Abstract

Background

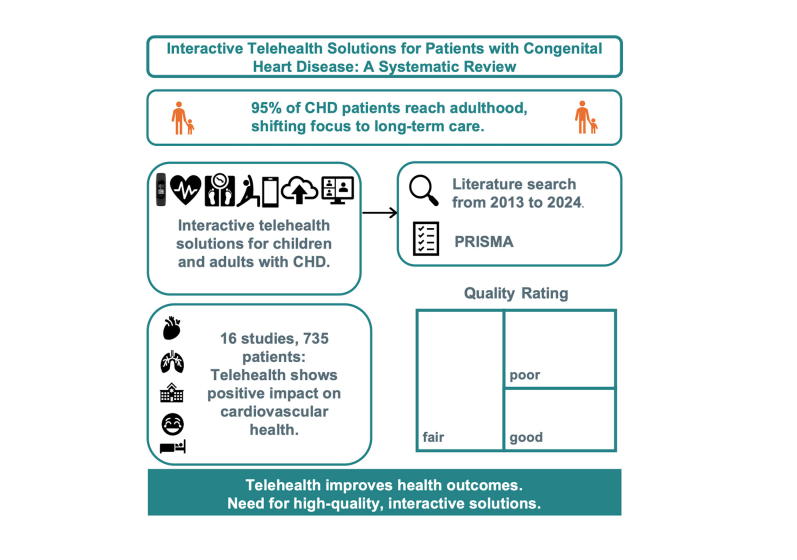

As 95% of patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) reach adulthood, the focus has shifted from early mortality to long-term morbidity, necessitating regular specialized follow-ups and more emphasis on health promotion. In this regard, telehealth could represent an innovative care method for live supervision and promoting lifestyle changes. This systematic review investigates interactive telehealth solutions including application program interfaces for children and adults with CHD.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) from January 1, 2013, to April 1, 2024, on interactive telehealth solutions for children and adults with CHD.

Results

Of 16 included studies, 9 studies evaluated 318 pediatric patients with diagnosed CHD, 4 studies included 229 pediatric and adult patients with CHD, and 3 studies examined 188 adults. A total of 8 studies investigated teledevices: 5 explored mobile applications and 3 used wearables. Studies assessed telehealth interventions using maximum or peak oxygen consumption for physical performance, questionnaires for health-related quality of life, sleep, and well-being, and tracked emergency visits, intensive care unit stays, and disease complications. Additional measures included infant growth, body weight, and arrhythmias.

Conclusions

The majority of studies indicate that telehealth solutions have a positive impact on cardiovascular health. To ensure medical care for these patients, the implementation of more high-quality, interactive, and live telehealth solutions beyond home monitoring is essential. It could offer the opportunity to promote early prevention strategies, such as improving fitness and behavioral changes while ensuring the safety of each individual.

Résumé

Contexte

Avec 95 % des patients atteints d’une cardiopathie congénitale (CC) qui parviennent à l’âge adulte, l'accent est passé de la mortalité précoce à la morbidité à long terme. Cela nécessite un suivi spécialisé à intervalles réguliers qui laisse une large place à la promotion de la santé. La télésanté pourrait représenter à cet égard une méthode de soins novatrice pour surveiller les patients en direct et promouvoir les modifications au mode de vie. Cette revue systématique s’intéresse aux solutions de télésanté interactives, comme les interfaces de programmation d’applications pour les enfants et les adultes atteints d’une CC.

Méthodologie

Nous avons réalisé une recherche bibliographique systématique selon la norme PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) entre le 1er janvier 2013 et le 1er avril 2024 portant sur les solutions de télésanté interactives pour les enfants et les adultes atteints d’une CC.

Résultats

Parmi les 16 études incluses, 9 ont été menées chez 318 enfants ayant reçu un diagnostic de CC; 4, chez 229 adultes et enfants atteints d’une CC et 3, chez 188 adultes. Au total, 8 études ont examiné les dispositifs à distance : 5 ont évalué les applications mobiles et 3 ont utilisé des dispositifs portables. Les interventions en télésanté ont été évaluées à l’aide de la V02max pour la performance physique, et de questionnaires sur la qualité de vie liée à la santé, le sommeil et le bien-être. Les visites à l’urgence, les séjours en unité de soins intensifs et les complications de la maladie ont également fait l’objet d’un suivi. La croissance chez le nourrisson, le poids corporel et les arythmies sont d’autres paramètres qui ont été mesurés.

Conclusions

La majorité des études indique que les solutions de télésanté ont une incidence positive sur la santé cardiovasculaire. Afin d’assurer à ces patients de recevoir des soins médicaux, il est essentiel de mettre en œuvre des solutions de télésanté en direct interactives de haute qualité, en plus de la surveillance à domicile. Ces solutions pourraient être l’occasion de promouvoir des stratégies de prévention précoces, comme l’amélioration de la condition physique et les changements de comportement, tout en garantissant la sécurité de chacun.

Advancements in medical care for patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) have significantly transformed their clinical profile. In 2008, the European Union registered the adult CHD (ACHD) population outnumbering the pediatric CHD population for the first time.1 As 95% of patients now reach adulthood, the focus has even more shifted from early mortality to long-term morbidity.2,3 This trend is expected to continue, suggesting a steady rise in the number of ACHD cases.4 Consequently, CHD remains a lifelong condition, necessitating regular follow-up with specialized care to ensure positive long-term outcomes. This involves the timely identification and management of specific and often unpredictable complications.1

Patients with CHD rely on regular cardiologist appointments for vital sign assessments, typically scheduled at set intervals regardless of symptoms.5 When symptoms arise, patients must arrange additional appointments or visit the emergency department, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment.6 Conditions such as cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure often lead to emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or premature death.5 Given these complications, digital follow-up solutions are suitable. During the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine (TM) emerged as a viable alternative, allowing remote care under dedicated ACHD teams’ supervision.7

Since then, mobile health (mHealth) telemonitoring or TM has become increasingly popular with the help of expanding mobile health applications (apps), smartphone features, and wearables from many different vendors.8 It could simplify the process of ongoing vital sign monitoring from home, presenting opportunities for timely intervention or reassurance during daily-life monitoring or exercise. This could potentially reduce the need for emergency department visits and hospitalizations.9

However, the simple use for monitoring vital signs is interesting not only in this context but also in the area of application and implementation of digital cardiac rehabilitation programs. Previous studies have already investigated various models of TM or mHealth aftercare programs in patients with CHD. On the one hand, cardiac home-based rehabilitation has been associated with markedly reduced interstage mortality in individuals with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.10 In addition, a supervised home-based exercise program has shown considerable promise in augmenting exercise capacity among ACHD patients.11 On the other hand, a digital health-nudging intervention12 and a web-based exercise intervention13 did not improve physical activity in children with CHD. Above all, new emerging application program interfaces (APIs) allow medical staff to share data in structured ways with external systems. It enables monitoring during exercise as well as diagnosis and treatment on demand.

Inconsistent results, new evolving technologies, and limited clinical experience in mHealth in patients with CHD make it all the more important to investigate them. For this reason, this systematic review elaborates on interactive telehealth solutions for children and adults with CHD.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search encompassing the electronic databases PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus was undertaken, including articles from January 1, 2013, to April 1, 2024. Relevant studies in the English language were identified by 2 independent reviewers (C.S. and J.M.). A standard protocol with search terms was developed according to the population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and context (PICO-C)14 method and applied in the following combination:

-

(1)

("congenital heart disease") OR ("congenital heart diseases") OR ("congenital heart defect") OR ("congenital heart defects") AND

-

(2)

(("telemedicine") OR ("mHealth") OR ("eHealth") OR ("mobile health") OR ("electronic health") OR (teleconsult) OR (home monitoring) OR ("telehealth") OR (wearable) OR ("telecardiology") OR ("mobile app") OR ("mobile device") OR ("electronic device"))

Medical Subject Headings terms and filters (published in the previous 10 years, English, humans, child: birth to 18 years, adult: 18+ years) were used and appropriately adapted if necessary.

Data collection

Two reviewers screened the relevant articles for title and abstract that had to fulfill the basic inclusion criteria: patients with diagnosed CHD, focus on telehealth interventions, original contributions, and measured health-related outcomes. Additional exclusion criteria are studies investigating new diagnostic screening for illness and studies including pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, or pregnant study subjects. At least one of the reviewers had to consider a reference eligible; in case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted for a majority decision before full-text analysis. The final full texts with its telehealth instruments were divided into 3 main groups: teledevices, mobile applications, and wearables.

Reviewers documented the critical appraisal of the included literature using the “Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies”, “Study Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies”, and “Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group” from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. These tools consist of a 12- or 14-item list that assesses potential risk of instead of for bias. Based on this assessment, the included studies were categorized as “good,” “fair,” or “poor.”15

Results

Study inclusion

A total of 913 potential studies were initially identified through the search, with 631 remaining after duplicates were eliminated. After the screening of titles and abstracts, 59 studies were selected for full-text analysis. Among these, 43 studies were excluded due to their lack of focus on CHD; missing digital connection between health staff/researcher and patients/study subjects via a health API or online application platform; only concept, design, or feasibility studies without health-related outcomes; retrospective analyses; and missing full texts in English language.

Finally, 16 studies with a total of 735 patients with CHD met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. The search algorithm and selection process are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search and selection process for systematic review according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). CHD, congenital heart disease.

Study characteristics and quality

In total, 5 randomized studies,16, 17, 18, 19, 20 1 clinical study,21 2 cohort studies,22,23 3 prospective studies,6,24,25 and 5 pilot projects with initial health-related results were analyzed. A total of 8 investigated teledevices,6,18,21, 22, 23, 24,26,27 5 explored mobile applications,17,19,20,25,28 and 3 studies used wearables.16,29,30

Of the 16 investigated studies, 9 evaluated 318 pediatric patients with diagnosed CHD at infant age up to 14 years (range: 2-109 patients). Of these, 7 studies had corresponding control groups. Four studies included pediatric CHD as well as ACHD patients with 229 patients aged 7-73 years (range: 9-103 patients). Among these, only 1 study had a corresponding control group. Further, 3 studies examined 188 ACHD patients aged 19-71 years (range: 24-109 patients; no controls).

Table 1 offers additional details regarding the study characteristics, results, areas, and length of telehealth interventions.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and outcomes

| Study | CHD, n (female) | Control group, n (female) | CHD diagnosis or severity (n) | Study design | Age ± SD (range), y/mo/d | eHealth intervention | Application programming interface | Results | Study acronym | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teledevices | ||||||||||

| Black et al., 201426 | 9 ES | 9 HC | HLHS + AA + MA or MS (4), HLHS + AS + MA or MS (1), HLHS+ MA + VSD + DORV (1), HLHS + AA + MA + cor triatriatum (1), DILV + TGA + coarctation of aorta (1), complex DORV (1) | Pilot study | 23 ± 33 (4-90 d) | Infant digital scale (model UC-321 pbt) pulse oximeter (model Pm-50): 12 months | All transmitted data were managed on a customized WebPortal (Tele-Modem; Aerotel Medical Systems Ltd, Holon, Israel). | 9 ED visits for ES vs 11 unscheduled ED visits for HC. Sudden death in 1 of 9 HC and 2 of 9 ES. | / | HM |

| Cooper et al., 202018 | 109 (51) | 110 (46) | RACHS-1 ≥ II: 1: 0 (0), 2: 10 (9.4), 3: 37 (34.1), 4: 21 (19.4), 5: 2 (2.4), 6: 38 (34.6) | Randomized trial | 38.9 ± 0.1 (/ d) | Telehealth home monitoring program with digital scale and pulse oximeter: 4 months | Automated communication through the Buddy Check Network (Caryl Technologies). | Infant growth in both groups was suboptimal. More infants in the IG were readmitted to the hospital (66% in IG vs 57% in CG; P < 0.001). | REACH | HM |

| Donati et al., 202121 | 26 (14) | 19 (/) | CHD and/or arrhythmia | Clinical trial | 25 ± 37 mo (1-7 y) | Pulsoximeter GIMA OXY-10, Thermometer TAIDOC TD-1241B, scale GIMA BABY, scale AND UC-351PBT-Ci, ECG device MR&D pulse v3: 2-6 months | Smart-hub software application, eg, E@syCare with integration with EMR. | Improvement in well-being and sleep quality, with a consequent reduction in anxious and stressful situations. | AIR CARDIO | HM |

| Harahsheh et al., 201622 | 56 (23) | 42 (20) | HLHS (38), other (18) | Cohort study | 5.9 ± 3.9 (/ d) | ExpressMDTM home telemedicine monitoring device (scales, pulse oximeter, blood pressure monitor, and glucose meter) during interstage period | Individual patient results available via a web-based portal. | Post-SVTF group had lower complications after stage II (18.4% vs 34.1%, P < 0.02), higher weight-for-age z scores at stage II (–1.5 ± 0.97 vs –1.58 ± 1.34, P < 0.02) and were less likely to have a stage II weight-for-age z score below –2 (26.5 vs 31.7%, P < 0.03). | SVTF | HM |

| Khoury et al., 202027 | 2 (1) | / | Fontan | Pilot study | 12 and 14 y | Home-based high-intensity interval trial program with telemedicine ergometer (MedBike): 8 weeks | The MedBike is a custom telemedicine ergometer for remote medical supervision and modulation of work. | Increased exercise capacity at postintervention CPET: VO2max (50% for subject 1 and 8% for subject 2) and peak power output (50% for subject 1 and 8% for subject 2). | / | PAP |

| Kauw et al., 20196 | 109 (73) | / | Simple (25), moderate (50), severe (34) | Prospective study | 44.8 ± 13.1 (/ y) | Single-lead ECG (Kardia, AliveCor), wireless digital blood pressure monitor (Omron), and a wireless and digital weight scale (iHealth), connected to their smartphone: 12-month follow-up | Mobile applications for heart rhythm recordings (Kardia) and blood pressure and weight (cVitals). Integration in EMR. | In 25% of the patients with diagnosed arrhythmias (14 of 56) recurrences were detected; 13% of the patients with undiagnosed palpitations (4 of 32) were diagnosed with novel arrhythmias. | / | HM |

| Koole et al., 201924 | 55 (36) | / | NYHA class ≥II: simple (6), moderate (29), severe (20) | Prospective study | Median age 45 y (19-70 y) | Single-lead ECG measurements, blood pressure (Omron), and a scale for body weight measurement (iHealth): 3-month follow-up | Smartphone applications (cVitals) to receive and transfer data. Integration in EMR. | Quality of life (CaRe-QoL CHF [social, physical, and safety] and EQ-5D-5L) improved by 51.7% (P < 0.502), 14.3% (P < 0.28), 3.3% (P < 0.87), and 0.2% (P < 0.89). | HartWacht | HM |

| Nederend et al., 202123 | 24 (12) | / | TGA (16), ccTGA (8) | Cohort study | Median age 47 y (/ y) | Blood pressure monitor (Withings Wi-Fi Smart), scale (Withings Body), step counter (Withings Move), and rhythm monitor (Alivecor KardiaMobile). Biweekly sacubitril/valsartan titration visits were replaced by electronic visits: 17-month follow-up | Health Mate app for iOS and Android transmits data (ECG recordings, blood pressure values to doctors). | 68 titration trips to hospital were replaced by virtual visits facilitated by remote monitoring. | / | HM |

| Mobile applications | ||||||||||

| Bingler et al., 201817 | 31 (13) | 1 month: 16 (9) 2 months: 15 (4) |

Single ventricle cardiac disease | Randomized crossover design | 1 mo: 1.44 (0.80-2.13 mo) 2 mo: 0.70 (0.47-1.43 mo) |

Cardiac High Acuity Monitoring Program (CHAMP) is a tablet PC–based app (oxygen saturation, intake, output, infant weight, 15-second videos, preselected patient-specific red flag warnings, and parental concerns) | CHAMP provides instantaneous transfer of home monitoring data via cellular service. | CHAMP group had significantly fewer unplanned intensive care unit days/100 interstage days, shorter delays in care, lower resource utilization at readmissions, and lower incidence of interstage growth failure. | CHAMP | HM |

| Stagg et al., 202325 | 29 (/) | 43 (/) | HLHS, DORV, ToF/PS, PA | Prospective oberservational study | Infants | Software embedded in the EMR (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) to conduct telemedicine visits during interstage period | Epic Care Companion app in MyChart to upload monitoring data. | Median ED visits/patient/month were significantly lower than the same calendar period of the prior year (P < 0.0004). | Infant Single Ventricle Monitoring Program | HM |

| Zhang et al., 202220 | 42 (18) | 42 (19) | VSD (24), PDA (8), PS (3), ToF (2), endocardial cushion defect (2) | Prospective randomized controlled study | 3.3 ± 3.1 (/ mo) | WeChat (Tencent Ltd, Shenzhen, China): Smartphone-based social media application delivering remote health education and feeding guidance: 1 month | Medical staff was online in the WeChat group at 18:00 to 21:00 to explain parents’ problems. | Body weight, albumin, prealbumin, hemoglobin, and STRONGkids score of infants in the IG significantly higher than in CG 1 month after discharge (P < 0.05). | / | HM |

| Nashat et al., 202228 | 103 (46) | / | Simple (4), moderate (53), severe (45) | Pilot study | Median age 39 y (16-73 y) | Huma Royal Brompton Hospital (RBH) ACHD therapeutic digital application (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and weight): 6 months | Information submitted via the smartphone application was transferred to a web-based clinical dashboard. | 18 flagged events during the 6-month observation period, and 50% of received early clinical intervention. | / | HM |

| Lin et al., 202119 | 47 (28) | 47 (29) | Acynotic (36), cyanotic (11) | Randomized controlled trial | 19.47 ± 2.87 (14.6-24.7 y) | Care & Organize Our Lifestyle (COOL) Passport—a mobile health care application: 12 months | Health Promotion Cloud and gameplay on interactive platforms in addition to COOL Passport. | No significant differences between the groups in any domain of disease knowledge or physical activity intensity. | COOL | PAP |

| Wearables | ||||||||||

| Jacobsen et al., 201630 | 14 (6) | / | Fontan | Pilot study | Median age 10 y (8-12 y) | FitBit Flex: home-based cardiac physical activity program: 12 weeks | Online group through the FitBit website | Significant change in calculated VO2max from baseline to the 12-week session (P < 0.001). The mean shuttle time improved from baseline to the 6-week session (P < 0.003). No improvement in HRQoL. | / | PAP |

| Fernie et al., 202329 | 9 (4) | / | Fontan | Pilot study | 13.5 ± 3.0 (7-31 y) | Garmin Vivosmart 4: home-based, individualized physical activity program: 12 months | Garmin online community | No pre-post difference in maximal or submaximal VO2, peak heart rate, or oxygen saturation. Significant pre-post increase in systolic blood pressure (P < 0.004) and minute ventilation (P < 0.012) at peak exercise. | Heart chargers | PAP |

| Amedro et al., 202416 | 70 (38) | 70 (35) | NYHA (%): I 35/63 (55), II 27/63 (43), III 1/63 (2) | Randomized controlled trial | 17.1. ± 3.5 (13-25 y) | Garmin Forerunner 25: “hybrid” cardiac rehabilitation program: 12 weeks | Nationwide health provider company (Stimulab) | Improved HRQoL, cardiovascular outcomes, disease knowledge, and the level of physical activity. | QUALIREHAB | CRP |

“/” denotes no given criteria.

AA, aortic atresia; ACHD, adult CHD; AS, aortic stenosis; CHD, congenital heart disease; CG, control group; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; CRP, cardiac rehabilitation program; DILV, double inlet left ventricle; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; ECG, electrocardiogram; ED, emergency department; eHealth, electronic health; EMR, electronic medical record; ES, enrolled subjects; HC, historical controls; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; HM, home monitoring; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; IG, intervention group; MA, mitral atresia; MS, mitral stenosis; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PA, pulmonary atresia; PAP, physical activity program; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; RACHS-1, risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery; SD, standard deviation; STRONGkids, Screening Tool Risk on Nutritional Status and Growth; SVTF, single ventricle task force; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; ToF, tetralogy of Fallot; VO2max, maximal oxygen uptake; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Based on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute study quality assessment tool,15 4 studies were rated as “good,” 7 studies as “fair,” and 5 studies, which showed a substantial risk of bias, were rated as “poor.” Detailed information on these quality ratings is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality assessment according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

| Study | Type | 1∗ | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality assessment tool for controlled intervention studies | ||||||||||||||||

| Black et al., 201426 | PS | X | X | NA | X | X | ✓ | NR | NR | NR | X | ✓ | X | X | X | Poor |

| Donati et al., 202121 | CT | X | X | NA | X | X | X | NR | NR | NR | X | ✓ | X | X | X | Poor |

| Cooper et al., 202018 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | NA | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | Fair |

| Bingler et al., 201817 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | NA | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | Good |

| Zhang et al., 202220 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NR | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | Fair |

| Amedro et al., 202416 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Good |

| Lin et al., 202119 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | NR | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Good |

| Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||||||||

| Kauw et al., 20196 | CSS/CS | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | NA | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | Fair |

| Koole et al., 201924 | CSS/CS | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | NA | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | Fair |

| Nederend et al., 202123 | CSS/CS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | Good |

| Stagg et al., 202325 | CSS/CS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | NA | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | Fair |

| Harahsheh et al., 201622 | CSS/CS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | NA | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | Fair |

| Quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group | ||||||||||||||||

| Nashat et al., 202228 | PS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | X | X | X | / | / | Poor |

| Fernie et al., 202329 | PS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | X | X | / | / | Poor |

| Jacobsen et al., 201630 | PS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | / | / | Fair |

| Khoury et al., 202027 | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | X | NA | / | / | Poor |

“✓” denotes yes, “X” denotes no, and “/” denotes no given criteria.

CCS/CS, cross-sectional and cohort studies; CT, clinical trials; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; PS, pilot studies; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Controlled intervention studies: 1 randomized; 2,3 treatment allocation; 4,5 blinding; 6 group similarity; 7,8 dropout; 9 adherence; 10 avoid other interventions; 11 outcome measures assessment; 12 power calculation; 13 prespecified outcomes; 14 intention-to-treat analysis. Observational cohort and cross-sectional studies: 1 research question; 2,3 study population; 4 eligibility criteria; 5 sample size justification; 6 exposure assessed before outcome; 7 timeframe; 8 level of exposure; 9 exposure measures and assessment; 10 repeated exposure assessment; 11 outcome measures; 12 blinding; 13 follow-up rate; 14 statistical analysis. Before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group: 1 study question; 2 eligibility criteria; 3 study participants representative of clinical populations of interest; 4 all eligible participants enrolled; 5 sample size; 6 intervention clearly described; 7 outcome measures clearly described, valid, and reliable; 8 blinding; 9 follow-up rate; 10 statistical analysis; 11 multiple outcome measures; 12 group-level interventions and individual-level outcome efforts.

Telehealth utility

Studies were grouped into 3 categories: teledevices, mobile applications, and wearables. Teledevices were defined as medical-grade and portable equipment used at home and connected to the care team such as saturation measurements, scales, electrocardiograms (ECGs), ergometers, or similar. Mobile applications, or mobile apps, are software programs specifically designed to run on mobile devices such as smartphones or tablets. They are either built for a specific platform (iOS or Android) using platform-specific programming languages and tools or accessed through a mobile device’s browser. Although teledevices and wearables are sometimes integrated with mobile applications, the classification in this context refers specifically to the app’s primary focus. In this review, wearables are mainly commercial devices with sensors using wrist-worn monitoring.

In total, 8 studies include teledevices such as digital scales,6,18,21,23,24,26 pulse oximeters,18,21,26 thermometers,21 digital and remote ECGs,6,21,23,24 blood pressure monitors,6,23,24 additional step-counters (Withings Move, activity, and sleep watch),23 or home TM monitoring devices such as the “ExpressMD” monitors.22 Different digital data transfer interfaces were used via Bluetooth or manually inserted data in smart-hub software applications on tablets or smartphones.

In particular, applications such as the “Health Mate App,”23 “cVitals,”6,24 or smart-hub software applications such as “E@syCare”21 served as data transfer modules. In addition, automated communication through the “Buddy Check Network”18 or online portals such as “WebPortal”22,26 was used. Direct transmission was also enabled to the electronic medical records of the patient.6,21,24 A study also integrated a TM ergometer (MedBike, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada), which featured a video game platform and provided live patient video/audio feeds, along with monitoring of electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, and power output. This setup facilitated remote medical supervision and adjustment of workload.27

Mobile applications were part of 5 studies. Applications such as the “Cardiac High Acuity Monitoring Program,”17 “Epic Care Companion,”25 and “Huma Royal Brompton Hospital” ACHD therapeutic digital application28 enabled the transfer of home monitoring data such as heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, weight, emergency department visits as well as hospitalizations, preselected patient-specific red flag warnings, and parental concerns via cellular service. Another smartphone-based social media application named “WeChat” allowed remote health education and feeding guidance.20

Lastly, the “Health Promotion Cloud” and gameplay on interactive platforms in combination with the “Care & Organize Our Lifestyle (COOL)” application offered a comprehensive home-based cardiac physical activity program including information and teaching about personal health management, medications, disease and treatment, sports, nutrition, mental health, and communication and interaction with fellow users.19

Wearables in terms of wrist-worn monitoring devices (eg, FitBit Flex, Garmin Vivosmart 4, and Garmin Forerunner 25) were used in 3 of 16 studies.16,29,30 The respective wrist-worn device providers generated an online community where study participants and medical staff could exchange information and challenge each other.

Health-related outcome measures

The included studies used different main outcome measures to investigate the effectiveness of the telehealth intervention or program. Maximum or peak oxygen consumption was used to measure physical performance in 4 studies via shuttle test run30 and cardiopulmonary exercise testing.16,27,29 Physical activity intensity was also assessed through questionnaires such as the Physical Activity Questionnaire and Taiwan Show-Card Version.19

Several questionnaires were analyzed to evaluate parameters such as health-related quality of life,16,24,30 health status, self-management, experienced safety, social and emotional problems, and physical restrictions (patient-reported outcome measure questionnaires were used: European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level, Patient Activation Measure, and Care-Related Quality of Life Survey for Chronic Heart Failure).24 Sleep and well-being assessment through questionnaires (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Psychological General Well-Being Index, Beck Depression Inventory, and Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory) was used in 1 study.21 The Leuven Knowledge Questionnaire for Congenital Heart Disease investigated disease knowledge in 2 studies.16,19

In addition, emergency department visits,24, 25, 26 intensive care unit stays,17 sudden death, adverse or flagged events,26,28 and general progression complications17,22 were tracked as the main outcomes in 8 included studies.

Infant growth17,18 and body weight20,22 were 2 outcome measures as well, and 1 study also reported albumin, prealbumin, and hemoglobin in infants.20 Lastly, 2 studies reported diagnosed arrhythmia recurrences6 and titration adaptations.23

Discussion

This systematic review outlined several interactive telehealth solutions for children and adults with CHD. Despite few studies showing nonsignificant effects,18,19,29 the majority indicate that telehealth solutions have a positive impact on cardiovascular health. Jacobsen et al.’s30 and Amedro et al.’s16 12-week programs showed significant improvements in maximum or peak oxygen consumption and physical activity levels, whereas the high-intensity interval training by Khoury et al.27 demonstrated increased exercise capacity in Fontan patients.

Of a total of 16 studies, home monitoring accounted for 11 studies for the largest share. It significantly improved outcomes for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and single ventricle disease, reducing complications, emergency department visits, and interstage growth failure.17,22,25,26 Infants monitored via smartphone or telehealth applications showed better nutritional status and fewer delays in care.20,28 For ACHD patients, telehealth solutions such as ECG monitoring reduced hospital visits and enabled early diagnosis of arrhythmias.6,23

These findings are in line with existing literature, reporting that home-based exercise programs are safe, practical, and serve as an effective alternative to supervised cardiac rehabilitation for patients with CHD of all ages.31 A recent review found that home monitoring with mHealth is beneficial for postpalliation patients.32 In addition, video conferencing has been shown to positively impact anxiety and health care utilization.32

In a study by Dodeja et al.,33 adults expressed high satisfaction with their telehealth experiences and reported feeling well-supported. Indeed, holistic cardiac rehabilitation programs and the use of mobile health significantly enhanced the health-related quality of life of patients.12,16,24 Another study using teledevices such as a pulse oximeter, thermometer, scale, and ECG connected to a smart hub improved patients’ overall well-being and sleep quality.21 In addition to the improvement in quality of life, a study also reported that the dropout rate in tertiary ACHD clinics declined after the introduction of TM consultations.34 Thus, telehealth permits greater accessibility to care, especially for patients with long travel distances. It provides them the same opportunities to attend examinations and eliminates the restriction to facility-based programs.35 In addition, integrating interactive real-time physiological measurements via health APIs instead of simply monitoring vital signs at home enhances the quality of care. Furthermore, older patients encountered minimal technical challenges, highlighting the accessibility and effectiveness of telehealth services across different age groups even more.33

Limitations

In this systematic review, multiple study designs regarding TM solutions in patients with CHD were examined. Therefore, heterogeneity in methodology and study populations was observed. The majority of the studies dealt with newborns and children requiring home monitoring. In addition, the quality of the studies was mostly rated as “fair” or “poor.” This could be due to the many pilot projects without control groups, the small study population, often short intervention periods, limited long-term follow-up data, and the new technologies. There is a high probability of publication bias, particularly for pilot studies, which are often conducted with low power and face significant challenges in being published.

Future research and clinical implications

Education forms a fundamental block in effectively integrating eHealth programs into primary care. To fully harness the potential of these technologies, specialized training for health care staff is essential. This training should focus on equipping staff to implement eHealth interventions, including live supervision through an integrated health API. Such initiatives pave the way for holistic and personalized care, enabling health care providers to offer more tailored treatments to diverse patient populations. It also promotes cooperation between staff, doctors, and patients. However, it is equally important to address the potential risks associated with eHealth, particularly regarding data security. Open discussions about these risks can help mitigate concerns, ensuring that patients and clinical staff are well informed and comfortable with eHealth solutions and live supervision.

To develop a realistic approach, paired with an ambitious and forward-looking vision supported by national and international collaboration as well as adequate governmental funding and investment, strategic objectives, structured positions, and billing systems must be established to minimize barriers to adopting and exploring innovative eHealth concepts.

By leveraging technology in these ways, not only can the effectiveness of treatments be enhanced, but equitable access to care can also be improved for patients in low-resource environments and underserved communities. Together, these initiatives support a more inclusive and effective health care system, positioning eHealth as a critical component of future primary care.

Due to the earlier discussed limitations, high-quality randomized controlled trials with overall holistic prevention projects for ACHD including real-time measurements via health APIs are even more important. As technology advances, randomized controlled trials can play a crucial role in addressing critical concerns around data security, usability, and patient engagement, thereby reinforcing the need for wider implementation and acceptance in clinical practice.

Especially the pilot projects, which mainly serve feasibility and initial evaluations and therefore still seem to be of low quality, could have great potential for new randomized studies. These would provide opportunities for promoting exercise and holistic approaches including nutrition, sleep, and stress coupled with personalized care and interventions to encourage targeted long-term behavior change and exercise promotion. With regard to populations of chronically ill patients such as those with CHD suffering from long-term morbidity and the disposition for comorbidities, it is essential to integrate prevention, especially physical activity, into the daily routine to improve health and well-being. Live supervision should, in this case, not lead to strict monitoring that could evoke possible anxiety or uncertainty, but should provide the opportunity for awareness and motivation, as well as reassurance, to help patients with CHD achieve lasting behavioral change and enjoy exercise. In particular, ACHD patients, who have been advised not to exercise for years, would benefit greatly from interactive telehealth solutions and education programs.

Conclusions

Interactive TM solutions appear to be an effective and practicable supplement to face-to-face appointments. They offer the opportunity to implement early prevention strategies, such as improving fitness or promoting a healthy lifestyle. This is particularly significant for populations of chronically ill patients, such as those with CHD, who face increasing long-term morbidity into adulthood. To ensure and expand medical care for these patients, the implementation of high-quality interactive telehealth solutions beyond home monitoring is essential.

Acknowledgments

Ethics Statement

This systematic review did not involve human participants, animals, or primary data collection.

Patient Consent

The authors confirm that patient consent is not applicable to this article.

Funding Sources

This work was funded by the Kinderherzen Fördergemeinschaft Deutsche Kinderherzzentren e.V.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Graphical Abstract.

References

- 1.Baumgartner H., De Backer J., Babu-Narayan S.V., et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563–645. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tutarel O. Acquired heart conditions in adults with congenital heart disease: a growing problem. Heart. 2014;100:1317–1321. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tutarel O., Kempny A., Alonso-Gonzalez R., et al. Congenital heart disease beyond the age of 60: emergence of a new population with high resource utilization, high morbidity, and high mortality. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:725–732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triedman J.K., Newburger J.W. Trends in congenital heart disease: the next decade. Circulation. 2016;133:2716–2733. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turakhia M.P., Kaiser D.W. Transforming the care of atrial fibrillation with mobile health. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2016;47:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s10840-016-0136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauw D., Koole M.A.C., Winter M.M., et al. Advantages of mobile health in the management of adult patients with congenital heart disease. Int J Med Inform. 2019;132 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.104011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borrelli N., Grimaldi N., Papaccioli G., et al. Telemedicine in adult congenital heart disease: usefulness of digital health technology in the assistance of critical patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:5775. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20105775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinhubl S.R., Muse E.D., Topol E.J. The emerging field of mobile health. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruining N., Caiani E., Chronaki C., Guzik P., van der Velde E. Acquisition and analysis of cardiovascular signals on smartphones: potential, pitfalls and perspectives: by the Task Force of the e-Cardiology Working Group of European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(suppl):4–13. doi: 10.1177/2047487314552604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner M.M., Mercer-Rosa L., Faerber J., et al. Association of a home monitoring program with interstage and stage 2 outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhasipol A., Sanjaroensuttikul N., Pornsuriyasak P., Yamwong S., Tangcharoen T. Efficiency of the home cardiac rehabilitation program for adults with complex congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018;13:952–958. doi: 10.1111/chd.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willinger L., Oberhoffer-Fritz R., Ewert P., Müller J. Digital Health Nudging to increase physical activity in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2023;262:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer M., Brudy L., Fuertes-Moure A., et al. E-health exercise intervention for pediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2021;233:163. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uman L.S. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:57–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Quality assessment tools. 2014. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools Available at:

- 16.Amedro P., Gavotto A., Huguet H., et al. Early hybrid cardiac rehabilitation in congenital heart disease: the QUALIREHAB trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1458–1473. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bingler M., Erickson L.A., Reid K.J., et al. Interstage outcomes in infants with single ventricle heart disease comparing home monitoring technology to three-ring binder documentation: a randomized crossover study. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018;9:305–314. doi: 10.1177/2150135118762401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper B.M., Marino B.S., Fleck D.A., et al. Telehealth home monitoring and postcardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin P.J., Fanjiang Y.Y., Wang J.K., et al. Long-term effectiveness of an mHealth-tailored physical activity intervention in youth with congenital heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:3494–3506. doi: 10.1111/jan.14924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q.L., Lei Y.Q., Liu J.F., Chen Q., Cao H. Telehealth education improves parental care ability and postoperative nutritional status of infants after CHD surgery: a prospective randomized controlled study. Paediatr Child Health. 2022;27:154–159. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxab094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donati M., Panicacci S., Ruiu A., et al. Exploiting biomedical sensors for a home monitoring system for paediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Technologies. 2021;9:56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harahsheh A.S., Hom L.A., Clauss S.B., et al. The impact of a designated cardiology team involving telemedicine home monitoring on the care of children with single-ventricle physiology after Norwood palliation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37:899–912. doi: 10.1007/s00246-016-1366-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nederend M., Zandstra T.E., Kiès P., et al. Potential of eHealth smart technology in optimization and monitoring of heart failure treatment in adults with systemic right ventricular failure. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2021;2:215–223. doi: 10.1093/ehjdh/ztab028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koole M.A.C., Kauw D., Winter M.M., et al. First real-world experience with mobile health telemonitoring in adult patients with congenital heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2019;27:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s12471-018-1201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stagg A., Giglia T.M., Gardner M.M., et al. Initial experience with telemedicine for interstage monitoring in infants with palliated congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2023;44:196–203. doi: 10.1007/s00246-022-02993-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black A.K., Sadanala U.K., Mascio C.E., Hornung C.A., Keller B.B. Challenges in implementing a pediatric cardiovascular home telehealth project. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:858–867. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khoury M., Phillips D.B., Wood P.W., et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in the paediatric Fontan population: development of a home-based high-intensity interval training programme. Cardiol Young. 2020;30:1409–1416. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nashat H., Habibi H., Heng E.L., et al. Patient monitoring and education over a tailored digital application platform for congenital heart disease: a feasibility pilot study. Int J Cardiol. 2022;362:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernie J.C., Wylie L., Schäfer M., et al. Pilot project: heart chargers—a successful model for a home-based physical activity program utilizing telemedicine for Fontan patients. Pediatr Cardiol. 2023;44:1506–1513. doi: 10.1007/s00246-023-03215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobsen R.M., Ginde S., Mussatto K., et al. Can a home-based cardiac physical activity program improve the physical function quality of life in children with Fontan circulation? Congenit Heart Dis. 2016;11:175–182. doi: 10.1111/chd.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer M., Brudy L., García-Cuenllas L., et al. Current state of home-based exercise interventions in patients with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Heart. 2020;106:333–341. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kauw D., Koole M.A.C., van Dorth J.R., et al. eHealth in patients with congenital heart disease: a review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018;16:627–634. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1508343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodeja A.K., Schreier M., Granger M., et al. Patient experience with telemedicine in adults with congenital heart disease. Telemed J E Health. 2023;29:1261–1265. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2022.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee M.G.Y., Russo J.J., Ward J., Wilson W.M., Grigg L.E. Impact of telehealth on failure to attend rates and patient re-engagement in adult congenital heart disease clinic. Heart Lung Circ. 2023;32:1354–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2023.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spence C., Khoo N., Mackie A., et al. Exploring the promise of telemedicine exercise interventions in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39:S346–S358. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2023.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]