Abstract

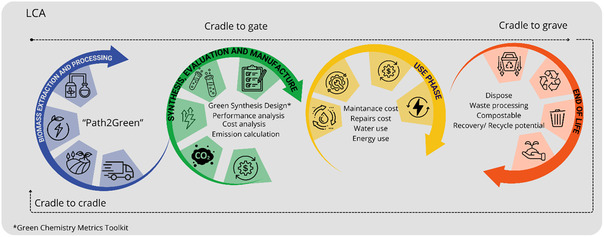

While the world remains dependent on fossil fuels in nearly every aspect of life, unused biomass is piling up as waste, despite its significant potential for valuable applications—a critical missed opportunity for sustainable innovation. Phase change materials (PCMs) have emerged as a pivotal technology in the urgent transition toward carbon neutrality, especially considering that heating and cooling consume nearly half of global energy expenditure. This comprehensive review advances the scientific understanding of sustainability and circularity in PCM fabrication by providing a strategic framework for developing composites from renewable resources. This framework involves the introduction of a novel classification system (types 0–3) for biomass‐derived PCMs based on their levels of modification, enabling a comparison of material sources, performance metrics, and environmental impacts. By showing recent innovative developments in PCM shape stabilization, thermal conductivity enhancement, and leakage protection, it critically highlights the opportunities to replace conventional materials with innovative biomass‐derived alternatives, such as biomass‐derived carbons and polymers. Furthermore, the study integrates tools aligned with the Principles of Green Chemistry to aid the fabrication of truly sustainable materials, helping to guide researchers through material selection, process optimization, and the comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impact associated with their use and disposal.

Keywords: biopolymers, carbon materials, composite, encapsulation, phase change material

This comprehensive review advances the scientific understanding of sustainability and circularity in phase change material (PCM) fabrication by providing a strategic framework for developing composites from abundant, renewable resources. By screening biomass‐derived PCMs, carbons, and biopolymers, a roadmap is outlined for the development of sustainable composites with enhanced thermal conductivity and reduced leakage for thermal energy storage.

1. Introduction

The urgent need for sustainable materials and processes has become paramount as humanity faces unprecedented environmental challenges, including climate change, resource depletion, and waste accumulation. The continued reliance on fossil fuel‐based materials has led to cascading environmental impacts, from greenhouse gas emissions to microplastic pollution in our oceans and soil.[ 1 ] This sustainability imperative has fundamentally transformed materials science research, driving innovation toward biobased alternatives that can and should replace petroleum‐derived products.[ 2 ] Beyond its environmental benefits, this transformation is also driven by economic factors, as volatile fossil fuel prices and supply chain disruptions highlight the risks of petroleum dependency. Thermal energy storage (TES) materials are at the forefront of this transformation, playing a crucial role in renewable energy systems, energy‐efficient buildings, and sustainable industrial processes. These materials are particularly important as they address one of the key challenges in the transition to renewable energy: the need to efficiently store and manage thermal energy to bridge the gap between energy availability and demand.[ 3 , 4 ]

TES technologies can broadly collect heat from any source and store it through three distinct mechanisms, which leverage different physical and chemical properties. The simplest mechanism is sensible heat storage (SHS), which utilizes the heat capacity of a material to collect heat as its temperature increases. It requires a wide range of temperatures to achieve reasonable storage capacity, but it is inexpensive, easily available, and already implemented in industry. SHS examples include alloys, rocks, molten salts, and thermal oils.[ 5 ]

Latent heat storage (LHS) operates under almost isothermal conditions, offering significantly higher energy density by utilizing phase change materials (PCMs) that absorb or release energy during phase transition (solid–solid, solid–liquid, or liquid–gas). Common PCMs include paraffin waxes,[ 6 ] fatty acids,[ 7 ] salt hydrates,[ 8 ] polymers,[ 9 ] metal alloys,[ 10 ] sugar alcohols,[ 11 ] and organic salts,[ 12 , 13 ] each offering different melting points and thermal properties to suit various applications.[ 12 , 14 ] However, each of these materials suffers specific drawbacks that hinder its practical applications: flammability, low stability, low thermal conductivity, phase separation, supercooling, or high price are among the most common.

The third mechanism, thermochemical heat storage (THS), leverages reversible chemical reactions to store and release thermal energy or to generate electricity.[ 5 ] This method offers the highest theoretical energy density among all thermal storage approaches and can store heat for extended periods with minimal heat losses. THS includes chemical reaction storage utilizing: 1) hydration/rehydration reactions (e.g., CaO/H2O; MgO/H2O), 2) redox reactions (e.g., BaO/O2; CoO/O2), and 3) carbonization (e.g., CaO/CO2; MgO/CO2). Secondly, THS storage involves chemical adsorption (chemisorption) between metal halides and NH3 (e.g., CaCl2/NH3) or salt hydrates and H2O (e.g., MgCl2/H2O). Thirdly, THS encompasses chemical absorption (liquid‐gas absorption), including two‐phase absorption (e.g., H2O/NH3) or three‐phase absorption (e.g., LiCl solution + crystal/H2O).[ 15 ]

Recently, researchers have recognized that integrating all three thermal modes (sensible, latent, and thermochemical) into a single system can achieve exceptionally high TES capacities. At first, researchers combined two materials into a coworking matrix, e.g., a high‐density polyethylene (HDPE) as a PCM, and MgSO4·7H2O as a thermochemical material, with this system operating from 30 to ≈150 °C.[ 16 ] A recent breakthrough revealed that the eutectic mixture of boric acid and succinic acid can undergo simultaneous melting and dehydration, making it the first known material to exhibit trimodal TES behavior with an exceptionally high energy storage capacity of almost 400 J g−1.[ 17 ]

Despite significant progress in materials and relevant TES technologies, the vast majority of these materials are derived from fossil fuels. Replacing fossil fuel‐based chemicals, materials, and products with biomass‐derived alternatives is one of the strategies that can help to achieve net zero emission targets. Current efforts to achieve this goal have extended beyond academic institutions and scientific research, encompassing state agencies, future policy development, and the regulation of rights associated with the acquisition, processing, and utilization of biomass. An example is the Biomass Strategy adopted by the UK, the first country whose government has undertaken a policy aimed at utilizing sustainable biomass across multiple sectors of its economy.[ 18 ] Globally, sustainable consumption and production is prioritized through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the United Nations,[ 19 ] which serve as a framework guiding the decision‐making processes for numerous governments.

The growing demand for biomass‐derived products is driving the development of advanced technological solutions for breaking down biomass (including biomass waste) into value‐added chemicals. Biorefineries play an important role in the production and delivery of such components. With the increasing number of operational facilities, valuable biomass‐derived products will become more readily available for the development of sustainable materials and products, including those for TES.

With this review article, we aim to focus on PCMs that hold significant potential in a variety of applications, from cold chain storage to large‐scale renewable energy storage, while also offering strong prospects of being sourced from renewable biomass. Choosing the ideal PCM for TES requires carefully balancing various factors, such as operating temperature, high energy storage capacity, thermal and chemical stability, cost‐effectiveness, product durability, and overall sustainability. Nazir et al. organized this selection process by proposing a pyramid model for PCMs (Figure 1 ).[ 20 ] The pyramid's foundation addresses cost, regulatory compliance, and toxicity barriers. The middle section emphasizes thermal and physical properties that influence performance, while also accounting for reliability and environmental factors, such as cycling stability and material degradation. At the top are secondary considerations, such as user experience and convenience.

Figure 1.

General selection characteristics of PCMs for TES applications proposed by Nazir et al. Adopted with permission.[ 20 ] Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

Even though PCMs have been investigated for nearly 50 years, a strong emphasis on their overall sustainability, including their production and utilization, has only become widespread recently. Many PCMs with a non‐renewable character, such as paraffin waxes, have the potential to be substituted with ones from renewable resources, such as vegetable oils, animal fats, or natural waxes.[ 21 , 22 ] Moreover, organic PCMs often suffer from insufficient thermal conductivity or inherent leakage problems, which has directed research toward the construction of composites. Combining PCMs with thermally conductive fillers, such as carbon materials (carbon nanotubes,[ 23 ] graphene,[ 24 , 25 ] graphene oxide,[ 26 ] graphite,[ 26 ] carbon nitride[ 27 ]) or boron nitride,[ 28 ] has emerged as a solution to enhance organic materials’ thermal conductivity and prevent leakage by the development of shape‐stabilized materials. Moreover, encapsulation of the PCM in a shell made of polymer, silica, alumina, metals, or hybrid material is a strategy that can minimize the leakage problem. Materials addressing both of these issues have a strong potential to be sourced from biomass, giving rise to fully biobased composites, paving the way toward new combinations in the field of material science.

Beyond developing PCMs from biomass‐derived materials, researchers are also creating biomimetic PCMs that mimic natural biological systems.[ 29 ] These include structures mimicking those known from nature that can further provide additional functionality to PCMs (e.g., honeycomb structures with excellent mechanical properties and high porosity or structures inspired from spider webs providing fibers with strong adhesion and tensile abilities) as well as working themselves in terms of thermal management. For more insights into nature‐inspired strategies, we recommend referring to the excellent review article by Liu et al.[ 30 ]

With the increasing awareness of the development of sustainable materials,[ 31 ] we aim to highlight the idea of biomass‐derived PCM composite fabrication as an overall concept using biomass‐derived precursors at all stages. This review examines widely available bioderived materials for TES applications, including biomass‐derived PCMs, biomass‐derived carbons for thermal conductivity enhancement, and natural polymers suitable for the encapsulation process to create fully bioderived, efficient composite materials that operate across various temperature ranges. Finally, we will highlight the most effective tools for assessing the overall sustainability of materials and supporting decision‐making in selecting specific materials and unit operations during the fabrication process.

2. Biomass‐Derived PCMs

Organic PCMs encompass a diverse range of compounds, including paraffin waxes, alkanes, fatty alcohols, acids, esters, ureas, amides, urethanes, carbonates, ionic liquids/organic salts, and sugars and their derivatives. Some of these materials have a strong potential to be fully or partially developed using renewable resources. The costs associated with biomass processing and upgrading can still be less competitive compared to petroleum‐based alternatives, taking into consideration, among other factors, the undeveloped feedstock delivery chains, the precursors’ seasonal and geographical availability, and the necessary investment in infrastructure and technologies.[ 21 , 32 ] Nevertheless, the ongoing advances in sustainable biomass valorization methods, including separation and purification steps and raw material acquisition, as well as making use of waste (e.g., waste cooking oil), make biomass‐derived chemicals, including bio‐PCMs, more affordable and practical, fostering a circular economy and promoting more sustainable TES applications.[ 33 ]

To categorize and compare bio‐PCMs, based on their source, environmental impact, performance, and cost, we classified bio‐PCMs into four types: 0, 1, 2, and 3, depending on their modification level (Figure 2 ). Type 0 bio‐PCMs are raw, unmodified mixtures of various compounds mainly extracted from vegetable oils, waxes, or fats. Type 1 bio‐PCMs are single compounds isolated from these mixtures, including fatty acids, fatty alcohols, and sugar alcohols. Their concentration in nature is usually low, so they are mostly obtained by modification of other, more abundant feedstocks (triglycerides or lignocellulosic biomass). Type 2 bio‐PCMs include compounds that are unlikely to occur in nature. These are derivatives (esters, amides, urethanes, carbonates, sulfates, or carbamates) of type 1 bio‐PCMs. The degree of chemical modification of this group is the highest. Type 3 bio‐PCMs are eutectic mixtures of compounds of different types. The increasing number of unit operations performed for each successive material type is accompanied by introducing improvements to overcome the limitations of the precursor. As we provide a state‐of‐the art review, we focus only on materials already recognized as applicable to TES in literature.

Figure 2.

Biomass‐derived PCMs categorized into four types, depending on their modification level.

2.1. Type 0 Bio‐PCMs

Type 0 PCMs (Table 1 ) consist of raw, unrefined natural substances that typically contain a mixture of compounds, such as fatty acid triglycerides, sterols, waxes, fatty acids, fatty acid esters, alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, and other trace components.[ 34 , 35 ] To obtain these compounds, only the extraction (cold pressing, solvent extraction, or mechanical expelling) of vegetable oil from its biological source is usually required, preceded by several operations (hulling, crushing, pressure‐filtration, etc.) at very limited cost.[ 21 ] In some cases, such as beeswax, no additional operations are required. It is essential to select the extraction technique that minimizes environmental impact while maximizing yield.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of TYPE 0 bio‐PCMs.

| Type 0 bio‐PCMs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural oils, waxes, or fats | T m [°C] | ΔH f [J g−1] | Isolation process | References | |

| Shellac wax | 51–82 | 148 | Extracted from shellac produced by Kerria lacca insects | [237] | |

| Beeswax | 38–68 | 206 | Produced in beehives by honeybees | [39, 238] | |

| Calophyllum inophyllum seed oil | −6–14 | 184 | Extracted from the tamanu tree's kernel | [239] | |

| Avocado oil | −20–12 | 70 | Extracted from avocado | [21] | |

| Argan oil | −30–7 | 52 | Extracted from fruit of the argan tree | ||

| Coconut oil | 6–32 | 133 | Extracted of coconut kernel | ||

| Jojoba oil | −5–18 | 142 | Extracted from jojoba kernel | ||

| Soybean oil | −33–(−12) | 50 | Extracted from soybean | ||

| Triglycerides | Glycerol tripalmitate | 59 | 186 | Extracted from plants oils, fats, waxes | [240] |

| Glycerol tribehenate | 82 | 214 | [241] | ||

Vegetable and animal oils and fats remain key renewable resources for the chemical industry. Over the last decade, their industrial use increased from 31 to 51 million metric tons annually.[ 36 ] These abundant raw materials serve as a crucial resource for the sustainable production of biobased PCMs, supporting broader industrial and environmental goals.

The composition and resulting thermal properties of materials derived from oleochemical feedstocks, such as melting and crystallization temperatures and related enthalpies, depend on external factors, such as environmental conditions and extraction methods.[ 37 ] Due to their multicomponent nature, type 0 bio‐PCMs often exhibit wider melting ranges,[ 38 ] with multiple melting and crystallization peaks, making them suitable for applications where a precise melting range is not essential. Their inherent nontoxicity and reduced flammability make them safe for use in building materials, solar air heaters, and solar water heaters.[ 21 ]

Recently, Hammami et al.[ 21 ] characterized the thermal properties of 45 vegetable oils as PCMs. Most of the oils gave ΔH f values <100 J g−1 and wide melting ranges (<50 °C), but there were exceptions that gave higher enthalpies of fusion, such as jojoba oil, palm kernel oil, and coconut oil with ΔH f values of 142, 140, and 133 J g−1 respectively. Dinker et al.[ 39 ] studied beeswax with a high enthalpy of fusion reaching 206 J g−1, measured over a broad temperature range (from 38 to 61 °C), for low‐temperature thermal storage as an alternative to synthetic paraffins. While natural oils and waxes are generally thermally stable, their variable compositions can limit their consistency and reliability in specific applications. Furthermore, these materials often have lower thermal conductivity, undergo volume changes during phase transitions, are flammable, and may be expensive or difficult to obtain, as is the case with certain seed oils. Animal fats, on the other hand, are highly susceptible to oxidation and hydrolysis, which leads to rapid degradation and reduced thermal efficiency over time, thus limiting their shelf life.[ 37 ]

Oils and waxes are mainly composed of triglycerides, and some, such as cocoa butter, consist entirely of them. Hence, we classified triglycerides as type 0 bio‐PCMs. Ravotti et al.[ 40 ] recently highlighted the potential of triglycerides as effective candidates for TES applications by characterizing their thermal properties individually. These esters offer a diverse melting temperature range from below 0 °C to above 90 °C and in some cases exhibit ΔH f values exceeding 200 J g−1. However, a key challenge remains managing polymorphism (the ability of triglycerides to crystallize in different forms), which can affect their thermal stability and consistency. Overcoming this limitation is crucial to maximizing the practical use of triglycerides in TES systems. Further modification of natural oils through different approaches can improve their thermal properties and stability, further enabling their efficient operation in various applications.

2.2. Type 1 Bio‐PCMs

Biomass is a source of valuable compounds, including fatty alcohols, fatty acids, sugar alcohols, and lactones, that can serve as PCMs for TES applications. However, these compounds often appear in low concentrations in nature, so their extraction and purification can be costly. Type 1 bio‐PCMs are preferably derived from more abundant feedstocks (triglycerides and lignocellulosic biomass) through chemical transformations, including hydrolysis, transesterification, and hydrogenation, followed by additional purification steps, such as precipitation or crystallization (Table 2 ). Fatty acids, for instance, are naturally present in vegetable oils and animal fats. Conventional chemical hydrolysis of triglycerides using acidic or basic catalysts can be utilized or hydrothermal, enzymatic, or biochemical processes that offer improvements by avoiding large amounts of contaminated waste and vessels made from expensive corrosion‐resistant materials.[ 41 ] Other valuable feedstocks for fatty acids are waste animal fat, non‐edible plant oils, and used cooking oil (UCO).[ 32 ] For example, Kumar and Negi hydrolyzed UCO with a lipase from Penicillium chrysogenum, obtaining C18 fatty acids with 22% yield.[ 42 ]

Table 2.

Thermal properties of TYPE 1 bio‐PCMs.

| TYPE 1 bio‐PCMs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group of compounds | Compound | T m [°C] | ΔH f [J g−1] | Origin | Production processes | References |

| Fatty acids | Capric acid | 32 | 169 | Triglyceride |

Extraction from plant natural oils Hydrolysis of triglycerides, with removal of glycerol |

[43, 44, 242] |

| Stearic acid | 55 | 159 | ||||

| Fatty alcohols | 1‐Hexadecanol | 49 | 237 | Fatty acids |

Hydrogenation of fatty acids Hydrogenation of methyl esters of fatty acids |

[47] |

| 1‐Octadecanol | 57 | 248 | ||||

| Sugar alcohols | Erythritol | 119 | 333 | Starch, fruits such as melon, watermelon, pears, grapes; and in fermented foods, such as cheese, soy sauce | Fermentation of glucose | [49, 53] |

| Mannitol | 166 | 284 |

Starch, cellulose and hemicellulose, fructose, mushrooms, brown algae, tree bark |

Catalytic/enzymatic hydrogenation of fructose Fermentation of fructose |

||

| Xylitol | 92 | 233 | Hardwoods, softwoods, agricultural waste from processing maize, wheat, rice |

Catalytic/enzymatic hydrogenation of xylose Fermentation of xylose |

||

Fatty acids have been extensively studied due to their favorable thermal properties. They demonstrate melting points ranging from 32 °C for capric acid[ 43 ] to 55 °C for stearic acid (90% purity),[ 44 ] making them well‐suited for low‐temperature applications. Additionally, they have high enthalpies of fusion (some sources report enthalpy values for stearic acid as high as 258 J g−1 [ 45 ]), further underscoring their thermal storage potential. Fatty acids offer durability, withstanding thousands of thermal cycles (melting and freezing) without significant degradation in performance.[ 44 ] Other benefits include low supercooling, a narrow melting range, and stability. However, fatty acids face drawbacks, such as low thermal conductivity (0.2388 W m−1 K−1 for C12 and 0.3079 W m−1 K−1 for C18), an unpleasant odor after repeated cycles,[ 20 ] potential metal corrosion,[ 46 ] flammability, and a high sublimation rate. The phase change temperature and latent heat of PCMs can be influenced by a number of factors, so values of the thermal properties of fatty acids, as well as other bio‐PCMs reported in the literature, can vary slightly.

Fatty alcohols avoid some of the issues assigned to fatty acids, such as odor and corrosiveness. An example is the group of common fatty alcohols studied by Q. Zhang et al.[ 47 ] which exhibited melting points varying from 23 °C for dodecanol to 57 °C for octadecanol, with enthalpies of fusion up to 248 J g−1.[ 47 ] Depending on the oil feedstock, fatty alcohols with different chain lengths are produced. Nonetheless, their production is more complex than that of fatty acids, as it involves hydrogenation of fatty acids, fatty acid methyl esters (FAME), or fatty acid wax esters (FAWE).[ 48 ] These transformations require metal catalysts and high energy consumption. An alternative is the biological route for producing fatty alcohols in the presence of enzymes.[ 48 ] These processes are more eco‐friendly, being metal‐free, energy‐efficient, and not requiring high pressure, but still require optimization for industrial‐scale applications.

Sugar alcohols, with melting points reaching 190 °C and enthalpies up to 350 J g−1 for galactitol, represent a unique subset of medium‐temperature PCMs, especially suitable for renewable energy storage.[ 49 ] They are commonly present in a variety of fruits and vegetables, while their industrial production involves the catalytic hydrogenation of sugars. The recent drive for advances in chemical transformations that enable milder reaction conditions,[ 50 ] alongside biotechnological approaches such as microbial fermentation, has contributed to the sustainable development of sugar alcohols.[ 51 ] Despite favorable thermal properties, including the highest enthalpies of fusion among organic compounds that melt in the intermediate temperature range, sugar alcohols encounter challenges, such as severe supercooling and crystallization issues, which hinder complete heat retrieval and their operational stability. These materials undergo 10%–15% expansion upon melting,[ 52 ] while their solid‐state thermal conductivities range from 0.37 to 1.31 W (m·K)−1 for xylitol, depending on the measurement technique.[ 53 , 54 ] Improvements to overcome crystallization challenges and enhance the stability of sugar alcohols over repetitive melting and crystallization are needed to fully utilize the potential of these renewable materials for broader PCM applications. However, their supercooling issue could be used as an advantage in applications such as seasonal energy storage.[ 55 ]

Carbohydrates, which possess hydroxyl‐group‐rich structures similar to sugar alcohols, along with significant energy storage density, also suffer from severe supercooling. Recently, Gaida et al. presented a novel strategy to reduce supercooling in polyol, carbohydrate‐derived PCMs by converting them into organic salts with anions that provide additional H‐bonding.[ 56 ] Nevertheless, carbohydrates have been mostly studied only as PCM additives.[ 57 , 58 ]

2.3. Type 2 Bio‐PCMs

While type 1 materials represent an improvement over raw type 0 bio‐PCMs, several challenges remain for the various groups of materials, including corrosion issues, supercooling, thermal stability, and operational temperature range. Some of these issues can be solved by further chemical modification of type 1 bio‐PCMs producing type 2 bio‐PCMs (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Thermal properties of TYPE 2 bio‐PCMs.

| Type 2 bio‐PCMs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | T m [°C] | ΔH f [J g−1] | Origin | Production method | References | ||

| Biomass | Fossil fuelsa ) | ||||||

| Monoesters | Decyl eicosanoate | 41 | 232 | Fatty alcohol, fatty acid | – | Esterification | [65] |

| Tetradecyl octadecanoate | 49 | 222 | [243] | ||||

| Octadecyl eicosanoate | 65 | 226 | [244] | ||||

| Threo‐dihydroxystearic esters | 52–77 | 137–234 | [37] | ||||

| Diesters | Glycol distearate (Cutina AGS) | 60 | 213 | Fatty acid, ethylene glycol | – | Esterification | [245] |

| Dihexadecyl‐1,10‐decanedioate | 58 | 214 | Sebacic acid, fatty alcohol | – | Esterification | [61] | |

| Dihexadecyl‐1,8‐ octanedioate | 55 | 216 | Octanedioic acid, fatty alcohol | [60] | |||

| Dioctadecyl tartrate | 82 | 221 | Fatty alcohol, Tartaric acid | – | [75] | ||

| Didocanosyl tartrate | 94 | 203 | |||||

| Neopentyl glycol dipalmitate | 35 | 118 | Fatty acid | Neopentyl glycol | [62] | ||

| Polyol esters | Erythritol tetrapalmitate | 22 | 201 | Sugar alcohols, fatty acids | – | [246] | |

| Xylitol pentastearate | 32 | 205 | [72] | ||||

| Galactitol hexastearate | 50 | 251 | [73] | ||||

| FAME | Methyl stearate | 36 | 204 | Plant oil, methanol | – | Transesterification | [64] |

| Lactones | ε‐Caprolactone | −1.6 | 122 | 6‐Hydroxyhexanoic acid | Cyclohexanone | Lactonization/Baeyer–Villiger oxidation | [87] |

| γ‐Valerolactone | −32 | 110 | Levulinic acid | – | Catalytic hydrogenation and dehydration | ||

| Carbonate | Tetradecyl carbonate | 34 | 227 | Fatty alcohol, diethyl carbonate | – | Carbonate interchange reaction | [77] |

| Octadecyl carbonate | 52 | 223 | |||||

| Sulfones | 1‐(Decyl sulfonyl) decane | 89 | 204 | Fatty sulfides | – | Oxidation | [76] |

| 1‐(Octadecyl sulfonyl) octadecane | 109 | 218 | |||||

| Fatty amineb) | 1‐Dodecylamine | 27 | 261 | Fatty nitriles | – | Hydrogenation | [79] |

| 1‐Hexadecylamine | 45 | 280 | |||||

| Monoamide | Fatty acid amides from sunflower oil and dodecylamine | 49 | 140 | Sunflower oil, fatty acid | – | Condensation | [80] |

| N‐hexadecyl‐decanamide | 79 | 201 | Fatty acids | Amine | [79] | ||

| Diamide | N, N′‐(ethane‐1,2‐diyl) dipalmitamide | 151 | 152 | [247] | |||

| N, N′‐(octane‐1,8‐diyl) distearamide | 144 | 218 | [81] | ||||

| Dicarbamate | Dioctadecyl hexane‐1,6‐dicarbamate | 121 | 200 | Fatty alcohol | Diisocyanate | Alcoholysis | [82] |

| Dioctadecyl phenyl‐1,6‐dicarbamate | 151 | 135 | |||||

| Organic salts | Choline tartrate | 151 | 129 | Tartaric acid, choline chloridec ) | – | Anion metathesis, acid‐base reaction | [248] |

| 2‐hydroxyethylammonium stearate | 76 | 176 | Fatty acid | Amine | acid‐base reaction | [249] | |

A compound derived from fossil fuels or produced through reaction with a fossil fuel–based compound.

Although amines are precursors of amides and could be classified as type 1, they do not occur naturally and were ultimately classified as type 2 as typically synthetic compounds.

Despite that choline chloride can theoretically be extracted directly from a biomass, it is industrially produced from fossil fuels.

Type 2 bio‐PCMs include esters, amides, urethanes, carbonates, sulfates, carbamates, and organic salts/ionic liquids. Unlike their precursors, these derivatives are rarely present in nature and are primarily produced through synthetic processes. Their production involves additional processing steps and unit operations, which increase both costs and environmental impact. However, these derivatives offer PCMs with much broader melting temperatures.

An important group of type 2 bio‐PCMs are aliphatic esters, particularly those derived from fatty acids, fatty alcohols, diols, or diacids, which have been extensively studied by Aydin et al.[ 59 , 60 , 61 ] Sari,[ 62 , 63 ] and Ravotti.[ 64 , 65 ] These esters are useful as low‐temperature PCMs with low corrosivity, little unpleasant odor, and improved thermal stability compared to fatty acids. Common synthetic methods include Fischer esterification and transesterification, which can both be operated at low cost, offering high substrate flexibility.[ 66 , 67 ] While there are numerous reviews detailing aliphatic esters,[ 68 ] certain examples stand out for their exceptional properties, such as decyl eicosanoate, which boasts an enthalpy of 232 J g−1.[ 65 ] However, polymorphism remains an issue, albeit less pronounced than in triglyceride‐based PCMs.[ 69 ]

Another group of facile bio‐PCMs for low‐temperature applications are FAMEs. These compounds are typically produced through oilseed extraction, followed by a subsequent alkali‐catalyzed reaction between the plant oils and methanol.[ 70 ] An example is methyl stearate with a melting point of 36 °C and ΔH f value of 204 J g−1, reported by Ravotti et al.[ 64 ]

Esterification of sugar alcohols with fatty acids to give the corresponding esters (erythritol tetrapalmitate,[ 71 ] xylitol pentastearate,[ 72 ] or galactitol hexastearate[ 73 ]) addresses the challenges of supercooling and low stability, which are often observed for sugar alcohols. The highest enthalpy, reaching 250 J g−1, along with a melting point of 50 °C, was reported for galactitol hexastearate, showing a decrease in stability (≈17%) over 1000 heating and cooling cycles.[ 73 ] Despite an improvement in cycling stability, this modification offers materials with melting temperatures similar to that of fatty acids rather than sugar alcohols, limiting their practical use to low‐temperature applications.

In addition to addressing the limitations of the precursor materials, many efforts have focused recently on studying the effect of different functional groups that impact the melting range, thereby enhancing the potential applications of PCMs.[ 74 ] For instance, we have demonstrated that by introducing hydroxyl groups into the fatty esters by using renewable tartaric acid as the core, it is possible to increase the melting temperature relative to the compound without —OH groups. Ester‐derived behenyl alcohol melts at 94 °C with an enthalpy of 203 J g−1, demonstrating excellent stability over 500 heating and cooling cycles.[ 75 ]

Another class of promising PCMs for medium‐temperature TES applications are sulfones, which typically have slightly higher phase transition temperatures, as reported for octadecyl sulfone (T m = 109 °C, ΔH f = 200 J g−1).[ 76 ] These compounds can be produced by simple solvent‐free oxidation of the fatty sulfides using hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid, but the challenge remains the cost of the fatty sulfides.

On the other hand, carbonates with melting points ranging from −2 °C for decyl carbonate to 53 °C for octadecyl carbonate are dedicated for low‐temperature TES.[ 77 ] These values are significantly lower than those of fatty acids, fatty alcohols, n‐alkanes, and wax esters with similar carbon chain lengths. Most carbonates display no supercooling, sharp phase transitions, and high latent heats, reaching up to 227 J g−1 for tetradecyl carbonate. As renewable PCMs, they provide an alternative to paraffin wax.

It should be noted that processing compounds derived from biomass is not always environmentally sustainable. Some reactions require fossil fuel inputs or result in products with higher toxicity than their original precursors, such as the fatty amines derived from fatty acids. Due to their limited natural occurrence, we classified fatty amines as type 2 materials. These amines are typically synthesized by reacting ammonia with fatty acids at high temperatures in the presence of a metal oxide catalyst to give fatty nitriles, which are then hydrogenated using a Raney–Nickel catalyst.[ 78 ] Fatty amine transition temperatures range from 26 °C for 1‐aminotridecane to 72 °C for dioctadecylamine, with a minimal supercooling effect of less than 10 °C.[ 79 ] High enthalpies of fusion reaching 300 J g−1, despite a decrease after three cycles, remained nearly unchanged over the next 50 cycles, ranking fatty amines among the organic PCMs with the highest latent heat, comparable to that of sugar alcohols.

Recognizing the potential of amines, Poopalam et al. synthesized a series of monoamides and diamides. The monoamide N‐hexadecyl‐decanamide exhibited a melting point of 79 °C and an enthalpy of 201 J g−1.[ 80 ] However, given the availability of more sustainable PCMs in this temperature range, more interesting are diamides with higher melting points >100 °C. Solvent and catalyst‐free high‐temperature (160–170 °C) condensation between C2–C10 diamines and C12–C18 fatty acids gave diamides with melting points in the intermediate temperature range (T m of N,N’‐(octane‐1,8‐diyl)distearamide is 144 °C; ΔH f = 218 J g−1) and remarkable stability over 100 heating and cooling cycles.[ 81 ]

Another group of PCMs for this temperature range are carbamates, synthesized by reacting diisocyanates with fatty alcohols.[ 82 ] Some of the authors of this review recently demonstrated a series of carbamates, with dioctadecyl hexane‐1,6‐dicarbamate exhibiting a melting point of 121 °C and a high enthalpy of 200 J g−1, addressing the gap in PCMs with melting points above 100 °C. A drawback of this approach is the reliance on diisocyanates, the production of which involves phosgene. To mitigate the environmental impact, the authors explored an alternative synthetic route with the use of carbonates and fatty amines and analyzed the potential for product recycling and the costs of carbamate production, which accounted for $7.90 per kWh of stored energy per cycle.

Another group of versatile materials used in various PCM applications are polymers.[ 83 ] Among them, HDPE stands out, with an impressive enthalpy of ≈230 J g−1, at a melting point of 130 °C, and stability over 500 heating and cooling cycles.[ 84 ] Traditional HDPE production involves the polymerization of ethylene monomer using free radical or addition polymerization, often catalyzed by a Ziegler‐Natta catalyst, metal oxides, or metallocenes.[ 85 ] To address sustainability concerns, efforts have shifted toward producing biobased polyethylene. Currently, biobased HDPE, accounting for 14% of the biobased bioplastic market, is primarily produced using sugarcane.[ 86 ] This process involves dehydrating bioethanol derived from glucose to synthesize ethylene monomers, which are then polymerized using the same methods as fossil‐derived ethylene. The resulting biopolymer is chemically and mechanically identical to petroleum‐based PE, including its compatibility with recycling processes. Thus, biobased PE serves as a compelling example of a sustainable alternative to traditional polymer production while maintaining the desired properties for PCM applications.[ 85 ]

In the quest to develop materials with extended melting ranges for cold chain applications, lactones with valuable biological properties show significant promise. Two prominent lactones, γ‐valerolactone and ε‐caprolactone, stand out due to their low melting points, −32 and −1.55 °C, respectively, with enthalpies of fusion in the range of 100–120 J g−1.[ 87 ] γ‐Valerolactone can be efficiently produced by catalytic hydrogenation of levulinic acid derived from cellulosic biomass, while ε‐caprolactone is typically synthesized on an industrial scale through the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation of cyclohexanone, where chemoenzymatic variations are possible.[ 88 ] Therefore, despite the natural occurrence of many lactones, we classified them as type 2 bio‐PCMs. Despite their advantages, both compounds face limitations, including susceptibility to supercooling, limited stability over repeated thermal cycles, and potential degradation at elevated temperatures around 90–100 °C. These challenges impact their viability and highlight the need for further optimization to enhance their durability and stability for practical applications.

Research into efficient and sustainable production methods, such as enzyme‐ or microbial‐based transformations, is vital for advancing bio‐PCMs. Although some sustainably developed derivatives currently have less competitive thermal properties than well‐established fossil fuel‐derived PCMs, they still offer valuable insights into understanding the link between chemical structure and thermal properties. For type‐2 materials, which involve extensive chemical modifications, it is essential to balance thermal performance, economic feasibility, and environmental impact.

2.4. Type 3 Bio‐PCMs

As type 3 PCMs, we classified eutectic mixtures, uniform blends of two or more components (binary, ternary, or multicomponent systems) that melt within a narrow temperature range (Table 4 ).[ 89 ] This melting range is lower than the T m of the individual components, making eutectic PCMs appropriate for creating materials with phase‐change temperatures that single‐component PCMs cannot achieve. The primary advantage of eutectic PCMs lies in their ease of preparation, as they can be simply created by combining different components, allowing for straightforward tuning of their melting temperature range, corrosivity, thermal conductivity, and stability.

Table 4.

| Type 3 bio‐PCMs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture of compound | T m [°C] | ΔH f [J g−1] | Mixture origin | References | |

| Biomass | Fossil fuelsa ) | ||||

| Lauric acid–myristic acid (0.85:0.15) | 40 | 173 | Fatty acids | – | [90, 250] |

| Myristic acid–stearic acid (0.50:0.50) | 35–52 | 189 | |||

| 1‐Dodecanol ‐ methyl stearate (0.10:0.90) | 22 | 202 | Fatty alcohol, fatty ester | – | [251] |

| 1‐Dodecanol ‐ methyl palmitate (0.30:0.70) | 20 | 224 | |||

| Paraffin‐stearic acid (0.45:0.55) | 56. | 192 | Fatty acid | Paraffin | [252] |

| Paraffin wax‐ oleic acid | 54 | 155 | Fatty acid | Paraffin | [94] |

| Galactitol‐mannitol (0.30:0.70) | 153 | 292 | Sugar alcohol | – | [96, 97, 253] |

| Xylitol‐erythritol (0.64:0.36) | 82 | 270 | Sugar alcohol | – | |

| Erythritol‐xylitoll‐dulcitol (0.31:0.68:0.01) | 81 | 268 | Sugar alcohol | – | [97] |

| Stearic acid ‐ n‐butyramide (0.55:0.45) | 64 | 198 | Fatty acid | Amide | [95] |

| Succinic acid‐boric acidb ) (0.56:0.44) | 150 | 394 | Succinic acid | – | [17] |

A compound derived from fossil fuels or produced through reaction with a fossil fuel‐based compound.

Boric acid is extracted from a variety of boron ores (colemanite, tincal, and ulexite) or naturally occurring boron brines.

Given the significant interest in using fatty acids as PCMs, it is unsurprising that much research focuses on developing their eutectic mixtures. PCMs with melting points in the low‐temperature range have been extensively studied for their application in construction materials aimed at thermal regulation in buildings.[ 90 ] Fatty acid phase transition temperatures are typically too high to effectively regulate indoor environments, and therefore their eutectic mixtures have been developed to adjust to give thermal comfort in buildings. Sari[ 90 ] successfully lowered the melting temperature of lauric acid and myristic acid (T m = 43 and 52 °C respectively) to 34.2 °C by forming their eutectic mixture with a weight ratio of 66:34. The mixture exhibited a latent heat of 167 J g−1, and after 1460 thermal cycles, its value varied by only 2.4%, demonstrating potential for practical use.[ 91 ] Gallart‐Sirvent et al. investigated direct preparation of PCMs from non‐edible fat waste through its hydrolysis followed by crystallization, yielding palmitic acid‐stearic acid mixtures.[ 92 ] Depending upon the solvent used for the crystallization, the crystallized fractions revealed melting and freezing temperatures around 55 and 52 °C, respectively, while the latent heat values ranged from 172 to 181 J g−1.

Beyond using fatty acid eutectic mixtures, combinations of their esters were explored. Saeed et al.[ 93 ] studied an eutectic mixture of methyl palmitate and lauric acid, which, at a molar ratio of 60/40, showed a high latent heat capacity (ΔH m = 205.4) and phase change temperature (T m = 25.6 °C) suitable for TES applications in buildings. The relatively low thermal conductivity of the mixture (0.1802 W m−1 K−1 in the solid state) could be enhanced by composite formation with carbon materials.

Recently, Chang et al. prepared eutectic mixtures of fatty acids (palmitic, stearic, and myristic acids) and paraffin wax with melting temperatures exceeding 55 °C and latent heat values up to 210 J g−1.[ 94 ] As demonstrated by these authors, such PCMs are suitable for thermal management in electronic devices. To further expand the melting temperature range, Guixiang Ma et al. developed mixtures of stearic acid with n‐butyramide (T m = 114 °C) and n‐octanamide (T m = 107 °C). The resulting PCMs melted at 64 and 62 °C, respectively, with latent heat values of 198 J g−1 and excellent thermal stability over 100 cycles.[ 95 ]

Addressing the gap in medium‐temperature PCMs (T m > 100 °C), Paul et al. investigated a PCM melting at 153 °C, prepared by mixing galactitol and mannitol at a molar ratio of 30:70.[ 96 ] Moreover, the addition of small quantities (up to 0.5 wt%) of nucleating agents, such as graphite powder or silver iodide, to the PCM (which had a high latent heat of 292 J g−1) minimized its supercooling, additionally improving the latent heat value to 300 J g−1. Remarkably, after 100 thermal cycles, the latent heat decreased by only 4%. Sugar alcohol mixtures reveal promise for applications where melting points <100 °C are needed, as demonstrated for mixtures of xylitol and erythritol (T m = 82 °C for 36 mol% erythritol) and mixtures of erythritol, xylitol, and dulcitol Ery(0.31)/Xyl(0.68)/Dul(0.01), T m = 81 °C.[ 97 ] However, the low stability under repetitive heating and cooling highlights the need for further research and modifications to enhance the performance of these bioderived systems.

A novel group of eutectic mixtures for intermediate TES was recently presented by Saher et al. with a record energy storage capacity of 394 J g−1.[ 17 ] The eutectic mixture of boric acid and succinic acid undergoes a transition at around 150 °C, synergistically storing thermal energy by combining latent, thermochemical, and sensible heat. This opens new research directions for inexpensive and sustainable eutectic mixtures.

3. Biomass‐Derived Carbonaceous Supports for Shape‐Stabilized Phase‐Change Materials (SSPCMs)

As mentioned previously, PCMs have several disadvantages when it comes to application development, including leakage during the solid‐liquid phase transition process and poor thermal conductivity. To overcome these limitations, sustainable strategies have been explored to engineer SSPCMs. Besides direct incorporation and macro/microencapsulation in biopolymer matrices (see Section 4), the impregnation of PCMs into preformed, biomass‐derived porous supports has been seen as a cost‐effective alternative.[ 98 , 99 ] This approach usually involves a support soaked in a molten PCM or a dilute aqueous solution of PCM, the liquid being put into the support by vacuum impregnation. The support must, therefore, be sufficiently porous to absorb and retain as much PCM as possible. Several studies proposed the use of wood, previously delignified, to increase porosity and permeability.[ 100 , 101 ] Because wood is widely used in the field of building materials, it looks like the ideal candidate. Besides, if forests are managed responsibly and wood is manufactured or recycled in an eco‐friendly way, this resource is potentially sustainable. However, delignified wood or other lignocellulosic resources still have drawbacks for direct use in SSPCMs, such as low thermal conductivity, limited chemical stability (which will depend closely on the PCM used), high hygroscopic character, and poor control over porosity.

In addition to organic materials, nature provides inorganic and hybrid resources with remarkable properties. For instance, an original study proposed the use of artificially cultured diatom frustules,[ 102 ] which come from biomass and display a hierarchical pore structure. However, diatom frustules are mainly composed of silica (80–90 wt%), which shows poor thermal conductivity and might adversely affect PCM performance. With this in mind, recent literature in the field has made it possible to draw up a set of specifications for defining appropriate support for SSPCMs. A suitable support should, therefore, be: 1) Renewable, sustainable, and low cost; 2) Highly porous, with an open pore network to allow high PCM loading and retention; 3) Chemically and thermally stable to ensure performance reliability over time; 4) Thermally conductive to sustain heat transfer and dissipation and improve TES efficiency; 5) Self‐standing and mechanically stable to make it easier to handle; 6) Sufficiently hydrophobic to avoid moisture adsorption/absorption; and optionally; 7) Electrically conductive if used in electrothermal PCM devices; 8) UV‐visible light absorber if used in photothermal PCM devices.

Among candidates that comply with all or most of these specifications, biomass‐derived carbonaceous supports present unique advantages.[ 103 ] Polyaromatic and/or graphenic carbon materials can be prepared from a large variety of renewable, abundant, and low‐cost organic resources, such as lignocellulosic material and its derivatives. They are thermally conductive and chemically stable and offer tunable textural and structural properties. For these reasons, several studies have suggested their use in SSPCMs (Table 5 ). For instance, G. Li et al. compared pristine poplar wood with the equivalent material pyrolyzed at 1000 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere.[ 104 ] When used as supports for 1‐tetradecanol (1‐TDO), these authors reported higher 1‐TDO mass loading (73.4 vs. 60.1 wt%), higher latent heat of fusion (165.8 vs. 138.7 J g−1), and higher thermal conductivity (0.414 vs. 0.155 W m−1 K−1 at 25 °C) for pyrolyzed wood compared with pristine wood. This study, among others, confirms the potential of biomass‐derived carbonaceous materials in SSPCMs. We have selected about thirty recent (post‐2018) articles on this topic, which are discussed in the following.

Table 5.

Summary of SSPCMs with biomass‐derived carbonaceous supports from articles published between 2018 and 2024.

| Bioresourcea ) | Thermal treatment | PCM | T m [°C] | Loading [wt%] | Melting enthalpy at 1st cycle [J g−1] | Melting enthalpy at n cycles | % retention | Thermal conductivity [W m−1 K−1] | increase [%] | Photothermal conversion efficiency [%] | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poplar wood | Washed in water | 1‐TDO | 37.2 | 60.1 | 138.7 | n/a | n/a | n/a | [104] |

| Poplar wood | 1000 °C (N2) | 1‐TDO | 37.2 | 73.4 | 165.8 | 200 | 84.4 | 0.52–0.66a | 115.8–173.9 | n/a | [104] |

| Cotton | MgO | 700 °C (Ar) | 1‐HDO | 51.4 | 85.0 | 204.4 | 200 | 98.0 | 0.37a | 5.7 | n/a | [111] |

| Cotton | MgO | 800 °C (Ar) | 1‐HDO | 51.4 | 90.0 | 219.4 | 200 | 95.4 | 0.40a | 14.3 | n/a | [111] |

| Cotton | MgO | 900 °C (Ar) | 1‐HDO | 51.4 | 88.0 | 215.5 | 200 | 90.6 | 0.41a | 17.1 | n/a | [111] |

| Succulent | 1000 °C (vacuum) | Paraffin | 40.8 | 62.8 | 83.6 | n/a | n/a | 82.0@300 mW cm−2 | [119] |

| Succulent | 1000 °C (vacuum) | Paraffin | 40.8 | 94.8 | 133.1 | n/a | 0.31a | 25.0 | n/a | [119] |

| Fresh potato | 1300 °C (N2) | PEG 4000 | 58.8 | 85.4 | 158.8 | n/a | 4.49b | 951.0 | n/a | [110] |

| White radish | 1300 °C (N2) | PEG 4000 | 58.8 | 89.8 | 159.7 | n/a | 1.75b | 309.8 | n/a | [110] |

| Sunflower straw | 400 °C | Stearic acid | 68.1 | 83.7 | 186.1 | n/a | 0.33c | 106.3 | n/a | [254] |

| Sycamore wood |

Delignified 500 °C (N2) |

Lauric acid | 42.8 | 81.1 | 177.9 | 100 | 98.8 | 0.270 d | n/a | n/a | [255] |

| Cotton |

1200 °C (Ar) Pressed at 16 mm |

Paraffin | 25.5 | 95.5 | 209.3 | n/a | 0.29c | 17.6 | n/a | [112] |

| Cotton |

2400 °C (Ar) Pressed at 10 mm |

Paraffin | 25.5 | 92.2 | 202.2 | n/a | 0.43c | 73.6 | n/a | [112] |

| Cotton |

2400 °C (Ar) Pressed at 16 mm |

Paraffin | 25.5 | 95.1 | 205.7 | n/a | 0.36c | 43.2 | n/a | [112] |

| Cotton | 900 °C (Ar) | Paraffin | 40.2 | 84.1 | 182.0 | n/a | 0.40e | 39.9 | 76.4@100 mW cm−2 | [120] |

| Sunflower stem | 1000 °C (Ar) | 1‐HDA | 44.0 | 95.2 | 271.0 | 50 | 99.7 | 0.38f | 157.8 | 67.8@100 mW cm−2 | [117] |

| Sunflower stem | 1000 °C (Ar) | Palmitic acid | 61.8 | n/a | 233.8 | 50 | 92.6 | 0.34f | 111.1 | n/a | [117] |

| Sunflower rec. | 1000 °C (Ar) | 1‐HDA | 44.0 | 89.7 | 239.4 | 50 | 99.7 | 0.37f | 153.7 | 75.6@100 mW cm−2 | [117] |

| Sisal fibers |

2400 °C (Ar) Density 0.097 g cm−3 |

Paraffin | 57.8 | 91.3 | 201.6 | 100 | 99.9 | 0.42–0.95f | 68–280 | n/a | [127] |

| Sisal fibers |

2400 °C (Ar) Density 0.172 g cm−3 |

Paraffin | 57.8 | 87.2 | 192.2 | 100 | 99.9 | 0.62–1.73f | 148–592 | n/a | [127] |

| Sucrose | NaHCO3 | 800 °C (N2) | Paraffin | 25.4 | 84.0 | 152.2 | 1000 | 100.5 | 0.33a | 22.2 |

31.0@200 mW cm−2 89.0@300 mW cm−2 |

[123] |

| Towel gourd | 900 °C (N2) | PEG 2000 | 58.9 | 94.5 | 164.3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | [129] |

| Watermelon | HTC 200 °C | Mannitol | 170.2 | 97.0 | 281.9 | n/a | 0.78 g | 20 | n/a | [118] |

| Watermelon | HTC 200 °C | Mannitol | 170.2 | 88.0 | 255.5 | n/a | 1.05 g | 61.5 | n/a | [118] |

| Gelatin | Fe(NO3)3 | 800 °C (N2) | Eicosane | 35.8 | 85.8 | 211.7 | 1000 | 96.6 | 0.52f | 13 |

60.6@200 mW cm−2 93.3@300 mW cm−2 |

[122] |

| Water chesnut |

HTC 130 °C AlO6P3 | 800 °C (N2) |

Octadecane | 29.7 | 85.0 | 216.2 | 100 | 99.0 | 1.47a | 673 | 96.1@100 mW cm−2 | [133] |

| Water chesnut |

HTC 130 °C AlO6P3 | 900 °C (N2) |

Octadecane | 29.7 | 80.0 | 192.3 | n/a | 1.52a | 700 | n/a | [133] |

| Balsa | Delignified | Paraffin | 41.5 | 85.1 | 199.9 | 30 | 86.5 | n/a | 60.0@100 mW cm−2 | [135] |

| Balsa | Delign. | 300 °C (N2) | Paraffin | 41.5 | 85.0 | 201.7–206.3 | 30 | 91.7–95.7 | 0.135–0.182h | n/a | 85.6–90@100 mW cm−2 | [135] |

| Corn straw | 400 °C (N2) | PEG | 56.8 | 36.8 | 105.4 | n/a | 0.190h | n/a | 49.3@100 mW cm−2 | [107] |

| Corn straw | 600 °C (N2) | PEG | 56.8 | 48.4 | 100.2 | 100 | 98.7 | 0.330h | 1.9 | 69.0@100 mW cm−2 | [107] |

| Corn straw | 800 °C (N2) | PEG | 56.8 | 42.6 | 77.2 | n/a | 0.429 h | 32.4 | 55.6@100 mW cm−2 | [107] |

| Pomelo peel | 900 °C (N2) | PEG 4000 | 61.3 | 95.4 | 162.4 | n/a | n/a | 84.0@200 mW cm−2 | [121] |

| Pomelo peel | Freeze‐dried | Paraffin | 59.5 | 88.0 | 125.7 | 25 | 100.7 | 0.218a | 6.3 | n/a | [106] |

| Pomelo peel | 650 °C (Ar) | Paraffin | 59.5 | 93.4 | 158.6 | 25 | 100.3 | 0.207a | 1.0 | 60.1@200 mW cm−2 | [106] |

| Pomelo peel | 750 °C (Ar) | Paraffin | 59.5 | 94.2 | 159.5 | 25 | 100.3 | 0.300a | 46.3 | 85.1@200 mW cm−2 | [106] |

| Pomelo peel | 850 °C (Ar) | Paraffin | 59.5 | 95.6 | 150.3 | 25 | 99.7 | 0.312a | 52.2 | 70.4@200 mW cm−2 | [106] |

| Bamboo | Dried | Paraffin | 28.9 | n/a | 99.8 | 100 | 98.8 | 0.28a | 17.3 | n/a | [256] |

| Bamboo | 600 °C (N2) | Paraffin | 28.9 | n/a | 79.4 | 100 | 101.0 | 0.42a | 72.4 | n/a | [256] |

| Bamboo | H3PO4 | 600 °C (N2) | Paraffin | 28.9 | n/a | 59.5 | 100 | 99.3 | 0.52a | 116.2 | n/a | [256] |

| Rice husk | K2CO3 | 700 °C (N2) | Stearic acid | 70.9 | 80.3 | 162.1 | n/a | 0.438i | 13.8 | n/a | [108] |

| Bamboo | K2CO3 | 700 °C (N2) | Stearic acid | 70.9 | 79.4 | 159.0 | n/a | 0.405i | 5.2 | n/a | [108] |

| Pine wood | K2CO3 | 700 °C (N2) | Stearic acid | 70.9 | 82.9 | 170.6 | n/a | 0.393i | 2.1 | n/a | [108] |

| Walnut shell | K2CO3 | 700 °C (N2) | Stearic acid | 70.9 | 78.5 | 168.9 | n/a | 0.418i | 8.6 | n/a | [108] |

| Corncob | K2CO3 | 700 °C (N2) | Stearic acid | 70.9 | 80.8 | 175.3 | n/a | 0.389i | 1.0 | n/a | [108] |

| Bamboo | Ca(OH)2 | 550 °C (Ar) | 1‐ODO | 59.0 | 70.0 | 197.0 | n/a | 0.71j | 184 | 75.2@300 mW cm−2 | [124] |

| Bamboo | Ca(OH)2 | 550 °C (Ar) | 1‐ODO | 59.0 | 80.0. | 284.1 | n/a | 0.57j | 128 | 66.4@300 mW cm−2 | [124] |

| Bamboo | Ca(OH)2 | 550 °C (Ar) | 1‐ODO | 59.0 | 85.0 | 299.8 | n/a | 0.45j | 80 | 57.3@300 mW cm−2 | [124] |

| Sunflower stem | 1000 °C (N2) | PEG 4000 | 62.5 | 84.0 | 153.4 | 50 | 99.6 | 0.43a | 51.9 | n/a | [125] |

| Sunflower rec. | 1000 °C (N2) | PEG 4000 | 62.5 | 91.6 | 171.5 | 50 | 99.4 | 0.41a | 44.9 | n/a | [125] |

| Loofah sponge | KOH | 800 °C | Octadecane | n/a | 60.4 | 155.1 | 100 | 99.2 | 0.208a | 27.7 | 95.2@100 mW cm−2 | [136] |

| Sorghum straw |

Delignified HTC 220 °C CQDs |

PEG 2000 | 53.1 | 94.5 | 168.1 | 100 | 93.8 | 0.374a | n/a | 90.8@1 W cm−2 | [109] |

All data is adopted from the literature; T m: melting point; Sunflower rec.: Sunflower receptacle; 1‐TDO: 1‐tetradecanol; 1‐HDO: 1‐hexadecanol; 1‐HAD: 1‐hexadecanamine; 1‐ODO: 1‐octadecanol. Methods and instruments used to measure thermal conductivities: atransient plane source method (TPS 2500S or 2500‐OT, Hot Disk instruments), bxenon flash method (XFA 500, LINSEIS), claser flash method (undefined), dlaser flash method (LFA 457, NETZSCH), etransient plane source method (TPS, DRE‐III tester, XIANGTANXIANGYI), fn/a, gtransient plane source method (HS‐DR‐5, HESON), hlaser flash method (LFA 467, NETZSCH); itransient plane source method (TCi, C‐Therm), jtransient plane source method (TPS 3500S, Hot Disk instruments).

3.1. Sustainability Considerations

If they come from a renewable, readily available, and inexpensive resource, which is not in competition with the food industry, carbonaceous supports can be considered sustainable. In the literature, several bioresources and agrowastes have been proposed as precursors to carbonaceous supports for SSPCMs, such as garlic peel,[ 105 ] pomelo peel,[ 106 ] corn straw,[ 107 ] rice husk, pine wood,[ 108 ] and sorghum straw.[ 109 ] Although the majority of these carbon precursors were agricultural or food waste with no significant added value, the question of their availability and sourcing was not addressed. Some precursors are even food resources, such as fresh potato and white radish,[ 110 ] or already have an existing market with added value, such as cotton.[ 111 , 112 ] Apart from being renewable and low cost, the production and storage of biomass‐derived carbons in buildings and structures has been proposed as a means of mitigating climate change;[ 113 ] indeed, they sequester carbon for a much longer period of time than would be the case if the original biomass were left to decay, following the example of biochars in soils.[ 114 ] Interestingly, the use of carbonaceous materials that do not come from bioresources but are part of a circular economy can also be a relevant option when it comes to sustainability. For instance, Z. Huang et al. proposed the use of graphite extracted from spent lithium‐ion batteries to prepare SSPCMs with excellent solar‐thermal and electric‐thermal conversion properties.[ 115 ]

Another important feature to take into account when dealing with biomass‐derived carbonaceous supports is the thermochemical process used to convert organic precursors into porous carbon‐rich materials. Whether pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere or chemical activation is applied, the authors rarely assess the impact of the chemical process through the prism of green chemistry precepts.[ 116 ] Carbonization yields are often very low (below 20 wt%), and chemical activation frequently involves harmful chemicals and generates a large amount of waste, leading to a high E‐factor. Nonetheless, sustainable alternatives are available. For instance, W. Ma et al. replaced KOH, a chemical activating agent that is highly corrosive, with potassium carbonate to prepare carbon‐based SSPCMs.[ 108 ] In general, lifecycle and techno‐economic analyses will have to be carried out to select the most sustainable resources and carbonization processes. Last, but not least, there are very few examples of SSPCMs with fully biomass‐derived constituent materials, that is, both carbon support and PCM;[ 108 , 117 ] however, fully biobased SSPCMs with phase change enthalpies of up to 234 and 282 J g−1 were reported for palmitic acid in sunflower‐derived carbon[ 117 ] and mannitol in watermelon‐derived carbon,[ 118 ] respectively. As a result, this review should open up many new avenues for future research studies.

3.2. Influence of the Porosity and Texture of the Carbon Support

High porosity, with an open pore network, is mandatory to allow high PCM loading and retention over time. Logically, the higher the porosity, the larger the PCM loading, and the higher the phase‐change enthalpy should be.[ 119 , 120 ] Recent articles reported PCM loading capacities superior to 95 wt%[ 106 , 112 , 117 , 118 , 121 ] and retention of the phase‐change enthalpy superior to 96% over 1000 cycles[ 122 , 123 ] for SSPCMs based on biomass‐derived carbonaceous supports. Coincidently, the larger the PCM loading, the lower the thermal conductivity of the SSPCM.[ 120 , 123 , 124 ] Controlling the structure, texture, and porosity of the carbon support should allow for a good compromise between those properties.

Although macropores (diameter >50 nm) are inherent to the selected biomass and can be modulated with difficulty (e.g., by delignification), micropores (<2 nm) and mesopores (between 2 and 50 nm) can be developed by a judicious choice and combination of thermochemical treatments and/or templates.[ 111 ] Biomass‐derived carbonaceous materials with various specific surface areas (up to 1640 m2 g−1[ 125 ]), pore size distributions, and pore volumes have been tested in SSPCMs. However, textural characterizations are often limited to volumetric gas adsorption and electron microscopy. Therefore, a global view of porosity, with a quantification of each contribution from macropores to ultramicropores (below 0.7 nm), is often lacking. Moreover, it is difficult, if not impossible, to study the influence of porosity independently of other parameters. Indeed, for the same biomass, controlling porosity is often associated with modifying the temperature of the thermochemical treatment and/or adding activating agents, which can considerably modify the surface chemistry and/or the structure of the carbonaceous framework.

Although the role of porosity and texture of the carbon support is difficult to assess, a few studies have attempted to tackle this important question. X. Li et al.[ 126 ] studied the phase change behavior of PEG 6000 impregnated into three different types of carbon materials: expanded graphite (EGr) bearing only macropores centered at 10 μm, an activated carbon (AC, obtained by physical steam activation of coconut shell) bearing mainly micropores, and an ordered mesoporous carbon (CMK‐5, obtained from sucrose as the carbon source) bearing both micro‐ and mesopores. The authors concluded that the macropores in EGr allowed a higher relative enthalpy efficiency and, consequently, a higher heat storage capacity to be maintained, whatever the mass loading of PEG (from 60 to 90 wt%) in the SSPCM. The melting enthalpy of EGr‐SSPCM, therefore, remained above 100 J g−1 even with 60 wt% of PEG. In this study, the authors also concluded that the macropores should be neither too wide, so that capillary forces are sufficiently high to retain the PCM in the composite, nor too narrow, so as not to affect the PCM crystallinity and heat storage capacity of the composite. Nevertheless, these results must be treated with caution. As shown by powder X‐ray diffraction, the structure of EGr is graphitic, while both AC and CMK‐5 display turbostratic structures. Besides, the surface chemistry of the carbon materials and their chemical interaction with the PCM were not thoroughly studied and discussed.

In addition to porosity, density is another parameter to be considered. In two different studies, N. Sheng et al. prepared carbon supports with adjustable density derived from cotton[ 112 ] and sisal fibers[ 127 ] to study the phase change behavior of paraffin. In both studies, the authors showed that, for the same specific surface area and micro‐mesopore volume, the SSPCMs with the densest carbon framework had the lowest paraffin mass loadings and the lowest phase change enthalpies (Table 5). In contrast, the densest supports had higher thermal conductivities and comparable relative enthalpy efficiencies. In these two studies, density was directly related to the volume of the interstices between the fibers and, therefore, to the volume of the largest pores, demonstrating the predominant influence of macropores on the properties of SSPCMs. At this point, it is important to note that, after thermal posttreatment, whether pyrolysis or activation, the porosity (micro‐ and mesopore volumes) generated in the carbonaceous framework significantly lowers both the envelope and bulk density of the material (since inaccessible narrow pores and closed pores are often produced). At constant volume, the PCM mass loading can, therefore, increase considerably without this effect being directly attributable to the interactions of the PCM with the micro‐ and mesopores themselves.[ 128 , 129 ]

It is also important not to overlook the effects of confinement in micro‐mesopores on phase transitions of PCMs that may result in significant shifts, especially when interfacial interactions with the pore walls are stronger than intermolecular interactions between the neighboring molecules confined in the pores.[ 130 , 131 ] For instance, G. Wang et al. showed that cotton‐derived porous carbons with specific surface areas between 490 and 880 m2 g−1 favorably lowered the extent of the supercooling phenomenon of pristine 1‐hexadecanol by 20.9–26.4%.[ 111 ] Q. Shi et al. reported a decrease in the supercooling extent of eicosane by ≈64.2% by confinement in a gelatin‐derived carbon (Figure 3 ) that displayed a specific surface area of 250 m2 g−1.[ 122 ] More recently, X. Liu et al. reported a decrease in the supercooling extent of PEG 6000 by ≈46.2% by confinement in sunflower‐derived highly porous carbons (>1000 m2 g−1).[ 125 ] In these examples, porosity seems to play a major role in the shift of the phase transition temperatures. Additionally, the molecular motion of PCM can be considerably hindered by confinement in narrow pores, therefore decreasing phase‐change enthalpy and heat storage capacity. A thorough study of the influence of porosity independently of other parameters would require model carbonaceous materials with a multiscale control over textural properties (e.g., pore size distribution, roughness, shape, hierarchy, and connectivity).

Figure 3.

a) Preparation method for gelatin‐derived carbon aerogel composite. b) Aerogel after freeze‐drying treatment before the carbonization process. c) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image after the carbonization process. d) Stability of the composite over 1000 cycles. Reproduced with permission.[ 122 ] Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry.

3.3. Surface Chemistry and Interfacial Interactions with the PCM

Interfacial interactions closely depend on the chemistry on the pore walls. Due to a PCM's confinement in narrow pores, the surface chemistry can have a major impact on its molecular motion. Nevertheless, in the context of SSPCMs, the surface chemistry of the carbon support and its interaction with PCMs have been little studied. On the one hand, strong interactions between the PCMs and pore walls would have a major impact on both the supercooling phenomenon (i.e., lower melting point and higher crystallization temperature) and the phase‐change enthalpy (decrease in heat storage capacity). On the other hand, it can be assumed that high‐temperature pyrolysis can promote hydrophobic carbon surfaces that may limit the ads‐/absorption of water molecules both on these surfaces and on the PCM. Interestingly, G. Li et al. demonstrated that delignified wood coated with a superhydrophobic surface prevented liquid leakage, brought self‐cleaning functionality to the composite, and significantly improved heat storage capacity in humid environments.[ 101 ] These authors reported a latent heat of fusion of 125.4 J g−1, which was 29.6 J g−1 higher than that of the phase change composite without the superhydrophobic coating. Such an approach remains to be demonstrated for biomass‐derived carbonaceous materials.

3.4. Shape Stabilization and Leakage Protection

Shape stabilization and leakage protection were systematically investigated (apart from a few exceptions) by observation with a digital camera above the melting point of PCM. In most cases, a slight liquid leakage was observed, which was attributed to the thermal expansion of the PCM during the melting process. Leakage measurements were, however, rarely performed over a period of more than 2 h,[ 110 , 118 , 119 , 123 , 129 ] and the mass losses of the PCM were rarely quantified. Furthermore, PCM leakage during heating‐cooling cycles was rarely, if ever, investigated. In two of the rare examples, PCM leakage of less than 3 wt% was observed after 100[ 125 ] and 200 thermal cycles[ 121 ] for PEG entrapped in sunflower‐ and pomelo peel‐derived porous carbons, respectively. Both parameters, that is, shape stabilization and leakage protection, should be investigated in more detail in order to comprehensively evaluate the potential integration of SSPCMs in TES systems.

3.5. Factors Affecting Thermal and Electrical Conductivity

As mentioned above, high thermal conductivity is mandatory to sustain heat transfer and dissipation and improve TES efficiency. We have already discussed two important and directly related parameters: the PCM loading and the density of the carbon support. On the one hand, as the PCM loading increases, the thermal conductivity of the SSPCM decreases.[ 120 , 123 , 124 ] On the other hand, SSPCMs with the densest carbon supports generally have higher thermal conductivities.[ 112 , 127 ] Two other important parameters can affect both thermal and electrical conductivities: the nanotexture (the dimensions of the crystallites and the presence of defects) and the structure (amorphous, turbostratic, partially graphitic, or graphitic) of the carbon support. Depending on the carbon precursor and on the thermochemical process used to convert it into a graphenic carbon‐rich material, these two parameters can be significantly affected. In general, as the pyrolysis temperature increases, defects and distortions within the graphene layer ensembles are healed. Coincidently, the structure evolves from amorphous to turbostratic and then from turbostratic to graphitic (beyond 2800 °C). Both phonons and electrons experience stronger scattering at lattice defects, chemical impurities, and grain boundaries. Thus, the higher the defect level, the shorter the mean free path of both phonons and electrons, and the lower the thermal and electrical conductivities.[ 132 ] Consequently, as the pyrolysis temperature increases, both the thermal and electrical conductivities should increase. This trend was confirmed in SSPCMs with carbon supports derived from cotton,[ 111 , 112 ] corn straw,[ 107 ] and waste pomelo peels.[ 106 ] However, it should be noted that it is difficult, if not impossible, to study the influence of one parameter independently of the others.

Interestingly, most studies using biomass‐derived carbon supports in SSPCMs demonstrated significant improvement in thermal conductivity compared to pristine PCMs (Table 5). For instance, Sheng et al. reported an improvement of 592% and a value of 1.73 W m−1 K−1 for sisal‐derived carbon fibers loaded with 87.2 wt% paraffin.[ 127 ] In another study, Zhao et al. showed an improvement of 700% and a value of 1.52 W m−1 K−1 for water chestnut‐derived carbons loaded with 80 wt% of octadecane.[ 133 ] The most significant improvement was reported by Y. Zhao et al. with potato‐derived carbon loaded with 85.4 wt% of PEG 4000. The authors showed a thermal conductivity of 4.49 W m−1 K−1, corresponding to 1050% of the value for the pristine PCM.[ 110 ]

Thermal conductivity can be further increased by adding inorganic fillers, which are not necessarily derived from biomass. For instance, Xie et al. demonstrated that the addition of silver nanoparticles in grapefruit peel‐derived porous carbon allowed a twofold increase in thermal conductivity compared to silver‐free SSPCMs and a threefold increase compared to the pristine PCM.[ 134 ]

3.6. Photothermal and Electrothermal Conversion Efficiency

When it comes to applications, an important feature is the ability of SSPCMs to convert either light or electricity into thermal energy. Photothermal and electrothermal conversion efficiencies are not only directly related to the thermal and electrical conductivities mentioned above but also to the UV‐visible light absorption capacity. While most PCMs show relatively low absorption of solar energy, polyaromatic and graphenic carbon materials display high UV‐visible light absorption capacity.[ 135 ] For instance, J. Ren et al. prepared carbon quantum dots (CQDs) by hydrothermal carbonization of lignin (extracted from sorghum straw) to put inside delignified sorghum straw along with PEG 2000.[ 109 ] It was possible to reach a photothermal conversion efficiency of 90.8% using a 750 nm laser with a constant intensity of 1 W cm−2. The phase transition temperature of PEG 2000 inside delignified sorghum straw without CQDs was not reached in similar photothermal experiments, demonstrating the importance of using carbonaceous supports with high light absorption capacity. Recent articles showed high photothermal conversion efficiencies of more than 75% under a light intensity of 100 mW cm−2, together with a high phase‐change enthalpy above 150 J g−1 (Table 5).[ 117 , 133 , 135 , 136 ] For instance, P.‐P. Zhao et al. reported a photothermal conversion efficiency of 96.1% (@100 mW cm−2) and a phase‐change enthalpy of 216.2 J g−1 with water chestnut‐derived carbons loaded with 85 wt% of octadecane.[ 133 ]

The electrothermal conversion ability of biomass‐derived carbonaceous supports for SSPCMs has been less frequently reported in the literature. In one of the rare examples, M. M. Umair et al. showed a high phase‐change enthalpy of 182.2 J g−1 together with high photothermal (76.4%@100 mW cm−2) and electrothermal conversion efficiencies for cotton‐derived carbon loaded with 84.1 wt% of paraffin (Figure 4 ).[ 120 ] This composite had a very high electrical conductivity of 19.6 S m−1, versus 10−14 S m−1 for pristine paraffin. The authors reported an electrothermal storage efficiency of 81.1% under 3 V, which was significantly better than the one of 71.4% under 15 V previously reported by Y. Li et al.[ 137 ] for melon‐derived carbon loaded with paraffin.

Figure 4.

a) Preparation method for cotton‐derived carbon composites. b) SEM image of the carbon scaffold. c) SEM image of the composite. d) Form stability and heat distribution performance of the composite. Reprinted with permission.[ 120 ] Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

In conclusion, the use of biomass‐derived carbonaceous materials in shape‐stabilized phase‐change composites looks very promising as these materials comply with all the specifications that define appropriate supports for SSPCMs. Biomass‐derived carbonaceous materials are renewable, low‐cost, chemically stable, and thermally and electrically conductive. Moreover, they display high UV‐visible light absorption capacity and offer tunable textural and structural properties. Consequently, these supports could give a large PCM loading (above 95 wt%), high phase‐change enthalpy (above 250 J g−1), and good retention of the phase‐change enthalpy over time (up to 100% over 1000 cycles; Table 5). Moreover, biomass‐derived carbonaceous supports allowed competitive photothermal and electrothermal conversion efficiencies of 96.1 (@100 mW cm−2)[ 133 ] and 81.1% (@3 V),[ 120 ] respectively, to be reached. However, most studies have focused on the performance of SSPCMs but provide little insight into understanding the interaction between the PCM and the carbonaceous support. It should be noted that it is difficult, if not impossible, to study the influence of one parameter independently of the others. When it comes to wood and raw lignocellulosic biomass, certain properties are difficult to control and modulate. For instance, macroporosity is inherent to the selected bioresource and might be significantly affected by seasonal variability. A thorough investigation of the influence of porosity, nanotexture, structure, and surface chemistry would require model materials where all these properties can be precisely controlled. The contribution of molecular dynamics simulation and machine learning could also be beneficial. Finally, yet importantly, lifecycle and techno‐economic analyses will have to be carried out to select the most sustainable resources and carbonization processes.

4. Purpose of Encapsulation of PCMs

The encapsulation of PCMs addresses key performance challenges in LHS systems. In particular, encapsulation serves as an effective approach to improve the thermal conductivity of PCMs by increasing the surface area available for heat transfer, thereby enhancing the overall performance of thermal storage applications.[ 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 ] In addition to improved thermal conductivity, encapsulation provides a robust barrier that protects PCMs from environmental factors, such as moisture and oxygen, which could otherwise lead to material degradation by corrosion or oxidation, leading to a loss of efficiency over time.[ 138 ]

Finally, encapsulation eliminates issues such as leakage, a significant concern during phase transitions when PCMs shift from a solid to a liquid. By containing the PCM within a stable shell, encapsulation prevents the material from escaping, therefore retaining its effectiveness and extending its operational life.[ 142 , 143 ]

The encapsulation process mimics nature's strategies, being similar to the protective structures found in cells and eggshells, with the PCM acting as the core material and the encapsulation material forming a surrounding shell.[ 29 , 30 ] This design concept allows for flexibility in the selection of encapsulating materials, enabling researchers to tailor the shell's properties to meet specific needs. Typically, shell materials fall into three primary categories: organic, inorganic, and hybrid materials. Organic shells, often polymer‐based, offer chemical compatibility with organic PCMs and can be designed to enhance flexibility and impact resistance. In contrast, inorganic shells may provide superior thermal stability and mechanical strength, suitable for PCMs used in higher‐temperature applications. Hybrid shells combine organic and inorganic materials to leverage the advantages of both, resulting in encapsulated PCMs with enhanced thermal conductivity, durability, and chemical compatibility. Selecting an appropriate shell material is crucial and hinges on factors such as interfacial properties and the intermolecular forces between the core PCM and shell. These properties influence the stability, strength, and thermal conductivity of the encapsulated PCM, which are key parameters for optimizing performance in specific applications. Importantly, the shell must not only encapsulate the PCM effectively but also withstand repeated thermal cycling, maintain structural integrity, and, ideally, enhance the thermal conductivity of the PCM system. Thus, encapsulation techniques not only safeguard PCMs from environmental degradation and leakage but also enable a customizable approach to improve thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, and overall compatibility with a variety of storage materials. This adaptability supports the development of LHS systems optimized for diverse applications, from medicine[ 144 ] to high‐temperature industrial uses.

The use of renewable, biodegradable materials, particularly biopolymers, offers a promising solution for creating eco‐friendly encapsulation systems that reduce the environmental impact associated with traditional, synthetic encapsulating materials.[ 33 , 145 ] Biopolymers, derived from natural sources, including agricultural waste and the food industry, can provide a renewable alternative that minimizes environmental pollution. Additionally, biopolymers are inherently biocompatible, making them suitable for applications in environmentally sensitive fields, such as food packaging,[ 146 ] textiles,[ 147 ] and medical devices.[ 148 ] By harnessing these renewable sources, researchers can develop encapsulation materials that not only enhance PCM performance through improved thermal stability and mechanical properties but also support sustainable development and circular economy principles, ensuring that advances in TES align with broader environmental sustainability goals.[ 149 , 150 ]

Encapsulation of PCMs can be categorized into three main types based on the scale of the encapsulated particles: nano‐, micro‐, and macroencapsulation.