Abstract

Background

Partial nephrectomy is the gold standard for small renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN), introduced in 2004, has gained acceptance as a minimally invasive approach. Determining resection margins in complex cases remains a challenge. 5-ALA, a photosensitizer metabolized to protoporphyrin IX (PPIX), induces red fluorescence under blue light, aiding tumor detection. Although effective in other malignancies, its utility in renal tumors is not well established.

Methods

Between May 2016 and August 2017, 19 patients underwent RAPN using photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) at our institution with the da Vinci Surgical System Si®. Patients received 20 mg/kg 5-ALA in 50 mL water orally, 0–12 h before skin incision. Tumor fluorescence was observed with Olympus or Storz camera systems under excitation wavelengths for characteristic red fluorescence during surgery. We evaluated 5-ALA and protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) levels in tumor and normal tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Statistical analyses were performed using Mann‒Whitney U tests with GraphPad Prism 5. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Tumor pathology revealed clear cell RCC in 17 and chromophobe RCC in two cases. Only one clear cell RCC tumor showed fluorescence under excitation wavelengths before renal artery clamping; however, normal peri-tumoral tissues also demonstrated fluorescence. In three cases, including this one, fluorescence was observed in both tumor and normal tissues ex vivo within a dark box. In the ex vivo analysis, two cases exhibited fluorescence in the tumor tissue without fluorescence in the normal tissue, while one exhibited the reverse. Accumulation of 5-ALA and PPIX in resected tissue specimens was measured in six cases. Although statistical significance was not reached due to the small sample size (p = 0.057, Mann-Whitney U test), PPIX concentrations tended to be higher in fluorescence-positive tumors than in fluorescence-negative ones.

Conclusions

Both tumors and normal tissues exhibited heterogeneous PPIX levels, limiting margin visualization. While current 5-ALA-PDD was insufficient for guiding resection in RAPN, further optimization may enhance its clinical utility.

Keywords: 5-aminolevulinic acid, Photodynamic detection, Protoporphyrin IX, Renal cell carcinoma, Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy, Fluorescence imaging

Introduction

Partial nephrectomy is currently considered the gold standard for small renal tumors. Using the Da Vinci Surgical System, robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) was introduced in 2004 by Gettman et al. [1]. The use of this system has steadily gained acceptance as a viable alternative to both open and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for small renal tumors. It is essential to secure a negative margin in RAPN; however, determining the resection margin by ultrasound can often be challenging in patients with complex tumors.

As 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) is a natural amino acid in both animals and plants, it is safe for clinical use. 5-ALA, metabolized to protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) in the heme biosynthesis pathway, accumulates variably across tissue types. Photodynamically active PPIX tends to accumulate more in epithelial tissues and tumors than in mesenchymal tissues. This can be partly explained by reduced ferrochelatase (FECH) activity in tumors, which impairs the conversion of PPIX to heme and leads to its accumulation and fluorescence under excitation light [2–7]. 5-ALA was first reported as a photosensitive substance in the PDD of malignant tumors [3]. Exogenously administered 5-ALA increases the intracellular levels of photosensitizing PPIX and results in stronger emission of red fluorescence (around 635 nm) in cancer lesions than in normal tissues under blue light excitation (around 400–410 nm). Because of the unique properties of 5-ALA, 5-ALA-induced fluorescence-guided resection has been widely utilized in surgery for many types of malignant tumors, such as bladder cancer [8, 9], upper tract urothelial cancer [10], malignant glioma [6, 11], esophageal cancer, and prostate cancer [12, 13]. However, the kidney exhibits unique metabolic properties that may affect PPIX accumulation and fluorescence differentiation. Van den Boogert et al. demonstrated that renal tissues inherently accumulate higher basal levels of porphyrins [14], which may contribute to background fluorescence in normal renal tissues and reduce the specificity of 5-ALA-PDD in distinguishing tumors from adjacent parenchyma. This limitation presents a significant challenge for effectively applying 5-ALA fluorescence imaging in renal tumor resection.

In 2009, Hoda and Popken reported that photodynamic diagnosis after systemic administration of 5-ALA was a reliable tool for assessing suspected renal tumors’ type and resection status during laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) [15]. However, this study has not been replicated, and the feasibility of 5-ALA-PDD for delineating resection margins in RAPN remains unclear. This is the first study to quantitatively measure and compare intrarenal concentrations of 5-ALA and its metabolite PPIX in paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues during RAPN. Therefore, we investigated whether 5-ALA-mediated PDD could aid in identifying the resection line in RAPN.

Materials and methods

Patient population and selection

The subjects were patients who underwent 5-ALA-mediated photodynamic diagnosis and RAPN for renal cell carcinoma at Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital from May 2016 to August 2017. This study was approved by the Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval no.15037), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure. This study was conducted as an exploratory analysis to assess the feasibility of 5-ALA-mediated fluorescence detection in RAPN. Given the limited availability of eligible patients, a formal power calculation was not performed. While the small sample size (n = 19) limits statistical power, the findings provide preliminary insights for future studies.

Photodynamic detection

Based on Hoda and Popken’s study [15], 20 mg/kg 5-ALA (kindly provided by SBI Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan), dissolved in 50 mL water, was administered orally six hours prior to skin incision. The optimal timing of 5-ALA administration for renal tumor fluorescence remains uncertain. In our initial attempts, 5-ALA was administered 6 h prior to skin incision to ensure safe anesthesia; however, no fluorescence response was observed in the first three cases. Since fluorescence was not detected, the timing was adjusted based on prior studies reporting PPIX fluorescence peaks at 2–3 h post-administration [14]. Given the delay in tumor exposure during RAPN, 5-ALA was administered before skin incision in Cases #4 to #6, but fluorescence remained undetectable. To assess its impact, administration timing varied across cases: oral administration was performed 6 to 20 h before surgery, while in four cases, 5-ALA was administered via a gastric tube immediately before surgery.

We used a light assistance system that facilitated blue light excitation of the photosensitizing protoporphyrin IX, resulting in the emission of red fluorescence. Initially, we used the Olympus camera system (S7Pro®, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and an Aladuck Ls-DLED® light assistance system (SBI Pharmaceuticals) for the first seven cases. The Olympus camera system requires a filter in front of the camera head. Because we could not confirm the fluorescence of the tumors, we switched to a Karl Storz camera and light assistance system (IMAGE1S full HD camera system®, Karl Storz SE & Co., Tuttlingen, Germany). Since two different camera systems (Olympus and Karl Storz) were used in this study, differences in sensitivity could have affected fluorescence detection. Although direct cross-validation between the systems was not performed, efforts were made to minimize bias by using standardized observation protocols and ensuring comparable imaging conditions. Fluorescence assessments were conducted with the da Vinci surgical light turned off and under each system’s excitation and exposure settings. Additionally, fluorescence evaluation was performed in a dark box ex vivo to reduce ambient light interference.

Surgical technique

All procedures were performed with the patient in the flank position under general anesthesia, and the Da Vinci Surgical System Si® was docked. Intraoperative pneumoperitoneum pressure was set at 10 mm Hg. Nine patients underwent transperitoneal approaches, and ten underwent retroperitoneal approaches. Externally protruding superficial tumors were resected without ischemia, while in other cases, tumor resection was performed by clamping the renal artery. When observing the tumor, the da Vinci Surgical System Si® light source was turned off, and the camera for PDD was inserted through the assistant port for fluorescence observation.

Histopathological evaluation

The excised specimen underwent pathological examination to confirm the tumor’s histological type. Additionally, we confirmed the content of 5-ALA and PPIX in seven tumor tissues and nine normal peri-tumoral tissue specimens from six patients.

Analysis of 5-ALA and PPIX

Excised tissues were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (four times the weight of the tissue) using an electric homogenizer.

5-ALA levels were measured based on the method of Miyajima et al. [7]. Initially, 0.04 mL of a 25% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid solution was added to 0.1 mL of the tissue homogenate solution, followed by stirring and centrifugation to obtain the supernatant. Subsequently, 0.01 mL of this supernatant was transferred to a glass tube, and 0.24 mL of Milli-Q water, 0.25 mL of 200 mM acetic acid‒sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.8), reaction solution A (15% v/v acetylacetone and 10% v/v ethanol), and 0.25 mL of reaction solution B (3.3% w/v formaldehyde) were added and stirred. The samples were then placed in a boiling water bath. After 15 min, this mixture was cooled rapidly in ice and analyzed using HPLC on an Agilent 1100 series (Agilent®, Santa Clara, CA, USA), using a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 Rapid Resolution HT (φ 4.6 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm, Agilent®) at 40 °C. The eluent was 2.5% acetic acid‒methanol (6/4, v/v). Fluorescence was excited at a wavelength of 363 nm, and emission was detected at 473 nm, using a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min in the column.

Measurement of PPIX followed the protocol outlined by Kondo et al. [16] and was performed using HPLC analysis. Briefly, 0.01 mL of 50% (v/v) acetic acid and 0.30 mL of N, N-dimethylformamide-2-propanol (DMF-IPA) solution (100/1, v/v) were added to 0.1 mL of homogenate solution. The mixture was stirred well and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. Subsequently, 0.15 mL of DMF-IPA solution was added to the precipitate, the above steps were repeated, and the resultant supernatants were mixed. The mixed supernatants were analyzed by HPLC, using an Alliance HPLC device (Waters®, Milford, MA, USA) with a CAPCELL PAK C18 UG120 column (φ 4.6 × 150 mm, five µm, SHISEIDO®, Tokyo, Japan) at 40 °C. The eluent was acetonitrile‒10 mM tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (pH 7.5) solution (7:3, v/v). Fluorescence was excited at 400 nm, and emission was detected at 630 nm, with a 1.0 mL/min flow rate in the column.

The assay was validated by assessing recovery rates, intra-/inter-assay variability, and detection limits to confirm its accuracy and reproducibility. PPIX and 5-ALA concentrations were measured using HPLC with fluorescence detection after derivatization with acetylacetone at pH 4.6. PPIX concentrations were further normalized to protein content, which was calculated using the Lowry assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Mann‒Whitney U tests in GraphPad Prism 5. Results with p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and surgical outcomes

A total of 19 patients were enrolled in this study. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics and surgical outcomes. Median blood loss was 125 mL, and no major complications were observed. The pathology of the tumors revealed clear cell RCC in 17 cases and chromophobe RCC in two cases.

Table 1.

Patient’s characteristics and surgical outcomes

| Number of patients | 19 |

|---|---|

| Median age (year, range) | 61 (40-82) |

| Sex | |

| male | 14 |

| female | 5 |

| Median tumor size (mm, range) | 33 (13-50) |

| Median operation time (min, range) | 166 (138-224) |

| Median console time (min, range) | 101 (68-147) |

| Median warm ischemic time (min, range) | 16.5 (7-34) |

| Median Blood loss (ml, range) | 125 (0-400) |

| Median postoperative hospital stay (day) | 7 (4-8) |

| Histopathology | |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 17 |

| Chromophobe carcinoma | 2 |

| Complications | |

| Liver dysfunction (Clavien 1) | 4 |

| Surgical site infection (Clavien 2) | 1 |

Intraoperative and ex vivo fluorescence observations

The timing of 5-ALA administration and fluorescence responses are shown in Table 2. In Cases #1 to #3, 5-ALA was administered orally 6 h before surgery, but no fluorescence response was observed. Therefore, in Cases #4 to #6, 5-ALA was administered via a gastric tube immediately before surgery; however, fluorescence was still undetected. In Case #7, oral administration was performed 12 h before surgery, yet no fluorescence response was observed. As a result, from Case #8 to #19, the camera system was switched from the Olympus camera system (S7Pro®, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and an Aladuck Ls-DLED® light assistance system (SBI Pharmaceuticals) to the Karl Storz camera and light assistance system (IMAGE1S full HD camera system®, Karl Storz SE & Co., Tuttlingen, Germany).

Table 2.

Fluorescence in the tumor and the normal tissues in 19 cases

| Case no. | Age | Sex | Tumor size (mm) | Pathology | Administration time of 5-ALA prior to skin incision (hour) |

Camera system | Fluorescence of tumor during resection | Fluorescence of tumor in ex vivo (dark box) | Fluorescence of the normal tissue around the tumor in dark box |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | M | 35 | Clear cell carcinoma | 6 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 2 | 76 | F | 29 | Clear cell carcinoma | 6 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 3 | 59 | M | 33 | Clear cell carcinoma | 6 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 4 | 63 | M | 20 | Clear cell carcinoma | 0 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 5 | 71 | M | 16 | Clear cell carcinoma | 0 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 6 | 78 | F | 36 | Clear cell carcinoma | 0 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 7 | 82 | M | 38 | Clear cell carcinoma | 12 | Olympus | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 8 | 52 | F | 38 | Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 9 | 67 | M | 22 | Clear cell carcinoma | 7 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 10 | 78 | F | 20 | Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 11 | 58 | M | 30 | Chromophobe carcinoma | 0 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 12 | 61 | F | 26 | Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 13 | 56 | M | 14 | Clear cell carcinoma | 9+0 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Positive | Positive |

| 14 | 57 | M | 35 | Clear cell carcinoma | 7 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Positive | Positive |

| 15 | 56 | M | 50 | Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | KARL STORZ | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| 16 | 61 | M | 13 | Clear cell carcinoma | 7 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 17 | 71 | M | 22 | Clear cell carcinoma | 9 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 18 | 76 | M | 40 | Chromophobe carcinoma | 6 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 19 | 57 | M | 35 | Clear cell carcinoma | 6 | KARL STORZ | Negative | Negative | Positive |

5-ALA:5-aminolevulinic acid

In most cases, fluorescence was not observed intraoperatively (Fig. 1a and b, Cases #8 and #13). During intraoperative fluorescence observation, only one case exhibited fluorescence before renal artery clamping (Case #15) (Fig. 1c). However, when examined ex vivo in a dark box, additional cases showed fluorescence in both tumor and normal tissues (Cases #13, #14, and #15) (Fig. 1d). These findings highlight differences in fluorescence visualization between intraoperative and ex vivo conditions. In two cases (Cases #8 and #16), positive fluorescence reactions were observed in the tumor tissues, while the normal tissues showed no fluorescence ex vivo (Fig. 1e). Conversely, in one case (Case #19), fluorescence was negative in the tumor tissue but positive in the normal tissue ex vivo (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative and ex vivo fluorescence observations using 5-ALA. (a and b) Representative intraoperative fluorescence observations under white and blue light excitation (Cases #8 and #13). The left images show the tumors under white light, while the right images present the same areas under blue light excitation. The red circles indicate the tumor regions. (a) Case #8. (b) Case #13. (c) Intraoperative fluorescence observation under blue light excitation (Case #15). The image shows the tumor’s red fluorescence with the da Vinci surgical light turned off. (d) Ex vivo fluorescence observation under blue light excitation (Case #15). The red circles indicate four normal tissue regions that exhibit fluorescence. (e) Ex vivo fluorescence observation under blue light excitation (Case #16). The left image shows normal tissue, while the right image presents tumor tissue exhibiting fluorescence. (f) Ex vivo fluorescence observation under white and blue light excitation (Case #19). The left image shows the specimen under white light, while the right image presents the same area under blue light excitation. The red arrow indicates the tumor region, and the red circle marks the normal tissue exhibiting fluorescence

PPIX accumulation and its association with tumor fluorescence

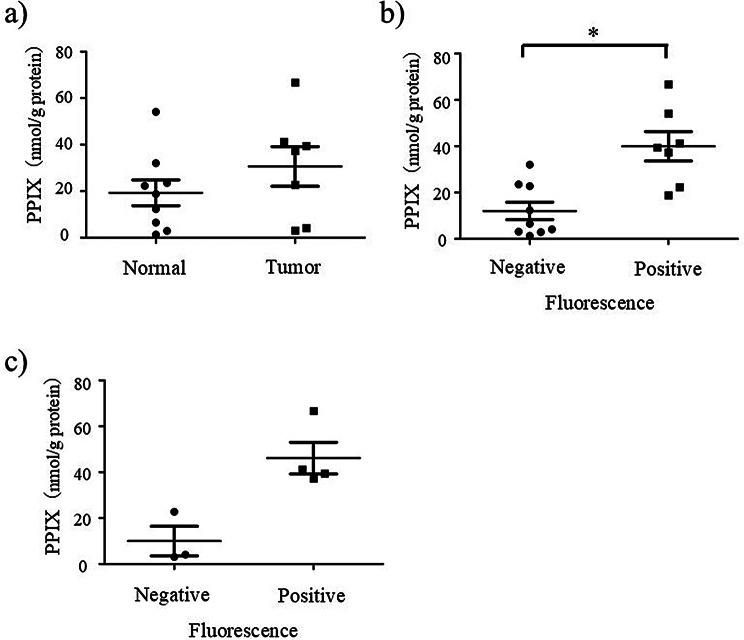

Given that fluorescence responses were also observed in the normal tissues, the concentrations of 5-ALA and PPIX in the tumor and the normal tissues were measured by HPLC. Table 3 shows the accumulation of 5-ALA and PPIX in the excised tissue specimens of six patients. Figure 2a shows box plots of PPIX in the excised tissue specimens in the tumor and the normal tissues. While median PPIX levels were higher in the tumor tissues than in the normal tissues (37.3 and 18.8 nmol/g protein, respectively), this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.252, Mann-Whitney U test). In the individual cases shown in Fig. 1, PPIX concentrations varied among tumor and normal tissues. In Case #8, PPIX concentrations were 37.3 nmol/g protein in the tumor and 12.3 nmol/g protein in the normal tissue. In Case #13, PPIX concentrations were 4.1 nmol/g protein in the tumor and 21.2 nmol/g protein (mean) in the normal tissue. In Case #15, the tumor exhibited a concentration of 44.8 nmol/g protein (mean), whereas the normal tissue had a concentration of 14.4 nmol/g protein (mean). In Case #16, PPIX concentrations were 41.2 nmol/g protein in the tumor and 2.9 nmol/g protein in the normal tissue. The median PPIX concentrations in fluorescence-positive and fluorescence-negative tissues were 39.4 and 6.5 nmol/g protein, respectively, demonstrating a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0052, Mann-Whitney U test, as shown in Fig. 2b). In the tumor tissues, the median concentrations of PPIX were 44.3 and 4.1 nmol/g protein in fluorescence-positive and fluorescence-negative cases, respectively. Statistical significance was not reached, possibly due to the small sample size (p = 0.057, Mann-Whitney U test, as shown in Fig. 2c). However, PPIX concentrations tended to be higher in fluorescence-positive tumors than in fluorescence-negative ones.

Table 3.

Concentrations of 5-ALA and PPIX in the normal and the tumor tissue of selected six cases

| No. | Case | Tissues | Fluorescence | Administration time of 5-ALA prior to skin incision (hour) |

Tissue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-ALA | PPIX | |||||

| [umol/g protein] | [nmol/g protein] | |||||

| 1 | Case6 | Normal | - | 0 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| 2 | Tumor | - | 0.6 | 3.1 | ||

| 3 | Case8 | Normal | - | 7 | 0.4 | 12.3 |

| 4 | Tumor | + | 0.4 | 37.3 | ||

| 5 | Case13 | Normal | - | 9 + 0 | 0.2 | 23.5 |

| 6 | Normal | + | 0.3 | 18.8 | ||

| 7 | Tumor | + | 0.1 | 4.1 | ||

| 8 | Case14 | Normal | - | 7 | 1.1 | 32.0 |

| 9 | Normal | + | 1.3 | 54.1 | ||

| 10 | Tumor | + | 0.5 | 39.4 | ||

| 11 | Case15 | Normal | - | 7 | 0.3 | 6.5 |

| 12 | Normal | + | 0.4 | 22.3 | ||

| 13 | Tumor | - | 0.5 | 22.8 | ||

| 14 | Tumor | + | 1.2 | 66.7 | ||

| 15 | Case16 | Normal | - | 7 | 0.1 | 2.9 |

| 16 | Tumor | + | 0.6 | 41.2 | ||

Fig. 2.

Box plot of PPIX concentrations in the normal and the tumor tissues measured by HPLC. (a) PPIX in the normal and the tumor tissues (mean ± standard deviation): 19.3 ± 16.6 and 30.7 ± 22.6 nmol/g protein respectively (p = 0.252), (b) PPIX in the fluorescence negative and positive tissues (mean ± standard deviation): 12.1 ± 11.3 and 40.0 ± 16.8 nmol/g protein respectively (* p < 0.05) (c) PPIX in the tumor tissues with negative and positive fluorescence (mean ± standard deviation): 46.2 ± 11.1 and 46.2 ± 13.8 nmol/g protein, respectively, (p = 0.057)

Discussion

It is essential to determine the appropriate resection line between the tumor and the normal parenchyma in partial nephrectomy. Tumors embedded within the renal parenchyma represent a surgical technical challenge in terms of tumor identification because of the lack of visual cues on the tumor surface. Therefore, there is a need for more effective methods to accurately identify resection lines, particularly in challenging cases where tumors are deeply embedded in renal parenchyma. 5-ALA-mediated PPIX fluorescence detection of malignant tumors has been reported to be a reliable tool for improving tumor diagnosis. Thus, we investigated whether 5-ALA-mediated PDD could visualize the resection line in RAPN.

5-ALA as a photosensitizer for PDD for malignant tumors was first reported in 1987 [3]. In urology, Inoue et al. reported the efficacy and safety of this approach for bladder cancer in 2016. Cystoscopy was performed approximately 180–240 min after oral administration of 5-ALA in 235 patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer [17]. While Specificity and positive predictability were lower than using a white light (WL) source, sensitivity was higher with a fluorescent light (FL) source than with a WL source. Moreover, sensitivity increased in a dose-dependent manner with a FL-source. The proportion of patients with tumors detected by FL-cystoscopy, was highest in patients who received 5-ALA at ≥ 20 mg/kg/body. The only adverse drug reaction observed was grade 1 pruritus in 1 patient (0.6%).

Previous research by Hoda and Popken reported a fluorescence detection rate of 95.1% (58/61 cases) in renal tumors using 5-ALA-mediated PDD during LPN [15]. They also reported a false-negative rate of 4.9% (3/66 cases) and a false-positive rate of 1.3% (1/77 cases), suggesting that 5-ALA fluorescence was highly reliable in their cohort. In contrast, our study observed fluorescence in only one out of 19 cases intraoperatively, indicating significant variability in 5-ALA-induced fluorescence for renal tumors. Several factors could account for this discrepancy, including differences in 5-ALA administration timing and fluorescence detection systems. Hoda and Popken administered 1.5 g of 5-ALA four hours before surgery, while our study utilized a weight-based dosage (20 mg/kg) with varying administration times, which may have affected PPIX accumulation in tumor tissues. Furthermore, their study used a different laparoscopic imaging system, and differences in camera sensitivity may have influenced fluorescence detection. These methodological differences highlight the need to further optimize 5-ALA-PDD protocols in renal cancer surgery. Additionally, in three cases, fluorescence was observed in the normal tissues surrounding the tumors ex vivo. Discrepancies between intraoperative and ex vivo fluorescence may be due to limited tissue penetration, differences in oxygenation, and background light interference during surgery. Ex vivo imaging in a controlled dark environment enhances fluorescence detection. Optimizing real-time imaging conditions could improve 5-ALA-guided tumor visualization.

The fluorescence response in both tumor and normal tissues can be attributed to multiple factors. Since fluorescence response was detected in both the tumor and the normal tissues, the accumulation of 5-ALA and PPIX was measured in both tissue types. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report measurements of 5-ALA and PPIX concentrations in tumor and normal tissues within the kidney. Although the accumulation of PPIX measured by HPLC tended to be higher in the tumor tissues than in the normal tissues, there were instances where accumulation was also notably high in the normal tissues, as shown in Table 3.

One possible explanation for this observation is the variability among renal cancer cell types, as demonstrated by Howley et al. Using five RCC cell lines (786-O, 769-P, A-704, Caki-1, and Caki-2) and the non-tumor renal cell line HK-2, they measured intracellular PPIX levels after ALA incubation [18]. Among the RCC cell lines, only A-704 showed significantly higher intracellular PPIX levels than HK-2, which highlights substantial variability. This variability was attributed to differences in ferrochelatase (FECH) activity and the PPIX efflux transporter ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2). They concluded that inhibiting ABCG2 could potentially enhance intracellular PPIX concentrations, improving its fluorescence and utility for tumor detection. Howley et al. also observed significant differences in FECH activity among RCC cell lines [19]. FECH, a key enzyme in the heme biosynthesis pathway, converts PPIX to heme, and its activity strongly influences intracellular PPIX levels. While all RCC cell lines had higher maximum catalytic rates (Vmax) than HK-2, no consistent pattern was observed for substrate affinity (Km). These findings suggest that RCC cells may efficiently convert PPIX to heme, reducing its availability for fluorescence detection. This finding aligns with our results, where no significant differences in PPIX concentration were observed between normal and tumor tissues. Therefore, developing combination therapies that enhance PPIX fluorescence intensity, such as ABCG2 inhibitors, could potentially improve the identification of tumor localization in renal cancer using PPIX fluorescence.

In addition to cellular factors, organ-level characteristics may also play a role. Van den Boogert et al. demonstrated differences in the accumulation of 5-ALA and PPIX in different organs in rats [14]. Specifically, they found that the 5-ALA concentration was highest in the kidney, bladder, and urine, and porphyrins accumulated mainly in the duodenal aspirate, jejunum, liver, and kidney. Maximal porphyrin concentration was observed in most tissues 2–3 h after administration. Twenty hours post-administration, porphyrin concentrations in all tissues except the kidney returned to background levels. However, a relatively high basal concentration of porphyrins was consistently found in the kidney. These findings suggest that this characteristic of the kidney may have contributed to the accumulation of PPIX in normal tissues in our study, making it potentially challenging to identify the appropriate resection line.

Due to the nature of renal cancer treatment, it is imperative to excise the tumor en bloc. Therefore, determining appropriate resection lines requires a clear distinction between tumor and normal tissues. This implies that in photodynamic diagnosis (PDD), both high positive and negative predictive values are essential in renal cancer. Currently, in the clinical application of bladder cancer, PDD with 5-ALA exhibits high sensitivity but does not achieve particularly high positive or negative predictive values. This indicates that 5-ALA-based PDD may be inadequate for determining resection lines in renal cancer.

On the other hand, differences in the visualization of the fluorescence response could be attributed to variations in the camera systems used. While the Olympus camera system failed to detect fluorescence, the Karl Storz camera system, which is specialized for PDD, provided better resolution. It is still being determined whether fluorescence was not detected because of the camera systems or the low level of PPIX concentrations. This is because the accumulations of PPIX were tested in 1 (Case #6) of 7 cases imaged with the Olympus camera system, and the concentration of PPIX was low in both the tumor and the normal tissue.

In four cases, fluorescence was confirmed on the surface of the tumor ex vivo but not in vivo. This suggests that the concentrations of PPIX in RCC might not be high enough to penetrate the surface of the tumor. Honda et al. reported that the depth at which the irradiated power density was reduced to 37% (about one-third) was approximately 0.3 mm under excitation wavelengths near 400 nm, using a mouse breast cancer cell line. However, they also showed that the depth of light differs slightly, depending on the tissue type [20]. Increasing the camera’s sensitivity in the future might allow for the detection of fluorescence reactions. Even in the four cases showing red fluorescence emission, the fluorescence reaction’s intensity was insufficient to determine the resection margin.

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent dye that binds to plasma proteins and remains within the vasculature. Clinically, it is primarily used for assessing vascular flow and blood supply. Cao et al. reported that nephron-sparing surgery (partial nephrectomy) using ICG and near-infrared II (NIR-II) fluorescence imaging was effective in achieving complete resection of cystic renal masses (CRMs), with no cases of positive surgical margins [21]. However, ICG primarily highlights vascular structures rather than directly visualizing tumor cells, as its fluorescence depends on blood flow rather than tumor-specific accumulation. In contrast, 5-ALA-PDD targets PPIX, a fluorescent compound selectively accumulated in malignant cells. Unlike ICG, which provides indirect information on tumor location based on blood supply, 5-ALA-PDD enables direct visualization of tumors by selectively marking cancerous cells. This distinction suggests that 5-ALA-PDD may offer a more tumor-specific imaging approach compared to perfusion-based imaging with ICG.

Limitations of the current work and future perspectives

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size (n = 19) limits the statistical power of our findings. In particular, only two cases of chromophobe RCC were included, making subtype-specific analysis unfeasible. Because clear cell RCC is characterized by high lipid content and angiogenesis, while chromophobe RCC exhibits distinct mitochondrial and metabolic properties, differences in PPIX metabolism between subtypes are plausible. Future studies with larger cohorts should explore these metabolic differences to refine the clinical application of 5-ALA-PDD in renal cancer. Second, differences in fluorescence imaging systems (Olympus vs. Karl Storz) may have influenced fluorescence detection. Although standardized observation protocols were employed, direct cross-validation between systems was not conducted, which could introduce variability in fluorescence intensity measurements. Future studies should use a single validated imaging system or conduct cross-validation to ensure device comparability. Moreover, the potential adverse effects of 5-ALA limited patient enrollment. This challenge underscores the need for further optimization to improve patient safety and acceptance in clinical settings.

Considering the current limitations of PPIX fluorescence in renal cell carcinoma, immediate clinical application of 5-ALA image-guided surgery remains challenging and requires further investigation. Variability in fluorescence intensity, background accumulation in normal renal tissues, and the lack of standardized imaging systems limit its widespread adoption. Moreover, the optimal timing of 5-ALA administration for renal cell carcinoma remains unclear, as fluorescence contrast between tumor and normal renal tissue has not been fully established. Although our study did not demonstrate sufficient intraoperative fluorescence to reliably guide resection margins, it provides valuable insight into the technical and biological barriers that must be addressed for successful implementation of 5-ALA-PDD in RCC surgery. Importantly, the observed variability in PPIX accumulation suggests that several modifiable factors—such as administration timing, imaging conditions, and tumor-specific metabolism—may influence diagnostic performance.

Future research should aim to optimize these factors through both preclinical and clinical investigations. For example, studies using murine RCC models could evaluate the efficacy of ABC transporter inhibitors (e.g., ABCG2 inhibitors) in enhancing tumor-specific PPIX accumulation. Determining optimal 5-ALA dosing and timing based on pharmacokinetics will also be essential for maximizing fluorescence contrast. Given the kidney’s natural tendency to accumulate PPIX in normal tissue, protocols designed to increase tumor-to-background fluorescence ratios are particularly important. Furthermore, improvements in imaging sensitivity and standardization of detection protocols will be vital for enhancing reproducibility and clinical reliability. While our study was exploratory and limited in sample size, we believe that with continued refinement, 5-ALA fluorescence imaging holds promise as a supportive tool for margin assessment in RCC surgery.

Conclusions

After systemic administration of 5-ALA, RCC lesions rarely exhibited detectable fluorescence under intraoperative excitation light in this study. Both tumor and normal tissues showed heterogeneous PPIX concentrations, leading to variable fluorescence intensities and limiting the ability to clearly distinguish tumor margins during surgery. While this study did not demonstrate the effectiveness of PDD for resection margin identification in RAPN, the findings underscore key challenges, such as optimal dosing timing, imaging sensitivity, and tumor-specific fluorescence dynamics, that require further investigation. With continued refinement of imaging technology, fluorescence-enhancing strategies, and administration protocols, 5-ALA-PDD could still have potential as a supportive tool in RCC surgery.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the provision of 5-ALA supplied by FBI Pharma, as well as their support in measuring the tissue concentrations of 5-ALA and PPIX.

Abbreviations

- ABCG2

ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2

- ALA

5-aminolevulinic acid

- DMF-IPA

N-Dimethylformamide-2-propanol

- FL

Fluorescent-light

- FECH

ferrochelatase

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- ICG

Indocyanine green

- LPN

Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy

- NIR

Near-infrared

- NIR-II

Near-infrared II

- PDD

Photodynamic diagnosis

- PPIX

Protoporphyrin IX

- RAPN

Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- WL

White light

Author contributions

TM contributed both collected materials and data and wrote the main manuscript. IS, RS, AF, YT, YS, and TO provided the clinical cases. MK designed the clinical research program and revised the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki on Human Research Ethics standards and was approved by the Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval no. 15037) and has been conducted since May 17, 2016. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gettman MT, Blute ML, Chow GK, Neururer R, Bartsch G, Peschel R. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: technique and initial clinical experience with davinci robotic system. Urology. 2004;64(5):914–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pottier RH, Chow YF, LaPlante JP, Truscott TG, Kennedy JC, Beiner LA. Non-invasive technique for obtaining fluorescence excitation and emission spectra in vivo. Photochem Photobiol. 1986;44(5):679–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik Z, Lugaci H. Destruction of erythroleukaemic cells by photoactivation of endogenous porphyrins. Br J cancer. 1987;56(5):589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kennedy JC, Pottier RH, Pross DC. Photodynamic therapy with endogenous protoporphyrin IX: basic principles and present clinical experience. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1990;6(1–2):143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedwell J, MacRobert AJ, Phillips D, Bown SG. Fluorescence distribution and photodynamic effect of ALA-induced PP IX in the DMH rat colonic tumour model. Br J Cancer. 1992;65(6):818–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stummer W, Stocker S, Wagner S, Stepp H, Fritsch C, Goetz C, Goetz AE, Kiefmann R, Reulen HJ. Intraoperative detection of malignant gliomas by 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrin fluorescence. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(3):518–25. discussion 525– 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyajima K, Hirata M, Yoshida T, Kosaka H, Okayama A. Study on measurement of delta-aminolevulinic acid in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994;654(2):165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kriegmair M, Baumgartner R, Knüchel R, Stepp H, Hofstädter F, Hofstetter A. Detection of early bladder cancer by 5-aminolevulinic acid induced porphyrin fluorescence. J Urol. 1996;155(1):105–9. discussion 109–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki S, Nagumo Y, Kojo K, Ikeda A, Isoda B, Yamaguchi A, Tanuma K, Nitta S, Shiga M, Kawahara T, et al. Variations in the diagnostic performance of transurethral resection of bladder tumor with photodynamic diagnosis according to surgical experience: A retrospective, single-center study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2025;51:104429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sano T, Yoshida T, Nakamoto T, Ohe C, Taniguchi H, Yanishi M, Kinoshita H. Diagnostic performance of photodynamic diagnosis with oral 5-aminolevulinic acid for upper tract- and bladder urothelial carcinoma: a single-centre, retrospective analysis. World J Urol. 2024;42(1):389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eatz TA, Eichberg DG, Lu VM, Di L, Komotar RJ, Ivan ME. Intraoperative 5-ALA fluorescence-guided resection of high-grade glioma leads to greater extent of resection with better outcomes: a systematic review. J Neurooncol. 2022;156(2):233–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaak D, Sroka R, Khoder W, Adam C, Tritschler S, Karl A, Reich O, Knuechel R, Baumgartner R, Tilki D, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of prostate cancer using 5-aminolevulinic acid–first clinical experiences. Urology. 2008;72(2):345–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyake M, Tanaka N, Ohnishi K, Nakai Y, Anai S, Yamaki K, Asakawa I, Nishimura N, Fujii T, Isohashi F, et al. Oral 5-aminolevulinic acid for patients with localized prostate Cancer undergoing Low-dose-rate brachytherapy: AMBER trial. Vivo. 2024;38(6):3091–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Boogert J, van Hillegersberg R, de Rooij FW, de Bruin RW, Edixhoven-Bosdijk A, Houtsmuller AB, Siersema PD, Wilson JH, Tilanus HW. 5-Aminolaevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX accumulation in tissues: pharmacokinetics after oral or intravenous administration. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;44(1):29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoda MR, Popken G. Surgical outcomes of fluorescence-guided laparoscopic partial nephrectomy using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX. J Surg Res. 2009;154(2):220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondo M. Porphyrins in urine, blood, and feces and 6-aminolevulinic acid and Porphobilinog (Japanese). Jpn J Clin Med. 1995;53:1364–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Matsuyama H, Fujimoto K, Hirao Y, Watanabe H, Ozono S, Oyama M, Ueno M, Sugimura Y, Shiina H, et al. The clinical trial on the safety and effectiveness of the photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer using fluorescent light-guided cystoscopy after oral administration of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA). Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2016;13:91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howley R, Mansi M, Shinde J, Restrepo J, Chen B. Evaluation of aminolevulinic acid-mediated protoporphyrin IX fluorescence and enhancement by ABCG2 inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2020;211:112017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howley R, Mansi M, Shinde J, Restrepo J, Chen B. Analysis of renal cell carcinoma cell response to the enhancement of 5-aminolevulinic Acid-mediated protoporphyrin IX fluorescence by Iron chelator deferoxamine. Photochem Photobiol. 2023;99(2):787–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda N, Kariyama Y, Hazama H, Ishii T, Kitajima Y, Inoue K, Ishizuka M, Tanaka T, Awazu K. Optical properties of tumor tissues grown on the Chorioallantoic membrane of chicken eggs: tumor model to assay of tumor response to photodynamic therapy. J Biomed Opt. 2015;20(12):125001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao C, Deng S, Wang B, Shi X, Ge L, Qiu M, Zhang F, Lu M, Ma L, Chi C, et al. Intraoperative near-infrared II window fluorescence imaging-assisted nephron-sparing surgery for complete resection of cystic renal masses. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(10):e604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.