Abstract

Background

Nurses face significant challenges due to the rapid changes brought about by the emergence of increasingly complex clinical practices. Although many instruments have been validated for measuring nursing competence, they lack an updated and more comprehensive perspective. We aimed to develop and conduct psychometric testing of a comprehensive scale for measuring the self-perceived competence of professional nurses in clinical settings.

Methods

This study employed an exploratory sequential mixed methods design to develop and validate the Professional Nurses Competence Scale (PNCS) in three phases. Phase 1 (development of the PNCS) included identification domains and item generation through literature review and qualitative focus group discussions, as well as content validity assessment. Phase 2 (application of the PNCS) included examining the item quality and exploring structures of the scale with 108 registered nurses (RNs). Phase 3 (evaluation of the final PNCS version) involved confirming structures through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as well as assessing construct validity and internal consistency with 245 RNs. Twenty-two RNs were randomly selected for test-retest reliability of the final scale.

Results

During the first phase, the developed PNCS contained 68 items and tests for content validity. During the second phase, tests for homogeneity and item analysis retained 39 items, which were examined with exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The EFA produced six factors that explained 30 items. During the third phase, the six-factor structure showed an acceptable model fit in the CFA, satisfied construct validity, internal consistency and stability.

Conclusions

The PNCS was developed based on current clinical practices and perspectives. This scale could be used to assess self-perceived competence for professional nurses who require knowledge of clinical competence.

Keywords: Nursing, Professional competence, Psychometrics, Surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Nursing competence is a multifaceted concept encompassing the integration of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values necessary for nurses to perform their roles effectively. The concept of nursing competence has evolved significantly over the years, reflecting the dynamic nature of healthcare and the multifaceted role of nurses in society. The World Health Organization (WHO) [1–3] has transitioned from viewing competence as the ability to deliver specific professional services to emphasizing observable behaviors demonstrating integrated professional capacities. Similarly, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) [4] and the American Nurses Association (ANA) [5] highlight the practical application of professional knowledge and judgment in clinical practice. In alignment with these evolving definitions, nursing competence in this study is defined as the ability to integrate knowledge, skills, attitudes and judgment to perform designated roles within a given context.

Nursing competence is recognized as a complex, multidimensional construct. Traditionally, competence is associated with the integration of performance and capability [6]. Performance refers to the observable demonstration of task execution, whereas capability involves the underlying knowledge and skills enabling performance potential across diverse situations. Thus, nursing competence extends beyond mere technical skills, incorporating personality traits, professional attitudes, interpersonal communication, decision-making, and leadership [7, 8]. Competence is also viewed as both an outcome and an ongoing developmental process shaped by continuous learning and adaptation within clinical contexts [8]. Moreover, nursing competence includes behavioral attributes and task-related abilities, requiring not only the capability to perform tasks efficiently but also intrinsic motivation to effectively engage in professional duties [9, 10].

Various instruments have been developed to evaluate nursing competencies, many of which are grounded in national and international organizational guidelines and frameworks. For instance, the Nursing Competence Scale (NCS) categories proposed by Meretoja et al. [11] were adapted from Benner’s competency framework. The Competency Inventory for Registered Nurses (CIRN) aligns with the International Council of Nurses (ICN) Framework of Competencies for the Generalist Nurse, as established by Liu et al. [12]. Furthermore, several instruments were established based on national guidelines, including the Australian Nursing Competency Incorporated (ANCI) standards from 2000 [13], the Nurse Professional Competence Scale (NPC) [14] and the Clinical Nurse Performance Scale (CNPS) [15] were to reference the national organizational guidelines. In contrast, the European Quality of Nursing Care (EQT) [16], the QSEN competencies developed by Prion et al. [17] and the Appraisal of Nursing Practice (ANP) framework outlined by Becker et al. [18] were derived from international organizational guidelines. While existing nursing competence instruments have been developed based on guidelines and frameworks, there is a growing concern that these instruments may not adequately reflect the evolving nature of nursing practice in today’s dynamic healthcare environment. Furthermore, numerous studies [12, 14–17, 19, 20] employed deductive approaches in instrument development by drawing from literature reviews to identify essential competencies. Although these reviews provide important theoretical perspectives, they may inadequately capture the complexity and contextual nuances inherent in actual nursing practice. This could lead to a disconnect between the competencies defined in such instruments and the actual competencies required in clinical nursing practice.

Current scales frequently overlook emerging domains critical to contemporary nursing practice, such as evidence-based practice (EBP), information and communication technology (ICT), and legal competencies. For instance, few measurements recognize the legal or legislation domain [12, 14]. Although several measurements, such as those proposed by Prion et al. [17] and Becker et al. [18], treat EBP as an isolated domain rather than integrating it across multiple competency areas, thereby neglecting its holistic application in clinical practice. For frontline nurses, achieving better patient outcomes relies on their ability to translate new knowledge into clinical applications and implement it effectively within healthcare systems [21]. By embedding EBP competencies across relevant domains, this study to move beyond treating them in a single domain, instead promoting their holistic integration into the broader framework of nursing competence. Additionally, despite increasing reliance on ICT for synchronous communication, patient information sharing, self-management, health promotion, and education [22–26], ICT-related competencies remain inadequately represented.

Given that nursing competence directly impacts nurses’ burnout, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention [27–31], while enhancing the quality of nursing care [32], and patient safety [32, 33], it is essential to develop comprehensive, contextually relevant competence assessment tools. As healthcare systems evolve, continuous validation and adaptation of nursing competence instruments become essential to bridge existing gaps by capturing critical emerging competencies and aligning closely with actual clinical practice requirements. Developing a comprehensive, well-validated nursing competence instrument ensures nurses are skilled, confident, and prepared to respond effectively in critical situations, thereby fostering workforce stability. Moreover, the involvement of practicing nurses and clinical managers in the development process ensures that the instrument accurately reflects real-world expectations, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of training programs tailored to evolving healthcare needs. Therefore, we aimed to develop and validate a self-rated nursing competence scale for professional nurses.

Methods

Study design

This study employs an exploratory sequential mixed methods design, integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches to develop and validate the Professional Nurses Competence Scale (PNCS). In accordance with DeVellis [34] and Boateng et al. [35], the development and evaluation of the Professional Nurses Competence Scale (PNCS) were conducted in three phases: (1) PNCS development, including domain identification and item generation through literature review and qualitative focus group discussions, as well as content validity assessment; (2) PNCS application, in which we collected cross-sectional data for examining item quality and exploring factors of the initial scale’s using EFA; and (3) evaluation of the final PNCS version for psychometric testing, including confirm structure, construct validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability was conducted through a cross-sectional survey. Figure 1 illustrates the development and validation process of the Professional Nurses Competence Scale (PNCS). This study was conducted following the STROBE guidelines.

Fig. 1.

The development and validation process of the Professional Nurses Competence Scale (PNCS)

Participants and sampling

This study involved three distinct participant groups corresponding to the three research phases. In Phase 1, a focus group discussion was conducted with six registered nurses (RNs), selected through purposive sampling to ensure diversity in clinical experience and leadership roles [36]. For the quantitative phases (Phases 2 and 3), participants were recruited through convenience sampling, with inclusion criteria being full-time employment RNs in hospitals. Nurses were excluded if they worked in the operating room or outpatient department, were newly graduated RNs in their probationary period, or were head nurses, nurse supervisors, or nurse directors. In Phase 2, a cross-sectional survey was conducted to examine the quality of items and explore the factor structure of the initial PNCS using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). A minimum sample size of 200 participants is recommended for conducting EFA [37]. Considering a response rate of 70%, at least 286 RNs were selected at two tertiary care hospitals for EFA in May 2020. In Phase 3, a second cross-sectional survey was conducted to validate the final PNCS version using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and assess its psychometric properties. Between 200 and 300 participants were deemed necessary for conducting a CFA [38]. A total of 286–428 RNs were selected at a 971-bed medical center hospital, employing 800 RNs, to evaluate the final version of the PNCS. We recruited a subsample of 30 RNs from CFA participants by simple random sampling to examine test-retest reliability. Data were collected from July 2020 to September 2020.

Phase 1: PNCS development

Domain identification and item generation

To outline the core domains associated with nursing professional competencies. A literature search was conducted across four databases: PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. Additionally, a snowballing approach was used to identify relevant literature published over three decades. The search strategy was conducted following Boolean rules using the following terms: nurs*, competenc*, performance, and asses*. Besides, professional nursing portfolios from three medical centers and the two-year postgraduate training program for nurses under the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan were reviewed.

To develop the PNCS item pool, we conducted a literature review and focus group discussions. To ensure the items reflected the current competencies in nursing practice, a focus group was conducted to generate the item pool. The group comprised six RNs, including the hospital’s nursing department director (serves as a nursing professor), two nurse supervisors (one of whom also serves as a nursing assistant professor), a head nurse who is simultaneously a nursing assistant professor, and two RNs with over ten years of work experience. The focus group discussions were held weekly over six sessions, each lasting approximately one hour. A moderator facilitated the sessions by introducing the topic and employing a semi-structured interview guide. This guide was developed based on literature review and relevant documents, with each session focusing on a specific domain of nursing competence. All discussions were audio-recorded, and a trained research assistant transcribed the recordings verbatim. Qualitative data were analyzed manually following Colaizzi’s method [37]. Two researchers from the team read each transcript several times independently to attain a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences concerning particular nursing competency domains. Significant statements were coded, with meanings clustered and validated against the original transcripts. Based on the clustered meanings, preliminary item pools for nursing competency measurement were developed. Subsequently, the aggregated findings were synthesized into exhaustive descriptions and refined into clear definitions for each competency domain. Member checking was conducted by presenting the preliminary definitions and item pools to participants to verify their accuracy and relevance.

Content validity

Four experts (two vice superintendents from two hospitals, one director from the nursing department, and an associate professor in the nursing administration) evaluated the content validity of the items of the PNCS. Each expert independently rated the relevance and importance of each item using a 4-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 = irrelevant or unimportant to 4 = very relevant or important. Each item’s content validity index (CVI) was the proportion of experts who rated the item as 3 or 4 [37]. At least four experts in the field established that the items level CVI (I-CVI) should achieve a value of 1.00 [39]. We removed items with I-CVI values below 1.0.

Phase 2: PNCS application

Examining item quality

The items were analyzed using means and standard deviations (SDs), skewness and kurtosis, item‒to‒item correlations, corrected item‒total correlations, and item discrimination indices of extreme group comparisons to assess item quality [34, 40, 41]. The acceptable criteria are absolute skewness values between -2 to + 2 and absolute kurtosis values ‐7 to + 7 [40]. The item-to-item correlation values < 0.30 indicates minimal congruence with the latent variable, whereas a value > 0.70 suggests item redundancy [37]. The corrected item-total correlation value was considered satisfactory if > 0.50 [40], and any items with values < 0.30 were considered for removal [37]. We conducted an independent t-test by dividing participants into two groups based on their scores: the high-score group (top 27.0%) and the low-score group (bottom 27.0%) for each item to assess the critical ratio. The critical ratio value indicated significant differences between the two groups, which were considered satisfactory [41].

Explore structure of the initial PNCS

The structure of the initial PNCS was explored using EFA with the principal components approach and orthogonal rotation (varimax rotation) [40, 42]. The goal was to reduce items and identify latent constructs of the initial PNCS. Sampling adequacy was determined using Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.05) to assess suitability for factor analysis [40]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values > 0.60 indicated sampling adequacy [43]. Eigenvalues > 1.0 and scree plot were used for factor analysis. For the EFA sample size ranging from 100 to 120, a significant factor loading value of at least 0.50 [40], and variable communalities with an average value between 0.5 and 0.6 are acceptable [44]. Items were eliminated if cross-loading occurred, with the ratio of loadings between factors exceeding 75% [42, 45].

Phase 3: Evaluation of the final PNCS version

Validity

CFA was conducted to confirm the structural validity of the final PNCS. Normality was assessed by examining each item’s skewness and kurtosis. Maximum likelihood with structural equation modeling was used for parameter estimations. The suggested lambda (λ) cutoff value in the CFA was 0.50 [40]. Chi-square test (χ2), χ2/degrees of freedom (df), and the χ2/df value between 2 and 5, with a goodness-of-fit index (GFI) value > 0.80, was considered acceptable [46]. Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values < 0.08 were considered acceptable [47, 48]. Comparative fit index (CFI) and non-normed fit index (NNFI) values ≥ 0.90 denoted a model of good fit.

Regarding construct validity, we evaluated convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was assessed by examining the average variance extracted (AVE), with values greater than 0.50 indicating satisfactory convergence [40]. A composite reliability value of ≥ 0.70 was considered acceptable for evaluating the consistency of the latent variable set [40]. Discriminant validity was established when the square root of the AVE was greater than the inter-construct correlations [40]. Since this is a comprehensive scale that includes domains of professional nurse competence not previously examined, concurrent validity with another scale has not been determined.

Reliability

The internal consistency and stability of the self-developed instrument were evaluated using a scale. A Cronbach’s α value ≥ 0.80 indicated good internal consistency reliability [37]. For stability assessment, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was utilized to calculate the test-retest reliability at two weeks with a subsample of nurses. An ICC value was considered to indicate satisfactory stability if > 0.40 [49].

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Yang-Ming University (YM108004E) and the Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (IRB 108-94-B). A member of the research team explained the study’s design, purpose, and participants’ rights to the RNs who met the inclusion criteria. Nurses who agreed to participate provided written informed consent before data collection and were assured of the anonymity of their data. The same researcher was also tasked with overseeing the distribution and retrieval of the questionnaires. Each participant received an unmarked, sealed envelope containing a questionnaire coded with a randomly assigned number unlinked to any personally identifiable information. They completed the questionnaires independently, resealed them, and deposited them into a designated collection box. All analyses were conducted using only coded questionnaires.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software (version 21.0) and LISREL 8.8 Software (SSI International, Inc.). Descriptive statistics included the mean, SD, frequencies and percent (%). Item analysis included Pearson’s correlation coefficient, independent t test and EFA. LISREL 8.8 Software (SSI International, Inc.) was used for CFA.

Results

Phase 1: PNCS development

Domain identification and item generation

The initial literature search identified 636 articles; 25 were retained after screening. These articles highlighted multiple domains, such as clinical care, professional development, communication, teaching, coaching, collaboration, teamwork, management, leadership, ethical practices, legal considerations, safety, quality, information technology, and evidence-based practice (EBP) [11–20, 50]. After merging overlapping concepts, six core domains were established for the PNCS: Clinical Care, Ethical and Legal Practices, Effective Communication and Collaboration, Leadership and Management, Teaching and Coaching, and Professional Development. The initial item pool was developed through a literature review and focus group discussions. After removing redundant or repetitive items, a total of 35 items were referenced from the existing literature [11–20, 50–52], and an additional 31 items were generated through focus group discussions, resulting in 66 item statements. Therefore, the PNCS comprises 66 items covering six domains. Self-perceived competency was assessed with a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not competent at all) to 5 (very competent), with higher scores indicating greater levels of nursing professional competence.

Content validity

Three items were eliminated due to I-CVI value below 1.0 [39]. However, it was suggested that one double-barrel item sperate two single items: one for ethical and legal practice and one for leadership and management, resulting in 65 items for the six domains. Item wording was also refined based on expert suggestions.

Phase 2: PNCS application

Initially, we planned to invite 300 registered nurses (RNs) from two hospitals to participate in phase 2. However, due to the COVID-19 epidemic and resulting visitor restrictions, we were unable to recruit participants from one of the hospitals. Therefore, data were obtained from 108 RNs at one of two hospitals, and after excluding the invalid questionnaires, the response rate was 71.1% (n = 152). Most participants were single women, and over half had an associate degree. The mean age was 28.24 years (SD = 6.56), and the mean length of work experience was 6.78 years (SD = 6.58). With respect to the clinical ladder level, half of the participants were in the level I stage, followed by the level II stage. Nearly two-thirds of the participants worked in surgical or medical wards (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the registered nurses who participated in the phases 2 and 3

| Characteristic | Phase 2 (N = 108) | Phase 3 (N = 245) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean | SD | n (%) | Mean | SD | |

| Age, y | 28.24 | 6.56 | 28.49 | 6.83 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 5 (4.6) | 10 (4.1) | ||||

| Women | 103(95.4) | 235 (95.9) | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 91 (84.3) | 186 (75.9) | ||||

| Married | 17 (15.7) | 59 (24.1) | ||||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Associate degree | 58 (53.7) | 110 (44.9) | ||||

| ≥ Bachelor’s degree | 50 (46.3) | 135 (55.1) | ||||

| Clinical ladder level | ||||||

| level I | 55 (50.9) | 113 (46.1) | ||||

| level II | 38 (35.2) | 94 (38.4) | ||||

| level III | 8 (7.4) | 27 (11.0) | ||||

| level IV | 7 (6.5) | 11 (4.5) | ||||

| Length of work experience, y | 6.78 | 6.58 | 6.97 | 6.49 | ||

| Type of clinical care | ||||||

| Surgical wards | 41(38.0) | 80(32.7) | ||||

| Medical wards | 31 (28.7) | 63 (25.7) | ||||

| Intensive care unit | 19 (17.6) | 48 (19.6) | ||||

| Pediatric wards | 9 (8.3) | 22 (8.9) | ||||

| Emergency room | 5 (4.6) | 19 (7.8) | ||||

| OB-GYN wards | 2 (1.9) | 6 (2.4) | ||||

| Psychiatric wards | 1 (0.9) | 7 (2.9) | ||||

Examining item quality

Sixty-five items were analyzed for the six domains of the initial version of the PNCS: Clinical Care (10 items); Ethical and Legal Practice (12 items); Effective Communication and Collaboration (10 items); Leadership and Management (13 items); Teaching and Coaching (10 items); and Professional Development (10 items).

The means for PNCS items ranged from 2.59 to 4.56 (SD ranged from 0.51 to 1.17). Both skewness (–1.12 to − 0.24) and kurtosis (–0.96 to 5.21) fell within acceptable ranges. Eight items were excluded because they had item-to-total correlation coefficients < 0.30 and failed to meet the critical ratio value. Examining item‒to-item correlations resulted in the deletion of 18 items because Pearson’s coefficient was > 0.70. The homogeneity of the 39-item PNCS showed item‒total correlation coefficients ranging from 0.37 to 0.78; all items revealed a significant relationship (p < 0.001), indicating that the degree of homogeneity was good. Thus, 39 items were retained.

Explore structure of the initial PNCS

The factors of initial 39-item PNCS was determined using EFA. The KMO value was 0.87, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 3094.98, p < 0.001) indicated that the sampling adequacy was good and that the scale was a candidate for factor analysis. The EFA results indicated 8 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, while the scree plot suggested a 4 or 6-factor solution. Based on the conceptual framework of the PNCS, the number of factors was fixed at six. Following the EFA, nine items were excluded: three items had factor loadings below 0.50, and six items exhibited cross-loadings. For the remaining 30 items of the PNCS, factor loadings ranged from 0.50 to 0.88, with communalities ranging from 0.54 to 0.82. Collectively, the six factors accounted for 72.44% of the total variance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis for items included in the 30-item PNCS (N = 108)

| Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Factor 1: Professional Development (PD) | |||||||

| PD60 | I proactively participate and communicate with nurses internationally. | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.01 | -0.03 | 0.04 |

| PD59 | I participate in the development of professional nursing organizations. | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| PD57 | I apply the results of nursing research or project to nursing practice. | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.10 | -0.02 |

| PD54 | I identify problems as material for research, evidence-based practice, or projects. | 0.86 | -0.05 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| PD58 | I evaluate self-efficacy and promote personal professional development. | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.38 |

| TC471 | I am a teacher for employee education training. | 0.57 | 0.29 | -0.08 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Factor 2: Clinical Care (CC) | |||||||

| CC07 | I determine sudden changes in a patient’s condition and provide appropriate care. | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| CC03 | I set priorities of nursing care according to the urgency of the patient’s needs. | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| CC09 | I independently provide total care for critical patients. | 0.15 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.16 | -0.08 |

| CC02 | I establish a patient’s health problems with critical thinking. | 0.08 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.19 |

| CC06 | I perform nursing techniques correctly. | -0.14 | 0.69 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| CC05 | I provide care for patients that includes examination, treatment, and follow-up. | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.36 |

| Factor 3: Ethical Nursing Practice (EP) | |||||||

| EP20 | I am respectful of a patient’s values. | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| EP21 | I am respectful of a patient’s faith. | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.11 | -0.05 |

| EP17 | I pay attention to patient concerns and maintain patient privacy. | -0.01 | 0.22 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| EP19 | I consider the most beneficial treatment when providing patient care. | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.37 |

| EP16 | I am respectful of a patient’s autonomy when providing care. | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.38 |

| Cs242 | I communicate effectively on issues of concern to the patient. | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.13 |

| Factor 4: Leadership and Management (LM) | |||||||

| LM41 | I manage wards and sterile consumables based on administrative rules. | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| LM37 | I maintain patient safety by managing optimal nurse-patient ratios. | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.69 | 0.22 | -0.01 |

| LM40 | I solve problems by applying management knowledge and skills. | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 0.35 |

| LM39 | I manage time well. | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| LM38 | I ensure patient safety by detecting risk factors in the ward environments. | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.19 |

| Factor 5: Effective Communications and Collaborations (Cs) | |||||||

| Cs26 | I use information technology for interprofessional communication platforms. | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.82 | 0.16 |

| Cs30 | I use interprofessional communication platforms to solve patient problems. | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.76 | 0.13 |

| Cs28 | I provide resource and referral services according to the patient’s needs. | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.74 | 0.13 |

| Cs31 | I communicate and cooperated with the hospital administration. | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.11 |

| Factor 6: Legal Nursing Practice (LP) | |||||||

| LP14 | I identify illegal or non-professional behaviors and take effective actions. | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.73 |

| LP12 | I perform nursing practices according to laws and regulations of nursing. | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.71 |

| LP15 | I act as an advocate for patient rights. | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.50 |

| Eigenvalue | 11.84 | 3.68 | 2.26 | 1.57 | 1.31 | 0.98 | |

| Percent variance explained(%) | 15.35 | 14.71 | 14.03 | 10.24 | 9.62 | 8.49 | |

| Total variance explained (%) = 72.44 | |||||||

Note. 1 Originally in domain of Teaching and Coaching, 2Originally in domain of Effective communication and collaboration

The final six factors comprised 30 items. Professional Development (6 items) was defined as a nurse’s ability to facilitate self-improvement through continuing education, participation in research and EBP, teaching and joining professional organizations. Clinical Care (6 items) was defined as nurses providing appropriate clinical care to patients based on critical thinking. Ethical Nursing Practice (6 items) was defined as the ability of nurses to deliver healthcare and communicate in a manner grounded in ethical principles. Leadership and Management (5 items) was defined as the ability of a nurse to lead in a manner that effectively improved healthcare quality. Effective Communication and Collaboration (4 items) was defined as nurses being able to use ICT to communicate and collaborate effectively with patients and families, team members, and interdepartmental staff. Legal Nursing Practice (3 items) was defined as nurses following the established laws and regulations of nursing practice.

Phase 3: Evaluation of the final PNCS version

The data collected from 245 RNs were used to validate the structure of final PNCS using CFA. Valid questionnaires were collected from 245 participants; the response rate was 57.2% (n = 428). Most participants were single women, with over 50% possessing a bachelor’s degree. The ages ranged from 20 to 52 years (mean, 28.49; SD, 6.83). The length of work experience ranged from 0.75 to 30 years (mean, 6.97; SD, 6.49). Nearly half of the participants were in the level I stage of the clinical ladder, followed by the level II stage. Nearly 80.0% of the patients were involved in surgical or medical wards or intensive care units (Table 1).

Descriptive statistics

The mean item scores for the PNCS ranged from 2.62 to 4.48 (SD ranged from 0.57 to 1.05). Additionally, eight items had more than 20% of respondents selecting the highest rating (5 = very competent).

Validity

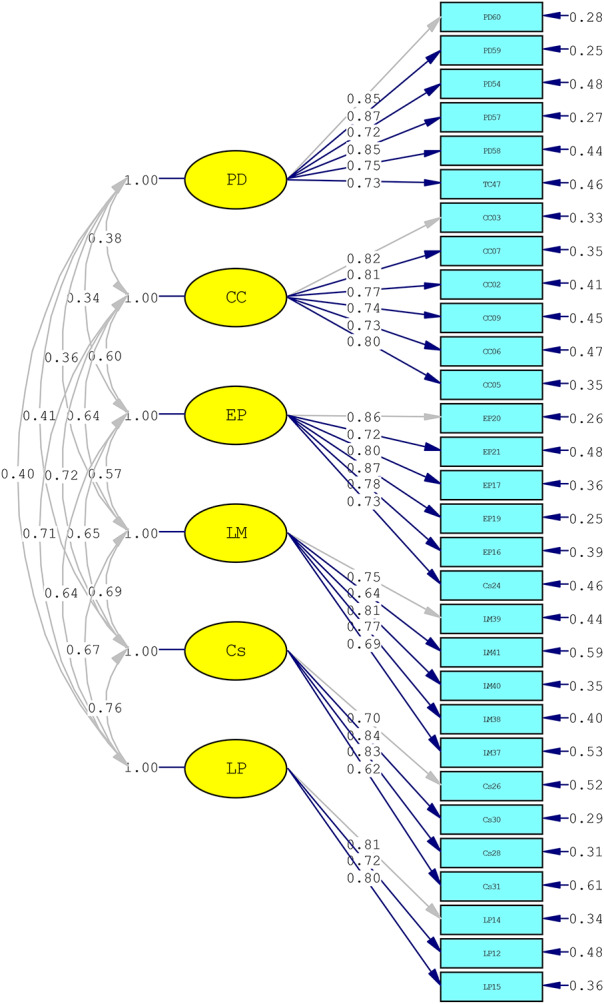

The final 30-item PNCS was analyzed with CFA to verify the relationships between the 30 items and any underlying latent factors of the scale. Skewness ranged from − 0.71 to − 0.01, and kurtosis ranged from − 0.94 to 1.25, indicating satisfaction with the normality test. CFA resulted in lambda (λ) ranging from 0.62 to 0.87, indicating that the observed measures reflected the latent construct of professional nurse competence. The fit indices for the six-structure model were χ2/df = 2.27; CFI = 0.96; NNFI = 0.97; GFI = 0.80; RMSEA = 0.072 (90% confidence interval: 0.066 to 0.078); and SRMR = 0.075, indicating the six-factor model of the PNCS demonstrated an acceptable goodness of fit. Figure 2 illustrates the final model.

Fig. 2.

A CFA model for the final 30-item, six-factor structure of the PNCS

Additionally, among the six factors, the AVE ranged from 0.54 to 0.64, and the composite reliability ranged from 0.82 to 0.91, indicating good convergent validity. The square root of the AVE exceeded the inter-construct correlations, confirming satisfactory discriminant validity. Details are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Convergent and discriminant validity of the final 30-item PNCS (N = 245)

| Factors | Convergent validity | Discriminant validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | Factor 1 | Factor2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | |

| Factor 1 | 0.91 | 0.64 | 0.80 | |||||

| Factor 2 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.35** | 0.78 | ||||

| Factor 3 | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.21** | 0.53** | 0.80 | |||

| Factor 4 | 0.85 | 0.54 | 0.47** | 0.56** | 0.49** | 0.73 | ||

| Factor 5 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.48** | 0.62** | 0.61** | 0.62** | 0.75 | |

| Factor 6 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.35** | 0.65** | 0.55** | 0.56** | 0.62** | 0.78 |

Note. AVE values are presented in the diagonal (bolded)

**p < 0.01

Reliability

The reliability of the final 30-item PNCS was determined using Cronbach’s α for the total scale, which was 0.94 (range = 0.81–0.91) for the six factors, indicating relatively high internal consistency (Table 3). To evaluate stability, test-retest scores from 22 RNs were analyzed, revealing an ICC of 0.67 for the total scale, indicating a significant correlation between the pre- and post-test scores (p < 0.01) and demonstrating good stability.

Discussion

Using an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design, we developed and validated a comprehensive instrument to assess nurses’ self-perceived professional competence by integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches. The newly developed 30-item PNCS, comprising six domains (Professional Development, Clinical Care, Ethical Nursing Practice, Leadership and Management, Effective Communication and Collaboration, and Legal Nursing Practice), had satisfactory validity and reliability. EFA revealed that the six domains explained 72.44% of the total variance. PCA with orthogonal rotation was chosen to maximize variance summarization with fewer components, as it is widely used and particularly suitable for data reduction while preserving component independence. Although the eigenvalue of the Legal Nursing Practice domain was slightly below 1.0, it was retained as it aligned with the conceptual framework, with factor loadings ranging from 0.50 to 0.73. The CFA confirmed the structural validity of the final 30-item, six-domain PNCS, demonstrating an acceptable model fit. The PNCS demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, construct validity and two-week test-retest stability. In the scale, eight items exhibited a potential ceiling effect, with more than 20% of respondents selecting the highest rating (5 = very competent) [53]. Among these, six items belonged to the ethics domain, while two items (CC03 and CC06) were related to clinical care domain. This phenomenon may be attributed to social desirability response bias or extreme response tendencies [37], where participants may have been inclined to present themselves in a more favorable light or select extreme ratings when assessing their own competence. Alternatively, this could be due to the strong emphasis on these competencies in nursing education, leading to a high level of proficiency among participants.

The Clinical Care domain, consistent with other nursing competence instruments [12, 14, 16, 19, 20, 50], emphasizes the fundamental competencies required for delivering optimal patient care. The deletion of two EBP items from the Clinical Care and Leadership and Management domains during the EFA process underscores the challenges in adequately capturing EBP related competencies. In Taiwan, the nursing clinical ladder program, established by the Taiwan Nurse Association, consists of four levels (N1 to N4) and is widely implemented across hospitals. Advancement to N3 requires the publication of a systematic review, while progression to N4 necessitates the submission of an EBP implementation paper. As a result, nurses in Taiwan receive EBP training as part of their professional development when advancing through the clinical ladder. This may explain the elimination of two of items related to applying EBP to develop care plans and evaluate nursing care quality outcomes. To address this gap, it is essential not only to embed EBP competencies into job roles, clinical ladders, and organizational systems to elevate care standards [54–56] but also to integrate EBP training into nursing school curricula to equip new graduate nurses with foundational EBP skills. Additionally, revising the clinical ladder program to incorporate EBP competency requirements starting at the N1 level would ensure a more consistent development of these critical skills throughout a nurse’s competence.

The separation of the initial Ethical and Legal Practices domain into two individual domains after EFA, confirmed by CFA, highlights a nuanced understanding of nursing practice. Our findings differ from those reported in instruments [12–16], which either focused solely on ethics or merged ethics and legal aspects into a single dimension. Ethics refer to a set of moral principles and values guiding behavior within an internal system, while legal considerations are based on structured rules and regulations enforced by external mechanisms [57]. In the Legal Nursing Practice domain, the PNCS captured competencies related to identifying illegal or non-professional behaviors. Legal issues, such as substance abuse, medication theft, diminished work performance, and neglect of nursing guidelines, pose threats to healthcare system and patient safety and require RNs to act through the detection and management of legal problems to uphold standards of care [58]. This suggests that Ethical Nursing Practice differ from Legal Nursing Practice in both understanding and application. Therefore, nursing school curriculum and hospital training programs should emphasize and strengthen nurses’ ability to clarify, understand and apply ethical and legal principles. Moreover, the reclassification of Cs24 from the domain of Effective Communication and Collaboration to Ethical Nursing Practice after EFA, aligns with the findings of Takase & Teraoka [20] and emphasizing the central role of communication in ethical nursing. This integration underscores how communication is fundamental to upholding ethical standards in nursing [59, 60].

Regarding Effective Communication and Collaboration, while most previous studies focus solely on communication skills [12, 13, 20], this study highlights the use of information technology communication platforms to address patient concerns and facilitate real-time interactions. These platforms enhance nurses’ ability to engage promptly and effectively with patients and colleagues while also enabling them to provide resource and referral services based on patients’ needs.

In the Leadership and Management domain, other studies have focused on participation in management practices, delegation, and identifying risk factors [11–13, 20]. This study takes a different approach. It emphasizes key competencies in nurse-patient ratio awareness, time management, ward and consumables management. This approach is crucial for meeting the current demands of leadership and management competencies.

In the Professional Development domain, the item related to EBP was similarly included in the Professional Development domains of instruments developed by Cowan et al. [16] and Nilsson et al. [14]. Additionally, the ability to evaluate self-efficacy, promote personal professional development and communicate with international nursing organizations constitutes key aspects of nurses’ professional growth. This role marks professional growth, as RNs progress into educators by training novice and senior nurses through orientation and preceptor programs, teaching clinical skills, and delivering lectures. The integration of teaching, coaching, and self-efficacy evaluation into the professional development domain underscores the dynamic nature of nursing practice, ultimately enhancing the competence and confidence of nursing professionals.

Our study revealed that the final version of the PNCS removed items related to patient and family education, which contrasts with the findings of previous studies [11, 12, 14, 20, 50]. These educational items may be integrated into the domains of clinical care and effective communication and collaboration. This approach is supported by Takase & Teraoka [20], who found that patient and family education items are integral to the nursing care domain. This can be explained by the fact that effective verbal patient and family education depends on the communication approach and content between patients and healthcare providers [61]. Moreover, nurses use ICT to communicate with and educate patients, families, and caregivers during the educational process. This allows RNs to provide health information more easily and conveniently and enables patients, families, and caregivers to access it more easily, helping patients understand their health condition and how to manage it [62]. This new perspective suggests that clinical care tailored to each patient’s needs and effective communication between nurses, patients, and their families inherently involve educational elements, making a separate category for patient education unnecessary. However, this integration highlights the importance of focusing on patient education within the clinical care and communication domains in future research.

The PNCS distinguishes itself from previous nursing competence scales by separating Ethical and Legal practices into distinct domains, integrating patient education into clinical care and effective communication and collaboration via ICT and incorporating teaching into professional development. This approach could be to provide a current framework for assessing key aspects of nursing competence.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, despite the results indicating satisfaction with the EFA indices, the sample size (108 participants) may need to be increased for EFA. The scale was tested in phase 3 with RNs from only one hospital, which prevents our findings from being generalized to other RNs in Taiwan. Future studies should aim to recruit more than 200 subjects for EFA [37] and be conducted in diverse geographical areas. Self-reporting bias is another potential limitation of the study. We also had no quantitative assessments of competence that could be compared with the nurses’ self-perceived levels. We suggest that future studies compare the competency assessments of RNs based on evaluations by nurse supervisors with the total scale score, which might strengthen our study findings. We also recommend that future studies examine PNCS scores for nurses in other countries for transcultural comparisons.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that the instrument has undergone psychometric testing for measuring self-perceived competency in RNs. The newly developed 30-item PNCS instrument could be helpful for assessing the level of competency in the six domains in today’s complex healthcare system. The instrument has the potential to inform modifications in nursing curricula and support targeted interventions to enhance nurse competency.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all of the nurses who participated in our research.

Abbreviations

- EBP

Evidence-based practice

- ICT

Information and communication technology

- CFA

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- EFA

Exploratory factor analysis

- PNCS

Professional Nurses Competence Scale

- CC

Clinical Care

- Cs

Effective communication and collaboration

- EP

Ethical Nursing Practice

- LM

Leadership and Management

- LP

Legal Nursing Practice

- PD

Professional Development

- OB-GYN

Obstetrics and Gynecology

- SD

Standard deviation

- SE

Standard error

- CVI

Content validity index

- KMO

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- GFI

Goodness-of-fit index

- SRMR

Standardized root mean square residual

- RMSEA

Root mean square error of approximation

- CFI

Comparative fit index

- NNFI

Non-normed fit index

- AVE

Average variance extracted

- CR

Composite reliability

Author contributions

SY and JYC designed the study. TYT contributed to participant recruitment and questionnaire administration. JYC contributed to data collection and data management. JYC and SY analyzed and interpreted the data. JYC was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. JYC, SY, HYL and HDD participated in revising the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China (Taiwan) (MOST 106-2629-B-010-002-).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current survey research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Yang-Ming University (YM108004E) and the Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (IRB 108-94-B). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Nurses willing to participate provided signed informed consent before data collection. Participants were assured that all responses would remain confidential and that data would be analyzed anonymously.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO. Competency in Nursing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2003. [http://www.who.int/publications]. Accessed 26 August 2023.

- 2.WHO. Global standards for the initial education of professional nurses and midwives. World Health Organization. 2009. [http://www.who.int/publications]. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- 3.WHO. Global Competency and Outcomes Framework for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2022;20241220. [https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034662]. Accessed 22 August 2024.

- 4.ICN. Nursing Care Continuum Framework and Competencies: International Council of Nurses. 2008. [https://sigafsia.ch/files/user_upload/07_ICN_Nursing_Care_Continuum_Framework_and_Competencies.pdf]. Accessed 25 November 2023.

- 5.ANA, Nursing. Scope and Standards of Practice: American Nurses Association; 2015. [http://www.Nursingworld.org]. Accessed 24 August 2023.

- 6.Garside JR, Nhemachena JZ. A concept analysis of competence and its transition in nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(5):541–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukada M. Nursing competency: definition, structure and development. Yonago Acta Med. 2018;61(1):001–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Aungsuroch Y. Current literature review of registered nurses’ competency in the global community. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2018;50(2):191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mrayyan MT, Abunab HY, Khait AA, Rababa MJ, Al-Rawashdeh S, Algunmeeyn A, Saraya AA. Competency in nursing practice: a concept analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e067352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nabizadeh-Gharghozar Z, Alavi NM, Ajorpaz NM. Clinical competence in nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;97:104728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meretoja R, Isoaho H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurse competence scale: development and psychometric testing. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(2):124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu M, Kunaiktikul W, Senaratana W, Tonmukayakul O, Eriksen L. Development of competency inventory for registered nurses in the People’s Republic of China: scale development. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(5):805–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrew S, Gregory L, Cowin LS, Eagar SC, Hengstberger-Sims C, Rolley J. Psychometric properties of the Australian nurse competency 2000 standards. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(10):1512–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsson J, Johansson E, Egmar A-C, Florin J, Leksell J, Lepp M, et al. Development and validation of a new tool measuring nurses self-reported professional competence—The nurse professional competence (NPC) scale. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(4):574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahya E, Oral N. Measurement of clinical nurse performance: developing a tool including contextual items. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2018;8(6):112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowan DT, Wilson-Barnett DJ, Norman IJ, Murrells T. Measuring nursing competence: development of a self-assessment tool for general nurses across Europe. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(6):902–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prion S, Berman A, Karshmer J, Van P, Wallace J, West N. Preceptor and self-evaluation competencies among new RN graduates. J Continuing Educ Nurs. 2015;46(7):303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker H, Meraviglia M, Seo JE, Ndlovu C, Kimmel L, Rowin T. The appraisal of nursing practice: instrument development and initial testing. JONA: J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko Y, Yu S. Core nursing competency assessment tool for graduates of outcome-based nursing education in South Korea: A validation study. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2019;16(2):155–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takase M, Teraoka S. Development of the holistic nursing competence scale. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(4):396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens K. The impact of evidence-based practice in nursing and the next big ideas. Online J Issues Nurs. 2013;18(2):4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen KR, Hazelett SE, Radwany S, Ertle D, Fosnight SM, Moore PS. The promoting effective advance care for elders (PEACE) randomized pilot study: theoretical framework and study design. Popul Health Manage. 2012;15(2):71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank LL, McCarthy MS. Telehealth coaching: impact on dietary and physical activity contributions to bone health during a military deployment. Mil Med. 2016;181(suppl5):191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marek KD, Stetzer F, Ryan PA, Bub LD, Adams SJ, Schlidt A, et al. Nurse care coordination and technology effects on health status of frail older adults via enhanced self-management of medication: randomized clinical trial to test efficacy. Nurs Res. 2013;62(4):269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinto ACS, Scopacasa LF, Bezerra LLAL, Pedrosa JV, Pinheiro PNC. Use of information and communication technologies in health education for adolescents: integrative review. Rev enferm UFPE on line. 2017:634–44.

- 26.Porath A, Irony A, Borobick AS, Nasser S, Malachi A, Fund N, Kaufman G. Maccabi proactive Telecare center for chronic conditions–the care of frail elderly patients. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017;6:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H-Y, Chao C-Y, Kain VJ, Sung S-C. The relationship of personal competencies, social adaptation, and job adaptation on job satisfaction. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;83:104199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Numminen O, Leino-Kilpi H, Isoaho H, Meretoja R. Newly graduated nurses’ occupational commitment and its associations with professional competence and work‐related factors. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(1–2):117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takase M, Teraoka S, Kousuke Y. Investigating the adequacy of the Competence-Turnover intention model: how does nursing competence affect nurses’ turnover intention? J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(5–6):805–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO. The Global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016–2020: World Health Organization. 2016. [https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241510455]. Accessed 24 August 2023.

- 31.Choi H, Shin S. The factors that affect turnover intention according to clinical experience: a focus on organizational justice and nursing core competency. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halabi JO, Nilsson J, Lepp M. Professional competence among registered nurses working in hospitals in Saudi Arabia and their experiences of quality of nursing care and patient safety. J Transcult Nurs. 2021;32(4):425–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalsoom Z, Victor G, Virtanen H, Sultana N. What really matters for patient safety: correlation of nurse competence with international patient safety goals. J Patient Saf Risk Manage. 2023;28(3):108–15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. Fourth ed: Sage; 2017. pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quiñonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Côté-Arsenault D, Morrison-Beedy D. Practical advice for planning and conducting focus groups. Nurs Res. 1999;48(5):280–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017. pp. 308–42. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th ed. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2016. xvii, 534-xvii. pp. 76–77, 271.

- 39.Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. Volume 102–125, 7th ed. ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010. pp. 686–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelley TL. The selection of upper and lower groups for the validation of test items. J Educ Psychol. 1939;30(1):17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.SPSS. What is The Exploratory Factor Analysis? [cited 2024 20 December]. [https://www.onlinespss.com/how-to-run-exploratory-factor-analysis-in-spss/]. Accessed 20 December 2024.

- 43.Kaiser HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974;39(1):31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(1):84. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samuels P. Advice on exploratory factor analysis. 2017.

- 46.Doll WJ, Xia W, Torkzadeh G. A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Q. 1994:453–61.

- 47.Lt H, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDonald RP, Ho M-HR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwirian PM. Evaluating the performance of nurses: a multidimensional approach. Nurs Res. 1978;27(6):347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Booth M, Courtnell T. Developing competencies and training to enable senior nurses to take on full responsibility for DNACPR processes. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2012;18(4):189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen S-H, Chen M-F, Kuo M-L, Li Y-H, Chiang M-C. Predictor of self-perceived nursing competency among new nurses in Taiwan. J Continuing Educ Nurs. 2017;48(3):129–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van der Putten J, Hobart JC, Freeman J, Thompson AJ. Measuring change in disability after inpatient rehabilitation: comparison of the responsiveness of the Barthel index and the functional independence measure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(4):480–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Gallagher-Ford L, Kaplan L. The state of evidence-based practice in US nurses: critical implications for nurse leaders and educators. JONA: J Nurs Adm. 2012;42(9):410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melnyk BM, Gallagher-Ford L, Thomas BK, Troseth M, Wyngarden K, Szalacha L. A study of chief nurse executives indicates low prioritization of evidence‐based practice and shortcomings in hospital performance metrics across the united States. Worldviews Evidence‐Based Nurs. 2016;13(1):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ubbink DT, Guyatt GH, Vermeulen H. Framework of policy recommendations for implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gundugurti PR, Bhattacharyya R, Kondepi S, Chakraborty K, Mukherjee A. Ethics and law. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64(Suppl 1):S7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papinaho O, Häggman-Laitila A, Kangasniemi M. Unprofessional conduct by nurses: A document analysis of disciplinary decisions. Nurs Ethics. 2022;29(1):131–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boykins A. Core communication competencies in patient-centered care. ABNF Journal: Official J Association Black Nurs Fac High Educ Inc. 2014;25(2):40–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heck LO, Carrara BS, Mendes IAC, Arena Ventura CA. Nursing and advocacy in health: an integrative review. Nurs Ethics. 2022;29(4):1014–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marcus C. Strategies for improving the quality of verbal patient and family education: a review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Psychol Behav Medicine: Open Access J. 2014;2(1):482–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujino Y, Kawamoto R. Effect of information and communication technology on nursing performance. CIN: Computers Inf Nurs. 2013;31(5):244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current survey research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.