Abstract

The possibility that a mucolytic drug, i.e., acetylcysteine, given orally may enhance the gut mucosal or systemic immune response to an oral B-subunit–whole-cell (B-WC) cholera vaccine was evaluated for 40 adult Swedish volunteers, and the kinetics of the immune responses were monitored for responding volunteers. Two doses of vaccine induced similar frequencies of immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG antitoxin responses (80 to 90%) and vibriocidal titer increases (60 to 65%) in serum irrespective of whether the vaccine was given alone or together with 2 g of acetylcysteine. In feces the frequencies of IgA antitoxin (67%) and antibacterial (33 to 40%) antibody responses were also comparable in the two immunization groups. Six months after vaccination, IgA and IgG antitoxin as well as vibriocidal antibody titer increases in serum could still be detected in approximately 80% of initially responding vaccinees. Significantly elevated fecal antitoxin and antibacterial IgA antibody levels were found in, respectively, 50 and 43% of those volunteers who initially had responded to the vaccine. Determination of IgA antibodies in feces does not seem to offer any advantages compared to determination in serum for assessment of immune responses after immunization with inactivated cholera vaccine.

Stimulation of the gut mucosal immune system is most efficiently achieved by antigens applied directly to the luminal surface of the small intestine (6). Studies with animals have shown that a number of different compounds exert adjuvant effects on the intestinal immune response when given orally together with the antigen (8, 12). The most potent mucosal adjuvant so far identified is cholera toxin, but its high toxicity prevents its use in humans (7, 23). Several compounds have been evaluated in humans with regard to possible adjuvant effects when given together with various parenteral vaccines (11), but in the case of oral vaccines the experience with adjuvants in humans is still limited. Recently, a Lactobacillus strain was shown to enhance the immune responses to a reassortant live oral rotavirus vaccine in young children (14). The mucosal adjuvant effect was explained as facilitation of antigen transport to underlying lymphoid cells in the intestine.

Mucolytic substances have so far not been evaluated with regard to their possible adjuvant effects in mucosal immunizations. The proposed mode of action for such agents would be to enhance the antigen uptake in the small intestine by affecting the mucus layer. Acetylcysteine is a mucolytic agent that has been extensively used in humans for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3). When administered topically, it exerts rapid mucolytic activity by splitting the disulfide bonds in mucus molecules (9, 29). Cystic fibrosis patients with “meconium ileus equivalent” have been treated with daily doses up to 18 g, and the toxicity has been low (9).

The aim of the present study was to examine whether acetylcysteine had any adjuvant effect on the gut mucosal and systemic immune responses to an oral cholera vaccine, as well as to evaluate whether determination of specific IgA antibodies in feces could be a reliable method for assessing and monitoring the kinetics of the intestinal immune responses in humans after immunization. The cholera vaccine, consisting of a combination of the purified B subunit of cholera toxin (CTB) and heat- and formalin-killed O1 whole cells (B-WC), has in large field trials been shown to be completely safe and to confer protection against cholera for at least 3 years (5, 28). The antitoxin and antibacterial antibody responses in feces as well as in sera of Swedish volunteers given two doses of the oral B-WC vaccine together with acetylcysteine were compared with the responses found in volunteers receiving the vaccine alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant B-WC cholera vaccine.

The oral recombinant B-WC cholera vaccine was produced by the Swedish National Bacteriological Laboratory (Stockholm, Sweden) as previously described (17). Each dose of vaccine contained 1 mg of B subunit purified from the fermentation medium of a Vibrio cholerae O1 strain from which cholera toxin had been deleted and which harbored a recombinant plasmid that provides high-level production of CTB (26). The WC component consisted of 1011 killed O1 vibrios representing three different cholera strains belonging to Inaba and Ogawa serotypes and to classical and El Tor biotypes (13, 17).

Assessment of B-WC activity after exposure to acetylcysteine.

Initial experiments were undertaken to assess the antigenic contents of the antitoxin and antibacterial components of the B-WC vaccine before and after exposure to different concentrations of acetylcysteine. One vaccine dose (3 ml) was mixed with 100 ml of a 4% sodium bicarbonate–1.5% citric acid buffer solution in order to protect the B-subunit component from stomach acidity (4). After 10-ml aliquots of the vaccine-buffer solution were dispensed into flasks, a 200 mg ml−1 acetylcysteine solution (Acetylcystein Tika; Tika Läkemedel AB, Lund, Sweden) was added at final concentrations of 1, 2, and 5%. The vaccine-buffer solution alone was used as a control. The B-subunit activity in each aliquot was determined by a GM1–enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (30), and the WC component activity was determined by an inhibition ELISA method (21), in which V. cholerae O1 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (3 μg ml−1) was used as the solid-phase antigen and an immunoglobulin M (IgM) mouse monoclonal antibody against V. cholerae O1 LPS (8:4) (0.25 μg ml−1) was used for inhibition.

These analyses showed that 80 to 90% of the B-subunit activity was retained after incubation with 1 and 2% acetylcysteine, whereas the activity was reduced to 70% when the vaccine-buffer solution was subjected to 5% acetylcysteine. The WC activity varied between 88 and 95% after exposure to the three different concentrations of acetylcysteine. Based on these results, the oral B-WC vaccine was mixed with a 2% acetylcysteine solution in the subsequent study.

Study design.

Forty healthy adult Swedish persons (26 females and 14 males), aged 23 to 53 years, who had not been vaccinated against cholera previously, volunteered to participate in the study, which was approved by the Research Ethical Committee at the Medical Faculty, Göteborg University. Each volunteer received two oral doses of the recombinant B-WC cholera vaccine, with an interval of 2 weeks. The vaccine was administered in 100 ml of a 4% sodium bicarbonate–1.5% citric acid buffer solution (4). The buffer ingredients were delivered as two effervescent tablets, each consisting of 2,000 mg of sodium bicarbonate, 750 mg of citric acid, and 1,025 mg of lactose (ACO; ACO AB, Stockholm, Sweden) (18). Half of the volunteers were given the B-WC vaccine in buffer alone, and half were given the vaccine in buffer with 2 g of acetylcysteine (Tika Läkemedel AB). The trial was performed in a randomized open manner, since the taste of the acetylcysteine could not be concealed from the volunteers.

Serum and fecal specimens were collected immediately before the first immunization (day 0) and then 9 days after the second vaccine dose. In some instances, serum and fecal specimens were also obtained 180 days (range, 150 to 210 days) after the first immunization (Table 1). Sera were obtained by venous puncture and stored in aliquots at −20°C. Fecal samples were collected and frozen at −70°C within 2 to 3 h after collection. Fecal extracts were prepared by mixing 6 g of homogenized feces with 24 ml of a buffer solution containing enzyme inhibitors as described elsewhere (2, 10). The fecal extracts were stored in aliquots at −70°C. All analyses were performed within 2 months after collection.

TABLE 1.

Timetable for immunizations and sampling of specimens

| Day | No. of volunteers | Immunization | Samples collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 40 | Dose 1a | Serum, feces |

| 14 | 40 | Dose 2a | |

| 23 | 40 | Serum, feces | |

| 180 | 18 | Serum, feces |

Half of the volunteers were given the B-WC vaccine together with 2 g of acetylcysteine, and the other half received the vaccine alone.

Antibody determinations.

Serum antitoxin antibody responses of the IgA and IgG classes were determined by the GM1-ELISA method as previously described (31). Levels of antibacterial antibodies in serum were determined by a microtiter vibriocidal assay (24). Threefold (GM1-ELISA) or twofold (vibriocidal test) serial dilutions of pre- and postvaccination specimens were tested in duplicate. The antibody titer ascribed to each sample was the mean from duplicate determinations. A twofold or greater (antitoxin) or a fourfold or greater (vibriocidal) increase in endpoint titer in postvaccination specimens compared to prevaccination specimens was used to signify seroconversion at a P value of <0.05 (15, 18). Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by using the t distribution in a two-tailed fashion.

Levels of total IgA in fecal specimens were determined by a modified microplate ELISA method (32). Specimens with very low IgA concentrations, ≤20 μg ml−1, or with a greater-than-10-fold difference in total IgA content between pre- and postvaccination samples were excluded from further analyses, since our previous studies have shown that antibody titrations of such specimens give unreliable results (2).

IgA antibody responses to cholera toxin in fecal extracts were studied by the GM1-ELISA (31), and antibacterial antibodies were studied by an ELISA in which the WC component of the B-WC vaccine (2.5 × 107 bacteria ml−1) or V. cholerae O1 LPS (purified from a classical Inaba strain, 569B; 3 μg ml−1) was used as the solid-phase antigen. Threefold (antitoxin) or twofold (antibacterial) serial dilutions of pre- and postvaccination specimens were tested side by side. The specific IgA antitoxin and antibacterial activities in fecal specimens were determined by dividing the IgA ELISA antibody titer by the total IgA concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) of the sample. Based on previous calculations, a greater-than-twofold increase in IgA antibody titer/total IgA observed in postimmunization specimens compared to preimmunization specimens was chosen to signify seroconversion (1).

RESULTS

Antibody responses in serum.

Prior to immunization, the IgA and IgG antitoxin and vibriocidal antibody titers in serum were comparable in volunteers receiving B-WC vaccine alone and those receiving it together with acetylcysteine. Two doses of vaccine induced similar frequencies of significant IgA and IgG antitoxin titer increases in the two immunization groups, and the magnitudes of the responses were also comparable (Table 2). Thirteen (65%) of the volunteers receiving the acetylcysteine-vaccine mixture responded with significant increases in vibriocidal titer; the corresponding figure for persons receiving vaccine alone was 60% (Table 2). The magnitude of the vibriocidal response was higher in volunteers given vaccine alone than in those receiving the acetylcysteine-vaccine mixture, but the difference was not statistically significant (Student’s t test, unpaired, two-tailed). In both groups the titer increases tended to be higher in volunteers with low preimmune levels of vibriocidal antibodies (<1:40) than in those with high prevaccination titers (≥1:40).

TABLE 2.

Antitoxin and vibriocidal antibody responses in sera of Swedish volunteers after two oral immunizations with cholera vaccine given alone or together with acetylcysteine

| Antibody | Response in group receiving:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine alone

|

Vaccine + acetylcysteine

|

|||

| Frequencya | Magnitudeb | Frequencya | Magnitudeb | |

| IgA antitoxin | 17/20 (85) | 22 | 16/20 (80) | 21 |

| IgG antitoxin | 16/20 (80) | 6.6 | 18/20 (90) | 5.6 |

| Vibriocidal | 12/20 (60) | 25 | 13/20 (65) | 9.8 |

| Preimmune titer, <1:40 | 9/13 (69) | 40 | 6/7 (86) | 18 |

| Preimmune titer, ≥1:40 | 3/7 (43) | 6.3 | 7/13 (54) | 5.9 |

Number of responders/number tested (percent).

Geometric mean titer increase for all responding volunteers in relation to prevaccination titers.

Antibody responses in feces.

Fecal extracts from five (25%) of the volunteers given B-WC vaccine together with acetylcysteine and from eight (40%) of those receiving vaccine alone contained ≤20 μg of total IgA per ml or showed a greater-than-10-fold difference in total IgA between pre- and postvaccination specimens and were therefore excluded from the analyses.

Before vaccination the levels of antitoxin and antibacterial IgA antibodies in feces were comparable in the two immunization groups. Two doses of vaccine induced significant increases in CTB-specific IgA antibody titers/total IgA in 67% of the volunteers in each immunization group, and the magnitudes of the responses were also comparable (Table 3). Similarly, the frequencies and magnitudes of antibacterial IgA antibody responses did not differ between the groups. Those vaccinees who responded with increases in titers of IgA antibody to LPS also responded to whole bacteria in feces, and the magnitudes of the responses against the two types of bacterial antigens were very similar (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Fecal IgA antitoxin and antibacterial antibody responses in Swedish volunteers after two oral immunizations with cholera vaccine given alone or together with acetylcysteine

| IgA | Response in group receiving:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine alone

|

Vaccine + acetylcysteine

|

|||

| Frequencya | Magnitudeb | Frequencya | Magnitudeb | |

| Antitoxin | 8/12 (67) | 4.1 | 10/15 (67) | 4.9 |

| Anti-WC | 4/12 (33) | 3.5 | 6/15 (40) | 3.2 |

| Anti-LPS | 4/12 (33) | 3.2 | 6/15 (40) | 3.4 |

Number of responders/number tested (percent).

Geometric mean increase in specific IgA antibody titer/total IgA among responders in relation to prevaccination titer/total IgA.

The relation between IgA antibody responses in sera and feces from those 27 volunteers for whom both types of specimens were available (data from the two immunization groups were pooled) was also studied. Among the 20 volunteers responding with significant IgA antitoxin increases in serum, 13 developed significant IgA antitoxin responses in feces, and 9 of the 16 volunteers with vibriocidal antibody titer increases in serum also developed significant fecal antibacterial IgA responses.

Kinetics of immune responses.

Serum and fecal specimens were obtained approximately 180 days after the first immunization from most of those volunteers who had initially responded to B-WC vaccine in feces (data from the two immunization groups were pooled). In total, the kinetics of the antitoxin immune responses were monitored for 18 volunteers and the kinetics of the antibacterial responses were monitored for 7 individuals.

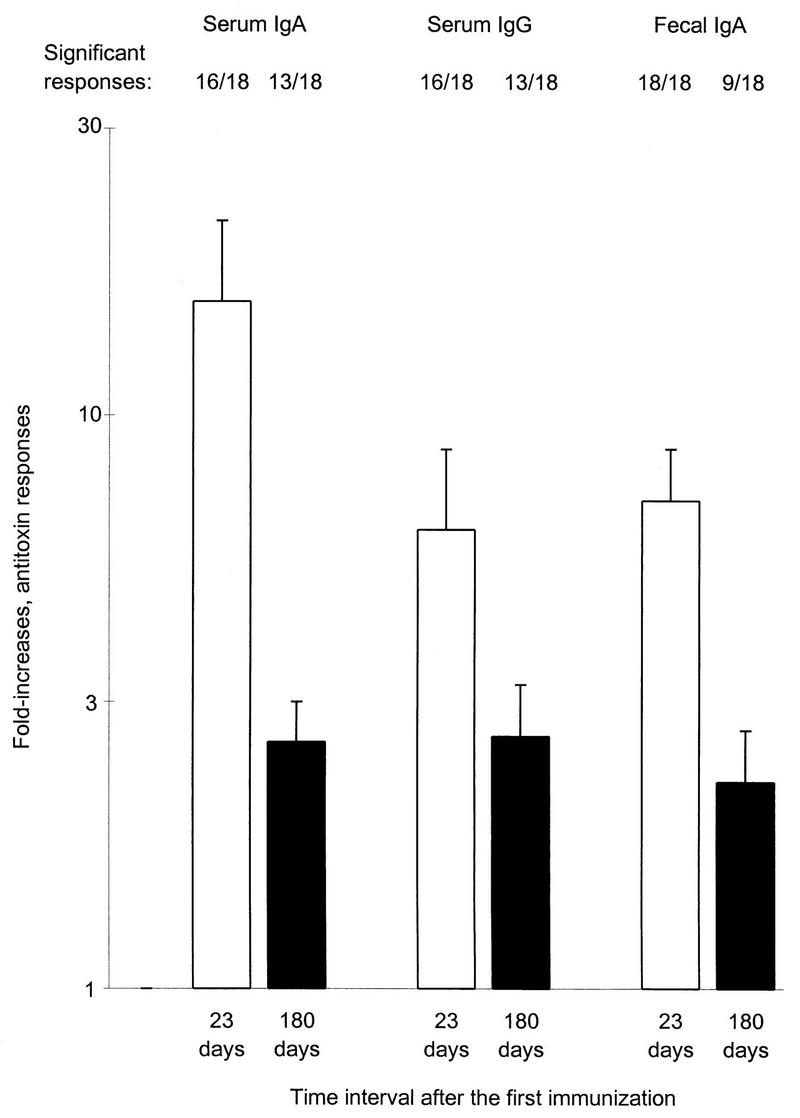

In serum, elevated IgA and/or IgG antitoxin levels in relation to preimmune titers could still be found 180 days after immunization in 13 of the 18 volunteers (Fig. 1). A substantial decline in the magnitude of the IgA antitoxin titer increases among responders, from 21-fold (95% CI, 11.5 to 40) to 3.5-fold (95% CI, 1.6 to 7.4), was noted at follow-up, whereas the magnitude of the IgG antitoxin titer increases among responders had decreased from 8.1- to 4.1-fold. Also in feces, significantly elevated CTB-specific IgA antibody levels could be demonstrated 180 days after vaccination in 9 (50%) of 18 volunteers (Fig. 1), although the magnitude of the titer increases among responders had decreased from 7.1- to 4.2-fold.

FIG. 1.

Geometric mean fold increases (plus standard errors of the mean) of IgA and IgG antitoxin titers in serum and of IgA antitoxin titers/total IgA in feces after two oral doses of B-WC cholera vaccine in 18 Swedish volunteers 23 days (□) and approximately 180 (150 to 210) days (▪) after the first immunization. The numbers of volunteers responding are indicated above the bars.

Vibriocidal antibody titer increases in serum were found in five of seven volunteers 9 days after the second immunization, and four of them still had significantly elevated vibriocidal antibody levels 180 days later. However, the magnitude of the vibriocidal responses among responders had decreased from 14-fold (95% CI, 7.4 to 26) to 5.6-fold (95% CI, 2.2 to 14). Significant increases in fecal IgA antibacterial antibody titers in relation to preimmune titers could still be demonstrated in three (43%) of seven volunteers at follow-up; the magnitude of the titer increases among responders was slightly decreased, from 3.8- to 2.9-fold.

The relation between IgA immune responses in serum and feces 180 days after vaccination was also studied. Among the 13 volunteers with IgA antitoxin increases in serum, 7 had significant IgA antitoxin responses in feces, and 3 of the 4 volunteers with vibriocidal antibody titer increases in serum also had significant fecal antibacterial IgA responses.

DISCUSSION

The present study does not support the hypothesis that acetylcysteine may promote the immunogenicity of the oral B-WC cholera vaccine in the intestines of Swedish volunteers, as both the frequencies and magnitudes of antitoxin and antibacterial antibody responses in feces and serum were comparable in volunteers receiving vaccine alone and in those receiving vaccine together with 2 g of acetylcysteine. A possible explanation for this inability of acetylcysteine to enhance the immune responses to the vaccine may be that the mucus layer does not prevent the uptake of the vaccine by the antigen-presenting cells. Alternatively, the concentration of the mucolytic agent reaching the small intestine could have been too low to exert any substantial topical action (25), even though the amount of acetylcysteine given was 10 times higher than the normal dose used in patients with chronic bronchitis.

The most reliable method for assessing intestinal immune responses in humans after oral immunization with enteric vaccines has been to determine specific IgA antibodies in intestinal lavage fluid (15). However, the lavage procedure is laborious and cannot be used for evaluations of immune responses in larger immunization groups, e.g., in children and under field conditions. Recently, intestinal antibacterial IgA antibody responses to an oral live auxotrophic Shigella flexneri vaccine, detected in feces, were described (22). Determination of antitoxin as well as antibacterial IgA antibody responses in stool specimens has also been shown to be a reliable proxy measure for intestinal lavage in Swedish volunteers given an oral inactivated enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine (33). In the present study, significant antitoxin and antibacterial IgA antibody responses in feces were seen in, respectively, 67 and 37% of the volunteers given two doses of B-WC vaccine. The frequencies and magnitudes of the fecal IgA antibody responses were somewhat lower than those recently observed in intestinal lavage fluid after oral immunization with a B-WC cholera vaccine (20).

When the lavage procedure is used to assess intestinal immune responses after vaccination, approximately 10% of the volunteers have to be excluded from analyses due to very low levels of total IgA in their lavage fluids (1, 2). Analyses of fecal specimens are associated with similar disadvantages. In the present study, 12.5% of the volunteers had to be excluded due to very low fecal IgA concentrations (≤20 mg ml−1). Since determination of fecal IgA immune responses has some advantages compared to analyses of intestinal lavage fluid, e.g., in the ease of collecting and handling the specimens, we consider measurement of fecal immune responses feasible in situations where intestinal lavage is difficult to perform.

The kinetics of intestinal immune responses after oral immunization with B-WC cholera vaccine have been monitored in intestinal lavage fluid only up to 28 days after a second vaccine dose (15, 32). At that time, significant IgA antitoxin responses could still be detected in lavage fluid from two-thirds of the volunteers who initially had responded to the vaccine 7 to 9 days after immunization. Antibacterial IgA titers also remained elevated in most vaccinees. In the present study, we followed the kinetics of the intestinal immune responses for approximately 6 months after vaccination. Fecal antitoxin and antibacterial IgA antibody responses could still be detected in 50 and 43% of initially responding volunteers, respectively, although the magnitudes of the responses were lower than shortly after immunization.

The antitoxin IgA and IgG antibody titer increases and vibriocidal responses in serum are consistent with previous serological findings for Swedish volunteers who have been immunized with B-WC cholera vaccine (18, 20). The observation that individuals with high preimmune levels of vibriocidal antibodies had lower vibriocidal responses than those with low prevaccination titers is in accordance with findings for North American volunteers receiving recombinant B-WC cholera vaccine (27).

In earlier studies the kinetics of immune responses after oral cholera vaccination have been followed up to 5 years by measuring serum IgA and IgG antitoxin and vibriocidal antibodies (16, 19), since these antibodies have been shown to be useful indirect measures of the gut mucosal immune responses (15). Our data showed that 81% of initially responding volunteers still had significantly increased titers of IgA and IgG antitoxin in serum after 6 months, which is in accordance with previous findings for adult Swedish volunteers (16, 19). Vibriocidal antibody titer increases could still be found in most volunteers at follow-up, but due to the small number of subjects followed (five persons), no conclusions could be drawn. Earlier studies have shown a more rapid decrease in vibriocidal titers (16, 19). Six months after vaccination, sustained antitoxin and vibriocidal antibody levels were more often observed in serum than in feces.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (16X-09089) and the Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation with Developing Countries (SAREC).

We are grateful to Kerstin Andersson, Ingela Ahlstedt, and Ingrid Högberg for skillful technical assistance and to Lena Widerström for collecting the specimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Åhrén C, Wennerås C, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A-M. Intestinal antibody response after oral immunization with a prototype cholera B subunit-colonization factor antigen enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine. Vaccine. 1993;11:929–934. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90380-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Åhrén, C., M. Jertborn, and A.-M. Svennerholm. Unpublished data.

- 3.Boman G, Bäcker U, Larsson S, Melander B, Wåhlander L. Oral acetylcysteine reduces exacerbation rate in chronic bronchitis: report of a trial organized by the Swedish Society for Pulmonary Diseases. Eur J Respir Dis. 1983;64:405–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemens J D, Jertborn M, Sack D, Stanton B, Holmgren J, Khan M R, Huda S. Effect of neutralization of gastric acid on immune responses to an oral B subunit, killed whole-cell cholera vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:175–178. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemens J D, Sack D A, Harris J R, van Loon F, Chakraborty J, Ahmed F, Rao M R, Khan M R, Yunus M D, Huda N, Stanton B F, Kay B A, Walter S, Eeckels R, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Field trial of oral cholera vaccine in Bangladesh: results from three-year follow-up. Lancet. 1990;335:270–273. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90080-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czerkinsky, C., A.-M. Svennerholm, and J. Holmgren. 1993. Induction and assessment of immunity at enteromucosal surfaces in humans: implications for vaccine development. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16(Suppl. 2):S106–S116. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dertzbaugh M T, Elson C O. Cholera toxin as a mucosal adjuvant. In: Spriggs D R, Koff W C, editors. Topics in vaccine adjuvant research. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elson C O, Dertzbaugh M T. Mucosal adjuvants. In: Ogra P L, Lamm M E, McGhee J R, Mestecky J, Strober W, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of mucosal immunology. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 391–402. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari, V. 1980. Safety and drug interactions of oral acetylcysteine related to utilization data. Eur. J. Respir. Dis. 61(Suppl. 111):151–157. [PubMed]

- 10.Gaspari M M, Brennan P T, Solomon S M, Elson C O. A method of obtaining, processing and analyzing human intestinal secretions for antibody content. J Immunol Methods. 1988;110:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R K, Siber G R. Adjuvants for human vaccines—current status, problems and future prospects. Vaccine. 1995;13:1263–1276. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00011-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C, Lycke N, Svennerholm A-M. Mucosal immunity: implications for vaccine development. Immunobiology. 1992;184:157–179. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmgren J, Svennerholm A-M, Jertborn M, Clemens J, Sack D A, Salenstedt R, Wigzell H. An oral B subunit:whole cell vaccine against cholera. Vaccine. 1992;10:911–914. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90324-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isolauri E, Joensuu J, Suomalainen H, Luomala M, Vesikari T. Improved immunogenicity of oral D × RRV reassortant rotavirus vaccine by Lactobacillus casei GG. Vaccine. 1995;13:310–312. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)93319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jertborn M, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Saliva, breast milk, and serum antibody responses as indirect measures of intestinal immunity after oral cholera vaccination or natural disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:203–209. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.2.203-209.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jertborn M, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Five-year immunologic memory in Swedish volunteers after oral cholera vaccination. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:374–376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jertborn M, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral recombinant cholera B subunit-whole cell vaccine in Swedish volunteers. Vaccine. 1992;10:130–132. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90030-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jertborn M, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Evaluation of different immunization schedules for oral cholera B subunit-whole cell vaccine in Swedish volunteers. Vaccine. 1993;11:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90125-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jertborn M, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Immunological memory after immunization with oral cholera B subunit–whole-cell vaccine in Swedish volunteers. Vaccine. 1994;12:1078–1082. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jertborn M, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Intestinal and systemic immune responses in humans after oral immunization with a bivalent B subunit-O1/O139 whole cell cholera vaccine. Vaccine. 1996;14:1459–1465. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonson G, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A-M. Epitope differences in toxin-coregulated pili produced by classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li A, Pal T, Forsum U, Lindberg A A. Safety and immunogenicity of the live oral auxotrophic Shigella flexneri SFL124 in volunteers. Vaccine. 1992;10:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90070-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lycke N, Holmgren J. Strong adjuvant properties of cholera toxin on gut mucosal immune responses to orally presented antigens. Immunology. 1986;59:301–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIntyre O R, Feeley J C. Passive serum protection of the infant rabbit against experimental cholera. J Infect Dis. 1964;114:468–475. doi: 10.1093/infdis/114.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsson B, Johansson M, Gabrielsson J, Bolme P. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of reduced and oxidized N-acetylcysteine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;34:77–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01061422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez J, Holmgren J. Recombinant system for overexpression of cholera toxin B subunit in Vibrio cholerae as a basis for vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:481–485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez J L, Trofa A F, Taylor D N, Kuschner R A, DeFraites R F, Craig S C, Rao M R, Clemens J D, Svennerholm A-M, Sadoff J C, Holmgren J. Safety and immunogenicity of the oral, whole cell/recombinant B subunit cholera vaccine in North American volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1446–1449. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez J L, Vascuez B, Begue R E, Meza R, Castellares G, Cabezas C, Watts D M, Svennerholm A-M, Sadoff J C, Taylor D N. Protective efficacy of oral whole-cell/recombinant-B-subunit cholera vaccine in Peruvian military recruits. Lancet. 1994;344:1273–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheffner A L. The reduction in vitro in viscosity of mucoprotein solutions by a new mucolytic agent, N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;106:298–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb16647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Identification of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin by means of a ganglioside immunosorbent assay (GM1-ELISA) procedure. Curr Microbiol. 1978;1:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J, Black R, Levine M, Merson M. Serologic differentiation between antitoxin responses to infection with Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:514–522. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svennerholm A-M, Jertborn M, Gothefors L, Karim A M M M, Sack D A, Holmgren J. Mucosal antitoxic and antibacterial immunity after cholera disease and after immunization with a combined B subunit-whole cell vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:884–893. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svennerholm A-M, Åhrén C, Jertborn M. Vaccines against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections. In: Levine M M, Woodrow G C, editors. New generation vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1997. pp. 865–873. [Google Scholar]