable of regulating multiple genes, while a single gene can be influenced by numerous enhancers [4]. However, aberrant enhancer regulation can lead to dysregulation of gene transcription, ultimately contributing to tumorigenesis and progression. Enhancer remodelling, altered enhancer activity, and even transcription factor (TF) dysregulation, which indirectly alters enhancer activity, can be key factors in tumourigenesis.

In the activated state, the enhancer attracts TFs, recruits RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II), and transcribes to produce eRNAs. eRNAs are widely present in human cells and possess multiple biological functions. In recent years, increasing evidence has revealed that eRNAs can regulate the expression of proximal or distal target genes through a variety of mechanisms [5]. Furthermore, eRNAs can contribute to cancer development by altering gene transcription, as well as protein-RNA interactions to regulate oncogenes, tumour suppressor genes, and cancer signalling pathways [6]. In terms of potential clinical applications, eRNAs are of great value for further research as cancer-related biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

m6A modification is a methylation modification that occurs on RNA, accounting for about 60% of methylation modifications [7]. m6A methylation is primarily regulated by three types of proteins: writing proteins, which catalyse the formation of m6A methylation; erasing proteins, which demethylate RNA; and reading proteins, which recognise m6A methylation sites [8]. The m6A modification plays a crucial role in diverse cellular processes and is closely associated with cancer development [9]. For example, dysregulated m6A modifications significantly influence glycolysis and tumour progression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [10]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that targeted modulation of m6A can enhance anti-tumour therapy efficacy in gastric cancer (GC) [11].

With the advancement of new technologies, m6A modification on eRNAs has been gradually uncovered. Several studies have investigated how m6A modification affects eRNAs, including their stability and transcriptional activation, as well as the possible involvement of m6A-related eRNAs in cancer. In this review, we describe the characterisation of enhancers and eRNAs, their mechanisms of action in transcriptional activation, and their association with cancer. Furthermore, we extensively explore the pathophysiological utility of m6A modification on eRNAs and comprehensively analyse its implications in cancer, offering new perspectives on the epigenetic regulatory mechanisms within cancer cells.

Enhancer and enhancer RNAs

Enhancer

Enhancers, which are non-coding sequences in the genome, have the ability to activate or increase the transcription of linked genes in specific cell types. With the advancement of genomic research, our understanding of enhancers has become more comprehensive. Enhancers are typically characterised by the following features: (1) They can function independently of the direction, distance, and location of the target gene. Generally, enhancers are located in intergenic and intronic regions, with some found in exonic regions. The distance from the target gene can vary from a few hundred bases to several thousand bases. For instance, the distance between the mouse SHH gene and its enhancer ZRS sequence exceeds 1 million base pairs [12, 13]. (2) Enhancers contain specific DNA sequences that allow TF binding. These sequences primarily consist of dense clusters of transcription factor binding sites (TFBs) that bind to cell type-specific TFs, co-regulatory factors, structural proteins, chromatin modifiers, and some enzymes [1]. (3) They are typically tissue-specific or cell type-specific, as demonstrated by the first mammalian cell enhancer found in the intron region of the immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy chain gene [14]. (4) Enhancers are characterised by a lack of nucleosomes and heightened sensitivity to nucleases, such as DNase I [15]. (5) Enhancers are evolutionarily conserved in both sequence and function [16]. Based on these characteristics, approximately 400,000 potential enhancers have been identified in the mammalian genome [17].

Genes can be regulated by either a single enhancer or multiple enhancer elements, which may cluster together to form super-enhancers. Super-enhancers cover larger genomic regions and contain higher concentrations of TFs, mediator coactivators, and histone markers linked to transcriptional activity compared to regular enhancers [18]. In addition to super-enhancers, two specific types of enhancers exist: shadow enhancers and stretch enhancers. Shadow enhancers are essentially a set of enhancers that influence a shared target gene, resulting in overlapping expression patterns in both space and time [19]. Stretch enhancers, identified through computational analysis of type 2 diabetes data, are broad regions of enhancers larger than 3 kb. These enhancers also increase gene expression and function in a cell type-specific manner [20] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of super-enhancers, shadow enhancers, and stretch enhancers

| Feature | Super-enhancers | Shadow enhancers | Stretch enhancers | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic organization | Large enhancer clusters formed by multiple neighboring ordinary enhancers | A set of enhancers on the genome that regulate the same gene |

Large genomic regions characterized by enhancers |

[20–23] |

| Typical size | 8-20 kb | — | Larger than 3 kb | [20–22] |

| Regulatory function | Powerful activation of cellular identity genes | Gene expression stability | Directing cell-specific gene expression | [20–22, 24, 25] |

| Relevance to cancer | Driving aberrant activation of oncogenes to maintain tumor properties | Redundant regulation ensures high expression of oncogenes | Activation of distal oncogenes | [19, 20, 26–29] |

The enhancer can be activated by specific histone modifications. During transcriptional activation, the enhancer recruits two key complexes: the Mll3/Mll4/COMPASS complex and the p300/CBP complex. The former has methyltransferase activity, which mediates the monomethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1), while the latter has acetyltransferase activity and mediates acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac). Upon labelling with H3K4me1 or H3K27ac, the enhancer becomes active. Therefore, H3K4me1 and H3K27ac can serve as markers for enhancers in chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing analyses and can be used for the identification of enhancers in the genome [30, 31]. Enhancers exist in multiple states beyond the activated state, including primed, poised, and inactive states. Activated enhancers feature histone modifications and open chromatin, whereas enhancers in the primed or poised states lack H3K27ac modifications, and silent enhancers exhibit few epigenetic signatures [32]. As cis-acting elements, enhancers can also be modified by methylation, such as the addition of a methyl group at position 5 of the cytosine ring (5-methylcytosine, 5mC). Studies have shown that active enhancers have lower levels of 5mC compared to silent enhancers, though the precise role of 5mC in regulating enhancer activity remains unclear [33].

Before an enhancer can activate a promoter for transcription, it must first establish a link with the promoter to facilitate the exchange of information or material. Several models have been proposed to explain how enhancers communicate with promoters, such as the sliding model, the linking model, the contact model, the action-at-a-distance model, and the kissing model. However, the exact mechanism of enhancer-promoter interaction is still not fully understood [13, 34–37]. Regardless of the interaction mechanism, once enhancers and promoters interact, transcription is activated. Mechanistic models of enhancer-activated transcription can be categorised into four types: (1) enhancer-recruited protein complexes are transferred directly from the enhancer to the promoter; (2) enhancer-mediated protein complexes are recruited to the promoter; (3) enhancers accumulate a high concentration of TFs, coactivators, and chromatin remodelling agents near the promoter, increasing the likelihood of transcriptional activation at the promoter; (4) enhancer-mediated post-translational modification of the promoter [38]. The relationship between enhancers and promoters, and the mechanics of enhancer-activated transcription, remains a challenging area of research that requires further investigation for a deeper understanding.

Enhancer RNAs

In 2010, two research teams independently observed differences in the transcription of enhancers in neurons and macrophages, leading to the discovery of eRNAs. This discovery expanded the non-coding RNA (ncRNA) family and prompted the scientific community to explore eRNAs and their role in transcriptional regulation. To date, it is estimated that humans possess between 40,000 and 65,000 eRNAs [39]. Most eRNAs contain a 5’cap structure but lack a 3’polyadenylation (polyA) modification, typically being no longer than 2 kb, and are bi-directionally transcribed from active enhancers. A small proportion of eRNAs are transcribed unidirectionally from active enhancers; these are relatively long, have both 3’polyA modifications and 5’cap structures, and are generally more stable [40–42]. However, not all enhancers are capable of producing eRNAs. Enhancers that generate eRNAs possess the following characteristics: (1) histone modifications (such as H3K4me1 and H3K27ac) or the presence of certain histone variants (e.g., H2AZ); (2) they are located in open chromatin regions; (3) they are bound by transcriptional coactivators; (4) they exhibit low levels of DNA methylation [43]. Additionally, super-enhancers, which were mentioned earlier, can also be transcribed, and transcription from these super-enhancers can generate larger amounts of eRNAs [44].

eRNAs, along with mRNAs and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), belong to the ncRNA category, sharing similarities and notable differences. mRNAs and lncRNAs are longer, more stable, and typically undergo splicing and 3′ polyA modification, unlike most eRNAs. However, some unidirectional eRNAs transcripts do undergo splicing and 3′ polyA modifications. Studies have shown that mRNAs and lncRNAs are 90–100 times more stable than eRNAs [45]. eRNAs are rapidly degraded by nuclear RNA exosome complexes after synthesis, and this short lifespan complicates their sequencing. To detect eRNAs, techniques such as global run-on sequencing (GRO-seq) and its derivatives, such as precise nuclear run-on sequencing (PRO-seq), have been employed. Researchers have refined methods to detect eRNAs based on their 5’-cap structure, including PRO-cap and 5’GRO-seq. Additionally, nanopore direct RNA sequencing has been applied in the analysis of cellular mRNAs, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), and the detection of various RNA viruses [46], and single-molecule imaging has made breakthroughs in revealing the translation and decay of mRNAs [47], potentially applicable to eRNAs analysis through further technical advancements.

eRNAs are generated in enhancer regions marked by high levels of H3K4me1 and low levels of H3K4me3 histone modifications, in contrast to lncRNAs, which are produced in promoter regions with high H3K4me3 modifications. The active enhancer regions producing eRNAs are associated with high levels of serine-5-phosphorylated RNA Pol II, whereas mRNA-producing promoter regions are linked to serine-2-phosphorylated RNA Pol II [48]. Interestingly, it was found that eRNAs transcribed from super-enhancers can function similarly to lncRNAs. Thus, eRNAs and lncRNAs exhibit functional similarities, leading to the hypothesis that lncRNAs may have evolved from eRNAs, stabilised and acquired functionality over evolutionary time. However, this hypothesis requires further investigation to verify. Additionally, eRNAs expression is positively correlated with the active enhancer marker H3K27ac, which is commonly used to mark active enhancers. Notably, eRNAs themselves serve as a more precise indicator of active enhancers, aiding the identification of new enhancers [49].

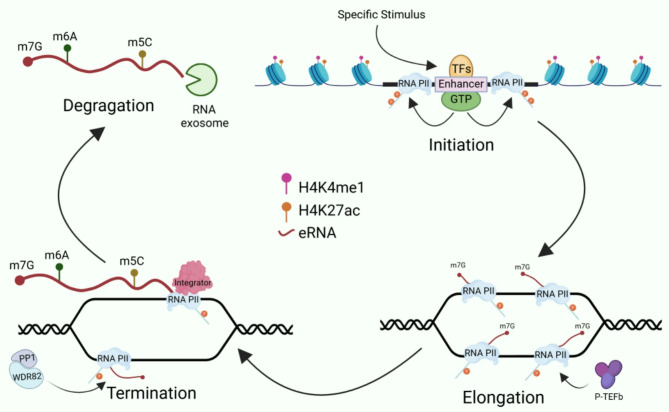

Typically, eRNAs production occurs prior to the transcription of the corresponding gene and involves three key steps. In the first step, TFs and coactivators are recruited. Upon specific stimuli, TFs and coactivators are recruited to interact with the enhancer region, promoting nucleosome remodelling and recruiting additional TFs, cofactors, and complexes (e.g., P300/CBP) [50]. In the second step, histone modification occurs at the enhancer site, with H3K27 acetylation mediated by P300/CBP, which promotes chromatin accessibility, further opening the enhancer region and recruiting RNA Pol II and bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4). In the third step, eRNAs are transcribed, elongated, and processed. BRD4 regulates the recruitment of transcription initiation factors and the formation of transcription mediator complexes, promoting the elongation of RNA Pol II at highly acetylated enhancers [51]. Estrogen receptor-α (ERα), a central TF, associates with estrogen-responsive enhancers in MCF-7 breast cancer cells and selectively recruits a prominent complex of other DNA-binding TFs, ultimately forming a large complex known as MegaTrans, which is essential for eRNAs transcription [52]. However, it remains unclear whether this complexity exists in other cell types. Furthermore, it has been found that eRNAs transcriptional pausing and elongation are mediated by Spt5 and the positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) complex [53]. Additionally, Integrator, a large 12-subunit complex with nucleic acid endonuclease activity, mediates eRNAs transcription termination by interacting with the Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) and cleaving the 3′ end of the primary eRNAs transcript [54]. Once released from chromatin, nascent eRNAs are degraded by nuclear RNA exosome complexes in a 3′-5′ manner. The enzymatic activity of these complexes is supported by two proteins, Rrp44 (Dis3) and Rrp6 (Exosc10). During eRNAs production, harmful DNA/RNA hybrids, such as R-loops, may form, where eRNAs are enzymatically modified to prevent the formation of base pairs, significantly impacting genomic stability. In knockout cells for the Dis3 and Exosc10 genes, R-loop structures in the transcribed regions of eRNAs were significantly increased, indicating that nuclear RNA exosome complexes may play a role in degrading detrimental secondary structures during eRNAs formation [55]. Methylation modifications, including m6A and m5C (5-methylcytosine), have also been detected on eRNAs, influencing their stability and metabolism. At the initial stages of eRNAs transcription, the cap-binding complex (CBC) associates with eRNAs to form the m7G (N7-methylguanosine) cap at the 5′ end (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A diagram illustrates eRNAs transcription process, including modifications and degradation. Following the preliminary attachment of general transcription factors (GTFs) and other TFs in response to specific signals, RNA Pol II is brought to the enhancer to start bidirectional transcription. The enhancer region is rich in H3K4me1 and H3K27ac modifications. The C-terminal domain (CTD) of Pol II in the enhancer region is primarily phosphorylated at the Tyr1 and Ser5 sites, which regulate the pausing and elongation of eRNAs transcription. Integrators can mediate the transcription termination of eRNAs. WDR82 (WD repeat domain 82) and PP1 (phosphatase 1) are engaged in the early ending of eRNAs transcription. Once eRNAs are released from chromatin, they are degraded by nuclear RNA exosome complexes in a 3’-5’ manner. Various RNA modifications, maintaining m5C, m6A, and m7G, are frequently present in eRNAs and affect their stability

The function of eRNAs was initially controversial. Some researchers argued that, due to their low abundance and short half-life, eRNAs were merely “noise” in the chromatin environment opened by enhancers and by-products of gene transcription. However, more studies have refuted this claim. eRNAs are not only markers of active enhancers, but also crucial regulators of transcription. eRNAs play the following roles in transcriptional regulation: (1) regulation of chromatin remodelling. eRNAs recruit Cohesin and bind to its components, SMC3 and RAD21, to regulate chromatin accessibility at the target promoter. Conversely, depletion of eRNAs decreases chromatin accessibility at enhancers and promoters [56]. eRNAs also stabilise enhancer-promoter loops by directly interacting with chromatin loop factors, such as MED12 [57]. (2) Regulation of histone modifications. eRNAs interact with CBP, stimulating its catalytic activity and increasing histone acetylation at enhancers [58]. eRNAs can also activate p300 and induce H3K27 acetylation at enhancers [59]. Similarly, eRNAs interacting with the EZH2 subunit antagonise its nucleosome-binding activity and inhibit the methyltransferase activity of PRC2, thus reducing the deposition of inhibitory H3K27me3 [60]. (3) Recruitment of TFs and co-regulators, thereby modulating their activity. eRNAs can capture TF YY1 and increase its local concentration at transcription sites [61]. eRNAs also interact directly with BRD4 to amplify the interaction between H3K27ac and BRD4, thus maintaining enhancer activity [62]. Recent studies have found that eRNAs capture dissociated TFs through weak RNA-mediated interactions, promoting their recombination with regulatory elements [63]. (4) Direct participation in or interference with transcription, enhancing transcription elongation. eRNAs can interact with the positive elongation factor (P-TEFb) to enhance transcription. In neurons, eRNAs act as a decoy for the negative elongation factor (NELF) after inducing the immediate early gene (IEG), luring it away from the IEG and converting the paused RNA Pol II into productive elongation [64]. Furthermore, eRNAs regulate the proper loading of target sites by CAAA bundles, which control the intermediate heterogeneous cytosolic nuclear ribonucleoprotein L (hnRNPL) [65].

Enhancer and enhancer RNAs in cancer

Enhancer in cancer

Enhancers function as cis-regulatory elements that elevate gene expression by cooperating with promoters to orchestrate transcriptional programmes. With growing research into enhancer biology, it is now well-established that enhancer dysregulation—manifesting as loss of native enhancers, emergence of de novo enhancers, or aberrant enhancer activation/inhibition—plays a pivotal role in tumorigenesis. The disruption of enhancer function in cancer can be broadly attributed to three primary categories: genetic alterations, epigenetic reprogramming, and TF dysregulation.

Firstly, genetic alterations can directly influence enhancer activity. These include copy number variations, chromosomal translocations, amplifications, insertions, deletions, and both intra- and inter-chromosomal inversions. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variants in enhancer regions are now recognised as key contributors to cancer risk. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revealed that a significant proportion of cancer-associated variants—including those linked to lung and breast cancers—are enriched within enhancer regions [66]. For instance, a point mutation within the enhancer region of the *TERT* gene enhances TF binding, leading to elevated telomerase activity and uncontrolled proliferation of tumour cells [67].

In a genome-wide CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screen, researchers identified 66 enhancers within the melanoma genome associated with highly recurrent regions (HRRs), which appear to function as tumour-suppressive elements. These were stratified into four categories using a latent block model: (1) enhancers frequently deleted in patients, (2) enhancers containing recurrent mutations at functional loci, (3) enhancers with sparse mutations, and (4) enhancers with high-level duplications in proximity to oncogenes. Among these, 21 enhancers exhibited copy number gains and 17 showed heterozygous deletions. Functionally, these disrupted enhancers were implicated in the EGFR signalling pathway, central carbon metabolism, and the AMPK signalling cascade, collectively contributing to tumour progression [68]. Similarly, chromatin structure can be altered by enhancer-associated structural variants; in osteosarcoma, abnormal chromatin looping between the *MYC* enhancer and promoter augments oncogenic transcription by increasing spatial proximity [69]. Hence, enhancer amplification, hijacking, or mutation is critical to cancer initiation and progression.

Secondly, alterations in epigenetic modifications can also affect enhancer function, such as aberrant DNA methylation and modifications like histone methylation and acetylation. Aberrant hypermethylation of enhancers associated with tumour suppressor genes, such as CDKN2A, can result in gene silencing, whereas hypomethylation of enhancers linked to oncogenes, such as ERα in breast cancer (BC), facilitates the binding of TFs [70, 71]. TP63 has been associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer (PCa) due to its elevated expression. The methylation level of enhancers in the epithelium of prostate basal cells decreases when TP63 is expressed, but it may be responsible for the enhanced hydroxymethylation of cytosine (hmC) at certain enhancers by TP63. However, not all CpG sites related to TP63 undergo demethylation when TP63 is expressed [72]. In castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), inhibition of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1/KDM1A) blocks the demethylation of the AR pioneer factor FOXA1, which then recruits BRD4 to chromatin, disrupting FOXA1’s global binding and reducing enhancer accessibility. Genetic and epigenetic alterations occur simultaneously in most cancer cells [73].

In addition, abnormalities in TFs, such as mutations, aberrant expression, chimerism, altered function, altered stability, or even crosstalk between TFs, can also cause changes in enhancer activity and thus affect cancer. The overexpression of FOXA1 in BC remodels ER signalling pathway enhancers by recruiting the MLL3 complex, promoting cell proliferation [74]. Consistent with this, ΔNp63 recruits p300 to restructure the enhancer landscape in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), driving squamous differentiation phenotypes [75]. Knockdown of forkhead box protein D2 (FOXD2) in colonoid organs downregulates the expression of more than 200 genes, leading to the loss of colorectal identity and causing colorectal carcinogenesis. Mechanistically, FOXD2 opens chromatin and recruits K3K4 monomethyltransferase (MLL4) to introduce histone modifications, and enhancers and promoters further form differential chromatin loops to regulate chromatin structure, re-edit enhancers, and induce apoptosis [76]. In acute myeloid leukaemia, an in-frame mutation in the C-terminal region of the enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPα) alters its basic leucine zipper structural domain, producing a C/EBPα C-terminal mutant (C/EBPα-Cm). The resulting mutant has a reduced capability to bind with DNA, causing decreased enhancer activity of the ULBP2/5/6 genes and reduced gene expression [77]. This ultimately allows tumour cells to evade natural killer cell-mediated cell lysis.

Abnormal enhancer activity is intricately linked to tumour drug resistance, sensitivity to targeted therapy, and response to chemotherapy. Aberrant enhancer activation can stabilise the continuous expression of oncogenes and maintain survival signalling pathways in tumour cells, thereby reducing the cytotoxic effects of conventional chemotherapy or targeted therapy. For instance, the nuclear matrix binding protein SATB1 mediates the formation of an enhancer-promoter loop of the BCL2 gene, upregulating the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2 and leading to tumour cell resistance to apoptosis-inducing drugs such as cisplatin [78]. Therefore, individual classification based on enhancer genetic variations can provide new biomarkers for predicting treatment responses and guide drug selection. Thus, the enhancer regulatory network plays a “double-edged sword” role in cancer treatment responses: its abnormal activation can drive drug resistance, while targeted intervention may restore treatment sensitivity.

Enhancer-targeted therapeutic strategies can be categorised as follows: (1) development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting enhancers: the BET inhibitor JQ1 suppresses cancer stemness by disrupting enhancer architecture and downregulating BRD4-dependent stemness-related genes. Clinically, combining JQ1 with cisplatin has shown promise in enhancing chemosensitivity and improving patient survival outcomes [79]. Beyond JQ1, other enhancer-targeting agents, including the CDK7 inhibitor THZ1 and the CDK8/CDK19 dual inhibitor cortistatin A, have demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting tumour progression [80, 81]. Furthermore, clinical trials of BET inhibitors in haematologic malignancies have validated the feasibility of enhancer-targeted therapies. (2) Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): ASOs are chemically synthesised nucleic acid analogues [82]. Modified ASOs can precisely downregulate enhancer-derived noncoding RNAs by disrupting enhancer-promoter looping [83]. Therapeutic ASOs exhibit high specificity and the ability to modulate enhancers that are traditionally considered “undruggable”. However, efficient delivery of ASOs to target tissues remains a major challenge for clinical translation [84]. (3) CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing systems: the CRISPR/Cas9 deletion system enables functional studies of enhancers by directly removing specific enhancer regions [85]. Advanced epigenome-editing tools, such as enCRISPRa (enhancer-targeted CRISPR activation) and enCRISPRi(enhancer-targeted CRISPR interference), can remodel epigenetic modifications at enhancers to either activate or suppress their transcriptional activity and downstream target genes [86]. Collectively, small-molecule compounds and ASOs targeting enhancer elements offer potential to restore enhancer homeostasis, modulate eRNAs levels, and thus interfere with tumour progression.

Tumour-specific hyperactive enhancers are frequently enriched at oncogenic loci (e.g., MYC, BCL2), and distinct enhancer signatures across tumour subtypes provide a foundation for precision targeting. However, several practical challenges must be addressed: (1) the vast complexity and functional redundancy of enhancer networks, coupled with high interindividual heterogeneity, complicate therapeutic targeting; (2) the blood-brain barrier penetration capacity of enhancer-targeted inhibitors requires optimisation for central nervous system malignancies.

In terms of potential risks, enhancer-targeted therapies carry inherent risks due to the involvement of enhancers in normal physiological processes. For instance, small-molecule inhibitors may exhibit off-target effects by simultaneously modulating multiple enhancers. BET inhibitors, while suppressing oncogenic enhancers, may inadvertently activate immune-related pathways, triggering excessive inflammatory responses [87]. Additionally, genes regulated by multiple enhancers (e.g., redundant enhancers) may resist single-enhancer inhibition, whereas over-editing could disrupt cellular homeostasis. Enhancer-targeted interventions might also perturb chromatin architecture, affecting non-target genes. For example, targeting the MYC enhancer could dysregulate adjacent noncoding RNAs like PVT1, leading to genomic instability [88]. Despite their transformative potential, the risks of enhancer-targeted strategies stem from the complexity of enhancer regulatory networks and insufficient technological specificity. Future efforts should integrate multi-omics data and machine learning models to predict critical enhancers, coupled with AI-driven design of next-generation inhibitors. Balancing innovation with risk mitigation will be essential to advance precision medicine sustainably.

Enhancer RNA in cancer

eRNAs play an indispensable role in enhancer activation as well as transcriptional regulation. Genetic alterations and epigenetic modifications in the enhancer region can significantly influence eRNAs expression. Growing evidence indicates that abnormal eRNAs expression can drive tumour progression.

eRNAs are crucial in the regulation of gene expression through various mechanisms. In cancer, they can either enhance the transcription of oncogenes or suppress the activity of tumour suppressor genes. For example, insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), an oncogene located on chromosome 13, is essential for driving cell proliferation, clonogenic survival, and anti-apoptotic activity in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). The IRS2-linked enhancer RNA (IRS2e), located adjacent to the IRS2 locus, exhibits elevated expression in OSCC and is associated with unfavourable clinical outcomes [89]. Additionally, research has shown that CCAT1-L, an enhancer RNA embedded in a super-enhancer near the MYC locus, is expressed from a genomic region 515 kb upstream of MYC in human colorectal tumours [90]. Functionally, this long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) facilitates the formation of long-range chromatin loops, thereby modulating MYC transcription. Interestingly, the architecture of these loops undergoes remodelling during cancer progression, leading to dysregulated gene expression. In renal cancer cells, the level of eRNA p53BER2 is lower compared to normal tissues. Silencing p53BER2 mitigates the cytotoxic effects of nutlin-3 in TP53-WT cell lines, as well as the G1-phase blockade and senescence in these cells [91]. Furthermore, additional experiments have indicated that p53BER2 can induce cell-cycle arrest and DNA repair by interacting with BRCA2. Overall, eRNAs regulate oncogenes and tumour suppressors through various transcriptional, epigenetic, and structural mechanisms. Comprehensive studies combining eRNA profiling with functional assays are necessary to better understand their roles in cancer development and treatment.

In addition to regulating tumour-related genes, eRNAs are involved in aberrant signalling cascade response pathways in tumours. CCAT1 is a cancer-associated eRNA targeted downstream of TP63 and SOX2 in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). TP63 and SOX2 co-occupy the promoter and super-enhancer of CCAT1 to activate its transcription in SCC cells, and CCAT1 subsequently forms complexes with TP63 and SOX2. Silencing CCAT1 in SCC significantly impairs cancer cell viability, clonogenic ability, and reduces tumour volume. Further studies found that CCAT1 interacts with SOX2 and TP63 to mediate EGFR expression by binding with its enhancer, consequently activating the MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signalling pathways [92].

Because eRNAs are associated with immune escape and treatment resistance in cancer cells, they can be clinically used as markers of tumour treatment responsiveness and resistance. The eRNA LINC02257 is notably linked to poor prognosis in colorectal adenocarcinoma patients. Abnormal LINC02257 expression alters the tumour immune microenvironment across different tumour categories [93]. Additionally, the relocation of proto-oncogenes to transcriptionally active regions is a common chromosomal rearrangement in cancer. For example, the transfer of the proto-oncogene MYC to the immunoglobulin (IGH) heavy chain motif occurs in 85% of Burkitt lymphoma cases, leading to increased MYC proto-oncogene expression. The IGH/MYC translocation results in overexpression of the eRNA AL928768.3. Overexpression of AL928768.3 increases lymphoma cell growth and resistance to chemotherapy, whereas no such resistance is observed in B-cell lines without this translocation. Targeting AL928768.3 to reduce resistance in Burkitt’s lymphoma may become a common therapeutic approach in the clinic [94].

Furthermore, eRNAs can serve as therapeutic targets and potential biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis. The proto-oncogene MYC is a key driver in leukemogenesis and AML (Acute myeloid leukemia) progression, while the orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1, a tumour suppressor frequently silenced in AML patients, directly binds to MYC super-enhancers, eliminating the necessary coactivators to disrupt AML-selective MYC super-enhancer activity, thus inhibiting tumour cell growth both in vivo and in vitro [95]. To better predict the prognosis of cervical adenocarcinoma (CESC) patients, researchers identified 7936 eRNAs that were distinctly expressed in CESC patients through bioinformatic analysis and further identified a prognostic model composed of eight eRNAs. The 8-eRNA model demonstrates higher accuracy and stability and is an independent prognostic indicator compared to clinicopathological classification alone [96]. The construction of the 8-eRNA model provides important insights for exploring novel therapeutic targets for cervical cancer patients. As of now, many eRNAs in cancer cells remain untapped, and we anticipate further research to uncover the relationship between eRNAs and cancer.

In conclusion, eRNAs emerge as both dynamic biomarkers and functional executors of enhancer activity, playing pivotal roles in oncogenesis, metastatic progression, and therapeutic resistance. Mechanistically, eRNAs directly regulate cell cycle-associated genes to drive tumour cell proliferation and survival. Notably, Li et al. demonstrated that among 626 cancer-associated eRNAs, a significant subset (including CCND1 and MYC targets) exhibit potent pro-proliferative effects, with experimental eRNAs suppression leading to marked downregulation of these oncogenes and subsequent suppression of PCa growth [97]. Importantly, eRNA quantitative trait loci (eRNA-QTLs) show spatial colocalisation with cancer risk variants, establishing their regulatory significance in tumourigenesis. Beyond primary tumour growth, eRNAs orchestrate metastatic programmes through microenvironmental remodelling. This is exemplified in BC models where eRNA-mediated activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) genes promotes invasive phenotypes [98]. Furthermore, eRNAs drive therapeutic resistance via multimodal regulation of drug metabolism enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 family) and survival signalling cascades. Illustrating this paradigm, Shi et al. have characterised the dual functionality of super-enhancer-derived LINC02454 in modulating temozolomide (TMZ) sensitivity through epigenetic and post-transcriptional mechanisms in glioma [99]. These collective findings position eRNA-targeted therapies as a transformative frontier in oncology. Strategic modulation of eRNAs networks may overcome current limitations in precision oncology approaches, particularly for treatment-refractory malignancies.

RNA m6A modification

RNA m6A modification

Post-transcriptional modifications, a crucial domain of epigenetics, have come out as key regulators of numerous physiological and pathological processes. According to MODOMICS, over 170 distinct chemical modifications of RNA had been established in living organisms by the end of 2023 [100]. Among these, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) stands out as the most prevailing, abundant, and evolutionarily conserved internal co-transcriptional modification in eukaryotic RNAs. As a dynamically reversible process, RNA m6A modification is catalyzed by writer proteins, removed by erasers, and recognized by reader proteins, predominantly accumulating near termination codons, the 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR), and internal exons. At the molecular level, m6A influences almost every dimension of RNA metabolism, including mRNA translation, degradation, splicing, folding, nuclear export, stabilization, and decay. Moreover, m6A modifications play integral roles in diverse biological processes, such as transcriptional regulation, intracellular signaling, and the DNA damage response [101–103]. In the last several years, accumulating researches have demonstrated that RNA m6A modification further modulates tumor development by regulating tumor cell metabolism, underscoring its significance in cancer biology.

Regulators of m6A (writer, eraser, reader)

Writer

The most extensively studied m6A-modifying complex is the m6A methyltransferase complex, which comprises methyltransferase-like protein 3 (METTL3), methyltransferase-like protein 14 (METTL14), and the cofactor Wilms Tumor 1 Associated Protein (WTAP). Each of these components plays a crucial role in the enzymatic process. In recent years, additional accessory proteins participating in m6A modification have been discovered, maintaining methyltransferase-like protein 16 (METTL16), methyltransferase-like protein 5 (METTL5), human methyltransferase (ZCCHC4), RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15), and Vir-like m6A methyltransferase-associated protein (VIRMA/KIAA1429). These proteins contribute to m6A deposition on various structured RNAs, such as U6 snRNA and 28 S rRNA, and, under certain conditions, within mRNA introns [104–108].

Eraser

m6A erasers function as demethylases, removing m6A modifications via oxidative reactions that require ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) as a cofactor and α-ketoglutarate as a co-substrate. The finding of the first m6A eraser, fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO), by Professor He Chuan in 2011 provided compelling evidence that m6A modifications are dynamically reversible, leading to a surge in m6A research. The second major m6A eraser, alkylation repair homolog 5 (ALKBH5), was discovered in 2013. Like FTO, ALKBH5 belongs to the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family. Aside from FTO and ALKBH5, other erasers such as ALKBH1 and ALKBH3 have been identified. ALKBH1 is involved in tRNA demethylation [109], whereas ALKBH3 functions as an m1A demethylase (N1-methyladenosine), acting on both m1A residues in tRNA and m6A modifications in RNA [110, 111].

Reader

m6A-modified readers encompass a varied range of proteins, containing the YTH domain-containing family (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2), the insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein family (IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3), the HNRNP family (HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, HNRNPG), eukaryotic translation initiation factors (eIF3, eIF4E, eIF4G), and embryonic lethal abnormal visual-like protein 1 (ELAVL1). Recently, a novel m6A reader, proline-rich coiled-coil 2 A (Prrc2a), has also been identified. These readers regulate downstream RNA metabolism either by indirectly binding RNA through m6A-induced structural changes or by directly recognizing and interacting with m6A-modified sites. Their functions influence various cellular processes, maintaining RNA splicing, nuclear export, stability, and translation, thereby playing critical roles in disease development (Table 2).

Table 2.

Functions of m6A regulators in RNA metabolism

| Type | m6A regulators | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | METTL3 | Catalyzes m6A modification | [112] |

| METTL14 | A core subunit of the m6A methyltransferase forms a heterodimer with METTL3 to facilitate m6A modification | [112] | |

| WTAP | The regulatory subunit of the m6A methyltransferase and recruits METTL3 and METTL14 into the nuclear speckles | [113] | |

| METTL16 | Accountable for m6A modification of U6 snRNA, snRNA and other lncRNAs | [104] | |

| METTL5 | Accountable for m6A modification of 18 S rRNA | [105] | |

| ZCCHC4 | Accountable for m6A modification of 28 S rRNA | [106] | |

| RBM15 | Binds the m6A complex and recruits it to a special RNA site | [114] | |

| VIRMA/KIAA1429 | Directs the methyltransferase components to specific RNA region | [115] | |

| Erasers | FTO | Demethylates m6A, also has activity towards m6Am and m1A | [116, 117] |

| ALKBH5 | Principally demethylates m6A | [118] | |

| ALKBH1 | Acting as a tRNA demethylase by removing N(1)-methyladenine, which regulates translation initiation and elongation | [109] | |

| ALKBH3 | tRNAs demethylase | [111] | |

| Readers | YTHDF1 | Enhances mRNA translation | [119] |

| YTHDF2 | Enhances mRNA degradation | [119] | |

| YTHDF3 | Prompts translation and degradation by interacting with YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 | [120] | |

| YTHDC1 | Leads to RNA splicing and export | [121] | |

| YTHDC2 | Improves the translation efficiency of target mRNA | [121] | |

| IGF2BP1/2/3 | Enhances the stability and translation of mRNA | [122] | |

| HNRNPA2B1 | Spurs primary microRNA processing | [123] | |

| eIF3 | Promotes mRNA translation | [124] | |

| ELAVL1 | RNA-binding protein | [125] | |

| Prrc2a | Recognizes m6A modification and associates with myelin formation and meiosis | [126, 127] |

Cross talk between m6A modification and other posttranscriptional modifications

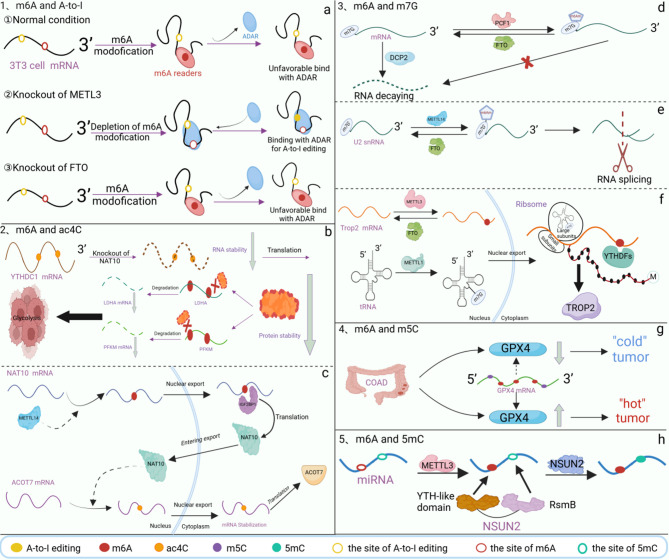

Post-transcriptional modification represents an essential regulatory mechanism in gene expression, involving a complex interplay of various processes. The interaction between m6A modification and other RNA modifications in both physiological and pathological contexts has been increasingly recognized; however, research in this field remains in its early stages. As early as 2018, genome-wide analyses revealed that m6A modification negatively regulates adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing. Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) catalyze the conversion of adenosine to inosine in double-stranded RNA substrates. In mouse 3T3 cells, knockdown of METTL3 contributed to an enhanced A-to-I editing, whereas depletion of FTO resulted in its downregulation. Despite these observations, the precise mechanism by which m6A influences A-to-I editing within the same transcript remains unclear. It is hypothesized that m6A-modified RNAs may exhibit reduced binding affinity for ADAR, or alternatively, that the presence of m6A-bound reader proteins may sterically hinder subsequent A-to-I editing [128]. N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) is the only enzyme identified to catalyze N4-acetylcytosine (ac4C) modification [129]. In osteosarcoma, NAT10 knockdown impairs the translation of the m6A reader YTHDC1. Through disrupting this pathway, NAT10 depletion reduces osteosarcoma cell growth, migration, and invasion while increasing global m6A levels [130]. Beyond acetylation and A-to-I editing, m6A also exhibits crosstalk with various methylation modifications. Under normal physiological conditions, decapping enzyme 2 (DCP2) regulates mRNA degradation when the 5’ cap is modified by m7G [131]. If the first nucleotide following the m7G cap is 2’-O-dimethyladenosine (Am), this Am residue can be further methylated by phosphorylated CTD-interacting factor 1 (PCIF1), forming the m6Am modification. FTO is capable of removing this m6Am mark, thereby maintaining its dynamic reversibility. Notably, the presence of an m7G cap adjacent to m6Am protects the transcript from DCP2-mediated decapping, underscoring the functional coordination between these modifications [132]. m6Am modification has also been detected within the interior regions of U2 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) alongside m7G-modified caps. The cooperative action of m6Am and m7G modifications has an essential impact on regulating RNA splicing [133]. In bladder cancer (BCa), trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2) is highly upregulated. METTL3-mediated m6A modification at the 3’UTR of TROP2 mRNA enhances its translation, while METTL1-mediated m7G modification in tRNA improves translation efficiency. These modifications act synergistically to increase TROP2 expression, thereby promoting BCa progression [134]. Interestingly, IGF2BP family proteins recognize both m6A and m7G modifications within mRNAs in cancer cells. Notably, the spatial distribution of m6A and m7G is similar when bound by IGF2BP, but their regulatory effects on mRNA stability differ. IGF2BP-mediated recognition of m7G promotes mRNA degradation, whereas recognition of m6A enhances mRNA stability. This suggests a potential functional interplay between these modifications, as more than half of m7G-modified mRNAs were found to be simultaneously modified by m6A [135]. 5mC methylation is a well-characterized epigenetic modification in mammalian DNA. Remarkably, single-molecule quantum sequencing of miR-200c-5p—a microRNA derived from colorectal cancer (DLD-1) cells—revealed simultaneous m6A and 5mC modifications. Further studies demonstrated that RNA 5mC methylation is catalyzed by NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 2 (NSUN2), an enzyme possessing two distinct structural domains: a YTH-like domain responsible for recognizing m6A, and an RsmB domain that catalyzes cytosine methylation. As a result, m6A modifications at positions #7 and #11 in miR-200c-5p are consistently associated with 5mC modification at position #13, highlighting the coordinated regulatory interplay between these two modifications [136] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The crosstalk between m6A modification and other posttranscriptional modifications. (a) There is a negative regulatory effect of m6A modification on A-to-I editing. Knockdown of METTL3 in mouse 3T3 cells upregulates A-to-I while knockdown of FTO downregulates A-to-I. (b) Knockout of NAT10, a major enzyme for ac4C acetylation, reduces the stability of YTHDC1, rendering the m6A sites on PFKM and LDHA mRNA unrecognized and ultimately positively regulating glycolysis in osteosarcoma cells. (c) METTL14 facilitates the m6A modification of NAT10 mRNA, while IGF2BP1 interacts with the m6A site on NAT10 mRNA to enhance its translation, resulting in NAT10 production. NAT10 mediates the ac4C modification of ACOT7 mRNA, promoting its translation to form ACOT7. (d) Catalyzes m6Am modification near the m7G cap, which increases resistance to DCP2-mediated decapping. (e) METTL14 installs m6Am modification at an internal site in U2 snRNA, which culminates in influencing global alternative RNA splicing. (f) METTL3 regulates m6A modification at the 3’-UTR in TROP2 mRNA to enhance translation of TROP2 mRNA, and METTL1 mediates m7G modification in tRNA to improve mRNA translation efficiency, which synergistically increase TROP2 expression to promote bladder cancer cell development. (g) Both m6A and m5C modifications are present in GPX4 mRNA, and both modifications work together to maintain redox homeostasis in COAD. (h) METTL3 mediates m6A modification of miRNAs, and NSUN2 recognizes m6A through the YTH-like structure domain and mediates 5mC methylation modification through the RsmB structural domain

The relationship between enhancer and m6A modification

Disruptions in epigenetic regulation play a pivotal role in numerous physiological and pathological conditions, with particularly profound implications for cancer development. Two key components in the field of epigenetics are m6A RNA methylation and enhancers. m6A is widely recognised as a post-transcriptional modification, while enhancers primarily regulate gene transcription. However, the relationship between m6A and enhancers remains unclear. Some potential effects of m6A on enhancers have been documented. In the context of acute myeloid leukaemia, the establishment of active enhancer elements potently induces IGF2BP2 and IGF2BP3 expression. These RNA-binding proteins, in turn, stabilise m6A-modified DDX21 transcripts. Functionally, DDX21 orchestrates an oncogenic programme by recruiting TF YBX1 to activate ULK1 expression, ultimately promoting leukemogenesis through enhanced proliferation and apoptosis resistance [137]. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), the m6A eraser enzyme FTO regulates bromodomain-containing protein 9 (BRD9) expression by demethylating its mRNA to enhance stability. Importantly, the TF SOX17 mediates BRD9 recruitment to de novo enhancers that control key oncogenic networks, facilitating ccRCC progression [138]. Notably, we identified a METTL14-m6A-BPTF regulatory axis in renal cell carcinoma metastasis. While m6A modification destabilised BPTF mRNA, BPTF expression remained crucial for promoting lung metastasis. METTL14 deficiency led to BPTF accumulation, which subsequently altered the enhancer repertoire to reinforce oncogenic pathways and form active enhancers that reprogrammed cellular metabolism towards glycolysis. This work uncovers previously unrecognised functional links between RNA epigenetics and chromatin remodelling in cancer progression [139]. In conclusion, these results provide greater insight into the connection between enhancers and m6A. Nevertheless, only a limited number of studies have verified that m6A plays a role in enhancer regulation. It is still uncertain whether enhancers influence m6A in a mechanistic way, and further research is required to shed light on this issue.

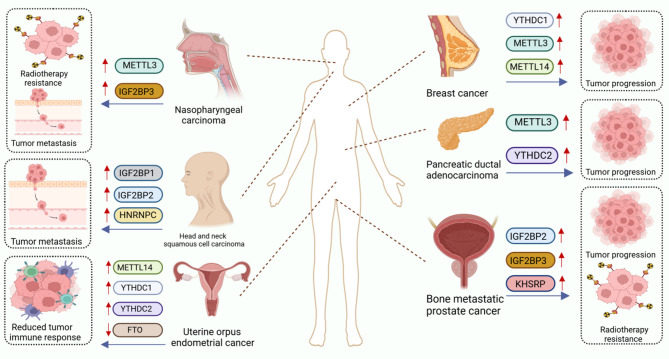

RNA m6A modification in cancer

Numerous studies have demonstrated that m6A modification and its regulatory proteins exert significant influence over cancer initiation, progression, and prognosis. This section summarises the key roles of m6A modifications across various cancers (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The roles of m6A regulators in cancer

| Cancer types | m6A regulators | Expression | Targets | Function | Role in cancer | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML | IGF2BP2 | Upregulation | MYC/GPT2/SLC1A5 |

Prompting cell growth and proliferation Hindering cell differentiation and apoptosis |

Oncogene | [144] |

| Glioblastoma | ALKBH5 | Upregulation | VEGFA/CHK1/CD73 | Prompting cell migration, invasion, and resistance to radiotherapy | Oncogene | [146–148] |

| SRSF7 | Upregulation | PBK | Enhancing cell proliferation and migration | Oncogene | [149] | |

| LC | METTL3 | Upregulation | circIGF2BP3/DCP2 | Prompting cell immune escape and resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [151, 153] |

| IGF2BP3 | Upregulation | COX6B2 | Prompting cell resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [154] | |

| FTO | Downregulation | ESR1 | Inhibiting cell growth and metastasis | Anti-oncogene | [152] | |

| YTHDF1/IGF2BP3 | Upregulation | ESR1 | Prompting cell growth and metastasis | Oncogene | [152] | |

| ESCA | METTL3 | Upregulation | MYC | Promoting cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and immune escape | Oncogene | [157, 158] |

| GC | METTL3/IGF2BP2 | Upregulation | PABPC1/miRNA-118/STAT5A | Prompting cell proliferation and migration | Oncogene | [159–161] |

| YTHDF1 | Upregulation | IFN-γ | Inhibiting cell growth and metastasis | Oncogene | [164] | |

| YTHDF2 | Upregulation | CyclinD1 | Prompting cell growth, invasion, and resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy | Oncogene | [165] | |

| YTHDF3 | Upregulation | lncRNAs/miRNAs/mRNA | Prompting cell growth and invasion | Oncogene | [166] | |

| HCC | METTL3/METTL14 | Upregulation | ACLY, SCD1 | Prompting cell growth and invasion | Oncogene | [167] |

| WTAP/IGF2BP3 | Upregulation | circCCAR1 | Prompting cell growth, metastasis, resistance to chemotherapy, and immunosuppression | Oncogene | [170] | |

| YTHDF1 | Upregulation | ATG2A | Prompting cell growth and metastasis | Oncogene | [234] | |

| PC | WTAP/IGF2BP3 | Upregulation | GBE1 | Promoting cell proliferation and stemness | Oncogene | [175] |

| CRC | YTHDF2 | Downregulation | STEAP3-AS1 |

Inhibiting cell growth, proliferation and metastasis |

Anti-oncogene | [178] |

| METTL3 | Upregulation | POU6F2-AS1 | Promoting cell growth and invasion | Oncogene | [179] | |

| METTL16/IGF2BP1 | Upregulation | SOGA1 | Promoting cell growth and proliferation | Oncogene | [180] | |

| METTL17 | Upregulation | LRPPRC/MSSUs | Promoting cell growth, proliferation and invasion | Oncogene | [181] | |

| ALKBH5 | Upregulation | AXIN2 | Promoting cellular immunosuppression | Oncogene | [182] | |

| RCC | HNRNPC | Upregulation | PPAP2B | Prompting cell proliferation and metastasis | Oncogene | [183] |

| METTL14 | Upregulation | TRAF1 | Prompting cell resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [184] | |

| ALKBH5 | Upregulation | AURKB | Prompting cell growth, proliferation, invasion | Oncogene | [185] | |

| BCa | RBM15/METTL3 | Upregulation | ENO1 | Promoting cell growth | Oncogene | [186] |

| WTAP | Upregulation | circ0008399 | Promoting cell resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [187] | |

| YTHDF2 | Upregulation | DHCR7 | Promoting cell invasion and metastasis | Oncogene | [188] | |

| FTO | Upregulation | MALAT1 | Promoting cell growth and proliferation | Oncogene | [189] | |

| PCa | YTHDC1 | Upregulation | SLC12A5 | Prompting cell metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [190] |

| YTHDF3 | Upregulation | SPOP/NXK3.1/TWIST1/SNAI2 | Prompting cell growth and proliferation | Oncogene | [191] | |

| METTL3 | Upregulation | circRBM33 | Prompting cell growth, invasion, and resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [192] | |

| RBM15 | Upregulation | FTO-IT1 | Prompting cell growth and proliferation | Oncogene | [193] | |

| FTO | Downregulation | DDIT4 | Inhibiting cell growth and invasion | Anti-oncogene | [194] | |

| BC | METTL3/YTHDF2 | Upregulation | LATS1 | Prompting cell growth and invasion | Oncogene | [195] |

| ALKBH5 | Upregulation | FOXO1 | Prompting cell stemness, and resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [196] | |

| IGF2BP2 | Upregulation | CDK6 | Prompting cell growth and proliferation | Oncogene | [197] | |

| hnRNPA2B1 | Upregulation | ALYREF/NXF1 | Prompting cell stemness and proliferation | Oncogene | [198] | |

| OC | METTL3 | Upregulation | circPLPP4 | Prompting cell resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [199] |

| ALKBH5 | Upregulation | ITGB1/FSH | Prompting cell proliferation and metastasis | Oncogene | [200, 201] | |

| YTHDC1 | Downregulation | PIK3R1 | Prompting cell growth and proliferation | Anti-oncogene | [202] | |

| CC | ALKBH5 | Downregulation | circCCDC134 | Prompting cell proliferation and metastasis | Anti-oncogene | [203] |

| HNRNPC | Upregulation | FOXM1 | Prompting cell invasion and metastasis | Oncogene | [204] | |

| METTL3 | Upregulation | HSPA9 | Prompting malignant transformation of cells | Oncogene | [205] | |

| EC | WTAP | Downregulation | EGR1 | Hindering cell growth, and resistance to chemotherapy | Anti-oncogene | [207] |

| METTL3 | Downregulation | NLRC5 | Hindering cell proliferation and metastasis | Anti-oncogene | [208] | |

| OSCC | METTL14 | Upregulation | CALD1 | Promoting cell growth and metastasis | Oncogene | [209] |

| osteosarcoma | METTL14 | Upregulation | MN1 | Prompting cell growth and resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [210] |

| melanoma | METTL14 | Upregulation | RUNX2 | Prompting cell growth and metastasis | Oncogene | [211] |

| pitNET | FTO | Upregulation | DSP | Prompting cell growth and resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [212] |

| NPC | WTAP | Upregulation | DIAPH1-AS1 | Prompting cell growth and metastasis | Oncogene | [213] |

| Laryngeal cancer | METTL3 | Upregulation | HOXA10-AS | Prompting cell proliferation and oxidative resistance | Oncogene | [216] |

| HSCC | METTL3 | Upregulation | circCUX1 | Prompting cell resistance to radiotherapy | Oncogene | [217] |

| seminoma | METTL3 | Upregulation | TFAP2C | Prompting cell resistance to chemotherapy | Oncogene | [218] |

AML acute myeloid leukemia, LC lung cancer, ESCA esophageal cancer, GC gastric cancer, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, PC pancreatic cancer, CRC colorectal cancer, RCC renal cell carcinoma, BCa bladder cancer, PCa prostate cancer, BC breast cancer, OC ovarian cancer, CC cervical cancer, EC endometrial cancer, OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, NPC nasopharyngeal carcinoma, pitNET pituitary neuroendocrine tumors, HSCC hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

Acute myeloid leukemia

AML, the most prevalent form of adult acute leukaemia, is an aggressive haematological malignancy characterised by the clonal expansion of immature myeloid cells, impaired differentiation of myeloid progenitors, and infiltration of malignant clones into the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and other tissues. These pathological processes lead to uncontrolled proliferation, blocked differentiation, and disrupted haematopoiesis. The development of AML has been linked to dysregulation of m6A regulators including METTL3, METTL14, ALKBH5, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and IGF2BP2 [140–144]. Among these, IGF2BP2 expression is significantly elevated in AML, particularly in leukaemia stem cells (LSCs) and leukaemia-initiating cells (LICs), and is strongly associated with poor prognosis. IGF2BP2 enhances the expression of MYC, GPT2, and SLC1A5 in an m6A-dependent manner, promoting glutamine uptake and metabolism. This leads to improved mRNA stability and enhanced translation, fuelling the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and accelerating AML cell proliferation. These findings suggest that IGF2BP2 inhibitors may hold therapeutic promise in future AML treatment [144].

Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma is the most common and lethal primary brain tumour, known for its invasive growth, extensive vascularisation, and neurodestructive behaviour. Expression levels of YTHDF family members and METTL14 are elevated in glioblastoma tissues compared to normal brain tissue. In particular, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3 are markedly upregulated in high-grade gliomas [145]. ALKBH5 is also highly expressed in gliomas, and its knockdown has been shown to reduce angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo [146]. Previous research has linked ALKBH5 with glioma cell invasion, as well as radioresistance and chemoresistance [147, 148]. Furthermore, ALKBH5 expression correlates with glioma malignancy and patient prognosis, positioning it as a potential clinical biomarker [146]. Additionally, SRSF7 (Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 7), a novel m6A regulator, has been found to promote glioma cell proliferation and migration. It does so by recruiting the methyltransferase complex to selectively enhance m6A methylation near its RNA binding sites, which are often located in genes associated with cell growth and motility [149]. These findings provide important insights into the development of glioma-targeted therapies.

Lung cancer

Lung cancer (LC) is one of the most aggressive malignancies worldwide and accounts for approximately 18% of all cancer-related deaths. Compared to adjacent normal tissues, expression of METTL3, METTL16, YTHDF1, and IGF2BP3 is elevated in LC [150–152], while FTO expression is typically reduced [152]. A circular RNA derived from IGF2BP3, known as circIGF2BP3, is significantly overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This circRNA (circular RNA) is generated via back-splicing of exons 4 and 13 and undergoes m6A modification mediated by METTL3, with YTHDC1 facilitating its circularisation. CircIGF2BP3 impairs CD8⁺ T cell responses and promotes tumour immune evasion [153]. In addition, METTL3 enhances m6A methylation of DCP2, leading to its degradation and the promotion of mitochondrial autophagy, which in turn contributes to chemoresistance in NSCLC [151]. Recent findings indicate that IGF2BP3 also promotes metabolic reprogramming, thereby contributing to acquired drug resistance [154]. FTO expression is significantly lower in NSCLC tumour tissues compared to adjacent non-cancerous tissues. One of FTO’s targets is ESR1 (oestrogen receptor alpha). YTHDF1 and IGF2BP3 each recognise distinct m6A sites on ESR1 mRNA, enhancing its stability and promoting tumour growth. Overexpression of FTO leads to reduced m6A methylation of ESR1 mRNA. These insights into the FTO–YTHDF1–IGF2BP3–ESR1 axis present new opportunities for NSCLC treatment [152]. However, studies on ALKBH5 in NSCLC have yielded conflicting results. Some research suggests ALKBH5 overexpression promotes NSCLC progression, while other studies indicate that elevated ALKBH5 levels inhibit tumour cell proliferation and promote apoptosis [155, 156]. These discrepancies highlight the need for further investigation into the context-dependent role of ALKBH5 in LC.

Esophageal cancer

Oesophageal cancer (ESCA) is a common and highly fatal malignancy of the digestive tract. Recent studies have revealed a positive correlation between Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) infection and METTL3 expression in ESCA tissues, with Fn significantly upregulating METTL3. c-Myc mRNA has been identified as a downstream target of METTL3, and the m6A reader YTHDF1 binds to the m6A site on c-Myc mRNA, enhancing its stability and thereby increasing c-Myc expression, which promotes ESCA cell invasion and metastasis [157]. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2), a key mitochondrial enzyme involved in one-carbon unit metabolism, is significantly elevated in ESCA tissues and associated with poor prognosis. METTL3, ALKBH5, and FTO mediate the m6A modification of c-Myc mRNA, and SHMT2 further regulates this modification via the one-carbon metabolic pathway by increasing intracellular SAM (S-adenosylmethionine) levels, ultimately promoting c-Myc expression and facilitating immune escape [158]. Thus, targeting the one-carbon unit metabolic pathway may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for ESCA.

Gastric cancer

GC is the fifth most prevalent malignancy worldwide. Both METTL3 and its downstream target STAT5A act as oncogenes in GC. Helicobacter pylori infection has been shown to further elevate the expression of METTL3 and STAT5A, which correlates with poor patient prognosis. The reader protein IGF2BP2 binds to the m6A-modified site on STAT5A mRNA, enhancing its stability and protein expression, thereby increasing the invasive potential of GC cells [159]. In addition, METTL3 can promote gastric carcinogenesis by facilitating EMT and by binding to non-m6A-modified mRNAs [160, 161]. Although ALKBH5 has been explored for its role in GC cell invasion and progression [162], its expression is significantly lower in GC tissues compared to normal tissues and is further reduced in patients with distant metastases [163]. This inconsistency has led to debate regarding the role of ALKBH5 in GC, necessitating further research. Moreover, engineered small extracellular vesicles have been developed to deliver siRNA targeting YTHDF1, effectively reducing its expression and thereby inhibiting GC progression and metastasis, offering a novel therapeutic avenue [164]. YTHDF2 has also been shown to promote GC cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, as well as to increase resistance to radiotherapy [165]. Similarly, YTHDF3 enhances GC cell invasiveness by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway and modulating the immune microenvironment. Its upregulation is often associated with poor clinical outcomes [166].

Hepatocellular carcinoma

HCC is the second leading cause of cancer-related death globally. In HCC cells, overexpression of METTL3 and METTL14 leads to m6A-mediated stabilisation of oncogenic transcripts, thereby accelerating tumour progression [167]. CircRNAs also play critical roles in HCC. For example, circGPR137B is significantly downregulated in HCC and forms a feedback loop with miR-4739 and FTO, collectively suppressing metastasis [168]. Paradoxically, FTO is upregulated in HCC and contributes to tumour proliferation. Targeting FTO with inhibitors has shown potential to suppress HCC growth and enhance chemosensitivity [169]. Additionally, EIF4A3 promotes the generation of circCCAR1, whose stability is enhanced by WTAP-mediated m6A modification via IGF2BP3 interaction. Elevated levels of circCCAR1 impair CD8⁺ T-cell function, facilitating HCC progression and metastasis [170]. Multi-omics analyses have also revealed that NOTCH1 is a direct downstream target of YTHDF1, which binds to the m6A-modified NOTCH1 mRNA, enhancing its stability and translation. Inhibiting YTHDF1 reduces cancer cell stemness and improves therapeutic responses, making it a promising target for HCC treatment [171].

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the most lethal gastrointestinal malignancy, known for its insidious onset, rapid progression, and dismal prognosis. METTL3 has been found to promote PC cell proliferation, whereas METTL16 inhibits PC cell metastasis and FTO reduces drug resistance [172–174]. The m6A modification of GBE1 (Glucan branching enzyme 1) mRNA by WTAP and IGF2BP3 enhances its stability and expression, correlating with poor prognosis in PC [175]. Additionally, DDIT4-AS1, a downstream target of ALKBH5, is upregulated via ALKBH5-mediated m6A demethylation, increasing stemness and chemoresistance [176]. Under hypoxic conditions, ALKBH5 decreases global m6A levels in PC cells, thereby enhancing glycolysis. YTHDF2 recognises m6A-modified HDAC4 (histone deacetylase type 4) mRNA, stabilising its expression. HDAC4, in turn, regulates the acetylation of HIF1α, a direct target of ALKBH5. This establishes a positive feedback loop involving ALKBH5/HDAC4/HIF1α, which drives glycolytic metabolism and promotes PC cell migration under hypoxia [177]. This regulatory axis may offer a therapeutic opportunity for hypoxia-targeted PC treatment.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies globally, ranking third in incidence and second in mortality. The relationship between m6A modification and CRC progression has been well established. The antisense lncRNA STEAP3-AS1, induced by hypoxia, promotes CRC cell growth and migration, correlating with poor prognosis. STEAP3-AS1 and YTHDF2 compete for binding, disrupting the interaction between YTHDF2 and STEAP3 mRNA. This competition protects STEAP3 mRNA from m6A-mediated degradation, thereby enhancing the expression of STEAP3 protein to support CRC progression [178]. Another long non-coding RNA, POU6F2-AS1, is also upregulated in CRC. METTL3-induced m6A modification of POU6F2-AS1 promotes CRC cell proliferation and adipogenesis [179]. METTL16 expression correlates with the inhibition of SOGA1 (suppressor of glucose by autophagy) and PDK4 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4). METTL16 enhances SOGA1 expression by binding to IGF2BP1, leading to the upregulation of PDK4, which subsequently promotes glycolytic reprogramming and accelerates CRC progression [180]. METTL17 expression is elevated in CRC patients, and its depletion increases sensitivity to ferroptosis while inhibiting CRC cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumour growth in xenograft models [181]. ALKBH5 interacts with and demethylates AXIN2, a Wnt repressor, leading to the degradation of IGF2BP1 and promoting immunosuppression, thus fostering CRC development. Targeting ALKBH5 may provide therapeutic benefits for CRC patients [182].

Renal cell carcinoma

Among urologic malignancies, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has a comparatively high mortality rate, and its incidence continues to rise. Many studies have linked m6A regulators to the development of RCC. However, it has now been discovered that METTL3, the IGF2BP family, and FTO all appear to play conflicting roles in RCC, with even the function of the same m6A regulator differing depending on the RCC subtype. CircPPAP2B was found to be overexpressed in highly aggressive RCC cells and associated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that circPPAP2B interacts with HNRNPC in an m6A-dependent manner and promotes HNRNPC nuclear translocation. On-degradable ubiquitination of HNRNPC leads to subcellular re-localisation, which causes metastasis of RCC [183]. Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor TRAF1 expression is up-regulated in sunitinib-resistant RCC cells. METTL14 regulates the mRNA stability of TRAF1 in an IGF2BP2-dependent manner to maintain sunitinib resistance [184]. ALKBH5, which is highly expressed in RCC, stabilises the AURKB mRNA (encoding aurora kinase B) in an m6A-dependent manner to promote RCC cell growth and invasion [185]. Therefore, targeting METTL14 and ALKBH5 signalling pathways could offer a promising therapeutic avenue for RCC.

Bladder cancer

BCa is the second most common genitourinary carcinoma. Recurrence, metastasis, and drug resistance are three key concerns of BCa that need to be addressed. METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP are elevated in BCa compared to adjacent normal tissues. The RBM15/METTL3 complex mediates the m6A modification of ENO1 mRNA, and the oncogene ENO1 stimulates the growth of BCa cells. YTHDF1 recognises this m6A modification and accelerates the effectiveness of ENO1 protein translation, thus promoting the progression of BCa [186]. Binding of WTAP to circ0008399 speeds up the establishment of the m6A methyltransferase complex, improving circ0008399’s mRNA stability and triggering the expression of TNFα-inducible protein 3 (TNFAIP3). TNFAIP3 overexpression decreases BCa’s chemosensitivity [187]. BCa invasion in vitro and metastasis in vivo were facilitated by the upregulation of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) in BCa tissues. Decreased mRNA degradation due to YTHDF2-mediated increased DHCR7 in BCa induced the cAMP/protein kinase A/FAK pathway, greatly enhancing the invasive and metastatic capability of BCa, leading to poor prognosis [188]. Notably, the m6A eraser FTO functions as an oncogenic factor in BCa, as well as m6A writers. It has been shown that FTO catalyses the demethylation of metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1), regulates microRNA miR-384 and MAL T-cell differentiation protein 2 (MAL2) expression, and ultimately promotes the progression of BCa [189]. Thus, whether some crosstalks between m6A erasers and writers occur in BCa, causing co-carcinogenesis, remains unclear.

Prostate cancer

PCa is the second most prevalent malignant tumour, which can become more challenging to treat after a few years if it develops into CRPC. The dysregulation of m6A modification is strongly linked to PCa progression. SLC12A5, a neuron-specific potassium chloride co-transporter, can form a complex with YTHDC1 and then upregulate the TF HOXB13 to promote PCa progression [190]. In CRPC, YTHDF3 expression is upregulated and is associated with poor survival and high-grade metastasis. YTHDF3 promotes the RNA degradation of SPOP and NXK3.1 but stabilises the RNA expression of m6A-dependent TWIST1 and SNAI2, ultimately promoting the proliferation of CRPC cells [191]. The m6A-modified circRBM33 could bind to FMR1 and form a binary complex. The knockdown of METTL3 disrupted the formation of the complex. The circRBM33 in the complex can stimulate PCa cells’ mitochondrial respiration, while FMR1 can regulate cellular respiration. When these two work together, they can accelerate the proliferation of PCa cells and promote invasion [192]. FTO-IT1 is a lncRNA that is negatively associated with patient survival and is elevated in anti-androgenic and chemotherapy-resistant PCa. FTO-IT1 can directly interact with RMB15 to hinder the m6A methyltransferase complex, which subsequently decreases the mRNA m6A levels and stability of a subset of p53 target genes, ultimately resulting in increased cancer cell growth [193]. Besides, FTO can regulate the EMT in PCa cells, which is linked to bone metastasis [194].

Breast cancer

BC is the most prevalent carcinoma and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women. m6A regulators are essential in the development and treatment of BC. LAST1 is identified as an oncogene, with its m6A modification mediated by METTL3. YTHDF2 recognises the m6A modification in LAST1 mRNA, resulting in reduced stability. By increasing LATS1 mRNA expression and activating YAP/TAZ in the Hippo pathway, the knockdown of METTL3 or overexpression of YTHDF2 can prevent the onset of BC [195]. ALKBH5 expression was increased in BC patients and positively correlated with poor prognosis and chemotherapy resistance. ALKBH5 promotes m6A demethylation of FOXO1 mRNA and enhances the stability of FOXO1 mRNA in DOX-resistant BC cells, increasing the resistance of BC cells to chemotherapy [196]. Cell cycle protein-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) is a direct target of IGF2BP2 in BC cells. IGF2BP2 directly regulates CDK6 in an m6A-dependent manner to accelerate BC progression [197]. Knockdown of HnRNPA2B1 or inhibition of m6A-tagged mRNA export can cause maintenance of nuclear m6A-tagged mRNAs linked to stemness maintenance. This would inhibit BC cell self-renewal and effectively improve the efficacy of DOX treatment [198]. Consequently, inhibition of m6A-tagged mRNA and its nuclear export may be a prospective therapeutic approach.

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer (OC) is one of the three most common gynaecologic malignancies, and patients often have poor prognosis due to the lack of effective screening strategies. m6A modification has an impact on OC’s development, migration, invasion, and drug resistance. m6A can modify circPLPP4 and increase RNA stability, resulting in elevated circPLPP4 in OC cells. CircPLPP4 can act as a microRNA sponge to sequester miR-136, which further competitively up-regulates the expression of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 (PIK3R1), leading to an increase in drug resistance in OC cells. Targeting m6A-modified circPLPP4 may be a prospective therapeutic target for OC-resistant patients [199]. Integrin subunit β1 (ITGB1) is a downstream target of ALKBH5 regulation. High expression of ALKBH5 demethylates m6A modifications in ITGB1 mRNA, which in turn prevents YTHDF2 from mediating the m6A-dependent degradation of this mRNA. This results in increased ITGB1 expression and enhanced phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src proto-oncogene, ultimately promoting lymph node metastasis of OC [200]. Moreover, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) was also able to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition in OC cells, leading to OC metastasis in an m6A-dependent manner [201]. YTHDC1 is an oncogene in OC progression, and overexpression of YTHDC1 hindered OC advancement both in vivo and in vitro, but YTHDC1 expression was down-regulated in OC patients [202]. More investigation is required to explore whether YTHDC1 could be a novel therapeutic avenue for OC.

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common gynaecological tumour worldwide and is primarily induced by persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV). Drug resistance, metastasis, and CC cell proliferation are all closely related to m6A modifications. It has been found that, except for ALKBH5, whose expression is down-regulated in CC and exerts an anti-tumour effect, all other m6A modifiers are up-regulated in expression and exert an oncogenic effect. CircCCDC134, a cyclic RNA with m6A modification, stimulates CC cell growth and invasion both in vivo and in vitro. ALKBH5 has the capacity to mediate the demethylation of circCCDC134 to decrease its stability, while YTHDF2 recognises the m6A on circCCDC134 in an m6A-dependent manner and improves its stability. As ALKBH5 expression was reduced in CC and YTHDF2 was increased in CC, they synergistically enhanced circCCDC134 levels and accelerated CC progression [203]. HNRNPC significantly decreased the patients’ overall survival by recognising the m6A site on FOXM1 RNA (oncogene) in an m6A-dependent manner and controlling the isoform conversion of FOXM1 to encourage lymph node metastasis in CC [204]. Expression of the CC-derived exosome Mortalin was increased in plasma exosomes isolated from CC patients. m6A methylation in the 3’UTR of METTL3-catalysed HSPA9 mRNA conferred higher mRNA stability and enhanced translational efficiency to Mortalin [205]. Overexpression of Mortalin, in turn, facilitated proliferation, migration, and invasion of CC cells.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer (EC) is a highly prevalent gynaecologic carcinoma with increasing morbidity and mortality worldwide. m6A modifications can interact with circRNAs to influence the growth, invasion, and migration of EC cells. CircCHD7 connects with IGF2BP2 in an m6A-dependent manner by increasing mRNA stability and increases the expression of the downstream target gene, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRB), which ultimately enhances EC cell proliferation and hampers apoptosis [206]. Reduced levels of m6A modification and WTAP in EC patients correlate with the stemness of endometrial cancer stem cells (ECSC). The discovery of the WTAP/EGR1/PTEN axis offers a novel therapeutic strategy for EC [207]. Low METTL3 levels were related to poor prognosis in EC patients, while METTL3 expression was positively correlated with CD8 levels. Increased METTL3 in patients raises the ratio of CD8 + T cells and impedes EC progression, whereas METTL3 depletion has the opposite effect. The NLR family CARD structural domain containing 5 (NLRC5) is a target for METTL3-mediated m6A modification, which prevents its degradation through a YTHDF2-dependent mechanism. Elevated METTL3 levels enhance immunosurveillance and reduce EC immune evasion, suggesting that METTL3 and YTHDF2 could serve as diagnostic and prognostic factors for EC [208].

Other cancers