Structured Abstract

Objective

Identify survey, interview, and observational measures and measurement tools to assess constructs associated with Total Worker Health® (TWH)

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to identify articles that presented or evaluated measures and tools associated with worker health, safety, and well-being. We supplemented this review with a scan of NIOSH’s TWH website and those of the Centers of Excellence for TWH. We extracted information about the measures and tools, including descriptive attributes, substantive focus, and evidence of psychometric evaluation.

Results

We identified 102 measures and tools. Substantively, many addressed the conditions of work and worker safety, health, and well-being outcomes. Ten measures and tools did not have an available psychometric evaluation.

Conclusions

This work advances the science of TWH by identifying available measures and tools that researchers and practitioners can use when designing, implementing, and evaluating future studies.

Keywords: Total Worker Health®, occupational health and safety, workplace health promotion, worker well-being, worker health, worker safety, measures

Introduction

In 2011, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) introduced Total Worker Health® (TWH) as a comprehensive approach to promote the health, safety, and well-being of all workers. TWH is defined as the “policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness-prevention efforts to advance worker well-being”.1 As such, the TWH approach unites traditionally distinct occupational health and safety and workplace health promotion domains to offer a more holistic, integrated, and interdisciplinary perspective.2,3 Whereas occupational health and safety interventions traditionally focused on reducing work-related health and safety risks and associated outcomes (e.g., occupational injuries and fatalities, hazardous exposures), TWH approaches incorporate broader efforts, both within and beyond the workplace, to improve worker well-being.4 TWH similarly builds on workplace health promotion efforts (e.g., wellness programs) by advocating for working conditions that support worker health and safety.4 TWH thus represents a paradigm shift in how researchers and practitioners approach worker health and safety.5

Sorensen and colleagues developed a conceptual framework to help researchers and practitioners interested in embracing a TWH perspective.6 The first version of the framework, published in 2016, was developed to clarify relationships between workplace policies and practices, worker characteristics, the conditions of work, and outcomes for workers and employers.7 It focused especially on documenting the relationship between working conditions and worker health, safety, and well-being outcomes. The second version of the framework, published in 2021, expanded the first by situating conceptual relationships specified in the original model within the larger “socio-political-economic environments” in which work occurs.6 According to the authors, such environments affect the nature of the workforce, the organization of work, and labor relations.

The breadth of TWH and associated framework constructs6 require corresponding measures and tools to accurately assess a diverse set of exposures and outcomes across levels of measurement. Moving toward the identification of “consensus measures” (also sometimes referred to as “common outcome sets”) may address this need. Consensus measures are agreed upon, standardized approaches for assessing a construct of interest intended to be used by researchers and practitioners across different studies and settings. Consensus measures support evidence building by facilitating cross-study comparisons, integrated data analysis, and validation studies, which can enhance the generalizability and applicability of research findings. Consensus measures also help their users operationalize complex and multidimensional concepts such as work-related stress, organizational culture, or worker engagement. The National Institutes of Health’s PhenX Toolkit8 and the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative9 are examples of existing efforts to establish common measures

The purpose of this study is to conduct a scoping review10 to identify existing measures and measurement tools that can be used to assess TWH outcomes and factors associated with those outcomes. Although measures and tools are defined separately—measures referring to specific metrics and methods to assess a defined construct, and tools to the instruments used to capture data across measures—we aim to capture both, owing to the relative novelty of the field. We searched for measures and tools that cover a range of domains relevant to TWH, including indicators for assessing the conditions of work; worker safety, health, and well-being; and enterprise policies, programs, practices, and outcomes. We also focused on measures and tools that can be completed by or about workers or workplace representatives without the need of specialized biological, physiological, laboratory, or environmental data capture. Candidate measures and tools thus align with data collection using surveys, interviews, checklists, and other self-report or observational methods. We intend for the findings to help researchers and practitioners who are interested in designing, implementing, and/or evaluating TWH interventions across settings and populations. Researchers can use the measures and tools to select appropriate indicators for their research questions, hypotheses, and designs, as well as to identify gaps and opportunities for developing or improving measures and tools. Practitioners can use the measures and tools to assess the needs, strengths, and challenges for their organizations and workers; to monitor and evaluate the progress and impact of their TWH interventions; and to inform their decision-making and strategy. The broader vision for this scoping review is that we will facilitate the national TWH agenda by advancing rigorous, standardized methods for studying TWH11,12 and inform future consensus building needed to establish common measures for TWH.

Methods

We conducted a two-phase scoping review10 to identify TWH measures and tools. Phase 1 consisted of a systematic search of bibliographic databases. Phase 2 entailed a targeted review of key TWH websites.

Phase 1: Systematic Literature Search of Bibliographic Databases

During Phase 1, we searched for TWH measures and tools in the published literature. We conducted the search using two electronic databases: PubMed and Web of Science. We defined a preliminary set of search terms to identify the articles that focused on 1) the workplace/employment context, 2) TWH, health promotion, or health protection, and 3) measures, tools, or measurement. We refined the terms through an iterative process, adding, removing, and refining keywords after skimming the results. Table 1 shows the final keywords and MeSH terms used for the search. We further restricted the search based on the following inclusion criteria: peer reviewed articles only, written in English, published from January 2000 to March 2023 (the date of the search), and based on research within the U.S. We focused on the period after 2000 because the field of TWH grew out of a symposium, Steps to a Healthier US Workforce, in the early 2000s.13

Table 1.

Search keywords and terms

| Keywords | (“workplace context” AND (“workplace health promotion” OR “occupational health and safety” OR “total worker health”) AND “measures”) NOT (“QuickStats” OR “work group*” OR “workgroup*”) |

| Search terms | MeSH Terms |

| Workplace context | “work” OR “worker*” OR “workplace” OR “worksite” OR “job” OR “jobs” OR “jobsite” OR “occupation*” OR “employ*” OR “industr*” |

| Workplace health promotion | “well being” OR “wellbeing” OR “wellness” OR “health” OR “chronic” |

| Occupational health and safety | “safe*” OR “protect*” OR “condition*” OR “pain” OR “injur*” OR “illness*” OR “exposure*” OR “accident*” OR “fatalit*” OR “death*” OR “hazard*” OR “mortalit*” |

| Total worker health | “total worker health” |

| Measures and tools | “measur*” OR “survey*” OR “questionnaire*” OR “scale*” OR “tool” OR “indicator*” OR “instrument*” OR “assess*” OR “index*” OR “indices” |

Note: MeSH = Medical Subject Headings, which are used for indexing journal articles. Distinctions between the search terms for workplace health promotion, occupational health and safety, and TWH terms were made to ensure a comprehensive search but are oversimplifications and did not matter in practice.

After completing our search, we used Covidence systematic review software to further assess articles for relevance. We uploaded a reference library of the articles returned from our search into the software for an initial screening based on the article titles and abstracts. In addition to the inclusion criteria applied to our article search, we required that the articles:

Relate to worker health, safety, or well-being outcomes, or workplace policies, programs, or practices explicitly linked to those outcomes;

Identify or use at least one data collection instrument completed by an industry representative, employer, or worker, or related stakeholder; and

Describe the development or psychometric assessment of at least one measure/tool.

Using detailed instructions for inclusion and exclusion, two reviewers and the lead author independently screened a subset of 10 titles and abstracts and then met to discuss the screening process and compare their conclusions. After making minor changes to the screening process and instructions and piloting the changes with another 10 titles and abstracts, we felt the team was aligned. We divided the remaining titles and abstracts for screening among the reviewers. Once all titles and abstracts had been screened, a third reviewer and the lead author independently confirmed the titles and abstracts for inclusion in the next step. Using the same criteria as during title and abstract screening, one of the reviewers read through the full-text articles to make a final decision regarding the article’s eligibility. In cases of ambiguity, articles were flagged for senior review by the lead author. The lead author also reviewed the final set of articles recommended for inclusion.

We used a structured template to capture information regarding TWH measures and tools from eligible full text articles. Four independent reviewers and a senior reviewer received standardized procedures and definitions to extract information accurately and consistently. We completed two rounds of pilot extraction with four articles to refine the extraction template and process. Once the team reached alignment, the template was finalized and independent review began. Two independent reviewers were responsible for extracting information from each article. Throughout this process, the team met on a weekly basis to refine the process and template as needed based on unusual cases and team questions. At the conclusion of the process, the lead author compared the independent reviews, resolved disagreements, and finalized the extractions.

Descriptive fields within the extraction template included measure or tool name, article keywords, availability of measure or tool to the public, level of measurement, mode of completion, number of items, and whether the measure or tool was designed for a specific population. In addition to identifying and describing measures and tools for assessing constructs associated with TWH, we sought to compile information regarding whether the measures and tools had been evaluated using key indicators of validity and reliability. Specifically, we noted whether the measures had been assessed for content validity, criterion validity, construct validity, internal consistency, and test/retest agreement. Because authors commonly used different language and definitions for the same psychometric constructs and assessments, we present our study’s definitions for these constructs in Table 2. Although it was beyond the scope of this article to capture comprehensive information on all indicators used to assess measures14, we did in fact capture common forms of psychometric assessment used within the sources that are part of this review. We leave it to future researchers and practitioners to review our sources and decide for themselves whether the measures and tools cited here are sufficiently valid and reliable to align with their personal needs.

Table 2.

Indicators of psychometric evaluation extracted

| Indicator | Definition | Methods/statistics reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Content validity | The extent to which the measure represents all facets of the underlying construct it’s meant to assess (i.e., face validity) | Expert panel review, pilot testing, literature review |

| Criterion validity | The extent to which the measure relates to a “gold standard” or established measures for assessing the same construct | Sensitivity and specificity assessments; correlations |

| Construct validity | The extent to which a measure is useful for measuring what it is designed to measure; commonly assessed as convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity | Confirmatory or exploratory factor analysis, correlations, predictive modeling |

| Internal consistency | The extent to which items comprising a measure relate to each other, thus measuring the same construct | Cronbach’s alpha |

| Test/retest agreement | The extent to which a measure yields consistent results when administered at multiple points in time, presuming no change expected | Correlations |

Phase 2: Targeted Website Review

Because we necessarily limited our search of the literature during Phase 1 to manage the scope of the project, we knew there was a possibility that we may have missed key measures and tools actively in use by TWH researchers and practitioners. These measures and tools may have been introduced prior to 2000, developed or assessed outside the U.S., or disseminated outside the peer reviewed literature. To address this limitation, we supplemented our literature search with a review of key websites in the field of TWH. We sought out measures and tools that website authors promoted or cited, either on their pages or in sources linked from their pages.

First, we sought to identify candidate measures and tools using NIOSH’s TWH website15, considering NIOSH is the federal agency that pioneered TWH research and practice. Following an initial scan, we found an “assessment tools” webpage that was linked from NIOSH’s TWH pages and directed to a page maintained by another part of CDC. Following our review and before publication of this paper, the assessment tools webpage was taken down during a CDC website redesign.

Next, we identified candidate measures and tools from the websites of the ten TWH Centers of Excellence16, which are funded by NIOSH to advance the science of TWH. Within each Center’s website, we first reviewed all webpages that addressed research, measurement, and publications. We then conducted a keyword search within each site for the word “measure.”

After we compiled a list of candidate measures and tools from all websites, the lead author reviewed them to assess relevance to the goals of this paper. Another author then extracted information regarding the supplementary measures and tools using the same template used during Phase 1, and the lead author reviewed and finalized those extractions.

Synthesis

We organized the final set of measures and tools in tabular and narrative formats using the conceptual model for integrating worksite health protection and health promotion proposed by Sorensen et al.6 This includes the following concepts:

Enterprise policies, programs, and practices are the things employers support, enact, and do that have implications for worker health, safety, and well-being – whether positive or negative.

Conditions of work refer to the physical or social conditions of work, organization of work, job design, and the psychosocial work environment. These conditions are affected by employers’ policies, programs, and practices and have implications for enterprise outcomes.

Enterprise outcomes include worker productivity, work quality, turnover, work absence, and health care spending. Employers commonly implement enterprise policies, programs, and practices with the hope that enterprise outcomes will improve.

Worker safety, health, and well-being are commonly the ultimate outcomes of interest to researchers and practitioners assessing TWH interventions. They are influenced by enterprise policies, programs, and practices and by the conditions of work. This category includes precursors to safety and well-being that were called “worker proximal outcomes” in an earlier version of Sorensen’s model7, such as workers’ health and safety behaviors, engagement in workplace programs, beliefs, knowledge, and skills. Although advancing worker safety, health, and well-being is an end in itself, improvements in worker outcomes can also enhance enterprise outcomes.

Results

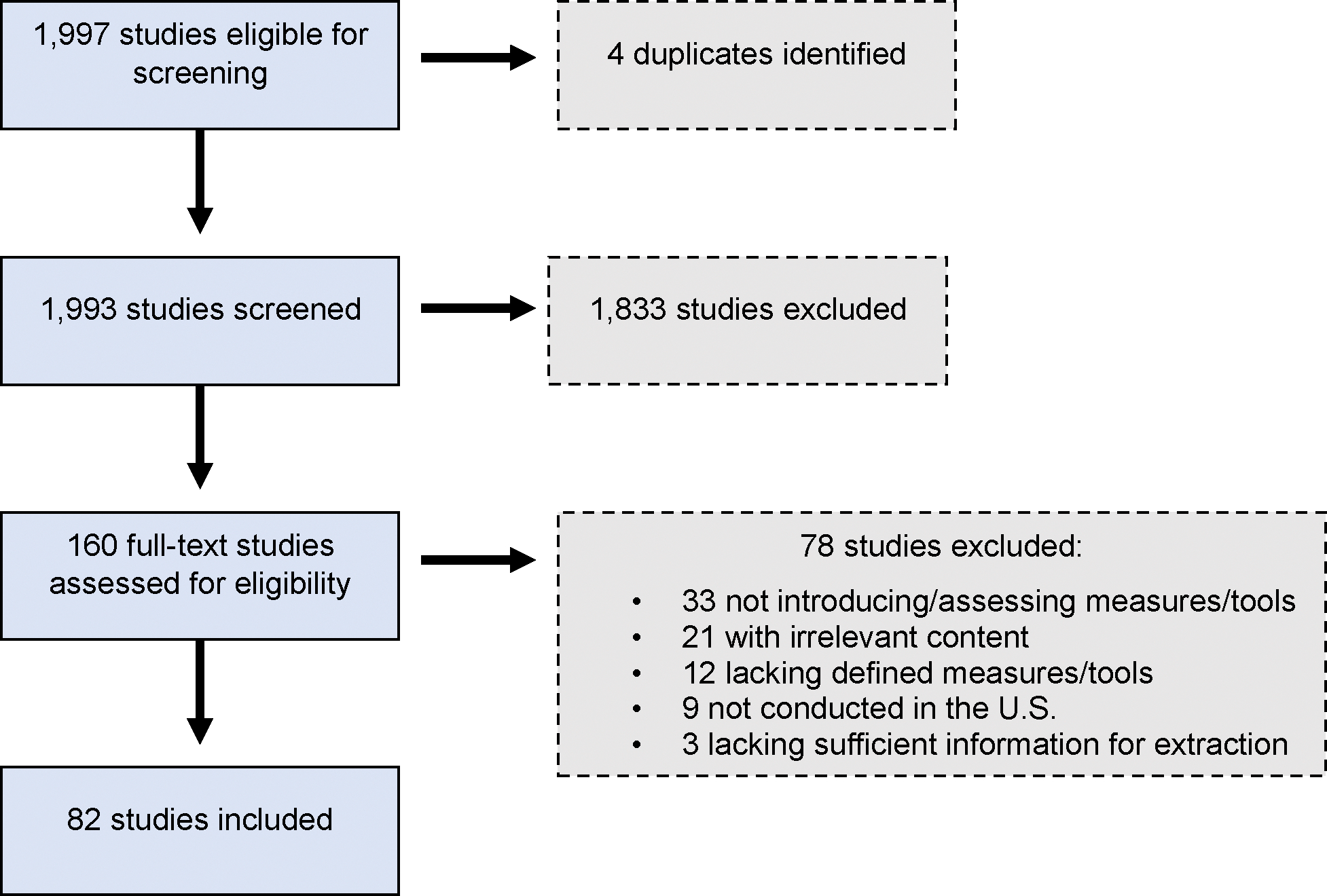

We identified a total of 102 measures and tools from 100 sources. The number of sources differs from the number of measures and tools because some sources contained information on multiple measures and tools, and some measures and tools were evaluated across multiple studies. Figure 1 summarizes the results of our systematic literature search. We screened 1,997 titles and abstracts; 1,833 did not meet our inclusion criteria. Of the 160 remaining titles and abstracts, 82 articles reporting on 88 unique measures and tools were deemed eligible after full text review. From the 11 websites we scanned (the CDC’s “assessment tools” page and those of the 10 TWH Centers for Excellence), we identified an additional 14 measures and tools.

Figure 1.

Summary of Phase 1: Targeted Literature Search

Table 3 provides descriptive information regarding the 102 measures and tools we identified. Although our inclusion criteria allowed for a variety of data collection modes, all but six of the 102 measures and tools (94%) were designed exclusively for survey data collection. About three-quarters of the measures and tools (N=79) were assessed at the worker level. Nearly all the measures and tools (82%) were publicly available in the articles we reviewed and/or via an external website, but in some cases (N=15, 15%), it was unclear. The measures and tools contained between two to over 100 self-report items, with most (N=71, 70%) containing fewer than 50 self-report items. For 16 measures and tools, different versions varying in length were assessed within and across articles. Most of the measures and tools (N=63, 62%) were designed for general use across workplaces and/or workers. Of the measures and tools designed for more targeted use (N=39, 38%), they were intended for a specific occupation or industry (N=22, 56%; mostly construction/healthcare), health risk or ailment (N=13, 33%), or type of work (N=4, including lone workers, office workers, and remote workers). Five measures and tools were assessed for use with workers from specific cultures or who spoke specific languages (mostly Hispanic workers).

Table 3.

Descriptive features of measures and tools for studying TWH (N=102)

| Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mode of data collection | ||

| Survey only | 96 | 94 |

| Interview only | 3 | 3 |

| Other/mixed | 3 | 3 |

| Level of measurement | ||

| Worker | 78 | 76 |

| Workplace/site | 22 | 22 |

| Other/mixed | 2 | 2 |

| All items publicly available | ||

| Yes | 84 | 82 |

| No | 3 | 3 |

| Unclear from source(s) reviewed | 15 | 15 |

| Number of self-report items | ||

| Less than 10 | 27 | 26 |

| 10–19 | 18 | 18 |

| 20–49 | 26 | 25 |

| 50–100 | 7 | 7 |

| 100 or more | 8 | 8 |

| Multiple versions/not available | 16 | 16 |

| Designed for a specific worker population | ||

| Yes | 39 | 38 |

| No | 63 | 62 |

| If designed for a specific population, how defined | ||

| Occupation/industry | 22 | 56 |

| Health risk/ailment | 13 | 33 |

| Type of work | 4 | 10 |

| Assessed for use across cultures/languages | ||

| Yes | 5 | 5 |

| No | 97 | 97 |

| Types of psychometric evaluation completed | ||

| Content validity | 70 | 69 |

| Criterion validity | 17 | 15 |

| Construct validity | 79 | 74 |

| Internal consistency | 63 | 59 |

| Test/retest agreement | 18 | 18 |

| None of the above | 10 | 10 |

Table 3 also identifies the number and percentage of measures and tools for which we found evidence of validity and/or reliability assessment. As the table reflects, close to three-quarters of the measures and tools were assessed for construct validity (N=79, 74%). Assessments of content validity (N=70, 69%) and internal consistency (N=63, 59%) were also common. Fewer than half the measures and tools were evaluated for criterion validity (N=17, 15%) or test-retest agreement (N=18, 18%). Only 10 measures and tools were introduced or assessed in the sources we reviewed without any evidence of psychometric evaluation.

Table 4 lists each of the 102 measures and tools we identified organized using Sorensen et al.’s conceptual model for integrating worksite health protection and health promotion.6 In total, 18 measures and tools relate to enterprise policies, programs, and practices; 34 relate to the conditions of work; 30 relate to worker safety, health, and well-being; 17 relate to enterprise outcomes; and 3 measures and tools cut across the categories. Table 4 also shows subcategories that we developed inductively within the Sorensen model, which we suspected may be of interest to future researchers. We used symbols to signify level of measurement for each measure and tool and we found evidence of validity or reliability assessment.

Table 4.

Measures and tools for studying TWH by substantive category (N=102)

| Subcategory | Measure/Tool Name and Source(s) | LOM | PE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise policies, programs, and practices (N=18) | |||

| General offerings (N=7) | Workplace Health Achievement Index (WHAI)17 | E | N |

| HERO Health and Wellbeing Best Practices Scorecard (HERO Scorecard)18 | E | N, S, C | |

| Workplace Readiness Questionnaire19 | E | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed measure of management efforts with respect to integration of quality, safety, and ergonomics issues in manufacturing20 | E | N, S, C | |

| WorkCheck21 | E | N, S | |

| HealthLead Assessment22 | E | N | |

| CDC Worksite Health ScoreCard (HSC)17,23 | E | N | |

| Specific offerings/health issues (N=8) | Heart Check / Heart Check Lite (HCL)21,24 | E | N, T, S, C |

| Unnamed wellness committee implementation index25 | E | N, S | |

| Total Worker Health Employer Preparedness Survey26 | E | N | |

| Working Well21 | E | - | |

| Health Links Assessment: Food@Work Module27 | E | - | |

| Health Links Assessment: Mental Health Module27 | E | - | |

| Health Links Assessment: Family-Friendly Module27 | E | - | |

| Health Links Assessment: Get Outdoors Module27 | E | - | |

| TWH (N=3) | The Integration Score28,29 | E | N, S, C |

| Workplace Integrated Safety and Health Assessment (WISH)30,31 | E | N, S | |

| Dimensions of Corporate Integration32 | E | - | |

| Conditions of work (N=34) | |||

| Exposures to physical or psychosocial hazards (N=4) | Unnamed occupational exposure questionnaire for parkinsonism in welders33 | W | N, T, A |

| Modified Job Requirements and Physical Demands Survey (JRPDS)34 | W | T, S, C | |

| Nature Contact Questionnaire (NCQ)35 | W | N, S, A | |

| Healthy Work Survey (HWS)36,37 | W | N, S, C, A | |

| Job demands and control (N=4) | Job Demands Scale38 | W | S, C |

| Job Leeway Scale (JLS)39 | W | N, S, C | |

| Decision Latitude Scale38 | W | S, C | |

| Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ)40 | W | N | |

| Safety/safety climate (N=12) | Unnamed safety climate scale41 | W | N, T, S, C |

| Unnamed safety climate scale42 | W | N, T, S, C | |

| Personal Workplace Safety Instrument for Emergency Nurses (PWSI-EN)43,44 | W | N, S, C | |

| Safety Management Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SH-26)45 | E | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed inter-organizational safety climate instrument46 | O | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed safety climate scale47 | W | N, S, C | |

| Workplace Safety Supplemental Items for Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Surveys on Patient Safety Culture (SOPS) Hospital Survey48 | W | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed university safety climate survey49 | W | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed generic safety climate scale for lone workers50 | W | S, C | |

| English/Spanish Safety Climate Scale for Construction Workers51 | W | N, C | |

| Assessment of Contractor Safety (ACES) Survey52 | E | N, S | |

| Unnamed instrument to assess work environment factors for injury prevention in the food service industry53 | E | N | |

| Work/life balance (N=2) | Work-Health Management Interference (WHMI) Measure54 | W | N, S, C |

| Unnamed work-life balance scale55 | W | S, C | |

| Workplace climate/culture of health (N=9) | Ergonomics Climate Assessment56 | W | N, S, C, A |

| Workplace Support for Health (WSH) Scale57 | W | N, T, S, C, A | |

| Leading by Example (LBE) Questionnaire58,59 | E, W | N, S, C | |

| Healthy Work Environment Inventory (HWEI)60 | W | N, S, C | |

| Workplace Culture of Health (COH) Scale61 | W | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed measure of workplace climate in community clinics and health centers62 | E | N, S, C | |

| Public Health Nurse (PHN) Work Environment Survey63 | W | N, S, C | |

| Relative Environment Assessment Lens (REAL) Indicator64 | W | N | |

| CDC NHWP Health and Safety Climate Survey (INPUTS)65 | W | - | |

| Other (N=3) | Unnamed occupational health history questionnaire66 | W | N, S, A |

| Anticipated Work Discrimination Scale67 | W | N, S, C | |

| Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal with Supervisor (RISCS)68 | W | S, C | |

| Enterprise outcomes (N=17) | |||

| General effects of health on productivity (N=10) | Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS)69 | W | S, C, A |

| World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ)69–72 | W | N, T, S, C, A | |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) - General Health69,70,73 | W | N, S, A | |

| Stanford Presenteeism Scale (SPS-6)70,74 | W | N, T, S, C | |

| Health and Work Questionnaire (HWQ)69,75 | W | N, T, S, C | |

| Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ)69,70 | W | N, S, C | |

| World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) work functioning subscale76 | W | T, S | |

| Employer Health Coalition (EHC) of Tampa Assessment Instrument Impairment at Work Scale70 | W | T, S | |

| Work Productivity Short Inventory (WPSI)77,78 | W | N, S | |

| Health and Labor Questionnaire (HLQ)69 | W | T | |

| Effects of specific health issues on productivity (N=7) | Migraine Work and Productivity Loss Questionnaire (MWPLQ)69,70 | W | S, C |

| Migraine Disability Assessment Questionnaire69 | W | S, C, A | |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) - Allergic Rhinitis Questionnaire69 | W | S, A | |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) - Chronic Hand Dermatitis Questionnaire69 | W | S, A | |

| Social Role (SR) Scale of the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ)79 | W | S | |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) - Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire69 | W | S | |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) - Special Health Problem Questionnaire69 | W | - | |

| Worker safety, health, and well-being (N=30) | |||

| Mental health and burnout (N=5) | Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory80 | W | T, S, C |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale81 | W | S, C | |

| Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS)82 | W | S, C | |

| Social Security Administration Behavioral Health Function (SSA-BH) instrument83 | W | S | |

| K-640 | W | N | |

| Satisfaction (N=2) | Satisfaction of Employees in Health Care Survey (SEHC)84 | W | N, S, C |

| The Caregiver Survey85 | W | S, C | |

| Well-being (N=10) | Affective Well-being at Work86,87 | W | N, S, C |

| Thriving from Work Questionnaire88,89 | W | N, T, S, C, A | |

| Unnamed employee well-being scale90 | W | N, S, C, A | |

| Teacher Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire (TSWQ)91 | W | N, S, C, A | |

| Workplace Wellbeing Questionnaire (WWQ)92 | W | N, S, A | |

| Work-Related Well-Being (WRWB) Index93 | W | N, T, S, C | |

| Eudaimonic Workplace Well-being Scale (EWWS)94 | W | N, S, C | |

| Index of Psychological Well-Being at Work95 | W | N, S, C | |

| WARR Scale of Job-related Affective Well-being (Warr’s Measure)95 | W | N, S, C | |

| Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS)96 | W | N, S, C | |

| Worker behavior (N=6) | Unnamed disruptive behavior scale97 | N, S, C | |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM)98 | W | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed measure of safety compliance99 | W | N, S, C | |

| Unnamed measure of safety participation99 | W | N, S, C | |

| Concise Physical Activity Questionnaire (CPAQ)100 | W | N, T, S | |

| NIOSH Health and Safety Practices Survey of Healthcare Workers101 | W | N | |

| Other/mixed (N=7) | Unnamed measure of leisure affect102 | W | N, S, C, A |

| Unnamed measure of leisure satisfaction102 | W | N, S, C, A | |

| Unnamed measure of measure of workstyle103 | W | N, S, C, A | |

| Unnamed knowledge, attitudes, perceptions (KAP) questionnaire104,105 | W | N, S, C | |

| Organizational Mattering Scale (OMS)106 | W | N, T, S, C | |

| The Integration Profile (TIP) workplace spirituality measure107 | W | S | |

| CDC National Healthy Worksite Program (NHWP) Employee Health Assessment (CAPTURE)108 | W | - | |

| Cross-category (N=3) | |||

| - | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Worker Well-Being Questionnaire (WellBQ)109 | W | N, S, C |

| Healthy Workplace Participatory Program (HWPP) All Employee Survey110 | W | N | |

| The California Work & Health Survey111 | W | - | |

Note: LOM = level of measurement: E = employer, W = worker, O= other. PE = psychometric evaluation: N = content validity, T = criterion validity, S = construct validity, C= internal consistency, A = test/retest agreement.

Discussion

In this paper, we identified 102 measures and tools that can be used to assess TWH outcomes and factors associated with those outcomes, including indicators for assessing the conditions of work; worker safety, health, and well-being; and enterprise policies, programs, practices, and outcomes. We used Sorensen’s conceptual model for TWH6 to organize the measures and tools for researchers and practitioners who are interested in designing, implementing, and/or evaluating TWH interventions across a variety of workplace settings and worker populations.

Our analysis revealed many strengths of existing measures and tools. Most are publicly available and can be accessed by researchers and practitioners at no charge. Most measures and tools identified were also designed for general use across various types of workers, workplaces, and industries, suggesting ample opportunities for adoption. Substantively, the measures/tools addressed the subset of categories of Sorensen et al.’s conceptual model of an integrated approach to worker health6 that we identified as relevant to this review. Consistent with their conceptual framework, measures and tools associated with the conditions of work comprise a relatively high proportion of those we identified. And, critically, all but 10 of the measures and tools were evaluated for validity and/or reliability using the indicators and criteria we defined – most commonly for construct validity, content validity, and internal consistency.

Our analysis also points to several limitations of the measures/tools available, with implications for both research and practice. Over half of the measures and tools we identified contained 20 or more unique self-report items, and 15 percent contained 50 or more. Although lengthy measures and tools may help researchers who are interested in a comprehensive and robust assessment of some underlying construct (e.g., the NIOSH WellBQ109), they can also be excessively burdensome for study participants. Compounding this issue, in our experience, studies focusing on TWH commonly entail assessment of multiple constructs, and researchers/practitioners designing studies may need to make concessions with respect to measure burden to keep data collection manageable. For situations where burden may be a concern, we see opportunities to develop more concise tools and additional short-form measures. Several authors associated with the sources we reviewed were already proceeding in this way.18,19

We also found uneven substantive coverage of the measures and tools identified. For some topics, we identified many measures and tools with the same goal and felt it could be challenging for researchers/practitioners to select from among them – especially in the absence of an established gold standard for evaluating the underlying constructs. For example, we identified seven measures and tools designed to provide overall assessments of employers’ policies, programs, and practices relating to worker health, safety, and well-being. Similarly, we identified ten measures of worker well-being. Future researchers might consider using theory or the results of psychometric evaluation to evaluate the strengths and limitations of these measures and tools in relation to each other, as we observed some authors doing.69,70 This work to identify the best measures and tools for a particular construct could be part of defining common measures for TWH.

In contrast, some substantive topics seemed to have comparably limited measures and tools. For example, the measures and tools used to assess enterprise outcomes focused exclusively on productivity, which is just one of many outcomes that employers hope to improve when implementing TWH interventions.112 Although alternative enterprise outcomes may be easily monitored using data sources and indicators beyond the purview of this work (e.g., human resource records on absenteeism, days away from work, recruitment, retention), there nevertheless seem to be opportunities to develop new measures/tools aligned with this category. These might include proxy measures and tools designed for use at the worker level, which may be easier to integrate into TWH studies that do not directly engage employers.

Another limitation was that although just ten of the measures and tools we identified were not evaluated for any of indicators of validity or reliability that we assessed, some forms of psychometric assessment were less common than others. Only 15 percent of the measures and tools were assessed for criterion validity, which may make sense in the context of lacking gold standards for many key constructs associated with TWH. Without gold standards against which new measures can be developed, it can be difficult to determine which measures and tools should be promoted over others focusing on the same underlying construct(s). We also found limited evidence of test/retest agreement, perhaps due to overreliance on cross-sectional research designs. Expanded use of longitudinal data for reliability assessment can help address this limitation.

Considering the overwhelming number of measures and tools designed for survey data collection, we see opportunities to standardize measurement practices when using qualitative or observational approaches. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) website provides an example of how this might be accomplished. The CFIR website provides questions for qualitative interview guides that align with each construct in CFIR.113 Sharing these interview questions along with the construct definitions and supporting evidence helps align users’ thinking and data collection strategies.

There may also be opportunities to develop or assess additional measures and tools that are tailored for specific uses. Just over a third of the measures we identified were designed to focus on specific occupations, industries, health risks/ailments, or types of work, which could improve the precision of data collected and the perceived relevance of the measure or tool to study participants. We also identified a small number of measures and tools that had been assessed for use with workers from specific ethnicities, cultures, or linguistic preferences, and see value in continuing such efforts as to reflect the diversity of workplaces.

In combination with the gaps noted here, NIOSH’s National Occupational Research Agenda for Healthy Work Design and Well-Being114 may help researchers identify the most critical measures and tools needed to advance TWH. Experts prepared this agenda to establish priorities for occupational safety and health research based on the existing literature. The agenda identifies topics such as non-standard work, advancing technology, fatigue associated with shift work and long hours, worker well-being, quality of work life, and work/nonwork balance as requiring new measures or measurement approaches. For example, the introduction of artificial intelligence into the workplace could pose new risks to workers115 and thus imply opportunities for research and measurement to better assess those risks. Although we identified measures of worker well-being as part of this review, the remaining topics may be ripe for measure development.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we restricted sources for the systematic literature search to English-language, peer-reviewed papers published 2000 to 2023 from research conducted in the U.S. We mitigated this limitation by searching key websites in the field of TWH. We are nevertheless aware that there are measures and tools we did not capture that are still widely used by TWH researchers, such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory.116 Future researchers might expand our work by convening TWH experts to identify additional such measures.

Second, we did not complete a comprehensive review of all data sources that could be useful for TWH research and practice, as we excluded studies focusing exclusively on biological, physiological, laboratory, or environmental data capture; operational or organizational data from human resources; and employer partner data from health payers; employee assistance programs, or wellness vendors. We regard such data sources as critical for the field, but as beyond the scope of what we could present in a single review.

Third and related, we intentionally excluded measures and tools associated with some concepts in Sorensen et al.’s conceptual model.6 We did not capture measures associated with the policy/political/economic environment, employment and labor patterns, or enterprise or worker characteristics. Although we agree that these constructs are important for understanding worker safety, health, and well-being, they are not generally assessed using the same data collection approaches and participants as the measures and tools that we set out to identify. For example, the policy/political/economic environment and employment and labor patterns are typically assessed from the community to global level, and enterprise and worker characteristics are commonly captured in business and human resources records. We would not have been able to extract information regarding the excluded constructs comparable to that we extracted regarding self-reported approaches.

Lastly, we found it challenging to extract information about measures and tools from eligible studies due to the inconsistencies in what the authors reported. For example, with respect to the number of items within a measure or tool, some authors treated “select all that apply” questions as a single item, whereas others counted each response option as separate items. Authors also commonly used different terminology and statistics to assess the validity and reliability of the measures. Although we developed standard approaches to inform our extraction process, consistency nevertheless remained a challenge.

Future Work

This work can advance the science of TWH by helping independent occupational safety and health-related researchers, those associated with NIOSH’s Centers of Excellence for TWH, and members of the Society for TWH to begin aligning on measures and tools for studying key topics. Although this scoping review has been helpful for identifying available measures and tools, it stops short of promoting specific measures and tools for general use or use in specific situations. Ideally, experts in the field would use information from this article and other sources to identify the measures and tools that have been established as valid, reliable, and consistent with theory to achieve the benefits commonly associated with consensus measures.

Moving forward, the authors plan to use the information in this paper to design an interactive repository of the measures/tools that researchers and practitioners can use when planning new studies. We envision that repository users will be able to filter the list of measures and tools based on attributes such as level of measurement, number of items, substantive focus, and other characteristics to identify those most relevant to their work. The National Institutes of Health’s PhenX Toolkit8 serves as an example of what we envision.

Conclusion

Many measures and tools are available for researchers and practitioners to use when designing studies relating to TWH. These tools vary in their length, specificity, and focus. This scoping review advances the science of TWH by identifying available measures and tools and their characteristics, with the ultimate goal of strengthening the science of TWH for researchers and practitioners alike.

Bulleted Learning Outcomes.

Identify measures and measurement tools available to study constructs associated with Total Worker Health

Describe the characteristics of measures and tools available to study constructs associated with Total Worker Health

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank NIOSH, NINR, and RTI International’s Fellows Program for funding this work; Maija Leff and Leila Kahwati for their feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript; Georgia Karuntzos for support in conceptualizing this paper; and Mikayla Charles and Tara Vigil for early work in support of the analysis.

Funding sources for all authors:

This work was partially supported by the Carolina Center for Healthy Work Design and Worker Well-Being, funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as part of the Centers of Excellence for Total Worker Health® (grant number U19OH012303) and the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number T32NR007091–26). Additional funding came from RTI International’s Fellows program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest for all authors: None declared

Ethical disclosures: This review of available measures did not entail data collection from or about individuals and was thus not subject to human subjects’ regulations.

AI: Artificial intelligence was not used for any aspect of this research or preparing the findings for publication.

Data availability:

Readers should contact the corresponding author for any data requests associated with this article.

References

- 1.Lee MP, Hudson H, Richards R, Chang CC, Chosewood LC, Schill AL. Fundamentals of Total Worker Health Approaches: Essential Elements for Advancing Worker Safety, Health, and Well-Being. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Con trol and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2017–112; Cincinnati, OH: NIOSH Office for Total Worker Health; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2017-112/pdfs/2017_112.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC NIOSH. About the Total Worker Health® Approach Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/about/index.html. 2024. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 3.Punnett L, Cavallari JM, Henning RA, Nobrega S, Dugan AG, Cherniack MG. Defining ‘Integration’ for Total Worker Health®: A New Proposal. Ann Work Expo Health. 2020;64:223–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC NIOSH. Total Worker Health® Frequently Asked Questions. Total Worker Health Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/faq/index.html. 2024. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 5.Chosewood LC, Schill AL, Chang C-C, et al. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Total Worker Health® Program: The Third Decade. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2024;66:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorensen G, Dennerlein JT, Peters SE, Sabbath EL, Kelly EL, Wagner GR. The future of research on work, safety, health and wellbeing: A guiding conceptual framework. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;269:113593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorensen G, McLellan DL, Sabbath EL, et al. Integrating worksite health protection and health promotion: A conceptual model for intervention and research. Preventive Medicine. 2016;91:188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamers SL, Goetzel R, Kelly KM, et al. Research Methodologies for Total Worker Health®: Proceedings From a Workshop. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:968–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC NIOSH. National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA), National Total Worker Health Agenda (2016–2026): A national agenda to advance Total Worker Health research, practice, policy, and capacity. . Epub ahead of print 2016. DOI: 10.26616/NIOSHPUB2016114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson HL, Nigam JAS, Sauter SL, Chosewood LC, Schill AL, Howard J Total Worker Health. American Psychological Association; Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/4316192. 2019. Accessed January 17, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Patrick DL, et al. COSMIN Study Design checklist for Patient-reported outcome measurement instruments Available from: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf. 2019.

- 15.CDC NIOSH. Total Worker Health®. Total Worker Health Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/index.html. 2024. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 16.CDC NIOSH. Centers of Excellence for Total Worker Health®. NIOSH Extramural Research and Training Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/extramural-programs/php/about/twh_centers.html. 2024. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 17.Roemer EC, Kent KB, Goetzel RZ, Calitz C, Mills D. Reliability and Validity of the American Heart Association’s Workplace Health Achievement Index. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imboden MT, Castle PH, Johnson SS, et al. Development and Validity of a Workplace Health Promotion Best Practices Assessment. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hannon PA, Helfrich CD, Chan KG, et al. Development and Pilot Test of the Workplace Readiness Questionnaire, a Theory-Based Instrument to Measure Small Workplaces’ Readiness to Implement Wellness Programs. Am J Health Promot. 2017;31:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dzissah JS, Karwowski W, Rieger J, Stewart D. Measurement of management efforts with respect to integration of quality, safety, and ergonomics issues in manufacturing industry. Hum Factors Ergon Manuf. 2005;15:213–232. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golaszewski T, Barr D, Pronk N. Development of assessment tools to measure organizational support for employee health. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz AS, Pronk NP, Chestnut K, Pfeiffer GJ, Childress J. Congruence of Organizational Self-Score and Audit-Based Organizational Assessments of Workplace Health Capabilities: An Analysis of the HealthLead Workplace Accreditation. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roemer EC, Kent KB, Samoly DK, et al. Reliability and validity testing of the CDC Worksite Health ScoreCard: an assessment tool to help employers prevent heart disease, stroke, and related health conditions. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55:520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher BD, Golaszewski T. Heart check lite: modifications to an established worksite heart health assessment. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown MC, Harris JR, Hammerback K, et al. Development of a Wellness Committee Implementation Index for Workplace Health Promotion Programs in Small Businesses. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34:614–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roelofs C Total Worker Health(®) Employer Preparedness: A Proposed Model and Survey of Human Resource Managers’ Perceptions. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2022;17:e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Links. Health Links. Health Links Resource Center Available from: https://www.healthlinkscertified.org/resource-center/online-resources/health-links. 2018. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 28.Williams JA, Nelson CC, Cabán-Martinez AJ, et al. Validation of a New Metric for Assessing the Integration of Health Protection and Health Promotion in a Sample of Small- and Medium-Sized Employer Groups. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57:1017–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams JAR, Schult TM, Nelson CC, et al. Validation and Dimensionality of the Integration of Health Protection and Health Promotion Score: Evidence from the PULSE small business and VA Medical Center Surveys. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.López Gómez MA, Gundersen DA, Boden LI, et al. Validation of the Workplace Integrated Safety and Health (WISH) assessment in a sample of nursing homes using Item Response Theory (IRT) methods. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e045656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorensen G, Sparer E, Williams JAR, et al. Measuring Best Practices for Workplace Safety, Health, and Well-Being: The Workplace Integrated Safety and Health Assessment. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:430–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Center for Work, Health, & Well-being. Dimensions of Corporate Integration Available from: https://centerforworkhealth.sph.harvard.edu/resources/dimensions-corporate-integration. 2013. Accessed January 17, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hobson AJ, Sterling DA, Emo B, et al. Validity and reliability of an occupational exposure questionnaire for parkinsonism in welders. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2009;6:324–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dane D, Feuerstein M, Huang GD, Dimberg L, Ali D, Lincoln A. Measurement properties of a self-report index of ergonomic exposures for use in an office work environment. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Largo-Wight E, Chen WW, Dodd V, Weiler R. The Nature Contact Questionnaire: a measure of healthy workplace exposure. Work. 2011;40:411–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobson M, Schnall P, Faghri P, Landsbergis P. The Healthy Work Survey (HWS): A Standardized Questionnaire for the Assessment of Workplace Psychosocial Hazards and Work Organization in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. . Epub ahead of print 2023. DOI: 10.1097/jom.0000000000002820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi B, Seo Y. Developing a short standard questionnaire for assessing work organization hazards: the Healthy Work Survey (HWS). Ann Occup Environ Med. 2023;35:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alterman T, Gabbard S, Grzywacz JG, et al. Evaluating Job Demands and Control Measures for Use in Farm Worker Health Surveillance. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17:1364–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw WS, Dugan AG, McGonagle AK, Nicholas MK, Tveito TH. The Job Leeway Scale: Initial Evaluation of a Self-report Measure of Health-Related Flexibility and Latitude at Work. J Occup Rehabil. . Epub ahead of print 2023. DOI: 10.1007/s10926-023-10095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grzywacz JG, Alterman T, Muntaner C, Gabbard S, Nakamoto J, Carroll DJ. Measuring job characteristics and mental health among Latino farmworkers: results from cognitive testing. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang YH, Zohar D, Robertson MM, Garabet A, Murphy LA, Lee J. Development and validation of safety climate scales for mobile remote workers using utility/electrical workers as exemplar. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;59:76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang YH, Zohar D, Robertson MM, Garabet A, Lee J, Murphy LA. Development and validation of safety climate scales for lone workers using truck drivers as exemplar. Transp Res Pt F-Traffic Psychol Behav. 2013;17:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burchill C Development of the Personal Workplace Safety Instrument for Emergency Nurses. Work. 2015;51:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burchill CN, Bena J, Polomano RC. Psychometric Testing of the Personal Workplace Safety Instrument for Emergency Nurses. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore LL, Wurzelbacher SJ, Chen IC, Lampl MP, Naber SJ. Reliability and validity of an employer-completed safety hazard and management assessment questionnaire. J Safety Res. 2022;81:283–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saunders LW, Kleiner BM, McCoy AP, Ellis KP, Smith-Jackson T, Wernz C. Developing an inter-organizational safety climate instrument for the construction industry. Saf Sci. 2017;98:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cigularov KP, Chen PY, Rosecrance J. The effects of error management climate and safety communication on safety: A multi-level study. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2010;42:1498–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zebrak K, Yount N, Sorra J, et al. Development, Pilot Study, and Psychometric Analysis of the AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture™ (SOPS(®)) Workplace Safety Supplemental Items for Hospitals. Int J Environ Res Public Health;19 . Epub ahead of print 2022. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19116815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gutierrez JM, Emery RJ, Whitehead LW, Felknor SA. A means for measuring safety climate in the university work setting. J Chem Health Saf. 2013;20:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee J, Huang YH, Robertson MM, Murphy LA, Garabet A, Chang WR. External validity of a generic safety climate scale for lone workers across different industries and companies. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;63:138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jorgensen E, Sokas RK, Nickels L, Gao W, Gittleman JL. An English/Spanish safety climate scale for construction workers. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50:438–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dennerlein JT, Weinstein D, Huynh W, et al. Associations between a safety prequalification survey and worker safety experiences on commercial construction sites. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63:766–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markkanen P, Peters SE, Grant M, et al. Development and application of an innovative instrument to assess work environment factors for injury prevention in the food service industry. Work. 2021;68:641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGonagle AK, Schmidt S, Speights SL. Work-Health Management Interference for Workers with Chronic Health Conditions: Construct Development and Scale Validation. Occup Health Sci. 2020;4:445–470. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sexton JB, Schwartz SP, Chadwick WA, et al. The associations between work-life balance behaviours, teamwork climate and safety climate: cross-sectional survey introducing the work-life climate scale, psychometric properties, benchmarking data and future directions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26:632–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffmeister K, Gibbons A, Schwatka N, Rosecrance J. Ergonomics Climate Assessment: A measure of operational performance and employee well-being. Appl Ergon. 2015;50:160–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kava CM, Passey D, Harris JR, Chan KCG, Hannon PA. The Workplace Support for Health Scale: Reliability and Validity of a Brief Scale to Measure Employee Perceptions of Wellness. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35:179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Della LJ, DeJoy DM, Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ, Wilson MG. Assessing management support for worksite health promotion: psychometric analysis of the leading by example (LBE) instrument. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:359–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Della LJ, DeJoy DM, Mitchell SG, Goetzel RZ, Roemer EC, Wilson MG. Management support of workplace health promotion: field test of the leading by example tool. Am J Health Promot. 2010;25:138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark CM, Sattler VP, Barbosa-Leiker C. Development and Testing of the Healthy Work Environment Inventory: A Reliable Tool for Assessing Work Environment Health and Satisfaction. J Nurs Educ. 2016;55:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwon Y, Marzec ML, Edington DW. Development and validity of a scale to measure workplace culture of health. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57:571–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedberg MW, Rodriguez HP, Martsolf GR, Edelen MO, Vargas Bustamante A. Measuring Workplace Climate in Community Clinics and Health Centers. Med Care. 2016;54:944–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sha S, Aloba O, Watts-Isley J, McCoy T. The Adaption of the Work Environment Survey for Public Health Nurses. West J Nurs Res. 2021;43:834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hinsley KE, Marshall AC, Hurtig MH, et al. Monitoring the health of the work environment with a daily assessment tool: the REAL - Relative Environment Assessment Lens - indicator. Cardiol Young. 2016;26:1082–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.CDC. CDC National Healthy Worksite: CDC NHWP Health and Safety Climate Survey (INPUTS) Available from: https://www.healthybydesignyellowstone.org/wp-content/uploads/CDC-NHWP-Health-and-Safety-Climate-Survey.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 66.Lewis RJ, Friedlander BR, Bhojani FA, Schorr WP, Salatich PG, Lawhorn EG. Reliability and validity of an occupational health history questionnaire. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McGonagle A, Roebuck A, Diebel H, Aqwa J, Fragoso Z, Stoddart S. Anticipated work discrimination scale: a chronic illness application. J Manage Psychol. 2016;31:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Monnot MJ. Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal With Supervisor (RISCS): Scale Development and Conditional Model of Meaningfulness at Work. Psych-Man J. 2016;19:61–90. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prasad M, Wahlqvist P, Shikiar R, Shih YCT. A review of self-report instruments measuring health-related work productivity - A patient-reported outcomes perspective. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:225–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loeppke R, Hymel PA, Lofland JH, et al. Health-related Workplace productivity measurement: General and migraine-specific recommendations from the ACOEM expert panel. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Terry PE, Xi M. An examination of presenteeism measures: the association of three scoring methods with health, work life, and consumer activation. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13:297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, et al. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:156–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gawlicki MC, Reilly MC, Popielnicki A, Reilly K. Linguistic validation of the US Spanish work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire, general health version. Value Health. 2006;9:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koopman C, Pelletier KR, Murray JF, et al. Stanford presenteeism scale: health status and employee productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shikiar R, Halpern MT, Rentz AM, Khan ZM. Development of the Health and Work Questionnaire (HWQ): an instrument for assessing workplace productivity in relation to worker health. Work. 2004;22:219–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.AlHeresh R, LaValley MP, Coster W, Keysor JJ. Construct Validity and Scoring Methods of the World Health Organization: Health and Work Performance Questionnaire Among Workers With Arthritis and Rheumatological Conditions. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:e112–e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ozminkowski RJ, Goetzel RZ, Long SR. A validity analysis of the Work Productivity Short Inventory (WPSI) instrument measuring employee health and productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:1183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ, Long SR. Development and reliability analysis of the Work Productivity Short Inventory (WPSI) instrument measuring employee health and productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:743–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trotter VK, Lambert MJ, Burlingame GM, et al. Measuring work productivity with a mental health self-report measure. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:739–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riley MR, Mohr DC, Waddimba AC. The reliability and validity of three-item screening measures for burnout: Evidence from group-employed health care practitioners in upstate New York. Stress Health. 2018;34:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karpinski AC, Dzurec LC, Fitzgerald SM, Bromley GE, Meyers TW. Examining the factor structure of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) as a measure of victim response to the psychological pain of subtle workplace bullying. J Nurs Meas. 2013;21:264–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ting L, Jacobson JM, Sanders S, Bride BE, Harrington D. The Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS): Confirmatory Factor Analyses with a National Sample of Mental Health Social Workers. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2005;11:177–194. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marfeo EE, Ni P, Haley SM, et al. Scale refinement and initial evaluation of a behavioral health function measurement tool for work disability evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang E, Cohen J, Koethe B, Smith K, Bir A. Measuring job satisfaction among healthcare staff in the United States: a confirmatory factor analysis of the Satisfaction of Employees in Health Care (SEHC) survey. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morgan GB, Sherloch JJ, Ritchie WJ. Job satisfaction in the home health care context: validating a customized instrument for application. J Healthc Manag. 2010;55:11–23; discussion 23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Daniels K Measures of five aspects of affective well-being at work. Human Relations. 2000;53:275–294. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Russell E, Daniels K. Measuring affective well-being at work using short-form scales: Implications for affective structures and participant instructions. Hum Relat. 2018;71:1478–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peters SE, Gundersen DA, Katz JN, Sorensen G, Wagner GR. Thriving from Work Questionnaire: Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the long and short form questionnaires. Am J Ind Med. 2023;66:281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peters SE, Sorensen G, Katz JN, Gundersen DA, Wagner GR. Thriving from Work: Conceptualization and Measurement. Int J Environ Res Public Health;18 . Epub ahead of print 2021. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18137196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zheng XM, Zhu WC, Zhao HX, Zhang C. Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J Organ Behav. 2015;36:621–644. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Renshaw TL, Long ACJ, Cook CR. Assessing teachers’ positive psychological functioning at work: Development and validation of the Teacher Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. Sch Psychol Q. 2015;30:289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parker GB, Hyett MP. Measurement of well-being in the workplace: the development of the work well-being questionnaire. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eaton JL, Mohr DC, Hodgson MJ, McPhaul KM. Development and Validation of the Work-Related Well-Being Index: Analysis of the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bartels AL, Peterson SJ, Reina CS. Understanding well-being at work: Development and validation of the eudaimonic workplace well-being scale. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Warr P The measurement of well‐being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1990;63:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Van Katwyk PT, Fox S, Spector PE, Kelloway EK. Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5:219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rehder KJ, Adair KC, Hadley A, et al. Associations Between a New Disruptive Behaviors Scale and Teamwork, Patient Safety, Work-Life Balance, Burnout, and Depression. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020;46:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fowles JB, Terry P, Xi M, Hibbard J, Bloom CT, Harvey L. Measuring self-management of patients’ and employees’ health: further validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) based on its relation to employee characteristics. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.DeArmond S, Smith AE, Wilson CL, Chen PY, Cigularov KP. Individual safety performance in the construction industry: development and validation of two short scales. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43:948–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sliter KA, Sliter MT. The Concise Physical Activity Questionnaire (CPAQ): Its Development, Validation, and Application to Firefighter Occupational Health. Int J Stress Manage. 2014;21:283–305. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Steege AL, Boiano JM, Sweeney MH. NIOSH health and safety practices survey of healthcare workers: training and awareness of employer safety procedures. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57:640–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kuykendall L, Lei X, Tay L, et al. Subjective quality of leisure & worker well-being: Validating measures & testing theory. J Vocat Behav. 2017;103:14–40. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Feuerstein M, Nicholas RA, Huang GD, Haufler AJ, Pransky G, Robertson M. Workstyle: development of a measure of response to work in those with upper extremity pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:87–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Geer LA, Anna D, Curbow B, et al. Survey assessment of worker dermal exposure and underlying behavioral determinants. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2007;4:809–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Geer LA, Curbow BA, Anna DH, Lees PS, Buckley TJ. Development of a questionnaire to assess worker knowledge, attitudes and perceptions underlying dermal exposure. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:209–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reece A, Yaden D, Kellerman G, et al. Mattering is an indicator of organizational health and employee success. J Posit Psychol. 2021;16:228–248. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhou SV, Lee P. Spirituality in the Context of Teams and Organizations: An Investigation of Boundary Conditions Using The Integration Profile Workplace Spirituality Measure. J Manag Spiritual Relig. 2023;20:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 108.CDC. National Healthy Worksite: CDC Employee Health Assessment (CAPTURE) Available from: https://healthyazworksites.org/assets/nhwp-capture-health-assessment-update.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chari R, Sauter SL, Petrun Sayers EL, Huang W, Fisher GG, Chang CC. Development of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Worker Well-Being Questionnaire. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64:707–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dugan AG, Namazi S, Cavallari JM, et al. Participatory survey design of a workforce health needs assessment for correctional supervisors. Am J Ind Med. 2021;64:414–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.University of California San Francisco, California Labor Lab. The California Work & Health Survey Available from: https://calaborlab.ucsf.edu/cwhs. 2025. Accessed January 17, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sherman BW, Lynch WD. Connecting the dots: examining the link between workforce health and business performance. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.CFIR Research Team-Center for Clinical Management Research. Qualitative Data – The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Available from: https://cfirguide.org/evaluation-design/qualitative-data/. 2025. Accessed January 17, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 114.CDC NIOSH. National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA), National Occupational Research Agenda for Healthy Work Design and Well-Being Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nora/councils/hwd/pdfs/Final-National-Occupational-Research-Agenda-for-HWD_January-2020.pdf. 2020. Accessed January 17, 2025.

- 115.Howard J, Schulte PS. Managing workplace AI risks and the future of work. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2024;67:980–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition. Evaluating stress: A book of resources. Lanham, MD, US: Scarecrow Education; 1997. p. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Readers should contact the corresponding author for any data requests associated with this article.