Abstract

Purpose

Cochlear implants (CIs) are an effective rehabilitation option for individuals with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). While genetic factors play a significant role in SNHL, the variability in CI outcomes remains unclear. This study evaluated short- and long-term CI outcomes in a large genotyped cohort and investigated correlations with genetic defects and their cochlear site-of-lesion.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center, cohort study included 220 subjects (127 females; 299 ears) with pathogenic variants identified in 31 different nuclear genes and in mitochondrial genes. Audiological outcomes were measured pre- and post-implantation. Cochlear site-of-lesion was categorized as pre-synaptic, post-synaptic, or mitochondrial, based on gene function or expression. Multiple regression analysis assessed factors influencing outcomes, including age at implantation, SNHL duration, hearing aid (HA) use, and cochlear site-of-lesion.

Results

Results showed a median phoneme score of 90%, with better outcomes in early implantation (≤ 6 years). Variability in outcomes was not linked to cochlear site-of-lesion, but to subject-specific factors, such as age at implantation, duration of SNHL, pre-implantation HA use, and CI experience. A model incorporating these subject-specific factors explained 19% of the total variance in outcomes. Poorer outcomes (phoneme scores < 70%) were more common in individuals with prolonged auditory deprivation or older age at implantation.

Conclusion

Genotyped CI recipients demonstrated excellent outcomes, with variability largely attributed to non-genetic factors. These findings show that cochlear implantation is a beneficial type of rehabilitation for most individuals with hereditary SNHL and underscore the importance of early implantation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10162-025-00987-0.

Keywords: Hereditary hearing loss, Genetics, Cochlear implantation outcomes, Clinical decision-making, Disease management

Introduction

Cochlear implantation is a successful type of rehabilitation for individuals with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), enhancing hearing, speech recognition, and quality of life [1]. Cochlear implant (CI) performance is influenced by factors like cochlear anatomy, age at implantation, duration of SNHL, residual hearing, and cognitive performance [2–5]. Lazard et al. identified nine factors accounting for 22% of the variance in CI outcomes [4]. The top four factors, accounting for 10% of the variance, include duration of severe/profound SNHL, age of onset of severe/profound HL, duration of CI experience, and etiology [3]. This leaves 78% of the variance unexplained, with other contributing factors yet to be identified.

Genetic factors significantly contribute to SNHL, with 50–70% of cases with early-onset SNHL having a genetic cause [6]. Genetic SNHL is highly heterogeneous, involving hundreds of genes encoding proteins with roles in various parts within the auditory pathway and beyond. It can be syndromic (~ 30% of cases) or non-syndromic (~ 70% of cases) [7]. Syndromic SNHL is linked to other conditions, like retinitis pigmentosa (i.e., Usher syndrome), goiter (i.e., Pendred syndrome), or pigmentary anomalies of the skin, hair and eyes (i.e., Waardenburg syndrome) [8]. In contrast, non-syndromic SNHL occurs without additional symptoms. Currently, about 150 genes are linked to non-syndromic SNHL, with many more associated with syndromic SNHL [9]. Causative variants are commonly found in subjects with congenital or early-onset SNHL, but this decreases significantly with later onset of SNHL [10].

Several studies have examined the genetic etiology in CI recipients [11–17], with causative variants most frequently reported in GJB2, SLC26 A4, TMPRSS3, and MYO7 A (Supplementary Table 1). These four genes are associated with congenital severe-to-profound SNHL, although TMPRSS3 is also linked to post-lingual onset high-frequency SNHL [18, 19]. While GJB2 and TMPRSS3 are associated with non-syndromic SNHL, MYO7 A and SLC26 A4 are linked to both non-syndromic (DFNA11/DFNB2 and DFNB4) and syndromic SNHL (Usher syndrome type 1b and Pendred syndrome).

Studies evaluating CI outcomes in genotyped recipients generally report favorable outcomes [13, 16, 19–21]. Yet, two studies noted significant variation in success rates based on genotype [16, 21]. Tropitzsch et al. observed that subjects with variants affecting the neural component of the cochlea had CI outcomes 35% worse than the overall median score [16], supporting the spiral ganglion hypothesis proposed by Eppsteiner et al. According to this hypothesis, variability in CI outcomes is linked to the health of the spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) and cochlear nerve [22]. SGNs transmit information from inner hair cells (IHCs) and outer hair cells (OHCs) [23–25] through their axons, which form the cochlear nerve [26, 27], to the cochlear nucleus [23, 24]. Because a CI directly stimulates the SGNs, poorer CI outcomes are anticipated when these neural components of the auditory pathway are affected. Conversely, good performance is anticipated when pre-synaptic structures, such as the organ of Corti and/or the stria vascularis, are affected [22].

This study aimed to evaluate CI outcomes in fully genotyped SNHL subjects within a large Dutch cohort. The primary objective was to assess CI outcomes at short- and long-term intervals. Additionally, we aimed to investigate whether the causative genetic defects contribute to the variability in CI outcomes by comparing outcomes between genes and cochlear site-of-lesions.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Population

This retrospective, observational cohort study evaluated CI performance in subjects with hereditary SNHL. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Medical Ethics Committee (METC) Eastern Netherlands. The requirement for signed informed consent was waived by the ethics committee because all data were collected, saved, analyzed, and reported anonymously. All genotyped individuals who underwent cochlear implantation at our center from January 2002 to March 2021 were identified. Subsequently, subjects were included in the study when they (1) had a confirmed genetic diagnosis based on monoallelic or biallelic (likely) pathogenic variants in, respectively, dominantly or recessively, inherited genes associated with SNHL; (2) underwent cochlear implantation after 2002; (3) had at least 1 year of follow-up for speech recognition measurements post-implantation. Individuals with syndromic SNHL and developmental delays that could potentially interfere with CI performance (e.g., CHARGE syndrome, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and Noonan syndrome) were excluded. Some subjects enrolled in this study were described in previous publications [28–34].

Data Collection

Demographic data were obtained by reviewing medical records, including sex, use of hearing aids (HA) prior to implantation, age at implantation, and type of implant and electrode used. Pre-implantation imaging was reviewed to assess inner ear anatomy, and the type of insertion was scored to evaluate surgical factors.

Genotype and Cochlear Site-of-Lesion

No new genetic analyses were performed for this study. Genotype data were obtained from previous genetic tests performed in the past two decades in a clinical setting. Subjects were seen in our outpatient clinic for genetic diagnostic screening and/or cochlear implantation. The type of genetic test varied per case, depending on the phenotype and family history, and included both targeted gene sequencing (< 2015) and/or whole-exome sequencing (WES, > 2014). The identified variant(s) in genes associated with SNHL, along with the corresponding protein change(s) and type of variant (truncating or missense), were documented from the original DNA-diagnostic laboratory reports. Given that variant classifications may have changed over time, all identified variants were re-classified according to the current ACMG-AMP variant classification guidelines by an experienced molecular lab specialist to ensure the most up-to-date categorization [35]. Subjects without monoallelic or biallelic (likely) pathogenic variants under these guidelines in dominantly or recessively inherited genes were excluded upon reclassification.

The cochlear site-of-lesion for the genes was determined by evaluating the encoded protein function as reported in current literature. If this was unknown, we considered the currently reported expression patterns (Table 1). Genes were classified into pre-synaptic (e.g., hair cells (HC), stria vascularis or tectorial membrane), post-synaptic (SGN or cochlear nerve), and mitochondrial groups. The mitochondrial group included subjects with pathogenic variants in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or genes mainly affecting mitochondrial function. Genes associated with both pre- and post-synaptic pathology were excluded from the cochlear site-of-lesion classification.

Table 1.

Pathogenic variants in the study population

| Gene | Transcript | cDNA | Protein | Type of mutation | Classification | Cochlear site-of-lesion | Group | References** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB | NM_001101.3 | c.547 C > T | p.(Arg183 Trp) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [36, 37] |

| ACTG1 | NM_001614.3 | c.151G > A | p.(Asp51 Asn) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [38] |

| ACTG1 | NM_001614.5 | c.833 C > T | p.(Thr278Ile) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| ADGRV1 | NM_032119.4 | c.8875 C > T | p.(Arg2959*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [39] |

| CDH23 | NM_022124.6 | c.3706 C > T | p.(Arg1236*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [40, 41] |

| CDH23 | NM_022124.6 | c.3955G > T | p.(Glu1319*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| CDH23 | NM_022124.6 | c.6050 - 9G > A | p.(Val2018fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| CLRN1 | NM_174878.3 | c.149_152 delinsTGTCCAAT | p.(Ser50fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | * | * | |

| CLRN1 | NM_174878.3 | c.528 T > G | p.(Tyr176*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | * | * | |

| COCH | NM_004086.2 | c.151 C > T | p.(Pro51Ser) | Missense | Pathogenic | * | Pre-synaptic | [42] |

| COCH | NM_004086.2 | c.263G > A | p.(Gly88Glu) | Missense | Pathogenic | * | Pre-synaptic | |

| EDNRB | NM_000115.5 | c.1195 - 1G > A | r.spl | Missense | Pathogenic | Stria vascularis | Pre-synaptic | [43] |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.− 23 + 1G > A | p.0 | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | [44] |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.139G > T | p.(Glu47*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.5 | c.223 C > T | p.(Arg75 Trp) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.229 T > C | p.(Trp77 Arg) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.5 | c.235 del | p.(Leu79fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.238 C > A | p.(Gln80Lys) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.35 del | p.(Gly12fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.427 C > T | p.(Arg143 Trp) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.5 | c.71G > A | p.(Trp24*) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.313_326 del | p.(Lys105fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.6 | c.32_45 del | p.(Gly11fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.5 | c.407 dup | p.(Tyr136*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB2 | NM_004004.5 | c.551G > A | p.(Arg184Gln) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| GJB6 | c.del(GJB6-D13S1830) | del(GJB6-D13S1830) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | ||

| LARS2 | NM_015340.3 | c.683G > A | p.(Arg228His) | Missense | Pathogenic | Mitochondrial | Mitochondrial | [45] |

| LARS2 | NM_015340.3 | c.880G > A | p.Glu294Lys | Missense | Pathogenic | Mitochondrial | Mitochondrial | |

| MITF | NM_000248.3 | c.649 del | p.(Arg217fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Stria vascularis | Pre-synaptic | [46] |

| MITF | NM_000248.3 | c.772 C > T | p.(Gln258*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Stria vascularis | Pre-synaptic | |

| Mitochondrial | m.03243 A > G | Pathogenic | Mitochondrial | Mitochondrial | [47, 48] | |||

| Mitochondrial | m.07472 insC | Pathogenic | Mitochondrial | Mitochondrial | ||||

| MYH9 | NM_002473.4 | c.2507 C > T | p.(Pro836Leu) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [49] |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.10082 + 1G > A | r.spl | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [50] |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.10216 + 1G > A | r.spl | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.10258_10260 del | p.(Phe3420 del) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.1137 del | p.(Tyr380fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.3742 C > T | p.(Arg1248 Trp) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.4519 C > T | p.(Arg1507*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.6787G > A | p.(Gly2263Ser) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.6892 C > T | p.(Arg2298*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.7893 + 1G > A | r.spl | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.806 dup | p.(Ala270fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.2471 del | p.(Pro824fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.625G > T | p.(Glu209*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO15 A | NM_016239.3 | c.8968 - 1G > T | r.spl | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO3 A | NM_017433.4 | c.2090 T > G | p.(Leu697 Trp) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [51] |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.1522 T > C | p.(Ser508Pro) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [52] |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.2078 del | p.(Lys693fs) | Truncating | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.3039 dup | p.(Thr1014fs) | Truncating | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.3109 - 2 A > G | r.spl | Splice | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.3508G > A | p.(Glu1170Lys) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.3719G > A | p.(Arg1240Gln) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.3764 del | p.(Lys1255fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.4117 C > T | p.(Arg1373*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.5648G > A | p.(Arg1883Gln) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.5944G > A | r.5857_5944 del p.(Val1953fs) | Splice | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.6028G > A | p.(Asp2010 Asn) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.1373 A > G | p.(Asn458Ser) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.1373 A > T | p.(Asn458Ile) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| MYO7 A | NM_000260.4 | c.5573 T > C | p.(Leu1858Pro) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| OPA1 | NM_130837.2 | c.1499G > A | p.(Arg500His) | Missense | Pathogenic | Auditory nerve | Post-synaptic | [53] |

| OTOF | NM_194248.2 | c.2122 C > T | p.(Arg708*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [54] |

| OTOF | NM_194248.2 | c.2649 C > A | p.(Cys883* | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| OTOF | NM_194248.2 | c.3264_3274 dup | p.(Phe1092fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| PAX3 | NM_181457.3 | c.1084_1087 dup | p.(Phe363fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Stria vascularis | Pre-synaptic | [55] |

| PAX3 | NM_181457.3 | c.242G > T | p.(Gly81 Val) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Stria vascularis | Pre-synaptic | |

| PAX3 | NM_181457.3 | c.246_247 del | p.(Val83fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Stria vascularis | Pre-synaptic | |

| PCDH15 | NM_001142769.2 | c.4542 dup | p.(Pro1515fs) | Truncating | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [56] |

| POU4 F3 | NM_002700.3 | c.668 T > C | p.(Leu223Pro) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [57] |

| PTPRQ | GW420685 | c.1491 T > A | p.(Tyr497*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [58] |

| PTPRQ | GW420685 | c.1548 del | p.(Tyr516*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.− 3- 25_164 + 160 del | p.? | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | [39, 59] |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1001 + 1G > A | r.spl | Splice | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1147 del | p.(Gln383fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1172G > A | p.(Ser391 Asn) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1174 A > T | p.(Asn392 Tyr) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1246 A > C | p.(Thr416Pro) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1489G > A | p.(Gly497Ser) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.2 T > C | p.(Met1?) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.412G > T | p.(Val138Phe) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.706 C > G | p.(Leu236 Val | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.707 C > T | p.(Leu236Pro) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.754 T > C | p.(Ser252Pro) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1342 - 2_1343 dup | p.(Leu450fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1694G > A | p.(Cys565 Tyr) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.1991 C > T | p.(Ala664 Val) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SLC26 A4 | NM_000441.1 | c.2048 T > C | p.(Phe683Ser) | Missense | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| SMPX | NM_014332.1 | c.45 + 1G > C | p.? | Splice | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [60] |

| SOX10 | NM_006941.3 | c.472G > T | p.(Glu158*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | [61] |

| SOX10 | NM_006941.3 | c.1229_1235 delinsTGGCC | p.(Pro410LeufsTer31) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Ion homeostasis | Pre-synaptic | |

| TMC1 | NM_138691.2 | c.229 del | p.(Arg77fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | [62] |

| TMC1 | NM_138691.2 | c.1763 + 3 A > G | p.(Met589fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| TMC1 | NM_138691.2 | c.65 - 1G > C | r.spl | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Pre-synaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.1276G > A | p.(Ala426 Thr) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | (63) |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.208 del | p.(His70fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.323 - 6G > A | p.(Val108Glyfs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.413 C > A | p.(Ala138Glu) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.595G > A | p.(Val199Met) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.916G > A | p.(Ala306 Thr) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.936 del | p.(Pro313fs) | Truncating | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TMPRSS3 | NM_024022.4 | c.325 C > T | p.(Arg109 Trp) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TPRN | NM_001128228.2 | c.1530 del | p.(Thr511fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | [64] |

| TPRN | NM_001128228.2 | c.225_235 del | p.(Gly76fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TPRN | NM_001128228.2 | c.744G > A | p.(Trp248*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| TUBB4B | NM_006088.6 | c.729_736 delinsCGGCCAGA | p.(Leu246Ile) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | [65] |

| USH1 C | NM_153676.4 | c.364 C > T | p.(Gln122*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | [66, 67] |

| USH1 C | NM_153676.3 | c.497 - 2 del | r.spl | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.11864G > A | p.(Trp3955*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | [67, 68] |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.1256G > T | p.(Cys419Phe) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.14289 del | p.(Ile4764fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.1606 T > C | p.(Cys536 Arg) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.2299 del | p.(Glu767fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.5018 T > C | p.(Leu1673Pro) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.7121 - 8313_11048 - 962 delins12 | p.(Val2374_Gly3683 del) | Deletion | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.8079G > A | p.(Trp2693*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.949 C > A | r.951_1143 del p.(Tyr318fs) | Missense | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.10525 A > T | p.(Lys3509*) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.6325 + 1G > C | r.spl | Splice | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| USH2 A | NM_206933.4 | c.8723_8724 del | p.(Val2908fs) | Truncating | Pathogenic | Hair cell | Presynaptic | |

| WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2051 C > T | p.(Ala684 Val) | Missense | Pathogenic | * | * | [69] |

| WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2115G > C | p.(Lys705 Asn) | Missense | Pathogenic | * | * | |

| WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2508G > C | p.(Lys836 Asn) | Missense | Likely pathogenic | * | * | |

| WFS1 | NM_006005.3 | c.2590G > A | p.(Glu864Lys) | Missense | Pathogenic | * | * |

*Cochlear site-of-lesion could not be determined

**References for the cochlear site-of-lesion

Audiological Performance

Audiometry data were retrieved from medical records. Standard pure tone and speech audiometry were conducted per local protocols. The pure tone average (PTA) was determined using thresholds at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz (PTA0.5-4kHz). Phoneme scores were assessed in quiet at 65 dB SPL. Both unaided and hearing-aid-assisted PTA and phoneme scores were measured pre-implantation. Post-implantation, unaided PTA scores, and CI-aided PTA and phoneme scores were measured. The post-implantation PTA0.5-4kHz and phoneme scores at 65 dB SPL were evaluated at one year, five years, and long-term (≥ 6 years post-implantation).

Not all subjects used hearing aids (HA) prior to implantation. We calculated the best-aided PTA and phoneme score to represent the pre-implantation auditory performance. The best-aided scores were derived from the scores obtained while using a HA in the implanted ear or from unaided scores in those subjects not using a HA preoperatively. These scores were used to compare pre-implantation hearing performance with post-implantation CI Performance.

In early-implanted subjects with prelingual SNHL, behavioral observation audiometry (BOA) or visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA), was used for pre-implantation and one-year follow-up pure tone thresholds. Due to their young age, speech audiometry could not be performed pre-implantation or at one-year follow-up for these children.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Science Statistics (SPSS) version 29, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were expressed as median with interquartile ranges (IQR) due to non-normal distribution as tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test compared mean PTA and phoneme scores at different follow-up moments.

Because of the broad variability in the age of implantation, CI outcomes were separately evaluated for early-implanted (first CI ≤ 6 years of age) and late-implanted subjects (first CI ≥ 7 years of age). This cut-off was based on research indicating that the effects of auditory deprivation on the nervous system can be (partially) restored up to age seven [70, 71].

To determine which factors contribute to the variability in CI outcomes, we first performed univariate regression analysis including the following variables: gender, age at implantation, self-reported duration of SNHL, duration of CI experience, use of HA in the ear to be implanted, degree of SNHL pre-implantation, residual hearing (unaided PTA0.5-4kHz measured two (IQR 1–7) months post-implantation), type of electrode array (perimodiolar (PME) versus lateral wall electrode (LWE)), implant brand (Cochlear LTD, Advanced Bionics, Oticon, MED-EL), year of implantation, type of insertion (cochleostomy, round window, extended round window), and cochlear site-of-lesion (HC, stria vascularis, ion homeostasis, cochlear nerve, mitochondria). Additionally, multiple regression analyses assessed the variance explained by each factor. A prediction model was constructed using backward selection, where factors within the model were deemed to significantly contribute with a p-value < 0.05. Sex- and gender-based analyses were conducted by incorporating gender as a contributing factor in these analyses.

The Mann–Whitney U test compared phoneme scores between two different subgroups. CI recipients with a measured phoneme score < 70% during the last follow-up visit were considered poorer performers and underwent more detailed evaluation, including a thorough review of their medical history, peri-implantation course, and rehabilitation period.

Results

Study Population

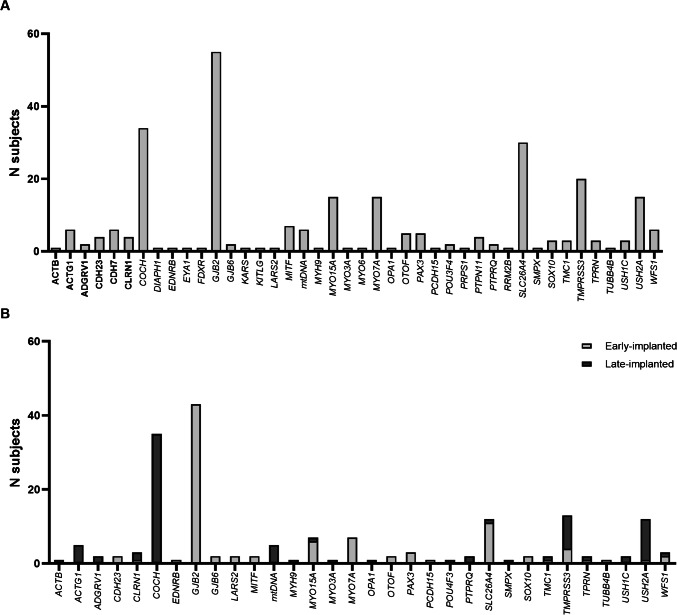

Between 2002 and 2021, 274 genotyped individuals underwent cochlear implantation. Causal variants were identified in 41 different nuclear and mitochondrial genes, with GJB2 (20.1%), COCH (12.5%), SLC26 A4 (10.9%), and TMPRSS3 (7.3%) being the most commonly affected genes (Fig. 1A). After evaluation of in- and exclusion criteria, 220 subjects were included in this study (Table 2). Nine subjects were excluded because of missing data, and 35 subjects because they, upon reclassification of identified variants, had no monoallelic or biallelic (likely) pathogenic variants in, respectively, dominantly or recessively inherited genes associated with SNHL. Additionally, ten subjects with syndromic SNHL linked to developmental delays that could potentially interfere with CI performance were excluded (CHARGE syndrome (N = 5); Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (N = 1); Noonan syndrome (N = 4)).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of affected genes. A Distribution of affected genes among the identified genotyped CI-recipients (N = 274 subjects). B Distribution of affected genes among the study population meeting the inclusion criteria (N = 220 subjects). Early-implanted denotes subjects who received their first CI at age ≤ 6 years, while late implanted indicates the first cochlear implantation performed at age > 6 years

Table 2.

Subject characteristics

| Subject characteristic | Total study cohort N = 220 subjects (100%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender, % female | 127 | (57.7) |

| Implantation | ||

| Unilateral | 141 | (64.1) |

| Bilateral simultaneously | 40 | (18.2) |

| Bilateral sequentially | 39 | (17.7) |

| Ear characteristics | N = 299 ears (100%) | |

| Age at implantation (median with IQR) | 6 y (1–43) | |

| Self-reported duration of hearing loss prior to implantation (median with IQR) | 5 y (1–20) | |

| Deviating anatomy at CT or MRI | ||

| Normal anatomy | 260 | (87.0) |

| Enlarged vestibular aqueduct | 34 | (11.4) |

| Cochlear incomplete partition | 4 | (1.3) |

| Hypoplasia of the cochlear nerve | 1 | (0.3) |

| Degree HL pre-implantation* | ||

| Moderate (41–60 dB HL) | 4 | (1.3) |

| Severe (61–80 dB HL) | 23 | (7.7) |

| Profound (> 80 dB HL) | 237 | (79.3) |

| Missing | 35 | (11.7) |

| Hearing aid in ear to be implanted | 264 | (88.3) |

| Surgical technique | ||

| Cochleostomy | 181 | (60.5) |

| Round window | 99 | (33.1) |

| Extended round window | 17 | (5.7) |

| Not reported | 2 | (0.7) |

| Type of electrode | ||

| PME | 200 | (66.9) |

| LWE | 99 | (33.1) |

IQR interquartile range, y years, CT computer tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, HL hearing loss, PME peri-modiolar electrode array, LWE lateral wall electrode array

*According to WHO’s grades of hearing impairment

Within the study population, (likely) pathogenic variants were identified in 31 different nuclear and mitochondrial genes (Fig. 1B). The most frequently affected genes were GJB2 (23.6%), COCH (15.9%), and SLC26 A4 (10.5%). Within the 220 subjects included, 124 unique variants were identified (Table 1), and 299 cochlear implantations were performed, with 141 subjects receiving unilateral implants and 79 receiving bilateral implants (40/79 simultaneous and 39/79 sequential).

Cochlear Implantation Outcomes

Pre- and post-implantation PTA0,5-4kHz and phoneme scores at 65 dB HL in quiet are shown in Table 3. The median last measured phoneme score was 90% (IQR 80–98). In late-implanted subjects (N = 143 ears), the last measured median phoneme score of 83% (IQR 74–90) was significantly lower than in early-implanted subjects (N = 156 ears) with a median score of 96% (IQR 90–100; p < 0.001). Early-implanted subjects also showed less variability in phoneme scores than the late-implanted subjects (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cochlear implantation outcomes

| Total study population N = 299 ears |

Early-implanted subjects N = 156 ears |

Late-implanted subjects N = 143 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at implantation | 6 y (1–43 y) | 15 m (10–37 m) | 44 y (17–60 y) | ||||

| PTA0,5-4kHz (dB HL) | |||||||

| Pre-implantation | Unaided PTA0,5-4kHz | 101 (90–111) | N = 264 | 106 (91–113) | N = 122 | 99 (86–110) | N = 142 |

| Best-aided PTA0,5-4kHz | 73 (51–90) | N = 294 | 80 (70–95) | N = 152 | 59 (48–81) | N = 142 | |

| Post-implantation | Aided PTA0,5-4kHz 1y FU | 29 (25–34)* | N = 287 | 31 (27–38)* | N = 151 | 26 (24–30)* | N = 136 |

| Aided PTA0,5-4kHz 5y FU | 24 (21–26)* | N = 195 | 24 (21–26)* | N = 143 | 26 (24–30) | N = 52 | |

| Aided PTA0,5-4kHz LT FU | 23 (21–25)+ | N = 137 | 23 (20–25)+ | N = 107 | 25 (23–32) | N = 30 | |

| Phoneme scores (%) | |||||||

| Pre-implantation | Unaided phoneme score | 0 (0–0) | N = 144 | 0 (0–10) | N = 11 | 0 (0–0) | N = 133 |

| Best-aided phoneme score | 32 (0–58) | N = 144 | 50 (0–55) | N = 11 | 30 (0–59) | N = 133 | |

| Post-implantation | Aided phoneme score 1y FU | 83 (72–90)* | N = 170 | 85 (72–95)+ | N = 33 | 83 (72–90)* | N = 137 |

| Aided phoneme score 5y FU | 93 (85–97)* | N = 217 | 95 (90–98)+ | N = 144 | 87 (74–94)+ | N = 73 | |

| Aided phoneme score LT FU | 95 (86–100)+ | N = 146 | 96 (95–100)* | N = 107 | 85 (77–92)+ | N = 39 | |

y years, m months, PTA pure tone average, FU follow-up, LT long term

Ages, PTA0,5-4kHz, and phoneme scores are presented as median with inter quartile ranges (IQR). Long-term follow-up was 10.1 (IQR 8.3–13.4) years

*Significant improvement compared to previous measurement (p < 0.001)

+Significant improvement compared to previous measurement (p < 0.010)

Cochlear Implantation Outcomes in Relation to the Cochlear Site-of-Lesion

Of the 31 affected nuclear genes, 28 were classified as either pre-synaptic or post-synaptic (Table 1). CLRN1 (N = 6 ears) and WFS1 (N = 7 ears) were excluded due to association with both pre- and post-synaptic pathology [72–74]. The phenotypes of these individuals have been described in detail in previous publications [33, 75]. Among them, only one individual with Usher syndrome type 3 exhibited bilateral hypoplasia of the cochlear nerve. The remaining subjects with CLRN1- or WFS1-associated SNHL showed no evidence of auditory neuropathy, as their CI outcomes remained stable over many years follow-up, as described in prior publications [33, 75].

Because of the widespread expression of COCH in the inner ear, its exact cochlear site-of-lesion could not be determined. Still, it was categorized as pre-synaptic due to its predominant expression in the spiral limbus and ligament [76]. Consequently, 27 nuclear genes were classified as pre-synaptic, one as post-synaptic (OPA1), and one as mitochondrial (LARS2) along with the mitochondrial genes (Table 1), totalling 286 ears (N = 211 subjects) included in the following analysis.

Figure 2A shows CI outcomes per affected gene, with most genes associated with good performance (median phoneme scores > 70%). Poorer outcomes (median phoneme score < 70%) were linked to MYO3 A (N = 1 ear), OTOF (N = 3 ears), OPaA1 (N = 1 ear), and USH1 C (N = 2 ears). OPA1 is classified as a post-synaptic gene, while MYO3 A, OTOF, and USH1 C are associated with HC pathologies and are thus classified as pre-synaptic genes.

Fig. 2.

CI outcomes per gene and cochlear site of lesion. A Cochlear implant outcomes per gene. Bars show median phoneme scores at 65 dB SPL in quiet, arranged from highest to lowest. Dots indicate individual data points, with the plot representing interquartile ranges. B Scatterplots of the last measured phoneme scores 65 dB SPL in quiet, broken down by subgroup. Each plot represents the median with interquartile ranges. Subjects with pathogenic variants in COCH (N = 37 ears) were excluded due to the gene’s broad expression in the pre-synaptic part of the cochlea. Similarly, subjects with variants in CLRN1 (N = 6 ears) and WFS1 (N = 7 ears) were excluded due to their association with both pre- and post-synaptic pathology

Figure 2B shows the CI outcomes per cochlear site-of-lesion, demonstrating high median phoneme scores in the HC, stria vascularis, and ion homeostasis groups and a lower median score in the mitochondrial group. The single subject with OPA1-associated SNHL (N = 1 ear), categorized in the post-synaptic group, had poor outcomes (phoneme score of 38% eight years post-implantation).

Within the pre-synaptic group, no significant difference was found between the stria vascularis and ion homeostasis group (p = 0.130). In contrast, the HC group had significantly lower phoneme scores (90% (IQR 80–98)) than the stria vascularis group (98% (IQR 89–100); p = 0.020) and the ion homeostasis group (95% (IQR 85–98); p = 0.043; Fig. 2B). These differences remained significant after excluding non-users (N = 8 ears and N = 7 ears for the stria vascularis and ion homeostasis groups, respectively) from the analysis (p = 0.041 and p = 0.042, respectively). Further analysis showed that the cochlear site-of-lesion did not correlate with CI outcomes within the pre-synaptic group (R2 = 0.005, p = 0.275), even after correcting for confounding factors as listed in Table 4. The lower phoneme scores observed in the HC group compared to the stria vascularis and ion homeostasis groups are primarily due to a higher number of subject-specific factors associated with poorer performance within the HC group (Table 5), combined with the observation that the majority of poorer performers (15 of the 29 individuals) fall within the HC group.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis with the phoneme score at 65 dB SPL in quiet as the dependent variable

| Dependant variable | Last measured phoneme score at 65 dB SPL in quiet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate regression analysis | ||||

| Variable | R2 | DF | F | p |

| Gender | 0.017 | 284 | 4.862 | 0.028+ |

| Age at implantation | 0.082 | 284 | 25.488 | < 0.001+ |

| Self-reported duration of SNHL | 0.017 | 284 | 4.783 | 0.030+ |

| Duration of CI experience | 0.097 | 284 | 30.437 | < 0.001+ |

| HA in ear to be implanted | 0.024 | 284 | 7.065 | 0.008+ |

| Degree of SNHL pre-implantation | 0.007 | 250 | 1.679 | 0.196 |

| Residual hearing | 0.001 | 100 | 0.150 | 0.699 |

| Implant type (PME vs LWE) | 0.002 | 284 | 0.496 | 0.482 |

| Implant Brand | 0.005 | 284 | 1.492 | 0.223 |

| Year of implantation | 0.000 | 284 | 0.002 | 0.965 |

| Type of insertion | 0.001 | 284 | 0.271 | 0.603 |

| Cochlear site-of-lesion* | 0.000 | 247 | 0.006 | 0.938 |

| Adjusted R2 | DF | F | p | |

| Model 1** | 0.441 | 54 | 5.345 | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 *** | 0.187 | 235 | 12.061 | < 0.001 |

| Model 3**** | 0.194 | 280 | 14.692 | < 0.001 |

DF degree of freedom, F F-test, p significancy, SNHL sensorineural hearing loss, HA hearing aids, PME peri-modiolar electrode, LWE lateral wall electrode

*Cochlear site-of-lesion includes hair cells, stria vascularis, ion homeostasis, auditory nerve, and mitochondria

**Model 1 includes all variables listed above in Table 3. The variables gender, HA in the ear to be implanted, residual hearing, type of electrode, brand, year of implantation, and cochlear site-of-lesion do not significantly contribute to this model

***Model 2 includes the cochlear site-of-lesion and all factors marked with a plus sign (+). In this model, the cochlear site-of-lesion did not significantly contribute

****Model 3 was conducted using backward selection and includes all factors marked with a plus sign (+). All factors are significantly attributed to this model

Table 5.

Poor cochlear implant performers

| Reason for poor performance | Number of ears | Involved genes (N ears) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prelingual SNHL and implanted during adulthood | 8 | (26.7%) |

GJB2 MYO7 A TMC1 USH1 C |

(4) (2) (1) (1) |

| Struggling to adjust to the sound of the second sequentially implanted CI | 6 | (20.0%) |

GJB2 MYO15 A OTOF SLC26 A4 USH1 C USH2 A |

(1) (1) (1) (1) (1) (1) |

| Post-lingual SNHL with an older age at implantation and a prolonged period without sufficient auditory stimulation prior to implantation | 6 | (20.0%) |

COCH mtDNA MYO3 A TMPRSS3 |

(2) (2) (1) (1) |

| Minimal encouragement from home or school for deaf to use the CI | 4 | (13.3%) |

GJB2 OTOF SLC26 A4 |

(1) (2) (1) |

| High-frequency SNHL with sufficient residual hearing in the lower frequencies post-implantation | 2 | (6.7%) | TMPRSS3 | (2) |

| Device failure | 2 | (6.7%) |

COCH SLC26 A4 |

(1) (1) |

| Auditory nerve hypoplasia or neuropathy | 2 | (6.7%) |

CLRN1 OPA1 |

(1) (1) |

SNHL sensorineural hearing loss, CI cochlear implant, mtDNA mitochondrial DNA

Comparison between pre-synaptic and post-synaptic groups was impossible due to the limited number of post-synaptic subjects (N = 1). The pre-synaptic group did not demonstrate significantly better outcomes than the mitochondrial group (p = 0.055).

Factors Contributing to the Variance in Cochlear Implantation Outcomes

We initially performed univariate regression analyses with the included 286 ears (N = 211 subjects) to identify factors significantly correlated with CI outcomes (Table 4). Five variables showed significant correlations, with duration of CI experience and age at implantation demonstrating the most substantial effects (R2 = 0.097, p < 0.001; and R2 = 0.082, p < 0.001, respectively). The cochlear site-of-lesion did not correlate with CI outcomes (R2 = 0.000, p = 0.938).

Additionally, multivariate regression analyses revealed that all factors listed in Table 4 (model 1) collectively accounted for 44.1% of the variance in phoneme scores (p < 0.001), although not all factors significantly contributed. A prediction model using backward selection was constructed in which all factors significantly contributed, including sex, age at implantation, self-reported duration of SNHL, CI experience, and HA in the ear to be implanted. This second model accounted for 19.0% of the variance in CI outcomes (p < 0.001).

Poorer Cochlear Implant Performers

Among the total study population, 29 individuals (13.4%; N = 30 ears (10.0%)) were poorer performers, defined as those with a last measured phoneme score < 70%. This resulted in non- or limited CI use in 14 individuals (6.5%; 15 ears (5.0%)). Among these individuals, 14 affected genes were identified across three groups (pre-/post-synaptic and mitochondrial). Multiple factors contributing to lower phoneme scores were identified, with poorer performance most frequently observed in individuals with prelingual SNHL and implantation in adulthood (26.7%) and those with sequential implanted CIs struggling to adapt to the sound of the second implant (20.0%). Furthermore, poorer performance was also common in individuals with post-lingual SNHL who underwent cochlear implantation at an older age after experiencing a prolonged period without adequate auditory stimulation (20.0%). Additional factors that contributed less are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

In this study of the largest cohort of genotyped CI recipients to date (N = 220), we aimed to evaluate CI outcomes and their correlation with affected genes and cochlear site-of-lesion. In line with previous studies involving collectively 334 genotyped CI recipients [11–17], our findings identified GJB2, COCH, SLC26 A4, TMPRSS3, and MYO7 A as the most frequently affected genes in genetic SNHL (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, in our Dutch cohort, a higher prevalence of causative variants in COCH was observed compared to the previous Asian, American, and German cohorts. This is attributable to demographic factors, as a specific variant in COCH is inherited from a common ancestor and is predominantly present in the southern parts of the Netherlands and in Belgium [77].

CI Outcomes in Genotyped CI Recipients

The first aim of our study was to evaluate CI outcomes in genotyped CI recipients. Our analysis of 220 recipients (N = 299 ears) demonstrated generally excellent short- and long-term outcomes, with a median phoneme score of 90% (IQR 80–98) at the last follow-up. Notably, subjects who received their first CI before the age of seven years had significantly higher phoneme scores (96% compared to 82%) and showed less variability than those who were implanted at a later age. These findings are consistent with previous studies [13, 16, 19–21], underscoring the importance of early implantation, which benefits from the greater plasticity of the central auditory system before the age of seven [70, 71]. Moreover, the present cohort also showed a higher median score than the cohort in the study by Tropitzsch et al., who reported a median word recognition score of 70% [15]. This is likely due to a longer self-reported duration of SNHL and an older age at implantation than in our cohort. Both factors have been associated with poorer outcomes [3].

CI Outcomes per Gene

Our second aim was to evaluate CI outcomes per gene. While most pathogenic variants in nuclear and mitochondrial genes led to beneficial outcomes, i.e., with phoneme scores in quiet of > 70%, four genes (MYO3 A, OTOF, OPA1, and USH1 C) were linked to poorer performance. However, each of these four groups included only a small number of subjects. MYO3 A, OTOF, and USH1 C are all associated with HC pathology [78–80], while OPA1 is associated with auditory neuropathy [81]. CI outcomes in MYO3 A-associated SNHL are not well-documented, with only one well-performing [16] and one poorly performing case reported [82]. CI outcomes for OTOF and OPA1-associated SNHL are generally beneficial [16, 19, 83–86]. While specific CI outcomes for Usher syndrome type 1 C are lacking, overall outcomes in Usher syndrome type 1 are positive when CIs are implanted early [33, 87–89].

The previously reported favorable CI outcomes for OTOF, OPA1, and USH1 C contradict the poorer outcomes observed in our study subjects. The identification of subject-specific factors in cases with causative pathogenic variants in MYO3 A, OTOF, and USH1 C (Table 5) suggests that these factors, rather than gene-specific ones, play a critical role in this discrepancy. These subject-specific factors include pre-lingual SNHL with cochlear implantation in adulthood, older age at implantation with a prolonged period of auditory deprivation, and minimal support system encouragement. This shows that the poorer performance observed among these subjects was independent of the causative genetic defects.

In contrast, we did not find subject-specific factors in the subject with OPA1-associated SNHL, who had stable phoneme scores of 70–80% for the initial five years post-implantation, which gradually declined to 38% by eight years post-implantation. This subject received a perimodiolar electrode array, and no implant failure was observed. Since cochlear nerve fibers in OPA1-associated SNHL likely degenerate over time [83], a decline in CI performance is anticipated. Moreover, OPA1 is associated not only with SNHL but also with optic atrophy and peripheral neuropathy, leading to progressive vision loss, sensory loss, and muscle weakness [90, 91]. This underscores the progressive peripheral nerve degeneration caused by OPA1 variants and highlights the need for future research to focus on long-term CI outcomes in OPA1-associated SNHL.

CI Outcomes per Cochlear Site-of-Lesion

The third aim of this study was to correlate CI outcomes with the cochlear site-of-lesion, for which we categorized affected genes into five groups: HC, stria vascularis, ion homeostasis, cochlear nerve, and mitochondria. The cochlear site-of-lesion did not account for CI outcome variability (R2 = 0.000, p = 0.938), and we found no significant differences in outcomes between the pre-synaptic and mitochondrial groups. Most affected genes were classified as pre-synaptic (N = 27 genes), while only one gene was classified as post-synaptic, making a reliable comparison of pre-and post-synaptic cases impossible. Note, however, that we excluded CLRN1 and WFS1 from our analysis as these are associated with both pre-and post-synaptic pathology [35, 70, 71].

In contrast, Tropitzsch et al. observed poorer CI performance in subjects with variants affecting the cochlea’s neural component [16]. However, when applying their classification system to our dataset, we found no significant difference in CI outcomes between the pre- and post-synaptic groups (Supplementary Fig. 1). This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that, among the eight genes they classified as post-synaptic (TMPRSS3, EDNRB, SOX10, WFS1, PAX3, EYA4, TFAP2 A, and DIAPH1), our dataset only included subjects with pathogenic variants in TMPRSS3, WFS1, and PAX3, all of whom generally had good CI outcomes (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, in previously published studies, we specifically evaluated CI outcomes in TMPRSS3- and WFS1-associated SNHL and concluded that, given their favorable short- and long-term CI outcomes, these genes are more likely associated with pre-synaptic rather than post-synaptic pathology [32, 75].

However, both our study and Troptizsch et al. faced challenges in determining the cochlear site-of-lesion. Tropitzsch et al. based the cochlear site-of-lesion on gene expression levels [16]. Instead, we first evaluated protein function and considered expression patterns if protein function was unknown. This resulted in differing classifications for certain genes. For example, Tropitzsch et al. categorized eight genes (TMPRSS, EDNR, SOX1, WFS1, PAX3, EYA4, TFAP2 A, and DIAPH1) in the neural group. In contrast, our method classified seven of these genes (all except TFAP2 A) as (also) linked to pre-synaptic pathology [74, 92–98]. Consequently, also in the study of Troptizsch et al., only one individual had pathogenic variants in a gene solely associated with post-synaptic pathology.

Both methods have limitations, as predominant expression in a certain cochlear structure does not necessarily mean it is most affected. Furthermore, protein function and expression levels are typically assessed in mouse models, which may not fully represent those in humans. Additionally, some genes have broad expression patterns or are associated with both pre- and post-synaptic pathology, complicating their classification. This highlights the need for caution in interpreting cochlear site-of-lesion classifications and emphasizes the necessity of further research. Future studies should focus on understanding protein function and (sensori)neural health integrity in genotyped individuals to better identify the cochlear site of lesion. Possible methods to consider are utilizing inner ear organoids to evaluate expression patterns [99, 100], or employing electrocochleography to assess (sensori)neural health [101, 102].

Although there is currently no strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that post-synaptic genetic etiologies are correlated with poorer CI outcomes, other studies suggest that individuals with SNHL due to post-synaptic pathology tend to have less favorable CI outcomes. For example, suboptimal outcomes have been observed in cases of lower SGN survival [103], cochlear nerve deficiency [84], cochlear nerve hypoplasia [104], and vestibular schwannoma [105, 106]. In contrast, generally positive CI outcomes are reported for etiologies associated with pre-synaptic pathologies. For instance, individuals with sudden deafness [107] or SNHL caused by ototoxic drugs [108], both linked to hair cell pathology [109, 110], show successful CI outcomes. This underlines the importance of further research into the correlation between CI outcomes and the cochlear site-of-lesion.

Factors of Influence on CI Outcomes in Genotyped CI Recipients

While the cochlear site-of-lesion did not significantly impact CI outcomes, other known factors did. Better outcomes were linked to younger age at implantation, longer duration of CI experience, use of an HA in the ear to be implanted, shorter self-reported duration of SNHL, and female sex. This is in line with previous research that has consistently linked these factors to better CI outcomes, except for sex [3, 4, 16]. Better outcomes in our cohort compared to other cohorts may be related to the inclusion of pediatric subjects in our study because in pediatric populations, younger age at implantation is particularly associated with better outcomes [87, 111, 112].

To further assess the impact of these factors, we constructed a linear model of CI outcome with the factors sex, CI experience, age at implantation, HA use, and duration of SNHL. This overall model explained 19% of the total variance, similar to the model by Lazard et al., that accounted for 22% of the variance in outcomes among adult CI recipients [4]. Poorer performance in our study was most frequently observed in subjects with pre-lingual SNHL who received a CI during adulthood (Table 5), a well-known factor associated with poor performance [113]. Post-lingual SNHL with older age at implantation and prolonged auditory deprivation before implantation were also frequently linked to poorer outcomes, consistent with previous studies [4, 114]. Additionally, poorer performance was noted in subjects who received a second CI sequentially but struggled to adapt to its sound, often leading to non-use.

Less frequently observed factors associated with poorer performance included device failure (N = 2), minimal encouragement from the supporting system to use the CI (N = 4), and ski-slope hearing loss with functional residual hearing in the lower frequencies post-implantation (N = 2). In the latter case, subjects had difficulty adapting to the CI sound or experienced limited benefits, resulting in restricted or non-use of the CI.

Finally, neural factors, such as cochlear nerve hypoplasia or auditory neuropathy, as was observed in the subjects with pathogenic variants in CLRN1 and OPA1, respectively, may result in poorer outcomes. In the case of cochlear nerve hypoplasia, the reduced number of nerve fibers could impair the transmission of electrically evoked signals from the implant to the brain. This aligns with previous studies showing poorer CI outcomes in recipients with cochlear nerve deficiencies than those with normal cochlear nerves [115–118].

Conclusion and Clinical Implications

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of the currently largest cohort of genotyped CI recipients, which shows that most individuals achieve excellent short- and long-term CI outcomes. The variability in speech perception was not correlated with the cochlear site-of-lesion but likely stemmed from subject-specific rather than underlying genetic defects. Our model, which includes sex, duration of CI experience, age at implantation, HA use, and duration of SNHL, explained 19.0% of this variance. The present findings suggest that most individuals with hereditary SNHL benefit from cochlear implantation, as most affected genes affect the pre-synaptic part of the cochlea. Poorer outcomes are anticipated in subjects who are older during implantation, have a longer duration of SNHL, and stopped using HA for a long time prior to implantation. Pre-implantation counselling should highlight the potentially poorer outcomes in individuals with SNHL linked to genes affecting the post-synaptic cochlea exclusively. However, further research is required to assess the correlation between cochlear site-of-lesion and CI outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

MF collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. LH re-classified all identified variants and contributed to writing the manuscript. HK classified the genes to a specific cochlear site-of-lesion. HG and MG collected data. EM and WH contributed to the study’s conception, design, and manuscript preparation. CL and RP were involved in the study’s conception and design, data interpretation, and made significant contributions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Cochlear Ltd. as an independent investigator-initiated research study.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

The codes used analyzing the date during the current study are available form the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

AI Use

ChatGPT ((https://chat.openai.com/) was used between September 2024 and January 2025 to refine the academic English in the introduction, methods, and discussion sections of this article. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the content. AI was not used to generate data or figures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mo B, Lindbaek M, Harris S (2005) Cochlear implants and quality of life: a prospective study. Ear Hear 26(2):186–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rask-Andersen H, Erixon E, Kinnefors A, Löwenheim H, Schrott-Fischer A, Liu W (2011) Anatomy of the human cochlea–implications for cochlear implantation. Cochlear Implants Int 12(Suppl 1):S8-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blamey P, Artieres F, Başkent D, Bergeron F, Beynon A, Burke E et al (2013) Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients. Audiol Neurootol 18(1):36–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazard DS, Vincent C, Venail F, Van de Heyning P, Truy E, Sterkers O et al (2012) Pre-, per- and postoperative factors affecting performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: a new conceptual model over time. PLoS ONE 7(11):e48739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knopke S, Bauknecht HC, Gräbel S, Häußler SM, Szczepek AJ, Olze H (2021) White matter lesions as possible predictors of audiological performance in adults after cochlear implantation. Brain Sci 11(5):600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morton CC, Nance WE (2006) Newborn hearing screening–a silent revolution. N Engl J Med 354(20):2151–2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Schaefer AM, Smith RJH (1993) Genetic hearing loss overview. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH et al (eds) GeneReviews(®). University of Washington, Seattle [PubMed]

- 8.Allen SB, Goldman J (2025) Syndromic sensorineural hearing loss. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526088/ [PubMed]

- 9.Smith R, Shearer AE, Camp G. Hereditary hearing loss homepage 2021. Available from: https://hereditaryhearingloss.org/.

- 10.Zazo Seco C, Wesdorp M, Feenstra I, Pfundt R, Hehir-Kwa JY, Lelieveld SH et al (2017) The diagnostic yield of whole-exome sequencing targeting a gene panel for hearing impairment in The Netherlands. Eur J Hum Genet 25(3):308–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu CC, Liu TC, Wang SH, Hsu CJ, Wu CM (2011) Genetic characteristics in children with cochlear implants and the corresponding auditory performance. Laryngoscope 121(6):1287–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SY, Shim YJ, Han JH, Song JJ, Koo JW, Oh SH et al (2020) The molecular etiology of deafness and auditory performance in the postlingually deafened cochlear implantees. Sci Rep 10(1):5768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Usami S (2016) A comprehensive study on the etiology of patients receiving cochlear implantation with special emphasis on genetic epidemiology. Otol Neurotol 37(2):e126–e134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JH, Kim NK, Kim AR, Rhee J, Oh SH, Koo JW et al (2014) Exploration of molecular genetic etiology for Korean cochlear implantees with severe to profound hearing loss and its implication. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9:167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshimura H, Moteki H, Nishio SY, Miyajima H, Miyagawa M, Usami SI (2020) Genetic testing has the potential to impact hearing preservation following cochlear implantation. Acta Otolaryngol 140(6):438–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tropitzsch A, Schade-Mann T, Gamerdinger P, Dofek S, Schulte B, Schulze M et al (2023) Variability in cochlear implantation outcomes in a large german cohort with a genetic etiology of hearing loss. Ear Hear 44(6):1464–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seligman KL, Shearer AE, Frees K, Nishimura C, Kolbe D, Dunn C et al (2022) Genetic causes of hearing loss in a large cohort of cochlear implant recipients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 166(4):734–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott HS, Kudoh J, Wattenhofer M, Shibuya K, Berry A, Chrast R et al (2001) Insertion of beta-satellite repeats identifies a transmembrane protease causing both congenital and childhood onset autosomal recessive deafness. Nat Genet 27(1):59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishio SY, Usami SI (2017) Outcomes of cochlear implantation for the patients with specific genetic etiologies: a systematic literature review. Acta Otolaryngol 137(7):730–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usami S-I, Nishio S-Y, Moteki H, Miyagawa M, Yoshimura H (2020) Cochlear implantation from the perspective of genetic background. Anat Rec 303(3):563–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson RJ, Walsh T, Mandell JB, Aburayyan A, Lee MK, Gulsuner S et al (2023) Association of genetic diagnoses for childhood-onset hearing loss with cochlear implant outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 149(3):212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eppsteiner RW, Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Deluca AP, Ji H, Dunn CC et al (2012) Prediction of cochlear implant performance by genetic mutation: the spiral ganglion hypothesis. Hear Res 292(1–2):51–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schvartz-Leyzac KC, Colesa DJ, Swiderski DL, Raphael Y, Pfingst BE (2023) Cochlear health and cochlear-implant function. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 24(1):5–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carricondo F, Romero-Gómez B (2019) The cochlear spiral ganglion neurons: the auditory portion of the VIII nerve. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 302(3):463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berglund AM, Ryugo DK (1986) A monoclonal antibody labels type II neurons of the spiral ganglion. Brain Res 383(1–2):327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webster DB, Popper AN, Fay RR (eds) (2013) The mammalian auditory pathway: neuroanatomy. Springer Science & Business Media

- 27.Gil-Loyzaga P, Bartolomé V, Vicente-Torres A, Carricondo F (2000) Serotonergic innervation of the organ of Corti. Acta Otolaryngol 120(2):128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pennings RJ, Damen GW, Snik AF, Hoefsloot L, Cremers CW, Mylanus EA (2006) Audiologic performance and benefit of cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome type I. Laryngoscope 116(5):717–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartel BP, van Nierop JWI, Huinck WJ, Rotteveel LJC, Mylanus EAM, Snik AF et al (2017) Cochlear implantation in patients with usher syndrome type IIa increases performance and quality of life. Otol Neurotol 38(6):e120–e127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plantinga RF, Kleemola L, Huygen PL, Joensuu T, Sankila EM, Pennings RJ et al (2005) Serial audiometry and speech recognition findings in Finnish Usher syndrome type III patients. Audiol Neurootol 10(2):79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damen GW, Pennings RJ, Snik AF, Mylanus EA (2006) Quality of life and cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome type I. Laryngoscope 116(5):723–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fehrmann MLA, Huinck WJ, Thijssen MEG, Haer-Wigman L, Yntema HG, Rotteveel LJC et al (2023) Stable long-term outcomes after cochlear implantation in subjects with TMPRSS3 associated hearing loss: a retrospective multicentre study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 52(1):82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fehrmann MLA, Lanting CP, Haer-Wigman L, Yntema HG, Mylanus EAM, Huinck WJ, Pennings RJE (2024) Long-term outcomes of cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome. Ear Hear 45(6):1542–1553. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Fehrmann MLA, Meijer FJA, Mylanus EAM, Pennings RJE, Lanting CP, Huinck WJ (2025) Evaluating cochlear implant outcomes in DFNA9 subjects: a comprehensive study on cerebral white matter lesions and vestibular abnormalities. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 282(1):183–191. 10.1007/s00405-024-08933-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J et al (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17(5):405–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furness DN, Katori Y, Mahendrasingam S, Hackney CM (2005) Differential distribution of beta- and gamma-actin in guinea-pig cochlear sensory and supporting cells. Hear Res 207(1–2):22–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrin BJ, Sonnemann KJ, Ervasti JM (2010) β-actin and γ-actin are each dispensable for auditory hair cell development but required for Stereocilia maintenance. PLoS Genet 6(10):e1001158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belyantseva IA, Perrin BJ, Sonnemann KJ, Zhu M, Stepanyan R, McGee J et al (2009) Gamma-actin is required for cytoskeletal maintenance but not development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(24):9703–9708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merchant SN, Nakajima HH, Halpin C, Nadol JB Jr, Lee DJ, Innis WP et al (2007) Clinical investigation and mechanism of air-bone gaps in large vestibular aqueduct syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116(7):532–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Libé-Philippot B, Michel V, Boutet de Monvel J, Le Gal S, Dupont T, Avan P et al (2017) Auditory cortex interneuron development requires cadherins operating hair-cell mechanoelectrical transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(30):7765–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siemens J, Lillo C, Dumont RA, Reynolds A, Williams DS, Gillespie PG, Müller U (2004) Cadherin 23 is a component of the tip link in hair-cell stereocilia. Nature 428(6986):950–955. 10.1038/nature02483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson NG, Resendes BL, Lin JS, Lee C, Aster JC, Adams JC, Morton CC (2001) Inner ear localization of mRNA and protein products of COCH, mutated in the sensorineural deafness and vestibular disorder, DFNA9. Hum Mol Genet 10(22):2493–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ida-Eto M, Ohgami N, Iida M, Yajima I, Kumasaka MY, Takaiwa K et al (2011) Partial requirement of endothelin receptor B in spiral ganglion neurons for postnatal development of hearing. J Biol Chem 286(34):29621–29626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wingard JC, Zhao H-B (2015) Cellular and deafness mechanisms underlying connexin mutation-induced hearing loss – a common hereditary deafness. Front Cell Neurosci 9:202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishio SY, Takumi Y, Usami SI (2017) Laser-capture micro dissection combined with next-generation sequencing analysis of cell type-specific deafness gene expression in the mouse cochlea. Hear Res 348:87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tachibana M (2001) Cochlear melanocytes and MITF signaling. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 6(1):95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKenzie M, Liolitsa D, Hanna MG (2004) Mitochondrial disease: mutations and mechanisms. Neurochem Res 29(3):589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Kempen CMA, Beynon AJ, Smits JJ, Janssen MCH (2022) A retrospective cohort study exploring the association between different mitochondrial diseases and hearing loss. Mol Genet Metab 135(4):333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diaz-Horta O, Abad C, Cengiz FB, Bademci G, Blackwelder P, Walz K, Tekin M (2018) Ripor2 is involved in auditory hair cell stereociliary bundle structure and orientation. J Mol Med (Berl) 96(11):1227–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belyantseva IA, Boger ET, Friedman TB (2003) Myosin XVa localizes to the tips of inner ear sensory cell stereocilia and is essential for staircase formation of the hair bundle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100(24):13958–13963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh T, Walsh V, Vreugde S, Hertzano R, Shahin H, Haika S et al (2002) From flies’ eyes to our ears: mutations in a human class III myosin cause progressive nonsyndromic hearing loss DFNB30. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(11):7518–7523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S, Mecca A, Kim J, Caprara GA, Wagner EL, Du T-T et al (2020) Myosin-VIIa is expressed in multiple isoforms and essential for tensioning the hair cell mechanotransduction complex. Nat Commun 11(1):2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang T, Santarelli R, Starr A (2009) Mutation of OPA1 gene causes deafness by affecting function of auditory nerve terminals. Brain Res 1300:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roux I, Safieddine S, Nouvian R, Grati M, Simmler MC, Bahloul A et al (2006) Otoferlin, defective in a human deafness form, is essential for exocytosis at the auditory ribbon synapse. Cell 127(2):277–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim H, Ankamreddy H, Lee DJ, Kong KA, Ko HW, Kim MH, Bok J (2014) Pax3 function is required specifically for inner ear structures with melanogenic fates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 445(3):608–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Senften M, Schwander M, Kazmierczak P, Lillo C, Shin JB, Hasson T et al (2006) Physical and functional interaction between protocadherin 15 and myosin VIIa in mechanosensory hair cells. J Neurosci 26(7):2060–2071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, Gu Y, Li Y, Li GL, Chai R, Li W, Li H (2021) Generation of mature and functional hair cells by co-expression of Gfi1, Pou4f3, and Atoh1 in the postnatal mouse cochlea. Cell Rep 35(3):109016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodyear RJ, Legan PK, Wright MB, Marcotti W, Oganesian A, Coats SA et al (2003) A receptor-like inositol lipid phosphatase is required for the maturation of developing cochlear hair bundles. J Neurosci 23(27):9208–9219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wangemann P, Itza EM, Albrecht B, Wu T, Jabba SV, Maganti RJ et al (2004) Loss of KCNJ10 protein expression abolishes endocochlear potential and causes deafness in Pendred syndrome mouse model. BMC Med 2:30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tu H, Zhang A, Fu X, Xu S, Bai X, Wang H, Gao J (2021) SMPX deficiency causes Stereocilia degeneration and progressive hearing loss in CBA/CaJ mice. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:750023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szeto IYY, Chu DKH, Chen P, Chu KC, Au TYK, Leung KKH et al (2022) SOX9 and SOX10 control fluid homeostasis in the inner ear for hearing through independent and cooperative mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119(46):e2122121119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu S, Wang S, Zou L, Li J, Song C, Chen J et al (2019) TMC1 is an essential component of a leak channel that modulates tonotopy and excitability of auditory hair cells in mice. Elife 8:e47441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen YS, Cabrera E, Tucker BJ, Shin TJ, Moawad JV, Totten DJ et al (2022) TMPRSS3 expression is limited in spiral ganglion neurons: implication for successful cochlear implantation. J Med Genet 59(12):1219–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Men Y, Li X, Tu H, Zhang A, Fu X, Wang Z et al (2019) Tprn is essential for the integrity of stereociliary rootlet in cochlear hair cells in mice. Front Med 13(6):690–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu H, Chen L, Giffen KP, Stringham ST, Li Y, Judge PD, Beisel KW, He DZZ (2018) Cell-specific transcriptome analysis shows that adult pillar and Deiters’ cells express genes encoding machinery for specializations of cochlear hair cells. Front Mol Neurosci 11:356. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lefèvre G, Michel V, Weil D, Lepelletier L, Bizard E, Wolfrum U et al (2008) A core cochlear phenotype in USH1 mouse mutants implicates fibrous links of the hair bundle in its cohesion, orientation and differential growth. Development 135(8):1427–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reiners J, van Wijk E, Märker T, Zimmermann U, Jürgens K, te Brinke H et al (2005) Scaffold protein harmonin (USH1C) provides molecular links between Usher syndrome type 1 and type 2. Hum Mol Genet 14(24):3933–3943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu X, Bulgakov OV, Darrow KN, Pawlyk B, Adamian M, Liberman MC, Li T (2007) Usherin is required for maintenance of retinal photoreceptors and normal development of cochlear hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(11):4413–4418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cryns K, Thys S, Van Laer L, Oka Y, Pfister M, Van Nassauw L et al (2003) The WFS1 gene, responsible for low frequency sensorineural hearing loss and Wolfram syndrome, is expressed in a variety of inner ear cells. Histochem Cell Biol 119(3):247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharma A, Dorman MF, Spahr AJ (2002) A sensitive period for the development of the central auditory system in children with cochlear implants: implications for age of implantation. Ear Hear 23(6):532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kral A, Sharma A (2012) Developmental neuroplasticity after cochlear implantation. Trends Neurosci 35(2):111–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dulon D, Papal S, Patni P, Cortese M, Vincent PF, Tertrais M et al (2018) Clarin-1 gene transfer rescues auditory synaptopathy in model of Usher syndrome. J Clin Invest 128(8):3382–3401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zallocchi M, Meehan DT, Delimont D, Askew C, Garige S, Gratton MA et al (2009) Localization and expression of clarin-1, the Clrn1 gene product, in auditory hair cells and photoreceptors. Hear Res 255(1–2):109–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cryns K, Thys S, Van Laer L, Oka Y, Pfister M, Van Nassauw L et al (2003) The WFS1 gene, responsible for low frequency sensorineural hearing loss and Wolfram syndrome, is expressed in a variety of inner ear cells. Histochem Cell Biol 119(3):247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fehrmann MLA, Lanting CP, Haer-Wigman L, Mylanus EAM, Huinck WJ, Pennings RJE. Good cochlear implantation outcomes in subjects with mono-allelic WFS1-associated sensorineural hearing loss - a case series. Int J Audiol. 2024:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Robertson NG, Resendes BL, Lin JS, Lee C, Aster JC, Adams JC et al (2001) Inner ear localization of mRNA and protein products of COCH, mutated in the sensorineural deafness and vestibular disorder, DFNA9. Hum Mol Genet 10(22):2493–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fransen E, Verstreken M, Bom SJ, Lemaire F, Kemperman MH, De Kok YJ et al (2001) A common ancestor for COCH related cochleovestibular (DFNA9) patients in Belgium and The Netherlands bearing the P51S mutation. J Med Genet 38(1):61–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walsh T, Walsh V, Vreugde S, Hertzano R, Shahin H, Haika S, Lee MK, Kanaan M, King MC, Avraham KB (2002) From flies’ eyes to our ears: mutations in a human class III myosin cause progressive nonsyndromic hearing loss DFNB30. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(11):7518–7523. 10.1073/pnas.102091699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roux I, Safieddine S, Nouvian R, Grati M, Simmler MC, Bahloul A et al (2006) Otoferlin, defective in a human deafness form, is essential for exocytosis at the auditory ribbon synapse. Cell 127(2):277–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reiners J, van Wijk E, Märker T, Zimmermann U, Jürgens K, te Brinke H et al (2005) Scaffold protein harmonin (USH1C) provides molecular links between Usher syndrome type 1 and type 2. Hum Mol Genet 14(24):3933–3943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang T, Santarelli R, Starr A (2009) Mutation of OPA1 gene causes deafness by affecting function of auditory nerve terminals. Brain Res 1300:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu CC, Lin YH, Liu TC, Lin KN, Yang WS, Hsu CJ et al (2015) Identifying children with poor cochlear implantation outcomes using massively parallel sequencing. Medicine (Baltimore) 94(27):e1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Santarelli R, Rossi R, Scimemi P, Cama E, Valentino ML, La Morgia C et al (2015) OPA1-related auditory neuropathy: site of lesion and outcome of cochlear implantation. Brain 138(Pt 3):563–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin PH, Wu HP, Wu CM, Chiang YT, Hsu JS, Tsai CY et al (2022) Cochlear implantation outcomes in patients with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder of genetic and non-genetic etiologies: a multicenter study. Biomedicines 10(7):1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maeda-Katahira A, Nakamura N, Hayashi T, Katagiri S, Shimizu S, Ohde H et al (2019) Autosomal dominant optic atrophy with OPA1 gene mutations accompanied by auditory neuropathy and other systemic complications in a Japanese cohort. Mol Vis 25:559–573 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tekin AM, Baelen H, Heuninck E, Bayazıt YA, Mertens G, Rompaey VV et al (2023) Evaluation of a less invasive cochlear implant surgery in OPA1 mutations provoking deafblindness. Genes (Basel) 14(3):627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davies C, Bergman J, Misztal C, Ramchandran R, Mittal J, Bulut E et al (2021) The outcomes of cochlear implantation in Usher syndrome: a systematic review. J Clin Med 10(13):2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loundon N, Marlin S, Busquet D, Denoyelle F, Roger G, Renaud F et al (2003) Usher syndrome and cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol 24(2):216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Remjasz-Jurek A, Clarós P, Clarós-Pujol A, Pujol C, Clarós A (2023) Outcomes of cochlear implantation in children with Usher syndrome: a long-term observation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 280(5):2119–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]