Abstract

Background:

The majority of people in the United States do not achieve recommended levels of physical activity. Even small, daily increases can have health benefits. Wearable devices paired with social incentives increased daily steps in pilot studies but have not been tested for long-term effectiveness in community settings. This paper describes the study design and baseline participant characteristics of a trial testing these approaches to increase physical activity among families in the Philadelphia area.

Methods:

The trial, called STEP Together, is a Hybrid Type 1 effectiveness-implementation study. Participants enroll on family teams of 2–10 people, including at least one person 60 years old or older. Each participant receives a Fitbit device, establishes a baseline daily step count, and selects a daily step goal 1500 to 3000 steps greater than their baseline. Family teams are stratified based on family size and randomized to Control, Social Incentive Gamification, or Social Goals through Incentives to Charity. Participation is 18-months: a 12-month intervention and 6-month follow up.

Results:

779 participants on 285 family teams were randomized. Recruitment was more difficult than anticipated due to the COVID-19 pandemic and higher-than expected numbers of participants who were already physically active and therefore ineligible. Changes to the eligibility criteria that did not impact the underlying intent or conceptual basis for the trial improved recruitment feasibility.

Conclusion:

The results from this study will contribute to the growing body of evidence about scalable, effective strategies to motivate individuals and families to increase their daily physical activity.

Clinical trial registration number: NCT04942535

Keywords: Physical activity, Older adults, Social incentives, Community-based research, Family, Health behavior

1. Introduction

Regular physical activity (PA) is associated with numerous health benefits including lower risk of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, cognitive decline and dementia, and depression [1–7]. Research suggests that there is a dose-response relationship between PA and health, such that even small increases in PA can reduce risk of chronic disease and all-cause mortality [8–15]. However, fewer than half of adults in the United States (US) achieve the recommended amount of weekly PA (150–300 min of moderate-intensity per week) [16]. Women, people living in poverty, and people with lower education are less likely to meet the recommended level of PA [16,17]. The proportion of adults meeting recommended levels of physical activity declines with age [16], despite the importance of physical activity to support healthy aging and prevent all-cause mortality [2,3,18,19].

Evidence shows that insufficiently active individuals can benefit from even small increases in daily PA [14,20,21]. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed progressive benefits of increasing PA up to 8000–10,000 steps/day for adults younger than 60 and up to 6000–8000 steps/day for older adults [7]. Among older adults, there is evidence that achieving even 15 min of moderate-to-vigorous daily physical activity lowers risk of all-cause mortality [22]. Wearable devices that track daily PA can help to increase users’ daily activity, and may be linked to small improvements in health [23–28]. However, there is concern that changes to PA motivated by wearable devices may be short-term, since many users stop using the devices over time [29]. Multicomponent approaches that combine wearable device feedback with other behavior change strategies show promise in overcoming the limitations of device-only interventions [27,28]. Social incentive-based strategies that use insights from behavioral economics have been shown to motivate behavior change, including increased PA, when paired with feedback from wearable devices [30–33].

The STEP Together study is a Hybrid Type 1 effectiveness-implementation study [34] testing the effectiveness of wearable devices and social incentive strategies to increase PA. STEP Together involves the adaptation of two successful social incentive strategies to increase PA – gamification [30] and donations to charity on the participants’ behalf [33] – for implementation among families in the Philadelphia region. Increasing daily PA through walking is an evidence-based, low-cost intervention to improve health. Walking does not require special equipment or facilities, so it can reach people across the economic spectrum. If shown to be successful in a large-scale, community-based setting, social incentive strategies paired with wearable devices could be widely implemented to promote increased PA.

2. Methods

STEP Together is a three-phase study. In Phase 1, the study team sought community input about the proposed study design using a series of Community Engagement Studios [35,36]. Feedback from these sessions was used to adapt and refine the study design prior to implementation [36]. Phase 2 of STEP Together is an implementation-effectiveness trial, which is currently underway. Phase 3 will be dissemination, translation and scale-up of the successful intervention strategy or strategies based on the results of Phase 2. This paper describes the study design and participant baseline characteristics for the trial being conducted in Phase 2. Phase 2 started in September 2021, when some restrictions on in-person activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic were still in place.

During Phase 2, additional modifications were made to address recruitment challenges due to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic. Appendix A provides an overview of key aspects of the study design prior to implementation (at the conclusion of Phase 1) and the current/final design. The methods described below reflect the final study design of Phase 2 unless otherwise noted. The adaptations do not substantively change the intent or conceptual basis for the trial.

2.1. Recruitment

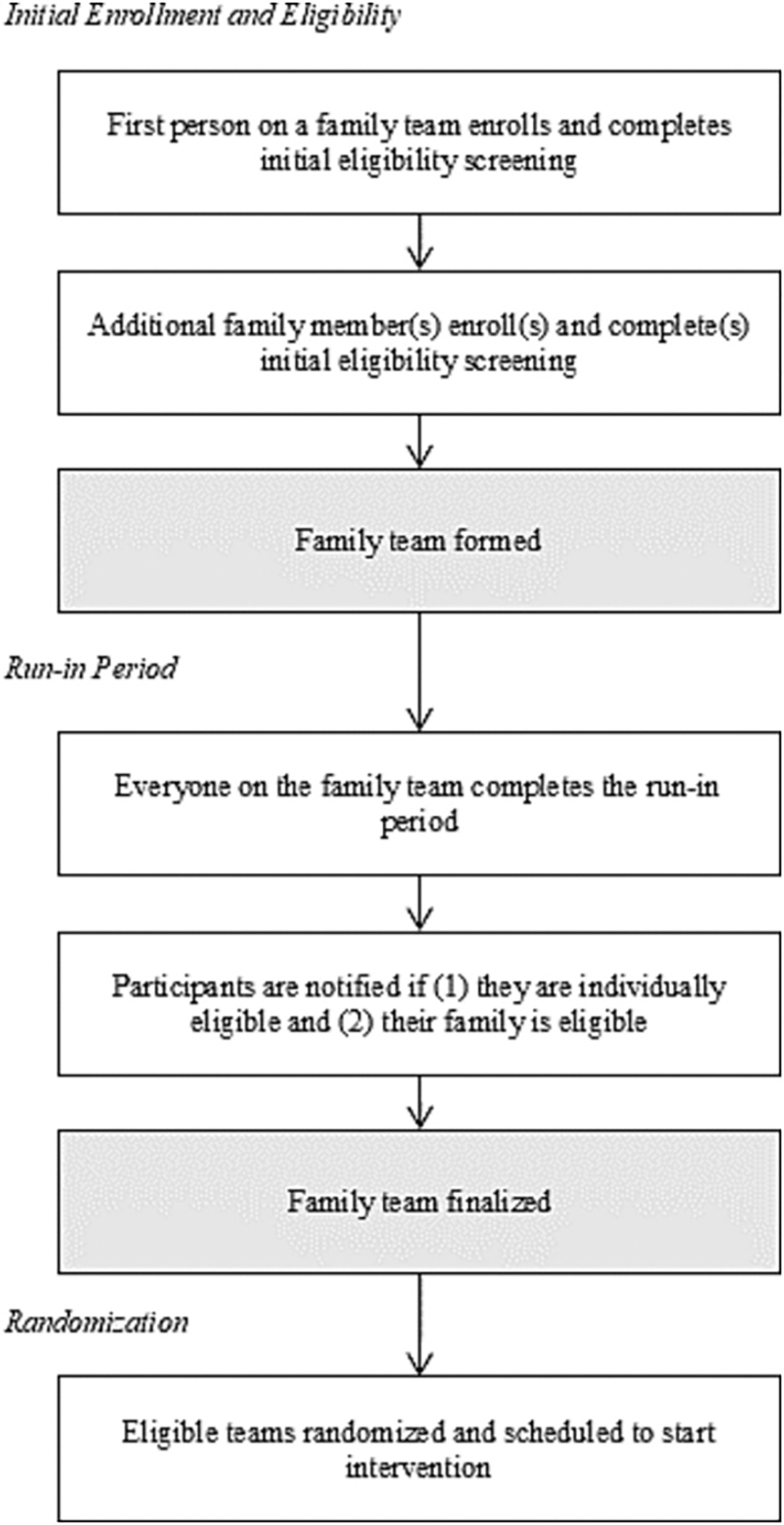

Participants in the STEP Together study enrolled as part of a family team. Initial recruitment methods included social media posts, newspaper ads, and in-person recruitment at community sites. Due to slow enrollment, the team pivoted to primary recruitment via messages sent to potentially eligible Penn Medicine primary care patients. The first person from a family to enroll was designated the “Team Captain.” After the Team Captain completed the eligibility screening and informed consent, they were asked to provide information about their family team members, who were then invited to enroll. All participants began the enrollment process by creating an account on Way to Health, the study platform used to manage eligibility screening, consent, surveys, and activity tracking and feedback [37]. Fig. 1 provides a general overview of the enrollment process for individuals and family teams. Fig. 2 provides a general overview of the study flow.

Fig. 1.

STEP Together Individual and Family Enrollment Process.

Fig. 2.

STEP Together Study Flow Diagram.

STEP Together is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04942535). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania approved the study. All participants provided informed consent or child assent and parental consent.

2.2. Enrollment and eligibility

Eligibility to participate in STEP Together was assessed in two stages, which are summarized in Table 1. Potential participants completed an individual screening and were eligible to move forward if they could read and speak English, had a smartphone or equivalent digital device, lived in the 9-county Philadelphia area, and were 14 years old or older. Although the study was conducted remotely, geographic eligibility criteria were established to ensure that all members of a family team lived within the same region and to increase recognition of the institution conducting the study.

Table 1.

STEP Together Eligibility.

| Initial Eligibility | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Individual | • Read and speak English, • have a smartphone or tablet, • live in the Philadelphia area (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia County in Pennsylvania; Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester County in New Jersey; and New Castle County in Delaware), • 14 years old or older, • able to provide informed consent or parental consent and child assent, and • not already very physically active (self-reported). |

| Team | • 2–10 people, • at least one person 60 years old or older, • family or close-friend relationship with at least one other person on the team (typically the Team Captain). |

| Run-In Period Eligibility | |

| Individual | • Baseline step count of 7500 or lower during the second week of the run-in, • baseline step count of 7500 or lower after extending the run-in period, or • baseline step count of 7600–8300 after extending the run-in period if their family team is eligible. |

| Team | • At least two people on the team are individually eligible, including one person 60 years old or older. |

| Participants with a baseline step count of 7500 or lower who are on an ineligible family team after the run-in period can invite other people to join their family team. | |

Individuals were ineligible if they were already participating in another PA study, could not safely or feasibly participate in an 18-month PA study, were unable to operate a Fitbit device, or were unwilling or unable to wear a Fitbit and receive daily text messages during the study. Individuals who reported high levels of physical activity were excluded early in the screening process.

Each family team also had to meet team eligibility criteria. Teams had to have 2–10 people and each team had to include at least one person 60 years old or older. Every individual on the team had to have a family or close-friend relationship with at least one other person on the team. “Family” was defined as first-degree relatives, second-degree relatives, family by marriage, family by adoption, and long-term or common law partners. Close friends were defined as friends who had known each other for two or more years, communicated or saw each other at least once a week, and were willing to join a “family” team together.

2.2.1. Run-in period

After a family team enrolled and was deemed eligible to move forward, everyone on the family team received a Fitbit Inspire 2 or Fitbit Inspire 3 device (when it became available). Participants were instructed to connect their Fitbits to the study after they completed the baseline surveys (described below). They were told to wear the Fitbit for two weeks without intentionally changing their activity patterns. The “run-in” period was designed to troubleshoot technical issues, familiarize participants with the Fitbit device, exclude people who were already so active that they would not benefit from the trial, and establish participants’ baseline step counts [30]. After participants recorded two weeks of step data, their daily step count for the second week was averaged to establish an initial baseline. Any day with less than 1000 steps recorded was excluded from the average since it is unlikely to represent actual daily activity [38,39]. Participants needed at least 4 days of valid step data in order to calculate a baseline [30,40–42]. Participants who did not link their Fitbits to the Way to Health study platform or did not achieve a minimum of 1000 daily steps for at least 4 days within a consecutive 7-day period were deemed ineligible. The run-in period was extended for participants who needed to troubleshoot a device issue or indicated that their PA during the run-in was atypical.

Participants with an average daily step count between 1000 and 7500 steps during the last week of the run-in were eligible. Participants with a baseline of 8400 steps or higher during the entire 14-day data collection period were ineligible. Participants with a baseline between 7600 and 8300 steps during the entire 14-day data collection period were eligible for an extension to their run-in period. After the extension, participants with an average daily step count up to 7500 steps were eligible, participants with an average daily step count of 7600–8300 steps were eligible if their family team was eligible, and participants with an average daily step count of 8400 or higher were ineligible. Average daily step count during the last week of the run-in period was used to establish participants’ baseline physical activity.

When all the members of a family team completed the run-in period, participants were notified about their individual eligibility and their family team’s eligibility. Family teams were eligible after the run-in period as long as at least two people from the team, including someone 60 years old or older, were individually eligible. Eligible participants who were not on an eligible family team become ineligible if they did not invite another eligible family member or friend to join their team.

2.2.2. Goal selection

All eligible members of the family team selected a step goal to strive for during the study. Participants selected a goal between 1500 and 3000 steps higher than their baseline daily step count, based on a procedure shown to be effective in increasing participants’ daily step count in a prior study [41]. For inactive individuals, an increase in 1500 to 3000 steps over baseline represents a meaningful – and sustainable – increase in daily physical activity [43,44].

During the study, participants are permitted to contact the study team to update their goal as long as the updated goal is within these parameters or the alternative minimum goal described in Appendix A. There are no limitations to how often participants can change their goals.

2.2.3. Randomization

After completing goal selection, the family team was randomly assigned to one of the three study arms: Control, Social Incentive Gamification (“Gamification”), Social Goals through Incentives to Charity (“Charity”). Teams were stratified based on family size (2-person, 3-person, 4-person, and 5-or-more-person teams) and randomized using a table produced by the study analyst. After a team was randomized, the team was scheduled to start the intervention the following Monday. They received a message at the time of randomization explaining their arm assignment and intervention start date. The investigators are blinded to arm assignment.

2.3. Intervention design

All participants in the study are enrolled for 18 months, consisting of a 12-month intervention period and 6-month follow up. They are asked to wear the Fitbit day and night and to sync their Fitbit device with the Fitbit app every night before going to sleep. Each participant receives daily feedback by email or text message. These messages are automated using the Way to Health platform, which pulls Fitbit data every night to determine if a participant met their step goal. All key study content is delivered directly to participants via text or email and participants are informed that they can view their daily steps in the Fitbit app, as well as their current and past daily step achievement. They also have access to a dashboard on the Way to Health study platform that includes instructions, their daily step goal, Frequently Asked Questions, the study Informed Consent form, and study team contact information. Intervention arm participants can view additional information about their study arm in their dashboard.

2.3.1. Control arm

Participants in the control arm receive a daily text message informing them if they met their step goal on the prior day. Participants in the control arm receive daily feedback for the duration of the intervention and follow up.

2.3.2. Gamification arm

Participants in the Gamification arm are entered into a game developed using concepts from behavioral science and tested in a prior pilot study [30]. Every participant in the gamification arm signs a pre-commitment pledge agreeing to strive to meet their daily step goal [45]. Every Monday, each family team receives 70 points (10 points for each day of the week). Each day, a family member is selected at random to represent the team as the “family representative.” If the family representative meets their goal on the day they are selected, the family keeps their points. If the family representative does not meet their goal, the family loses 10 points. This design leverages loss aversion, which has been shown to be effective in encouraging behavior change [46,47]. The team is not told who is selected as the day’s family representative until the following day.

Participants in the Gamification arm receive a daily text message with a motivational message informing them if they met their goal the previous day. The person who was selected as the family representative the previous day also gets an update on the team’s points for the week.

All families start the study at the silver level. They move up or down the following levels: blue (lowest), bronze, silver, gold, and platinum (highest). If the family team has less than 40 points at the end of the week, the family drops down one level. If they have 40 or more points, they advance a level. Every 8 weeks, families that are in the blue or bronze level are moved to silver to allow for another “fresh start” [48]. Each Monday, participants in the Gamification intervention receive an email with information about their family’s level in the game (whether they moved up or down a level or stayed at the lowest or highest level).

At the end of the 12-month intervention period, each participant on a team that finishes the game in the platinum or gold level receives a small trophy to recognize their achievement. During the 6-month follow up period, participants in the Gamification arm receive a daily text message stating whether they achieved their step goal on the prior day.

2.3.3. Charity arm

The charity intervention is based on a previous pilot project that found that donations to charity on a participant’s behalf were effective for increasing daily PA among older adults, and as effective as a direct financial incentive payments to participants [33]. When a family team is randomized to the Charity arm, they are informed that their team has the opportunity to donate $20 each week to a charity of their choice. The family team’s Team Captain is responsible for selecting the charity that receives the family’s donations. The Team Captains can select from a list of pre-approved charities or select one of their choosing if it is a registered 501(c)(3) in good standing.

A family representative is randomly selected each day. They are informed the following day if they were selected as the family representative. If the family representative’s step goal is achieved, the family receives credit for meeting their goal. If it is not met, the entire family does not get credit. If the family representatives meet their goals on at least 4 of 7 days of the week (Monday through Sunday), $20 is donated to charity on behalf of the family team. Participants in the Charity arm receive a daily text message with motivational messaging informing them if they met their goal the previous day. The person who was selected as the family representative the previous day also receives an update on the team’s progress towards a charity donation for the week.

Participants receive an email with information about whether their family earned a donation to charity every week of the intervention. Charity payments are made monthly, and participants receive a separate email from the study team when each charity payment is made.

During the 6-month follow up period, participants in the Charity arm receive a daily text message stating whether they achieved their step goal on the prior day.

2.3.4. Outcome measures

The primary outcome variable is change in mean daily steps from baseline to the end of the 12-month intervention period. Each participant’s baseline is established during the run-in period, as described above. A participant’s mean daily step count for the 12-month intervention period is calculated by averaging their daily steps (364 data points for each participant) during this time.

Additional outcome variables include: change in mean daily steps from baseline to the end of the first 6 months of the intervention period (collected through the Fitbit), change in mean daily minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA, defined as greater than or equal to 100 steps per minute [44]) from baseline to the end of the 12-month intervention period, and change in total mean daily steps and minutes of MVPA from baseline to the end of the 6-month follow up-period. Exploratory outcomes include the difference between study arms in the proportion of weeks that PA guidelines (150 min per week of MVPA) were achieved during the 12-month intervention and from baseline to the end of the 6-month follow up (18 months total).

2.3.5. Background characteristics, psychosocial variables, and process measures

Participants complete surveys at baseline and 6, 12, and 18 months after beginning the intervention. All surveys are completed in Way to Health. The psychosocial variables measured in the surveys are included as secondary and/or exploratory outcomes and possible mediators of change. They include these established and widely-used measures: Medical Outcomes Social Support Study (MOS) [49], Health related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) [50], International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form [51], Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) short form [52,53], self-efficacy for exercise behaviors [54], Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Assessment [55], and the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ2) [56]. Participants also complete an Adverse Events (AE) survey at 6, 12, and 18 months to monitor AEs, whether or not they were directly reported to the study team at the time they occurred. At 18 months, participants complete an end-of-study survey to assess general reactions and experiences with the Fitbit device, Way to Health research platform, and intervention. Responses will be examined to determine how they align with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [57,58]. Table 2 describes the data to be collected, survey instruments, and administration timeline.

Table 2.

STEP Together measures and data collection schedule.

| Categories and constructs | Measure | Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | 18 Months | End of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Effectiveness outcomes | ||||||

| Steps | Fitbit data | Daily | Daily | Daily | Daily | |

| Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity MVPA | Fitbit data | Daily | Daily | Daily | Daily | |

| Demographics and medical history | ||||||

| Baseline demographics | Baseline survey | X | ||||

| Medical History | Medical History survey | X | X | X | ||

| Survey measures of physical activity | ||||||

| Regular weekly physical activity | International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form [51] | X | X | X | X | |

| Non-“step” physical activity survey | Non-“step” physical activity survey | X | X | X | X | |

| Enjoyment of physical activity | Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) short form [53] | X | X | X | ||

| Exercise self-efficacy | Self-efficacy for exercise behaviors [54] | X | X | X | ||

| Psychosocial measures | ||||||

| Health-related quality of life | EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS [50] | X | X | X | X | |

| Social support | Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey [49] | X | X | X | ||

| Sleep | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Assessment [55] | X | X | X | ||

| Mood | Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) [56,68] | X | X | X | ||

| Implementation and process measures | ||||||

| Adverse events survey | Adverse events survey | X | X | X | ||

| Reactions to intervention strategies, wearable device, and research technology platform | Exit survey, adapted from several sources [69–74] | X | ||||

| Factors contributing to success or failure to increase activity | Semi-structured interviews with a subset of higher and lower performing participants | X | ||||

2.3.6. Qualitative evaluation of high- and low-performing participants

A sub-set of participants (30 participants per arm, 90 total) will be interviewed after finishing the study to learn more about why some participants increased PA and others did not. High-performing and low-performing participants will be selected. Interview topics include: motivations for participating, barriers and facilitators to increasing PA during the study, and how the intervention helped or hindered their goal attainment [59]. The interviews will be professionally transcribed and content-analyzed using a modified grounded theory approach [60].

2.4. Statistical design and analysis

Data summaries will be produced to assess data quality, data distribution, and randomization success. Primary analyses will be performed using an intent-to-treat approach. Multiple imputation will be used for step values that are missing or less than 1000 steps and for missing MVPA values [30,31,40,41,61,62]. Days with steps less than 1000 are treated as missing since it may indicate that data are not being accurately captured [38,61]. Five sets of imputations will be performed and results will be combined using Rubin’s standard rules [63]. Sensitivity analyses will be performed to assess the robustness of the findings using collected data with and without step values of less than 1000 steps.

The primary analysis will fit linear mixed effect regression models to evaluate changes in PA outcome measures (primary and secondary outcomes) adjusting for each participant’s baseline measure, time using calendar month fixed effects, participant random effects, accounting for repeated measures, and clustering at the level of the family; this approach has been used in prior work [30,47,64,65]. Secondary analyses will fit linear mixed mixed-effect regression models adjusted for other variables of interest. Exploratory analyses will fit logistic mixed-effect regression models to evaluate the proportion of weeks that guidelines for PA were achieved. Descriptive and bivariate analyses will be used to analyze implementation and process measures.

2.5. Power and sample size

The threshold for powering statistical significance is 1000 steps with a standard deviation of 2200 steps and an intra-cluster correlation coefficient of 0.24. This is consistent with similar studies [42] and reflects the dose-response relationship between increased physical activity and improved health [8–15]. One thousands steps is about half a mile or 10 min of MVPA [44].

The planned accrual target of 225 families (about 675 participants with an average of 3 persons per family) across the 3 arms ensures at least 90 % power to detect a 1000-step difference assuming a conservative Bonferroni-Holm adjustment of the type I error rate with a 2-sided alpha of 0.017 to adjust for up to 3 comparisons, clustering at the family level, and a 12 % dropout rate [66].

2.6. Additional measures

2.6.1. Cost-effectiveness analysis

We will compare incremental costs and effects of increased physical activity using data collected during the trial. The analyses will compare the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios that show the difference in costs between intervention and control arms divided by the difference in outcomes (e.g. change in daily step counts) of intervention arms over 12 months. The analysis will be from a payer perspective and will include costs that would be incurred by the payers of the program. Measured costs will include intervention costs such as incentive payments, cost of technology platform, and devices utilized for participant monitoring and tracking. Costs will also include personnel costs for time spent on monitoring and tracking of participants and coordinating and overseeing the intervention activities. The analysis will use differences between each intervention and control in measures of physical activity (steps and minutes of MVPA), and health-related quality of life measured by the EQ-5D [50] as the outcome measures.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment results

Recruitment began in September 2021 and was completed in March 2024. Fig. 3 shows the study CONSORT diagram through completion of enrollment and randomization. In total, 2519 people created online accounts. Of these individuals, 2303 completed the initial eligibility screening and provided informed consent or child assent and parental consent and 1383 met the inclusion criteria and completed the run-in period. After the run-in period, 454 people were ineligible because they were too active. The accrual target was increased from 675 to 750 for two reasons: 1) many family teams had received their Fitbits and were already in the run-in period when the initial target sample size was achieved and 2) the study team noticed that dropouts and unexpected periods of missing data would result in some family teams not completing the study as ‘teams’ of at least two people. When the updated target of 750 participants was met, family teams that were in the run-in period were allowed to complete the run-in and were randomized, if eligible. After the run-in period, 779 participants (285 families) were eligible and randomized.

Fig. 3.

STEP Together CONSORT Diagram.

3.2. Baseline characteristics of randomized participants and families

Table 3 describes participant demographic characteristics at baseline. Of the 285 family teams that were randomized, 95 family teams were randomized to each arm (258 participants in Arm A, 261 participants in Arm B, and 260 in Arm C). Participants’ ages average 58.1 years (SD = 16.8). Three quarters of the participants are female (N = 581, 74.6 %), similar to other physical activity studies [30,33,41,62] and health behavior clinical trials in general [67]. About half of participants are non-Hispanic White (N = 415, 53.3 %), 36.3 % are non-Hispanic Black (N = 283), and the remaining participants are Asian (N = 38, 4.9 %), Hispanic (N = 34, 4.4 %), or another race/ethnicity (N = 9, 1.2 %). The average number of participants on a family team is 3.2 (SD = 1.5, range = 2–9). Randomized participants had an average baseline step count of 5371.4 (SD = 1609.6, range = 1300 to 8300).

Table 3.

Baseline participant characteristics by intervention arm.

| Characteristics | Participant N = 779, Teams N = 285 | Arm A N = 258, Teams N = 95 | Arm B N = 261, Teams N = 95 | Arm C N = 260, Teams N = 95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 58.1 (16.8) | 56.2 (17.6) | 58.9 (16.4) | 59.3 (16.1) |

| Gender, n (col %) | ||||

| Male | 198 (25.4) | 64 (24.8) | 69 (26.4) | 65 (25.0) |

| Female | 581 (74.6) | 194 (75.2) | 192 (73.6) | 195 (75.0) |

| *Race/Ethnicity, n (col %) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 415 (53.3) | 123 (47.7) | 149 (57.1) | 143 (55.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 283 (36.3) | 99 (38.4) | 72 (27.6) | 112 (43.1) |

| Hispanic | 34 (4.4) | 10 (3.9) | 22 (8.4) | 2 (0.8) |

| Asian | 38 (4.9) | 22 (8.5) | 13 (5.0) | 3 (1.2) |

| Other | 9 (1.2) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0 |

| ***Household income, n (col %) | ||||

| $39,999 or less | 106 (16.8) | 26 (12.4) | 48 (22.7) | 32 (15.2) |

| $40,000 to $99,999 | 297 (47.1) | 102 (48.8) | 93 (44.1) | 102 (48.6) |

| $100,000 or higher | 227 (36.0) | 81 (38.8) | 70 (33.2) | 76 (36.2) |

| Medical History and Health Behaviors BMI in category, n (col %) | ||||

| Normal (< 25) | 170 (21.8) | 56 (21.7) | 67 (25.7) | 47 (18.1) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 245 (31.5) | 85 (32.9) | 79 (30.3) | 81 (31.2) |

| Obese (30+) | 364 (46.7) | 117 (45.3) | 115 (44.1) | 132 (50.8) |

| Hypertension, n (col %) | 329 (42.2) | 102 (39.5) | 107 (41.0) | 120 (46.2) |

| Diabetes, n (col %) | 121 (15.5) | 39 (15.1) | 35 (13.4) | 47 (18.1) |

| ** Ever smoked cigarettes, n (col %) | 216 (27.7) | 59 (22.9) | 71 (27.2) | 86 (33.1) |

| Step count at baseline | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5371.4 (1609.6) | 5415.1 (1578.2) | 5235.2 (1650.0) | 5464.6 (1596.3) |

| Range (median) | 1300 to 8300 (5600) | 1300 to 8200 (5600) | 1600 to 8300 (5400) | 1700 to 8300 (5700) |

| Family team size | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.6) | 3.2 (1.6) |

| Range (median) | 2 to 9 (3) | 2 to 7 (3) | 2 to 9 (3) | 2 to 9 (3) |

The difference of distribution between arms is significant p < 0.0001.

The difference of distribution between arms is significant p < 0.05.

There are 149 (19.1 %) subjects having missing values.

There are statistically significant differences in race/ethnicity and cigarette smoking status between arms. Arm A has a higher proportion of Asian participants (8.5 %) and Arm B has fewer Black participants than the other arms (27.6 % vs 38.4 % and 43.1 %). Arm C has the highest proportion of participants who have ever smoked cigarettes (33.1 %) and Arm A has the lowest (22.9 %).

4. Discussion

The STEP Together study has an ambitious, complex design and the research team encountered significant recruitment challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A large number of potential participants were ineligible because they were already very physically active. The eligibility screener included questions intended to discourage active people from moving ahead with enrollment, but many who were already very active completed the run-in period. In response to these issues and feedback from potential participants, eligibility was expanded to allow close friends on the family team, the minimum age of the “older adult” on the team was lowered to 60 years, and the study region was expanded to allow for participants living in counties surrounding Philadelphia. After implementing these changes and focusing recruitment efforts on potentially eligible Penn Medicine primary care patients, recruitment and randomization of 779 participants was achieved.

Challenges during the early stages of the trial include missing or delayed daily step data, and some participants being unresponsive to study team outreach. A participant is considered lost to follow-up and removed from the study (passive withdrawal) after 60 or more consecutive days of missing data unless they are actively communicating with the study team to resolve the issue. Up to the time that this write-up was prepared (September 2024), a total of 64 participants, or 8.2 %, withdrew or were removed from the study, which is less than the projected 12 % dropout rate used in the power calculations.

4.1. Strengths

The STEP Together study has several important strengths. STEP Together collects continuous physical activity data using Fitbit wearable devices. This objective measure of daily steps and MVPA prevents over-or under-reporting of PA by study participants. Another key strength of the STEP Together study is the length of intervention and data collection period: a 12-month intervention testing two intervention strategies against control and 6-month follow up period. This 18-month duration is significantly longer than in most published studies testing incentive strategies to increase PA. As an implementation trial, STEP Together aims to yield findings that can be used to both increase and sustain higher activity levels. The study’s entirely remote design may facilitate uptake of the intervention strategies into real-world contexts.

4.2. Limitations

In addition to important strengths, the STEP Together study has some limitations. Enrollment efforts identified more people who were already very physically active and thus ineligible. Another limitation includes missing data from participants who did not respond after repeated contact attempts over more than a month, though the dropout rate was only 8.2 %.

5. Conclusion

Despite strong and growing evidence that PA promotes health and prevents common chronic diseases, more than half of the adults in the US do not meet recommended levels of PA. Interventions that incorporate wearable devices with behavioral science-informed social incentive strategies have the potential to be scalable, sustainable, and effective. STEP Together is a large, community-based trial testing Gamification and Charity donations as strategies to promote increased daily step count among families in the Philadelphia area. The final randomized participants will complete the study in late 2025. The findings will contribute to the growing body of evidence about low-cost strategies to motivate individuals and families to engage in more active lifestyles.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2025.107909.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Claudia Caponi for her assistance with manuscript preparation and Mitesh Patel for his contribution to study development. We acknowledge the contributions of Research Coordinators Sena Park and Emma Adelia Soliva and Research Assistants Caleb Middlebrook, Claire Baptiste, Jeremy Lee, Jennifer Kang, Jennifer Deng, Holly Shimabukuro, Francis Eddy Harvey, and Julie Nemerson for their work on the study.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL152430. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Krista Scheffey: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Investigation. Joshua Aronson: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation. Yolande Goncalves: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. S. Ryan Greysen: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Ashley Iwu: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Pui L. Kwong: Formal analysis, Data curation. Freya Nezir: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Dylan Small: Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Karen Glanz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Matthews CE, Moore SC, Arem H, Cook MB, Trabert B, Hakansson N, et al. , Amount and intensity of leisure-time physical activity and lower Cancer risk, J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (7) (2020) 686–697, 10.1200/JCO.19.02407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Erickson KI, Donofry SD, Sewell KR, Brown BM, Stillman CM, Cognitive aging and the promise of physical activity, Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18 (2022) 417–442, 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072720-014213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Raichlen DA, Aslan DH, Sayre MK, Bharadwaj PK, Ally M, Maltagliati S, et al. , Sedentary behavior and incident dementia among older adults, JAMA 330 (10) (2023) 934–940, 10.1001/jama.2023.15231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lopez-Bueno R, Ahmadi M, Stamatakis E, Yang L, Del Pozo Cruz B, Prospective associations of different combinations of aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity with all-cause, cardiovascular, and Cancer mortality, JAMA Intern. Med. 183 (9) (2023) 982–990, 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pearce M, Garcia L, Abbas A, Strain T, Schuch FB, Golubic R, et al. , Association between physical activity and risk of depression: a systematic review and Meta-analysis, JAMA Psychiatry 79 (6) (2022) 550–559, 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Del Pozo Cruz B, Ahmadi MN, Lee IM, Stamatakis E, Prospective associations of daily step counts and intensity with Cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality and all-cause mortality, JAMA Intern. Med. 182 (11) (2022) 1139–1148, 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Paluch AE, Bajpai S, Bassett DR, Carnethon MR, Ekelund U, Evenson KR, et al. , Steps for health, daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts, Lancet Public Health 7 (3) (2022) e219–e228, 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00302-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Garcia L, Pearce M, Abbas A, Mok A, Strain T, Ali S, et al. , Non-occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality outcomes: a dose-response meta-analysis of large prospective studies, Br. J. Sports Med. 57 (15) (2023) 979–989, 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stens NA, Bakker EA, Manas A, Buffart LM, Ortega FB, Lee DC, et al. , Relationship of daily step counts to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82 (15) (2023) 1483–1494, 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Kamada M, Bassett DR, Matthews CE, Buring JE, Association of Step Volume and Intensity with all-Cause Mortality in older women, JAMA, Intern. Med. 179 (8) (2019) 1105–1112, 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Inoue K, Tsugawa Y, Mayeda ER, Ritz B, Association of Daily Step Patterns with Mortality in US adults, JAMA Netw. Open 6 (3) (2023) e235174, 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liew SJ, Petrunoff NA, Neelakantan N, van Dam RM, Muller-Riemenschneider F, Device-measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in relation to cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: systematic review and Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies, AJPM Focus 2 (1) (2023) 100054, 10.1016/j.focus.2022.100054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Saint-Maurice PF, Troiano RP, Bassett DR Jr., Graubard BI, Carlson SA, Shiroma EJ, et al. , Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity with Mortality among US adults, JAMA 323 (12) (2020) 1151–1160, 10.1001/jama.2020.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kraus WE, Janz KF, Powell KE, Campbell WW, Jakicic JM, Troiano RP, et al. , Physical activity guidelines advisory, daily step counts for measuring physical activity exposure and its relation to health, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51 (6) (2019) 1206–1212, 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Master H, Annis J, Huang S, Beckman JA, Ratsimbazafy F, Marginean K, et al. , Association of step counts over time with the risk of chronic disease in the all of us research program, Nat. Med. 28 (11) (2022) 2301–2308, 10.1038/s41591-022-02012-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Elgaddal N, Kramarow EA, Reuben CA, National Center for Health Statistics (U. S.), Physical activity among adults aged 18 and over : United States, in: NCHS data brief, (443,:1–8.), 2020. https://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo195929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tran L, Tran P, Tran L, A cross-sectional examination of sociodemographic factors associated with meeting physical activity recommendations in overweight and obese US adults, Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 14 (1) (2020) 91–98, 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cunningham C, O’Sullivan R, Caserotti P, Tully MA, Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: a systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses, Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30 (5) (2020) 816–827, 10.1111/sms.13616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Izquierdo M, Duque G, Morley JE, Physical activity guidelines for older people: knowledge gaps and future directions, The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2 (6) (2021) e380–e383, 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hall KS, Hyde ET, Bassett DR, Carlson SA, Carnethon MR, Ekelund U, et al. , Systematic review of the prospective association of daily step counts with risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and dysglycemia, Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17 (1) (2020) 78, 10.1186/s12966-020-00978-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Paluch AE, Gabriel KP, Fulton JE, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. , Steps per day and all-cause mortality in middle-aged adults in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study, JAMA Netw. Open 4 (9) (2021) e2124516, 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hupin D, Roche F, Gremeaux V, Chatard JC, Oriol M, Gaspoz JM, et al. , Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged ≥60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Br. J. Sports Med. 49 (19) (2015) 1262–1267, 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ferguson T, Olds T, Curtis R, Blake H, Crozier AJ, Dankiw K, et al. , Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, The Lancet Digital Health 4 (8) (2022) e615–e626, 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Heizmann AN, Chapelle C, Laporte S, Roche F, Hupin D, Le Hello C, Impact of wearable device-based interventions with feedback for increasing daily walking activity and physical capacities in cardiovascular patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, BMJ Open 13 (7) (2023) e069966, 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Franssen WMA, Franssen GHLM, Spaas J, Solmi F, Eijnde BO, Can consumer wearable activity tracker-based interventions improve physical activity and cardiometabolic health in patients with chronic diseases? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17 (1) (2020), 10.1186/s12966-020-00955-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tang MSS, Moore K, McGavigan A, Clark RA, Ganesan AN, Effectiveness of wearable trackers on physical activity in healthy adults: systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8 (7) (2020) e15576, 10.2196/15576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu S, Li G, Du L, Chen S, Zhang X, He Q, The effectiveness of wearable activity trackers for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary time in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis, DIGITAL HEALTH 9 (2023), 10.1177/20552076231176705, 20552076231176705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Brickwood K-J, Watson G, O’Brien J, Williams AD, Consumer-based wearable activity trackers increase physical activity participation: systematic review and Meta-analysis, JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7 (4) (2019) e11819, 10.2196/11819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Friel CP, Cornelius T, Diaz KM, Factors associated with long-term wearable physical activity monitor user engagement, translational, Behav. Med. 11 (1) (2021) 262–269, 10.1093/tbm/ibz153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Patel MS, Benjamin EJ, Volpp KG, Fox CS, Small DS, Massaro JM, et al. , Effect of a game-based intervention designed to enhance social incentives to increase physical activity among families: the BE FIT randomized clinical trial, JAMA, Intern. Med. 177 (11) (2017) 1586–1593, 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Patel MS, Small DS, Harrison JD, Fortunato MP, Oon AL, Rareshide CAL, et al. , Effectiveness of behaviorally designed gamification interventions with social incentives for increasing physical activity among overweight and obese adults across the United States: the STEP UP randomized clinical trial, JAMA, Intern. Med. 179 (12) (2019) 1624–1632, 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Patel MS, Small DS, Harrison JD, Hilbert V, Fortunato MP, Oon AL, et al. , Effect of behaviorally designed gamification with social incentives on lifestyle modification among adults with uncontrolled diabetes: a randomized clinical trial, JAMA Netw. Open 4 (5) (2021) e2110255, 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Harkins KA, Kullgren JT, Bellamy SL, Karlawish J, Glanz K, A trial of financial and social incentives to increase older adults’ walking, Am. J. Prev. Med. 52 (5) (2017) e123–e130, 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Landes SJ, McBain SA, Curran GM, An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs, Psychiatry Res. 280 (2019) 112513, 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, Boone LR, Schlundt DG, Mouton CP, et al. , Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research, Acad. Med. 90 (12) (2015) 1646–1650, 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Scheffey K, Avelis J, Patel M, Oon AL, Evans C, Glanz K, Use of community engagement studios to adapt a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study of social incentives and physical activity for the STEP together study, Health Promot. Pract. 25 (2) (2024) 285–292, 10.1177/15248399221113863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Asch DA, Volpp KG, On the way to health, LDI Issue Brief 17 (9) (2012) 1–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22934330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bassett DR Jr., Wyatt HR, Thompson H, Peters JC, Hill JO, Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in U.S. adults, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 42 (10) (2010) 1819–1825, 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc2e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kang M, Hart PD, Kim Y, Establishing a threshold for the number of missing days using 7 d pedometer data, Physiol. Meas. 33 (11) (2012) 1877–1885, 10.1088/0967-3334/33/11/1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chokshi NP, Adusumalli S, Small DS, Morris A, Feingold J, Ha YP, et al. , Loss-framed financial incentives and personalized goal-setting to increase physical activity among ischemic heart disease patients using wearable devices:The active reward randomized trial, J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7 (12) (2018), 10.1161/jaha.118.009173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Patel MS, Bachireddy C, Small DS, Harrison JD, Harrington TO, Oon AL, et al. , Effect of goal-setting approaches within a gamification intervention to increase physical activity among economically disadvantaged adults at elevated risk for major adverse cardiovascular events: the ENGAGE randomized clinical trial, JAMA Cardiol. 6 (12) (2021) 1387–1396, 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fanaroff AC, Patel MS, Chokshi N, Coratti S, Farraday D, Norton L, et al. , A randomized controlled trial of gamification, financial incentives, or both to increase physical activity among patients with elevated risk for cardiovascular disease: rationale and design of the be active study, Am. Heart J. 260 (2023) 82–89, 10.1016/j.ahj.2023.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. , The physical activity guidelines for Americans, JAMA 320 (19) (2018) 2020–2028, 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Marshall SJ, Levy SS, Tudor-Locke CE, Kolkhorst FW, Wooten KM, Ji M, et al. , Translating physical activity recommendations into a pedometer-based step goal: 3000 steps in 30 minutes, Am. J. Prev. Med. 36 (5) (2009) 410–415, 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rogers T, Milkman KL, Volpp KG, Commitment devices: using initiatives to change behavior, JAMA 311 (20) (2014) 2065–2066, 10.1001/jama.2014.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kahneman D, Tversky A, Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk, Econometrica 47 (2) (1979) 263, 10.2307/1914185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Patel MS, Asch DA, Rosin R, Small DS, Bellamy SL, Heuer J, et al. , Framing financial incentives to increase physical activity among overweight and obese adults: a randomized, controlled trial, Ann. Intern. Med. 164 (6) (2016) 385–394, 10.7326/m15-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dai H, Milkman KL, Riis J, The fresh start effect: temporal landmarks motivate aspirational behavior, Manag. Sci. 60 (10) (2014) 2563–2582, 10.1287/mnsc.2014.1901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL, The MOS social support survey, Soc. Sci. Med. 32 (6) (1991) 705–714, 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, et al. , Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study, Qual. Life Res. 22 (7) (2013) 1717–1727, 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. , International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35 (8) (2003) 1381–1395, 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Mullen SP, Olson EA, Phillips SM, Szabo AN, Wojcicki TR, Mailey EL, et al. , Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in older adults: invariance of the physical activity enjoyment scale (paces) across groups and time, Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 8 (2011) 103, 10.1186/1479-5868-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chen C, Weyland S, Fritsch J, Woll A, Niessner C, Burchartz A, et al. , A short version of the physical activity enjoyment scale: development and psychometric properties, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (21) (2021), 10.3390/ijerph182111035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sallis JF, Pinski RB, Grossman RM, Patterson TL, Nader PR, The development of self-efficacy scales for healthrelated diet and exercise behaviors, Health Educ. Res. 3 (3) (1988) 283–292, 10.1093/her/3.3.283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ, The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research, Psychiatry Res. 28 (2) (1989) 193–213, 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, The patient health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener, Med. Care 41 (11) (2003) 1284–1292, 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC, Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science, Implement. Sci. 4 (2009) 50, 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J, The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback, Implement. Sci. 17 (1) (2022) 75, 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Glanz K, Kather C, Chung A, Choi JR, Volpp KG, Clapp J, Qualitative study of perceptions of factors contributing to success or failure among participants in a US weight loss trial of financial incentives and environmental change strategies, BMJ Open 14 (3) (2024) e078111, 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Glaser B, Strauss A, Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Aldine Pub. Co, Chicago, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kang M, Rowe DA, Barreira TV, Robinson TS, Mahar MT, Individual information-centered approach for handling physical activity missing data, Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 80 (2) (2009) 131–137, 10.1080/02701367.2009.10599546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Fanaroff AC, Patel MS, Chokshi N, Coratti S, Farraday D, Norton L, et al. , Effect of gamification, financial incentives, or both to increase physical activity among patients at high risk of cardiovascular events: the BE ACTIVE randomized controlled trial, Circulation 149 (21) (2024) 1639–1649, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.069531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rubin DB, Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys, 1987. XXIX+258pp. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Patel MS, Asch DA, Rosin R, Small DS, Bellamy SL, Eberbach K, et al. , Individual versus team-based financial incentives to increase physical activity: a randomized, controlled trial, J. Gen. Intern. Med. 31 (7) (2016) 746–754, 10.1007/s11606-016-3627-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Patel MS, Volpp KG, Rosin R, Bellamy SL, Small DS, Fletcher MA, et al. , A randomized trial of social comparison feedback and financial incentives to increase physical activity, Am. J. Health Promot. 30 (6) (2016) 416–424, 10.1177/0890117116658195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Holm S, A simple sequentially Rejective multiple test procedure, Scand. J. Stat. 6 (2) (1979) 65–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Steinberg JR, Turner BE, Weeks BT, Magnani CJ, Wong BO, Rodriguez F, et al. , Analysis of female enrollment and participant sex by burden of disease in US clinical trials between 2000 and 2020, JAMA Netw. Open 4 (6) (2021), 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13749 e2113749–e2113749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure, J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (9) (2001) 606–613, 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Alley SJ, Schoeppe S, To QG, Parkinson L, van Uffelen J, Hunt S, et al. , Engagement, acceptability, usability and satisfaction with active for life, a computer-tailored web-based physical activity intervention using Fitbits in older adults, Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 20 (1) (2023) 15, 10.1186/s12966-023-01406-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Germini F, Noronha N, Borg Debono V, Abraham Philip B, Pete D, Navarro T, et al. , Accuracy and acceptability of wrist-wearable activity-tracking devices: systematic review of the literature, J. Med. Internet Res. 24 (1) (2022) e30791, 10.2196/30791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Glanz K, Steffen AD, Taglialatela LA, Effects of colon cancer risk counseling for first-degree relatives, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16 (7) (2007) 1485–1491, 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Glanz K, Schoenfeld ER, Steffen A, A randomized trial of tailored skin cancer prevention messages for adults: project SCAPE, Am. J. Public Health 100 (4) (2010) 735–741, 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].St Fleur RG, St George SM, Leite R, Kobayashi M, Agosto Y, Jake-Schoffman DE, Use of Fitbit devices in physical activity intervention studies across the life course, Narrative Review, JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9 (5) (2021) e23411, 10.2196/23411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Vandelanotte C, Duncan MJ, Maher CA, Schoeppe S, Rebar AL, Power DA, et al. , The effectiveness of a web-based computer-tailored physical activity intervention using Fitbit activity trackers: randomized trial, J. Med. Internet Res. 20 (12) (2018) e11321, 10.2196/11321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.