Abstract

Despite significant progress, malaria remains a public health problem in many regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. This situation is partly explained by the mosquito’s resistance to insecticides and the emergence of parasite resistance to antimalarial drugs. Indeed, in spite of the various vectors’ controls, insecticide resistance emerges from multi-generational selection and poses worldwide concern. In parallel, artemisinin resistance unfortunately emerged independently in multiple countries in eastern Africa. Since 2014, artemisinin resistance has been observed in 6 countries in Africa and, more concerningly, the evidence from longitudinal molecular surveys in these countries suggests that it is spreading. While phenotypic evidence of treatment failure is still limited, the increasing reports of validated artemisinin resistance mutations are alarming. Unlike the emergence of artemisinin resistance in South-East Asia, our understanding of the genetic determinants of artemisinin resistance and our ability to sequence and map the spread of resistance are significantly greater. In addition to mosquito and parasite genetics affecting malaria evolution, many human individual variants have been identified that are associated with malaria protection, but the most important of all relates to the structure or function of red blood cells, the classical polymorphisms that causes sickle cell trait, α-thalassaemia, G6PD deficiency, and the major red cell blood group variants. In that biological complex context, there is a need to characterize the various genetic factors in Plasmodium falciparum, humans and mosquitoes that are potentially associated with resistance to antimalarial drugs and insecticides, and their involvement in the evolution, severity and transmission of malaria. In this direction, A comprehensive literature review was conducted to capture the objectives highlighted above. The advances in genomic surveillance and emerging genetic control strategies, such as gene drive technology were also considered in this review. We used search engines such as PubMed and Google scholar to retrieve articles useful to the objective of this paper and information on the knowledge of genetic factors and methods that contributed to malaria control were synthesized.

Keywords: Malaria, Genetic factors, Resistance, Transmission, Review

Background

Malaria is a multifactorial disease caused by the Plasmodium parasite with Plasmodium falciparum being the deadliest [1]. By 2023, the WHO African Region will have the highest malaria burden, accounting for 94% of malaria cases (around 246 million cases) and 95% of malaria deaths (569,000 deaths) worldwide [2]. This disease’s evolution is influenced by host, parasite, vector and genetics factors and also environmental and epigenetic influences [3–4]. Despite its scientific evolution and the various efforts currently undertaken, malaria still remains a worldwide major public health concern. The current fight against malaria involves prevention strategies including vector control with the use of insecticides, preventive therapy with antimalarial drugs, and case management based on current artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) [5]. However, the Anopheles vector resistance to insecticides and the P. falciparum resistance to antimalarials compromise this fight. In fact, P. falciparum has developed some resistance to the latest antimalarials considered to be the most effective [6]. Recently, artemisinin resistance has been reported across East and the Horn of Africa (EHoA), including Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan [7–15]. However, ACTs still remain efficacious in Africa nowadays. Given the heavy reliance on ACTs for health care in Africa, there is an urgent need to monitor and address the threat of parasite resistance to these therapeutic combinations. Due to the apparent rapid spread of certain resistance-associated mutations, action is needed before ACTs begin to fail in Africa. This resistance would be characterized by a decrease in the sensitivity of the ACTs. An alternative pharmaceutical solution is unlikely to be available in the near future and it is therefore necessary to preserve the therapeutic lifespan of these ACTs [16]. Insecticide resistance also hampers the fight against malaria and is controlled by one or more genes. These genes allow the mosquito to avoid contact with the toxic compound, to reduce its penetration, to increase its excretion or detoxification, and to modify the structure of the targets, therefore to reduce their affinity for the insecticide [17]. Over the past fifty years, the number of resistant insects has increased significantly and there are currently more than 500 species, a quarter of which are mosquitoes [18].

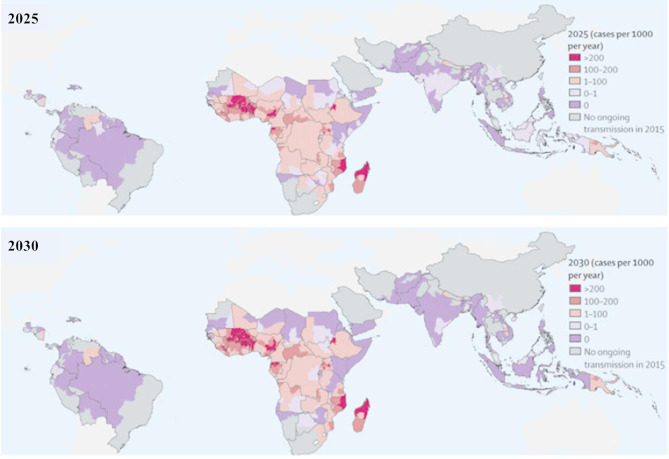

Several malaria vaccines are currently in clinical trials. Others including the RTS, S/AS01 is currently being used in three countries in sub-Saharan Africa [19]. The R21 vaccine has been tested by researchers in West Africa including Burkina Faso, and these two were respectively approved by WHO in 2021 and 2023 for the prevention of malaria in children, following the recommendations from the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization [20]. Unfortunately, these vaccines are not available for all ages where malaria is endemic. In fact, the vaccine is only deployed in children under five, one of the most vulnerable age groups. Vector control, treatment and chemotherapy (prevention and cases management) remain the main tools of control, but are confronted with resistance phenomena. In view of the challenge caused by resistance, it is therefore necessary to identify the factors, particularly genetic, that cause it and the methods that can contribute to their reduction. Figure 1 illustrates that the reduction in malaria transmission and burden can be accelerated over the next few years (2025 to 2030) with the increased coverage of current interventions and the absence of insecticide or antimalarial resistance that could compromise control.

Fig. 1.

Estimated incidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria from 2025–2030 by strengthening of existing interventions in the absence of loss of effectiveness due to resistance to antimalarials or insecticides. Adopted from Griffin et al., 2016 [21]

Genetic factors related to resistance and malaria transmission dynamic

Human genetic factors and malaria

Pharmacogenetics and resistance to plasmodium falciparum

Drugs induced outcomes are modulated in part by the genetic variability in genes encoding enzymes responsible for drug metabolism including cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes [22]. Almost all antimalarial drugs developed against P. falciparum are metabolized by these cytochrome P450 enzymes in the liver [23]. The efficacy of drugs therefore depends on these human factors, the human genetic heritage. The main enzymes involved in the metabolism of antimalarial drugs are cytochrome P450 enzymes with different variants such as CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 [24]. Among the cytochrome P450 genes CYP2C8 is involved in the metabolism of amodiaquine (AQ) [25] and has a high degree of polymorphism [26]. There are several variants in the CYP2C8 gene including CYP2C8*2, CYP2C8*3, CYP2C8*4 which have lower activities which can reduce the clearance of amodiaquine by up to 6 times [27] The CYP2C8*2 variant is highly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa and its presence is often considered to be one of the major risk factors for antimalarial drugs resistance of the P. falciparum parasite in Africa due to the genetic mutation observed at the level of this genetic variant [28]. AQ metabolism studies have showed that AQ metabolic activity is reduced by 50% for CYP2C8*2 and 85% for CYP2C8*3 (mutant type) compared to wild type [29]. The table below shows the parasite and human gene mutations associated with drug resistance.

Table 1.

Parasite and human molecular markers associated with parasite drug resistance [30]

| Antimalarial Drug |

Parasite molecular markers associated with drug resistance |

Human molecular markers associated with drug resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Quinine |

pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, S1034C, N1042D, D1246Y [31], pfmrp Y191, A437S [32] |

CYP3A4, CYP3A5 [33–34] |

| Halofantrine | Increased pfmdr1 copy number [35] | CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 [36] |

| Mefloquine |

pfcrt K76T, A220S, Q271E, N326S, I356T, R371I Increased pfmdr1 copy number, pfmdr1 N86Y [37] |

CYP3A4 [38] |

| Lumefantrine |

pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, S1034C, N1042D, D1246Y [39] Increased pfmdr1 copy number [40] |

CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 [41] |

| Chloroquine |

pfcrt K76T, K76N, K76I [42] pfmdr1 N86Y [43] |

CYP2C8, CYP3A4, and CYP3A5 [23] |

| Amodiaquine |

pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, S1034C, N1042D, D1246Y, pfcrt K72T [44] |

CYP2C8, CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 [45] |

| Piperaquine | Increased pfpm2 and pfpm3 copy numbers [46, 47] | CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 [48] |

| Pyronaridine |

pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, S1034C, N1042D, D1246Y, pfcrt K72T [49] |

CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 [50] |

| Primaquine | Not available | CYP1A2, CYP3A4, and monoamine oxidase [51] |

| Proguanil | pfdhfr S108N, N51I, and C59R and | CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 [52] |

| Pyrimethamine | pfdhfr S108N, N51I, C59R, 164 I164L, and A16V [53] | Not available |

| Sulfadoxine |

pfdhps S436F/A, A437G, K540E, A581G, and A613S/T [53] |

Not available |

| Artemisinin |

pfk13 C580Y, R539T, I543T, F446L, N458Y, P547L, |

CYP2B6, CYP3A4, and CYP2A6 [56] |

| Atovaquone |

pfcytb Y268S/C/N, M133I, L144S, G280D [57] |

Not available |

Erythrocyte/cellular and immune gene polymorphism on malaria infection

Examples of protective traits against malaria include hemoglobin variants, enzyme disorders, and erythrocyte membrane polymorphisms [58].Currently, knowledge of the genetic contribution to human resistance to malaria remains very incomplete. In fact, only about fifty genes yet have been tested, and it is very likely that there are many genes to be identified, that play an important role in human resistance to malaria [59].

Erythrocyte factors such as the absence of the Duffy antigen on the surface of red blood cells confer resistance to Plasmodium vivax [60]. Hemoglobinopathies, namely HbS, HbC, HbE, HbF, are responsible for the subject’s constitutional tolerance to P. falciparum during the erythrocyte stage of the cycle, thereby reducing malaria transmission [61] and the development of severe clinical signs of P. falciparum malaria [62]. A protective role of HbS and HbC against infection per se is consistent with the observation of the protection of the two mutant hemoglobins against all severe malaria syndromes including cerebral malaria and severe malaria anemia in different countries and in diverse populations [63].

RBC abnormalities cell cytoskeleton, notably ovalocytosis and elliptocytosis also reduce the expansion of P. falciparum and Plasmodium vivax strains at the erythrocyte level [64]. Also, blood group “O” protects against severe forms by inhibiting the formation of rosettes [65–66]. Non-erythrocyte factors such as Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) groups, immune response polymorphism that reduce malaria transmission and G-6-PD deficiency confer protection against asymptomatic malaria by reducing the parasite rate in deficient individuals and heterozygous females [67]. Pyruvate kinase (PK) is another enzyme that is necessary for the cell to produce energy. PK deficiency, which is inherited recessively, is caused by a mutation in the PKLR gene. Although an in vitro study in humans confirmed protection against P. falciparum invasion and growth in PK-deficient erythrocytes [68], a recent study in mice has highlighted a new lineage deficient in PK, but sensitive to malaria infection [69].

Haptoglobin, encoded by the HP gene, is not strictly an erythrocyte protein. This plasma protein is able to bind to hemoglobin released into the plasma during hemolysis of infected erythrocytes, thus preventing oxidative damage to tissues caused by hemoglobin. The analyses allowed the characterization of three different phenotypes corresponding to three mutant forms, namely haptoglobin 1–1, 1–2 and 2–2. Each of these different phenotypes exerts specific modulations of oxidative stress, hemoglobin recycling and immune function [70]. Indeed, the 1–1 phenotype has been associated with susceptibility to severe forms of malaria in two studies [71–72]. In addition, haptoglobin 2–2 was recently associated with a reduction in clinical episodes associated with malaria in Kenyan children [73]. In this study the authors interestingly noted an interaction of the age of the children with the protective effect of haptoglobin 2–2 against clinical forms and would also be responsible for greater oxidative stress caused by free hemoglobin in the plasma. This stress would promote the acquisition of antimalaria immunity [74].Polymorphisms in genes encoding innate immune factors can increase or decrease susceptibility and clinical manifestations [75]. The results of a study carried out in Burkina Faso showed the influence of certain polymorphisms affecting resistance to malaria through their effect on the acquired immune response thus opening the way to a better understanding of the genetic control of the immune response to fight against malaria [76]. Several human immunological genes have been implicated in certain clinical manifestations of malaria [77].

Studies on the scale of the human genome have made it possible to discover several loci that control uncomplicated malaria and parasitemia due to P. falciparum infection. In fact, a study carried out in Burkina Faso showed previous loci on chromosomes 17p12, involved in malaria resistance in individuals. Studies have also confirmed the presence of previous loci on chromosomes 6p21.3 and 5q31that control malaria resistance. The results of this study therefore demonstrate once again that genetic variation within human genes strongly influences parasitemia. This could lead to the development of new therapeutic strategies [78].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) influence on plasmodium falciparum malaria infection during pregnancy

Genetic predisposition is involved in susceptibility to malaria during pregnancy and in its clinical manifestation. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are thought to influence gene regulation, including that of the innate immune response. One study estimated that 30% of human genes are regulated by miRNAs, which are intimately involved in immune regulation in general [79]. A study conducted in Ghana among antenatal care participants and first-time mothers during childbirth also showed that the miRNA-146a polymorphism increases the risk of malaria during pregnancy [80–81, 73, 74]. Indeed, in these two groups, two out of three women were heterozygous or homozygous for miRNA-146a rs2910164 and homozygosity in antenatal care participants conferred an increased risk of infection (95% CI, 1.3 to 4.0 0), which was also pronounce in primigravidas (95% CI, 1.6 to 26). Similarly, homozygosity for miRNA‑146a rs2910164 in primiparas increased the risk of placental events due to P. falciparum infection almost sixfold (95% CI, 2.1–18) [80, 81]. These results suggest that miRNA-146a is involved in protective immunity against malaria. The genetic factors of P. falciparum associated with resistance to antimalarial drugs, which have been the subject of several studies, are thought to be responsible for therapeutic failures.

Parasite genetic factors

Genetic polymorphism of plasmodium falciparum and malaria transmission dynamic

Drug resistance affects malaria transmission and this level of transmission can influence the risk of malaria spread [82]. The number of strains circulating in a population and likelihood of combining genetic material during the sexual reproduction of the parasite increases with high transmission. This increases the risk of losing potential resistance mutations and thus increases competition with other parasite strains. This resistance can spread when the risk of transmission of parasites that are less sensitive to antimalarial drugs is much higher [83] and they are subsequently transmitted and promote an increase in gametocyte carriage [84]. Exposure to antimalarial drugs of parasites to which they are not fully sensitive promotes their multiplication and transmission. Any delay in detecting of resistance to antimalarial drugs therefore allows the spread of resistant parasites and the achievement of high prevalence levels. Several studies have demonstrated the impact of resistance to antimalarial drugs on malaria transmission. Indeed, the results of one study showed that parasites resistant to chloroquine were more infectious to mosquitoes, suggesting that drug resistance increases transmission [43]. To investigate the impact of this resistance on transmission in one study, mosquitoes were fed the blood of Gambian children with malaria and the level of transmission of drug-susceptible and drug-resistant parasites was compared. This comparison showed that mosquito infection was significantly greater after feeding on blood containing mutant gametocytes (pfcrt76T, pfmdr186Y) compared to blood containing wild-type gametocytes [85]. Pfcrt and pfmdr1 are genes encoding P. falciparum membrane proteins. In another study also conducted in Gambia, children infected with pfcrt76T mutant parasite strains had higher gametocyte densities than those with wild pfcrt76K parasite strains [86]. Analysis of samples from Sudan also showed that gametocyte production was higher in pfcrt76T or pfmdr1 86Y mutant infections than in wild types [87]. Thus, for these polymorphisms, increased transmission could have an effect on the fitness in erythrocyte parasites, thereby contributing to the spread of resistance [88]. In Senegal, during an in vivo study on the chemosensitivity of P. falciparum [53], post-therapeutic gametocythemia to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine was higher in patients with chemoresistant infections than those with chemosensitive infections. On day 7 of this study, after treatment with chloroquine, individuals with resistant parasite strains had 4 times more infectivity than subjects with sensitive parasite strains. Thus, this study showed that the number of gametocytes was positively correlated with the level of resistance. These results have been confirmed in Gambia [89]. All of these studies show that Plasmodium resistance to antimalarial drugs promotes the transmission of malaria. Antimalarial drugs resistance too, thought to be responsible for treatment failure, plays a role in malaria transmission.

Polymorphisms of P. falciparum membrane surface antigens are also associated with clinical signs of malaria. There are several parasite polymorphism markers, but msp1 and msp2 are the most appropriate for diversity analysis because they are involved in several host-parasite interaction processes [90]. A study showed high levels of genetic diversity and mixed-strain infections in P. falciparum populations in the Chewaka district of Ethiopia associated with high malaria endemicity and transmission [91]. In Burkina Faso, a study also shows that the genetic diversity of P. falciparum influences the severity of certain malaria symptoms, and thus indicates the existence of within-host competition in genetically diverse P. falciparum [92]. These two markers (msp-1, msp-2) make it possible to establish a relationship between the polymorphism of the parasite and the most commonly observed and measurable signs of malaria such as temperature, parasitemia and hemoglobin level [93]. Several studies have demonstrated this association between the prevalence of specific clones, allelic families of msp-1 (K1, Mad20, Ro33), msp-2 (FC27,3D7) of the parasite and the clinical signs of the disease [94–95]. Indeed, the mad20 and k1 allelic families increase the risk of developing symptomatic malaria [95]. The severity of malaria would also be related to the prevalence of specific types of msp-2 clones and one study indicated a high frequency of the FC27 genotype rather in asymptomatic carriers in a holoendemic region of Dakar in a study [96]. A study in Gabon showed a higher frequency of the 3D7 alle in asymptomatic than symptomatic infections. A predominance of 3D7 genotypes was also observed in severe cases without severe anemia when compared to severe cases with severe anemia in Burkina Faso [93]. However, analysis of the results showed that the frequency of 3D7 parasite forms did not differ between severe and non-severe cases in another study in Burkina Faso [97]. Knowledge of the relationship between the genetic diversity of the parasite and the symptomatology of malaria remains limited due to the divergent conclusions of several studies conducted in different localities [92]. These two polymorphic genes are used to study the intensity of transmission in a locality and the degree of the polymorphism is highly correlated with malaria transmission. Genetic markers in mosquitoes associated with resistance to insecticides have been identified, hampering vector control using these insecticides.

Mosquito genetic factors

Anopheles genetic mutations and insecticide resistance

Almost all chemical insecticides are neurotoxic disrupting the insect’s nervous system, causing its paralysis and then its death. Once the mosquito comes into contact with the insecticide, the active molecule has to penetrate its body and be transported to its target in order to interact with it (Fig. 2A). Any mechanism that alters this sequence of events could lead to mosquito resistance (Fig. 2B). In other words, resistance can be defined as any mechanism that allows an individual to survive doses of toxic substances that are lethal to the majority of individuals in a normal population of the same species. Resistant mosquitoes have been shown to be much more favored in the presence of insecticides thus increasing their survival [98]. Two major resistance mechanisms are commonly observed. These are metabolic resistance (Glutathione-S-Transferase, esterase, P450 monooxygenase), three classes of enzymes involved in the detoxification of the different families of insecticides used for vector control [99–102] and target site modification (acetylcholinesterase (Ace1-R); Knock down resistance (Kdr)) [103–104]. This resistance due to mutations in the genes encoding these enzymes is characterized by a reduction in the affinity between the membrane proteins of the neurons and the insecticides. Indeed, the Anopheles funestus group (2016, 2017, 2018) consistently showed some resistance to pyrethroids and molecular analyses revealed that resistance was associated with massive overexpression of the cytochrome P450 genes CYP6P9a and CYP6P9b and fixation of the CYP6P9a_R resistance allele in this population in 2016 (100%) as opposed to 2002 (5%) [105]. A field trial in Tanzania found that pyrethroid resistance reduced the efficacy of pyrethroid-based LLINs impacting malaria transmission [106].

Fig. 2.

Mode of action of an insecticide on a sensitive (A) and resistant (B) insect, adapted from Thesis by Malal Mamadou Diop. Influence of the kdr mutation (L1014F) on the behavioral response of Anopheles gambiae to pyrethroid insecticides. Zoology of invertebrates. University of Montpellier, 2015. (source: https://hal.science/tel-01374896)

Target site modification, most commonly through the Kdr effect, is associated with widespread resistance to DDT (dichlorodiphenyl-trichlroethane) and to pyrethroids in An. Gambiae sl. This resistance is associated with two-point mutations of amino acids specifically at position 1014 of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene, resulting in either a substitution of leucine for phenylalanine (L1014F) and a substitution of leucine for serine (L1014S). L1014F is more common in West Africa and L1014S in East Africa. L1014F and L1014S have been characterized in several countries, notably in Benin [107], in Ivory Coast [108–109], in Burkina Faso [110], in Cameroon [111], in Gabon [112] and in Uganda [113]. Many studies have been conducted on L995F (L1014F) and its effects on mosquito longevity, fecundity, vector competence and behavioral response of the mosquito have been observed [114–118]. The low susceptibility observed suggests that other resistance mechanisms may be involved [105]. Loss of efficacy of all long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), including piperinyl butoxide (PBO) was observed in a study in Mozambique [105]. Resistance to insecticides, which compromises vector and larval control, increases mosquito reproduction leading to increase transmission [119]. A study in Burkina Faso (West Africa) found that increased resistance in Anopheles gambiae negatively affected the efficacy of pyrethroid-only bed nets [120]. This mosquito resistance to insecticides threatens the fight against malaria and unfortunately, few pharmaceutical companies have invested in this type of research over the past thirty years, and few newer insecticide molecules have been brought to market [121–122].

Factors of resistance spread

Population movement (travel, refugees, transhumance, etc.) is a factor favoring the spread of resistance. The movement of infected individuals from an area where resistance to an antimalarial drug is prevalent to another area where it does not exist leads to the spread of resistant strains in the host area. This phenomenon has played a critical role in the spread of chloroquine-resistance [123–124]. Genetic recombination in mosquitoes also promotes the dissemination of resistant genes [125]. In addition, certain species may be more favorable to the transmission of resistant strains than others. This is the case with Anopheles balabacensi which has proven to be a good vector for the transmission of chloroquine-resistant strains in Southeast Asia [123–124]. Genetic methods could be a promising way of combating malaria.

Genetic methods of combating malaria

Genetically modified mosquito and transmission reduction

Mosquitoes can be genetically modified using two different technologies. The first method, paratransgenesis, involves infecting mosquitoes with bacteria that prevent them from transmitting malaria [126]. This method does not harm the mosquito. It is important not to eliminate or harm mosquitoes, because they pollinate many plants and serve as food for animals such as bats, birds and reptiles.This method aims to increase the resistance (immunity) of the vector to the Plasmodium and to develop or create refractory Anopheles, that are incapable of ensuring the sporogonic development of the Plasmodium; to develop Anopheles that would produce substances toxic to the Plasmodium, whether in Anopheles or in humans [127]. Dimopoulos’ team’s observations suggest that mosquitoes have not evolved a specific defense system against Plasmodium [128–130], but rather use their antimicrobial systems. The team’s idea would be to activate the immune system of anopheline mosquitoes by exposing them to microbes (not transmissible to humans), to specifically increase their ability to kill the parasite if they encounter it. The second method is to genetically modify the mosquitoes themselves, focusing on gene drives, a set of genetic systems that guarantee the transmission of genes to each generation. There are two types of gene drives. One aims to reduce the size of the vector population and is known as population elimination. The other aims to prevent the mosquito from transmitting malaria.Indeed, several research studies have been devoted to genetically engineering mosquito resistance to control malaria transmission [131–133]. Laboratory studies have demonstrated that gene drive techniques can either effectively modify Anopheles mosquitoes to render them incapable of transmitting malaria parasites [134], or to introduce lethal gene sequences that can quickly suppress or significantly reduce entire populations of these mosquitoes in a rapid time [135–137].

The genetic forcing method uses a Cas9 protein (CRISPR associated protein), a genetic ‘pair of scissors’ coupled to gRNA complementary to the target DNA sequence, which recognizes and cuts the target DNA sequence by around 12 to 40 bp in the host genome. After this cut, two possible pathways can be reproduced. The first is for the cellular machinery to repair the cut, generally inducing a mutation (Fig. 31). The second route consists of using a DNA sequence corresponding to the cut site and containing a gene of interest in the middle, and together with the Cas9- gRNA system, this sequence of interest is inserted at the desired location (Fig. 3)2. The cell’s repair machinery can then use the intact chromosome as a repair template, enabling the gene to be copied to the chromosome where it was absent [138].

Fig. 3.

1 DNA molecular mechanism of Gene Drive and 2 « Gene Drive » favouring the propagation of genetic elements (A) within populations than predicted by Mendelian segregation laws (B), Adopted from Eissenberg [139]

U.S. researchers genetically engineered male and female Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes by choosing to disrupt a gene known as femaleless (fle), which controls sexual development in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes [140]. This gene is present in both sexes, but it is only active in females. This genetic modification called Ifegenia therefore only kills modified females. The latter therefore all die at the laboratory stage while the males survive. Once released into the wild, they can therefore mate with wild females and spread Ifegenia. The offspring inherit this genetic modification and thus, the female population decreases from generation to generation [141]. Burkina Faso is the country that could disseminate the first mosquitoes resulting from gene drives led by researchers of Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé (IRSS) through the Target Malaria project, financed among others by the Bill and Melinda Gate Foundation aimed at developing genetically modified male mosquitoes. In July 2019, they carried out the first release of sterile and non-transgenic genetically modified hemizygous males into the Anopheles coluzzii population in Burkina Faso. This study aimed to determine the potential adaptation cost associated with transgenes and to gather important information on the dynamics of these transgene-carrying mosquitoes, which is critical for the next stages of development. Mathematical estimates confirmed that the transgenic males in this study had a lower survival rate and were less mobile than wild-type individuals. These results provide information on the fitness and behavior of released genetically modified males that will inform future releases of more effective strains of the Anopheles gambiae complex [142].

Studies have shown that Anopheles gambiae has a double sex gene (Agdsx) encoding dsx-female (AgdsxF) and dsx-male (AgdsxM), which control the differentiation of the two sexes respectively (Fig. 4a). The female transcript, unlike the male transcript, contains an exon (exon 5) whose sequence is highly conserved in all the Anopheles mosquitoes analyzed in this study (Fig. 4b). Targeted CRISPR-Cas9, ‘genetic scissors’, disruption of the intron 4-exon 5 boundary to block the formation of functional AgdsxF did not affect male evolution or fertility, but females homozygous for the disrupted allele showed an intersex phenotype and complete sterility [143]. A CRISPR-Cas9 gene drive constructed, targeting the same sequence spread rapidly in mosquitoes, reaching a frequency of 100% within 7 to 11 generations and progressively reducing egg production until the population collapsed [144]. This study showed that males carrying the homozygous dsxF- null mutation showed wild-type levels of fertility with reference to oviposition and hatching of larvae per mated female, as did heterozygous dsxF-/- female mosquitoes (Fig. 4.c). The XX dsxF-/- intersex females, although attracted to the anaesthetised mice in the study, were unable to take a blood meal and did not produce eggs. The dsxF-/- phenotype in females indicates that exon 5 of dsx plays a fundamental role in the sexual differentiation pathway of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, and therefore ~suggests that its sequence may represent a suitable target for population suppression.

Fig. 4.

(a) schematic of male and female-specific dsx transcripts and the gRNA sequence used to target the gene (grey), (b) sequence alignment of the dsx intron 4-exon 5 boundary in six species of the Anopheles gambiae complex, (c) Diagnostic by PCR (DSB, double strand break) using a set of primers (blue arrows in c) to distinguish the wild-type allele and the dsxF allele in homozygous (dsxF-/-), heterozygous (dsxF+/-) and wild-type (dsxF+/+) individuals. A source of Cas9 and a single-guide RNA (gRNA) was injected into A. gambiae embryos, designed to recognise and cut a sequence straddling the intron 4-exon 5 boundary, in combination with the template for homology-directed repair (HDR) to insert an GFP transcription unit, adapted from Kyros Kyrou et al., 2018 [144]

This method could be effective in reducing or eliminating the species of mosquito transmitting P. falciparum. Criticism could be levelled at the role of these mosquitoes in the environment. There are 800 species of mosquitoes, 30 to 40 of which are malaria vectors [145]. Nature would therefore benefit from the elimination of a few species of mosquitoes that are potential vectors of Plasmodium compared with the considerable mortality of the human species. However, a mosquito vector may be an important element in the food chain or an important pollinator in an ecosystem. It may therefore be more appropriate to carry out local studies or impact assessments before using these control methods.

Transgenic mosquito and protective vaccine via saliva

Speaking of transgenic mosquitoes, one study aimed to introduce a gene coding for a pathogenic protein into the chromosome of a mosquito, so that it would express this protein in its saliva and inject it into human beings during the blood-meal process. The host then develops antibodies against the recombinant protein. If transgenic mosquitoes containing a vaccine protein in their saliva against a disease are released in an area where the disease is widespread, people bitten daily by these mosquitoes will develop antibodies against the vaccine protein. In this case, the whole community will be vaccinated against the disease [146] and mosquitoes act as vaccinators [127].

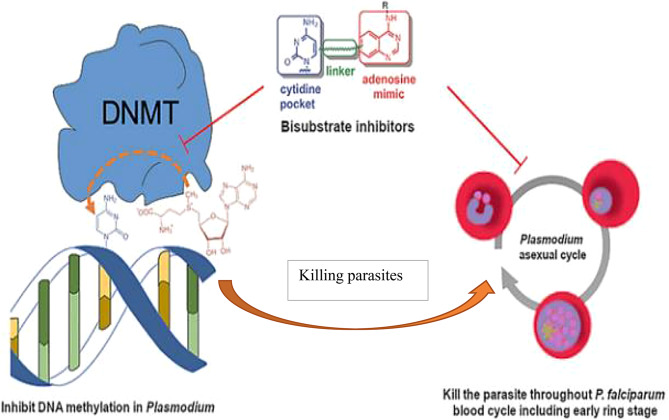

Epigenetic and the fight against malaria

In the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, epigenetic gene regulation governs the specific biology of the parasite as it develops within the human host and mosquito vector. Epigenetic modifications confer phenotypic plasticity, characterizing its proliferation and its progression through the various stages of its life cycle. Researchers in 2019 highlighted the importance of epigenetic modifications of DNA in the life cycle of the parasite [147]. It was therefore natural for researchers to work together to identify molecules capable of blocking DNA methylation and killing parasites (Fig. 5). They have identified molecules capable of inhibiting DNA methylation and effectively killing the P. falciparum parasite, even the most resistant [147]. The study results showed that blocking methylation is an effective strategy to combat malaria. The Identification of cytosine DNA methylation [148]and more recently hydroxymethylation [149–150] in P. falciparum makes this modification a potential drug target for the development of new antimalarial drugs to effectively malaria control.

Fig. 5.

Reduction of DNA methylation in the parasite for control, adapted from Nardella et al. 2020 [147]

Strategies to control resistance

Strategies to control resistance to antimalarial drugs

An effective Strategy against the threat of antimalarial resistance must be based on a good understanding of the factors that influence its emergence and spread. There are two stages in the emergence of the resistant parasite. The first stage corresponds to a random genetic event that renders the parasite less sensitive to a drug, and the second corresponds to the survival, selection and possible proliferation of parasites carrying one or more mutations that confer a degree of protection against the effects of a given drug [20]. The Strategy to combat Antimalarial Drug Resistance in Africa must build on the lessons learned from previous global plans and complement existing strategies [151]. Among these plans, the Global Plan to contain Artemisinin Resistance [152] and the Strategy for the elimination of malaria in the Greater Mekong sub-region [153] highlight the need for adequate surveillance, strong regional collaboration, participation11 of a broad group of stakeholders, including national malaria programs and communities, and sustainable financing. There is also a need to improve awareness and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance phenomena through effective communication, adequate education and training. Resistance of malaria parasites to antimalarial drugs is a major challenge, and a threat to most malaria control programs. Although the problem of drug-resistant malaria is global, it is severe in Africa. One Strategy that has recently received much attention is the combination of antimalarial drugs, such as mefloquine, SP or amodiaquine, with an artemisinin derivative [154]. Artemisinin-based drugs are very effective, acting quickly and on a greater number of developmental stages of the parasite. This action appears to produce two notable results. First, artemisinin compounds are used in combination with a longer-acting antimalarial drug and this significantly reduces the likelihood that parasites will survive the initial treatment and be exposed to suboptimal levels of the long-acting drug [155–156]. Second, the use of artemisinin has been shown to reduce gametogenesis by 8–18 times [157]. This reduces the likelihood that gametocytes carrying resistance genes will be transmitted and can potentially reduce malaria transmission rates. However, comparative studies on the effect of treatment with Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine (DP) on microscopic residual gametocytes have produced contradictory results [158–159]. Some studies show an increased risk of gametocyte carriage after treatment with AL [158], while others suggest that AL has a noticeable effect on gametocyte carriage compared with DP [160]. Gametocyte dynamics vary from region to region and would influence the impact of treatment on gametocyte carriage [161]. Tests would therefore be necessary to select an excellent ACT in terms of gametocytocidal efficacy and an additional gametocytocidal drug in combination with the ACT in order to block malaria transmission more effectively in localities where malaria endemicity is high [161]. It is necessary to continuously search for mutations in the parasite genome to identify possible mutations at antimalarial drug target sites and to validate these mutations as molecular markers of resistance or not. This approach will allow early detection of resistant parasite strains, leading to the rapid implementation of containment strategies to prevent the global spread of resistant parasite strains [30].

Strategies to control resistance to insecticides

Given the decreasing sensitivity of insecticides, it would be important to consider the rotation of different families of insecticides with different modes of action, the mosaic strategy involving the spatial alternation of two or more insecticides and the mixing of two or more insecticides with different modes of action [162]. Pyrethroid-piperonyl butoxide (PBO) nets should be considered in localities where pyrethroid resistance has been confirmed in the main malaria vectors [163]. The best evidence for the super efficacy of pyrethroid-PBO nets comes from areas with high resistance (< 30% mortality), and there was very little evidence of improved performance in areas with moderate or low levels of resistance [164]. This control could also be carried out as part of an integrated approach, taking into account environmental sanitation and the use of impregnated mosquito nets [165]. In addition, regular monitoring of the susceptibility of target populations and any resistance mechanisms involved is essential and should be an integral part of any vector control programme [166].

Conclusion

The genes for resistance to antimalarial drugs and insecticides observed in Plasmodium and the mosquitoe respectively over the last twenty years represent a real challenge in the global fight against malaria. Mutations in human genes coding for enzymes involved in antimalarial drug metabolism, notably cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, also contribute to the emergence of parasite resistance to these drugs, and are associated with therapeutic failure. Effective monitoring of the emergence and evolution of resistance is necessary for the control or elimination of malaria, which kills thousands of people every year, particularly children. Genetic methods would be effective in controlling malaria.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AQ

Amodiaquine

- Pfcrt

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- Pfmdr1

Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance 1

- CRISPR

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats”

- DDT

Dichlorodiphenyl-trichlroethane

- Kdr

Knock down resistance

- Msp

Merozoite surface proteins

- miRNA

microRNA

- PBO

Piperinyl butoxide

- ACTs

Artemisinin-based combination

Author contributions

Manuscript drafting: SN, IS, FWD, ABT, SB. S, AB and JS. Critical revision: GDA, MN, AAZ, SS, SS, NO, SSS, HS, RI, N Y.G.T, DO.A. Z, JY, FC. A.K, CT, AZ, NIT, OO, DZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. They agreed to submit it to the current journal and gave their final approval to the version to be published.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stratton L, O’Neill MS, Kruk ME, Bell ML. The persistent problem of malaria: addressing the fundamental causes of a global killer. Soc Sci Med. 2008. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Regional data and trends briefing kit world malaria. World Malar Rep. 2022;2022(no December):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ararat-Sarria M, Patarroyo MA, Curtidor H. Parasite-related genetic and epigenetic aspects and host factors influencing plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rono MK, et al. Adaptation of plasmodium falciparum to its transmission environment. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018. 10.1038/s41559-017-0419-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tizifa TA, Kabaghe AN, McCann RS, van den Berg H, Van Vugt M, Phiri KS. Prevention efforts for malaria. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018. 10.1007/s40475-018-0133-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pradines B, Dormoi J, Briolant S, Bogreau H, Rogier C. La résistance aux antipaludiques. Rev. Francoph. des Lab. 2010;422:51–62. 10.1016/s1773-035x(10)70510-4

- 7.Uwimana A, et al. Emergence and clonal expansion of in vitro artemisinin-resistant plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H mutant parasites in Rwanda. Nat Med. 2020. 10.1038/s41591-020-1005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conrad MD, et al. Evolution of partial resistance to artemisinins in malaria parasites in Uganda. N Engl J Med. 2023. 10.1056/nejmoa2211803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser KA, et al. Describing the current status of plasmodium falciparum population structure and drug resistance within Mainland Tanzania using molecular inversion probes. Mol Ecol. 2021. 10.1111/mec.15706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owoloye A, Olufemi M, Idowu ET, Oyebola KM. Prevalence of potential mediators of Artemisinin resistance in African isolates of plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2021. 10.1186/s12936-021-03987-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fola AA, et al. Plasmodium falciparum resistant to Artemisinin and diagnostics have emerged in Ethiopia. Nat Microbiol. 2023. 10.1038/s41564-023-01461-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mihreteab S, et al. Increasing prevalence of Artemisinin-Resistant HRP2-Negative malaria in Eritrea. N Engl J Med. 2023. 10.1056/nejmoa2210956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jalei AA, Na-Bangchang K, Muhamad P, Chaijaroenkul W. Monitoring antimalarial drug-resistance markers in Somalia. Parasites Hosts Dis. 2023. 10.3347/PHD.22140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamed AO, et al. Assessment of plasmodium falciparum drug resistance molecular markers from the blue nile State, Southeast Sudan. Malar J. 2020. 10.1186/s12936-020-03165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De la Fuente IM, et al. Screening for K13-Propeller mutations associated with Artemisinin resistance in plasmodium falciparum in Yambio County (Western Equatoria State, South Sudan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023. 10.4269/ajtmh.23-0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.OMS. Informe mundial sobre La malaria 2020. OMS. 2020.

- 17.Liu N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Ann Rev Entomol. 2015. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui JA, et al. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: challenges and control strategies. Front Physiol. 2023. 10.3389/fphys.2022.1112278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan AB, Winskill P, Ghani AC. Estimated impact of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine allocation strategies in sub-Saharan Africa: A modelling study. PLoS Med. 2020. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1003377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.OMS, Stratégie de riposte face à la résistance aux antipaludiques en Afrique. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1492767/retrieve

- 21.Griffin JT, et al. Potential for reduction of burden and local elimination of malaria by reducing plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li XQ, Björkman A, Andersson TB, Gustafsson LL, Masimirembwa CM. Identification of human cytochrome P450s that metabolise anti-parasitic drugs and predictions of in vivo drug hepatic clearance from in vitro data. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003. 10.1007/s00228-003-0636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redlich G, et al. Distinction between human cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms and identification of new phosphorylation sites by mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2008. 10.1021/pr800231w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jullien V, Ogutu B, Juma E, Carn G, Obonyo C, Kiechel JR. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic considerations of amodiaquine and desethylamodiaquine in Kenyan adults with uncomplicated malaria receiving artesunate-amodiaquine combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010. 10.1128/AAC.01496-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marwa KJ, Schmidt T, Sjögren M, Minzi OMS, Kamugisha E, Swedberg G. Cytochrome P450 single nucleotide polymorphisms in an Indigenous Tanzanian population: A concern about the metabolism of artemisinin-based combinations. Malar J. 2014. 10.1186/1475-2875-13-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brasseur P. Tolérance de l'amodiaquine [Tolerance of amodiaquine]. Med Trop (Mars). 2007 Jun;67(3):288–90. French. PMID: 17784684. [PubMed]

- 28.Paganotti GM, et al. Distribution of human CYP2C8*2 allele in three different African populations. Malar J. 2012. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai D, et al. Polymorphisms in human CYP2C8 decrease metabolism of the anticancer drug Paclitaxel and arachidonic acid. Pharmacogenetics. 2001. 10.1097/00008571-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodoameda P, Duah-Quashie NO, Ben Quashie N. Assessing the roles of molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistance and the host pharmacogenetics in drug-Resistant malaria. J Trop Med. 2022;2022. 10.1155/2022/3492696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Durand R, Jafari S, Vauzelle J, Delabre JF, Jesic Z, Bras JL. Analysis of Pfcrt point mutations and chloroquine susceptibility in isolates of plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001. 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00247-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raj DK, et al. Disruption of a plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance-associated protein (PfMRP) alters its fitness and transport of antimalarial drugs and glutathione. J Biol Chem. 2009. 10.1074/jbc.M806944200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirghani RA, Hellgren U, Bertilsson L, Gustafsson LL, Ericsson Ö. Metabolism and elimination of quinine in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003. 10.1007/s00228-003-0637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukonzo JK, Waako P, Ogwal-Okeng J, Gustafsson LL, Aklillu E. Genetic variations in abcb1 and cyp3a5 as well as sex influence quinine disposition among Ugandans. Ther Drug Monit. 2010. 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181da79d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidhu ABS, Uhlemann AC, Valderramos SG, Valderramos JC, Krishna S, Fidock DA. Decreasing pfmdr1 copy number in plasmodium falciparum malaria heightens susceptibility to mefloquine, lumefantrine, halofantrine, quinine, and Artemisinin. J Infect Dis. 2006. 10.1086/507115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baune B, et al. Halofantrine metabolism in microsomes in man: major role of CYP 3A4 and CYP 3A5. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010. 10.1211/0022357991772628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muhamad P, et al. Polymorphisms of molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistance and relationship with artesunate-mefloquine combination therapy in patients with uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011. 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fontaine SM, Hoyer PB, Halpert JR, Sipes IG. Role of induction of specific hepatic cytochrome P450 isoforms in epoxidation of 4-vinylcyclohexene. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001. [PubMed]

- 39.Sisowath C, et al. The role of pfmdr1 in plasmodium falciparum tolerance to artemether-lumefantrine in Africa. Trop Med Int Heal. 2007. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mungthin M, et al. Association between the pfmdr1 gene and in vitro Artemether and lumefantrine sensitivity in Thai isolates of plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lefèvre G, Thomsen MS. Clinical pharmacokinetics of Artemether and lumefantrine (Riamet®). Clin Drug Investig. 1999. 10.2165/00044011-199918060-00006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Djimdé A, Doumbo OK, Steketee RW, Plowe CV. Application of a molecular marker for surveillance of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. Lancet. 2001. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ecker A, Lehane AM, Clain J, Fidock DA. PfCRT and its role in antimalarial drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. 2012. 10.1016/j.pt.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Folarin OA, et al. In vitro amodiaquine resistance and its association with mutations in Pfcrt and pfmdr1 genes of plasmodium falciparum isolates from Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2011. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li XQ, Björkman A, Andersson TB, Ridderström M, Masimirembwa CM. Amodiaquine clearance and its metabolism to N-desethylamodiaquine is mediated by CYP2C8: A new high affinity and turnover enzyme-specific probe substrate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002. 10.1124/jpet.300.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bopp S, et al. Plasmepsin II-III copy number accounts for bimodal Piperaquine resistance among Cambodian plasmodium falciparum. Nat Commun. 2018. 10.1038/s41467-018-04104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witkowski B, et al. A surrogate marker of piperaquine-resistant plasmodium falciparum malaria: a phenotype–genotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JS, et al. Screening of genetic polymorphisms of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genes. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013. 10.4196/kjpp.2013.17.6.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahotorn K, et al. In vitro sensitivity of Pyronaridine in Thai isolates of plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Croft SL, et al. Review of Pyronaridine anti-malarial properties and product characteristics. Malar J. 2012. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Constantino L, Paixão P, Moreira R, Portela MJ, Do Rosario VE, Iley J. Metabolism of primaquine by liver homogenate fractions. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1999. 10.1016/s0940-2993(99)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kerb R, et al. Pharmacogenetics of antimalarial drugs: effect on metabolism and transport. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sokhna CS, Trape JF, Robert V. Gametocytaemia in Senegalese children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria treated with chloroquine, amodiaquine or sulfadoxine + pyrimethamine. Parasite. 2001. 10.1051/parasite/2001083243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ariey F, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505(7481):50–5. 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pillai DR, et al. Artemether resistance in vitro is linked to mutations in PfATP6 that also interact with mutations in PfMDR1 in travellers returning with plasmodium falciparum infections. Malar J. 2012. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svensson USH, Ashton M. Identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the in vitro metabolism of Artemisinin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Motta V, et al. Artesunate and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in a severe plasmodium falciparum malaria case imported from Republic of Côte D’Ivoire. Int J Infect Dis. 2022. 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kwiatkowski DP. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach Us about malaria. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(2):171–92. 10.1086/432519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atkinson A, Garnier S, Afridi S, Fumoux F, Rihet P. Genetic variations in genes involved in Heparan sulphate biosynthesis are associated with plasmodium falciparum parasitaemia: A Familial study in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2012. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chitnis CE, Blackman MJ. Host cell invasion by malaria parasites. Parasitol Today. 2000 Oct;16(10):411–5. 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01756-7. PMID: 11006471. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Gouagna LC, Bancone G, Yao F, Costantini C, Ouedraogo J-B, Modiano D. Impact of protective haemoglobins C and S on P. falciparum malaria transmission in endemic area. Malar. J. 2010;9(S2):2010. 10.1186/1475-2875-9-s2-o17

- 62.Friedman MJ, Roth EF, Nagel RL, Trager W. The role of hemoglobins C, S, and N(Balt) in the Inhibition of malaria parasite development in vitro. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28(5):777–80. 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mangano VD, et al. Novel insights into the protective role of hemoglobin S and C against plasmodium falciparum parasitemia. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(4):626–34. 10.1093/infdis/jiv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cot M, Garcia A. Résistance Constitutionnelle Au paludisme: synthèse des hypothèses physiopathologiques. Bull Mem Soc Anthropol Paris. 1995;7(1):3–19. 10.3406/bmsap.1995.2404. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rowe JA, et al. Blood group O protects against severe plasmodium falciparum malaria through the mechanism of reduced rosetting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007. 10.1073/pnas.0705390104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pathirana SL, et al. ABO-blood-group types and protection against severe, plasmodium falciparum malaria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005. 10.1179/136485905X19946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ouattara AK, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in Burkina Faso: G-6-PD Betica Selma and Santamaria in people with symptomatic malaria in Ouagadougou. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016. 10.4084/mjhid.2016.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ayi K, et al. Pyruvate kinase deficiency and malaria. N Engl J Med. 2008. 10.1056/nejmoa072464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Min-Oo G, Willemetz A, Tam M, Canonne-Hergaux F, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Mapping of Char10, a novel malaria susceptibility locus on mouse chromosome 9. Genes Immun. 2010. 10.1038/gene.2009.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verra F, Mangano VD, Modiano D. Genetics of susceptibility to plasmodium falciparum: from classical malaria resistance genes towards genome-wide association studies. Parasite Immunol. 2009. 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elagib AA, Kider AO, Åkerström B, Elbashir MI. Association of the haptoglobin phenotype (1–1) with falciparum malaria in Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998. 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)91025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quaye IKE, et al. Haptoglobin 1–1 is associated with susceptibility to severe plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000. 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atkinson SH, et al. The haptoglobin 2–2 genotype is associated with a reduced incidence of plasmodium falciparum malaria in children on the Coast of Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 2007. 10.1086/511868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cox SE, et al. Haptoglobin genotype, haemoglobin and malaria in Gambian children. FASEB J. 2007. 10.1096/fasebj.21.6.a1118-d. [Google Scholar]

- 75.De VRR, Mendonça MS, Goncalves, Barral-Netto M. The host genetic diversity in malaria infection. J Trop Med. 2012. 10.1155/2012/940616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Afridi S, Atkinson A, Garnier S, Fumoux F, Rihet P. Malaria resistance genes are associated with the levels of IgG subclasses directed against plasmodium falciparum blood-stage antigens in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2012. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Atkinson A. Contribution à l’identification de facteurs de résistance au paludisme à Plasmodium falciparum chez l’homme: Analyses d’association familiale et d’interaction génétique de l’IL12B, de HS3ST3A1, de HS3ST3B1 et de l’HBB, 2011.

- 78.Brisebarre A, et al. A genome scan for plasmodium falciparum malaria identifies quantitative trait loci on chromosomes 5q31, 6p21.3, 17p12, and 19p13. Malar J. 2014. 10.1186/1475-2875-13-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mehta A, Baltimore D. MicroRNAs as regulatory elements in immune system logic. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016. 10.1038/nri.2016.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Loon W, et al. MiRNA-146a polymorphism was not associated with malaria in Southern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020. 10.4269/AJTMH.19-0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Van Loon W, Gai PP, Hamann L, Bedu-Addo G, Mockenhaupt FP. MiRNA-146a polymorphism increases the odds of malaria in pregnancy. Malar J. 2019. 10.1186/s12936-019-2643-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.White NJ, et al. Hyperparasitaemia and low dosing are an important source of anti-malarial drug resistance. Malar J. 2009. 10.1186/1475-2875-8-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Amaratunga C, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: A multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00487-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Imwong M, Jindakhad T, Kunasol C, Sutawong K, Vejakama P, Dondorp AM. An outbreak of Artemisinin resistant falciparum malaria in Eastern Thailand. Sci Rep. 2015. 10.1038/srep17412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hallett RL, et al. Combination therapy counteracts the enhanced transmission of drug-resistant malaria parasites to mosquitoes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004. 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3940-3943.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ord R, et al. Seasonal carriage of Pfcrt and pfmdr1 alleles in Gambian plasmodium falciparum imply reduced fitness of chloroquine-resistant parasites. J Infect Dis. 2007. 10.1086/522154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Osman ME, Mockenhaupt FP, Bienzle U, Elbashir MI, Giha HA. Field-based evidence for linkage of mutations associated with chloroquine (pfcrt/pfmdr1) and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (pfdhfr/pfdhps) resistance and for the fitness cost of multiple mutations in P. falciparum. Infect Genet Evol. 2007. 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rosenthal PJ. The interplay between drug resistance and fitness in malaria parasites. Mol Microbiol. 2013. 10.1111/mmi.12349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hallett RL, et al. Chloroquine/Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine for Gambian children with malaria: transmission to mosquitoes of Multidrug-Resistant plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006. 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Somé AF, et al. Plasmodium falciparum msp1 and msp2 genetic diversity and allele frequencies in parasites isolated from symptomatic malaria patients in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):1–8. 10.1186/s13071-018-2895-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abamecha A, et al. Genetic diversity and genotype multiplicity of plasmodium falciparum infection in patients with uncomplicated malaria in Chewaka district, Ethiopia. Malar J. 2020. 10.1186/s12936-020-03278-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sondo P, et al. Genetically diverse plasmodium falciparum infections, within-host competition and symptomatic malaria in humans. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–9. 10.1038/s41598-018-36493-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sondo P, et al. Artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine therapies and selection of Pfcrt and PfmdR1 alleles in Nanoro, Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 2016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sondo P, et al. Polymorphisme de plasmodium falciparum et mutations des gènes de résistance Pfcrt et Pfmdr1 Dans La zone de Nanoro, Burkina Faso. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:1–9. 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.118.26959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Amodu OK, et al. Genetic diversity of the msp-1 locus and symptomatic malaria in south-west Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2005. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gueye NSG, et al. Plasmodium falciparum merozoite protein-1 genetic diversity and multiplicity of infection in isolates from Congolese children consulting in a pediatric hospital in Brazzaville. Acta Trop. Jul. 2018;183:78–83. 10.1016/J.ACTATROPICA.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Soulama I, et al. Plasmodium falciparum genotypes diversity in symptomatic malaria of children living in an urban and a rural setting in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2009. 10.1186/1475-2875-8-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vézilier J, Nicot A, Gandon S, Rivero A. Insecticide resistance and malaria transmission: infection rate and oocyst burden in Culex pipiens mosquitoes infected with plasmodium relictum. Malar J. 2010. 10.1186/1475-2875-9-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hemingway J, et al. Averting a malaria disaster: will insecticide resistance derail malaria control? Lancet. 2016. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00417-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kelly-Hope L, Ranson H, Hemingway J. Lessons from the past: managing insecticide resistance in malaria control and eradication programmes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008. 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ranson H, et al. Molecular analysis of multiple cytochrome P450 genes from the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2002. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ranson H, Jensen B, Wang X, Prapanthadara L, Hemingway J, Collins FH. Genetic mapping of two loci affecting DDT resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2000. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sombié A, et al. Association of 410L, 1016I and 1534 C Kdr mutations with pyrethroid resistance in Aedes aegypti from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, and development of a one-step multiplex PCR method for the simultaneous detection of 1534 C and 1016I Kdr mutations. Parasites Vectors. 2023. 10.1186/s13071-023-05743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Toé HK, et al. Multiple insecticide resistance and first evidence of V410L Kdr mutation in Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (Linnaeus) from Burkina Faso. Med Vet Entomol. 2022. 10.1111/mve.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Riveron JM, et al. Escalation of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus induces a loss of efficacy of piperonyl Butoxide-Based Insecticide-Treated Nets in Mozambique. J Infect Dis. 2019. 10.1093/infdis/jiz139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Protopopoff N, et al. High level of resistance in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae to pyrethroid insecticides and reduced susceptibility to Bendiocarb in north-western Tanzania. Malar J. 2013. 10.1186/1475-2875-12-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yadouleton A, et al. Detection of multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms in Anopheles gambiae sl populations from the vegetable farming area of Houeyiho, southern Benin, West Africa; 2018. p. 21–7.

- 108.Oumbouke WA, et al. Exploring alternative insecticide delivery options in a ‘lethal house lure’ for malaria vector control. Sci Rep. 2023. 10.1038/s41598-023-31116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oumbouke WA, Rowland M, Koffi AA, Alou LPA, Camara S, N’guessan R. Evaluation of an alpha-cypermethrin + PBO mixture long-lasting insecticidal net VEERALIN® LN against pyrethroid resistant Anopheles gambiae S.s.: an experimental hut trial in M’bé, central Côte D’Ivoire. Parasites Vectors. 2019. 10.1186/s13071-019-3796-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dabiré RK, et al. Distribution and frequency of Kdr mutations within Anopheles gambiae S.l. Populations and first report of the Ace.1G119S mutation in Anopheles arabiensis from Burkina Faso (West Africa). PLoS ONE. 2014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chouaïbou M, et al. Dynamics of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae S.l. From an area of extensive cotton cultivation in Northern Cameroon. Trop Med Int Heal. 2008. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Santolamazza F, Mancini E, Simard F, Qi Y, Tu Z, Della Torre A. Insertion polymorphisms of SINE200 retrotransposons within speciation Islands of Anopheles gambiae molecular forms. Malar J. 2008. 10.1186/1475-2875-7-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Verhaeghen K, Van Bortel W, Roelants P, Backeljau T, Coosemans M. Detection of the East and West African Kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis from Uganda using a new assay based on fret/melt curve analysis. Malar J. 2006. 10.1186/1475-2875-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kabula B, et al. Co-occurrence and distribution of East (L1014S) and West (L1014F) African knock-down resistance in Anopheles gambiae sensu Lato population of Tanzania. Trop Med Int Heal. 2014. 10.1111/tmi.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tmimi FZ, Faraj C, Bkhache M, Mounaji K, Failloux AB, Sarih M. Insecticide resistance and target site mutations (G119S ace-1 and L1014F kdr) of Culex pipiens in Morocco. Parasites Vectors. 2018. 10.1186/s13071-018-2625-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Samake JN, et al. Detection and population genetic analysis of Kdr L1014F variant in Eastern Ethiopian Anopheles stephensi. Infect Genet Evol. 2022. 10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Medjigbodo AA, et al. Interplay between Oxytetracycline and the homozygote Kdr (L1014F) resistance genotype on fecundity in Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes. J Insect Sci. 2021. 10.1093/jisesa/ieab056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rai P, Saha D. Occurrence of L1014F and L1014S mutations in insecticide resistant Culex quinquefasciatus from filariasis endemic districts of West Bengal, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 119.Osoro JK, et al. Insecticide resistant Anopheles gambiae have enhanced longevity but reduced reproductive fitness and a longer first gonotrophic cycle. Sci Rep. 2022. 10.1038/s41598-022-12753-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Toé KH, Jones CM, N’fale S, Ismai HM, Dabiré RK, Ranson H. Increased pyrethroid resistance in malaria vectors and decreased bed net effectiveness Burkina Faso. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014. 10.3201/eid2010.140619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kamande DS, Odufuwa OG, Mbuba E, Hofer L, Moore SJ. Modified world health organization (WHO) tunnel test for higher throughput evaluation of Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) considering the effect of alternative hosts, exposure time, and mosquito density. Insects. 2022. 10.3390/insects13070562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Corbel V, et al. A new WHO bottle bioassay method to assess the susceptibility of mosquito vectors to public health insecticides: results from a WHO-coordinated multi-centre study. Parasites Vectors. 2023. 10.1186/s13071-022-05554-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Verdrager J. Epidemiology of emergence and spread of drug-resistant falciparum malaria in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1986 Mar;17(1):111–8. PMID: 3526576. [PubMed]

- 124.Wernsdorfer WH. Epidemiology of drug resistance in malaria. Acta Trop. 1994. 10.1016/0001-706X(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fan Y, O’grady P, Yoshimizu M, Ponlawat A, Kaufmanid PE, Scott JG. Evidence for both sequential mutations and recombination in the evolution of Kdr alleles in aedes Aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang S, Ghosh AK, Bongio N, Stebbings KA, Lampe DJ, Jacobs-Lorena M. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012. 10.1073/pnas.1204158109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Crampton JM, Stowell SL, Karras M, Sinden RE. Model systems to evaluate the use of transgenic haematophagous insects to deliver protective vaccines. Parassitologia. 1999 Sep;41(1–3):473–7. PMID: 10697904. [PubMed]

- 128.Dong Y, Taylor HE, Dimopoulos G. AgDscam, a hypervariable Immunoglobulin domain-containing receptor of the Anopheles gambiae innate immune system. PLoS Biol. 2006. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dimopoulos G, Kafatos FC, Waters AP, Sinden RE. Malaria parasites and the anopheles mosquito. Chem Immunol. 2002. 10.1159/000058838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Dimopoulos G., et al. Genome expression analysis of Anopheles Gambiae: responses to injury, bacterial challenge, and malaria infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002. 10.1073/pnas.092274999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 131.Christophides GK. Transgenic mosquitoes and malaria transmission. Cell Microbiol. 2005. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Guissou C, Quinlan MM, Sanou R, Ouédraogo RK, Namountougou M, Diabaté A. Preparing an insectary in Burkina Faso to support research in genetic technologies for malaria control. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2022. 10.1089/vbz.2021.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shaw WR, et al. Wolbachia infections in natural Anopheles populations affect egg laying and negatively correlate with plasmodium development. Nat Commun. 2016. 10.1038/ncomms11772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gantz VM, Bier E. The dawn of active genetics. BioEssays. 2016. 10.1002/bies.201500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hammond A, et al. A CRISPR-Cas9 gene drive system targeting female reproduction in the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae. Nat Biotechnol. 2016. 10.1038/nbt.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hammond A, et al. Gene-drive suppression of mosquito populations in large cages as a Bridge between lab and field. Nat Commun. 2021. 10.1038/s41467-021-24790-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hammond AM, Galizi R. Gene drives to fight malaria: current state and future directions. Pathogens Global Health. 2017. 10.1080/20477724.2018.1438880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Burt A, Coulibaly M, Crisanti A, Diabate A, Kayondo JK. Gene drive to reduce malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. J Responsible Innov. 2018. 10.1080/23299460.2017.1419410. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Eissenberg JC. In our image: the ethics of CRISPR genome editing. Biomol Concepts. 2021. 10.1515/bmc-2021-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Smidler AL, et al. A confinable female-lethal population suppression system in the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. Sci Adv. 2023. 10.1126/sciadv.ade8903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Boëte C, Burza S, Lasry E, Moriana S, Robertson W. Malaria vector control tools in emergency settings: what do experts think? Results from a DELPHI survey. Confl Health. 2021. 10.1186/s13031-021-00424-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yao FA, et al. Mark-release-recapture experiment in Burkina Faso demonstrates reduced fitness and dispersal of genetically-modified sterile malaria mosquitoes. Nat Commun. 2022. 10.1038/s41467-022-28419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bier E. Gene drives gaining speed. Nat Rev Genet. 2022. 10.1038/s41576-021-00386-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kyrou K, et al. A CRISPR–Cas9 gene drive targeting doublesex causes complete population suppression in caged Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Nat Biotechnol. 2018. 10.1038/nbt.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sinka ME, et al. The dominant anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Asia-Pacific region: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasites Vectors. 2011. 10.1186/1756-3305-4-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Matsuoka H, Ikezawa T, Hirai M. Production of a transgenic mosquito expressing circumsporozoite protein, a malarial protein, in the salivary gland of Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae). Acta Med Okayama. 2010 Aug;64(4):233–41. 10.18926/AMO/40131. PMID: 20802540. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 147.Nardella F, et al. DNA methylation bisubstrate inhibitors are Fast-Acting drugs active against Artemisinin-Resistant plasmodium falciparum parasites. ACS Cent Sci. 2020. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ponts N, et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNA methylation in the human malaria parasite plasmodium falciparum. Cell Host Microbe. 2013. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Hammam E, et al. Malaria parasite stress tolerance is regulated by DNMT2- mediated tRNA cytosine methylation. MBio. 2021. 10.1128/mBio.02558-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hammam E, et al. Discovery of a new predominant cytosine DNA modification that is linked to gene expression in malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020. 10.1093/nar/gkz1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.WHO. Strategy to respond to antimalarial drug resistance in Africa, vol. 1. 2022.

- 152.WHO. Artemisinin and artemisinin-based combination therapy resistance, WHO/HTM/GMP/2016.5, 2017.

- 153.World Health Organization. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.