Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

To systematically evaluate the intervention effect of modified constraint-induced movement therapy (m-CIMT) on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

A computer-based search was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science and China National Knowledge Infrastructure for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the intervention effect of m-CIMT on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke, with the search conducted up until 23 May 2024.

Eligibility criteria

We included only RCTs in which patients who had a stroke performed m-CIMT or m-CIMT in addition to the control group, and the outcome was upper limb function.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction and synthesis used the reporting checklist for systematic review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. The risk of bias and methodological quality of included studies were evaluated by two independent investigators under the guidance of Cochrane risk of bias. Effect sizes were pooled, funnel plots were created and subgroup analyses were conducted using Stata V.17.0. If I²>50%, a random-effects model was applied; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots and Egger’s test. In the presence of publication bias, a trim-and-fill method was employed for further examination. The quality of evidence was evaluated using GRADEpro.

Results

A total of 16 studies including 612 patients were included. Rehabilitation outcomes were assessed using the Fugl–Meyer Assessment (I²=90.34%), Motor Activity Log—Quality of Movement (I²=36.02%), Motor Activity Log—Amount of Use (I²=65.76%), Action Research Arm Test (I²=62.66%) and the Wolf Motor Function Test (I²=36.78%). Low-level evidence suggests that m-CIMT improves upper limb function in patients who had a stroke (all p<0.05). Subgroup analyses indicate that m-CIMT is effective in patients with ‘chronic stroke’ (p=0.001) and in patients who had a stroke with a course duration of ‘>2 months’ (p=0.005). Intervention periods of ‘2–4 weeks’ (p=0.008) and ‘5–12 weeks’ (p<0.01), as well as intervention durations of ‘30–60 min’ (p=0.006) and ‘120–180 min’ (p=0.045), were all found to improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke.

Conclusion

Low-level evidence suggests that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke, although some indicators exhibit high heterogeneity. Therefore, this conclusion should be interpreted with caution. m-CIMT appears to improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke with a course duration of more than 2 months, as well as in patients with chronic stroke. The intervention period should be at least 2 weeks, and each training session should last at least 30 min. Future studies should adopt more rigorous methodologies and larger sample sizes to further validate the efficacy of m-CIM.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42024550028.

Keywords: Stroke, Stroke medicine, Meta-Analysis, REHABILITATION MEDICINE

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This systematic review, conducted in accordance with the PROSPERO 2020 guidelines, included relevant randomised controlled trials and systematically evaluated the effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke, yielding more reliable and robust results.

Additionally, the review explored the moderating effects of stroke type, disease duration, intervention period and intervention time, providing evidence-based recommendations for the development of future intervention protocols.

Although the review examined the moderating effects of individual factors and the ‘dose–response’ relationship, the combined effects of multiple factors were not addressed.

Due to the presence of publication bias and heterogeneity, the overall level of evidence in this systematic review is classified as low; thus, caution should be exercised when interpreting these findings.

Introduction

Stroke is a disease featuring brain damage caused by the rupture or blockage of blood vessels, preventing blood from flowing into the brain. There are 10.3 million new cases of stroke in the world every year, and up to 1.2 million people are disabled due to stroke every year, which has become the first cause of disability in the world.1 2 Besides, it has become the leading cause of disability worldwide.2 Motor dysfunction is one of the main obstacles for patients who had a stroke as approximately 85% and 55–75% of patients who had a stroke experience motor impairment of varying degrees and upper limb dysfunction, respectively, which impacts their daily life abilities and imposes a heavy burden on families and society.3

Modified constraint-induced movement therapy (m-CIMT) is an improvement on CIMT. This new rehabilitation technique positively affects the recovery of upper limb function in patients who had a stroke.4 m-CIMT is optimised in the limitation time and training intensity and focuses on strengthening the coordination of bilateral limbs to improve the compliance of patients.5 Studies have indicated that a 2-week course of m-CIMT can effectively improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke.6 This may be because m-CIMT limits the movement of the healthy limb, focuses on the affected limb, exercises a lot and repeatedly, and achieves the behavioural goal by gradually increasing the difficulty of the activity, that is, the ‘shaping technique’. According to neural plasticity, m-CIMT eventually promotes the application-dependent reorganisation of cortical function.7 However, some studies have yielded different results, suggesting that, compared with conventional treatment, m-CIMT only improves the perceived use of the affected limb in patients who had a stroke, but has no effect on upper limb motor function.8

Currently, several studies have explored the intervention effects of m-CIMT. However, many issues still warrant further investigation. First, the results from previous studies are controversial.7 9 10 This may be related to differences in patient characteristics and intervention characteristics. A systematic review by Nasb et al indicated that a 4-week intervention does not improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke and suggested that longer interventions might lead to better outcomes.10 Additionally, factors like disease duration can affect recovery as some studies propose that patients who had a stroke undergo a phase of spontaneous recovery, typically occurring within the first 3–6 months post-stroke.11 Lastly, the assessment tools used in these studies were not comprehensive.

Based on this, we included more assessment tools and used meta-analysis to systematically evaluate the effect of m-CIMT on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke. We further explored the effects of intervention cycle, disease duration, stroke type and intervention duration on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke, aiming to provide guidance or suggestions for selecting upper limb rehabilitation treatments for patients who had a stroke, hoping to improve the level of recovery from upper limb functional impairments in patients who had a stroke.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This study strictly followed the requirements of the international systematic review writing guidelines for data inclusion and statistical analysis.12 The research protocol has been registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/; registered no. CRD42024550028).

Eligibility criteria

Study subjects were patients who had a stroke who met the diagnostic criteria for stroke, aged>18 years and were not limited to any kind of stroke. The intervention group received m-CIMT or m-CIMT in addition to the interventions provided to the control group. The control group received standard rehabilitation or conventional treatment. Intervention group: m-CIMT or m-CIMT based on the intervention of the control group. Control group: conventional rehabilitation, standard treatment, etc. The primary outcome measure was the Fugl–Meyer Assessment (FMA), and the secondary outcome measures were the Motor Activity Log—Quality of Movement (MAL-QOM), Motor Activity Log—Amount of Use (MAL-AOU), Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT) and Action Research Arm Test and Motor Activity (ARAT). Data from these measures were extractable. The study design was a randomised controlled trial (RCT), and the language of the articles was either Chinese or English.

Information sources

ZW and CW independently searched the PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases until 23 May 2024. The search strategy combined subject headings with free words, using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” for combination, and was confirmed after repeated pre-checks. Detailed search strategies are provided in online supplemental appendix 1.

Study selection and data collection

ZW and CW independently completed the literature screening according to a standardised process. First, the retrieved literature was imported into Endnote X9 to summarise and remove duplicate publications. Second, the titles and abstracts of the literature were read in Endnote X9 for initial screening, and finally, the literature that passed the initial screening was read in full text for further screening. In case of any disagreements, discussions will be held with YZ until a consensus is reached.

Data items

ZW and CW independently extracted basic information, intervention characteristics and outcome indicators from the literature that met the inclusion criteria. Basic information included author, year, country, sample size, stroke type, age and disease progress. Intervention characteristics included intervention content, frequency, duration and cycle for the intervention group, as well as intervention content for the control group. The data processing format for outcome indicators was the change in effect size before and after the experiment (mean±SD). In case of any disagreements, discussions will be held with YZ until a consensus is reached. If any issues arise or information is missing, the corresponding author will be contacted via email (See appendix 7).

Subgroup analysis coding

To explore the sources of heterogeneity, this study coded the following factors. We coded the type of patients who had a stroke as acute stroke, chronic stroke and unclear. The acute stage of stroke was defined as less than 3 months post-stroke and the chronic stage as 6 months post-stroke.13 The duration of stroke was coded as ‘≤2 months’ and ‘> 2 months’. ‘≤2 months’ was defined as the time from the onset of stroke to the initiation of m-CIMT intervention being less than 2 months, while ‘> 2 months’ was defined as the time from stroke onset to the start of m-CIMT intervention being ‘≥ 2 months’. The intervention period was coded as ‘2–4 weeks’ and ‘5–12 weeks’. ‘2–4 weeks’ was defined as the period during which patients who had a stroke received m-CIMT for 2–4 weeks, and ‘5–12 weeks’ was defined as the period during which patients who had a stroke received m-CIMT for 5–12 weeks. The duration of a single intervention was coded as ‘30–60 min’ and ‘120–180 min’. ‘30–60 min’ was defined as the duration of each m-CIMT session being between 30 and 60 min, while ‘120–180 min’ was defined as the duration of each m-CIMT session being between 120 and 180 min.

Risk of bias in individual studies

ZW and CW independently evaluated the risk of bias in the included literature using Cochrane’s risk-of-bias tool (Rob 2). The tool has five different domains used to generate the overall Rob. The RoB judgement for the second domain (RoB due to deviations from the intended interventions) was carried on to quantify the effect of assignment to intervention. Each domain was evaluated with one of the following options: ‘Low RoB’, ‘Some Concerns’ and ‘High RoB’. Following the individual domain assessment, we then categorised studies with just one out of five risk domains with a ‘Some Concerns’ judgement as a ‘Low RoB’. Studies with two or more ‘Some Concerns’ judgements were judged as ‘Some Concerns’. Studies with one domain in ‘High RoB’ were judged as ‘High RoB’. In case of any disagreements, discussions will be held with Y until a consensus is reached.

Credibility assessment

ZW and CW used GRADEpro to assess the level of evidence for the results. There are five evaluation items: limitations, inconsistencies, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. Each item was evaluated separately, and the level of evidence was classified into four grades: high quality, moderate quality, low quality and very low quality.12 In case of any disagreements, discussions will be held with YZ until a consensus is reached.

Statistical methods

The main outcome indicator of this study is the FMA. Therefore, Stata V.17.0 was used for meta-analysis, forest plot creation, subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis and publication bias testing for FMA only. If publication bias is detected, the trim-and-fill method will be used for further assessment. Meta-analysis and forest plot creation were conducted for secondary outcome indicators. Hedges’s g was used for effect size combination, and precision calculation was used to calculate the bias correction factor. Hedges and Olkin correction SE was used to calculate the effect size. The magnitudes of effect size considered (1) small (g<0.20), (2) small-to-moderate (g=0.20–0.49), (3) moderate (g=0.5–0.79) and (4) large (g≥0.80).14Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with thresholds of 75%, 50% and 25% representing high, moderate and low heterogeneity, respectively. If I2>50%, a random-effects model will be used for pooling effect sizes15 as the random-effects model is more conservative and can adjust the algorithm for combining effect values. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model would have been adopted. If heterogeneity was present, subgroup analysis was performed to explore its potential sources. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis using the leave-one-out approach was conducted, sequentially excluding each study to assess its impact on the overall results.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Results of the literature search

A total of 1706 articles were retrieved. After removing 702 duplicates, 1005 articles were screened based on titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 922 irrelevant articles. Then, the remaining 83 articles were downloaded in full text, of which 27 could not be found. Therefore, 56 articles were read in full text: 6 were excluded due to outcome indicators not meeting the criteria, 4 were conference papers or reviews, 21 were excluded due to inconsistent intervention methods, 4 were non-RCT studies and 5 were excluded due to unobtainable data. Finally, 16 articles were included16,31 (see online supplemental appendix 2).

Basic information of included literature

16 studies (612 patients) were included, published between 2004 and 2022. Nine studies were from Asia, three from Europe, one from South America, two from Oceania and one from Africa. Stroke types included acute and chronic, and some studies did not specify the type. The age of the patients ranged from 39 to 94 years old, with disease duration ranging from 2 days to 35 months (see online supplemental appendix 3).

Intervention characteristics of included literature

The 16 included studies had intervention groups receiving m-CIMT, m-CIMT combined with conventional rehabilitation and m-CIMT combined with conventional rehabilitation and botulinum A toxin. The intervention duration ranged from 30 to 180 min. Most intervention cycles lasted 2–3 weeks. The intervention frequency was mostly 5 days per week. Outcome indicators included FMA-UE, MAL, WMFT and ARAT (see table 1).

Table 1. Intervention characteristics of included studies.

| Included studies | Intervention group content | Control group content | Outcome indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kwakkel et al16 | m-CIMT, 3 days/week, 60 min, 3 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, MAL, ARAT, WMFT |

| Lin et al17 | m-CIMT+usual care, 120 min, 5 days/week, 3 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, MAL |

| Nasb et al18 | m-CIMT+botulinum A toxin+usual care, 60 min, 6 days/week, 4 weeks | Botulinum A toxin+usual care | FMA-UE |

| Singh et al19 | m-CIMT, 120 min, 5 days/week, 2 weeks | Standard physical therapy treatment | FMA-UE |

| Thrane et al20 | m-CIMT,180 min, 10 consecutive working days | Usual care | FMA-UE, WMFT |

| Wu et alA21 | m-CIMT+usual care, 120 min, 5 days/week, 3 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, MAL |

| EL-HELOW et al 30 | m-CIMT, 120 min, 5 days/week, 2 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, ARAT |

| Sethy et al31 | m-CIMT, 60 min, 5 days/week, 8 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, MAL, ARAT |

| Liu et al23 | m-CIMT, 60 min, 5 days/week, 2 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, ARAT |

| Alaca24 | m-CIMT+usual care, 30 min, 5 days/week, 6 weeks | Usual care | MAL, ARAT |

| Baldwin et al25 | m-CIMT, 60 min, 6 days/week, 2 weeks | Usual care | MAL, WMFT |

| Lin et al26 | m-CIMT, 120 min, 5 days/week,3 weeks | Usual care | MAL |

| Smania et al27 | m-CIMT, 120 min, 5 days/week, 2 weeks | Usual care | MAL, WMFT |

| Page et al28 | m-CIMT, 30 min, 3 days/week,10 weeks | Usual care | FMA-UE, ARAT |

| Wu et al22 | m-CIMT+ usual care, 120 min, 5 days/week, 3 weeks | Usual care | MAL |

| Yu et al29 | m-CIMT, 180 min, 10 days | Usual care | MAL, WMFT |

ARAT, Action Research Arm Test and Motor Activity; FMA-UE, Fugl–Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity; MAL, Motor Activity Log; m-CIMT, modified constraint-induced movement therapy; WMFT, Wolf Motor Function Test.

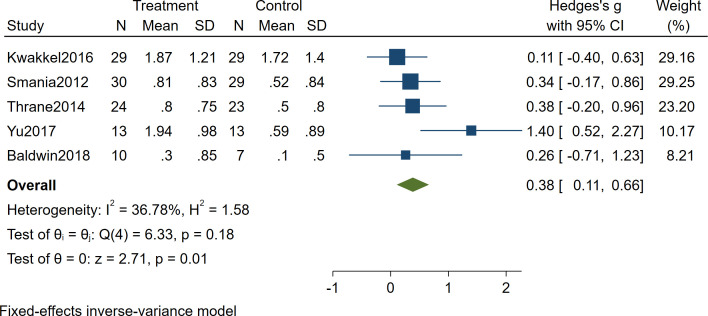

Assessment of bias risk

A total of 16 studies described the ‘randomisation process’. Also, 8 studies were assessed as having a low risk of bias in the domain of ‘Deviations from the intended interventions’, while 12 studies exhibited a low risk of bias in ‘Missing outcome data’. Additionally, 10 studies were identified as having a low risk of bias in ‘Measurement of the outcome’, and 9 studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in ‘Selection of the reported result’. Overall, 3 studies were categorised as low risk, 3 as high risk and 10 as having ‘Some concerns’ (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The risk of bias in the included studies.

Meta-analysis of the effects of m-CIMT on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke

Meta-analysis of the effects of m-CIMT on FMA in patients who had a stroke

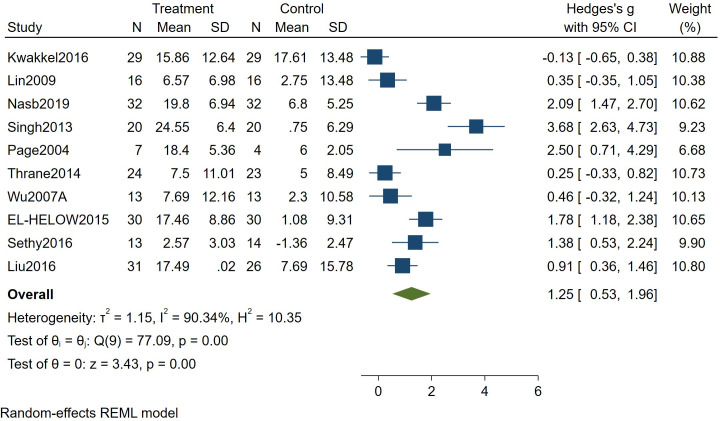

10 studies (422 patients) investigated the change in FMA scores in patients who had a stroke following m-CIMT. Effect sizes were pooled using a random-effects model (I2=90.34%). The results indicated that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke (Hedges’s g of 1.25, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.96, p=0.00) (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the effect of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on Fugl–Meyer Assessment in patients who had a stroke. REML, Restricted Maximum Likelihood.

To explore the sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted on factors that may contribute to heterogeneity. However, due to commonalities in intervention frequency, subgroup analyses could not be performed. Therefore, subgroup analyses were performed only for patients' intervention period, time of single intervention, stroke type and course of disease in patients who had a stroke.

The results indicated that the heterogeneity may stem from the intervention cycle. The intervention cycle was categorised into ‘2–4 weeks’ (I2=92.71%) and ‘5–12 weeks’ (I2=17.59%), and m-CIMT in both cycles was found to improve upper limb function (all p<0.05). Stroke type, disease duration and the duration of each intervention session were not sources of heterogeneity. Furthermore, m-CIMT was effective only in patients with ‘chronic stroke’ (Hedges’s g=1.69, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.42, p=0.001) and in those with a disease duration of ‘>2 months’ (Hedges’s g=1.55, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.87, p=0.005). Additionally, m-CIMT sessions lasting ‘30–60 min’ (Hedges’s g=1.25, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.14, p=0.006) and ‘120–180 min’ (Hedges’s g=1.27, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.51, p=0.045) also improved upper limb function (see table 2).

Table 2. Subgroup analysis of the effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on Fugl–Meyer Assessment in patients who had a stroke.

| Moderator | N | I2 | Hedges’s g | 95% CI | P value | Model of effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke type | ||||||

| Acute stroke | 2 | 95.66 | 0.82 | −1.06 to 2.69 | 0.39 | Random |

| Chronic stroke | 5 | 90.18 | 1.69 | 0.52 to 2.87 | 0.005 | Random |

| Unclear | 3 | 89.80 | 0.94 | −0.21 to 2.09 | 0.11 | Random |

| Duration of disease (months) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 3 | 91.86 | 0.62 | −0.52 to 1.77 | 0.283 | Random |

| >2 | 6 | 88.32 | 1.55 | 0.67 to 2.42 | 0.001 | Random |

| Cycle of intervention (weeks) | ||||||

| 2–4 | 8 | 92.71 | 1.14 | 0.30 to 1.97 | 0.008 | Random |

| 5–12 | 2 | 17.59 | 1.59 | 0.82 to 2.36 | 0.001 | Fix |

| Intervention duration (min) | ||||||

| 30–60 | 5 | 88.04 | 1.25 | 0.36 to 2.14 | 0.006 | Random |

| 120–180 | 5 | 93.80 | 1.27 | 0.03 to 2.51 | 0.045 | Random |

To further explore the source of heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was performed on FMA, whose results indicated that Kwakkle 2016 might be the source of heterogeneity (see online supplemental appendix 4.

Publication bias was assessed for FMA, and the funnel plot showed a noticeable asymmetry, with some studies falling outside the 95% CI lines, indicating a certain degree of publication bias (see online supplemental appendix 5). Egger’s test for small-study effects on FMA yielded Z=1.99, p=0.047, indicating the presence of small-sample bias. Trim-and-fill analysis was conducted with a maximum of 2000 trim-and-fill iterations, and the results showed no change in effect size, indicating robust results.

Meta-analysis of the effects of m-CIMT on MAL in patients who had a stroke

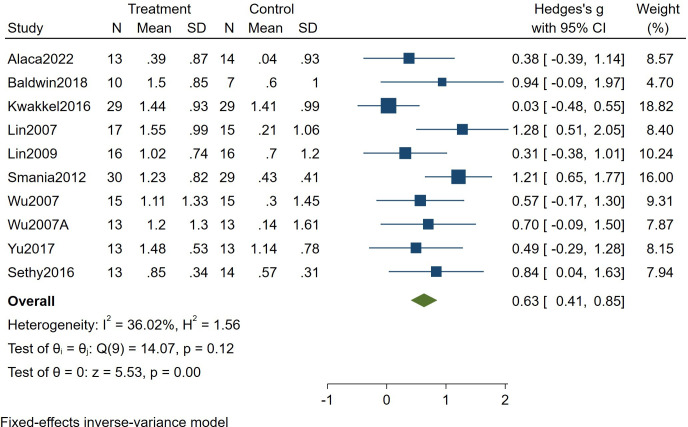

10 studies (334 patients) investigated the changes in MAL-QOM scores in patients who had a stroke conducting m-CIMT. Effect sizes were pooled using a fixed-effects model (I2=36.02%). The results demonstrated that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke (Hedges’s g=0.63, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.85, p=0.00) (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of the effect of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on Motor Activity Log—Quality of Movement in patients who had a stroke.

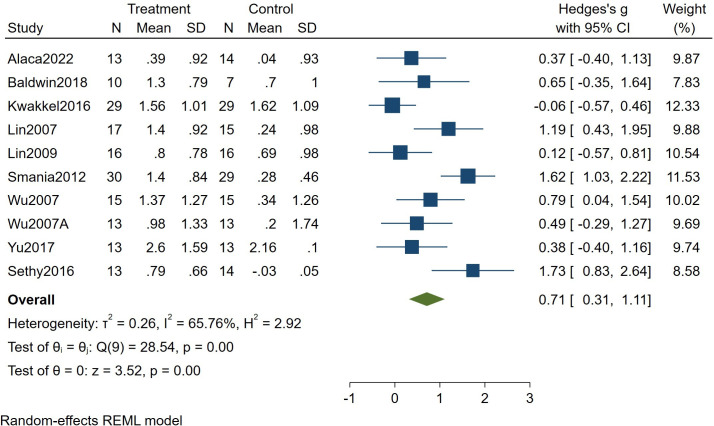

10 studies (334 patients) investigated the change in MAL-AOU scores in patients who had a stroke conducting m-CIMT. Effect sizes were pooled using a random-effects model (I2=65.76%). The results indicated that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke (Hedges’s g=0.71, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.11, p=0.00) (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot of the effect of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on Motor Activity Log—Amount of Use in patients who had a stroke. REML, Restricted Maximum Likelihood.

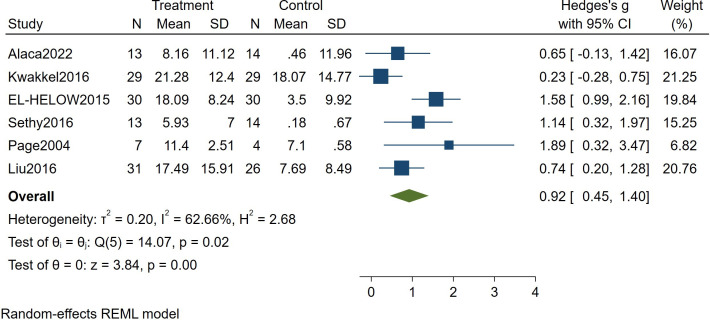

Meta-analysis of the effects of m-CIMT on ARAT in patients who had a stroke

Five studies (240 patients) investigated the change in ARAT scores in patients who had a stroke conducting m-CIMT. Effect sizes were pooled using a random-effects model (I2=62.66%). The results indicated that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke (Hedges’s g=0.92, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.40, p=0.00) (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot of the effect of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on Action Research Arm Test and Motor Activity in patients who had a stroke. REML, Restricted Maximum Likelihood.

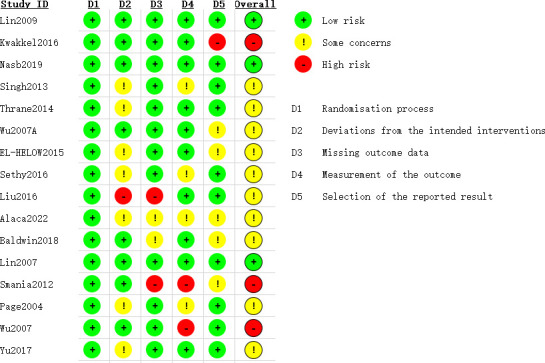

Meta-analysis of the effects of m-CIMT on WMFT in patients who had a stroke

Five studies (207 patients) investigated the change in WMFT scores in patients who had a stroke conducting m-CIMT. Effect sizes were pooled using a fixed-effects model (I2=36.78%). The results demonstrated that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke (Hedges’s g=0.38, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.66, p=0.01) (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Forest plot of the effect of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on Wolf Motor Function Test in patients who had a stroke.

Evaluation of evidence quality

This study conducted a level of evidence evaluation for the meta-analysis results of FMA, ARAT, WMFT and MAL. However, the evidence levels for all of them were rated as low (see online supplemental appendix 6).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown conflicting results regarding the effectiveness of m-CIMT in improving upper limb function in patients who had a stroke, highlighting the need for further research. The findings of this study indicate that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke. This may be due to the significant improvements observed in the affected limb following intensive and concentrated rehabilitative training. Such training can lead to the expansion of the affected motor cortex and the recruitment of new ipsilateral cortical regions, inducing structural changes in the nervous system, which in turn promotes brain plasticity and neural functional reorganisation.32 Consequently, this leads to improved upper limb function. Furthermore, m-CIMT can increase the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factors, which facilitate neural development and promote recovery.33 However, other studies have reached different conclusions. A systematic review by Nasb et al indicated that botulinum toxin A combined with m-CIMT does not improve upper limb function.10 The inconsistency in results may be due to differences in the study design: Nasb et al investigated the combined effects of botulinum toxin A and m-CIMT after a 4-week intervention, whereas the present study only focused on the impact of m-CIMT without restricting the intervention period. This study demonstrated high heterogeneity in the FMA and MAL-AOU outcomes, suggesting that further investigation is needed in future research. However, the heterogeneity may stem from differences in patient characteristics and intervention protocols.34 To explore the sources of heterogeneity, this study conducted a subgroup analysis, which revealed that the intervention period is a moderating factor. Specifically, the duration of m-CIMT intervention may influence the recovery of upper limb function in patients who had a stroke. Therefore, future studies on m-CIMT interventions for improving upper limb function in patients who had a stroke should consider the impact of the intervention period. However, the evidence level of this study’s findings is low. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution, and further research is required to validate them.

Our study found that m-CIMT could improve upper limb function only in ‘chronic stroke’ patients and stroke duration ‘> 2 months’, whereas no improvement was observed in ‘acute stroke’ patients and those with a stroke duration of ‘<2 months’. Zhang et al indicated that both m-CIMT and CIMT can improve motor function in both acute and chronic patients who had a stroke. This finding contrasts with the results of our study, which focused solely on upper limb function, whereas Zhang et al examined overall motor function.35 After stroke, rapid early functional recovery may occur due to metabolic recovery of the ischaemic penumbra, improvement in local circulation and partial recovery of ischaemic neurons. However, this situation typically occurs 3–6 months after the stroke onset. Therefore, the improvement of m-CIMT only in patients with disease duration ‘>2 months’ and ‘chronic stroke’ does not exclude the role of spontaneous recovery.11 Future studies should consider the impact of spontaneous recovery in patients who had a stroke. Moreover, some studies suggest that m-CIMT or CIMT may not be suitable for acute patients who had a stroke as early intervention may worsen the condition.36 Therefore, future research should also focus on stroke patient type and disease duration to better clarify the intervention effects of m-CIMT.

Our study also found that intervention cycles of ‘2–4 weeks’ and ‘5–12 weeks’, and single intervention duration of ‘30–60 min’ and ‘120–180 min’ showed positive improvements. Similar results were also reported in other studies.16 Baldwin et al compared the effects of m-CIMT and conventional therapy on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke with a 2-week intervention cycle and a follow-up at the 4th week post-intervention and found that m-CIMT improved upper limb function in patients who had a stroke compared with symbols of pre-intervention.25 However, other studies have reported that daily intervention times of 1–5 hours and intervention periods longer than 14 days did not lead to improvements in motor function.37 Longer intervention durations or cycles may reduce patient interest and adherence, resulting in diminished rehabilitation outcomes.38 Additionally, the content of the intervention may also influence the rehabilitation effects. Techniques such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), motor imagery therapy and virtual reality have been shown to promote stroke rehabilitation, but the effects vary across different interventions.39 tDCS, for example, has demonstrated the greatest improvement in patients who had a stroke’ activities of daily living. However, m-CIMT shows more advantages in improving upper limb function in patients who had a stroke.40 Therefore, rehabilitation plans should be tailored to address the specific needs of patients who had a stroke.

Limitations

However, this study also has certain limitations: the literature included in this study is in Chinese and English, so the comprehensiveness of the included literature is insufficient to a certain extent. Although all the included studies were RCTs, some did not implement double-blind procedures, and the quality of some studies was low, which may have impacted the results. This study only conducted a subgroup analysis of the FMA, and no improvement effects were observed for acute stroke. Furthermore, some results of this study exhibited high heterogeneity, there was publication bias and the overall level of evidence was low. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Recommendations for the future

Future research should design intervention protocols tailored to patient types and disease duration, based on patient characteristics. More rigorous methodological designs should be adopted, with larger sample sizes and multicentre RCTs. Moreover, standardised and more objective assessment tools should be used whenever possible to reduce heterogeneity between studies, aiming to demonstrate the efficacy of m-CIMT on upper limb function in patients who had a stroke. Additionally, studies in multiple languages should be included to mitigate publication bias. Furthermore, future studies should continue to explore the combined effects of various factors in order to obtain more reliable results.

Conclusions

The low level of evidence indicates that m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke, but the results should be interpreted with caution. m-CIMT can improve upper limb function in patients who had a stroke with a disease duration of more than 2 months and in patients with chronic stroke. The intervention period should be at least 2 weeks, and the duration of each training session should be at least 30 min. Future research should adopt more rigorous methodologies and larger sample sizes to further validate the efficacy of m-CIMT.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-094309).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Data availability free text: The following information was supplied regarding data availability.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Pandian JD, Gall SL, Kate MP, et al. Prevention of stroke: a global perspective. Lancet. 2018;392:1269–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Q, Li R, Wang L, et al. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990-2019: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e897–906. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00228-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C-Y, Chiang W-C, Yeh Y-C, et al. Effects of virtual reality-based motor control training on inflammation, oxidative stress, neuroplasticity and upper limb motor function in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2022;22:21. doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02547-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, et al. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2095–104. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page SJ, Levine P, Leonard AC. Modified constraint-induced therapy in acute stroke: a randomized controlled pilot study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19:27–32. doi: 10.1177/1545968304272701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, Zhao J-L, Zhu Q-X, et al. Comparison of conventional therapy, intensive therapy and modified constraint-induced movement therapy to improve upper extremity function after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:619–25. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi YX, Tian JH, Yang KH, et al. Modified constraint-induced movement therapy versus traditional rehabilitation in patients with upper-extremity dysfunction after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:972–82. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barzel A, Ketels G, Stark A, et al. Home-based constraint-induced movement therapy for patients with upper limb dysfunction after stroke (HOMECIMT): a cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleet A, Page SJ, MacKay-Lyons M, et al. Modified constraint-induced movement therapy for upper extremity recovery post stroke: what is the evidence? Top Stroke Rehabil. 2014;21:319–31. doi: 10.1310/tsr2104-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasb M, Shah SZA, Chen H, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy combined with botulinum toxin for post-stroke spasticity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2021;13:e17645. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu P, Bai Y. Advance in mechanisms of constraint induced movement therapy on motor function rehabilitation after stroke (review) Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2015;21:913–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-9771.2015.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pin TW, Winser SJ, Chan WLS, et al. Association between fear of falling and falls following acute and chronic stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2024;56:18650. doi: 10.2340/jrm.v56.18650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang B, Han X, Pan Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of high-intensity statin on coronary microvascular dysfunction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23:370. doi: 10.1186/s12872-023-03402-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwakkel G, Winters C, van Wegen EEH, et al. Effects of unilateral upper limb training in two distinct prognostic groups early after stroke: the EXPLICIT-stroke randomized clinical trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30:804–16. doi: 10.1177/1545968315624784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin K, Wu C, Liu J, et al. Constraint-induced therapy versus dose-matched control intervention to improve motor ability, basic/extended daily functions, and quality of life in stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:160–5. doi: 10.1177/1545968308320642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasb M, Li Z, S A Youssef A, et al. Comparison of the effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy and intensive conventional therapy with a botulinum-a toxin injection on upper limb motor function recovery in patients with stroke. Libyan J Med. 2019;14:1609304. doi: 10.1080/19932820.2019.1609304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh P, Pradhan B. Study to assess the effectiveness of modified constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke subjects: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:180. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.112461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thrane G, Askim T, Stock R, et al. Efficacy of constraint-induced movement therapy in early stroke rehabilitation: a randomized controlled multisite trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29:517–25. doi: 10.1177/1545968314558599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C, Chen C, Tsai W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of modified constraint-induced movement therapy for elderly stroke survivors: changes in motor impairment, daily functioning, and quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu C, Lin K, Chen H, et al. Effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on movement kinematics and daily function in patients with stroke: a kinematic study of motor control mechanisms. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2007;21:460–6. doi: 10.1177/1545968307303411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu KPY, Balderi K, Leung TLF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of self-regulated modified constraint-induced movement therapy in sub-acute stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1351–60. doi: 10.1111/ene.13037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alaca N, Öcal NM. Proprioceptive based training or modified constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity motor functions in chronic stroke patients: A randomized controlled study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2022;51:271–82. doi: 10.3233/NRE-220009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldwin CR, Harry AJ, Power LJ, et al. Modified constraint-induced movement therapy is a feasible and potentially useful addition to the community rehabilitation tool kit after stroke: a pilot randomised control trial. Aust Occup Ther J. 2018;65:503–11. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin K-C, Wu C-Y, Wei T-H, et al. Effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on reach-to-grasp movements and functional performance after chronic stroke: a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:1075–86. doi: 10.1177/0269215507079843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smania N, Gandolfi M, Paolucci S, et al. Reduced-intensity modified constraint-induced movement therapy versus conventional therapy for upper extremity rehabilitation after stroke: a multicenter trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:1035–45. doi: 10.1177/1545968312446003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page SJ, Sisto S, Levine P, et al. Efficacy of modified constraint-induced movement therapy in chronic stroke: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:14–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu C, Wang W, Zhang Y, et al. The effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy in acute subcortical cerebral infarction. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:265. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Helow MR, Zamzam ML, Fathalla MM, et al. Efficacy of modified constraint-induced movement therapy in acute stroke. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sethy D, Bajpai P, Kujur ES, et al. Effectiveness of modified constraint induced movement therapy and bilateral arm training on upper extremity function after chronic stroke: a comparative study. OJTR. 2016;04:1–9. doi: 10.4236/ojtr.2016.41001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleim JA, Barbay S, Nudo RJ. Functional reorganization of the rat motor cortex following motor skill learning. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:3321–5. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J, Li C, Hua Y, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy improves functional recovery after ischemic stroke and its impacts on synaptic plasticity in sensorimotor cortex and hippocampus. Brain Res Bull. 2020;160:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tedla JS, Gular K, Reddy RS, et al. Effectiveness of Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) on balance and functional mobility in the stroke population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10:495. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10030495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Xiao X, Jin Q, et al. The effect and safety of constraint-induced movement therapy for post-stroke motor dysfunction: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1137320. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1137320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dromerick AW, Lang CE, Birkenmeier RL, et al. Very Early Constraint-Induced Movement during Stroke Rehabilitation (VECTORS): A single-center RCT. Neurology (ECronicon) 2009;73:195–201. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirtori V, Corbetta D, Moja L, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy for upper extremities in stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD004433. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004433.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mancini MC, Brandão MB, Dupin A, et al. How do children and caregivers perceive their experience of undergoing the CIMT protocol? Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:343–8. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2013.799227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veerbeek JM, van Wegen E, van Peppen R, et al. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Wang Y, Jin L, et al. Effects of different rehabilitation therapies on upper limb motor function and activities of daily living in stroke patients with hemiplegia: a network Meta-analysis. Chinese J Rehabilit Med. 2021;36:1138–45. [Google Scholar]