Abstract

Psychiatric disorders are highly heritable and polygenic, influenced by environmental factors, and often comorbid. Large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) through consortia efforts have identified genetic risk loci and revealed the underlying biology of psychiatric disorders and traits. However, over 85% of psychiatric GWAS participants are of European ancestry, limiting the applicability of these findings to non-European populations. Latin America and the Caribbean, regions marked by diverse genetic admixture, distinct environments, and healthcare disparities, remain critically understudied in psychiatric genomics. This threatens access to precision psychiatry, where diversity is crucial for innovation and equity. This Review evaluates the current state and advancements in psychiatric genomics within Latin America and the Caribbean, discusses the prevalence and burden of psychiatric disorders, explores contributions to psychiatric GWAS from these regions, and highlights methods that account for genetic diversity. We also identify existing gaps and challenges and propose recommendations to promote equity in psychiatric genomics.

Keywords: Latin America, Caribbean, Psychiatric genetics, Genome-Wide Association Study, Diversity, Psychiatry, Mental Health, Admixture

Psychiatric disorders are a significant global concern, affecting 1 in 8 people worldwide1. Given their significant heritability, psychiatric genetics research can elucidate how genetic variants affect mental health and improve treatment and prevention strategies. Large initiatives such as the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) have indeed provided crucial insights into the molecular basis of psychiatric disorders. However, most genetic discoveries in psychiatric genetics primarily involve individuals of European descent2,3. Over the past five years, 85% of participants in large scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analyses have been of European ancestry (Supplementary Table S1). This imbalance limits our understanding of psychiatric genetics across diverse populations and may exacerbate healthcare disparities3–5.

Expanding studies to include a wider diversity of populations could accelerate gene discovery and uncover novel molecular mechanisms underlying disease risk4,6, particularly as complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors shape psychiatric disorders7. Latin America and the Caribbean, which account for 8.2% of the global population (Box 1), present a unique opportunity for studying these interactions due to their heterogeneous environment and admixed populations8–10. It is crucial to acknowledge that this region is not monolithic; Latin America and the Caribbean comprise a diverse range of languages, cultures, and significant environmental and genetic variability both within and between countries (Fig. 1). However, the region has been significantly underrepresented in large-scale genomics studies, partly due to the challenges of accounting for its complex population structure and environmental heterogeneity, as well as economic barriers to research, such as limited funding and infrastructure.

Box 1. Latin America and its People.

In the context of Latin America, “Hispanic” refers to populations with Spanish heritage. In contrast “Latin American” or “Latino” encompasses all Latin American individuals, including those who speak Spanish, Portuguese, French, and native languages, as well as populations influenced by later migrations from Europe and Asia, reflecting a broader and more diverse geographical and cultural identity that includes influences from many other countries. Although the primary languages in Latin America are Spanish and Portuguese, the continent is home to hundreds of Indigenous languages.

Latin America is a large region in the American Continent comprising countries from South America (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, French Guiana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, and Venezuela), Central America (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama), North America (Mexico), and the Caribbean islands (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Martinique, Puerto Rico, Saint Barthelemy). Mesoamerica, on the other hand, is a historical and cultural region within Latin America. It spans central Mexico and extends into much of Central America, covering parts of Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Recognized for its rich pre-Columbian history, Mesoamerica was home to advanced civilizations, such as the Olmec, Maya, Aztec, and Zapotec, which significantly shaped the cultural and historical identity of the Americas.

There are several hypothesized models regarding the settlement of the Americas, with current archaeological evidence supporting both terrestrial and coastal migrations that likely occurred after the Last Glacial Maximum, primarily between 16,000 and 13,500 years ago, prior to widespread Paleoindian occupations10. The colonization of Latin America was characterized by European conquests, primarily by the Spanish and Portuguese, along with the exploitation of Indigenous populations, the forced displacement and enslavement of Africans, and successive waves of European and Asian immigrants. These events have resulted in a culturally diverse region shaped by four primary continental ancestral populations: Amerindigenous, European, sub-Saharan African, and Asian. Brazil is the largest country in Latin America and is a prime example of heterogeneity and admixture. In the south of the country, European ancestry is more prevalent (>80%), followed by African (10%) and Indigenous (10%) ancestries (similar to Argentina and Uruguay). The proportion of African ancestry increases in the Northeast (approximately 30%, similar to Cuba and Venezuela), and Indigenous ancestry increases in the North (Amazonian region, nearly 19%), which is smaller than in Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, and Bolivia, countries with the highest Indigenous ancestry in Latin America8,9.

Fig. 1. Genetic diversity in Latin America.

Genetic ancestry of individuals from six Latin American and Caribbean countries (Mexico, Puerto Rico, Barbados, Colombia, Peru, and Brazil) based on data from the 1000 Genomes Project and the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP). The principal components analysis (PCA) plots illustrate genetic ancestry distribution patterns using the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), which capture the largest fractions of ancestry variation. In the top PCA plot, individuals are arranged in a triangular pattern: the apex clusters those with predominantly European ancestry, the bottom left represents individuals with primarily African ancestry, and the bottom right corresponds to those with mainly East Asian ancestry. A degree of separation is observed among these three major groups. In contrast, the bottom PCA plot highlights samples from Latin America and the Caribbean, revealing a heterogeneous pattern. Individuals from this region are highly admixed, dispersing broadly across the PC1 and PC2 ancestry distributions. The continental map indicates the locations in Latin America and the Caribbean where the samples were collected. The data used to generate the plots were downloaded from gnomAD149 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).

Increasing the representation of Latin American populations in psychiatric genomics is crucial for accurately capturing genetic and environmental diversity. The Latin American Genomics Consortium (LAGC) (https://www.latinamericangenomicsconsortium.org/) is an initiative aimed at advancing psychiatric genomics research in Latin America by fostering collaboration among researchers from the region and internationally, while supporting capacity-building efforts. This Review, authored by LAGC members, provides a comprehensive overview of psychiatric genomics research involving Latin American and Caribbean populations. Drawing on our collective expertise, we identify critical gaps, challenges, and opportunities in the field, while outlining future research directions to promote equity and inclusion in psychiatric genomics.

Prevalence and burden of psychiatric disorders in Latin American populations

Data on psychiatric disorders from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study indicates a global mean prevalence of 14.0%. For Latin America and the Caribbean, the GBD estimates an average prevalence of 15.7%, with a range from 10.7% to 19.4%1. Meta-analysis of epidemiological studies across the Americas reveal significant heterogeneity in prevalence estimates11. The weighted mean 12-month prevalence of mental disorders is 17.0% for the entire continent, with North America at 22.5% and Latin America at 14.8% (9.7% in Mesoamerica and 17.0% in South America)12. Anxiety and depressive disorders are the most prevalent mental illnesses in Latin America, consistent with global trends (Fig. 2a)1. However, country-specific estimates vary widely, from 7.2% in Guatemala to 29.6% in Brazil12. Lifetime prevalence rates are even more concerning, reaching 45% in both the United States (USA) and Latin America13,14.

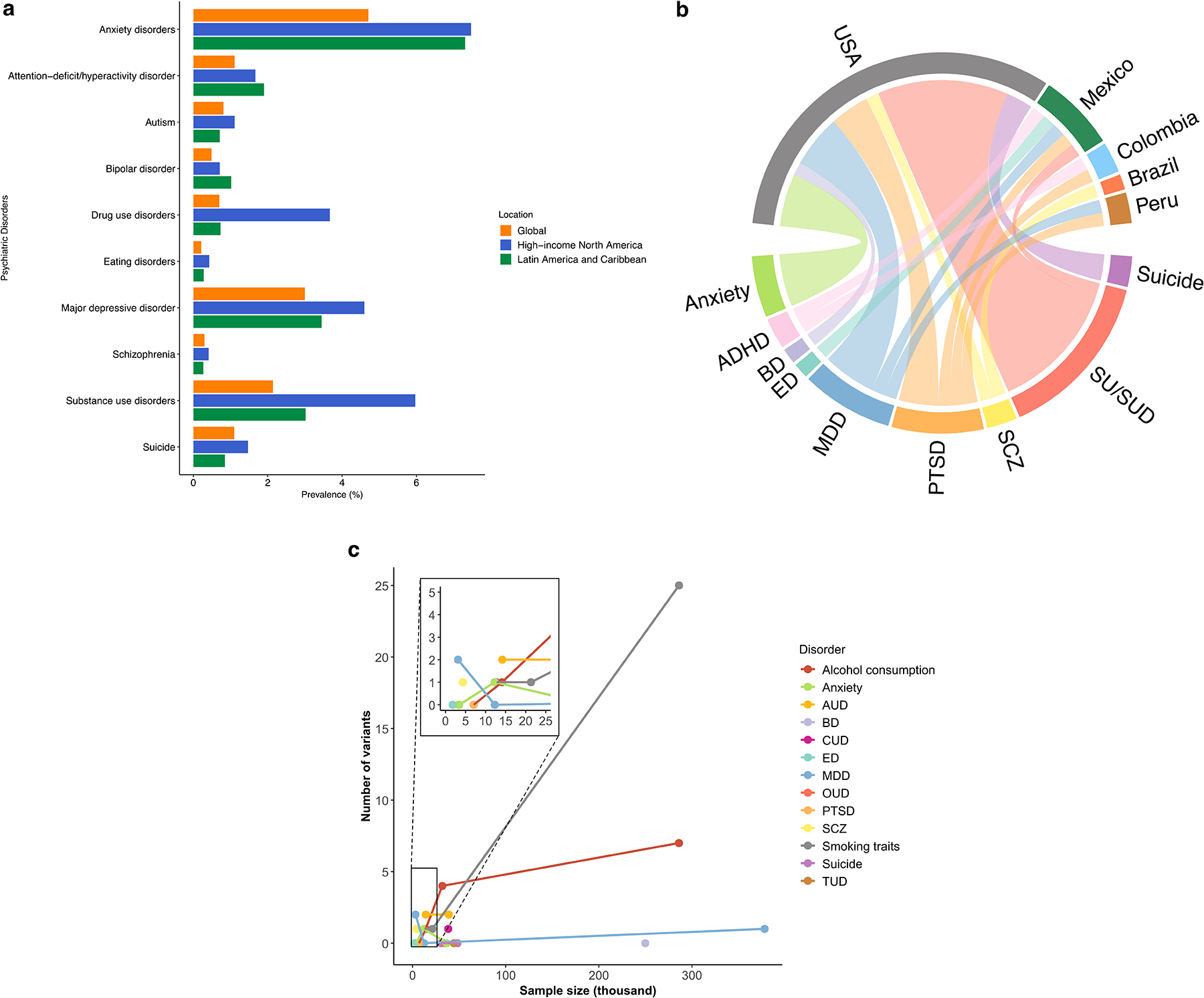

Fig. 2. Psychiatric genetics research in Latin America.

This figure highlights the progress and challenges in psychiatric genetics research in Latin American populations. (a) Bar plot comparing the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Latin America, high-income North America, and globally, based on data from the Global Burden of Disease study (GBD 2021, VizHub at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). (b) Chord diagram showing the relationship between GWASs and the countries and disorders studied, with most Latin American samples coming from the USA, and substance use being the most frequently researched psychiatric trait. (c) Scatter plot illustrating the sample size of GWAS studies in Latin American populations, showing that larger studies, such as those on substance use, have greater power to identify significant loci. Notes: Drug use disorder includes conditions involving opioids, amphetamines, cocaine, cannabis, and other drugs. SUD combines data from both alcohol and drug use disorders. ED include anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Abbreviations: GWAS: genome-wide association study; ADHD: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; AUD: Alcohol Use Disorder; BD: Bipolar Disorder; CUD: Cannabis Use Disorder; ED: Eating Disorder; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; OUD: Opioid Use Disorder; SCZ: Schizophrenia; SU/SUD: Substance Use and Substance Use Disorder; TUD: Tobacco Use Disorder.

In terms of disease burden, psychiatric disorders accounted for 19.8% of total Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) in 2021 and 6.7% of total Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in Latin America and the Caribbean1. There are significant differences when compared to high-income North America (USA, Canada, and Greenland), where substance use disorders (SUDs) present a higher impact on YLDs and DALYs (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Although obtaining accurate data on deaths attributable to psychiatric disorders is challenging, it is noteworthy that in Latin America and the Caribbean, this measure was seven times lower than in high-income North America in 2021 (Supplementary Table S4). The discrepant estimates between Latin America and the Caribbean and high-income North America may result from variations in the diagnosis and reporting of these events across countries and regions.

Access to evidence-based treatment for psychiatric disorders is severely limited in Latin America and the Caribbean. The weighted mean treatment gap for moderate to severe disorders across the Americas, based on service utilization studies and mental health surveys, is 65.7%, with a smaller gap in North America (53.2%) compared to Latin America (74.7%), which includes Mesoamerica (78.7%) and South America (73.1%)12. These disparities are even more pronounced among minoritized groups. For example, estimates in some sampled tribes showed that while one-third of the indigenous population in the USA had not received psychiatric treatment, the rate increases to 80% in Latin American countries12.

In the Americas, the median mental health expenditure is 2.4% of health budgets, ranging from 0.2% to 8.6%15. Worldwide, low-income countries allocate about 1.1%, lower-middle-income 1.1%, upper-middle-income 1.6%, and high-income 3.8%16. Developed countries invest more effectively, while less developed countries face inefficiencies in funds allocation (e.g., investing large amounts in psychiatric hospitals)15. The funding imbalance also exists in mental health research, potentially impacting the availability and accuracy of prevalence and burden estimates. A recent systematic review of a decade of psychiatric genetics publications in Latin America highlighted a profoundly unequal research landscape17. The majority of studies were concentrated in Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia. Local funding is generally inadequate for large-scale GWAS in the region with Brazil and Mexico somewhat less impacted17.

The current state of psychiatric genetics in Latin American populations

Psychiatric disorders encompass a wide range of conditions and traits, with heritability estimates from twin studies ranging from 35% to 80%18. However, it is important to note that most of these heritability estimates are based on individuals of European ancestry, which limits their generalizability. Early efforts in genomics of psychiatric disorders in Latin American populations used linkage and candidate gene approaches17. GWAS research in Latin America and the Caribbean has predominantly been conducted in small cohorts19–23. More recently, several large-scale, trans-ancestry GWAS of psychiatric disorders—encompassing hundreds of thousands to millions of participants—have faced challenges in including representative Latin American samples, with most participants being based in the USA24–31.

In the next sections, we summarize the current state of GWAS on psychiatric disorders and diagnoses in Latin American and Caribbean populations (see Supplementary Table S5). We also present initiatives involving whole exome (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS).

Autism

Autism is a heterogeneous condition characterized by a broad range of phenotypic features, including deficits in social communication and interaction, and repetitive or ritualistic behaviors32. The prevalence of autism in Latin American countries is comparable to global estimates, around 1%1. European population-based studies report heritability estimates ranging from 50% to 83%, depending on the model and the country studied33. However, the precise heritability of autism in Latin American populations has yet to be thoroughly evaluated.

In contrast with most psychiatric disorders, the understanding of the genetic architecture of autism has advanced significantly through the identification of rare variants (frequency < 1%), mostly represented by de novo and inherited copy number variants (CNVs), as well as single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or indels under negative selection34–36. Although hundreds of genes have been associated with autism in the past years, only 5% to 20% of autism cases are related to a known pathogenic or rare genetic risk variant35,36. These variants can confer a large impact on individual risk for autism, with odds ratios—a statistical measure that quantifies the strength of association between two events—ranging from 20- to 100-fold. They are often associated with multiple neurodevelopmental comorbidities34,36,37. The Autism Sequencing Consortium (ASC) and the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) have included samples of diverse ancestry, but Latin American populations remain largely underrepresented34. Of note, the few studies conducted in Latin America (all from Brazil) highlight the importance of rare CNVs and de novo SNVs in the etiology of autism38–40.

Notably, most cases of autism are thought to involve more complex inheritance patterns, such as oligogenic or multifactorial models35,41, where both rare and common risk variants can contribute to its etiology. Published common variant meta-analyses in autism have been relatively modest in size, implicating NEGR1, PTBP2, CADPS, KCNN2, KMT2E, and MACROD2 as risk genes, with rare pathogenic variants within some of these genes also being reported41. Additionally, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based heritability has been estimated as 11–13%, confirming the relevance of common variants in autism41.

A recent large WGS study revealed 134 autism-associated genes, along with structural variants that would be missed without WGS. Of the more than 23,000 WGS samples analyzed, 980 were classified as “admixed Americans” with an additional 520 predicted to be “admixed”35.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and/or impulsivity with significant executive dysfunction42. The GBD prevalence of ADHD across all ages is estimated at 1.1%, while in Latin America, it is 1.9%1. These figures differ significantly from those found in meta-analyses, which suggest a worldwide prevalence of 8% in children43 and 2.6% in adults44. Moreover, the only comprehensive prevalence analysis in Latin America, a large three-decade birth cohort study in Brazil, found ADHD prevalence estimates in adults to be 2.1% and 5.8% for symptomatic ADHD45.

Estimates from twin studies suggest that ADHD has a pooled heritability of 76% in both children and adults46. Most ADHD GWAS have been conducted in populations of European ancestry47–49. Among these, only one GWAS and an exome chip study included individuals from Latin America, a sample from Brazil with a high degree of European descent47,49. Recently, a GWAS of a small sample of 576 Mexican and Colombian individuals19 investigated the relationship between admixture and genetic susceptibility to ADHD using novel analytical approaches, such as local ancestry. In the analysis of genetic associations at known ADHD GWAS loci, the most suggestive SNVs were found in the PTPRF gene. However, no genome-wide significant (GWS) variants were detected in the local ancestry analysis19.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder characterized by diverse psychopathology, including positive (psychosis and disorganization) and negative symptoms and cognitive impairment32,50. The prevalence is similar between Latin American populations and global estimates (around 1%)1, and increases significantly when considering all psychotic disorders (up to 3.5%)51. Twin studies of schizophrenia have reported high heritability estimates (60–80%)18,50. Initial schizophrenia GWAS were among the first to successfully identify GWAS loci associated with any psychiatric disorder52,53. Historically, these early efforts were conducted in individuals of European ancestry. More recently, other non-European ancestry studies have begun to emerge, mainly of Asian descent54. However, there is still a lack of studies with significant sample size of Latin American and Caribbean populations.

The largest schizophrenia GWAS in Latin Americans included over 4,000 individuals (1,234 cases and 3,090 controls)55. This study identified GWS variants in the GALNT13 gene, a finding not previously reported in European populations. The same study combined Latin Americans with Europeans, identifying 114 SNPs across 101 loci, 8 of which were novel55. The latest GWAS meta-analysis also incorporated the aforementioned Latin American sample56. In this trans-ancestry study that combined data from 76,755 cases and 243,649 controls, the number of genomic loci expanded to 28756. Additionally, a trans-ancestry WES meta-analysis in over 100,000 individuals, including 1,388 cases and 15,154 controls of Latin American origin, revealed ultra-rare coding variants in 10 genes, partially overlapping with the GWAS findings28.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a chronic condition characterized by recurrent episodes of (hypo)mania and depression, which impact thought, perception, emotion, and social behavior32. The prevalence in Latin America and the Caribbean has been reported to be twice as high as global estimates (Fig. 2a)1. However, the reasons for this difference are still debated, with factors such as variations in diagnosis or ascertainment potentially playing a role. Bipolar disorder is highly heritable with twin studies estimating a heritability of 60–85%18 and a SNP-based heritability of 18–20%57.

Previous large-consortia bipolar disorder GWAS have not included Latin Americans57. Replication studies of previously identified bipolar disorder GWAS hits in European ancestry have been reported in Latin American populations from Brazil20, USA, Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica21. Additionally, a small (n=32) WES study in Cuban individuals identified 17 non-synonymous rare variants associated with bipolar disorder58. Common and rare variants have also been explored in Colombian, Costa Rican, and Mexican pedigrees showing a modest increase (P-value range: 0.002–0.047) in the burden of rare deleterious variants in bipolar diosrder59. Most bipolar disorder studies in Latin America and the Caribbean have primarily focused on linkage-based designs in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder60.

A recent multi-ancestry GWAS meta-analysis of 158,036 bipolar disorder spectrum cases and 2,796,499 controls combining clinical, biobank, and self-report samples identified 337 independent GWS variants mapping to 298 loci (a 4-fold increase over previous finding)25. Of this sample, 13,022 cases and 236,822 controls were of Latin American origin (only USA-based cohorts). However, no GWS variants were identified in this subsample25.

Major depressive disorder (MDD)

MDD is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness and loss of interest or pleasure (anhedonia) accompanied by changes in weight, sleep, and energy, reduced concentration, feelings of worthlessness, and suicidal thoughts32. The 2021 GBD prevalence of MDD was similar between Latin America countries and global estimates (around 3.0%)1; however, a meta-analysis of 40 population-based studies in Latin America reported a 12-month prevalence estimate of 12.6%61. MDD heritability estimated from European twin studies is 37%62, which is similar to the estimates reported in 1,122 Mexican-Americans from 71 extended pedigrees: 39% for MDD, 46% for recurrent depression, and 49% for early onset depression63. Despite the fact that MDD and broad depression together with substance-use disorders (SUDs) are the traits with higher representation of Latin American populations in psychiatric genomics, most of this work still overwhelmingly involves samples of European ancestry64–66.

In a Mexican-American cohort of 203 cases and 196 controls, 44 common and rare functional variants were reported to be associated with depression, including variants in the PHF21B gene67. In the same study, rare variant analysis replicated the association of PHF21B in an unrelated European-ancestry cohort. Subsequently, in a study of 12,310 individuals from the USA-based Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) cohort68 investigating depressive symptoms, SNP-based heritability was estimated as ~7%, but no GWS SNPs were identified, nor were findings from previous European-ancestry studies replicated68.

A large-scale MDD GWAS included over 1.3 million individuals (371,184 cases) and conducted an additional GWAS on admixed ancestry outliers (10% of the total sample)69. This study revealed a high genetic correlation (genetic correlation = 0.95, P=1×10–4) with the primary European meta-analysis69. Additionally, a multi-ancestry GWAS that included 25,013 cases and 352,946 controls in the Hispanic/Latin American group showed a GWS locus (rs78349146, colocalization for DPP4, RBMS1, and TANK)26. Interestingly, this locus did not display strong evidence of association in a large published GWAS of individuals of European ancestry65, potentially highlighting that increased diversity enhances variant and gene discovery.

Finally, a meta-analysis from the PGC-MDD working group, which included 688,808 cases and 4,364,225 controls making it the largest to date in psychiatric genomics, identified 697 GWS-independent loci, 293 of which were novel70. Polygenic scores (PGS)—an aggregated genetic risk estimate—trained using either European or multi-ancestry data significantly predicted case-control status across all diverse ancestries, including those of Latin American origin (19,927 cases and 340,403 controls). However, no specific GWAS findings are described for this group70.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders, namely generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and phobias, can exhibit excessive worry, accompanied by feelings of restlessness, avoidance behavior, and physiological changes such as increased heart rate, shortness of breath, and elevated blood pressure32. Epidemiological data from GBD estimate the prevalence of anxiety disorders at 4.7% worldwide and 7.3% in Latin America and the Caribbean (Fig. 2a)1. Heritability estimates from twin studies are moderate, ranging between 30% and 40%71.

Large-scale GWAS for anxiety are relatively recent, with nearly all participants being of European ancestry72–75. The first GWAS of GAD in a Latin American sample included 12,282 individuals from the HCHS/SOL76 and reported one GWS locus (rs78602344, THBS2 gene). However, the finding was not replicated in three independent USA-based Hispanic cohorts, which included the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (n=1,449), Women’s Health Initiative (n=3,352), and the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS) (n=3,394)76. For anxiety scores, which are estimated using a factor analysis approach, no GWS association was observed in a GWAS conducted in Army STARRS, which included 3,438 Latin Americans (20% of the study sample)77. Using the same sample, a subsequent study phenotyped participants to approximate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-based anxiety diagnoses. Once again, no signal was detected in the Latin American group78.

The most recent GWAS meta-analysis comes from a preprint from the PGC anxiety working group; it included 852,000 individuals (122,000 cases) and reported 58 independent GWS variants, 51 of which were replicated in an independent sample75. However, this study was limited to European ancestry, providing no insights into anxiety genetic risk in diverse individuals. In another recent study, a meta-analysis of GWAS on anxiety disorders involving 1,266,780 individuals, including 36,634 Latin Americans (classified as “Admixed-Americans”) from the All of Us Research Program24, but no GWS variants were detected. However, the cross-ancestry meta-analysis identified 41 GWS loci, 10 of which were novel24.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

OCD is characterized by unwanted, recurrent, and distressing thoughts, images, or impulses (obsessions) and/or repetitive behaviors (compulsions)32. There are similar OCD prevalence rates between Latin America and the USA (ranging from 1.4% to 2.3%)79,80. A meta-analysis including twin and family studies estimated a heritability of 50%81.

OCD has been the subject of two WES studies that included Latin American trios from Brazil. The first was a pilot study82 that performed WES on 20 sporadic OCD cases and their unaffected parents to identify rare de novo mutations (DNMs). An elevated rate of rare DNMs was detected82, which was followed up in a larger WES study of 222 OCD trios, including 42 from Brazil83. Two high-confidence risk genes were identified, each containing two damaging DNM in unrelated probands: CHD8 and SCUBE183. The findings were subsequently updated by a study that analyzed WES data from the largest OCD cohort to date, which included 1,313 cases of diverse ancestry, comprising 587 trios, 41 quartets, and 644 singletons84. This study identified SLITRK5 as the most significant gene (odds ratio = 8.8, P = 2.3e-6)84.

Regarding common variation, the first well-powered OCD GWAS was led by the PGC-OCD working group and recently posted as a preprint85. While the sample size (53,660 cases and ~2 million controls) greatly exceeds prior studies and revealed 30 independent GWS loci, the study included only individuals of European ancestry from 28 cohorts85. An ongoing OCD collection in Latin America countries will provide a starting point for trans-ancestry analyses, but further large scale collection is needed to power these analyses86.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is a debilitating condition initiated by traumatic experience, with subsequent pathological re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms32. The lifetime prevalence in Latin American populations is approximately 3.8%87, compared to a broader range of 3.4% to 26.9% reported in the US88. Twin-based heritability estimates range from ~23–71% following trauma exposure89. Large-scale PTSD GWAS90–93 have identified replicable signals, although investigation into Latin American samples has so far been limited. Two small, single-site PTSD GWAS, one involving high-risk Latin American individuals in the USA (n=254)94 and another focusing on Brazilian women (n=117)95, were conducted but did not identify GWS loci94,95.

The primary study from the PGC-PTSD working group conducted a GWAS on 5,703 Latin Americans from a sample of over 200,000 individuals92. No GWS loci were identified in the Latin American group, nor did it replicate GWS findings from European-ancestry analysis92. More recently, the updated PGC-PTSD multi-ancestry meta-analysis27 expanded the sample to 7,017 Latin American individuals from the USA, as well as Peru, Colombia, and Mexico. Although no GWS loci were identified in this group, the multi-ancestry meta-analysis in 1,222,882 participants identified 95 GWS loci27. Relative to new efforts, the Veterans Affairs “Million Veteran Program” (MVP) contains over 50,000 Latin American origin participants96; a forthcoming large-scale PTSD GWAS including these individuals is anticipated.

Feeding and eating disorders

Eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder (BED), and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), are characterized by dysregulated eating, weight, and body size or shape perception, significantly affecting a patient’s quality of life32. While the prevalence of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is similar between Latin American countries (0.28%) and global estimates (0.21%)1, lifetime prevalence of BED in Latin America varies considerably as it has been reported to be lower than (Colombia 0.9%), on par with (Mexico 1.6%) or even higher (Brazil 4.7%) than the global average (1.9%)97. The prevalence of ARFID across Latin America remains unknown. Twin and population-based studies report eating disorder heritability estimates between 28% and 88%, varying by specific disorder analyzed98,99. Studies evaluating eating disorder heritability in Latin American populations are still scarce, although estimates for eating-disorder-related traits are available. For example, a heritability of 51% was reported for eating in the absence of hunger in Latin American children100.

Eating-disorder GWAS lag behind other psychiatric disorders with the majority of studies having been performed on anorexia nervosa and in individuals of European ancestry101–103. Although no well-powered eating-disorder GWAS have been conducted in Latin American individuals yet, two GWAS have been reported in small Mexican cohorts, these focused on disordered eating104 and eating disorder105 with no GWS loci identified104,105.

Substance use and SUDs

SUDs occur when the recurrent consumption of alcohol and/or drugs causes significant impairment, including health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home32. More than 17 million people have had SUDs in Latin America, accounting for a prevalence of 3.0%, which is higher than the worldwide prevalence estimated at 2.1%1. SUDs have heritabilities that range from 50% to 60%, depending on the specific substance18.

Large-scale substance use and SUD GWAS, led by the GWAS and Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine Use (GSCAN), MVP, and PGC, including individuals of Latin American origin22,30,106–110, have mostly focused on alcohol and smoking-related traits. Among the main and most replicated GWS findings identified in Latin Americans is the rs1229984 in the ADH1B gene, a protective variant associated with alcohol consumption106,107,110 and alcohol use disorder107,111. A recent phenome-wide association study of three of the best known protective SNPs in genes encoding ethanol-metabolizing enzymes, including rs1229984, examined Latin American populations from the 23andMe cohort112. In the Latin American group (n = 446,646), rs1229984-T was associated with 29 traits across 13 categories, with the strongest associations of the protective allele observed with alcohol-related traits, such as alcohol flush and wine headache, as well as health conditions, including respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders112.

The latest (and largest thus far) GWAS of substance use was conducted by GSCAN in over 3.4 millions individuals from four ancestral populations, including Latin American individuals (admixed Americans, n = 286,026)29. This study identified over 3,000 independent risk variants associated with smoking and alcohol consumption traits, where 25 GWS risk loci were observed in the Latin American sample29. Another recent multi-ancestry GWAS evaluating problematic alcohol use in over 1 million individuals identified 110 GWS risk variants111. This study included 38,962 Latin Americans (all from MVP cohort) and reported a SNP-based heritability of 12.4% and one significant association with rs1229964 in this population111.

For smoking phenotypes, several variants in the region of CHRNA5/A3/B4 cluster genes, which encodes the cholinergic nicotinic receptor α5, α3 and β4 subunits, respectively, were associated with heaviness of smoking in 12,741 Latin Americans from the HCHS/SOL cohort108. Another GWAS evaluating smoking initiation trajectory found an association near the RIMS1 gene in 21,336 Latin American individuals109. Additionally, a recent multi-ancestral meta-analysis of tobacco use disorder examined data from four biobanks including 653,790 individuals, of whom 44,365 were Latin Americans. This study reported a significant SNP-based heritability of 8.1% in the Latin American group, but no GWS variants were identified30.

For cannabis use disorder, a recent large-scale meta-GWAS in over 1 million participants also included 38,219 Latin Americans (2,774 cases)113. This study revealed a SNP-based heritability of 7.2% and identified one locus (rs9815757) mapping to an intergenic region downstream LRRC3B. This risk variant has a low frequency (0.1%) and has not been previously reported for other ancestral groups, warranting further replication in larger cohorts113. For opioid use disorder, a multi-ancestry meta-GWAS reported 14 GWS loci (of which 12 were novel), including those mapping to OPRM1 and FURIN. This study examined 34,861 Latin American individuals and identified a potential ancestry-specific locus, rs24394925, located at the MRS2 gene114. In contrast, no large-scale GWAS of cocaine use disorder has yet focused on Latin American populations, underscoring a significant research gap for this SUD.

Notably, large-scale substance use and SUD GWAS have been mostly limited to Latin American populations based in the USA, with the exception of one study22. This GWAS evaluated substance use in 3,914 Mexicans, and no GWS variant was detected22.

Suicide

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide, ahead of malaria, acquired immune deficiency syndromes, breast cancer, and homicide115. The global and Latin American rates of suicide were estimated at 9.5 and 7.1 per 100,000, respectively1. These estimates are lower than those observed for high-income North America (15.0 per 100,000). However, some groups in Latin America present comparable metrics, such as some indigenous populations and municipalities in southern Brazil, with 16.6116 to 19.5117 per 100,000. Although there has been a decrease in suicide rates worldwide since 2016, suicide mortality is on the rise in several Latin American countries, representing about 10% of all injury-related deaths116.

Evidence from family, twin, and adoption studies suggests that heritability of suicidal behaviors ranges from 30% to 55%118. The first large-scale GWAS meta-analyses of suicide behaviors and death have not included Latin American individuals119,120. However, a small GWAS in a Mexican sample of 192 cases with at least one suicide attempt found suggestive gene-level results for SCARA5, GHSR, RGS10, and STK3323. Notably, none of these genes overlapped with the suggestive findings reported in GWASs of European ancestry samples119,120. The largest multi-ancestry GWAS to date on those who have attempted suicide included 43,871 cases and 915,025 controls31. This study was limited to a single Latin American cohort from the MVP, which included 1,271 cases and 29,306 controls. The SNP-based heritability for the Latin American group was estimated at 10.0% (standard error = 6.5%). The genetic correlation of suicide attempt between individuals of European ancestry and those of Latin American origin was 0.997. No GWS variant was detected in this single cohort31.

Finally, a GWAS of suicide ideation from the MVP was conducted, and ancestry-specific results were combined in a meta-analysis121. Four GWS loci were identified in this pan-ancestry study. Additionally, gene-based analysis identified associations with DRD2, DCC, FBXL19, BCL7C, CTF1, ANNK1, and EXD3 genes. No GWS locus was found in the Latin American group, which comprised 10,652 cases and 37,547 controls. However, the inclusion of diverse samples doubled the number of GWS hits found (compared to the two loci identified in the European ancestry group alone)121, providing a strong argument for the increase in power to detect loci enabled by the inclusion of diverse populations as previously discussed.

Social Determinants of Mental Health (SDoMH) and gene-environment interactions

SDoMH encompasses characteristics of the environment where individuals are born, live, work, and grow, which play a significant role in influencing mental health outcomes and the risk of psychiatric disorders. These factors are typically categorized into domains, such as economic stability, education access and quality, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context122. Genetic studies should take SDoMH into account because most models for psychiatric disorders consider both genetic and environmental factors. Therefore, it is expected that SDoMH interacts with genetics, affecting genetic predispositions in different ways across populations. Evaluating these determinants is especially crucial in regions with high environmental diversity, such as Latin America123. To ensure representativeness and capture environmental and social diversity, probabilistic sampling is recommended, which is essential for accurate genetic and environmental assessments.

Although limited, research in Latin America has demonstrated that SDoMH plays a critical role in predicting neuropsychiatric outcomes124,125. A study examining populations from Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico, and Peru found that social and environmental factors are more predictive of dementia than genetic ancestry123. This suggests that, in highly unequal countries, social factors may confound or outweigh genetic influences. Additionally, studies on SDoMH and gene-environment interactions may reveal relevant factors that affect psychiatric disorder risk in Latin America, which could differ from those in the USA, Europe, or Australasia126. However, there is a lack of GWASs focused on gene-environment interactions in Latin American populations, with only few studies exploring interactions, such as childhood trauma or household income, and their effects on psychiatric disorders127.

Gaps and methodological considerations for genomic analysis in admixed Latin American populations

Some moderate to large-scale GWASs of psychiatric disorders and related traits have included individuals of Latin American origin, with sample sizes ranging from ≅1,000 to over 300,000 and a small number of GWS loci identified. Advances in gene discovery have been observed particularly in substance use and SUDs with a total of 10 GWAS identifying 39 and 8 GWS loci respectively for substance use traits and SUDs (Fig. 2b–c). A significant limitation of the few large-scale GWASs conducted that included Latin American participants is their lack of representation of the diverse and heterogeneous groups across the Americas, with over 88% of these studies focusing on individuals living in the USA. Among the Latin American countries currently represented in these studies—Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile—significant gaps remain in the inclusion of other Latin American countries (Fig. 2b).

Notably, recent genomic studies in Latin Americans have expanded beyond standard GWASs, utilizing technologies, such as WGS and WES. Successful examples of these efforts include a WES study of over 15,000 Latin American individuals, which identified ultra-rare coding variants associated with schizophrenia28. The ongoing projects within the Ancestral Population Network (APN)128 are contributing samples for Blended Genome Exome (BGE) sequencing, a cost-effective alternative to traditional genotyping arrays and deep WGS. BGE combines high-coverage WES (30–40x) with low-pass WGS (2–3x), enhancing the detection of common and rare genetic variants across ancestries. This approach holds significant promise for advancing local ancestry analyses in large-scale genomic collections129.

Although progress has been made, significant gaps persist in identifying genes associated with psychiatric disorders in Latin American populations. This challenge is further compounded by methodological hurdles that impede advancement. Traditional genomic analysis methods, originally designed for genetically homogeneous populations, fail to effectively account for the complexities and unique advantages of studying admixed genomes. Considering that the majority of causal variants are shared across populations3, the inclusion of understudied admixed populations is essential for identifying both novel and shared genetic variants, especially those with varying frequencies across ancestries. Moreover, the unique linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns in admixed populations - characterized by shorter LD blocks due to recombination events over generations - offer finer resolution for pinpointing causal variants.

Ongoing research is developing strategies to address the methodological challenges when analyzing admixed populations130 (Supplementary Table S6). Quality control (QC) criteria have been refined for multi-ancestry studies3,130; however, a standardized QC pipeline for admixed populations is still lacking. Further, heritability estimates, which depend on population-specific factors, such as allele frequencies and effect sizes, can now be refined using novel approaches. These include SNP-based heritability estimation methods that adjust LD score regression to account for ancestral components131, or leverage summary statistics from admixture mapping to calculate heritability explained by local ancestry132. While admixture mapping has been successfully applied to Latin American cohorts for various complex traits133–135, emerging approaches further improve the modeling of admixture in genomic analysis136,137. For example, the Tractor pipeline employs regression models to analyze genotype counts specific to each local ancestry137. This method thereby generates ancestry-specific effect size estimates, enhancing the power to detect associations, especially where effect sizes differ across ancestries. For PGS, recent statistical models tailored for admixed populations incorporate local ancestry to improve phenotype prediction138–140 (Supplementary Table S7). However, transferability of PGS across diverse ancestries remains a major research challenge, which is exacerbated by the lack of representation of Latin Americans in discovery GWAS and the scarcity of diverse individual-level genetic data.

Towards sustainable, equitable psychiatric genetics research in Latin America

Diversifying psychiatric genetics research is imperative not only because of scientific reasons to unravel disease biology, but also because of ethical concerns in order to avoid the exacerbation of global health disparities141. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the increasing prevalence and burden of psychiatric disorders1, coupled with substantial diagnosis and treatment gaps and systemic barriers12, highlight the urgent need for more effective and equitable mental health solutions. Expanding genomic resources and developing tools that better integrate ancestry-specific information is essential for addressing long-standing gaps in psychiatric genetics research. By incorporating diverse genetic data from underrepresented populations, psychiatric genomics can enhance the accuracy and applicability of findings across ancestry groups. Additional gaps and challenges span scientific, social, and ethical dimensions (as highlighted in Box 2). Addressing these demands a paradigm shift of the research landscape towards collaborative, equitable, and sustainable research142.

Box 2. Current status of and potential opportunities to advance psychiatric genetics research in Latin America.

| Gaps and Challenges | Recommendations and Solutions |

|---|---|

Limited inclusion of Latin American individuals in genomic studies

|

Consortia-building efforts, community-engaged research and funding sources

|

Lack of diversity in the researcher workforce

|

Training and career development programs

|

Biocolonialism and mistrust

|

Capacity building and equitable and sustainable collaborations

|

Lack of methodology and reference panels to account for complex admixture

|

Novel methods and reference panels

|

Heterogeneity of outcomes and diagnosis assessment

|

Appropriate and standardized assessments

|

Tackling underrepresentation requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes sustainable capacity building, equitable global collaborations, increased resource access and funding, improved methods for analyzing admixed populations, standardized diagnostic and phenotyping methods, intentional community-based collaborations, and infrastructure development. Recent initiatives are working towards greater inclusion and diversity in psychiatric genomics research, including several those focused on Latin American populations. In addition to the LAGC, parallel efforts focused on specific psychiatric disorders are underway, such as GALA (autism), LATINO (OCD), CONNECT-ADHD, EDGI-Mexico (eating disorders), and PUMAS (schizophrenia and bipolar disorder)86,128,143–147 (Table 1), alongside with recent large-scale WGS efforts to characterize population structure, such as GenomaSUS-Brazil and the Mexico Biobank148. These efforts will contribute to the understanding of the genetic influences on psychiatric disorders in Latin American populations by helping bridge the gap for more inclusive and better represented genomic studies and give way to a more equitable and effective precision medicine enterprise.

Table 1.

Research initiatives of psychiatric genetic research in Latin American populations.

| Initiative | Psychiatric Disorder(s) | Countries involved | Description | Reference | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin American Network for the Study of Early Psychosis (ANDES) | Schizophrenia | Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico | Focused on genetic studies of early psychosis as well as clinical, cognitive, epidemiological, economic, and neuroimaging analyses. | 145 | https://www.cyted.org/andes |

| COllaborative Case-Control INitiativE in crack addiction (COCCaINE) | Substance use disorders | Brazil | Population-based genetic epidemiological study of cocaine use disorder in Brazil. | https://reporter.nih.gov/project-details/9709257 | |

| Comprehensive exploration of the CONNECTion between ADHD and educational attainment in contrasting environments (CONNECT- ADHD) | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Brazil | A project within the NIMH-funded Ancestral Populations Network (APN) and the LAGCADHD working group. | https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/dnbbs/genomics-research-branch/ancestral-populations-network-apn | |

| Eating Disorders Genetics Initiative - Mexico (EDGI-Mexico) | Eating disorders | Mexico | Focused on genetic studies of eating disorders in Mexico. | 143,146 | https://edgi.org/ |

| Genetic Architecture of Early-Onset Psychosis in Mexicans (EPIMEX) | Psychosis | Mexico and USA | To investigate the genetic architecture of early onset psychosis in a pediatric cohort from Mexico. | 128 |

https://www.epimex.net/

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/dnbbs/genomics-research-branch/ancestral-populations-network-apn |

| Genomics of Autism in Latinx Ancestries (GALA) | Autism spectrum disorder | Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and USA | A collaborative network between Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and the United States focused on the genomics of autism. | 128 | https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/dnbbs/genomics-research-branch/ancestral-populations-network-apn |

| Latin American Genomics Consortium (LAGC) | All psychiatric disorders | Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, USA, Canada, Spain, Australia | Established in 2019, the aim of the consortium is to advance psychiatric genomics research in Latin American populations. | https://www.latinamericangenomicsconsortium.org/ | |

| Trans-Ancestry Genomic Analysis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (LATINO) | Obsessive compulsive disorder | Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, USA | An NIMH-funded effort to collect DNA and comprehensive phenotypic data from 5,000 Latin American OCD cases. | 86,128 | https://orit.research.bcm.edu/latinostudy/en |

| Neuropsychiatric Genetics of Psychosis in Mexican Populations (NeuroMEX) | Bipolar disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia | Mexico | Aims to recruit 4,000 psychosis cases and 4,000 controls from Mexico. | 144,145 | https://www.broadinstitute.org/stanley-global/neuromex |

| Paisa Project | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder | Colombia | To establish a cohort of 8,000 mood or psychotic disorders cases and 2,000 healthy controls from the Paisa region in Colombia. | 145,147 | |

| Powering Genetic Discovery for Severe Mental Illness in Latin American and African Ancestries (PUMAS) | Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia | Brazil, Colombia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, South Africa, and USA | To recruit 40,000 schizophrenia cases, 40,000 bipolar disorder cases, and 40,000 matched controls. | 128 | https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/dnbbs/genomics-research-branch/ancestral-populations-network-apn |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil, Grant Number 2018/03254-7 (E.M.B.); National Institute of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) - NIMH Grant Number R01MH131013 (D.L.R.); FAPESP Grant Number 2020/05652-0 (D.L.R.), Kavli Institute for Neuroscience at Yale University Kavli Postdoctoral Award for Academic Diversity (J.J.M.M.); NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) - DP1DA054394 (C.M.N.), T32IR5226 (C.M.N.), Center for Brain and Mind Health Postdoctoral Fellowship (D.L.N.); NIMH R01MH125938 (R.E.P.), The Brain & Behavior Research Foundation NARSAD grant 28632 P&S Fund (R.E.P.), FAPESP 2023/05560-6 (M.L.S.), FAPESP 2023/12252-6 (C.E.B.), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (Grants 466722/2014-1, 424041/2016-2, 426905/2016-2, 405434/2023-5) (C.H.D.B.), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES, Finance Code 001) (C.H.D.B.), FIPE-HCPA (16-0600, 21-0254) (C.H.D.B.), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (19/2551-0001731-6, 19/2551- 0001668-9) (C.H.D.B.), NIMH R01MH136149 (C.M.B.); NIMH R01MH134039 (C.M.B.), NIMH R56MH129437 (C.M.B.); NIMH R01MH120170 (C.M.B.); NIMH R01MH124871 (C.M.B.); NIMH R01MH119084 (C.M.B.); NIMH R01MH118278 (C.M.B.); NIMH R01MH124871 (C.M.B.); Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award: 538-2013-8864) (C.M.B.), São Paulo Research Foundation (19/13229-2) (F.C.Z.); NIMH U01MH125050 (J.J.C.); Interdisciplinary Research Fellowship in NeuroAIDs (IRFN) - 5R25MH081482-17 (R.B.C.); Fulbright-Minciencias (J.F.D.H), Psychiatric Genomics Consortium - Substance Use Disorders, NIDA - 5R01DA054869 (J.G.); ANID/FONDECYT Regular (1210195 and 1210176 and 1220995) (A.I.); ANID/FONDAP/15150012 (A.I.); ANID/PIA/ANILLOS ACT210096 (A.I.); ANID/FONDAP 15150012 (A.I.); and the MULTI-PARTNER CONSORTIUM TO EXPAND DEMENTIA RESEARCH IN LATIN AMERICA [ReDLat, supported by Fogarty International Center (FIC) and National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Aging (R01 AG057234, R01 AG075775, R01 AG021051, CARDS-NIH), Alzheimer’s Association (SG-20-725707), Rainwater Charitable foundation - Tau Consortium, the Bluefield Project to Cure Frontotemporal Dementia, and Global Brain Health Institute)] (A.I.); NIMH - R01MH131013 (Y.C.L and V.F.O.); São Paulo Research Foundation (2020/15752-1) (C.M.L.); CASA Research Chair; One Child Every Child grant, University of Calgary (D.M.D.); NIH/NIDA DP1 DA054373 (Q.P.); Chilean National Agency for Investigation and Development, ANID Fondecyt grant 1221464 (E.P.P.); CONICYT FONDECYT Regular 1181365, ANID FONDEF ID19I10116 and ANID FONDEF ID24I10081 (M.L.P.); Fundação Universidade do Vale do Taquari de Educação e Desenvolvimento Social (FUVATES) (F.M.S.); National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (2023351083) (R.R.S.); NIMH U01MH125062 (E.A.S.); FAPESP 2023/05560-6 (M.L.S.); NIH/NHGRI R01HG012869 (E.G.A.); NIH/NIMH U01MH109528 to Patrick Sullivan; NIMH - K01MH121580 (G.R.F.), FAPESP 13/08028 (M.R.P.B.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests

C.M.B. reports receiving royalties from Pearson Education, Inc. S.L.L. is an employee of Novartis Pharma, the statements presented do not necessarily represent the position of the company. E.A.S. reports receiving research funding to his institution from the Ream Foundation, International OCD Foundation, and NIH. He was a consultant for Brainsway and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals in the past 12 months. He owns stock less than $5000 in NView (for distribution of the Y-BOCS and CY-BOCS). He receives book royalties from Elsevier, Wiley, Oxford, American Psychological Association, Guildford, Springer, Routledge, and Jessica Kingsley.

All other authors have no competing interests to report.

Latin American Genomics Consortium

(Full membership list is included in the Supplementary Material)

Estela M. Bruxel1,2, Diego L. Rovaris3, Sintia I. Belangero4,5, Gabriela Chavarría-Soley6, Alfredo B. Cuellar-Barboza7,8, José J. Martínez-Magaña9,10, Sheila T. Nagamatsu9,10, Caroline M. Nievergelt11, 12, 13, Diana L. Núñez-Ríos9,10, Vanessa K. Ota4,5, Roseann E. Peterson14, Laura G. Sloofman15, Amy M. Adams16, Elinette Albino17, Angel T. Alvarado18, Diego Andrade-Brito9, Paola Y. Arguello-Pascualli19, Cibele E. Bandeira3, Claiton H.D. Bau20,21, Cynthia M. Bulik22,23, Joseph D. Buxbaum15, Carolina Cappi15, Nadia S. Corral-Frias24, Alejo Corrales25, Fabiana Corsi-Zuelli26, James J. Crowley27, Renata B. Cupertino11, Bruna S. da Silva28, Suzannah S. De Almeida29,15,58, Juan F. De la Hoz30,31, Diego A. Forero32, Gabriel R. Fries33, Joel Gelernter9,10, Yeimy González-Giraldo34, Eugenio H. Grevet35, Dorothy E. Grice15, Adriana Hernández-Garayua9,10, John M. Hettema16, Agustín Ibáñez36,37, Iuliana Ionita-Laza38,39, María Claudia Lattig40, Yago C. Lima3, Yi-Sian Lin2, Sandra López-León41,42, Camila M. Loureiro26, Verónica Martínez-Cerdeño43, Gabriela A. Martínez-Levy44,45, Kyle Melin46, Daniel Moreno-De-Luca48, Carolina Muniz Carvalho47, Ana María Olivares49, Victor F. Oliveira3, Rafaella Ormond50, Abraham A. Palmer11,12, Alana C. Panzenhagen51,52, Maria Rita Passos-Bueno53, Qian Peng54, Eduardo Pérez-Palma55, Miguel L. Prieto56,57, Panos Roussos58, Sandra Sanchez-Roige11,12,13, Hernando Santamaría-García59, Flávio M. Shansis60,61, Rachel R. Sharp62, Eric A. Storch63, María Eduarda A. Tavares20, Grace E. Tietz2, Bianca A. Torres-Hernández46, Luciana Tovo-Rodrigues64, Pilar Trelles65, Eva M. Trujillo-ChiVacuan66,67, María M. Velásquez68, Fernando Vera-Urbina46, Georgios Voloudakis58, Talia Wegman-Ostrosky69, Jenny Zhen-Duan70, Hang Zhou9,10, Marcos L. Santoro50, Humberto Nicolini71, Elizabeth G. Atkinson2,72, Paola Giusti-Rodríguez73, Janitza L. Montalvo-Ortiz9,10,74.

References

- 1.Ferrari AJ et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 403, 2133–2161 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diversity in Genetic Studies – PGC. https://pgc.unc.edu/for-the-public/diversity-in-genetic-studies/.

- 3.Peterson RE et al. Genome-wide Association Studies in Ancestrally Diverse Populations: Opportunities, Methods, Pitfalls, and Recommendations. Cell 179, 589–603 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciochetti NP, Lugli-Moraes B, Santos da Silva B & Rovaris DL Genome-wide association studies: utility and limitations for research in physiology. J. Physiol 601, 2771–2799 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin AR et al. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet 51, 584–591 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karczewski KJ et al. Pan-UK Biobank GWAS improves discovery, analysis of genetic architecture, and resolution into ancestry-enriched effects. 2024.03.13.24303864 Preprint at 10.1101/2024.03.13.24303864 (2024). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibanez A & Zimmer ER Time to synergize mental health with brain health. Nat. Ment. Health 1, 441–443 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Linares A et al. Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals. PLOS Genet. 10, e1004572 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homburger JR et al. Genomic Insights into the Ancestry and Demographic History of South America. PLOS Genet. 11, e1005602 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter BA et al. Current evidence allows multiple models for the peopling of the Americas. Sci. Adv 4, eaat5473 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137–150 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohn R et al. Mental health in the Americas: an overview of the treatment gap. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 42, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC & Wang PS The Descriptive Epidemiology of Commonly Occurring Mental Disorders in the United States*. Annu. Rev. Public Health 29, 115–129 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viana MC & Andrade LH Lifetime Prevalence, age and gender distribution and age-of-onset of psychiatric disorders in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area, Brazil: results from the São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey. Braz. J. Psychiatry 34, 249–260 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vigo DV, Kestel D, Pendakur K, Thornicroft G & Atun R Disease burden and government spending on mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, and self-harm: cross-sectional, ecological study of health system response in the Americas. Lancet Public Health 4, e89–e96 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mental Health ATLAS 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703.

- 17.Garro-Núñez D et al. Systematic exploration of a decade of publications on psychiatric genetics in Latin America. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet 195, e32960 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polderman TJC et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet 47, 702–709 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garzón Rodríguez N et al. Exploring the relationship between admixture and genetic susceptibility to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in two Latin American cohorts. J. Hum. Genet 69, 373–380 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secolin R et al. Family-based association study for bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr. Genet 20, 126–129 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez S et al. Replication of genome-wide association study (GWAS) susceptibility loci in a Latino bipolar disorder cohort. Bipolar Disord. 18, 520–527 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-Magaña JJ et al. Genome-wide association study of psychiatric and substance use comorbidity in Mexican individuals. Sci. Rep 11, 6771 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.González-Castro TB et al. Gene-level genome-wide association analysis of suicide attempt, a preliminary study in a psychiatric Mexican population. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med 7, e983 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friligkou E et al. Gene discovery and biological insights into anxiety disorders from a large-scale multi-ancestry genome-wide association study. Nat. Genet 56, 2036–2045 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connell KS et al. Genomics yields biological and phenotypic insights into bipolar disorder. Nature 1–12 (2025) doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng X et al. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of major depression aids locus discovery, fine mapping, gene prioritization and causal inference. Nat. Genet 56, 222–233 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nievergelt CM et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 95 risk loci and provide insights into the neurobiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat. Genet 56, 792–808 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh T et al. Rare coding variants in ten genes confer substantial risk for schizophrenia. Nature 604, 509–516 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders GRB et al. Genetic diversity fuels gene discovery for tobacco and alcohol use. Nature 612, 720–724 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toikumo S et al. Multi-ancestry meta-analysis of tobacco use disorder identifies 461 potential risk genes and reveals associations with multiple health outcomes. Nat. Hum. Behav 8, 1177–1193 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Docherty AR et al. GWAS Meta-Analysis of Suicide Attempt: Identification of 12 Genome-Wide Significant Loci and Implication of Genetic Risks for Specific Health Factors. Am. J. Psychiatry 180, 723–738 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (2013).

- 33.Lord C et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 6, 1–23 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu JM et al. Rare coding variation provides insight into the genetic architecture and phenotypic context of autism. Nat. Genet 54, 1320–1331 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trost B et al. Genomic architecture of autism from comprehensive whole-genome sequence annotation. Cell 185, 4409–4427.e18 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou X et al. Integrating de novo and inherited variants in 42,607 autism cases identifies mutations in new moderate-risk genes. Nat. Genet 54, 1305–1319 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feliciano P et al. SPARK: A US Cohort of 50,000 Families to Accelerate Autism Research. Neuron 97, 488–493 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costa CIS et al. Three generation families: Analysis of de novo variants in autism. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 31, 1017–1022 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa CIS et al. Copy number variations in a Brazilian cohort with autism spectrum disorders highlight the contribution of cell adhesion genes. Clin. Genet 101, 134–141 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.da Silva Montenegro EM et al. Meta-Analyses Support Previous and Novel Autism Candidate Genes: Outcomes of an Unexplored Brazilian Cohort. Autism Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res 13, 199–206 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grove J et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet 51, 431–444 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.da Silva BS et al. An overview on neurobiology and therapeutics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Discov. Ment. Health 3, 2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayano G, Demelash S, Gizachew Y, Tsegay L & Alati R The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. J. Affect. Disord 339, 860–866 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song P et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 11, 04009 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitola ES et al. Exploring DSM-5 ADHD criteria beyond young adulthood: phenomenology, psychometric properties and prevalence in a large three-decade birth cohort. Psychol. Med 47, 744–754 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faraone SV et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 10, 1–21 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rovira P et al. Shared genetic background between children and adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol 45, 1617–1626 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Demontis D et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat. Genet 55, 198–208 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zayats T et al. Exome chip analyses in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e923–e923 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owen MJ, Sawa A & Mortensen PB Schizophrenia. The Lancet 388, 86–97 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perälä J et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64, 19–28 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi J et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature 460, 753–757 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stefansson H et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature 460, 744–747 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam M et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat. Genet 51, 1670–1678 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bigdeli TB et al. Contributions of common genetic variants to risk of schizophrenia among individuals of African and Latino ancestry. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 2455–2467 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trubetskoy V et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 604, 502–508 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mullins N et al. Genome-wide association study of more than 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides new insights into the underlying biology. Nat. Genet 53, 817–829 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maaser A et al. Exome sequencing in large, multiplex bipolar disorder families from Cuba. PLOS ONE 13, e0205895 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sul JH et al. Contribution of common and rare variants to bipolar disorder susceptibility in extended pedigrees from population isolates. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 74 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Escamilla M & Merhi C Genetic substrates of bipolar disorder risk in Latino families. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 154–167 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Errazuriz A et al. Prevalence of depressive disorder in the adult population of Latin America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Reg. Health – Am 26, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sullivan PF, Neale MC & Kendler KS Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 1552–1562 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olvera RL et al. Common genetic influences on depression, alcohol, and substance use disorders in Mexican-American families. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet 156B, 561–568 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howard DM et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci 22, 343–352 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levey DF et al. Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in >1.2 million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nat. Neurosci 24, 954–963 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peterson RE The Genetics of Major Depression: Perspectives on the State of Research and Opportunities for Precision Medicine. Psychiatr. Ann 51, 165–169 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong M-L et al. The PHF21B gene is associated with major depression and modulates the stress response. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 1015–1025 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dunn EC et al. Genome-wide association study of depressive symptoms in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J. Psychiatr. Res 99, 167–176 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Als TD et al. Depression pathophysiology, risk prediction of recurrence and comorbid psychiatric disorders using genome-wide analyses. Nat. Med 29, 1832–1844 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adams MJ et al. Trans-ancestry genome-wide study of depression identifies 697 associations implicating cell types and pharmacotherapies. Cell 0, (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Craske MG et al. Anxiety disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 3, 1–19 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Otowa T et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 1391–1399 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meier SM et al. Genetic Variants Associated With Anxiety and Stress-Related Disorders: A Genome-Wide Association Study and Mouse-Model Study. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 924–932 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levey DF et al. Reproducible Genetic Risk Loci for Anxiety: Results From ~200,000 Participants in the Million Veteran Program. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 223–232 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Strom N, I. et al. Genome-wide association study of major anxiety disorders in 122,341 European-ancestry cases identifies 58 loci and highlights GABAergic signaling. medRxiv 2024.07.03.24309466 (2024) doi: 10.1101/2024.07.03.24309466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dunn EC et al. Genome-wide association study of generalized anxiety symptoms in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet 174, 132–143 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stein MB et al. Genetic risk variants for social anxiety. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet 174, 120–131 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hettema JM et al. Genome-wide association study of shared liability to anxiety disorders in Army STARRS. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet 183, 197–207 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT & Kessler RC The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 15, 53–63 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wetterneck CT et al. Latinos with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Mental healthcare utilization and inclusion in clinical trials. J. Obsessive-Compuls. Relat. Disord 1, 85–97 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blanco-Vieira T et al. The genetic epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 1–14 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cappi C et al. Whole-exome sequencing in obsessive-compulsive disorder identifies rare mutations in immunological and neurodevelopmental pathways. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e764 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cappi C et al. De Novo Damaging DNA Coding Mutations Are Associated With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Overlap With Tourette’s Disorder and Autism. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 1035–1044 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Halvorsen M et al. Exome sequencing in obsessive-compulsive disorder reveals a burden of rare damaging coding variants. Nat. Neurosci 24, 1071–1076 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strom NI et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 obsessive-compulsive disorder associated loci. 2024.03.13.24304161 Preprint at 10.1101/2024.03.13.24304161 (2024). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crowley JJ et al. Latin American Trans-ancestry INitiative for OCD genomics (LATINO): Study protocol. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet 195, e32962 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koenen KC et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med 47, 2260–2274 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schein J et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Curr. Med. Res. Opin 37, 2151–2161 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Duncan LE, Cooper BN & Shen H Robust Findings From 25 Years of PTSD Genetics Research. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 20, 115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Duncan LE et al. Largest GWAS of PTSD (N=20 070) yields genetic overlap with schizophrenia and sex differences in heritability. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 666–673 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maihofer AX et al. Enhancing Discovery of Genetic Variants for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Through Integration of Quantitative Phenotypes and Trauma Exposure Information. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 626–636 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nievergelt CM et al. International meta-analysis of PTSD genome-wide association studies identifies sex- and ancestry-specific genetic risk loci. Nat. Commun 10, 4558 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stein MB et al. Genome-wide association analyses of post-traumatic stress disorder and its symptom subdomains in the Million Veteran Program. Nat. Genet 53, 174–184 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Melroy-Greif WE, Wilhelmsen KC, Yehuda R & Ehlers CL Genome-wide association study of post-traumatic stress disorder in two high-risk populations. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. Off. J. Int. Soc. Twin Stud 20, 197–207 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bugiga AVG et al. Interaction between PTSD-PRS and trauma affects PTSD likelihood in women victims of sexual assault. Braz. J. Psychiatry 0, 1–27 (2022).34378745 [Google Scholar]

- 96.MVP Home | Veterans Affairs. https://www.mvp.va.gov/pwa/. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kessler RC et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 904–914 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thornton LM, Mazzeo SE & Bulik CM The Heritability of Eating Disorders: Methods and Current Findings. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci 6, 141 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dinkler L et al. Etiology of the Broad Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Phenotype in Swedish Twins Aged 6 to 12 Years. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 260–269 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]