Abstract

Objective

The present study aimed to evaluated the expression profiles of the Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-synthesizing enzymes cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) expression and attempted to establish its relationship to ovarian cancer (OV) drug resistance and prognosis.

Methods

The expression levels of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) were analyzed in OV from GSE26193 and GSE14764 datasets, and OVCAR8 cisplatin resistant cell line from GSE45553 datasets. The correlation between prognosis with CBS and CSE expression levels were analyzed in OV from GSE26193 dataset. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of CBS and CSE expression, meanwhile Kaplan-Meier analyzed of corresponding prognosis in OV patients. The relative drug sensitivity of CBS and CSE genes via gene set cancer analysis. Ultimately, the correlations among OV immune cells, CBS, and CSE. The CBS and CSE expression levels, and pan-cancer prognosis using TCGA database.

Results

CBS and CSE were significantly overexpressed in the OV and OVCAR8 cisplatin resistant cell line (GSE26193: p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001; GSE14764: p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001 IHC: p<0.0001 and p<0.0001; GSE45553: p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Interestingly, CBS is closely associated with OS and PFS in GSE26193 dataset and OV patients (GSE26193: PFS, p = 0.0391; OS, p = 0.0328. OV patients: PFS, p= 0.017; OS, p=0.030). The CBS and CSE expression levels were correlated with immune cells, CD4 T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DC) and their respective infiltration scores significantly differed. Both CBS and CSE expression levels influenced pan-cancer prognosis.

Conclusion

H2S overexpression affected the OS and PFS and could also have an impact on the drug resistance of OV. Pan cancer prognosis may vary with H2S expression.

Keywords: drug resistance, hydrogen sulfide, immune cell, ovarian cancer, pan-cancer, progression

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OV) is a gynecological malignancy with a high mortality rate.1 In 2022, 324,398 women worldwide developed OV, and 206,839 died from it.2 Histologically, approximately 90% of OVs are epithelial tumors encompassing diverse subtypes with distinct molecular alterations, clinical behaviors, and treatment responses. The remaining 10% are non-epithelial variants, primarily including germ cell tumours and sex cord-stromal tumours. Notably, germ cell tumours—the most common ovarian neoplasms in women under 30 years—are predominantly diagnosed at early stages (60–70%) with unilateral localization (95% of cases) and generally exhibit favorable prognoses.3 Nevertheless, about 70% of all OV patients (predominantly epithelial subtypes) are diagnosed at advanced stages. At this phase, the five-year survival rate drops to 30–40%, with 70% developing drug resistance.4

Current clinical practice relies on CA125 and HE4 as the only approved biomarkers for epithelial OV; however, their limited sensitivity and specificity hinder early detection. To address this, multivariate index (MVI) assays and the Risk of Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA)—which integrates menopausal status with CA125 and HE4 levels—have been developed for preoperative evaluation of adnexal masses. Emerging evidence suggests miRNAs hold promise as predictive biomarkers in epithelial OV, yet standardization of sample processing and refinement of detection platforms remain critical unmet needs.5

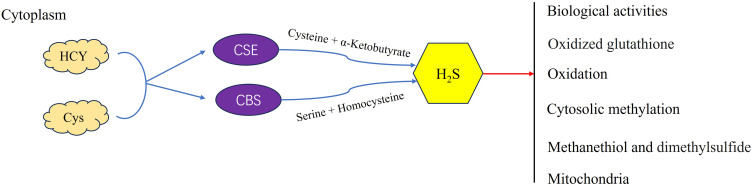

For recurrent OV patients receiving second-line or targeted therapies, median survival is limited to 9–12 months, and treatment efficacy remains below 20%.6 Resistance mechanisms often involve dysregulated DNA repair pathways. PARP inhibitors (such as Olaparib and niraparib) exploit synthetic lethality in BRCA-mutated tumors by trapping PARP–DNA complexes, thereby disrupting replication. The cytotoxicity of these agents correlates with PARP-trapping efficiency—olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib exhibit ~100-fold greater trapping capacity than veliparib.7 Additionally, the PI3K pathway, frequently hyperactivated in epithelial OV, contributes to chemoresistance by maintaining genomic stability through Aurora kinase B-mediated spindle assembly checkpoint control. PI3K inhibition destabilizes this process, inducing mitotic catastrophe via lagging chromosome accumulation during prometaphase.8 While cisplatin-sensitive recurrent cases may achieve a median survival of ~2 years, cisplatin-resistant patients face drastically reduced progression-free survival (PFS: 3–4 months) and overall survival (OS: 12 months).9 These data collectively underscore that recurrence and chemoresistance constitute the foremost barriers in OV clinical management.2,4 The mechanism of cancer drug resistance is complex and involves the host immunity, the tumor microenvironment (TME), and evasion of the tumor from host immunity.10 Even the relatively newly developed targeted anti-OV drugs have not significantly improved OS.11 Hence, it is necessary to identify the genes and/or pathways associated with the recurrence, drug resistance, and prognosis of OV.H2S, a gasotransmitter enzymatically produced by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), is now recognized as a pivotal second messenger regulating diverse physiological and pathological processes (Figure 1).12 In cancers, endogenous H2S induces angiogenesis, accelerates the cell cycle, inhibits apoptosis, and promotes tumor development.13 High exogenous H2S concentrations inhibit tumor growth by acidifying cells and regulating several signaling pathways implicated in the cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis.14,15 However, H2S also promotes progression, invasion, and metastasis in breast, bladder, kidney, liver, pancreatic, intestinal, and other cancers.16,17 Endogenous H2S may promote the proliferation and inhibit the chemotherapy-induced apoptosis of colon cancer cells.18 The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has approved > 250 sulfur-based small-molecule drugs for cancer treatment.19,20 Some of these may affect drug metabolism by releasing H2S or producing endogenous H2S in the tumor targets.21 Drugs based on H2S system (such as CSE gene therapy combined with H2S donors) have entered the stage of patent development, and the target indications include metastatic thyroid cancer and breast cancer.

Figure 1.

Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) are responsible for the enzymatic production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

In the present work, we analyzed the expression profiles of the H2S-synthesizing enzymes cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) and the pertinent clinical data for OV derived from the GSE26193, GSE14764, and GSE45553 datasets. Subsequently, the correlations among the CBS and CSE expression levels and OV prognosis were evaluated, and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses to detect their CBS and CSE expression levels in OV tissue. Finally, we assessed the relationships among the immune cells and the CBS and CSE expression levels for the OV tissues derived from TCGA database and examined the association between H2S expression and pan-cancer prognosis.

Materials and Methods

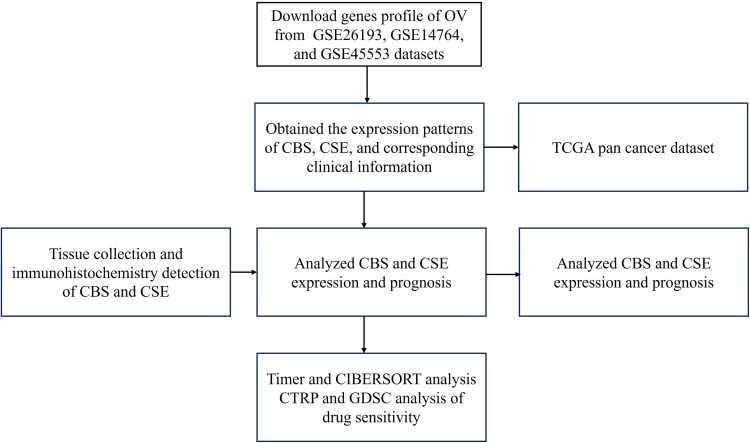

Data Collection and Workflow

The CBS and CSE expression profiles of OV and their corresponding clinical data were obtained in GSE26193 and GSE14764 datasets from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The CBS and CSE expression levels in normal tissues were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (https://commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx). The CBS and CSE expression levels in cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant OVCAR8 cells were obtained from the GSE45553 dataset in the GEO database. The CBS and CSE expression levels in pan-cancer (36 cancer types) and their corresponding OS were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga) database. The workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the present study.

Analysis of CBS and CSE Expression

CBS and CSE gene expression analyses were conducted using the GSE26193, GSE14764, and GTEx database by using the R package cluster profiler. The GSE45553 dataset included cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant OVCAR8 cells with four technical replicates per group (n=4).

Tissue Collection

Twenty-one OV and 10 normal tumor samples were collected from Zhuzhou Central Hospital (Zhuzhou, Hunan, China) between January 2018 and January 2019. All specimens were immunohistochemically evaluated and confirmed by two independent pathologists. Approval for the clinical research was granted by the Ethics Committee of Zhuzhou Central Hospital under permit No. ZZCHEC2019030-01. Each eligible participant furnished written informed consent. All procedures followed the ethical guidelines delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki and the relevant policies of the Government of the People’s Republic of China.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissue sections were dewaxed and hydrated, subjected to high-pressure antigen repair, blocked with goat serum, and incubated overnight with the primary antibodies anti-CBS (No. ab185966; 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-CSE (No. ab151769; 1:600; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). A secondary antibody (Polymer (Rabbit) IHC Kit, ready to use, biosharp, China) was added the next day and color was developed with a 3,3`-diaminobenzidine (DAB) Chromogen Kit. 1/1,000

CBS and CSE immunohistochemical analysis: observed and photographed under a high-power microscope (20x), and the color of CBS and CSE positive is brown. The Image J1.5 software measures the integrated option density (IOD) and area value of each image, and then calculates the mean density value (mean density=IOD/area), which reflects the unit area concentration of CBS and CSE protein.

Drug Sensitivity

The relative drug sensitivities of CBS and CSE were determined using Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA; http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/#/). The Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP; https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ctrp.v2.1/) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC; https://www.cancerrxgene.org) were used to establish drug sensitivities and their correlations with CBS and CSE expression in pan-cancer. A false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Correlations Among CBS and CSE Expression, Immune Infiltration, and Immune Cells

Standardized OV data samples (417) were downloaded from TCGA database in the UCSC online network (https://xenabrowser.net/). ENSG0000160200 (CBS) and ENSG00000116761(CSE) gene expression data were then extracted. Log2 (x + 0.001) transformations were performed on the gene expression values and the gene expression profiles were separately extracted for each tumor. The R software package IOBR and Timer method22 were utilized to evaluate the B cell, CD4 T cell, CD8 T cell, neutral, macrophage, and DC infiltration scores of each patient based on the CBS and CSE expression. The CIBERSORT23 package in R software was used to analyzed the 22 immune cell types were calculated for each sample based on CBS and CSE expression in the TCGA-OV dataset.

CBS and CSE Expression and Pan-Cancer Prognosis

Level three RNA sequencing expression profiles and the corresponding clinical data for CBS and CSE were downloaded from TCGA database. Univariate Cox regression analysis and random forest were run in the “forestplot” package of R to determine the P-values, hazard ratios (HR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each variable. All analytical methods were implemented in R v. 4.0.3. Two-group data were subjected to Wilcoxon’s test unless otherwise specified.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (v4.0.3, foundation for statistical computing, 2020) and its related packages unless stated otherwise. Graphs were constructed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.3.1). The Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical significant differences between two groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

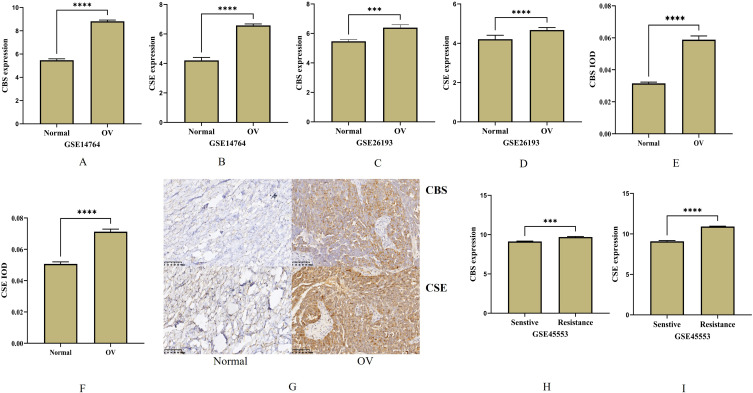

CBS and CSE are Overexpressed in OV

The expression levels of the H2S-generating proteins CBS and CSE were significantly overexpressed in OV from GSE26193 and GSE14764 dataset (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively; Figure 3A–D). We also subjected 21 OV and 10 normal ovary tissue samples to IHC analysis and found the CBS and CSE were significantly upregulated in them all (p < 0.01, Figure 3E–G). We then measured CBS and CSE expression in cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant OVCAR8 in the GSE45553 dataset of the GEO database. The CBS and CSE expression levels were relatively low in the cisplatin-sensitive OVCAR8 cell line (all p<0.0001, respectively; Figures 3H and I).

Figure 3.

The expression and Immunohistochemistry in ovarian cancer. (A–D) The expression of CBS and CSE in GSE14764 and GSE26193 datasets. (E–G) Immunohistochemical detection of CBS and CSE in normal and ovarian cancer tissue ((brown represents CD1a). (H and I) The CBS and CSE expression levels were relatively low in the cisplatin-sensitive OVCAR8 cell line from GSE45553 dataset. (***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

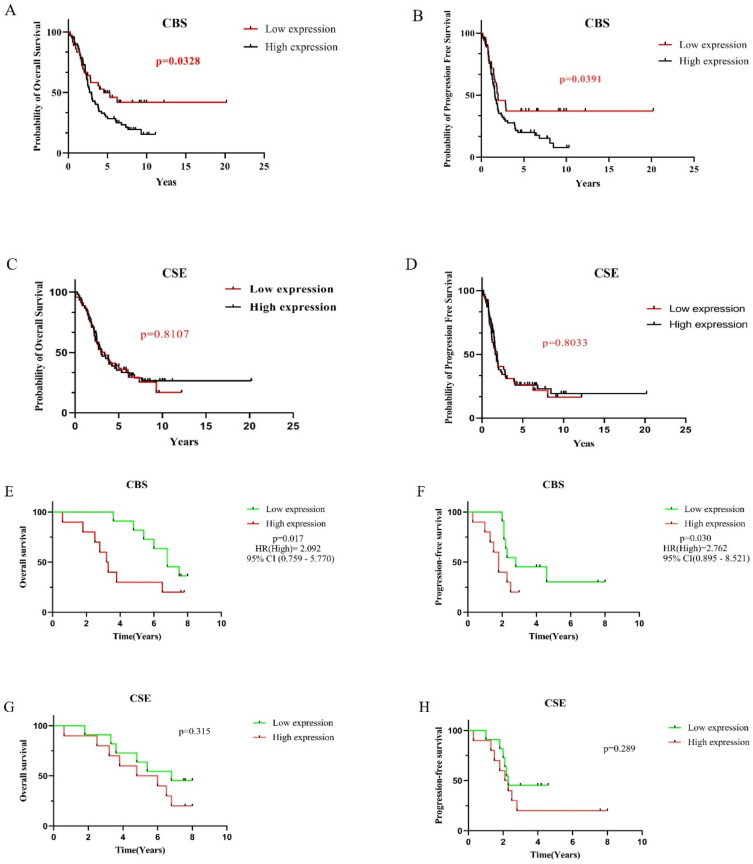

CBS and CSE Expression Affected the Prognosis of OV

The PFS and OV were significantly longer when CBS was downregulated than when it was upregulated based on the GSE26193 dataset (p = 0.0391 and p = 0.0328, respectively; Figure 4A and B, Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, the lengths of PFS and OS did not significantly differ whether CSE was downregulated or upregulated CSE (p = 0.8033 and p = 0.8107, respectively; Figure 4C and D). Subsequently, the OS and PFS of 21 patients were analyzed (Supplementary Table 2). Low expression of CBS can significantly prolong OS and PFS compared to high expression of CBS (p=0.030, HR(High)=2.762, 95% CI (0.895–8.521) and p=0.017, HR(High)=2.092, 95% CI (0.759–5.770), Figure 4E and F). However, the expression of CSE showed no difference compared to OS and PFS (p=0.289 and p=0.315, Figure 4G and H).

Figure 4.

The expression of CBS and CSE affects the prognosis of ovarian cancer. (A–H) The expression of CBS affects the OS and PFS, while there is no difference in CSE in OV from GSE26193 dataset and ovarian cancer patients.

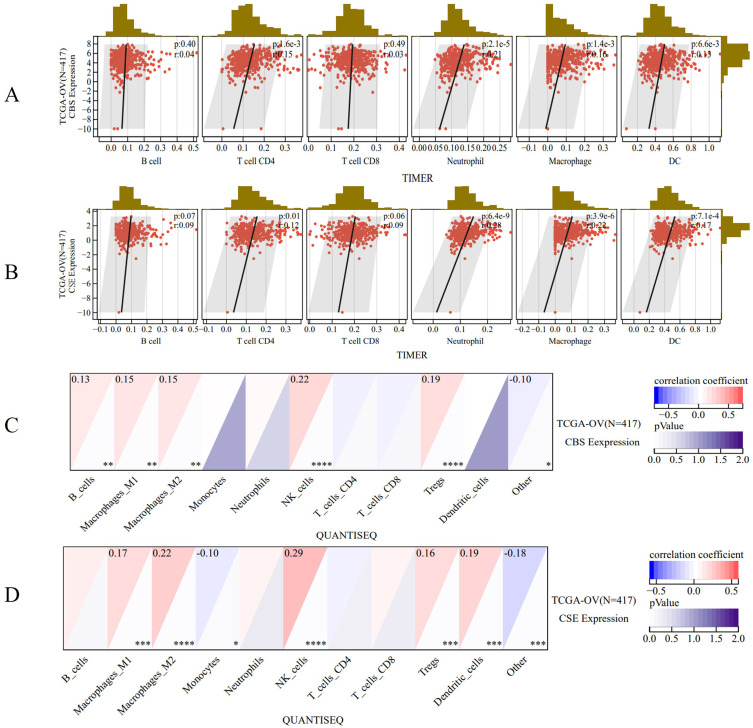

CBS and CSE are Closely Related to the Immune Cells in OV

The Timer method (Figure 5A and B) analyzed infiltration that CBS and CSE expression levels were significantly correlated with CD4 T cells (p = 1.6e-3 and p = 7.6e-3, respectively), neutrophils (p = 2.1e-5 and p = 1.4e-7, respectively), macrophages (p = 1.4e-3 and p = 2.8e-4, respectively), and dendritic cells (DC; p = 6.63e-3 and p = 5.0e-5, respectively). Meanwhile, the infiltration was analyzed by the QUANTISEQ method (Figure 5C and D) and observed that the CBS and CSE expression levels were significantly correlated with M1 macrophages (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively), M2 macrophages (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively), monocytes (p < 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively), natural killer (NK) cells (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively), Tregs (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively), DCs (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively), and other cells (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Figure 5.

The correlation between CBS and CSE with immune cells and immune infiltration. (A and B) The Timer method analyzed infiltration with CBS and CSE expression levels. (C and D) The QUANTISEQ method analyzed infiltration with CBS and CSE expression levels. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

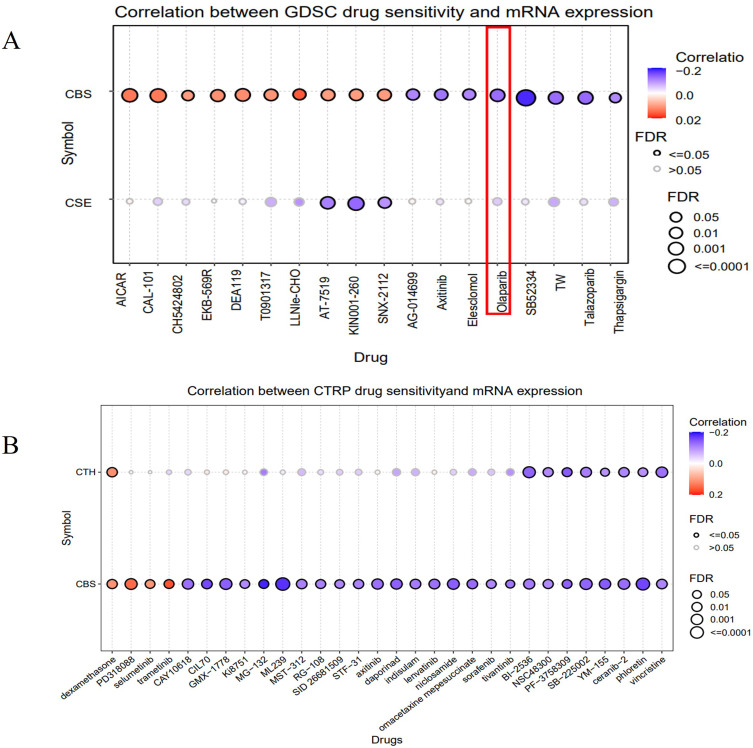

CBS and CSE Expression Levels Were Associated with Drug Sensitivity

We analyzed the sensitivities of CBS and CSE to various drugs in the GDSC and CTRP databases of the GSCA network. According to the GDSC database (Figure 6A), the CBS and CSE expression levels were either positively or negatively correlated with AG-014699, axitinib, elesclomol, olaparib, SB52334. According to the CTRP database (Figure 6B), the CBS and CSE expression levels were either positively or negatively correlated with dexamethasone, PD318088, selumetinib, trametinib, CAY10618. CBS expression was negatively correlated with olaparib which is administered against advanced and recurrent OV.

Figure 6.

CBS and CSE expression levels were associated with drug sensitivity. (A) The drug sensitivity of CBS and CSE were analyzed in the GDSC dataset. (B) The drug sensitivity of CBS and CSE were analyzed in the CTRP dataset.

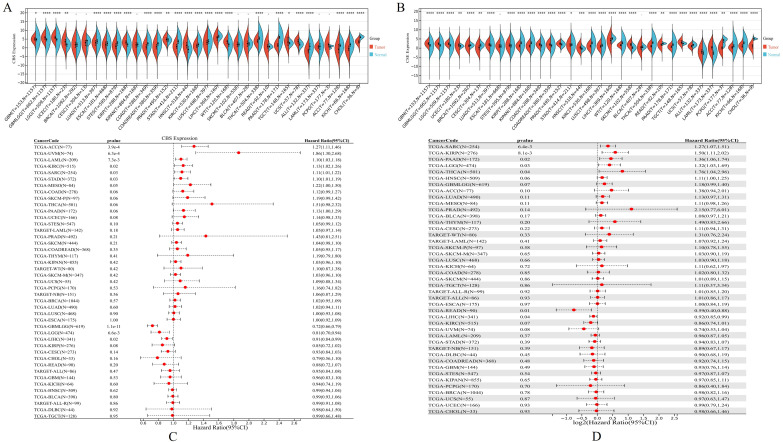

CBS and CSE are Overexpressed in Pan-Cancer and Affect Disease Prognosis

The CBS and CSE expression were evaluated in 36 different cancer types listed in the GTEx and TCGA databases (Figure 7A and B). CBS and CSE were co-upregulated in various tumors, such as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM, p = 0.04 and p = 8.7e-32, respectively), glioma (GBMLGG, p = 8.0e-50 and p = 1.4e-98, respectively), brain lower grade glioma (LGG, p = 1.5e-62 and p = 6.8e-84, respectively). Similarly, CBS and CSE were co-downregulated in various tumors, such as stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD, p = 6.0e-42 and p = 0.04, respectively), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC, p = 9.4e-8 and p = 1.9e-58, respectively), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC, p = 4.2e-7 and p = 2.6e-15, respectively). The co-overexpression of CBS and CSE was indicative of poor prognosis in sarcoma (SARC, p = 0.03; HR = 1.11(1.01,1.22) and p = 6.4e-3; HR = 1.27(1.07,1.51), respectively), while co-downregulation of CBS and CSE was indicative of poor prognosis in liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC, p = 0.02; HR = 0.91(0.84,0.99) and p = 0.04; HR = 0.92(0.85,0.99), respectively) (Figure 7C and D).

Figure 7.

CBS and CSE are overexpressed in pan-cancer and affect disease prognosis. (A and B) The CBS and CSE expression were evaluated in 36 different cancer types listed in the GTEx and TCGA databases, respectively. (C and D) Association of CBS and CSE expression with prognosis in 36 cancer types listed in the GTEx and TCGA databases. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

Discussion

H2S with carbon monoxide and nitric oxide, forms an endogenous gas family, and their physiological and pathological mechanisms are gradually gaining attention.24 More and more evidence confirmed that H2S is involved in the occurrence and progression of various diseases, including cancer.25 The H2S-synthesizing enzymes CBS and CSE were strongly upregulated in liver,26 bladder,27 renal,28 and prostate8 cancers as well as oral squamous cell carcinoma29 compared to their adjacent normal tissues.

The present work revealed that the CBS and CSE are overexpressed in ovarian cancer (OV), and also overexpressed in other various cancers. More importantly, the expression of CBS and CSE is closely related to the prognosis of OV and other various cancers. In breast cancer, a prior study investigated 30 cases and found that CSE expression was higher at stage III than at stage II.30 Moreover, CBS and CSE expression levels significantly increased with stage and were highest in metastasis.31 In bladder cancer27 and prostate cancer,8 the expression levels of CBS and CSE are related to clinical stage and pathological grade. In addition, the CBS and/or CSE expression levels are associated with drug resistance.12,32 In our study, we observed significant overexpression of CBS and CSE in cisplatin resistant cell lines. CBS and CSE are significantly elevated in drug-resistant patients. Therefore, we speculate that H2S affects the drug resistance and prognosis of ovarian cancer.

With the deepening of research, the pathophysiological mechanisms of endogenous H2S in cancer have been increasingly elucidated, including inhibit cell apoptosis, promote tumor cell productivity, and regulate immunity.33 In our study, we found that H2S participates in immune regulation. Here, H2S was closely associated with the CD4 T cell, neutrophil, macrophage, and DC infiltration scores. Yue et al34 reported that a decrease in H2S significantly reduced CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Treg differentiation and increased the CD8+T cell/Treg ratio. The authors proposed that decreasing H2S enhances the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA4 against colon cancer and suggested that H2S is an anticancer immunotherapy target. H2S-synthesizing enzymes were detected in neutrophils.35,36 Li et al37 detected CSE in rat neutrophils and its expression was regulated by induction of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway. The Immunological Genome Project (Immgen) database (https://www.immgen.org) showed that Tregs express large amounts of CBS and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) but only small quantities of CSE. Both natural and induced Tregs express substantial amounts of CBS and CSE.38 Low H2S concentrations activate T cells and upregulate activation markers such as CD69, interleukin (IL)-2, and CD25.39 H2S regulates immune cells and multiple signaling pathways. H2S modulates both canonical and non-canonical oncogenic signaling pathways such as phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR),40 Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT),41,42 Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK),40 and nitric oxide (NO).43 H2S stimulates cell proliferation via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and PI3K/Akt pathways.44–46

It has been confirmed that low concentration (endogenous) H2S can induce tumorigenesis, while high concentration (exogenous) H2S can inhibit tumorigenesis.25 With a deeper understanding of the regulatory role of H2S in tumors, donor compounds that release H2S have become alternative drugs for using H2S in anti-tumor therapy. Currently, there are donor compounds targeting the release of hydrogen sulfide for anti-tumor purposes, such as diallyl disulfide Ether (DADS), diallyl trisulfide (DATS), dithiophosphate esters (GYY4137), navitoclax (ATB-346), 5-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione (ADT-OH). These compounds have anti-tumor effects in liver cancer,47 gastric cancer,48 breast cancer,49 colorectal cancer.50 Conversely, it has a promoting effect in esophageal cancer 51 and bladder epithelial cancer.52 However, we analyzed the drug sensitivity of CBS and CSE based on data curated from the CTRP and GDSC databases in the GSCA network. We observed a negative correlation between Olaparib and CBS drug sensitivity. Olaparib improves survival in advanced and recurrent OV and is administered as maintenance therapy. CBS and CSE are closely associated with targeted drug sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma, lung cancer, colon cancer, and leukemia.53,54

Notably, while our data revealed CBS expression as a prognostic determinant in ovarian cancer (OV), no significant association was observed for CSE—a discrepancy that may stem from limited sample size or tissue-specific enzymatic activity. Future studies will involve expanded cohorts and functional validation of H2S-related enzymes (CBS/CSE) to clarify their context-dependent roles in tumor progression. However, based on our research and previous studies, we suggest that endogenous H2S, as an emerging tumor regulator, may be a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for tumors. H2S synthase inhibitors can be designed and developed for tumor therapy. The discovery and development of specific CBS and CSE inhibitors may provide opportunities for the prevention and treatment of tumors. Therefore, improving the tumor specificity and biosafety of H2S synthase inhibitors, as well as designing and developing slow-release H2S donors or H2S releasing mixed drugs as novel anti-tumor drugs, will be future research hotspots and may provide enormous value for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of tumors.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Guiding Program Project of the Zhuzhou Science and Technology Bureau (No. 201912-03) and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant Nos. 2024JJ7670).

Ethics Approval

The protocol and methodology of the present study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhuzhou Central Hospital (No. ZZCHEC2019030-01).

Disclosure

The authors have no known conflicts of interest to declare for this work.

References

- 1.Webb PM, Jordan SJ. Global epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21(5):389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saani I, Raj N, Sood R, et al. Clinical challenges in the management of malignant ovarian germ cell tumours. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(12):6089. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20126089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sebajuri JMV, Magriples U, Small M, Ntasumbumuyange D, Rulisa S, Bazzett-Matabele L. Obstetrics and gynecology residents can accurately classify benign ovarian tumors using the international ovarian tumor analysis rules. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(7):1389–1393. doi: 10.1002/jum.15234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghose A, McCann L, Makker S, et al. Diagnostic biomarkers in ovarian cancer: advances beyond CA125 and HE4. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2024;16:17588359241233225. doi: 10.1177/17588359241233225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogani G, Lopez S, Mantiero M, et al. Immunotherapy for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158(2):484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.05.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M, et al. Veliparib in ovarian cancer: a new synthetically lethal therapeutic approach. Invest New Drugs. 2020;38(1):181–193. doi: 10.1007/s10637-019-00867-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aliyuda F, Moschetta M, Ghose A, et al. Advances in ovarian cancer treatment beyond PARP Inhibitors. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2023;23(6):433–446. doi: 10.2174/1568009623666230209121732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindemann K, Gao B, Mapagu C, et al. Response rates to second-line platinum-based therapy in ovarian cancer patients challenge the clinical definition of platinum resistance. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vijayakumar S, Dhakshanamoorthy R, Baskaran A, Sabari Krishnan B, Maddaly R. Drug resistance in human cancers - Mechanisms and implications. Life Sci. 2024;352:122907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiomi M, Matsuzaki S, Serada S, et al. CD70 antibody-drug conjugate: a potential novel therapeutic agent for ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(9):3655–3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youness RA, Gad AZ, Sanber K, et al. Targeting hydrogen sulphide signaling in breast cancer. J Adv Res. 2020;27:177–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo C. Gasotransmitters in cancer: from pathophysiology to experimental therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(3):185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Untereiner AA, Pavlidou A, Druzhyna N, Papapetropoulos A, Hellmich MR, Szabo C. Drug resistance induces the upregulation of H2S-producing enzymes in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;149:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang SS, Chen YH, Chen N, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes autophagy of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(3):e2688. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu X, Xiao Y, Sun J, et al. New possible silver lining for pancreatic cancer therapy: hydrogen sulfide and its donors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(5):1148–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu D, Si W, Wang M, Lv S, Ji A, Li Y. Hydrogen sulfide in cancer: friend or foe? Nitric Oxide. 2015;50:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ascenção K, Dilek N, Augsburger F, Panagaki T, Zuhra K, Szabo C. Pharmacological induction of mesenchymal-epithelial transition via inhibition of H2S biosynthesis and consequent suppression of ACLY activity in colon cancer cells. Pharmacol Res. 2021;165:105393. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao C, Rakesh KP, Ravidar L, Fang WY, Qin HL. Pharmaceutical and medicinal significance of sulfur (SVI)-Containing motifs for drug discovery: a critical review. Eur. J Med Chem. 2019;162:679–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott KA, Njardarson JT. Analysis of US FDA-approved drugs containing sulfur atoms. top. Curr Chem. 2018;376(1):5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaorska E, Tomasova L, Koszelewski D, Ostaszewski R, Ufnal M. Hydrogen sulfide in pharmacotherapy, beyond the hydrogen sulfide-donors. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2):323. doi: 10.3390/biom10020323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar M, Sandhir R. Hydrogen sulfide in physiological and pathological mechanisms in brain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2018;17(9):654–670. doi: 10.2174/1871527317666180605072018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao W, Liu YF, Zhang YX, et al. The potential role of hydrogen sulfide in cancer cell apoptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):114. doi: 10.1038/s41420-024-01868-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stokes E, Shuang T, Zhang Y, et al. Efflux inhibition by H2S confers sensitivity to doxorubicin-induced cell death in liver cancer cells. Life Sci. 2018;213:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gai JW, Qin W, Liu M, et al. Expression profile of hydrogen sulfide and its synthases correlates with tumor stage and grade in urothelial cell carcinoma of bladder. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(4):166.e15–166.e1.66E20. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.J B Jr, Soltysova A, Hudecova S, et al. Endogenous H2S producing enzymes are involved in apoptosis induction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):591. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4508-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YH, Huang JT, Chen WL, et al. Dysregulation of cystathionine γ-lyase promotes prostate cancer progression and metastasis. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(10):e45986. doi: 10.15252/embr.201845986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meram AT, Chen J, Patel S, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is increased in oral squamous cell carcinoma compared to adjacent benign oral mucosae. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(7):3843–3852. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Teng X, Ding W, Sun K, Wang B. A clinicopathological study of 30 breast cancer cases with a HER2/CEP17 ratio of ≥2.0 but an average HER2 copy number of <4.0 signals per cell. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(8):1557–1562. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0519-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shatalin K, Nuthanakanti A, Kaushik A, et al. Inhibitors of bacterial H2S biogenesis targeting antibiotic resistance and tolerance. Science. 2021;372(6547):1169–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.abd8377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shackelford RE, Mohammad IZ, Meram AT, et al. Molecular functions of hydrogen sulfide in cancer. Pathophysiology. 2021;28(3):437–456. doi: 10.3390/pathophysiology28030028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yue T, Li J, Zhu J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide creates a favorable immune microenvironment for colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83(4):595–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thul PJ, Åkesson L, Wiking M, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science 2017;356(6340):eaal3321. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Whiteman M, Moore PK. Dexamethasone inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced hydrogen sulphide biosynthesis in intact cells and in an animal model of endotoxic shock. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(8B):2684–2692. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00610.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang R, Qu C, Zhou Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes tet1- and tet2-mediated foxp3 demethylation to drive regulatory t cell differentiation and maintain immune homeostasis. Immunity. 2015;43(2):251–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller TW, Wang EA, Gould S, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous potentiator of T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):4211–4221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.307819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong Q, Yang B, Han JG, et al. A novel hydrogen sulfide-releasing donor, HA-ADT, suppresses the growth of human breast cancer cells through inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 2019;455:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu M, Li Y, Liang B, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial fibrosis in diabetic rats through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41(4):1867–1876. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ou X, Xia T, Yang C, et al. Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway. Open Med. 2021;16(1):1318–1327. doi: 10.1515/med-2021-0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cirino G, Szabo C, Papapetropoulos A. Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide in mammalian cells, tissues, and organs. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(1):31–276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai W-J, Wang M-J, Moore PK, Jin H-M, Yao T, Zhu YC. Te novel proangiogenic efect of hydrogen sulfde is dependent on Akt phosphorylation. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;76(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manna P, Jain SK. Hydrogen sulfde and L-cysteine increase phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) and glucose utilization by inhibiting phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) protein and activating phosphoinositide 3- kinase (PI3K)/serine/threonine protein kinase (AKT)/protein kinase Czeta/lambda (PKCzeta/lambda) in 3T3l1 adipocytes. Te J Bio Chem. 2011;286(46):39848–39859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin P, Zhao C, Li Z, et al. Sp1 is involved in regulation of cystathionine-lyase gene expression and biological function by PI3K/Akt pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cell. Signalling. 2012;24(6):1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang X, Wang S, Wang Q, et al. A highly selective and sensitive fluorescence probe based on BODIPY-cyclen for hydrogen sulfide detection in living cells and serum. Talanta. 2024;268(Pt 1):125339. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2023.125339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye F, Li X, Sun K, et al. Inhibition of endogenous hydrogen sulfide biosynthesis enhances the anti-cancer effect of 3,3’-diindolylmethane in human gastric cancer cells. Life Sci. 2020;261:118348. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cui X, Liu R, Duan L, Zhang Q, Cao D, Zhang A. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) exerts therapeutic potential in triple-negative breast cancer by affecting cell cycle and DNA replication pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;161:114488. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lei YY, Feng YF, Zeng B, et al. Exogenous H2S promotes cancer progression by activating JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in esophageal EC109 cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11(7):3247–3256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panza E, Bello I, Smimmo M, et al. Endogenous and exogenous hydrogen sulfide modulates urothelial bladder carcinoma development in human cell lines. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151:113137. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iverson C, Larson G, Lai C, et al. RDEA119/BAY 869766: a potent, selective, allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/2 for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(17):6839–6847. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ascenção K, Szabo C. Emerging roles of cystathionine β-synthase in various forms of cancer. Redox Biol. 2022;53:102331. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]