Abstract

Importance:

Nomenclature in the field of neurodegenerative diseases presents a challenging problem. Inconsistent use of terms such as Alzheimer disease and dementia has compromised progress in clinical care, research, and development of therapeutics. Dementia-associated stigma further contributes to inconsistent and imprecise language. The result is a lack of clarity that produces confusion with patients and the general public and presents communication challenges among researchers. Therefore, the Advisory Council on Research, Care, and Services of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer's Disease authorized a committee to make recommendations for improvement.

Objective:

To establish a systematic neurodegenerative disease framework for information collection and communication to standardize language usage for research, clinical, and public health purposes.

Evidence review:

The Dementia Nomenclature Initiative organized into 3 major stakeholder working groups: clinicians, researchers, and the public (including individuals living with dementia and family caregivers). To inform the work, the initiative completed a narrative literature review of dementia nomenclature evolution over the last century across the PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Scopus databases (January 1, 2000, through July 31, 2020). Initiative working groups used the results as a foundation for understanding current challenges with dementia nomenclature and implications for research, clinical practice, and public understanding. The initiative obtained additional input via focus groups with individuals living with dementia and caregivers, with separate groups for race and ethnicity (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and White) as an initial assessment of the meaning of dementia-related terms to these groups.

Findings:

From working group deliberations, the literature review, and focus group input, the initiative developed a framework clearly separating the clinical syndromic presentation experienced by affected individuals from possible underlying pathophysiologies. In the framework, domains of clinical impairment, such as cognitive, behavioral, motor, and other neurologic features, are graded by level of impairment between none and severe. Next, biomarker information describes underlying disease processes, explains the syndrome, and identifies possible disease labels: Alzheimer disease, frontotemporal degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, or vascular cognitive impairment dementia.

Conclusions and relevance:

The Dementia Nomenclature Initiative established a framework to guide communication about cognitive impairment among older adults. Wider testing and refinement of the framework will subsequently improve the information used in communicating about cognitive impairment and the way in which the information is used in clinical, research, and public settings.

Introduction

Nomenclature issues in disease have been a vexing problem for centuries. Nomenclature refers to principles of naming conditions or disease processes, for instance, deriving terms from clinical symptoms or etiology.1 The terminology to describe medical and neurological disorders has fluctuated tremendously over the years, and the current terms used to describe neurodegenerative diseases have resulted in inconsistent and, at times, chaotic, counterproductive use of terms. This problem hinders research, clinical encounters, and care for patients and limits public understanding of cognitive disorders, potentially delaying early detection.

In 2011, President Barack Obama signed into law the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA), which charged the US Department of Health and Human Services to form an advisory committee to develop the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease.2 The Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services was charged with making recommendations to Congress on an annual basis for suggested alterations of the biomedical and care research for Alzheimer disease (AD) and Alzheimer disease–related dementias (ADRD). Recommendations emerged from the 2019 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Alzheimer’s Disease–Related Dementia Summit, calling for consensus and harmonization for AD and ADRD nomenclature that attends to the needs of the range of stakeholders, including researchers, individuals living with dementia and their families, and health care practitioners.3 In response to the inconsistency and lack of clarity of existing dementia terminology, the advisory council recommended formation of a committee to make recommendations on the issue of nomenclature for AD and ADRD.3

In 2018, at the recommendation of the Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services, a nomenclature committee was formed to propose recommendations to address nomenclature across the neurodegenerative diseases under the scope of the NAPA. These diseases encompass AD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), frontotemporal degeneration (FTD), and vascular cognitive impairment dementia (VCID). Since the law encompassed only these 4 diseases, they were the charge of the nomenclature initiative. The advisory council subsequently charged the nomenclature committee to implement formal process recommendations presented at the 2019 NIH ADRD summit.

The nomenclature committee included researchers, clinicians, dementia advocates, and a person living with dementia. The committee began by exploring the nature of the problem of clinical and research nomenclature and challenges to communication with the patients and the public, including among racially and ethnically diverse populations in the US. Here, we describe the resulting communications framework and offer hypothetical case examples of its use. We conclude with possibilities for refining the framework and improving nomenclature for the field and for the public. (For a summary of deliverables from this work, see the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative.4)

Nature of the Problem

An assessment of the current nomenclature revealed very inconsistent use of terms employed to describe the diseases outlined earlier (AD, DLB, FTD, and VCID). The frequent interchange of the terms dementia and AD incorrectly presumes that these terms are the same. For example, the term AD is frequently used to characterize all of these degenerative cognitive disorders. In fact, in the NAPA law, the term AD was chosen to represent both Alzheimer disease and related disorders or, in some instances, the dementia phase of an underlying degenerative disease. Alzheimer disease–related disorders was subsequently coined to include DLB, FTD, and VCID, as if are all directly related to AD.5,6 Although the underlying pathologies of these disorders can clearly coexist, they remain distinct disease processes, and it is not clear why these disorders are considered AD related. The ADRD acronym is now also often misused to be inclusive of AD.

A major issue is the interchangeability of clinical features and the underlying pathophysiology of these disorders in scientific and common parlance. It is not uncommon for individuals in the field to make statements like “this patient progressed from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer disease,” as if to say these were different stages of the same disorder and all MCI is due to AD. In reality, AD, DLB, FTD, and VCID neuropathophysiologies can cause a clinical MCI syndrome on the road to dementia. This misuse of the term MCI reflects the lack of recognition of the syndromic clinical features apart from the biological characteristics of the underlying disorders.7

Consequently, the nomenclature committee (now the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative Steering Committee) formed 3 subcommittees, including research investigators, clinicians, and public stakeholders, to address the issue of terminology across the spectrum. The steering committee included an individual living with dementia. These 3 groups addressed the use of nomenclature, appropriate terminology, and implications of possible changes for their own area. The history and current state of nomenclature was reviewed, and focus groups were engaged to make recommendations regarding terminology use from additional sectors not represented in the subcommittees.

Evidence Review

To understand the relevant history, members of the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative conducted a narrative literature review of the PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Scopus databases (January 1, 2000, to July 31, 2020), focusing on US-based work and non-US dementia nomenclature work in Canada, Australia, Japan, and English-speaking countries in the European Union. The results were summarized thematically and were an initial point of reference for subsequent initiative discussions.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity and Inclusion: Focus Groups

The underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority communities in dementia research in the US is a problem with long historical roots. Failure to appreciate the limits of scientific knowledge based on studies in which the majority of participants are White and upper-middle-class is now accepted as a major barrier to clinical care and research outreach with racial and ethnic minority populations, continuing the cycle of underrepresentation.8–10

Larger systemic solutions are needed. As a first step. the steering committee initiated an investigation of the meaning of dementia-related terms to different racial and ethnic groups. To this end, the initiative obtained input through 6 focus groups separated by race and ethnicity as follows: American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 1), Asian or Pacific Islander (n = 1), Black or African American (n = 1), Hispanic or Latino (n = 2), and 1 White (n = 1). The groups had a total of 41 participants, including 5 (12.2%) living with dementia. These focus groups provided a start toward obtaining direct input from different racial and ethnic groups in the US, as a first step toward examining the feasibility of the framework approach for a range of patient and caregiver communities.

The qualitative data support prior research indicating that term preferences and usage differ across racial and ethnic groups.11 Assumptions based on research in which the majority of individuals are White may not provide appropriate insight into racial and ethnic minority populations in the US.12,13 In the search for terminology to aid communication with all individuals living with dementia and their families and for broad communication with the public, careful testing with attention to race and ethnicity and culture is necessary.8 A more comprehensive data collection is planned for the next phase of this work, including more robust qualitative data, to ensure that input is obtained from multiple types of patients and caregivers.

Toward a Communications Framework

Syndrome and Pathophysiology

A key priority identified in the initiative was to improve terminology and communication. Toward that end, the steering committee addressed the distinction between the clinical cognitive and behavioral syndromes commonly encountered in research and practice and the underlying pathophysiology, such as the presence of amyloid, tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43 (TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa), vascular disease, and cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. The inconsistent interchanging of syndromic terminology for pathophysiology was sufficiently common that researchers and clinicians within the field have unwittingly added to the confusion. As has been reviewed previously, the historical use of many of these terms has complicated the picture as well.6

AD Terminology

The definition of AD has evolved in recent decades away from a clinical-pathological construct, as outlined by McKhann et al14 in 1984, to a combination of clinical features and the presence of amyloid and tau neuropathology. Probable AD was used for the clinical diagnosis, as a definite AD diagnosis could not be established until the patient died and an autopsy confirmed the presence of plaques and tangles. This characterization of AD persisted in use for several decades until committees convened in 2011 to reassess the criteria for AD, incorporating existing knowledge of biomarkers.15–17 This group characterized the clinical spectrum as preclinical AD, MCI due to AD, and dementia due to AD and combined the clinical syndromes with biomarkers for amyloid and neurodegeneration that were present at the time. Using this strategy, the clinical syndromes could be characterized with the use of biomarkers according to their likelihood of being caused by underlying AD pathologies rendering a description as “unlikely,” “likely,” and “definite” as a means of probabilistic statement association.

In 2018, another committee convened by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association updated this approach with the evolution of additional biomarker research.18 These experts concluded that AD should be defined only on its biological basis (ie, the presence of amyloid and tau), irrespective of the clinical presentation. The clinical syndromes could be used to stage the disease but not to define it. This research proposal, which is currently being validated by the field, offers a unique perspective on AD terminology and is currently being updated. There is presently a degree of uncertainty in the field about what individuals mean when they use the term AD. Probing questions must establish clarity on whether the use of this term refers to a clinical syndrome, a clinical-pathologic complex, or a biological entity. Although it is presumably advancing the field, this approach has introduced another layer of terminological complexity, particularly since biomarkers are mostly available to date for AD, and we know that many other pathologies, alone and in combination, cause cognitive decline and dementia.19,20

In Europe, the International Working Group also proposed criteria for AD that included biomarkers.21 However, this group reserved the AD label for symptomatic stages of the disease and labeled preclinical disease as “AD at risk.” Consequently, there is no international consensus on the definition of AD.

Nomenclature Communications Framework

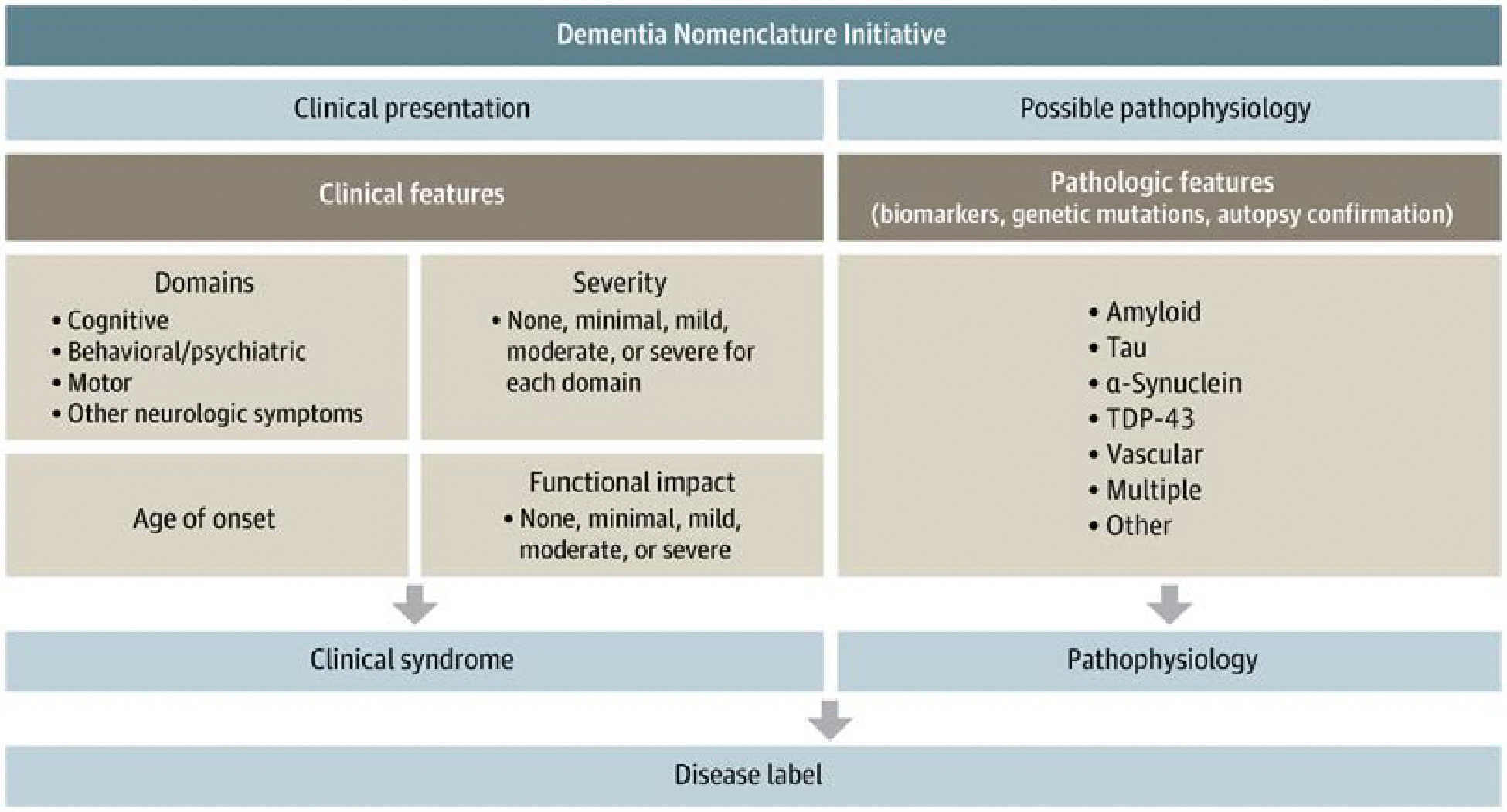

With this prior work as a backdrop, the nomenclature committee developed a communications framework intended to support patient, family, and public understanding about cognitive impairment symptoms, causes of cognitive impairment, and levels of impairment (Figure and eFigure in the Supplement). The framework also strives to provide scaffolding for communication among and between the clinical and research communities. To meet all of these communication needs, the framework divides a disease into its syndromic presentation (distinctive clinical neurologic features and severity of symptoms in each) and its pathophysiologic evidence. It flexibly incorporates what is known for a specific patient or group of patients with cognitive impairment across the continuum from low to high information. There is also an overall functional severity rating for the impact of the neurologic symptoms on activities of daily living and independence.

Figure.

Dementia Nomenclature Initiative

TDP-43 indicates TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa.

The clinical presentation deconstructs the syndromes into 4 component pieces. The components are cognitive, behavioral/psychiatric, motor, or other neurologic symptoms. Together, these capture most of the syndromic features with which a patient might present. For example, in the component of cognitive function, each individual could be evaluated on memory, language, visuospatial, executive, and attention domains. The profiles generated could be suggestive but not definitive of underlying pathologic states. In addition, behavioral/psychiatric features that encompass social skills, mood, apathy, hallucinations, and delusions can be important components of the clinical presentation. Similarly, some neurodegenerative diseases have motor features such as speed of function, tremor, stiffness, or gait changes. These components can be quite suggestive of underlying diseases. Finally, many clinical presentations are accompanied by autonomic features such as constipation, orthostatic dizziness, and sleep disorders. Although they are not exhaustive, these components capture the essence of clinical presentations of the relevant diseases causing cognitive impairments.

The severity of involvement of each symptomatic component (ie, cognitive, behavioral/psychiatric, motor, or other neurologic symptoms) can then be graded qualitatively on the degree of impairment (none, minimal, mild, moderate, or severe) for each domain. The separation of domains when assessing severity is important, especially in the early stages of a neurodegenerative illness when some domains are moderately impaired while others remain mildly impaired or unimpaired, sometimes for years after symptom onset.

Clinical symptom severity is often, but not always, reflected in daily functional activities. Since an essential feature of the overall presentation pertains to how symptoms affect the patient’s ability to function in their particular environment, the overall functional impact of disease is graded as follows: none, minimal, mild, moderate, or severe. This characterization allows clinicians to discuss with patients and families the patient’s degree of impairment within the overall environment. Ultimately, the clinical presentation, deconstructed into its essential features, describes the status of the patient, and these features constitute the clinical syndrome. The clinical syndrome is critical in management recommendations because not all affected individuals have the same limitations, especially in earlier stages of illness.

The final component of the communications framework is the presumed pathophysiologic underpinning of the clinical syndrome. This may involve the use of biomarkers, if available, for the underlying pathophysiologic components, such as amyloid, tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43, and vascular features. However, it is apparent that, often, these pathophysiologic components do not exist in isolation, and it is much more common for them to appear in combination. As such, although the clinical syndromes can be variable, the underlying pathophysiology can be similarly heterogeneous. The pathophysiology then can be suggested by using biomarkers and/or detected genetic mutations or confirmed at the time of brain autopsy. Other pathophysiologies can be added as the field progresses.

This communications framework is applicable for the neurodegenerative disorders covered by the National Plan to Address Alzheimer Disease: AD, DLB, FTD, and VCID. Once the clinical syndrome and suspected pathophysiology are elucidated for a particular patient, various disease labels can be offered. For example, one could now more clearly relay that this clinical syndrome, plus the combination of biomarkers, most likely suggests underlying AD. Alternatively, a different syndrome and a combination of biomarkers might suggest Lewy body disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, or vascular etiologies. Again, the most common presentation involves multiple pathologic components, and these disease labels, while useful, must be regarded with some caution. Clinical syndrome information and/or pathophysiologic information can be used by the clinician in the course of communicating with the patient and others about the diagnosis.

The message to affected individuals and their families should be that knowing the disease can, in some cases, help to tailor pharmacologic intervention, but in most cases, this knowledge does not directly lead to disease-modifying treatment or cure. Although the legislation only referred to the 4 neurodegenerative diseases described here, the framework may well apply to other entities such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson disease, or Huntington disease. Finally, perhaps as important as pharmacologic intervention are psychosocial interventions based on individual differences in symptom expression and their impact on daily living. Thus, an individual with a primary memory disorder will require different strategies from someone with social-interpersonal changes to support continued functioning in the community.

Hypothetical Clinical Examples of Framework Application

Case Patient 1

A 68-year-old woman who presents with memory and executive function issues, mild apathy, and no notable motor or autonomic features could be considered. The degree of memory and attentional impairment is felt to be mild, as is the apathy, confirmed by objective testing. From an overall functional perspective, the patient is determined to have minimal impairment, with respect to daily activities. She is still working as a librarian. At this point, using current terminology, the patient might be characterized as having MCI, with memory and mild behavioral features. If biomarker investigations indicate that the patient has evidence of amyloid and tau, the clinician might conclude that the patient presents with MCI likely due to underlying AD. This characterization of the clinical syndrome and the putative underlying pathophysiology could be explained to the patient and family, and speculation regarding progression could be made. The communication framework gives a cross-sectional characterization of the patient, and other features should be included in the discussion of the possible rate of progression.

Case Patient 2

A 70-year-old patient may present with difficulties in executive function and visuospatial skills. This individual may also have some visual hallucinations and delusional thinking at times, which never occurred in the past. On examination, they are shown to have some slowness and perhaps increased tone on motor examination. The history indicates that the patient has experienced features of a rapid-eye-movement behavior disorder in the past. The executive and attentional features are assessed as mild, whereas the visual hallucinations are of moderate severity. The overall impact of this collection of findings on the patient’s overall daily function is mild but definite, observable in the need for assistance in some complex daily tasks. Based on this syndromic characterization, the patient may be experiencing features of a mild dementia stage of impairment; if biomarkers are available and suggest features of an underlying α-synucleinopathy, this could be the earliest presentation of a mild dementia due to Lewy body disease. Again, the clinician may need to caution the patient and family that while α-synuclein may actually be the predominant pathologic feature, it may not be the only pathophysiology present in this particular instance, and there could be accompanying amyloid and tau in the total picture.

Case Patient 3

A 50-year-old individual presents to the clinician with features of alterations in executive function and attention. The patient’s social skills are dramatically altered from their usual way of behaving, and they are exhibiting inappropriate behavior, a change in personality, and a lack of empathy. There may not be any prominent motor features present, and other neurologic symptoms are absent. The clinical severity of the cognitive impairments as objectively tested are in the mild domain, but the behavioral psychiatric features regarding social skills seem moderately compromised. As such, the patient’s overall daily activities are mildly to moderately impaired. The patient struggles to function in society like they did formerly, despite normal memory and language abilities. Structural and functional neuroimaging studies suggest involvement of the anterior portions of the frontal and temporal lobes. The clinical syndrome is that of behavioral variant dementia and, when coupled with biomarkers for putative underlying pathology like tau or TDP-43, it is likely that this is a behavioral variant of one of the forms of FTD. Again, prognosis could be discussed based on the clinical presentation and the history.

Stigma

The public stakeholder subcommittee explored the issue of stigma and terminology and recommends avoidance of the term demented as an adjective to describe individuals living with dementia, as it is particularly stigmatizing. The committee also noted individuals’ sentiments that statements like “the person is demented” could have pejorative implications. Across all subcommittees, consensus emerged that the term dementia can be stigmatizing to certain individuals and is challenging to use in a cross-cultural framework. Certainly, racial and ethnic minority and underrepresented focus group participants indicated that use of the term dementia can invoke stigma as well. One possibility posed by others is that while the term can be problematic, the stigma may very well pertain to the clinical presentation itself and/or lack of treatments for many of these disorders. Ultimately, the committee decided that the term demented should be retired, as it is especially stigmatizing. Although no recommendation has been made for alternative terminologies to “dementia,” utilization of the framework provides an alternative communications strategy.

Summary

There are many barriers to the use and understanding of neurodegenerative disease terms for research, clinical, regulatory, and public utilization purposes. The committee considered many of these issues and developed a communications framework to help all stakeholders develop a consistent use of these terms.

In response to recommendations presented at the 2019 NIH ADRD summit, the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative formed and through a consensus process created a communications framework to drive more consistent use of terminology for neurodegenerative diseases. The framework emphasizes the separation of clinical syndromes from the underlying pathophysiology, informed by biomarkers. The framework is designed to overcome current dementia nomenclature challenges by producing consistency in the use of terms for neurodegenerative diseases.

Combining available information from clinical presentations and from potential pathophysiologic causes or contributors is a strategy used by many clinicians working with individuals with cognitive impairment. Given that this approach is neither consistent across clinicians nor universally applied, attention to improving nomenclature through a feasible process is still needed. The framework presented here provides a means of expanding and systematizing that process. We maintain reference to existing diagnostic terminology at this stage of the work, insofar as that can support wide understanding of the strategy in advance of any subsequent terminology revision.

While ultimately establishing a consistent and widely accepted set of terms is desirable, initiative members are aware that establishing such a “new” nomenclature would require substantial commitment from clinical, research, and funding community organizations, an undertaking beyond the scope of this initial phase of the work. To be successful, global harmonization would be required as well, adding further challenges. Initiative members determined that a feasible but impactful outcome of this initial examination of nomenclature was to establish a method for using available clinical and pathophysiologic information to improve consistency of communication with patients in a clinical setting, to improve consistency of use of terminology among researchers, and to improve general public communication.

The next phase of this work is intended to establish the feasibility of wide adoption of this framework approach across clinical settings and types of clinicians involved in diagnosing individuals with cognitive impairment. Among the specific points to be addressed are how best to operationalize severity grading, with reference to the substantial literature on clinical and functional measurement, and what type of communication aids and education are needed to make this approach effective. To ensure widespread usefulness, the next phase of this work is intended to expand data collection to encompass multiple types of patients and caregivers, capturing similarities and differences across race and ethnicity, living situation, and socioeconomic status.

This initial work yielded specific recommendations for next steps, including testing the framework in practice and refining it accordingly. Once finalized, strategies for wide dissemination of the framework are needed as one step toward addressing the nomenclature problem. With additional input from clinicians, researchers, patients, and the public, consistent terminology could be developed, potentially to include an umbrella term about the range of cognitive disorders or pathophysiologies, to advance public understanding.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by AARP, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, the Lewy Body Dementia Association, the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, the Bluefield Project, and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Petersen reported receiving consulting fees from Roche Inc, Genentech In, Eli Lilly Inc, Eisai Inc, and Nestlé Inc and research support from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the GHR Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Association outside the submitted work. Dr Petersen also reported serving on a data and safety monitoring board for Genentech Inc outside the submitted work. Dr Weintraub reported receiving research support from the NIA and NINDS outside the submitted work. Dr Sabbagh reported having ownership interest (stock or stock options) in NeuroTau, uMethod Health, Athira, Seq BioMarque, NeuroReserve, Lighthouse Pharmaceuticals, Alzheon, and Reservoir Neuroscience outside the submitted work. Dr Sabbagh also reported serving on the board of directors of EIP Pharma and receiving consulting fees from Roche-Genentech, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Synaptogenix, NeuroTherapia, T3D Therapeutics, Signant Health, Novo Nordisk, Corium, and Prothena outside the submitted work. Dr Karlawish reported serving as a site investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Biogen Inc and Eli Lilly outside the submitted work. Dr Adler reported receiving consulting fees from Avion, Cionic, CND Life Sciences, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, PreCon Health, and XWPharma and research support from the National Institutes of Health, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Arizona Biomedical Research Commission, and Banner Health outside the submitted work. Dr Frank reported being employed by the RAND Corporation while they completed work related to this initiative under contract to the Lewy Body Dementia Association. Dr Huling Hummel reported serving on the National Advisory Council on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Clinical Trials Consortium and as a board member of the Dementia Action Alliance outside the submitted work. Ms Taylor reported being employed by the Lewy Body Dementia Association outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Group Information: Members of the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative are as follows: Paul Appelbaum, MD; Brian Appleby, MD; Lisa Barnes, PhD; Michael Belleville; Maria Carrillo, PhD; Kathy Chan; Cyndy Cordell; Rod Corriveau, PhD; Sharon Denny, MA; Brad Dickerson, MD; Rachel Dolhun, MD; Elena Fazio, PhD; Elizabeth Gould, MSW; Judit Illes; David Irwin, MD; Matthew Janicki, PhD; Eran Klein, MD, PhD; David Knopman, MD; Sarah Lenz Lock, JD; Paul Lester; Jim Leverenz, MD; Oscar Lopez, MD; Lisa McGuire, PhD; Darby Morhardt, PhD, LCSW; Darina Petrovsky, PhD, RN; Maria Reyes, MD; Natalia Rost, MD; Julie Schneider, MD, MS; Matt Sharp; Luke Stoekel, PhD; Eric Tangalos, MD; Daniel Weintraub, MD; and Mary Widmeyer, MD.

Additional Contributions: We gratefully acknowledge the members of the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative. We also thank Alina Palimaru, PhD, MPP, and Laura Whitaker, MPH, of the RAND Corporation and John Beilenson, MA, of SCP Communications, whose contributions were completed under contract to the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

The version of record for this manuscript is available from JAMA Network, JAMA Neurology at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2810313

Data Sharing Statement:

See Supplement 2.

References

- 1.Kennedy J, Kossmann CE. Nomenclatures in medicine. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1973;61(2):238–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Alzheimer’s Project Act, S 3036, 111th Cong (2010). Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/3036

- 3.Corriveau RA, Koroshetz WJ, Gladman JT, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias Summit 2016: national research priorities. Neurology. 2017; 89(23):2381–2391. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Dementia Nomenclature Initiative. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://aspe.hhs.gov/collaborations-committees-advisory-groups/napa/napa-additional-information/dementia-nomenclature-initiative

- 5.Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr. A brief history of “Alzheimer disease”: multiple meanings separated by a common name. Neurology. 2019;92 (22):1053–1059. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen RC. How early can we diagnose Alzheimer disease (and is it sufficient)? The 2017 Wartenberg lecture. Neurology. 2018;91(9):395–402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, et al. Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González HM, Tarraf W, Gouskova N, et al. Neurocognitive function among middle-aged and older Hispanic/Latinos: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;30(1):68–77. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Indorewalla KK, O’Connor MK, Budson AE, Guess DiTerlizzi C, Jackson J. Modifiable barriers for recruitment and retention of older adult participants from underrepresented minorities in Alzheimer’s disease research. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;80(3):927–940. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki R, Goebert D, Ahmed I, Lu B. Folk and biological perceptions of dementia among Asian ethnic minorities in Hawaii. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(6):589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mindt MR, Okonkwo O, Weiner MW, et al. Improving generalizability and study design of Alzheimer’s disease cohort studies in the United States by including under-represented populations. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(4):1549–1557. doi: 10.1002/alz.12823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raman R, Aisen PS, Carillo MC, et al. Tackling a major deficiency of diversity in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic trials: an CTAD Task Force report. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(3):388–392. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2022.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3): 270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3): 263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3): 280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack CR Jr, Therneau TM, Weigand SD, et al. Prevalence of biologically vs clinically defined Alzheimer spectrum entities using the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Research Framework. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10): 1174–1183. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider JA. Neuropathology of dementia disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2022;28(3): 834–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois B, Villain N, Frisoni GB, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(6):484–496. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00066-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

See Supplement 2.