Abstract

Objective

To systematically and statistically evaluate evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the efficacy and safety of somatic stem cells in achieving glycemic control in type 1 and 2 diabetic patients.

Methods

Bibliographic databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched from the time of their establishment till January 2024. Obtained records were meticulously screened by title, abstract, and full text to include only RCTs seeking mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) treatment for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Included studies underwent quality assessment using the Cochrane risk of bias 2 tool (ROB2).

Results

Thirteen studies were deemed eligible for meta-analysis, encompassing 507 patients (T1DM = 199, T2DM = 308). To measure treatment efficacy, the present meta-analysis was conducted on outcomes reported after 12 months following treatment. MSCs therapy group was associated with a significantly reduced glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) compared to the control group, MD = -0.72; 95% CI: [-1.11 to -0.33], P = 0.0003, I2 = 56%. Daily insulin requirement was lower in the MSCs group versus placebo, MD = -14.50; 95% CI: [-19.45 to -9.55], P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%. Pooled fasting C-peptide levels were significantly higher in the MSCs group compared to placebo, MD = 0.24; 95% CI: [0.05 to 0.43], P = 0.01, I2 = 93%. Postprandial blood glucose (PPBG) was observed to be significantly lower in the MSCs arm in contrast to placebo, MD = -11.32; 95% CI: [-16.46 to -6.17], P < 0.0001, I2 = 17%. However, pooled analysis of fasting blood glucose (FBG) was not significantly different between both groups, MD = -6.22; 95% CI: [-24.23 to 11.79], P = 0.50, I2 = 81% at the end of the 12-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived therapy is an efficacious glycemia-lowering modality agent compared to conventional therapy in T1DM and T2DM patients. Albeit more sizeable and longer RCTs are warranted to further support and standardize their clinical use.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-025-01619-6.

Keywords: Stem cells, Diabetes mellitus, Type 1 diabetes mellitus, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Glycated hemoglobin, Glycemic control, Hematopoietic stem cells, Mesenchymal stem cells, Umbilical cord stem cells

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an evolving epidemic and is the eighth-leading cause of mortality worldwide [1]. It imposes a significant healthcare burden globally, with over half a billion adults affected and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) predicting a 46% increase in the next two decades [2].

DM, particularly type 1 and 2 (T1DM and T2DM), is hallmarked by pancreatic beta cells impairment and hyperglycemia, leading to multi-systemic damage [3, 4]. Uncontrolled chronic hyperglycemia increases morbidity and reduces life quality and expectancy [5, 6]. It causes macrovascular and microvascular complications including atherosclerosis, hypertension, nephropathy, polyneuropathy, and retinopathy [6]. Therefore, strict glycemic control is an essential goal of treatment to prevent these complications.

DM research has led to advancements in screening, diagnosis, and treatment [7–11]. Current therapies for T2DM include biguanides (metformin), GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors [12–15]. T1DM patients use exogenous insulin, as do type 2 patients who have exhausted endogenous insulin reserves [16].

These therapies reduce morbidity and mortality but do not stop the destruction of pancreatic islets. They carry side effects like gastrointestinal upset, hypoglycemia, acidosis, and increased risk of infections [17, 18]. Exogenous insulin can cause systemic hypersensitivity or localized reactions [18].

Researchers are exploring definitive treatments like whole pancreas transplantation, pancreatic islets transplantation, and stem cell-based therapies [19, 20]. These have shown remission results, especially whole organ transplants, but carry surgery risks and require immunosuppression [21, 22]. They have risks related to immunosuppression, infections, and malignancy; and require appropriate donor availability and access to specialized facilities [23].

Stem cells have gained attention for their ability to proliferate and differentiate into other cell types. They offer potential for replacing abnormal, injured, or absent cells in various diseases. Currently, stem-cell derived therapy trials are evaluating over 20 diseases [24, 25]. including Parkinson’s, motor neuron disease, retinal and corneal pathologies, inflammatory bowel disease, and heart disease [26–29]. The immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, regenerative, and paracrine effects of stem cells are disease-modifying properties and could have endless clinical implications.

Thus, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) offer potential for addressing diabetes by promoting pancreatic beta-cell regeneration, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and modulating immune responses [30] Preclinical trials show promising results for MSCs as islet cell replacement therapy [31–33]. However, clinical trials have contesting conclusions on their effectiveness for different diabetes types. Prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses have provided valuable insights, with Hamad et al. and El-Badawy et al. reporting that stem cell therapy is a safe and effective treatment for T1DM but not T2DM [34, 35]. However, He et al. have revealed that MSCs significantly reduced glycosylated hemoglobin in both diabetic subpopulations [36]. Due to the advent of clinical research in stem cell therapy for DM a comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis of available evidence is required [36].

This systematic review evaluates the safety and efficacy of MSC-based interventions in T1DM and T2DM patients. By analyzing data from RCTs, we aim to understand the impact of MSC therapy on glycemic control, insulin requirements, and beta-cell function, as well as its safety profile in terms of adverse effects. This data may inform management guidelines, clinical decisions, and future research directions.

Methods

The authors adopted the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA-2020) checklist for drafting and writing this manuscript [37]. The methods and analyses were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review and Meta-analysis and the Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews [38]. Moreover, the study is registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO); registration number CRD42023459529.

Sources of literature and search strategy

The following electronic medical literature search engines were meticulously reviewed: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science core collection, and Cochrane Library, in search of studies aimed at investigating MSCs use for T1DM and T2DM. Studies published from inception through January 2024 were retrieved. Pertinent terms and keywords were incorporated into the search strategies such as “mesenchymal stem cell”, “stem cell transplantation”, “diabetes mellitus”, “insulin dependent”, and “insulin resistance”. Supplementary Table 1 encompasses the exhaustive search strategy according to literature databases. Additionally, potentially eligible studies were retrieved through a manual we manually searched for further relevant records. Thus forth, eligible studies were collectively imported to the Rayyan software for screening based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria [39].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Fitness of each study was based on the predefined PICOS model of participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design [40]. Studies were deemed fit for inclusion if they met each of the criteria listed:

Participants were patients with T1DM or T2DM, regardless of age, sex, gender, or race.

Intervention was MSCs, regardless of source (umbilical cord, Wharton’s jelly, bone marrow, feta liver, etc.)

Comparator was standard care, sham procedure, or any comparator identified as placebo (normal saline infusion, human albumin, etc.).

-

Outcomes, if any of the following were reported:

- Change in Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) (%).

- Change in fasting blood glucose (PBG) (mg/dL).

- Change in postprandial blood glucose (PPBG) (mg/dL).

- Change in daily insulin requirement (U/day).

- Change in fasting serum c-peptide (ng/mL).

- Change in stimulated serum c-peptide (ng/mL).

- Change in homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistant (HOMA-IR) (%).

- Change in homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-β) (%).

- Adverse events (AEs).

Study design referred to as RCT.

On the other hand, records disqualified were those: published in a non-English language, studies presenting non-clinical data including preclinical and basic science, and study designs were not RCT (conference proceedings, abstracts, editorials, literature or commentary reviews, observational studies, and animal studies).

Literature screening and data extraction

Compiled records from all searched databases were scrutinized by four authors independently in a dual phase process. Phase one entailed title and abstract screening based on the eligibility criteria. In phase two, abstract-eligible records underwent a full manuscript sweep. At each step, a third independent author reviewed conflicting records and duplicates.

Thereafter, data extraction from the included studies was pursued by four independent authors and entered into an online Google Sheets [41]. Information describing the characteristics of each study included: study ID, study location, study design, DM type, stem cell type, duration of DM, participant size in the intervention and control arms, quantity of stem cell used, type of control used, duration of the study/follow-up period, and outcomes of interest. Moreover, standard study cohort information was registered serving as the baseline data. Outcomes from each study were recorded according to each follow-up period, at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Outcomes of interest are those listed in the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If the outcome data sets were a continuous variable, they are extracted as means and standard deviations (SDs). While variables of a dichotomous entity were extracted as a frequency and a percentage (%). For outcomes represented with a graph, data points were determined via the software plot digitizer versions 2.6.8 [42].

Risk of bias assessment

To assess the quality of the included studies, two independent authors utilized the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (ROB2) tool [43]. The authors investigated potential biases in the following aspects: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, inadequate outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and others. A third author assisted in reviewing discording biases between the two main reviewers.

Measures of treatment efficacy and statistical analysis

The effectiveness of stem cell therapy in diabetic patients was interpreted by examining the magnitude of change from baseline in the following main outcomes of interest: glycosylated hemoglobin (%), fasting blood glucose (mg/dL), postprandial blood glucose (mg/dL), fasting C-peptide (ng/mL), and insulin requirement (U/day). Secondary measures included change from baseline in the following outcomes, stimulated C-peptide (ng/mL), HOMA-B (%), and HOMA-IR (%). These changes were pooled as mean difference (MD) in a meta-analysis model. Adverse events were pooled as odds ratio between both groups with a 95% CI using the Mantel -Haenszel method. Statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager version 5.4.1 for the Windows operating system [44].

Heterogeneity was assessed through the I² statistic, with significance determined by the corresponding p-value in the Cochrane Q test. An I² value of 0% signifies no observed heterogeneity, while values of 25%, 50–75%, and > 75% indicate low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively [38]. If significant heterogeneity is observed, a sensitivity analysis is conducted to address the heterogeneity.

Dealing with missing data

Continuous outcomes reported using medians along with interquartile ranges or ranges were converted into means and SDs using specific estimate measures. The analytical tool used for this specific conversion is adopted from Wan et al., where a normal distribution is assumed [45]. In addition, the mean difference was calculated by subtracting the mean of baseline data from the mean of outcome data. The standard deviation of change was extrapolated using the baseline and final SD with the employment of a correlation coefficient (r) in concordance with the Cochrane Handbook meta-analysis of continuous outcomes [46].

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were performed according to:

Type of DM: T1DM and T2DM.

Duration of the follow-up: 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months.

Assessment of publication bias

Funnel plots generated from the meta-analysis models were examined in search of a publication bias in any outcome including 10 studies or more. An asymmetrical distribution of study outcomes around the measure of effect would be indicative of a publication bias.

Results

Search results

In total, 8991 studies were collected from PubMed (3347), Scopus (3390), Web of Science (2075), and Cochrane Library (179). Figure 1 outlines the search and screening process of the available literature. Once the records were compiled together, with the assistance of Endnote reference manager software, 3560 duplicated studies were eliminated. Following title & abstract screening, 121 studies underwent full text screening, rendering 13 studies eligible for final inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart diagram of the literature screening & inclusion process

Summary of included studies

In the present review, 13 RCTs encompassing 507 participants were reviewed and analyzed [47–59]. Five studies were conducted in China, three in India, two in Iran, two in Sweden, and one in the United States. In terms of study design, three were pilot trials, three were phase I/II, and seven were phase II and/or III; the majority were double-blinded studies while three were single-blinded and three were open-label. Table 1 summarizes key descriptions and identifiers for all the studies included.

Table 1.

Summary of included randomized controlled trials

| Study ID | Study design | Country | DM Type | SCT type | Sample size (N) | Dose of intervention | Control | Follow-up period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCT | Placebo | Total | ||||||||

| Bhansali 2014 [53] | Single-blinded RCT | India | T2DM | ABMSCs | 11 | 10 | 21 | 10 µg/kg/day | Sham procedure + 10 ml normal saline | 12 months |

| Bhansali 2016 [54] | Single-blinded RCT | India | T2DM | ABMSCs | 10 | 10 | 20 | 1 × 10^6/kg | Sham procedure + 10 ml of diluted vit B complex | 12 months |

| Cai 2016 [47] | Pilot Open-Label RCT | China | T1DM | UCMSCs and ABMMNCs | 21 | 21 | 42 | 1.1 × 10^6/kg UC-MSC + 106.8 × 10^6-MNC | Standard care | 12 months |

| Carlsson 2023 [52] | Double-blind RCT | Sweden | T1DM | UCMSCs (WJ-MSCs, ProTrans) | 10 | 5 | 15 | ProTrans (200 million cells) | 5% wt./vol. human serum albumin + 10% vol./vol. DMSO | 12 months |

| Carlsson 2015 [51] | Open pilot RCT | Sweden | T1DM | BMMSC | 10 | 10 | 20 | 2.75 × 10^6 cells/kg | Stander care | 12 months |

| Ghodsi 2012 [59] | Double-blind RCT | Iran | T1DM T2DM | Fetal liver-derived HSCs | 28 | 28 | 56 | 35–55 × 10^6 cells in 5 ml of normal saline IV | 5 ml of normal saline | 12 months |

| Hu 2013 [48] | RCT | China | T1DM | UCMSCs (WJ-MSCs) | 15 | 14 | 29 | 2.6 × 10^7/kg x2 | Santander care + 50 mL of normal saline. | 24 months |

| Hu 2016 [47] | Double-blind RCT | China | T2DM | UCMSCs (WJ-MSCs) | 31 | 30 | 61 | 1 × 10^6/kg | Standard care + 100 ml normal saline | 36 months |

| Izadi 2022 [50] | RCT | Iran | T1DM | BMMSCs | 11 | 10 | 21 | 1 × 10 ^6/kg x2 | 100 ml of normal saline | 12 months |

| Skyler 2015 [58] | Single-blind RCT | USA | T2DM | BMMSCs rexlemestrocel-L | 45 | 16 | 61 |

G1 = 0.3 × 10^6/kg G2 = 1.0 × 10^6/kg G3 = 2.0 × 10^6/kg |

100 ml of normal saline | 24 months |

| Sood 2016 [57] | RCT | India | T2DM | ABMSCs | 21 | 7 | 28 |

G1 = 4.9 × 10^8 G2 = 12.04 × 10^8 G3 = 6.88 × 10^8 |

Sham procedure | 6 months |

| Wu 2022 [49] | Pilot Open-Label RCT | China | T1DM | UCMSCs and ABMMSCs | 21 | 21 | 42 | 1.10 × 10^6 MSCs/kg + 0.61 × 10^10 BM-MNCs | Standard care | 8 years |

| Zang 2022 [56] | Double-blinded RCT | China | T2DM | UCMSCs | 45 | 46 | 91 | 1 × 10^6/kg | 100 ml of normal saline | 6 months |

ABMSCs: Autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs, UCMSCs umbilical cord MSCs, ABMMNCs: autologous marrow-derived MSCs, HSCs: hematopoietic stem cell, WJ-MSCs: Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs

The participants allocated to the interventional arm tallied to 279, while control participants were at total of 228. In terms of patients’ disease, six RCTs evaluated patients with T1DM (n = 169), and another six evaluated only T2DM patients (n = 282), while a single study included both types of diabetic patients (n T1DM = 30, n T2DM = 26). All studies used somatic/adult stem cells however, they varied in the source. Seven sourced bone marrow stem cells, five of them used autologous mesenchymal stromal cells (ABM-MSCs), one used allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells (BM-MPCs) and another one used autologous mononuclear cells (ABM-MNCs) [50, 51, 53, 54, 57, 58]. Four experimented with allogeneic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (UC-MSCs) and two studies combined UC-MSCs with ABM-MNCs [47–49, 52, 55, 56]. Finally, Ghodsi et al. used fetal liver-derived hematopoietic cells (HSCs) when investigating T1DM and T2DM patients [59].

Participants enrolled in the studies were observed to have differing baseline characteristics. In T2DM studies, patients were mainly middle-aged adults with the age mean ranging from 42.8 to 58.7 years, while in T1DM studies the mean age range was wider with 10.27 to 36 years. Duration of diabetes was more than 4 years in all studies except for Carlsson et al. trial which only included those with a recent T1DM diagnosis (< 2 years) [52]. Less than half of the studies had patients with a controlled disease state at baseline, HbA1C < 7%, specifically Carlsson et al. in their 2023 trial had the lowest mean HbA1c of 6.5% [48, 51–54, 57]. On the other hand, Ghodsi et al. had the highest HbA1C mean among their participants, 9.9% [59]. Further baseline figures are identified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Study Arms | Age | Sex (no. of females) % | Weight (kg), | BMI (kg/m2) | Duration (years) | Insulin requirement U/day | HbA1c (%), | Fasting plasma glucose | Fasting C-peptide ng/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhansali 2014 [53] | Intervention | 51.0(46.5–56.0)* | 2(18%) | 81.6(73.6–89.9)* | 28.5(26.3–30.3)* | 12.0(10.0–15.5)* | 42.0(31.0–64.0)* | 6.9(6.4–7.1)* | 94.5(87.7–103.4)* | 0.7(0.3–1.2)* |

| Control | 54.0 (52.5–55.8)* | 3(30%) | 74.1(71.5–76.6)* | 28.9(26.3–30.3)* | 20.0(16.3–20.8)* | 40.5(31.8–44.3)* | 6.9(6.2–7.0)* | 103.0(95.0–112.3)* | 1.2(0.7–1.6)* | |

| Bhansali 2014 [53] | Intervention | 50.5(36.0–58.0)* | 2(20%) | 81.5(70.2–91.3)* | 28.1(26.5–31.6)* | 15.0(8.0–22.8)* | 47.5(34.0–52.3)* | 6.9(6.6–7.0)* | 5.8(5.3–6.2)* | 0.4(0.3–0.4)*§ |

| Control | 53.5(43.3–58.8)* | 4(40%) | 69.3(64.9–72.9)* | 25.7(24.5–28.9)* | 14.0(9.0–15.0)* | 48.5(29.5–76.0)* | 6.5(6.2–6.8)* | 6.0(5.5–6.7)* | 0.5(0.4–0.7)*§ | |

| Cai 2016 [47] | Intervention | 18.29 | 12(57%) | 59.50(8.42) | 21.99(1.78) | 9.24(2–16)* | 0.91(0.23)∥ | 8.56(0.81) | 200.06(51.09) | |

| Control | 20.38 | 10(74%) | 60.33(10.76) | 22.06(2.46) | 7(2–13)* | 0.90(0.20)∥ | 8.68(0.87) | 192.43(35.318) | ||

| Carlsson 2023 [52] | Intervention | 24(2) | 1(11%) | 78(3) | 23.3(1.1) | 0.43(0.05)∥ | 6.5(0.4) | 0.29(0.05)§ | ||

| Control | 27(2) | 4(44%) | 68(4) | 22.5(0.9) | 0.39(0.13)∥ | 6.9(0.4) | 0.28(0.02)§ | |||

| Carlsson 2023 [52] | Intervention | 31(4) | 4(40%) | 73.9(9.3) | 24.2(2.9) | 1.0(0.7) | 17(7) | 6.5(1.4) | 0.32(0.19)§ | |

| Control | 31(9) | 3(60%) | 67.5(12.6) | 23.5(2.2) | 1.0(0.3) | 30(10) | 6.6(0.7) | 0.16(0.05)§ | ||

| Ghodsi 2012 [59] | Intervention Type 1 | 21.61(10.53) | 6(46.2%) | 4.23(2.21) | 10.8(2.0) | 219.0(126.4) | 0.28(0.60) | |||

| Control 1 | 21.35(9.80) | 9(52.9%) | 4.11(2.86) | 10.1(1.4) | 223.2(125.1) | 0.27(0.49) | ||||

| Intervention Type 2 | 48.33(9.75) | 12(80.0%) | 6.03(2.55) | 9.4(1.6) | 166.0(56.6) | 2.2(0.9) | ||||

| Control 2 | 42.81(13.63) | 7(63.6%) | 6.04(3.27) | 9.2(1.2) | 151.8(69.6) | 2.2(0.9) | ||||

| Hu 2016 [47] | Intervention | 17.6(8.7) | 6(40%) | 20.9(3.7) | 6.85(0.74) | 102.6(30.8) | 0.85(0.47) | |||

| Controls | 18.2(7.9) | 6(43%) | 21.3(4.2) | 6.79(0.81) | 97.2(29.6) | 0.89(0.39) | ||||

| Hu 2016 [47] | Intervention | 52.43(4.88) | 14(45.16%) | 26.74(5.41) | 8.93(5.67) | 45.92(8.87) | 7.67(1.23) | 148.27(27.81) | 1.75(0.64) | |

| Control | 53.21(8.22) | 14(46.667%) | 27.03(6.68) | 8.3(6.07) | 43.09(10.3) | 7.54(1.31) | 142.31(25.88) | 1.83(0.59) | ||

| Izadi 2022 [50] | Intervention | 10.27(1.67) | 5(45%) | 16.57(2.57) | 0.78(0.44)∥ | 8.63(2.19) | 165.27(7.49) | 0.72(0.38) | ||

| Placebo | 11.50(2.63) | 5(50%) | 18.91(3.41) | 0.71(0.30)∥ | 7.85(1.45) | 149.9(51.97) | 0.92(0.57) | |||

| Izadi 2022 [50] | Dose 1(0.3) | 57.7(8.2) | 5(33.3%) | 98.6(21.3) | 34.8(6.5) | 10.8(7.3) | 8.3(0.8) | 194.6(67.4) | ||

| Dose 2(1.0) | 55.3(11.4) | 6(40%) | 101.7(21.4) | 34.4(4.7) | 10.2(5.7) | 8.6(1.1) | 197.5(30.5) | |||

| Dose 3(2.0) | 57.2(6.6) | 6(40%) | 92.6(16.9) | 32.4(4.5) | 9.6(4.5) | 7.9(1.1) | 166.1(38.8) | |||

| Controls | 58.7(7.3) | 4(25%) | 95.9(20.2) | 32.6(6.2) | 9.8b(6.7) | 8.2(0.8) | 183(55) | |||

| Sood 2016 [57] | Group 1 | 57.83(5.84) | 3(42.8%) | 79(18.89) | 28.83(4.26) | 19.5(5.54) | 43.66(5.35) | 6.8(0.18) | 106.66(14.36) | 2.97(1.51) |

| Group 2 | 49.85(9.63) | 1 14.3%) | 72.14(8.41) | 26.57(2.63) | 14.28(6.77) | 39.71(3.8) | 6.4(0.16) | 103.42(16.89) | 1.28(0.14) | |

| Group 3 | 53.28(7.29) | 1(14.3%) | 75.78(9.95) | 26.85(3.97) | 14.28(5.64) | 45(6.57) | 6.7(0.15) | 89.71(9.21) | 1.41(0.25) | |

| Control | 55.7(7.7) | 2 (28.6%) | 77.7(13) | 29.6(1.9) | 19.6(6.4) | 43.86(4.50) | 6.6(0.24) | 103.5(6.0) | 1.1(0.2) | |

| Wu 2022 [60] | Intervention | 33.5(27–47)† | (8) 57% | 57(44–80)† | 21.9(19.4–24.8)† | 16(10–24)† | 0.90(0.24)∥ | 8.57(0.97) | 200.06(59.26) | 0.028(0.022)€ |

| Control | 36(26–45)† | (6) 40% | 63(47–79)† | 22.3(19.6–26.7)† | 15(10–21)† | 0.87(0.23)∥ | 8.65(0.87) | 197.45(36.75) | 0.026(0.024)€ | |

| Zang 2022 [56] | Intervention | 50.00(9.38) | 17(38%) | 28.69(3.35) | 11.44(4.78) | 57.36 + 18.90) | 9.02(1.27) | 8.71(2.16)‡ | 2.01(0.70) | |

| Control | 50.45(8.03) | 16(34%) | 28.13(3.04) | 11.70(3.96) | 56.41 + 12.54) | 8.89(1.11) | 8.58(1.93)‡ | 1.93(0.65) |

All date represented as mean and SD, * Data presented as median and interquartile range, † Data presented as median and range,∥ The unit is IU/d/kg, ‡ The unit is mmol/L, § The unit is nmol/L, € The unit is pmol/mL

Risk of bias

Assessment of studies’ quality based on the ROB2 tool has shown an inconsistent overall quality among the studies. Four of the included studies had a low risk of bias; five studies posed some concerns, and four had high risks. For those with a high risk, the randomization process seemed to be the only issue [47, 49, 51]. While those with some concerns mainly arose from both the randomization process and deviations from the intended intervention [53, 54, 57, 58]. Figure 2 details quality assessment according to each ROB2 tool domain respectively for each of the included studies (Fig. 2a) and the studies aggregate risk of bias based on domains (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Quality assessment of included literature. (a) Traffic light map of included studies risk of bias according to each bias domain. (b) Combined quality of assessment of included studies for reach bias domain

Measures of treatment efficacy

Outcomes at 3-month follow up

HbA1c

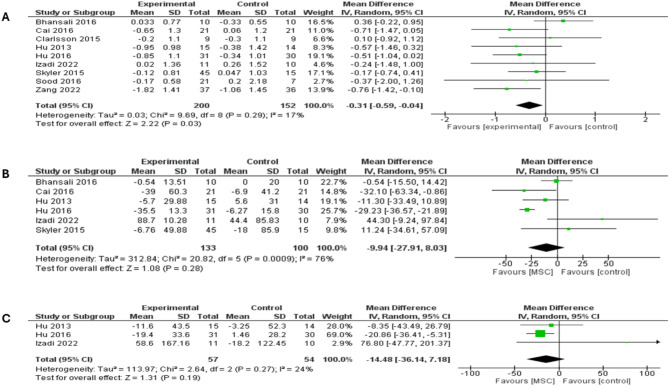

Pooled analysis of nine studies that have reported HbA1c showed significantly reduced HbA1c levels in the stem cell groups versus placebo (MD = -0.31; 95% CI: [-0.59 to -0.04], P = 0.03). Non-significant heterogeneity among study was observed (I2 = 17%; P = 0.29), (Fig. 3a). Comparing T1DM and T2DM in a subgroup analysis showed similar levels of HbA1c between both arms (MD = -0.44; 95% CI: [-0.90 to 0.03], P = 0.07) and (MD = -0.27; 95% CI: [-0.68 to 0.15], P = 0.21), respectively (supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the results at 3-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the HbA1c, (B) Comparison of the FBG, (C) Comparison of the PPBG

FBG

FBG was reported in six studies, which showed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -9.94; 95% CI: [-27.91 to 8.03], P = 0.28), shown in (Fig. 3b). The analysis demonstrated significant heterogeneity (I2 = 76%; P = 0.0009), which was best resolved by excluding Hu et al. study (I2 = 45%; P = 0.12) [55]. However, statistical significance remained unchanged (MD = -4.19; 95% CI: [-21.41 to 13.04], P = 0.63) (supplementary Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences in levels of FBG between MSC therapy and placebo in both subgroups of T1DM and T2DM (MD = -6.48; 95% CI: [-39.47 to 26.51], P = 0.70) and (MD = -10.75; 95% CI: [-36.19 to 14.68], P = 0.41), respectively (supplementary Fig. 2b).

PPBG

The analysis of PPBG at a follow-up period of 3 months included three studies and showed a comparable level of PBG between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -14.48; 95% CI: [-36.14 to 7.18], P = 0.19) (Fig. 3c). The pooled studies demonstrated non-significant heterogeneity (I2 = 24%; P = 0.27). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM showed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo in both subgroups (MD = 12.39; 95% CI: [-59.25 to 84.03], P = 0.73), while T2DM subgroup analysis included a single study and yielded a significant difference favoring MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -20.86; 95% CI: [-36.41 to -5.31], P = 0.009), (see supplementary Fig. 3).

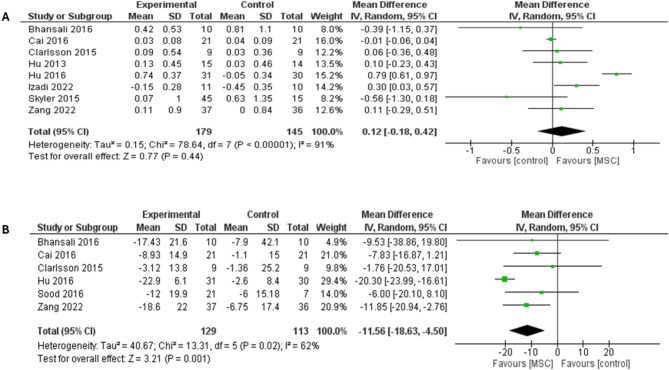

Fasting C-peptide

Fasting C-peptide pooled analysis from eight studies had no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = 0.12; 95% CI: [-0.18 to 0.42], P = 0.44) (Fig. 4a). Significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 91%; P < 0.00001), which was resolved by removing Hu et al. trial, I2 = 31%; P = 0.19 [55] and statistical significance did not favor either arm (MD = 0.04; 95% CI: [-0.09 to 0.18], P = 0.53), (supplementary Fig. 4a). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM and T2DM showed comparable levels of fasting C-peptide between MSC therapy and placebo in both subgroups (MD = 0.08; 95% CI: [-0.08 to 0.23], P = 0.32) (I2 = 42%; P = 0.16) and (MD = 0.06; 95% CI: [-0.06 to 0.71], P = 0.86) (I2 = 88%; P < 0.00001), respectively (supplementary Fig. 4b). Moreover, Hu et al. was excluded from the subgroup analysis to address heterogeneity in the T2DM subgroup (I2 = 35%; P = 0.21). Removing the study of Hu et al. 2016, however, did not significantly affect fasting C-peptide outcome in the T2DM subgroup (MD = -0.18; 95% CI: [-0.61 to 0.26], P = 0.43) (supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the results at 3-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the fasting C-peptide levels, (B) Comparison of the Insulin requirement

Insulin requirement

Daily insulin dose at 3-month follow up was reported in six studies (n = 242); the MSC therapy group had a significantly lower insulin requirement compared with placebo (MD = -11.56; 95% CI: [-18.63 to -4.50], P = 0.001), shown in (Fig. 4b). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 62%; P = 0.02). Heterogeneity was handled by excluding the study of Hu et al. (I2 = 0%; P = 0.88). After removing Hu et al. study from the meta-analysis, the overall MD favored MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -8.56; 95% CI: [-14.03 to -3.08], P = 0.002) (supplementary Fig. 6a). Subgroup analysis for T1DM showed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -6.69; 95% CI: [-14.83 to 1.46], P = 0.11), whereas a subgroup analysis for T2DM showed significant differences in favor of MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -14.56; 95% CI: [-22.05 to -7.08], P = 0.0001) (I2 = 53%; P = 0.10), (see supplementary Fig. 6b).

Stimulated C-peptide

The analysis of stimulated C-peptide at a follow-up period of 3 months included only two studies, in which MSC therapy was associated with significantly higher levels of stimulated C-peptide compared with placebo (MD = 0.32; 95% CI: [0.05 to 0.59], P = 0.02). The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%; P = 0.35), (supplementary Fig. 7a).

HOMA-β

Our analysis of HOMA-β at follow-up period of 3 months included only two studies and demonstrated similar levels of HOMA-β between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = 9.94; 95% CI: [-33.85 to 53.72], P = 0.66). The pooled studies showed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 90%; P = 0.002), (supplementary Fig. 7b).

HOMA-IR

HOMA-IR at a follow-up period of 3 months was reported in only two studies with a total of 81 patients. Our analysis revealed that MSC therapy was associated with significantly lower levels of HOMA-IR compared with placebo (MD = -0.25; 95% CI: [-0.42 to -0.08], P = 0.003). The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%; P = 0.68), (supplementary Fig. 7c).

Outcomes at 6-month follow up

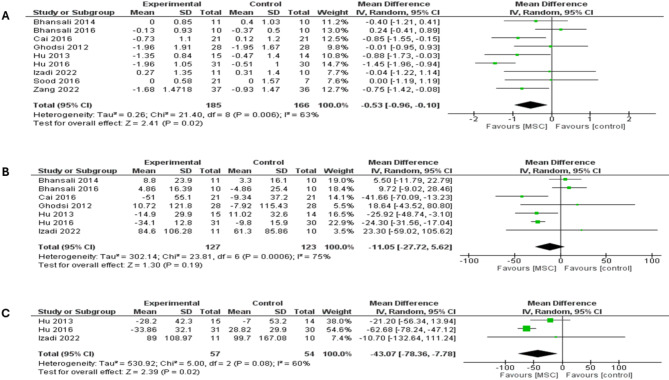

HbA1c

Nine studies reported changes in HbA1c at the 6-month follow up and revealed that MSC therapy was associated with a significantly lower HbA1c level compared with placebo (MD = -0.53; 95% CI: [-0.96 to -0.10], P = 0.02), shown in (Fig. 5a). The pooled studies displayed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 63%; P = 0.006) and were addressed by excluding Hu et al. study (I2 = 22%; P = 0.25). After excluding the study of Hu et al., the overall MD favored MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -0.38; 95% CI: [-0.72 to -0.05], P = 0.02), (supplementary Fig. 8a). MSC therapy in T1DM subgroup had a significantly favorable HbA1c outcome in comparison to placebo (MD = -0.72; 95% CI: [-1.18 to -0.26], P = 0.002) (I2 = 0%; P = 0.67). In T2DM subgroup, no differences were shown between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -0.35; 95% CI: [-1.03 to 0.32], P = 0.30) (I2 = 78%; P = 0.0004) (supplementary Fig. 8b). Furthermore, Hu et al. was removed from the subgroup analysis to handle the heterogeneity in the T2DM subgroup (I2 = 41%; P = 0.15) (supplementary Fig. 9a). Excluding the study of Hu et al., however, did not significantly affect HbA1c outcome in the T2DM subgroup (MD = -0.12; 95% CI: [-0.62 to 0.37], P = 0.62).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot showing the results at 6-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the HbA1c, (B) Comparison of the FBG, (C) Comparison of the PPBG

FBG

Seven studies were included in the analysis of FBG at a follow-up period of six months, which revealed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -11.05; 95% CI: [-27.72 to 5.62], P = 0.19), (Fig. 5b). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 75%; P = 0.0006). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM showed significantly favorable FBG outcome with MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -28.19; 95% CI: [-46.27 to -10.11], P = 0.002) (I2 = 4%; P = 0.37) (supplementary Fig. 9b). The T2DM subgroup showed comparable levels of FBG between both arms (MD = -0.98; 95% CI: [-24.35 to 22.39], P = 0.93) (I2 = 85%; P = 0.0002). Hu et al. study was removed from the subgroup analysis to handle the heterogeneity in the T2DM subgroup (I2 = 0%; P = 0.81) (supplementary Fig. 10a). Excluding the study of Hu et al., however, did not significantly affect FBG outcome in the T2DM subgroup (MD = 8.23; 95% CI: [-4.18 to 20.64], P = 0.19).

PPBG

Pooled analysis of three trials showed that MSC therapy was associated with significantly lower PPBG levels compared with placebo (MD = -43.07; 95% CI: [-78.36 to -7.78], P = 0.02), (Fig. 5c). The pooled studies demonstrated significant heterogeneity (I2 = 60%; P = 0.08). Heterogeneity was handled by removing Hu et al. 2013 study from the meta-analysis (I2 = 0%; P = 0.41) and analysis remained statistically significant, MD = -61.85; 95% CI: [-77.28 to -46.41], P < 0.00001 (supplementary Fig. 10b) [48]. A subgroup analysis based on T1DM showed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -20.39; 95% CI: [-54.16 to 13.37], P = 0.24, I2 = 0). The T2DM subgroup showed significantly favorable PPBG outcome in MSC therapy (MD = -62.68; 95% CI: [-78.24 to -47.12], P < 0.00001), (see supplementary Fig. 11a).

Fasting C-peptide

Our analysis of fasting C-peptide at a follow-up period of six months included eight studies, which revealed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = 0.25; 95% CI: [-0.12 to 0.63], P = 0.18), (Fig. 6a). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 94%; P < 0.00001). Heterogeneity was best handled by excluding the study of Hu et al. 2016 (I2 = 0%; P = 0.66). However, the overall MD did not favor either arm after removing the study from the meta-analysis (MD = 0.01; 95% CI: [-0.05 to 0.06], P = 0.83), (supplementary Fig. 11b). T1DM and T2DM subgroups showed comparable levels of fasting C-peptide between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -0.00; 95% CI: [-0.06 to 0.05], P = 0.99) (I2 = 0%; P = 0.40) and (MD = 0.44; 95% CI: [-0.10 to 0.98], P = 0.11) (I2 = 81%; P = 0.0004), (supplementary Fig. 12a). In addition, Hu et al. 2016 was excluded from the subgroup analysis to address heterogeneity in the T2DM subgroup (I2 = 0%; P = 0.98). However, did not significantly affect fasting C-peptide outcome in the T2DM subgroup (MD = 0.18; 95% CI: [-0.13 to 0.48], P = 0.25) (supplementary Fig. 12b).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot showing the results at 6-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the fasting C-peptide levels, (B) Comparison of the Insulin requirement, (C) Comparison of the stimulated C-peptide levels

Insulin requirement

Among six studies pooled analysis, results showed that MSC therapy was associated with significantly lower daily insulin dose compared with placebo after 6 months of follow-up (MD = -14.63; 95% CI: [-24.54 to -4.72], P = 0.004), see (Fig. 6b). Analysis was heterogenous (I2 = 84%; P < 0.00001) and was best addressed by excluding the study of Hu et al. 2016 (I2 = 0%; P = 0.73). Following the exclusion of the study from the meta-analysis, the overall MD favored MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -11.32; 95% CI: [-16.46 to -6.17], P < 0.0001) (supplementary Fig. 13a). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM and T2DM showed a significant insulin level outcome in favor of MSC therapy in both subgroups (MD = -10.11; 95% CI: [-19.10 to -1.12], P = 0.03) and (MD = -15.71; 95% CI: [-26.68 to -4.74], P = 0.005) (I2 = 82%; P < 0.0002), respectively (supplementary Fig. 13b). Hu et al. 2016 was removed from the subgroup analysis to address heterogeneity in the T2DM subgroup (I2 = 0%; P = 0.58). After excluding the study of Hu et al. 2016, the overall MD still favored MSC therapy over placebo in the subgroup of T2DM (MD = -11.9; 95% CI: [-18.17 to -5.64], P = 0.0002) (supplementary Fig. 13c).

Stimulated C-peptide

The analysis of stimulated C-peptide at a follow-up period of six months included four studies, in which MSC therapy was associated with comparable levels of stimulated C-peptide compared with placebo (MD = 0.26; 95% CI: [-0.43 to 0.95], P = 0.46) (Fig. 6c). The pooled studies showed non-significant heterogeneity (I2 = 45%; P = 0.14).

HOMA-β

Our analysis of HOMA-β at follow-up period of six months included four studies and showed similar levels of HOMA-β between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -0.57; 95% CI: [-34.34 to 33.19], P = 0.97), see (supplementary Fig. 14a). The pooled studies showed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 86%; P < 0.0001). Heterogeneity was addressed by removing Hu et al. 2016 study from the meta-analysis (I2 = 16%; P = 0.30). The overall MD, however, did not favor MSC therapy or placebo after excluding the study (MD = -11.55; 95% CI: [-33.46 to 10.36], P = 0.30) (supplementary Fig. 14b).

HOMA-IR

HOMA-IR at a follow-up period of six months was reported in four studies. Our results showed that MSC therapy was associated with comparable levels of HOMA-IR compared with placebo (MD = -0.31; 95% CI: [-1.05 to 0.42], P = 0.40), shown in supplementary Fig. 14c. The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 64%; P = 0.04). Heterogeneity was best addressed by excluding the study of Bhansali et al. 2014 (I2 = 38%; P = 0.20). However, the overall MD favored neither arm after removing the study from the meta-analysis (MD = -0.20; 95% CI: [-0.62 to 0.23], P = 0.36) (supplementary Fig. 14d).

Outcomes at 12-month follow up

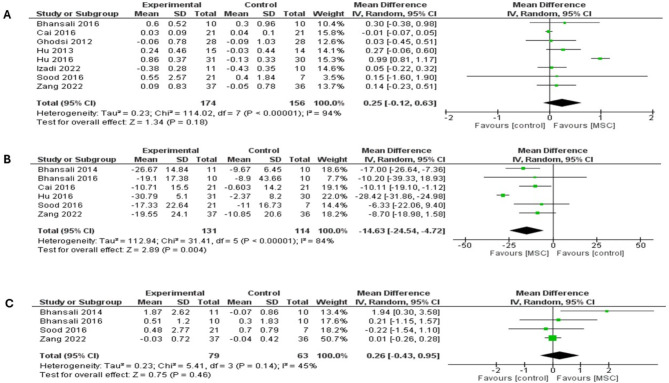

HbA1c

Pooled analysis at the 12 months included 11 trials, which showed that MSC therapy was associated with a significantly lower HbA1c level compared with placebo (MD = -0.72; 95% CI: [-1.11 to -0.33], P = 0.0003), (Fig. 7a). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 56%; P = 0.01). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM showed significantly favorable HbA1c outcome with MSC therapy (MD = -0.98; 95% CI: [-1.43 to -0.52], P < 0.0001) (I2 = 24%; P = 0.25). T2DM subgroup showed comparable levels of HbA1c between both arms (MD = -0.42; 95% CI: [-1.06 to 0.22], P = 0.20) (I2 = 72%; P = 0.006) (supplementary Fig. 15a). Heterogeneity in the T2DM subpopulation was dealt with by excluding Hu et al. 2016 (I2 = 43%; P = 0.15); however, it was not statistically significant (MD = -0.19; 95% CI: [-0.75 to 0.37], P = 0.50) (supplementary Fig. 15b).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot showing the results at 12-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the HbA1c, (B) Comparison of the FBG

FBG

Nine studies were included in the analysis of FBG at a follow-up period of twelve months, which revealed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -6.22; 95% CI: [-24.23 to 11.79], P = 0.50), illustrated in (Fig. 7b). The pooled studies displayed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 81%; P < 0.00001). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM and T2DM showed similar levels of FBG between MSC therapy and placebo in both subgroups (MD = -13.94; 95% CI: [-34.10 to 6.21], P = 0.18) (I2 = 31%; P = 0.20) and (MD = 2.16; 95% CI: [-26.65 to 30.97], P = 0.88) (I2 = 92%; P < 0.00001), respectively (supplementary Fig. 16a). To address the heterogeneity in T2DM subgroup, the study of Bhansali et al. 2016 was excluded (I2 = 0%; P = 0.70). Following the exclusion of the study from the subgroup analysis, the overall MD favored placebo over MSC therapy (MD = 11.84; 95% CI: [0.72 to 22.97], P = 0.04) (supplementary Fig. 16b).

PPBG

The analysis of PBG at a follow-up period of twelve months included three studies and demonstrated that MSC therapy was associated with significantly lower PPBG levels compared with placebo (MD = -44.32; 95% CI: [-78.98 to -9.67], P = 0.01), shown in (Fig. 8a). The analysis’ significant heterogeneity (I2 = 58%; P = 0.09) was best handled by removing Izadi et al. 2022 study (I2 = 17%; P = 0.27) from the meta-analysis. Following the exclusion of the study, the overall MD favored MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -11.32; 95% CI: [-16.46 to -6.17], P < 0.0001) (Fig. 8b). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM showed no differences between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = -8.34; 95% CI: [-96.90 to 80.21], P = 0.85). T2DM subgroup showed significantly favorable PPBG outcome in MSC therapy (MD = -61.26; 95% CI: [-76.68, -45.84], P < 0.00001) (supplementary Fig. 17a).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot showing the results at 12-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the PPBG, (B) Sensitivity analysis of the PPBG, (C) Comparison of the fasting C-peptide levels

Fasting C-peptide

Our analysis of fasting C-peptide at a follow-up period of twelve months included ten studies, which revealed significantly higher levels of fasting C-peptide with MSC therapy compared to placebo (MD = 0.24; 95% CI: [0.05 to 0.43], P = 0.01), (Fig. 8c). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 93%; P < 0.00001). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM showed significant fasting C-peptide outcome in favor of MSC therapy (MD = 0.12; 95% CI: [0.02 to 0.22], P = 0.02). T2DM subgroup showed similar levels of fasting C-peptide in both arms (MD = 0.39; 95% CI: [-0.30 to 1.08], P = 0.27) (supplementary Fig. 17b).

Insulin requirement

The analysis of insulin levels at a follow-up period of twelve months included seven studies. Our results showed that MSC therapy was associated with significantly lower insulin levels compared with placebo (MD = -16.60; 95% CI: [-25.81 to -7.39], P = 0.0004), depicted in (Fig. 9a). The significant pooled heterogeneity (I2 = 82%; P < 0.0001) was addressed by excluding the study of Hu et al. 2016 (I2 = 0%; P = 0.43). After excluding the study from the meta-analysis, the overall MD favored MSC therapy over placebo (MD = -14.50; 95% CI: [-19.45 to -9.55], P < 0.00001) (Fig. 9b). A subgroup analysis based on T1DM and T2DM showed a significant insulin level outcome in favor of MSC therapy in both subgroups (MD = -11.58; 95% CI: [-20.65 to -2.50], P = 0.01) and (MD = -21.45; 95% CI: [-32.66 to -10.24], P = 0.0002), respectively (supplementary Fig. 18a). A significant heterogeneity was detected in the T2DM subgroup, I2 = 79%; P = 0.003, which resolved after excluding Hu et al. 2016, I2 = 0%; P = 0.51; the overall MD still favored MSC therapy over placebo in the subgroup of T2DM (MD = -16.35; 95% CI: [-23.51 to -9.20], P < 0.00001) (supplementary Fig. 18b).

Fig. 9.

Forest plot showing the results at 12-month follow-up for both types of DM: (A) Comparison of the insulin requirement, (B) Sensitivity analysis of the insulin requirement, (C) Comparison of the stimulating C-peptide levels

Stimulated C-peptide

The analysis of stimulated C-peptide at a follow-up period of twelve months included three studies, in which MSC therapy was associated with similar levels of stimulated C-peptide compared with placebo (MD = 0.57; 95% CI: [-0.33 to 1.48], P = 0.21), see (Fig. 9c). The pooled studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 77%; P = 0.01). Heterogeneity was best addressed by excluding the study of Hu et al. 2016 (I2 = 0%; P = 0.40). However, the overall MD favored neither arm after removing the study from the meta-analysis (MD = 0.05; 95% CI: [-0.21 to 0.30], P = 0.72) (supplementary Fig. 19a).

HOMA-β

Three studied compared HOMA-B levels, their pooled analysis revealed comparable levels of HOMA-β between MSC therapy and placebo (MD = 23.63; 95% CI: [-2.55 to 49.80], P = 0.08) (supplementary Fig. 19b). The significant heterogeneity (I2 = 85%; P = 0.06) was best addressed by excluding the study of Bhansali et al. 2016 (I2 = 0%; P = 0.77), which resulted in overall MD favoring placebo over MSC therapy (MD = 33.56; 95% CI: [29.67 to 37.44], P < 0.00001) (supplementary Fig. 19c).

HOMA-IR

HOMA-IR at a follow-up period of twelve months was reported in four studies. Our results showed that MSC therapy was associated with similar levels of HOMA-IR compared with placebo (MD = -0.05; 95% CI: [-0.22 to 0.11], P = 0.51). The pooled studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%; P = 0.96), as shown in (supplementary Fig. 19d).

Publication bias

Two outcomes were eligible for publication bias assessment, HbA1c and fasting C-peptide. Figure 10 depicts the funnel plot analysis for both outcomes, which indicates a hint of asymmetrical effect estimate.

Fig. 10.

Funnel plot for potential publication bias analysis. The potential publication bias of the effects of MSC therapy on (A) HbA1c and (B) fasting c-peptide

Safety and adverse events of MSCs

Throughout the included trials, no serious adverse events or mortality were reported during the treatment and the follow up period. The interventional use of MSCs has been deemed reasonably safe in comparison to the standard of care. The most common adverse effect was hypoglycemic episodes; however, none were of severe or fatal magnitude. Hypoglycemia cannot be solely attributed to the intervention (MSCs) and is confounding, owing to the participants’ concomitant use of insulin and stem cell therapy. The supplementary Fig. 20 shows the meta-analysis of the eight studies that have reported the AEs outcome, revealing no significant increased incidence of AEs between both arms with an odds ratio of 1.39 (95% CI: [0.75 to 2.58], P = 0.29) and risk ratio 1.23 (95% CI: [0.81 to 1.86], P = 0.33), with pooled analysis being homogenous, I2 = 0%; P = 0.55. (supplementary Fig. 20a, b).

Among the common reported AEs included: upper respiratory tract infections, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. All of which were noted to be self-limiting and of mild to moderate severity. Additionally, procedure-related AEs were bleeding or reactions at the injection site, reported by a total of six patients from the pooled sample.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Given the epidemicity of diabetes mellitus, the search for novel efficacious treatments and/or curative modalities is an ongoing clinical endeavor. The objective of the current meta-analysis is to investigate in diabetic patients the outcomes and safety of using rudimental somatic cells that can mimic pancreatic islet cells and amplify insulin secretion and function in the body. Here, the authors present updated and RCT-exclusive meta-analytical data exploring the aforementioned intervention in type 1 and 2 diabetes and examined eight parameters for treatment efficacy after 3-, 6-, and 12-months post treatment; parameters being: HbA1c, FBG, PPBG, FCP, SCP, HOMA-IR, HOMA-B, and total daily dose of insulin.

Through this meta-analysis of thirteen pooled RCTs, we have observed a significant reduction in HbA1c, PPBG, and insulin requirement in diabetic patients consistently after six- and twelve-months post stem cell therapy. Fasting C-peptide levels, which is indicative of beta cells’ function and baseline insulin secretion, were also significantly increased after a 12-month follow-up in both types. HbA1c and insulin dosage was also reduced in T1DM subgroup analysis at the half year and one-year mark. FCP in this subpopulation increased significantly only at the 12-month follow-up. While FBG, PPBG, and insulin dosage were significantly reduced in T2DM subgroup analysis at the one-year mark; the latter two were consistently reduced at the 3- and 6-month mark as well.

No significant difference was observed in FBG between groups, albeit it was consistently lower in the intervention arm following 3, 6, and 12 months after therapy. Moreover, MSC-therapy did not prove efficacious in improving stimulated C-peptide, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-B measures.

Previous literature and systematic reviews have championed promising and favorable outcomes of stem cell therapy. Hamad et al. reviewed ten clinical trials and concluded significant improvement in HbA1c, C-peptide, and insulin production in both types of diabetic patients [34]. While Hwang et al.’s systematic review, based on 16 controlled clinical trials, reported therapeutic benefits in HbA1c, FBG, C-peptide, and insulin requirement in T2DM but only HbA1c improvement in T1DM [60].

Two studies, Mathur et al. and Pawitan et al. have systematically reviewed the outcomes of MSC-based therapy only in type 2 diabetic patients [61, 62]. Pawitan et al. in 2018 examined 25 various literature designs and reported favorable therapy outcomes in T2DM [62]. Their review included eight controlled clinical trials, six of which showed significant differences in the T2D patients receiving cell therapy with improvement in parameters like HbA1c, FBG, and C-peptide, and insulin dose reduction. In Mathur and his colleagues’ 2023 systematic review of controlled trials, they have reiterated Pawitan et al.’s finding of improved HbA1c, FBG, and C-peptide after 12 months from receiving stem cell therapy in T2DM [61]. Moreover, Ranjbaran and co-authors in their meta-analysis of observational and experimental studies among type 2 diabetic cases revealed similar findings to ours in terms of significantly reduced insulin dosage and non-significant changes in C-peptide [63]. However, their results did favor an improvement in HbA1c in T2DM which our subgroup analysis of only T2D cases did not find significant, but our overall pooled analysis did observe a statistically significant reduction through the follow-up periods in comparison to control.

Explanation of study findings

Interpreting the effectiveness of counter-diabetic therapy relies on several parameters rather than HbA1c alone and together they can better indicate disease status and therapeutic progress. To elaborate, HbA1c reflects glycemic control for a period of 12 weeks, while FBG and PPBG indicate B-cell function and the tissues’ insulin sensitivity [64]. Other measures, such as fasting and stimulated C-peptide indicate B-cells secretory capacity; fasting C-peptide reveals baseline insulin levels, while stimulated C-peptide reflects the pancreas’s ability to produce insulin in response to hyperglycemia and its insulin reserve [65, 66]. The HOMA-IR and HOMA-B modeling of the fasted-state interplay between insulin and blood glucose concentrations are a surrogate of insulin resistance and B-cell function, respectively [67].

HbA1c was reported in eleven RCTs included in this analysis, the most reported endpoint, and was found to be significantly reduced after stem cell therapy in nine trials, effectively this explains the significant HbA1c reduction observed in the pooled analysis [47–50, 52, 54–56, 59]. Meanwhile, the smaller number of accrued T2DM participants versus that of T1DM could explain the significant finding of reduced HbA1c in the intervention arms in the latter (T1DM) but not the former (T2DM) as reported in our subgroup analysis. Fasting C-peptide was the second most reported endpoint, by 10 studies (293 participants) as opposed to three studies reporting stimulated C-peptide (69 participants), the relatively small sample could have very much caused the latter’s statistical insignificance [47–56, 59]. Fasting C-peptide was significantly increased only at the one-year follow-up which might indicate the time-lapse for stem cells to differentiate and exert its paracrine effects in the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. Also, the significant increase in fasting c-peptide versus stimulated c-peptide might indicate that MSCs were effective enough to increase the baseline levels of insulin but not effective enough to cause a reactive ability of the B-cells to respond to stimulated testing or glycemic increases. However, such results still indicate that beta cell function was improved by such therapy, albeit not to a disease-free-comparable executive function, the results are indeed encouraging.

In this study, FBG was reported cumulatively in nine studies and was insignificant in comparison to both arms, however subgroup analysis for T2DM yielded a reduction in FBG readings [47–50, 52–55, 59]. Fasting blood sugar is an impressionable parameter with diurnal variability. Therefore, factors such as duration of fasting, night meal type, diet type, physical activity, insulin resistance and other medical conditions (metabolic disease, liver disease, renal impairment, pancreatic damage, vascular disease, and endocrine disease) all could have influenced this outcome [68–70]. In addition, adjunct antidiabetic medication like basal insulin and oral hypoglycemic could have confounded FBG results [68]. Oral hypoglycemic agents consumed by T2D subjects are often taken in the morning which by night their effect wanes and thus results in higher morning readings.

Insulin requirement was also a much-sought outcome among the included studies (seven trials), which in our analysis was observed to have decreased in those receiving the intervention. It seems contradictive given that change in FBG was not deemed significant, however, looking at the changes in fasting C-peptide and PPBG which were both significant and are indicative of enhanced B-cells function, it is justified. The reduction of exogenous insulin intake could be explained by MSCs promoting endogenous insulin secretion from the remaining pancreatic islet cells and their ability to increase B-cells in size and number and suppress immunity-induced inflammation [30, 71, 72]. Furthermore, MSCs have been shown to impact metabolic control, specifically enhancing insulin sensitivity through increased signaling, which could explain the significant reduction in PPBG, especially in the T2DM subgroup [67, 73]. The reduction in the total daily insulin dose observed with MSC therapy may help alleviate the financial burden and minimize the side effects associated with exogenous insulin administration.

Significance of this work

The premise of utilizing stem cells to replace diseased or dysfunctional parenchymal cells has fueled intense interest in their clinical applicability; their potential to offer a more radical solution than pharmacotherapeutic options makes them highly promising. Pharmacotherapeutic alternatives tend to offer symptomatic relief and merely alter or correct already-diseased cells as opposed to stem cells which can differentiate into cells and confer normal physiological behavior. In the case of diabetes, the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into insulin-producing cells (IPCs) and the promotion of their generation was systematically reviewed by Nemati et al., although the mechanism and the physiology behind it remains very complex, their results showed that MSCs have the efficacy to differentiate into IPCs among other mechanisms that modulate islets cells in the pancreas [74, 75].

The extrapolated meta-analytical data here represents statistics obtained from randomized controlled trials only, in an aim to deduce evidence based on the most robust literature available. Moreover, to the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis encompassing eight outcomes to evaluate treatment efficacy. Similar studies in the literature have presented inconsistent findings, however, as far as HbA1c goes, the majority have reported a significant decline post receiving stem cell therapy. He et al. in their meta-analysis of seven studies reported three outcomes only, HbA1c was significantly lowered, but FPG and fasting C-peptide were not [76]. Meanwhile, Zhang et al.’s 2020 meta-analysis has echoed our results of improvements in HbA1c, C-peptide, and insulin dosage but not FBG, however, they included a large proportion of non-randomized trials [77]. Subsequently, in a 2021 meta-analysis by Wang et al., they found no effect of MSCs therapy on HbA1c and FBG but did observe a benefit in terms of fasting C-peptide and insulin requirements, which they attributed to the inclusion of non-randomized clinical trials in their analysis [78].

The current study includes the greatest number of RCTs related to this intervention and a broader range of outcomes and thus offers more nuanced and refreshed insights. These encouraging findings could serve as a foundation and merit further necessary research in this field. The results set forth here could also be used to support research investigating the use of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of other diseases, especially those of metabolic pathology. Shamsuddin and her colleagues recently reported a systematic review spanning 18 studies of varying literature methodology looking into the efficacy of stem cells in metabolic syndrome which has shown favorable outcomes in controlling its cluster of disorders [79]. Another prospect involves adjunct therapy to pancreatic islets/whole pancreas transplantation in which stem cells improve engraftment and survival, as reported in vivo and in vitro studies [80, 81].

Yet, these more invasive modalities are met with immense challenges like those of surgical risks, graft rejection, associated immunosuppression risks, their limited accessibility in healthcare and availability of donors, insufficient clinical research backing, and finally their financial burden is too high [21, 22]. Therefore, mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy proposes an encouraging approach to diabetes management by offering an effective, safe, and longer-lasting disease control than conventional antidiabetic treatment. With several dozen clinical trials underway, as listed on the clinicalTrials.gov registry, there is optimism for a larger and well-powered meta-analysis will provide stronger statistical validation and thereby a more robust picture of mesenchymal stem cells therapeutic effectiveness [82].

Limitations

The present analysis faces a few challenges, beginning with the small size of the pooled sample of the studies which could have led to insufficient statistical power of the outcomes. Most of the clinical trials involved a small number of recruits, averaging between 50 and 60 total participants in each trial. Moreover, there is heterogeneity among the studies and the underlying cause is complex given the nature of the intervention. Different types, dosing, and routes of administration of mesenchymal cells were used among the studies, as reported in the results, which is a major confounding factor. However, given the limited number of trials and pooled participants, it is still early to provide meta-analytical data based on one source of mesenchymal stem cells. Additionally, variations in trial design, alongside inconsistencies in bias risk and quality assessment, further contribute to the weakness of the analysis and limit the reliability of the findings.

The short follow-up period reported in the studies, 12 months, fails to provide long-term outcome benefit. Only four trials have investigated outcomes beyond 12 months, limiting the evaluation of the effectiveness of MSCs for the long run. A key element of such costly and semi-invasive therapy is the longevity of its effects in the face of multiple antidiabetic modalities that are cheaper and more accessible. Prospect trials would benefit significantly from an extended follow-up time, it is essential to understand the sustainability of stem cells chronically. Trials may resort to prospective cohort study designs, focusing on the intervention participant’s outcomes only, once the primary follow up period has concluded. This would help reduce the financial burden associated with trials, as cohort study designs tend to be less cost exhaustive.

Another drawback of the included trials is the lack of diabetes specific quality of life assessment (DQOL) which provides a perspective on the receptive potential of the intervention among participants. Only Izadi et al. have evaluated subjective outcomes based on their patients [50]. They have observed a statistically significant improvement in quality of life among T1DM participants who received mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Investigating patient’s tolerability/acceptance and quality of life in relation to the intervention is imperative to delivering holistic and patient-centered care.

Conclusion

The systematic review and meta-analysis presented here aligns with the growing body of evidence suggesting that mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy is an efficacious and safe alternative to conventional therapy. In this pooled analysis, HbA1c, PPBG, fasting C-peptide, and the total daily dose of insulin were observed to improve after stem cell therapy until 12-months post treatment. Improvement in HbA1c was more evident in T1DM than T2DM, while benefit in PPBG reduction was noted in T2DM more than T1DM. By potentially enhancing insulin sensitivity, promoting the secretory and generative ability of pancreatic islet cells, and modulating tissue repair and immune response, MSCs can provide sustained therapeutic effects that is lacking in conventional therapies, which focus on symptomatic management rather than addressing the root cause of the disease. Therefore, the fight and need for more research in this field of regenerative medicine is imperative. Existing literature remains limited and underpowered to be able to draw definitive conclusions. Larger and long-term studies are essential to understand MSCs full potential in diabetic patients. Additionally, further research is required to elucidate the mechanism and physiological processes behind MSCs’ effects, which are still not entirely clear.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Qatar National Library will provide Open Access funding.

Author contributions

M Kashbour and A Abdelmalik Conceptualization, data curation, analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing– original draft, writing– review & editing. M Negmeldin and A Yassin: Conceptualization, analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing– review & editing. M Abed and E Aldieb: data curation, methodology, writing and editing. D Abdullah and T Elmozug: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, writing and editing. Y Isawi and E Hassan: data curation, methodology, resources, writing– review and editing. F Almuzghi: data curation, manuscript writing, reviewing, editing, and submission. All authors consented to the final version accepted for publication and agreed to take responsibility for its contents, sharing the obligation to address any questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of the published work.

Funding

The authors received no funding or sponsorship of any sort pertaining to this study.

Data availability

Authors are happy to oblige to reasonable requests for further data that support the findings of this study. Please address your request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical approval

No human or animal subjects were involved in this study; hence no ethics review or informed consent is warranted.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;396(10258):1204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Lond Engl. 2023;402(10397):203–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathi BK, Srivastava AK. Diabetes mellitus: complications and therapeutics. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2006;12(7):RA130–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lotfy M, Adeghate J, Kalasz H, Singh J, Adeghate E. Chronic complications of diabetes Mellitus: a Mini Review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017;13(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siu AL, U S Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes Mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):861–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenzweig JL, Bakris GL, Berglund LF, Hivert MF, Horton ES, Kalyani RR, et al. Primary Prevention of ASCVD and T2DM in patients at metabolic risk: an endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(9):3939–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harreiter J, Roden M. [Diabetes mellitus-Definition, classification, diagnosis, screening and prevention (update 2019)]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019;131(Suppl 1):6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JYC, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(25):2643–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polonsky Kenneth S. The past 200 years in diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Effect of intensive. Blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet Lond Engl. 1998;352(9131):854–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitchett D, Inzucchi SE, Cannon CP, McGuire DK, Scirica BM, Johansen OE, et al. Empagliflozin reduced mortality and hospitalization for heart failure across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Risk in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1384–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JFE, Nauck MA, et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jódar E, Leiter LA, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harreiter J, Roden M. [Diabetes mellitus: definition, classification, diagnosis, screening and prevention (update 2023)]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2023;135(Suppl 1):7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padhi S, Nayak AK, Behera A. Type II diabetes mellitus: a review on recent drug based therapeutics. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2020;131:110708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blumer I, Clement M. Type 2 diabetes, hypoglycemia, and basal insulins: Ongoing challenges. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8S2):S1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ac G, Rw G. Pancreas Transplantation of US and Non-US Cases from 2005 to 2014 as Reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR). Rev Diabet Stud RDS [Internet]. 2016 Spring [cited 2024 Jun 19];13(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26982345/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mr R, Tl E, Jc LB, Nd QRA. B, Long-term Outcomes With Islet-Alone and Islet-After-Kidney Transplantation for Type 1 Diabetes in the Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium: The CIT-08 Study. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2022 Oct 17 [cited 2024 Jun 19];45(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36250905/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.P M, C MS, C SLPRC. G, Risks and benefits of transplantation in the cure of type 1 diabetes: whole pancreas versus islet transplantation. A single center study. Rev Diabet Stud RDS [Internet]. 2011 Spring [cited 2024 Jun 19];8(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21720672/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.La SMUM, Gl F, M S, Pg T. S, A comparative analysis of the safety, efficacy, and cost of islet versus pancreas transplantation in nonuremic patients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg [Internet]. 2016 Feb [cited 2024 Jun 19];16(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26595767/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Em GL, Ea F. E. Steroid-free immunosuppression in organ transplantation. Curr Diab Rep [Internet]. 2005 Aug [cited 2024 Jun 19];5(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16033684/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Maličev E, Jazbec K. An overview of mesenchymal stem cell heterogeneity and concentration. Pharmaceuticals [Internet]. 2024 Mar [cited 2024 Jun 19];17(3). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10975472/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Clinical applications of pluripotent stem cells. and their derivatives: current status and future perspectives - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35703035/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapy-Promise and Challenges. - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33007237/

- 27.Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells in. Macular Degeneration - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29884405/

- 28.Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cardiovascular Progenitors for Severe. Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29389360/

- 29.Limbal stem-cell therapy. and long-term corneal regeneration - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20573916/

- 30.Päth G, Perakakis N, Mantzoros CS, Seufert J. Stem cells in the treatment of diabetes mellitus - focus on mesenchymal stem cells. Metabolism. 2019;90:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Expression of Pax. 4 in embryonic stem cells promotes differentiation of nestin-positive progenitor and insulin-producing cells - PMC [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC298715/

- 32.Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells to Insulin-. Secreting Structures Similar to Pancreatic Islets| Science [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1058866 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Growth inhibitors promote differentiation. of insulin-producing tissue from embryonic stem cells - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12441403/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hamad FRB, Rahat N, Shankar K, Tsouklidis N. Efficacy of stem cell application in diabetes mellitus: promising future therapy for diabetes and its complications. Cureus [Internet]. 2021 Feb [cited 2024 Jun 19];13(2). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8007200/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Clinical Efficacy of Stem Cell Therapy for Diabetes Mellitus. A Meta-Analysis - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 19]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27073927/

- 36.He J, Kong D, Yang Z, Guo R, Amponsah AE, Feng B et al. Clinical efficacy on glycemic control and safety of mesenchymal stem cells in patients with diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCT data. Vinci MC, editor. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0247662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2008 [cited 2023 Oct 5]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470712184

- 39.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Google Sheets. Online Spreadsheet Editor| Google Workspace [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 11]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/GoogleDocs/

- 42.PlotDigitizer [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 11]. PlotDigitizer: Extract Data from Graph Image Online. Available from: https://plotdigitizer.com/

- 43.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Cochrane Collaboration. RevMan 5.4.1 (Windows x64) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 11]. Available from: http://archive.org/details/rev-man-5-4-1-windows-x-64

- 45.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series [Internet]. 1st ed. Wiley; 2008. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470712184

- 47.Cai J, Wu Z, Xu X, Liao L, Chen J, Huang L, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cell with autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in established type 1 diabetes: a pilot randomized controlled open-label clinical study to assess safety and impact on insulin secretion. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu J, Yu X, Wang Z, Wang F, Wang L, Gao H, et al. Long term effects of the implantation of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells from the umbilical cord for newly-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr J. 2013;60(3):347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Z, Xu X, Cai J, Chen J, Huang L, Wu W, et al. Prevention of chronic diabetic complications in type 1 diabetes by co-transplantation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells and autologous bone marrow: a pilot randomized controlled open-label clinical study with 8-year follow-up. Cytotherapy. 2022;24(4):421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Izadi M, Sadr Hashemi Nejad A, Moazenchi M, Masoumi S, Rabbani A, Kompani F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed type-1 diabetes patients: a phase I/II randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlsson PO, Schwarcz E, Korsgren O, Le Blanc K. Preserved β-Cell function in type 1 diabetes by mesenchymal stromal cells. Diabetes. 2015;64(2):587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlsson PO, Espes D, Sisay S, Davies LC, Smith CIE, Svahn MG. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells preserve endogenous insulin production in type 1 diabetes: a phase I/II randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2023;66(8):1431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhansali A, Asokumar P, Walia R, Bhansali S, Gupta V, Jain A, et al. Efficacy and safety of autologous bone marrow-derived stem cell transplantation in patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Cell Transpl. 2014;23(9):1075–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhansali S, Dutta P, Kumar V, Yadav MK, Jain A, Mudaliar S, et al. Efficacy of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell and mononuclear cell transplantation in type 2 diabetes Mellitus: a Randomized, Placebo-controlled comparative study. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26(7):471–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu J, Wang Y, Gong H, Yu C, Guo C, Wang F, et al. Long term effect and safety of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells on type 2 diabetes. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(3):1857–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zang L, Li Y, Hao H, Liu J, Cheng Y, Li B, et al. Efficacy and safety of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes: a single-center, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sood V, Bhansali A, Mittal BR, Singh B, Marwaha N, Jain A, et al. Autologous bone marrow derived stem cell therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus - defining adequate administration methods. World J Diabetes. 2017;8(7):381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skyler JS, Fonseca VA, Segal KR, Rosenstock J. Allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells in type 2 diabetes: a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalation Safety and Tolerability Pilot Study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(9):1742–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghodsi M, Heshmat R, Amoli M, Keshtkar AA, Arjmand B, Aghayan H, et al. The effect of fetal liver-derived cell suspension allotransplantation on patients with diabetes: first year of follow-up. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50(8):541–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang G, Jeong H, Yang HK, Kim HS, Hong H, Kim NJ, et al. Efficacies of stem cell therapies for functional improvement of the β cell in patients with diabetes: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Int J Stem Cells. 2019;12(2):195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathur A, Taurin S, Alshammary S. The safety and efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of type 2 Diabetes- A literature review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2023;16:769–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pawitan JA, Yang Z, Wu YN, Lee EH. Towards standardized stem cell therapy in type 2 diabetes Mellitus: a systematic review. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;13(6):476–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ranjbaran H, Mohammadi Jobani B, Amirfakhrian E, Alizadeh-Navaei R. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell therapy on glucose levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12(5):803–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic targets: standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(Supplement1):S73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones AG, Hattersley AT. The clinical utility of C-peptide measurement in the care of patients with diabetes. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2013;30(7):803–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]