ABSTRACT

Background

Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis and treatment of functional constipation (FC). The aim of this study was to explore the therapeutic effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable on slow transit constipation (STC).

Methods

Patients with STC who met the Rome IV criteria received Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable. Gastrointestinal transit time (GITT) and constipation‐related symptoms were assessed before and after receiving Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable. Additionally, a rat STC model was induced by loperamide and was treated with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable to evaluate whether Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could improve constipation in the rats and to explore the possible mechanisms involved.

Results

In patients with STC, Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable accelerated GITT and improved constipation‐related symptoms, including bowel movement frequency, hard bowel movement, incomplete defecation, defecation time, purgative measures, and stool form. In addition, Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable improved body weight, food intake, bowel movement, the fecal water content, and the intestinal propulsion rate in STC rats. It regulates the gut microbiota structure in rats; increases serum acetylcholine (Ach), 5‐hydroxytryptamine (5‐HT), substance P (SP), and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP); increases fecal long‐chain fatty acids (LCFAs); upregulates the mRNA expression of aquaporin 3 (AQP3) and aquaporin 3 (AQP8); and downregulates the mRNA expression of Toll‐like receptor 2 (TLR2), Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4), and interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β).

Conclusions

Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable ameliorated the GITT and constipation‐related symptoms of patients with STC and improved the STC in rats by regulating the gut microbiota and metabolism.

Keywords: Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, gut microbiota, metabolism, slow transit constipation

1. Introduction

Slow transit constipation (STC) is a common type of functional constipation (FC) characterized by slowed colonic transit, reduced bowel movement frequency, and dry stool, which not only causes a decrease in patients' physiological function but also seriously affects their quality of life [1]. The pathogenesis of STC is complex, and intestinal neuropathy, impaired neurotransmission, and abnormal hormonal effects play important roles in the development of STC [2, 3]. Due to its complex pathogenesis, the treatment of STC is difficult, and treatment results are unsatisfactory [4]. Therefore, improving the therapeutic efficacy of STC is important.

Studies have shown that the gut microbiota plays a key role in health and influences various activities of host physiology, including gut motility [5, 6]. The normal gut microecology in the human body is relatively balanced. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome occurs once this balance is disrupted by external factors, which leads not only to an increase in pathogenic bacteria but also to a decrease in beneficial bacteria, resulting in abnormal gastrointestinal motility and some constipation symptoms. Dysfunction of the gut microbiota is also closely related to constipation [7, 8, 9]. Khalif et al. [7] reported that patients with FC had reduced levels of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides and increased levels of Escherichia coli , Staphylococcus aureus , and fungi. The abundance of Firmicutes and Klebsiella increased, whereas the abundance of Bacteroides decreased in the STC mice [10]. Dietary fiber, probiotics/prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation were used to treat FC by regulating the gut microbiota [11, 12, 13, 14]. Prebiotic/probiotic mixtures can improve constipation in rats, restore gut microbiota structure, and increase intestinal SCFA levels [15]. Makizaki et al. [16] reported that the administration of Bifidobacterium G9‐1 to rats with loperamide‐induced constipation significantly improved constipation symptoms, regulated the gut microbiota, and reversed pathological changes in intestinal butyric acid, 5‐hydroxytryptamine (5‐HT), serum dopamine, and acetylcholine (Ach). Therefore, probiotics may improve constipation mainly by regulating the gut microbiota and its metabolites.

Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable is a probiotic product that includes Bifidobacterium longum , Lactobacillus bulgaricus , and Streptococcus thermophilus and is often used to treat constipation and shows a certain efficacy. However, few studies have explored the therapeutic mechanisms by which Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple affects constipation. The purposes of this study were to analyze whether Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viability could accelerate gastrointestinal transit time (GITT) and improve constipation‐related symptoms in patients with STC and to explore its mechanism through loperamide‐induced STC in rats.

2. Methods

2.1. Clinical Trials

2.1.1. Participants and Study Methods

Patients with STC aged 18 – 65 years who met the Rome IV criteria were recruited from the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University. All patients underwent a colonoscopy to exclude organic disease. The protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University. All subjects provided written informed consent.

All patients received 2000 mg of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable (Inner Mongolia Shuangqi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Inner Mongolia, China) three times a day for 4 weeks. The patients were required to complete the Constipation Severity Scale (CSS), and GITT was determined on Day 0 (before receiving Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable) and Day 28 (after receiving Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable), and the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) was used to assess their stool form before and after treatment.

2.1.2. GITT

The GITT is used to assess GI motility. On Day 0 and Day 28, all FC patients were required to ingest SITZMARKS Radiopaque Markers (8100‐10 capsules w/24R, Konsyl Pharmaceuticals Inc., USA), which contain 24 radiopaque barium rings, and received abdominal x‐rays 48 h later. During the 48 h, patients were asked to maintain their lifestyle as usual and not to take drugs that affect GI motility or other methods to promote defecation. We recorded and compared the number of radiopaque barium rings excreted through the anus.

2.1.3. CSS and BSFS

The CSS was used to assess bowel movement frequency, hard bowel movement, incomplete feeling of defecation, abdominal pain, defecation time, purgative measures, and awareness of defecation, with ratings determined using a 3‐ or 5‐point Likert scoring system. The BSFS, a graded visual scale of stool type from Type 1 (hard lumps) to Type 7 (watery diarrhea), was used to assess patients' stool form. All FC patients were required to complete the CSS and BSFS on Day 0 and Day 28 for assessment of constipation symptoms and stool form.

2.2. Animal Experiments

2.2.1. Experimental Animals and Protocols

Specific pathogen‐free (SPF) Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing 160 – 180 g were purchased from Zhuhai BesTest Bio‐Tech Co. Ltd. (Zhuhai, China). All rats were allowed to adapt to the following environmental conditions for 7 days before the experiment: temperature 25°C ± 2°C, humidity 50% ± 5%, and a 12‐h light/dark cycle (07:30–19:30). The experiments were approved by the Animal Care Review Committee of Sun Yat‐sen University.

An STC rat model was induced by loperamide hydrochloride (L4762, Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). All rats were randomly divided into the following three groups, with seven rats in each group: the control group (CTR group), loperamide group (LOP group), and Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable group (BTV group). The rats in the LOP and BTV groups were injected subcutaneously with 5 mg kg−1 of body weight loperamide in 0.9% saline solution twice daily at 09:00 am and 5:00 pm for 14 days, whereas the rats in the CTR group were injected with 0.9% saline. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable was dissolved in 0.9% saline to a final concentration of 200 mg mL−1. The rats in the BTV group were treated with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable (200 mg kg−1 body weight) by gavage 1 h after injection of LOP, and at the same time, the rats in the CTR and LOP groups were administered 0.9% saline.

2.2.2. Body Weight and Food Intake

During the experiments, to evaluate trends in body weight change and food intake in the rats, weight and food intake were measured daily at 8:00 a.m. using a precision electronic balance (METTLER TOLEDO, ME2002E/02). Food intake was measured according to the following equation:

2.2.3. Fecal Parameters

During the experiment, the feces excreted by the rats were collected between 9:00 a.m. each day and 9:00 a.m. the following day to evaluate bowel movement frequency. Fresh feces from the rats were collected and weighed at 9:00 a.m., dried at 60°C for 24 h, and weighed to calculate the fecal water content. The fecal water content was calculated according to the following equation:

2.2.4. Specimen Collection

After the experiments, fresh feces were collected from all rats and stored at −80°C until analysis. Then, all rats were fasted for 12 h but allowed free access to water. Before specimen collection, the rats were administered 1.0 mL of activated charcoal solution by gavage, and 30 min later, the rats were anesthetized. Blood samples were collected from the heart, and serum was obtained through centrifugation. The rats were then euthanized and dissected, and the small intestine was removed (from the stomach to the ileum). The distance covered by the charcoal and the total length of the small intestine were measured. Subsequently, segments of the colon were removed and washed with PBS, tissue sections were embedded in polyformaldehyde solution for paraffin embedding, and the remaining sections were cut into scraps and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis.

2.2.5. Intestinal Propulsive Rate

For each rat, the distance covered by the charcoal and the total length of the small intestine were measured to calculate the intestinal propulsive rate. The intestinal propulsive rate was calculated according to the following equation:

2.2.6. Enzyme‐Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of serum 5‐HT, substance P (SP), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and motilin (MTL) were measured with corresponding ELISA kits (Jiangsu Meimian) following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.2.7. RNA Extraction and Real‐Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT‐qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the colon tissues of the rats using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Evo M‐MLV RT Master Mix (AG11706, Accurate Biology, China) was used for RNA reverse transcription, and SYBR Green Pro Taq HS Premix II (AG11702, Accurate Biology, China) was used for the quantitative PCR analysis of gene expression. The mRNA gene expression levels of aquaporins (AQP3 and AQP8) and inflammatory cytokines (TLR2, TLR4, and IL‐1β) were quantified. The relative level of the target mRNA was normalized to the β‐actin level, and the primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

The primer sequences used in this study.

| Gene names | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| β‐Actin (forward) | GATTACTGCCCTGGCTCCTAG |

| β‐Actin (reverse) | GAAAGGGTGTAAAACGCAGCTC |

| AOP3 (forward) | GCTGCTGTGCCTATGAACTGA |

| AOP3 (reverse) | CTTCTTGGGTGCTGGGATTGT |

| AOP8 (forward) | GGGATCTCTGGAGCCTGCATG |

| AOP8 (reverse) | CTGCTGCTGTCAGAGTGGCTC |

| TLR2 (forward) | TGGAGGTCTCCAGGTCAAATC |

| TLR2 (reverse) | ACCAGCAGCATCACATGACA |

| TLR4 (forward) | GATCTGAGCTTCAACCCCCT |

| TLR4 (reverse) | TTGTCTCAATTTCACACCTGGA |

| IL‐1β (forward) | CTTCCTTGTGCAAGTGTCTGA |

| IL‐1β (reverse) | ATCTGGACAGCCCAAGTCAAG |

2.2.8. 16S rRNA High‐Throughput Sequencing

The extraction, sequencing, and analysis of fecal microbiota DNA from rat feces were conducted as described in our previous study [17].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 and R4.1.1 statistical analysis software, and GraphPad Prism Version 8.0 was used for chart generation. The measurement data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (−x ± s). Student's t‐test or Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparing the differences between groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Subjects

Twenty patients with STC who met the Rome IV criteria (14F, 6 M; age 39.80 ± 11.74 years) were recruited for our study. All patients voluntarily participated in this study and provided written informed consent.

3.2. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable Accelerated the Gastrointestinal Transit Time in Patients With STC

After treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable strains, the STC patients excreted more radiopaque barium rings than controls (8.85 ± 8.922 vs. 14.80 ± 10.324, p = 0.012), which showed that the GITT of STC patients accelerated as the result of treatment (Figure 1 and Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Abdominal x‐ray of a patient with STC before and after treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable. (A) Pretreatment. (B) Posttreatment.

TABLE 2.

The radiopaque barium rings excreted by patients with STC.

| Patient ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −x ± s | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pretreatment | 16 | 17 | 0 | 14 | 23 | 0 | 19 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 22 | 17 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 8.85 ± 8.922 |

| Posttreatment | 24 | 23 | 0 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 24 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 22 | 13 | 0 | 15 | 23 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 24 | 14.80 ± 10.324 |

3.3. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable Improved Constipation‐Related Symptoms in Patients With STC

After treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, the CSS scores for bowel movement frequency, hard bowel movement, incomplete feeling of defecation, defecation time, and purgative measures of patients with STC decreased (p < 0.05), and their stool form improved according to the BSFS (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

The CSS and BSFS of patients with STC.

| Symptoms | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel movement of frequency | 1.20 ± 0.834 | 0.50 ± 0.513 | 0.008* |

| Hard bowel movement | 3.30 ± 0.923 | 2.05 ± 0.999 | 0.000* |

| Incomplete feeling of defecation | 1.90 ± 1.071 | 1.40 ± 0.754 | 0.004* |

| Abdominal pain | 0.75 ± 1.020 | 0.35 ± 0.587 | 0.054 |

| Defecation time | 2.15 ± 0.875 | 1.75 ± 0.786 | 0.005* |

| Purgative measures | 0.50 ± 0.607 | 0.15 ± 0.489 | 0.008* |

| Have awareness of defecation but fail | 0.50 ± 0.513 | 0.35 ± 0.489 | 0.083 |

| Stool form | 6.85 ± 0.489 | 5.60 ± 1.465 | 0.002* |

Note: The asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05).

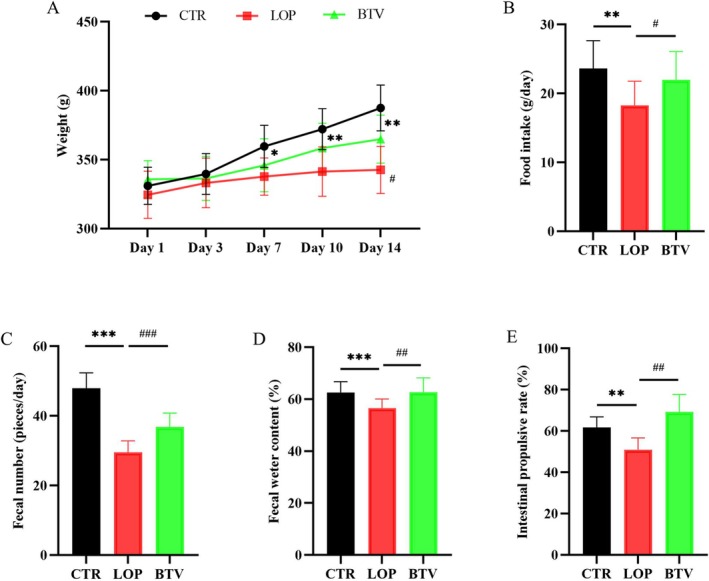

3.4. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable Improves Physiological Indices in Rats With STC

After intervention with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, physiological indices of the rats in the STC group were significantly improved. As shown in Figure 2A, the body weights of rats in the LOP groups were significantly lower than those in the CTR groups, and treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could increase the body weight of rats in the STC group. The daily food intake of the rats in the BTV group was greater than that of the rats in the LOP group (Figure 2B). In addition, we found that the fecal number, fecal water content and intestinal propulsive rate of rats in the LOP group were significantly lower than those in the CTR group; however, after treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, the constipation‐related symptoms significantly improved (Figure 2C–E). The results showed that treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could improve symptoms in rats with STC.

FIGURE 2.

The effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable improves on the physiological indices in rats with STC. (A) Body weight. (B) Food intake. (C) Fecal number. (D) Fecal water content. (E) Intestinal propulsive rate. Data were represented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, LOP versus CTR group; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001, LOP versus BTV group.

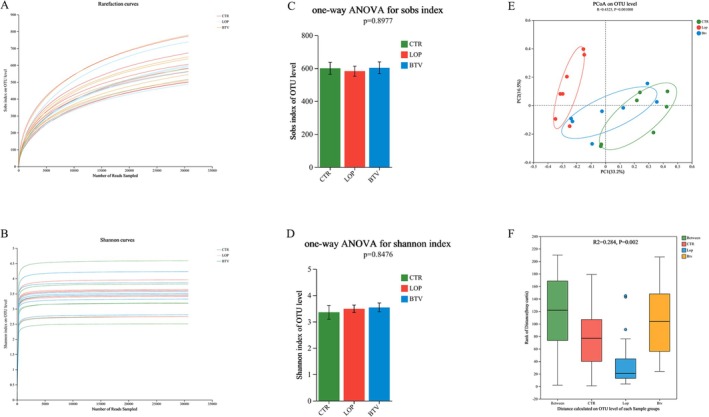

3.5. Effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable on the Structures of the Gut Microbiota in Rats

Based on the sequencing results of the rat feces, rarefaction curves and Shannon curves were generated based on the Sobs index and Shannon index, respectively, at the OUT level (Figure 3A,B). As the number of reads detected for each sample increased, both the rarefaction curve and Shannon curve tended to flatten, indicating that the sequencing data reached saturation and covered the majority of species in the gut microbiota community. The alpha diversity of the fecal microbiota was analyzed, and the results showed no significant difference in the Sobs index or Shannon index among the three groups, which indicated no significant difference in the community richness or diversity of the fecal microbiota among the three groups of rats (Figure 3C,D). The results of the PCoA showed a significant separation between the fecal microbiota communities of the LOP and BTV groups and those of the CTR group (Figure 3E). Adonis analysis was used to test the intergroup differences in the fecal microbiota among the three groups, and the results revealed significant differences among the groups (Figure 3F, R 2 = 0.284, p = 0.002).

FIGURE 3.

The results of the analysis of the gut microbiota diversity in rats. (A) Rarefaction curves. (B) Shannon curves. (C) Sobs index. (D) Shannon index. (E) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). (F) Adonis analysis. The X‐axis represents the distance values within or between groups, the boxes corresponding to between represent the distance values of intergroup differences, and the remaining boxes represent the distance values of intragroup differences. The Y‐axis scale represents the size of the distance value. The data are presented as the means ± SD.

To identify the specific bacterial taxa in the three groups, the compositions of the gut microbiota from the three groups were compared using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) (Figure S1). The cladogram in Figure S1A displays those taxa that were significantly enriched in the three groups. Three key genera dominated in the CTR group: Lactobacillus murinus , Lactobacillus intestinalis , and the gut metagenome Lactobacillus. The key species in the LOP group were Faecalibaculum rodentium and Bifidobacterium pseudolongum . Furthermore, two major genera were detected in the BTV group, namely, the uncultured bacterium Turicibacter and the uncultured organism Ruminococcus gauvreauii . Furthermore, linear discriminant analysis coupled with LEfSe identified the microbial taxa that accounted for the greatest differences among the three groups. The taxa that are characteristic of each group according to the LEfSe are indicated as biomarkers in Figure S1B.

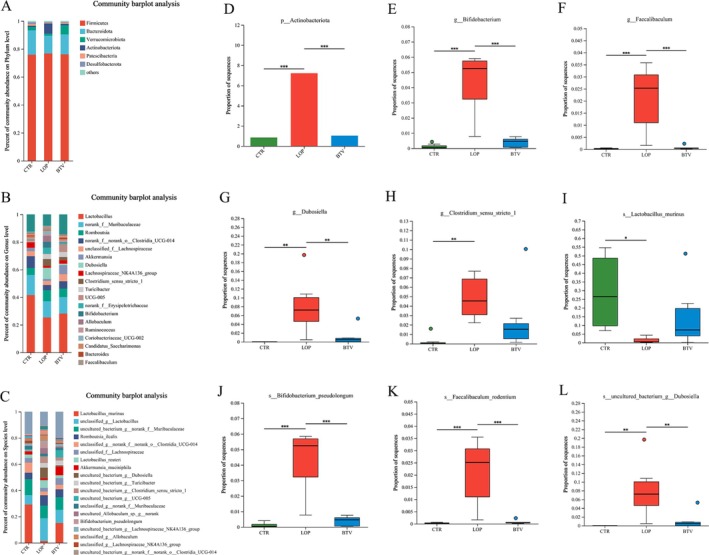

3.6. Effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable on the Composition of Gut Microbiota in Rats

We analyzed the fecal microbiota of the three groups of rats at the phylum, genus, and species levels. At the phylum level, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Actinobacteriota were the dominant bacterial phyla in the feces (Figure 4A), and Actinobacteriota were significantly decreased after treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable compared to those in the LOP group (Figure 4D). At the genus level, Lactobacillus, Muribaculaceae, Romboutsia, Clostridia UCG‐014, and unclassified Lachnospiraceae were the dominant bacterial genera in all fecal samples (Figure 4B). Compared to those in the LOP group, the abundances of Bifidobacterium, Faecalibaculum, Dubosiella, and Clostridium sensu stricto 1 in the CTR and BTV groups were significantly lower (Figure 4E–H). At the species level, L. murinus , unclassified Lactobacillus, the uncultured bacterium Muribaculaceae, and Romboutsia ilealis were the dominant species (Figure 4C). Compared to those in the CTR group, the abundance of L. murinus was significantly decreased, and Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could increase the abundance of L. murinus , whereas the abundances of B. pseudolongum , F. rodentium , and the uncultured bacterium Dubosiella were significantly greater in the LOP group than in the CTR and BTV groups (Figure 4I–L). These findings indicate that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could regulate the gut microbiota of rats with constipation.

FIGURE 4.

Composition of gut microbiota among the three groups. (A) Family level. (B) Genus level. (C) Specials level. (D) Major differential microbiota at the family level. (E–H) Major differential microbiota at the genus level. (I–L) Major differential microbiota at the specials level. Data were represented as mean ± SD.

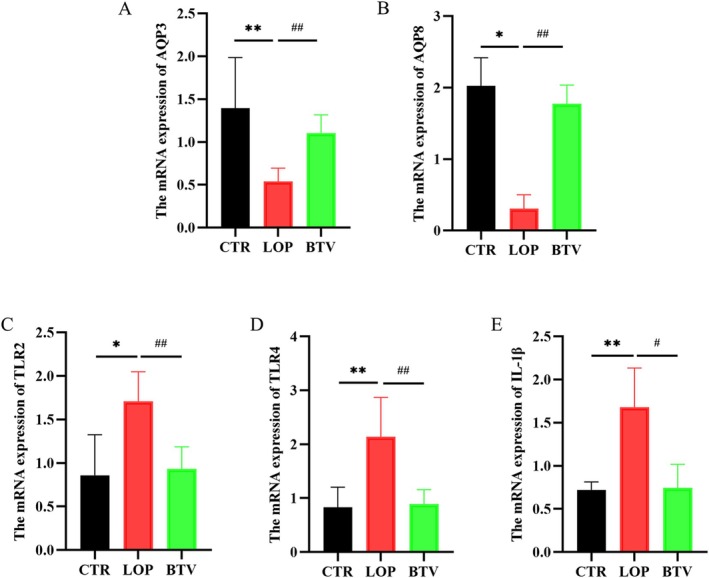

3.7. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable Changes the mRNA Expression of Aquaporins in Colon Tissues and Inflammatory Cytokines in Rats With STC

In our previous study, we found that rifaximin could improve loperamide‐induced constipation in rats by modulating water metabolism and facilitating intestinal inflammation [17]. Therefore, we explored the mRNA expression of aquaporins and inflammatory cytokines in the colon of constipated rats by RT‐qPCR (Figure 5). Compared with that in the CTR and BTV groups, the mRNA expression of the AQP3 and AQP8 genes in the colon tissue of the LOP group was significantly lower (Figure 5A,B). In addition, the feces stay in the colon for a long time and repeatedly stimulate the colon mucosa, which can cause inflammatory changes in the colon tissue of rats. We found that the mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines, including TLR2, TLR4, and IL‐1β, in the LOP group rats were significantly upregulated compared to that in the CTR and BTV groups (Figure 5C–E). These findings indicate that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable might modulate water metabolism and facilitate intestinal inflammation in rats with constipation.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable on the mRNA Expression of aquaporins and inflammatory cytokines in colon tissues of rats. (A,B) mRNA expression of aquaporins, including AQP3 (A) and AQP8 (B). (C–E) mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines, including TLR2 (C), TLR4 (D), and IL‐1β (E). Data were represented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, LOP versus CTR group; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, LOP versus BTV group.

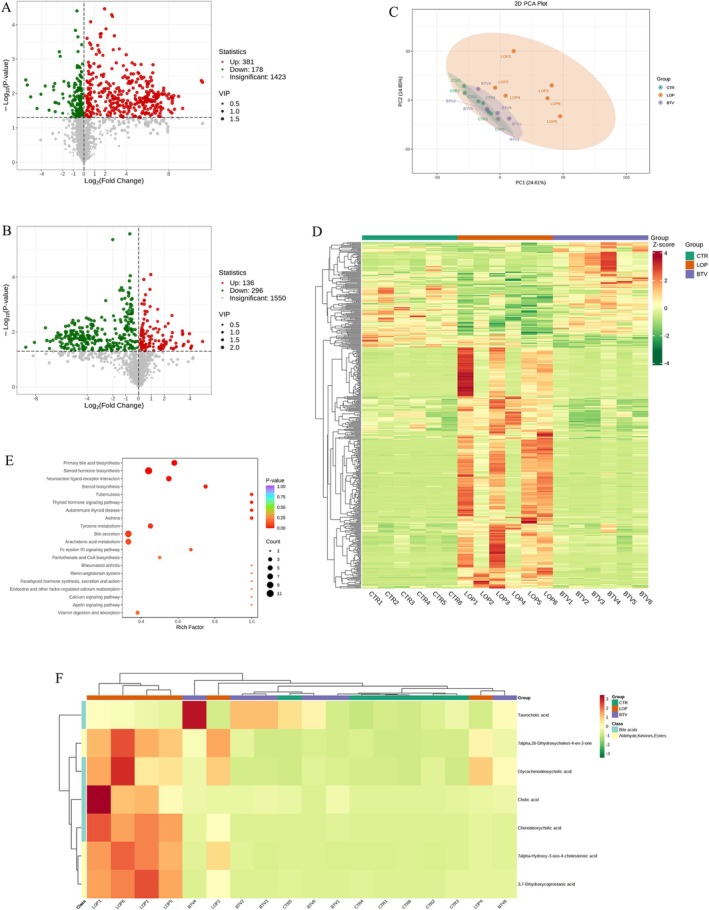

3.8. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable Regulated the Serum Metabolites in Constipated Rats

To analyze the effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable on metabolites in the serum of constipated rats, we collected serum samples from all rats for untargeted metabolomic analysis through LC‐MS/MS. As shown in the results of the volcano plot, there were significant differences in the serum metabolites in the LOP group compared with those in the CTR and BTV groups (Figure 6A,B). Based on the results of the principal component analysis (PCA) and heatmap, compared with those in the LOP group, the metabolite compositions in the BTV group were more similar to those in the CTR group (Figure 6C,D). Then KEGG enrichment analysis was subsequently performed on the serum metabolites of each group of rats. Primary bile acid (BA) biosynthesis, bile secretion, and steroid hormone biosynthesis were significantly different between the groups (Figure 6E). The results of KEGG heatmap analysis showed significant differences in metabolic pathways, including bile secretion and aldehyde, ketone, and ester pathways, between the LOP group and the CTR and BTV groups (Figure 6F). These findings indicate that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could regulate metabolic pathways, including bile secretion and aldehyde, ketone, and ester pathways.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable on the serum metabolites in constipated rats. (A) Volcano plot of differential metabolites between CTR and LOP groups. (B) Volcano plot of differential metabolites between LOP and BTV groups. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) based on all identified metabolites. (D) Heatmap of the compounds between three groups. (E) KEGG enrichment analysis of the differential metabolic pathways between the CTR, LOP, and BTV groups. (F) KEGG heatmap of the differential metabolic pathways between the CTR, LOP, and BTV groups.

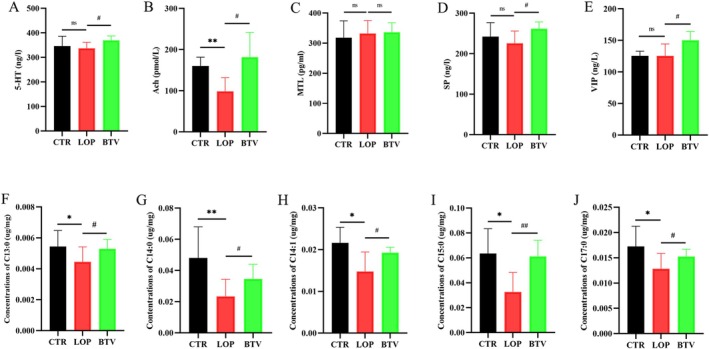

3.9. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus Triple Viable Changes Serum Neurotransmitters and Fecal Long‐Chain Fatty Acids (LCFAs) in Rats With STC

Neurotransmitters play a major role in colonic motility. We tested the serum levels of neurotransmitters, including 5‐HT, Ach, MTL, SP, and VIP (Figure 7A–E). We found that treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable increased the levels of 5‐HT, Ach, SP, and VIP. A study showed that LCFAs in the colon lumen can promote muscle contraction and increase stool frequency [18]. Therefore, we analyzed the levels of LCFAs in the feces of all rats by LC‐MS/MS. We found that the levels of tridecanoic acid (C13:0), myristic acid (C14:0), myristoleic acid (C14:1), pentadecanoic acid (C15:0), and heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) were significantly lower in the constipated group than in the CTR group and Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable elevated the levels of those LCFAs (Figure 7F–J), further demonstrating that the ability of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable to alleviate constipation is reduced.

FIGURE 7.

The levels of neurotransmitters and LCFAs in the rats. (A–E) Neurotransmitters: 5‐HT (A), Ach (B), MTL (C), SP (D), and VIP (E). (F–J) LCFAs: C13:0 (F), C14:0 (G), C14:1 (H), C15:0 (I), and C17:0 (J). Data were represented as mean ± SD. ns p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, LOP versus CTR group; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, LOP versus BTV group.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could significantly increase GITT and relieve constipation‐related symptoms in patients with STC. After treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, the constipation‐related variables of loperamide‐induced STC in rats were significantly increased, including body weight, food intake, bowel movement, fecal water content, and the intestinal propulsion rate, which significantly increased in rats with loperamide‐induced STC. In addition, Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable regulated gut microbiota, serum, and fecal metabolites; upregulated the mRNA expression of aquaporins; and downregulated inflammatory cytokines in the colon tissues of STC rats, which might be potential mechanisms for improving constipation.

As mentioned earlier, the Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable used in our study is a probiotic product that includes B. longum , L. bulgaricus , and S. thermophilus . We found that supplementation with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could accelerate GITT and improve constipation‐related variables, including the frequency of bowel movements, hard bowel movements, incomplete feeling of defecation, defecation time, purgative measures, and stool form, in FC patients. These results were similar to those of Koebnick et al. [19] and Ouwehand et al. [20]. Bifidobacteria are the most important natural bacteria in the infant intestinal tract and widely exist in the digestive system of humans and animals, and its physiological effect on the human body is far greater than that of other bacteria [21]. On the one hand, supplementation with bifidobacteria changes the structure of the gut microbiota [22] and increases the production of 5‐HT by enterochromaffin (EC) cells, thus stimulating intestinal motility and promoting signal transduction through the brain–gut axis and intestinal contraction activity [23]. On the other hand, bifidobacteria can stimulate the production of SCFAs in the intestinal tract and further promote intestinal motility [24]; moreover, they also promote the production of lactic acid, lower the intestinal pH, shorten the whole intestinal transit time, promote intestinal peristalsis, and relieve the symptoms of constipation [25]. There are some differences in the ability of bifidobacteria to relieve constipation. B. longum and Bifidobacterium infantis are more effective at relieving constipation [26]. Therefore, we speculated that the increase in GITT in FC patients after treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable was mainly related to B. longum supplementation and that accelerating GITT could improve constipation symptoms in FC patients to a certain extent. Yoon et al. [27] showed that the other two probiotics— L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus —could significantly ameliorate stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation. However, Dimidi et al. [28] found that a 4‐week intervention of Bifidobacterium lactis NCC2818 in FC patients did not result in a greater reduction in the GTT or affect other constipation‐related outcomes, such as the frequency, consistency, pH, SCFA content, and water content of stools and B. lactis NCC2818 did not result in alterations in fecal microbiota, which was contrary to that reported in previous studies. The opposite conclusions from these studies indicate that differences in therapeutic effects exist among various probiotics or strains for patients with constipation. Therefore, further studies are needed to establish which probiotic strains are the most efficacious for the management of chronic constipation.

To further understand the mechanisms by which Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable is involved in constipation, loperamide‐induced STC rats were treated with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, and the fecal microbiota structure of all rats was analyzed by 16S rRNA high‐throughput sequencing. Based on the beta diversity results, significant differences were observed in the structure of the fecal microbiota among the three groups, and Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could regulate the fecal microbiota of constipated rats to make them more similar to the control rats, suggesting that the fecal microbiota induced by loperamide constipation was restored after Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable treatment. Additionally, as a result of the treatment, the relative abundance of L. murinus was increased, and the relative abundances of Faecalibaculum, Dubosiella, Clostridium sensu stricto 1, B. pseudolongum , F. rodentium , and the uncultured bacterium Dubosiella were decreased. L. murinus significantly reduced hepatic inflammatory cell aggregation and inflammatory factor expression in mice with primary sclerosing cholangitis [29] and decreased the levels of circulating microbial antigens and systemic inflammatory markers, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) in calorie‐restricted mice [30]. In addition, L. murinus alleviated deoxynivalenol‐induced intestinal barrier disruption [31]. B. pseudolongum , which was significantly increased in the LOP group, was reported to reduce 5‐HT content in the colonic mucosa by diminishing EC cells [32, 33].

Previous studies have shown that certain inflammatory changes occur in the colon tissue of rats with loperamide‐induced constipation [17, 34]. Therefore, we detected the mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines, including TLR2, TLR4, and IL‐1β, in rat colon tissue. We found that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could downregulate the mRNA expression of TLR2, TLR4, and IL‐1β, indicating that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable supplementation could ameliorate inflammatory changes in the colon tissue of STC rats. In addition, the pathogenesis of STC is closely related to abnormalities in colonic aquaporins [35]. The expression of aquaporins can affect colonic water metabolism and intestinal permeability [36, 37]. In our study, the levels of the aquaporins AQP3 and AQP8 were upregulated in the colon tissue of STC rats after treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, which is consistent with the results of Shi et al. and Kim et al. [38, 39], indicating that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable might improve constipation by modulating intestinal epithelial water metabolism.

Moreover, we used a nontargeted metabolome to detect the serum metabolites of all rats. Metabolites are influenced mainly by the gut microbiota. Correspondingly, significant differences were in the serum metabolites among the three groups. According to the results of our study, compared with those in the LOP group, the serum metabolite composition of the rats in the BTV group was more similar to that in the CTR group (Figure 7D). The BA metabolic pathway might play a role in the ability of Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable to improve constipation in rats, and the levels of cholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid, and glycochenodeoxycholic acid in the LOP group rats were significantly greater than those in the CTR and BTV groups. Cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid are primary BAs that are synthesized in the liver and then enter the intestine, and some of them (5%–10%) are subjected to extensive biotransformation by intestinal bacteria, mainly the genera Bacteroides, Eubacterium, and Clostridium [40, 41]. Fast transit through the colon could reduce the absorption of BA, whereas slow transit through the colon could increase the absorption of BA [42]. In our study, the levels of BAs were greater in the constipated rats than in the other groups, possibly because the gastrointestinal transit of the constipated rats was significantly lower than that in the CTR and BTV groups, indicating that the BAs could stay in the ileum longer in constipated rats and more BAs could be reabsorbed into the blood [17].

Neurotransmitters, such as 5‐HT, Ach, MTL, SP, and VIP, play important roles in gastrointestinal motility. Ach is an enteric neurotransmitter that affects nerves, mucosae, and smooth muscle cells in the colon [43]. In this study, the serum Ach levels in constipated rats were significantly lower than those in control rats, and Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could increase Ach levels in these rats. Similarly, Wang et al. [44] reported that luteolin treatment improved constipation‐related symptoms in FC models and luteolin increased the levels of intestinal motility‐related biomarkers, including SP, VIP, and Ach. In addition, although no significant difference was observed between the rats in the CTR and LOP groups, the levels of 5‐HT, SP and VIP were increased in the rats after treatment with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable. These findings indicate that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable effectively regulates the excitability of the enteric nervous system.

Fatty acid analogs may be key metabolites involved in constipation [45]. In this study, we performed a targeted assay of LCFA metabolites in rat feces by LC‐MS/MS. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable was found to increase the levels of C13:0, C14:0, C14:1, C15:0, and C17:0, which is consistent with previously reported results [18, 45]. Studies have shown that dietary supplementation with LCFAs regulates the gut microbiota to promote the proliferation of beneficial bacteria and improve the intestinal barrier [46, 47]. LCFAs can promote rat colonic muscle contraction and increase stool frequency [18]. Furthermore, LCFAs decreased fluid tolerance, accelerated transit, and abnormal motility in the human colon [48]. However, Ogawa et al. [49] proposed that intestinal infusion of LCFAs strongly suppresses food intake and gut motility and LCFA receptor agonists promote relaxation of the porcine lower esophageal sphincter [50]. These conflicting results indicate that more research is needed to explore the effects of LCFAs on colon motility.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could accelerate GITT and improve constipation‐related symptoms in patients with STC. By inducing a STC rat model and intervening with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable in the STC rats, we found that body weight, food intake, bowel movement, fecal water content, and intestinal propulsive rate of the STC rats were significantly increased after inducing a STC rat model and intervening with Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable. Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable could regulate the gut microbiota of rats by increasing L. murinus , decreasing B. pseudolongum , upregulating the expression of the aquaporins AQP3 and AQP8, and downregulating the expression of TLR2, TLR4, and IL‐1β, which might improve colonic water metabolism and inflammation. Moreover, the levels of serum neurotransmitters, including 5‐HT, Ach, SP, and VIP, and fecal LCFAs, including C13:0, C14:0, C14:1, C15:0, and C17:0, were significantly increased after treatment with the Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable, which might improve the GITT of STC rats. Our study provides a theoretical basis for the regulation of gut microbiota structure and metabolism to alleviate STC using Bifidobacterium Lactobacillus triple viable.

Ethics Statement

The experiments were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University and Animal Care Review Committee of Sun Yat‐sen University, and all subjects have signed informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Identification of most characteristic taxa among three groups by linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe). (A) Analysis of taxonomic abundances on differentially enriched taxa in appendiceal content of each group using LEfSe. (B) Most significant differences among four experiment groups after LDA using a threshold score of > 3.5.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participants who participated in this study.

Mei Luo and Peiwei Xie contributed equally to this article.

Funding: This research was supported by the GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2025A1515012764).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Wang H. L., “Understanding the Pathogenesis of Slow‐Transit Constipation: One Step Forward,” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 60 (2015): 2216–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomita R., Tanjoh K., Fujisaki S., Ikeda T., and Fukuzawa M., “Regulation of the Enteric Nervous System in the Colon of Patients With Slow Transit Constipation,” Hepato‐Gastroenterology 49 (2002): 1540–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Björnsson E. S., Chey W. D., Hooper F., Woods M. L., Owyang C., and Hasler W. L., “Impaired Gastrocolonic Response and Peristaltic Reflex in Slow‐Transit Constipation: Role of 5‐HT(3) Pathways,” American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 283 (2002): G400–G407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bharucha A. E. and Lacy B. E., “Mechanisms, Evaluation, and Management of Chronic Constipation,” Gastroenterology 158 (2020): 1232–1249.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boeckxstaens G., Camilleri M., Sifrim D., et al., “Fundamentals of Neurogastroenterology: Physiology/Motility ‐ Sensation,” Gastroenterology 150 (2016): 1292–1304.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Obata Y. and Pachnis V., “The Effect of Microbiota and the Immune System on the Development and Organization of the Enteric Nervous System,” Gastroenterology 151 (2016): 836–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khalif I. L., Quigley E. M., Konovitch E. A., and Maximova I. D., “Alterations in the Colonic Flora and Intestinal Permeability and Evidence of Immune Activation in Chronic Constipation,” Digestive and Liver Disease 37 (2005): 838–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang J. K. and Yao S. K., “Roles of Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in Pathogenesis of Functional Constipation,” Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021 (2021): 5560310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang S., Wang R., Li D., Zhao L., and Zhu L., “Role of Gut Microbiota in Functional Constipation,” Gastroenterology Report 9 (2021): 392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zeyue Y. U., Liyu H., Zongyuan L. I., et al., “Correlation Between Slow Transit Constipation and Spleen Deficiency, and Gut Microbiota: A Pilot Study,” Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 42 (2022): 353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Del Piano M., Carmagnola S., Anderloni A., et al., “The Use of Probiotics in Healthy Volunteers With Evacuation Disorders and Hard Stools: A Double‐Blind, Randomized, Placebo‐Controlled Study,” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 44, no. Suppl 1 (2010): S30–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lai H., Li Y., He Y., et al., “Effects of Dietary Fibers or Probiotics on Functional Constipation Symptoms and Roles of Gut Microbiota: A Double‐Blinded Randomized Placebo Trial,” Gut Microbes 15 (2023): 2197837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chu J. R., Kang S. Y., Kim S. E., Lee S. J., Lee Y. C., and Sung M. K., “Prebiotic UG1601 Mitigates Constipation‐Related Events in Association With Gut Microbiota: A Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Intervention Study,” World Journal of Gastroenterology 25 (2019): 6129–6144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang C., Hu T., Xue X., et al., “Multi‐Omics Analysis of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation's Impact on Functional Constipation and Comorbid Depression and Anxiety,” BMC Microbiology 23 (2023): 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim M. G., Jo K., Cho K., Park S. S., Suh H. J., and Hong K. B., “Prebiotics/Probiotics Mixture Induced Changes in Cecal Microbiome and Intestinal Morphology Alleviated the Loperamide‐Induced Constipation in Rat,” Food Science of Animal Resources 41 (2021): 527–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makizaki Y., Uemoto T., Yokota H., Yamamoto M., Tanaka Y., and Ohno H., “Improvement of Loperamide‐Induced Slow Transit Constipation by Bifidobacterium Bifidum G9‐1 Is Mediated by the Correction of Butyrate Production and Neurotransmitter Profile due to Improvement in Dysbiosis,” PLoS ONE 16 (2021): e0248584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luo M., Xie P., Deng X., Fan J., and Xiong L., “Rifaximin Ameliorates Loperamide‐Induced Constipation in Rats Through the Regulation of Gut Microbiota and Serum Metabolites,” Nutrients 15 (2023): 4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao L., Huang Y., Lu L., et al., “Saturated Long‐Chain Fatty Acid‐Producing Bacteria Contribute to Enhanced Colonic Motility in Rats,” Microbiome 6 (2018): 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koebnick C., Wagner I., Leitzmann P., Stern U., and Zunft H. J., “Probiotic Beverage Containing Lactobacillus casei Shirota Improves Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients With Chronic Constipation,” Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology 17 (2003): 655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ouwehand A. C., Lagström H., Suomalainen T., and Salminen S., “Effect of Probiotics on Constipation, Fecal Azoreductase Activity and Fecal Mucin Content in the Elderly,” Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism 46 (2002): 159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato K., Odamaki T., Mitsuyama E., Sugahara H., Xiao J. Z., and Osawa R., “Age‐Related Changes in the Composition of Gut Bifidobacterium Species,” Current Microbiology 74 (2017): 987–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bermudez‐Brito M., Plaza‐Díaz J., Muñoz‐Quezada S., Gómez‐Llorente C., and Gil A., “Probiotic Mechanisms of Action,” Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism 61 (2012): 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agus A., Planchais J., and Sokol H., “Gut Microbiota Regulation of Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease,” Cell Host & Microbe 23 (2018): 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quigley E. M., “Bacteria: A New Player in Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders‐‐Infections, Bacterial Overgrowth, and Probiotics,” Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 36, no. 3 (2007): 735–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waller P. A., Gopal P. K., Leyer G. J., et al., “Dose‐Response Effect of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 on Whole Gut Transit Time and Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Adults,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 46 (2011): 1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang L., Hu L., Xu Q., et al., “Bifidobacteria Exert Species‐Specific Effects on Constipation in BALB/c Mice,” Food & Function 8 (2017): 3587–3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoon J. Y., Cha J. M., Oh J. K., et al., “Probiotics Ameliorate Stool Consistency in Patients With Chronic Constipation: A Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Study,” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 63 (2018): 2754–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dimidi E., Zdanaviciene A., Christodoulides S., et al., “Randomised Clinical Trial: Bifidobacterium lactis NCC2818 Probiotic vs Placebo, and Impact on Gut Transit Time, Symptoms, and Gut Microbiology in Chronic Constipation,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 49 (2019): 251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shen Y., Jiang B., Zhang C., Wu Q., Li L., and Jiang P., “Combined Inhibition of the TGF‐β1/Smad Pathway by Prevotella copri and Lactobacillus murinus to Reduce Inflammation and Fibrosis in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24 (2023): 11010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan F., Zhang L., Li M., et al., “Predominant Gut Lactobacillus murinus Strain Mediates Anti‐Inflammaging Effects in Calorie‐Restricted Mice,” Microbiome 6 (2018): 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fan J., Zhang Y., Zuo M., et al., “Novel Mechanism by Which Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Lactobacillus murinus Alleviates Deoxynivalenol‐Induced Intestinal Barrier Disruption,” Environment International 185 (2024): 108525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tatsuoka M., Osaki Y., Ohsaka F., et al., “Consumption of Indigestible Saccharides and Administration of Bifidobacterium pseudolongum Reduce Mucosal Serotonin in Murine Colonic Mucosa,” British Journal of Nutrition 127 (2022): 513–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tatsuoka M., Shimada R., Ohsaka F., and Sonoyama K., “Administration of Bifidobacterium pseudolongum Suppresses the Increase of Colonic Serotonin and Alleviates Symptoms in Dextran Sodium Sulfate‐Induced Colitis in Mice,” Bioscience of Microbiota, Food and Health 42 (2023): 186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhan Y., Wen Y., Zhang L. L., et al., “Paeoniflorin Improved Constipation in the Loperamide‐Induced Rat Model via TGR5/TRPA1 Signaling‐Mediated 5‐Hydroxytryptamine Secretion,” Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021 (2021): 6076293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhi H. and Yuan W. T., “Expression of Aquaporin 3, 4, and 8 in Colonic Mucosa of Rat Models With Slow Transit Constipation,” Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 14 (2011): 459–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chao G. and Zhang S., “Aquaporins 1, 3 and 8 Expression in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Rats' Colon via NF‐κB Pathway,” Oncotarget 8 (2017): 47175–47183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ikarashi N., Kon R., and Sugiyama K., “Aquaporins in the Colon as a New Therapeutic Target in Diarrhea and Constipation,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17 (2016): 1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shi Y., Chen F., Wang Z., Cao J., and Li C., “Effect and Mechanism of Functional Compound Fruit Drink on Gut Microbiota in Constipation Mice,” Food Chemistry 401 (2023): 134210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim J. E., Yun W. B., Lee M. L., et al., “Synergic Laxative Effects of an Herbal Mixture of Liriope platyphylla, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, and Cinnamomum cassia in Loperamide‐Induced Constipation of Sprague Dawley Rats,” Journal of Medicinal Food 22 (2019): 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shin A., Camilleri M., Vijayvargiya P., et al., “Bowel Functions, Fecal Unconjugated Primary and Secondary Bile Acids, and Colonic Transit in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 11 (2013): 1270–1275.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Appleby R. N. and Walters J. R., “The Role of Bile Acids in Functional GI Disorders,” Neurogastroenterology and Motility 26 (2014): 1057–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ge Z., Duan Z., Yang H., et al., “Home‐Based Transcutaneous Neuromodulation Improved Constipation via Modulating Gastrointestinal Hormones and Bile Acids,” Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018 (2018): 2086163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saegusa Y., Takeda H., Muto S., et al., “Decreased Motility of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter in a Rat Model of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease May Be Mediated by Reductions of Serotonin and Acetylcholine Signaling,” Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 34 (2011): 704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang Y., Jiang H., Wang L., et al., “Luteolin Ameliorates Loperamide‐Induced Functional Constipation in Mice,” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 56 (2023): e12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang T., Lu H., Cheng T., et al., “ Bifidobacterium longum S3 Alleviates Loperamide‐Induced Constipation by Modulating Intestinal Acetic Acid and Stearic Acid Levels in Mice,” Food & Function 15 (2024): 6118–6133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nie W., Xu F., Zhou K., Yang X., Zhou H., and Xu B., “Stearic Acid Prevent Alcohol‐Induced Liver Damage by Regulating the Gut Microbiota,” Food Research International 155 (2022): 111095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen P., Torralba M., Tan J., et al., “Supplementation of Saturated Long‐Chain Fatty Acids Maintains Intestinal Eubiosis and Reduces Ethanol‐Induced Liver Injury in Mice,” Gastroenterology 148 (2015): 203–214.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spiller R. C., Brown M. L., and Phillips S. F., “Decreased Fluid Tolerance, Accelerated Transit, and Abnormal Motility of the Human Colon Induced by Oleic Acid,” Gastroenterology 91 (1986): 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ogawa N., Yamaguchi H., Shimbara T., et al., “The Vagal Afferent Pathway Does Not Play a Major Role in the Induction of Satiety by Intestinal Fatty Acid in Rats,” Neuroscience Letters 433 (2008): 38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsai C. C., Li Y. C., Chang L. C., Tey S. L., Lin K. J., and Huang S. C., “Long‐Chain Fatty Acid Receptors Mediate Relaxation of the Porcine Lower Esophageal Sphincter,” Frontiers in Physiology 10 (2019): 676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Identification of most characteristic taxa among three groups by linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe). (A) Analysis of taxonomic abundances on differentially enriched taxa in appendiceal content of each group using LEfSe. (B) Most significant differences among four experiment groups after LDA using a threshold score of > 3.5.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.