Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Our study investigated the impact of various cardiovascular drug on the cardiac physiology of zebrafish embryos and validated these findings in mice.

BACKGROUND:

Cardiotoxicity has significantly contributed to the high drug attrition rate over the last two decades, underscoring the cardiac risk assessment in drug discovery and development. Although regulatory authority’s guidelines specified the cell-based assays for the safety assessment of drugs, the current requirements fall short due to a lack of in vivo biology. The use of zebrafish experimental system has surged in developmental and pathophysiological investigation due to their striking resemblance to mammals. Hence, we used the zebrafish model system for cardiovascular drug studies and validated it in the mice model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The zebrafish embryos of 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf) were exposed to different CVS drug and, recorded their heart rate, and further validated in mice.

RESULTS:

We observed that exposure to amlodipine (a calcium channel blocker), atenolol (a class II antiarrhythmic), and amiodarone (a class III antiarrhythmic) led to dose-dependent reductions in heart rate in zebrafish embryos, with effects varying based on drug concentration and mechanism of action. Specifically, amiodarone treatment resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in heart rate (0.001–100 μM) and atrioventricular block starting at a 10 μM concentration. Each class of cardiovascular drug demonstrated unique cardiac effects in zebrafish embryos, reflecting similar patterns in mice treated with these drugs.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings highlight the zebrafish model’s utility for early-phase cardiac risk assessment in drug discovery due to its high throughput capabilities and other beneficial features.

Keywords: Atrioventricular block, cardiotoxicity, drug attrition, heart rate, high throughput screening, QT prolongation, zebrafish

Introduction

Drug discovery and development have stalled due to many issues and challenges, particularly regarding the toxicity of newly developed drugs during the postmarketing phase. The failure of a new chemical entity during this phase represents a significant setback for the pharmaceutical industry in terms of both financial investment and time expended. Only around 10% of molecules progress to clinical trials.[1,2]

During clinical trials, drug attrition primarily occurs due to insufficient efficacy, whereas withdrawal of drugs after postmarketing is typically linked to toxicity.[2,3] Common drug-induced toxicities affecting vital organs such as the liver, heart, and central nervous system are prevalent in humans.[4,5] Approximately 20% of drug attrition is attributed to toxicity affecting vital organs, with cardiac toxicity standing out as a significant contributor to this attrition rate on its own.[1]

The proarrhythmia in patients with cardiac disease is linked with the blockade of the human ether a-go-go related gene (hERG) and prolongation of the QT that is induced with drug administration.[6] A more robust, efficient, cost-effective, reliable, and innovative preclinical screening system predicting compound toxicity in the early phase of the preclinical study and ensuring the drug safety profile with voluminous screening capacity before advancing the clinical phases is the need of the pharmaceutical industry involved in drug discovery venture. The cell-based assays are commonly used as a high throughput screening method, but it does not mimic in vivo biology.

The zebrafish experimental system had been explored for pharmacological investigation owing to its various advantages over cell-based assays. The zebrafish cardiovascular system (CVS) is similar to the mammalian CVS in terms of rhythm, heart rate, and conduction. The regulatory and genetic signaling network in the zebrafish heart is quite similar to higher vertebrates.[7,8] The zebrafish heart consists of a single atrium and a single ventricle. The deoxygenated blood flows via sinus venous from atrium to the ventricle, and then blood goes to gills for oxygenation through the bulbus arteriosus and finally to the ventral aorta. 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf), the zebrafish heart starts contracting. The progenitor cells namely atrial cardiomyocytes (CMs), ventricular CMs, and endocardial cells present at the lateral margin, start migrating bilaterally to the anterior lateral mesoderm plate by 15 hpf.[9] These progenitor cells fuse with developing endocardium cells to form a cardiac disk, leading to the formation of the two-chamber heart.[10] Moreover, the zebrafish heart expresses the orthologous hERG gene that controls rhythm and heart rate, similar to mammals.[11]

An attractive feature of zebrafish assays for pharmacological investigation is the potential to use them for high throughput screening because of their small size, transparency, and high fecundity.[12] Other advantages include a short developmental window, the possibility for genetic manipulation and ease of imaging due to transparency, and functionally developed organs by 96 hpf, which make the zebrafish-based screening method a potential tool in lead identification, validation, safety, and toxicity studies.[13]

The maintenance of the zebrafish model is cost-effective as compared to rodents. A high degree of conservation exists between the human and zebrafish genomes (approximately 75% similarity).[14] Additionally, the zebrafish experimental system would serve as an early-stage screening tool to shortlist the potential leads that will proceed for preclinical testing in rodents, thus reinforcing the “3 R” concept (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement).

In the present study, three cardiovascular drugs from different classes were tested in zebrafish and mice, revealing varying cardiovascular effects. Amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker, and atenolol, a beta-blocker, both significantly reduced heart rate without affecting the QT interval. Amiodarone caused dose-dependent reductions in heart rate and atrioventricular (AV) block. These findings underscore the zebrafish model’s efficacy in linking cardiac changes to drug treatments, aiding cardiovascular drug discovery and development.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Zebrafish embryos were obtained by mating adult fish as per the standard method.[15] The experiments were performed on 72 hpf zebrafish larvae. Adult wild-type mice (Swiss albino strain; 8–10 weeks old male mice) were received from Panacea Biotech, Mumbai. The total number of mice used was 30, six animals per group.

The Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) under the purview of the Committee for the Control and Supervision of Experiments on the Animals (CCSEA; former CPCSEA) guidelines, ARRIVE guidelines, and the Basel Declaration guidelines were followed for all animal experiments and accordingly, animals were handled. The protocol of the animal experiment was approved with approval number IAEC119-17/2017 from Control and Supervision of Experiments on the Animals (CCSEA; former CPCSEA).[16]

Housing and husbandry

Animals were housed according to CCSEA guidelines, with a temperature of 21°C–23°C and humidity at 40%–60%. They were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to commercial feed and water. After acquisition, animals underwent 15 days of quarantine for acclimatization before experimentation.

System maintenance for zebrafish

Zebrafish were kept in water having conductivity between 300 and 1500 μS. The water temperature was generally maintained between 28.5°C ± 1°C, and the lighting conditions were 14:10 h (light: dark). The pH of the system water was checked daily and maintained between 6.8 and 7.5. When necessary, sodium bicarbonate was used to increase the pH of water. Since we used a static system for maintaining the fish, we changed the water every alternate days by monitoring all above parameters and clean tanks every alternate days.[15,17]

Feeding

Adult zebrafish were fed with dry food (dry flakes from Ocean Nutrition, India) (food size varies with the age of zebrafish; for example, 100 μm for larvae and 300–400 μm for adult fish) and live food (brine shrimps – in-house hatched).

Breeding

Fertilized zebrafish eggs were obtained by pairing one male and one female in a breeding tank. After removing the partition, mating occurred in 20 minutes, and eggs were then collected and washed. The embryos were washed with E3 media. The composition of E3 contains NaCl, 13.7 mM; KCl, 0.54 mM; MgSO4, 1.0 mM; CaCl2, 1.3 mM; Na2HPO4, 0.025 mM; KH2PO4, 0.044 mM; NaHCO3, 4.2 mM. Embryos were sorted under a microscope looking for unfertilized eggs, and fertilized healthy eggs were separated for further experiments.

Cardiotoxicity assessment

Zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf, when they were out from their chorion, were placed in 35 mm dishes with 3 ml embryo medium. For the study, embryos were exposed to tetracycline (TC), atenelol (AT), amiodarone (AD), and amlodipine (AP) in varying concentrations, dissolved in either 0.5% DMSO or water, depending on drug solubility. Twenty-four embryos per concentration were used, with four replicates of six embryos each. After 4 h of drug exposure, embryos were embedded in methylcellulose and imaged under a 10X objective lens. Videos were recorded at 100x magnification, analyzed for heart edema, blood flow, and other defects, and heartbeats counted using VLC media player.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of the drug and selection of dose for cardiophysiology assessment in mice

The mouse dose (mg/kg) was determined using data from zebrafish embryo heart rate experiments, along with information on the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile [Supplementary Table 1]. This approach helped identify a dose that would result in a peak plasma concentration (Cmax) at the time of maximum concentration (Tmax), which corresponds to the toxic range observed in the zebrafish model. The goal was to match the plasma concentration in mice to the levels seen in zebrafish that caused toxicity, ensuring that the effects would be similar between the two species.

Supplementary Table 1.

Summary of pharmacokinetic profile of drugs used in the study

| Drug | Pharmacology/MOA | Peak plasma concentration (Cmax) | Time to peak concentration (tmax) (h) | Half life (t1/2) | LD50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (antibiotic) | Bacteriostatic inhibit protein synthesis by binding to 30S ribosomes | 2–5 µg/mL | 2–4 | 6–11 (h) | 808 mg/kg (oral; mice) |

| AP (anti angina) | Blocks the calcium ion influx across the cell membrane with selectivity | 6 ng/mL | 6–8 | 30–50 (h) | 37 mg/kg (oral; mice) |

| AT (anti-hypertensive and anti angina) | Class II antiarrhythmatic drugs; β1 cardioselective antagonist. β1 adreenergic receptors antagonist | 1–2 µg/mL | 2–4 | 6–7 (h) | 2 g/kg (oral; mice) |

| AD (anti arrhythmic) | Class-III anti-arrhythmetic drug. Prolongs APD and Q-T interval attributable to block rectifier K + channels. Inhibit myocardial Ca channels noncompetitive B adrenergic receptor blocker | 0.5–2.5 µg/mL | 1–2 | 3–8 weeks | 178 mg/kg (intravenous; mice) |

MOA=Mechanism of action, APD=Action potential duration, TC=Tetracycline, AP=Amlodipine, AT=Atenolol, AD=Amiodarone

For example, AT was administered to mice at a dose of 150 mg/kg of body weight to achieve a peak plasma concentration of approximately 10 μM [Supplementary Table 1 and Table 1]. This dosage was based on findings that AT, in the 1–100 μM range, reduced heart rate in zebrafish. The median dose of 10 μM was selected, and the corresponding oral dose for mice was calculated accordingly [Supplementary Table 1 and Table 1].

Table 1.

Dose selection for electrocardiogram recording in mice

| Drugs | Concentration range (µm) showing effect on heart rate | Effect on zebrafish heart rate | Molecular weight | Volume of distribution (mL/kg) | Dose (mg/kg) used for mice for oral route administration | Plasma drug concentration (µg/mL) | Plasma drug concentration (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | 1000 | No effect | 444 | 45,000 | 500 | 11 | 25 |

| AP | 0.1–1 | Decrease in heart rate | 408 | 21,000 | 9 | 0.429 | 1 |

| AT | 1–100 | Decrease in heart rate | 266 | 52,000 | 150 | 2.88 | 11 |

| AD | 0.001–100 | Decrease in heart rate | 645 | 66,000 | 50 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

Plasma drug concentration (µg/mL)=Dose (µg/kg)/volume of distribution (mL/kg). TC=Tetracycline, AP=Amlodipine, AT=Atenolol, AD=Amiodarone

Electrocardiogram recording in mice

The recording and analysis of mice electrocardiogram (ECG) were done using a digital acquisition and analysis system (PowerLab 8/30 series; model number ML870 (830-2855) (AD Instruments, Australia). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (30–60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10–20 mg/kg) and placed on heating pad in the supine position for ECG recording. The body temperature of the animals was monitored using a rectal probe and maintained at 37°C–38°C. The lead II ECG was recorded from needle electrodes inserted subcutaneously into the right forelimb and each hind limb. The signal was acquired for about 1 min using lab chart 4.2.3 software. When ECG recording was finished, the rectal temperature probe and limb electrodes were removed. The mouse was allowed to wake up and was then returned to its cage. The depth of anesthesia was monitored from respiration rates and limb reflexes induced by paw and tail pinches applied periodically. The dose of each drug for mice was selected based on the observed effect on zebrafish heart and pharmacokinetic profile of the drug, as shown in Table 2. Six animals per dose per drug were used for ECG recordings. The ECG was recorded when peak plasma concentration (Cmax) reached its maximum therapeutic level (Tmax).[18,19,20,21]

Table 2.

Heart rate and QT intervals in mice treated with different drugs at Tmax

| Drugs | Heart rate (beats per minute), Mean ± SD | QT interval (ms), Mean ± SD | QTc (ms), Mean ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | |

| TC | 334.5±26.79 | 331.1±6.5 | 44.4±5.7 | 41.1±0.1 | 106.3±5.2 | 96.87±0.2 |

| AP | 349.9±47.39 | 322.6±25.7 | 42.69±5 | 42.09±5.8 | 101.2±12.6 | 99.75±15.1 |

| AT | 343.9±30.24 | 239.5±50.1 | 52.86±7.3 | 53.29±5.3 | 123.1±20.3 | 104.4±4.3 |

| AD | 323.4±41.6 | 232.1±25.3 | 37.3±7.4 | 42.96±11.4 | 85.1±16.2 | 104.3±15.7 |

SD=Standard deviation, TC=Tetracycline, AP=Amlodipine, AT=Atenolol, AD=Amiodarone

Statistical analysis

The two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis for more than two groups. The results are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). The GraphPad Prism statistical program (GraphPad Prism version 7.04 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for analysis. The p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data also presented as a bar chart with error bars depicting SD.

Results

Assessment of mortality wave in the facility

We performed the viability count of zebrafish embryos from 0 h to 24 hpf to assess the mortality rate of zebrafish embryos in our facility and repeated the experiment 6 times. We found that ~ 90% of embryos were viable, as shown in Supplementary Figure 1 (59KB, tif) . Our results are in line with reported data for mortality rate that ranges from 5% to 30%.[22] We also observed that embryos hatched and came out of chorion after 48 hpf. Therefore, we performed the cardiotoxicity studies after 72 hpf to avoid mortality and dechorionation effect (mechanical or enzyme induced).

Viability of zebrafish embryos after drug exposure

Zebrafish embryos were incubated for 4h in different concentrations of drugs viz. 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 and 1000 μM.

The zebrafish embryos (72 hpf) incubated with TC, AT, amlodpine, and AD were viable up to a concentration of 100 μM except for TC, as shown in Supplementary Figure 2 (191.8KB, tif) .

The zebrafish embryos incubated with 1000 μM of TC concentration were viable without any sign of morbidity, whereas treatment with amlodipine at 10, 100, and 1000 μM concentration led to the death of zebrafish embryos. The embryos exposed to AT and AD at 1000 μM concentration did not survive.

Heart rate assessment in zebrafish embryos

Zebrafish embryos exposed to various concentrations of TC showed no change in heart rate or the atrial:ventricular ratio [Figure 1a]. As depicted in Figure 2A (a) and (b), zebrafish embryos from the control group and those exposed to 1000 µM TC showed an absence of toxic effects.

Figure 1.

Assessment of heart rate in zebrafish embryos. The zebrafish embryos were treated with (a) Tetracycline (b) Amlodipine (c) Atenolol, and (d) Amiodarone (*p < 0.05 significant vs. control; n = 20) (BPM = Beats per minute)

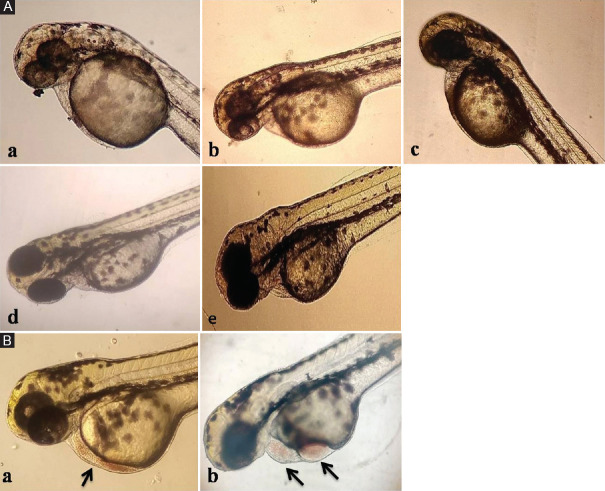

Figure 2.

Morphological changes of the heart exposed to various cardiovascular drugs (A) Heart of zebrafish exposed to (a) Control (b) tetracycline at 1000 μM (c) Atenolol at 100 (d) Amlodipine at 0.1 μM (e) Amiodarone at 1 μM showed no abnormalities (B) Zebra fish embryos showed accumulation of red blood cells (RBC) with (a) Amlodipine 1 μM (b) Amiodarone 100 μM (arrow indicates accumulation of RBC)

Figure 4.

Estimation of QT prolongation in mice treated with different cardiovascular drugs. The mice treated with tetracycline, amlodipine, atenolol and amiodarone at different doses and their QT interval (ms) and corrected QT interval (QTc) (ms) were recorded. (*p < 0.05 significant vs. control; n = 6)

Amlodipine exposure at 0.1 and 1 μM reduced heart rate [Figure 1b]. Concentrations of 10 μM and higher were lethal. At 1 μM, amlodipine caused blood cell accumulation due to slow blood flow, but no severe abnormalities were seen in the heart morphology, as shown in Figure 2A (d) and B (a).

AT treatment up to 1 μM had no effect on heart rate or the atrial:ventricular ratio [Figure 1c]. However, at 10 and 100 μM, AT significantly decreased heart rate in a dose-dependent manner without altering the atrial:ventricular ratio. No organ-specific toxicity or defects in heart or blood flow were observed at the highest AT concentration [Figure 2A (c)].

AD treatment caused a significant, dose-dependent reduction in heart rate, as illustrated in Figure 1d. The atrial:ventricular ratio remained unchanged at concentrations up to 1 μM of AD; however, at concentrations of 10 and 100 μM, a significant change in the atrial:ventricular ratio was observed.

The heart rate per minute for the ventricle reduced significantly compared to the atrium at both dose levels. There was a slight structural distortion of the atrium and ventricle with a change in rhythm. The slowing down of the heart led to the accumulation of RBC at higher concentrations with AD treatment, as shown in Figure 2A (e) and B (b).

Heart rate and electrocardiogram parameter assessment in mice

The mouse dosage (mg/kg) was derived based on zebrafish embryo heart rate data and drug pharmacokinetics [Supplementary Table 1]. This dosage was selected to ensure that the peak plasma concentration (Cmax) at Tmax matched the toxic range observed in zebrafish. TC treatment did not exhibit cardiotoxicity at any tested concentration in zebrafish hearts, leading to the choice of a 500 mg/kg dose to achieve a plasma concentration of 25 μM. No alterations in heart rate or QT interval were observed [Figure 3a and Table 2]. Although the QT and corrected QT interval (QTc) slightly decreased at Tmax, this reduction was not statistically significant [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Estimation of heart rate in mice treated with different cardiovascular drugs. The mice treated with (a) tetracycline (b) Amlodipine (c) Atenolol and (d) Amiodarone at different doses and their heart rate were recorded. (*p< 0.05 significant vs. control; n = 6) (BPM = Beats per minute)

As summarized in Table 1, a decrease in zebrafish heart rate was observed with amlodipine treatment in the range of 0.1–1 μM. To achieve a peak plasma concentration (Cmax) of 1 μM at Tmax, a dose of 9 mg/kg amlodipine was calculated based on pharmacokinetic profile of the drug and administered to the mice.

ECG recordings of amlodipine-treated mice showed a decrease in heart rate at peak plasma concentration (Tmax) and 24 h after treatment. The reduction in heart rate was significant at 24 h after treatment in comparison to Tmax [Figure 3b]. The QT intervals (QT and QTc) slightly increased after 24 h treatment; however it was statistically nonsignificant, as depicted in Figure 4 and Table 2.

AT was administered to mice at a dose of 150 mg/kg to achieve ~ 10 μM peak plasma concentration, as the treatment with AT in the range of 1–100 μM decreased the zebrafish heart rate. Mice treated with AT exhibited an attenuated heart rate at peak plasma concentration and 24h post-treatment, as delineated in Figure 3c and Table 2. The QT and corrected QT interval (QTc) were found to be low as compared to before treatment values, but they were statistically non-significant [Figure 4].

Since AD treatment at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 100 μM significantly reduced heart rate in zebrafish [Figure 1d], a dose of 50 mg/kg was chosen for mice to achieve a peak plasma concentration of 1 μM, the median value within this dose range. Mice treated with AD exhibited a significant reduction in heart rate [Figure 3d] and QT prolongation both at Tmax and 24 h post-treatment, with the effect being statistically significant at 24h [Figure 4].

Discussion

Zebrafish, an in vivo whole-organism model, is ideal for accelerating drug screening. In this study, we assessed drug-induced cardiotoxicity in zebrafish using a range of cardiovascular drugs. The results from zebrafish were further analyzed in mice for correlation. Cardiotoxicity is a major factor contributing to drug attrition during development, with drug-induced hERG blockade and QT interval prolongation posing risks of pro-arrhythmic events in cardiac patients. Zebrafish in vivo cardiotoxicity assays provide valuable insights that complement traditional cell-based assays.

TC was reported to be a non-cardiotoxic drug in humans, and therefore, we included it as the negative control in the present study. In line with the reported data, we did not find any cardiotoxicity in zebrafish embryos as well as in mice with TC treatment at the tested concentration.

Amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker belonging to the dihydropyridine class of compounds, block the influx of calcium ions through L-type calcium channels of blood vessels and acts as a vasodilator. In addition, amlodipine blocks L-type calcium channels of CMs at a therapeutic level. It is clinically used as an antihypertensive drug, and the therapeutic efficacy normally achieved with the 5–6 ng/mL (14 nM) of peak plasma concentration.

The embryos exposed to 10, 100, and 1000 μM concentrations of amlodipine showed lethality within 30 min of treatment. The lethal dose of amlodipine is 37 mg/kg in rodents which defines its potency. With a dose of 37 mg/kg (LD50 of amlodipine), the peak plasma concentration of 1500–2100 ng/mL (4–5 μM) is achieved. The peak plasma concentration of 1500–2100 ng/mL (4–5 μM) is 250 times higher than the therapeutic plasma concentration, and this could explain the observed lethality at 10, 100, and 1000 μM concentrations of amlodipine used for zebrafish embryos assay.

In mice, amlodipine treatment resulted in a statistically significant reduction in heart rate 24 h after drug administration. This effect may be attributed to the drug’s long half-life. The QT interval remained unchanged following amlodipine treatment at a 1 μM concentration (approximately 70 times higher than Cmax), which is consistent with the drug’s nonarrhythmogenic properties.

A recent study by Higa et al.[23] analyzed the arrhythmogenic potential of drugs using human-induced pluripotent stem cells. The result of this study showed that the CMs exposed to amlodipine (at 10 and 1 μM concentrations) arrested the beating of cells with cell shrinkage even though amlodipine is the non-arrhythmogenic drug.

They reported that arrhythmogenic risk could be increased if the blood concentration of the drug is 100 times higher than its therapeutic plasma concentration based on the gene expression studies. Intrinsically, calcium channel blockers depress myocardial contractility, and they are vasodilators having a negative ionotropic effect. Clinical trials with amlodipine reported that patients treated with amlodipine showed pulmonary and peripheral edema without any effect on the mortality rate due to its direct effect on the vasculature.[24,25]

AT is a beta-blocker and selectively binds to the beta1 receptors present in cardiac tissue. The AT has long been used clinically as an antihypertensive drug as well as a reference drug in most of the clinical trials. The treatment with AT significantly decreased heart rate without altering atrial:ventricular ratio and QT interval in zebrafish and mice. The meta-analysis study carried out by Carlberg et al. showed a significantly higher mortality rate, especially stroke, with the use of AT.[26] On a similar line, another group showed that hydrophilic beta-blockers such as AT showed pronounced mortality, as compared to lipophilic beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol).[27] The higher mortality rate with AT treatment needs to be investigated further at the gene expression level to decipher the underlying mechanism of toxicity.

AD is a class III antiarrhythmic and anti-angina drug. It prolongs phase 3 action potential and has numerous cardiac effects by inhibiting voltage-gated sodium channels, calcium channels, human ether-a- go-go related gene (hERG) channels, and noncompetitive alpha and beta-adrenergic receptors.

The zebrafish embryos exposed to the various concentrations of AD showed a statistically significant decrease in heartbeats in a dose-dependent manner compared to control groups. The zebrafish embryos treated with AD at 1 μM or >1 μM concentration showed AV block, that is, heartbeats per minute for ventricles reduced significantly compared to the atrium. The AD-treated mice showed similar results with a decrease in heart rate and QT prolongation.

AD is reported to cause Torsades de Pointes, sinus tachycardia, and worsen the preexisting arrhythmia.[28,29] The AD-treated CMs derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells showed a decrease in the beating frequency without morphological changes.[23] In our study with zebrafish and mice model, we observed a decrease in heart rate with QT prolongation upon AD treatment.

A study conducted by Clements et al. demonstrated the structural and functional cardiotoxic effects of AD on CMs derived from human embryonic stem cells.[30] Using the multielectrode array technique (an in vitro electrophysiological method comparable to an in vivo ECG), they observed a significant increase in beating frequency with AD treatment at concentrations above 10 μM. In addition, higher concentrations (10 μM) led to a loss of cell viability due to mitochondrial damage. In contrast, our findings showed a decrease in heart rate, along with AV block or QT prolongation, in zebrafish and mice treated with AD.

Conclusions

Our findings support the use of zebrafish as a screening model for cardiovascular drugs in preclinical research. Drug effects in this model are influenced by several factors, including the class of compounds, mechanisms of action, physicochemical properties, and pharmacokinetic profiles, with these effects being reflected in the zebrafish model. A limitation of this study is the lack of analysis of cardio-specific gene or protein expression. While traditional cell-based assays primarily focus on functional studies without replicating in vivo biology, the zebrafish screening model offers a more relevant, cost-effective, high-throughput, and predictive alternative. As an in vivo whole-organism model, it provides a valuable platform for predicting drug safety in preclinical settings, complementing conventional assays for evaluating drug safety, efficacy, and toxicity.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Viability count for zebrafish embryos for assessing mortality wave in the facility

Viability of zebra fish embryos exposed to different concentrations of drugs

Funding Statement

Nil.

References

- 1.Ferri N, Siegl P, Corsini A, Herrmann J, Lerman A, Benghozi R. Drug attrition during pre-clinical and clinical development: Understanding and managing drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138:470–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:40–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook D, Brown D, Alexander R, March R, Morgan P, Satterthwaite G, et al. Lessons learned from the fate of AstraZeneca's drug pipeline: A five-dimensional framework. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:419–31. doi: 10.1038/nrd4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomme EA, Will Y. Toxicology strategies for drug discovery: Present and future. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29:473–504. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster WR, Chen SJ, He A, Truong A, Bhaskaran V, Nelson DM, et al. Aretrospective analysis of toxicogenomics in the safety assessment of drug candidates. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:621–35. doi: 10.1080/01926230701419063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rampe D, Brown AM. A history of the role of the hERG channel in cardiac risk assessment. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2013;68:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnaout R, Ferrer T, Huisken J, Spitzer K, Stainier DY, Tristani-Firouzi M, et al. Zebrafish model for human long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11316–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedmera D, Reckova M, deAlmeida A, Sedmerova M, Biermann M, Volejnik J, et al. Functional and morphological evidence for a ventricular conduction system in zebrafish and Xenopus hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1152–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00870.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stainier DY, Lee RK, Fishman MC. Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. I. Myocardial fate map and heart tube formation. Development. 1993;119:31–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown DR, Samsa LA, Qian L, Liu J. Advances in the study of heart development and disease using zebrafish. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2016;3:13. doi: 10.3390/jcdd3020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langheinrich U, Vacun G, Wagner T. Zebrafish embryos express an orthologue of HERG and are sensitive toward a range of QT-prolonging drugs inducing severe arrhythmia. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;193:370–82. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barros TP, Alderton WK, Reynolds HM, Roach AG, Berghmans S. Zebrafish: An emerging technology for in vivo pharmacological assessment to identify potential safety liabilities in early drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1400–13. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornet C, Calzolari S, Miñana-Prieto R, Dyballa S, van Doornmalen E, Rutjes H, et al. ZeGlobalTox: An innovative approach to address organ drug toxicity using zebrafish. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:864. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013;496:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avdesh A, Chen M, Martin-Iverson MT, Mondal A, Ong D, Rainey-Smith S, et al. Regular care and maintenance of a zebrafish (Danio rerio) laboratory: An introduction. J Vis Exp. 2012;69:e4196. doi: 10.3791/4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: The ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence C. The husbandry of zebrafish (Danio rerio): A review. Aquaculture. 2007;269:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agwuh KN, MacGowan A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the tetracyclines including glycylcyclines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:256–65. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirch W, Görg KG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atenolol – A review. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1982;7:81–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03188723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latini R, Tognoni G, Kates RE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amiodarone. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1984;9:136–56. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198409020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meredith PA, Elliott HL. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amlodipine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;22:22–31. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199222010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraysse B, Mons R, Garric J. Development of a zebrafish 4-day embryo-larval bioassay to assess toxicity of chemicals. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2006;63:253–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higa A, Hoshi H, Yanagisawa Y, Ito E, Morisawa G, Imai JI, et al. Evaluation system for arrhythmogenic potential of drugs using human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and gene expression analysis. J Toxicol Sci. 2017;42:755–61. doi: 10.2131/jts.42.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohn JN, Ziesche S, Smith R, Anand I, Dunkman WB, Loeb H, et al. Effect of the calcium antagonist felodipine as supplementary vasodilator therapy in patients with chronic heart failure treated with enalapril: V-HeFT III. Vasodilator-heart failure trial (V-HeFT) study group. Circulation. 1997;96:856–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packer M, O’Connor CM, Ghali JK, Pressler ML, Carson PE, Belkin RN, et al. Effect of amlodipine on morbidity and mortality in severe chronic heart failure. Prospective randomized amlodipine survival evaluation study group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1107–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH. Atenolol in hypertension: Is it a wise choice? Lancet. 2004;364:1684–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Sun N, Jiang X, Xi Y. Comparative efficacy of ?-blockers on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with hypertension: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kálai T, Várbiró G, Bognár Z, Pálfi A, Hantó K, Bognár B, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of the permeability transition inhibitory characteristics of paramagnetic and diamagnetic amiodarone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:2629–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer J, Obejero-Paz CA, Myatt G, Kuryshev YA, Bruening-Wright A, Verducci JS, et al. MICE models: Superior to the HERG model in predicting torsade de pointes. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2100. doi: 10.1038/srep02100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clements M, Millar V, Williams AS, Kalinka S. Bridging functional and structural cardiotoxicity assays using human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for a more comprehensive risk assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2015;148:241–60. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Viability count for zebrafish embryos for assessing mortality wave in the facility

Viability of zebra fish embryos exposed to different concentrations of drugs