Abstract

Background

Detection of DNA methylation biomarkers in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has great clinical potential for cancer management, but there is a high need for method optimization and standardization. Bisulfite conversion of DNA is the gold-standard pre-treatment method for DNA methylation analyses, but causes also DNA fragmentation and loss. Enzymatic conversion of DNA represents a promising alternative due to the more gentle treatment minimizing damage to DNA. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare enzymatic and bisulfite conversion to identify the best pre-treatment method for detecting DNA methylation biomarkers in cfDNA from plasma using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR).

Results

The performance of the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit (both the full kit intended for sequencing and the sub-component NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Conversion Module) and the EpiTect Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit was evaluated and compared using normal cfDNA and tumor cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients. The cytosine conversion efficiency was 99–100% for both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion. Enzymatic conversion resulted in longer DNA fragments with higher peak fragment sizes compared to bisulfite conversion, but the DNA recovery was considerably lower after enzymatic conversion (34–47%) compared to bisulfite conversion (61–81%). For enzymatic conversion, the full kit gave slightly better DNA recovery than the conversion module. A comparison of five magnetic bead brands, as well as several different magnetic bead-to-sample ratios revealed no major improvements in DNA recovery for the enzymatic conversion. DNA methylation of the biomarker BCAT1 was detected at similar rates in parallel tumor cfDNA samples pre-treated with either enzymatic or bisulfite conversion. However, enzymatic conversion resulted in lower number of positive droplets for both target and control ddPCR assays, in line with the lower DNA recovery after conversion.

Conclusions

Based on a thorough evaluation of enzymatic and bisulfite conversion of cfDNA using ddPCR, bisulfite conversion emerges as the best pre-treatment method due to higher DNA recovery after conversion and higher number of positive droplets in the ddPCR reactions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13148-025-01901-4.

Keywords: Enzymatic conversion, Enzymatic Methyl-seq, Bisulfite conversion, DNA methylation, Liquid biopsy, Plasma, Circulating cell-free tumor DNA, cfDNA, ctDNA, ddPCR, Magnetic beads, Colorectal cancer

Background

DNA methylation alterations in liquid biopsies, such as plasma samples, have great clinical potential as cancer biomarkers. The combination of DNA methylation, which is an early and common event in cancer development [1], and liquid biopsies, which offer a non-biased and easy accessible source for biomarker discovery, provides an excellent opportunity for cancer management including early detection, diagnosis and monitoring of tumor recurrence and response to therapy. Still, few DNA methylation biomarkers are currently in clinical use. One contributing factor may be lack of optimized and standardized methods for accurate detection and analyses of biomarkers in plasma samples.

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) technology allows highly sensitive detection of minimal amounts of the target of interest and is a cost-efficient method that is easy to perform, standardize [2, 3] and implement into clinical practice. As such, it is a highly suitable method for analyzing biomarkers in plasma samples, including DNA methylation alterations. Like most DNA methylation analyses, ddPCR requires a form of pre-treatment of the DNA to distinguish methylated cytosines from unmethylated cytosines. Bisulfite conversion is considered the gold-standard for this type of analysis [4], since it is robust and efficient. However, bisulfite conversion also causes DNA damage due to harsh conditions with low pH and high temperature, resulting in fragmentation and loss of DNA for downstream analyses [5]. This is particularly challenging for scarce DNA sources such as circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in plasma, which is naturally fragmented and normally present in low amounts.

Alternative pre-treatment methods based on enzymatic conversion of DNA are increasingly being used due to the more gentle treatment minimizing damage to DNA [6, 7]. These enzymatic modifications have particularly been incorporated in high-throughput sequencing methods, where the longer DNA fragments obtained with enzymatic conversion is a clear advantage [6–11]. Indeed, several studies have performed enzymatic DNA methylation sequencing of large series of cfDNA from plasma from cancer patients, with promising results [8, 12–14]. On the other hand, enzymatic conversion has also been shown to result in lower cytosine conversion efficiency and DNA recovery rates compared to bisulfite conversion when using multiplex quantitative real-time PCR [15], indicating that the most optimal conversion method may depend on the type of subsequent DNA methylation analysis.

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare enzymatic and bisulfite conversion to identify the best pre-treatment method for detecting DNA methylation biomarkers in cfDNA from plasma using ddPCR. We have compared the performance of the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit (both full kit intended for sequencing and the sub-component NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Conversion Module) and the EpiTect Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit, which was identified to be the most optimal for bisulfite conversion of cfDNA in our previous study [16]. The kits were evaluated based on cytosine conversion efficiency, DNA fragmentation and DNA recovery after conversion and DNA methylation biomarker detection, using both normal cfDNA and tumor cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients, as well as DNA from the colorectal cancer cell line RKO fragmented to mimic cfDNA.

Results

Comparison of enzymatic and bisulfite conversion kits: cytosine conversion efficiency, DNA fragmentation, DNA recovery and DNA methylation biomarker detection

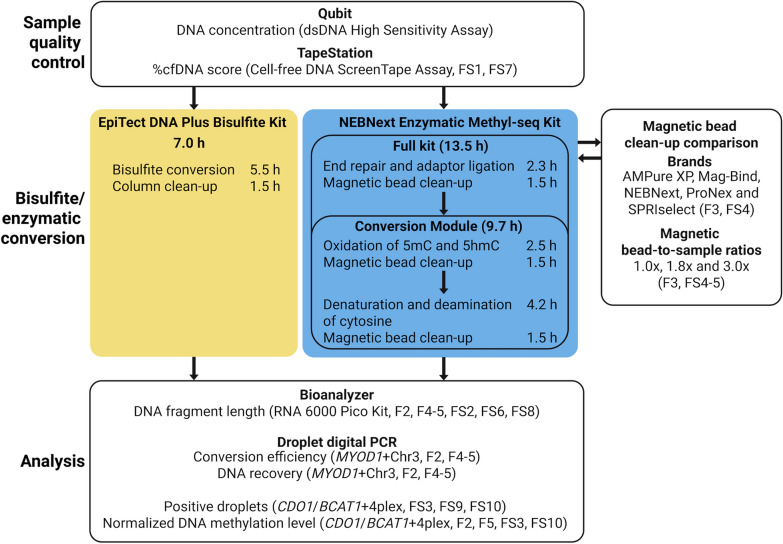

For enzymatic conversion of cfDNA for DNA methylation analysis using ddPCR, both the full NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit intended for high-throughput sequencing (hereafter termed full kit) and the sub-component NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Conversion Module (hereafter termed conversion module) of the full kit were tested. For bisulfite conversion, the EpiTect Plus Bisulfite Kit was selected since this kit showed highest performance in our previous comparison of five commercially available bisulfite conversion kits [16]. Figure 1 shows an overview of the two conversion methods and the overall workflow for this study.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the enzymatic and bisulfite conversion methods and the overall workflow for this study. The time is based on processing 12 samples. F; figure and FS; supplementary figure

Isolated cfDNA from a pool of plasma from healthy individuals (Supplementary Fig. 1) was used for comparing the enzymatic and bisulfite conversion kits, with an input amount of 50 ng with technical replicates. In addition, DNA from the colorectal cancer cell line RKO (fragmented to mimic the size distribution of cfDNA; Supplementary Fig. 1) was used to compare detection of biomarkers, with an input amount of 100 ng with technical replicates. The cytosine conversion efficiency was determined using ddPCR with the Chr3 and MYOD1 assays as previously described [17], where the Chr3 assay detects unconverted DNA and the MYOD1 assay detects converted DNA. The conversion efficiency was 100% using bisulfite conversion for both the normal cfDNA pool and fragmented RKO DNA (Fig. 2A). For enzymatic conversion, the conversion efficiency was on average 99.6% using the full kit and 99.9% using the conversion module for the normal cfDNA. For fragmented RKO DNA, the conversion efficiency was on average 99.2% using the full kit and 97.1% using the conversion module.

Fig. 2.

Enzymatic and bisulfite conversion of normal cfDNA and fragmented RKO DNA. A Average conversion efficiency, B average peak fragment size of normal cfDNA and fragmented RKO DNA treated with enzymatic conversion and bisulfite conversion, C average DNA recovery and D average normalized DNA methylation level of the biomarker CDO1 for fragmented RKO DNA treated with enzymatic and bisulfite conversion. BC; bisulfite conversion. EC; enzymatic conversion (full kit) and EC-CM; enzymatic conversion (conversion module). *The exact fragment size may not be correct since the converted DNA is analyzed using a Bioanalyzer RNA assay. **The sequencing adapter length has been subtracted for comparison with the conversion module and bisulfite conversion

The degree of DNA fragmentation was evaluated by fragment length analyses using electrophoretic separation. For both the normal cfDNA pool and fragmented RKO DNA, enzymatic conversion resulted in longer DNA fragments with slightly higher average peak fragment sizes after treatment compared to bisulfite conversion (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 2).

The DNA recovery after enzymatic and bisulfite conversion was determined using ddPCR with the Chr3 and MYOD1 assays as previously described [17]. For the normal cfDNA, the average recovery was 68% with bisulfite conversion, compared to 38% and 30% with enzymatic conversion with the full kit and conversion module, respectively (Fig. 2C). For fragmented RKO DNA, bisulfite conversion resulted in 51% average recovery, whereas enzymatic conversion resulted in 21% and 5% average recovery with the full kit and conversion module, respectively. Of note, the lower recovery of fragmented RKO DNA compared to normal cfDNA may be a result of the slightly different fragment size distribution (Supplementary Fig. 1).

DNA methylation biomarker detection was performed using ddPCR with the CDO1 and 4Plex assays for the fragmented RKO DNA. DNA methylation of CDO1 was detected using both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion. The resulting normalized methylation levels were on average 61 for bisulfite conversion, 73 for enzymatic conversion with the full kit and 113 for enzymatic conversion with the conversion module (Fig. 2D). There was a noticeable difference in the number of positive droplets in the ddPCR reactions, in line with the marked difference in DNA recovery. Enzymatic conversion resulted in a lower number of positive droplets for both the target gene and the control assay compared to bisulfite conversion. Furthermore, the number of positive droplets was even lower when using the conversion module compared to using the full kit (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Comparison of magnetic bead brands and bead-to-sample ratios for improving DNA recovery for enzymatic conversion

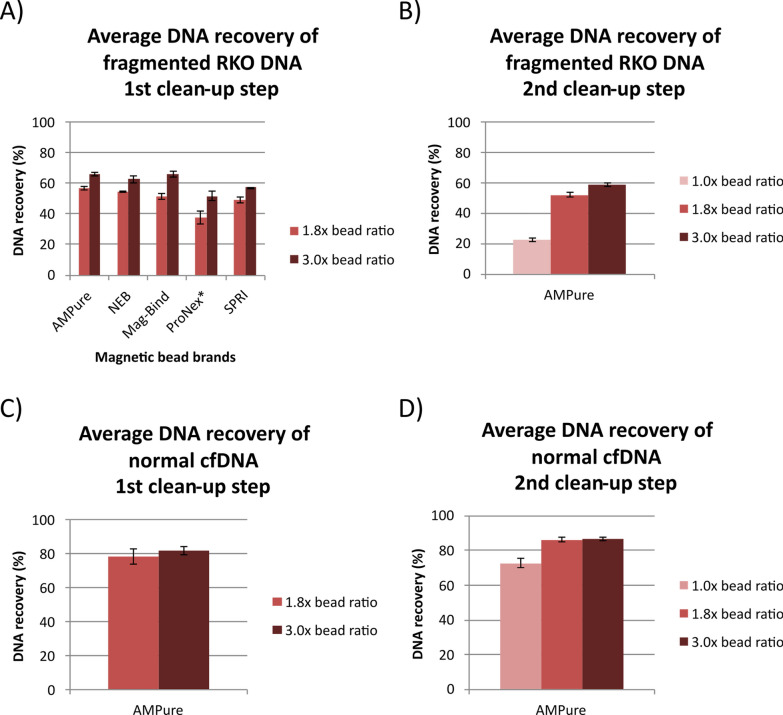

The enzymatic conversion protocol includes two cleanup steps using magnetic beads, where loss of DNA can potentially occur. For the full kit for sequencing, there is a third magnetic bead cleanup step upfront (after adaptor ligation), which is almost identical to the second cleanup step in the conversion protocol. To try to improve the DNA recovery for enzymatic conversion, we tested different magnetic bead brands and different bead-to-sample ratios for the conversion protocol. Five magnetic bead brands were evaluated: AMPure XP, Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS, NEBNext Sample Purification Beads (included in the full kit), ProNex Size-Selective Purification System and SPRIselect. For the first cleanup step in the conversion protocol, 20 ng of fragmented RKO DNA was subjected to magnetic beads capturing using five different bead brands and two bead-to-sample ratios: 1.8x (as specified in the original protocol) and 3.0x. All experiments were performed with technical replicates. The DNA recovery was determined by calculating the percentage difference between the amount of DNA before and after cleanup. Increasing the bead ratio from 1.8 × to 3.0 × resulted in an improvement in the average recovery of fragmented RKO DNA by 9–17% (Fig. 3A). While all bead brands performed well overall, the highest DNA recoveries after cleanup were obtained using the AMPure XP beads, Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS and NEBNext Sample Purification Beads. The AMPure XP beads were selected for further magnetic bead testing. For the second cleanup step, the AMPure XP beads were used to clean up fragmented RKO DNA using bead ratios 1.0x (original in the protocol), 1.8 × and 3.0x. The average recovery was 22% using the original 1.0 × bead ratio and increased to 52% and 59% using bead ratios 1.8 × and 3.0x, respectively (Fig. 3B). Fragment length analyses using electrophoretic separation showed that more of the smaller fragments were retained when using higher bead ratios, expanding the fragment size distribution after cleanup (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

DNA recovery of fragmented RKO DNA and normal cfDNA using different magnetic bead brands and bead-to-sample ratios. Average DNA recovery of fragmented RKO DNA for A first cleanup step using different magnetic bead brands and bead-to-sample ratios and B second cleanup step using AMPure XP beads and different magnetic bead-to-sample ratios. Average DNA recovery of normal cfDNA using AMPure XP beads for C first cleanup step and D second cleanup step using different magnetic bead-to-sample ratios. *For ProNex, recommended higher magnetic bead-to-sample ratios were used corresponding to 1.8 × and 3.0 × ratios

The AMPure XP beads were then used to clean up 20 ng of cfDNA from the normal plasma pool with similar bead-to-sample ratios as for the fragmented RKO DNA. For the first cleanup step in the conversion protocol, the average recovery of normal cfDNA increased from 79% using the original 1.8 × bead ratio to 82% using 3.0 × bead ratio (Fig. 3C). For the second cleanup step, the average recovery increased from 73% using the original 1.0 × bead ratio to 86% using 1.8 × and 87% using 3.0 × bead ratio (Fig. 3D). Fragment length analyses using electrophoretic separation revealed no major differences in the fragment size distribution and average peak fragment size when using higher bead ratios for the normal cfDNA (Supplementary Fig. 5).

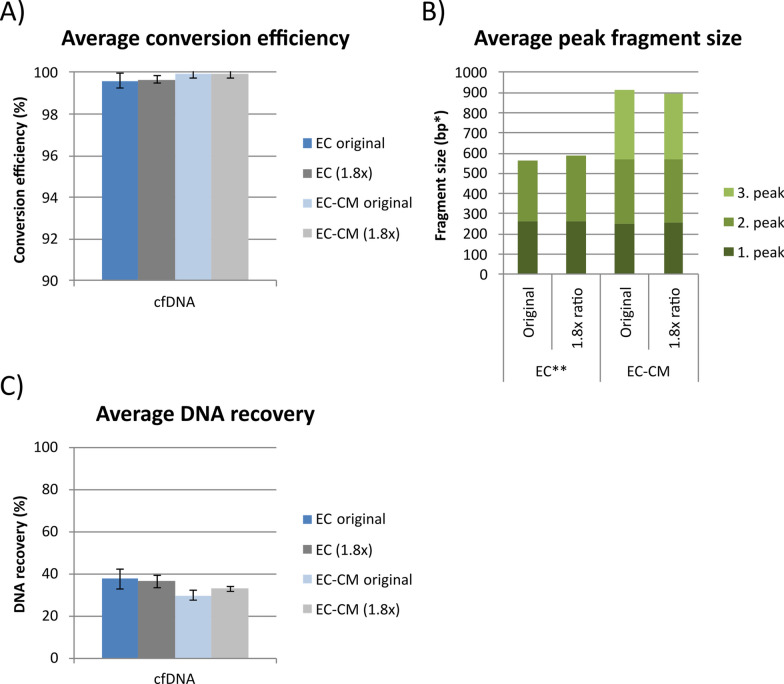

Since the recovery was approximately the same using 1.8 × and 3.0 × bead ratio for normal cfDNA, enzymatic conversion of normal cfDNA was then performed using 1.8 × bead ratio for all cleanup steps for both the full kit and the conversion module to compare this to the original protocols (1.8 × bead ratio for the first and 1.0 × for the second cleanup step). The conversion efficiency remained on average 99.7–99.9% (Fig. 4A) and the fragment length distribution and average peak fragment sizes were similar (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 6) when increasing the magnetic bead-to-sample ratio to 1.8 × for all cleanup steps. Furthermore, the average DNA recovery with 1.8 × bead ratios was highly comparable to the original protocols (Fig. 4C). For the full kit, there was a slight decrease in average DNA recovery of 36% compared to 38% for the original protocol, whereas for the conversion module, there was a slight increase in average DNA recovery of 33% compared to 30% for the original protocol (Fig. 4C). Thus, switching magnetic bead type or adjusting the magnetic bead-to-sample ratios for the enzymatic conversion did not significantly impact on the recovery of cfDNA.

Fig. 4.

Enzymatic conversion of normal cfDNA using different magnetic bead-to-sample ratios. A Average conversion efficiency, B average peak fragment size and C average DNA recovery of normal cfDNA treated with enzymatic conversion using the full kit with original protocol (1.8 × magnetic bead-to-sample ratio for the first and 1.0 × for the second cleanup step) and modified protocol with 1.8 × bead ratio for both cleanup steps. EC; enzymatic conversion (full kit) and EC-CM; enzymatic conversion (conversion module). *The exact fragment size may not be correct since the converted DNA is analyzed using a Bioanalyzer RNA assay. **The sequencing adapter length has been subtracted for comparison with the conversion module and bisulfite conversion

Detection of DNA methylation biomarkers in plasma samples from colorectal cancer patients using enzymatic and bisulfite conversion

Isolated cfDNA from plasma from five colorectal cancer patients with stage IV tumors was used for further comparison of the enzymatic and bisulfite conversion kits. The fragment length distribution of the isolated cfDNA and the %cfDNA score were assessed by electrophoretic analysis. The %cfDNA score varied between 67 and 97%, with most samples having at least 80% cfDNA (Supplementary Fig. 7). Between 8 and 34 ng of cfDNA were used as input for both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion, with technical replicates. For enzymatic conversion, the full kit with the original protocol was used as this gave the highest DNA recovery for normal cfDNA.

The cytosine conversion efficiency was determined using ddPCR with the Chr3 and MYOD1 assays. For bisulfite conversion, four samples showed 100% conversion efficiency and one sample showed on average 99.9% conversion, while for enzymatic conversion, one sample showed 100% and four samples showed a range of 99.0–99.8% average conversion efficiency (Fig. 5A). The degree of DNA fragmentation was evaluated by fragment length analyses using electrophoretic separation. The DNA fragments were longer with higher average peak fragment sizes after enzymatic conversion compared to bisulfite conversion (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. 8). The DNA recovery was determined using ddPCR with the Chr3 and MYOD1 assays. Bisulfite conversion resulted in a range of 61–81% average recovery for the five tumor cfDNA samples, whereas a range of 34–47% average recovery was obtained using enzymatic conversion (Fig. 5C). Thus, the average recovery using bisulfite conversion was 58–91% higher than the corresponding average recovery using enzymatic conversion.

Fig. 5.

Enzymatic and bisulfite conversion of cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients. A Average conversion efficiency, B average peak fragment size, C average DNA recovery and D average normalized methylation level of the biomarker BCAT1 for cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients treated with enzymatic conversion and bisulfite conversion. BC; bisulfite conversion, EC; enzymatic conversion (full kit) and CRC; colorectal cancer. *The exact fragment size may not be correct since the converted DNA is analyzed using a Bioanalyzer RNA assay. **The sequencing adapter length has been subtracted for comparison with the conversion module and bisulfite conversion

DNA methylation biomarker detection was performed using ddPCR with the BCAT1 assay, which is a biomarker used for detection of colorectal cancer recurrence [18, 19], and the 4Plex assay. We have previously shown BCAT1 to be methylated in cfDNA samples from the five colorectal cancer patients included in the current study [16]. DNA methylation of BCAT1 was detected in 4/5 samples using both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion in the present study, with a normalized methylation level range of 0.6–28.8 for bisulfite conversion and 0.7–36.8 for enzymatic conversion (Fig. 5D). There was a noticeable difference in the number of positive droplets in the ddPCR reactions, in line with the marked difference in DNA recovery (Supplementary Fig. 9 and 10). Enzymatic conversion caused a lower number of positive droplets for both the target genes and the control assay compared to bisulfite conversion detection. A summary of the overall results for the tumor cfDNA samples including the strengths and weaknesses of the two conversion methods is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Summary of the results of the evaluation and comparison of the enzymatic and bisulfite conversion methods

Discussion

Droplet digital PCR provides absolute quantification of nucleic acids and offers great potential for detecting DNA methylation biomarkers in liquid biopsies. As such, it is a natural method of choice for targeted analyses of smaller panels of biomarkers in plasma samples. However, to succeed with the development of clinically relevant biomarkers, it is crucial with method optimization and standardization. In the present study, we have evaluated whether enzymatic or bisulfite conversion is the best pre-treatment method for DNA methylation analyses in plasma samples using ddPCR. By analyzing normal cfDNA and tumor cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients, we demonstrate that although enzymatic conversion resulted in similar high cytosine conversion efficiency, longer DNA fragments and higher peak fragment sizes compared to bisulfite conversion, it also resulted in lower DNA recovery and fewer positive droplets for the target genes for all samples tested. Since high DNA recovery and high number of positive droplets are the most important parameters when using ddPCR to detect DNA methylation biomarkers in low-concentrated samples like cfDNA, bisulfite conversion emerges as the better pre-treatment method for this type of analyses.

Several studies have compared enzymatic conversion to bisulfite conversion for high-throughput sequencing, clearly showing the benefits of using enzymatic conversion [6–11]. However, few studies have so far evaluated the two methods in another setting than high-throughput sequencing. Hong et al. compared several bisulfite conversion kits and the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit for enzymatic conversion using multiplex quantitative real-time PCR [15]. They demonstrated that enzymatic conversion resulted in significantly lower degradation of genomic DNA samples, but also in lower DNA recovery rates and conversion efficiency compared to bisulfite conversion [15]. Our results are largely similar to these observations, except that we observed high conversion efficiency for both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion (99–100%) for all samples analyzed. A larger variation of 85–100% conversion efficiency after enzymatic conversion was observed by Hong et al., which was significantly lower than for the bisulfite conversion kits tested [15]. A high-throughput sequencing study has shown that enzymatic methyl-seq was prone to incomplete conversion in specific settings, leading to a false increase of > 1% in methylation rate [8]. Another study also observed that bisulfite conversion performed better than enzymatic conversion in terms of conversion efficiency [20]. However, the conversion efficiency determined in the present study with cfDNA samples was very high and comparable for both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion.

Although the DNA fragments were slightly longer and equally converted, the DNA recovery was considerably lower using enzymatic conversion compared to bisulfite conversion for all samples tested. The average recovery using bisulfite conversion was 58–91% higher than the enzymatic conversion for the tumor cfDNA samples analyzed. The lower recovery was also reflected in the number of positive droplets observed in the ddPCR reactions, with bisulfite conversion giving more positive droplets for both the target and control ddPCR assays compared to the enzymatic conversion. In contrast to this, enzymatic conversion resulted in higher normalized methylation levels than bisulfite conversion for all samples analyzed, with the conversion module giving even higher values than the full kit. This may not be random since the results were quite consistent, but the reason for this seems unclear. Nevertheless, higher DNA recovery and more positive droplets for the target gene, as observed for bisulfite conversion, are crucial, as it increases the chance of detecting DNA methylation alterations present in the small amount of cfDNA available for plasma.

Despite the lower DNA recovery observed after enzymatic conversion, there were no differences in the detection of biomarker methylation for enzymatic and bisulfite conversion in the small panel of tumor cfDNA samples tested. We have previously shown that cfDNA from the five colorectal cancer patients included in the current study all had methylation of BCAT1 [16]. However, in the present study, methylation was detected in only 4/5 samples for both enzymatic and bisulfite conversion. There are several factors that may explain the lack of BCAT1 methylation in one of the samples. First, the input amount of cfDNA in the ddPCR reactions was considerably lower compared to the previous study. Second, the methylation-negative sample was previously shown to have the lowest normalized BCAT1 methylation level of the selected five cfDNA samples [16]. Third, the sample had the lowest % cfDNA score. All these parameters combined probably caused the lack of detection of BCAT1 methylation in this sample. In line with our findings, it has previously been shown that the total input amount of cfDNA is crucial for the sensitivity of mutation detection using ddPCR for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations [21].

There was also a difference in the amount of laboratory work between the two conversion methods. If manual conversion is performed for 12 samples, the workflow is considerably more extensive for the enzymatic conversion, with more hands-on time and almost double the amount of time for the overall process (Fig. 1). Of note, automatic conversion/cleanup, as well as the number of samples, affects the processing time.

In the enzymatic conversion protocol, there are several cleanup steps using magnetic beads where loss of DNA can potentially occur. Our attempts to improve DNA recovery using other types of magnetic beads or magnetic bead-to-sample ratios were not successful, although the initial results indicated that increasing the bead-to-sample ratio could increase the recovery. We also observed a higher DNA recovery when using the full NEBNext kit compared to the conversion module. This difference is most likely due to the variation in resulting fragment sizes between the two protocols. In the full kit protocol, sequencing adapters are attached to the DNA, resulting in longer fragments compared to those produced by the conversion module. These longer fragments are less prone to loss during magnetic bead cleanup, leading to higher DNA recovery. Fragmented RKO DNA, which has a wider size distribution with a higher proportion of shorter fragments compared to cfDNA, is more susceptible to loss during cleanup. This may explain the larger difference in recovery observed between the full kit and the conversion module for fragmented RKO DNA. Importantly, the addition of adapters did not seem to interfere with the ddPCR reactions. Thus, the full NEBNext kit seems to be the better option for ddPCR analyses of cfDNA when using enzymatic conversion, as it provides higher DNA recovery compared to the conversion module.

Conclusions

Based on a thorough evaluation of enzymatic and bisulfite conversion for DNA methylation analyses of cfDNA using ddPCR, bisulfite conversion emerges as the best pre-treatment method due to higher DNA recovery after conversion and higher number of positive droplets in the ddPCR reactions. This increases the chance of detecting DNA methylation biomarkers present in small amounts of cfDNA.

Methods

Samples

Normal plasma was obtained from blood samples from eight voluntary healthy donors. Blood was collected using BD Vacutainer K2E (EDTA) Plus Blood Collection Tubes (Becton Dickinson) and processed within one hour. Plasma was separated from the cellular fraction by two centrifugation steps at 4 °C (1600 g for 10 min followed by 7000 g for 10 min). The plasma samples from all donors were mixed to generate a normal plasma pool, which was further divided in 1 ml aliquots and stored at − 80 °C.

Plasma from blood samples from five colorectal cancer patients was obtained from a consecutive series of primary colorectal cancers collected at the Oslo University Hospital between 2010 and 2016. Blood was collected using BD Vacutainer K2E (EDTA) Plus Blood Collection Tubes, and plasma was separated from the cellular fraction by centrifugation at 1600 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The plasma aliquots were stored at − 80 °C. A visual examination of the plasma samples was performed before isolation of cfDNA to ensure no presence of color changes indicating hemolysis.

DNA was obtained from the colon cancer cell line RKO (CRL-2577, American Type Culture Collection; ATCC). To mimic the size distribution of cfDNA, the RKO genomic DNA was fragmented by sonication, generating a distribution of fragments where 98% were between 50 and 700 bp (%cfDNA score 98) and with a peak size of 173 bp (Supplementary Fig. 1). The fragment size distribution was wider with a less distinctive peak compared to cfDNA, but the fragmented RKO DNA represents a valuable substitute for cfDNA. A large pool of fragmented RKO DNA was made, sufficient for all analyses performed.

cfDNA isolation

The QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (QIAGEN) was used for isolation of cfDNA from plasma since this kit showed highest performance in our previous comparison of three commercially available cfDNA isolation kits [16]. The QIAcube Connect (QIAGEN) was used for automated cleanup according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the normal plasma pool, an input volume of 5 ml was used with the 5 ml protocol. This was repeated and the resulting cfDNA was combined to make a large pool of normal cfDNA, sufficient for all analyses performed. For plasma samples from colorectal cancer patients, one tube containing between 1.5 and 1.8 ml plasma was used for isolation with the 2 ml protocol. Maximum elution volume of 150 µl was used per sample to obtain as much cfDNA as possible from the spin columns. Up-concentration of cfDNA to a volume of 30–40 µl was then performed using Vivacon 500 30,000 MWCO HY Filtrate Tube (Sartorius). DNA concentration of isolated cfDNA was measured using the Qubit Fluorometer and the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The isolated cfDNA was stored at − 20 °C.

Enzymatic conversion

The NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit (full kit) and its sub-component NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Conversion Module (conversion module; New England Biolabs) were used for enzymatic DNA conversion according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The full kit is designed for high-throughput sequencing and includes reagents for enzymatic conversion, end-repair and adaptor ligation. In contrast, the conversion module, which is available separately, contains only the reagents required for enzymatic conversion. AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter) were used for experiments utilizing the conversion module. An input amount of 50 ng for normal cfDNA and 100 ng for fragmented RKO DNA was used, with three technical replicates. For cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients, between 8 and 34 ng isolated cfDNA was used for enzymatic conversion, also with three technical replicates. An elution volume of 20 µl was used, as recommended by the manufacturer. The enzymatically converted DNA was stored at − 20 °C.

Five different magnetic bead brands were evaluated for the magnetic bead cleanup steps in the protocol: AMPure XP, Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS (Omega Bio-tek), ProNex Size-Selective Purification System (Promega), SPRIselect (Beckman Coulter) and NEBNext Sample Purification Beads (New England Biolabs, included in the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit). DNA purification was performed according to the respective manufacturer’s instructions, with an input amount of 20 ng of fragmented RKO DNA with three technical replicates. For ProNex Size-Selective Purification System, higher magnetic bead-to-sample ratios were tested corresponding to 1.8 × and 3.0 × ratio according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bisulfite conversion

The EpiTect Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit (QIAGEN) was used for bisulfite conversion of DNA since this kit showed highest performance in our previous comparison of five commercially available bisulfite conversion kits [16]. Carrier RNA was included to enhance output, and the QIAcube Connect (QIAGEN) was used for automated cleanup according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An input amount of 50 ng for normal cfDNA and 100 ng for fragmented RKO DNA was used, with three technical replicates. For cfDNA samples from colorectal cancer patients, between 8 and 34 ng isolated cfDNA was used for bisulfite conversion, also with three technical replicates. An elution volume of 16 µl was used, as recommended by the manufacturer. The bisulfite converted DNA was stored at − 20 °C.

Fragment length analysis

Fragment length analyses were performed by electrophoretic separation using the 4200 TapeStation Instrument and the 2100 Bioanalyzer Instrument (Agilent). For fragment length analysis of isolated cfDNA and fragmented RKO DNA, the Cell-free DNA ScreenTape Assay (Agilent) was used with the TapeStation. The RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent) was used with the Bioanalyzer for assessing the fragment length of enzymatic and bisulfite converted DNA since this is mainly single-stranded. For comparison of magnetic bead brands and ratios, the High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent) was used with the Bioanalyzer.

Droplet digital PCR

Droplet digital PCR was performed using the QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad) as previously described [3]. To evaluate enzymatic and bisulfite conversion efficiency and DNA recovery, the FAM-labeled “Chr3 assay” and VIC-labeled assay for myogenic differentiation 1 (MYOD1) were used as previously described [17], with modifications tailored for use on the QX200 platform. The Chr3 and MYOD1 assays measure unconverted and converted DNA, respectively, and the assays were run simultaneously.

Two different target assays were used for detection of biomarkers: FAM-labeled target assays for cysteine dioxygenase type 1 (CDO1) [22] and branched chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1) [19]. As a control, the VIC-labeled 4Plex assay [3] was run simultaneously with each target assay. The 4Plex assay comprises of the genes ephrin type A receptor 3 (EPHA3), kelch repeat and BTB domain containing 4 (KBTBD4), pleckstrin homology and FYVE domain containing 1 (PLEKHF1) and synaptotagmin 10 (SYT10), which were selected based on their pericentromeric location and stability in regard to copy number variations [3]. Primers were purchased from BioNordika and probes from Life Technologies, and sequences are given in Supplementary Table 1. For each experiment, the following control samples were included: two DNA methylation-positive controls (Methylated Human DNA Standard, Zymo Research), one DNA methylation-negative control (Human WGA Non-methylated DNA, Zymo Research) and two non-template controls (NTC; water).

Data analysis was performed using QuantaSoft version 1.7.4.0917 (Bio-Rad). An in-house developed algorithm, PoDCall (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/PoDCall.html), was applied for positive droplet calling as previously described [2, 3]. Normalized DNA methylation levels were calculated as previously described [23]. Briefly, the concentration of the methylated target gene was divided by the concentration of the 4plex control (reflecting total DNA input) and multiplied by a factor of 400 to standardize results across experiments. Sample exclusion criteria were low droplet count (total number of droplets < 5000) or low DNA amount (control assay concentration < 10 copies/µl). In addition, the methylation level was set to zero for samples with only one positive droplet for the target gene. All analyses were performed according to the digital MIQE guidelines [24]. The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/15349126.

The cytosine conversion efficiency and DNA recovery were determined using the Chr3 and MYOD1 assays, as previously described [17]. Recovery was calculated by dividing the total number of positive MYOD1 droplets and positive Chr3 droplets of converted DNA by the number of positive Chr3 droplets of unconverted DNA.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ragnhild A. Lothe for the colorectal cancer collaboration.

Abbreviations

- BC

Bisulfite conversion

- cfDNA

Cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- ddPCR

Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EC

Enzymatic conversion

- EC-CM

Enzymatic conversion (conversion module)

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

Author contributions

EMT, GEL and SHK conceived and designed the study. GEL obtained funding and supervised the study. EMT, HP, SBW and SHK contributed in acquisition of the data. EMT and SHK participated in analysis and interpretation of the data. SHK drafted the article. GEL and HMV critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). This work was supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society (project number 216129–2020), the Norwegian Esophageal Cancer Consortium (NORECa, project number 220115–2020) and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (project number 2024032).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/15349126.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South-Eastern Norway (project ID 1.2005.1629 and 2010/1805). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

GEL and HP are named on one granted patent (US11555222B2) and one pending US national application (US/2019/0221286) covering the 4Plex control and PoDCall algorithm, respectively, used in the present study for normalization of DNA methylation ddPCR results. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nishiyama A, Nakanishi M. Navigating the DNA methylation landscape of cancer. Trends Genet. 2021;37:1012–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeanmougin M, Brodal HP, Pharo HD, Vedeld HM, Lind GE. PoDCall: positive droplet calling and normalization of droplet digital PCR DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2023. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharo HD, Andresen K, Berg KCG, Lothe RA, Jeanmougin M, Lind GE. A robust internal control for high-precision DNA methylation analyses by droplet digital PCR. Clin Epigenetics. 2018;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galardi F, De Luca F, Romagnoli D, Biagioni C, Moretti E, Biganzoli L, Di Leo A, Migliaccio I, Malorni L, Benelli M. Cell-Free DNA-methylation-based methods and applications in oncology. Biomolecules. 2020;10(12):1677. 10.3390/biom10121677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka K, Okamoto A. Degradation of DNA by bisulfite treatment. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1912–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Z, Vaisvila R, Hussong LM, Yan B, Baum C, Saleh L, Samaranayake M, Guan S, Dai N, Correa IR Jr, et al. Nondestructive enzymatic deamination enables single-molecule long-read amplicon sequencing for the determination of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine at single-base resolution. Genome Res. 2021;31:291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaisvila R, Ponnaluri VKC, Sun Z, Langhorst BW, Saleh L, Guan S, Dai N, Campbell MA, Sexton BS, Marks K, et al. Enzymatic methyl sequencing detects DNA methylation at single-base resolution from picograms of DNA. Genome Res. 2021;31:1280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo P, Zheng H, Li Y, Li Y, Xiao Y, Zheng J, Zhu X, Xu H, He Z, Zhang Q, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma detection via targeted enzymatic methyl sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA. Clin Epigenetics. 2023;15:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubert JN, Iannuccelli N, Cabau C, Jacomet E, Billon Y, Serre RF, Vandecasteele C, Donnadieu C, Demars J. Detection of DNA methylation signatures through the lens of genomic imprinting. Sci Rep. 2024;14:1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison J, Koeman JM, Johnson BK, Foy KK, Beddows I, Zhou W, Chesla DW, Rossell LL, Siegwald EJ, Adams M, et al. Evaluation of whole-genome DNA methylation sequencing library preparation protocols. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2021;14:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trinidad EM, Juan-Ribelles A, Pisano G, Castel V, Canete A, Gut M, Heath S, Font de Mora J. Evaluation of circulating tumor DNA by electropherogram analysis and methylome profiling in high-risk neuroblastomas. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1037342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim M, Park J, Seonghee O, Jeong BH, Byun Y, Shin SH, Im Y, Cho JH, Cho EH. Deep learning model integrating cfDNA methylation and fragment size profiles for lung cancer diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:14797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YJ, Jeon H, Jeon S, Lee SH, Kim C, Ahn JH, Um H, Woo YJ, Jeong SH, Kim Y, et al. A method for early diagnosis of lung cancer from tumor originated DNA fragments using plasma cfDNA methylome and fragmentome profiles. Mol Cell Probes. 2022;66:101873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Xu J, Chen C, Lu Z, Wan D, Li D, Li JS, Sorg AJ, Roberts CC, Mahajan S, et al. Multimodal epigenetic sequencing analysis (MESA) of cell-free DNA for non-invasive colorectal cancer detection. Genome Med. 2024;16:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong SR, Shin KJ. Bisulfite-converted DNA quantity evaluation: a multiplex quantitative real-time PCR system for evaluation of bisulfite conversion. Front Genet. 2021;12:618955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kresse SH, Brandt-Winge S, Pharo H, Flatin BTB, Jeanmougin M, Vedeld HM, Lind GE. Evaluation of commercial kits for isolation and bisulfite conversion of circulating cell-free tumor DNA from blood. Clin Epigenetics. 2023;15:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orntoft MBW, Jensen SO, Hansen TB, Bramsen JB, Andersen CL. Comparative analysis of 12 different kits for bisulfite conversion of circulating cell-free DNA. Epigenetics. 2017;12:626–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen SK, Musher BL, LaPointe LC, Tuck MK, Symonds EL, Loayza N, Young GP. Detection of recurrent colorectal cancer with high specificity using a reporting threshold for circulating tumor DNA methylated in BCAT1 and IKZF1. Cancer. 2022;128:1921–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen SK, Symonds EL, Baker RT, Murray DH, McEvoy A, Van Doorn SC, Mundt MW, Cole SR, Gopalsamy G, Mangira D, et al. Evaluation of an assay for methylated BCAT1 and IKZF1 in plasma for detection of colorectal neoplasia. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erger F, Norling D, Borchert D, Leenen E, Habbig S, Wiesener MS, Bartram MP, Wenzel A, Becker C, Toliat MR, et al. cfNOMe—A single assay for comprehensive epigenetic analyses of cell-free DNA. Genome Med. 2020;12:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Xu Y, Zhong W, Zhao J, Chen M, Zhang L, Li L, Wang M. Total DNA input is a crucial determinant of the sensitivity of plasma cell-free DNA EGFR mutation detection using droplet digital PCR. Oncotarget. 2017;8:5861–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andresen K, Boberg KM, Vedeld HM, Honne H, Hektoen M, Wadsworth CA, Clausen OP, Karlsen TH, Foss A, Mathisen O, et al. Novel target genes and a valid biomarker panel identified for cholangiocarcinoma. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1249–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vedeld HM, Grimsrud MM, Andresen K, Pharo HD, von Seth E, Karlsen TH, Honne H, Paulsen V, Farkkila MA, Bergquist A, et al. Early and accurate detection of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis by methylation markers in bile. Hepatology. 2022;75:59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Group d, Huggett JF. The digital MIQE guidelines update: minimum information for publication of quantitative digital PCR experiments for 2020. Clin Chem. 2020;66:1012–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/15349126.