Abstract

Hemithioindigo (HTI) photoswitches exhibit robust photoisomerization under visible light and relatively high thermal bistability. In this work, we report various modifications of the HTI core, namely the introduction of aldehydes and carboxylic acids at the para position of the stilbene fragment with different oxidation states of the sulfur center, and the incorporation of a Schiff base moiety. These modifications allowed tuning of the absorption properties, quantum yields of isomerization, and thermal stability of the metastable E‐isomers. Notably, the formyl‐ and carboxyl‐substituted HTI switches achieved high yields of isomerization under visible light in various solvents, while sulfur oxidation enhanced quantum yields but reduced photochromism. Schiff base formation led to red‐shifted absorption and increased thermal stability. Finally, by leveraging the carboxyl substituents, we incorporated an HTI chromophore into the NU‐1000 metal‐organic framework (MOF), and demonstrated solid‐state photoisomerization. These findings highlight key structural modifications that expand the applicability of HTI photoswitches for molecular switching in solution and solid‐state environments.

Keywords: hemithioindigo, isomerization, metal‐organic frameworks, photochromism, photoswitches

The core of an HTI photoswitch with different oxidation states of the sulfur heteroatom was modified by introducing aldehydes and carboxylic acid substituents for tailored absorption, quantum yields, and thermal stability. Notably, the substituted HTIs enabled high isomerization yields, while sulfur oxidation enhanced quantum yields but reduces photochromism. Solid‐state photoisomerization was demonstrated on an HTI that was incorporated into a MOF.

1. Introduction

Photoswitches are molecules that reversibly convert between two or more isomeric states upon exposure to light, resulting in significant changes in their physical and chemical properties.[ 1 ] This key feature imparts high versatility to photoswitches, as the light stimulus allows high spatiotemporal control over the photochemical process. Numerous photoactive compounds with diverse switching mechanisms have been extensively studied and applied, such as azobenzenes,[ 2 ] diarylethenes,[ 3 ] stiff‐stilbenes,[ 4 ] spiropyrans,[ 5 ] oxazines,[ 6 ] overcrowded alkenes,[ 7 , 8 ] and Donor‐Acceptor Stenhouse Adducts (DASAs).[ 9 , 10 ] Each offers unique advantages for specific uses, including surface functionalization,[ 11 ] optical data storage,[ 12 ] and molecular motors.[ 13 ] Moreover, incorporating photoswitches into materials[ 14 ] enables remote optical control,[ 15 ] unlocking a wide range of applications across diverse fields such as material science,[ 16 , 17 ] supramolecular chemistry,[ 18 ] catalysis,[ 19 ] biology,[ 20 , 21 ] and pharmacology.[ 22 , 23 ]

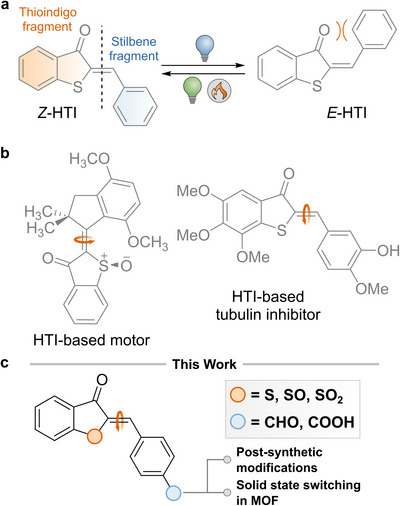

Among all the different classes of photoswitches, hemithioindigo (HTI) chromophores, or thioaurones, were first reported in the early 20th century by Friedländer[ 24 ] and constitute an emerging class of indigoid photochromes that have garnered significant research attention in recent years. HTIs can be considered the combination of a thioindigo fragment and a stilbene fragment (Figure 1a). Isomerization about the central double bond is triggered upon exposure to light, which enables switching between the Z‐ and E‐isomers, where the former commonly is the thermodynamically stable form.[ 25 ] HTIs exhibit robust photochemical switching under visible light and possess high thermal bistability.[ 25 ] Photoisomerization significantly alters the absorption properties, polarity, as well as dipole moment, enabling a wide range of applications.[ 26 ] For instance, Dube and co‐workers have designed an HTI‐based molecular motor that undergoes unidirectional rotation under visible‐light irradiation (Figure 1b),[ 27 , 28 , 29 ] while an HTI‐based compound has been developed as a photoswitchable tubulin inhibitor that allows visible light‐controlled regulation of mitosis in vivo.[ 30 ] Further exploration of functional groups has revealed the advantageous qualities of heterocycles[ 31 ] and peri‐anthracenethioindigo scaffolds,[ 32 ] the latter of which enable efficient photoswitching under red light and near‐infrared illumination.

Figure 1.

a) Structure of hemithioindigo (HTI) and its Z/E‐isomerization; b) The first HTI‐based molecular motor and a visible‐light‐responsive tubulin inhibitor; c) Hemithioinidigo photoswitches investigated in this study.

The optical, thermodynamic, and kinetic properties of HTIs are readily tuned by modifying the substitution pattern on the stilbene fragment.[ 33 ] The incorporation of electron‐donating groups at the para position enhances the push‐pull effect across the double bond, with the carbonyl group in the hemithioindigo fragment acting as the electron‐accepting moiety. Such modification leads to a bathochromic shift of the absorption bands and increased switching efficiencies.[ 34 ] Additionally, the electron‐accepting character of the hemithioindigo fragment can be enhanced by oxidation of the sulfur atom to the corresponding sulfoxide or sulfone.[ 35 ]

Recent studies on molecular motors based on overcrowded alkenes have shown that the addition of a formyl group directly conjugated with the double bond results in a red‐shift of the absorption maximum, as well as enhanced absorptivity and an increase in the quantum yield (QY) of photoisomerization, leading to faster photoisomerization and a nearly quantitative distribution of the photostationary state.[ 36 , 37 ] Furthermore, formyl and carboxyl groups are highly attractive due to their potential for further chemical derivatization, enabling the integration of HTIs into diverse platforms.[ 38 ]

The aim of this work is to investigate the effect of the aforementioned functional groups, placed at the para‐position of the stilbene fragment, on the photophysical and photochemical properties of HTI switches. While various HTI derivatives with a wide range of substituents have been reported in the literature,[ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 39 ] the impact of functional groups capable of extending conjugation in this specific position has, to the best of our knowledge, not been extensively explored.

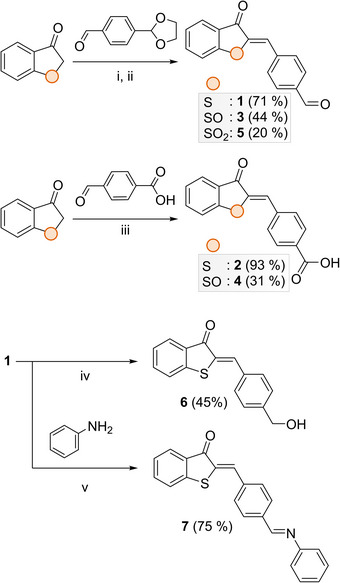

Thus, we synthesized HTI derivatives 1 and 2 containing a formyl and a carboxyl group, respectively (Figure 2). We further investigated the influence of the oxidation state of the sulfur atom by preparing the sulfoxide (3, 4) and sulfone (5) derivatives. Additionally, we pursued two strategies to explore the electronic and structural effects of functionalization at the para‐position. First, we modified the formyl moiety of 1 to obtain the hydroxymethyl derivative (6), which introduced an inductive effect, and a Schiff base (7), which enhances conjugation through resonance. Second, we evaluated the potential of the para‐carboxyl group for integration into spatially organized platforms, such as metal‐organic frameworks (MOFs),[ 40 ] for which we demonstrate that photoisomerization of HTI is effectively achieved in the solid state.

Figure 2.

Synthetic procedure for HTI switches 1–7. (i) piperidine (cat.), ethanol or toluene, room temperature or reflux, 3–5 hours; (ii) 0.5 N HCl; (iii) sodium triacetoxyborohydride (STAB, 1.0 eq.), 1,2‐dichloroethane (DCE), room temperature, 2.5 hours; (iv) molecular sieves, ethanol, 40 °C, overnight.

2. Results and Discussion

The key step in the synthesis of HTI compounds involved a one‐step Knoevenagel condensation between 1‐benzothiophen‐3(2H)‐one and the appropriately substituted benzaldehydes. The synthesis of 1‐benzothiophen‐3(2H)‐one was achieved by treating thiophenoxyacetic acid with an excess of triflic acid (TfOH), resulting in an improvement in yield (60%) compared to previously reported methods using AlCl3.[ 29 , 41 , 42 ] The subsequent condensation reaction was carried out using piperidine as the base in toluene or ethanol, heated or at room temperature (Figure 2).[ 35 , 43 ] Sulfoxide derivatives 3 and 4, along with sulfone 5, were synthesized from the corresponding oxide and dioxide of 1‐benzothiophen‐3(2H)‐one, previously obtained under different oxidative conditions (see Supporting Information for details).[ 35 , 44 ] To further exemplify the versatility of the formyl group, we synthesized alcohol 6 in 45% yield under mild reductive conditions, starting from 1. Additionally, the synthesis of 7 was straightforwardly carried out using aniline in ethanol in the presence of molecular sieves.[ 45 ]Following the synthesis of the target compounds, we systematically investigated their (photo)chemical properties (Table 1). These studies were conducted in various solvents, namely protic (methanol), nonpolar (toluene), and polar aprotic (acetonitrile). In the ground state, the Z‐configuration of this type of photoswitch is generally the thermodynamically favored isomer.[ 46 ]

Table 1.

Comparison of the physical and photochemical properties of HTIs determined in different solvents.

| [M−1·cm−1]; λmax | QY [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTI | Solvent | εZ | εE | %E at PSS | Z→E | E→Z | ΔG‡ E / Z [kcal·mol−1] † |

| 1 | MeCN |

13,600; 317 5500; 438 |

14,200; 312 2800; 460 |

93% (455 nm) | 57.0 ± 0.3 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 21.9 |

| toluene |

10,900; 319 5500; 444 |

12,900; 315 3700; 472 |

66% (455 nm) | 41.4 ± 0.3 | 57.1± 0.4 | 23.2 | |

| MeOH |

17,400; 316 5700: 436 |

18,600; 309 3300; 457 |

70% (455 nm) | 23.7 ± 0.2 | 14.7 ± 0.1 | 21.8 | |

| 65% (395 nm) | |||||||

| 2 | MeCN |

16,600; 307 8500; 436 |

17,800; 306 5000; 455 |

87% (455 nm) | 39.1 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 22.5 |

| toluene |

8600; 308 5600; 441 |

10,500; 309 3900; 460 |

82% (455 nm) | 59.1 ± 0.5 | 18.8 ± 0.2 | 28.1 [c] | |

| MeOH |

11,900; 319 7500; 436 |

12,700; 309 4200; 449 |

77% (455 nm) | 24.9 ± 0.1 | 10.6 ± 0.1 | 24.8 [d] | |

| 3 | MeCN | 12,400; 326 | 10,800; 325 | 39% (340 nm) | 73.8 ± 0.1 | 31.1 ± 0.2 | 20.6 |

| 25% (310 nm) | |||||||

| toluene | 21 700; 334 | 19,000; 333 | 26% (365 nm) | 36.7 ± 0.1 | 52.0 ± 0.2 | 23.7 | |

| 45% (340 nm) | |||||||

| MeOH | 15,800; 331 | 9100; 332 | 38% (340 nm) | 10.6 ± 1.2 | 23.3 ± 2.6 | 20.4 | |

| 42% (365 nm) [a] | |||||||

| 4 [b] | MeCN | 13,000; 325 | – | – | – | – | |

| toluene | 2800; 331 | – | – | – | – | ||

| MeOH | 13,800; 338 | – | – | – | – | ||

| 5 | MeCN | 15,000; 331 | 12,900; 335 | 52% (340 nm) | 70.8 ± 0.1 | 28.5 ± 0.1 | 20.7 |

| toluene | 17,000; 338 | 15,100; 342 | 75% (340 nm) | 36.1 ± 0.1 | 11.8 ± 0.1 | 21.3 | |

| MeOH [b] | 21,300; 335 | – | – | – | – | 20.3 | |

| 6 | MeCN |

19,700; 319 13,500; 430 |

18,400; 324 7900; 455 |

64% (455 nm) | 20.5 ± 0.1 | 12.0 ± 0.1 | 25.6 |

| toluene |

19,500; 320 14,700; 435 |

19,000; 327 8700; 456 |

88% (455 nm) | 26.7 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 30.2 [e] | |

| MeOH |

12,500; 329 8800; 433 |

12,000; 324 6200; 467 |

43% (455 nm) | 12.6 ± 0.1 | 23.8 ± 0.1 | 25.2 [d] | |

| 7 | toluene |

25,700; 327 25,700; 452 |

32,600; 327 19,000; 475 |

50% (455 nm) | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 16.6 ± 0.1 | 24.4 |

A mixture of the E isomer and photodecomposition products was obtained;

Photodecomposition of the starting material upon 340 and 365 nm light was observed;

Measured at 353 K;

Measured at 323 K;

Measured at 373 K.

Values obtained at 293 K unless otherwise specified.

We validated this energetic preference for the compounds reported in this work by DFT calculations (Figures S53 and 54). We found that the metastable states of HTI‐1,2, and 6 are ca. 6 kcal/mol higher in energy than the corresponding Z isomer. In contrast, oxidation of the HTI core reduces the energy difference between the two isomers, with the metastable E‐isomer being only 3 kcal/mol and 2 kcal/mol higher than the Z‐isomer for 3 and 5, respectively.

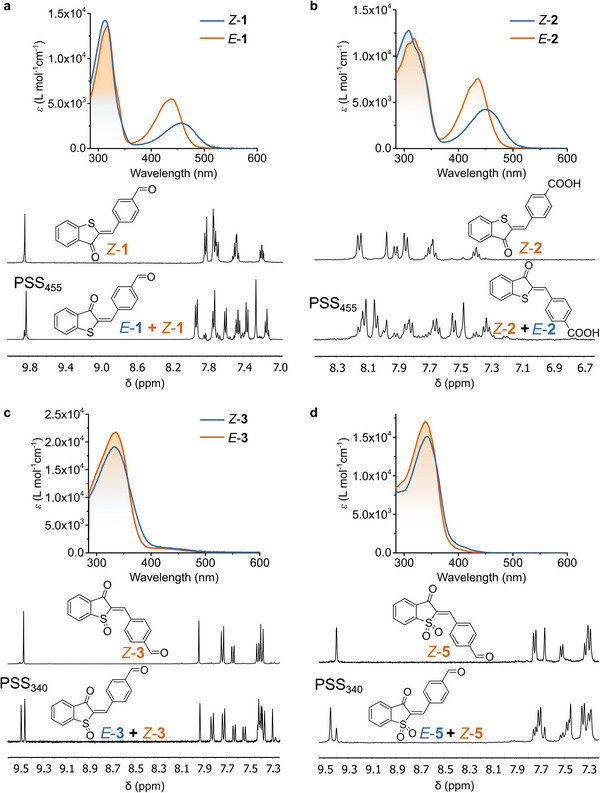

Subsequently, we performed photoisomerization experiments by irradiating the samples at specific wavelengths until the photostationary state (PSS) was reached, at which point no further changes in the isomeric composition were observed. Both UV‐Vis and ¹H NMR spectroscopy were employed to determine the extent of switching at the PSS as well as the molar absorption coefficients of the E‐isomers (Figures 3 and S7–S12).

Figure 3.

Photochemical properties of HTIs 1, 2, 3, and 5 analyzed by UV‐Vis and 1H NMR spectroscopy at 293 K. a) E/Z‐1 in MeCN; b) E/Z‐2 in methanol; c) E/Z‐3 in toluene and; d) E/Z‐5 in toluene. The upper panel presents the experimentally determined molar absorption coefficients (ε) of the pure Z‐isomer (red) and the coefficients for the pure E‐isomer (blue) retrieved using the photostationary distribution obtained by 1H NMR. The lower panel shows the aromatic region of the 1H NMR spectra before (top) and after (bottom) irradiation.

Remarkably, the nonoxidized HTI derivatives (1, 2, and 6) exhibit absorption bands at around 430–452 nm, whereas the oxidized HTI derivatives (3, 4, and 5) feature blue‐shifted bands at around 331–338 nm. With the exception of 4, a solvent‐dependent trend was observed for all HTI derivatives: the absorption maximum shifted bathochromically with the decrease of solvent polarity, with toluene showing the most red‐shifted bands, followed by methanol and acetonitrile—an effect consistent with positive solvatochromism. Furthermore, the molar absorption coefficients (ε) of the Z‐isomers were higher in polar solvents (MeOH and MeCN) compared to toluene (see Table 1). Interestingly, 3 was an exception to this trend, exhibiting its highest ε value in toluene.

We further confirmed this distinct absorption behavior between nonoxidized and oxidized HTI derivatives by photoisomerization studies using UV‐Vis absorption spectroscopy. Upon irradiation, the nonoxidized HTI derivatives (1, 2, and 6) exhibited isomerization with clear band shifts (13‐28 nm) regardless of the functional group or the solvent. In contrast, the oxidized HTIs (3 and 5) exhibited minimal spectral changes during irradiation. However, their isomerization was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The electronic effects of sulfoxide and sulfone oxidation states in these chromophores appear remarkably similar, as described by Dube and co‐workers.[ 35 ]

This photoisomerization process was further investigated by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Upon irradiation at 455 nm, HTIs 1 and 2 showed moderate‐to‐high conversion to the E‐isomer in all solvents, in particular in MeCN‐d3 (93 and 87% at the PSS, respectively, Figures S14 and S16). Additionally, 1 displayed reversible photoisomerization: upon subsequent irradiation at 505 nm, 76% of the Z‐isomer was recovered (Figure S14). As noted above, the oxidized HTI derivatives (3 and 5) exhibited minimal spectral changes during irradiation followed by UV‐Vis absorption spectroscopy, which is reflected in the relatively low conversion to the E‐isomer observed in the 1H NMR irradiation experiments. In general, photostationary distribution values tend to be higher when the absorption spectra of Z‐ and E‐isomers overlap less. At the PSS in MeCN, 39% and 53% of the E‐isomer was obtained for 3 and 5, respectively (Figures S20 and S23), with similar conversions in MeOH (42%), though the latter was accompanied by photodegradation during prolonged irradiation (Figure S21). We do not observe photoisomerization for p‐carboxy sulfoxide derivative 4, in either MeCN or MeOH, and photodecomposition occurred in toluene after just 10 minutes of irradiation.

Having determined the E/Z ratios at the PSS from 1H NMR spectroscopy, and the molar absorption coefficients and change in concentrations during irradiation from UV‐Vis absorption spectroscopy measurements, we successfully calculated the quantum yields (QYs) of photoisomerization (see Table 1) using a recently developed experimental setup in our group based on fiber‐coupled LEDs, a calibrated thermopile detector for accurate photon flux measurements, and a fiber‐coupled UV‐Vis spectrometer, together with our recently developed GUI (see Supporting Information for details).[ 47 , 48 ]

Introducing a formyl group into the stilbene fragment, that is, 1, resulted in quantum yield values that varied significantly with the solvent, reaching a maximum of 57% in MeCN (see Table 1). Notably, the highest reported quantum yield for unsubstituted HTI is 23% in halogenated solvents,[ 25 ] and the highest reported for any HTI‐based photoswitches belongs to a 4‐imidazole derivative, with 69% for the forward Z→E and 43% for the backward E→Z photoisomerization.[ 31 ] Indeed, the incorporation of a formyl group results in an improvement in photoisomerization efficiency, highlighting the effect of the extension of conjugation by an electron‐withdrawing group at the para position. This behavior is consistent with studies conducted in the field of molecular motors based on overcrowded alkenes, where formylation has been proven to be a useful strategy for enhancing photoisomerization performance, resulting in red‐shifted excitation wavelengths, increased quantum yields, and improved photostationary state distributions.[ 36 , 37 ] A tentative explanation for this behavior could be related to the extension of the π‐system due to the addition of the formyl group, which could also impart additional vibrational modes to the excited state dynamics that can bias the efficiency of the process.[ 49 ]

Importantly, while the authors of the aforementioned work performed all measurements in dichloromethane, we observe a significant variation of the quantum yield depending on the employed solvent. Interestingly, the highest QYs for compounds 1, 3, and 5 were consistently observed in MeCN, the most polar solvent in our study. This trend appears to correlate with solvent polarity, particularly with the dielectric constant of the medium (MeCN>MeOH>toluene), suggesting that a more polar environment may favor the isomerization, possibly limiting alternative nonproductive pathways in HTI.

Furthermore, we investigated the influence of the oxidation state of the sulfur atom on the quantum yield of isomerization. Interestingly, both the p‐formyl sulfoxide 3 and sulfone 5 derivatives exhibited an increase in QY (74 and 70%), respectively, compared to 1 in MeCN (57%). However, the same increase is not observed in the other solvents, toluene nor MeOH, in which the values for the QY are within the same range for 1, 3, and 5 (see Table 1).

Finally, the thermal behavior of the HTIs was investigated by monitoring the thermal back‐isomerization of the E‐isomer to the Z form in the dark at different temperatures to obtain the corresponding Gibbs energies of activation (ΔG‡ ) (see Supporting Information for more details). A general trend was observed regarding the thermal stability of the E‐isomer: polar solvents such as MeOH and MeCN resulted in lower ΔG‡ values and shorter half‐lives for the metastable E‐isomers, whereas toluene led to higher energy barriers, indicating enhanced thermal stability. The stability of the E‐isomer is therefore strongly influenced by solvent polarity, with higher polarity accelerating the thermal isomerization process. For instance, compound 1 showed a ΔG‡ of 21.9 kcal·mol−1 in MeCN compared to 23.2 kcal·mol−1 in toluene at 20 °C, corresponding to an almost 10‐fold increase in half‐life. This solvent‐dependent behavior has also been clearly demonstrated in prior research on structurally modified HTI compounds, where increased solvent polarity promoted faster thermal back‐isomerization rates.[ 31 , 50 , 51 ]

On the other hand, comparison of 1 with the oxidized derivatives 3 and 5 shows a small trend toward lower thermal barriers upon oxidation of the sulfur atom. However, in toluene, we did not observe such a trend and all values are approximately the same. As previously stated, the p‐carboxy sulfoxide derivative 4 undergoes decomposition during irradiation, preventing a PSS from being reached.

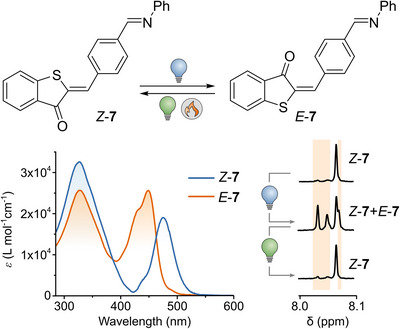

To investigate the impact of further modification of the carbonyl group on the photophysical properties of HTI, we explored the imine derivative 7. This chemical transformation modulates the electronic structure and involves forming a Schiff base, which is a key reaction in biological environments, potentially enabling applications in protein cavity labeling.[ 52 , 53 ] We were able to study 7 only in toluene since partial hydrolysis occurred in MeCN and MeOH. Notably, 7 exhibits the most red‐shifted absorption band of all derivatives reported here, along with relatively high molar absorptivity.

Upon irradiation with blue light (455 nm), the PSS contained 50% of the E‐isomer (Figure 4). Subsequently, upon irradiation with green light (505 nm), 95% of the stable Z‐form (Figure S27) was rapidly recovered. This light‐controlled modulation between two defined isomeric states—enabled by visible light and a pronounced thermal bistability (ΔG‡ of 24.4 kcal·mol−1)—demonstrates the potential of 7 for reversible switching applications.

Figure 4.

Isomerization of 7. Bottom left: molar absorption coefficients (ε) of 7 (toluene, 293 K); bottom right: 1H NMR spectra of 7 before (top) and after irradiation with 455 nm (middle) and after subsequent irradiation with 505 nm (bottom) in toluene‐d8.

The incorporation of a Schiff‐base moiety into the structure of HTI could introduce an alternative photochemical pathway, namely photoinduced C═N isomerization, which may account for the observed reduction in quantum yield to 5% for the photoisomerization of the C═C bond.[ 54 ] It is important to note that we did not detect any photoisomerization of the C═N bond within the timescale of our UV‐Vis and 1H NMR measurements, most likely due to the low thermal stability of the corresponding metastable state, which is known to have half‐lives ranging from milliseconds to seconds.[ 45 , 55 ]

Many photoswitches undergo efficient isomerization in solution but face steric hindrance in the solid state.[ 56 ] To overcome this issue, molecular switches have been immobilized in metal‐organic frameworks (MOFs),[ 57 ] which provide a structurally well‐defined, porous matrix that allows for free molecular motion, for example, for spiropyrans,[ 58 , 59 , 60 ] spirooxazines,[ 61 ] diarylethenes,[ 62 ] and overcrowded alkenes.[ 63 ] We, therefore, investigated the confinement of 2 within NU‐1000, a zirconium‐based MOF (Zr‐MOF), chosen for its proven compatibility with guest molecules, its photostability, and its spacious pore size,[ 61 , 64 ] which provides ample room for double bond isomerization without compromising the structural integrity of the framework. The carboxyl group of 2 serves as an anchor point for post‐synthetic coordination to the coordinatively unsaturated Zr(IV) clusters that are integral to NU‐1000.

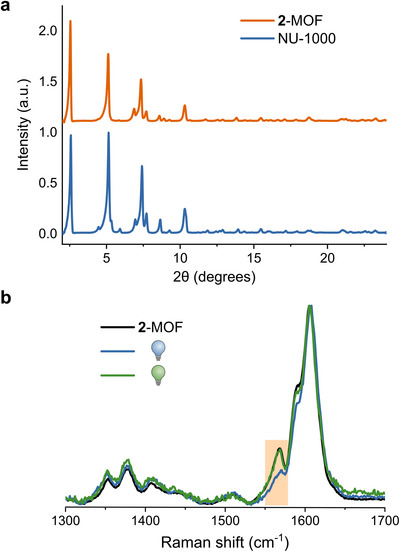

NU‐1000 was synthesized following established procedures in the literature.[ 65 ] Subsequently, 2 was incorporated within the MOF by means of ligand exchange (see the Supporting Information for details), which was confirmed via powder X‐ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis (Figure 5a), and Raman and IR spectroscopy (Figure S51). The structural integrity of the MOF after functionalization was verified by the close resemblance of the PXRD pattern of 2‐MOF to the one of the parent MOF, which maintained the peak positions while exhibiting slight variations in peak intensities. These variations further indicate the successful incorporation of HTI into NU‐1000.[ 66 ]

Figure 5.

(a) PXRD pattern of the free NU‐1000 (blue) and 2‐MOF (orange). (b) Raman spectra (λexc 785 nm) of 2‐MOF before (black), after irradiation with 455 nm (blue), and after subsequent irradiation with 505 nm (green).

Photoswitching of 2‐MOF was followed by solid‐state Raman spectroscopy at 785 nm (Figure 5b). Irradiation of 2‐MOF with 455 nm resulted in the decrease in intensity of the band at 1567 cm−1, and subsequent irradiation at 505 nm successfully restored the band to nearly its original intensity, indicating a reversible photochemical process. The observed experimental changes are consistent with computational predictions of the difference between the Raman spectra of the stable Z‐isomer and the metastable E‐isomer (Figures S51 and S55). In contrast, the free photoswitch 2 showed no spectral changes upon irradiation in solid state (Figure S52).

3. Conclusion

We synthesized a new series of hemithioindigo derivatives with formyl and carboxylate substituents at the para position of the stilbene fragment. Additionally, we investigated the influence of the oxidation state of the sulfur atom on the photophysical and photochemical properties. The incorporation of electron‐withdrawing and π‐conjugation‐extending groups, such as the formyl group, combined with oxidation of the sulfur atom, enhanced the quantum efficiency for forward isomerization. Furthermore, Schiff base formation in derivative 7 induced a red‐shift in absorption as well as improved thermal bistability. Finally, we successfully incorporated an HTI photoswitch into a metal‐organic framework, enabling solid‐state photoisomerization and highlighting the potential of HTI photoswitches in materials science.

Supporting Information

The authors have cited additional references within the Supporting Information.[ 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 ]

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

S. C. thanks Swedish Vetenskapsrådet for a Starting Grant (2021‐05414) Stiftelsen Lars Hiertas Minne (FO2022‐0139), We thank the Carl‐Trygger Foundation (CTS 22:2212 to M.I.Q.), the Wenner‐Gren Stiftelserna (UPD2022‐0079 to J.D.S.), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW 2019.0071 to A. K.), and the Göran Gustafsson Foundation for postdoctoral stipends. S. O. acknowledges funding from the Swedish Research Council (2023‐03395). We thank Jun.‐Prof. Dr. Nadja A. Simeth from the Institute of Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry, Georg‐August‐University in Göttingen for the HRMS measurements. The computations were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS) at the Tetralith cluster (NSC in Linköping, thanks to the NAISS 2024/5‐570 medium and 2024/22‐844 small compute projects) partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. 2022‐06725.

Matías I. Quindt and Taegeun Jo contributed equally.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1. Pianowski Z. L., Ed., Molecular Photoswitches: Chemistry, Properties, and Applications, 2 Volume Set, Wiley, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crespi S., Simeth N. A., König B., Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 133. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Irie M., Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 617. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villarón D., Wezenberg S. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kortekaas L., Browne W. R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar A., Sahoo P. R., Kathuria I., Prakash K., Kumar S., J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2023, 438, 114541. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feringa B. L., Van Delden R. A., Koumura N., Geertsema E. M., Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feringa B. L., Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Helmy S., Oh S., Leibfarth F. A., Hawker C. J., Read De Alaniz J., J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mallo N., Foley E. D., Iranmanesh H., Kennedy A. D. W., Luis E. T., Ho J., Harper J. B., Beves J. E., Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 8242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferri V., Elbing M., Pace G., Dickey M. D., Zharnikov M., Samorì P., Mayor M., Rampi M. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Irie M., Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. Sci. Technol. Sect. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1993, 227, 263. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ter Wiel M. K. J., Van Delden R. A., Meetsma A., Feringa B. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klajn R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel P. D., Mikhailov I. A., Belfield K. D., Masunov A. E., Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2009, 109, 3711. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abellán G., Coronado E., Martí‐Gastaldo C., Ribera A., Jordá J. L., García H., Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 4156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neilson B. M., Bielawski C. W., ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen S., Costil R., Leung F. K.‐C., Feringa B. L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dorel R., Feringa B. L., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corbet B. P., Schlüter J. M., Cotroneo E. R., Crespi S., Simeth N. A., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202201140. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cordes T., Weinrich D., Kempa S., Riesselmann K., Herre S., Hoppmann C., Rück‐Braun K., Zinth W., Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 428, 167. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Velema W. A., Szymanski W., Feringa B. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Welleman I. M., Hoorens M. W. H., Feringa B. L., Boersma H. H., Szymański W., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 11672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friedländer P., Dtsch B., Chem. Ges. 1906, 39, 1060. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wiedbrauk S., Dube H., Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 4266. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zulfikri H., Koenis M. A. J., Lerch M. M., Di Donato M., Szymański W., Filippi C., Feringa B. L., Buma W. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilcken R., Schildhauer M., Rott F., Huber L. A., Guentner M., Thumser S., Hoffmann K., Oesterling S., De Vivie‐Riedle R., Riedle E., Dube H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huber L. A., Hoffmann K., Thumser S., Böcher N., Mayer P., Dube H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guentner M., Schildhauer M., Thumser S., Mayer P., Stephenson D., Mayer P. J., Dube H., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sailer A., Ermer F., Kraus Y., Lutter F. H., Donau C., Bremerich M., Ahlfeld J., Thorn‐Seshold O., Chem. Bio. Chem 2019, 20, 1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Josef V., Hampel F., Dube H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202210855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Köttner L., Ciekalski E., Dube H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leistner A.‐L., Pianowski Z. L., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202101271. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kink F., Collado M. P., Wiedbrauk S., Mayer P., Dube H., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 6237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Köttner L., Schildhauer M., Wiedbrauk S., Mayer P., Dube H., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 10712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sheng J., van Beek C. L. F., Stindt C. N., Danowski W., Jankowska J., Crespi S., Pooler D. R. S., Hilbers M. F., W. J. Buma B. L. Feringa Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sheng J., Danowski W., Sardjan A. S., Hou J., Crespi S., Ryabchun A., Domínguez M. P., Buma W. J., Browne W. R., Feringa B. L., Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Volarić J., Szymanski W., Simeth N. A., Feringa B. L., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thumser S., Köttner L., Hoffmann N., Mayer P., Dube H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 18251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li J., Kumar A., Johnson B. A., Ott S., Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hoorens M. W. H., Medved’ M., Laurent A. D., Di Donato M., Fanetti S., Slappendel L., Hilbers M., Feringa B. L., Jan Buma W., Szymanski W., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zweig J. E., Newhouse T. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gernet A., El Rhaz A., Jean L., Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gerwien A., Schildhauer M., Thumser S., Mayer P., Dube H., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu J., Kreimendahl L., Tao S., Anhalt O., Greenfield J. L., Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Réamonn L. S. S., O'Sullivan W. I., J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1977, 1, 1009. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Volker A., Steen J. D., Crespi S., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. “autoQY,” can be found under https://github.com/CrespiLab/autoQY, 2025.

- 49. Blanco‐Gonzalez A., Manathunga M., Yang X., Olivucci M., Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gernet A., El Rhaz A., Jean L., Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gernet A., Toursel L., Balivet L.‐M., Pagès L., Jean L., ChemPhotoChem 2025, 9, e202400261. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Blanco‐Lomas M., Samanta S., Campos P. J., Woolley G. A., Sampedro D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Palombo R., Barneschi L., Pedraza‐González L., Padula D., Schapiro I., Olivucci M., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Vliet S., Sheng J., Stindt C. N., Feringa B. L., Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Veselý D., Jančík J., Weiter M., Blasi D., Ivanova N., Krajčovič J., Georgiev A., J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2022, 430, 113994. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gui B., Meng Y., Xie Y., Du K., Sue A. C.‐H., Wang C., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, 1700388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rice A. M., Martin C. R., Galitskiy V. A., Berseneva A. A., Leith G. A., Shustova N. B., Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Garg S., Schwartz H., Kozlowska M., Kanj A. B., Müller K., Wenzel W., Ruschewitz U., Heinke L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thaggard G. C., Park K. C., Lim J., Maldeni Kankanamalage B. K. P., Haimerl J., Wilson G. R., McBride M. K., Forrester K. L., Adelson E. R., Arnold V. S., Wetthasinghe S. T., Rassolov V. A., Smith M. D., Sosnin D., Aprahamian I., Karmakar M., Bag S. K., Thakur A., Zhang M., Tang B. Z., Castaño J. A., Chaur M. N., Lerch M. M., Fischer R. A., Aizenberg J., Herges R., Lehn J.‐M., Shustova N. B., Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mostaghimi M., Hernandez H. P., Jiang Y., Wenzel W., Heinke L., Kozlowska M., Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thaggard G. C., Wilson G. R., Naik M., Quetel M. A., Lim J., Maldeni Kankanamalage B. K. P., Smith M. D., Shustova N. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 31746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Williams D. E., Martin C. R., Dolgopolova E. A., Swifton A., Godfrey D. C., Ejegbavwo O. A., Pellechia P. J., Smith M. D., Shustova N. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Danowski W., Van Leeuwen T., Abdolahzadeh S., Roke D., Browne W. R., Wezenberg S. J., Feringa B. L., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fei H., Pullen S., Wagner A., Ott S., Cohen S. M., Chem. Commun. 2014, 51, 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang T. C., Vermeulen N. A., Kim I. S., Martinson A. B. F., Stoddart J. F., Hupp J. T., Farha O. K., Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kung C.‐W., Otake K., Drout R. J., Goswami S., Farha O. K., Hupp J. T., Langmuir 2023, 39, 4936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Krell‐Jørgensen M., Zulfikri H., Bonnevie M. G., Bro F. S., Dohn A. O., Laraia L., Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gueye R., Pouget C., Champavier Y., Buxeraud J., Duroux J.‐L., Fagnère C., Comptes Rendus Chim 2014, 17, 443. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Arredondo‐Espinoza E. U., López‐Cortina S. T., Ramírez‐Cabrera M. A., Balderas‐Rentería I., Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 82, 327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fava E., Millet A., Nakajima M., Loescher S., Rueping M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bannwarth C., Caldeweyher E., Ehlert S., Hansen A., Pracht P., Seibert J., Spicher S., Grimme S., WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2021, 11, e1493. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pracht P., Bannwarth C., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Neese F., Wennmohs F., Becker U., Riplinger C., J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 224108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Neese F., WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Barone V., Cossi M., J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G., J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 5656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Weigend F., Ahlrichs R., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.