Abstract

Extracellular microRNAs (miRNAs) represent a promising new source of toxicity biomarkers that are sensitive indicators of site of tissue injury. In order to establish reliable approaches for use in biomarker validation studies, the HESI technical committee on genomics initiated a multi-site study to assess sources of variance associated with quantitating levels of cardiac injury induced miRNAs in biofluids using RT-qPCR. Samples were generated at a central site using a model of acute cardiac injury induced in male Wistar rats by 0.5 mg/kg isoproterenol. Biofluid samples were sent to 11 sites for measurement of 3 cardiac enriched miRNAs (miR-1-3p, miR-208a-3p, and miR-499-5p) and 1 miRNA abundant in blood (miR-16-5p) or urine (miR-192-5p) by absolute quantification using calibration curves of synthetic miRNAs. The samples included serum and plasma prepared from blood collected at 4 h, urine collected from 6 to 24 h, and plasma prepared from blood collected at 24 h post subcutaneous injection. A 3 parameter logistic model was utilized to fit the calibration curve data and estimate levels of miRNAs in biofluid samples by inverse prediction. Most sites observed increased circulating levels of miR-1-3p and miR-208a-3p at 4 and 24 h after isoproterenol treatment, with no difference seen between serum and plasma. The biological differences in miRNA levels and sample type dominated as sources of variance, along with outlying performance by a few sites. The standard protocol established in this study was successfully implemented across multiple sites and provides a benchmark method for further improvements in quantitative assays for circulating miRNAs.

Keywords: interlaboratory, microRNA, variance, biomarker

Currently available safety biomarkers have limited sensitivity and specificity to detect damage to tissues, and additional biomarkers are needed to augment or supplant the current repertoire. Due to their presence in biofluids and other characteristics described below, microRNAs (miRNAs) have recently emerged as biomarker candidates (Etheridge et al., 2011; Saikumar et al., 2014). MiRNAs are non-coding, small (19–25 nucleotides) RNAs that play important roles in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression within a cellular context, and thereby influence major cellular, physiological and pathological processes (Krol et al., 2010; Hermeking, 2012). Most relevant for biomarker research, miRNAs were found to be quite stable in biofluids (Mitchell et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2011), are measurable with widely used methods like reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), and, as they are well conserved across species, have promising translational properties (Saikumar et al., 2014). Furthermore, several miRNAs were found to be expressed in a tissue specific or tissue-enriched manner, e.g. miR-122 in liver (Filipowicz and Grosshans, 2011), miR-192 in kidney cortex (Tian et al., 2008) and liver (Minami et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2009), and miR-208 in heart (Ji et al., 2009). Importantly, such miRNAs were increased in plasma with the occurrence of liver and heart injury in animal models (Glineur et al., 2016; Sharapova et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2009) and in patients (Akat et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2014). They have also been observed at elevated levels in urine upon kidney injury (Kanki et al., 2014; Pavkovic et al., 2014). In summary, miRNAs appear to possess several beneficial characteristics that suggest they have potential as easily accessible biomarkers for safety assessment.

There is increasing appreciation that multiple pre-analytical and technical factors can challenge the measurement of miRNAs in biofluids (Jarry et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2011). Although serum or plasma are sources of circulating miRNAs, blood processing methods can introduce variability due to multiple factors. The anticoagulant used to prepare plasma can have a strong effect on qPCR efficiency, with heparin being inhibitory compared to EDTA (Kim et al., 2012). Furthermore, the coagulation process may induce release of miRNAs from white blood cells or platelets, both of which contain an abundance of miRNA, which may lead to differences in miRNA profiles between plasma and serum (Cheng et al., 2013; McDonald et al., 2012). Therefore, we analyzed the comparability of measurements of circulating levels of injury-induced miRNAs in plasma versus serum.

The low miRNA content in biofluids represents particular challenges for quantification, including both measurement technologies and normalization strategies (Pritchard et al., 2012). No consensus exists within the research community on which endogenous miRNAs present in biofluids to use as normalization controls. Various approaches that have been used include global mean approaches, normalization to small RNAs characterized as invariant within a given sample set, or normalization to synthetic spike-in control miRNA (Pritchard et al., 2012). Absolute quantification using RT-qPCR and calibration curves of synthetic miRNA may overcome some of the issues associated with relative quantification and other approaches (Kroh et al., 2010). However, absolute quantification protocols are not currently widely used for miRNA.

The Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) Application of Genomics to Mechanism-Based Risk Assessment Committee conducted a series of studies to assess whether current practice for measuring miRNAs in biofluids is “fit-for-purpose” for use in evaluations of miRNA as safety biomarkers, which generally involve a body of supporting evidence from multiple sources. The studies compared absolute measurements of miRNA in serum, plasma, and urine across multiple sites using a standard protocol. The targets included 3 miRNAs (miR-1-3p, miR-208a-3p, and miR-499-5p) that are enriched in myocardium across species (Vacchi-Suzzi et al., 2013) and are potential extracellular biomarkers of acute cardiac injury in biofluids (Adachi et al., 2010; D’Alessandra et al., 2010; Devaux et al., 2012; Glineur et al., 2016; Ji et al., 2009), an endogenous reference miRNA (miR-16-5p in plasma and serum in Phase 2 and miR-192-5p in plasma and urine in Phase 3) that is expected to be easily detected in biofluids but is relatively unchanged by drug treatment, and an exogenous spike-in miRNA. Samples were generated using a model of isoproterenol-induced cardiac injury in male Wistar rats and pooled to generate sufficient amounts of the same samples for analysis at multiple test sites. MiRNA concentrations in biofluids were estimated using a 3 parameter logistic (3PL) model.

The goal of this study was a better understanding of the technical factors contributing to variability in determinations of injury-induced miRNAs in biofluids. The findings will support improvements in measurement approaches that are needed to investigate the utility of circulating miRNAs as biomarkers of drug-induced injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies

The animal study was performed at Biologie Servier (Gidy, France) in 3 phases (Table 1). A dose range finding study was run first. The second phase focused on a blood processing comparison (serum vs plasma) and the third phase involved plasma and urine collections. Male Wistar rats (SPF Glx/BRL/Han) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories France (Domaine des Oncins, 69210 Saint-Germain sur l'Arbresle, France). Rats were acclimated for 1 week prior to use and were 12-week-old at dosing (275–325 g). Animals were assigned to dosage groups using a stratified randomization procedure based on body weight and group housed (2 or 3 rats/cage) in standard polycarbonate cages and kept under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with controlled temperature and humidity. Each animal was given ad libitum access to sterilized A04C-10 feed pellets purchased from SAFE (Villemoisson-sur-Orge, France), except when fasted overnight in the first, second, and third phases. Filtered tap water was available ad libitum. For Phase 3, animals were placed in individual metabolism cages during the 18 h urine collection period. Clinical observations, including checking for mortality and signs of morbidity, were performed daily throughout the study. Animals were euthanized by exsanguination under deep anesthesia (isoflurane inhalation). All procedures described in this study have been approved by the ethical committee for animal experimentation at Biologie Servier and were in accordance with the general requirements of the European Directive 2010/63/UE on the Protection of Animals used for Scientific Purposes.

Table 1.

Study Endpoints in Phases 1–3

| Study Phase | Isoproterenol Doses | Time Points | Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, or 1 mg/kg | 4, 24, and 48 h |

|

| Phase 2 | 0 or 0.5 mg/kg | 4 h |

|

| Phase 3 | 0 or 0.5 mg/kg | 24 h |

|

In the first phase, doses of 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 or 1 mg base/kg of isoproterenol hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich Ltd, UK) were administered by a single subcutaneous (sc) injection in 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride in a volume of 1 ml/kg to rats and euthanized at either 4, 24, or 48 h after treatment (n = 5 rats/dose/time). In the second phase, rats received either a single dose of 0.5 mg base/kg isoproterenol (n = 15) or the vehicle alone (n = 12) and euthanized 4 h after treatment. In the third phase, rats received either a single dose of 0.5 mg base/kg isoproterenol (n = 8) or vehicle alone (n = 5) and euthanized 24 h after treatment.

Blood was collected from the abdominal aorta of isoflurane-anaesthetised rats at 4 h post dosing in unfasted surviving animals in Phases 1 and 2, and at 24 h post dosing in rats fasted overnight in Phases 1 and 3. The hearts were weighed and the body weight at necropsy was used to calculate relative organ weights. In Phase 3, histology trimming of the heart followed the RITA procedure (Bahnemann et al., 1988) to be microscopically examined by a pathologist.

Blood processing

For plasma preparations, whole blood was collected in lithium heparinate tubes and EDTA tubes pre-cooled on ice and rapidly centrifuged [10 min, 2100 g, 4 °C]. Plasma from lithium heparinate tubes was individually aliquoted into pre-cooled microtubes for Troponin I (cTnI) analysis. For serum collection, whole blood was collected in a serum separator tube pre-cooled on ice, allowed to clot at room temperature for 30–60 min, and then centrifuged [15 min, 2000 g, 4 °C]. Serum or plasma prepared in EDTA-tubes was pooled by treatment group and aliquoted into sterile, RNAse-free microtubes pre-cooled on ice, frozen, and stored at −80 °C. Four aliquots of serum and/or plasma per dose group were shipped frozen on dry ice to each test site for miRNA analysis.

Cardiac troponin assay

Plasma from lithium heparinate tubes were individually aliquoted into microcentrifuge tubes (200 µl) pre-cooled on ice. Plasma sample frozen at –70 °C or below was sent over dry ice at Covance Laboratory SAS (France) for cTnI assessment using ACCESS 2, Beckman Coulter, immunoenzymatic immunoassay with Accu TnI assay. The plasma samples analyzed included 46 samples collected at 4 and 24 h from surviving rats in 5 dose groups in Phase 1, 25 samples collected at 4 h from 2 dose groups in Phase 2, and 11 samples collected at 24 h from 2 dose groups in Phase 3.

Urine collection

Urine was collected for 18 h on ice from animals placed 6 h after the injection in metabolism cages with access to water, but not access to feed. The urine from each rat was pooled together according to treatment group and centrifuged [5 min, 380 g, 4 °C]. One 300 µl aliquot of each pooled-urine supernatant was sampled for creatinine (uCrea), urea, and protein determinations. The remaining supernatants were centrifuged [10 min, 16 000 g, 4 °C]. Aliquots of pooled-urine supernatant were dispensed into sterile, RNAse-free tubes pre-cooled on ice and the remaining supernatant was stored into 1 plastic tube for further exosome isolation at NIDDK, NIH (see below). All urine samples were frozen and stored at −80 °C. Four urine aliquots per dose group were shipped frozen over dry ice to each test site for miRNA analysis.

Urine fractionation was performed at 4 °C at NIDDK, NIH, starting with 2.7 ml control rat urine supernatant and 2.47 ml rat urine from isoproterenol-treated rats. The supernatants were thawed, vigorously vortexed, and centrifuged [15 min, 17 000 g]. The 17 000 g pellet was resuspended in 200 µl TE. The 17 000 g supernatant was re-centrifuged [60 min, 200 000 g]. The resultant exosomal pellet was resuspended in 200 µl TE. All urinary fractions were stored at −80 °C (Zhou et al., 2006). RNA was extracted from 200 µl aliquots and analysed for miR-192-5p, miR-499-5p, miR-1-3p, and miR-208a-3p levels using the Phase 3 protocol.

MiRNA calibrators

For Phase 2, concentrated stocks of synthetic RNAs for the 4 target miRNAs (rno-miR-1-3p, rno-miR-16-5p, rno-miR-208a-3p, and rno-miR-499-5p) were purchased by participating sites from their preferred sources (Supplementary Data) and mixed to make an equimolar concentrated stock. A 10 point dilution series that spanned 4 logs (8.2 pmol/l to 0.5 fmol/l) was prepared by making six 4-fold serial dilutions of a 8.2 pmol/l stock, followed by 2 2-fold dilutions, and a no template (water) control. For Phase 3, a common pool was synthesized, HPLC-purified, quantified, and mixed by a contract lab (IDT, Coralville, Iowa) and distributed to test sites. This pool was composed of equimolar amounts of rno-miR-1-3p, rno-miR-192-5p, rno-miR-208a-3p, and rno-miR-499-5p sequences. A dilution series was prepared from a 2 pmol/l stock by making 8 three-fold serial dilutions. The lowest dilution was 0.3 fmol/l. The standard curve dilutions were prepared in water without or with the addition of non-mammalian RNA (MS2 bacteriophage RNA, Roche Diagnostics) as carrier to the diluent at a concentration of 0.5 ng/μl. Each site ran 2 standard curves for each run: one prepared with carrier and one without carrier. microRNA nomenclature is based on miRBase 21 (www.mirbase.org).

RNA isolation protocol

For the standard protocol, total RNA was isolated from 200 μl biofluid samples using miRNeasy mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, California). The manufacturer’s protocol was followed except that 5 µl of a 500 pmol/l stock of a synthetic Arabidopsis thaliana sequence (ath-miR159a) was added after addition of 3.5 volumes of QIAZol Lysis Reagent to the thawed samples and that Phase Lock Gel Tube Heavy 2 ml tubes (5 PRIME) were used to help separate phases. For analysis on the Exiqon platform, 70 µl of biofluid were used with miRNeasy mini kits with addition of MS2 RNA as carrier.

Phase 2 RT-qPCR protocol

A standard protocol was developed that was based on the manufacturer’s protocols for TaqMan™ miRNA assays and on methods described by Kroh et al. (2010), and customized for multiplexed analysis of 5 miRNA targets (Supplementary Data). The protocol is outlined in Figure 1. A 1× RT primer stock for 5 targets was prepared from 5× stocks of RT primers for rno-miR-1-3p, rno-miR-208a-3p, rno-miR-499-5p, ath-miR159a, and rno-miR-16-5p. This stock was used at 0.5× in a multiplexed RT reaction with 5 µl total RNA or 5 µL of each serial dilution of standards in 15 µl total reaction volume (16 °C, 30 min; 42 °C, 30 min; 85 °C, 5 min; 4 °C, hold). For preamplification reactions, equal volumes of 20× TaqMan™ miRNA assays for ath-miR-159a, rno-miR-208a-3p, rno-miR-499-5p, rno-miR-1-3p, and rno-miR-16-5p were combined, diluted to 0.2×, and used at a final dilution of 0.05×. Preamplification was performed using 2.5 µl of the RT reaction in a 25 µl reaction volume (95 °C, 10 min hold, followed by 14 cycles of 95 °C, 15 sec; 60 °C, 4 min). The preamplification products were diluted 20-fold and 5 µl of diluted product was used in 20 µl individual real time PCR reactions for each target (95 °C, 10 min, following by 40 cycles of 95 °C, 15 sec; 60 °C, 60 s). The differences in instrumentation used by 9 of the sites participating in Phase 2 are listed in Supplementary Data.

FIG. 1.

Outline of standard protocol for sample processing and analysis.

Phase 3 RT-qPCR protocol

The Phase 3 protocol was similar to the Phase 2 protocol with the following modifications (Supplementary Data). A 1× RT primer stock for 5 targets was prepared from 5× stocks of RT primers for rno-miR-1-3p, rno-miR-208a-3p, rno-miR-499-5p, ath-miR159a, and rno-miR-192-5p. This stock was used at 0.5× in a multiplexed RT reaction with 3 µl total RNA or 3 µl of each serial dilution of calibrators. For preamplification reactions, equal volumes of 20× TaqMan™ miRNA assays for ath-miR-159a, rno-miR-208a-3p, rno-miR-499-5p, rno-miR-1-3p, and rno-miR-192-5p were combined, diluted to 0.2×, and used at a final dilution of 0.05×. For analysis on the Exiqon platform, the manufacturer’s standard protocols for analysis of miRNAs in biofluids were followed (Exiqon miRCURY LNA Universal RT microRNA PCR, Instruction manual v5.1, February 2013), 3 RT replicates per sample were run in parallel, and a preamplification step was not included. The instrumentation used by 10 of the sites participating in Phase 3 are listed in Supplementary Data.

Data analysis and statistical approaches

Median normalization of sample threshold cycle (CT) using the exogenous miRNA spike-in CT values was performed as described by Kroh et al. (2010). A mean CT for ath-miR159a was determined per sample. The median of all mean ath-miR159a CTs within the same RT-qPCR run was determined. A normalization factor was calculated for each sample as follows: the median ath-miR159a CT minus the ath-miR159a CT for the sample. The normalization factor was added to the CT values for the assayed endogenous miRNAs to obtain median-normalized CT values. Estimated levels of miRNAs in urine were also normalized to urinary creatinine as described by Pavkovic et al. (2014).

A 3 parameter logistic (3PL) model was used to estimate miRNA concentrations in biofluid samples (http://www.jmp.com/support/help/Fit_Curve_Options.shtml), because many of the calibration curves were observed to be non-linear at low input concentrations. A logistic model can be an effective tool in analyzing calibration data as well as almost any kind of ligand-binding bioassay data (DeSilva et al., 2003). The model finds a smooth underlying S-shaped curve assumed to drive the responses along with estimates of the noise around it. Noise is estimated as a combination of lack of fit of the curve and variability across replicates at the same point. In addition to the usual modeling of y-axis values (CT in this case) as a function of x-values (log concentration in this case), the model also enables inverse prediction, in which an x-value is determined from an observed y-value by reflecting off of the fitted curve. For datasets in this study, we chose to use a 3PL model because it was the simplest logistic model that adequately describes the concentration-response relationship (Food and Drug Administration, 2001). We observed that the use of a four- or five-parameter model tends to overfit the data and sometimes produces spurious results (not shown). For plots of copy number per uL biofluid, the derived miRNA values were divided by 5 to estimate the concentration of RNA achieved from isolating RNA from 200 ul biofluid and eluting in a 40 ul volume.

In order to explore sources of variability in the estimated miRNA levels, we fit a variance components model to the inverse predictions from the 3PL model, each weighted by an estimate of precision. The model estimates the proportion of total variance attributable to each specified effect via restricted maximum likelihood (REML) and is a well-established way to efficiently determine which effects are driving changes in the data (Littell et al., 2006). The model also estimates least squares means for each effect. Least squares means are average effects over all of the other effects adjusted for imbalance in observed levels.

SOFTWARE

Calculations for the methods and graphics were performed in Excel, GraphPad Prism v5.03, and JMP. Significance of differences in estimated values between treatment conditions was determined by 1-way ANOVA of values combined across sites using Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test for pair-wise comparisons and α = 0.05 for significance level. A free JMP add-in called “Calibration Curves” is available at https://community.jmp.com/docs/DOC-6285 to aid in fitting 3PL curves and performing inverse prediction.

RESULTS

Cardiac Injury Model

To select the dose used to generate samples for miRNA analysis, a dose selection study was conducted in Wistar rats using a single sc administration of isoproterenol. Doses of isoproterenol and the route of administration were based on serum cardiac troponin validation studies (Clements et al., 2010; Schultze et al., 2011). In the dose range finding study, a single sc injection of isoproterenol that was administered at dose levels of 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 mg base/kg to male Wistar rats induced mortality in 3/15 rats in the 0.1 mg base/kg group and 1/15 rats in the 0.5 mg base/kg group within 1 h of dosing, likely as a result of severe respiratory distress. Cardiac troponin I evaluation showed evidence of dose-proportional increases in concentration at 4 and 24 h after dosing, with the greater increase seen at 4 h (data not shown). Mean plasma cTnI levels at 4 h ranged from 16 to 60 ng/ml between the lowest and highest dose groups. Dose-related myocardial necrosis/fibrosis was observed in all isoproterenol treated rats at 48 h (Supplementary Data). The dose of 0.5 mg base/kg of isoproterenol was considered to be a reasonable dose choice for assaying cardiac injury induced miRNA in the next 2 stages of the study. This dose balanced a maximizing of injury for release of miRNA with moderate clinical distress and minimization of early mortality.

In Phase 2, mortality was observed in 2/15 rats receiving a dose of 0.5 mg base/kg of isoproterenol. Elevated levels of plasma cTnI were observed in all treatment group rats at 4 h, ranging from 3.9 to 90.29 ng/ml (Figure 2), with a mean level of 29.8 ng/ml. The plasma cTnI levels in control rats were below the limit of quantitation (LOQ) of 0.1 ng/ml.

FIG. 2.

Plasma cTnI levels after sc administration of isoproterenol or saline. Results are shown from Phase 2 and 3 study samples collected 4 h after dosing with saline control (n = 12) or 0.5 mg base/kg of isoproterenol (treated) (n = 13) and 24 h after dosing with saline control (n = 5) or 0.5 mg base/kg of isoproterenol (n = 6). Levels lower than the limit of quantitation (LOQ) (0.1 ng/ml) were graphed at the LOQ. The mean and SD are shown for treated groups.

In Phase 3, mortality was observed in 2/8 rats receiving 0.5 mg base isoproterenol/kg. Plasma cTnI levels were increased at 24 h in the 6 surviving animals (Figure 2). The mean cTnI concentration was 7.5 ng/ml in the treatment group. In the control group, cTnI levels in plasma samples from 2 animals were slightly above the LOQ (0.11 and 0.19 ng/ml) and below the LOQ in the remaining 3 animals. Urinary parameters for pooled urine from treated and control groups were recorded for potential use for normalizing miRNA levels (Supplementary Data).

Comparison of Isoproterenol-Induced miRNA in Serum Versus Plasma

For the Phase 2 study, 9 sites received 4 different samples: pooled control serum, pooled control plasma, pooled isoproterenol treatment serum, and pooled isoproterenol treatment plasma, all taken 4 h after vehicle or isoproterenol treatment. The 4 different biological samples were assayed in parallel and replicate aliquots of the same biological sample were assayed independently (3 preparations on different days or different times of day), starting from the RNA extraction step. Sites agreed to follow a standard protocol that was developed for absolute quantitation of 4 miRNAs in the 4 samples (Figure 1). The protocol was based on TaqMan™ reagents and published protocols (Kroh et al., 2010), modified for multiplexed measurement of 5 target miRNAs and was pilot tested by one of the participating sites. In Phase 2, 1 site (Site J) modified the standard protocol by excluding a dilution step for the preamplification reaction prior to qPCR. The targets included 3 cardiac-enriched miR-1-3p, miR-208a-3p, and miR-499-5p, an endogenous reference miRNA that is expected to be easily detected in biofluids but to remain relatively unchanged by drug treatment (miR-16-5p in Phase 2), and an exogenous synthetic miRNA spiked into the biofluid samples before RNA isolation that could serve as a potential process control or normalizer. Each site prepared calibration curves from serial dilution of a set of mixed synthetic miRNAs that were run in parallel to the biosamples. Sites were asked to obtain custom-synthesized RNA from their vendor of choice for all miRNA targets for the calibration curves. An exogenous non-mammalian miRNA spike-in control was also assayed by RT-qPCR so that the effect of normalization to a spiked-in synthetic RNA control could be determined.

In order to explore sources of variability in measuring miRNA levels in biofluids, we fit a variance components model to the inverse predictions, each weighted by an estimate of precision. The model estimates the proportion of total variance attributable to each of the effects included in the study or to residual (unexplained) effects. The effects in our study consisted of the following: miRNA species, site, treatment, biofluid, normalization, RNA preparation number, and RT-qPCR run number. We also included an interaction effect between miRNA and site (denoted miRNA*Site), that models variability across miRNA levels that are different across sites. The results are plotted in Figure 3A. The main conclusion from the variance components model fit for the serum versus plasma comparison (Phase 2) is that miRNA and site are the 2 primary sources of variability, explaining 48.4 and 35.6% of the total variance, respectively. There is a small degree of interaction between these 2 effects (3.1%), which can be viewed as one measure of irreproducibility across sites. However, its low magnitude compared to that of its constituent main effects is evidence of success of this collaborative experiment. There is also a relatively small effect of isoproterenol treatment (5.4%). All other effects are very small.

FIG. 3.

Sources of variability attributable to specific effects within datasets. The inverse predictions from the Phase 2 (A) and Phase 3 (B) datasets, weighted by an estimate of precision, were fit to a variance components model to estimate the proportion of total variance attributable to included effects and interactions between effects.

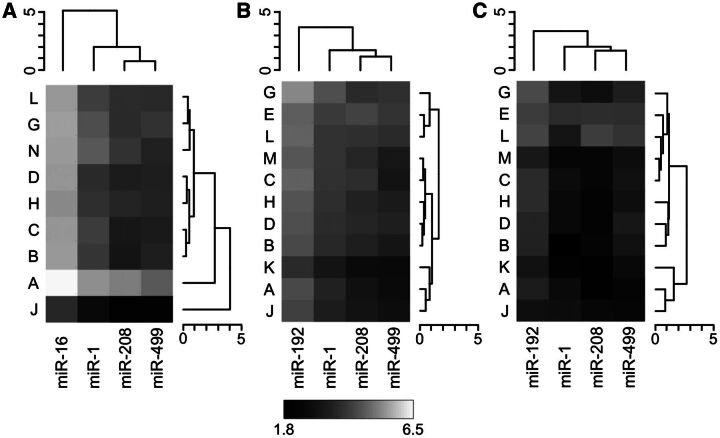

To visualize the interaction between site and miRNA, the least squares means of each unique combination of these 2 effects are plotted as a hierarchically clustered heat map in Figure 4A. In this plot, the intensity gradients for each site are similar, indicating a lack of interaction with miRNA. Two sites (A and J) appear to be outliers compared to the others. While the outlying performance of Site A could not be linked to any reported process, Site J deviated from the standard protocol by omitting a dilution step. To explore the degree that these 2 sites are influencing results, we dropped them successively from the data and repeated the model fitting process. After first dropping site J, the percentage of variability attributable to sites was reduced from 35.6 to 15.3%. After then removing site A, the site variance was further reduced to 2%, indicating excellent agreement across sites after the 2 outlying ones have been removed. The percentages attributable to treatment and residual increased slightly and became the next 2 largest sources of variance after miRNA amongst the 7 sites remaining in the dataset.

FIG. 4.

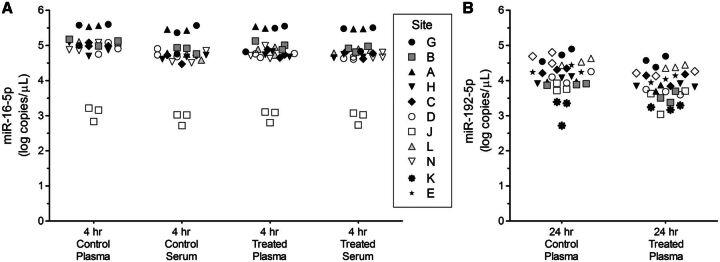

Heat maps of miRNA*Site least squares means. Hierarchical clustering of least squares means by site (coded by letter) and miRNA was performed for (A) Phase 2 plasma and serum samples, (B) Phase 3 plasma samples, and (C) Phase 3 urine samples. The heatmap greyscale denotes the range of least squares means across all three panels. The dendrogram heights indicate Euclidean distance.

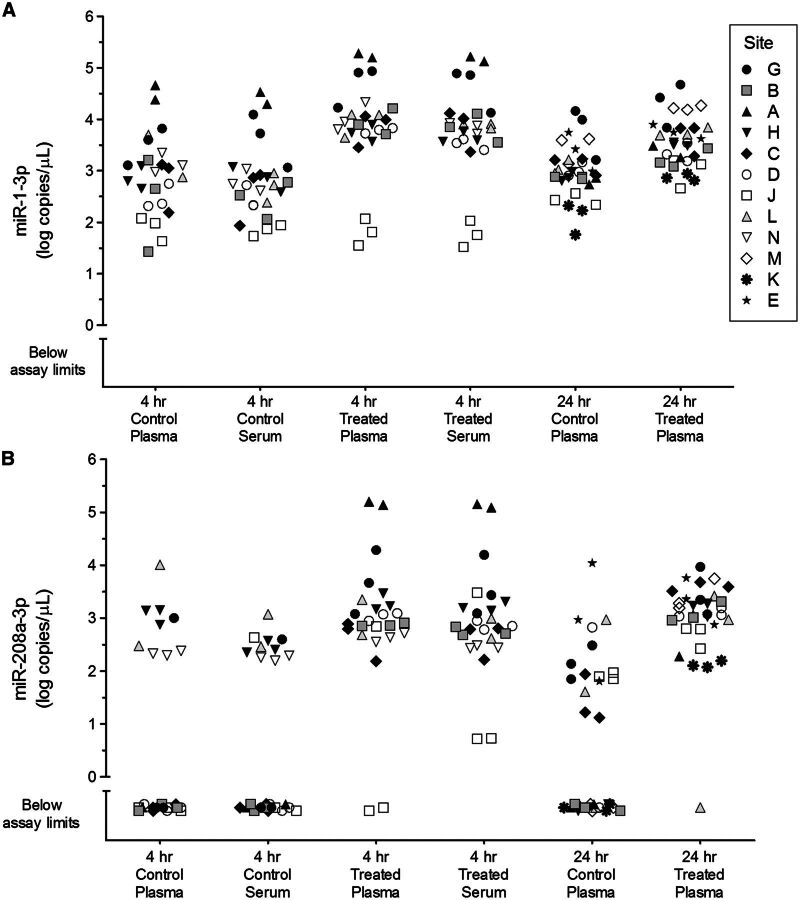

Increased circulating levels of 3 cardiac injury-associated miRNAs were detected by most sites in biofluids from rats 4 h post dosing with isoproterenol (Figure 5; Supplementary Data). Levels of miR-1-3p were detectable in control plasma and serum, and were significantly increased by an average of 10-fold 4 h after treatment. Plasma or serum levels of miR-208a-3p in controls were below assay limits in over half of measured data points but rose significantly above baseline levels 4 h after treatment. No significant difference was observed between 4 h serum and 4 h plasma levels of miR-1-3p in controls, between 4 h serum and 4 h plasma levels of miR-1-3p in treated rats, or between 4 h serum and 4 h plasma levels of miR-208a-3p in treated rats. MiR-499-5p levels were also elevated in serum and plasma at 4 h post treatment (Supplementary Data). Levels of miR-16-5p were similar in serum and plasma samples (Figure 6A). MiRNA levels measured by the sites that were outliers in the variance analysis (A and J) are also clear outliers compared to other sites in these graphs (Figures 5 and 6A; Supplementary Data).

FIG. 5.

Levels of miR-1-3p and miR-208a-3p in control and isoproterenol-treated rat plasma and serum samples. Data is combined across Phase 2 and Phase 3 studies for miR-1-3p (A) and miR-208a-3p (B) from the sites indicated in the figure legend for (A). Estimated values in log10 copies per µL biofluid are shown for 3 day-to-day replicates per site. Data points below the lowest calibrator concentration, with no computed value in 3PL models, or with an “undetermined” CT value in qPCR assays were categorized as “below assay limits.” The 24-h time point samples were derived from calibration curves where carrier RNA was included in the diluent.

FIG. 6.

Levels of miR-16-5p and miR-192-5p in control and isoproterenol-treated rat plasma and serum samples. Data for miR-16-5p (A) is from the Phase 2 study and the data for miR-192-5p (B) is from the Phase 3 study for the sites indicated in the figure legend for (A). Estimated values (log10 copies per µL biofluid) are shown for 3 day-to-day replicates per site. The 24 h time point samples were derived from calibration curves where carrier RNA was included in the diluent.

Comparison of Isoproterenol-Induced miRNA in Plasma Versus Urine

For the Phase 3 study, eleven sites received concentrated stocks of calibrators and 4 different samples: pooled control urine, pooled control plasma, pooled isoproterenol treatment urine, and pooled isoproterenol treatment plasma, with samples taken 24 h after exposure start (Figure 1). miR-192-5p was used as the reference miRNA in Phase 3, due to its abundance in both urine and plasma. Site M used a different type of RT-qPCR platform (Exiqon) than the other sites. Similar to the Phase 2 study, a 3 parameter logistic model was used to calculate miRNA concentrations in biofluid samples from calibration curves.

Sources of variability were explored by fitting a variance components model to the inverse predictions each weighted by an estimate of precision. RNA carrier was included as an effect in addition to those used in Phase 2. For comparison of plasma and urine values in this analysis, urine miRNA values were not normalized to uCrea. In contrast to Phase 2, in which only 2 effects are dominant (miRNA and Site), a third effect (Biofluid) is now the most prominent, accounting for 30.7% of the total variance (Figure 3B). This is explained by the fact that the 2 biofluids compared here (plasma and urine) are much more compositionally distinct than those compared in Phase 2 (plasma and serum). There is also a relatively small degree of interaction between the 3 main sources of variability, modeled by three 2-way interactions (miRNA*Site, miRNA*Biofluid, Site*Biofluid) and one 3-way interaction (miRNA*Site*Biofluid). The treatment effect (2.9%) is similar in size to the interactions. All other effects (inclusion or omission of RNA carrier in diluent for calibration curve dilutions, with or without normalization to an exogenous spike-in miRNA) are very small. The residual effect indicates that 9.3% of total variability is unexplained.

Least squares means for the 3-way interaction (miRNA*Site*Biofluid) are plotted in Figure 4B and C as hierarchically clustered heatmaps. This plot breaks down the components of the main effects and interactions of the 3 dominant factors. The large biofluid main effect is illustrated by the overall differences in least square means patterns across the 2 plots. The plasma profiles are similar to those observed in Phase 2, and for urine the relative amount of miR-499-5p increases and miR-1-3p decreases, which drives the miRNA*Biofluid interaction effect (7.3%). There is a certain degree of variability across sites (primarily a main effect in which the values for one site are additively larger or smaller than those for another site), but in contrast to Phase 2, no sites appear to be strong outliers and sites cluster similarly in the 2 plots.

Elevated plasma levels of miR-208a-3p were detected by all sites 24 h after a single dose of isoproterenol (Figure 5). At this time point, plasma levels of miR-1-3p were elevated by an average of 3.5-fold but no significant treatment-related change in plasma miR-499-5p levels was observed (Supplementary Data). MiRNA levels determined by Site M using Exiqon RT-qPCR reagents were found to be highly similar to those determined using the standard protocol with TaqMan RT-qPCR reagents. No significant difference was observed between 4 h plasma and 24 h plasma levels of miR-1-3p in controls, between 4 h plasma and 24 h plasma levels of miR-208a-3p in treated rats, or between 4 h plasma and 24 h plasma levels of miR-1-3p in treated rats. miR-192-5p was generally observed to be slightly lower in plasma from treated animals compared to controls (Figure 6B).

Urinary levels of miR-192-5p were measurable by all sites, but more variable results were obtained for the cardiac injury-associated miRNAs in urine. The combined percentage of measurements in urine from control and treated rats that were within the measurable range (i.e., not less than the lowest dilution of calibration curves) ranged from around 60% for miR-499-5p and 50% for miR-1-3p, to only 30% for miR-208a-3p (Supplementary Data). The mean levels of miR-192-5p were similar in control and treatment urine (153 ± 0.9 and 173 ± 0.5 copies/µmol uCrea, respectively). This result is in agreement with lack of macroscopic or relevant histomorphological changes observed in the kidney 24 h after administration of 0.5 mg/kg isoproterenol (data not shown). No apparent treatment related changes in the urinary levels of miR-499-5p, miR-1-3p, or miR-208a-3p were observed in this study.

DISCUSSION

We developed and evaluated a protocol for analysis of circulating miRNAs in their potential use as biomarkers of drug-induced tissue injury. We used a rat model of acute cardiac injury induced by short term isoproterenol treatment (Clements et al., 2010) and quantitated miRNA levels in plasma, serum and urine using an RT-qPCR approach. Histopathological examination and increased cTnI levels in plasma confirmed that the expected cardiac injury had occurred. Therefore, the biofluid samples were used for assessment of miRNAs known to be associated with cardiac injury (miR-1-3p, miR-208a-3p, miR-499-5p). In addition, miR-16-5p and miR-192-5p were measured as candidate endogenous reference miRNAs in plasma and serum, or plasma and urine, respectively. MiR-16-5p was reported to be present in easily measurable and similar amounts in plasma and serum (Wang et al., 2012) and/or in stable amounts in the presence of cardiac injury. Similar behavior was assumed for miR-192-5p, a kidney cortex enriched miRNA (Tian et al., 2008), based on published literature (Minami et al., 2014). Furthermore, ath-miR-159a was included as exogenously added spike-in to monitor sample processing in general, and for assessment as a potential normalizer. Since the major goal of this project was to assess factors contributing to variability of the miRNA measurement, the rat study was performed at 1 location, and samples from pooled biofluid samples were distributed to a number of participating laboratories.

RNA levels assayed by RT-qPCR are commonly expressed relative to a housekeeping RNA species (ΔCT) and to the average control level (ΔΔCT). Different approaches are needed to report and measure levels of microRNAs as injury-induced biomarkers in biofluids because there is no consensus on the use of endogenous miRNAs present in biofluids for normalization and baseline levels of injury-induced miRNAs may be very low in biofluids and only measurable if elevated by tissue injury. For these reasons, we performed absolute quantitation with RT-qPCR, which requires the use of calibration curves of synthetic miRNA sequences. Such calibration curves need to be analyzed in parallel with samples, but serial dilutions of standards can add variability to the results. Digital PCR is an alternate approach for absolute quantitation of miRNA that doesn’t require calibration curves (Hindson et al., 2013), but this technology was not available at most sites when the study was initiated, so it was not included. A common finding among the 14 total participating sites in Europe, Japan, and the United States that ran the standard protocol using TaqMan reagents was that calibration curves of synthetic miRNA often assumed non-linearity at low input concentrations. This phenomenon was consistent with the detection of low levels of artifacts generated by RT-qPCR, such as primer-dimers. The contributing causes of RT-qPCR artifacts appear to be multifactorial. We determined that the best approach for fitting all observed types of calibration curve data (linear and non-linear) in the studies to a single model was a 3 parameter logistic fit. This method has been made available as a free add-in to JMP. Further evaluation of methods for determining the lower limit of quantitation for these types of data is needed.

For the Phase 2 study comparing miRNAs in serum and plasma, most of the 9 sites showed fair agreement among estimated levels of 3 cardiac injury-induced miRNAs and 1 reference miRNA assayed in biofluids. We observed no significant difference in the use of serum versus plasma as a source of circulating miRNA after isoproterenol-induced acute cardiac necrosis. Better agreement in plasma miRNA levels between sites was observed in Phase 3, with no sites appearing as outliers. Although conforming sites used a standard protocol, they used different makes and models of instrumentation for some steps, different reagent lots, and different settings (manual or automatic) for determining baseline and thresholds. The improved agreement between sites in Phase 3 may be the result of protocol changes (such as the use of a common source of calibrators) and/or the increased experience of enrolled sites. The use of RNA carrier in calibrator serial dilutions, which was also tested in Phase 3 (data not shown), was found to not have a significant effect on inter- or intra-site variance. Normalization to an exogenous miRNA spike-in also did not have a significant impact on the consistency of results, as has been reported by others (McDonald et al., 2011). With timed urine collection, it is standard practice to normalize miRNA and other biomarker levels to urinary creatinine or urinary volume (Kanki et al., 2014; Pavkovic et al., 2014). For miR-192-5p, the reference miRNA abundantly expressed in urine, normalization to creatinine helped equalize levels in pooled control and treatment samples. In summary, the major sources of variance in our study were not likely due to sample losses or calibration curve inaccuracies that could be improved by the use of such specific additions to the standard protocol.

In this study, plasma cTnI levels were below detection levels in controls and highly elevated at 4 and 24 h after a single dose of 0.5 mg/kg isoproterenol to male Wistar rats. Of the miRNAs assayed, the heart-specific miRNA miR-208a-3p had the most similar profile to cTnI, which was consistent with the observations of Glineur et al., 2016 in a 4-day preclinical rat model of myocardial injury. MiR-1-3p is abundant in heart but also expressed in other muscle types (Oliveira-Carvalho et al., 2013) which may produce higher baseline levels for this miRNA in blood and lower induction levels. miR-499-5p was increased at 4 h post isoproterenol dosing but not different from control levels at 24 h. Although increased levels of miR-1 in serum and urine have been reported in patients after cardiac bypass surgery (Zhou et al., 2013) and increased levels of miR-1 and miR-208 in urine were observed in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction (Cheng et al., 2012), none of the 3 cardiac-expressed miRNAs were increased in urine collected over 18 h starting 6 h after isoproterenol dosing in this study. They were also not enriched in exosomal fractions from urine (data not shown). Shorter collection periods than were used in this study may be needed to see an effect on miRNA levels in urine indicative of cardiac injury, if changes in miRNA levels in blood translate into changes in urine.

Non-linearity of calibration curves at low input concentrations (Mitchell et al., 2008) and amplified products in the no-template-control samples (Hughes et al., 2014; Kelnar et al., 2014) have also been observed in other studies measuring small RNAs using TaqMan™ reagents, suggesting that current protocols may not be optimal for the applications needed in this study. To analyze this dataset, we developed a 3PL method for inverse prediction of unknown miRNA levels in biofluids that is compatible with both linear and non-linear calibration curves. The standard protocol used in this study, while not necessarily optimal, is useful as a benchmark protocol for analyzing small sets of selected microRNAs in biofluids as potential biomarkers of tissue injury. The moderate agreement in results between sites observed using the standard protocol provides a reference set for the comparability of absolute quantitation of miRNA data measured at different sites. Good interlaboratory agreement is necessary for use of data generated at different sites and used in aggregate to provide evidence of miRNA biomarker performance across a wide range of models of drug- and chemical-induced injury in both non-clinical and clinical samples.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the ILSI HESI Cardiac Troponins Working group for their input on dose selection and study design. Peter Mouritzen is an employee of Exiqon, which is a company that is a developer and producer of qPCR systems for detection of coding and noncoding RNAs.

Disclaimer: The statements, opinions, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views or positions of the authors’ institutions. Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by any of the authors’ institutions, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Contributor Information

Karol L. Thompson, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland 20993

Eric Boitier, Sanofi R&D, Disposition Safety and Animal Research, Vitry-Sur-Seine, France.

Tao Chen, Division of Genetic and Molecular Toxicology, National Center for Toxicological Research, Food and Drug Administration, Jefferson, Arizona 72079.

Philippe Couttet, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, CH 4057, Switzerland.

Heidrun Ellinger-Ziegelbauer, Toxicology, Bayer Pharma, Wuppertal, AG 42096, Germany.

Manuela Goetschy, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, CH 4057, Switzerland.

Gregory Guillemain, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, CH 4057, Switzerland.

Masayuki Kanki, Astellas Pharma Inc, Osaka 532-8514, Japan.

Janet Kelsall, AstraZeneca Ltd, Alderley Park, Macclesfield, Cheshire SK10 4TG, UK.

Claire Mariet, Sanofi R&D, Disposition Safety and Animal Research, Vitry-Sur-Seine, France.

Catherine de La Moureyre–Spire, Institut De Recherches Servier, 78290 Croissy Sur Seine, France.

Peter Mouritzen, Exiqon, Vedbaek DK-2950, Denmark.

Rounak Nassirpour, Pfizer, Andover, Massachusetts 01810

Raegan O’Lone, ILSI Health and Environmental Sciences Institute, Washington, DC 20005.

P. Scott Pine, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Stanford, California 94305.

Barry A. Rosenzweig, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland 20993

Tatiana Sharapova, AbbVie, Abbott Park, Illinois 60064.

Aaron Smith, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, Indiana 46285.

Hidefumi Uchiyama, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 251-8555, Japan.

Jian Yan, Division of Genetic and Molecular Toxicology, National Center for Toxicological Research, Food and Drug Administration, Jefferson, Arizona 72079.

Peter S. Yuen, NIH/NIDDK, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

Russ Wolfinger, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina 27513.

FUNDING

This HESI scientific initiative is primarily supported by in-kind contributions (from public and private sector participants) of time, expertise, and experimental effort. These contributions are supplemented by direct funding (that largely supports program infrastructure and management) that was provided by HESI’s corporate sponsors. A list of supporting organizations (public and private) is available at http://hesiglobal.org/application-of-genomics-to-mechanism-based-risk-assessment-technical-committee/3311.

REFERENCES

- Adachi T. Nakanishi M. Otsuka Y. Nishimura K. Hirokawa G. Goto Y. Nonogi H. Iwai N. (2010). Plasma microRNA 499 as a biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. Clin.Chem 56, 1183–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akat K. M. Moore-McGriff D. Morozov P. Brown M. Gogakos T. Correa Da Rosa J. Mihailovic A. Sauer M. Ji R. Ramarathnam A., et al. (2014). Comparative RNA-sequencing analysis of myocardial and circulating small RNAs in human heart failure and their utility as biomarkers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 111, 11151–11156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahnemann R. Jacobs M. Karbe E. Kaufmann W. Morawietz G. Nolte T. Rittinghausen S. (1988). Registry of Industrial Toxicology Animal-data. Guides for organ sampling and trimming procedures in rats. Exp. Toxic. Pathol. 47, 247–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. Wang X. Yang J. Duan X. Yao Y. Shi X. Chen Z. Fan Z. Liu X. Qin S., et al. (2012). A translational study of urine miRNAs in acute myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 53, 668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. H. Yi H. S. Kim Y. Kroh E. M. Chien J. W. Eaton K. D. Goodman M. T. Tait J. F. Tewari M. Pritchard C. C. (2013). Plasma processing conditions substantially influence circulating microRNA biomarker levels. PLoS One 8, e64795.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements P. Brady S. York M. Berridge B. Mikaelian I. Nicklaus R. Gandhi M. Roman I. Stamp C. Davies D. Turton J., et al. ILSI HESI Cardiac Troponins Working Group. (2010). Time course characterization of serum cardiac troponins, heart fatty acid-binding protein, and morphologic findings with isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in the rat. Toxicol. Pathol. 38, 703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandra Y. Devanna P. Limana F. Straino S. Di Carlo A. Brambilla P. G. Rubino M. Carena M. C. Spazzafumo L. De Simone M., et al. (2010). Circulating microRNAs are new and sensitive biomarkers of myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 31, 2765–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva B. Smith W. Weiner R. Kelley M. Smolec J. Lee B. Khan M. Tacey R. Hill H. Celniker A. (2003). Recommendations for the bioanalytical method validation of ligand-binding assays to support pharmacokinetic assessments of macromolecules. Pharm. Res. 20, 1885–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux Y. Vausort M. Goretti E. Nazarov P. V. Azuaje F. Gilson G. Corsten M. F. Schroen B. Lair M. L. Heymans S., et al. (2012). Use of circulating microRNAs to diagnose acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chem. 58, 559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge A. Lee I. Hood L. Galas D. Wang K. (2011). Extracellular microRNA: a new source of biomarkers. Mutat. Res. 717, 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W. Grosshans H. (2011). The liver-specific microRNA miR-122: biology and therapeutic potential. Prog. Drug Res. 67, 221–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation, May 2001.

- Glineur S. F. De Ron P. Hanon E. Valentin J. P. Dremier S. Nogueira da Costa A. (2016). Paving the Route to Plasma miR-208a-3p as an Acute Cardiac Injury Biomarker: Preclinical Rat Data Supports Its Use in Drug Safety Assessment. Toxicol. Sci. 149, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermeking H. (2012). MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindson C. M. Chevillet J. R. Briggs H. A. Gallichotte E. N. Ruf I. K. Hindson B. J. Vessella R. L. Tewari M. (2013). Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nat. Methods 10, 1003–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. Byrne A. Barfield M. Spooner N. Summerfield S. (2014). Preliminary investigation into the use of a real-time PCR method for the quantification of an oligonucleotide in human plasma and the development of novel acceptance criteria. Bioanalysis 6, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarry J. Schadendorf D. Greenwood C. Spatz A. van Kempen L. C. (2014). The validity of circulating microRNAs in oncology: Five years of challenges and contradictions. Mol. Oncol. 8, 819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X. Takahashi R. Hiura Y. Hirokawa G. Fukushima Y. Iwai N. (2009). Plasma miR-208 as a biomarker of myocardial injury. Clin. Chem. 55, 1944–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki M. Moriguchi A. Sasaki D. Mitori H. Yamada A. Unami A. Miyamae Y. (2014). Identification of urinary miRNA biomarkers for detecting cisplatin-induced proximal tubular injury in rats. Toxicology 324, 158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelnar K. Peltier H. J. Leatherbury N. Stoudemire J. Bader A. G. (2014). Quantification of therapeutic miRNA mimics in whole blood from nonhuman primates. Anal. Chem. 86, 1534–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. J. Linnstaedt S. Palma J. Park J. C. Ntrivalas E. Kwak-Kim J. Y. Gilman-Sachs A. Beaman K. Hastings M. L. Martin J. N., and., et al. (2012). Plasma components affect accuracy of circulating cancer-related microRNA quantitation. J. Mol. Diagn. 14, 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroh E. M. Parkin R. K. Mitchell P. S. Tewari M. (2010). Analysis of circulating microRNA biomarkers in plasma and serum using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). Methods 50, 298–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J. Loedige I. Filipowicz W. (2010). The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell R. C. Milliken G. A. Stroup W. W. Wolfinger R. D. Schabenberger O. (2006). SAS for Mixed Models, 2nd Ed.SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. S. Milosevic D. Reddi H. V. Grebe S. K. Algeciras-Schimnich A. (2011). Analysis of circulating microRNA: preanalytical and analytical challenges. Clin. Chem. 57, 833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. S. Parkin R. K. Kroh E. M. Fritz B. R. Wyman S. K. Pogosova-Agadjanyan E. L. Peterson A. Noteboom J. O'Briant K. C. Allen A., et al. (2008). Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10513–10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami K. Uehara T. Morikawa Y. Omura K. Kanki M. Horinouchi A. Ono A. Yamada H. Ohno Y. Urushidani T. (2014). miRNA expression atlas in male rat. Sci. Data 1, 140005.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Carvalho V. da Silva M. M. Guimarães G. V. Bacal F. Bocchi E. A. (2013). MicroRNAs: new players in heart failure. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 2663–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavkovic M. Riefke B. Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H. (2014). Urinary microRNA profiling for identification of biomarkers after cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Toxicology 324, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard C. C. Cheng H. H. Tewari M. (2012). MicroRNA profiling: approaches and considerations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 358–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikumar J. Ramachandran K. Vaidya V. S. (2014). Noninvasive micromarkers. Clin. Chem. 60, 1158–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze A. E. Main B. W. Hall D. G. Hoffman W. P. Lee H. Y. Ackermann B. L. Pritt M. L. Smith H. W. (2011). A comparison of mortality and cardiac biomarker response between three outbred stocks of Sprague Dawley rats treated with isoproterenol. Toxicol. Pathol. 39, 576–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharapova T. Devanarayan V. LeRoy B. Liguori M. J. Blomme E. Buck W. Maher J. (2016). Evaluation of miR-122 as a serum biomarker for hepatotoxicity in investigative rat toxicology studies. Vet. Pathol. 53, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Z. Greene A. S. Pietrusz J. L. Matus I. R. Liang M. (2008). MicroRNA-target pairs in the rat kidney identified by microRNA microarray, proteomic, and bioinformatic analysis. Genome Res. 18, 404–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacchi-Suzzi C. Hahne F. Scheubel P. Marcellin M. Dubost V. Westphal M. Boeglen C. Büchmann-Møller S. Cheung M. S. Cordier A., et al. (2013). Heart structure-specific transcriptomic atlas reveals conserved microRNA-mRNA interactions. PLoS One 8, e52442.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Zhang S. Marzolf B. Troisch P. Brightman A. Hu Z. Hood L. E. Galas D. J. (2009). Circulating microRNAs, potential biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4402–4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Yuan Y. Cho J. -H. McClarty S. Baxter D. Galas D. J. (2012). Comparing the microRNA spectrum between serum and plasma. PLoS ONE 7, e41561.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. Kanchagar C. Veksler-Lublinsky I. Lee R. C. McGill M. R. Jaeschke H. Curry S. C. Ambros V. R. (2014). Circulating microRNA profiles in human patients with acetaminophen hepatotoxicity or ischemic hepatitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 111, 12169–12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. Yuen P. S. T. Pisitkun T. Gonzales P. A. Yasuda H. Dear J. W. Gross P. Knepper M. A. Star R. A. (2006). Collection, storage, preservation, and normalization of human urinary exosomes for biomarker discovery. Kidney Int. 69, 1471–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Mao A. Wang X. Duan X. Yao Y. Zhang C. (2013). Urine and serum microRNA-1 as novel biomarkers for myocardial injury in open-heart surgeries with cardiopulmonary bypass. PLoS One 8, e62245.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.