Abstract

The emerging technology of inhibiting polyphenol oxidase (PPO) is crucial for preventing enzymatic browning in food. This study aimed to investigate the effects of 4.5 kJ/m2 ultraviolet (UV)-C radiation and 0.02 mg/mL L-cysteine (L-cys) treatment on the enzyme activity, physico-chemical properties, thermal properties, structure, and molecular microstructure of PPO. UV-C/L-cys decreased PPO activity and had the highest aggregation index and turbidity of PPO. UV-C/L-cys further reduced the denaturation temperature point and increased the denaturation enthalpy of PPO. UV-C/L-cys turned the α-helix to random coil of PPO and destroyed the tertiary structure. This combined treatment aggregated the microstructure of PPO, which led to covering the active center of the enzyme, leading to its inactivation. Molecular docking simulation confirmed that L-cys bound to PPO through hydrogen bonding and ionic contact. This study established a foundation for the application of UV-C radiation and L-cys treatment to control food browning.

Keywords: Polyphenol oxidase, Ultraviolet-C, L-cysteine, Molecular mechanism

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

4.5 kJ/m2 UV-C radiation and 0.02 mg/mL L-cys treatment decreased PPO activity.

-

•

UV-C/L-cys treatment reduced thermal stability of PPO.

-

•

UV-C/L-cys treatment destroyed the secondary and tertiary structure of PPO.

-

•

L-cys bound to PPO through hydrogen bonding and ionic contact.

1. Introduction

Polyphenol oxidase (PPO; EC 1.14.18.1) is a binuclear copper-containing redox metal enzyme found in various tissues and cells of plants, animals, and microorganisms (Pang et al., 2024). PPO catalyzes the hydroxylation of monophenols to o-diphenols and then inserts an oxygen molecule next to the hydroxyl group in the aromatic ring to ultimately oxidize o-diphenol to o-quinone. These o-quinones are polymerized or condensed with amino acids and sugars to form the brown pigments of postharvest fruits and vegetables, thereby contributing to browning or melanization, along with antioxidant degradation, resulting in the deterioration of food nutritional quality and low consumer acceptance (Guo et al., 2025). Therefore, it is necessary to adopt efficient and safe methods to inactivate PPO and control enzymatic browning during the storage and processing of food.

UV-C (200–280 nm) has been widely applied microbial decontamination and color protection in the processing of fruits and vegetables owing to its advantages of a low-cost and environmentally friendly non-thermal preservation technology (Dasalkar et al., 2025). UV-C can induce changes to the proteins and enzymes of functional and structural cells, including changing the secondary protein structure and causing the exposure, unfolding, and aggregation of hydrophobic residues (Amaro et al., 2024). UV-C radiation also has a positive effect on enzyme inactivation. For example, Yannam et al. (2020) found that pretreatment of coconut water with UV-C light resulted in loss of PPO and peroxidase (POD) activities, thereby inhibiting browning and extending the shelf-life of low-acid beverages. Furthermore, Sampedro and Fan (2014) established a Weibull model to describe the UV-C inactivation kinetics of lipoxygenase (LOX), PPO, and POD, showing that UV-C radiation can irreversibly inactivate LOX, POD, and PPO in orange juice and the enzyme activities did not recover after storage. However, UV-C alone has a limited effect on inactivating these browning enzymes. Therefore, developing a method combining UV-C with other processing techniques could be an effective strategy for inactivating enzymes.

L-cys is a sulfur-containing amino acid with putative anti-browning properties and is classified as a Generally Recognized as Safe drug (Su et al., 2024). For instance, treatment with 0.5 % L-cys at pH 7 resulted in the highest degree of inhibition of PPO activity to maintain the appearance of fresh-cut artichoke (Cabezas-Serrano et al., 2013). Using kinetic analysis, Zhou et al. (2018) found that the inhibition effect of L-cys on PPO was reversible. L-cys exhibits a non-competitive inhibition effect characterized by lack of competition with the substrate at the active site of PPO. Several studies have shown that L-cys treatment can inactivate PPO in fruits and vegetables (Liu et al., 2015, Colantuono et al., 2015);. The combined treatment of UV-C radiation and L-cys has been widely used in the preservation of fruits and vegetables. A previous study has shown that the combined treatment of UV-C radiation and L-cys can reduce the browning phenomenon of Lanzhou lily bulbs, which may be related to the inhibition of PPO activity (Cheng et al., 2024). However, the underlying mechanism and effect of the combined treatment of UV-C radiation and L-cys on PPO structure and features have yet to be reported.

In this study, we examined the influence of combined UV-C and L-cys treatment on the activity, physico-chemical and thermodynamic properties, structure, and molecular microstructure of PPO. The physico-chemical changes of the enzyme were reflected by the degree of protein aggregation and the thermal properties were investigated using DSC. Changes in PPO structure after treatment were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, CD spectroscopy, and fluorescence spectra. The changes in molecular microstructure were observed using atomic force microscopy (AFM). In addition, we investigated the interaction mechanism between PPO and L-cys using molecular docking simulation. Our results can provide guidance for the application of UV-C/L-cys to inhibit PPO and achieve browning control in food industry.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

PPO (≥500 U/mg), L-DOPA (≥99 % purity), and phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) were obtained from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); PPO was used as received without further purification. L-cys (≥99 % purity) and Commassie Blue Staining Solution were purchased from Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd.

2.2. Experimental set-up and treatment

UV-C treatment was carried out with a UV-C lamp bank with a peak emission at 254 nm (TUV, 30W, Philips) suspended horizontally 15 cm above the radiation vessel. A UV Light Meter (LS125, Linshang Technology Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China) was used to measure the irradiation intensity. Preliminary studies were performed to examine the effects of various irradiation doses of 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, and 5.0 kJ/m2. Twenty milliliters of PPO solution (0.2 mg/mL in 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer, pH = 6.5) was exposed to different radiation doses from a UV-C lamp bank. After radiation treatment, the PPO solution was subpacked and held at 4 °C until analysis.

Preliminary studies were performed to examine the effects of different L-cys concentrations of 0.005, 0.01, 0.015, 0.02, 0.025 mg/mL. L-cys was dissolved in PBS (pH = 6.8) to reach a final concentration and then mixed with 0.2 mg/mL PPO at 25 °C for 15 min at room temperature.

For the combined UV-C/L-cys treatment, the PPO samples were first treated with UV-C at the 4.5 kJ/m2 radiation dose and then mixed with the L-cys solution (0.02 mg/mL) for 15 min at 25 °C. All PPO samples were stored at 4 °C before analysis.

2.3. Determination of PPO residual activity

PPO activity was measured using a validated method with minor adjustments (Cheng et al., 2021). Incubate 960 μL of 15 mmol/L L-DOPA solution, 640 μL of 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), and 160 μL deionized water at 45 °C 160 μL PPO solution was added. The absorbance change was measured at 420 nm for 180 s using a spectrophotometer (FastTrack, Mettler Toledo International Trade Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). PPO activity was measured in at least three samples, and the average activity of each was represented as a percentage of the beginning activity.

2.4. PPO physico-chemical properties

2.4.1. Aggregation index (AI)

The absorbance of PPO solution was measured at 280 nm and 340 nm in triplicate on a spectrophotometer (FastTrack); 50 mmol/L PBS was used as control. The AI was calculated using the following equation:

where A280 is the absorbance at 280 nm and A340 is the absorbance at 340 nm.

2.4.2. Turbidity measurement

Turbidity was assayed according to the method reported by Shen et al. (2016) with slight modifications. In brief, the absorbance of the PPO solution was measured at 420 nm at room temperature, which served as an indicator of turbidity. The measured values of turbidity were corrected with the values of distilled water served as a blank.

2.5. DSC of PPO

The thermal properties of PPO under different treatments were measured using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC Q2000, TA, USA). The initial equilibrium temperature was 30 °C and then the temperature was increased to 140 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a 20 mL/min N2 gas atmosphere.

2.6. SDS-PAGE analysis of PPO

Changes in the protein structure of PPO were evaluated by SDS-PAGE using a 10 % separation gel and 5 % concentrated gel, following the preparation method of Fan et al. (2018). In brief, 4 μL of 6 × protein reduction-type loading buffer was mixed with 20 μL of the PPO sample solution and the mixture was slightly centrifuged. The collected supernatant (15 μL) was heated at 99 °C for 8 min, followed by electrophoresis at 100 V for 30 min and then again at 120 V for 90 min. The plate was fixed and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue on a shaking table for 180 min. After washing with distilled water, the glue was added to the Coomassie stain for decolorization overnight.

2.7. CD spectra of PPO

The secondary structure of PPO was identified by CD spectroscopy (J-815, JASCO, Japan) using the approach of Xu et al. (2022) with modifications. The PPO samples (0.02 mg/mL) from the various treatment groups were put in quartz cuvettes at 25 °C. The scanning range, scanning step, bandwidth, scanning speed, and response time were: 190–250 nm, 0.5 nm, 1 nm, 50 nm/min, and 1 s, respectively.

2.8. Fluorescence spectroscopy

The tertiary structure of PPO was investigated using a fluorescence spectrometer (F-7000, Hitachi, Japan), as reported by Zhao et al. (2020). Briefly, the samples were placed in quartz cuvettes with a 1 cm optical path length at 25 °C. Tryptophan and tyrosine were stimulated at 280 nm, and their fluorescence spectra were examined from 290 to 450 nm, where they emit. The scan rate was 200 nm/min, and the excitation and emission bandwidths were also 10 nm.

2.9. AFM analysis

AFM (Bruker Dimension Icon, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used to analyze the microstructure of PPO according to methods described by Yi et al. (2015). The PPO samples were dispersed using ultrasonic for 10 min before being applied dropwise to the flat mica sheet and dried in a fume hood. The scan range, scan rate, and resonant frequency were 5 μm × 5 μm, 0.65 Hz, and 330 kHz, respectively. Nanoscope Analysis 1.7 software (Bruck Company, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used to process and analyze the surface topography images, height, and surface roughness of PPO molecules from the AFM images.

2.10. Molecular docking

The Lamarckian genetic algorithm from the Autodock Vina program was utilized for molecular docking. The target protein's structure file was downloaded from the PDB database (PDI ID: 2y9w), and the three-dimensional structure of L-cys was studied with the PubChem tool (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5862). First, H atoms and Gasteiger-Hücker empirical charges were mixed with non-polar hydrogen, and then rotatable bonds were added to the structure files of the targets and small molecules using the AutoDockTools software. The small-molecule structure included rotatable σ bonds, but the receptor protein was considered stiff. During docking, the AutoDock Vina program used a square docking box (15.75 × 15.75 × 15.75 Å) to encompass the entire target (∼4.827, 28.48, 92.878).

2.11. Application in postharvest of Lanzhou lily blubs

2.11.1. Appearance and browning degree of lily blubs

In this study, 4.5 kJ/m2 UV-C radiation and 0.02 mg/mL L-cysteine was used to treat the lily bullbs to ananlyze the anti-browning effect. UV-C/L-cys treament was implemented by soaking in the L-cys solution for 15 min after UV-C radiation. Lily bulbs were photographed and obtained for changes in appearance every 10 d during storage of 50 d at 2 ± 0.5 °C and 90 % relative humidity. The surface color of lily bulbs was measured using an NF55 chromameter (Nippon Denshoku, Japan), with L∗, a∗, and b∗ values recorded at three different locations on each bulb's surface. The browning degree of lily bulb was determined by Liu et al. (2022). 0.5 g lily bulb sample was weighed and added with 3 mL of pre-cooled 95 % ethanol, and placed at 4 °C for 6 h. The supernatant was obtained after centrifuging at 12000 g at 4 °C for 20 min. The absorbance was measured at 410 nm, and the sample was replaced with 95 % ethanol as a blank control. The following formula was used to calculate BD:

| BD = A410 × 10 |

Where A410 was the absorption value at 410 nm.

2.11.2. Measurement of PPO activity lily blubs

The PPO activities were measured using the method described by Li et al. (2022). The tissue (2.0 g) was extracted in 50 mM precooled PBS solution (pH 7.0) containing 1 % pvp. The supernatant after centrifugation was used to estimate the PPO activities. The reaction mixture contained 0.1 M PBS (pH 6.8), 50 mM catechol and 50 μL extraction supernatant. The absorbance was measured at 420 nm 15 s after mixing the reagents. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to increase the absorbance by 0.01 per minute, and results were expressed as U/g.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All experimental measurements were performed at least in triplicate and the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All results were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Duncan's test using the statistical software program SPSS 24 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). The data were processed by Origin software. Differences between groups at P < 0.05 were considered to represent statistical significance.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Determination of UV-C dose and L-cys concentration

The screening of optimal conditions for inhibiting PPO activity through UV-C radiation and L-cys treatment revealed significant insights. As shown in Fig. S1, varying UV-C doses (3.0–5.0 kJ/m2) and L-cys concentrations (0.005–0.025 mg/mL) were evaluated for their effects on PPO residual activity. Under UV-C treatment (Fig. S1A), PPO activity exhibited a dose-dependent reduction, with the highest inhibition achieved at 4.5 kJ/m2 (86.17 %). Notably, further increasing the UV-C dose to 5.0 kJ/m2 did not enhance efficacy, suggesting a threshold effect. Similarly, L-cys treatment (Fig. S1B) exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition, with the highest inhibition achieved at 0.02 mg/mL (72.08 %). Beyond this threshold, no significant enhancement in inhibition was observed, indicating saturation of L-cys-mediated effects, likely through the competitive binding to the copper-active site of PPO (Han et al., 2021). According to preliminary experiments, 4.5 kJ/m2 UV-C and 0.02 mg/mL L-cys were selected.

3.2. PPO residual activity

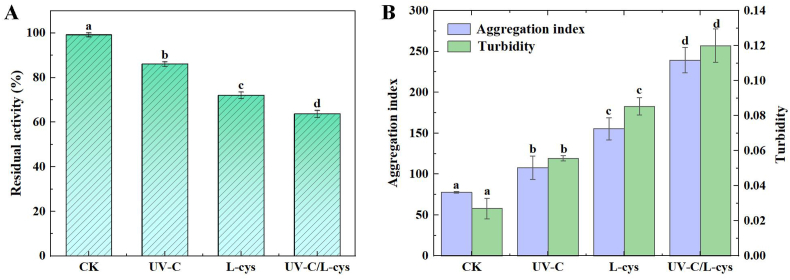

The effects of UV-C radiation, L-cys treatment, and UV-C/L-cys treatment on PPO activity are shown in Fig. 1A. UV-C therapy significantly reduced enzyme activity by 13.08 % compared to the untreated control group (CK) (P < 0.05). The decrease in PPO activity suggested that UV-C might change the spatial conformation of PPO, altering its catalytic activity. Similarly, a previous study showed that a 3.88·10−7 E min−1 dose of UV-C radiation for 100 min completely inactivated PPO in 0.18 U/mL, 0.45 U/mL, 0.14 U/mL, and 0.06 U/mL apple juice samples (Falguera et al., 2011). In addition, Amaro et al. (2024) investigated the effects of multiple wavelengths of UV-C light sources on PPO enzyme activity and found that 90 % inactivation was achieved for all wavelengths tested and fluence was established. In the present study, the PPO activity decreased by 27.17 % after L-cys treatment compared to that of the control group. This is also consistent with a previous study showing that 0.25 % L-cys treatment inhibited browning in litchi fruit by reducing the activities of peel PPO and POD enzymes during storage of 28 days at 5 ± 1 °C with 90 ± 5 % relative humidity (Ali et al., 2016). It is notable that the activity of the UV-C/L-cys group was the lowest, reaching 63.75 %, which was 35.50 % lower than that of the CK group. Since the mechanism of enzyme inactivation under UV-C radiation, L-cys treatment, and UV-C/L-cys treatment has not been fully elucidated, we further explored the structure and thermal properties of PPO after different treatments.

Fig. 1.

Residual activity (A), aggregation index, turbidity (B) of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) after UV-C, L-cys, and UV-C/L-cys treatments. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent determinations. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.3. Physico-chemical properties of PPO

The AI and turbidity can indicate the aggregation degree of proteins; therefore, we measured these properties to reflect the size and number of insoluble particles in the PPO solution under different treatments. In general, particle size in the aggregate has a substantial impact on the AI value; the larger the aggregate, the more light will be dispersed, leading to a higher AI (Siddique et al., 2017). Turbidity is considered to be a useful index to evaluate the formation of protein aggregates in solution after different treatments due to covalent and non-covalent interactions (Pellicer et al., 2018).

Fig. 1B shows the effect of the treatments on the AI value and turbidity of PPO solutions. All treatments significantly increased the AI value and turbidity compared to those of the CK group (P < 0.05). Because of hydrophobic interactions, thiol-thiol oxidation processes, and thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, the UV-C/L-cys group in particular had the highest AI value and turbidity of PPO when compared to the other treatments (Zhang et al., 2021a, Zhang et al., 2021b). According to Siddique et al. (2017), PPO's protein structure unfolded upon inactivation, exposing intramolecular hydrophobic residues within the protein that bind covalent and non-covalent protein fragments or caused unfolded monomers to aggregate, ultimately forming larger soluble molecules. In line with this finding, a previous study showed that 1.05 W/m2 UV-C radiation caused the aggregation of ovalbumin and βL-crystallin by inducing an unfolded protein structure (Espinoza et al., 2017).

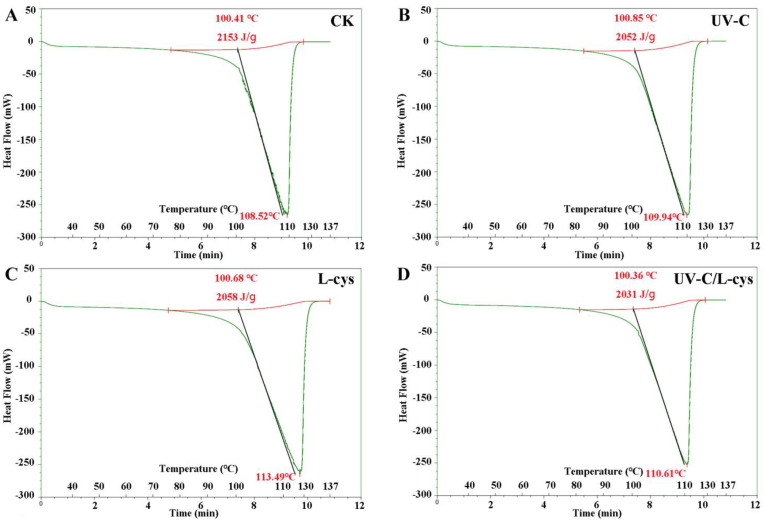

3.4. Thermal properties of PPO

DSC is widely used to detect the change of enthalpy with temperature, which can reflect the thermal denaturation and change in the functional properties of proteins. The temperature at which a protein changes from its natural state to a denatured state reflects a change in molecular structure. A higher transition temperature indicates that the stability of the protein structure is enhanced, resulting in lower energy required for denaturing the protein. The change of the peak area of enthalpy can be used to monitor protein denaturation, in which the reduction of the area of a specific peak indicates that the structure of a specific protein component is unstable (Korzeniowska et al., 2013). The Td and ΔH values represent the thermal stability and the degree of the ordered structure of the enzyme, respectively, which can be used to analyze changes in protein conformation. As shown in Fig. 2A, the CK group showed only one endothermic peak for PPO, with Td and ΔH values of 108.52 °C and 2153 J/g, respectively. However, the Td and ΔH of the UV-C–treated group were 109.94 °C and 2052 J/g (Fig. 2B), respectively, indicating that UV-C treatment changed the ordered structure of PPO. The Td and ΔH of the L-cys–treated group were 113.49 °C and 2058 J/g (Fig. 2C), respectively, which can be attributed to a typical hydrophobic interaction for the molecular force and hydrogen bond between L-cys and PPO. The Td and ΔH of the UV-C/L-cys–treated group were 110.61 °C and 2031 J/g (Fig. 2D), respectively, indicating that the combined treatment decreased the Td and increased the ΔH compared to those of the CK group. Overall, the results of DSC indicated that the UV-C/L-cys treatment reduced the thermal stability and enthalpy change, resulting in a higher aggregation degree of PPO. These results are consistent with those of Zhang et al. (2022), who showed that pressure treatment caused a decrease in the Td value, resulting in a decrease in the thermal stability of horseradish peroxidase.

Fig. 2.

DSC image of PPO under various treatments: CK (A), UV-C (B), L-cys (C), and UV-C/L-cys (D).

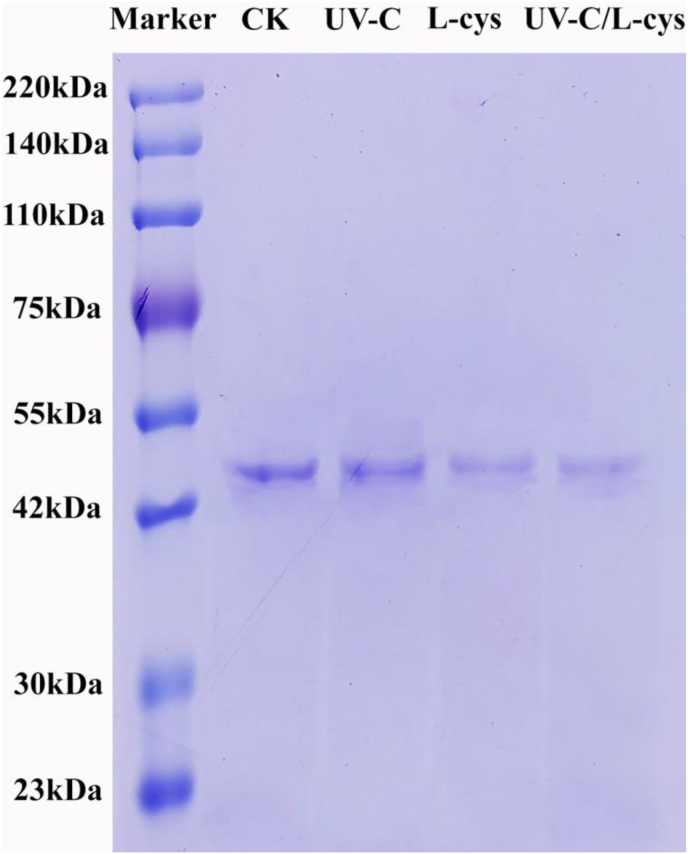

3.5. SDS-PAGE analysis

Fig. 3 shows the SDS-PAGE results of PPO solutions subject to the different treatments. All PPO bands were located at 42–55 kDa according to the marker band, corresponding to potential isoforms of PPO from Agaricus bisporus (Tian et al., 2024). The band for untreated PPO was darker than that of the others, with the color intensity becoming lighter after L-cys treatment and then even lighter with the combined UV-C/L-cys treatment. This change may be related to the effect of the treatment on protein denaturation and aggregation, resulting in reduced strength (Mizutani et al., 2018). Based on the SDS-PAGE results, we could conclude that PPO was susceptible to denaturation by UV-C/L-cys treatment, leading to the formation of larger aggregates. Yuan et al. (2021) also reported that the band intensity of PPO gradually reduced with increased time of microwave treatment, which may be related to the denaturation and aggregation of the protein due to the non-thermal or enhanced thermal effects of the microwave treatment.

Fig. 3.

Electrophoretogram of PPO standard solution after UV-C, L-cys, and UV-C/L-cys treatments.

3.6. Secondary structure analysis

The secondary structure of proteins can be identified using CD spectroscopy, which is widely used in protein conformation research because of its advantages as a fast, simple, and accurate technique. The CD features characteristic of an α-helical structure were demonstrated by the control PPO group, which displayed two negative peaks at 208 and 224 nm, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. An example of a β-sheet structure is the negative peak at 220–230 nm. PPO's CD spectra saw considerable changes at 208 and 224 nm following treatment with UV-C and L-cys, suggesting that the α-helix structure of PPO gave way to an irregular structure. The intensity and shape of the CD peaks in the group treated with UV-C/L-cys also changed significantly, indicating that the secondary structures of PPO had changed. These results were consistent with those of Zhang et al., 2021a, Zhang et al., 2021b, who found that infrared radiation and hot air treatment decreased the α-helix structure and increased the random coil structure of PPO from Acetes chinensis.

Fig. 4.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra (A), secondary structure content (%) (B), and fluorescence emission spectra (C) of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) at 280 nm.

To further analyze this transition in detail, Peakfit software was used to calculate the proportions of each secondary structure after the respective treatments. As shown in Fig. 4B, in the UV-C–treated group, the relative α-helix content dropped from 26.97 % to 20.27 % and the β-sheet content decreased from 28.81 % to 21.17 %, while the random coil proportion increased from 15.22 % to 29.73 %. Similarly, in the L-cys–treated group, the α-helix content dropped from 26.97 % to 20.61 % and the β-sheet content decreased from 28.81 % to 23.53 %, while the random coil proportion increased from 15.22 % to 33.28 %. The UV-C/L-cys–treated group showed the same trend, in which the α-helix content dropped from 26.97 % to 18.70 % and the β-sheet content decreased from 28.81 % to 24.05 %, accompanied by a decrease in β-turns, while the random coil proportion rose from 15.22 % to 39.19 %. These results indicate that UV-C/L-cys treatment destroyed the native structure of PPO, which was mainly an α-helix structure, resulting in rearrangement of the secondary structure. Similar results were obtained in a previous study demonstrating that a flat-sweep frequency and pulsed ultrasound treatment destroyed the α-helix structure of PPO, leading to enzyme inactivation (Xu et al., 2022).

3.7. Tertiary structure analysis

The intrinsic fluorescence of aromatic amino acid residues in proteins is sensitive to changes in the polarity of the surrounding environment, which makes fluorescence spectroscopy a popular technique for assessing the tertiary structure of proteins. Hydrophilic (tyrosine) Tyr residues and hydrophobic tryptophan (Trp) residues are the primary sources of endogenous fluorescence at an excitation wavelength of 280 nm (Xu et al., 2020). With an excitation wavelength of 280 nm, the CK group's peak emission wavelength was 341.6 nm, as seen in Fig. 4C. PPO's fluorescence intensity dramatically dropped (P < 0.05) following UV-C and L-cys treatments, and the maximum emission peak was constantly redshifted. The maximum wavelength changed to 344.0 nm following the combined UV-C/L-cys treatment, confirming that more fluorescent groups had formed on the protein surface, that PPO's structure had unfolded, and that the fluorescent groups had been moved to a more polar environment. This resulted in a general decrease in fluorescence intensity, which is indicative of the breakdown of PPO's tertiary structure. Zhu et al. (2022) discovered that the tertiary structure was destroyed when mushroom PPO was exposed to atmospheric cold plasma at 50 kV for 10 min, causing a redshift in the maximum fluorescence emission wavelength. The deactivation rate and the red shift of the fluorescence spectrum showed a strong exponential relationship.

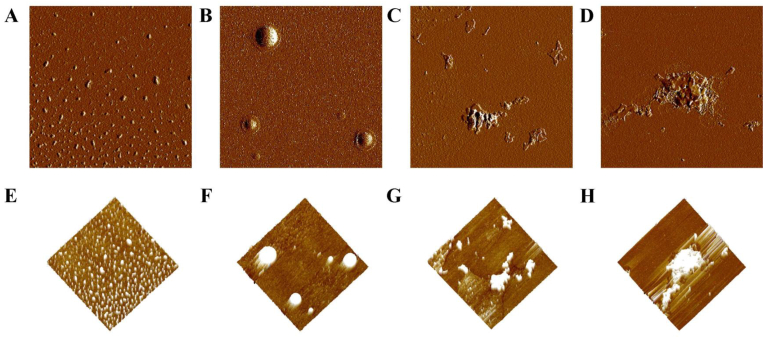

3.8. Surface topography analysis

AFM was utilized to acquire high-resolution pictures of the protein at the molecular level in order to more clearly visualize the three-dimensional structure of PPO, including the shape, diameter, and height distribution of particles (Wang et al., 2017). The impact of UV-C radiation and/or L-cys treatment on PPO's surface topography is depicted in Fig. 5. According to calculations made with NanoScope Analysis software, the proteins in the CK group had a uniform initial distribution, with each protein showing a similar height of 7.46 nm (Table 1). Following UV-C and L-cys treatments, the protein's structure displayed irregular forms and comparatively lengthy dispersed bands, and its height also increased. After UV-C/L-cys treatment, PPO molecules further polymerized to accumulate continuously, forming larger aggregates, which corresponded to the results of AI and turbidity analysis. This effect is attributed to the treatment covering the active center of the enzyme due to protein polymerization, which prevented matrix binding and ultimately led to the inactivation of PPO molecules (Tian et al., 2024). Table 1 shows the height, average roughness (Ra), and root mean square roughness (Rq) of PPO subject to the different treatments. After UV-C/L-cys treatment, the height significantly increased to 44.62 nm from 7.46 nm and the Ra value decreased to 0.12 nm from 0.55 nm and the Rq value decreased to 0.15 nm from 0.95 nm, compared to those of the control group. This indicated that the surface roughness decreased after the proteins were aggregated into macromolecular groups, thereby reducing the space for binding to the matrix, leading to the inactivation of PPO (Li et al., 2023).

Fig. 5.

Atomic force microscopy morphology 2D images under various treatments: CK (A), UV-C (B), L-cys (C), and UV-C/L-cys (D). Atomic force microscopy morphology 3D images under various treatments: CK (E), UV-C (F), L-cys (G), and UV-C/L-cys (H).

Table 1.

The height and surface roughness of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) after UV-C, L-cysteine, and UV-C/L-cys treatments. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent determinations. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

| Treatments | Height (nm) | Surface Roughness (nm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | Rq | ||

| CK | 7.46 ± 0.56a | 0.55 ± 0.02a | 0.95 ± 0.03a |

| UV-C | 19.08 ± 2.94b | 0.21 ± 0.02b | 0.27 ± 0.02b |

| L-cys | 31.64 ± 2.26c | 0.17 ± 0.02c | 0.22 ± 0.03b |

| UV-C/L-cys | 44.62 ± 3.40d | 0.12 ± 0.01d | 0.15 ± 0.01c |

3.9. Molecular docking

To further explore whether L-cys affects the binding site in addition to affecting PPO structure, we conducted a molecular docking simulation of L-cys at the PPO binding site. The calculated docking score of the binding energy for L-cys was –3.7 kcal/mol, which indicated higher affinity to the PPO protein. The docking simulation results showed that L-cys preferentially binds to the active site of PPO, which is located in the di-copper binding region. As shown in the two- and three-dimensional views in Fig. 6A and B, L-cys was located in the hydrophobic pocket of PPO and surrounded by various amino acids, including residues Phe264, Asn260, Gly281, Val283, Ala286, His210, His263, and Ser282. The hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group of L-cys serves as a hydrogen bond donor that forms a hydrogen bond with the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group in the Met280 side chain of PPO. In addition, the amino group of L-cys forms an ionic contact with the copper ion (Cu 401). These hydrogen-bonding and ionic-contact interactions help L-cys anchor onto the binding site of PPO and interact with the binding site of phenolic substrates. A previous study demonstrated that the inhibitory mechanism of L-cys on PPO involves covering the active center of mPPO, which dramatically increased the stability of the binding mode because of hydrogen bonding and ionic contact (Han et al., 2021).

Fig. 6.

Binding model of L-cys with PPO in two-dimensional (A) and three-dimensional (B) views.

3.10. Applications of UV-C/L-cys in the postharvest preservation of Lanzhou lily bulbs

3.10.1. Appearance and browning degree of lily bulbs

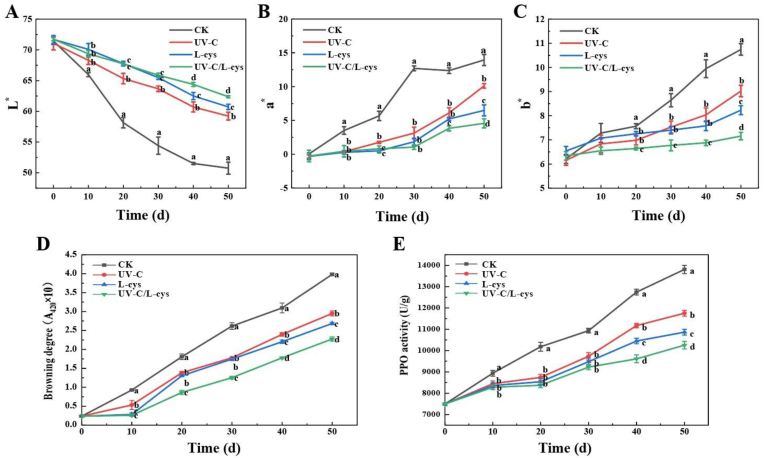

The appearance of fruits or vegetables is one of the main criteria reflecting the purchase decision of consumers (Yun et al., 2022). As shown in Fig. S2, the lily bulbs in the CK group began browning at 10 days of storage, whereas the UV-C/L-cys–treated bulbs only started to turn slightly browning at 40 days of storage, indicating that UV-C/L-cys treatment delayed the aging of lily bulbs by approximately 30 days. Fig. 7 further supported these observations during storage. In the CK group, the L∗ value (brightness) significantly decreased from 71.45 ± 0.58 to 50.75 ± 0.97 (Fig. 7A), while the a∗ value (red-green value) increased from 0.05 ± 0.01 to 13.94 ± 0.82 (Fig. 7B), and the b∗ value (yellow-blue value) rose from 6.13 ± 0.08 to 10.47 ± 0.91 (Fig. 7C) during 50 days of storage, indicating severe browning and quality deterioration of lily bulbs. In contrast, the UV-C/L-cys–treated bulbs maintained higher L∗ values, lower a∗ values and b∗ values, demonstrating effective preservation of color and freshness. Wang et al. (2022) also found that 0.05 % cysteine treatment could increase the L∗ (lightness) value to maintain the good appearance of goji fruit from days 4–6 of storage compared with that of the untreated control. Fig. 7D illustrates that the browning degree of Lanzhou lily in all groups showed a rising trend with the extension of storage time. At 50 d, the browning degree of the CK group was 3.98 ± 0.02, while that of the UV-C, L-cys, and UV-C/L-cys groups was 2.95 ± 0.07, 2.68 ± 0.04, and 2.27 ± 0.06, respectively, demonstrating that the treatments significantly reduced the browning degree (P < 0.05). Han et al. (2021) similarly showed that 8.0 kJ/m2 UV-C treatment inhibited the discoloration of fresh-cut stem lettuce during storage.

Fig. 7.

L∗(A), a∗(B), b∗(C) values, browning degree (D) and PPO activity (E) of Lanzhou lily bulbs with various treatments and stored at 2 ± 0.5 °C for 50 days. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent determinations. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.10.2. PPO activity in lily bulbs

PPO can catalyze the oxidation of a variety of simple phenols to form quinone compounds, which are further polymerized to form black polymers (Han et al., 2021). During postharvest ripening and senescence or postharvest storage and processing, the catalytic effect of PPO leads to fruit browning. As shown in Fig. 7E, the enzyme activity of the control group increased rapidly from 0 to 50 days of storage. The PPO activity of the bulbs in the UV-C/L-cys groups showed a relatively slow upward trend during storage, indicating that the browning degree was lower than that of the control group. Specifically, at 50 days of storage, the PPO activity of the CK group was 1.18-, 1.27-, and 1.35-times higher than that of the UV-C, L-cys, and UV-C/L-cys group, respectively. This may be attributed to UV-C/L-cys inhibiting PPO activity by affecting the structure of PPO.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we thoroughly analyzed the effects of UV-C radiation and L-cys treatment on the enzyme activity, physico-chemical properties, thermal properties, structure, and molecular microstructure of PPO. The results showed that the combined UV-C/L-cys treatment decreased the PPO activity and changed the protein structure from an α-helix to random coil, resulting in unfolding of the secondary structure. Fluorescence spectroscopy showed that UV-C/L-cys treatment destroyed the tertiary structure so that the microstructure of PPO became aggregated with an increased height and reduction of surface roughness of the protein. These changes led to covering of the active center of the enzyme, which ultimately contributed to loss of the catalytic function of PPO. Molecular docking simulation confirmed that L-cys binds to PPO through hydrogen bonding and ionic contact, resulting in inactivation of the enzyme. In addition, we investigated the preservation effect of UV-C/L-cys in postharvest of Lanzhou lily bulbs, which reduced the browning degree and maintain a good appearance by reducing the polyphenol oxidase of lily bulbs. This study thus provides a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism underlying PPO inactivation and offers a practical method to prevent browning in postharvest vegetables and fruits.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Le Cheng: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Haoyue Bai: Investigation. Mingfang Zhang: Visualization. Fengping Yang: Formal analysis. Difeng Ren: Research Guidance. Yunpeng Du: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Innovation Capacity Building Project of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (KJCX20251011) and the Special Project for the Construction of Industrial Technology Research Platform and Technological Capability Enhancement of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (CYJS202502).

Handling Editor: Professor Aiqian Ye

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2025.101062.

Contributor Information

Difeng Ren, Email: rendifeng@bjfu.edu.cn.

Yunpeng Du, Email: dyp_851212@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ali S., Khan A.S., Malik A.U. Postharvest l-cysteine application delayed pericarp browning, suppressed lipid peroxidation and maintained antioxidative activities of litchi fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016;121:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro K.C., Popovic V., Tadini C.C., Koutchma T. Inactivation kinetics of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase enzymes in buffer solutions by ultraviolet light sources at multiple UV-C wavelengths. J. Food Eng. 2024;377 [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas-Serrano A.B., Amodio M.L., Colelli G. Effect of solution pH of cysteine-based pre-treatments to prevent browning of fresh-cut artichokes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013;75:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Zhu Z., Sun D. Impacts of high pressure assisted freezing on the denaturation of polyphenol oxidase. Food Chem. 2021;335 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Zhang M., Bai H., Yang F., Zhang X., Ren D., Du Y. Combined ultraviolet-C radiation and L-cysteine treatment improves the post-harvest quality and volatile compounds of edible Lanzhou lily bulbs (Lilium davidii var. unicolor) by regulating reactive oxygen species metabolism. Food Chem. X. 2024;24 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantuono F., Amodio M.L., Colelli G., Castillo García S. Application of antioxidant compounds to preserve fresh-cut peaches quality. Acta Hortic. 2015;1084:633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Dasalkar A.H., Biswas A., Chaudhari S.R., Yannam S.K. Effect of UV-C LEDs and heat treatments on microbial safety, chemical and sensory properties of sweet lime juice. Food Chem. 2025;474 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.143120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza J.H., Mercado-Uribe H. Visible light neutralizes the effect produced by ultraviolet radiation in proteins. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2017;167:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falguera V., Pagán J., Ibarz A. Effect of UV irradiation on enzymatic activities and physicochemical properties of apple juices from different varieties. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2011;44(1):115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Zhang X., Zhang Q., Zhao W., Shi F. Optimization of ultrasound parameters and its effect on the properties of the activity of β-glucosidase in apricot kernels. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;52:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Ming M., Dong X., Nakamura Y., Dong X., Qi H. Polyphenol oxidase mediated (-)-epigallocatechin gallate stabilized protein in body wall of Apostichopus japonicus: characteristics and structure. Food Chem. 2025;470 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q., Liu F., Wen X., Ni Y. Kinetic, spectroscopic, and molecular docking studies on the inhibition of membrane-bound polyphenol oxidase from Granny Smith apples (Malus domestica Borkh.) Food Chem. 2021;338 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniowska M., Cheung I.W.Y., Li-Chan E.C.Y. Effects of fish protein hydrolysate and freeze–thaw treatment on physicochemical and gel properties of natural actomyosin from Pacific cod. Food Chem. 2013;138(2–3):1967–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Liu J., Xiao G., Li L., Xu Y., Yu Y., Liang Z., Xu S., Cheng L. Effects of high pressure synergistic enzymatic physical state and concentration on the denaturation of polyphenol oxidase. Food Chem. 2023;428 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Li B., Li M., Fu X., Zhao X., Min D., Li F., Li X., Zhang X. Hot air pretreatment alleviates browning of fresh-cut pitaya fruit by regulating phenylpropanoid pathway and ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022;190 [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Zhao J., Gan Z., Ni Y. Comparison of membrane-bound and soluble polyphenol oxidase in Fuji apple (Malus domestica Borkh. cv. Red Fuji) Food Chem. 2015;173:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liao L., Yin F., Song M., Shang F., Shuai L., Cai J. Integration of metabolome and transcriptome profiling reveals the effect of 6-Benzylaminopurine on the browning of fresh-cut lettuce during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022;192 [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani Y., Shibata M., Yamada S., Nanbu Y., Hirotsuka M., Matsumura Y. Effects of heat treatment under low moisture conditions on the protein and oil in soybean seeds. Food Chem. 2018;275:577–584. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H., Jia Y., Zhang Z., Xie Y., Song M., Cui B., Ye P., Chen X., Fu H., Wang Y., Wang Y. Mushroom polyphenol oxidase inactivation kinetics and structural changes during radiofrequency heating. Food Biosci. 2024;62 [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer J.A., Navarro P., Gómez-López V.M. Pulsed light inactivation of mushroom polyphenol oxidase: a fluorometric and spectrophotometric study. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018;11(3):603–609. [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro F., Fan X. Inactivation kinetics and photoreactivation of vegetable oxidative enzymes after combined UV-C and thermal processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014;23:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Shen X., Fang T., Gao F., Guo M. Effects of ultrasound treatment on physicochemical and emulsifying properties of whey proteins pre- and post-thermal aggregation. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;63:668–676. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique M.A.B., Maresca P., Pataro G., Ferrari G. Influence of pulsed light treatment on the aggregation of whey protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2017;99:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L., Fu J., Zhang X., Liu P., Li Q., Zhang S., Peng Y. Transcriptome and physicochemical analysis revealed the potential anti-browning mechanism of pre-cut L-cysteine regulated by ethylene on fresh-cut apples. Sci. Hortic. 2024;338 [Google Scholar]

- Tian X., Lv Y., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Liao X. Insight into the mechanism of high hydrostatic pressure effect on inhibitory efficiency of three natural inhibitors on polyphenol oxidase. Food Chem. 2024;457 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhang Y., Venkitasamy C., Wu B., Pan Z., Ma H. Effect of pulsed light on activity and structural changes of horseradish peroxidase. Food Chem. 2017;234:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wei L., Yan L., Zheng H., Liu C., Zheng L. Effects of postharvest cysteine treatment on sensory quality and contents of bioactive compounds in goji fruit. Food Chem. 2022;366 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Chen J., Chitrakar B., Li H., Wang J., Wei B., Zhou C., Ma H. Effects of flat sweep frequency and pulsed ultrasound on the activity, conformation and microstructure of mushroom polyphenol oxidase. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Yuan J., Wang L., Lu F., Wei B., Azam R.S.M., Ren X., Zhou C., Ma H., Bhandari B. Effect of multi-frequency power ultrasound (MFPU) treatment on enzyme hydrolysis of casein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;63 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannam S.K., Patras A., Pendyala B., Vergne M., Ravi R., Gopisetty V.V.S., Sasges M. Effect of UV-C irradiation on the inactivation kinetics of oxidative enzymes, essential amino acids and sensory properties of coconut water. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57(10):3564–3572. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04388-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J., Yi J., Dong P., Liao X., Hu X., Zhang Y. Effect of high-hydrostatic-pressure on molecular microstructure of mushroom (Agaricusbisporus) polyphenoloxidase. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2015;60(2):890–898. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J., Hou Z., Wang D., Qiu Z., Gong M., Sun J. Microwave irradiation: effect on activities and properties of polyphenol oxidase in grape maceration stage. Food Biosci. 2021;44 [Google Scholar]

- Yun Z., Gao H., Chen X., Duan X., Jiang Y. The role of hydrogen water in delaying ripening of banana fruit during postharvest storage. Food Chem. 2022;373 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Yu X., Xu B., Yagoub A.E.A., Mustapha A.T., Zhou C. Effect of intensive pulsed light on the activity, structure, physico-chemical properties and surface topography of polyphenol oxidase from mushroom. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021;72 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Zhou G., Chen L., Sun L., Fei L., Lyu F., Ding Y. Effect of infrared radiation on activity and conformation of polyphenol oxidase from Acetes chinensis. J. Food Sci. 2021;86(10):4500–4510. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zheng Z., Zheng C., Zhao Y., Jiang Z. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure on activity, thermal stability and structure of horseradish peroxidase. Food Chem. 2022;379 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Yu X., Zhou C., Yagoub A.E.A., Ma H. Effects of collagen and casein with phenolic compounds interactions on protein in vitro digestion and antioxidation. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2020;124 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Xiao Y., Meng X., Liu B. Full inhibition of Whangkeumbae pear polyphenol oxidase enzymatic browning reaction by l-cysteine. Food Chem. 2018;266:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Elliot M., Zheng Y., Chen J., Chen D., Deng S. Aggregation and conformational change of mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) polyphenol oxidase subjected to atmospheric cold plasma treatment. Food Chem. 2022;386 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.